1. Introduction

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is a well-established mechanism for generating genetic variability in bacteria [

1]. Most documented cases involve gene transfers between bacterial species, whereas reports of HGT from eukaryotes to bacteria are far less common. This scarcity is expected, given the substantial genetic incompatibilities between such evolutionarily distinct groups. Interestingly, despite these incompatibilities, interdomain HGT from bacteria to eukaryotes is frequently reported in the scientific literature. This is surprising, as eukaryotic genomes possess multiple barriers that could hinder interkingdom HGT, including differences in gene promoter recognition, intron processing, codon usage bias, and the presence of a nucleus that encapsulates genetic material [

2]. In fungi specifically, the acquisition of foreign genetic material may trigger meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA, further complicating the successful integration of horizontally transferred genes [

3].

The recent surge in reported cases of interdomain HGT in the scientific literature [

4,

5,

6,

7] may create the impression that this phenomenon is widespread in eukaryotic evolution. For instance, Côté-L'Heureux et al. [

8] identified 306 interdomain HGT events in eukaryotes, while Kwak et al. [

5] reported at least seven bacterial-derived genes in the genome of the psyllid

Bactericera cockerelli. Lai et al. [

9] found 161 orthogroups acquired by nematodes from various kingdoms, particularly bacteria. Liu et al. [

6] analyzed 750 fungal genes and identified 20,093 prokaryotic-derived genes. Additionally, Katz [

4] conducted a comprehensive study on the presence of HGT and endosymbiotic gene transfer (EGT) across major eukaryotic clades, reporting 1,138 candidate genes potentially transferred from bacteria to eukaryotes. This analysis was based on 487 eukaryotic genomes, along with 303 bacterial and 118 archaeal genomes. Given this extensive dataset, it appears that interkingdom HGT has played a role in eukaryotic evolution. However, the actual impact of this process remains a topic of ongoing debate [

10,

11,

12]. Aguirre-Carvajal et al. [

10] suggest that as genomic databases expand, the number of interdomain HGT cases reported tends to decline, highlighting the need for a continued reassessment of this phenomenon.

To evaluate this premise, we updated the dataset presented by Katz (2015) on the prevalence of interdomain lateral gene transfer between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. We conducted a phylogenetic analysis to identify topologies consistent with interdomain HGT. For a fair comparison, we adhered to the criteria established in the original study to distinguish valid from invalid candidates. Our goal was to assess the impact of reevaluating interdomain HGT candidates in light of newly available genomic data.

2. Results

Katz (2015) reported 1,138 interdomain HGT candidates in eukaryotes, involving transfers between three major clades (3MC) to a single major clade (1MC). In this study, we reanalyzed only the 638 candidates classified as 1MC. We focused on these cases because when multiple major clades are involved, it becomes difficult to distinguish between true interdomain HGT and the alternative scenario of ancestral gene presence in eukaryotes, followed by differential gene loss across lineages.

In other words, if a gene of bacterial origin is found in two or more major eukaryotic clades, this pattern suggests that the transfer may have occurred in their last common ancestor—possibly close to the base of the eukaryotic tree—and was later lost in most descendant lineages. However, an equally plausible explanation is that the gene was inherited vertically from the eukaryotic ancestor and subsequently lost independently in multiple lineages. Between these two possibilities, the hypothesis of ancestral gene loss is more parsimonious, as it does not require invoking a HGT at the root of eukaryotes. Additionally, inferring ancient interdomain HGT from a single gene tree is highly speculative.

Therefore, we consider that transfers to a single MC are more reliably detected when homologs are absent from the remaining eukaryotic MCs. To ensure a fair comparison, we followed the same taxonomic classification and coding scheme used in Katz (2015), maintaining consistency in defining major clades (MC) and minor clades (mc) (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Taxonomic groups and corresponding codes used in the analysis of interdomain horizontal gene transfer events.

Table 1.

Taxonomic groups and corresponding codes used in the analysis of interdomain horizontal gene transfer events.

| Major clade (MC) |

Minor clade (mc) |

code (MC_mc) |

| Amoebozoa |

Archamoebae |

Am_ar |

| Amoebozoa |

Dictyostelia |

Am_di |

| Amoebozoa |

Amoebozoa incertae sedis |

Am_is |

| Amoebozoa |

Eumycetozoa |

Am_my |

| Orphan groups |

Cryptophyceae |

EE_cr |

| Orphan groups |

Haptophyta |

EE_ha |

| Orphan groups |

Others |

EE_ot |

| Excavata |

Euglenozoa |

Ex_eu |

| Excavata |

Fornicata |

Ex_fo |

| Excavata |

Heterolobosea |

Ex_he |

| Excavata |

Jakobida |

Ex_ja |

| Excavata |

Others |

Ex_ot |

| Excavata |

Parabasalia |

Ex_pa |

| Opisthokonta |

Choanoflagellata |

Op_ch |

| Opisthokonta |

Fungi |

Op_fu |

| Opisthokonta |

Metazoa |

Op_me |

| Opisthokonta |

Others |

Op_ot |

| Archaeplastida (Plantae) |

Glaucocystophyceae |

Pl_gl |

| Archaeplastida (Plantae) |

Viridiplantae |

Pl_gr |

| Archaeplastida (Plantae) |

Rhodophyta |

Pl_rh |

| SAR (Stramenopila, Alveolata, Rhizaria) |

Apicomplexa |

Sr_ap |

| SAR (Stramenopila, Alveolata, Rhizaria) |

Ciliophora |

Sr_ci |

| SAR (Stramenopila, Alveolata, Rhizaria) |

Dinophyceae |

Sr_di |

| SAR (Stramenopila, Alveolata, Rhizaria) |

Rhizaria |

Sr_rh |

| SAR (Stramenopila, Alveolata, Rhizaria) |

Stramenopiles |

Sr_st |

As a result of reevaluating the HGT candidates identified by Katz (2015), we observed a substantial shift in findings after 10 years of additional data (

Table 2). Of the 638 candidates analyzed, 82 exhibited tree topologies consistent with interdomain HGT, though 8 of these were more accurately classified as endosymbiotic gene transfer (EGT). A total of 454 candidates were categorized as non-HGT, while 119 sequences were identified as potential contaminants. Additionally, 28 candidates remained inconclusive based on phylogenetic analysis.

Among the 454 candidates determined to be incongruent with interdomain HGT, we identified two primary patterns: (1) the emergence of new major clades not included in the original analysis (262 candidates), and (2) a lack of sufficient prokaryotic homologs in BLASTp searches (192 candidates). The absence of prokaryotic sequences in BLAST results is largely due to the overwhelming number of eukaryotic sequences displaying similarity to the query. In both cases, these findings can be attributed to the increased availability of homologous sequences in genomic databases. The phylogenetic trees and multiple sequence alignments supporting our results are available in the Zenodo repository (

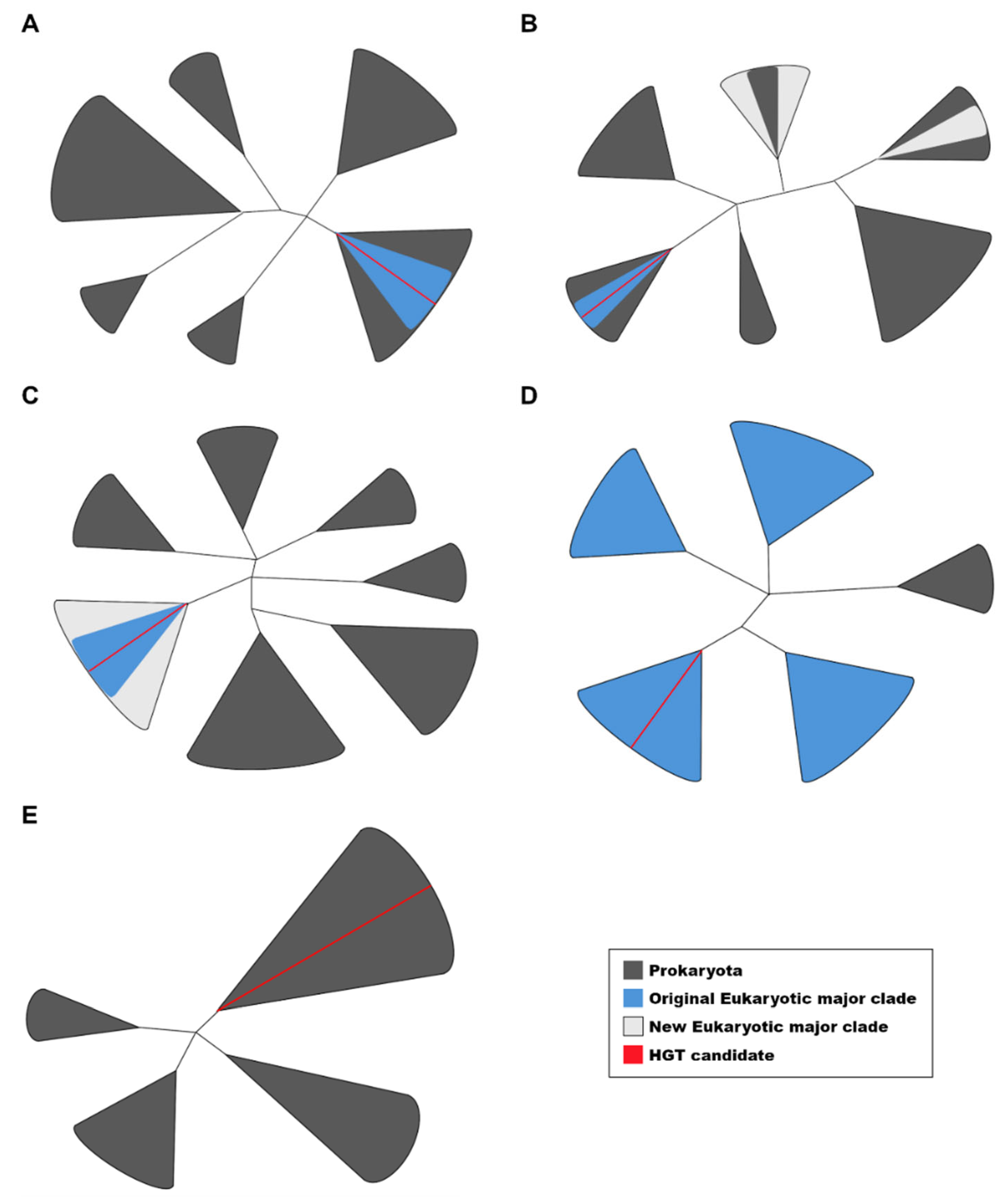

https://zenodo.org/records/15091048), and a schematic representation of the observed phylogenetic patterns is provided in

Figure 1.

Table 2.

Outcomes of the reassessment of HGT candidates from Katz (2015).

Table 2.

Outcomes of the reassessment of HGT candidates from Katz (2015).

| Classification |

Number of candidates |

| HGT pattern |

82 |

| Inconclusive phylogenetic evidence for HGT |

28 |

| No HGT– New MC emerge in the search |

262 |

| No HGT– A limited presence of prokaryotic sequences to suggest an HGT scenario |

192 |

| Potential contamination |

119 |

| Total |

683 |

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the phylogenetic patterns observed in this study. (A) Candidates forming a monophyletic group with homologs of the same major clade (1MC) surrounded by prokaryotic sequences. (B) Candidates with newly identified homologs in different MCs but not forming a monophyletic clade. (C) Candidates with newly identified homologs in different MCs that do form a monophyletic clade. (D) Candidates with only a few homologs detected in prokaryotes. (E) Candidates without any detectable eukaryotic homologs, which were tested for potential contamination. Patterns A and B were classified as interdomain HGT candidates based on the criteria used in this study. The figures are represented as unrooted trees with collapsed branches.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the phylogenetic patterns observed in this study. (A) Candidates forming a monophyletic group with homologs of the same major clade (1MC) surrounded by prokaryotic sequences. (B) Candidates with newly identified homologs in different MCs but not forming a monophyletic clade. (C) Candidates with newly identified homologs in different MCs that do form a monophyletic clade. (D) Candidates with only a few homologs detected in prokaryotes. (E) Candidates without any detectable eukaryotic homologs, which were tested for potential contamination. Patterns A and B were classified as interdomain HGT candidates based on the criteria used in this study. The figures are represented as unrooted trees with collapsed branches.

Species Availability and Interdomain HGT Detection

This study aims to assess whether the expansion of genomic databases influences the number of detectable interdomain HGT candidates.

Table 3 compares the HGT candidates identified by Katz (2015) with those found in this study, alongside the species representation in both datasets.

Table 3.

Comparison of HGT candidate identification and species representation across major clades in different datasets.

Table 3.

Comparison of HGT candidate identification and species representation across major clades in different datasets.

| MC |

Katz_sp |

HGT |

NCBI_sp |

stillHGT |

p_adjust |

odds_ratio |

| Amoebozoa |

14 |

30 |

58 |

17 |

8.7x10-4

|

7.31 |

| Archaeplastida |

85 |

144 |

2345 |

23 |

2.61x10-27

|

172.73 |

| Excavata |

37 |

34 |

112 |

9 |

1.98x10-6

|

11.44 |

| Opisthokonta |

106 |

281 |

14820 |

21 |

2.34x10-57

|

1870.81 |

| SAR |

184 |

47 |

608 |

12 |

1.51x10-8

|

12.94 |

We observed significant differences in the number of interdomain HGT candidates between Katz (2015) and our reassessment of the same dataset. The most pronounced reductions were found in Opisthokonta (p = 2.34 × 10⁻⁵⁷), where the number of HGT candidates decreased from 281 in Katz’s study to 21 in ours, and in Archaeplastida (p = 2.61 × 10⁻²⁷), where candidates dropped from 144 to 23. Other major reductions were observed in Amoebozoa (p = 8.7 × 10⁻⁴), SAR (p = 1.51 × 10⁻⁸), and Excavata (p = 1.98 × 10⁻⁶), with HGT candidates decreasing from 30 to 17, 47 to 12 in SAR, and 34 to 9, respectively. Additionally, all candidates previously identified as belonging to orphan groups by Katz (2015) were classified as potential contaminants in this study and were therefore excluded from all analyses.

Interestingly, the odds ratios reveal a significantly higher probability of detecting HGT candidates in Katz’s dataset compared to the current NCBI dataset (

Table 3). For example, in Opisthokonta, the probability of identifying HGT candidates is 1,870 times higher in Katz’s dataset. In other major clades, the odds ratios range from 7 to 172, consistently indicating a greater probability of detecting HGT candidates in Katz’s dataset.

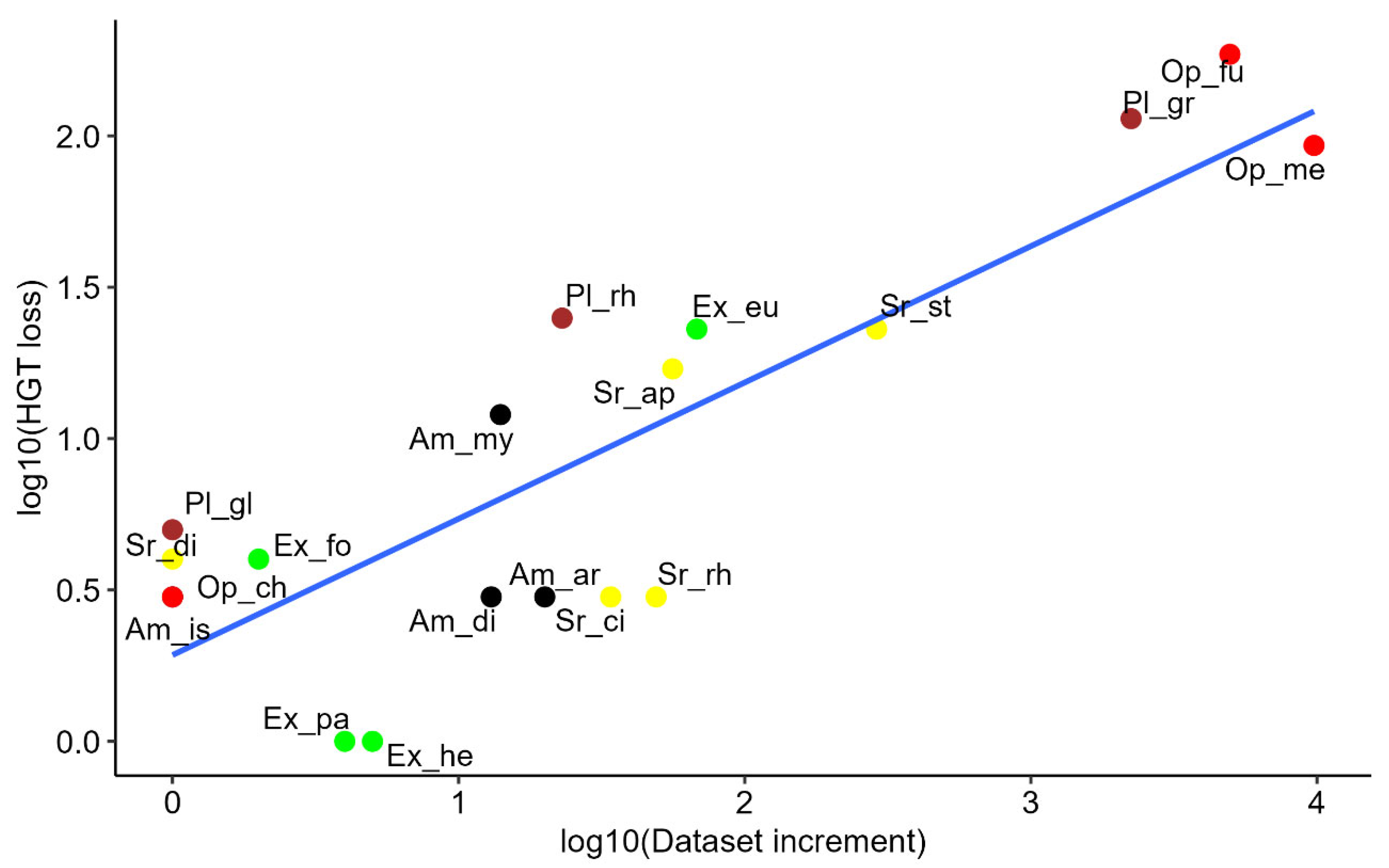

A Spearman’s rank correlation test showed a strong, statistically significant positive correlation between the increase in database size and the number of HGT candidate losses (rho = 0.66, p = 2 × 10⁻³), as illustrated in

Figure 2. This finding suggests that as database size expands, the chance of detecting interdomain HGT cases decreases, highlighting the critical influence of database composition on HGT detection.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot illustrating the relationship between HGT loss (HGT – stillHGT) and dataset expansion (NCBI_sp – Katz_sp) on a log10 scale. Data points are labeled according to minor clades (

Table 1) and color-coded by major clades: Opisthokonta (red), Excavata (green), SAR (yellow), Amoebozoa (black), and Archaeplastida (brown). The data used to generate this figure can be found in

Table S2.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot illustrating the relationship between HGT loss (HGT – stillHGT) and dataset expansion (NCBI_sp – Katz_sp) on a log10 scale. Data points are labeled according to minor clades (

Table 1) and color-coded by major clades: Opisthokonta (red), Excavata (green), SAR (yellow), Amoebozoa (black), and Archaeplastida (brown). The data used to generate this figure can be found in

Table S2.

Our findings indicate that datasets with limited species representation can lead to an overestimation of HGT candidate detections. In contrast, as species coverage improves in more comprehensive datasets, this overestimation is significantly reduced. In the expanded database, newly identified homologs led to the exclusion of several previously proposed HGT candidates that no longer supported the HGT hypothesis. These results highlight the critical importance of thorough homolog identification before classifying interdomain HGT candidates.

3. Discussion

In this study, we reassessed the interdomain HGT cases reported by Katz (2015) in light of a decade of newly available genomic data. Our analysis revealed significant differences, with only 82 out of the 683 originally proposed HGT candidates (involving a single major clade) remaining valid. The primary factor behind this reduction was the identification of new homologs in different major clades, prompting a reevaluation of the plausibility of these sequences as interdomain HGT candidates. Our findings present a contrasting picture to that described by Katz (2015), indicating that evidence for bacterial-to-eukaryote HGT is limited. Moreover, the identification of interdomain HGT candidates appears to be strongly influenced by the availability of homologous sequences.

Our findings align with the conclusions of Aguirre-Carvajal

et al. [

10,

13] and the ideas proposed by Martin [

12]. Furthermore, the observed limited occurrence of lateral gene transfer in eukaryotes is consistent with the known biological barriers that prevent the integration of foreign genetic material [

2]. Despite this, numerous studies have reported interdomain HGT cases in the scientific literature [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

14]. Huang [

15] explored in detail the mechanisms by which these barriers might be bypassed, potentially explaining the high number of reported interdomain HGT events.

Given this apparent contradiction, interdomain HGT in eukaryotes remains a highly debated topic [

11,

12,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. However, its impact on eukaryotic genomes is an important and unresolved question that warrants further investigation. Katz (2015) made a significant effort to quantify interdomain HGT in eukaryotes, yet with the continuous expansion of genomic data, all reported prokaryote-to-eukaryote HGT cases require reassessment.

Notably, Katz (2015) applied this same rationale when reevaluating the HGT cases reported by Becker et al. [

22], which described gene transfers from Chlamydiae to Archaeplastida. Upon reanalysis, only two of the original 38 cases were validated. Similarly, Katz identified new homologs in different major clades for a previously claimed synapomorphy in Opisthokonta (tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase) [

23]. Our study observes the same pattern in the reassessment of Katz’s HGT candidates, reinforcing the notion that HGT cases must be continuously reevaluated due to increasing database sizes.

This leads to the conclusion that the process of reexamining HGT candidates will be ongoing and perpetual, as new genomic data are continuously incorporated into databases, introducing potential homologs that challenge previously proposed HGT events. This perspective directly questions the prediction made by Katz (2015): “we anticipate that even more recent events will be found as taxon sampling expands, particularly in poorly sampled territories like much of the Excavata and Rhizaria.” In contrast, our revision validated only 9 of the 36 originally proposed HGT candidates in Excavata and none in Rhizaria.

This study highlights how the discovery of new homologs can reshape our understanding of interdomain HGT candidates and their evolutionary histories. It is crucial to periodically reassess the frequency and significance of interdomain HGT in eukaryotes as genomic databases continue to expand. One of the most critical factors to consider before designating a sequence as an HGT candidate is the potential absence of homologs in databases—not necessarily due to evolutionary loss, but simply because they have yet to be documented. Given this limitation, confidently asserting an HGT event is challenging when many species remain unsampled. If a eukaryotic sequence appears to have homologs only in bacteria, it is prudent to anticipate that future genomic studies may uncover additional eukaryotic homologs. Moreover, the frequent detection of bacterial matches is expected due to the vast number of bacterial genomes currently available in databases. Following this reasoning, even the 82 interdomain HGT candidates we validated in this study may be subject to future reevaluation as new data emerge, potentially leading to further revisions and reductions in the number of candidates initially proposed by Katz (2015).

Phylogenetic reconstruction comes with inherent limitations, especially when attempting to infer ancient events such as many of the proclaimed interdomain HGTs. The challenges in detecting HGT extend beyond the absence of homologs; factors like incomplete lineage sorting, inaccuracies in sequence evolution models, hidden paralogy, hybridization, recombination, and natural selection can all lead to incongruent gene trees [

24]. Consequently, the presence of an anomalous phylogeny should not be automatically interpreted as evidence of HGT, particularly in eukaryotes. Given these constraints, relying solely on single-gene trees to detect interdomain HGT may be premature. Alternative evolutionary scenarios must be considered alongside horizontal transfer hypotheses. In this study, we employed a phylogenetic approach to identify interdomain HGT candidates, validating only those topologies most consistent with lateral gene transfer. However, we acknowledge that other factors—such as extensive lineage-specific gene loss or the absence of homologs in current databases—could also explain the observed phylogenetic patterns.

4. Materials and Methods

Katz (2015) established two key criteria for identifying interdomain HGT candidates: (1) the presence of homologs in at least one (1MC) and at most three (3MC) major eukaryotic clades, and (2) the monophyly of eukaryotic sequences within phylogenetic trees. In our study, we applied the same criteria but focused exclusively on the 1MC candidates (683 sequences). We excluded 2MC and 3MC candidates, as their patterns could be more parsimoniously explained by lineage-specific gene loss rather than interdomain HGT. We consider candidates with homologs found in two or more major clades—particularly when forming a monophyletic branch in the phylogenetic tree—as unreliable indicators of HGT. Accordingly, in our subsequent reanalysis of 683 candidates, we excluded those that exhibited this pattern. Furthermore, we did not reassess the candidates originally classified as 2MC or 3MC in Katz (2015).For each of the 683 candidates, homolog searches were performed using DIAMOND BLASTp v2.1.9 [

25] with the parameter --max-target-seq 200, querying the NCBI non-redundant (NR) database (updated on January 20

th, 2025). The minor clade classification of each query sequence is provided in

Table S3. The BLAST results were taxonomically annotated using TAXONKIT v0.15.0 [

26], mapping taxonomic identifiers (TaxIds) to their respective organisms. A candidate was flagged as potential contamination if its top BLAST hit belonged to a prokaryote or if the highest-scoring eukaryotic hit was followed exclusively by bacterial hits. To refine the dataset further, additional analyses included retrieving the contig of the query sequence and conducting NCBI Online BLASTp (v2.13.0, accessed on March 2

th, 2025;

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), searches on upstream and downstream translated genes to assess whether surrounding genes were of bacterial origin.

For sequences that passed the contamination filtering step, a topology analysis was performed using the AVP v1.0.10 tool [

27] in IQ-TREE mode to classify candidates as potential HGT events. Identifying potential HGT required the candidate sequence, BLAST search results, and two taxonomic labels: the ingroup and the exclusion group parameter (EGP). The ingroup represents the taxonomic group where vertical gene transfer is expected, serving as a reference to identify potential HGT donors from outside this group. The EGP defines the taxonomic group containing the candidate sequence, which is excluded from the analysis, and specifies the group where horizontal transfer is presumed to have occurred. The ingroups and EGPs used in this study are provided in

Table S4.

A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis was then conducted to validate the AVP results. Homologous sequences were selected from the BLAST results based on the criteria of >30% pairwise identity, >60% query coverage, and an e-value threshold of <1×10⁻⁵. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using MAFFT v7.520 [

28] in auto mode, followed by refinement with Gblocks v0.91b [

29] to eliminate poorly aligned regions. The alignments were then converted into PHYLIP format, and ModelTest-NG v0.1.7 [

30] was used to determine the best-fit model for constructing phylogenetic trees. The final trees were generated using PhyML v3.3.20220408 [

31] with Shimodaira–Hasegawa support values used to asses branch support. Each tree was annotated in NEXUS format using a custom Python v3.10.12 script, incorporating taxonomic information from GenBank records corresponding to the sequences in the phylogeny. Finally, the trees were manually examined in Geneious Prime 2023.2.1 (

https://www.geneious.com, accessed March 17

th, 2025) to identify potential instances of HGT.

We considered as HGT candidates those cases where phylogenetic trees displayed monophyletic eukaryotic clades (within the same major clade) surrounded by prokaryotic sequences (see

Figure 1). We also classified as HGT candidates sequences those that formed monophyletic clades with homologs from the same major clade, even if homologs from other major clades were present but did not cluster within the same branch of the tree. In other words, when new eukaryotic homologs were identified, the HGT candidate was reassessed through phylogenetic analysis. We applied criteria equivalent to those used by Katz, maintaining sequences as HGT candidates if homologs were found in one or more minor clades but remained restricted to a single major clade. However, candidates were excluded if the updated search revealed homologs in two or more major clades that formed a monophyletic group in the phylogenetic tree.

We conducted a statistical analysis to evaluate whether the increase in species representation in genomic databases influences HGT detection. To assess species representation in NCBI’s NR database, we utilized the NCBI Datasets tool (v16.43.0, accessed on February 20

th, 2025;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/) along with the NCBI search engine (accessed on February 20

th, 2025;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) to compile available genomic information. Species counts from Katz’s study were obtained from

Supplementary Table S1 of the original publication [

4]. To compare HGT detection between datasets, we applied McNemar’s exact test to each minor clade and adjusted p-values using the false discovery rate method to determine statistical significance. Additionally, we calculated odds ratios to measure the likelihood of detecting HGTs in Katz’s dataset relative to the NCBI dataset for each minor clade. The odds ratio was determined by dividing the probability of identifying HGTs in Katz’s dataset by the probability of detecting them in the NCBI dataset.

where:

HGT represents the number of HGT candidates identified in Katz’s study.

Katz_sp refers to the number of species included in Katz’s dataset.

stillHGT denotes the number of HGT candidates that remain supported in our analysis.

NCBI_sp corresponds to the number of species with complete genomes available in NCBI at the time of this study.

To further investigate the relationship between the increase in species representation in genomic datasets and the reduction in HGT candidates, we applied Spearman’s rank correlation to evaluate the strength and direction of this association. All statistical analyses were performed at a 95% significance level. Candidates classified as “Potential contamination” or “Inconclusive phylogenetic evidence for HGT” were excluded from the statistical analyses.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to reassess eukaryotic interdomain HGT candidates identified by Katz (2015) a decade ago. Our reanalysis revealed a substantial reduction in the number of candidates that remain consistent with an interdomain HGT scenario, with only 12% of the examined cases still supporting this hypothesis. The expansion of genomic databases has significantly increased the likelihood of identifying eukaryotic homologs, thereby challenging many previously proposed HGT events. These findings underscore the importance of periodically reevaluating HGT candidates and exercising caution when attributing interdomain gene transfer to eukaryotes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Number of homologs identified for each 1MC interdomain HGT candidate; Table S2: Species analyzed and HGT candidates identified in Katz (2015) compared to the present study; Table S3: Minor clade assignment for each orthologous group identified as an HGT candidate in Katz (2015); Table S4: Ingroup and Exclusion Group Parameter (EGP) configurations applied in AvP for interdomain HGT candidate detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: V.A.-J.; methodology, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, and review and editing: K.A.-C. and V.A.-J.; project administration and funding acquisition: V.A.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad de Las Américas as part of the program PRG.BIO.23.14.01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Helen Pugh for proofreading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HGT |

Horizontal gene transfer |

| EGT |

Endosymbiotic gene transfer |

| MC |

Major clade |

| mc |

Minor clade |

| BLAST |

Basic local alignment search tool |

| NR |

Non-redundant |

| EGP |

Exclusion group parameter |

References

- Brito, I.L. Examining Horizontal Gene Transfer in Microbial Communities. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, D.A. Horizontal Gene Transfer in Fungi. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2011, 329, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, T.M. Sixteen Years of Meiotic Silencing by Unpaired DNA. Adv Genet 2017, 97, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, L.A. Recent Events Dominate Interdomain Lateral Gene Transfers between Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes and, with the Exception of Endosymbiotic Gene Transfers, Few Ancient Transfer Events Persist. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015, 370, 20140324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.; Argandona, J.A.; Degnan, P.H.; Hansen, A.K. Chromosomal-Level Assembly of Bactericera Cockerelli Reveals Rampant Gene Family Expansions Impacting Genome Structure, Function and Insect-Microbe-Plant-Interactions. Mol Ecol Resour 2023, 23, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, S.-H.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Zhao, R.-L. Uneven Distribution of Prokaryote-Derived Horizontal Gene Transfer in Fungi: A Lifestyle-Dependent Phenomenon. mBio 2025, 16, e0285524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, Y.; Fredman, D.; Szczesny, P.; Grynberg, M.; Technau, U. Recurrent Horizontal Transfer of Bacterial Toxin Genes to Eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol 2012, 29, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote-L’Heureux, A.; Maurer-Alcalá, X.X.; Katz, L.A. Old Genes in New Places: A Taxon-Rich Analysis of Interdomain Lateral Gene Transfer Events. PLoS Genet 2022, 18, e1010239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-K.; Lee, Y.-C.; Ke, H.-M.; Lu, M.R.; Liu, W.-A.; Lee, H.-H.; Liu, Y.-C.; Yoshiga, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Chen, P.J.; et al. The Aphelenchoides Genomes Reveal Substantial Horizontal Gene Transfers in the Last Common Ancestor of Free-Living and Major Plant-Parasitic Nematodes. Mol Ecol Resour 2023, 23, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Carvajal, K.; Munteanu, C.R.; Armijos-Jaramillo, V. Database Bias in the Detection of Interdomain Horizontal Gene Transfer Events in Pezizomycotina. Biology 2024, 13, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, C.; Martin, W.F. A Natural Barrier to Lateral Gene Transfer from Prokaryotes to Eukaryotes Revealed from Genomes: The 70 % Rule. BMC Biol 2016, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, W.F. Too Much Eukaryote LGT. Bioessays 2017, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre-Carvajal, K.; Cárdenas, S.; Munteanu, C.R.; Armijos-Jaramillo, V. Rampant Interkingdom Horizontal Gene Transfer in Pezizomycotina? An Updated Inspection of Anomalous Phylogenies. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcet-Houben, M.; Gabaldón, T. Acquisition of Prokaryotic Genes by Fungal Genomes. Trends Genet. 2010, 26, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Horizontal Gene Transfer in Eukaryotes: The Weak-Link Model. Bioessays 2013, 35, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, C.; Nelson-Sathi, S.; Roettger, M.; Garg, S.; Hazkani-Covo, E.; Martin, W.F. Endosymbiotic Gene Transfer from Prokaryotic Pangenomes: Inherited Chimerism in Eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 10139–10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, M.M.; Eme, L.; Stairs, C.W.; Roger, A.J. Demystifying Eukaryote Lateral Gene Transfer (Response to Martin 2017. Bioessays 2018, 40, e1700242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.F. Eukaryote Lateral Gene Transfer Is Lamarckian. Nat Ecol Evol 2018, 2, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boto, L. Are There Really Too Many Eukaryote LGTs? A Reply To William Martin. Bioessays 2018, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, A.J. Reply to “Eukaryote Lateral Gene Transfer Is Lamarckian. ” Nat Ecol Evol 2018, 2, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, N.; Martin, W.F.; Steel, M. The Probability of a Unique Gene Occurrence at the Tips of a Phylogenetic Tree in the Absence of Horizontal Gene Transfer (the Last-One-Out). bioRxiv 2024, 2024.01.14.575579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.; Hoef-Emden, K.; Melkonian, M. Chlamydial Genes Shed Light on the Evolution of Photoautotrophic Eukaryotes. BMC Evol Biol 2008, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Xu, Y.; Gogarten, J.P. The Presence of a Haloarchaeal Type Tyrosyl-tRNA Synthetase Marks the Opisthokonts as Monophyletic. Mol Biol Evol 2005, 22, 2142–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som, A. Causes, Consequences and Solutions of Phylogenetic Incongruence. Brief Bioinform 2015, 16, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive Protein Alignments at Tree-of-Life Scale Using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Ren, H. TaxonKit: A Practical and Efficient NCBI Taxonomy Toolkit. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2021, 48, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsovoulos, G.D.; Granjeon Noriot, S.; Bailly-Bechet, M.; Danchin, E.G.J.; Rancurel, C. AvP: A Software Package for Automatic Phylogenetic Detection of Candidate Horizontal Gene Transfers. PLoS Comput Biol 2022, 18, e1010686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, G.; Castresana, J. Improvement of Phylogenies after Removing Divergent and Ambiguously Aligned Blocks from Protein Sequence Alignments. Syst Biol 2007, 56, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Posada, D.; Kozlov, A.M.; Stamatakis, A.; Morel, B.; Flouri, T. ModelTest-NG: A New and Scalable Tool for the Selection of DNA and Protein Evolutionary Models. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020, 37, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.-F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New Algorithms and Methods to Estimate Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies: Assessing the Performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic Biology 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).