1. Introduction

CRC is the third most prevalent malignancy worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality, accounting for approximately 10% of all cancer deaths globally [

1,

2]. In the United Kingdom (UK), CRC affects over 44,000 individuals annually, with over 16,000 deaths attributed to the disease each year [

3]. Despite advances in early detection and treatment, around 20% of patients present with metastatic or inoperable disease at the time of diagnosis, necessitating palliative interventions to alleviate symptoms and improve QoL [

4].

For patients with advanced CRC, particularly those who are frail or have significant comorbidities, conventional oncologic treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery may be poorly tolerated or contraindicated. Surgical palliation, including colostomy formation or tumor debulking, carries substantial perioperative risks, especially in elderly patients with high ASA scores. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy, while effective in reducing tumor burden, often result in severe systemic toxicity, further compromising patient well-being. Endoscopic palliation, including argon plasma coagulation (APC) and stenting, offers alternatives for symptom relief but may have limited efficacy, particularly for some bleeding ulcerated lesions [

5] or locally infiltrative tumors distal to the recto-sigmoid junction [

6].

Given these challenges, there is a pressing need for innovative, minimally invasive palliative therapies that can improve outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.

Calcium-electroporation (Ca-EP) is an emerging, non-thermal tumor ablation technique that utilizes short, high-voltage electric pulses to transiently permeabilize cell membranes, allowing for the influx of supra-physiological levels of calcium ions [

7]. The resulting intracellular calcium overload triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to rapid energy depletion and subsequent cell death through apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis [

8]. Unlike chemotherapeutic agents, Ca-EP exploits a fundamental biochemical vulnerability of cancer cells—an impaired ability to regulate calcium homeostasis—while sparing surrounding healthy tissues [

7]. The mechanism of Ca-EP induced tumor cell death, particularly its immunogenic effects [

9], is an area of additional interest in the scientific community. Unlike thermal ablation techniques, which cause coagulative necrosis with limited immunogenicity, the potential of Ca-EP inducing a form of immunogenic cell death that promotes local immune activation, is currently being investigation.

The therapeutic potential of Ca-EP has been demonstrated in preclinical and clinical studies, primarily in cutaneous malignancies and soft tissue sarcomas. Recent studies evaluating Ca-EP for the treatment of cutaneous metastases have shown significant tumor regression with minimal adverse effects [

10]. Other studies have explored its application in pancreatic and head-and-neck cancers, suggesting a broader oncologic utility [

11,

12], while teams in Ireland and Denmark have explored Ca-EP for palliative treatment of gastrointestinal cancer [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. CRC, particularly in its advanced stages, presents with distressing symptoms such as rectal bleeding, pain, bowel obstruction, and tenesmus [

4]. For frail patients who are unsuitable for surgery or systemic therapy, endoscopic palliation provides a valuable means of symptom control while avoiding the morbidity associated with more invasive interventions. The adaptation of Ca-EP for endoscopic delivery in CRC is a logical extension of its therapeutic potential, offering a targeted approach to tumor ablation while preserving bowel integrity. Despite being considered innovative, Ca-EP is not an experimental technique, and is known to be used clinically for treatment of GI cancer in hospitals across the UK [

19], Spain [

20,

21], Italy [

22] and Germany [

23].

However, there is a paucity of published data on endoscopic Ca-EP in CRC. This study aims to assess its safety, feasibility, and palliative efficacy in frail patients with inoperable left-sided colon and rectal cancer. By assessing symptom relief, QoL improvements, and survival outcomes, we seek to establish a foundation for future research into the integration of Ca-EP as a standard palliative modality for CRC.

2. Materials and Methods

Setting

Patients included in this case series were treated at King’s College Hospital London, a major referral centre in the UK, between 2022 and 2024. Those treated were frail patients diagnosed with inoperable, locally symptomatic left-sided CRC undergoing endoscopic Ca-EP as a palliative intervention in a real-world clinical setting. Prior to treatment, all patients consented to the use of their data to be used in current or future studies. The protocol was approved by the New Clinical Procedures committee of King’s College Hospital (KCH) for ethics and endorsed by the Multidisciplinary teams of the South East London Cancer Alliance (SELCA) Network. Ethics was waived as the review was considered to be an audit of clinical practice in line with the guidelines for KCH National Health Service (NHS) trust

Eligibility

Adult patients discussed by the multidisciplinary team (MDT) were considered for the study if they met the following criteria: Histologically confirmed CRC with a lumen passable by an endoscope; symptomatic local disease, including tumor-related bleeding, pain, tenesmus, or subacute obstruction; unsuitable for surgical resection or conventional oncologic treatments (chemotherapy, radiotherapy) due to frailty, comorbidities, or patient preference; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status ≥3; ASA score of ≤5; CCI ≥ 10. Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: Pregnant or breastfeeding; had implanted colorectal stents; had severe coagulation disorders (INR>2, Platelet count <50,000 per microliter of blood), had highly inflamed colonic mucosa; had cardiac devices (e.g. pacemakers, implantable defibrillators) that could not be deactivated for more than 30 minutes.

Once patient eligibility was determined following MDT discussion, informed consent was obtained before enrolment. The MDT, which also included a patient advocate, provided governance and oversight of in the care of these potentially vulnerable patients on a case-by-case basis.

Pre-Procedure Evaluation

All patients underwent a structured preoperative assessment, including full medical history (emphasizing comorbidities, prior oncologic treatments, and contraindications to lower GI endoscopy); Physical examination, including digital rectal examination where necessary; Laboratory investigations, including full blood count (within one week of procedure), coagulation profile (within 24 hours of procedure), renal function tests. Bowel preparation was initiated as per institutional colonoscopy guidelines and included oral laxatives ± rectal enemas on arrival at the endoscopy suite. One the day of the procedure, intravenous access (IV) was established for sedation and fluid administration if required. Sedation requirements were determined on an individual basis and were sometimes omitted at the request of the patients. The typical medications given were fentanyl with or without midazolam. General anesthesia was not used and antispasmodic agents (e.g. hyoscine butylbromide) were used selectively.

Endoscopic Calcium Electroporation Protocol

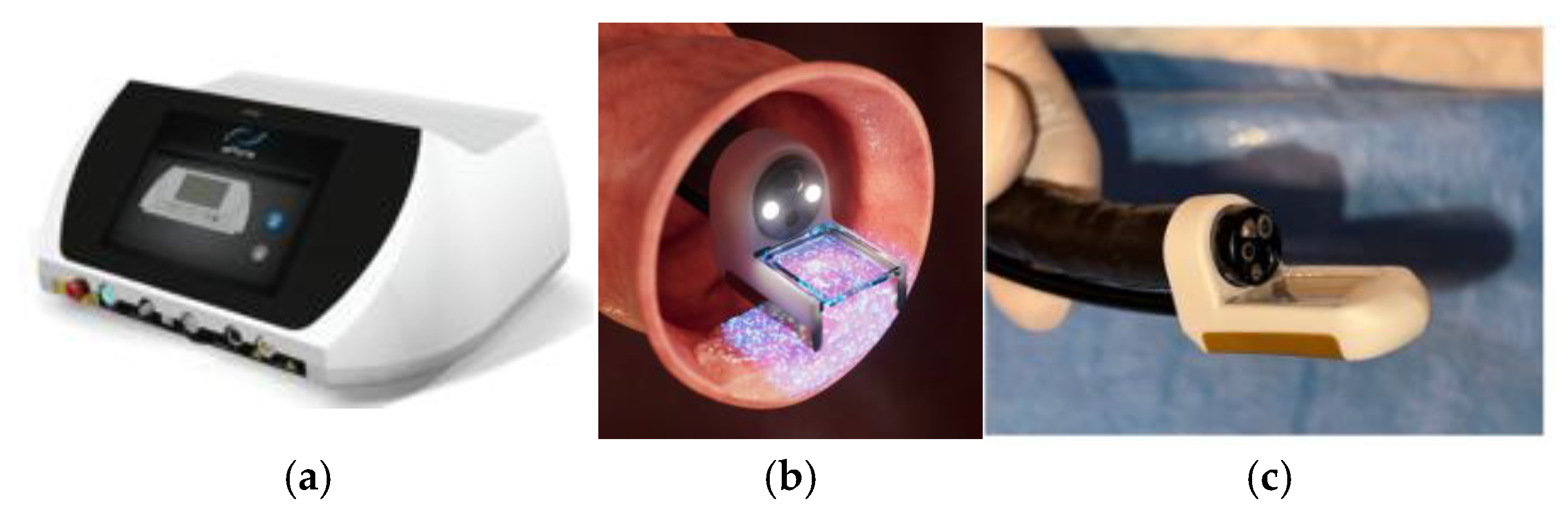

Ca-EP was performed using the Conformité Europénne (CE) marked and Medical Device Directive (MDD) certified (2027/MDD) ePORE® electroporation generator and single use CE marked EndoVE® probe (Mirai Medical, Galway, Ireland). The procedure was carried out in an outpatient setting under sedation, following standard endoscopy protocols. The EndoVE® probe was attached to the ePORE® generator using an extension lead that was pre-programmed with the parameters required to deliver the pulsed electric fields required for the electroporation of tissue. The EndoVE® probe was also connected to a vacuum which facilitated the tumour tissue being held in place withing the chamber of the probe, for the duration of pulse delivery.

Equipment and Materials: ePORE® generator (

Figure 1) with pre-programmed extension lead; EndoVE® probe (

Figure 1) with vacuum-assisted tumour engagement; endoscopic injection with vacuum-assisted tumour engagement; endoscopic injection needle (4mm) and 10 mL syringe; 10% calcium gluconate ampoules (preferred over calcium chloride for its superior hemostatic properties and reduced tissue electrical impedanace); high-suction vacuum system (>400 mmHg); standard flexible gastrointestinal endoscope with a tip diameter <11mm (e.g gastroscope or paediatric colonoscope) to conform with the size of the EndoVE® probe.

Procedural Steps:

Patient positioning and monitoring: Patients were positioned in the left lateral decubitus position (but modified as necessary). Vital signs, including oxygen saturation and heart rate were continuously monitored and supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula was provided in accordance with British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines.

Initial Endoscopic Assessment: Endoscopic assessment was performed using a lubricated gastrointestinal endoscope (10-11mm diameter) to determine the site, size and other morphological characteristics of the tumour.

Calcium Injection: Calcium was injected into the tumour prior to each application of the pulsed electric fields. This was achieved by introducing the endoscopic injection needled through the working channel of the endoscope and injecting the calcium gluconate (10%; ≤10mL per session). Injection volume was determined based on tumour size and vascularity, ensuring even distribution.

Electroporation Delivery: The EndoVE® probe was mounted on the tip of the endoscope and advanced to the tumour site. The probe was activated with high-suction vacuum engagement to maximise tumour contact. Pulsed electric fields (1cm penetration depth, 2cm3surface area coverage) were delivered. The pulses were applied after each calcium injection and was followed by repeated application as required until all available surface area was treated. Key procedural parameters were recorded, including tumour location and size; estimated percentage of tumour surface treated; volume of calcium gluconate injected; number of pulses delivered; maximum applied current and lowest tissue impedance.

Completion and withdrawal: the probe was disengaged by turning off the vacuum, and the endoscope was carefully withdrawn. Patients were observed for at least 30 minutes post-procedure before discharge.

Post-procedure care and follow-up: Patients were monitored according to standard endoscopy post-procedure protocols. All patients were discharged on the day of treatment, however there was a provision for overnight observation if clinically indicated, due to the high-risk profile of the patients. Routine outpatient follow-up was scheduled withing 4 weeks for symptom assessment and repeat imaging if necessary. Subsequent Ca-EP sessions were performed as required and at varying intervals, depending on symptom recurrence and clinical response.

Outcome Measures: Primary endpoints were symptom relief (e.g. reduction in rectal bleeding, pain and constipation); QOL assessed via the 12 Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) Questionnaire for patient reported outcomes; safety, including the incidence of treatment-related adverse events; and tumour response. Secondary endpoints were reduction in blood transfusion requirements for hemorrhagic tumours; and overall survival (OS) at 6- and 12-months post-treatment. The data was prospectively collected and retrospectively analyzed.

Statistical Analysis: descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline demographics, procedural data, and clinical outcomes. Symptom relief was evaluated using patient-reported measures and clinician assessment at follow-up visits. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier methods.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Sixteen patients (10 male; 6 female) were enrolled in the study and underwent a total of 36 endoscopic Ca-EP sessions over a 28-month period (2022–2025). The median age was 84.5 years (range: 63–92 years), and all patients were classified as frail based on clinical assessment. The majority of patients (56%, n=9) had metastatic disease, while 25% (n=4) had previously failed conventional oncologic treatments (

Table 1).

All patients had a poor performance status, with an ECOG Performance Status of ≥3, an ASA score of 5, and an average CCI of 15, indicating a 0% estimated 10-year survival. The main indications for Ca-EP treatment were symptomatic relief for rectal bleeding (75%, n=12), constipation (25%, n=4), and pain (68.75%, n=11).

3.2. Primary Endpoints

3.2.1. Safety Assessment

No intra or post operative serious adverse events (SAEs) or device related adverse events (AEs) were reported. There were no cases of colonic perforation, severe bleeding requiring intervention, infection, or post-procedural complications requiring hospitalization. Minor adverse events unrelated to the device included mild discomfort or transient rectal irritation in 3 patients (19%), which resolved within 24–48 hours. Patient reported self-limiting rectal bleeding occurred in 2 subjects (12%) on anticoagulants and antiplatelet medication following the procedure and this did not require additional treatment. One patient (Patient 14) experienced an episode of labile hypotension related to the effects of anti-hypertensive medication immediately after the 1st procedure under sedation. This phenomenon did not reoccur in subsequently after modification of the relevant medications.

Three of the 16 patients (19%) have died; one as a result of metastatic disease, and two for reasons unattributed to their cancer. None of the reported deaths were device related.

3.2.2. Symptomatic Response

All patients who were symptomatic resulting from their disease prior to treatment experienced a symptomatic response (

Table 2). Bleeding/anemia (75%) and pain (75%) were the most common symptoms reported, followed by constipation. Of the 12 patients who reported bleeding/anemia prior to treatment, 75% (n=9) had permanent cessation of bleeding or a rise in hemoglobin levels which have sustained within a normal range, following treatment, though one patient required two treatments to achieve permanent cessation. Bleeding cessation has sustained for between 3 and 30 months. Approximately 16.66% (n=2) had temporary cessation of bleeding, where the approximate duration between treatment and bleeding recurrence ranged from between 4 and 9 months, and follow up for one patient (6.25%) was pending. All patients who had a recurrence of bleeding received additional Ca-EP treatment for symptom control. Of the 12 patients who presented with bleeding/anemia, two had previously received radiotherapy. Of these two patients, one (Patient 6) had a complete symptomatic response; she was asymptomatic with stable hemoglobin levels 10 months after a single Ca-EP treatment and the second (Patient 13) also reported a symptomatic response for bleeding following a single Ca-EP treatment.

Eleven patients (68.75%) also reported disease-related pain prior to their initial treatment, and all reported sustained improvement of pain after a single treatment as evidenced by reduced analgesic requirements. Of the four patients who experienced constipation as a symptom of their disease, 75% (n=3) had a complete symptomatic response (range 2 month – 18 months). One patient reports the use of occasional laxatives. Other symptoms that responded to Ca-EP treatment were tenesmus (n=1), change in movements (n=2) and bloating/flatulence (n=1). Two patients experienced diarrhea prior to treatment, which improved following a single Ca-EP treatment. Two patients (11 and 13) reported distressing mucoid discharge. Patient 11 reported a 50% reduction in mucus discharge after his initial treatment and a complete cessation of symptoms following a second treatment, one month later. Patient 13 reported complete cessation of symptoms following one treatment. One patient had incontinence prior to treatment attributed to co-existing Multiple sclerosis, which has persisted following Ca-EP therapy.

3.2.3. Quality of Life Assessment Response

The impact of the treatment on patients’ QOL was assessed using the SF-12 Questionnaire which evaluates physical and mental domains. The questionnaire was administered before initial treatment and within the first week following Ca-EP. Twelve patients were able to respond to the questionnaire. Three patients were unable to give a response due to dementia while 1 patient (Patient 12) declined. Ten patients of the 12 respondents reported improvement in their QOL. The average change in the physical component summary domain was +23 while that of the mental component summary was +11.5. These values suggest improvement in both physical and mental wellbeing. Two patients reported no change in the SF-12 survey.

3.2.4. Tumour Response

Eight patients received a single Ca-EP treatment, and 8 patients had multiple treatments (between 2 and 5). The number of treatments per patient was determined by the clinical team based on factors such as, patient suitability and willingness to undergo multiple treatments, tumour response and symptomatic relief to previous treatment(s). Approximately 43.75% of patients had cancer of the sigmoid colon (n=7). Rectal cancer was the next most common indication (37.5%; n=6) followed by recto-sigmoid (12.5%; n=2) and descending colon cancer (6.25%; n=1). The number of treatments per indication translated totaled 19 sigmoid colon treatments (53%), followed by 12 rectal (33%), 4 recto-sigmoid (11%) and 1 descending colon (3%).

In the 75% of patients who returned for endoscopic assessment (n=11) or for whom CT confirmation of tumour response was available (n=1), the overall tumour response rate was 83.3% (n=10) (

Table 3). One patient (Patient 7) had a complete clinical response after one treatment, based on CT reporting. This patient did not return for endoscopic review. Approximately 56% (n=9) of patients experienced a sustained tumour response. However, Patient 9’s tumour increased after the initial treatment and decreased following subsequent treatments. For one patient (Patient 3), the response was transitory, with a reduction in tumour size following the first Ca-EP treatment, but an increase following subsequent treatments, indicating disease progression. For Patient 4, who received multiple treatments for symptomatic bleeding, there was a plateau in tumour response following the fourth treatment. Sixteen months after initial treatment, her symptoms indicated disease progression. At the time of report writing this patient is awaiting endoscopic assessment. Three patients (19%) reported symptomatic relief and chose not to return for endoscopic assessment, thus tumour response could not be assessed. Stable disease was reported for two patients (13%), each of whom received a single Ca-EP treatment, and one patient (6%) declined to return for further treatment or follow up.

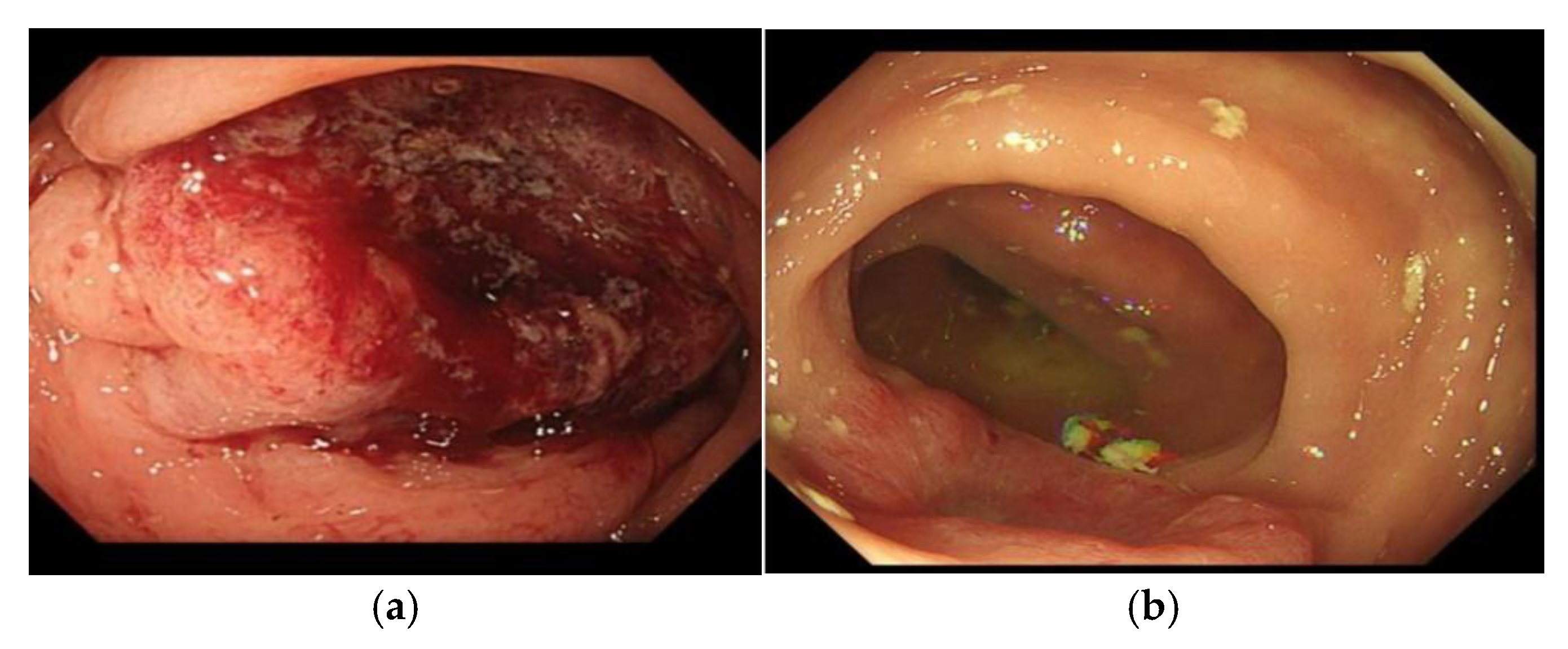

Figure 2.

(a) Patient 5; image of pre-treatment tumour; (b) Patient 5; image of tumour 5 months after a single session of Ca-EP. This patient went on to have multiple Ca-EP treatments.

Figure 2.

(a) Patient 5; image of pre-treatment tumour; (b) Patient 5; image of tumour 5 months after a single session of Ca-EP. This patient went on to have multiple Ca-EP treatments.

3.3. Secondary Endpoints

3.3.1. Overall Survival (OS)

At the time of reporting, the overall response rate is 81.3% (n=13), and the per-patient median survival was 10 months (1-29). Ten patients have reached the 6 month follow-up milestone, at which point all (100%) were alive. The OS at 12 months was 80%. Patients 1-5 have reached the 12 month follow-up milestone, at which time 4 were alive while one patient (Patient 2) who received a single Ca-EP treatment died 11 months later, due to metastatic disease. Patient 8 died 9 months after treatment and Patient 3 died outside of the 12 month follow-up window. The cause of death was related to their comorbidities. Patients 11-16 had their first Ca-EP treatment in 2025, thus have not yet reached the OS reporting milestones.

3.3.2. Reduction in Blood Transfusion and Iron Requirements

Twelve patients required iron infusions and/or blood transfusions on account of symptomatic anemia prior to Ca-EP treatment. Overall, 91.7% (n=11) of patients no longer required treatment for anemia following Ca-EP therapy. Following treatment, one patient (Patient 5) required an iron infusion 8 weeks after his initial Ca-EP treatment. He went on to have additional Ca-EP treatments and had no further bleeding symptoms or requirements for infusions.

4. Discussion

This study presents the first UK case series evaluating endoscopic Ca-EP as a palliative treatment for frail patients with inoperable CRC. Recent data suggests that the number of such patients is on the rise [

24,

25], and this poses a challenge to clinicians and MDTs when determining the best course of individualized action particularly in settings where therapeutic nihilism is the potentail norm for these cases. Our study findings suggest that Ca-EP is a safe, well-tolerated and effective option for symptom relief, particularly in patients who are unsuitable for conventional oncologic therapies. This correlates with findings from international teams who have concluded that Ca-EP is safe and has proven effective for tumour debulking and palliation of disease related symptoms [

13,

14]. The median age of patients treated was 84.5 years, with 94% (n=15) of patients aged 79 or older. These elderly patients are often too frail or comorbid for surgery, or are unwilling to undergo surgery due to potential risks and side effects (e.g. colostomy) [

4]. A recent, unpublished retrospective review was conducted at KCH, of historical data (2013-2022) for patients with confirmed colorectal cancer who were considered for palliative treatment following MDT review. The median age of the patients included in the review (n=267) was 74.7 years and approximately 60% of patients had an ECOG performance status of 2 at diagnosis [

26]. When compared to the data from our study, both the lower median age and better performance status of these patients suggest that those patients may have benefitted from Ca-EP as part of their treatment regimen, had it been available in our setting at the time.

The high rate of symptom relief (86.7%), significant reduction in rectal bleeding and decrease in blood transfusion as well as iron infusion requirements (91.7.%) highlight the potential role of Ca-EP as a valuable addition to the palliative treatment landscape for CRC. These correlate with the findings from Broholm et al., where 90% (10/11) of patients who had disease related bleeding prior to treatment reported cessation of bleeding within 2 days following treatment [

15]. Hansen et al also reported similar findings using bleomycin instead of calcium during electroporation [

14]. There is a possibility that better responses would have been seen had IV bleomycin been used in place of calcium gluconate, particularly for patients with extensive, bulky or bleeding tumours. The significance of this is particularly impactful for patients who required multiple transfusions/infusions before receiving Ca-EP treatment. Patient 5, for example, received 4 units of blood transfusion in the 4 months between diagnosis and treatment with Ca-EP. These required 2 separate in-patient admissions, each lasting 48 hours. He also received multiple iron infusions during this time. These infusions require multiple hospital trips (one or two per week). The frequency of transfusions as well as the requirement for inpatient hospitalization for each infusion puts additional financial costs and burden on an already strained health service. Following Ca-EP treatment, his GI bleeding subsided, the blood counts remained stable and there was no need for transfusions after therapy. He had a single dose of iron infusion and erythropoietin 10 weeks later from anemia due to chronic kidney disease. The positive responsive rate seen in bleeding suggests that endoscopic Ca-EP could help improve patient’s quality of life and reduce the burden such patients pose to the health system.

Chemotherapeutic regimens such as FOLFIRI and FOLFOX4 are typically used in the treatment of non-frail patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer. These patients are often unsuitable for the patient population in this study, mainly due to systemic toxicity, leading to significant morbidity and potential mortality. The lack of systemic side effects and the relative safety of Ca-EP makes it an attractive potential option in scenarios where chemotherapy is not possible. For frail patients with inoperable CRC, standard palliative interventions include systemic therapy which is often poorly tolerated in these individuals due to significant toxicity. Surgical palliation (diverting colostomy, tumor debulking) is another option for obstructing/bulky tumours but can be associated with high perioperative risks, particularly in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. Where surgical palliation is considered, Ca-EP can be considered as a neoadjuvant treatment for tumour debulking. Brohlom et al. investigated this treatment option in their recent study. The majority (90%; n=19) of patients in that study had surgery as scheduled, following Ca-EP treatment, while scheduled surgery was delayed for two patients [

15]. In addition, other endoscopic techniques such as colonic stenting, APC or laser therapy can be effective in some cases but limited in patients with diffuse or bleeding tumors as well as lesions distal to the recto-sigmoid junction [

5,

6]. Due to the side effects, recovery times and impact on patients’ QOL, a recent study suggested that it may be more beneficial for frail, inoperable patients to be referred for best supportive care, in lieu of standard of care interventions such as those outlined above [

27]. In such cases, Ca-EP could be a worthwhile adjunct to best supportive care by improving the QOL of these patients, as indicated by the 83.3% of patients surveyed who reported an improvement in their QOL following Ca-EP treatment.

Compared to these approaches, Ca-EP offers several distinct advantages. It is a minimally invasive outpatient-based procedure which is performed under sedation via flexible endoscopy, avoiding the need for general anesthesia or hospitalization. This is particularly important for frail patients with high ASA or CCI scores who are at significant risk of perioperative complications. We also noticed sustained symptom control in most patients. While most patients required multiple sessions (mean: 2.1 per patient) the procedure was well tolerated and effectively maintained symptom relief over time. The ability to repeat the procedure every 2–3 months, or more frequently if indicated, provides ongoing palliation without cumulative toxicity. Unlike thermal ablation techniques (e.g., APC or laser therapy), which carry risks of mucosal damage and perforation, Ca-EP spares surrounding healthy tissue, reducing the likelihood of major complications [

7]. Furthermore, the absence of device-related adverse events underscores its safety, making it an ideal option for frail patients who cannot tolerate aggressive intervention. Patient 14 experienced an episode of hypotension immediately following Ca-EP treatment, however upon further validations, it was determined that this was due to anti-hypertensive medications that the patient was taking. After review of the medication by a cardiologist, the patient was deemed fit to receive additional Ca-EP and no hypotension was observed in subsequent sessions.

The inclusion of Ca-EP as a treatment modality for these patients offers them treatment options where they may not otherwise have one, as well as the potential to extend their life expectancy and improve their QOL with the palliation of symptoms. Moreover, treatment with Ca-EP does not preclude patients from being treated with standard interventions (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, surgery) if required. Though the scientific and medical communities are still building the volume of evidence required to increase awareness of Ca-EP treatment, it has been shown to be both safe and effective, as demonstrated by this study. The CRC MDT at King’s College Hospital as well as the SELCA Network felt that this therapy was safe and feasible in this category of patients and provided governance and oversight. These bodies also have patient advocates as members and this was important in ethical regulations of this treatment in these potentially vulnerable patient group.

Emerging evidence suggests that treatment with electroporation can stimulate anti-tumor immune responses by inducing immunogenic cell death (ICD) in pancreatic and prostate cancers [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The reporting of this phenomenon is most common in relation to irreversible electroporation (IRE). However Broholm et al. plan to explore if Ca-EP can produce similar findings when used in the neo-adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer [

15]. Should they find that the immunogenic effects of Ca-EP mirror those of IRE, future research could explore combination strategies with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) to enhance systemic anti-tumor immunity and the potential of Ca-EP to induce systemic tumor regression in metastatic CRC [

32].

Limitations of the Study

Despite the promising findings, this study has important limitations that warrant careful interpretation. The small sample size (n=16), absence of a comparator arm, and descriptive study design, limit the strength of causal inferences. Although we observed median cancer-specific survival of 10 months, the lack of matched controls as well as the relatively short follow up precludes definitive statements regarding efficacy. The lack of comparison with standard endoscopic palliation (e.g., APC or stenting), or best supportive care is also a major limitation. Our inability to establish a longitudinal assessment of the durability of response symptomatic relief and long-term safety is also important to consider. Additionally, the heterogeneity in tumor biology and disease stage could be responsible for the variability in tumour response rates.

Future Studies

Future studies should include randomized comparative studies which compare Ca-EP with standard palliative treatments (e.g., APC, stenting, palliative radiotherapy). which stratify patients based on tumour location, burden, and molecular profile.

Larger, multi-center randomised trials are required to assess the outcomes of Ca-EP across a larger patient populations to reflect a diversity in patient demographics including age, frailty and ethnicity. These studies would serve to evaluate long-term outcomes, including survival beyond 12 months and potential late toxicities. The possible hypothesis that Ca-EP may have synergistic role in combination with immunotherapy needs to be proven to determine if it has potential systemic anti-tumor effects. This may be of benefit particularly in patients with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) tumors due to enhanced immune engagement. This will serve as motivation for further translational research and the role of biomarkers in this novel therapy. Tumor biology, technical factors related to the procedure as well as appropriate Time-intervals between treatment sessions, are potential determinants of cancer response to Ca-EP.

Health economic studies to assess if there is a cost benefit in treating patients with Ca-EP, when compared with the cost of other modalities (e.g. chemotherapy, radiotherapy) particularly with regard to bleeding control may also be beneficial.

5. Conclusions

Based on the findings of our review, we conclude that Ca-EP is a safe, potentially effective and repeatable treatment option for frail patients with inoperable CRC who are unsuitable for conventional oncologic therapy. The majority of patients in the study reported an improved quality of life and sustained improvement in the palliation of disease related symptoms such as bleeding, pain and constipation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and A.A.; methodology, A.H. and A.A.; software, not applicable; validation, A.H. and O.O.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, A.H. and A.A.; resources, not applicable; data collection, H.A.,A.Eq, C.J, H.G. and A.S.; data curation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, A.Em., B.H, and A.H..; project administration, not applicable; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval was waived for this study due to the approval of the study by the New Clinical Procedures Committee of Kings College Hospital. No patient identifiers have been used.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to patient confidentiality and GDPR.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AE |

Adverse Event |

| APC |

Argon Plasma Coagulation |

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BSG |

British Society of Gastroenterology |

| Ca-EP |

Calcium Electroporation |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CE |

Conformité Europénne |

| CRC |

Complex Colorectal Cancer |

| ECOG |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| IV |

intravenous |

| MDD |

Medical Device Directive |

| MDT |

Multidisciplinary Team |

| NHS |

National Health Service |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| PFS |

Performance Status |

| QOL |

Quality of Life |

| SAE |

Serious Adverse Event |

| SELCA |

South East London Cancer Alliance |

| |

|

References

- Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023 Feb;72(2):338-344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024; 74(3): 229-263. [CrossRef]

- https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer, accessed April 2025.

- Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2021 Feb 16;325(7):669-685. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong QH, Liu ZZ, Yuan ZX, Ma TH, Huang XY, Wang HM, Chen DC, Wang JP, Wang L. Efficacy and complications of argon plasma coagulation for hemorrhagic chronic radiation proctitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Apr 7;25(13):1618-1627. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seo SY, Kim SW. Endoscopic Management of Malignant Colonic Obstruction. Clin Endosc. 2020 Jan;53(1):9-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frandsen, S.K.; Vissing, M.; Gehl, J. A Comprehensive Review of Calcium Electroporation—A Novel Cancer Treatment Modality. Cancers 2020, 12, 290. [CrossRef]

- Batista Napotnik T, Polajžer T, Miklavčič D. Cell death due to electroporation - A review. Bioelectrochemistry. 2021 Oct;141:107871. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anna Szewczyk, Dagmara Baczyńska, Anna Choromańska, Zofia Łapińska, Agnieszka Chwiłkowska, Jolanta Saczko, Julita Kulbacka,Advancing cancer therapy: Mechanisms, efficacy, and limitations of calcium electroporation,Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer,Volume 1880, Issue 3,2025,189319,ISSN 0304-419X. [CrossRef]

- Ágoston D, Baltás E, Ócsai H, Rátkai S, Lázár PG, Korom I, Varga E, Németh IB, Dósa-Rácz Viharosné É, Gehl J, Oláh J, Kemény L, Kis EG. Evaluation of Calcium Electroporation for the Treatment of Cutaneous Metastases: A Double Blinded Randomised Controlled Phase II Trial. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Jan 10;12(1):179. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rudno-Rudzińska J, Kielan W, Guziński M, Płochocki M, Antończyk A, Kulbacka J, New therapeutic strategy: Personalization of pancreatic cancer treatment-irreversible electroporation (IRE), electrochemotherapy (ECT) and calcium electroporation (Ca-EP) – A pilot preclinical study, Surgical Oncology, Volume 38,2021,101634, ISSN 0960-7404. [CrossRef]

- Plaschke CC, Gehl J, Johannesen HH, Fischer BM, Kjaer A, Lomholt AF, Wessel I. Calcium electroporation for recurrent head and neck cancer: A clinical phase I study. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2019 Jan 3;4(1):49-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Broholm M, Vogelsang R, Bulut M, Stigaard T, Falk H, Frandsen S, Pedersen DL, Perner T, Fiehn AK, Mølholm I, Bzorek M, Rosen AW, Andersen CSA, Pallisgaard N, Gögenur I, Gehl J. Endoscopic calcium electroporation for colorectal cancer: a phase I study. Endosc Int Open. 2023 May 9;11(5):E451-E459. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Falk Hansen H, Bourke M, Stigaard T, Clover J, Buckley M, O'Riordain M, Winter DC, Hjorth Johannesen H, Hansen RH, Heebøll H, Forde P, Jakobsen HL, Larsen O, Rosenberg J, Soden D, Gehl J. Electrochemotherapy for colorectal cancer using endoscopic electroporation: a phase 1 clinical study. Endosc Int Open. 2020 Feb;8(2):E124-E132. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Broholm M, Vogelsang R, Bulut M, Gögenur M, Stigaard T, Orhan A, Schefte X, Fiehn AMK, Gehl J, Gögenur I. Neoadjuvant calcium electroporation for potentially curable colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2024 Feb;38(2):697-705. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egeland C, Baeksgaard L, Johannesen HH, Lӧfgren J, Plaschke CC, Svendsen LB, Gehl J, Achiam MJ. Endoscopic electrochemotherapy foresophageal cancer: a phase I clinical study. Endoscopy International Open 2918; 06: E727-E734. [CrossRef]

- Egeland C, Baeksgaard L, Gehl J, Gӧgenur I, Achiam MP. Palliative treatment of esophageal cancer using calcium electroporation. Cancers 2022,14, 5283. [CrossRef]

- Egeland C, Baeksgaard L, Gehl J, Gӧgenur I, Achiam MP. Endoscopic-assisted electrochemotherapy versus argon plasma coagulation in non-curable esophageal cancer – a randomized clinical trial. Medical Research Archives 2023. [CrossRef]

- Beintaris I, Abdulhannan P, Etherson K, Jacob J. Calcium electroporation for palliation of colorectal cancer. ESGE Days 2025. Barcelona Spain 03 – 05 April 2025.

- Gómez-ó Gómez A, Romero-Martinez M, Fernández-Nievas R, Sánchez-Roncero FJ, Bógalo-Romero C, Madrigal-Bayonas L, Calatayud-Vidal G, Egea-Valenzuela J. Successful management of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding in metastatic cholangiocarcinoma using calcium electroporation. ESGE Days 2025. Barcelona Spain 03 – 05 April 2025.

- Rodriguez HN, Martinez EV, Cuevas CM, Crespo ASJ, Redondo PD. Endoscopic Electroporation for controlling bleeding and stenosis secondary to digestive tract cancer: experience in a tertiary hospital. ESGE Days 2025. Barcelona Spain 03 – 05 April 2025.

- Agazzi S, Cappellini A, Rovedatti L, Mazza S, Mauro A, Pozzi L, Delogu C, Scalvini D, Ravetta V, Anderloni A. Calcium electroporation as palliative treatment in esophageal cancer: a case report. ESGE Days 2025. Barcelona Spain 03 – 05 April 2025.

- Taher A, Rey J. Endoscopic electroporation, first experience in a German endoscopy center. ESGE Days 2024. Berlin Germany 25 – 27 April 2024.

- Carlisle JB. Pre-operative co-morbidity and postoperative survival in the elderly: Beyond one lunar orbit. Anaesthesia. 2014.

- Cancer Research. Bowel cancer statistics | Cancer Research UK [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer.

- Adeyeye A, Saini A, Gao H, Haji A. Colorectal Cancer Survival in Patients Without Curative Measures: A Retrospective Cohort Review;2025 (unpublished).

- Franklyn J, Poole A, Lindsey I. The Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 2024, Volume 106, p 592-595.

- He C, Wang J, Sun S, Zhang Y, Li S. Immunomodulatory effect after irreversible electroporation in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. J Oncol 2019: 2019: 9346017. [CrossRef]

- He C, Huang X, Zhang Y, Lin X, Li S. T-cell activation and immune memory enhancement induced by irreversible electroporation in pancreatic cancer. Clin Transl Med 2020. 10:E39.

- Zhao J, Wen X, Tian L, Xu C, Wen X, Melancon MP, Gupta S, Shen B, Peng W, L C. et al. Irreversible electroporation reverses resistance to immune checkoint blockade in pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun 2019. 10:889.

- Geboers B, Scheltema MJ, Jun J, Baker K, Timmer FEF, Cerutti X, Katelaris A, Doan P, Gondoputro W, Blazevski A, Agrawal S, Matthews J, Haynes AM, Robertson T, Thompson JE, Meijerink MR, Clark SJ, do Gruijl TD, Stricker PD. Irreversible electroporation of localized prostate cancer downregulates immune suppression and induces systemic anti-tumour T-cell activation – IRE-IMMUNO study. BJU Int 2024.

- Campana LG, Daud A, Lancellotti F, Arroyo JP, Davalos RV, Di Prata C, Gehl J. Pulsed Electric Fields in Oncology: A Snapshot of Current Clinical Practices and Research Directions from the 4th World Congress of Electroporation. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Jun 25;15(13):3340. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).