1. Introduction

Modern dentistry is experiencing a significant transformation with the growing adoption of digital technologies across diagnostics, treatment planning, and execution. Among these advancements, computer-guided implantology has emerged as a pivotal technique, especially for demanding cases such as aesthetic restorations and complete-arch rehabilitations [

1]. This method enhances surgical accuracy, reduces the likelihood of complications, improves patient comfort, and promotes workflow efficiency [

2].

The integration of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), intraoral scanning (IOS), and digital planning software enables clinicians to conduct virtual simulations that are precisely translated into clinical procedures. Surgical templates facilitate implant placement with high fidelity to the preoperative plan [

3]. However, treatment of complete-arch rehabilitation continues to be one of the most complex procedures in implant dentistry, necessitating the restoration of function, esthetics, and durability in patients who often present with compromised anatomical landmarks. Digital workflows offer individualized planning and enhance procedural control, thereby increasing treatment predictability. Moreover, intraoral scanners (IOSs) provide a rapid and non-invasive method for capturing accurate data [

4], with output quality that now competes with or even surpasses that of conventional impressions, thereby benefiting both prosthetic planning and the overall patient experience [

5]. The fusion of intraoral scans with CBCT data creates a comprehensive digital representation, often referred to as a

“digital twin,” which supports every stage from prosthetic planning to surgical guide production and anatomical assessment.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) further augments this process by analyzing large datasets to assist in diagnosis, optimize implant positioning, and evaluate biomechanical factors [

6,

7]. In clinical application, these technologies contribute to more precise implant placements, improved prosthetic outcomes, and streamlined procedures that are often less invasive, facilitating the possibility of immediate loading. Nevertheless, clinical success also hinges on implant design and the clinician

’s proficiency. Long-term research has demonstrated that implants with enhanced hydrophilicity may lead to better outcomes by accelerating osseointegration and supporting immediate loading strategies [

8]. A comprehensive understanding of digital workflows, software mechanics, and the management of edentulous patients is essential for clinicians. Guided implant surgery effectively transforms virtual planning into precise operative outcomes [

9], while three dimensional (3D)-printed surgical guides help reduce deviations and minimize tissue trauma. Consistency and accuracy at each stage—from digital impressions and guide fabrication to prosthesis delivery—are vital. Collaboration with dental laboratories, facilitated by digital communication, enables the creation of custom-designed prostheses that are virtually tested and fabricated via computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM). This enhances treatment efficiency, reduces errors, and elevates clinical quality. Ultimately, the integration of CBCT, AI, IOS, and 3D printing is driving dentistry toward a more predictive, preventive, and personalized approach. Complete-arch cases illustrate the transformative potential of this paradigm, positioning computer-guided implantology as a patient-centered model defined by accuracy, safety, and excellence [

10]. Finally, accurate digital impressions are critical for the success of complete-arch implant rehabilitations. Recent research has explored the reliability of different IOS strategies, including segmental scan and merge techniques, highlighting the potential and limitations of these methods in clinical practice [

11].

The aim of this in vitro study was to validate a novel AI-based tool for automated, real-time library alignment in all-on-X implant-supported restorations. Validation was performed by assessing the accuracy and precision of this new digital impression workflow and comparing it with conventional IOS methods. Accordingly, the first null hypothesis (H0) was that there is no differences in mean root mean square (RMS) between export and student. The second null hypothesis (H0) was that there is no differences using different scanning techniques

2. Materials and Methods

This in vitro study was conducted as a comparative analysis to evaluate the accuracy and precision of a novel digital workflow for complete-arch restorations, named SmartX (MEDIT Corp., South Korea, Seoul). All the digital impressions were taken by two operators: a final-year dental student (FDR) and an experienced clinician with over two decades of practice in digital dentistry (MT). Prior to data collection, the dental student received structured training in digital impression techniques. This included a theoretical overview, a live demonstration, and hands-on practice with the scanner under the supervision of the MT, who also performed the comparative scans to ensure consistency. In addition, the same student participated to a previously reported paper on the accuracy and precision of digital impressions using reverse scan body (RSB) prototypes and IOSs for rehabilitating fully edentulous patients [

12].

The present study utilized mandible models replicating full edentulism with simulated gingiva, specifically manufactured for implantology training purposes. These models were designed to emulate D2 bone density, incorporating dense cortical and porous trabecular structures (Dentalstore & Edizioni Lucisano SRL, Milan, Italy). A CBCT scan (Cranex 3Dx, Soredex, Tuusula, Finland) was acquired using parameters of 90 kV and 5.0 mA, with a 6 × 8 field of view and 0.2 mm resolution. The Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) data from the CBCT was subsequently superimposed with Standard Tessellation Language (STL) files generated via an optical scan (i700, Medit Corp., Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea) of the same model. A virtual diagnostic wax-up was created to guide prosthetic planning and implant positioning using dedicated planning software (Exoplan 3.1 Rijeka prototype, Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Virtual placement of four Osstem TSIII implants (4 mm diameter × 10 mm length; Osstem Implant Co., Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea) was performed using the same software, following the established protocol by Malò et al. [

13]. Additional three buccal anchor pins were planned to secure the surgical guide during implant site preparation and insertion. A fully 3D-printed surgical template, designed without metal sleeves due to compatibility with the OneGuide Kit (Osstem Implants, Seoul, Republic of Korea), was fabricated at a specialized center (New Ancorvis SRL, Bologna, Italy) using a Diret Metal Printing (DMP) Dental 100 printer and certified resin material (VisiJet M2R-CL, 3D Systems Inc., Rock Hill, SC, USA). Four dummy implants were then fully guided using a surgical template without metallic sleeves and a dedicated surgical kit (ONEGuide, Osstem Global Co., Ltd.), adhering strictly to the manufacturer's specifications. Following implant placement, multi-unit abutments and temporary cylinders (Osstem Implant Co., Ltd.,) were secured using the recommended torque settings. Finally, a temporary restoration was rebased onto the temporary cylinders (Osstem Implant Co., Ltd.,) using a resin cement (Panavia SA, Kuraray Europe GmbH, Hattersheim, Germany), with the aid of a screw-retained module, attached to the base of the template, to guide the temporary restoration at the correct vertical dimension of occlusion and centric relation. After implant placement, digital impressions were taken. Both operators recorded the digital impressions across multiple groups, including the control group and various test subgroups.

- -

In the controlgroup, a first scan of the temporary restoration was taken. After that, temporary restoration was unscrewed, four scan bodies (Osstem Implant Co., Ltd.,) were torqued at 15 Ncm using the E-Driver (Osstem Implant Co., Ltd.,), and a second digital impression was recorded. Both scans were taken using a desktop scanner (Nobil Metal SPA, Villafranca D’Asti, Italy) to serve as a reference to evaluate accuracy and precision of the other test groups.

- -

-

In the test group, six subgroups were created, with six scans taken for each subgroup—resulting in a total of 36 scans performed by the expert operator and another 36 by the student. All the digital scans were taken with Medit i900 (Medit Corp., South Korea, Seoul) scan onto the four multi-unit abutments. Subgroups are divided by scan body design / scan technique / operator / as follows:

Scan bodies featured with double-wing lateral extensions (SmartFlags, Apollo, Poland) / Occlusal scan / straight motion / SmartX tool / Expert (n=6), Student (n=6).

Scan bodies featured with double-wing lateral extensions (SmartFlags, Apollo, Poland) / Occlusal scan / straight motion / No SmartX tool / Expert (n=6), Student (n=6).

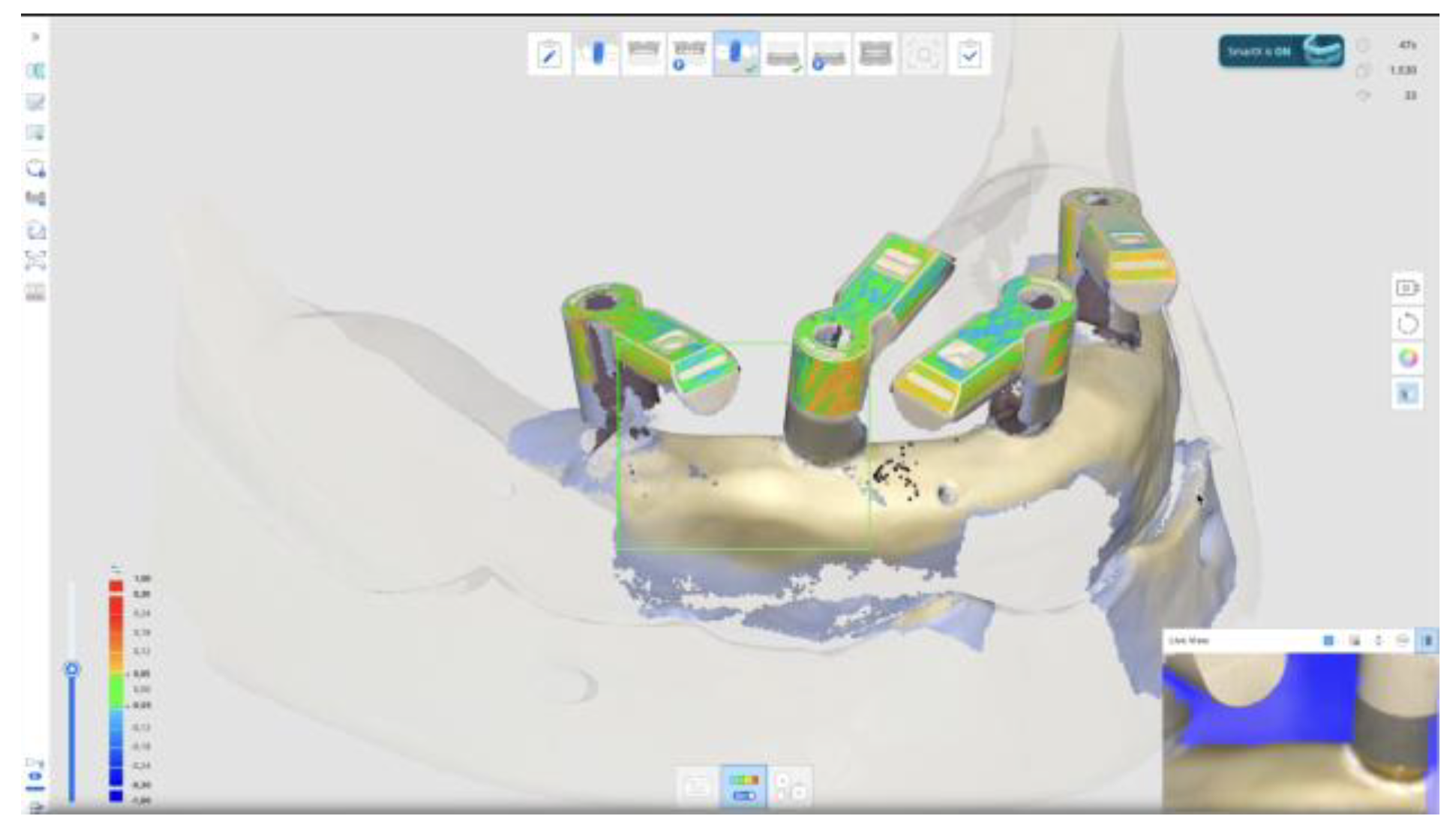

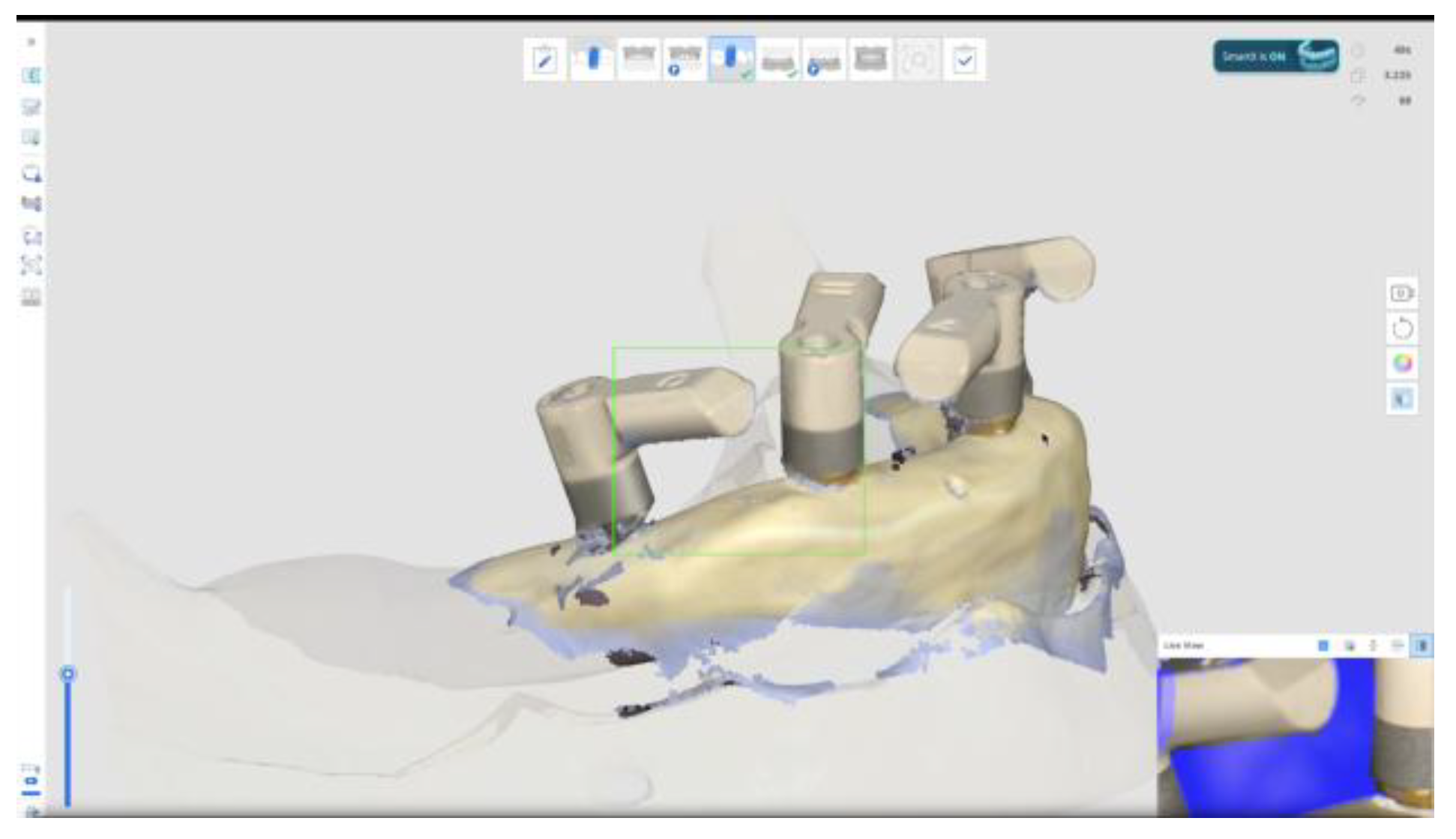

Scan bodies featured with double-wing lateral extensions (SmartFlags, Apollo) / One scan / straight and zigzag motion in anterior, straight motion in posterior / SmartX tool / Expert (n=6), Student (n=6). An example in

Figure 1.

Scan bodies featured with double-wing lateral extensions (SmartFlags, Apollo) / One scan / straight and zigzag motion in anterior, straight motion in posterior / NO SmartX tool / Expert (n=6), Student (n=6). An example in

Figure 2.

Scan bodies featured with single-wing lateral extension (SmartFlags, Apollo) / One scan / straight and zigzag motion in anterior, straight motion in posterior / SmartX tool / Expert (n=6), Student (n=6).

Scan bodies featured with single-wing lateral extension (SmartFlags, Apollo) / One scan / straight and zigzag motion in anterior, straight motion in posterior / NO SmartX tool / Expert (n=6), Student (n=6).

Subgroups at the test group are summarized in

Table 1.

2.1. Outcome Measures

The outcome measures were the accuracy and precision of the impressions, along with the operative time required to record impressions.

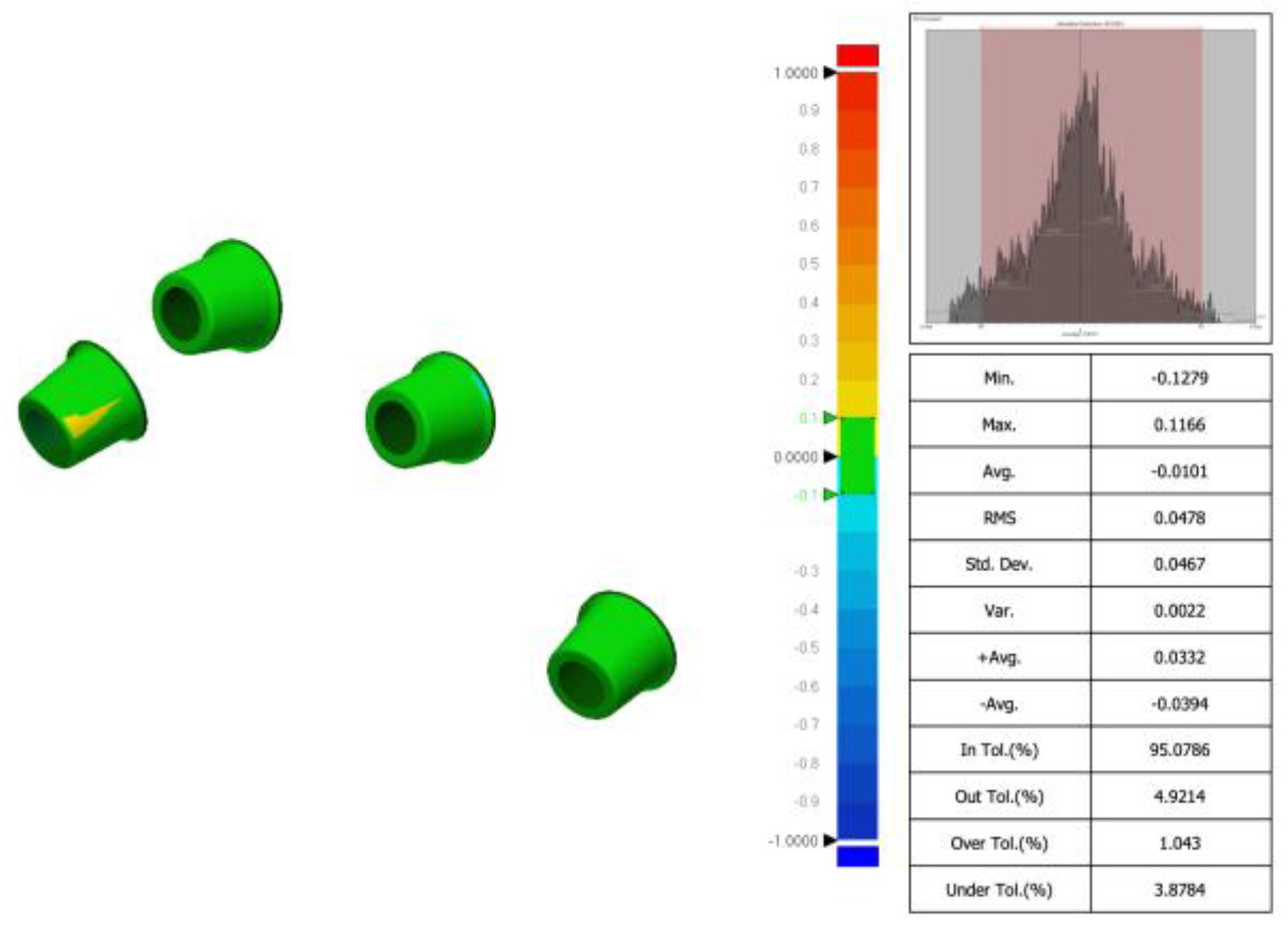

Accuracy was defined as the degree of conformity between the captured data and the actual anatomical dimensions, while precision referred to the consistency of repeated measurements. Accuracy depended on appropriate device calibration and software optimization. Comparisons between the tested groups were performed with superimposition of the files. The STL files obtained from both intraoral scanner and desktop scanners were imported into a dental CAD software (Exocad 3.1 Rijeka prototype, Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Scan bodies were digitally aligned with their corresponding library components to analyze factors affecting accuracy. The basal surfaces of the abutments, considered non-confidential parts of the implant system, were then exported in STL format for evaluation (

Figure 2A–C). To assess scan accuracy, dimensional deviations were quantified using the Root Mean Square (RMS) value derived from 3D superimpositions. All scan files were subsequently analyzed in Geomagic Control X (version 2022.1.0, 3D Systems, Rock Hill, SC, USA), where they were compared to the reference dataset (control group) to determine any dimensional differences (an example in

Figure 3). Operative time was measured as the total time in seconds required to obtain an impression. Timing began at the start of scanning and ended with either scan completion. All measurements were carried out by an experienced examiner (MQ). Geomagic software does not require direct calibration, scan-to-scan comparisons were validated using a control scan as reference (control group).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Mean RMS value and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for each group of six scans. Difference between the sample averages of all groups were compared by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) calculator with random effect model, assuming equal normality based on the Shapiro-Wilk Test. Non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate whether two dependent groups differ significantly from each other. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significant level of 0.05.

3. Results

Originally, in the test group, 72 scans were planned in six subgroups. However, occlusal scan with straight motion without AI tool (no SmartX) failed to generate complete scanned data around the scan body in both expert and student. Consequently, matching with the reference libraries was not performed. On the contrary, using SmartX tool and double-wing scan bodies (SmartFlags, Apollo, Poland) with one occlusal / straight motion, the mean RMS value was 0.0670 ± 0.0238 when scanned by the expert in digital dentistry, while it was 0.0634 ± 0.0082 when scanned by student. Difference was not statistically significant (p=0.732).

Comparing expert and student using two-way ANOVA calculator with random effect model, since the p-value was 0.832 the first null hypothesis (H0) could not be rejected. In other words, using the SmartX tool, the difference in RMS between expert and student is not big enough to be statistically significant. SmartX can improve accuracy and confidence within beginners.

Since the p-value was 0.165, the second null hypothesis (H

0) could not be rejected. In other words, the scanning technique doesn't seem to influence the final accuracy when the SmartX tool is used. However, comparing the four single-wing scan bodies and occlusal scan (straight motion), with same scan bodies and the one scan (straight and zigzag motion in anterior, straight motion in posterior), the difference was statistically significant in the student (p=.041) but not in the expert (P=0.367). In other word, SmartX and single-wing can be more easier to scan for beginners. All the data are reported in

Table 2.

Comparing the time, except that for the occlusal / straight digital impression, in all the other digital impressions, the time needed to record the impression was lower for the expert comparing with the student. A trend of lower time was found in both student and expert for the double-wing / one / straight and zigzag impression (combined). On the contrary, a trend toward longer scanning time was found in case of single-wing scan bodies. All the data are reported in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

A novel digital workflow—SmartX (Medit Link version 3.4.2., MEDIT Corp., South Korea, Seoul)—was employed in this in vitro study to enhance predictability of complete-arch implant rehabilitations. SmartX utilizes AI-driven, real-time detection and alignment of scan body libraries, improving the predictability, efficiency, and safety of digital impressions. A combination of scanning strategies—zigzag and straight paths anteriorly, and straight paths posteriorly—was used to optimize accuracy [

14].

This research demonstrated the expanding role of digital tools in delivering precise, efficient, and patient-centered complete-arch restorations. A critical determinant of long-term success is achieving a passive fit of the definitive prosthesis, which reduces mechanical stress on implants and peri-implant tissues, thereby minimizing complications such as screw loosening, fractures, and peri-implant disease [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Here, the use of multi-unit abutments, IOS, and a CAD/CAM-fabricated metal framework allowed verification of passive fit through the Sheffield (one-screw) test and tactile assessment [

15].

Accurate 3D implant positioning is equally crucial, as depth, angulation, and spacing impact prosthetic fit, occlusion, and force distribution [

19]. In edentulous maxillary cases, where soft tissue mobility and anatomical variability pose challenges, fully guided surgery offers clear advantages. In this report, implants were placed via a digitally planned, pin-retained 3D-printed surgical guide, which also facilitated a minimally invasive crestal sinus lift [

20]. This approach enabled precise navigation of anatomical constraints, contributing to favorable surgical and prosthetic outcomes [

21].

The integration of IOS (Medit i900, South Korea, Seoul) and CBCT imaging supported a seamless digital workflow from diagnosis to final restoration. This facilitated individualized planning, surgical guide fabrication, and prosthetic design tailored to the patient's anatomy. Compared to conventional workflows, a fully digital approach may reduce human errors while enhancing reproducibility, efficiency, and patient comfort [

22]. SmartX played a central role by enhancing scan body recognition and alignment during complete-arch impressions. Its AI algorithms reduced scan mismatches and data inconsistencies—especially valuable in edentulous cases where reliable landmarks are absent. The platform

’s ability to integrate multiple scan paths improved both data integrity and operator confidence during scanning. In addition, in the present study, SmartX seems to be a promising and useful tools especially for beginners, making learning curve easier and quicker. Advanced surgical tools, such as surgical template without metallic sleeves (ONEGuide and ONECAS, Osstem Global Co., Ltd.), further improved surgical precision and overall success. These innovations reflect the shift toward standardized, digitally guided implant protocols.

Another promising benefits of SmartX workflow is the overall time needed to record the impressions. Occlusal / straight digital impressions were very fast with about 20 seconds to record four implants. However, more precision and a tendency of lower time in both student and expert could be expected for double-wing / one / straight and zigzag impression (combined). Conversely, a tendency for longer scanning times was observed with single-wing scan bodies, likely due to reduced progressive acquisition compared to the double-wing design. Finally, it should not be forgotten that in the test group, 72 scans were originally planned, however, occlusal scan with straight motion without AI tool (no SmartX) failed to generate complete scanned data around the scan body. A possible explanation is that when conducting 3D scans, a scanner utilizes a variety of morphological characteristics from the target object as a reference when stitching the scan images together. When a particular area of the object is not scanned, the software in the scanner attempts to fill the empty space by bridging adjacent surfaces. This process is sufficient if the defect is small and the neighboring areas are morphologically similar. However, for large defects, difficulties may arise in the stitching process because of the lack of reference landmarks and the gradual accumulation of error; thus, large defects are likely to lead to inaccurate surface filling, which often manifests as artificial bulges or hollows. This failure in the stitching process was observed in the present study. Although the occlusal scan with straight motion proved to be the least accurate technique, the SmartX AI tool enabled successful impression recording, serving as a valuable aid—particularly in complex situations—by enhancing clinician confidence and the reliability of IOS.

5. Conclusions

This research demonstrates the promising potential of AI-enhanced digital workflows for complete-arch implant rehabilitation. The integration of SmartX, guided surgery, and CAD/CAM technologies facilitated precise, efficient treatment. Nonetheless, broader validation through multi-center studies and long-term data is essential to validate this protocol and support wider clinical application. In addition, SmartX workflow could improve consistence and confidence, particularly for the beginners. Despite the promising outcomes observed with the SmartX AI tool, this study has several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size and in vitro setting may not fully replicate clinical scenarios, especially in the presence of patient-specific variables such as saliva, movement, or restricted intraoral access. Additionally, while scan accuracy and time efficiency were evaluated, the impact of different lighting conditions, angulations, and soft tissue interference was not assessed. Furthermore, the study did not include other commercially available scan body designs, which could have influenced the results and may yield different outcomes.

Moreover, the subjective assessment of operator confidence, although valuable, may benefit from standardized, quantitative metrics in future research. The failure of the occlusal scan with straight motion (without AI assistance) also highlights the need to explore the limitations of scanner software algorithms and their dependency on morphological references for image stitching.

Future studies should aim to validate these findings in a clinical setting with a larger and more diverse population, including edentulous and partially edentulous patients. Expanding the scope to include various intraoral scanner brands and additional scan body geometries could also enhance the generalizability of the results. Further investigation into machine learning models that adapt in real-time to operator behavior and scanning environments could open new avenues for increasing the robustness and intelligence of digital impression systems.

References

- Dioguardi M, Spirito F, Quarta C, Sovereto D, Basile E, Ballini A, Caloro GA, Troiano G, Lo Muzio L, Mastrangelo F. Guided Dental Implant Surgery: Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2023 Feb 13;12(4):1490. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mai HN, Dam VV, Lee DH. Accuracy of Augmented Reality-Assisted Navigation in Dental Implant Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2023 Jan 4;25:e42040. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahardawi B, Jiaranuchart S, Arunjaroensuk S, Dhanesuan K, Mattheos N, Pimkhaokham A. The Accuracy of Dental Implant Placement With Different Methods of Computer-Assisted Implant Surgery: A Network Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2025 Jan;36(1):1-16. Epub 2024 Sep 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain S, Sayed ME, Khawaji RAA, Hakami GAJ, Solan EHM, Daish MA, Jokhadar HF, AlResayes SS, Altoman MS, Alshehri AH, Alqahtani SM, Alamri M, Alshahrani AA, Al-Najjar HZ, Mattoo K. Accuracy of 3 Intraoral Scanners in Recording Impressions for Full Arch Dental Implant-Supported Prosthesis: An In Vitro Study. Med Sci Monit. 2024 Dec 8;30:e946624. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kihara H, Hatakeyama W, Komine F, Takafuji K, Takahashi T, Yokota J, Oriso K, Kondo H. Accuracy and practicality of intraoral scanner in dentistry: A literature review. J Prosthodont Res. 2020 Apr;64(2):109-113. Epub 2019 Aug 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDI World Dental Federation. Artificial intelligence in dentistry. Int Dent J. 2025 Feb;75(1):3-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ossowska A, Kusiak A, Świetlik D. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry-Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Mar 15;19(6):3449. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pae, H. C. , Kim, S. K., Park, J. Y., Song, Y. W., Cha, J. K., Paik, J. W., & Choi, S. H. (2019). Bioactive characteristics of an implant surface coated with a pH buffering agent: an in vitro study. Journal of periodontal & implant science, 49(6), 366–381. [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Corchado, E. , & Pardal-Peláez, B. (2022). Computer-Guided Surgery for Dental Implant Placement: A Systematic Review. Prosthesis, 4, 540–553. [CrossRef]

- Tahmaseb A, Wismeijer D, Coucke W, Derksen W. Computer technology applications in surgical implant dentistry: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014;29 Suppl:25-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, H. Y. , Mai, H. N., Lee, C. H., Lee, K. B., Kim, S. Y., Lee, J. M., Lee, K. W., & Lee, D. H. (2022). Impact of scanning strategy on the accuracy of complete-arch intraoral scans: a preliminary study on segmental scans and merge methods. The journal of advanced prosthodontics, 14(2), 88–95. [CrossRef]

- Tallarico, M.; Qaddomi, M.; De Rosa, E.; Cacciò, C.; Jung, Y.J.; Meloni, S.M.; Ceruso, F.M.; Lumbau, A.I.; Pisano, M. Accuracy and Precision of Digital Impression with Reverse Scan Body Prototypes and All-on-4 Protocol: An In Vitro Research. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maló, P.; Rangert, B.; Nobre, M. “All-on-Four” immediate-function concept with Brånemark System implants for completelyedentulous mandibles: A retrospective clinical study. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2003, 5 (Suppl. S1), 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallarico, M. , Czajkowska, M., Cicciù, M., Giardina, F., Minciarelli, A., Zadrożny, Ł., Park, C. J., & Meloni, S. M. (2021). Accuracy of surgical templates with and without metallic sleeves in case of partial arch restorations: A systematic review. Journal of dentistry, 115, 103852. [CrossRef]

- Tallarico, M. , Caneva, M., Meloni, S. M., Xhanari, E., Covani, U., & Canullo, L. (2018). Definitive Abutments Placed at Implant Insertion and Never Removed: Is It an Effective Approach? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery: official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 76(2), 316–324. [CrossRef]

- Mai, H. Y. , Mai, H. N., Lee, C. H., Lee, K. B., Kim, S. Y., Lee, J. M., Lee, K. W., & Lee, D. H. (2022). Impact of scanning strategy on the accuracy of complete-arch intraoral scans: a preliminary study on segmental scans and merge methods. The journal of advanced prosthodontics, 14(2), 88–95. [CrossRef]

- Buzayan, M. M. , & Yunus, N. B. (2014). Passive Fit in Screw Retained Multi-unit Implant Prosthesis Understanding and Achieving: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society, 14(1), 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Figueras-Alvarez, O. , Cantó-Navés, O., Real-Voltas, F., & Roig, M. (2021). Protocol for the clinical assessment of passive fit for multiple implant-supported prostheses: A dental technique. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, 126(6), 727–730. [CrossRef]

- Tallarico, M. , & Meloni, S. M. (2017). Retrospective Analysis on Survival Rate, Template-Related Complications, and Prevalence of Peri-implantitis of 694 Anodized Implants Placed Using Computer-Guided Surgery: Results Between 1 and 10 Years of Follow-Up. The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants, 32(5), 1162–1171. [CrossRef]

- Meloni, S. M. , Tallarico, M., Pisano, M., Xhanari, E., & Canullo, L. (2017). Immediate Loading of Fixed Complete Denture Prosthesis Supported by 4-8 Implants Placed Using Guided Surgery: A 5-Year Prospective Study on 66 Patients with 356 Implants. Clinical implant dentistry and related research, 19(1), 195–206. [CrossRef]

- Tallarico, M. , Meloni, S. M., Canullo, L., Caneva, M., & Polizzi, G. (2016). Five-Year Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Patients Rehabilitated with Immediately Loaded Maxillary Cross-Arch Fixed Dental Prosthesis Supported by Four or Six Implants Placed Using Guided Surgery. Clinical implant dentistry and related research, 18(5), 965–972. [CrossRef]

- Tallarico, M.; Galiffi, D.; Scrascia, R.; Gualandri, M.; Zadrożny, Ł.; Czajkowska, M.; Catapano, S.; Grande, F.; Baldoni, E.; Lumbau, A.I.; et al. Digital Workflow for Prosthetically Driven Implants Placement and Digital Cross Mounting: A Retrospective Case Series. Prosthesis 2022, 4, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).