Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

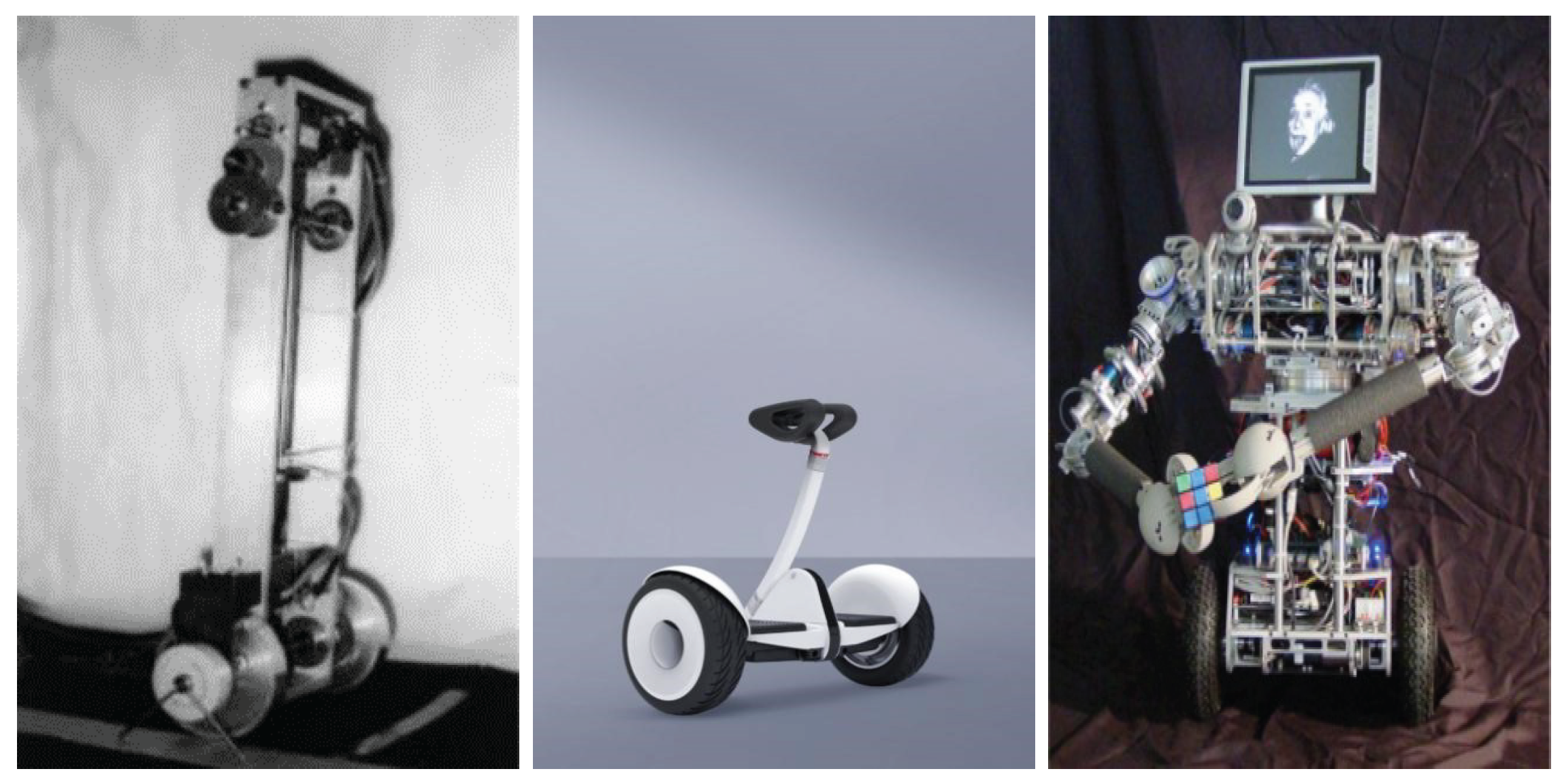

1. Introduction

- A hierarchical sliding mode control (HSMC) scheme is combined with terminal sliding mode control (TSMC) to address the underactuated control problem of the two-wheeled self-balancing robot (TWSBR), resulting in a dual-terminal sliding mode control (DTSMC) law. Furthermore, a modified dual hierarchical terminal sliding mode control (MDHTSMC) scheme is designed based on the duality concept, with stability rigorously verified through Lyapunov theory.

- A modified dual hierarchical terminal sliding mode control (MDHTSMC) scheme is proposed for the TWSBR nonlinear system, accounting for disturbances and uncertainties. Using Lyapunov theory, finite-time convergence on the newly defined MDHTSMC surface is proven, and the arrival and sliding times are explicitly calculated.

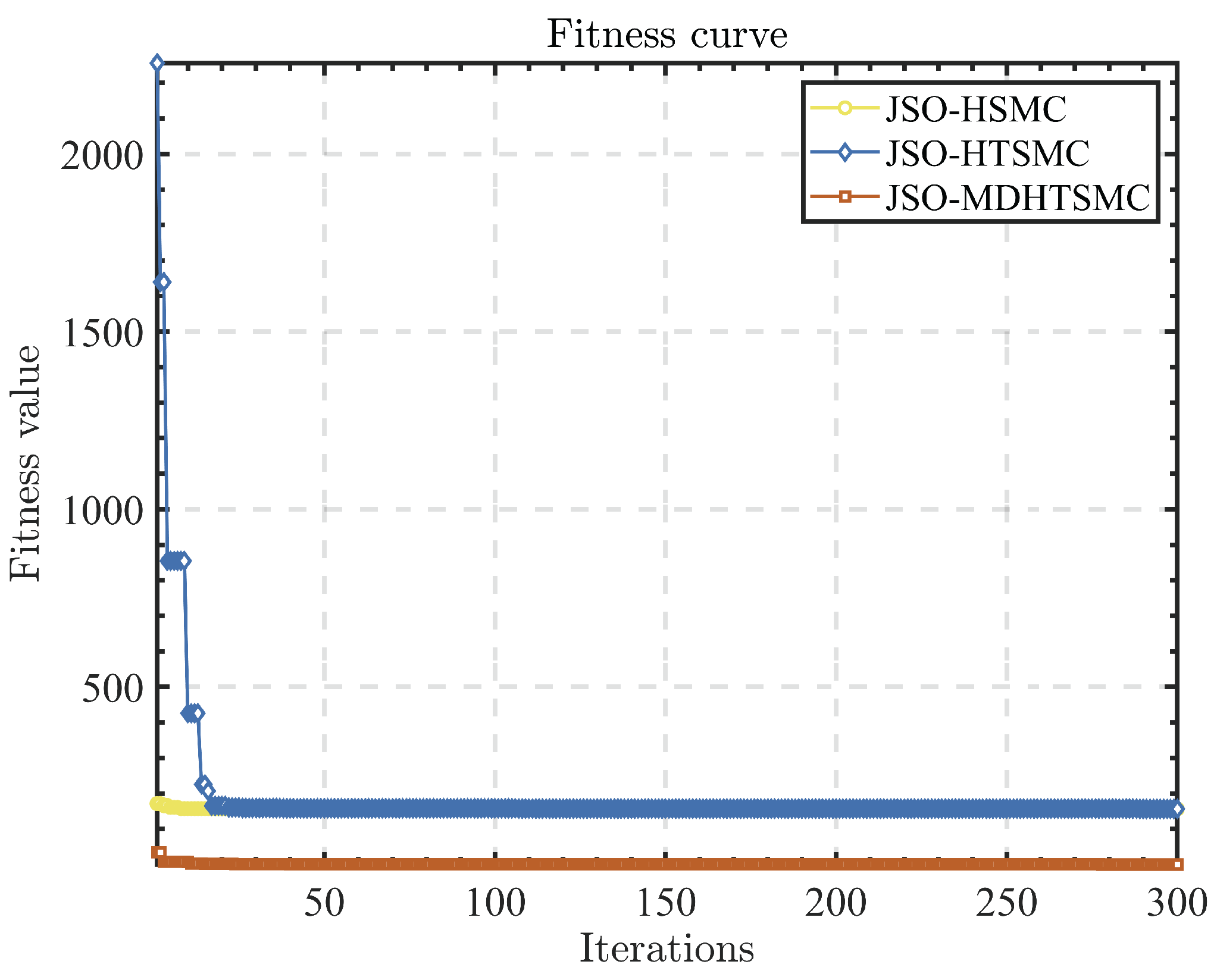

- The Jellyfish Search Optimization (JSO) algorithm is employed to minimize the integral of the time-weighted absolute error (ITAE) by adjusting the x and parameters of the TWSBR, achieving optimal control parameters. These parameters are subsequently fine-tuned for enhanced optimization.

2. Preliminary

2.1. Dynamic Models

2.2. Actuated and Underactuated Subsystems

2.2.1. -subsystem

2.2.2. -subsystem

3. Modified Dual Hierarchical Terminal SMC

3.1. Dynamic Model

3.2. Hierarchical Terminal Sliding Mode Control (HTSMC)

3.3. Dual Hierarchical Terminal SMC (DHTSMC)

3.4. MDHTSM Controller Design for TWSBR

4. Simulation Result

4.1. Optimization Algorithm

4.2. Parameters Tuning

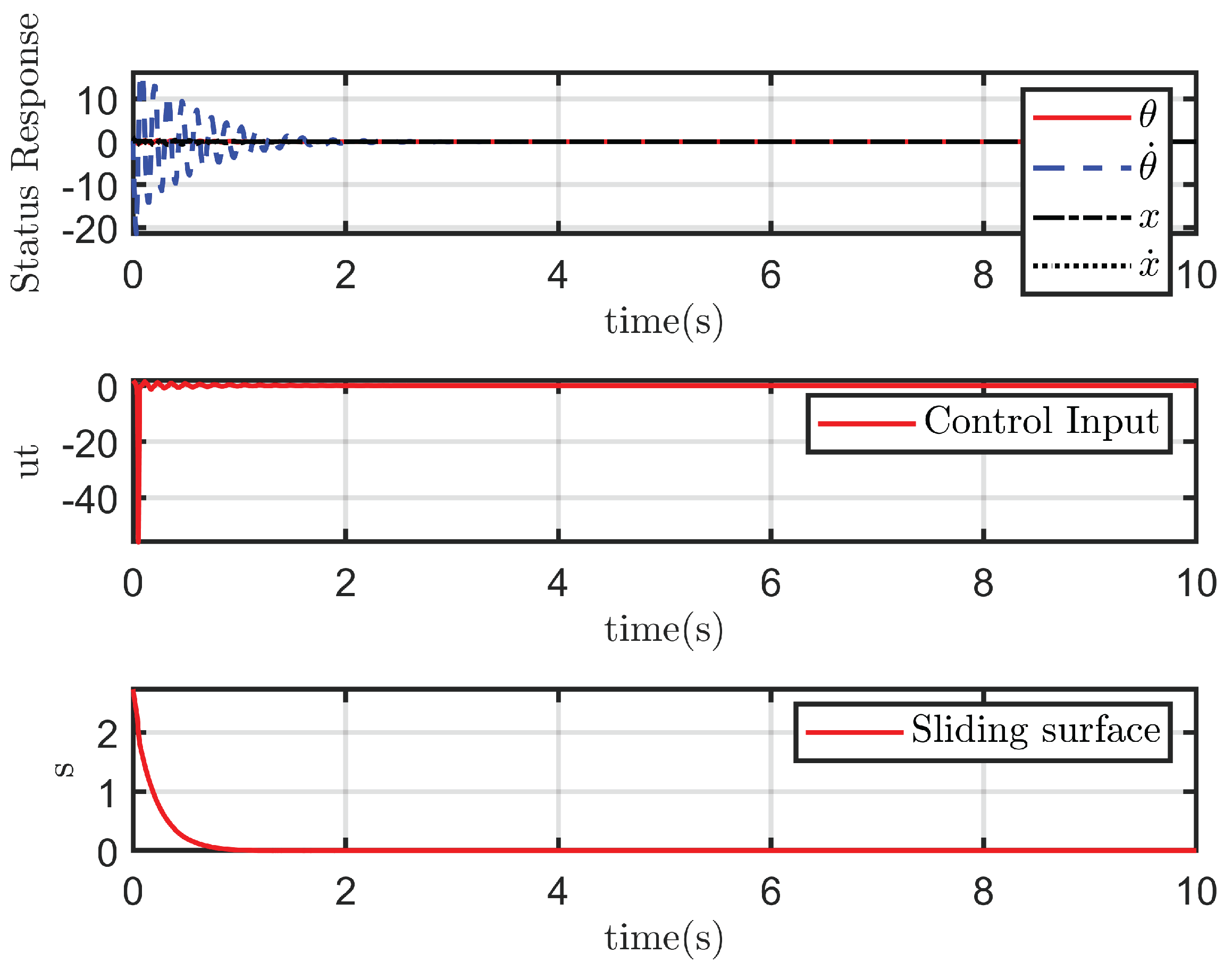

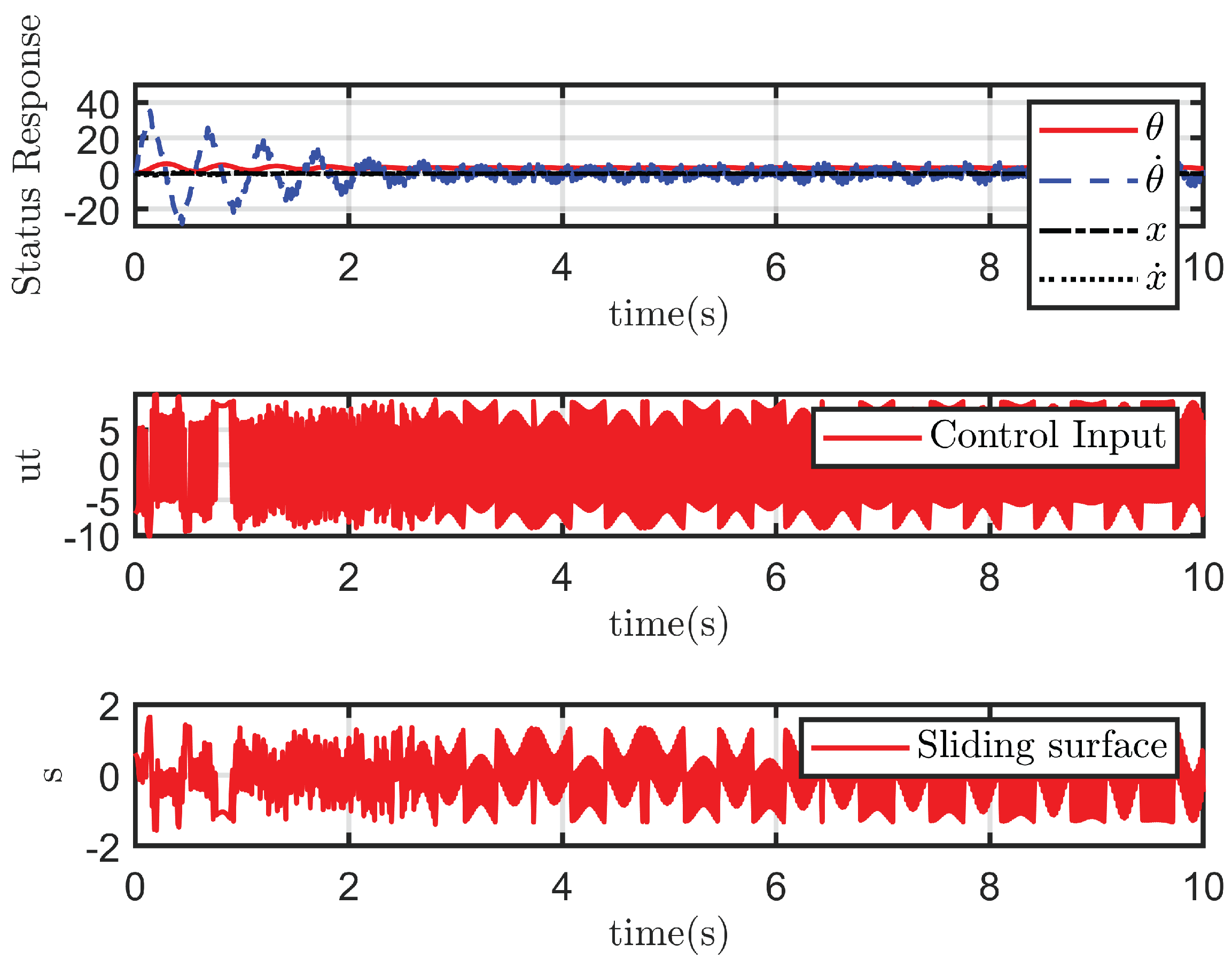

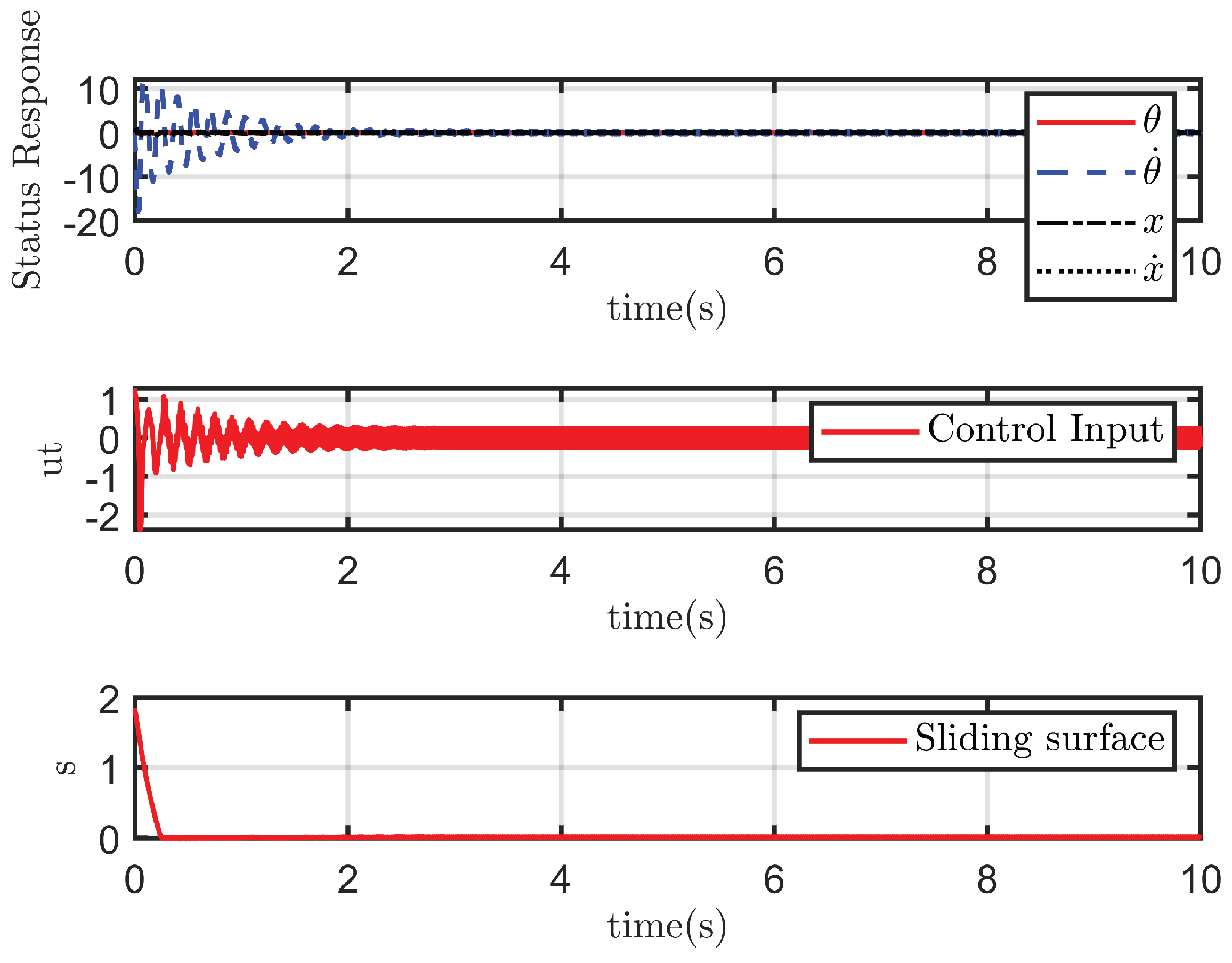

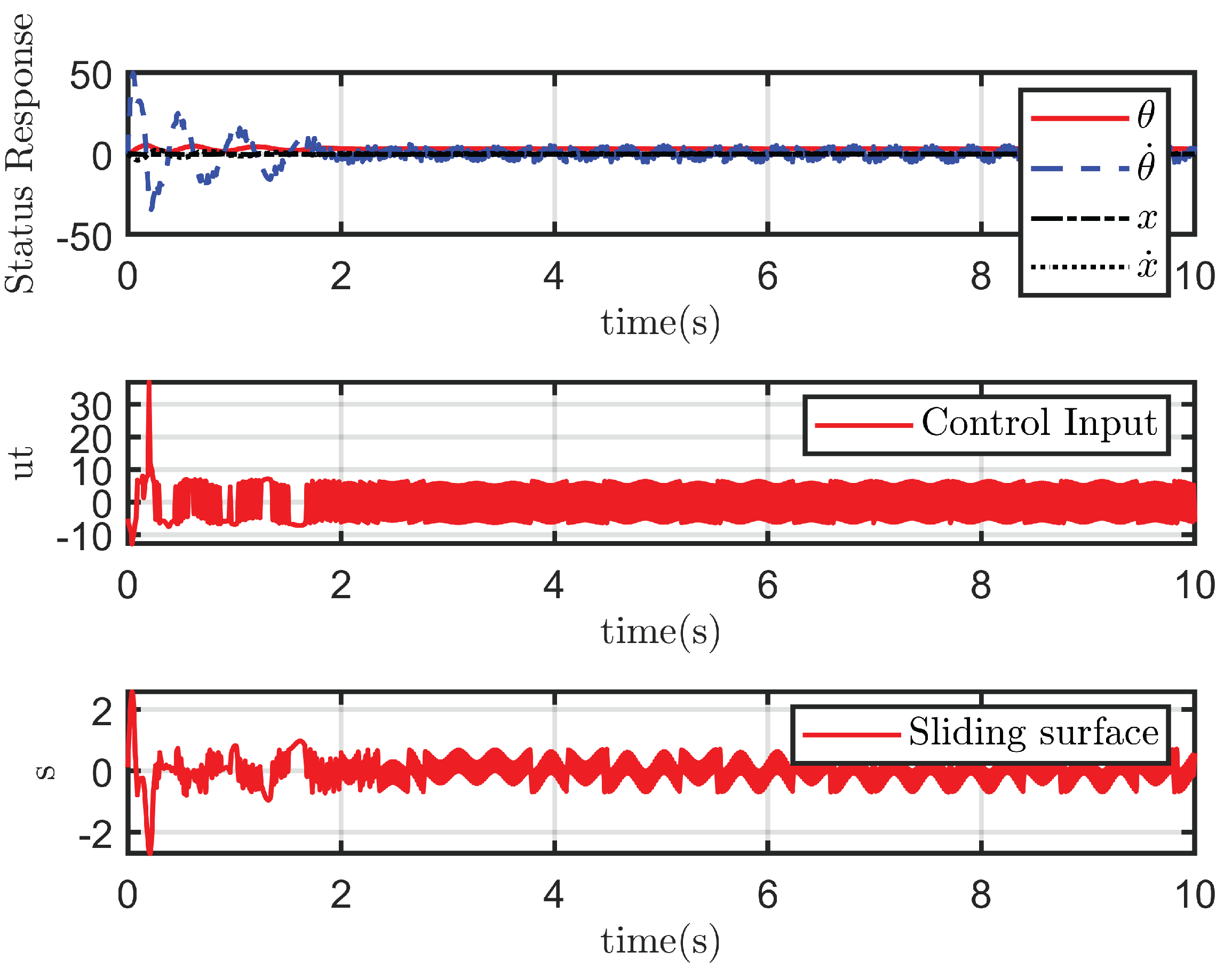

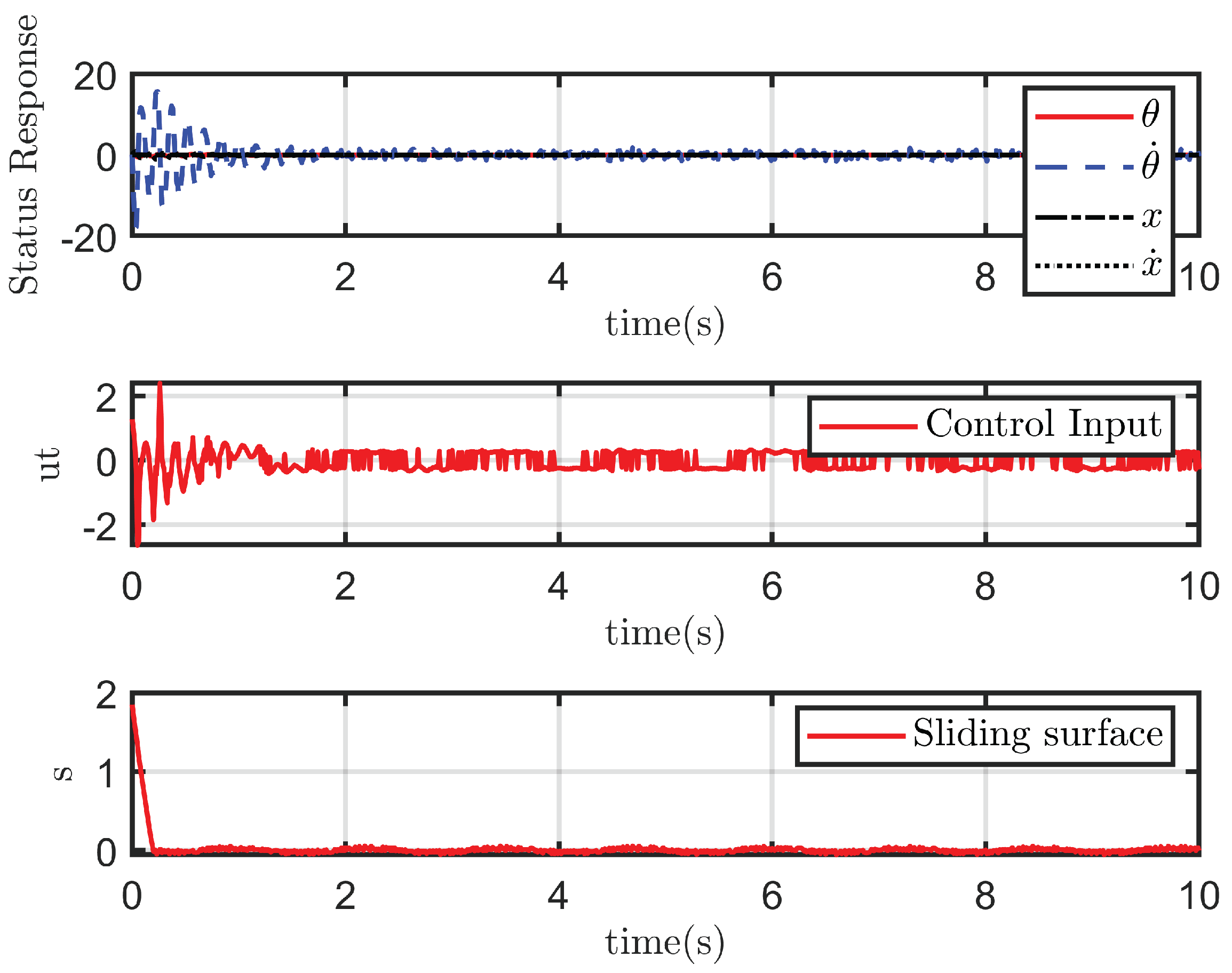

- the performance of each sliding mode controller under ideal, disturbance-free conditions; and

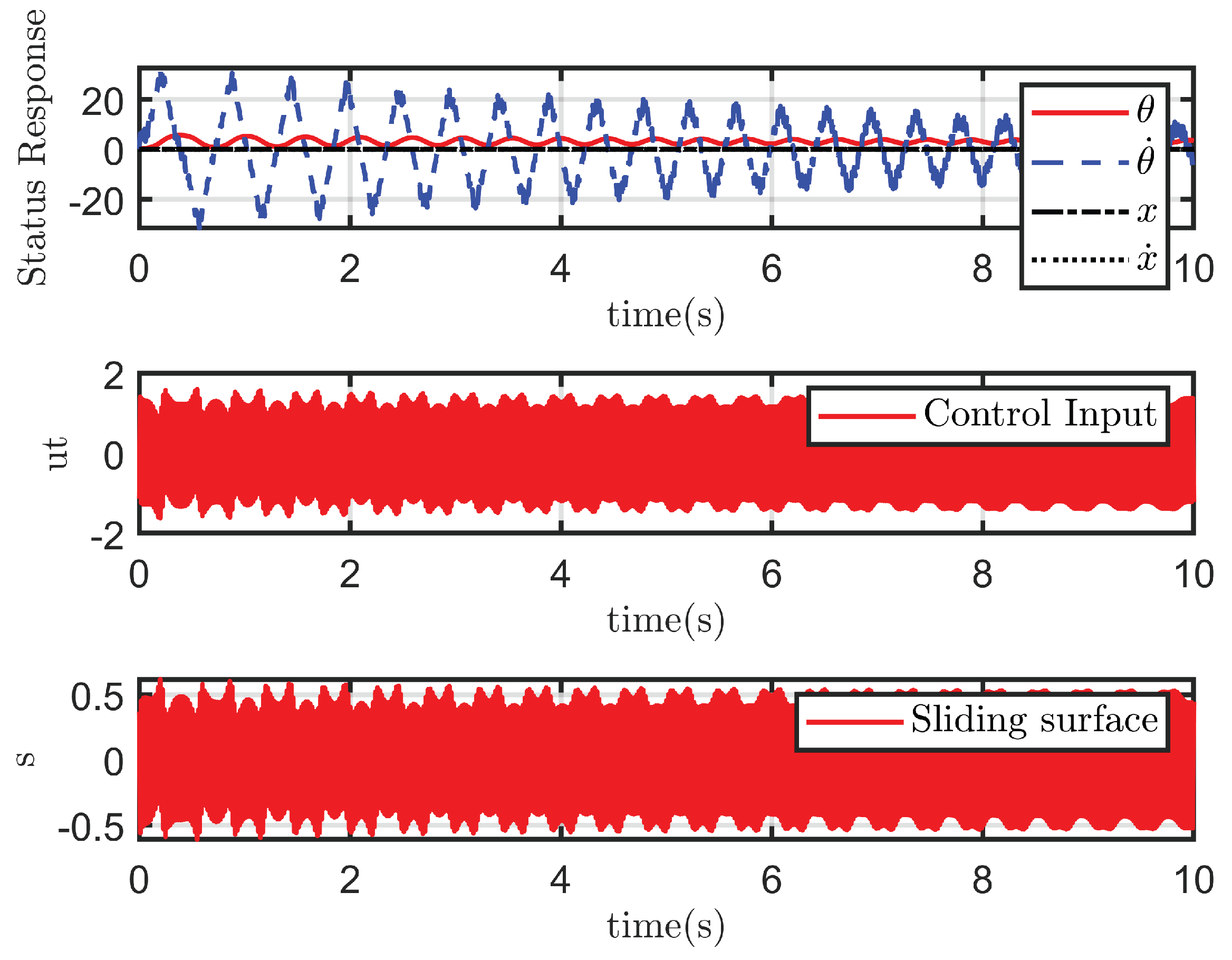

- the performance of each sliding mode controller in the presence of disturbances .

4.2.1. Case 1: Ideal State

4.2.2. Case 2: With Disturbance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TWSBR | Two-Wheeled Self-Balancing Robot |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| TSMC | Terminal Sliding Mode Control |

| HSMC | Hierarchical Sliding Mode Control |

| HTSMC | Hierarchical Terminal Sliding Mode Control |

| DHTSMC | Dual Hierarchical Terminal Sliding Mode Control |

| MDHTSMC | Modified Dual Hierarchical Terminal Sliding Mode Control |

| JSO | Jellyfish Search Optimization |

| ITAE | Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error |

| LQR | Linear Quadratic Regulator |

| PD | Proportional-Derivative |

References

- S. Zhang, J. Yao, Y. Wang, Z. Liu, Y. Xu, and Y. Zhao, “Design and motion analysis of reconfigurable wheel-legged mobile robot,” Defence Technology, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 1023–1040, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Rubio, F. Valero, and C. Llopis-Albert, “A review of mobile robots: Concepts, methods, theoretical framework, and applications,” Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst., vol. 16, no. 2, p. 01–22, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Olmez, G. O. Koca, and Z. H. Akpolat, “Clonal selection algorithm based control for two-wheeled self-balancing mobile robot,” Simulation modelling practice and theory: International journal of the Federation of European Simulation Societies, no. 118, p. 118, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guo, J. Guo, L. Liu, Y. Liu, and J. Leng, “Bioinspired multimodal soft robot driven by a single dielectric elastomer actuator and two flexible electroadhesive feet,” Extreme Mech. Lett., vol. 53, p. 101720, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Khan, T. Chuthong, C. D. Do, M. Thor, P. Billeschou, J. C. Larsen, and P. Manoonpong, “icrawl: an inchworm-inspired crawling robot,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 200 655–200 668, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, Q. Tang, T. Sun, and R. Dong, “Research on stability of the four-wheeled robot for emergency obstacle avoidance on the slope,” Recent Pat. Eng., vol. 15, no. 5, p. 15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Nker, “Proportional controlled moment of gyroscope for two-wheeled self-balancing robot,” J. Vib. Control, 2021.

- D. Voth, “Segway to the future [autonomous mobile robot],” IEEE Intell. Syst., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 5–8, 2005. [CrossRef]

- A. Delgado-Spíndola, R. Campa, E. Bugarin, and I. Soto, “Design and real-time implementation of a nonlinear regulation controller for the rmp-100 segway twip,” Mechatronics, vol. 79, pp. 102 668–, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, X. Cui, Y. Zhu, and S. Tang, “A new self-reconfigurable modular robotic system ubot: Multi-mode locomotion and self-reconfiguration,” in 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. IEEE, 2011, pp. 1020–1025. [CrossRef]

- X. Cui, Y. Zhu, J. Zhao, S. Piao, and E. Yang, “Bio-inspired locomotion control for ubot self-reconfigurable modular robot,” in 2023 International Conference on Control, Automation and Diagnosis (ICCAD). IEEE, 2023, pp. 01–06. [CrossRef]

- D. Y. Gao, P. W. Han, D. S. Zhang, and Y. J. Lu, “Study of sliding mode control in self-balancing two-wheeled inverted car,” Appl. Mech. Mater., vol. 241, pp. 2000–2003, 2013.

- I. Jmel, H. Dimassi, S. Hadj-Said, and F. M’Sahli, “Sliding mode control for two wheeled inverted pendulum under terrain inclination and disturbances,” in 2021 9th International Conference on Systems and Control (ICSC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 467–471. [CrossRef]

- A. Ghahremani and A. K. Khalaji, “Simultaneous regulation and velocity tracking control of a two-wheeled self-balancing robot,” in 2023 International Conference on Control, Automation and Diagnosis (ICCAD). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Arani, H. E. Orimi, W.-F. Xie, and H. Hong, “Comparison of sliding mode controller and state feedback controller having linear quadratic regulator (lqr) on a two-wheel inverted pendulum robot: Design and experiments,” 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Sinha, P. Prasoon, P. K. Bharadwaj, and A. C. Ranasinghe, “Nonlinear autonomous control of a two-wheeled inverted pendulum mobile robot based on sliding mode,” in 2015 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Networks. IEEE, 2015, pp. 52–57. [CrossRef]

- C.-C. Yih, “Sliding-mode velocity control of a two-wheeled self-balancing vehicle,” Asian J. Control, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 1880–1890, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang and J. Lei, “Research on self-balancing control for upright vehicle with two wheels based on sliding mode control,” in 2017 International Conference on Computer Technology, Electronics and Communication (ICCTEC). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1192–1195. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, X. Yan, K. Sirlantzis, and G. Howells, “Regular form-based sliding mode control design on a two-wheeled inverted pendulum,” Int. J. Model. Identif. Control, vol. 37, no. 3/4, pp. 312–320, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Fukushima, K. Muro, and F. Matsuno, “Sliding-mode control for transformation to an inverted pendulum mode of a mobile robot with wheel-arms,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 62, no. 7, pp. 4257–4266, 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Durdevic and Z. Yang, “Hybrid control of a two-wheeled automatic-balancing robot with backlash feature,” in 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR). IEEE, 2013, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- S. Irfan, A. Mehmood, M. T. Razzaq, and J. Iqbal, “Advanced sliding mode control techniques for inverted pendulum: Modelling and simulation,” Engineering science and technology, an international journal, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 753–759, 2018.

- N. Zheng, Y. Zhang, Y. Guo, and X. Zhang, “Hierarchical fast terminal sliding mode control for a self-balancing two-wheeled robot on uneven terrains,” in 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC). IEEE, 2017, pp. 4762–4767. [CrossRef]

- M. Hou, X. Zhang, D. Chen, and Z. Xu, “Hierarchical sliding mode control combined with nonlinear disturbance observer for wheeled inverted pendulum robot trajectory tracking,” Appl. Sci. (Basel), vol. 13, no. 7, p. 4350, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Ping, W. Hai, L. Linfeng, K. Huifang, Y. Ming, J. Canghua, et al., “A novel hierarchical sliding mode control strategy for a two-wheeled self-balancing vehicle,” in 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC). IEEE, 2017, pp. 3731–3736. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, H. Wang, Y. Huang, Z. Ping, M. Yu, X. Zheng, et al., “Robust hierarchical sliding mode control of a two-wheeled self-balancing vehicle using perturbation estimation,” Mech. Syst. Signal Process., vol. 139, p. 106584, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Do and G. Seet, “Motion control of a two-wheeled mobile vehicle with an inverted pendulum,” J. Intell. Robot. Syst., vol. 60, no. 3-4, pp. 577–605, 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. Grasser, A. D’arrigo, S. Colombi, and A. C. Rufer, “Joe: A mobile, inverted pendulum,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 107–114, 2002. [CrossRef]

- E. Moulay and W. Perruquetti, “Finite time stability and stabilization of a class of continuous systems,” J. Math. Anal. Appl., vol. 323, no. 2, pp. 1430–1443, 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Levant, “Sliding order and sliding accuracy in sliding mode control,” Int. J. Control, vol. 58, no. 6, pp. 1247–1263, 1993. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, J. Yi, D. Zhao, and D. Liu, “Design of a stable sliding-mode controller for a class of second-order underactuated systems,” IEE Proc. Contr. Theory Appl., vol. 151, no. 6, pp. 683–690, 2004. [CrossRef]

| Notation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Torques acting on the left and right wheels provided by wheel motors | |

| Interacting forces between the left and right wheels and the chassis | |

| Friction forces acting on the left and right wheels | |

| External forces acting on the left and right wheels | |

| Rotational angles of the left and right wheels | |

| Displacements of the left and right wheels along the x-axis | |

| Tilt angle of the vehicle body | |

| Rotational angle of the vehicle | |

| x | Displacement of the vehicle along the direction of the longitudinal velocity |

| v | Longitudinal velocity of the vehicle |

| m | Mass of the inverted pendulum |

| M | Mass of the chassis |

| Mass of the wheels | |

| R | Radius of the wheels |

| l | Distance between the body center of gravity and the wheel axis |

| D | Distance between the two wheels along the axle center |

| Current position of the vehicle on the plane | |

| Interacting force between the pendulum and the chassis on the x-axis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).