1. Introduction

Malachite green (MG) has been widely used in the aquaculture industry since the 1930s as a fungicide and ectoparasiticide, particularly for treating fish eggs, fingerlings, and adult fish [

1]. It is readily absorbed into fish tissues during waterborne exposure and is rapidly metabolized to its reduced, colorless form—leucomalachite green (LMG) [

2,

3]. Due to its toxicological and potentially carcinogenic properties, the use of MG in aquaculture has been banned in many countries, including the United States and the European Union. Nevertheless, its low cost, high efficacy against fungi, bacteria, and parasites, and easy accessibility have led to continued illegal use in some regions.

In recent decades, concerns regarding the presence of chemical contaminants in aquatic environments have been increasing globally, particularly in countries with intensive agricultural and aquaculture activities. Numerous studies have reported the widespread occurrence of pesticide residues in vegetables [

4], heavy metals in aquatic organisms [

5], and various organic micropollutants in surface and drinking water sources [

6,

7]. Such contaminants not only pose ecological risks but also affect food safety and public health [

3,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Numerous researchers have increasingly focused on chemical monitoring and toxicological risk assessments in aquatic ecosystems, employing advanced techniques such as high-resolution mass spectrometry [

4,

11], multiresidue screening [

6,

9,

10], and metabolomic approaches [

5,

9,

12]. In this context, toxicological studies on MG serve as an essential component of broader environmental surveillance and aquatic toxicology.

Residues of MG in aquaculture products have been frequently reported in the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) notifications of the European Commission. MG and LMG have also been detected in farmed fish imported into the UK, primarily from Southeast Asia [

13,

14,

15]. The misuse of MG not only causes contamination of aquatic environments but also poses serious risks to human health [

16,

17]. Numerous studies have been conducted on the analysis, tissue distribution, accumulation, and elimination of MG and LMG in fish following waterborne exposure. For example, Alderman and Clifton-Hadley [

3] investigated the pharmacokinetics of MG in rainbow trout exposed to a 1.6 mg/L bath for 40 minutes, examining the effect of temperature on MG persistence, although LMG was not considered. Law (1994) studied the metabolism of MG and LMG in fingerling trout exposed to 2 mg/L MG for 1 hour and found that MG levels decreased over time while LMG levels peaked at 24 hours post-exposure and then remained stable for seven days [

18].

Meinertz et al. (1995) measured MG residues in eggs and fry exposed to repeated treatments (1 µg/mL) and found a residue level of 0.271 µg/g on day 31, with a half-life of 9.7 days [

19]. Plakas et al. (1996) examined MG uptake, distribution, and metabolism in channel catfish exposed to 0.8 mg/L MG for 1 hour, reporting half-lives of 4.7 hours in plasma and 2.8 to 10 days in muscle for MG and LMG, respectively [

2]. More recently, Jiang et al. (2009) evaluated MG accumulation in various tissues (muscle, gill, liver, kidney, blood, skin, and gonad) of three freshwater fish species in China. After an acute 6 mg/L MG exposure for 20 minutes, gill tissues exhibited the highest MG levels at 0 hours, followed by a rapid decline of both MG and LMG in blood. However, residues in muscle remained above 0.002 µg/g at 240 hours post-exposure, and LMG persisted particularly in fat-rich tissues such as skin and gonads. Notably, the distribution of LMG was more influenced by tissue fat content than by feeding behavior [

20].

These findings provide a foundation for understanding the organ-specific dynamics of MG absorption and elimination in fish. Building upon this knowledge, our study focuses on the temporal accumulation and elimination of MG and LMG in Oreochromis mossambicus (tilapia), a species known for its hardiness, adaptability, and widespread use in aquaculture in Vietnam. Tilapia is also included in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s standard method for the quantification of MG and LMG residues in fish and shrimp (FDA Method 4363), making it a relevant model organism for this investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

All solvents used were of LC-MS grade, and all other chemicals were of analytical reagent grade unless otherwise specified. Malachite green (MG) and leucomalachite green (LMG) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Standard stock solutions (1 mg/mL) of MG and LMG were prepared in acetonitrile and stored at 4°C; they remained stable for at least one month.

Formic acid (99.5%), acetonitrile, methanol, and dichloromethane were obtained from J.T. Baker. Certified alumina-based solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges (500 mg, 6 mL) were obtained from Sep-Pak Waters (USA). Sodium chloride was purchased from Merck and pre-heated at 700°C for 6 hours prior to use.

Ultrapure water was generated using a Milli-Q Gradient A10 purification system (USA). A 0.1 M acetate buffer at pH 4.5 was prepared freshly before use. A 25% hydroxylamine hydrochloride (HAH) solution was prepared by dissolving 25.0 g of hydroxylamine hydrochloride in 100 mL of ultrapure water. A 0.05 M p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TSA) solution was prepared by dissolving 0.95 g of p-TSA in 100 mL of ultrapure water.

2.2. Animal Experiments

The experimental fish, Oreochromis mossambicus (Tilapia), were obtained from an aquaculture pond with no prior history of malachite green (MG) treatment. MG residues in the fish were analyzed before the experiment using 6 to 8 replicates, and no MG residues were detected. The average body weight of the fish was approximately 100 ± 5 g. Fish were acclimated for 7 days in aquariums containing dechlorinated tap water, equipped with aeration and filtration systems. During acclimation, water was changed daily. The mean water quality parameters during the experiment were as follows: dissolved oxygen ≥ 4 mg/L; pH 6.5–8.5; temperature 20–23°C; and no detectable free chlorine.

MG was dissolved in a 70-L aquarium containing 30 fish, achieving a concentration of 100 ppb. The aquarium water was completely changed every 24 hours, and MG was re-added to maintain the 100 ppb concentration throughout 10 consecutive experimental days. The aquarium was continuously aerated and filtered. Fish samples were collected every 24 hours. Muscle, gill, and liver tissues were excised and stored at −20°C for subsequent MG and leucomalachite green (LMG) analysis. Three fish were sampled at each time point. Reported values represent the average concentrations of MG and LMG in the three tissue types.

In this experiment, MG was added once at the start to reach a concentration of 1000 ppb in the aquarium, which was maintained for 7 days without any water changes or further MG additions. Fish sampling and tissue analysis were conducted as described in Experiment 1.

2.3. Analytical Procedures

2.3.1. Sample Preparation

Based on methods reported in references [

3,

4,

5,

9], we developed a sample extraction procedure for malachite green (MG) and leucomalachite green (LMG) in fish tissues. Approximately 2 ± 0.05 g of tissue sample was weighed into 50 mL centrifuge tubes. To each tube, 0.5 mL of 25% hydroxylamine hydrochloride (HAH), 0.5 mL of 0.05 M p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TSA) solution, and 1 mL of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5) were added. The sample was homogenized at 1600 rpm for 3 minutes. Subsequently, 10 mL of acetonitrile was added, and homogenization was repeated. The mixture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. The homogenization and centrifugation steps with 10 mL acetonitrile were repeated once more.

To the combined supernatant, 10 mL dichloromethane and 1.5 g sodium chloride were added. The sample was vortex-mixed thoroughly and centrifuged. The organic phase was then evaporated to dryness. The residue was reconstituted in 3 mL of formic acid/acetonitrile (2:98, v/v) and passed through a preconditioned alumina SPE cartridge (6 mL acetonitrile). The eluate was collected and evaporated to dryness again. Finally, the analyte fraction was dissolved in 1 mL acetonitrile and used for LC-MS analysis of MG and LMG.

2.3.2. Liquid Chromatography Equipment and Conditions

Qualitative and quantitative analyses of MG and LMG were performed using a Shimadzu LCMS 2010A single quadrupole mass spectrometer (Japan) equipped with an autosampler, a Surveyor LC pump, a Surveyor PDA detector, and an ion trap mass analyzer with an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) source operated in positive ion mode (APCI+).

Separation was achieved on an Agilent ZORBAX SB-C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 3.5 μm particle size; Agilent Technologies, USA). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (water with 0.05% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.05% formic acid). The linear gradient program was as follows: 0 min, 5% B; 0.5 min, 40% B; 3 min, 60% B; 4 min, 80% B; 6 min, 80% B; 10 min, 5% B; maintained until 20 min. The flow rate was set at 0.3 mL/min. Column temperature was maintained at 35°C, and the injection volume was 5 μL.

Mass spectrometry tuning was performed using MG and LMG ions at m/z 329 and 331, respectively. Quantification was carried out in Selective Ion Monitoring (SIM) mode. The ionization interface voltage was set at +5000 V, and the interface temperature was maintained at 250°C.

2.3.3. Recovery Experiments

To assess the accuracy of the analytical method, recovery experiments were performed in triplicate by spiking homogenized muscle samples (2 ± 0.05 g) with a mixed MG and LMG standard solution to achieve a final concentration of 100 ppb in the tissue. Recovery percentages were calculated based on measured versus spiked amounts. The average recoveries (n=4) were 62.3 ± 0.7% for MG and 91.5 ± 0.5% for LMG.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Experiment 1: Constant MG Concentration with Daily Water Changes

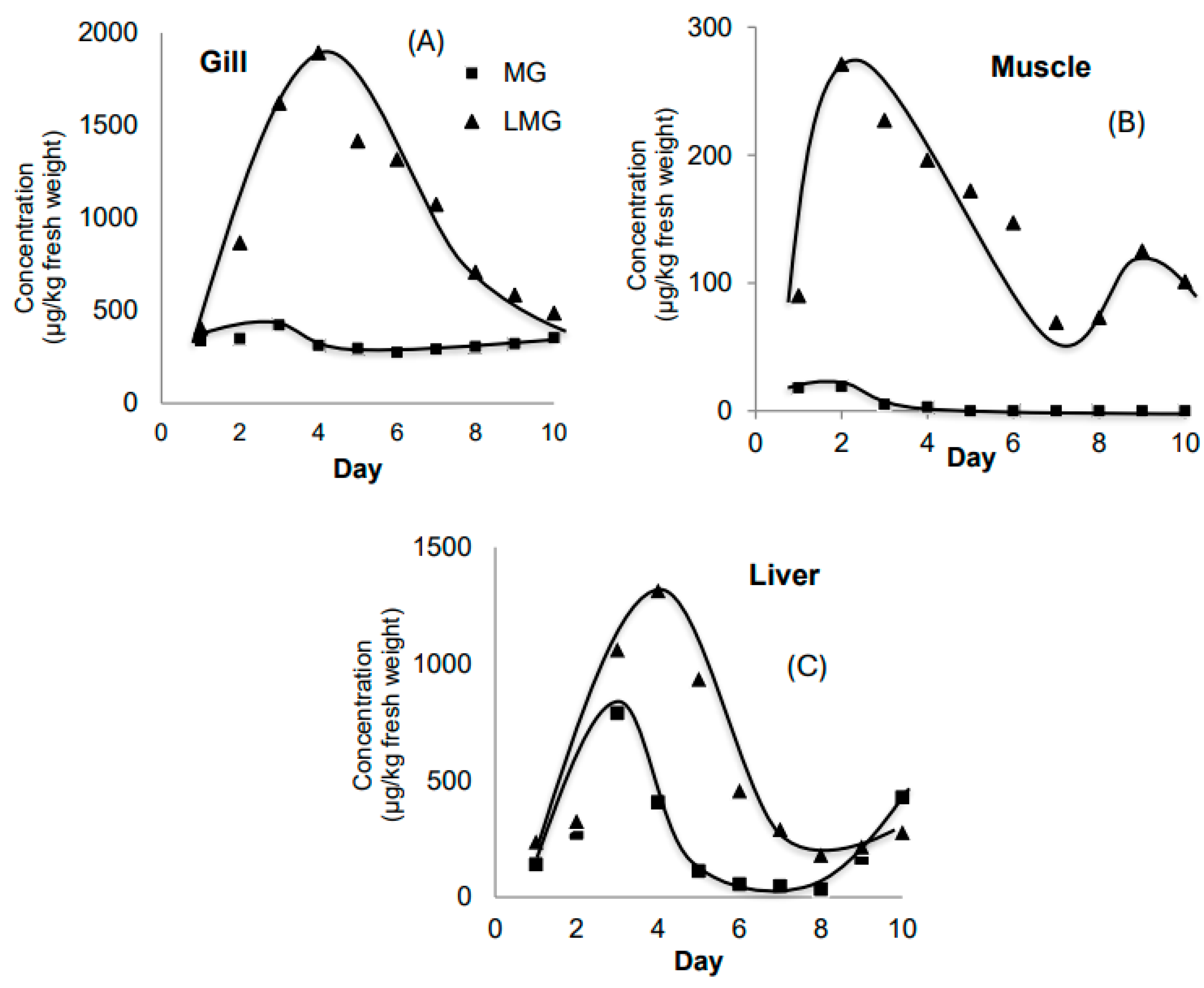

The results (

Figure 1A) showed that the gills accumulated leucomalachite green (LMG) at levels approximately 2.23 times higher than malachite green (MG). Peak accumulation of MG was observed on day 3 (423 µg/kg), while LMG reached its maximum on day 4 (1893 µg/kg). However, LMG levels began to decline after day 4, whereas MG levels also initially decreased but showed a slight increase from day 6 onwards. Overall, the total concentrations of MG and LMG in the gills tended to decrease after day 6. This trend may reflect the physiological regulation in fish, such as reduced uptake or enhanced excretion of toxicants.

The gill, as a major respiratory organ, functions primarily in gas exchange rather than metabolic transformation. It acts as a natural barrier or filter but does not play a significant role in the conversion of MG to LMG. Therefore, LMG observed in the gill likely results from direct environmental exposure or systemic circulation, rather than in situ metabolism.

In this experiment, MG was added daily to maintain its concentration in water. Despite this, MG levels in muscle tissue remained very low during the first four days (18, 19, 5, and 3 µg/kg, respectively) and became undetectable from day 5 onwards (

Figure 1B). This suggests that MG does not easily penetrate fish muscle through direct environmental exposure, and its accumulation in muscle may primarily occur via systemic absorption through the digestive tract and liver metabolism. The decreasing LMG levels in muscle over time could indicate adaptation of fish to long-term MG exposure, reducing further penetration or enhancing elimination.

The liver plays a central role in detoxification and metabolism.

Figure 1C shows that the liver accumulated the highest total concentration of MG and LMG on day 3 (1951 µg/kg), followed by a gradual decrease. The proportion of LMG in total residues in the liver remained relatively constant (~60%) during the first three days and peaked at 76.4% on day 4. Although overall residue levels declined thereafter, the proportion of LMG relative to MG increased markedly, reaching 89% on day 6. This suggests that the liver not only accumulates LMG but also actively metabolizes MG into LMG.

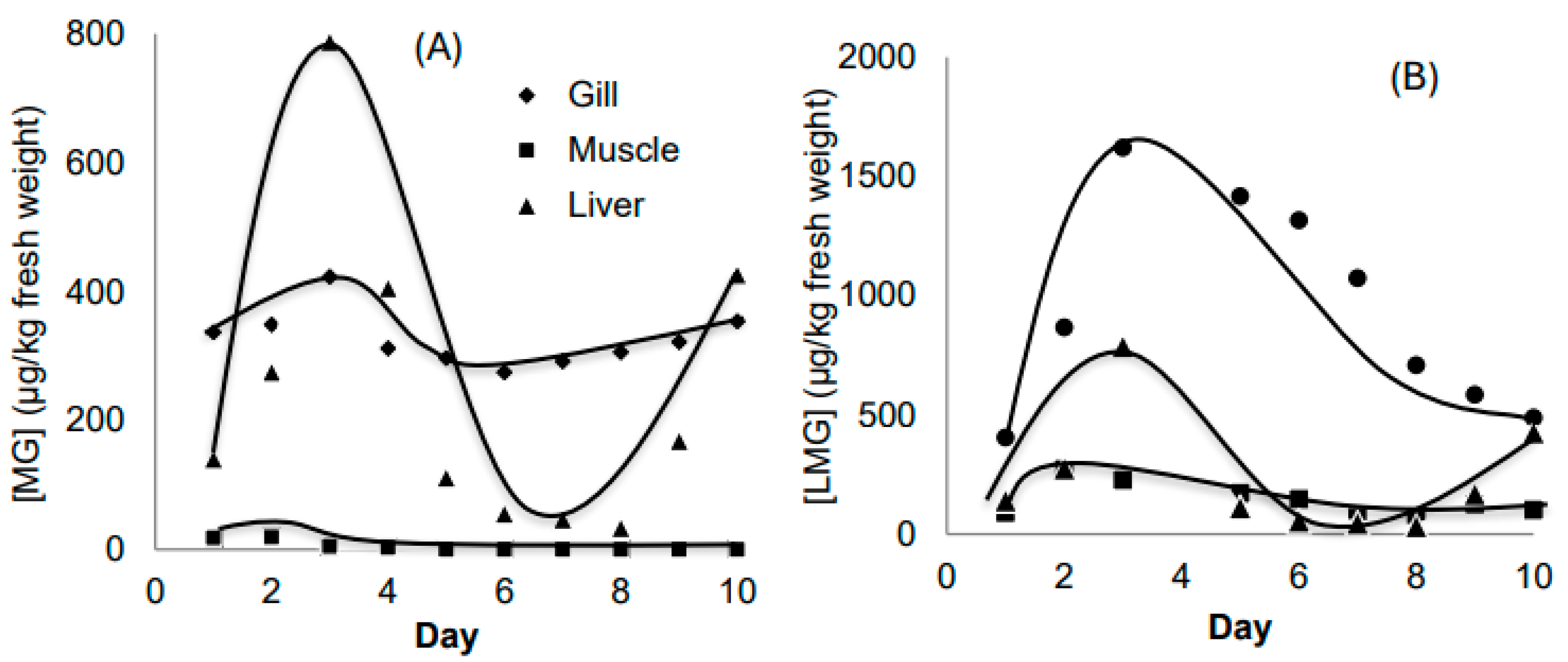

Data from

Figure 2 confirm that the highest total accumulation of MG and LMG occurred in the gills, approximately 2.5 times higher than the liver and 12 times higher than the muscle. Comparing liver and muscle, LMG concentrations in muscle were about half those in the liver, supporting the liver’s critical role in both the formation and elimination of LMG. Among the three organs, the liver had the highest LMG concentrations, confirming its key metabolic function. In contrast, the gill acts more as a direct exposure site, serving as a passive barrier rather than an active metabolic organ.

3.2. Experiment 2: Single MG Exposure Without Daily Water Changes

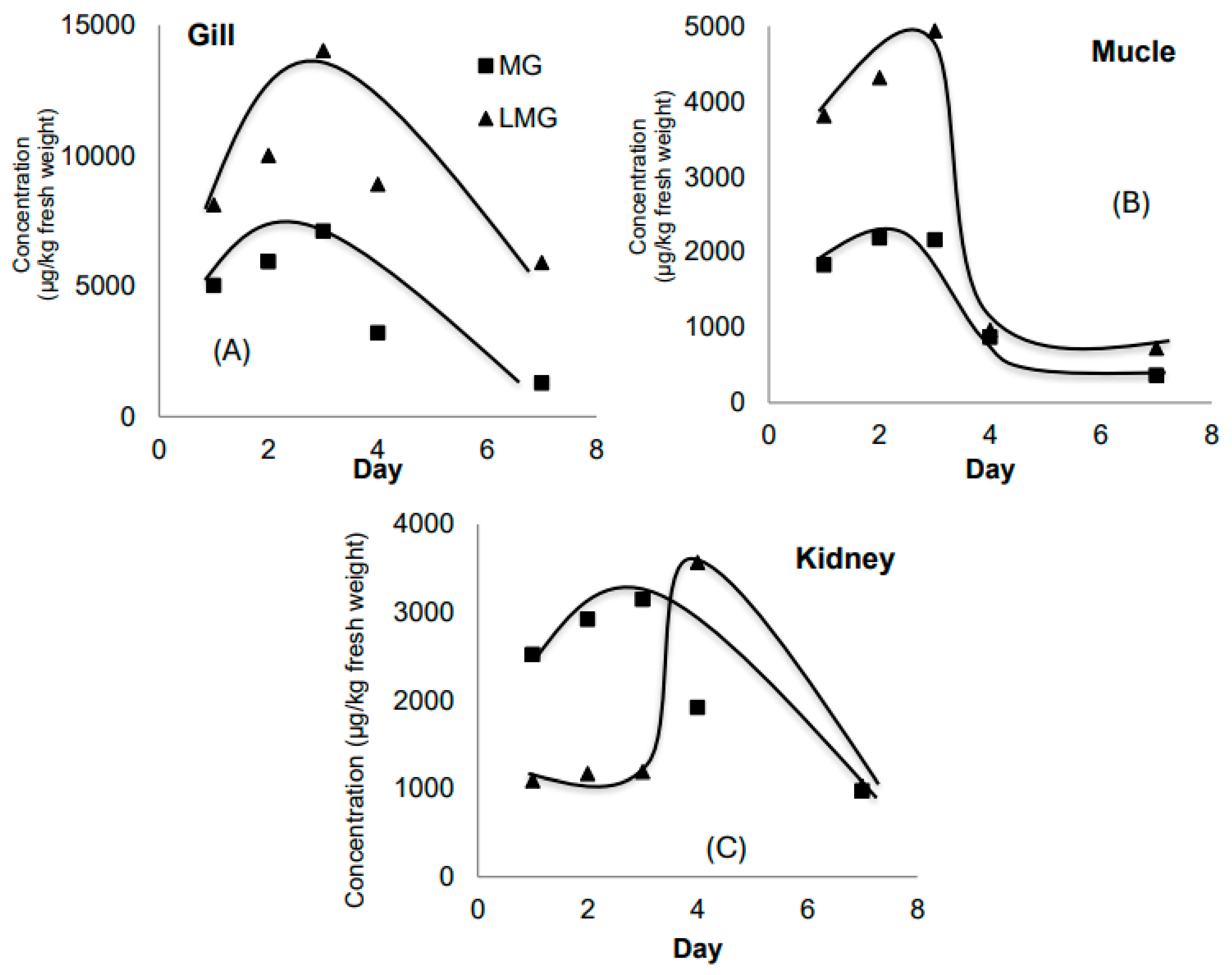

In this experiment, MG was introduced only once at the beginning (day 0) at a concentration of 1000 ppb. As shown in

Figure 3A, the liver accumulated LMG at concentrations approximately 2.5 times higher than MG. Both MG and LMG levels peaked on day 4 and declined thereafter. The maximum MG concentration was observed on day 3 (7107 µg/kg), dropping to 1287 µg/kg by day 7 — a 7-fold decrease. For LMG, concentrations decreased from a peak of 14,923 µg/kg on day 3 to 5907 µg/kg on day 7 — a 3-fold decrease.

Since MG was not replenished daily in this setup, its concentration in the water likely declined over time due to degradation, metabolism, or sorption. MG and LMG concentrations in muscle (

Figure 3B) showed an increasing trend over the first three days, followed by a decline — a trend similar to that observed in the gills. This suggests that systemic exposure and accumulation patterns were consistent across tissues during early exposure.

Figure 3C shows that in the liver, MG peaked on day 3 (3147 µg/kg), while LMG levels remained relatively stable during the first three days and then rose sharply to 3569 µg/kg on day 4. The more pronounced change in LMG concentration compared to MG reflects the liver’s role as a metabolic organ, capable of transforming MG and eliminating toxicants.

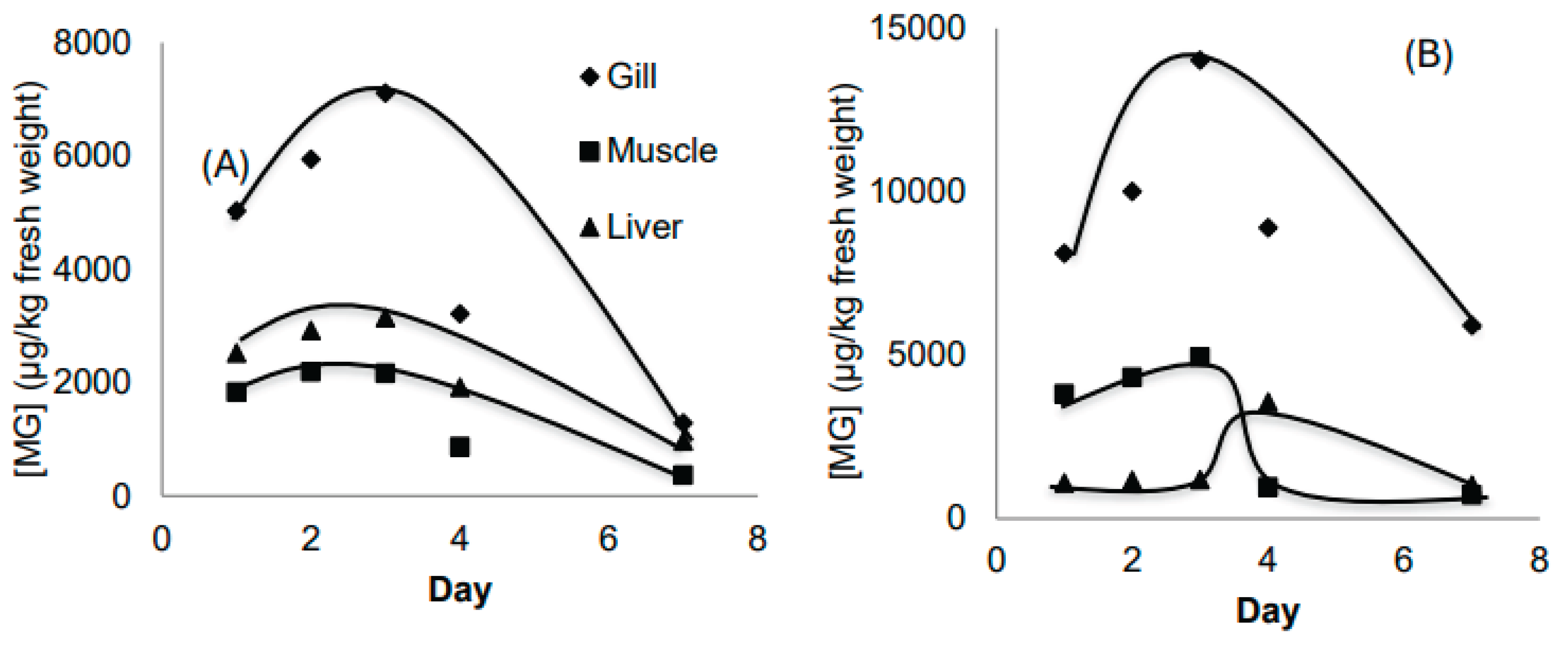

Figure 4A and

Figure 4B compare MG and LMG concentrations across all three tissues. Both MG and LMG levels were consistently lowest in muscle and highest in the gills. The MG accumulation trends were similar across all organs, indicating that fish may not have been able to adapt immediately to the high MG concentration (1000 ppb) during the early exposure phase. However, over time, fish appeared to adapt by enhancing elimination or transforming MG into other metabolites. In contrast, LMG accumulation trends varied by organ, particularly in the liver, likely due to its metabolic and excretory functions.

4. Discussions

The present study provides a detailed investigation of the accumulation dynamics and metabolic transformation of malachite green (MG) and its reduced form leucomalachite green (LMG) in tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) under two exposure scenarios. The findings revealed tissue-specific differences in accumulation patterns, with the gills exhibiting the highest concentrations of both MG and LMG, followed by the liver and then the muscle. This pattern highlights the significance of the gill as the primary site of entry for waterborne toxicants and as a passive filter rather than a metabolic organ.

In both experimental setups, the transformation of MG into LMG was clearly observed, especially in the liver, confirming its role as the main site for biotransformation. The increasing proportion of LMG over time suggests a consistent metabolic conversion and a possible accumulation of the more persistent metabolite. Notably, the results indicated that repeated low-dose exposure (Experiment 1) allowed fish to gradually adapt and enhance detoxification mechanisms more effectively than a single high-dose exposure (Experiment 2). This observation supports the idea that acclimation and metabolic regulation play critical roles in toxicant management in aquatic organisms [

21].

The differential accumulation among tissues also aligns with previous toxicological studies showing that metabolic and excretory capabilities of fish are strongly organ-specific. For instance, in a study on acrylamide contamination in daily food in urban Hanoi, the bioaccumulation potential of certain substances was closely linked to metabolic activity in different food matrices [

22]. Similarly, bioaccumulation of pollutants in aquatic ecosystems has been well documented in Vietnamese rivers, where organic micropollutants and trace metals were found to concentrate in organisms depending on exposure duration and pathways [

23,

24].

The gill, despite its high absorption rate, demonstrated a reduced metabolic capacity compared to the liver, as reflected by the lower proportion of LMG. This is consistent with the role of the gill as an interface organ for gas exchange and its limited involvement in enzymatic detoxification. The muscle, representing the edible part of fish, showed the lowest accumulation, suggesting a degree of protection afforded by hepatic and branchial metabolism. However, even trace levels in muscle can be concerning for food safety, particularly in regions like the Red River Delta, where aquaculture is often conducted near sources of industrial and agricultural runoff [

25,

26].

Importantly, the adaptation capacity of fish observed in the repeated low-concentration exposure experiment reflects broader biological resilience mechanisms, which are also observed in plants exposed to contaminants in Vietnam. For example, studies on

Pteris vittata and

Pityrogramma calomelanos showed differential arsenic uptake and tolerance depending on soil pH and exposure conditions [

27], which parallels the variable detoxification capacity in fish across tissues and over time.

Furthermore, the findings have implications for environmental health in polluted areas of Vietnam, where a wide array of natural and anthropogenic contaminants—including secondary metabolites [

28,

29,

30], emissions from livestock farming [

25,

31], and ozone-inducing fuels [

32]—interact and potentially exacerbate toxicity. The ability of aquatic species to metabolize and excrete such substances determines not only their survival but also the safety of aquaculture products destined for human consumption.

As chemical and biological complexity in aquatic systems increases due to urbanization and climate change, toxicological evaluations like this study are essential. They complement ongoing research efforts on pollutant screening [

23], chemical constituent characterization [

28,

33], and adaptation mechanisms in both aquatic and terrestrial organisms [

21,

34,

35]. Collectively, such studies contribute to a more holistic understanding of environmental risks and the development of safer aquaculture practices.

5. Conclusions

This study provided an initial evaluation of malachite green (MG) and leucomalachite green (LMG) accumulation in tilapia under controlled laboratory conditions. As one of the early investigations on MG toxicity in this species, the findings contribute to a better understanding of toxicokinetics and tissue distribution in aquatic organisms.

MG and LMG were found to accumulate in all three major exposure routes: through the gills (respiratory), liver (digestive), and skin/muscle (dermal). Among these, the gills exhibited the highest levels of accumulation, while muscle tissues showed the lowest concentrations. This distribution suggests that gills serve as the primary entry point for MG, whereas the muscle may reflect longer-term, systemic exposure or residual retention.

Physiological effects observed in exposed fish included softened muscle texture, faded coloration, and the appearance of red spots in the gills, indicating potential tissue damage and systemic stress caused by MG and LMG.

The results also highlight the adaptive capacity of tilapia to toxic exposure. Fish exposed to lower, consistent concentrations of MG over time demonstrated improved detoxification and elimination capabilities compared to those subjected to high, sustained concentrations. These findings suggest that gradual, sublethal exposure may allow fish to activate physiological defense mechanisms more effectively, leading to enhanced resilience against environmental toxicants.

References

- Alderman, D. J. (1985). Malachite green: a review. Journal of Fish Diseases, 8(3), 289–298. [CrossRef]

- Plakas, S.M., El Said, K.R., Stehly, G.R., Gingerich, W.H., Allen, J.L. (1996) Uptake, tissue distribution and metabolism of malachite green in the channel catfish (Ictarulus punctatus). Can. J. Fish Aquat. Sci. 53, 1427–1433. [CrossRef]

- Alderman, D.J., Clifton-Hadley, R.S. (1993) Malachite green: a pharmacokinetic study in rainbow trout. J. Fish Dis. 16, 296–311.

- Vu-Duc, N., Nguyen-Quang, T., Le-Minh, T., Nguyen-Thi, X., Tran, T. M., Vu, H. A., Nguyen, L.-A., Doan-Duy, T., Van Hoi, B., Vu, C.-T., Le-Van, D., Phung-Thi, L.-A., Vu-Thi, H.-A., & Chu, D. B. (2019). Multiresidue Pesticides Analysis of Vegetables in Vietnam by Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography in Combination with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-Orbitrap MS). Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry, 2019, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Dang, T. T., Vo, T. A., Duong, M. T., Pham, T. M., Van Nguyen, Q., Nguyen, T. Q., Bui, M. Q., Syrbu, N. N., & Van Do, M. (2022). Heavy metals in cultured oysters (Saccostrea glomerata) and clams (Meretrix lyrata) from the northern coastal area of Vietnam. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 184, 114140. [CrossRef]

- Nu Nguyen, H. M., Khieu, H. T., Ta, N. A., Le, H. Q., Nguyen, T. Q., Do, T. Q., Hoang, A. Q., Kannan, K., & Tran, T. M. (2021). Distribution of cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes in drinking water, tap water, surface water, and wastewater in Hanoi, Vietnam. Environmental Pollution, 285, 117260. [CrossRef]

- Quang, T. H., Phong, N. V., Anh, L. N., Hanh, T. T. H., Cuong, N. X., Ngan, N. T. T., Trung, N. Q., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2020). Secondary metabolites from a peanut-associated fungus Aspergillus niger IMBC-NMTP01 with cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities. Natural Product Research, 36(5), 1215–1223. [CrossRef]

- Le, T. M., Pham, P. T., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, T. Q., Bui, M. Q., Nguyen, H. Q., Vu, N. D., Kannan, K., & Tran, T. M. (2022). A survey of parabens in aquatic environments in Hanoi, Vietnam and its implications for human exposure and ecological risk. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(31), 46767–46777. [CrossRef]

- Truong, D. A., Trinh, H. T., Le, G. T., Phan, T. Q., Duong, H. T., Tran, T. T. L., Nguyen, T. Q., Hoang, M. T. T., & Nguyen, T. V. (2023). Occurrence and ecological risk assessment of organophosphate esters in surface water from rivers and lakes in urban Hanoi, Vietnam. Chemosphere, 331, 138805. [CrossRef]

- Le, V. N., Nguyen, Q. T., Nguyen, T. D., Nguyen, N. T., Janda, T., Szalai, G., & Le, T. G. (2020). The potential health risks and environmental pollution associated with the application of plant growth regulators in vegetable production in several suburban areas of Hanoi, Vietnam. Biologia Futura, 71(3), 323–331. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M. T. T., Le, G. T., Kiwao, K., Duong, H. T., Nguyen, T. Q., Phan, T. Q., Bui, M. Q., Truong, D. A., & Trinh, H. T. (2023). Occurrence and risk of human exposure to organophosphate flame retardants in indoor air and dust in Hanoi, Vietnam. Chemosphere, 328, 138597. [CrossRef]

- Quang, T. H., Phong, N. V., Anh, D. V., Hanh, T. T. H., Cuong, N. X., Ngan, N. T. T., Trung, N. Q., Oh, H., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2021). Bioactive secondary metabolites from a soybean-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor IMBC-NMTP02. Phytochemistry Letters, 45, 93–99. [CrossRef]

- Aldert A. Bergwerff, Peter Scherpenisse (2003) Determination of residues of malachite green in aquatic animals. Journal of Chromatography B, 788, 351-359.

- Hanwen Sun, Lixin Wang, Xiaolan Qin, Xusheng Ge (2001) Simultaneous determination of malachite green, enrofloxacin anf ciprofloxacin in fish farming water and fish feed by liquid chromatography with solid-phase extraction. Environ Monit Assess, 179, 421-429.

- Kamila Mitrowsak, Andrzej Posyniak, Jan Zmudzki (2004) Determination of malachite green in water using liquid chromatography with visible and fluorescence detection and confirmation by tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 1207, 94-100.

- Shivaji Srivastava, Ranjana Sinha, D. Roy (2004) Toxicological effects of malachite green. Aquatic Toxicology, 66, 319-329.

- Veterinary Residues Committee (2004) Annual Report on Surveillance for Veterinary Residues in Food in the UK, pp. 1–60.

- Law, F.C.P. (1994) Total residue depletion and metabolic profile of selected drugs in trout. US Food and Drug Administration Contract No. 223-90-7016. Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC. Canada.

- Meinertz, J. R., Stehly, G. R., Gingerich, W. H. & Allen, J. L. Residues of [14C]-malachite green in eggs and fry of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), after treatment of eggs. J. Fish. Dis. 18, 239–247 (1995).

- Yan Jiang, Ping Xie, Gaodao Liang (2009) Distribution and depuration of the potentially carcinogenic malachite green in tissues of three freshwater farmed Chinese fish with different food habits. [CrossRef]

- Darkó, E., Khalil, R., Elsayed, N., Pál, M., Hamow, K. A., Szalai, G., Tajti, J., Nguyen, Q. T., Nguyen, N. T., Le, V. N., & Janda, T. (2019). Factors playing role in heat acclimation processes in barley and oat plants. Photosynthetica, 57(4), 1035–1043. [CrossRef]

- Hai, Y. D., Tran-Lam, T.-T., Nguyen, T. Q., Vu, N. D., Ma, K. H., & Le, G. T. (2019). Acrylamide in daily food in the metropolitan area of Hanoi, Vietnam. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, 12(3), 159–166. [CrossRef]

- D.T. Hanh, K. Kadomami, N. Matsuura, N.Q. Trung, Screening analysis of a thousand micro-pollutants in vietnamese rivers, In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Southeast Asian Water Environment (2012), Hanoi, Vietnam, 8.-10. November, 2012.

- Trinh, H. T., Marcussen, H., Hansen, H. C. B., Le, G. T., Duong, H. T., Ta, N. T., Nguyen, T. Q., Hansen, S., & Strobel, B. W. (2017). Screening of inorganic and organic contaminants in floodwater in paddy fields of Hue and Thanh Hoa in Vietnam. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24(8), 7348–7358. [CrossRef]

- Truong, A. H., Kim, M. T., Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, N. T., & Nguyen, Q. T. (2018). Methane, Nitrous Oxide and Ammonia Emissions from Livestock Farming in the Red River Delta, Vietnam: An Inventory and Projection for 2000–2030. Sustainability, 10(10), 3826. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. X., Nguyen, X. T., Mai, H. T. H., Nguyen, H. T., Vu, N. D., Pham, T. T. P., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, D. T., Duong, N. T., Hoang, A. L. T., Nguyen, T. N., Le, N. V., Dao, H. V., Ngoc, M. T., & Bui, M. Q. (2024). A Comprehensive Evaluation of Dioxins and Furans Occurrence in River Sediments from a Secondary Steel Recycling Craft Village in Northern Vietnam. Molecules, 29(8), 1788. [CrossRef]

- Anh, B. T. K., Minh, N. N., Ha, N. T. H., Kim, D. D., Kien, N. T., Trung, N. Q., Cuong, T. T., & Danh, L. T. (2018). Field Survey and Comparative Study of Pteris Vittata and Pityrogramma Calomelanos Grown on Arsenic Contaminated Lands with Different Soil pH. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 100(5), 720–726. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Hang, L. T. T., Huong Giang, V., Trung, N. Q., Thanh, N. V., Quang, T. H., & Cuong, N. X. (2021). Chemical constituents of Blumea balsamifera. Phytochemistry Letters, 43, 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Cham, P. T., Anh, D. H., Cuong, N. T., Trung, N. Q., Quang, T. H., Cuong, N. X., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2021). Dammarane-type triterpenoid saponins from the flower buds of Panax pseudoginseng with cytotoxic activity. Natural Product Research, 36(17), 4343–4351. [CrossRef]

- Van, Pc. P., Ngo Van, H., Quang, M. B., Duong Thanh, N., Nguyen Van, D., Thanh, T. D., Tran Minh, N., Thi Thu, H. N., Quang, T. N., Thao Do, T., Thanh, L. P., Do Thi Thu, H., & Le Tuan, A. H. (2023). Stigmastane-type steroid saponins from the leaves of Vernonia amygdalina and their α -glucosidase and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities. Natural Product Research, 38(4), 601–606. [CrossRef]

- Markus Amann, Zbigniew Klimont, T An Ha, Peter Rafaj, Gregor Kiesewetter, Adriana Gomez Sanabria, Binh Nguyen, TN Thi Thu, Kimminh Thuy, Wolfgang Schöpp, Jens Borken-Kleefeld, L Höglund-Isaksson, Fabian Wagner, Robert Sander, Chris Heyes, Janusz Cofala, Nguyen Quang Trung, Nguyen Tien Dat, Nguyen Ngoc Tung, Future Air Quality in Ha Noi and Northern Vietnam. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/15803(2019).

- Thang, P. Q., Muto, Y., Maeda, Y., Trung, N. Q., Itano, Y., & Takenaka, N. (2016). Increase in ozone due to the use of biodiesel fuel rather than diesel fuel. Environmental Pollution, 216, 400–407. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Anh, D. H., Huong, P. T. T., Thanh, N. V., Trung, N. Q., Cuong, T. V., Mai, N. T., Cuong, N. T., Cuong, N. X., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2018). Crinane, augustamine, and β -carboline alkaloids from Crinum latifolium. Phytochemistry Letters, 24, 27–30. [CrossRef]

- Duong, T. T., Nguyen, T. T. L., Dinh, T. H. V., Hoang, T. Q., Vu, T. N., Doan, T. O., Dang, T. M. A., Le, T. P. Q., Tran, D. T., Le, V. N., Nguyen, Q. T., Le, P. T., Nguyen, T. K., Pham, T. D., & Bui, H. M. (2021). Auxin production of the filamentous cyanobacterial Planktothricoides strain isolated from a polluted river in Vietnam. Chemosphere, 284, 131242. [CrossRef]

- Minh, T. N., Minh, B. Q., Duc, T. H. M., Thinh, P. V., Anh, L. V., Dat, N. T., Nhan, L. V., & Trung, N. Q. (2022). Potential Use of Moringa oleifera Twigs Extracts as an Anti-Hyperuricemic and Anti-Microbial Source. Processes, 10(3), 563. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).