Submitted:

07 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

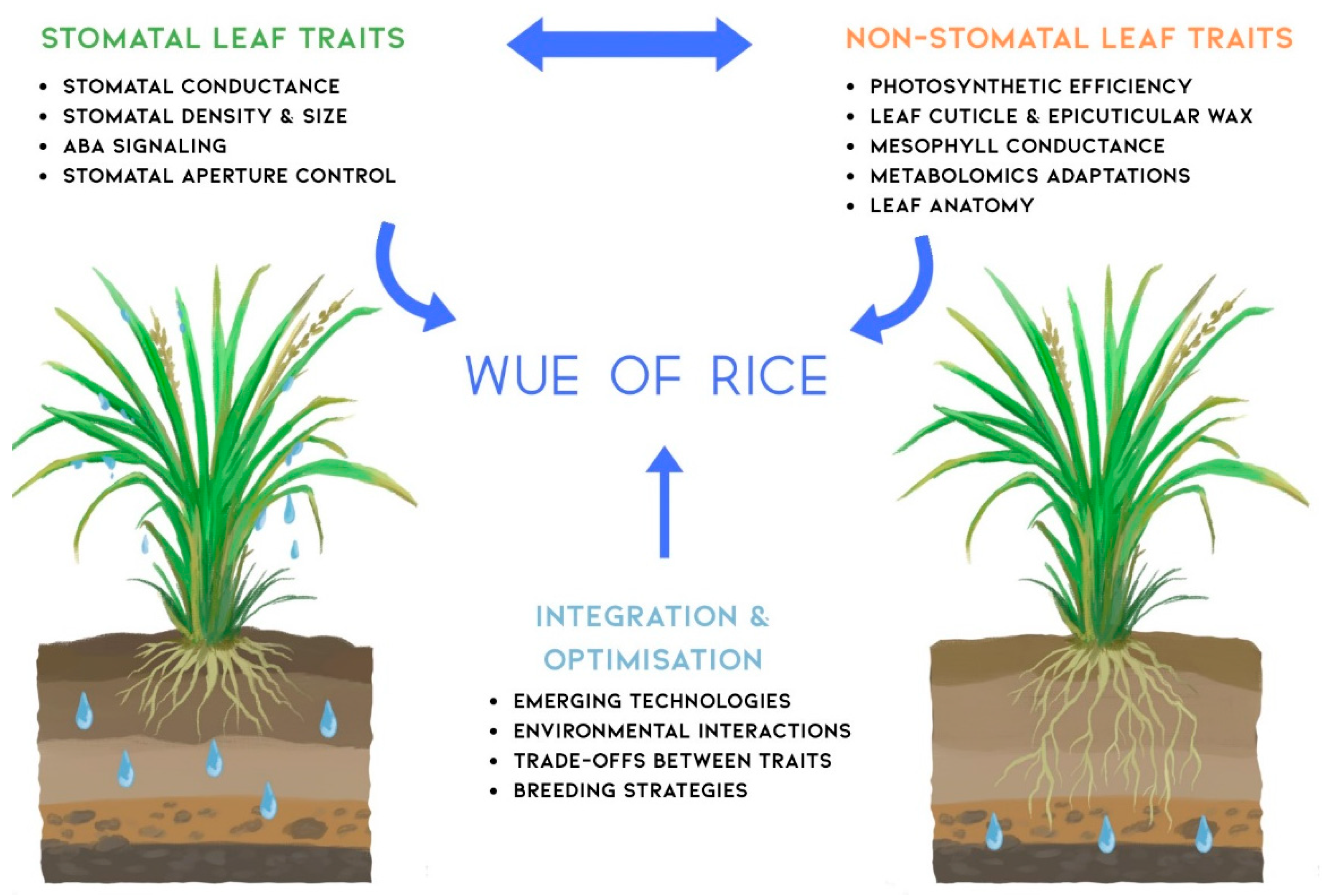

2. Stomatal Leaf Traits and WUE in Rice

2.1. Stomatal Density, Size and Arrangement

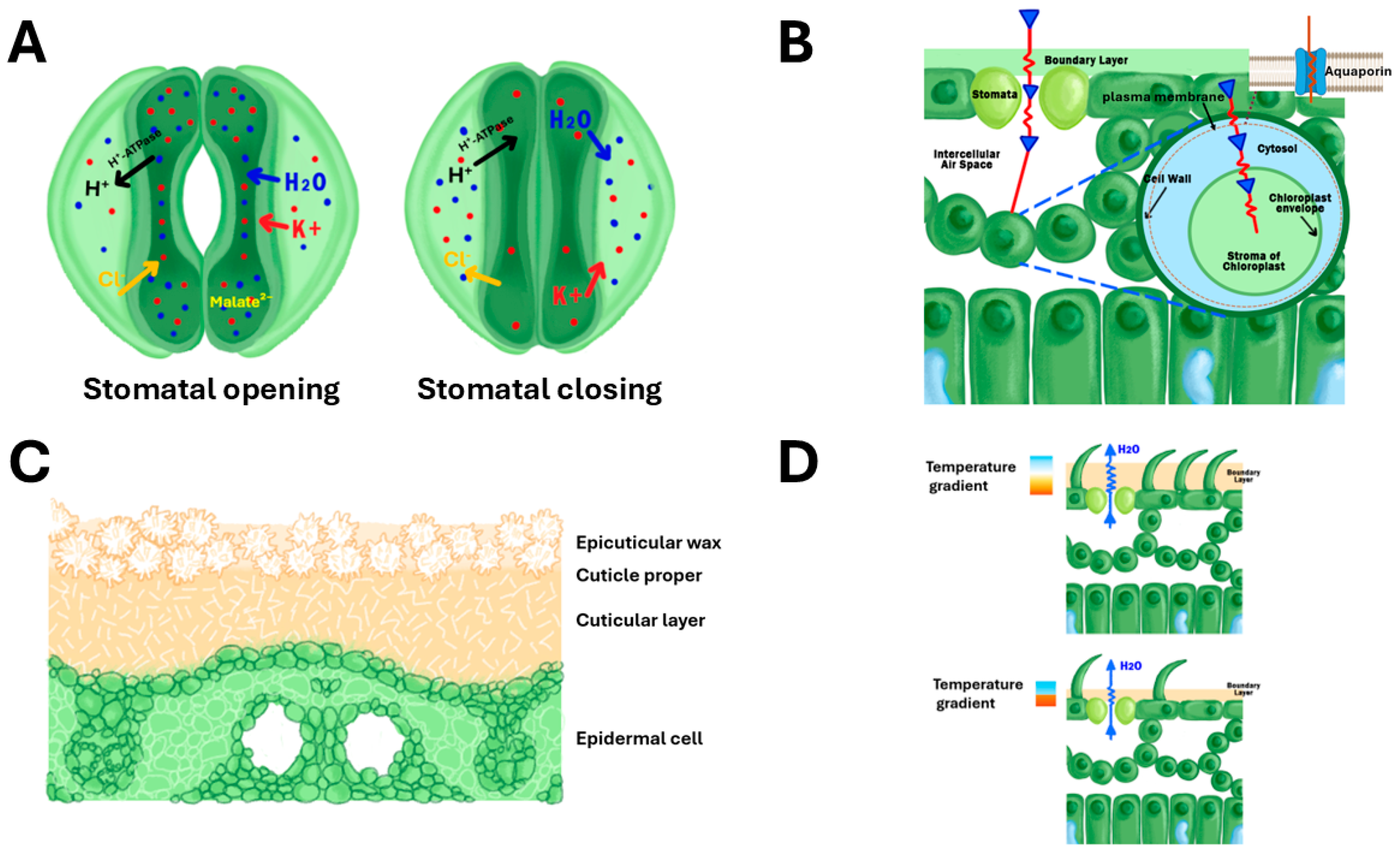

2.2. Stomatal Conductance and Aperture

2.3. Regulation of Transpiration and Carbon Dioxide Uptake

3. Non-Stomatal Leaf Traits and WUE in Rice

3.1. The Role of ΦPSII in Photosynthetic Efficiency

3.2. Leaf Anatomy

3.3. Leaf Cuticle and Epicuticular Wax

3.4. Metabolomics Changes in the Leaves

3.5. Mesophyll Conductance (gm) and Intrinsic WUE

3.6. Leaf Canopy Architecture

3.7. Leaf Pubescence and Boundary Layer Resistance

3.8. Carbon Fixation Efficiency

4. Integrating Stomatal and Non-Stomatal Traits for WUE Improvement

4.1. Interactions and Trade-Offs Among Leaf Traits

4.2. Breeding Strategies for Optimising WUE Through Leaf Traits

4.3. Agronomic Practices and Environmental Factors Influencing WUE

| A. Stomatal leaf Traits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Locus ID | Role | WUE Association |

| OsEP3 | LOC_Os02g15950 | Regulates stomatal guard cell development [101]. ERECT PANICLE3 |

↑ WUE Optimises stomatal development for better water regulation |

| OsKAT1 | LOC_Os01g55200 | Regulates stomatal opening and closing by facilitating potassium ion flux, which directly affects stomatal movement and plant water regulation [102,103] K+ TRANSPORTER 1 |

↑ WUE improves stomatal control |

| OsSDD1 | LOC_Os03g0143100 | Mutations lead to higher stomatal density [13] STOMATAL DENSITY AND DISTRIBUTION |

↓ WUE increases water loss via excess stomata |

| OsTMM | LOC_Os01g02060 | Mutations can lead to irregular stomatal spacing, affecting gas exchange efficiency [13]. TOO MANY MOUTHS |

↓ WUE disrupts stomatal patterning |

| OsEPF1 | LOC_Os04g0637300 | Overexpress reduce stomatal density [36] EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR1 |

↑ WUE reduces transpiration |

| OsSPCH1 | LOC_Os06g33450 | Essential for the initiation of stomatal lineage, termination of meristemoid fate and the transition to guard mother cell (GMC) identity. Overexpression expression leads to higher stomatal density [33,104] SPEECHLESS1 |

↓ WUE Overexpression results in increased water loss |

| OsSPCH2 | LOC_Os02g15760 | alterations in stomatal size and density in stress conditions. Overexpression increases density [13,105] SPEECHLESS2 |

↓ WUE Overexpression results in increased water loss |

| OsMUTE | LOC_Os05g51820 | Essential for the initiation of stomatal lineage, termination of meristemoid fate and the transition to GMC identity. Involves in the differentiation of stomatal precursor cells. It plays a critical role in determining stomatal size by regulating the development of guard cells [104] | ↑ WUE ensures proper stomatal function |

| OsFAMA | LOC_Os05g50900 | Essential for the initiation of stomatal lineage, termination of meristemoid fate and the transition to GMC identity [104] | ↑ WUE Maintains correct stomatal identity for optimal function |

| OsFLP | LOC_Os07g43420 | Regulates the orientation of GMC symmetrical division [104] FOUR LIPS |

↑ WUE Regulates stomatal spacing for efficient gas exchange |

| B. Non-stomatal leaf traits | |||

| Gene | Locus ID | Role | WUE Association |

| OSH43 | LOC_Os03g56110 LOC_Os03g57560 |

Overexpression results in broader leaves, increased tiller number, and more flowers [106]. ORYZA SATIVA HOMEOBOX43 | ↑ WUE No direct evidence. |

| OsABCG9 | LOC_Os04g44610 | Mutations can lead to reduced cuticular wax content, resulting in increased sensitivity to drought and other environmental stresses[107] | ↓ WUE Mutation increases drought sensitivity due to water loss |

| GL1 | LOC_Os05g02730 | controlling wax synthesis in rice leaves [108] GLOSSY1 |

↑ WUE Improves cuticle barrier to reduce water loss |

| OSGL1-1 | LOC_Os09g25850 LOC_Os09g25850 |

Increase leaf cuticular wax deposition and enhance drought tolerance [60] GLOSSY1-1 |

↑ WUE Enhances drought resistance |

| OsGL1-2 | LOC_Os02g08230 | Overexpression increases cuticular wax production and improves drought tolerance [108] GLOSSY1-2 |

↑ WUE Overexpression reduces water loss |

| OsWR1 | LOC_Os02g10760 | Overexpression increases the expression of genes involved in wax synthesis [109] WAX SYNTHESIS REGULATORY GENE1 | ↑ WUE Overexpression reduces water loss |

| OsCutA1 | LOC_Os10g23204 | Overexpression increases cuticular wax production and improves drought tolerance, a promising gene for engineering rice plants with enhanced drought tolerance [59] | ↑ WUE Overexpression reduces water loss |

| YGL1 | LOC_Os05g28200 | Overexpression results in darker green leaves, increased chlorophyll content, and increased photosynthetic activity. This leads to improved growth and increased yields [110]YELLOW-GREEN LEAF1 | ↑ WUE Overexpression improves carbon assimilation efficiency |

| OsHB2 | LOC_Os10g33960 | Overexpression of the OsHB2 gene results in longer roots, broader leaves, and increased tolerance to drought and salinity stress [111] HOMOEOBOX1 | ↑ WUE Overexpression improves water capture and leaf area for photosynthesis |

| RCN1 | LOC_Os11g05470 | Inhibiting flowering transition and delaying heading under drought. Many rachis branches in the panicle and high yield [112] ROOTS CURL IN NAPHTHYLPHTHALAMIC ACID1 |

± WUE Delays maturity but may improve yield under drought |

| OsCKX2 | LOC_Os01g10110 | Produce larger leaves, more flowers, and higher yields [113] CYTOKININ OXIDASE/DEHYDROGENASE2 |

↑ WUE Improves resource allocation for higher yield |

| Gn1a | LOC_Os01g10110 | Improves grain yield, resulting in more flowers and larger grains [114] GRAIN NUMBER 1a identical to CKX2 |

↑ WUE Increases yield potential under stress |

| NAL3 | LOC_Os12g01120 | Overexpression results in broader leaves, reduced tiller number, increased lateral root development, and larger grains [115]NARROW LEAF3 | ↑ WUE Overexpression enhances soil water access and light interception |

| NRL1 | LOC_Os12g37190 | Overexpression results in wider leaves, increased plant height, larger vascular bundles, stronger stems, and higher yields [106,116] NARROW AND ROLLED LEAF1 |

↑ WUE Overexpression improves plant robustness and water transport |

| NAL1 | LOC_Os04g52479 | Overexpression results in broader leaves, reduced tiller number, increased lateral root development, and larger grains [117] NARROW LEAF1 |

↑ WUE Improves growth under water-limited conditions |

| NAL7 | LOC_Os03g06654 | Increased expression could have wider leaves, taller plants, and higher yields [106,117]. NARROW LEAF7 |

↑ WUE Enhances light interception and productivity |

| OsSPL14 | LOC_Os08g39890 | Regulates tiller number and panicle branching, which can also lead to increased grain yield [118]. SQUAMOSA PROMOTOR BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE14 |

↑ WUE Enhances yield per unit water use |

| OsSPL9 | LOC_Os05g33810 | Increases grain number per panicle and yield, and regulates drought tolerance, which can improve rice performance in dry environments [119]. SQUAMOSA PROMOTOR BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE9 |

↑ WUE Enhances productivity under drought stress |

| WSL1 | LOC_Os06g39750 | Involved in the biosynthesis of cuticular wax in rice leaves [120] WHITE STRIPED LEAF1 |

↑ WUE Reinforces leaf cuticle to reduce evaporation |

| OsMyb6 | LOC_Os06g10350 | Overexpression in rice improves drought and salinity tolerance [121] MYB-TKF6 |

↑ WUE Overexpression enhances stress response and water retention |

| OsPIP1;1 | LOC_Os02g44630 | facilitate osmotic water transport across membranes [122] PLASMAMEMBRANE INTRINSIC PROTEIN1;1 |

± WUE Can improve water uptake or increase loss depending on conditions |

| OsPIP2;1 | LOC_Os07g26690 | contributes to water transport and is highly expressed in roots and leaves [122] PLASMAMEMBRANE INTRINSIC PROTEIN1;1 |

± WUE Context-dependent water transport regulation |

| OsNAC6 | LOC_Os01g66120 | Regulates stress responses, including drought tolerance, by modulating root architecture and other physiological traits. Overexpressing transgenic plants displayed an accelerated leaf senescence phenotype at the grain-filling stage [123] NAM, ATAF1/2, and CUC2-FAMILY6 |

± WUE Accelerates senescence; balance needed for net benefit |

| OsDREB2B | LOC_Os05g27930 | Involves in water- and heat-shock stress responses and tolerance [124] DEHYDRATION-RESPONSE ELEMENT-BINDING PROTEIN2 |

↑ WUE Boosts adaptive response under stress |

| OsbZIP23 | LOC_Os02g52780 | Overexpression shows improved tolerance to drought and high-salinity stresses and sensitivity to ABA [125] BASIC-ZIPPER23 |

↑ WUE Enhances tolerance through ABA sensitivity |

| CFL1 | LOC_Os02g31140 | Reduced expression resulted in the reinforcement of cuticle structure [126] CURLY FLAG LEAF1 |

↑ WUE Reduced expression improves barrier to water loss |

| OsCHR4 | LOC_Os07g31450 LOC_Os07g32430 |

regulates leaf morphogenesis and cuticle wax formation [127] CHROMATIN REMODELLING FACTOR4 |

↑ WUE Enhances wax formation for water conservation |

| OsABA8OX3 | LOC_Os09g28390 | Control ABA level and drought stress resistance in rice [128] ABA 8´HYDROXYLASE3 |

↑ WUE Enhances wax formation for water conservation |

| OsAPX7 | LOC_Os04g35520 | involved in signalling transduction pathways related to drought stress response [129] ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE7 |

↑ WUE Activates antioxidant pathways under stress |

| OsTPS1 | LOC_Os01g23530 LOC_Os05g44210 LOC_Os05g44310 LOC_Os05g44300 LOC_Os08g34580 |

enhance the abiotic stress tolerance by increasing the amount of trehalose and proline [130] TREHALOSE-6-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE1 |

↑ WUE Accumulates osmoprotectants for drought resilience |

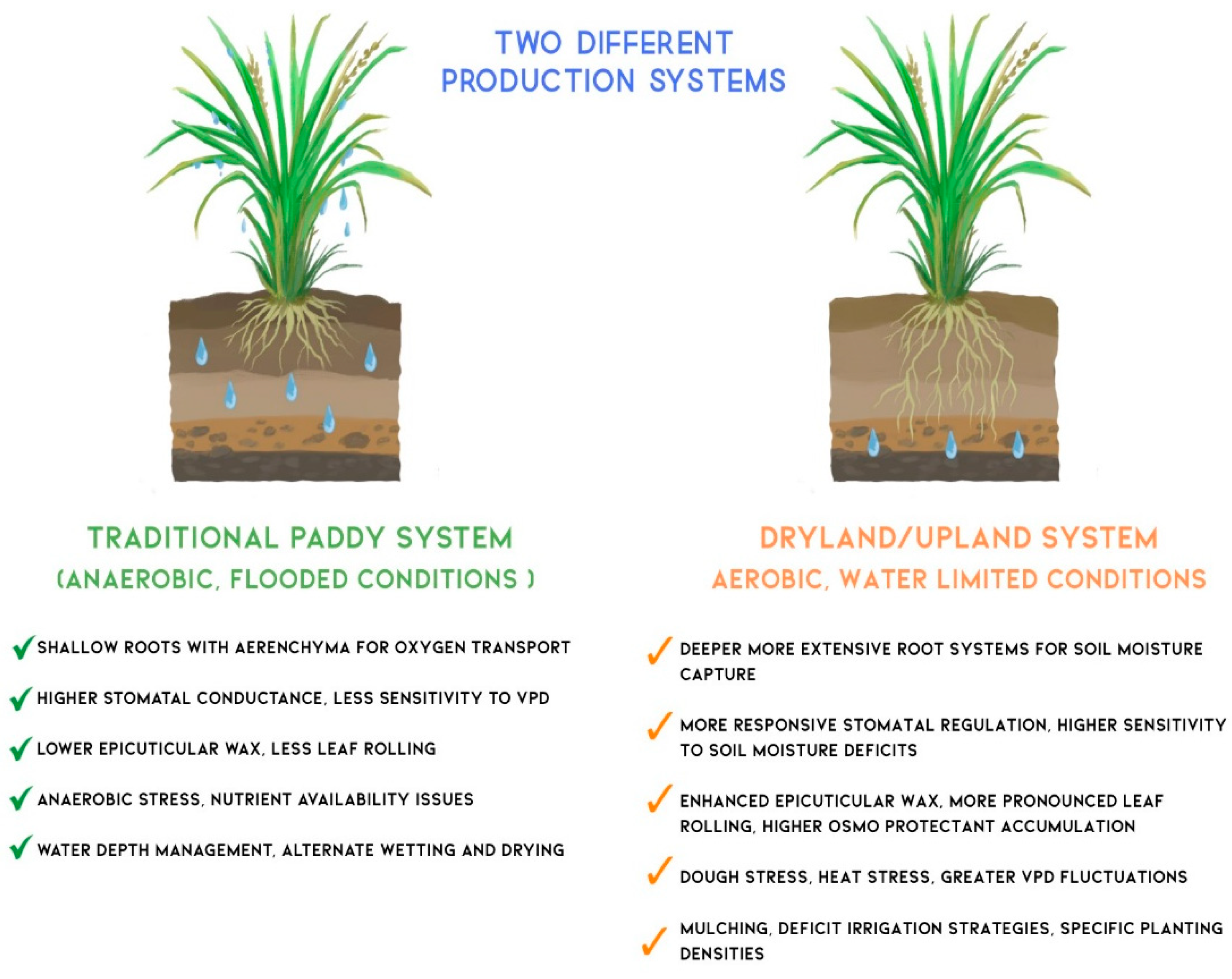

4.4. WUE Optimization Strategies Between Traditional and Dryland Rice Farming Systems

5. Future Perspectives and Research Directions

5.1. Emerging Technologies and Approaches for Studying Leaf Traits and WUE

5.2. Challenges in Developing Water-Efficient Rice Cultivars

5.3. Interaction with Root Traits

6. Towards Enhanced WUE in Rice

7. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WUE | Water Use Efficiency |

| gs | stomatal conductance |

| Δ13C | carbon isotope discrimination |

| gm | mesophyll conductance |

References

- FAO. Water Scarcity – One of the greatest challenges of our time. 2019; Available from: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/story/Water-Scarcity-One-of-the-greatest-challenges-of-our-time/en.

- WHO. 1 in 3 people globally do not have access to safe drinking water – UNICEF, WHO. 2019 27/12/2022]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/18-06-2019-1-in-3-people-globally-do-not-have-access-to-safe-drinking-water-unicef-who.

- Pitaloka, M.K., et al., Induced Genetic Variations in Stomatal Density and Size of Rice Strongly Affects Water Use Efficiency and Responses to Drought Stresses. Front Plant Sci, 2022. 13: p. 801706. [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, L.T., R.S. Caine, and J.E. Gray, Impact of Stomatal Density and Morphology on Water-Use Efficiency in a Changing World. Front Plant Sci, 2019. 10: p. 225. [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, T., A. Riseman, and E. Yamaji, Achieving more with less water: Alternate wet and dry irrigation (AWDI) as an alternative to the conventional water management practices in rice farming. Journal of Agricultural Science, 2011. 3(3): p. 3. [CrossRef]

- Mallareddy, M., et al., Maximizing water use efficiency in rice farming: A comprehensive review of innovative irrigation management technologies. Water, 2023. 15(10): p. 1802. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., et al., Yield, grain quality and water use efficiency of rice under non-flooded mulching cultivation. Field Crops Research, 2008. 108(1): p. 71-81. [CrossRef]

- Borrell, A., A. Garside, and S. Fukai, Improving efficiency of water use for irrigated rice in a semi-arid tropical environment. Field Crops Research, 1997. 52(3): p. 231-248. [CrossRef]

- Fukai, S. and J. Mitchell, Factors determining water use efficiency in aerobic rice. Crop and Environment, 2022. 1(1): p. 24-40. [CrossRef]

- Gago, J., et al., Opportunities for improving leaf water use efficiency under climate change conditions. Plant Science, 2014. 226: p. 108-119. [CrossRef]

- Gobu, R., et al., Unlocking the Nexus between Leaf-Level Water Use Efficiency and Root Traits Together with Gas Exchange Measurements in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plants, 2022. 11(9): p. 1270. [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L. and C. Dold, Water-Use Efficiency: Advances and Challenges in a Changing Climate. Front Plant Sci, 2019. 10: p. 103. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, A., et al., Decoding stomatal characteristics regulating water use efficiency at leaf and plant scales in rice genotypes. Planta, 2024. 260(3): p. 56. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.H., et al., Leaf mass area determines water use efficiency through its influence on carbon gain in rice mutants. Physiologia Plantarum, 2020. 169(2): p. 194-213. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D. and J. Flexas, From one side to two sides: the effects of stomatal distribution on photosynthesis. New Phytol, 2020. 228(6): p. 1754-1766. [CrossRef]

- Akram, H., et al., Impact of water deficit stress on various physiological and agronomic traits of three basmati rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. J Anim Plant Sci, 2013. 23(5): p. 1415-1423.

- Yadav, N., et al., Physiological response and agronomic performance of drought tolerance mutants of Aus rice cultivar Nagina 22 (Oryza sativa L). Field Crops Research, 2023. 290: p. 108760. [CrossRef]

- Condon, A.G., et al., Improving intrinsic water-use efficiency and crop yield. Crop science, 2002. 42(1): p. 122-131.

- Suleiman, S.O., et al., Grain yield and leaf gas exchange in upland NERICA rice under repeated cycles of water deficit at reproductive growth stage. Agricultural Water Management, 2022. 264: p. 107507. [CrossRef]

- Centritto, M., et al., Leaf gas exchange, carbon isotope discrimination, and grain yield in contrasting rice genotypes subjected to water deficits during the reproductive stage. J Exp Bot, 2009. 60(8): p. 2325-39. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., Relationships between stable isotope natural abundances (δ13C and δ15N) and water use efficiency in rice under alternate wetting and drying irrigation in soils with high clay contents. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2022. 13: p. 1077152. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., et al., Leaf rolling precedes stomatal closure in rice (Oryza sativa) under drought conditions. J Exp Bot, 2023. 74(21): p. 6650-6661. [CrossRef]

- Blankenagel, S., et al., Generating Plants with Improved Water Use Efficiency. Agronomy, 2018. 8(9): p. 194. [CrossRef]

- Bramley, H., N.C. Turner, and K.H.M. Siddique, Water Use Efficiency, in Genomics and Breeding for Climate-Resilient Crops: Vol. 2 Target Traits, C. Kole, Editor. 2013, Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg. p. 225-268.

- Brendel, O., The relationship between plant growth and water consumption: a history from the classical four elements to modern stable isotopes. Annals of Forest Science, 2021. 78(2): p. 47. [CrossRef]

- Petrík, P., et al., Leaf physiological and morphological constraints of water-use efficiency in C3 plants. AoB PLANTS, 2023. 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Pandya, P., et al., THERMAL IMAGING AND ITS APPLICATION IN IRRIGATION WATER MANAGEMENT. AgriTech Today, 2023: p. 40.

- Lang, P.L., et al., Century-long timelines of herbarium genomes predict plant stomatal response to climate change. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2024: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, U., et al., IRice plants overexpressing OsEPF1 show reduced stomatal density and increased root cortical aerenchyma formation. Scientific reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 5584.

- Agurla S, et al., Mechanism of Stomatal Closure in Plants Exposed to Drought and Cold Stress. Adv Exp Med Biol., 2018. 1081: p. 215-232.

- Laza, M.R.C., et al., Quantitative trait loci for stomatal density and size in lowland rice. Euphytica, 2010. 172: p. 149-158. [CrossRef]

- Phunthong, C., et al., Rice mutants, selected under severe drought stress, show reduced stomatal density and improved water use efficiency under restricted water conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2024. 15: p. 1307653. [CrossRef]

- Caine, R.S., et al., Rice with reduced stomatal density conserves water and has improved drought tolerance under future climate conditions. New Phytologist, 2019. 221(1): p. 371-384. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, A., B. PRABHU, and M. Sheshshayee, Relevance of Stomatal Traits in Determining the Water Use and Water Use Efficiency in Rice Genotypes Adapted to Different Cultivation Systems. Mysore Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2023. 57(1).

- Malini, M., et al., Abscisic-Acid-Modulated Stomatal Conductance Governs High-Temperature Stress Tolerance in Rice Accessions. Agriculture, 2023. 13(3): p. 545. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Stomata conductance as a goalkeeper for increased photosynthetic efficiency. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 2022. 70: p. 102310.

- Villalobos-López, M.A., et al., Biotechnological advances to improve abiotic stress tolerance in crops. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022. 23(19): p. 12053. [CrossRef]

- Yari Kamrani, Y., et al., Regulatory role of circadian clocks on ABA production and signaling, stomatal responses, and water-use efficiency under water-deficit conditions. Cells, 2022. 11(7): p. 1154. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T.C., et al., Influence of osmotic adjustment on leaf rolling and tissue death in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Physiology, 1984. 75(2): p. 338-341. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., et al., Rice Responses to Abiotic Stress: Key Proteins and Molecular Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2025. 26(3): p. 896. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Guttation: Quantification, Microbiology and Implications for Phytopathology, in Progress in Botany: Vol. 75, U. Lüttge, W. Beyschlag, and J. Cushman, Editors. 2014, Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg. p. 187-214.

- Aloni, R., Leaf Development and Vascular Differentiation, in Vascular Differentiation and Plant Hormones, R. Aloni, Editor. 2021, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 141-162.

- Li, R., et al., Research progress in improving photosynthetic efficiency. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24(11): p. 9286. [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J., et al., Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: an unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Sci, 2012. 193-194: p. 70-84. [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J., et al., Mesophyll conductance to CO2 and Rubisco as targets for improving intrinsic water use efficiency in C3 plants. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2016. 39(5): p. 965-982. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.-P., et al., Quantifying light response of leaf-scale water-use efficiency and its interrelationships with photosynthesis and stomatal conductance in C3 and C4 species. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2020. 11: p. 374. [CrossRef]

- Haworth, M., et al., Integrating stomatal physiology and morphology: evolution of stomatal control and development of future crops. Oecologia, 2021. 197(4): p. 867-883. [CrossRef]

- Terashima, I., et al., Leaf Functional Anatomy in Relation to Photosynthesis. Plant Physiology, 2010. 155(1): p. 108-116. [CrossRef]

- Kang, G., et al., Leaf microstructure and photosynthetic characteristics of a rice midvein-deficient mutant dl-14. Biologia plantarum, 2022. 66: p. 172-177. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., et al., Aquaporins and CO2 diffusion across biological membrane. Frontiers in Physiology, 2023. 14: p. 1205290. [CrossRef]

- Ding, L., et al., Aquaporin Expression and Water Transport Pathways inside Leaves Are Affected by Nitrogen Supply through Transpiration in Rice Plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2018. 19(1): p. 256. [CrossRef]

- Raza, Q., et al., Genomic diversity of aquaporins across genus Oryza provides a rich genetic resource for development of climate resilient rice cultivars. BMC Plant Biology, 2023. 23(1): p. 172. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.X., S. Moon, and K.-H. Jung, Genome-wide expression analysis of rice aquaporin genes and development of a functional gene network mediated by aquaporin expression in roots. Planta, 2013. 238(4): p. 669-681. [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J., et al., CO2 Diffusion Inside Photosynthetic Organs, in The Leaf: A Platform for Performing Photosynthesis, W.W. Adams Iii and I. Terashima, Editors. 2018, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 163-208.

- Oguchi, R., et al., Leaf Anatomy and Function, in The Leaf: A Platform for Performing Photosynthesis, W.W. Adams Iii and I. Terashima, Editors. 2018, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 97-139.

- Takahashi, H. and M. Nakazono, Cavity Tissue for the Internal Aeration in Plants, in Responses of Plants to Soil Flooding, J.-I. Sakagami and M. Nakazono, Editors. 2024, Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore. p. 105-117.

- Muir, C.D., Making pore choices: repeated regime shifts in stomatal ratio. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2015. 282(1813): p. 20151498. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., et al., A β-Ketoacyl-CoA Synthase Is Involved in Rice Leaf Cuticular Wax Synthesis and Requires a CER2-LIKE Protein as a Cofactor. Plant Physiology, 2016. 173(2): p. 944-955. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X., et al., A β-ketoacyl-CoA Synthase OsCUT1 Confers Increased Drought Tolerance in Rice. Rice Science, 2022. 29(4): p. 353-362. [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.-X., et al., Rice OsGL1-1 is involved in leaf cuticular wax and cuticle membrane. Molecular Plant, 2011. 4(6): p. 985-995. [CrossRef]

- Bernaola, L., et al., Epicuticular Wax Rice Mutants Show Reduced Resistance to Rice Water Weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and Fall Armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Environmental Entomology, 2021. 50(4): p. 948-957. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.K., et al., Chapter 26 - Comparative Metabolomics Approach Towards Understanding Chemical Variation in Rice Under Abiotic Stress, in Advances in Rice Research for Abiotic Stress Tolerance, M. Hasanuzzaman, et al., Editors. 2019, Woodhead Publishing. p. 537-550.

- Hassanein, A., et al., Differential metabolic responses associated with drought tolerance in egyptian rice. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol, 2021. 9(4): p. 37-46.

- Jan, R., et al., Drought and UV radiation stress tolerance in rice is improved by overaccumulation of non-enzymatic antioxidant flavonoids. Antioxidants, 2022. 11(5): p. 917. [CrossRef]

- Pons, T.L., et al., Estimating mesophyll conductance to CO2: methodology, potential errors, and recommendations. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2009. 60(8): p. 2217-2234. [CrossRef]

- von Caemmerer, S. and J.R. Evans, Enhancing C3 photosynthesis. Plant Physiology, 2010. 154(2): p. 589-592.

- Flexas, J., et al., Diffusional conductances to CO 2 as a target for increasing photosynthesis and photosynthetic water-use efficiency. Photosynthesis research, 2013. 117: p. 45-59. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W., et al., Stomatal conductance, mesophyll conductance, and transpiration efficiency in relation to leaf anatomy in rice and wheat genotypes under drought. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2017. 68(18): p. 5191-5205. [CrossRef]

- Zait, Y., Á. Ferrero-Serrano, and S.M. Assmann, The α subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein regulates mesophyll CO2 conductance and drought tolerance in rice. New Phytologist, 2021. 232(6): p. 2324-2338. [CrossRef]

- Ye, M., et al., High leaf mass per area Oryza genotypes invest more leaf mass to cell wall and show a low mesophyll conductance. AoB PLANTS, 2020. 12(4). [CrossRef]

- This, D., et al., Genetic analysis of water use efficiency in rice (Oryza sativa L.) at the leaf level. Rice Science, 2010. 3(1): p. 72-86. [CrossRef]

- Baloch, A., et al., Optimum plant density for high yield in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Asian J. Plant Sci, 2002. 1(1): p. 25-27. [CrossRef]

- Hamaoka, N., et al., A hairy-leaf gene, BLANKET LEAF, of wild Oryza nivara increases photosynthetic water use efficiency in rice. Rice (N Y), 2017. 10(1): p. 20. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al., Modeling the leaf angle dynamics in rice plant. PLoS One, 2017. 12(2): p. e0171890. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X., et al., Phytohormones signaling and crosstalk regulating leaf angle in rice. Plant cell reports, 2016. 35: p. 2423-2433. [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-G., et al., A three-dimensional canopy photosynthesis model in rice with a complete description of the canopy architecture, leaf physiology, and mechanical properties. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2019. 70(9): p. 2479-2490. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.J., et al., Exploring relationships between canopy architecture, light distribution, and photosynthesis in contrasting rice genotypes using 3D canopy reconstruction. Frontiers in plant science, 2017. 8: p. 734. [CrossRef]

- T, S. and D. Vijayalakshmi, Physiological and biotechnological approach to improve water use efficiency in rice (Oryza sativa L.): Review. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 2020. 9(5): p. 1044-1048. [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G.D., J.R. Ehleringer, and K.T. Hubick, Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annual review of plant physiology and plant molecular biology, 1989. 40(1): p. 503-537.

- Condon, A.G., et al., Breeding for high water-use efficiency. J Exp Bot, 2004. 55(407): p. 2447-60. [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G. and R. Richards, Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Functional Plant Biology, 1984. 11(6): p. 539-552. [CrossRef]

- Impa, S.M., et al., Carbon Isotope Discrimination Accurately Reflects Variability in WUE Measured at a Whole Plant Level in Rice. Crop Science, 2005. 45(6): p. 2517-2522. [CrossRef]

- Qu, M., et al., Rapid stomatal response to fluctuating light: an under-explored mechanism to improve drought tolerance in rice. Functional Plant Biology, 2016. 43(8): p. 727-738. [CrossRef]

- Wu, A., et al., Quantifying impacts of enhancing photosynthesis on crop yield. Nature plants, 2019. 5(4): p. 380-388. [CrossRef]

- Raju, B.R., et al., Discovery of QTLs for water mining and water use efficiency traits in rice under water-limited condition through association mapping. Molecular Breeding, 2016. 36(3): p. 35. [CrossRef]

- Vinarao, R., et al., QTL Validation and Development of SNP-Based High Throughput Molecular Markers Targeting a Genomic Region Conferring Narrow Root Cone Angle in Aerobic Rice Production Systems. Plants (Basel), 2021. 10(10): p. 2099. [CrossRef]

- Yue, B., et al., QTL Analysis for Flag Leaf Characteristics and Their Relationships with Yield and Yield Traits in Rice. Acta Genetica Sinica, 2006. 33(9): p. 824-832. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, G.T., et al., Genome-wide association mapping of leaf mass traits in a Vietnamese rice landrace panel. PLoS One, 2019. 14(7): p. e0219274. [CrossRef]

- Phetluan, W., et al., Candidate genes affecting stomatal density in rice (Oryza sativa L.) identified by genome-wide association. Plant Science, 2023. 330: p. 111624. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., et al., Genome-wide association study of rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaf traits with a high-throughput leaf scorer. Journal of experimental botany, 2015. 66(18): p. 5605-5615.

- Liu, C., et al., Relationships of stomatal morphology to the environment across plant communities. Nature Communications, 2023. 14(1): p. 6629. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al., Water use efficiency and physiological response of rice cultivars under alternate wetting and drying conditions. ScientificWorldJournal, 2012. 2012: p. 287907. [CrossRef]

- NSW-DPI, DPI Primefact, B. Dunn, Editor. 2023.

- Haonan, Q., et al., Current status of global rice water use efficiency and water-saving irrigation technology recommendations. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science, 2023. 209(5): p. 734-746. [CrossRef]

- Farmonaut. Revolutionizing Australian rice farming: Sustainable water-saving technologies for enhanced productivity. 2024; Available from: https://farmonaut.com/australia/revolutionizing-australian-rice-farming-sustainable-water-saving-technologies-for-enhanced-productivity/.

- 2, S.I.f.P.P., Smart irrigation control in rice growing systems: Application in bankless channel irrigation. 2021.

- Authority., M.D.B. New technology helping rice growers use less water. 2025; Available from: https://www.mdba.gov.au/news-and-events/newsroom/new-technology-helping-rice-growers-use-less-water.

- Thakur, A., et al., Evaluation of planting methods in irrigated rice. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science, 2004. 50(6): p. 631-640. [CrossRef]

- Sangavi, S. and S. Porpavai, Impact of irrigation scheduling and weed management on water use efficiency and yield of direct dry seeded rice. Madras Agricultural Journal, 2018. 105(march (1-3)): p. 1. [CrossRef]

- IRRI. SNP-Seek database.; Available from: https://snp-seek.irri.org/.

- Yu, H., et al., Decreased photosynthesis in the erect panicle 3 (ep3) mutant of rice is associated with reduced stomatal conductance and attenuated guard cell development. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2015. 66(5): p. 1543-1552. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H., et al., Unique features of two potassium channels, OsKAT2 and OsKAT3, expressed in rice guard cells. PLoS One, 2013. 8(8): p. e72541. [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-J., et al., A dominant negative OsKAT2 mutant delays light-induced stomatal opening and improves drought tolerance without yield penalty in rice. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2017. 8: p. 772. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., et al., Multiple transcriptional factors control stomata development in rice. New Phytologist, 2019. 223(1): p. 220-232. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., et al., Genetic bases of the stomata-related traits revealed by a genome-wide association analysis in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Frontiers in genetics, 2020. 11: p. 611. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., et al., Genome-wide association study of rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaf traits with a high-throughput leaf scorer. J Exp Bot, 2015. 66(18): p. 5605-15.

- Nguyen, V.N., et al., OsABCG9 is an important ABC transporter of cuticular wax deposition in rice. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2018. 9: p. 960. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A., et al., Characterization of Glossy1-homologous genes in rice involved in leaf wax accumulation and drought resistance. Plant Mol Biol, 2009. 70(4): p. 443-56. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., An ethylene response factor OsWR1 responsive to drought stress transcriptionally activates wax synthesis related genes and increases wax production in rice. Plant Mol Biol, 2012. 78(3): p. 275-88. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z., et al., Yellow-Leaf 1 encodes a magnesium-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester cyclase, involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis in rice (Oryza sativa L.). PLoS One, 2017. 12(5): p. e0177989. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. and B. Zhang, MicroRNAs in control of plant development. Journal of cellular physiology, 2016. 231(2): p. 303-313. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., RICE CENTRORADIALIS 1, a TFL1-like Gene, Responses to Drought Stress and Regulates Rice Flowering Transition. Rice (N Y), 2020. 13(1): p. 70. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., et al., Mutations in the F-box gene LARGER PANICLE improve the panicle architecture and enhance the grain yield in rice. Plant biotechnology journal, 2011. 9(9): p. 1002-1013. [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T., Phytohormones and rice crop yield: strategies and opportunities for genetic improvement. Transgenic Res, 2006. 15(4): p. 399-404. [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, A., et al., Two WUSCHEL-related homeobox genes, narrow leaf2 and narrow leaf3, control leaf width in rice. Plant Cell Physiol, 2013. 54(5): p. 779-92. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., et al., Identification and characterization of NARROW AND ROLLED LEAF 1, a novel gene regulating leaf morphology and plant architecture in rice. Plant Molecular Biology, 2010. 73(3): p. 283-292. [CrossRef]

- Sonah, H., et al., Molecular mapping of quantitative trait loci for flag leaf length and other agronomic traits in rice (Oryza sativa). Cereal Research Communications, 2012. 40(3): p. 362-372. [CrossRef]

- Miura, K., et al., OsSPL14 promotes panicle branching and higher grain productivity in rice. Nat Genet, 2010. 42(6): p. 545-9. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., et al., OsSPL9 Regulates Grain Number and Grain Yield in Rice. Front Plant Sci, 2021. 12: p. 682018. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D., et al., Wax Crystal-Sparse Leaf1 encodes a β–ketoacyl CoA synthase involved in biosynthesis of cuticular waxes on rice leaf. Planta, 2008. 228(4): p. 675-685. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y., et al., Overexpression of a MYB Family Gene, OsMYB6, Increases Drought and Salinity Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Rice. Front Plant Sci, 2019. 10: p. 168. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, J., et al., Identification of 33 rice aquaporin genes and analysis of their expression and function. Plant and Cell Physiology, 2005. 46(9): p. 1568-1577. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., et al., Identification and functional characterization of a rice NAC gene involved in the regulation of leaf senescence. BMC Plant Biology, 2013. 13: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Matsukura, S., et al., Comprehensive analysis of rice DREB2-type genes that encode transcription factors involved in the expression of abiotic stress-responsive genes. Molecular Genetics and Genomics, 2010. 283: p. 185-196. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y., et al., Characterization of OsbZIP23 as a key player of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family for conferring abscisic acid sensitivity and salinity and drought tolerance in rice. Plant physiology, 2008. 148(4): p. 1938-1952. [CrossRef]

- Wu, R., et al., CFL1, a WW Domain Protein, Regulates Cuticle Development by Modulating the Function of HDG1, a Class IV Homeodomain Transcription Factor, in Rice and Arabidopsis The Plant Cell, 2011. 23(9): p. 3392-3411. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T., et al., Mutations in the rice OsCHR4 gene, encoding a CHD3 family chromatin remodeler, induce narrow and rolled leaves with increased cuticular wax. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2019. 20(10): p. 2567. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S., et al., A key ABA catabolic gene, OsABA8ox3, is involved in drought stress resistance in rice. PLoS One, 2015. 10(2): p. e0116646. [CrossRef]

- Jardim-Messeder, D., et al., Stromal Ascorbate Peroxidase (OsAPX7) Modulates Drought Stress Tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa). Antioxidants, 2023. 12(2): p. 387. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-W., et al., Overexpression of the trehalose-6-phosphate synthase gene OsTPS1 enhances abiotic stress tolerance in rice. Planta, 2011. 234(5): p. 1007-1018. [CrossRef]

- Cabangon, R.J., et al., Effect of irrigation method and N-fertilizer management on rice yield, water productivity and nutrient-use efficiencies in typical lowland rice conditions in China. Paddy and Water Environment, 2004. 2(4): p. 195-206. [CrossRef]

- He, Q., et al., Released control of vapor pressure deficit on rainfed rice evapotranspiration responses to extreme droughts in the subtropical zone. Plant and Soil, 2024: p. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M., D.J. Mackill, and K.T. Ingram, Inheritance of Leaf Epicuticular Wax Content in Rice. Crop Science, 1992. 32(4): p. 865-868. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., et al., Comparison of Agronomic and Physiological Characteristics for Rice Varieties Differing in Water Use Efficiency under Alternate Wetting and Drying Irrigation. Agronomy, 2024. 14(9): p. 1986. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., et al., Biodegradable film mulching reduces the climate cost of saving water without yield penalty in dryland rice production. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2023. 197: p. 107071. [CrossRef]

- Malumpong, C., et al., Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD) in broadcast rice (Oryza sativa L.) management to maintain yield, conserve water, and reduce gas emissions in Thailand. Agricultural Research, 2021. 10: p. 116-130. [CrossRef]

- Omasa, K., et al., 3D Confocal laser scanning microscopy for the analysis of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of chloroplasts in intact leaf tissues. Plant Cell Physiol, 2009. 50(1): p. 90-105. [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y., et al., Improving the performance in crop water deficit diagnosis with canopy temperature spatial distribution information measured by thermal imaging. Agricultural Water Management, 2021. 246: p. 106699. [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G., et al., Thermal infrared imaging of crop canopies for the remote diagnosis and quantification of plant responses to water stress in the field. Functional Plant Biology, 2009. 36(11): p. 978-989. [CrossRef]

- Mathers, A.W., et al., Investigating the microstructure of plant leaves in 3D with lab-based X-ray computed tomography. Plant Methods, 2018. 14: p. 99. [CrossRef]

- Van As, H., Intact plant MRI for the study of cell water relations, membrane permeability, cell-to-cell and long distance water transport. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2007. 58(4): p. 743-756.

- Gotarkar, D., et al., High-Throughput Analysis of Non-Photochemical Quenching in Crops Using Pulse Amplitude Modulated Chlorophyll Fluorometry. J Vis Exp, 2022(185): p. e63485.

- Baker, N.R., Chlorophyll fluorescence: a probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol., 2008. 59(1): p. 89-113. [CrossRef]

- Thorp, K.R., et al., High-throughput phenotyping of crop water use efficiency via multispectral drone imagery and a daily soil water balance model. Remote Sensing, 2018. 10(11): p. 1682. [CrossRef]

- Langstroff, A., et al., Opportunities and limits of controlled-environment plant phenotyping for climate response traits. Theor Appl Genet, 2022. 135(1): p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Fullana-Pericàs, M., et al., High-throughput phenotyping of a large tomato collection under water deficit: Combining UAVs’ remote sensing with conventional leaf-level physiologic and agronomic measurements. Agricultural Water Management, 2022. 260: p. 107283. [CrossRef]

- Berni, J.A., et al., Thermal and narrowband multispectral remote sensing for vegetation monitoring from an unmanned aerial vehicle. IEEE Transactions on geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2009. 47(3): p. 722-738. [CrossRef]

- Asaari, M.S.M., et al., Non-destructive analysis of plant physiological traits using hyperspectral imaging: A case study on drought stress. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2022. 195: p. 106806. [CrossRef]

- Omasa, K., F. Hosoi, and A. Konishi, 3D lidar imaging for detecting and understanding plant responses and canopy structure. J Exp Bot, 2007. 58(4): p. 881-98. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., et al., Effects of Water Isotope Composition on Stable Isotope Distribution and Fractionation of Rice and Plant Tissues. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2024. 72(16): p. 8955-8962. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., et al., Evaluation of water-use efficiency in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) using visible-near infrared and thermal spectral sensing techniques. Talanta, 2016. 152: p. 531-9. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bueno, M.L., M. Pineda, and M. Barón, Phenotyping plant responses to biotic stress by chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Frontiers in plant science, 2019. 10: p. 477268. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H. and M. Baranska, Identification and quantification of valuable plant substances by IR and Raman spectroscopy. Vibrational Spectroscopy, 2007. 43(1): p. 13-25. [CrossRef]

- Rathnasamy, S.A., et al., Altering Stomatal Density for Manipulating Transpiration and Photosynthetic Traits in Rice through CRISPR/Cas9 Mutagenesis. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 2023. 45(5): p. 3801-3814. [CrossRef]

- Kosová, K., et al., Drought stress response in common wheat, durum wheat, and barley: transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, physiology, and breeding for an enhanced drought tolerance. Drought stress tolerance in plants, vol 2: molecular and genetic perspectives, 2016: p. 277-314.

- Sharma, N., et al., Data-driven approaches to improve water-use efficiency and drought resistance in crop plants. Plant Sci, 2023. 336: p. 111852. [CrossRef]

- Mo, X., et al., Prediction of crop yield, water consumption and water use efficiency with a SVAT-crop growth model using remotely sensed data on the North China Plain. Ecological Modelling, 2005. 183(2-3): p. 301-322. [CrossRef]

- Araus, J.L. and J.E. Cairns, Field high-throughput phenotyping: the new crop breeding frontier. Trends in plant science, 2014. 19(1): p. 52-61. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., et al., Comparative transcriptome sequencing of tolerant rice introgression line and its parents in response to drought stress. BMC genomics, 2014. 15: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.K., et al., Comparative analysis of drought-responsive transcriptome in Indica rice genotypes with contrasting drought tolerance. Plant biotechnology journal, 2011. 9(3): p. 315-327.

- Chung, P.J., et al., Transcriptome profiling of drought responsive noncoding RNAs and their target genes in rice. BMC Genomics, 2016. 17(1): p. 563. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., et al., Advances in crop proteomics: PTMs of proteins under abiotic stress. Proteomics, 2016. 16(5): p. 847-865. [CrossRef]

- Lawas, L.M.F., et al., Metabolic responses of rice cultivars with different tolerance to combined drought and heat stress under field conditions. GigaScience, 2019. 8(5). [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., et al., Transcriptome profiling of two rice genotypes under mild field drought stress during grain-filling stage. AoB PLANTS, 2021. 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Zargar, S.M., et al., Physiological and multi-omics approaches for explaining drought stress tolerance and supporting sustainable production of rice. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2022. 12: p. 803603. [CrossRef]

- Roy, N., P. Debnath, and H.S. Gaur, Adoption of Multi-omics Approaches to Address Drought Stress Tolerance in Rice and Mitigation Strategies for Sustainable Production. Molecular Biotechnology, 2025: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J., et al., Integrating multi-source data for rice yield prediction across China using machine learning and deep learning approaches. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2021. 297: p. 108275. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., et al., Detection of epistatic and gene-environment interactions underlying three quality traits in rice using high-throughput genome-wide data. BioMed Research International, 2015. 2015(1): p. 135782.

- Bouman, B.A., et al., Rice: feeding the billions. 2007.

- Singh, N., D. Patel, and G. Khalekar, Methanogenesis and methane emission in rice/paddy fields. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 33: Climate Impact on Agriculture, 2018: p. 135-170.

- IRRI. Rice to zero hunger. 2019 2023.10.05]; Available from: https://www.irri.org/world-food-day-2019-rice-zero-hunger.

- Siopongco, J.D., et al., Stomatal responses in rainfed lowland rice to partial soil drying; evidence for root signals. Plant Production Science, 2008. 11(1): p. 28-41. [CrossRef]

| Omics Level | Key Technologies |

Applications to WUE |

Notable Findings |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | GWAS, QTL mapping, CRISPR-Cas9, Transgenic overexpression | Identification of genomic regions associated with WUE; Targeted gene editing of stomatal regulators | Transgenic overexpression and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of the OsEPF1 gene in rice have been shown to significantly reduce stomatal density, leading to improved drought tolerance and altered photosynthetic performance. These findings highlight OsEPF1 as a key regulator of WUE. | [33,89,154] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-Seq, microarray analysis, RT-qPCR | Profiling gene expression networks under drought; Comparative transcriptome profiling of drought-tolerant and sensitive rice genotypes; Identification of drought-responsive noncoding RNAs and their regulatory targets | Transcriptome analysis revealed hundreds of drought-responsive genes, including OsDREB2A and OsLEA3, which are key regulators in ABA-mediated drought response pathways, 66 miRNAs and 98 lncRNAs were differentially expressed under drought; miR171f-5p targeted Os03g0828701-00, suggesting a role in drought adaptation. | [159,160,161] |

| Proteomics | LC-MS/MS, iTRAQ, 2D-electrophoresis | Identification of drought-responsive proteins; Analysis of PTMs during water deficit | Over 2000 proteins were detected in rice leaves under drought; 42 showed significant changes. Key drought-responsive proteins included actin depolymerizing factor, S-like ribonuclease, and chloroplastic dehydroascorbate reductase. PTMs such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and glycosylation modulate protein function under drought, contributing to stress tolerance. | [161,162] |

| Metabolomics | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR spectroscopy | Profiling of osmoprotectants and secondary metabolites under water stress, identifying antioxidant compounds that enhance WUE. | Flag leaves exhibited cultivar-specific increases in proline, sucrose, and malate under combined drought and heat stress. Overaccumulation of flavonoids, such as kaempferol and quercetin, enhances drought and UV tolerance by reducing oxidative damage, overexpressing Flavanone 3-Hydroxylase showed higher kaempferol and quercetin levels, lower ROS and salicylic acid, and upregulated expression of DHN and UVR8 genes. | [64,163,164] |

| Phenomics | Thermal imaging, hyperspectral analysis, chlorophyll fluorescence, LiDAR | High-throughput field screening; Non-invasive measurement of physiological traits | Thermal imaging improves detection of crop water deficit by capturing spatial canopy temperature variations, enabling non-invasive and real-time assessment of plant responses to drought stress under field conditions, 3D LiDAR enables precise canopy structure analysis linked to stomatal function and transpiration. | [138,139,148,149] |

| Integrative Multi-Omics | Network analysis, systems biology, machine learning | Integration of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data; Predictive modeling of WUE traits | Multi-omics integration revealed gene, protein, and metabolite interactions enhancing drought tolerance, highlighting the potential of big-omics data to breed drought-resilient rice with improved WUE under climate change. Multi-omics integration provides a holistic view of biological responses to drought stress. Enables identification and manipulation of genes linked to drought tolerance, | [165,166,167] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).