Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We develop a procedural approach to assign an Importance Factor (IF) to each system component based on its significance to the system’s overall operation.

- We enhance the security profile by incorporating IF values and extend the security awareness framework to generate enriched interpretations that provide insights into the affected components, their functionalities, and their operational significance.

2. Background

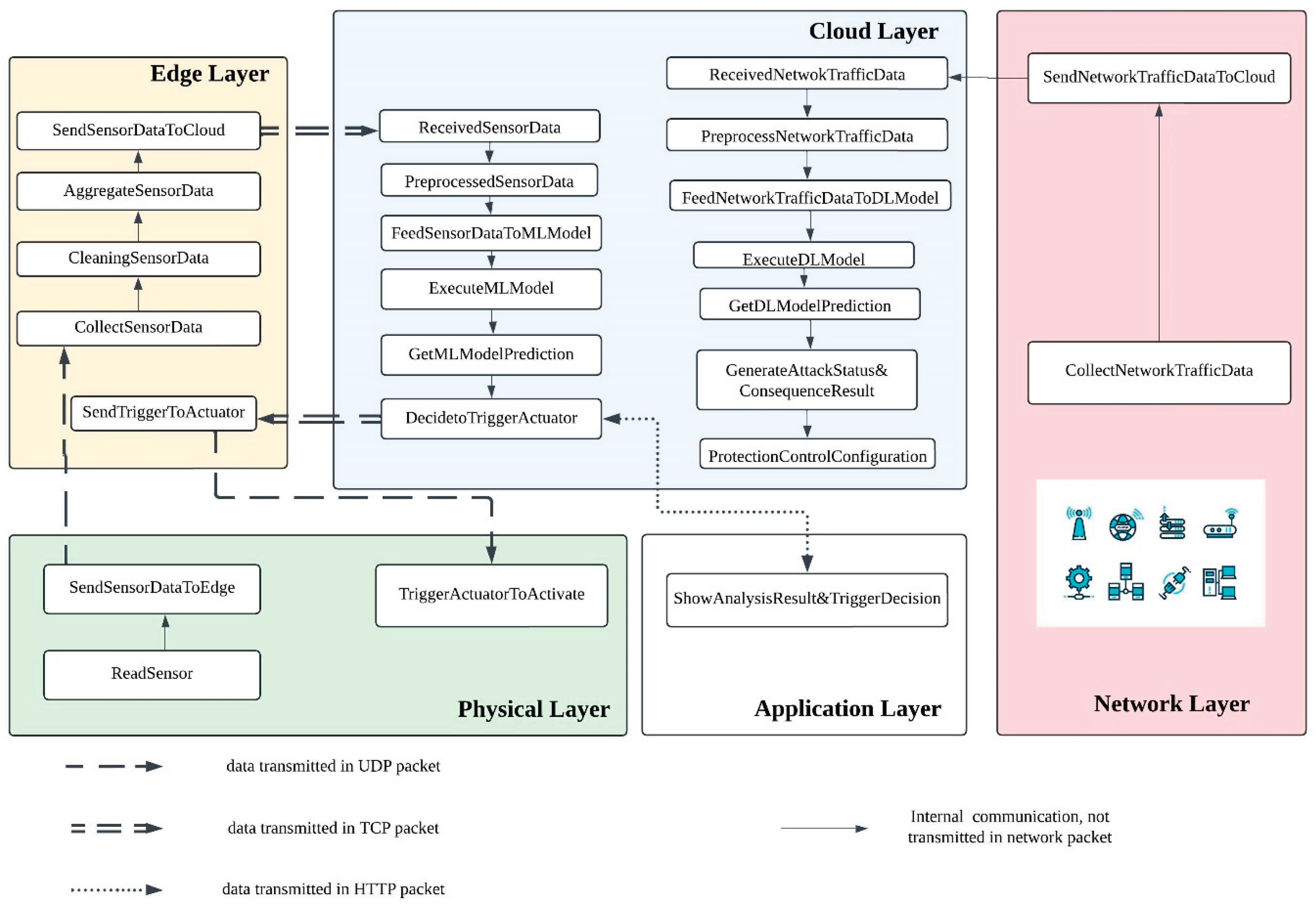

- Perception (or Physical) Layer: Houses sensing devices and collects raw data.

- Edge/Fog Layer: Offers localized computing resources to reduce latency and offload processing from the cloud.

- Cloud Layer: Manages large-scale data processing, analysis, and storage using heterogeneous cloud services [31].

- Network (or Transport) Layer: Ensures data transmission between layers.

- Application Layer: Delivers services and interfaces to end users.

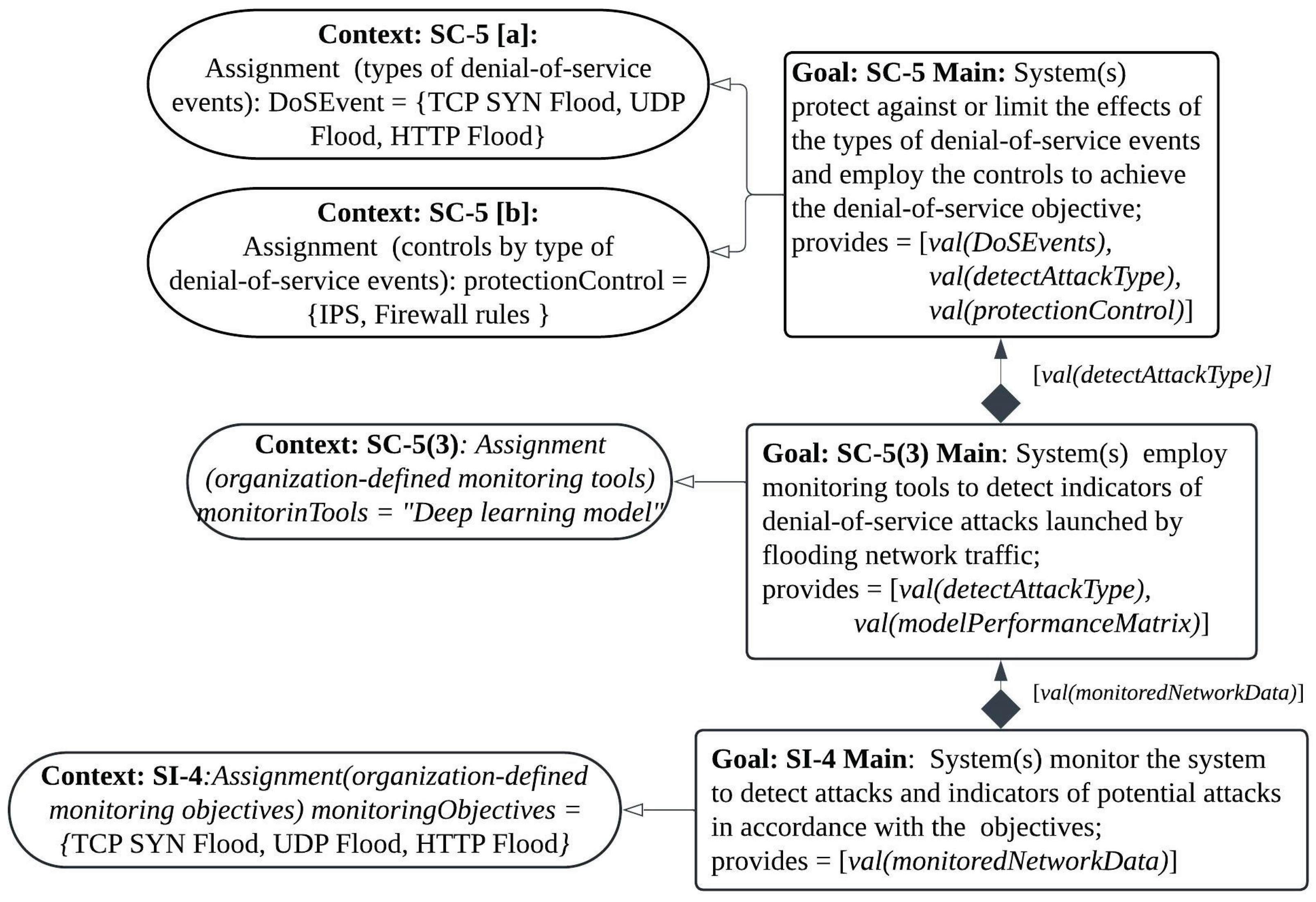

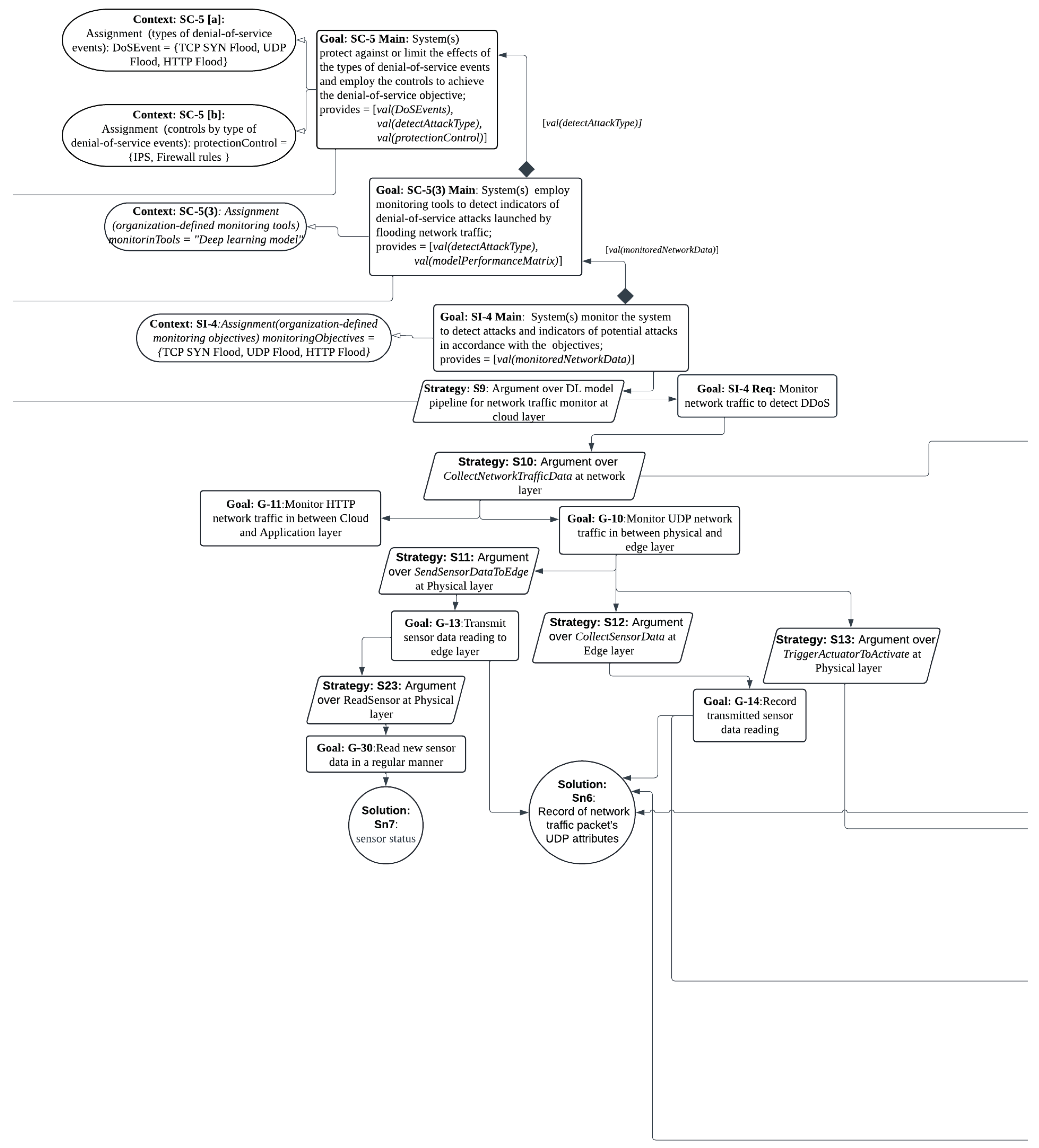

3. Approach

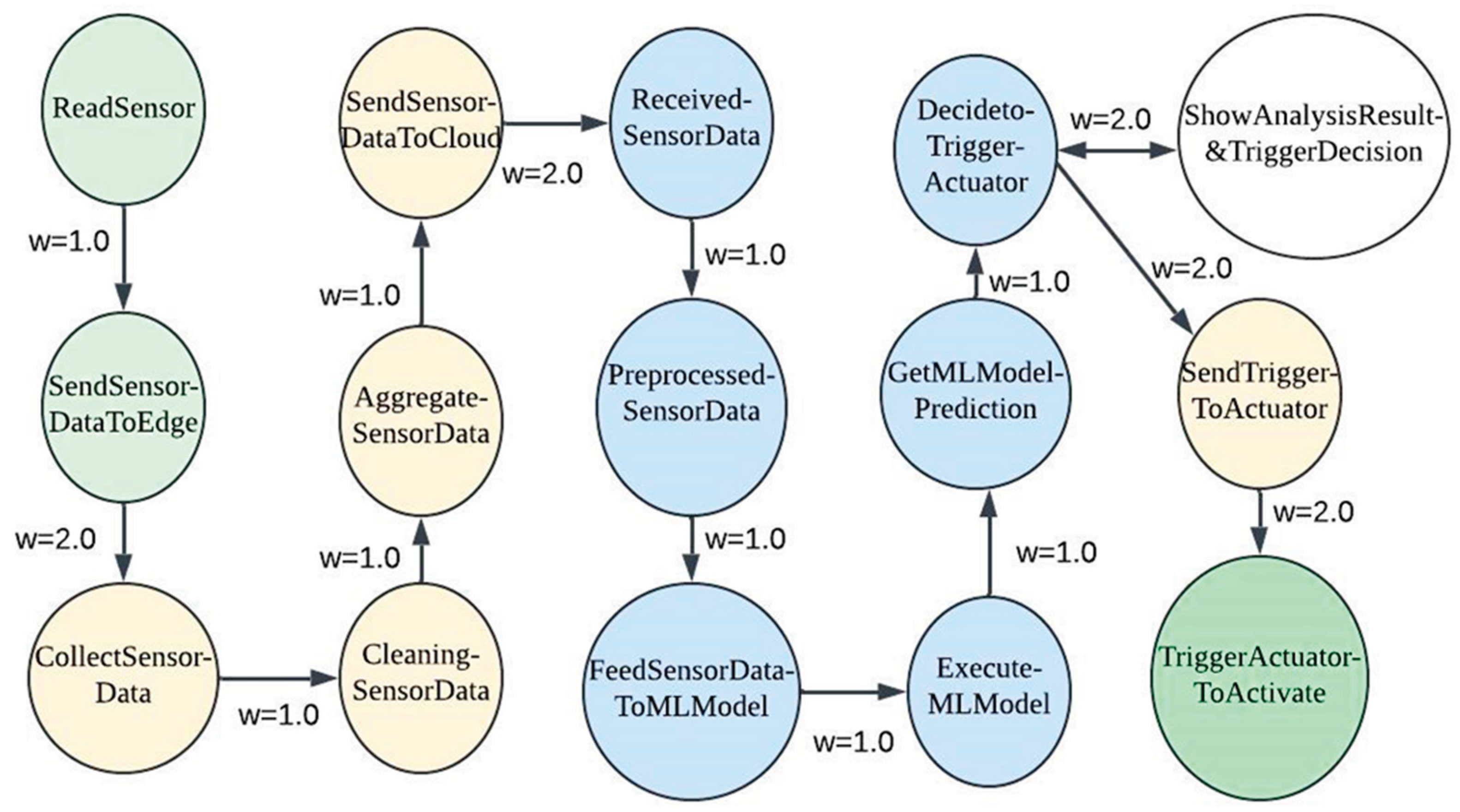

3.1. IoT Based Smart Irrigation System Testbed

- To ShowAnalysisResult&TriggerDecision at the Application Layer, where the user is notified of the prediction and actuator decision.

- To the Edge Layer, where the SendTriggerToActuator process relays the command to the Physical Layer. In this layer, the TriggerActuatorToActivate process initiates actuator activation, which is simulated in the testbed using a buzzer that represents the irrigation valve.

3.2. IoT DDoS Dataset and DNN Model

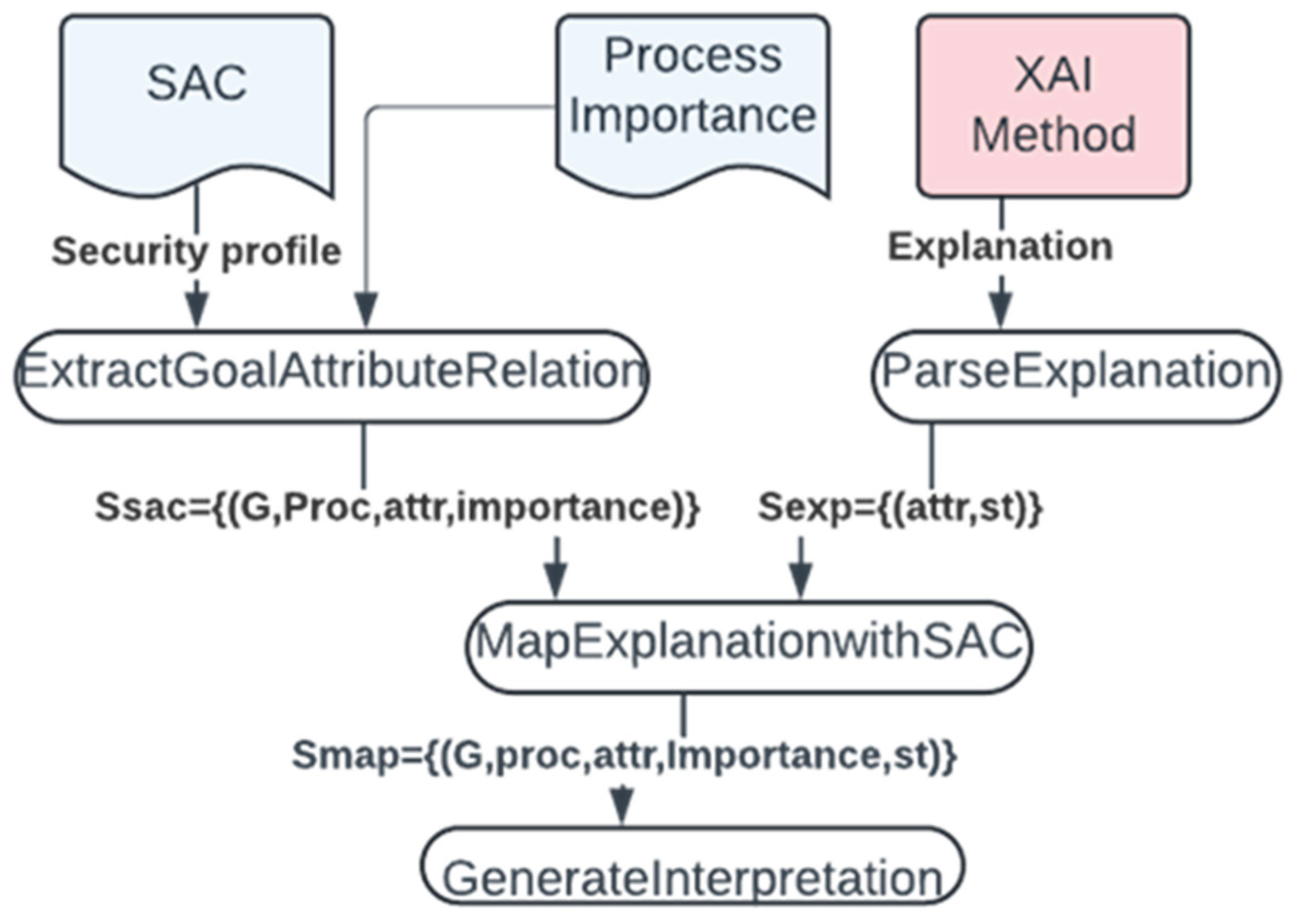

3.3. Local Explanation of the DNN Model and Information Extraction

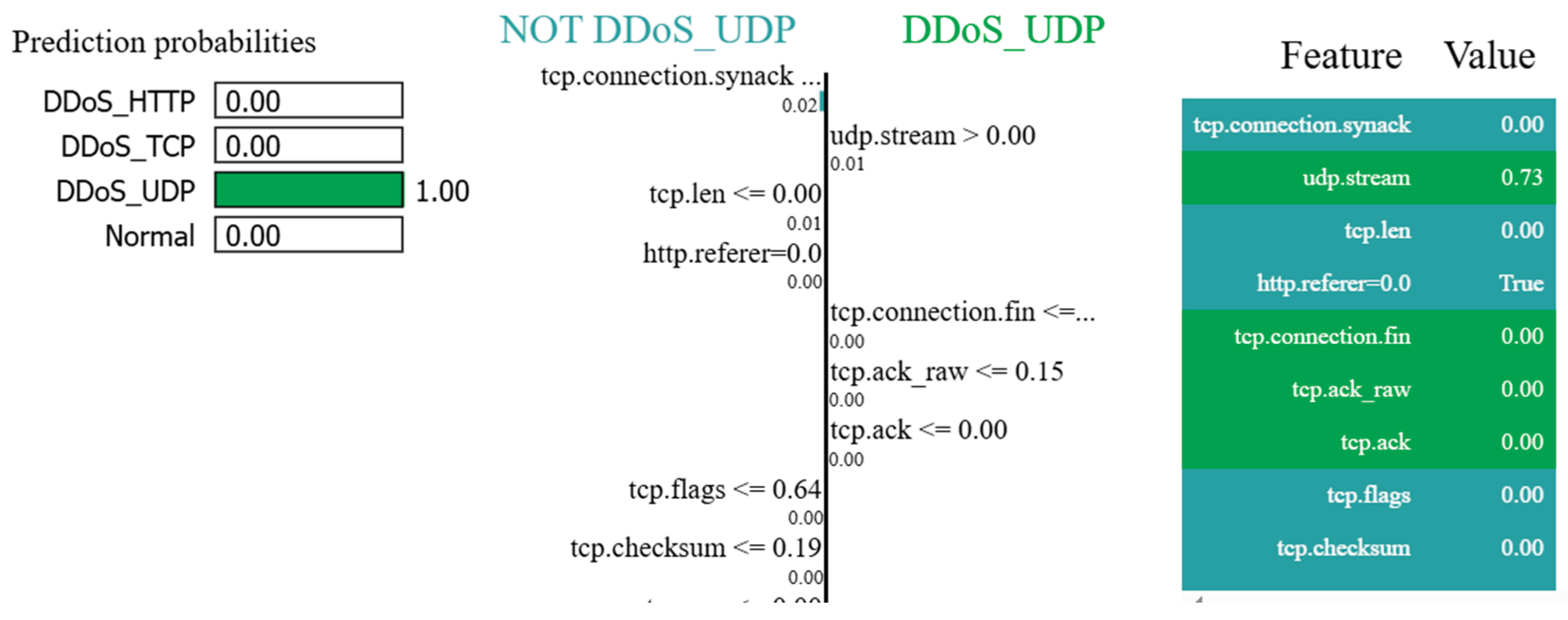

- Left Side (NOT DDoS_UDP): Displays attributes that contributed to the prediction that the instance is not a DDoS_UDP attack.

- Right Side (DDoS_UDP): Highlights attributes that pushed the prediction toward a DDoS_UDP classification.

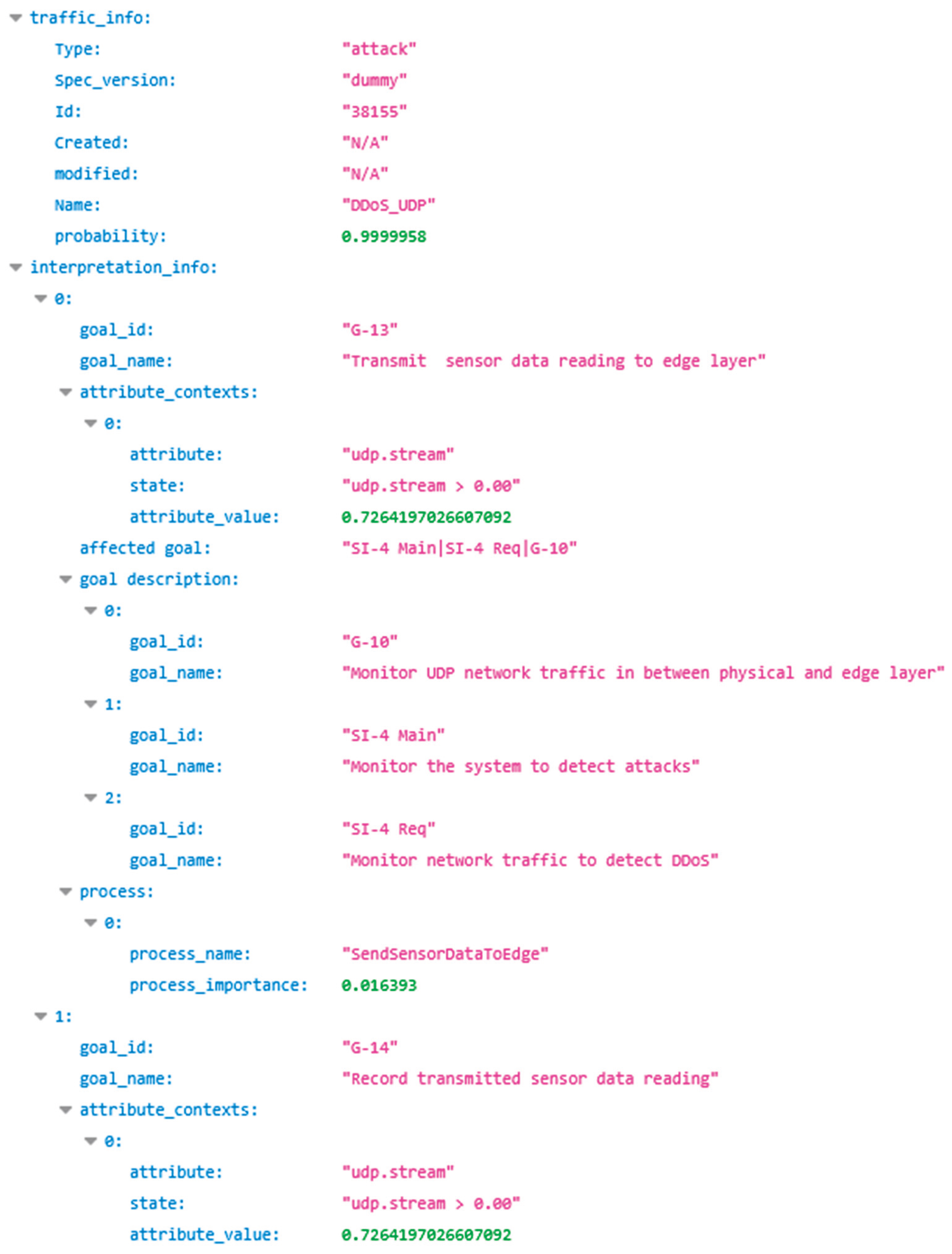

- interpretation_info: A nested object outlining affected attributes and their states, associated processes, corresponding goals, and IFs.

- traffic_info: A summary of the model's prediction (e.g., DDoS_UDP with 99% confidence) and the relevant attack context.

3.4. Generate System-Call Dependency Graph (ScD Graph) and Calculate Importance Factor (IF) Assigned to Each Process

4. Performance Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reggio, G.; Leotta, M.; Cerioli, M.; Spalazzese, R.; Alkhabbas, F. What are IoT systems for real? An experts’ survey on software engineering aspects. Internet of Things 2020, 12, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; & Palaniswami, M. Internet of Things (IoT): A vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future generation computer systems 29.7, 2013; pp. 1645-1660. [CrossRef]

- Taivalsaari, A.; Mikkonen, T. On the development of IoT systems. Third International Conference on Fog and Mobile Edge Computing (FMEC). IEEE, 2018; pp. 13-19. [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, L.A.; Muheidat, F.; Tawalbeh, M.; Quwaider, M. IoT Privacy and security: Challenges and solutions. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaba, F. A.; Othman, M.; Hashem, I. A. T.; Alotaibi, F. Internet of Things security: A survey. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2017, 88, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, S.; Alqahtani, S.; Gamble, R. F.; Bayesh, M. Automated Extraction of Security Profile Information from XAI Outcomes. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing and Self-Organizing Systems Companion (ACSOS-C), IEEE, 2023; pp. 110-115. [CrossRef]

- Petrovska, A. Self-Awareness as a Prerequisite for Self-Adaptivity in Computing Systems. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing and Self-Organizing Systems Companion (ACSOS-C), IEEE, 2021; pp. 146-149. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Lam, K. Y.; Tavva, Y. Autonomous vehicle: Security by design. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 22(11), 2020; pp. 7015-7029. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yi, X.; Wei, S. A study of network security situational awareness in Internet of Things. In 2020 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), IEEE, 2020; pp. 1624-1629. [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Wen, H.; Hou, W.; Xu, X. New security state awareness model for IoT devices with edge intelligence. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 69756–69765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, A.; Rahmani, A. M. The Internet of Autonomous Things applications: A taxonomy, technologies, and future directions. Internet of Things 2022, 20, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Nagothu, D.; Chen, Y.; Aved, A.; Ardiles-Cruz, E.; Blasch, E. A Secure Interconnected Autonomous System Architecture for Multi-Domain IoT Ecosystems. IEEE Communications Magazine 2024, 62, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehie, M.; Tahvildari, L. Self-adaptive software: Landscape and research challenges. ACM transactions on autonomous and adaptive systems (TAAS) 2009, 4, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezavehi, S. M.; Weyns, D.; Avgeriou, P.; Calinescu, R.; Mirandola, R.; Perez-Palacin, D. Uncertainty in self-adaptive systems: A research community perspective. ACM Transactions on Autonomous and Adaptive Systems (TAAS) 2021, 15, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, S.; Riley, I.; Gamble, R. F. Assessing adaptations based on change impacts. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing and Self-Organizing Systems (ACSOS), IEEE, 2020; pp. 48-54. [CrossRef]

- Jahan, S. An adaptation assessment framework for runtime security assurance case evolution. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Tulsa, 2021. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2637547876?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

- Gheibi, O.; Weyns, D.; Quin, F. Applying machine learning in self-adaptive systems: A systematic literature review. ACM Transactions on Autonomous and Adaptive Systems (TAAS) 2021, 15, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electronic markets 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilone, G.; Longo, L. Explainable artificial intelligence: a systematic review. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable machine learning. Lulu. Com, 2020. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=jBm3DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Interpretable+machine+learning&ots=EhvWYjHDSY&sig=fJlg8xyZsauRhLjOYF_xUqr8khQ#v=onepage&q=Interpretable%20machine%20learning&f=false.

- Alexander, R.; Hawkins, R.; Kelly, T. Security assurance cases: motivation and the state of the art. High Integrity Systems Engineering, Department of Computer Science, University of York, Deramore Lane York YO10 5GH. 2011. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=623bb1c1ded3860ed1307d45a2a01823b13abff6.

- Kelly, T.; & Weaver, R. The goal structuring notation–a safety argument notation. In Proceedings of the dependable systems and networks 2004 workshop on assurance cases (Vol. 6). Princeton, NJ: Citeseer, 2004. http://dslab.konkuk.ac.kr/class/2012/12SIonSE/Key%20Papers/The%20Goal%20Structuring%20Notation%20_%20A%20Safety%20Argument%20Notation.pdf.

- Averbukh, V. L.; Bakhterev, M. O.; Manakov, D. V. Evaluations of visualization metaphors and views in the context of execution traces and call graphs. Scientific Visualization, 9(5), 2017; pp. 1-18. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Vladimir-Averbukh/publication/322070685_Evaluations_of_Visualization_Metaphors_and_Views_in_the_Context_of_Execution_Traces_and_Call_Graphs/links/5a4287690f7e9ba868a47bd5/Evaluations-of-Visualization-Metaphors-and-Views-in-the-Context-of-Execution-Traces-and-Call-Graphs.pdf.

- Salis, V.; Sotiropoulos, T.; Louridas, P.; Spinellis, D.; Mitropoulos, D. Pycg: Practical call graph generation in python. In 2021 IEEE/ACM 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE). IEEE, IEEE, Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 1646-1657. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, T.; Yan, J. PageRank centrality and algorithms for weighted, directed networks. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2022, 586, 126438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S. Centrality in networks: finding the most important nodes. In Business and Consumer Analytics: New Ideas; Moscato, P., de Vries, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Social network: critical concepts in sociology. Londres: Routledge, 1(3), 2002; pp. 238-263. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=fy3m_EixWOsC&oi=fnd&pg=PA238&dq=Centrality+in+social+networks+conceptual+clarification&ots=unHaJzR81U&sig=hG9bkrrpA_B-kQ0r2iy7ISsLvts#v=onepage&q=Centrality%20in%20social%20networks%20conceptual%20clarification&f=false.

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. Computer networks and ISDN systems, 30(1-7), 1998; pp. 107-117. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I. H.; Khan, A. I.; Abushark, Y. B.; Alsolami, F. Internet of things (iot) security intelligence: a comprehensive overview, machine learning solutions and research directions. Mobile Networks and Applications, 28(1), 2023; pp.296-312. [CrossRef]

- Bouaouad, A. E.; Cherradi, A.; Assoul, S.; Souissi, N. The key layers of IoT architecture. In 2020 5th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Artificial Intelligence: Technologies and Applications (CloudTech), IEEE, 2020; pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, H.; Belguith, S.; Alhomoud, A.; Jemai, A. A survey of IoT security based on a layered architecture of sensing and data analysis. Sensors 2020, 20, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukur, Y. M.; Thakker, D.; Awan, I. U. Multi-layer approach to internet of things (IoT) security. In 2019 7th International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud (FiCloud), IEEE, 2019; pp. 109-116. [CrossRef]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Saxena, V.; Jain, D.; Goyal, P.; Sikdar, B. A survey on IoT security: application areas, security threats, and solution architectures. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 82721–82743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargaoui, S.; et al. An overview of the security challenges in IoT environment. Advanced technology for smart environment and energy 2023, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohang, A.; Sargent, C. S.; Nord, J. H.; Paliszkiewicz, J. Internet of Things (IoT): From awareness to continued use. International Journal of Information Management 2022, 62, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, U.; Aseeri, A. O.; Alkatheiri, M. S.; Zhuang, Y. Context-aware autonomous security assertion for industrial IoT. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 191785–191794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darias, J. M.; Díaz-Agudo, B.; Recio-Garcia, J. A. A Systematic Review on Model-agnostic XAI Libraries. In ICCBR workshops, 2021; pp. 28-39.

- Lipton, Z.C. The mythos of model interpretability: In machine learning, the concept of interpretability is both important and slippery. Queue 2018, 16, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why should I trust you? Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.H., Abuwala, H.S., & Lim, C.H. Towards more stable LIME for explainable AI. In 2022 International Symposium on Intelligent Signal Processing and Communication Systems (ISPACS), IEEE, 2022; pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Dieber, J., & Kirrane, S. Why model why? Assessing the strengths and limitations of LIME. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.00093, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H. Shapley value: from cooperative game to explainable artificial intelligence. Autonomous Intelligent Systems 2024, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. Explainable ai is dead, long live explainable ai! hypothesis-driven decision support using evaluative ai. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency; 2023; pp. 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputri, T. R. D.; Lee, S. W. The application of machine learning in self-adaptive systems: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 205948–205967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A. Edge-IIoTset cyber security dataset of IoT & IIoT. 2023. Available at available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mohamedamineferrag/edgeiiotset-cyber-security-dataset-of-iot-iiot, Accessed May, 2025.

- Ferrag, M. A., Friha, O., Hamouda, D., Maglaras, L., & Janicke, H. Edge-IIoTset: A new comprehensive realistic cyber security dataset of IoT and IIoT applications for centralized and federated learning. IEEe Access, 10, 2022; pp.40281-40306. [CrossRef]

- Saheed, Y.K.; Abdulganiyu, O.H.; Majikumna, K.U.; Mustapha, M.; Workneh, A.D. ResNet50-1D-CNN: A new lightweight resNet50-One-dimensional convolution neural network transfer learning-based approach for improved intrusion detection in cyber-physical systems. International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection 2024, 45, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Task Force, “Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems,” NIST Special Publication 800-53, Revision 5, 2020.

- Reif, J.H. Depth-first search is inherently sequential. Information Processing Letters 1985, 20, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TCP attributes | Description |

| tcp.flags | Flags |

| tcp.ack | Acknowledgment number |

| tcp.ack_raw | Acknowledgment number (raw) |

| tcp.checksum | checksum |

| tcp.seq | Sequence number |

| tcp.flags.ack | Acknowledgment |

| tcp.len | TCP segment length |

| tcp.connection.syn | Connection establish request (SYN) |

| tcp.connection.rst | Connection reset (RST) |

| tcp.connection.fin | Connection finish (FIN) |

| tcp.connection.synack | Connection establish request (SYN+ACK) |

| Attack type | Description |

| TCP SYN Flood DDoS attack | Make the victim’s server unavailable to legitimate requests |

| UDP flood DDoS attack | Overwhelm the processing and response capabilities of victim devices |

| HTTP flood DDoS attack | Exploits seemingly legitimate HTTP GET or POST requests toattack IoT application |

| Process Name | Importance Factor |

| DecidetoTriggerActuator | 0.156 |

| TriggerActuatorToActivate | 0.094 |

| GetMLModelPrediction | 0.09 |

| ShowAnalysisResult&TriggerDecision | 0.086 |

| SendTriggerToActuator | 0.086 |

| ExecuteMLModel | 0.082 |

| FeedSensorDataToMLModel | 0.074 |

| PreprocessedSensorData | 0.066 |

| ReceivedSensorData | 0.057 |

| SendSensorDataToCloud | 0.049 |

| AggregateSensorData | 0.041 |

| CleaningSensorData | 0.033 |

| CollectSensorData | 0.025 |

| SendSensorDataToEdge | 0.016 |

| ReadSensor | 0.008 |

| Process Name | Average Execution time (in sec) | |

| Overall | Model Prediction | 0.154893 |

| Generate Explanation | 8.426568 | |

| Mapping and Generate Report | 0.151432 | |

| DDoS_UDP | Model Prediction | 0.159036 |

| Generate Explanation | 8.082033 | |

| Mapping and Generate Report | 0.153765 | |

| DDoS_TCP | Model Prediction | 0.152603 |

| Generate Explanation | 8.802392 | |

| Mapping and Generate Report | 0.149118 | |

| DDoS_HTTP | Model Prediction | 0.153175 |

| Generate Explanation | 8.373173 | |

| Mapping and Generate Report | 0.151548 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).