1. Introduction

One of the most distinctive symptoms of SARS-CoV2 infection is the loss in olfactory capacity or anosmia, affecting 85 to 98% of infected individuals [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This sign is also a common finding during post-COVID Syndrome (PCS) [

6].

Post-COVID syndrome (PCS) has emerged as a prevalent condition, defined by the persistence in symptoms after the acute confirmed infection with SARS-CoV-2 for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing/remitting, or progressive disease state [

7]; it is considered a systemic condition [

8], with an incidence and prevalence of 50% and 45% respectively [

8,

9]. Common signs and symptoms include fatigue, loss of memory, cognitive impairment, difficulty breathing, thoracic pain, anosmia, ageusia, arthralgias, myalgias and functional impairment [

10].

In older adults (OA), the prevalence of olfactory disturbances during PCS has been estimated in 9.3% [

11], OA are a vulnerable population for the development of complications associated to PCS, due to defects in immune response, typically associated to a high prevalence in cardiorenal metabolic, and geriatric comorbidities [

2,

7,

12,

13], as a result, OA have increased risk for cognitive decline [

14] and malnutrition [

15,

16] .

The development of cognitive impairment is of special interest in OA, since it has been a common neuropsychiatric consequence of COVID infection [

17,

18], believed to appear as result of increased permeability in the encephalic barrier and irreversible neuronal damage [

19], with deterioration in memory function, microvascular endothelial dysfunction, the presence of inflammatory metabolites and beta-amyloid within the brain [

20]. During PCS the development of cognitive impairment is not entirely clear, and the presence of additional risk factors such as nutrition imbalances in OA [

21] needs to be addressed. In general, the study of the PCS in OA has been scarcely explored in the literature [

22]. To fill this gap in knowledge, we underwent a cross-sectional study with the purpose of investigating the contribution of PCS and associated symptoms, especially anosmia and their nutritional status, to the presence of cognitive impairment in a cohort of OA hospitalized patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

Participants the met the following inclusion criteria were included in the study: (1) older adults (OA) hospitalized in the geriatric clinic of Hospital Civil Fray Antonio Alcalde, during the period comprised between August 2023 - August 2024 (2) a confirmed positive test and diagnosis of COVID-19 at least 3 months before the inclusion in our study, and (3) a diagnosis of post-COVID syndrome.

OA were excluded if they had a psychiatric condition such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, a neurological diagnosis of dementia or an important cognitive impairment to answer questionnaires or impeded to stablish study measurements.

The study protocol was designed according to the STROBE [

23] and RECORD guidelines for observational studies [

16] and submitted for IRB approval before patient recruitment. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki [

24].

Participants willingly accepted to participate in our study, after signature of the informed consent.

2.2. Study Design

This was a cross-sectional study, performed in the geriatric clinic of “Hospital Civil Fray Antonio Alcalde”, at Guadalajara, Jal. México. For all participants, data were collected immediately after hospital admission.

2.3. Study Measurements

2.3.1. Demographic and Clinical Variables

Demographic and clinical information related to COVID-19 infection and post-Covid syndrome was obtained by an interview guided with a pre-design questionnaire that included the clinical history. Additionally, the information was confirmed by reviewing electronic institutional charts.

2.3.2. Olfactory Functions

To measure olfactory function in our patients, we used the Sniffin’ Stick Test II, which has been previously validated for this purpose [

13]. The capacity for odor identification was evaluated using 12 common odors; the identification of <9 odors was defined as functional hyposmia and <6 as anosmia. In each participant, olfactory tests, nutritional status, and cognitive abilities were performed during the same session in a well-ventilated room. First, we evaluated olfactory function, then cognitive abilities, and finally nutritional status.

2.3.3. Evaluation of Cognitive Function

Cognitive function was assessed by applying standardized Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [

4]. Domains evaluated by this test include orientation, memory, attention and executive function. Scores ranged from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating increasing severity of cognitive impairment. Subjects with cognitive impairment had scores between 0 and 18 and individuals who scored 19-24 were considered at risk for cognitive impairment.

2.3.4. Nutritional Assessment

Measurements were obtained by a certified geriatric nutritionist, and included, the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA

®), which has been validated for OA [

12]. The MNA includes anthropometric measurements, a global assessment, a dietary questionnaire and a subjective assessment. According to the developers’ instructions, the MNA administration utilizes a two-step approach: screening and a global assessment. Subsequently, based on the MNA total score, patients are classified as ‘‘malnourished’’ (score <17), ‘‘at risk of malnutrition’’ (scores 17.5 - 23.5) or as having a ‘‘normal nutritional status” (score >24). The ‘‘global assessment step’’ of the MNA should only be administered to patients not reaching the screening threshold. Additionally, other measurements were added to the nutritional status including height, weight, mid-arm circumference (MAC) and calf circumference (CC). Weight was measured in kilograms, with participants standing up, using a Tanita BC-558 Ironman scale. Height was measured in centimeters with participants placed under the stadiometer, head facing forward, without shoes, and feet together, using a Seca 213 portable stadiometer. Calf circumference CC was measured in centimeters with Lufkin anthropometric tape, at the point where the calf acquires greater volume between the ankle and knee. The mid-arm circumference (MAC) was measured in centimeters with Lufkin’s anthropometric tape, performed on the arm bent in a 90º position and with a tape measure at the midpoint between the bony points of the acromion and olecranon.

2.3.5. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages; continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Inferences for categorical variables were established with the chi squared test. For continuous dependent variables we used single and multiple linear regression models, to establish the association of risk factors for cognitive impairment in post-COVID Syndrome. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant, we used the software STATA 17 for calculations.

3. Results

A total of 90 patients were hospitalized in our clinic, main reasons being: upper respiratory tract affection (38%), cerebrovascular or neurological affections (29%), general malaise/fever of unknown origin (15%), GI tract affection/dehydration (13%), and anemia or cardiometabolic alterations (4%).

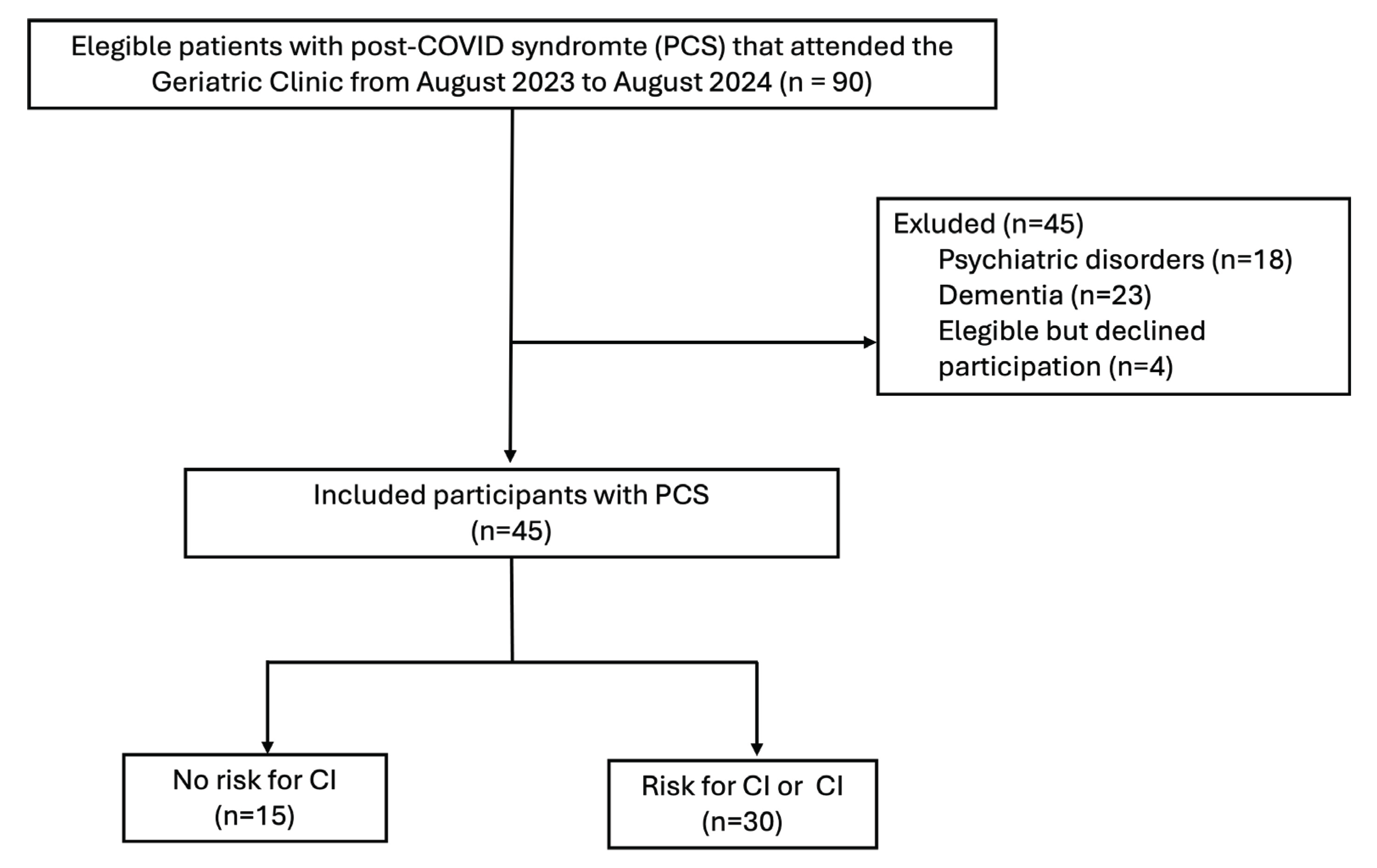

For all hospitalized patients, eligibility was assessed, subjects that met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study (

Figure 1). his section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

The sociodemographic characteristics of OA are described in

Table 1, divided by the presence of risk for cognitive impairment or cognitive impairment (MMSE < 24); overall, the studied population had a mean age of 75.9 ± 6.4 years old, and 51.1% were female. The more frequent comorbidities included hypertension in 55.6%, Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) in 40%, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 35.6% and chronic kidney disease (CKD) in 22.2%; more than 50% of the studied population had more than 3 comorbidities at the time of the assessment.

With respect to COVID infection, up to 53.3% required hospitalization during the acute phase of the disease, with a median (ICR) of 5 (0-15) hospital days. Therapy with supplementary oxygen was required by 75.5% and 4% assisted mechanical ventilation.

In the post-COVID stage, 77.8% were unable to wean off supplemental oxygen, 86% presented anosmia, 91.1% fatigue, 55.5% ageusia, 73.3% memory problems, and 77.7% insomnia. The average duration of these symptoms was 99.48 ± 128.15 days.

With respect to nutritional risk, a total of 23 patients (51 %) were in the normal/risk group, and 22 (49 %) had malnutrition. Compared to those with a normal/risk nutritional status, those with malnutrition had significantly lower weight (57.0 vs. 73.2 kg), a lower BMI (21.3 vs. 28.1), smaller calf circumference (26.9 vs. 34.0), mid-arm circumference (23.4 vs. 28.8), and a lower MNA score (14.5 vs. 22.4) (p for all < 0.05). The malnutrition group also had a higher frequency of diabetes (22.7% vs. 56.5%).

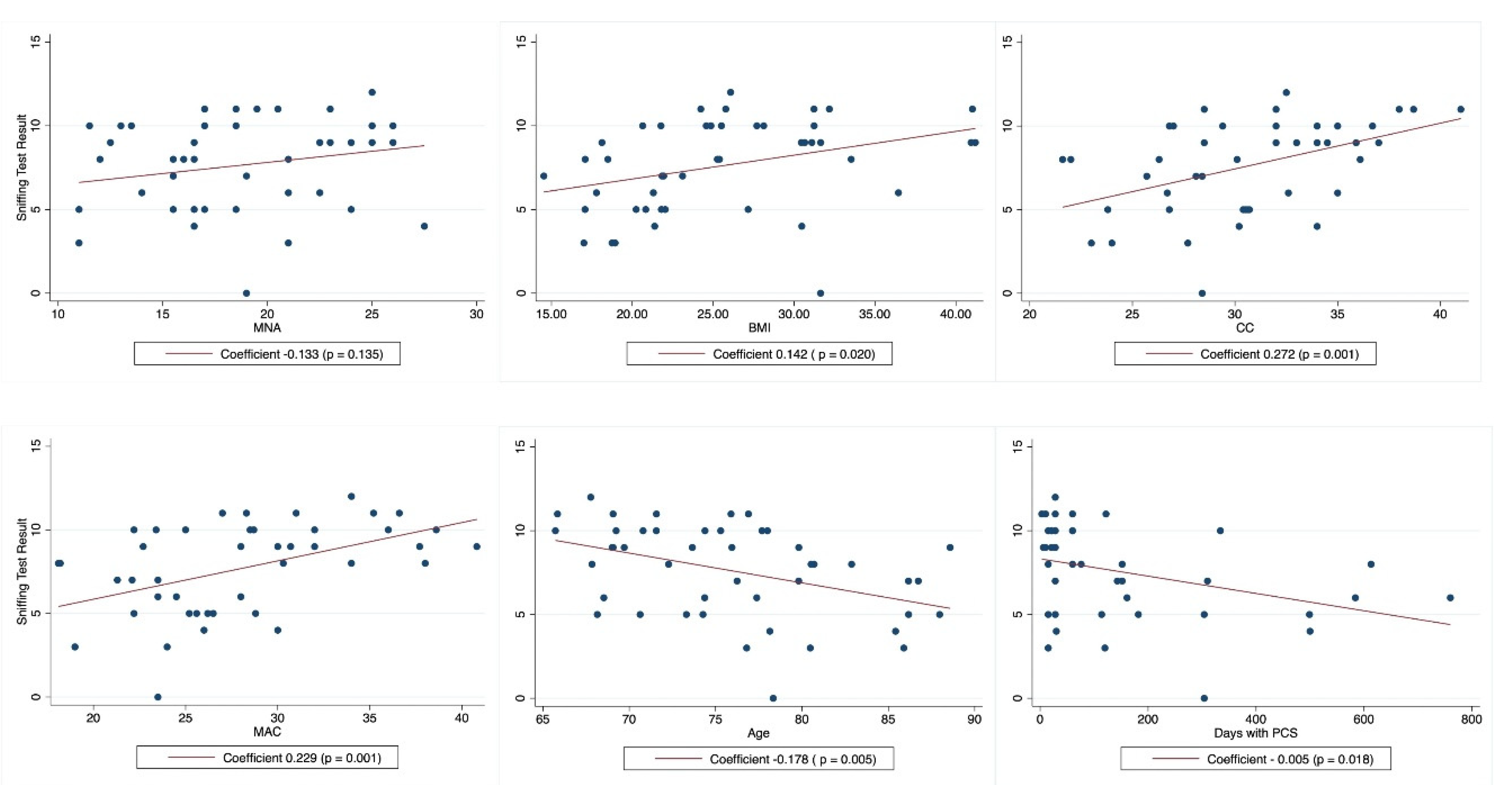

We then evaluated coefficients of variation for cognitive decline, measured by the MMSE, per individual variables and 95% CI (

Table 2), where a significant association was identified with the sniffing test. Other variables previously described to contribute to cognitive impairment were non-significant. To further explore this significant association with cognitive decline we tested a multivariable model to adjust the previous observed significant association, variables included in the model were selected after single regression coefficients were analyzed and on their biological role for cognitive impairment; after the analysis of this model (p=0.0451), loss of functional olfactory capacity with the sniffing test remains as the single variable with significant contribution to a DC.

With respect to olfactory capacity, 53.3% of the population included in our study had hyposmia and 33.3% had anosmia. We found that the olfactory capacity, assessed by the sniffing test, had a positive correlation with MMSE (p = 0.012) (

Figure 2), and a negative correlation with increased age (p = 0.005) and the number of days with PCS (p = 0.018).

Interestingly, the sniffing test was not significantly associated with MNA, but it showed a significant association with CC, MAC, BMI, and obesity (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

In this cohort of OA with Post-COVID syndrome, decline in olfactory capacity was common, this complication was associated to cognitive impairment and nutritional status. Both associations maintain a gradient of severity, as the olfactory capacity worsens, the cognitive state declines assessed by the MMSE. Of notice a decline in the sniffing test was associated with several measurements of the nutritional state such as BMI, CC and MAC but not with the MNA test. Which might reflect some important considerations for the routine use of MNA in the hospital setting, where other measurements or tools could be more useful, such as the BMI, CC, and MAC for isolated measurements and the NRS-2002, MUST and SGA as tools to evaluate nutritional status in hospitalized OA [

25]. MNA test has been very useful in identifying the risk for malnourishment but does not consider other abnormalities such as obesity or overweight which have been important factors associated to COVID infection [

26].

Cognitive impairment was identified in more than two-thirds of older adults in our study. In previous studies, persistent inflammation during post-COVID syndrome has been associated with fatigue, cognitive decline, and behavioral disorders [

11,

27,

28].

We observed a significant association between reduced olfactory function and cognitive decline. This event may be bidirectional and can be explained by the pathophysiological mechanism of immune hyperactivation, neuroinflammation, direct viral encephalitis, blood-brain barrier integrity damage, hypoxia, and cerebrovascular disease [

15], leading to multiorgan impairment, as expressed in the scores evaluating both tests. In a meta-analysis performed by Ceban et al., brain neurodegeneration was observed in COVID-19 patients, with microvascular damage and metabolic alterations such as hypometabolism in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [

11].

In our study, another important factor for cognitive decline was increased age; aging plays a fundamental role in olfactory capacity, reaching its peak at age 40 and progressively declining. The risk of olfactory dysfunction increases with age [

22]. Other previous studies have shown similar results to our univariate linear regression analysis, showing that, as age increases, olfactory capacity decreases [

3].

In the Muccioli et al. study, brain magnetic resonance imaging examined the integrity of the olfactory system and the neuropsychological profile in patients with persistent olfactory dysfunction related to COVID-19 infection and healthy controls. There was a correlation between alterations in the olfactory network and the severity of olfactory dysfunction and neuropsychological tests, without morphological changes. However, no evidence in this study suggested neurodegeneration in patients with PCS [

29].

Another study evaluated the sense of smell in 4,214 older adults along with tests of plasma amyloid-beta Aβ42, plasma amyloid-beta Aβ40, total tau protein, and neurofilament light chain (NfL). An association was found between olfactory impairment and increased risk of cognitive decline. Anosmia was significantly associated with higher total plasma NfL and tau concentrations, smaller hippocampal cortex volumes, and reduced cortical thickness [

14]. Our study did not measure these plasma concentrations.

The sense of smell is essential for physiology and homeostasis, that has evolved over time; it stimulates appetite, promotes food intake, protects from poisoning, and is associated with better quality of life [

15,

30]. SARS-CoV-2 infection specifically reduces olfactory capacity through multiple pathways, including endothelial dysfunction, autoimmunity, latent viral reactivation, hyperinflammation, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction [

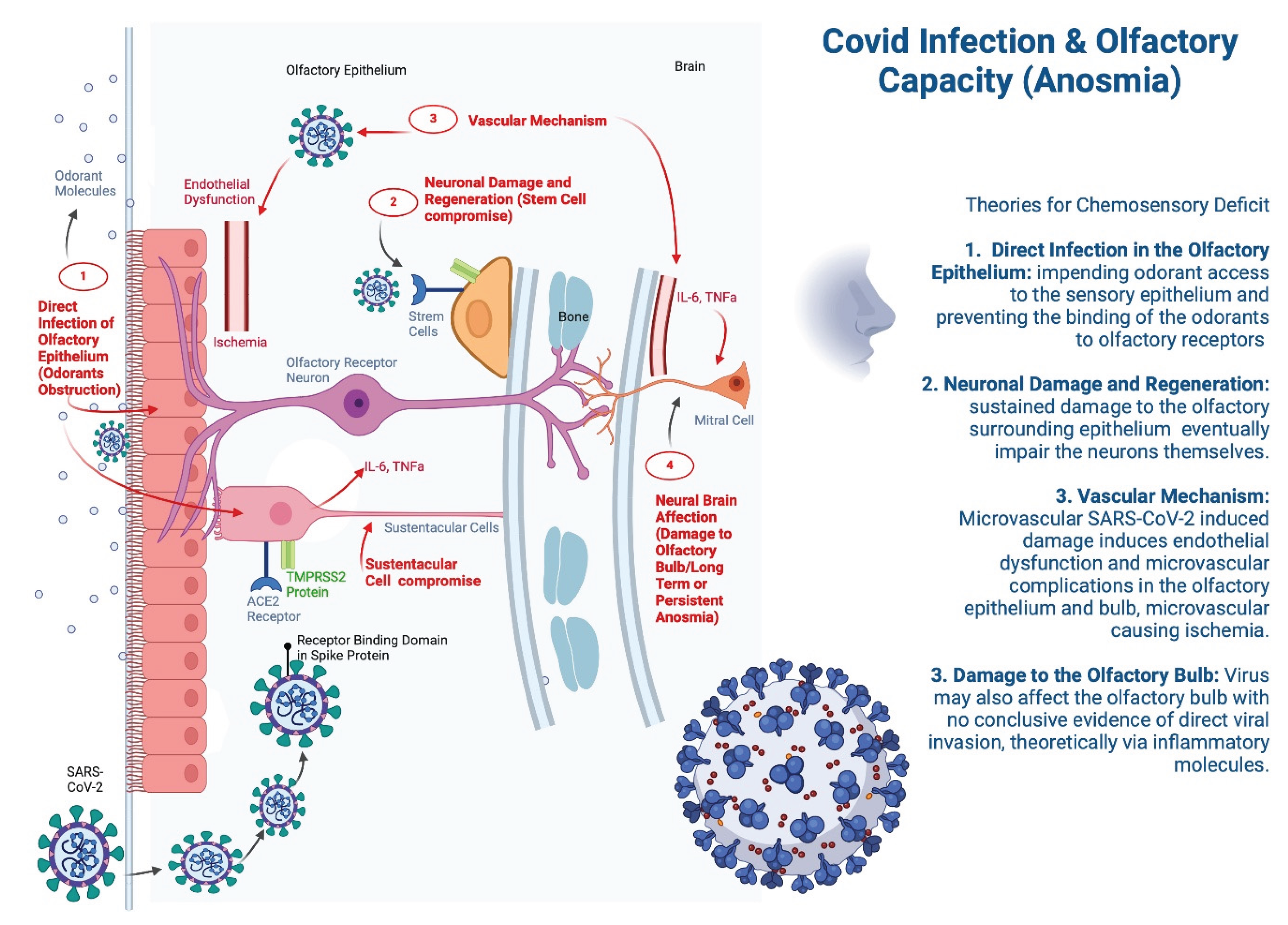

31] (

Figure 3). As olfactory capacity decreases, the risk of malnutrition increases [

32].

In our study, more than two-thirds of patients had hyposmia or anosmia, a similar finding was previously reported to by Lechien et al. in a sample of 417 patients where 85.6% presented olfactory alterations [

33].

Anosmia is considered a common and cardinal symptom of COVID-19, particularly in the early stages of infection, sometimes being the only symptom in an otherwise asymptomatic patient. SARS-CoV-2 primarily targets cells expressing the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is abundantly present in the nasal epithelium, particularly on non-neuronal cells. Key cells involved in the loss of olfactory function are the sustentacular cells that support the function of olfactory neurons [

34].

Currently the development of anosmia in COVID-19 is considered to have a heritable component of up to 48% [

35].

Furthermore, the direct infection of the olfactory epithelium or physical obstruction theory, proposes impending odorant access to the sensory epithelium, preventing the binding of odorants to olfactory receptors [

36], in this theory, SARS-CoV-2 infects the sustentacular cells in the olfactory epithelium, leading to local inflammation, edema, and cellular damage, impairing the function of olfactory sensory neurons, which indirectly results in anosmia. The virus may also affect the olfactory bulb, contributing to prolonged anosmia even after the acute infection resolves, which is often seen in post-COVID Syndrome [

37]. Another proposed mechanism for the generation of anosmia, involves microvascular damage as SARS-CoV-2 is known to induce endothelial dysfunction [

34]. In cases of prolonged or persistent anosmia, the mechanisms may involve more severe damage to the olfactory epithelium, prolonged inflammation, or delayed neuronal regeneration [

34].

Malnutrition in OA with post-COVID syndrome is one of the most common complications. Loss of smell may contribute to the deterioration of nutritional status [

38]. Previous studies discuss olfactory capacity and its impact on nutritional status [

39,

40]; however, only one recent study showed a correlation between olfactory function and the subjective global assessment (SGA) score in patients with chronic kidney disease. However, SGA is a tool that indirectly assesses malnutrition [

41]. Nevertheless, there are multiple investigations without an association between olfactory capacity and nutritional status [

3,

42,

43,

44].

A similar study to ours evaluated the relationship between olfactory dysfunction, nutritional status, and cognitive function. It assessed 45 geriatric patients with neurodegenerative diseases and found that olfactory function had no association with nutritional status [

45]. This cohort differs from ours as it was conducted in 2016, before the emergence of COVID-19, making it impossible to compare with our post-COVID patients, who present a distinct pathophysiological mechanism of olfactory decline, as well as different management and prognosis.

The results presented in this study have limitations. The nature of this cohort does not imply causality but rather generates hypotheses. The sample size is small, and there are multiple confounders that are impossible to rule out with our data. We did not measure inflammatory biomarkers, which have been associated with our objectives. The type of study in this research was cross-sectional. However, there are multiple reports of post-COVID patients studied for 12 weeks or more [

11]. We did not determine the treatments the patients received for managing post-COVID syndrome.

The strengths of our study lie in its population; older adults with post-COVID syndrome have been a little-studied group despite suffering severe sequels from the complications. We evaluated, together, the risk of malnutrition, olfactory capacity, and cognitive impairment, metrics that require time and training by qualified personnel.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we observed that OA with post-COVID syndrome frequently presented a decline in olfactory capacity with 9 out of 10 patients being affected, this complication was associated to cognitive impairment and nutritional status. Our findings should be confirmed in larger, longer-term, multicenter studies with measurements of inflammatory biomarkers and other comorbidities previously associated to cognitive impairment. Furthermore, the research around post-COVID syndrome should be enhanced to define better treatments that can help this population to resolve their situation and prevent its participation in the development of more serious or threatening outcomes for OA.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ALGG, LGL and MGZC; methodology, ALGG, LGL and MGZC; formal analysis, MGZC.; investigation, ALGG, JCI, and MVV; resources, ALG, LGL and MGZC; data obtention, ALGG; data curation, ALGG and MGZC; writing—original draft preparation, ALGG, JCI, MVV, and MGZC; writing—review and editing ALGG, LGL, JCI, MVV, and MGZC; supervision, LGL, JCI, and MGZC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding. Upon acceptance APC will be covered by institutional “Fondo Semilla” from Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board “Comité de ética, conducta y prevención de conflictos de interés del Hospital Civil de Guadalajara” (number 184/23 with date: Aug/09/2023.).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We used BioRender for the creation of Figure 3. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CC |

Calf circumference |

| MAC |

Middle arm circumference |

| MMSE |

Mini mental state examination |

| MNA |

Mini nutritional assessment |

| PCS |

Post-COVD syndrome |

References

- OMS. Información basica sobre la COVID-19 Organización Mundial de la Salud 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.

- Ángeles Correa MG, Villarreal Ríos E, Galicia Rodríguez L, et al. Enfermedades crónicas degenerativas como factor de riesgo de letalidad por COVID-19 en México. Revista panamericana de salud publica, Pan American journal of public health. 2022;46.

- Arikawa E, Kaneko N, Nohara K, et al. Influence of Olfactory Function on Appetite and Nutritional Status in the Elderly Requiring Nursing Care. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(4):398-403.

- Reyes de Beaman S, Beaman PE, García-Peña C, et al. “Validation of a modified version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in spanish”. Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition 2004;11:1-11.

- Borsetto D, Hopkins C, Philips V, et al. Self-reported alteration of sense of smell or taste in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis on 3563 patients. Rhinology. 2020;58(5):430-436.

- Wanga V, Chevinsky JR, Dimitrov LV, et al. Long-Term Symptoms Among Adults Tested for SARS-CoV-2 - United States, January 2020-April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(36):1235-1241.

- Prevention CfDCa. Long COVID Basics Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.; 2024 [updated 204; cited 2024 July 26]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/long-term-effects/.

- Carrillo-Esper R. Post-COVID-19 syndrome. Gac Med Mex. 2022;158(3):115-117.

- Carfi A, Bernabei R, Landi F, et al. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605.

- Cabrera Martimbianco AL, Pacheco RL, Bagattini ÂM, et al. Frequency, signs and symptoms, and criteria adopted for long COVID-19: A systematic review. International journal of clinical practice. 2021;75(10).

- Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93-135.

- Cereda E, Pedrolli C, Klersy C, et al. Nutritional status in older persons according to healthcare setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence data using MNA((R)). Clin Nutr. 2016;35(6):1282-1290.

- Cho JH, Jeong YS, Lee YJ, et al. The Korean version of the Sniffin’ stick (KVSS) test and its validity in comparison with the cross-cultural smell identification test (CC-SIT). Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36(3):280-6.

- Dong Y, Li Y, Liu K, et al. Anosmia, mild cognitive impairment, and biomarkers of brain aging in older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(2):589-601.

- Doty RL. Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: pathology and long-term implications for brain health. Trends Mol Med. 2022;28(9):781-794.

- Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885.

- He D, Yuan M, Dang W, et al. Long term neuropsychiatric consequences in COVID-19 survivors: Cognitive impairment and inflammatory underpinnings fifteen months after discharge. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;80:103409.

- Mansell V, Hall Dykgraaf S, Kidd M, et al. Long COVID and older people. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022;3(12):e849-e854.

- Chen Y, Yang W, Chen F, et al. COVID-19 and cognitive impairment: neuroinvasive and blood‒brain barrier dysfunction. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):222.

- Tavares-Junior JWL, de Souza ACC, Borges JWP, et al. COVID-19 associated cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Cortex. 2022;152:77-97.

- Rothenberg E. Coronavirus Disease 19 from the Perspective of Ageing with Focus on Nutritional Status and Nutrition Management-A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(4).

- Fatuzzo I, Niccolini GF, Zoccali F, et al. Neurons, Nose, and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Olfactory Function and Cognitive Impairment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3).

- al Se. Declaración de la Iniciativa STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology): directrices para la comunicación de estudios observacionales. Nefrología. 2009;29(1):11-16.

- Resneck JS, Jr. Revisions to the Declaration of Helsinki on Its 60th Anniversary: A Modernized Set of Ethical Principles to Promote and Ensure Respect for Participants in a Rapidly Innovating Medical Research Ecosystem. JAMA. 2024.

- Kroc L, Fife E, Piechocka-Wochniak E, et al. Comparison of Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 and Subjective Global Assessment Form as Short Nutrition Assessment Tools in Older Hospitalized Adults. Nutrients. 2021;13(1).

- Silva DFO, Lima S, Sena-Evangelista KCM, et al. Nutritional Risk Screening Tools for Older Adults with COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2020;12(10).

- López-Sampalo A, Bernal-López MR, Gómez-Huelgas R. Síndrome de COVID-19 persistente. Una revisión narrativaPersistent COVID-19 syndrome. A narrative review. Revista Clínica Española. 2022;222(4):241-250.

- Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55-64.

- Muccioli L, Sighinolfi G, Mitolo M, et al. Cognitive and functional connectivity impairment in post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Neuroimage Clin. 2023;38:103410.

- Winter AL, Henecke S, Lundstrom JN, et al. Impairment of quality of life due to COVID-19-induced long-term olfactory dysfunction. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1165911.

- Hopkins C, Surda P, Whitehead E, et al. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic - an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):26.

- Gunzer W. Changes of Olfactory Performance during the Process of Aging - Psychophysical Testing and Its Relevance in the Fight against Malnutrition. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(9):1010-1015.

- Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(8):2251-2261.

- Butowt R, von Bartheld CS. Anosmia in COVID-19: Underlying Mechanisms and Assessment of an Olfactory Route to Brain Infection. Neuroscientist. 2021;27(6):582-603.

- Williams FMK, Freidin MB, Mangino M, et al. Self-Reported Symptoms of COVID-19, Including Symptoms Most Predictive of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Are Heritable. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2020;23(6):316-321.

- von Bartheld CS, Hagen MM, Butowt R. Prevalence of Chemosensory Dysfunction in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Reveals Significant Ethnic Differences. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(19):2944-2961.

- Meinhardt J, Radke J, Dittmayer C, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(2):168-175.

- Grund S, Bauer JM. Malnutrition and Sarcopenia in COVID-19 Survivors. Clin Geriatr Med. 2022;38(3):559-564.

- Hummel T, Nordin S. Olfactory disorders and their consequences for quality of life. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125(2):116-21.

- Toller SV. Assessing the impact of anosmia: review of a questionnaire’s findings. Chem Senses. 1999;24(6):705-12.

- Raff AC, Lieu S, Melamed ML, et al. Relationship of impaired olfactory function in ESRD to malnutrition and retained uremic molecules. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(1):102-10.

- Mattes RD. The chemical senses and nutrition in aging: challenging old assumptions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(2):192-6.

- Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, et al. Olfactory impairment in an adult population: the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Chem Senses. 2012;37(4):325-34.

- Toussaint N, de Roon M, van Campen JP, et al. Loss of olfactory function and nutritional status in vital older adults and geriatric patients. Chem Senses. 2015;40(3):197-203.

- Jin SY, Jeong HS, Lee JW, et al. Effects of nutritional status and cognitive ability on olfactory function in geriatric patients. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43(1):56-61.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).