Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Fundamental Challenges in Modern Physics

1.2. The Emergence of the Information Paradigm and the Need for a New Approach

1.3. Proposal of Structural Information Cosmology (SIC)

1.4. Purpose and Scope of the Paper

2. Core Assumptions and Framework of SIC

2.1. Introduction of the Structural Information Field and Basic Assumptions

2.2. Construction of the SIC Lagrangian

- −

- : As the structural information becomes more complex (i.e., as the value of increases), the response to spacetime curvature changes, potentially leading to an effect of weakened effective gravity.

- −

- : As the structural information becomes more complex, it could lead to an effect of strengthened effective gravity.

- −

- : The direct non-minimal coupling between the information field and gravitational curvature vanishes, approaching standard minimally coupled gravity.

- −

- Coupling Constant : This constant determines the dynamical characteristics of the information structure. The sign and magnitude of significantly influence the stability of the information structure dynamics (e.g., the appearance of ghost states) and the propagation characteristics of its perturbations, which requires detailed analysis in future work.

- −

- : The higher-order kinetic term (of the form) for the field vanishes. If a standard kinetic term (of the form ) is not included in this Lagrangian, this could mean that the field might lack dynamical degrees of freedom. Self-interaction due to would still exist.

- −

2.3. Theoretical Justification for Parameter Introduction

- Generality and Systematic Construction of the Theory: When systematically considering physically possible interactions, it is a natural approach to include the simplest yet significant forms of coupling that the structural information field can have with established fields (e.g., the Ricci scalar R representing spacetime curvature, and terms representing the self-dynamics of like ). This aligns with the spirit of Effective Field Theory, which considers all allowed terms under certain symmetries and dimensions, and similar systematic approaches are pursued in constructing general scalar-tensor theories such as Horndeski theory [31] or DHOST theories [36]. The proposed term and the term in this paper are examples considered in this context.

- Dimensional Analysis and Adherence to Fundamental Symmetries: Each term in the Lagrangian must have the correct physical dimensions (the action is dimensionless, while the Lagrangian density typically has dimensions of or ). Furthermore, to ensure the universality of physical laws, the simplest forms that satisfy fundamental symmetries such as Lorentz invariance (locally) and general covariance are prioritized. General covariance is one of the core principles of General Relativity [1,2].

- Consistency with Existing Theories (Correspondence Principle): A new theory should be able to reproduce previously successful and well-verified theories in certain limits. The SIC Lagrangian precisely reduces to standard General Relativity [1,2,33] coupled minimally to matter systems in the limit where the coupling constants , , and the potential becomes a constant (or zero). This is an important feature ensuring that SIC theory aligns with well-established physics at low energies or under specific conditions. Consequently, the values of and can be strongly constrained by the results of existing high-precision gravitational experiments [37].

- Predictive Power and Falsifiability: For a theory to be scientific, it must make testable predictions. Specific (non-zero) values of the parameters and lead to predictions of new physical phenomena not present in standard theories (e.g., the modulation of discussed in Section 3.1). This provides the possibility to verify the theory or at least constrain its parameter space through astronomical observations (e.g., gravitational wave observations [38], black hole shadow observations [39]) or precision experiments [37].

2.4. Derivation of Field Equations

- is the Einstein tensor, representing the curvature of spacetime.

- denotes the covariant derivative, and signifies the d’Alembertian operator. Thus, the term is a geometric term related to the second derivatives of the field.

- is the energy-momentum tensor of standard matter, derived from the standard matter Lagrangian .

- is the energy-momentum tensor of the structural information field, derived from the field’s dynamical part, i.e., , in the standard manner () [2]. This term represents the energy and momentum distribution of the field itself.

2.5. Theoretical Consistency and Exploration Directions

- Causality and Stability: The kinetic term in the presented Lagrangian is a form of k-essence [32]. In such models, the propagation speed of field perturbations can depend on the background value of and its rate of change. Under certain conditions, there is a mathematical possibility that the propagation speed of perturbations in these k-essence models could differ from the speed of light, potentially exceeding it [32,35]. This is an important research topic in general scalar-tensor theories [31,36] and modified gravity theories [11,12]. This aspect is currently regarded as an open possibility. The physical meaning of such solutions, their stability (e.g., the appearance of ghost issues or Laplacian instabilities), and their consistency with macroscopic causality are crucial research topics requiring careful analysis in the future. In this paper, we primarily focus on the solutions of the classical field equations and their phenomenological implications, aiming to explore physically plausible solutions.

- Energy Conditions: For the field to play a cosmologically significant role, its energy-momentum tensor may need to satisfy certain energy conditions (e.g., Weak Energy Condition (WEC), Null Energy Condition (NEC), Dominant Energy Condition (DEC), etc. [2,33]). These conditions are generally considered to characterize physically reasonable matter or fields and are related, for example, to the validity of singularity theorems or the possibility of exotic spacetime structures like wormholes. Whether satisfies these conditions largely depends on the form of the potential and the value of the kinetic coefficient . For instance, explaining dark energy often requires a negative pressure (), which might violate certain energy conditions [35]. To ensure the physical viability of the SIC theory, it is crucial to find parameter regions that satisfy these energy conditions or to clearly understand the physical implications if certain conditions are violated.

- Reduction to Standard Theories: As mentioned in Section 2.3, in the limit where the coupling constants , , and the potential is a constant (or zero), the SIC theory exactly reduces to standard General Relativity [1,2,33] minimally coupled to matter systems. This is an important feature ensuring that the theory satisfies the correspondence principle, aligning with well-established physics at low energies or under specific conditions. Therefore, the predictions of SIC theory can be strongly constrained by comparison with the results of existing precision gravitational experiments [37].

3. Key Predictions and Applications

3.1. Spatial Modulation of the Effective Gravitational Coupling Constant

3.1.1. Theoretical Background

3.1.2. Derivation of the Effective Gravitational Coupling Constant

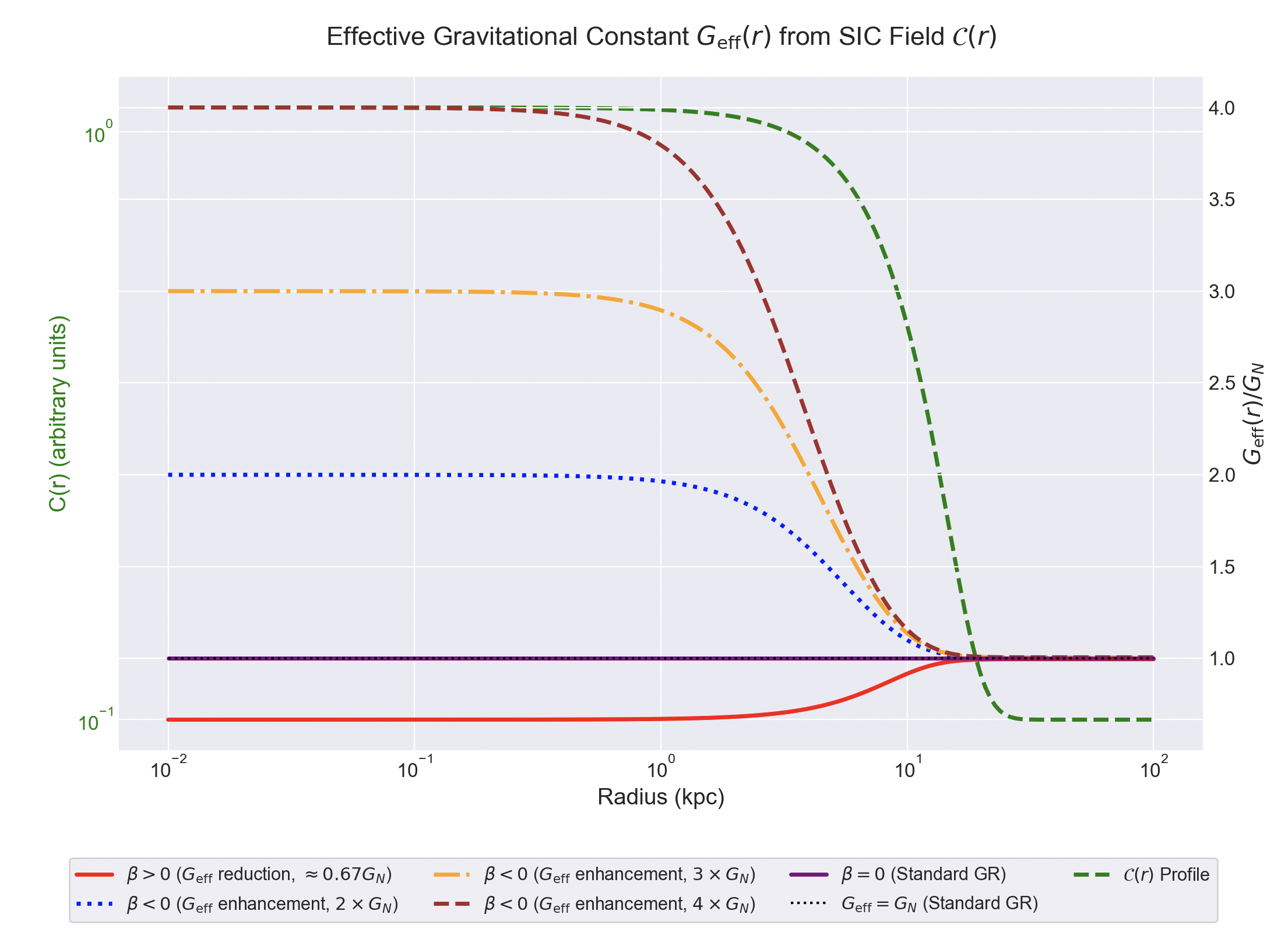

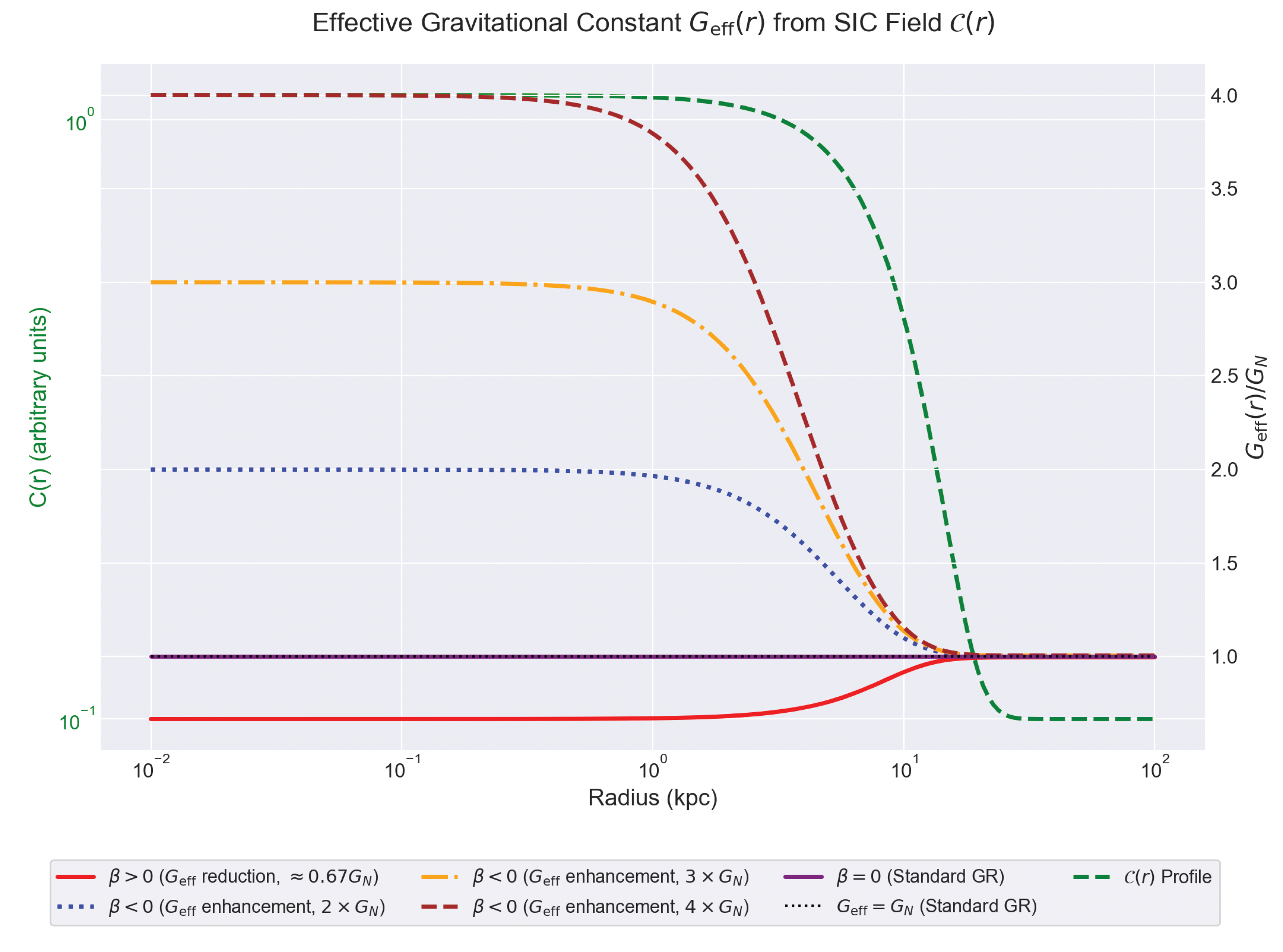

3.1.3. Calculation Model Setup

- : Background value of the structural information field in the cosmic background (e.g., 0.1 arbitrary units). This is the asymptotic value as and can represent the background level of the field uniformly distributed throughout the universe.

- : Additional value of the information field at the celestial center () (e.g., 1.0 arbitrary units). This represents the degree to which information is locally concentrated at the center.

- : Characteristic scale radius of the information field distribution (e.g., 10 kpc). This radius indicates the approximate size of the region where the value is significantly higher than the background value. It can have a physical scale similar to that of the stellar distribution in galaxies or the core radius of dark matter halos.

3.1.4. Quantitative Analysis and Physical Interpretation

- (Gravitational Strengthening Scenario): As can be clearly seen in the figure, for selected negative values of , can be larger than (e.g., 2, 3, or even 4 times in the examples). This implies that in regions such as the galactic center, where the structural information field is very dense, gravity can act much more strongly than predicted by standard theory. Such gravitational strengthening effects could hold significant implications in attempts to explain the dynamical characteristics of galaxies without invoking dark matter [4].

- (Gravitational Weakening Scenario): Conversely, for certain positive values of , can be less than 1 (e.g., approximately 0.67 times in the examples). This indicates an effect where gravity is weakened in regions where the field is dense. Such scenarios could be employed in exploring specific cosmological models or gravitational effects in high-energy environments.

3.1.5. Quantitative Evaluation of the Capability to Replace Dark Matter Effects

3.1.6. Theoretical Consistency and Physical Constraints

3.1.7. Observational Verification Strategy

- Precision Gravitational Lensing Analysis: Strong gravitational lensing images (Einstein rings, multiple images, etc.) and weak gravitational lensing distortions of background galaxy shapes at galactic or cluster scales directly probe the curvature of spacetime. The spatial distribution of predicted by SIC theory could induce lensing effects different from those predicted by standard General Relativity (with constant ). These could be precisely measured by next-generation observational facilities (e.g., the Euclid satellite, the LSST camera on the Vera C. Rubin Observatory) [12,35].

- Celestial Orbit Dynamics: A long-term analysis of precise orbital data of S-stars orbiting the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy (Sgr A*) [39], or rotation curve data from stars or gas in external galaxies [4], can be used to verify minute deviations in the gravitational field due to changes in .

- Gravitational Wave Observations: The waveforms of gravitational waves emitted during the merger of binary black holes or neutron stars, especially during the inspiral, merger, and ringdown phases, are highly sensitive to the value of and spacetime curvature [38]. A spatially varying or the dynamical effects of the field itself could cause subtle modulations in the gravitational wave signal (e.g., additional polarization modes, changes in propagation speed, or alterations in the ringdown frequencies and damping times) different from standard General Relativity. These could be searched for with LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA and future detectors like LISA.

- Large-Scale Structure Formation Simulations: By incorporating the modified gravitational effects predicted by SIC (such as and, if necessary, pressure effects from the field itself) into N-body simulations, one can predict how the formation and evolution of cosmic large-scale structures (galaxy cluster distributions, cosmic web, voids, etc.) would compare with observed statistical properties (e.g., matter power spectrum, galaxy cluster mass function).

- Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Spectrum: Quantum fluctuations of the field in the early universe or temporal variations of could leave imprints on the temperature and polarization anisotropy angular power spectra of the CMB. A precise calculation of these effects and comparison with observational data from missions like the Planck satellite [5] could provide constraints on early universe conditions and SIC parameters.

- Galaxy Scaling Relations and Evolution: Examining whether the evolution of scaling relations in galaxies observed at different redshifts (i.e., different cosmic epochs)—such as the mass-luminosity relation or mass-velocity dispersion relations (e.g., Tully-Fisher, Faber-Jackson relations)—is consistent with the predictions of SIC (which might include a cosmological evolution of ).

3.1.8. Outlook

3.2. Expansive Applications and Unification Potential of SIC Theory

3.2.1. Unifying Framework for the Four Fundamental Forces

3.2.2. Information Structural Interpretation of Black Hole Physics

3.2.3. Cosmological Dynamics and Dark Energy

3.2.4. Fundamental Link with Quantum Information

- −

- In this case, the amplitude of the field could represent the density or strength of the information structure, while the phase could represent internal states of information, cyclical flows, or dynamical degrees of freedom associated with certain symmetries.

- −

- Each term in the SIC Lagrangian could be naturally modified accordingly. For example, the kinetic term could be generalized to forms like or , and could include separate dynamical terms for and (e.g., , ). The potential could take the form or . The information-gravity coupling term could naturally be extended to (or ).

- −

- In particular, the dynamics of the phase (e.g., a term like ) might induce structures analogous to new U(1) gauge symmetries or provide new insights into the unification of the four fundamental forces (Section 3.2.1) through interaction with existing gauge fields. For example, one could explore the possibility of acting like an effective gauge potential. This extends ideas from condensed matter physics, where phase degrees of freedom of superfluids or superconductors describe macroscopic quantum phenomena, to cosmological scales.

3.2.5. Integrative Outlook and Future Development Directions

4. Discussion and Future Work

4.1. Main Content and Current Significance of SIC Theory

4.2. Priority Research Tasks for Theoretical Development

4.2.1. Realistic Modeling of the Structural Information Field

- Dynamical Determination of the Profile: The Gaussian-form profile used as an example in this paper is based on a static assumption and serves as a simplified model. In the future, it is necessary to simultaneously solve the equation of motion for the field and the modified Einstein equations, as presented in Section 2.4, in various astrophysical and cosmological environments (e.g., during galaxy formation and evolution [4], in galaxy clusters, and within the cosmic large-scale structure [5]). This will allow for the exploration of the dynamical distribution and temporal evolution of the field that forms spontaneously in such environments. This includes modeling the distribution according to the multi-component structures of galaxies (bulge, disk, halo) and researching the evolution of the field in the cosmological background (e.g., its value in the early universe and at present).

- Concretization of the Potential : The form of the self-interaction potential is a key element determining the dynamical characteristics of SIC theory and its cosmological consequences, such as the mass of the field, its vacuum states, and the possibility of phase transitions. Based on various theoretical motivations (e.g., specific symmetry assumptions, stability conditions, consistency with models of inflation or dark energy [32,35]), polynomial forms like or other functional forms (e.g., exponential, logarithmic, trigonometric) should be considered. The physical meaning of each parameter and observational constraints must be systematically analyzed. In particular, the possibility of a cyclic universe model, as discussed in Section 4.5.1, may be closely related to specific forms of .

4.2.2. Comparative Analysis with Precise Observational Data

- Detailed Analysis of Galaxy Rotation Curves and Mass Distributions: A systematic fitting of the SIC model (using dynamically determined or reasonably modeled distributions and the resulting ) should be performed on the hundreds or thousands of precisely measured rotation curve data [4] and total mass distributions (inferred from stellar and gas distributions, and gravitational lensing effects) available for various types and sizes of galaxies (e.g., spiral, elliptical, dwarf galaxies). Through this, the explanatory power of SIC should be quantitatively assessed via statistical comparison (e.g., analysis, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for model selection) with the standard CDM model (including dark matter) [5] and other leading modified gravity theories such as MOND [40], to obtain constraints on the model parameters.

- In-depth Analysis of Gravitational Lensing Phenomena: Strong gravitational lensing (e.g., multiple images, Einstein rings) and weak gravitational lensing (cosmic shear) are very powerful tools for directly probing the distribution of gravitational fields on different scales. The effects of the variation predicted by SIC on these lensing phenomena must be precisely calculated and compared with actual observational data (e.g., existing data from HST, DES, KiDS, and vast high-quality data expected from next-generation observational projects such as Euclid, LSST (Vera C. Rubin Observatory), and the Roman Space Telescope [12,35]) to constrain model parameters and verify the theory’s validity.

4.2.3. SIC Interpretation in Black Hole Physics

-

Numerical Relativity Simulations: In the extreme gravitational field environment around black holes, obtaining analytical solutions is often difficult. Therefore, the modified Einstein equations and the field equation of motion must be solved numerically using numerical relativity codes. Through this, the following observable effects can be predicted and quantified:

- Changes in black hole shadow size and shape: The standard GR prediction for a Schwarzschild black hole shadow radius is approximately . In SIC, not only is G replaced by , but the field itself can also affect spacetime, so changes in the shadow, which could be expressed in the form , must be calculated.

- Changes in the dynamics, temperature distribution, and electromagnetic radiation spectrum of black hole accretion disks.

- Alterations in gravitational wave waveforms (inspiral, merger, ringdown phases) from binary black hole/neutron star mergers [38].

- Utilizing Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Data: Predictions from the SIC model should be compared with EHT data [39] on the observed shadow size and shape of M87* and Sgr A* at the center of our galaxy to explore the possibility of obtaining concrete constraints on the value of the field or the coupling constant near black holes.

- Possibility of an Informational Description of Black Hole Interiors: Furthermore, SIC could lead to attempts to describe the extreme environment inside black holes—particularly the classical singularity problem, which is difficult to describe with spacetime geometry alone—using purely informational degrees of freedom, such as specific configurations of the field or quantum information states. This is an exploratory area that could provide important clues for resolving the black hole singularity problem and the information paradox [8,9,10].

4.2.4. Deepening the Fundamental Link with Quantum Information Theory

-

Exploring the Microscopic Foundation of the Field: As suggested by the ideas in Section 3.2.4, research is needed to substantiate the hypothesis that the field, introduced classically, is a macroscopic manifestation of quantum information (e.g., entanglement entropy [21,23,25,31], or information content inherent in quantum states). For instance, this could involve attempts to extend the AdS/CFT correspondence [17,18] to the SIC framework (elucidating a relationship like ) or research on information preservation mechanisms through analogies with quantum error correction codes (QECC) [21,22,23,25]. The formula(where K is a bulk-boundary propagator, and is a specific operator in the boundary theory) represents such a connection. These connections are very challenging but could provide a profound physical basis for SIC theory and enrich its meaning.

4.3. Experimental Verification Strategy and Observational Signatures

4.3.1. Short-Term Verification Goals (Within 5 Years)

- Analysis of Terrestrial Precision Gravity Experiment Data: Data from ongoing or planned high-precision gravity experiments, such as tests of the equivalence principle or measurements of the gravitational field using atom interferometry, or tests of the gravitational law at short distances using torsion balance experiments [37], can be re-analyzed from the perspective of SIC theory, or new experiments can be proposed. If the field exhibits minute local variations or interacts weakly with matter, this might manifest as tiny deviations from Newton’s inverse square law or minute variations in fundamental constant values. One should examine whether upper limits can be set for the coupling constant or field-related parameters through these.

- Reviewing the Feasibility of Using Satellite Gravity Mission Data: Data from existing satellite missions that precisely measure Earth’s gravitational field, such as GRACE-FO (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment Follow-On), or from next-generation precision gravity missions that may be planned in the future, can be utilized. If there is a significant distribution or variation of the field within the Earth or the Solar System, one should investigate the possibility of detecting minute gravitational field variation signals (differences from standard GR predictions) on terrestrial or Solar System scales, or of placing constraints on the theory’s parameters [37].

4.3.2. Mid-to-Long-Term Verification Goals (10–20 Years)

- −

- Extreme Mass Ratio Inspiral (EMRI) Systems: Gravitational waves emitted from a small black hole or neutron star spiraling into a supermassive black hole carry highly precise information about spacetime geometry. Spatial variations in the field or could have subtle but cumulative effects on the orbital evolution and gravitational waveforms of such systems, which could be searched for with LISA and others.

- −

- Cosmological Gravitational Wave Background: The spectrum of a stochastic gravitational wave background, potentially generated during inflation or phase transitions in the early universe, could be sensitive to the early universe dynamics of the field and the temporal evolution of .

- −

- Modified Propagation Characteristics: If the field affects the propagation speed or polarization states of gravitational waves, this could lead to verifiable effects in distance measurements to gravitational wave sources (standard sirens) or in multi-messenger astronomy.

4.4. Comparison with Other Theories and Current Limitations of SIC

4.4.1. Comparison with Existing Modified Gravity Theories (Conceptual)

| Theory/Approach | Primary Motivation/Goal | Modification Method (Example) | Comparative Perspective with SIC (Potential & Differentiation) |

| MOND[40] | Galaxy rotation curves (explanation without dark matter) | Modification of Newtonian dynamics or inertia at low accelerations () | SIC has the potential to explain similar phenomena (e.g., gravity enhancement at galactic scales) by varying through the distribution. However, while MOND primarily focuses on phenomenological modification, SIC proposes a more fundamental motivation (information structure) and aims to encompass cosmology as a whole. |

| Gravity[34] | Dark energy, early universe inflation, gravity modification | Replacing the Ricci scalar R in the Einstein-Hilbert Lagrangian with a general function | SIC also modifies the gravitational Lagrangian via the information-gravity coupling term (i.e., effectively an form). However, unlike theories, the independent dynamics of the field itself (kinetic term, potential) provide additional degrees of freedom and richer phenomenology. Under certain conditions, theories might be encompassed as a special case of SIC. |

| Theory/Approach | Primary Motivation/Goal | Modification Method (Example) | Comparative Perspective with SIC (Potential & Differentiation) |

| Scalar-Tensor Theory[30,31] | Brans-Dicke principle, varying gravitational constant, dark energy, inflation, etc. | One or more scalar fields coupling to gravity in (non-)minimal forms | SIC introduces a scalar field intended to impart a specific physical meaning of “structural complexity of information.” In addition to the non-minimal coupling typical of standard scalar-tensor theories, SIC considers more general and complex dynamics from the outset by including a unique higher-order kinetic term () [32,36]. |

| Extra Dimension Theory | Hierarchy problem, force unification, dark matter candidates, etc. | Assumption of higher-dimensional spacetime beyond 4D (e.g., gravity alone can propagate into extra dimensions) | SIC, for now, attempts to explain phenomena through information structure within standard 4D spacetime. However, as discussed in Section 3.2.4, the possibility that the field might be an effective theoretical representation of a more fundamental higher-dimensional “information structure space” can be explored as a separate issue in the future. (General reviews on extra dimension theories can be found, for example, in [35] etc.) |

| ]@ >p() * 0.2857 >p() * 0.2500 >p() * 0.1786 >p() * 0.2857@ [b]Theory/Approach | [b]Primary Motivation/Goal | [b]Modification Method (Example) | [b]Comparative Perspective with SIC (Potential & Differentiation) |

| SIC (This Proposal) | Information structure-centric cosmology, attempt at unified explanation | Proposing (non-minimal coupling of field and R, unique dynamics of ) | Attempts a unified approach to the modulation of effective gravity, potential unification of forces, resolution of cosmological problems (dark matter, dark energy, etc.) through a new physical entity . The calculation example in Section 3.1 showed the potential to explain a significant portion of dark matter effects. |

4.4.2. Current Limitations of SIC Theory

- Extensiveness and Indeterminacy of Parameter Space: The free parameters of the theory, including the coupling constants () and the specific functional form of the self-interaction potential in the current SIC Lagrangian, are not yet sufficiently constrained by observations or fundamental theoretical principles. This limits the concrete predictive power of the theory. Systematic exploration of the parameter space and the establishment of constraints through various astronomical observational data (e.g., CMB [5], supernovae [6,7], large-scale structure distribution, etc.) are essential for future work.

- Lack of Quantum Foundation and Consistency Issues: SIC is currently described primarily at the level of classical field theory. Crucial theoretical challenges, such as a complete method for quantizing the field, the renormalizability of the theory, and its consistent integration with quantum gravity [21,22] at the Planck scale, remain unresolved. Without understanding these quantum aspects, it is difficult to ascertain the fundamental validity of the theory.

- Concrete Physical Reality and Measurement of the Field: The concept of the field as “structural complexity of information” still has an abstract aspect regarding its definition and physical content. A clearer understanding and methodology are needed concerning how it quantitatively connects to existing physical quantities (e.g., entropy [27,28], entanglement measures [19], etc.) and how it can be independently measured or observed. Finding experimental or observational evidence that can directly confirm the existence of the field will be a key part of verifying the theory.

4.5. Long-Term Development Directions and Physical Implications

4.5.1. Potential for Expansion into an “Information Physics” Paradigm

- What is the relationship between information and spacetime, and which is more fundamental? Or how do they emerge from each other? (e.g., Wheeler’s “It from Bit” [14], the holographic principle [3,15,16], and recent ideas about spacetime emerging from entanglement [21,23,25]). The ordering of causality may be perceived as time, and this perception itself could be a phenomenon that emerges at the moment information becomes structured.

- Can physical laws themselves be understood as manifestations of rules for processing, storing, and transmitting information? (e.g., Landauer’s “Information is Physical” principle [13] and its extensions)

- Can the evolution of the universe be understood as a process of storing, processing, and transmitting information? In this regard, if dark energy in SIC originates from the dynamics of the field (see Section 3.2.3), then a specific potential for the field opens the possibility for a cyclic universe model [explored in some modified gravity or scalar field cosmology models, see, e.g., discussions in [35]] where the universe re-contracts after the current phase of accelerated expansion. In this case, one could explore the intriguing hypothesis that the extremely compressed information structure (the final state of the field) at the end of each cosmic cycle might, like genetic information, determine or influence some of the initial conditions or physical laws of the next universe. This would further deepen the information-centric perspective on the origin and ultimate fate of the universe.

- The Gap Between the Probabilistic Description of Quantum Mechanics and Macroscopic Causality: Quantum field theory describes the microscopic world probabilistically, which sometimes leads to interpretational difficulties regarding clear causal continuity in physical processes. If the universe fundamentally operates only in a probabilistic and indeterminate manner, how can the coherent and orderly macroscopic world as we observe it exist? One of the fundamental motivations of SIC theory is an attempt to answer such questions. One could explore the hypothesis that the structural information field plays a role in mediating or ensuring causal continuity and coherence when quantum-level probabilistic possibilities manifest as concrete, determinate physical phenomena in the macroscopic world. That is, the field, through the structuring of information, might play a role in “selecting” or “reinforcing” specific causal paths amidst probabilistic degrees of freedom, thereby providing an information-based explanation for the emergence of physical laws and the orderly evolution of the universe. This is a very challenging and profound topic, but it could be one of the ultimate implications of the information-centric paradigm pursued by SIC. (Such issues are also related to the measurement problem and interpretations of quantum mechanics [19]).

4.5.2. Potential Technological Applications and Exploration of Exotic Phenomena (Very Long-Term Perspective)

- New forms of quantum computing or information processing systems (related to quantum information theory [19]).

- If the theory permits and technological means are secured, techniques for local spacetime structure manipulation through field control.

- Novel communication or energy transmission methods based on information structure.

- Furthermore, deeper research into field dynamics might explore the possibility of solutions allowing for stable yet non-standard information propagation characteristics (see causality discussions in Section 2.5 and 3.1.6). If such solutions exist and are physically meaningful, they would pose fundamental questions to our understanding of causality in spacetime and, at a very abstract level, could open possibilities for explaining phenomena that appear to transcend spatiotemporal constraints through efficient connectivity (`shortcuts’) within an `information structure space’ (e.g., effects appearing like effective superluminal information transfer). However, this currently lies purely in the realm of theoretical speculation and must be preceded by rigorous mathematical formulation and verification of physical consistency (especially consistency with macroscopic causality).

4.6. Concluding Outlook

References

- Albert Einstein. Die grundlage der allgemeinen relativitätstheorie. Annalen der Physik, 49(7):769–822, 1916.

- Sean M Carroll. Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Raphael Bousso. The holographic principle. Reviews of Modern Physics, 74(3):825–874, 2002.

- Gianfranco Bertone, Dan Hooper, and Joseph Silk. Particle dark matter: evidence, candidates and constraints. Physics Reports, 405(5-6):279–390, 2005.

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. vi. cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 641:A6, 2020.

- Adam G Riess et al. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. Astronomical Journal, 116(3):1009–1038, 1998.

- Saul Perlmutter et al. Measurements of omega and lambda from 42 high redshift supernovae. Astrophysical Journal, 517(2):565–586, 1999.

- Stephen W Hawking. Breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse. Physical Review D, 14(10):2460–2473, 1976.

- Don N Page. Information in black hole radiation. Physical Review Letters, 71(23):3743–3746, 1993.

- Ahmed Almheiri, Donald Marolf, Joseph Polchinski, and James Sully. Black holes: complementarity or firewalls? Journal of High Energy Physics, 2013(2):062, 2013.

- S Shankaranarayanan and Jishnu Pradeep Johnson. Modified theories of gravity: Why, how and what? arXiv preprint, 2022.

- Timothy Clifton, Pedro G Ferreira, Antonio Padilla, and Constantinos Skordis. Modified gravity and cosmology. Physics Reports, 513(1-3):1–189, 2012.

- Rolf Landauer. Information is physical. Physics Today, 44(5):23–29, 1991.

- John Archibald Wheeler. Information, physics, quantum: The search for links. In Wojciech H Zurek, editor, Complexity, Entropy, and the Physics of Information. Addison-Wesley, 1990.

- Gerard ’t Hooft. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. arXiv preprint, 1993.

- Leonard Susskind. The world as a hologram. Journal of Mathematical Physics, 36(11):6377–6396, 1995.

- Juan M Maldacena. The large n limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 38(4):1113–1133, 1999.

- Veronika E Hubeny. The ads/cft correspondence. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 32(12):124010, 2015.

- Michael A Nielsen and Isaac L Chuang. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Patrick Hayden and John Preskill. Black holes as mirrors: quantum information in random subsystems. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2007(09):120, 2007.

- Daniel Harlow. The ryu-takayanagi formula from quantum error correction. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 354(3):865–912, 2017.

- Fernando Pastawski, Beni Yoshida, Daniel Harlow, and John Preskill. Holographic quantum error-correcting codes: toy models for the bulk/boundary correspondence. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2015(6):149, 2015.

- Tanay Kibe, Prabha Mandayam, and Ayan Mukhopadhyay. Holographic spacetime, black holes and quantum error correcting codes: A review. European Physical Journal C, 82(5):463, 2022.

- Erik P Verlinde. On the origin of gravity and the laws of newton. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2011(4):029, 2011.

- Ahmed Almheiri, Thomas Hartman, Juan Maldacena, Edgar Shaghoulian, and Amirhossein Tajdini. The entropy of hawking radiation. Reviews of Modern Physics, 93(3):035002, 2021.

- Stephen W Hawking. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 43(3):199–220, 1975.

- Jacob D Bekenstein. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D, 7(8):2333–2346, 1973.

- Claude E Shannon. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3):379–423, 1948.

- Peter D Grunwald and Paul MB Vitanyi. Algorithmic information theory. arXiv preprint, 2008.

- Carl Brans and Robert H Dicke. Mach’s principle and a relativistic theory of gravitation. Physical Review, 124(3):925–935, 1961.

- Gregory Walter Horndeski. Second-order scalar-tensor field equations in a four-dimensional space. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 10(6):363–384, 1974.

- Cristian Armendáriz-Picón, Viatcheslav Mukhanov, and Paul J Steinhardt. Essentials of k-essence. Physical Review D, 63(10):103510, 2001.

- Steven Weinberg. Gravitation and Cosmology: Principles and Applications of the General Theory of Relativity. John Wiley & Sons, 1972.

- Thomas P Sotiriou and Valerio Faraoni. f(r) theories of gravity. Reviews of Modern Physics, 82(1):451–497, 2010.

- Austin Joyce, Bhuvnesh Jain, Justin Khoury, and Mark Trodden. Beyond the cosmological standard model. Physics Reports, 568:1–98, 2015.

- David Langlois. Dark energy and modified gravity in degenerate higher-order scalar-tensor (dhost) theories: a review. arXiv preprint, 2018.

- Clifford M Will. Theory and Experiment in Gravitational Physics. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Benjamin P Abbott et al. Observation of gravitational waves from a binary black hole merger. Physical Review Letters, 116(6):061102, 2016.

- Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration. First m87 event horizon telescope results. i. the shadow of the supermassive black hole. Astrophysical Journal Letters, 875(1):L1, 2019.

- Mordehai Milgrom. A modification of the newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical Journal, 270:365–370, 1983.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).