Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

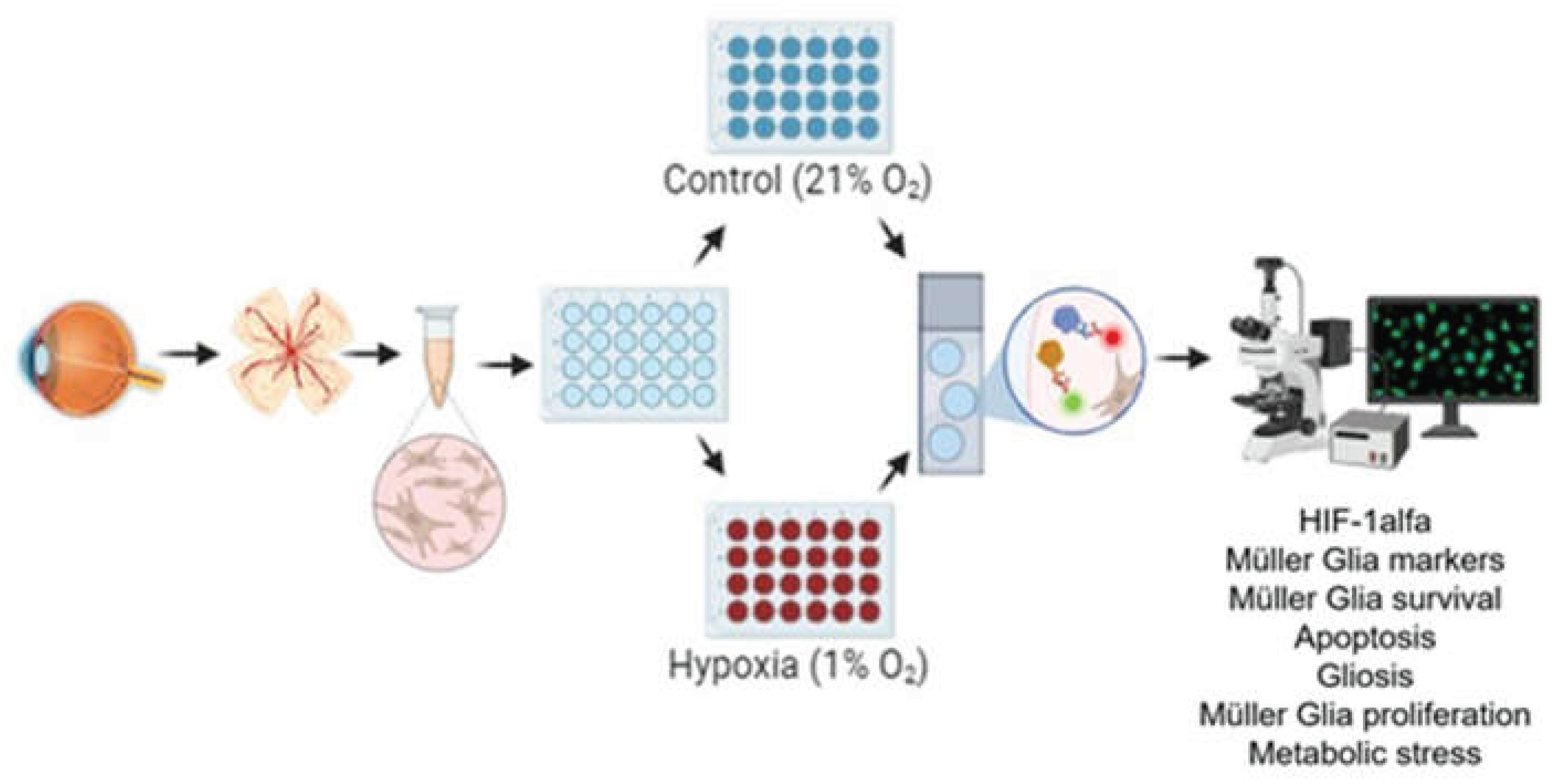

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Retina Extraction and Primary Müller Glia Cultures

2.2. Immunocytochemical Analysis and Image Capture

2.3. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

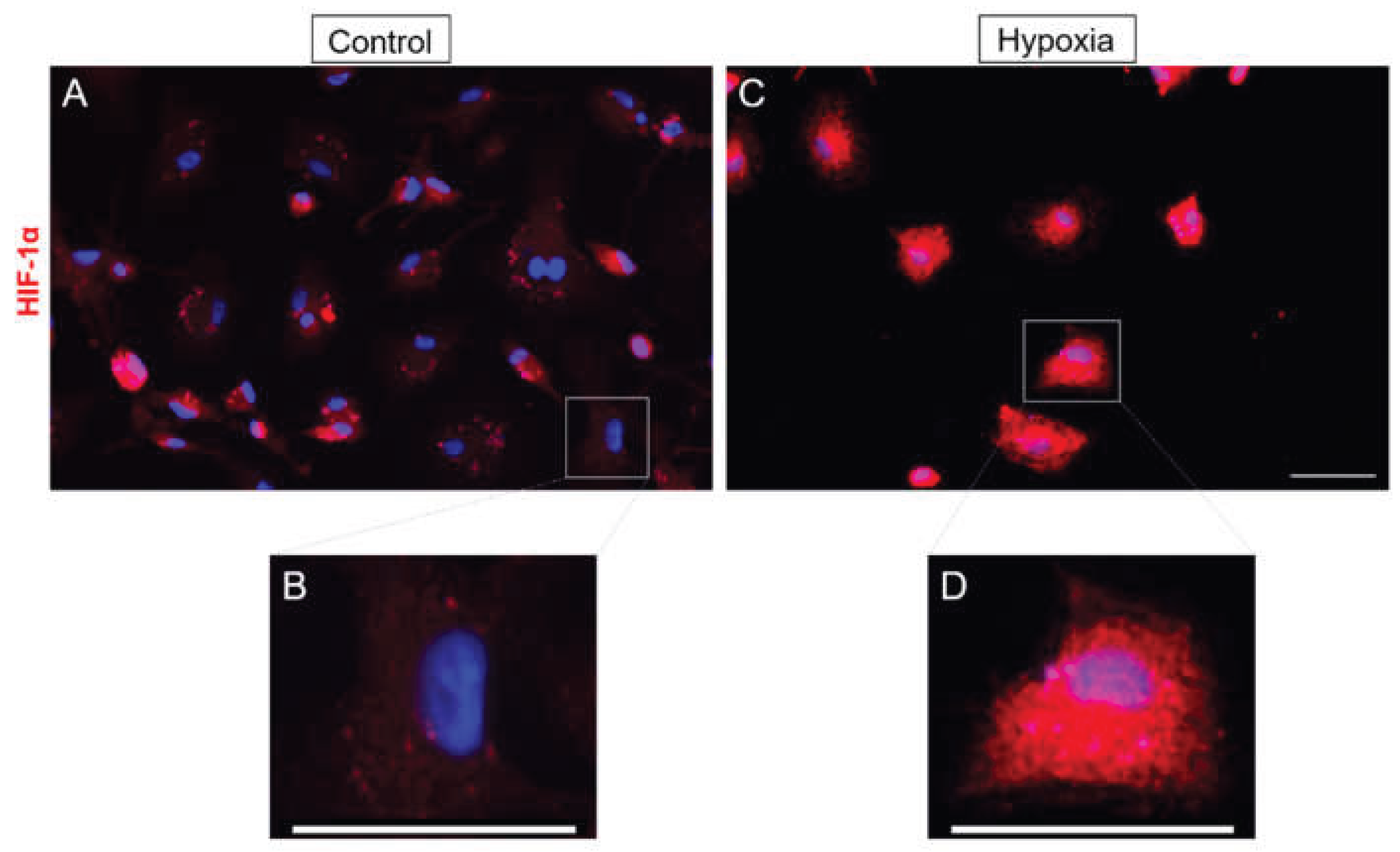

3.1. Expression of HIF-1α

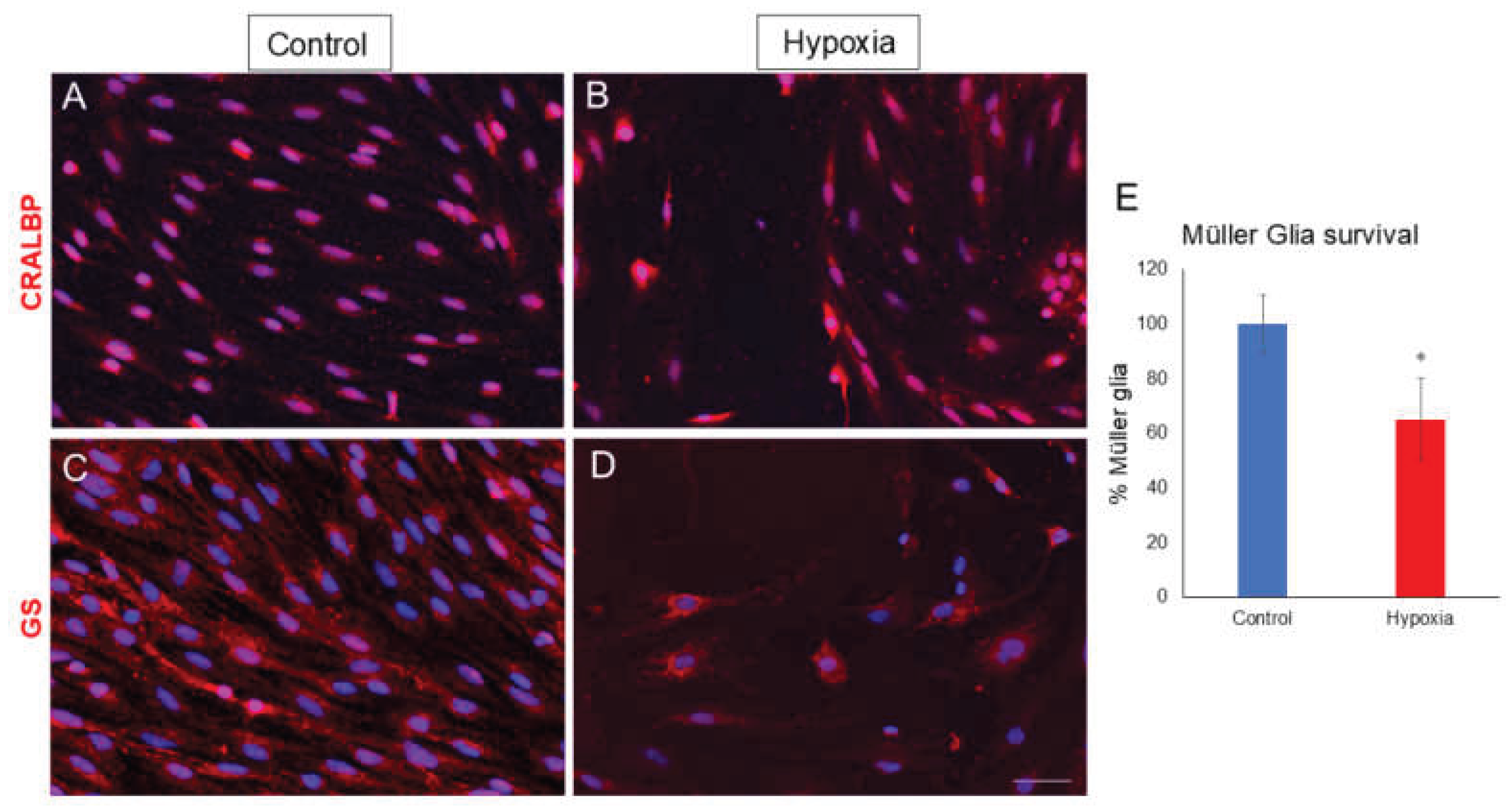

3.2. MG Markers and Cell Survival Assay

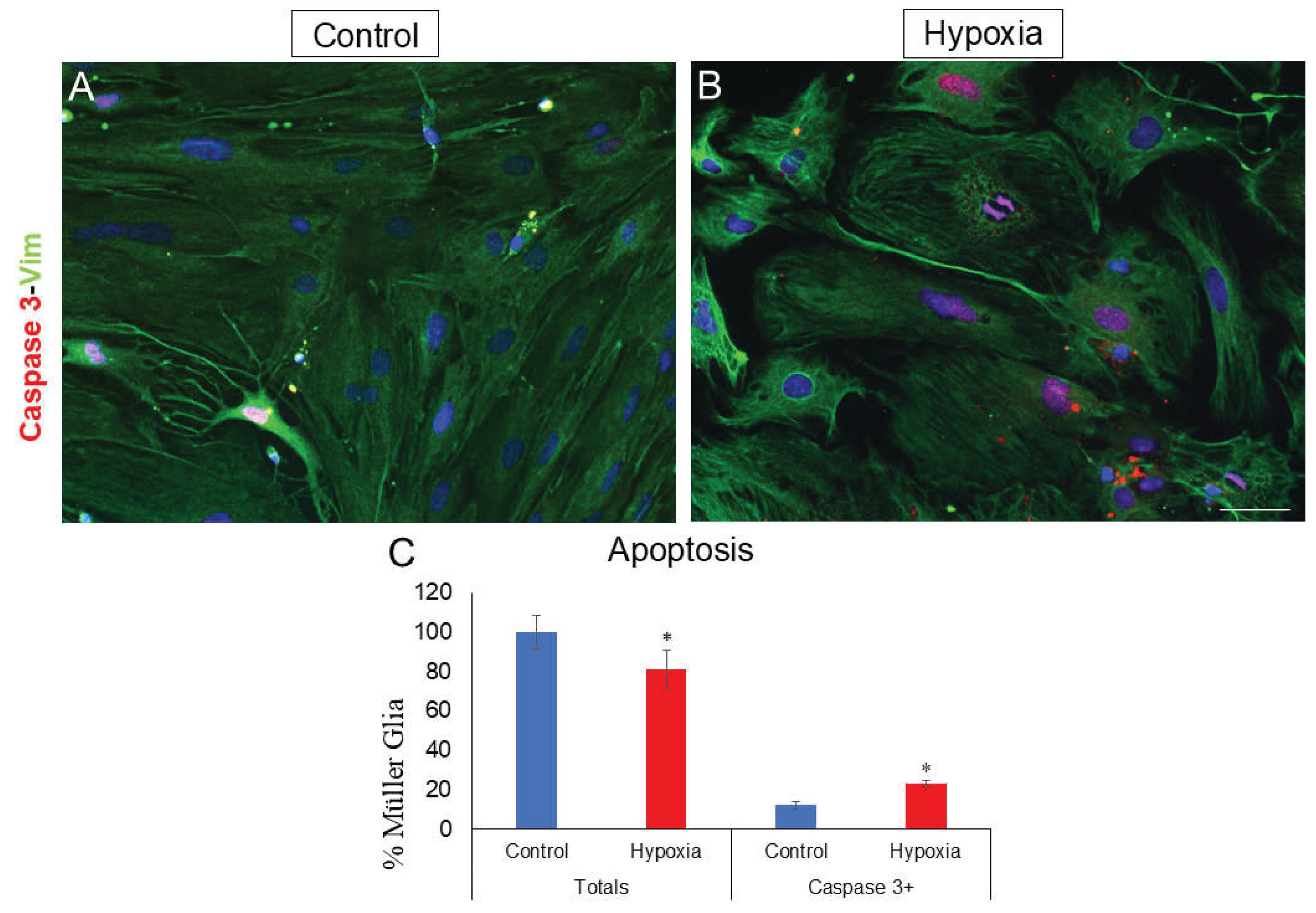

3.3. Hypoxia Mediated Apoptosis

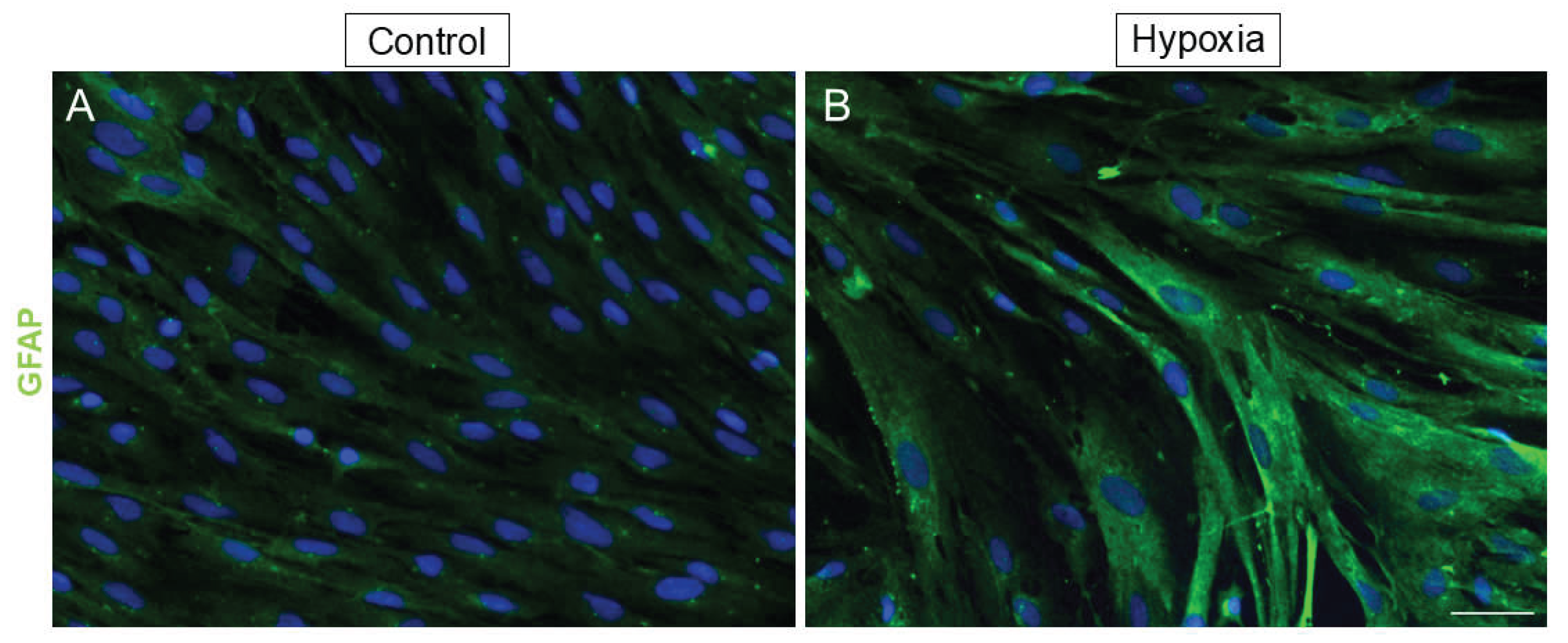

3.4. Gliosis by GFAP Expression

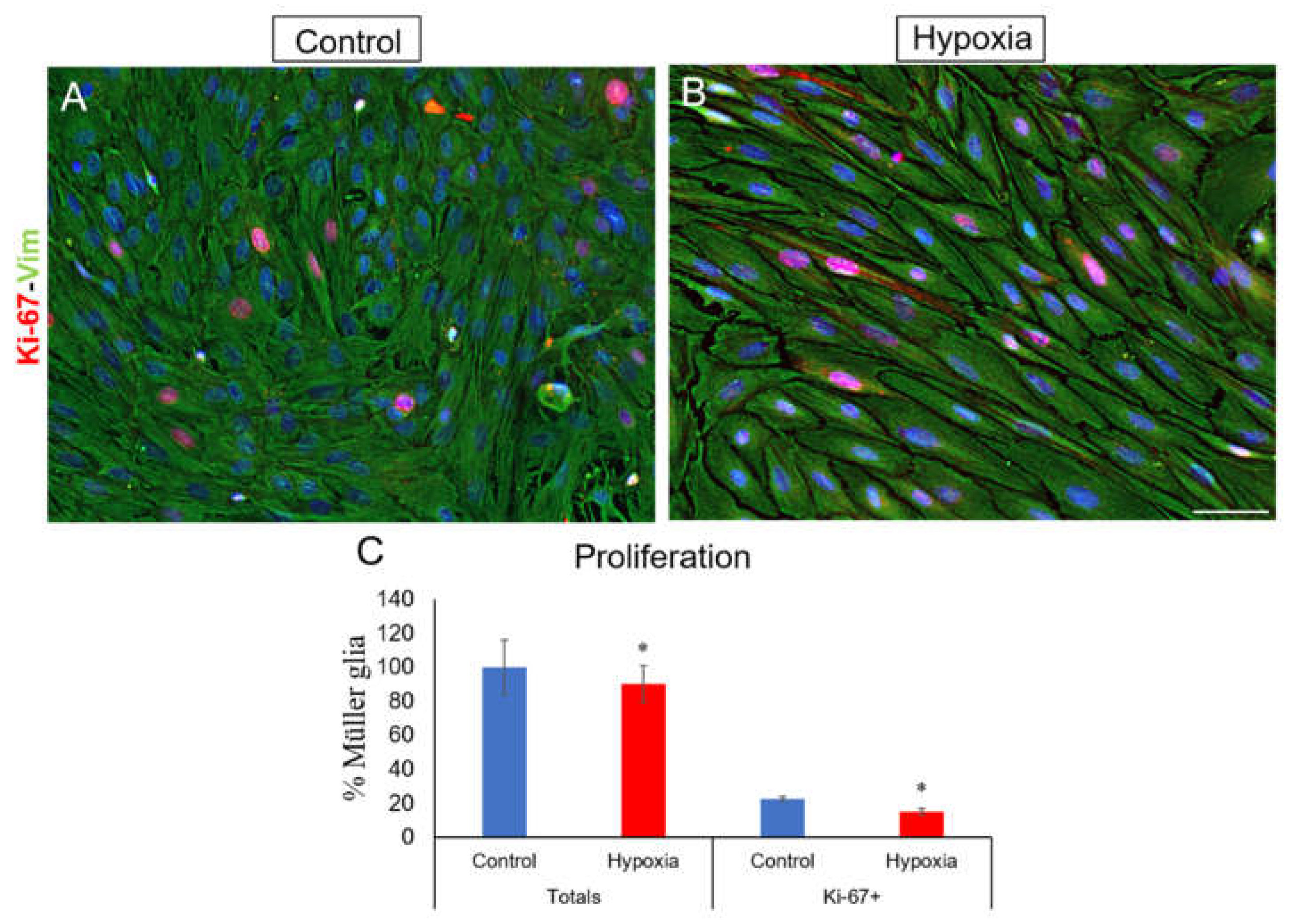

3.5. Müller Glia Proliferation

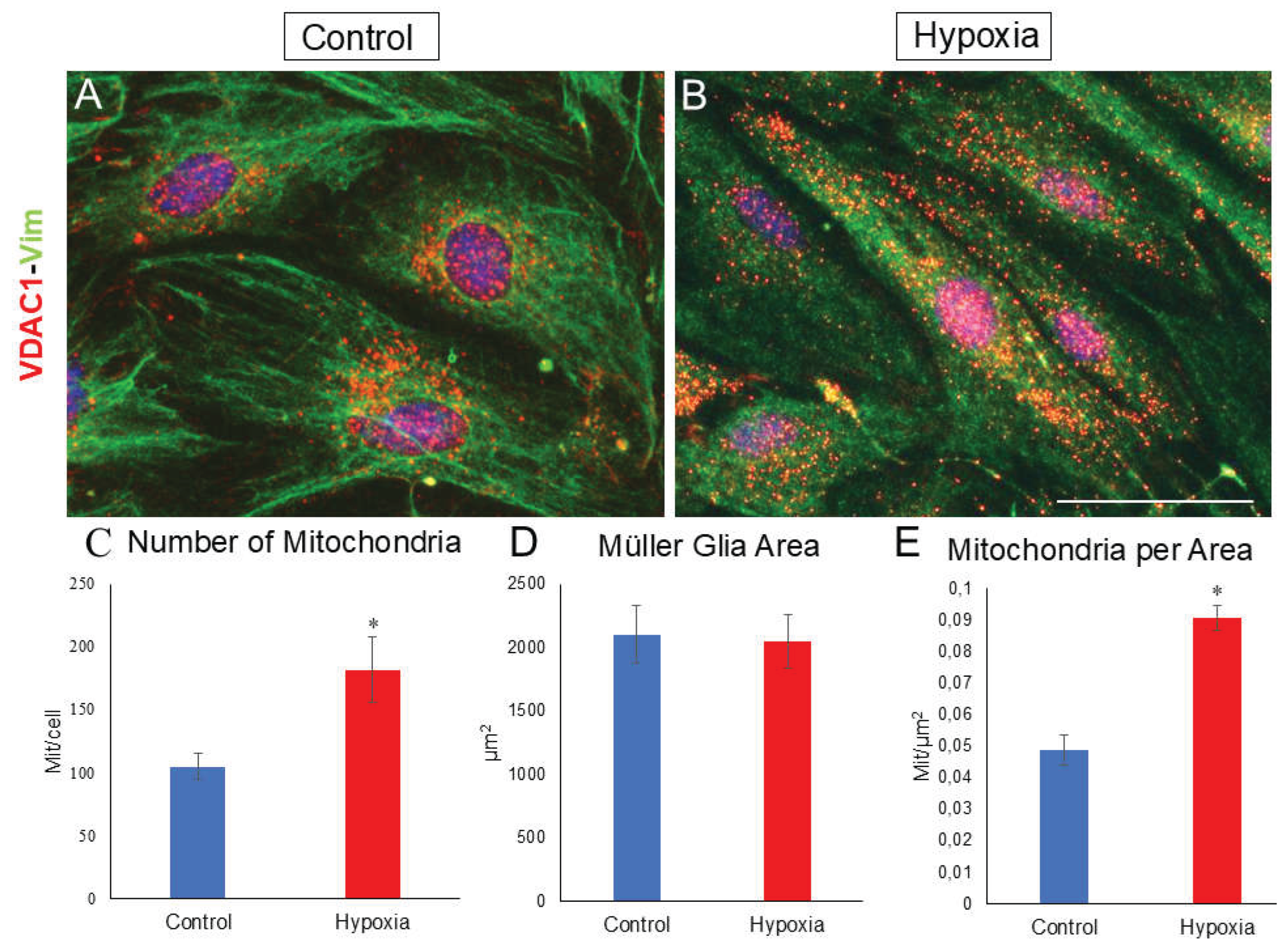

3.6. Metabolic Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARVO | Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CoCl2 | Cobalt(II) chloride |

| CRALBP | Cellular Retinaldehyde |

| DAPI | 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| EBSS | Earle’s Balanced Salt Solution |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| GLAST | Glutamate Aspartate Transporter |

| GS | Glutamine Synthetase |

| HIF | 1- Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 |

| HIF | 1α - Hypoxia - Inducible Factor 1 - alpha |

| HUMMR | Hypoxia Upregulated Mitochondrial Movement Regulator |

| Ki67 | A marker for cellular proliferation |

| MG | Müller Glia |

| MTT | Methyl-Thiazolyl-Tetrazolium |

| NADH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (reduced form) |

| PBS | Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| RGC | Retinal Ganglion Cell |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| VDAC1 | Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel 1 |

References

- Reichenbach, A.; Bringmann, A. New functions of Muller cells. Glia 2013, 61, 651–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecino, E.; Rodriguez, F.D.; Ruzafa, N.; Pereiro, X.; Sharma, S.C. Glia-neuron interactions in the mammalian retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 51, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringmann, A.; Pannicke, T.; Grosche, J.; Francke, M.; Wiedemann, P.; Skatchkov, S.N.; Osborne, N.N.; Reichenbach, A. Muller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2006, 25, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Forster, V.; Hicks, D.; Vecino, E. In vivo expression of neurotrophins and neurotrophin receptors is conserved in adult porcine retina in vitro. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 4532–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereiro, X.; Miltner, A.M.; La Torre, A.; Vecino, E. Effects of Adult Muller Cells and Their Conditioned Media on the Survival of Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Ganglion Cells. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzafa, N.; Pereiro, X.; Lepper, M.F.; Hauck, S.M.; Vecino, E. A Proteomics Approach to Identify Candidate Proteins Secreted by Muller Glia that Protect Ganglion Cells in the Retina. Proteomics 2018, 18, e1700321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, A.; Bringmann, A. Glia of the human retina. Glia 2020, 68, 768–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, A., 3rd. Energy requirements of CNS cells as related to their function and to their vulnerability to ischemia: a commentary based on studies on retina. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1992, 70 (Suppl. 1), S158–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshaq, R.S.; Wright, W.S.; Harris, N.R. Oxygen delivery, consumption, and conversion to reactive oxygen species in experimental models of diabetic retinopathy. Redox Biol 2014, 2, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimble, E.A.; Svoboda, R.A.; Ostroy, S.E. Oxygen consumption and ATP changes of the vertebrate photoreceptor. Exp Eye Res 1980, 31, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzafa, N.; Rey-Santano, C.; Mielgo, V.; Pereiro, X.; Vecino, E. Effect of hypoxia on the retina and superior colliculus of neonatal pigs. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, C.; Foulds, W.S.; Ling, E.A. Blood-retinal barrier in hypoxic ischaemic conditions: basic concepts, clinical features and management. Prog Retin Eye Res 2008, 27, 622–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, K.; Mertsch, S.; Theodoropoulou, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Copland, D.A.; Scott, L.M.; Dick, A.D.; Schrader, S.; Liu, L. Muller Cells Stabilize Microvasculature through Hypoxic Preconditioning. Cell Physiol Biochem 2019, 52, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jassim, A.H.; Nsiah, N.Y.; Inman, D.M. Ocular Hypertension Results in Hypoxia within Glia and Neurons throughout the Visual Projection. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, A.; Kang, X.; Cen, J.; et al. A(2A)R Antagonists Upregulate Expression of GS and GLAST in Rat Hypoxia Model. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 2054293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Hoh, J.; Liu, J. Muller cells in pathological retinal angiogenesis. Transl Res 2019, 207, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereiro, X.; Ruzafa, N.; Acera, A.; Urcola, A.; Vecino, E. Optimization of a Method to Isolate and Culture Adult Porcine, Rats and Mice Muller Glia in Order to Study Retinal Diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafai, Y.; Iandiev, I.; Wiedemann, P.; Reichenbach, A.; Eichler, W. Retinal endothelial angiogenic activity: effects of hypoxia and glial (Muller) cells. Microcirculation 2004, 11, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hasan, O.; Arzeno, A.; Benowitz, L.I.; Cafferty, W.B.; Strittmatter, S.M. Axonal regeneration induced by blockade of glial inhibitors coupled with activation of intrinsic neuronal growth pathways. Exp Neurol 2012, 237, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergorul, C.; Ray, A.; Huang, W.; Wang, D.Y.; Ben, Y.; Cantuti-Castelvetri, I.; Grosskreutz, C.L. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and some HIF-1 target genes are elevated in experimental glaucoma. J Mol Neurosci 2010, 42, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, A.H.; Fan, Y.; Pappenhagen, N.; Nsiah, N.Y.; Inman, D.M. Oxidative Stress and Hypoxia Modify Mitochondrial Homeostasis During Glaucoma. Antioxid Redox Signal 2021, 35, 1341–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Q.; Costa, M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). Mol Pharmacol 2006, 70, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, B.; Hu, M.; Qian, L. HIF-1alpha and Caspase-3 expression in aggressive papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 2022, 20, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Nakamura, K.; Oku, H.; Horie, T.; Kida, T.; Takai, S. Immunohistological Study of Monkey Foveal Retina. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, K.; Kocemba-Pilarczyk, K.; Zarzycka, M.; Dudzik, P.; Trojan, S.E.; Laidler, P. In vitro culture Muller cell model to study the role of inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique in macular hole closure. J Physiol Pharmacol 2021, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, E.; Eaves, C.J. Paradoxical roles of caspase-3 in regulating cell survival, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. J Cell Biol 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Nawaz, M.I.; Siddiquei, M.M.; Abu El-Asrar, A.M. Apocynin ameliorates NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) induced oxidative damage in the hypoxic human retinal Muller cells and diabetic rat retina. Mol Cell Biochem 2021, 476, 2099–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Ding, P.; Xiao, L.; Hu, M.; Hu, Z. Nestin is induced by hypoxia and is attenuated by hyperoxia in Muller glial cells in the adult rat retina. Int J Exp Pathol 2011, 92, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, A.O.; Lakk, M.; Rudzitis, C.N.; Krizaj, D. TRPV4 and TRPC1 channels mediate the response to tensile strain in mouse Muller cells. Cell Calcium 2022, 104, 102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizaj, D.; Ryskamp, D.A.; Tian, N.; Tezel, G.; Mitchell, C.H.; Slepak, V.Z.; Shestopalov, V.I. From mechanosensitivity to inflammatory responses: new players in the pathology of glaucoma. Curr Eye Res 2014, 39, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemussie, E.; Wijono, M.; Ruiz, G. Muller cell response to laser-induced increase in intraocular pressure in rats. Glia 2004, 47, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Cenalmor, P.; Martinez, A.E.; Moneo-Corcuera, D.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, P.; Perez-Sala, D. Oxidative stress elicits the remodeling of vimentin filaments into biomolecular condensates. Redox Biol 2024, 75, 103282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gincel, D.; Vardi, N.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. Retinal voltage-dependent anion channel: characterization and cellular localization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002, 43, 2097–2104. [Google Scholar]

- Adzigbli, L.; Sokolov, E.P.; Wimmers, K.; Sokolova, I.M.; Ponsuksili, S. Effects of hypoxia and reoxygenation on mitochondrial functions and transcriptional profiles of isolated brain and muscle porcine cells. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 19881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LFS, E.S.; Brito, M.D.; Yuzawa, J.M.C.; Rosenstock, T.R. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Changes in High-Energy Compounds in Different Cellular Models Associated to Hypoxia: Implication to Schizophrenia. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 18049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benej, M.; Papandreou, I.; Denko, N.C. Hypoxic adaptation of mitochondria and its impact on tumor cell function. Semin Cancer Biol 2024, 100, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Scimia, M.C.; Wilkinson, D.; Trelles, R.D.; Wood, M.R.; Bowtell, D.; Dillin, A.; Mercola, M.; Ronai, Z.A. Fine-tuning of Drp1/Fis1 availability by AKAP121/Siah2 regulates mitochondrial adaptation to hypoxia. Mol Cell 2011, 44, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebsch, M.; Klemm, M.; Haueisen, J.; Hammer, M. Hypoxia-induced redox signalling in Muller cells. Acta Ophthalmol 2017, 95, e337–e339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukyanova, L.D.; Kirova, Y.I. Mitochondria-controlled signaling mechanisms of brain protection in hypoxia. Front Neurosci 2015, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, L.; Peng, R. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 and Mitochondria: An Intimate Connection. Biomolecules 2022, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lim, S.; Hoffman, D.; Aspenstrom, P.; Federoff, H.J.; Rempe, D.A. HUMMR, a hypoxia- and HIF-1alpha-inducible protein, alters mitochondrial distribution and transport. J Cell Biol 2009, 185, 1065–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antigen | Host | Supplier (Ref) | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α | Mouse | Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (sc-13515) | 1:50 |

| Vimentin | Mouse | Dako (M0725) | 1:1000 |

| Vimentin | Rabbit | Abcam (ab92547) | 1:2000 |

| Glutamine synthetase | Mouse | Abcam (ab64613) | 1:1000 |

| CRALBP | Rabbit | Abcam (ab154898) | 1:1000 |

| Caspase 3 | Rabbit | Cell Signalling (#9661) | 1:10000 |

| GFAP | Mouse | Sigma (G3893) | 1:1000 |

| GFAP | Rabbit | Sigma-Aldrich (G9269) | 1:1000 |

| Ki-67 | Rabbit | Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (sc-23900) | 1:200 |

| VDAC1 | Rabbit | Abcam (ab15895) | 1:200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).