Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results of Quantum Mechanical Calculation

3. Evaluation of Acousto-Optic Efficiency

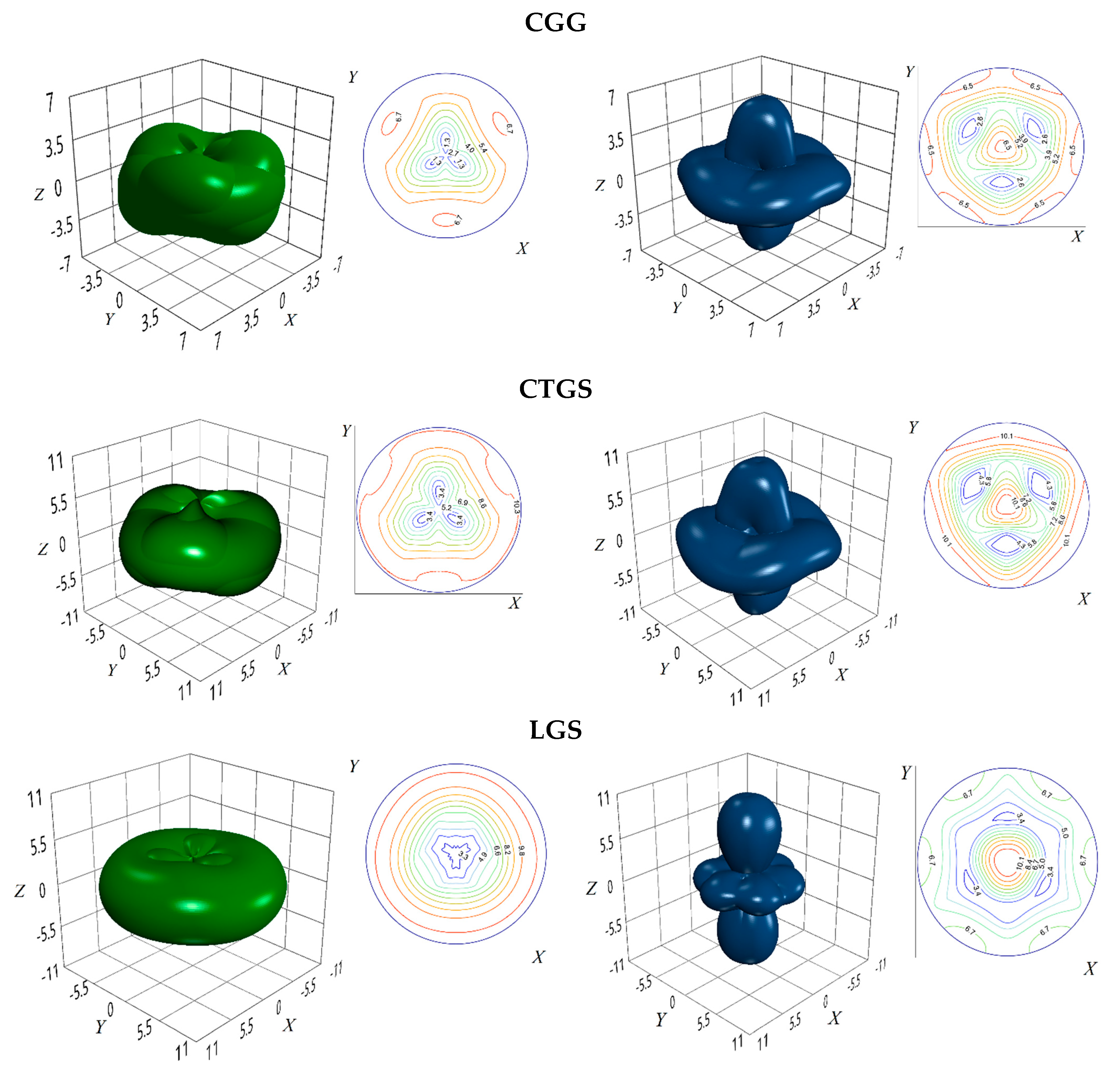

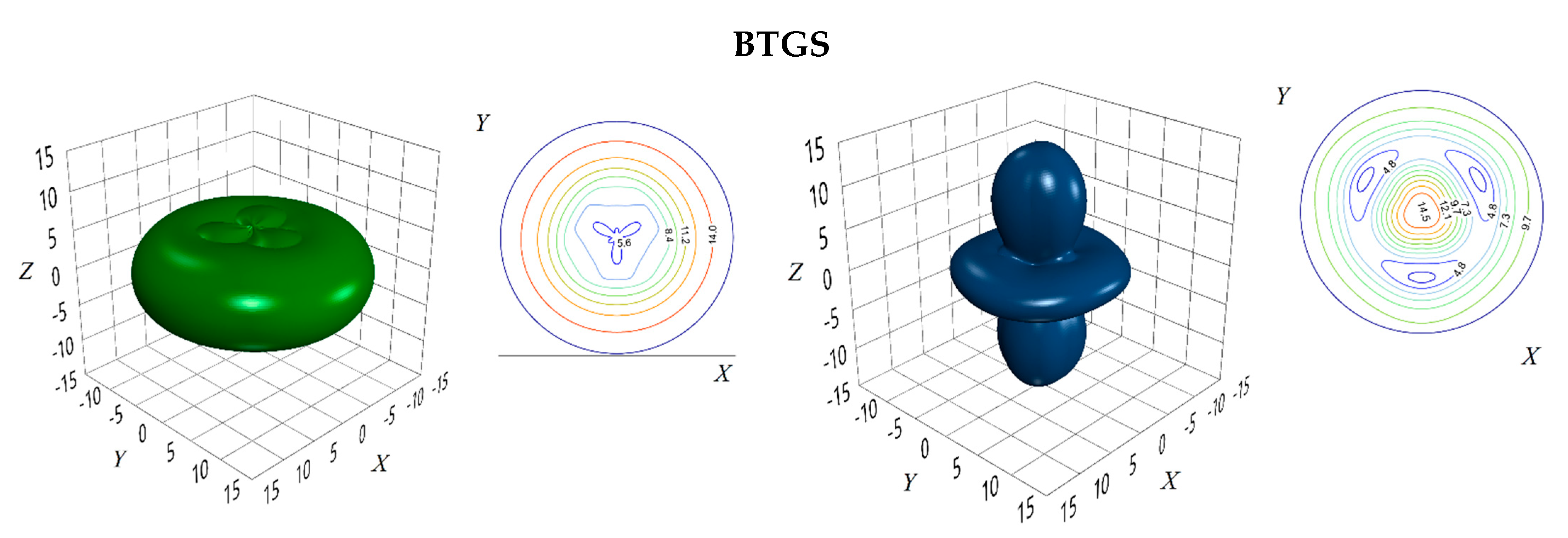

4. Extreme Piezo-Optic Surfaces of the Path Difference

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Remark, T.; Segonds, P.; Debray, J.; Jegouso, D.; Víllora, G.; Shimamura, K.; Boulanger, B. Linear and nonlinear optical properties of the langasite crystal Ca3TaAl3Si2O14. Opt. Mater. Expr. 2023, 13, 20536–20601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, H.; Kusakabe, H.; Tokuda, M.; Sugiyama, K.; Hoshina, T.; Tsurumi, T.; Takeda, H. Structure and electrical properties of Ba3TaGa3Si2O14 single crystals grown by Czochralski method. J. Ceram. Soc. Japan. 2020, 128, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, N.; Klimin, S.; Mavrin, B.; Boldyrev, K.; Chernyshev, V.; Mill, B.; Popova, M. Lattice dynamics and structure of the new langasites Ln3CrGe3Be2O14 (Ln = La, Pr, Nd): Vibration alspectra and abinitio calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Sol. 2020, 138, P109266/1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, I. Two decades following the discovery of thermallys table elastic properties of La3Ga5SiO14 crystal and coining of the term langasite. Tech. Phys. 2004, 49, 1101–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, I.; Dubovik, M. A new piezoelectric material, langasite (La3Ga5SiO14), with a zero temperature coefficient of the elastic vibration frecuency. Sov. Tech. Phys. Lett. 1984, 10, 205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Villora, E.; Matsushita, Y.; Kitanaka, Y.; Noguchi, Y.; Miyayama, M.; Shimamura, K.; Ohashi, N. Influence of growth conditions on the optical, electrical resistivity and piezoelectric properties of Ca3TaGa3Si2O14 single crystals. J. Ceram. Soc. Jap. 2016, 124, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritze, H. High-temperature bulk acoustic wave sensors. Meas. Sci. Techn. 2011, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Shaojun, Z.; Jiyang, W. Mutualaction of the opticalactivity and the electro-opticeffect and itsinf luence on the La3Ga5SiO14 crystal electro-optic Q switch. J. Opt. Soc. America B. 2005, 22, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, N.; Liang, X. Langasite bonding via high temperature for fabricating sealed microcavity of pressure sensors. Micromachines. 2022, 13, 479/1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H. , Wang J., Zhang H., Yin X., Zhang Sh., Ya. Liu Ya., Cheng X., Gao L., Hu X., Jiang M. Growth, properties and application as an electrooptic Q-switch of langasite crystal. J. Cryst. Growth. 2003, 254, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytsyk, B.; Demyanyshyn, N.; Andrushchak, A.; Kost', Ya.; Parasyuk, O.; Kityk, A. Piezooptical coefficients of La3Ga5SiO14 and CaWO4 crystals: A combined optical interferometry and polarization-optical study. Opt. Mat. 2010, 33, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytsyk, B.; Suhak, Y.; Demyanyshyn, N.; Buryy, O.; Syvorotka, N.; Sugak, D.; Ubizskii, S.; Fritze, H. Full set of piezo-optic and elasto-optic coefficients of Ca3TaGa3Si2O14 crystals at room temperature. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 8951–8958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytsyk, B.; Demyanyshyn, N.; Andrushchak, A.; Maksishko, Yu.; Kohut, Z.; Kityk, A. Characterization of photoelastic materials by Mach-Zehnder interferometry: Application to trigonal calcium galogermanate (CGG) crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 135, 085111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chani, V.; Shimamura, K.; Yu, Y.; Fukuda, T. Design of newoxidecrystals with improved structural stability. Rev. J., Mater. Sci. Engin. 1997, R 20, 281–338. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cui, S.-X.; Chen, J.; Tu, X.; Xin, J.; Kong, H.; Shi, E. Advances in design, growth and application of piezoelectric crystals with langasite structure. Proc. 2012 Symp. on Piezoelectricity, Acoustic Waves, and Device Applications (SPAWDA), 23-25 November 2012, Shanghai, China, IEEE Xplore. 2013. 252−259.

- Mytsyk, B.; Andrushchak, A.; Vynnyk, D.; Demyanyshyn, N.; Kost, Ya.; Kityk, A. Characterization of photoelastic materials by combined Mach-Zehnder and conoscopic interferometry: Application to tetragonal lithium tetraborate crystals. Opt. Las. Engin. 2020, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytsyk, B.; Kryvyy, T.; Demyanyshyn, N. ; Mys, O; Martynyuk-Lototska, I. ; Kokhan, O.; Vlokh, R. Piezo-, elasto- and acousto-optic properties of Tl3AsS4 crystals. Applied Optics. 2018, 57, 3796–3801. [Google Scholar]

- Mytsyk, B.; Erba, A.; Maul, J.; Demyanyshyn, N.; Shchepanskyi, P.; Syrotynsky, O. Photoelasticity of CNGS crystals. Appl. Opt. 2023, 62, 7952–7959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyanyshyn, N.; Suhak, Yu.; Mytsyk, B.; Buryy, О.; Маksishko, Yu. ; Sugak, D; Fritze, H. Anisotropy of piezo-optic and elasto-optic effects in langasite family crystals. Opt. Mat. 2021, 119, 111284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytsyk, B.; Demyanyshyn, N. Piezooptic surfaces of lithium niobate crystals. Crystallogr. Rep. 2006, 51, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyanyshyn, N.; Mytsyk, B.; Kost, Y.; Solskii, I.; Sakharuk, O. Elasto-optic effect anisotropy in calcium tungstate crystals. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buryy, O.; Demyanyshyn, N.; Mytsyk, B.; Andrushchak, A. Optimization of the piezooptic interaction geometry in SrB4O7crystal. Opt. Applik. 2016, XLVI, 447–459. [Google Scholar]

- Buryy, O. , Demyanyshyn, N., Mytsyk, B., Andrushchak, A., Sugak, D. Acousto-optic interaction in LGS and CTGS crystals. Opt. Cont. 2022, 1, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytsyk, B.; Andrushchak, A. Spatial distribution of the longitudinal and transverse piezooptical effect in lithium tantalate crystals. Crystallogr. Rep. 1996, 41, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinova, A.; Golovina, T.; Nabatov, B.; Dudka, A.; Mill, B. Experimental and theoretical determination of the optical rotation in langasite family crystals. Cryst. Rep. 2015, 60, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnow, D.; Van, G.; Warner, A.; Bonner, W. Lead molybdate: a melt-grown crystal with a high figure of merit for acousto-optic device applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1969, 15, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R. Photoelastic properties of selected materials and their relevance for applications to acoustic light modulators and scanners. J. Appl. Phys. 1967, 38, 5149–5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, N.; Niizeki, N. Acoustooptic deflection materials and techniques. Proc. IEEE. 1973, 61, 1073–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillman, Jr.W.B. Multimode fiber-optic pressure sensor based on the photoelastic effect. Opt. Let., 1982, 7, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainer, N. Photoelastic measuring transducer and accelerometer based thereon. Patent 4.648.273 US, 10.03.1987.

- Andrushchak, A.; Mytsyk, B.; Osyka, B. Polarized-optical pressure meter. Devices and technique of experiment. 1990, 3, 241. (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. Linear birefringence measurement instrument using two photoelastic modulators. Opt. Eng. 2000, 41, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytsyk, B.; Erba, A.; Demyanyshyn, N.; Sakharuk, O. Piezo- and elasto-optic effects in lead molibdate crystals. Opt. Mat. 2016, 62, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erba, A.; Ruggiero, M.; Korter, T.; Dovesi, R. Piezo-optic tensor of crystals from quantum-mechanical calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perger, W.; Criswell, J.; Civalleri, B.; Dovesi, R. Ab-initio calculation of elastic constants of crystalline systems with the CRYSTAL code. Comp. Phys. Commun. 2009, 180, 1753–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovesi, R.; Saunders, V.; Roetti, C.; Orlando, R.; Zicovich-Wilson, C.; Pascale, F.; Civalleri, B.; Doll, K.; Harrison, N.; Bush, I.; D'Arco, Ph.; Llunel, M.; Causà, M.; Noël, Y.; Maschio, L.; Erba, A.; Rérat, M.; Casassa, S. CRYSTAL17, User Manual, Torino, 2018.

- Erba, A.; Caglioti, D.; Zicovich-Wilson, C.; Dovesi, R. Nuclear-relaxed elastic and piezoelectric constants of aterials: Computational aspects of two quantum-mechanical approaches. J. Comp. Chem. 2017, 38, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erba, A.; Dovesi, R. Photoelasticity of crystals from theoretical simulations. Phys. Rev. 2013; 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.; Erba, A.; El-Kelany, Kh.; Rérat, M.; Orlando, R. Low-temperature phase of BaTiO3: Piezoelectric, dielectric, elastic and photoelastic properties from ab initio simulations. Phys. Rev. 2014, B 89, 045103/1–9.

- El-Kelany, Kh.; Carbonnière, Ph.; Erba, A.; Rérat, M. Inducing a finite in-plane piezoelectricity in graphene with low concentration of inversion symmetry-breaking defects. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015, 119, 8966–8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kelany, Kh.; Carbonnière, Ph.; Erba, A.; Sotiropoulos, J.-M.; Rérat, M. Piezoelectricity of functionalized graphene: A quantum mechanical rationalization. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016, 120, 7795–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laun, J.; Bredow, T. BSSE-corrected consistent Gaussian basis sets of triple-zeta valence with polarization quality of the sixth period for solid-state calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2021, 42, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laun, J.; Bredow, T. BSSE-corrected consistent Gaussian basis sets of triple-zeta valence with polarization quality of the fifth period for solid-state calculations. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.F. Physical properties of crystals. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964.

- Narasimhamurty, T. Photoelastic and electro-optic properties of crystals. New York and London: Plenum press; 1981.

- Dudka, A. Ab Initio calculation of elastic and electromechanical constants of langasite family crystals. Cryst. Rep. 2012, 57, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, W.; Yuan, D.; Wang, X.; Xue, G.; Shi, X.; Xu, D.; Lv, M. Crystal structure of tricacium tantalum trigallium disilicon oxide, Ca3TaGa3Si2O14. Z. Kristallogr. NCS. 2003, 218, 389–390. [Google Scholar]

- Dudka, A. New multicell model for describing the atomic structure of La3Ga5SiO14 piezoelectriccrystal: unitcells of different compositions in the same single crystal. Cryst. Rep. 2017, 62, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudka, A.; Mill, B. Accurate crystal-structure refinement of Ca3Ga2Ge4O14 at 295 and 100 K and analysis of the disorder in the atomic positions. Cryst. Rep. 2013, 58, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, B.; Bustamante, A.; Chout, M. A new class of ordered langasite structure compound Proc. 2000 IEEE/EIA Intern. Frequency Control Symposium and Exhibition (Cat. No.00CH37052). 2000, 9 June. USA. 163–168.

- Mytsyk, B.; Demyanyshyn, N.; Martynyuk-Lototska, I.; Vlokh, R. Piezo-optic, photoelastic, and acousto-optic properties of SrB4O7 crystals. Appl. Opt. 2011, 50, 3889–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buryy, O.; Andrushchak, N. ; Demyanyshyn,N. ; Andrushchak, A. Determination of acousto-optical effect maxima for optically isotropic crystalline materialon the example of GaP cubic crystal. J. Opt. Soc. Amer. B. 2019, 36, 2023–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buryy, O.; Andrushchak, A.; Kushnir, O.; Ubizskii, S.; Yurkevych, O.; Vynnyk, D.; Yurkevych, O.; Larchenko, A.; Chaban, K.; Gotra, O.; Kityk, A. Method of extreme surfaces for optimizing geometry of acousto-optic interactions in crystalline materials: Example of LiNbO3 crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytsyk, B. Methods for the studies of the piezo-optical effect in crystals and the analysis of experimental data. I. Methodology for the studies of piezo-optical effect. Ukr. J. Phys. Opt. 2003, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sirotin, Yu.; Shaskolskaja, M. Fundamentals of crystal physics. Imported Pubn., 1983.

| Cmk | C11 | C12 | C13 | C33 | C14 | C44 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | 166.0 | – | – | – | 6.3 | – |

| [46] ** | 160.5 | 77.4 | 85.5 | 170.9 | 3.03 | 63.3 |

| Our data | 164.9 | 72.0 | 83.6 | 192.0 | –6.38 | 66.3 |

| Skm | S11 | S12 | S13 | S33 | S14 | S44 |

| [46] * | 9.32 | –2.75 | –3.28 | 9.14 | 0.58 | 15.85 |

| Our data | 8.50 | –2.41 | –2.65 | 7.50 | 1.05 | 15.28 |

| π11 | π12 | π13 | π31 | π33 | π14 | π41 | π44 |

| –0.18 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 1.31 | –1.48 | 0.26 | 0.11 | –0.46 |

| p11 | p12 | p13 | p31 | p33 | p14 | p41 | p44 |

| 0.08 | 0.162 | 0.189 | 0.185 | –0.067 | 0.023 | 0.013 | –0.032 |

| Crystal | Light wave | Direction of uniaxial pressure applying | α, deg. |

The global maximum, Br |

||||

| θk, deg. | ϕk, deg. | θi, deg. | ϕi, deg. | θm, deg. | ϕm, deg. | |||

| CGG | 104 | 90 | 90(o), 14 (e) |

0(o), 90 (e) |

90 | 0 | 90 | 6.8 |

| CTGS | 101.3 | 90 | 90(o), 11.3 (e) |

0(o), 90 (e) |

90 | 0 | 90 | 10.4 |

| LGS | 91 | 90 | 90(o), 1 (e) |

0(o), 90 (e) |

−4.5 | 90 | 95.5 | 10.8 |

| Crystal | Light wave | Direction of uniaxial pressure applying | α, deg. |

The global maximum, Br |

||||

| θk, deg. | ϕk, deg. | θi, deg. | ϕi, deg. | θm, deg. | ϕm, deg. | |||

| CTGS | 124 | 90 | 90(o), 35 (е) |

0(o), 90 (е) |

90 | 0 | 90 | 11.0 |

| 155 | 90 | 90(o), 65 (е) |

0(o), 90 (е) |

60 | 90 | 95 | 11.0 | |

| CNGS | 146.4 | 90 | 90(o), 56.4 (e) |

0(o), 90 (e) |

52 | 90 | 94.4 | 11.6 |

| BTGS | 90 | 90 | 90(o), 0 (e) |

0(o), 0 (e) |

2.4 | 90 | 87.6 | 14.5 |

| 90 | 90 | 90(o), 0 (е) |

0(o), 0 (е) |

90 | 0 | 90 | 14.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).