1. Introduction

Neural interfaces have undergone significant advancements in recent years, with flexible microelectrode arrays (fMEAs) emerging as a powerful tool for high-resolution electrophysiological recordings. Unlike traditional rigid electrodes, flexible MEAs conform to biological tissues, minimizing mechanical mismatch and improving long-term stability [

1,

2]. The stiffness of brain tissue (~100 Pa - 10 kPa) contrasts significantly with polymeric implants, which range from 1 GPa (polyimide-based) to 1 MPa (PDMS-based) [

3,

4]. The use of ultra-thin fMEAs (less than 5 µm in thickness) mitigates this mismatch, minimizing the foreign body response. Furthermore, the use of nanostructures enhances electrode performance by increasing the electrode’s surface area, thus improving their impedance. Additionally, different nanostructures exhibit peculiar properties in terms of biocompatibility, cell differentiation, cell coupling, etc., and they interact differently with the cells depending on their shape, distribution (ordered and aligned or disordered structures), and surface functionalization. Among the diverse materials, Zinc Oxide nanorods (ZnO NRs) show interesting features such as bio-interface. Indeed, nanostructured ZnO is well-known for the wide variety of nanostructures that can be grown using scalable and low-temperature methods, for its remarkable optical and electrical properties (such as the possibility to tune the material's resistivity over several orders of magnitude), and for its potential piezoelectricity [

5,

6,

7]. In case of brain interface and electrodes fabrication, ZnO NRs can be coated with different metals (Au, Ti, Pt, etc. [

8]) or combined with 2D materials [

9,

10,

11] to control the device impedance and tune the electrode properties in terms of signal recording and/or brain stimulation tasks. Nanostructured flexible interfaces have been already reported as valuable electrophysiological tool to investigate brain activity in both healthy and pathological conditions [

12,

13] with the aim of finding peculiar signal patterning and unrevealing cognitive processes. In particular, some disordered nanostructures have been implemented not only on neurons but also as glial platforms to monitor, for example, the ion current exchange among astrocytes during the different physiological mechanisms [

14]. In this respect, the usage of nanostructured MEAs provides additional information in the electrophysiological measurements, thus opening up interesting insights into the interpretation of these bio-signals.

These advantages have made nano-MEAs particularly useful for studying dynamic pathological conditions, including ischemia models where precise neural activity monitoring is essential. The application of flexible MEAs in ischemia models has opened new avenues for understanding the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms of ischemic injury and recovery. These tools facilitate real-time recording of neural network dynamics, offering insights that are critical for developing targeted therapeutic interventions. Flexible MEAs are designed to operate in ex vivo applications as well as chronic in vivo recordings.

Brain ischemia is characterized by a reduction in cerebral blood flow, leading to oxygen and glucose deprivation and subsequent ATP depletion. This metabolic failure initiates a complex cascade of cellular responses involving both neurons and glial cells. Hallmark of ischemic pathology is the disruption of ionic homeostasis, with particularly severe effects on neurons and astrocytes. ATP depletion compromises the function of pivotal ionic pumps, such as Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase and Ca²⁺-ATPase, resulting in intracellular accumulation of Na⁺, elevated extracellular K⁺, and increased Ca²⁺ influx [

15,

16]. Consequently, neurons undergo rapid and sustained depolarization, triggering excessive glutamate release and promoting excitotoxicity [

17]. This ionic dysregulation further propagates into spreading depolarizations (SDs), waves of near-complete depolarization of neurons and glia across the gray matter. Under ischemic conditions, recurrent SDs exacerbate ATP depletion and ionic imbalances, promote further glutamate release and worsen neuronal damage [

18].

Astrocytes are essential regulators of ion and neurotransmitter homeostasis under both physiological and pathological conditions. They buffer extracellular K⁺ and uptake glutamate, maintaining neuronal excitability and protecting against excitotoxicity. However, under severe ischemic stress, astrocytic function is severely impaired. Their diminished buffering capacity and disrupted glutamate uptake facilitate SD propagation, impair neuron-glia communication and contribute to secondary injury through the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [

19]. Thus, brain ischemia induces profound ionic disturbances that drive neuronal depolarization and recurrent SDs. The progression of ischemic injury is tightly linked to the collapse of ion homeostasis, particularly within neurons and astrocytes.

These events can be effectively monitored using extracellular electrodes that detect changes in local field potentials, typically observed as negative shifts in the direct current (DC) potential, along with alterations in extracellular ion concentrations.

To explore these pathophysiological mechanisms in a controlled environment, acute brain slices were used as an ex-vivo model, offering a well-preserved local circuitry and cellular microenvironment. This approach allowed for precise manipulation and high-resolution recording of neural activity during ischemia-like conditions. In this study, we fabricated, characterized, and applied nanostructured fMEAs (nano-fMEAs) for recording ischemia-induced neural activity in acute brain slices. These nano-engineered electrodes were designed to enhance sensitivity and improve the signal-to-noise ratio under ischemic conditions. Here, we demonstrate their efficacy by recording neural responses under both OGD and hyperkalemic conditions and by benchmarking them against conventional flat electrodes of equivalent dimensions. Our findings underscore the superior performance of nano-fMEAs respect the flat flexible MEA in detecting ischemia-induced electrophysiological changes with higher fidelity. This platform offers a powerful tool for studying ischemic pathophysiology and evaluating potential neuroprotective strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of Flexible Microelectrode Arrays (fMEAs)

Substrate Preparation

The fabrication of flexible microelectrode arrays (fMEAs) follows a multistep process, beginning with the preparation of a rigid substrate. A 3-inch silicon oxide (SiO

2) wafer, used as polyimide holder, is cleaned in a 5% hydrofluoric acid solution for 5 seconds to remove impurities, followed by rinsing with deionized water and drying under nitrogen flow. A 4 µm thick layer of Polyimide PI2611 (HD Microsystems™ GmbH, Greifswald, Germany) is utilized as the substrate for the flexible microelectrode array

[20,21,22]. The polyimide is applied to the wafer by a spin-coating process (2000 RPM for 60 s). The sample is then cured at 250°C for 4 hours in a nitrogen atmosphere. Following polyimide curing, reactive ion etching is performed under these conditions: 90% oxygen, 20% power, and 45 mTorr pressure for 30 seconds to increase polyimide surface roughness and improve metal adhesion or Zinc Oxide nano-precursor deposition. Two types of fMEAs are fabricated: standard flat fMEAs and nanostructured fMEAs (nano-fMEAs).

Zinc Oxide Nanorods Growth

For the nanostructured fMEAs, ZnO NRs were synthesized via chemical bath deposition. For this process, the wafer with the first polyimide layer is spin-coated with a 0.1 wt% solution of Zinc Oxide nanoparticles (Sigma-Aldrich) which act as seeds for the nanostructure growth. The growth occurs in a 2.1:1 zinc nitrate hexahydrate and hexamethylenetetramine (Zn(NO

3)

2:HMTA) aqueous solution at 85°C for 60 minutes

[11,23,24,25]. Afterwards, the sample is cleaned and dried, and the procedure continues as with the traditional fMEA.

Device Assembly and Connectivity

Each fMEA and nano-fMEA is mechanically detached from the wafer and bonded to a custom printed circuit board (PCB), which acts as an interface to connect the MEA to the recording board. The acquisition system, an in-house custom-made recording board, supports up to 32 channels and enables real-time data visualization through a customized software made in MatLab

[26]. This system can amplify, filter, and digitalize the signals through a RHD2000 chip by INTAN Technology. The low-noise amplifier can reach a maximum value of 200x.

2.2. Devices Characterization

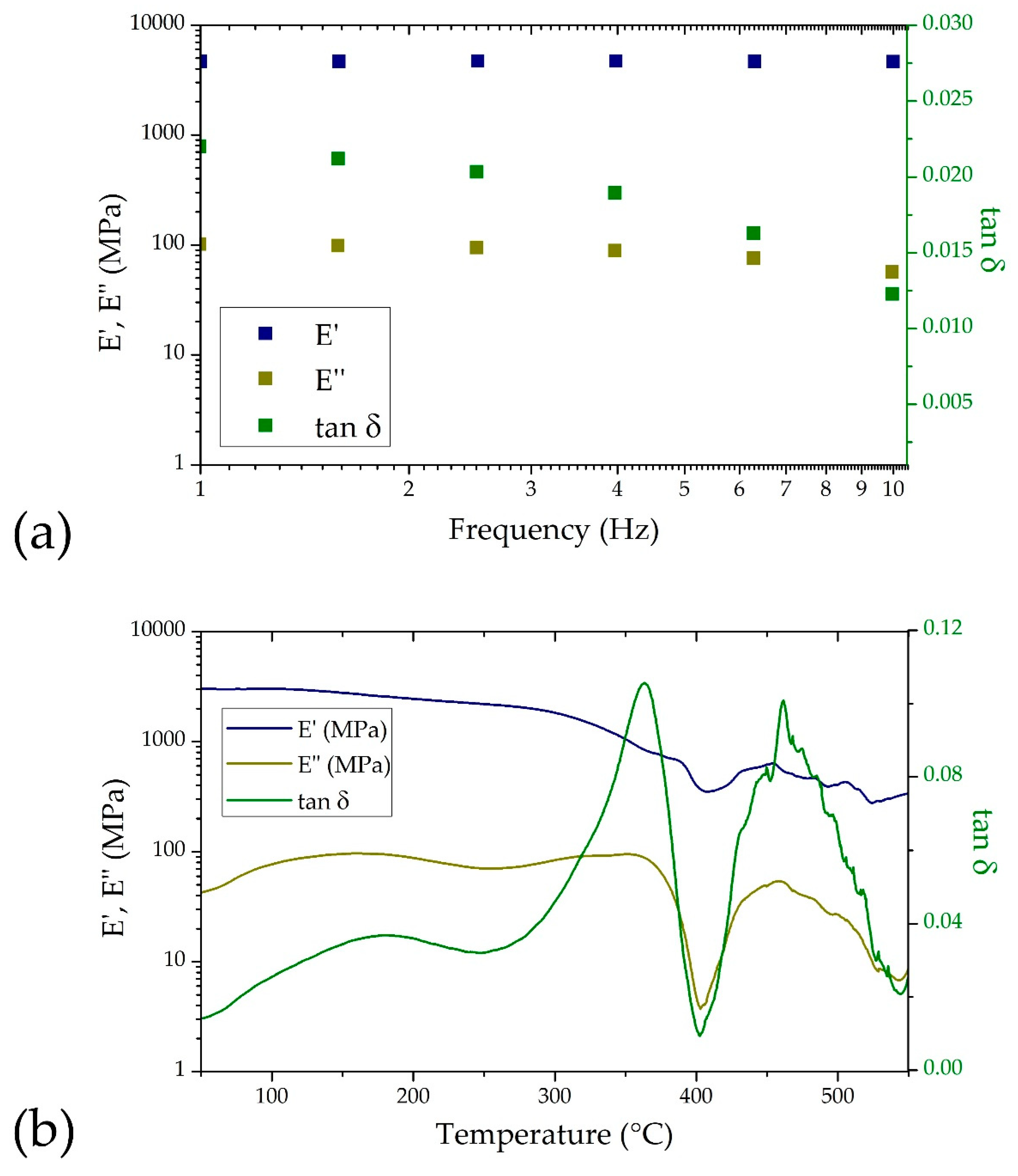

DMA Characterization

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) was performed using a TA Instruments HR20 rheometer in tension mode. Sample strips had dimensions of 40 mm (length), 8 mm (width), and 23 µm (thickness).

To identify the linear viscoelastic region (LVR) of the material, preliminary strain sweep tests were carried out at 40°C. These tests were conducted at oscillation frequencies of 0.1 Hz, 1 Hz, and 10 Hz, with strain amplitudes ranging from 0.001% to 1%.

Frequency sweep was performed at 40°C, over a frequency range of 1 to 10 Hz under a constant tensile force of 2 N.

For thermal analysis, a temperature sweep was conducted from 50°C to 550°C at a fixed frequency of 1 Hz. The heating rate was set to 3°C/min, with an oscillation strain of 0.1% and a constant tensile load of 1 N. All temperature-dependent tests were performed under a continuous nitrogen flow to prevent thermal oxidation.

Thermogravimetric Analysis

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) was carried out using a TA Instruments Discovery TGA 55. Samples were placed in platinum crucibles and heated from 25°C to 800°C under a nitrogen atmosphere (flow rate: 40 mL/min). The heating rate was fixed at 10°C/min.

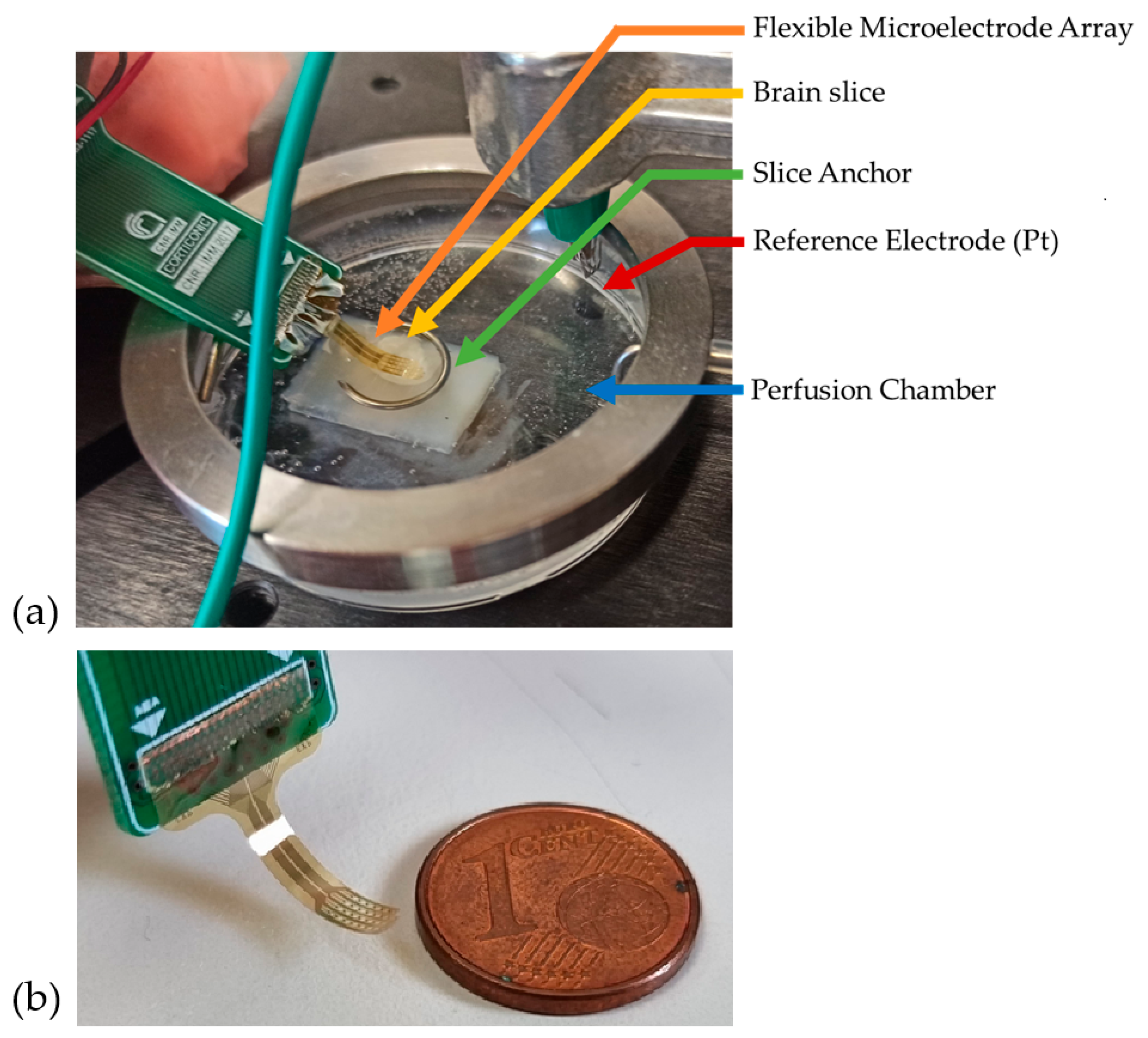

SEM Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to characterize the morphology of the nanostructure (Zinc Oxide nanorods) present in the nano-fMEAs. In this work, SEM analysis was conducted using a Zeiss Sigma 300 microscope. Imaging was performed at a working distance of 5 cm with a beam energy of 3 keV.

EIS Characterization

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was carried out to characterize the electrical properties of the fMEA. EIS was conducted using an AMETEK-VersaSTAT® 4 potentiostat. Measurements were performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), a widely used electrolyte in biological research due to its ability to mimic physiological conditions. The PBS solution consisted of a saline mixture containing Na₂HPO₄, NaCl, KCl, and K₂HPO₄.

A platinum (Pt) electrode served as the reference electrode, while a gold (Au) electrode functioned as the counter electrode. The fabricated ZnO electrodes were used as the working electrodes. Experiments were carried out at room temperature in a Faraday cage, using a DC bias of 0 V and an AC signal of 10 mV over a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 10 kHz.

2.3. System Testing

Biological Samples Preparation and Perfusion

All procedures involving the use of laboratory mice were performed in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of November 24, 1986 (86/609/EEC) and the Animal Welfare Guidelines approved by the Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Czech Academy of Sciences (approval number 50/2020). Three-month-old male and female GFAP/EGFP mice were deeply anaesthetized with sodium-pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, intraperitoneally), transcardially perfused with cold (4℃) isolation solution and decapitated. The brains were quickly dissected, and 300 µm thick slices were prepared using a cooled Leica VT1200S vibrating microtome. The slices were kept for 30 minutes in the isolation solution at 34°C, followed by another 30 minutes at room temperature in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). The slices were subsequently kept at room temperature in aCSF for a maximum of 5 hours. Two experimental solutions were employed to mimic ischemic conditions in acute brain slices: OGD solution or aCSF with elevated potassium concentration (10 mM K

+), referred to as hyperkalemic solution. In our experimental setup, brain slices were exposed to the stimulus for 5 minutes. The velocity of perfusion was 4.6 ml/min (peristaltic pump PCD 31.2, Kouril, CZ). The composition of solutions is listed in

Table 1. All bicarbonate solutions, except for OGD, were gassed with 95% O

2 and 5% CO

2 to maintain a pH of 7.4. The OGD solution was saturated with 5% O

2, 5% CO

2, and 90% N

2.

Cell Culture Preparation for In Vitro Biocompatibility Testing

The neural stem/progenitor cell (NS/PCs) culture was prepared as previously described (doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.09.026). Briefly, after decapitation, the frontal lobe of the neonatal GFAP/EGFP mouse brain was quickly isolated. Using a 1-ml-pipette, the tissue was mechanically dissociated. The cells were subsequently filtered through a 70 µm cell strainer into a Petri dish with proliferation medium containing Neurobasal-A medium (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, United States), supplemented with B27 supplement (B27; 2%; Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, United States), L-glutamine (2 mM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), antimicrobial reagent primocin (100 μg/ml; InvivoGen, Toulouse, France), bFGF (10 ng/ml), and EGF (30 ng/ml); both were purchased from PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, United States. The cells were cultured as neurospheres, at 37°C and 5% CO

2. After 7 days, the neurospheres were collected and centrifuged. The supernatant was discarded, and 1 ml of trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United StatesA) was added to the pellet. After 3 min of trypsin incubation, 1 ml of trypsin inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) was added to the mix. The suspension was then centrifuged at 1,020 ×

g for 3 minutes and plated onto ZnO nanorods and poly-L-lysine-coated (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) coverslips (control surface) at a cell density of 6 x 10

4 per surface. The cells were cultured in a differentiation medium with same composition as the proliferation medium, but devoid of EGF and with a twofold (20 ng/ml) concentration of bFGF. Cultures were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO

2, with medium exchange on every third day. After 7 days of

in vitro differentiation, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution and stained for the astrocytic marker GFAP (mouse anti-GFAP (1:300; coupled to Alexa 488, Ebioscience, San Diego, CA) and DAPI, to visualize cell nuclei; the coverslips were incubated with 300 nM 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature. Notably, immunostaining for GFAP at day 7

in vitro does not conflict with the initial GFAP–eGFP signal, since the eGFP synthesized at day 0 undergoes proteasomal degradation (t₁/₂ ≈ 6–7 h) and is further diluted by successive mitotic divisions, leaving minimal residual fluorescence afte 7 days in culture

[27].

Finally, the coverslips were mounted using Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences Inc., Eppelheim, Germany).

Recording Setup and Procedure

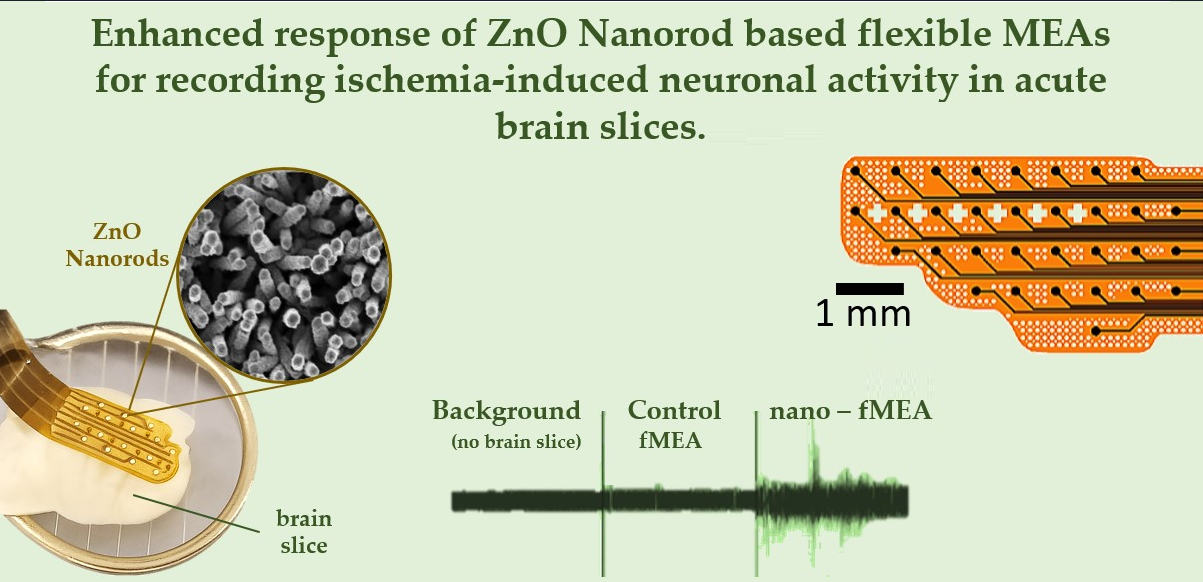

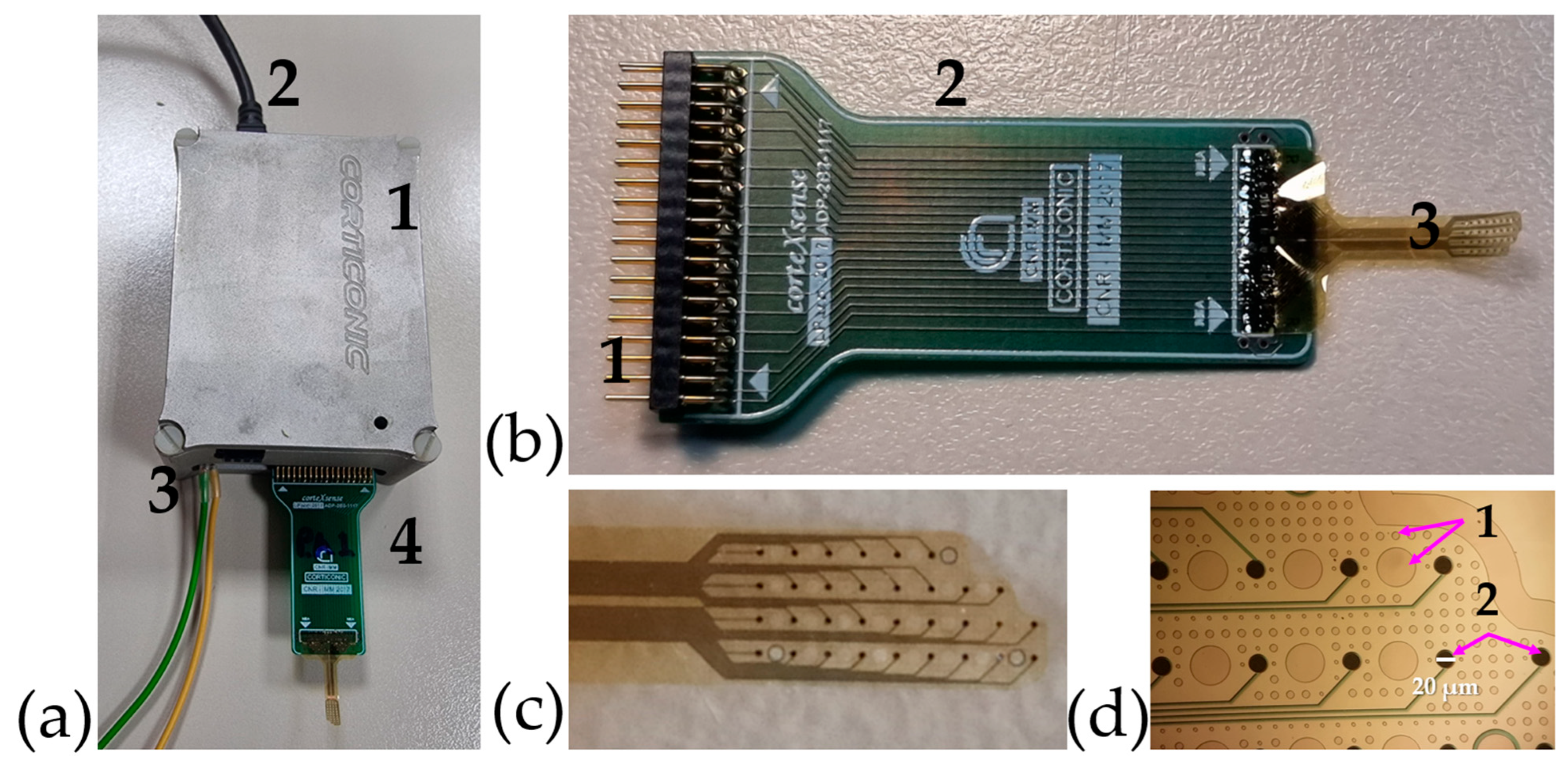

The signal acquisition setup is depicted in

Figure 1a. Recordings were conducted in a 5 cm plastic perfusion chamber. To facilitate handling, a 0.5 cm agar gel layer was affixed within the chamber, serving as a support for the brain slice. The brain slice was placed on top of the agar, and the MEA was precisely positioned using an electronic micromanipulator-controlled system (Luigs & Neumann, Ratingen, Germany), which enabled fine, controlled movements of the electrode.

Once the fMEA was in contact with the brain slice, it was secured using a non-conductive horseshoe-shaped anchor. A platinum filament served as the reference electrode and was submerged in the aCSF. To minimize external interference, the entire system was enclosed within a Faraday cage. The small-scale dimensions of MEA are shown in

Figure 1b.

3. Results

3.1. Nanostructure Morphology and Characterization

The ZnO NRs synthesized via chemical bath deposition form a dense, homogeneous, and randomly oriented nanostructured surface. As shown in

Figure 2, the ZnO NRs exhibit a hexagonal wurtzite crystal structure. By restricting the synthesis time to 1 hour, the resulting nanorods reach lengths of 600–900 nm with thickness ranging from 100 to 150 nm.

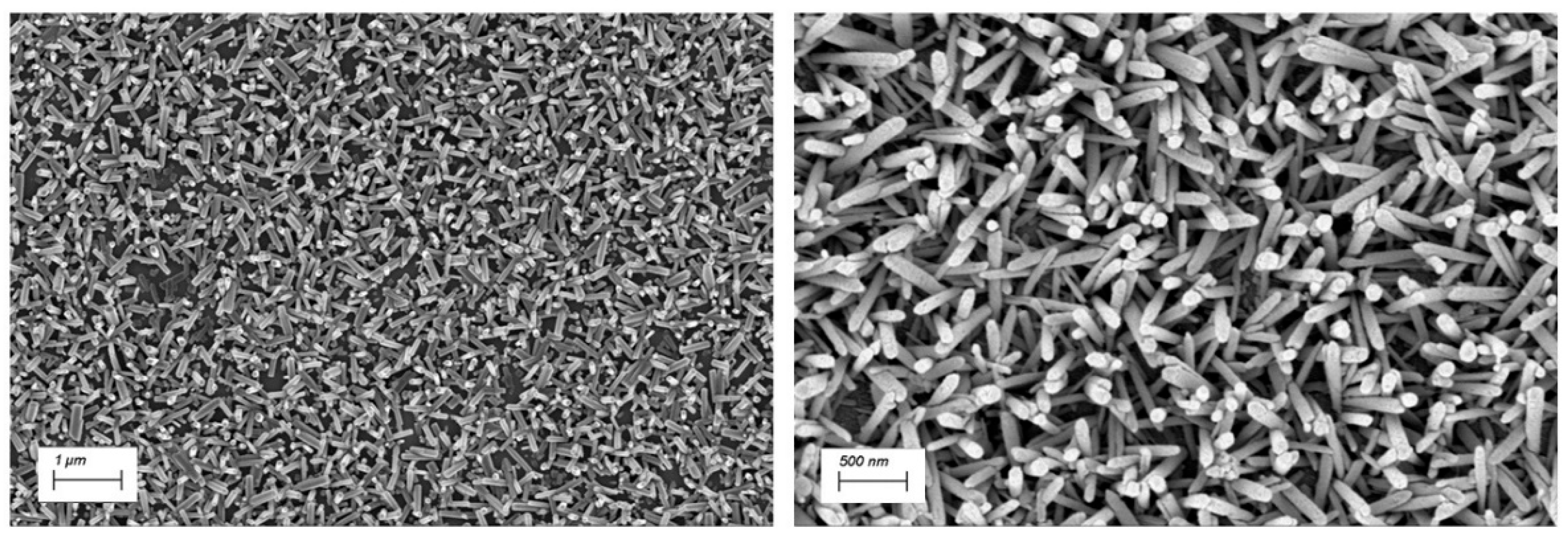

3.2. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

The viscoelastic properties of polymeric substrates intended for neural implants are critical to their functional performance. These materials must endure physiological oscillatory stresses, particularly within the linear viscoelastic region (LVR), to ensure mechanical stability and long-term functionality. This is especially relevant for bioelectronic interfaces implanted in the brain, where mechanical mismatch between the implant and neural tissue can lead to inflammation and signal degradation.

The preliminary strain sweep conducted at 40°C, a temperature chosen to approximate the internal environment of a rodent brain, identified the LVR of the nano-fMEAs. The material exhibited a linear stress–strain relationship up to a strain amplitude of approximately 0.2%, with the storage modulus (E′) remaining constant throughout this range. This confirms the elastic behavior of the material under small deformations, which is essential for minimizing mechanical damage to surrounding neural tissue during implantation and operation.

To simulate physiological loading conditions, a frequency sweep was performed between 1 and 10 Hz—reflecting the frequency range of cardiovascular pulsations

[28] (e.g., heartbeat-induced micromotions) that the implanted device would experience. As shown in

Figure 3a, the storage modulus (E′), loss modulus (E″), and damping factor (tan δ) are reported as a function of frequency. As expected, E′ was consistently higher than E″ across the entire range, indicating a predominantly elastic response. The low values of tan δ suggest minimal energy dissipation, which supports the mechanical stability of the device during cyclic loading.

Temperature-dependent DMA analysis further evaluated the thermal-mechanical behavior of the coated polyimide films. As shown in

Figure 3b, E′, E″, and tan δ were monitored over a temperature range from 50 to 550°C. The glass transition temperature (Tg) was identified at around 360°C from the peak in the loss modulus and tan δ curves. This transition marks the point where the polymer begins to exhibit more rubber-like behavior, and understanding it is crucial for defining the upper operational temperature of the electrode structure. From these analyses it is evident that the material is very stable and suitable for the intended application.

3.3. Thermal Characterization

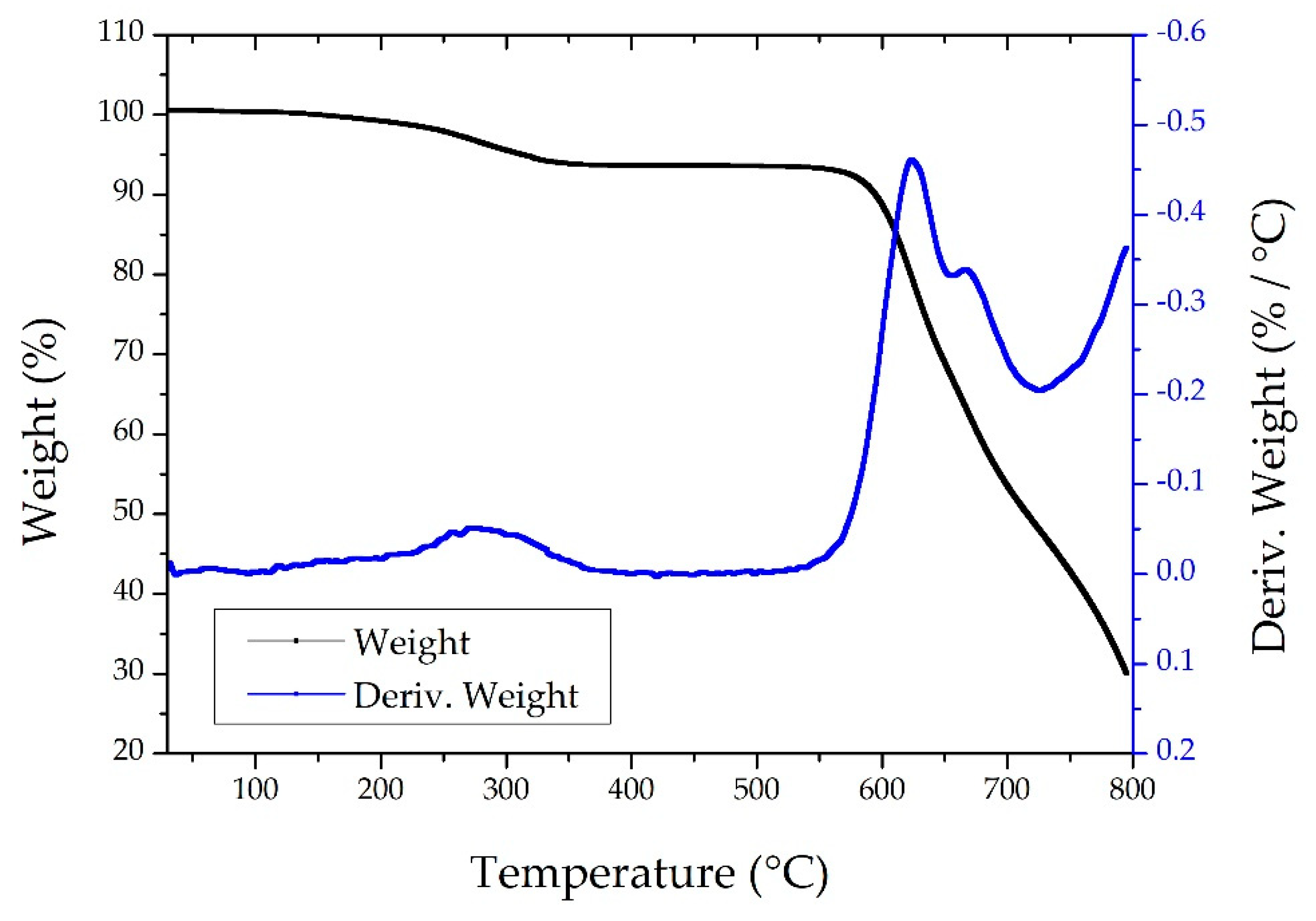

The results from the TGA are reported in

Figure 4. The analysis revealed a three-stage degradation profile for the polyimide-based samples incorporating ZnO nanostructures and metallic coatings. The first notable weight loss occurred around 250°C, likely due to the degradation of low-molecular-weight species, such as residual solvents, unreacted monomers, or curing agents from the polyimide synthesis. Additionally, organic molecules or surface stabilizers adhered to the ZnO nanostructures may also contribute to this initial mass loss.

The primary degradation step was observed near 620°C, corresponding to the thermal decomposition of the polyimide backbone, including chain scission and the breakdown of aromatic and imide groups. A secondary peak around 670°C may be attributed to the delayed degradation of residual polyimide layers, particularly in encapsulated or metal-adjacent regions where reduced heat transfer slows decomposition.

At 800°C, approximately 30% of the sample mass remained, attributable to the presence of thermally stable ZnO nanostructures and inorganic residues from titanium and gold coatings, which remain undecomposed under inert conditions.

These results confirm the thermal robustness of the multilayered polyimide device, supporting the material suitability for use in chronic implantation, such as for in vivo electrophysiological monitoring in rodent brain tissue.

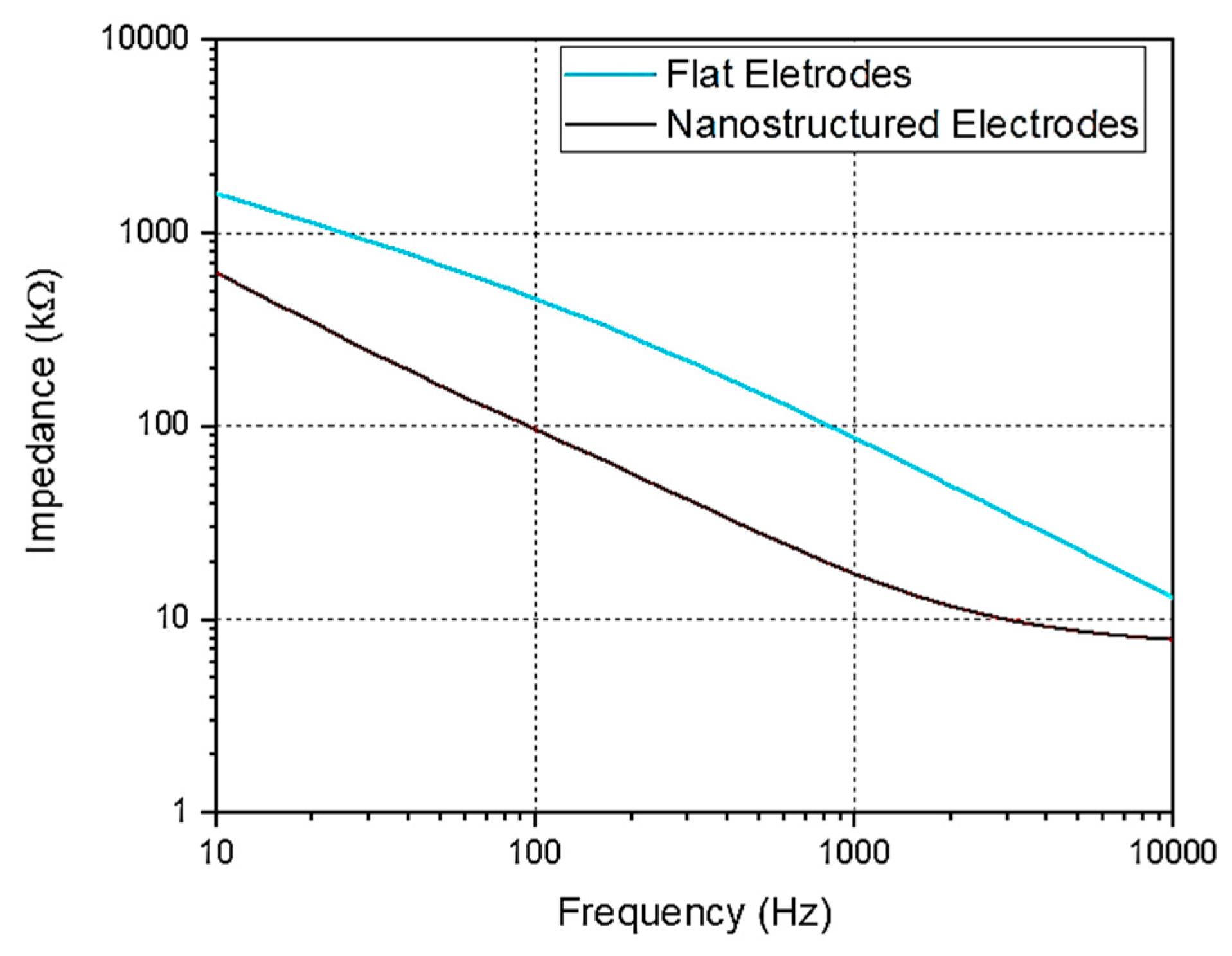

3.4. Electric Characterization

The primary objective of developing nanostructured MEAs is to enhance electrode performance by increasing the electrode’s surface area and therefore reducing impedance values. The EIS measurements were carried out to evaluate electrode performance. The results, shown in

Figure 5, demonstrate a significant impedance reduction at low frequencies. At 1 kHz, flat electrodes exhibited an impedance of 89± 3 kΩ, whereas nano-fMEAs demonstrated a reduced impedance of 17 ± 2 kΩ, representing an ~80% improvement.

These findings are aligned with impedance values obtained for other nanostructured electrodes of rigid recording platforms (i.e. ZnO NRs growth on glass substrates), validating that the improvements are maintained also on flexible MEAs configurations.

3.5. Device Design

The fabrication techniques used result in an ultra-thin fMEA. By using polyimide as both substrate and passivation layer, the resulting MEA is just over 8 µm thick, while maintaining conformability.

Details of the complete recording device and its components can be seen in

Figure 6a,b. The fMEA presents two key features aimed at enhancing its functionality. Firstly, it features an asymmetric design, as illustrated in

Figure 6c, which allows for fabrication in both left- and right-oriented configurations. This design choice enhances the device's versatility. While this study focuses on the use of fMEA for

ex vivo slices, its asymmetric structure has the potential to support

in vivo testing by covering an entire hemisphere in most laboratory rodents. Additionally, the design includes open holes, as shown in

Figure 6d, which facilitate oxygenation of the slice and improve surface adhesion.

3.6. Assessment of Nano-fMEA Biocompatibility in Neural Cells

To further confirm the biocompatibility of ZnO nanostructures with neural cells, overall cell fitness and attachment were evaluated by seeding NS/PCs onto ZnO substrates. After 7 days of

in vitro culture, the samples were fixed and stained for the reactive astrocytic marker GFAP and the nuclear marker DAPI. Although astrocytes on the ZnO nanorods initially appeared smaller and more rounded than those on control surfaces—indicating a modest early attachment challenge—they nonetheless proliferated and achieved a differentiated morphology by day 7 (

Figure 7.), confirming that the ZnO substrates support neural tissue compatibility.

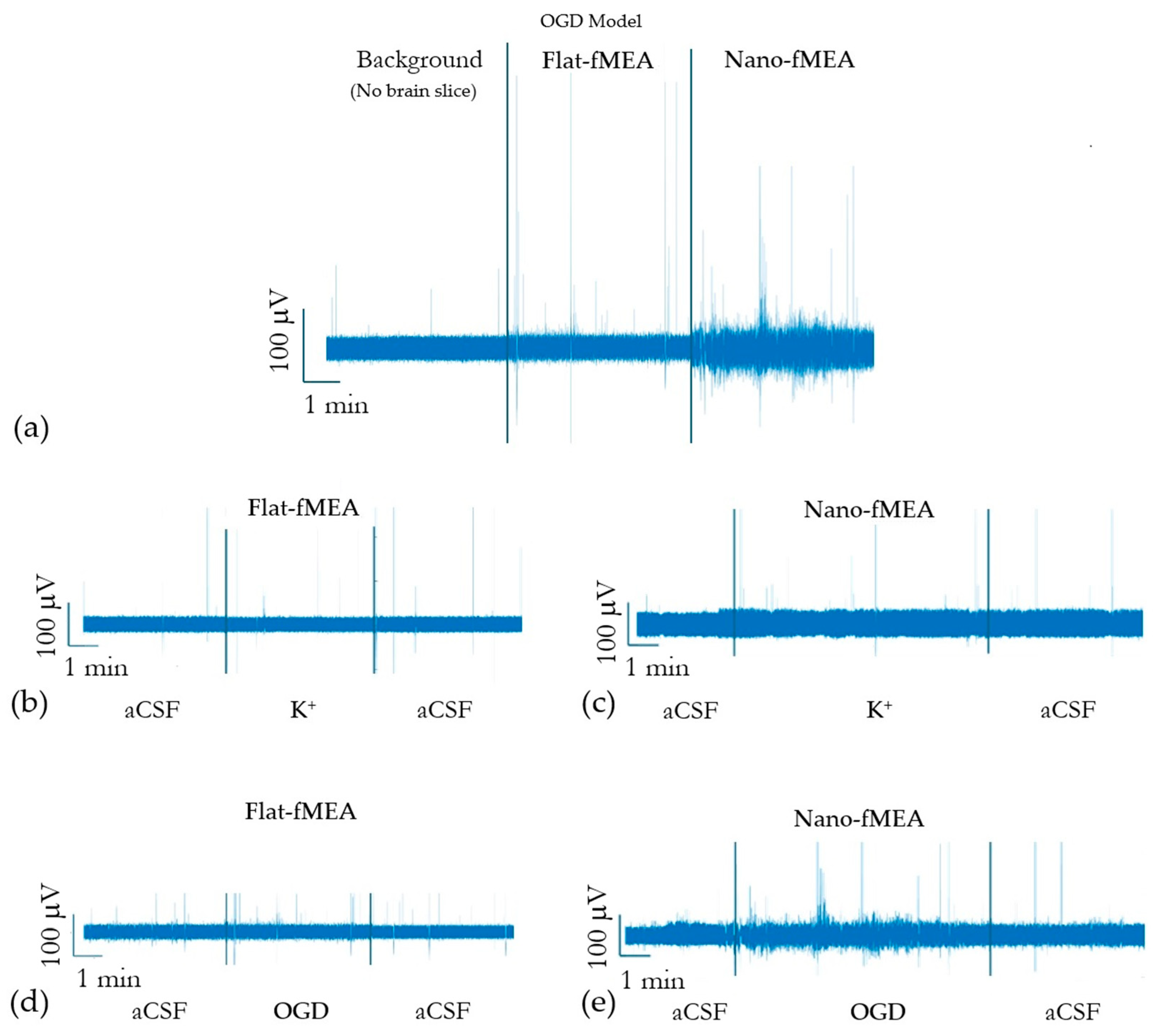

3.7. Signal Acquisition with Nano-fMEAs in Acute Brain Slices

While in vitro cultures of neural cells were employed for assessing nano-fMEA biocompatibility at the single-cell level, they lack the complex three-dimensional architecture, synaptic connectivity and extracellular matrix of intact tissue. To capture these features, we therefore turned to acute brain slices: ex vivo MEA recordings preserve the native cellular microenvironment and local network connectivity, enabling detection of spontaneous and evoked neuronal activity under near-physiological conditions. However, signal acquisition in acute slices poses additional challenges—such as restricted tissue viability, lower cell density at the electrode interface, and increased impedance—compared with in vivo testing. Therefore, network activity is present as weaker signals of lower amplitude. Weaker signals, in addition to a higher sensitivity of cortical slices to changes in the environment, result from recording conditions that are more sensitive to noise. Therefore, noise is evaluated for both fMEA and nano-fMEAs. When using the nano-fMEAs system, noise was significantly reduced, with a root-mean-square (RMS) noise level of ~30 µV, compared to ~65 µV for fMEAs (that use flat electrodes).

Stimulation with experimental solutions (hyperkalemia and OGD) was used to evaluate the influence of ZnO NRs on the recording capacities of the fMEA. While both fMEA designs detected activity, the nano-fMEA design exhibited significantly improved signal acquisition.

Figure 8.a showcases the difference in signal detection between the two MEA designs in the OGD model, disclosing increased signal acquisition when recording with nano-fMEA (raw data).

In the hyperkalemic model, where elevated extracellular potassium induces neuronal depolarization and increases spontaneous activity, the nano-fMEA demonstrated a higher event detection rate compared to conventional MEAs, capturing a greater number of spike occurrences with improved signal clarity as can be seen in (

Figure 8.b, c). This enhanced sensitivity can be attributed to the optimized electrode-tissue interface, which reduces impedance and improves charge transfer. The advantage of the nano-fMEA became even more pronounced in the OGD model, which simulates ischemic conditions by depriving tissue of oxygen and glucose, leading to metabolic stress and altered neural firing patterns. Under these conditions, the nano-fMEA not only recorded a significantly greater number of events than its rigid counterparts but also detected subtle fluctuations in neural activity that were otherwise undetected, as shown in (

Figure 8.d, e). The increased difference in event detection during OGD suggests that the nano-fMEA is particularly suited for capturing weak or transient signals, likely due to its conformal contact and enhanced electrode properties. These findings highlight the potential of nano-fMEAs for studying pathological neural dynamics with greater precision, especially in ischemic models and metabolic stress. As shown in

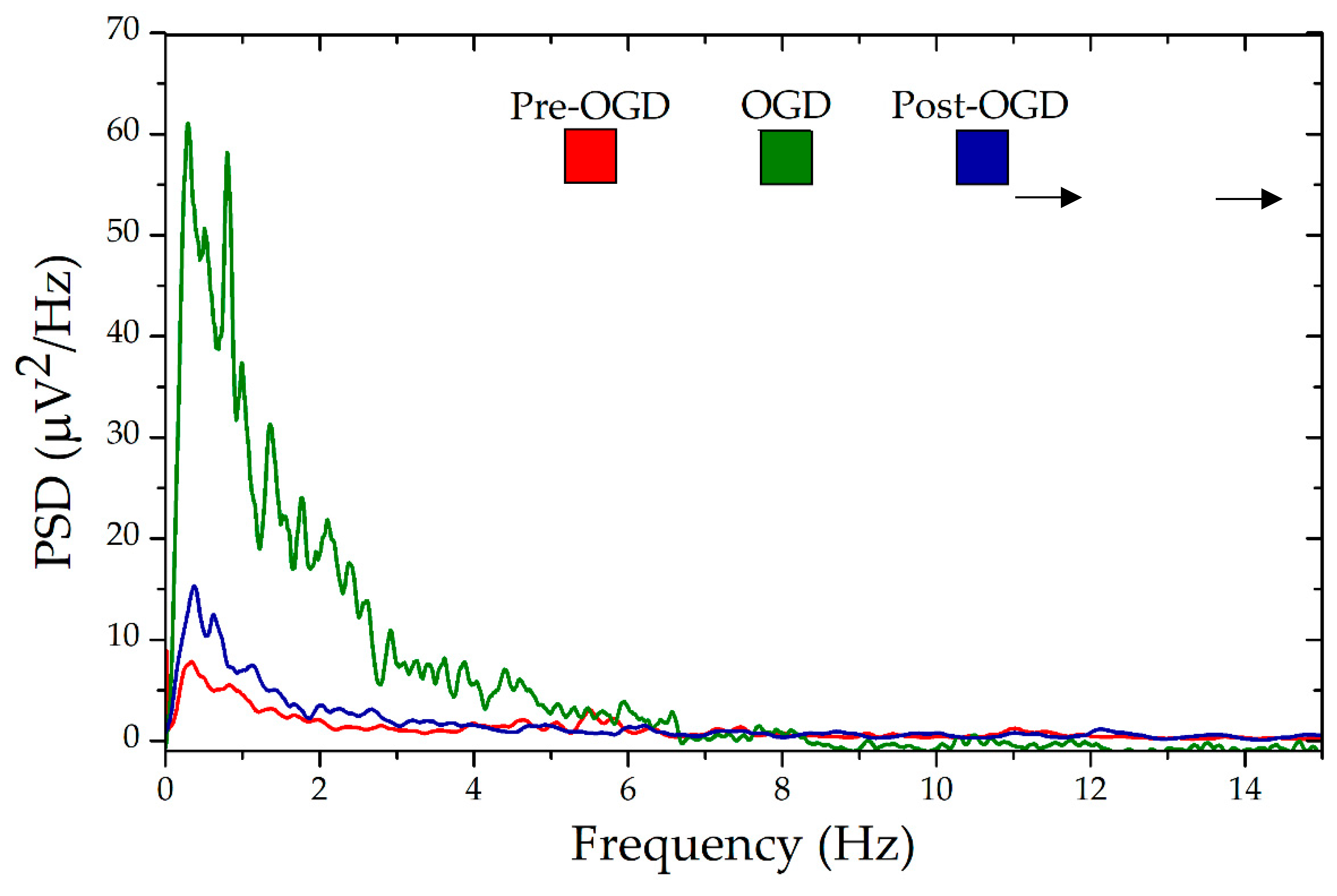

Figure 9, the power spectral density (PSD) recorded in the three different phases of the OGD protocol, clearly highlighted the increase of the neural activity during the deprivation period and a similar, reduced activity between the Pre-OGD and Post-OGD phases. Similar behavior was observed during hyperkalemia (not shown), highlighting the superior properties of the nano-fMEA in capturing these signals in respect to flat devices.

4. Discussion

The fabrication of the nano-fMEAs and the realization of portable electronics for signal recording represent a bioengineering system specifically designed for the investigation of brain activity in vitro and ex vivo. The usage of ZnO disordered nanostructures offers multiple advantages related to the reduction of the impedance of the electrodes (up to 80% lower than flat electrodes at 1 kHz for a fixed area), the low growth temperature (85°C) and good uniformity of nanostructures (up to 6’’) that make the material compatible with ultra-thin flexible substrates, and the good biocompatibility. The nano-fMEA grid has been designed with a high number of holes (up to 50% of the whole area) for facilitating the passage of the nutrients and oxygen into the brain tissue during the experiments to maintain good conditions in vitro and ex vivo before and after the deprivation period, and also favoring the diffusion of the experimental solutions to better mimic ischemic conditions in the whole volume of the brain slice.

In this study, we demonstrated that Nano-fMEAs exhibit enhanced detection sensitivity compared to traditional flat MEAs in capturing both rapid and subtle electrophysiological responses during OGD and hyperkalemia.

Firstly, Nano-fMEA biocompatibility was tested

in vitro, culturing NS/PC-derived astrocytes on ZnO and control substrates. NS/PCs were chosen for their capacity to proliferate, their adaptability to a range of surfaces and their retained ability to differentiate into various neural cell types upon exposure to differentiation medium- features that make them an ideal model for biocompatibility testing

[29]. Among other neural cells, astrocytes were selected as a representative cell type to evaluate ZnO substrates' biocompatibility. Under optimal conditions astrocytes develop a characteristic branched morphology; conversely when growth conditions are suboptimal, they assume a rounded, less differentiated shape

[30]. This morphological shift, which can be clearly visualized through staining, serves as a reliable indicator of surfaces' biocompatibility. As shown in

Figure 7, astrocytes differentiation remained robust: by day 7

in vitro, cells on ZnO nanostructures exhibited healthy, mature branching comparable to those on polylysine-coated controls or on other peculiar nanostructures such as silicon nanowires

[31]. These findings prove no significant cytotoxicity and stable electrode–tissue coupling of Nano-fMEAs, supporting their suitability for long-term neuroelectronic interfaces.

Secondly,

ex vivo extracellular recordings on Nano-fMEA were performed. In our setup, brain slices were exposed to OGD for 5 minutes, which was sufficient to elicit hallmark ischemic responses

[32,33], including rapid ATP depletion, massive glutamate release, membrane depolarization and collapse of ionic gradients

[34]. In addition, hyperkalemia was used to induce ionic imbalance and elicit SDs

[35]. In the healthy brain, extracellular K⁺ levels typically range between 2.5 and 3.5 mM; during ischemia, this concentration rises dramatically, reaching 10–12 mM in the early phase (within 2 minutes), and exceeding 80 mM in the later phase

[36,37]. Our protocol mimics the early ischemic phase, wherein neuronal recovery is expected upon return to normal conditions. Both OGD and hyperkalemia serve as complementary models to study ischemia-related mechanisms in brain slices, enabling detailed investigation of ion dynamics and cellular responses under ischemic stress.

Overall, our comparative recordings revealed that nano-fMEAs outperform conventional flat MEAs in both models, detecting a greater number of high and low-amplitude events. Due to the intrinsic limitations of acute brain slices, including reduced neuronal density and disrupted network connectivity, spontaneous activity tends to be sparse and inconsistent

[38,39]. This likely explains the low frequency of events during pre- and post-stimulation phases. Nevertheless, nano-fMEAs consistently captured more of those pre- and post-stimulation events, underscoring their superior sensitivity when compared to regular flat-fMEAs (

Figure 8).

Moreover, during the 5 minutes of OGD stimulation, events frequency rose markedly. Conversely, hyperkalemic stimulation evoked fewer, more transient events. These results are consistent with the different severity of the applied stimuli: hyperkalemia increases neuronal excitability by depolarizing membranes but does not compromise cellular metabolism and generally does not elicit strong glial response

[40,41]. OGD instead, by depriving tissue of oxygen and glucose, induces broader ionic disturbances, metabolic stress, and glial activation, resulting in more complex and sustained cascade of responses

[42]. Thus, the higher signal activity observed during OGD reflects its stronger and more disruptive insult (

Figure 8.). Interestingly, OGD stimulation allowed recording of more subtle fluctuations in neural activity, likely representing a mixture of subthreshold neuronal signals and glial activity. Under ischemic stress, many neurons depolarize yet fail to reach spike threshold, generating low-amplitude excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials that are normally buried in the background noise. Simultaneously, activated astrocytes produce slow, small-voltage field potentials through potassium buffering, gliotransmitter release, and calcium waves

[43,44]. The ZnO nanorod coating on the nano-fMEA lowers electrode impedance and increases the slice-electrode contact area, boosting sensitivity particularly to these low-amplitude, low-frequency events that standard flat MEAs are not able to detect. Finally, PSD analysis also confirmed increased neural responses during OGD and proved that the events are stimulus-driven: spectral power rose significantly during the 5-minute stimulation phase and returned to baseline afterwards, ruling out recording artifacts (

Figure 9.).

Taken together, our findings establish nano-fMEAs as a potential tool to detect the complex interplay of neuronal and glial dynamics under metabolic and excitotoxic stress. Their high sensitivity to subtle, transient events and improved biocompatibility make them ideally suited for studies of ischemia-related pathologies in brain-slice models. Future work will aim to integrate targeted chemical blockers to causally attribute recorded signals to neurons and glial cells, and to extend these platforms toward chronic, in vivo applications.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we successfully fabricated, characterized and evaluated the performance of nano-fMEAs for the detection of ischemia-induced neural activity in acute brain slices. Our findings demonstrate that the incorporation of ZnO nanostructures significantly enhances electrode sensitivity, particularly in reducing impedance and improving signal clarity. These advancements address key limitations of traditional flat MEAs by increasing sensitivity and maintaining conformability to biological tissues, which is critical for both acute and potential chronic applications.

The nanostructured design of our nano-fMEAs resulted in an 80% reduction in impedance at 1 kHz, compared to flat electrodes, which is consistent with previously reported improvements in nanostructured electrodes used in rigid platforms. This reduction in impedance facilitates more accurate electrophysiological recordings, particularly in challenging ex vivo environments where signal amplitude is lower than in vivo conditions. Additionally, our design improvements, including asymmetric electrode configurations and oxygenation holes, enhance both adaptability and functionality, ensuring more efficient interaction with brain tissue.

Through ex vivo recordings of ischemia models using both OGD and hyperkalemic stimulation, we validated the capability of nano-fMEAs to detect ischemia-related ionic disturbances with high fidelity. Our results confirm that nano-fMEAs are effective in capturing neuronal and eventually glial responses to pathological conditions, offering a valuable platform for investigating ischemic mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions.

Overall, this work highlights the potential of nano-fMEAs in advancing neural interface technology. Future research can expand the application of nano-fMEAs from ex vivo to in vivo studies. This new design can pave the way for improved diagnostics and treatment strategies for ischemic brain injury and other neurological disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R.D.V, V.M., M.A. and L.Ma.; methodology, D.R.D.V, V.M, I.L., E.P.; software, D.P and L.Mo; validation, D.R.D.V, V.M., J.K.. and F.M.; formal analysis, F.M., L. Ma; investigation, D.R.D.V, V.M., I.L. E.L., E.P. and L.Mo; resources, M.A. and L.Ma ; data curation, F.M. and D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R.D.V, V.M., E.P., L.Ma; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, J.K., J.T. and M.A..; supervision, M.A. and L. Ma.; funding acquisition, M.A. and L.Ma. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been partially supported from the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Innovative Training Network under grant agreement n◦ 956325 (Astrotech), funded by the European Community’s Framework program Horizon 2020 and Meta-Brain project funded by the European Union under grant agreement n◦ 101130650. This study was also funded by the Czech Science Foundation under grant agreement n◦ 23-06269S, by the Czech Academy of Sciences (Strategy AV21) under grant agreement n◦ VP29, and by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (Financed by EU—Next Generation EU) under grant agreement n◦ LX22NPO5107. Fluorescence microscopy was done at the Microscopy Service Center of the Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Czech Academy of Sciences, supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (Czech-Bioimaging) under grant agreement n◦ LM2023050.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tomas Knotek for his help and useful insights and comments regarding the in-situ experiments in brain slices, and Helena Pavlikova for her technical assistance.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MEAs |

Microelectrode arrays |

| fMEAs |

flexible MEAs |

| nano-fMEAs |

nanostructured flexible MEAs |

| ZnO NRs |

Zinc Oxide Nanorods |

| SD |

Spreading depolarization |

| OGD |

Oxygen-glucose deprivation |

| PCB |

Printed circuit board |

| DMA |

Dynamic mechanical analysis |

| TGA |

Thermogravimetric analysis |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| EIS |

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| DAPI |

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| GFAP |

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

References

- X. Tang, H. Shen, S. Zhao, N. Li, J. Liu, Flexible brain–computer interfaces, Nat. Electron. 6 (2023) 109–118. [CrossRef]

- T. Someya, Z. Bao, G.G. Malliaras, The rise of plastic bioelectronics, Nature 540 (2016) 379–385. [CrossRef]

- I.R. Minev, P. Musienko, A. Hirsch, Q. Barraud, N. Wenger, E.M. Moraud, J. Gandar, M. Capogrosso, T. Milekovic, L. Asboth, R.F. Torres, N. Vachicouras, Q. Liu, N. Pavlova, S. Duis, A. Larmagnac, J. Vörös, S. Micera, Z. Suo, G. Courtine, S.P. Lacour, Electronic dura mater for long-term multimodal neural interfaces, Science 347 (2015) 159–163. [CrossRef]

- S.P. Lacour, G. Courtine, J. Guck, Materials and technologies for soft implantable neuroprostheses, Nat. Rev. Mater. 1 (2016) 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Z. Fan, J.G. Lu, Zinc Oxide Nanostructures: Synthesis and Properties, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 5 (2005) 1561–1573. [CrossRef]

- A. Rinaldi, M. Pea, A. Notargiacomo, E. Ferrone, S. Garroni, L. Pilloni, R. Araneo, A Simple Ball Milling and Thermal Oxidation Method for Synthesis of ZnO Nanowires Decorated with Cubic ZnO2 Nanoparticles, Nanomaterials 11 (2021) 475. [CrossRef]

- M. Carofiglio, S. Barui, V. Cauda, M. Laurenti, Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Potential Use in Nanomedicine, Appl. Sci. 10 (2020) 5194. [CrossRef]

- M. Maddah, C.P. Unsworth, G.J. Gouws, N.O.V. Plank, Synthesis of encapsulated ZnO nanowires provide low impedance alternatives for microelectrodes, PLOS ONE 17 (2022) e0270164. [CrossRef]

- F. Maita, L. Maiolo, I. Lucarini, I. Del Rio De Vicente, E. Palmieri, E. Fiorentini, V. Mussi, Low cost and label free Raman sensors based on Ag-coated ZnO nanorods for monitoring astronaut’s health, in: 2023 IEEE 10th Int. Workshop Metrol. Aerosp. MetroAeroSpace, 2023: pp. 363–367. [CrossRef]

- D. Sudha, E.R. Kumar, S. Shanjitha, A.M. Munshi, G.A.A. Al-Hazmi, N.M. El-Metwaly, S.J. Kirubavathy, Structural, optical, morphological and electrochemical properties of ZnO and graphene oxide blended ZnO nanocomposites, Ceram. Int. 49 (2023) 7284–7288. [CrossRef]

- J.I. Del Río De Vicente, I. Lucarini, F. Maita, D. Salvò, V. Marchetti, M. Anderova, J. Gómez, L. Maiolo, Development of ZnO NRs-rGO Low-Impedance Electrodes for Astrocyte Cell Signal Recording, in: 2023 IEEE Sens., 2023: pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- M. Wang, G. Mi, D. Shi, N. Bassous, D. Hickey, T.J. Webster, Nanotechnology and Nanomaterials for Improving Neural Interfaces, Adv. Funct. Mater. 28 (2018) 1700905. [CrossRef]

- B.L. Rodilla, A. Arché-Núñez, S. Ruiz-Gómez, A. Domínguez-Bajo, C. Fernández-González, C. Guillén-Colomer, A. González-Mayorga, N. Rodríguez-Díez, J. Camarero, R. Miranda, E. López-Dolado, P. Ocón, M.C. Serrano, L. Pérez, M.T. González, Flexible metallic core–shell nanostructured electrodes for neural interfacing, Sci. Rep. 14 (2024) 3729. [CrossRef]

- E. Saracino, L. Maiolo, D. Polese, M. Semprini, A.I. Borrachero-Conejo, J. Gasparetto, S. Murtagh, M. Sola, L. Tomasi, F. Valle, L. Pazzini, F. Formaggio, M. Chiappalone, S. Hussain, M. Caprini, M. Muccini, L. Ambrosio, G. Fortunato, R. Zamboni, A. Convertino, V. Benfenati, A Glial-Silicon Nanowire Electrode Junction Enabling Differentiation and Noninvasive Recording of Slow Oscillations from Primary Astrocytes, Adv. Biosyst. 4 (2020) 1900264. [CrossRef]

- J. Kriska, Z. Hermanova, T. Knotek, J. Tureckova, M. Anderova, On the Common Journey of Neural Cells through Ischemic Brain Injury and Alzheimer’s Disease, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021) 9689. [CrossRef]

- D. Belov Kirdajova, J. Kriska, J. Tureckova, M. Anderova, Ischemia-Triggered Glutamate Excitotoxicity From the Perspective of Glial Cells, Front. Cell. Neurosci. 14 (2020) 51. [CrossRef]

- Y. Du, W. Wang, A.D. Lutton, C.M. Kiyoshi, B. Ma, A.T. Taylor, J.W. Olesik, D.M. McTigue, C.C. Askwith, M. Zhou, Dissipation of transmembrane potassium gradient is the main cause of cerebral ischemia-induced depolarization in astrocytes and neurons, Exp. Neurol. 303 (2018) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- A. Menyhárt, D. Zölei-Szénási, T. Puskás, P. Makra, O. M. Tóth, B. Szepes, R. Tóth, O. Ivánkovits-Kiss, T. Obrenovitch, F. Bari, E. Farkas, Spreading depolarization remarkably exacerbates ischemia-induced tissue acidosis in the young and aged rat brain, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017). [CrossRef]

- X.-Y. Shen, Z.-K. Gao, Y. Han, M. Yuan, Y.-S. Guo, X. Bi, Activation and Role of Astrocytes in Ischemic Stroke, Front. Cell. Neurosci. 15 (2021) 755955. [CrossRef]

- L. Maiolo, S. Mirabella, F. Maita, A. Alberti, A. Minotti, V. Strano, A. Pecora, Y. Shacham-Diamand, G. Fortunato, Flexible pH sensors based on polysilicon thin film transistors and ZnO nanowalls, Appl. Phys. Lett. 105 (2014) 093501. [CrossRef]

- Luca Maiolo, Vincenzo Guarino, Emanuela Saracino, Annalisa Convertino, Manuela Melucci, Michele Muccini, Luigi Ambrosio, Roberto Zamboni, Valentina Benfenati, Glial Interfaces: Advanced Materials and Devices to Uncover the Role of Astroglial Cells in Brain Function and Dysfunction, Adv. Healthcare Mater., 2021, 10 (1), 2001268. https://advanced.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/adhm.202001268.

- E. Castagnola, L. Maiolo, E. Maggiolini, A. Minotti, M. Marrani, F. Maita, A. Pecora, G.N. Angotzi, A. Ansaldo, M. Boffini, L. Fadiga, G. Fortunato, D. Ricci, PEDOT-CNT-Coated Low-Impedance, Ultra-Flexible, and Brain-Conformable Micro-ECoG Arrays, IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. Publ. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 23 (2015) 342–350. [CrossRef]

- E.G. Barbagiovanni, V. Strano, G. Franzò, I. Crupi, S. Mirabella, Photoluminescence transient study of surface defects in ZnO nanorods grown by chemical bath deposition, Appl. Phys. Lett. 106 (2015) 093108. [CrossRef]

- V. Strano, R.G. Urso, M. Scuderi, K.O. Iwu, F. Simone, E. Ciliberto, C. Spinella, S. Mirabella, Double Role of HMTA in ZnO Nanorods Grown by Chemical Bath Deposition, J. Phys. Chem. C 118 (2014) 28189–28195. [CrossRef]

- Gyu-Chul Yi, Chunrui Wang and Won Il Park, ZnO nanorods: synthesis, characterization and applications, Semicond. Sci. Technol. 20 (2005) S22–S34. [CrossRef]

- L. Pazzini, D. Polese, J.F. Weinert, L. Maiolo, F. Maita, M. Marrani, A. Pecora, M.V. Sanchez-Vives, G. Fortunato, An ultra-compact integrated system for brain activity recording and stimulation validated over cortical slow oscillations in vivo and in vitro, Sci. Rep. 8 (2018) 16717. [CrossRef]

- Corish, P., & Tyler-Smith, C. (1999). Attenuation of green fluorescent protein half-life in mammalian cells. Protein engineering, 12(12), 1035–1040. https://doi-org.d360prx.biomed.cas.cz/10.1093/protein/12.12.1035.

- P.M.L. Janssen, B.J. Biesiadecki, M.T. Ziolo, J.P. Davis, The Need for Speed; Mice, Men, and Myocardial Kinetic Reserve, Circ. Res. 119 (2016) 418–421. [CrossRef]

- Vonk, W. I. M., Rainbolt, T. K., Dolan, P. T., Webb, A. E., Brunet, A., & Frydman, J. (2020). Differentiation Drives Widespread Rewiring of the Neural Stem Cell Chaperone Network. Molecular cell, 78(2), 329–345.e9. [CrossRef]

- C Benincasa, J., Madias, M. I., Kandell, R. M., Delgado-Garcia, L. M., Engler, A. J., Kwon, E. J., & Porcionatto, M. A. (2024). Mechanobiological Modulation of In Vitro Astrocyte Reactivity Using Variable Gel Stiffness. ACS biomaterials science & engineering, 10(7), 4279–4296. [CrossRef]

- Lucarini, F. Maita, G. Conte, E. Saracino, F. Formaggio, E.Palmieri, R. Fabbri, A. Konstantoulaki, C. Lazzarini, M. Caprini, V. Benfenati, L. Maiolo and A.Convertino, Silicon Nanowire Mats Enable Advanced Bioelectrical Recordings in Primary DRG Cell Cultures, Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2025, 2500379. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, I., & Andrew, R. D. (2001). Imaging anoxic depolarization during ischemia-like conditions in the mouse hemi-brain slice. Journal of neurophysiology, 85(1), 414–424. [CrossRef]

- C.P. Taylor, M.L. Weber, C.L. Gaughan, E.J. Lehning, R.M. LoPachin, Oxygen/glucose deprivation in hippocampal slices: altered intraneuronal elemental composition predicts structural and functional damage, J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 19 (1999) 619–629. [CrossRef]

- Reappraisal of anoxic spreading depolarization as a terminal event during oxygen–glucose deprivation in brain slices in vitro Scientific Reports, (n.d.). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-75975-w (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- A.P. Antunes, A.J. Schiefecker, R. Beer, B. Pfausler, F. Sohm, M. Fischer, A. Dietmann, P. Lackner, W.O. Hackl, J.-P. Ndayisaba, C. Thomé, E. Schmutzhard, R. Helbok, Higher brain extracellular potassium is associated with brain metabolic distress and poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 18 (2014) R119. [CrossRef]

- Hansen A. J. (1978). The extracellular potassium concentration in brain cortex following ischemia in hypo- and hyperglycemic rats. Acta physiologica Scandinavica, 102(3), 324–329. [CrossRef]

- Somjen G., G. (1979). Extracellular potassium in the mammalian central nervous system. Annual review of physiology, 41, 159–177. https://doi-org.d360prx.biomed.cas.cz/10.1146/annurev.ph.41.030179.

- Blaeser AS, Connors BW, Nurmikko AV. Spontaneous dynamics of neural networks in deep layers of prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2017;117(4):1581-1594. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt SL, Chew EY, Bennett DV, Hammad MA, Fröhlich F. Differential effects of cholinergic and noradrenergic neuromodulation on spontaneous cortical network dynamics. Neuropharmacology. 2013;72:259-273. [CrossRef]

- Walch, E., Murphy, T. R., Cuvelier, N., Aldoghmi, M., Morozova, C., Donohue, J., Young, G., Samant, A., Garcia, S., Alvarez, C., Bilas, A., Davila, D., Binder, D. K., & Fiacco, T. A. (2020). Astrocyte-Selective Volume Increase in Elevated Extracellular Potassium Conditions Is Mediated by the Na+/K+ ATPase and Occurs Independently of Aquaporin 4. ASN neuro, 12, 1759091420967152. [CrossRef]

- Ding, F., Sun, Q., Long, C., Rasmussen, R. N., Peng, S., Xu, Q., Kang, N., Song, W., Weikop, P., Goldman, S. A., & Nedergaard, M. (2024). Dysregulation of extracellular potassium distinguishes healthy ageing from neurodegeneration. Brain : a journal of neurology, 147(5), 1726–1739. [CrossRef]

- Xie, M., Wang, W., Kimelberg, H. K., & Zhou, M. (2008). Oxygen and glucose deprivation-induced changes in astrocyte membrane potential and their underlying mechanisms in acute rat hippocampal slices. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 28(3), 456–467. [CrossRef]

- Mestre ALG, Inácio PMC, Elamine Y, et al. Extracellular Electrophysiological Measurements of Cooperative Signals in Astrocytes Populations. Front Neural Circuits. 2017;11:80. Published 2017 Oct 23. [CrossRef]

- Chiang CC, Durand DM. Subthreshold Oscillating Waves in Neural Tissue Propagate by Volume Conduction and Generate Interference. Brain Sci. 2022;13(1):74. Published 2022 Dec 30. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) Recording Setup; (b) Size comparison of flexible MEA.

Figure 1.

(a) Recording Setup; (b) Size comparison of flexible MEA.

Figure 2.

SEM images of Zinc Oxide Nanorods (ZnO NRs) at two different magnifications.

Figure 2.

SEM images of Zinc Oxide Nanorods (ZnO NRs) at two different magnifications.

Figure 3.

DMA characterization of nano-fMEA: (a) Frequency sweep, performed at 40°C; (b) Temperature sweep, perfomed at 1 Hz.

Figure 3.

DMA characterization of nano-fMEA: (a) Frequency sweep, performed at 40°C; (b) Temperature sweep, perfomed at 1 Hz.

Figure 4.

TGA analysis of nano-fMEA under a nitrogen atmosphere. The black curve shows the weight loss as a function of temperature, while the blue curve represents the derivative of the weight loss, indicating the rate of decomposition with respect to temperature.

Figure 4.

TGA analysis of nano-fMEA under a nitrogen atmosphere. The black curve shows the weight loss as a function of temperature, while the blue curve represents the derivative of the weight loss, indicating the rate of decomposition with respect to temperature.

Figure 5.

EIS of nanostructured and flat flexible electrodes.

Figure 5.

EIS of nanostructured and flat flexible electrodes.

Figure 6.

Nano-fMEA and its components. (a) Custom-made system developed at CNR-IMM with: (a1) Acquisition board, (a2) Connection to computer and energy source, (a3) Grounding and (a4) fMEA; (b) fMEA with: (b1) Pins to interface with the system, (b2) custom-made PCB adaptor and (b3) polyimide based grid; (c) fMEA highlighting its asymmetric design which is tailored for recordings on the slice or wrapped around it; (d) Zoom in of the nano-fMEA which highlights: (d1) the open holes which allow oxygenation and (d2) the nanostructured recording pads, with a size of 20 µm.

Figure 6.

Nano-fMEA and its components. (a) Custom-made system developed at CNR-IMM with: (a1) Acquisition board, (a2) Connection to computer and energy source, (a3) Grounding and (a4) fMEA; (b) fMEA with: (b1) Pins to interface with the system, (b2) custom-made PCB adaptor and (b3) polyimide based grid; (c) fMEA highlighting its asymmetric design which is tailored for recordings on the slice or wrapped around it; (d) Zoom in of the nano-fMEA which highlights: (d1) the open holes which allow oxygenation and (d2) the nanostructured recording pads, with a size of 20 µm.

Figure 7.

Example of a qualitative acquisition of NS/PCs-derived astrocytes grown on control, polylysine-coated, surfaces (left) and on ZnO surfaces (right) for 7 days in in vitro conditions; astrocytes are visualized in green (GFAP) and cell nuclei are in blue (DAPI). GFAP, Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Figure 7.

Example of a qualitative acquisition of NS/PCs-derived astrocytes grown on control, polylysine-coated, surfaces (left) and on ZnO surfaces (right) for 7 days in in vitro conditions; astrocytes are visualized in green (GFAP) and cell nuclei are in blue (DAPI). GFAP, Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Figure 8.

(a) Comparison of activity detection between a traditional flat flexible grid (Flat-fMEA) and the nanostructured flexible MEA (Nano-fMEA) compared to the background noise in OGD conditions; Recording of hyperkalemic stimulation using (b) Flat-fMEA and (c) Nano-fMEA; Recording of OGD model using (d) Flat-fMEA and (e) Nano-fMEA.

Figure 8.

(a) Comparison of activity detection between a traditional flat flexible grid (Flat-fMEA) and the nanostructured flexible MEA (Nano-fMEA) compared to the background noise in OGD conditions; Recording of hyperkalemic stimulation using (b) Flat-fMEA and (c) Nano-fMEA; Recording of OGD model using (d) Flat-fMEA and (e) Nano-fMEA.

Figure 9.

Power Spectral Density (PSD) obtained with nano-fMEAs during the OGD protocol. As expected, brain activity increases due to oxygen and glucose deprivation and then it returns to the starting levels.

Figure 9.

Power Spectral Density (PSD) obtained with nano-fMEAs during the OGD protocol. As expected, brain activity increases due to oxygen and glucose deprivation and then it returns to the starting levels.

Table 1.

Composition of the solutions used.

Table 1.

Composition of the solutions used.

| Compounds |

aCSF (mM) |

Isolation solution

(mM) |

Hyperkalemic (mM) |

OGD (mM) |

| NaCl |

122 |

- |

115 |

122 |

| NMDG |

- |

110 |

- |

- |

| KCl |

3 |

2.5 |

10 |

3 |

| NaHCO3 |

28 |

24.5 |

28 |

28 |

| Na2HPO4 |

1.25 |

1.25 |

1.25 |

1.25 |

| Glucose |

10 |

20 |

10 |

- |

| CaCl2 |

1.5 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

| MgCl2 |

1.3 |

7 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).