1. Introduction

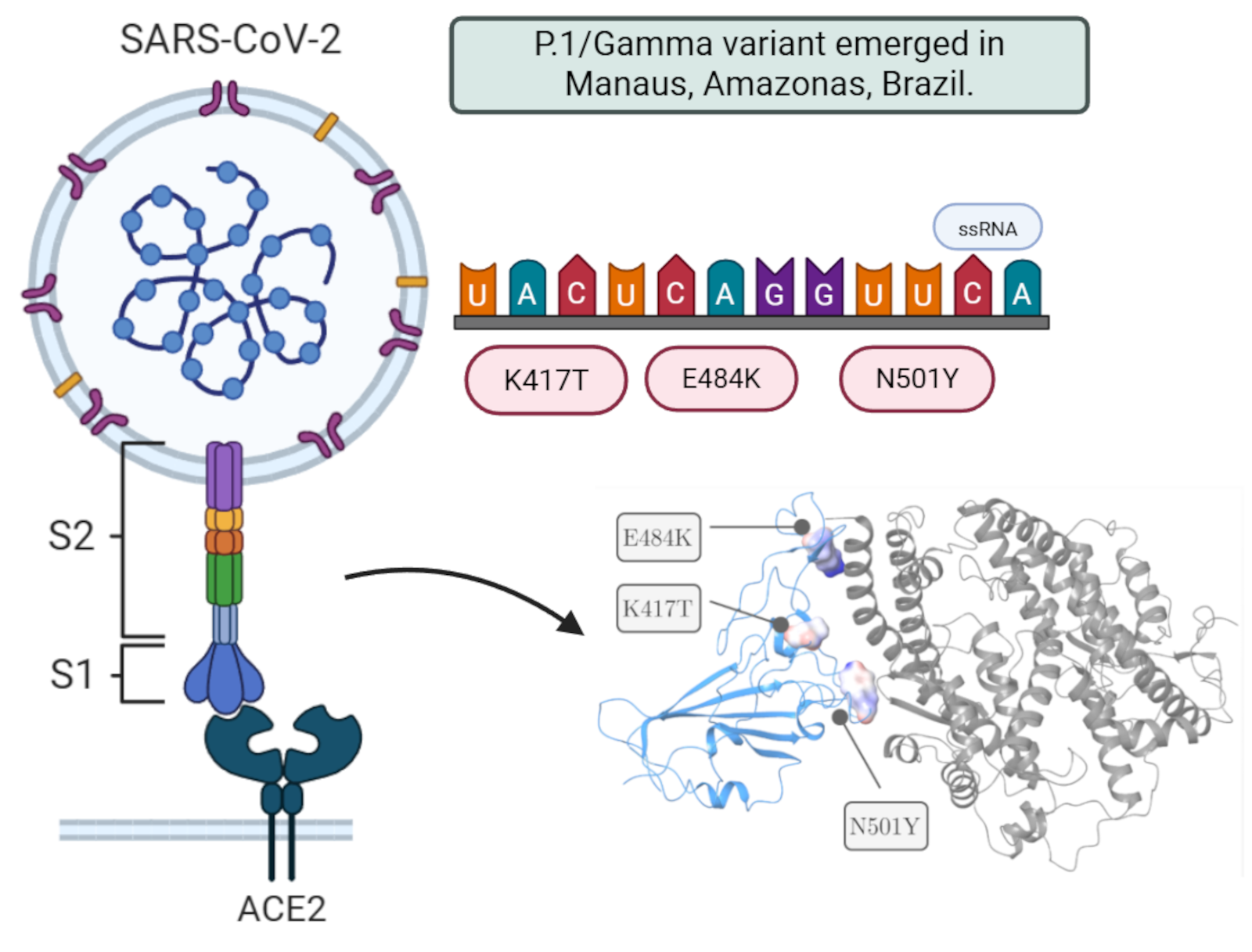

Among the variants, there was the P.1 or Gamma variant (B.1.1.28), which was mainly responsible for the serious 2nd wave of cases between the months of January and February 2021 in the city of Manaus, Amazonas. As consequence, the entire public health system was overloaded, and which unfortunately resulted in the loss of several lives [

1,

2,

3]. The P.1 variant is constituted by the set of 12 (twelve) mutations although only 3 (three) mutations are critical and affect the RBD region of the Spike glycoprotein: K417T, E484K and N501Y [

1]. From a collaboration formed between Brazilian and international researchers, it was found that the P.1 variant spread at a rate 1.4-2.2 times faster than the initial Wuhan strain and also increased the propensity for reinfection by 25-61%. A 1.1-1.8 fold increase in the mortality rate was also reported [

2,

4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been naming emerging variants of the novel coronavirus using letters of the Greek alphabet. The first to be identified was the Alpha variant in 2020. Since then, the virus has continued to evolve, leading to the most recent Omicron subvariants [

5]. Among the SARS-CoV-2 variants, some are classified as Variants of Concern (VOC), while others are merely Variants of Interest (VOI). Fortunately, to date, no Variant of High Concern (VOHC) — which would significantly increase virulence and pathogenicity — has ever emerged.

Most mutations in the virus are neutral and therefore do not generate noticeable phenotypic changes. However, mutations that arise due to positive selection pressure can increase viral fitness. These mutations are mainly responsible for the emergence of new variants [

6]. Among the variants of SARS-CoV-2, some are called Variants of Concern (VOC) while others are just Variants of Interest (VOI).

It was discovered through the genetic sequencing of four travelers from the state of Amazonas on their trip to Japan that a new lineage, B.1.1.28/P.1, had emerged. This clade consists of a set of 12 mutations, although only three are critical and affect the RBD region of the Spike glycoprotein: K417T, E484K, and N501Y [

1]. The P.1 variant is also referred to as the Gamma variant, following the recommendation of the WHO. The P.2 lineage originally emerged in Rio de Janeiro and has already been detected in several regions of Brazil, including Manaus, where it was found that two patients had been reinfected with SARS-CoV-2 [

7]. Additionally, there is

in vitro evidence that the presence of the E484K mutation reduces the efficacy of polyclonal antibodies derived from convalescent serum [

8].

From a molecular point of view, the virus has been increasing its affinity in interacting with the ACE2 receptor [

9]. However, the environment may increase the likelihood of variants emerging, mainly as a result of low adherence to social distancing especially during the peaks of the pandemic. Despite all this, it was found that although vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies may have their ability to recognize the antigen reduced, CD4

+ and CD8

+ T cells normally recognize the protein sequence Spike same with all your changes [

10].

Due to the fact that there is still little research in structural bioinformatics in the understanding of SARS-CoV-2, we sought in this work to elucidate at the molecular level the variant of concern P.1 in relation to the responses induced by ACE2 recognition by the Spike protein . In this way, we used bioinformatics techniques such as molecular dynamics (MD) and the estimation of the value of the free energy of interaction (ΔG) in the molecular recognition of P.1 variant and also resulting from neutralizing antibodies. Finally, we used the Monte Carlo method to find mutations that would increase the antibody-antigen interaction of SARS-CoV-2, but also to predict possible emerging mutations in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

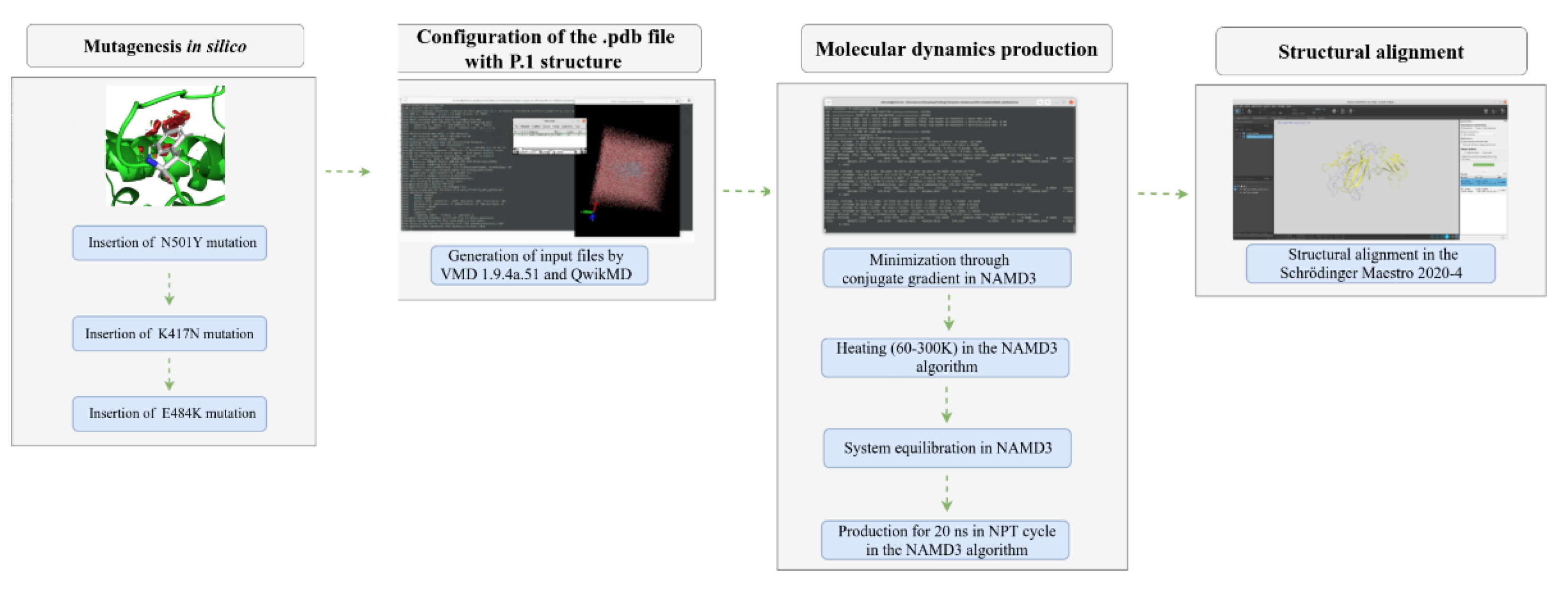

2.1. Mutagenesis and Comparative Between Variants of Concern

The insertion of P.1 variant mutations affecting the RBD region of the Spike protein was performed using the “Residue and Loop Mutation” module in the Schrodinger Maestro 2021-2 software. All crystallographic structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [

11]. Due to computational limitations, simulating the entire Spike protein was infeasible, as the data could not be fully allocated in GPU memory. Consequently, we focused exclusively on the RBD region. A total of 11 mutations defining the P.1 variant (L18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, K417T, E484K, N501Y, D614G, H655Y, T1027I, and V1176F) were inserted into the ACE2-Spike complex (PDB ID: 7DF4), as these mutations were reported to be present in over 75% of sequenced samples.

After introducing mutations, it was necessary to resolve steric clashes between atoms. Through molecular dynamics, structure minimization and equilibration were conducted, allowing for a comparative analysis of the thermodynamic impact of the mutations. These simulations were essential for studying the stability of different virus lineages in the ACE2-RBD and antibody-antigen interactions.

2.2. Prediction of Change in Stability/Affinity upon P.1 Mutations

Initially, it was obtained the positions and modifications of all mutations that constitute the P.1 and variant from the Outbreak.info platform (

https://outbreak.info/situation-reports). In parallel, we used the I-Mutant 3.0 tool (

https://folding.biofold.org/i-mutant/i-mutant2.0.html) [

12], which implements a machine-learning SVM approach to predict ΔΔG as a result of emerging variants. For this, we adopted structures with a higher number of amino acids since this reduces computational complexity. Accordingly, it was used the ACE2-Spike complex (PDB ID: 7DF4) [

13] and the neutralizing antibody RBD-Ty1 (PDB ID: 6ZXN) [

14], under physiological conditions at pH = 7.4, a temperature of 25°C, and the SVM3 ternary classification algorithm. This classification distinguishes stability (ΔΔG ≥ + 0.5 kcal ⋅ mol

-1), destabilization (ΔΔG ≤ -0.5 kcal ⋅ mol

-1), and neutrality (-0.5 kcal ⋅ mol

-1 ≤ ΔΔG ≤ +0.5 kcal ⋅ mol

-1). Although not all authors denote a positive sign as stabilization, in this study, we adopted the convention that (+) indicates stabilization and (-) indicates destabilization, as shown in the equation below:

Finally, it was also studied the stability as a function of the mutations constituting the P.1 variant using the Prime algorithm integrated into the Schrödinger Maestro 2021-2 software [

15]. Using the “Residue Scanning” module [

16], the mutations from the P.1 variant were computationally introduced, and the backbone was subsequently minimized using the Prime algorithm with a cutoff of 5.0Å relative to residues near the mutation area. Other tools were also used for stability calculation, including EnCOM for conformational entropy analysis, as well as tools for stability variation analysis in the face of mutations, including mCSM [

17], DynaMut2 [

18], DUET [

19].

2.3. Performing Molecular Dynamics Simulations of ACE2-RBD Interaction

It was performed Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to analyze the stability and binding affinity of different classes of antibodies and to compare the P.1 variant and wild-type from Wuhan strain with each other.

In this stage, all-atom molecular dynamics simulations were performed for 50 ns on the ACE2-RBD complex (PDB ID: 6M0J) [

20] in the presence of the B.1.1.28/P.1 (E484K, K417T, N501Y) and B.1.1.28/P.2 (E484K, K417N, N501Y) lineages that emerged in Brazil. We also studied the impact on the interaction with the neutralizing antibody P2B-2F6, specific to the RBD (PDB ID: 7BWJ) [

21]. This antibody was derived from B lymphocytes of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. All proteins were previously prepared using the academic version of the Schrödinger Maestro 2021-2 software [

22] through the “Protein Preparation” module. This step included adjustments to ionization states, cofactors, assignment of partial charges, and the addition of hydrogen atoms to the structure.

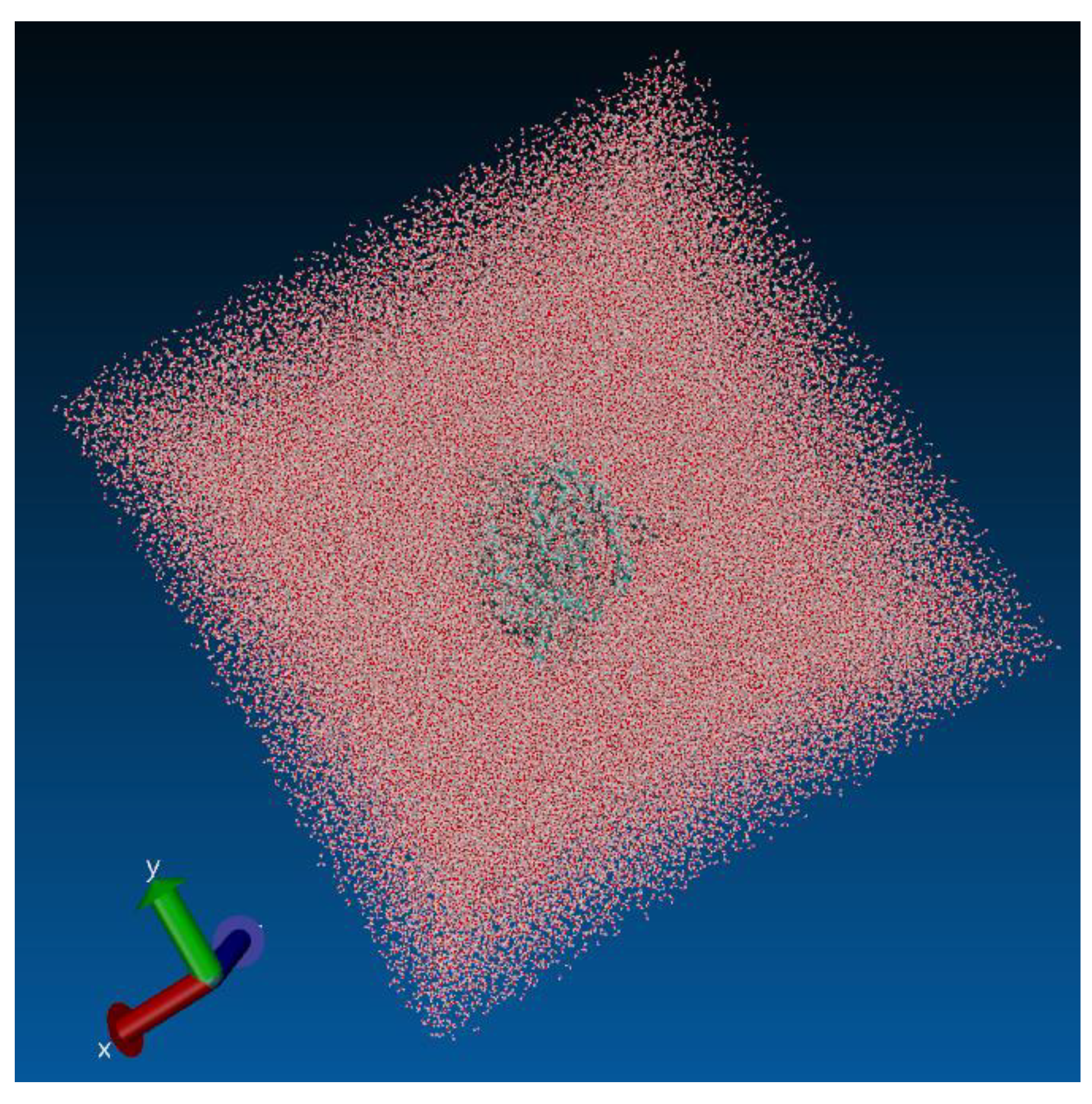

All input and configuration files were generated using the QwikMD 1.3 plugin [

23], implemented in the VMD 1.9.4.48a graphical interface [

24]. The complex was immersed in a solvation box (see

Figure 1) with cubic geometry and periodic boundary conditions (PBC), containing water molecules described by the TIP3P model [

25] at a standard distance of 12.0 Å from the box boundaries. Counterions of Na⁺ and Cl⁻ were added to neutralize the system at a physiological molar concentration of 0.15 mol·L⁻¹. In the ACE2-RBD complex, there were a total of 422,271 atoms and 136,320 water molecules, as automatically determined by the QwikMD algorithm. It is important to note that these values may vary slightly between the structure containing mutations and the one without. In the antibody-antigen complex, there were 465,723 atoms and 151,791 water molecules. All topology files were generated using the CHARMM36 force field [

26]. The system was minimized using the conjugate gradient approach over 1,000 steps. Subsequently, gradual heating from 60 K to 300 K was performed at a rate of 1 K·ps⁻¹ under the NPT ensemble over 0.24 ns. Following this, the system was equilibrated under the NPT ensemble for 1 ns. Additionally, isotropic fluctuations were assigned to the simulation box, with the variable

FlexibleCell=no defined for this purpose.

Finally, the production of trajectories used the r-RESPA integration method [

27] in an NPT thermodynamic cycle for approximately 50 ns for the ACE2-RBD complex, with data recorded every 0.02 ns. A stochastic piston via Langevin dynamics was used for pressure control, analogous to a barostat under standard conditions of 1 atm, a period of 200 fs, and a decay time of 100 fs. A Nosé-Hoover thermostat [

28] was adopted with a coupling coefficient of τₚ = 1 ps⁻¹. Long-range electrostatic interactions were estimated using the Particle-Mesh-Ewald (PME) formalism [

29] with a cutoff of 12.0 Å, while the SHAKE algorithm [

30] was used to constrain all hydrogen bonds formed during the simulation. The simulations were performed using the NAMD3 (Nanoscale Molecular Dynamics) algorithm [

31], developed by researchers at the University of Illinois and made freely available. As a result, all simulations were executed with GPU acceleration using an Nvidia GTX 1050 2 GB model with 640 CUDA cores at a 2 fs time step. Due to computational limitations, the mutation studies were restricted to the RBD region (229 amino acids) rather than the entire Spike receptor (1,273 amino acids).

3. Results

3.1. Machine-Learning Stability Prediction upon Mutations

Initially, we qualitatively organize the mutations that constitute each of the variants of concern (see Supplementary Table 1). This step was important for us to understand which mutations of the P.1 variant remained throughout the viral evolution. Among the 12 (twelve) mutations that were present in the Spike (S) protein of the P.1 variant, 8 (eight) were exclusive to P.1, namely: T18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, K417T, D1027I and V1176F. On the other hand, only 3 (three) mutations are shared between P.1 and Omicron variants, these being N501Y, D614G and H655Y. We noticed that while in P.1 the mutations K417T and E484K were present, in the following variants, such as Delta and Omicron, it was changed to K417N and E484A. Through an analysis using the I-Mutant 3.0 tool [

12], we predicted the global ΔΔG value for the ACE2-Spike structure (PDB ID: 7DF4) as a consequence of the three mutations that constitute the P.1 lineage.

The global ΔΔG value was -1.85 kcal/mol, with the following contributions: N501Y (-0.08 kcal/mol and ΔΔS ≈ +0.138 kcal/mol·K); K417T (-1.50 kcal/mol and ΔΔS ≈ +0.507 kcal/mol·K); E484K (-0.27 kcal/mol and ΔΔS ≈ +0.171 kcal/mol·K). Therefore, we can infer that the N501Y mutation, which emerged in the United Kingdom, would not significantly affect the ACE2-Spike interaction since the destabilization does not reach the critical threshold. The same conclusion applies to the E484K mutation, which appeared in South Africa and did not reach the threshold of -0.50 kcal/mol, although molecular dynamics are necessary for a better understanding of the impacts.

It is worth noting that mutations causing destabilization tend to disappear due to evolutionary pressure, as they negatively impact protein function [

32]. According to the literature, stability is proportional to lower conformational entropy, but it cannot be inferred that greater stability is necessarily related to greater disease severity. Further stability studies through molecular dynamics are necessary, with results presented in the following section.

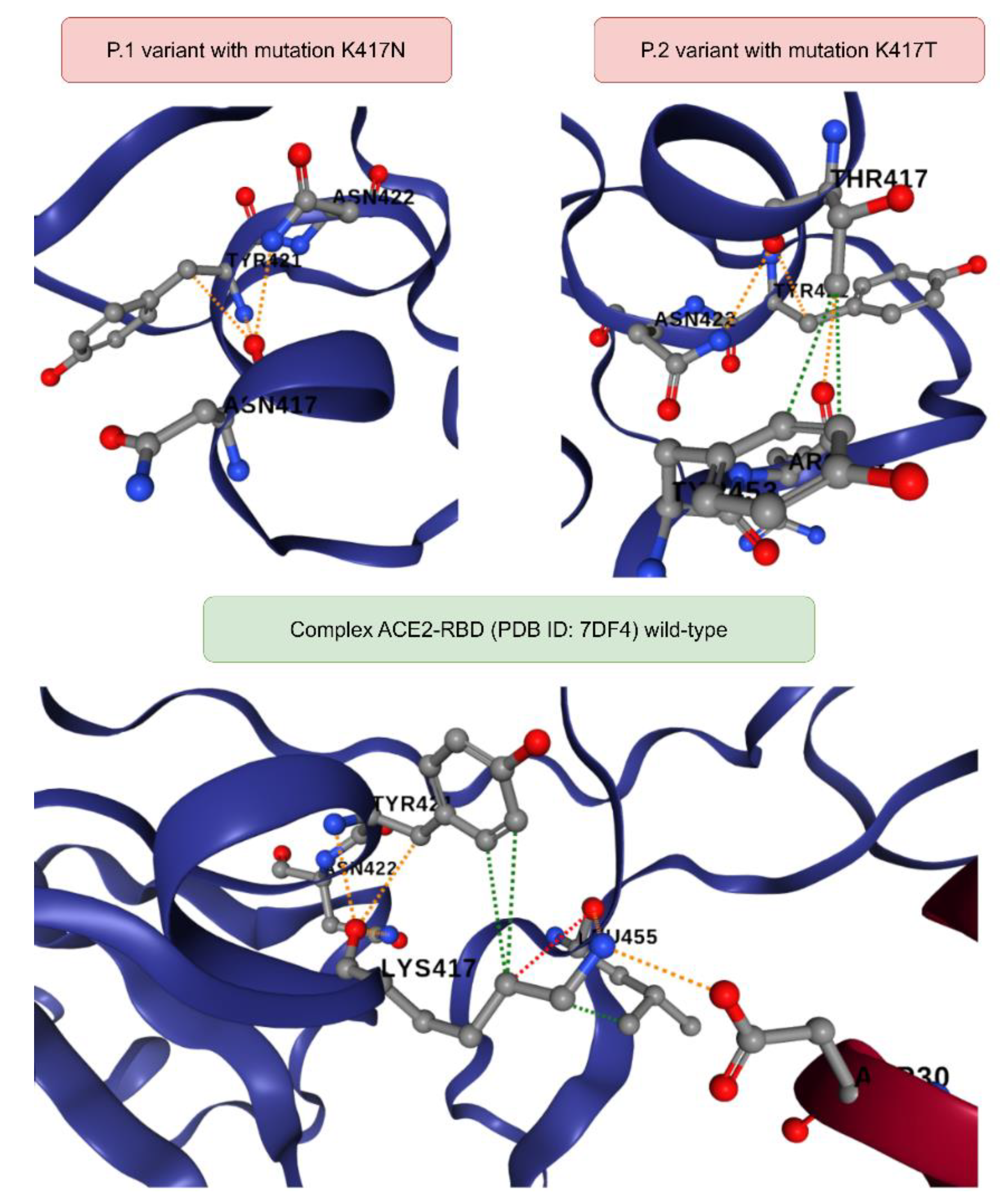

To gain greater confidence in the stability results for the ACE2-Spike complex, we predicted the ΔΔG value using the mCSM tool [

17], obtaining the following results: N501Y (-0.757 kcal/mol); K417T (-1.594 kcal/mol); E484K (-0.081 kcal/mol). Once again, the K417T mutation from the P.1 lineage showed critical destabilization, as observed with the I-Mutant 3.0 tool. When analyzing the P.2 lineage, the K417N mutation generated lower destabilization at -1.582 kcal/mol, providing preliminary evidence that modifications to the Lys417 residue in the Spike protein might be primarily responsible for the increased viral transmissibility in Amazonas. As shown in Figure X, the K417N mutation proved critical, second only to R190S, which did not affect the RBD region of the protein and therefore is not directly involved in ACE2 receptor interaction.

Using the DynaMut2 tool [

18], we assessed the impact of mutations on chemical bonds (see Figure Y). The same pattern was observed in the P.1 lineage with the K417T mutation, although it demonstrated greater stability due to the loss of only one hydrogen bond, one hydrophobic contact, and one polar interaction. Therefore, mutations closer to the ACE2-Spike interaction interface tend to be more concerning due to the higher likelihood of intermolecular interactions.

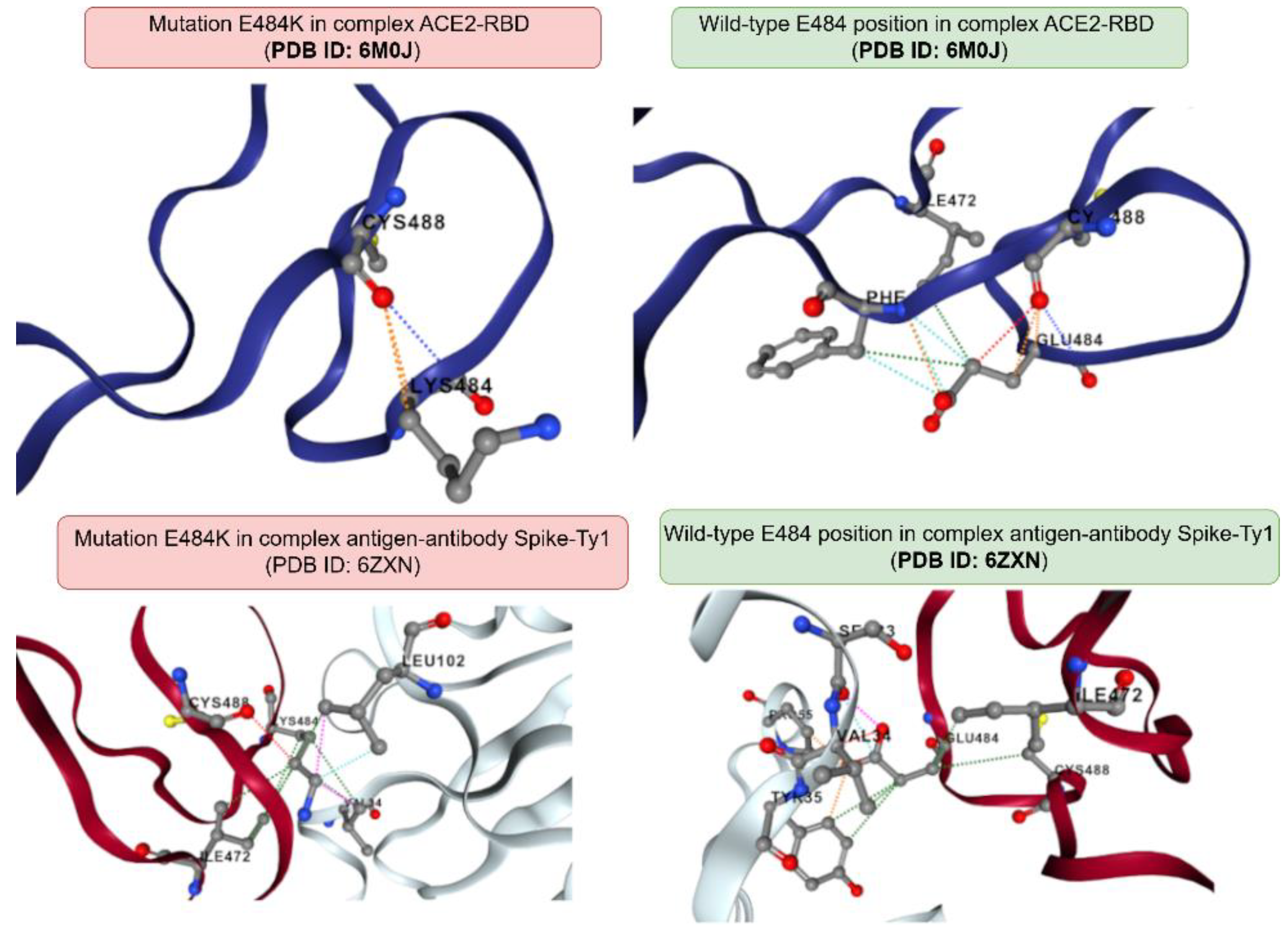

When analyzing the Spike-Ty1 interaction (PDB ID: 6ZXN) with mutations present in the P.1 lineage, destabilization was observed, reflecting a weaker interaction between the Spike glycoprotein and neutralizing antibodies: N501Y (-0.35 kcal/mol); K417T (-0.82 kcal/mol); E484K (-0.50 kcal/mol). Among all the results, the most concerning is again the K417T mutation, which presents critical destabilization and may potentially hinder immune response through vaccination. In the P.2 lineage, the K417N mutation demonstrated lower stability compared to K417T, with a result of -0.90 kcal/mol. Consequently, there appears to be a greater difficulty in molecular antibody recognition due to the P.2 lineage compared to P.1. Additionally, the E484K mutation (see

Figure 2) is precisely located at the antibody-antigen interface, which could correlate with recognition difficulties due to destabilization. This can be explained by the mutation causing the formation of three hydrophobic contacts, one Van der Waals interaction, and the loss of six polar interactions and two carbonyl interactions.

Figure 2.

Preparation steps of mutagenesis of P.1 variant and molecular dynamics simulations in Desmond, where we can visualize the solvation box created in the Schrodinger Maestro 2021-2 software. In this image were inserted the RBD region of Spike protein with mutations of P.1 variant.

Figure 2.

Preparation steps of mutagenesis of P.1 variant and molecular dynamics simulations in Desmond, where we can visualize the solvation box created in the Schrodinger Maestro 2021-2 software. In this image were inserted the RBD region of Spike protein with mutations of P.1 variant.

Figure 3.

Comparison between the chemical interactions formed in the ACE2-Spike complex (PDB ID: 7DF4) as a consequence of the K417T and K417N mutations referring to the P.1 and P.2 strains, respectively. All diagrams were generated in the DynaMut2 platform. The dashed lines in green represent the hydrophobic contacts, the lines in red correspond to the hydrogen bonds and finally the color orange refers to the polar interactions.

Figure 3.

Comparison between the chemical interactions formed in the ACE2-Spike complex (PDB ID: 7DF4) as a consequence of the K417T and K417N mutations referring to the P.1 and P.2 strains, respectively. All diagrams were generated in the DynaMut2 platform. The dashed lines in green represent the hydrophobic contacts, the lines in red correspond to the hydrogen bonds and finally the color orange refers to the polar interactions.

Figure 4.

Chemical interactions formed in the ACE2-RBD and antibody-antigen complexes in response to the E484K mutation present in the P.1 variant. Visualization was performed using the DynaMut2 platform.

Figure 4.

Chemical interactions formed in the ACE2-RBD and antibody-antigen complexes in response to the E484K mutation present in the P.1 variant. Visualization was performed using the DynaMut2 platform.

Upon examining all mutations in P.1 and P.2, we observed that the N501Y mutation was the only one that directly affected the antibody-antigen interface. However, the ΔΔG value was not significant enough to indicate that the damages to patients could be more severe than currently observed.

3.2. Profile of New Emergent Mutations

Using the MAESTROweb tool [

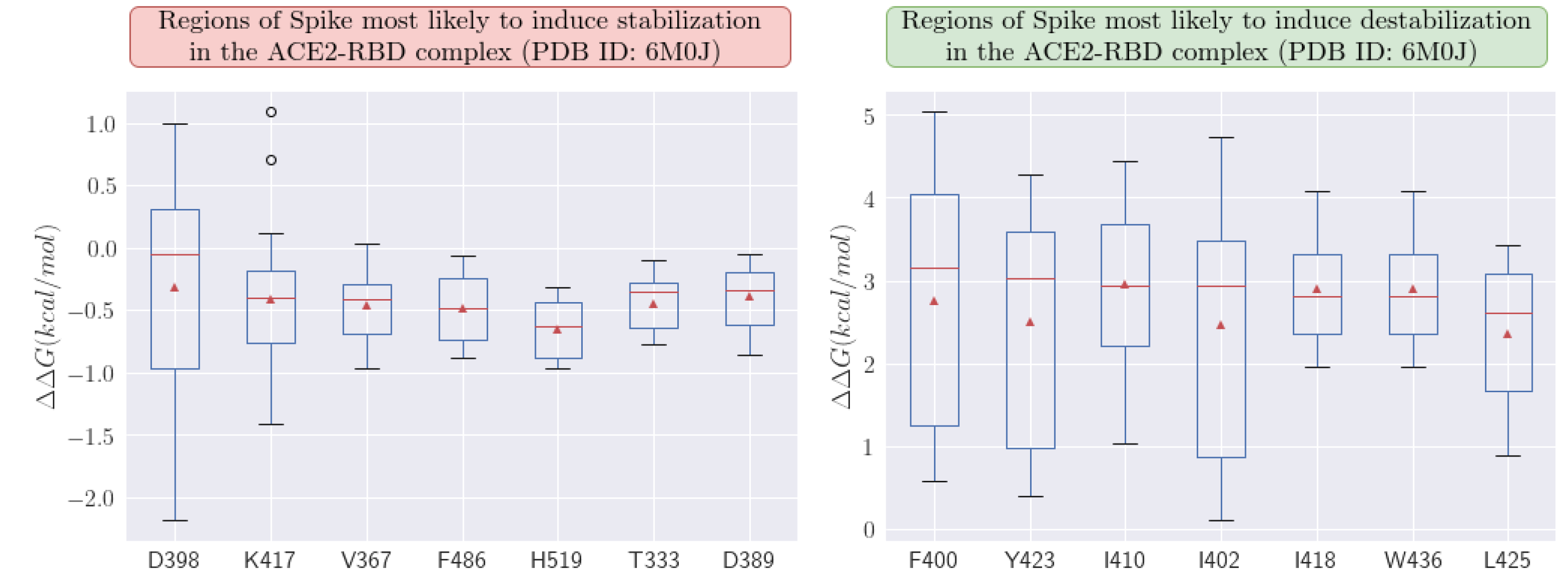

33], we were able to predict which regions of the RBD protein in Spike are most susceptible to mutations (see profile mutations). This analysis may potentially aid in the next generation of vaccines, allowing these considerations to be integrated into their development process. When examining the mutation profile, we observed that position H519 shows one of the most favorable stabilization averages at -0.653 kcal/mol. Position K417 is also highly susceptible and is associated with several variants, showing an average stabilization of -0.410 kcal/mol.

It is important to emphasize that greater stabilization benefits the virus by increasing interaction with ACE2, whereas destabilization has the opposite effect. Upon analyzing destabilizing regions, position I410 was found to be the most detrimental to the virus, with an average value of +2.948 kcal/mol.

Figure 5.

Profiles of amino acid regions in the Spike protein most sensitive to stabilizing and destabilizing mutations. We analyzed the ACE2-RBD complex (PDB ID: 6M0J). All calculations were performed with the MAESTROweb platform.

Figure 5.

Profiles of amino acid regions in the Spike protein most sensitive to stabilizing and destabilizing mutations. We analyzed the ACE2-RBD complex (PDB ID: 6M0J). All calculations were performed with the MAESTROweb platform.

With the help of the PDBePISA platform [

34], variant P. 1 presented Δ

iG ≈ -6.5 kcal/mol, and therefore more favorable compared to the structure without any mutations where Δ

iG ≈ -5.9 kcal/mol. This would perhaps explain,

a priori, why the P.1 lineage would be characterized by an increase in transmissibility [

2]. In order to complement the results, we performed protein-protein docking from the last frame (see

Table 3) using the HDock platform (

http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/) [

35] with all default settings. In the HDock tool, depending on the receptor and ligand order, we can obtain different results. Thus, for more favorable and consistent results, we considered the RBD protein as the receptor while the ligand was the ACE2 protein. In this, the ACE2-RBD complex (PDB ID: 6M0J) [

20] containing the P. 2 lineage expressed higher affinity with a relative score of -311.75 while in the absence of mutations it was -310.19. The P.1 variant stands out, presenting an even more expressive interaction with -331.14. These results corroborate the hypothesis that P. 1 actually makes the interaction of Spike with the cellular receptor ACE2 more expressive. The PatchDock tool [

36] was also used, which employs principles of geometric complementarity where we adopted the “Default” configuration and the type of protein-protein complex in all simulations and clustering for the RMSD of 4Å. Thus, the P.1 variant also reflected an increase in affinity in the ACE2-RBD complex where the score increased from 15722 to 16940 compared to the reference structure.

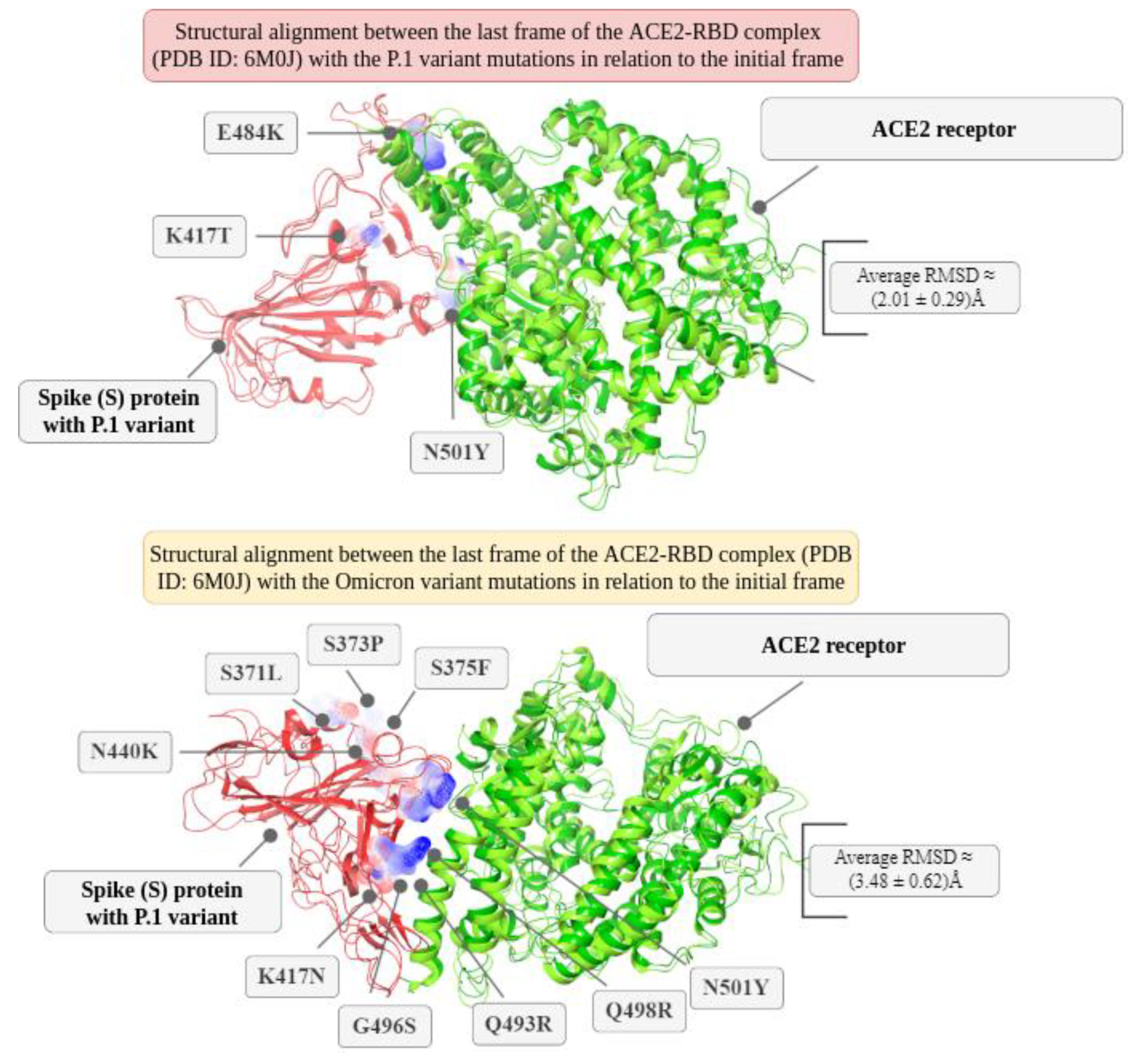

3.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of P.1 Variant

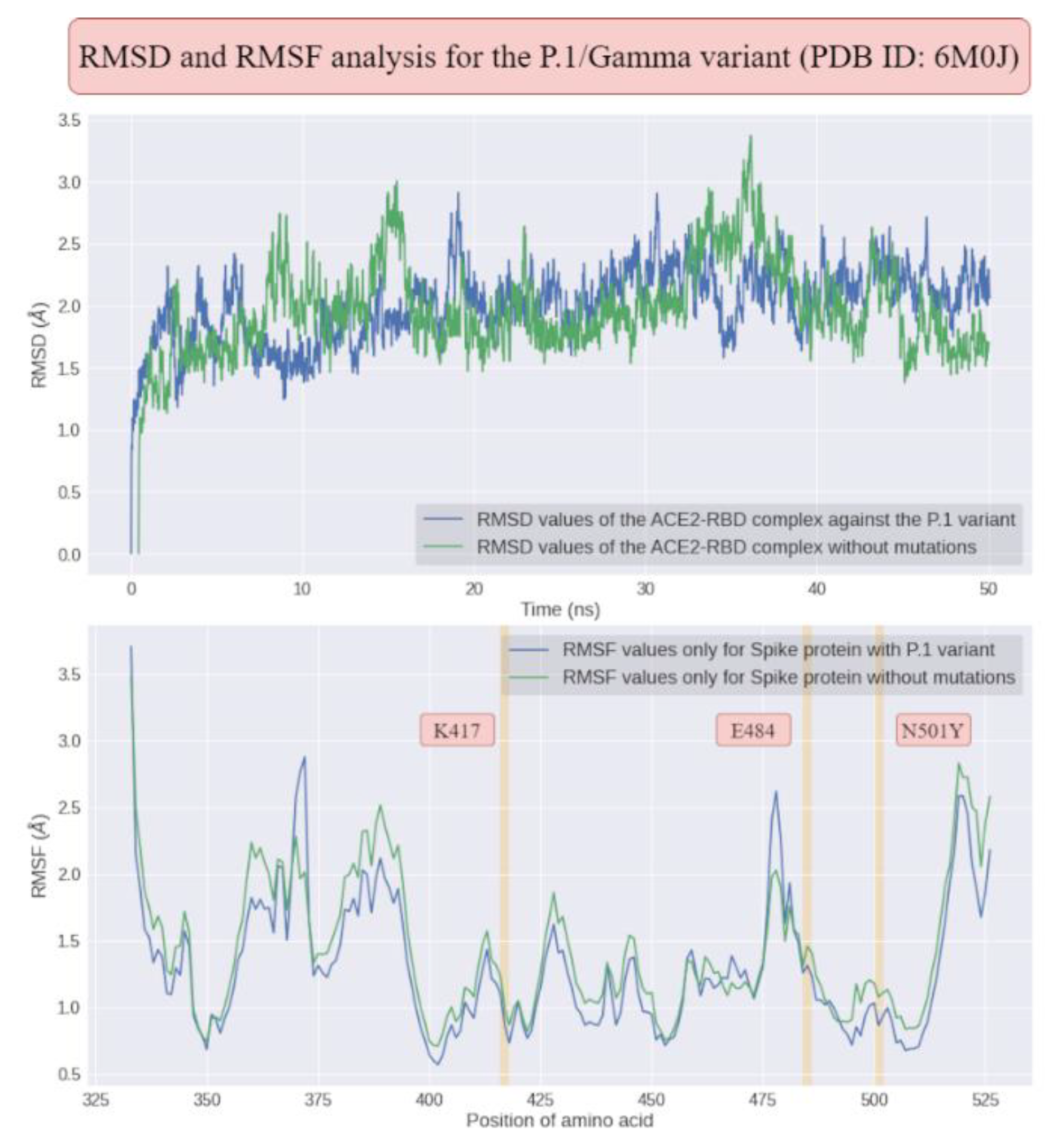

Firstly, it was performed a molecular dynamics analysis for the P.1 variants (see

Figure 6). After, it was superimposed the last frame obtained from the molecular dynamics of the P.1 lineage and the respective initial structure in relation to Cα in order to understand the impacts of temporal evolution. Thus, using the Schrödinger Maestro 2021-2 software, the alignment resulted in an atomic displacement with an RMSD of 2.1203 Å, which reflects relative structural changes at the global level due to the mutations. This result was also corroborated by the PDBeFold platform with an RMSD of 1.320 Å and by TM-Align with an RMSD of 2.05 Å. We also analyzed the overlap of the last frame for the simulation without mutations in relation to the initial frame, where there was an RMSD of 1.8135 Å. When using TM-Align, the result was 1.81 Å, and using PDBeFold, it was 1.256 Å. These results indicate that P.1 presented more expressive conformational fluctuations in the ACE2-RBD interaction compared to the structure without any mutations, although P.1 is still characterized by greater stability. The greater fluctuation in certain residues may indicate the greater affinity of ACE2-RBD for P.1, with phenotypic consequences ranging from greater transmissibility to greater lethality.

When analyzing the ACE2-RBD complex without any mutations, we noticed that the RMSF fluctuations (see

Figure 6 and

Table 4) for residue K417 were approximately 0.976 Å, for residue N501 they were 1.08 Å, and for amino acid E484 they were 1.31 Å. In the absence of mutations, the RMSF peak was around 2.83 Å, located at amino acid H519. However, when the P.1 strain was analyzed, there was an increase in the maximum fluctuation to 2.88 Å at amino acid A372. The RMSF analysis also suggested that regions 370-372 of the RBD experienced the greatest fluctuations as a result of P.1, indicating that they may be critical regions for changes in viral transmissibility. The α-helices, being present in naturally unstable positions, exhibited the greatest conformational fluctuations and were also directly affected by the mutations. After identifying these regions using the VMD software, we noticed that the residue Asn370 in the RBD protein presented an RMSF fluctuation of 2.58 Å in the structure containing the P.1 strain, but in its absence, there was an increase in stability to 2.28 Å. Therefore, even though this region was not directly affected by the mutations, the impacts were still reflected. It is noteworthy that this region exhibited the greatest fluctuation among all amino acids, regardless of the presence of mutations.

By analyzing the average fluctuations, the average RMSD value (see

Figure 6 and

Table 5) in the absence of mutations in the ACE2-RBD complex induced approximately (1.97 ± 0.36) Å in atomic displacement and average RMSF fluctuations of (1.28 ± 0.51) Å. On the other hand, in the presence of mutations in the P.1 lineage, the mean RMSD increased to (2.01 ± 0.29) Å, while the mean RMSF value decreased to (1.13 ± 0.46) Å. Higher RMSF values were found in the loops, possibly because they are poorly defined regions. Thus, the higher RMSD in the absence of mutations may be associated with a greater probability of Spike protein detachment from the ACE2 receptor interface. Therefore, these data possibly reflect an increase in the ACE2-RBD interaction due to smaller RMSD shifts as a result of the multiple mutations that make up the P.1 lineage.

Regarding the analysis of the formation of hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation for the ACE2-RBD complex (see

Table 5), it was found that the P.1 strain had an average of 201 ± 11 hydrogen bonds, while in the absence of mutations, there was a decrease to 197 ± 11 in average bonds. Unexpectedly, the number of hydrogen bonds at the ACE2-RBD interface was lower in P.1 compared to the structure without mutations, since in P.1 there were 32 bonds at the interface, while in the structure without mutations, 34 bonds were formed throughout the simulation. However, this does not allow us to conclude that the structural stability of P.1 is lower. This is because only two bonds are predominant in the complex, where for P.1, the formation of ACE2:Gly502 → RBD:Lys353 occurred with an incidence of 55.77%, in addition to ACE2:Tyr83 → RBD:Asn487 with 43.75%. When compared to the structure without mutations, the frequency is lower, with ACE2:Tyr83 → Asn487 at 54.26% and ACE2:Lys417 → RBD:Asp30 at 52.28%.

For instance, the E484K mutation in the RBD-antibody P2B-2F6 complex (PDB ID: 7BWJ) increased stability from (1.59 ± 0.71) Å to (1.43 ± 0.52) Å. In contrast, the K417N mutation exhibited destabilizing behavior, transitioning from 1.139 Å to 1.543 Å. Similarly, the N501Y mutation caused a stability decrease, shifting from 1.653 Å to 2.154 Å. These results suggest that the P.1 variant induces reduced stability in neutralizing antibody interactions, reflecting a lower interaction affinity.

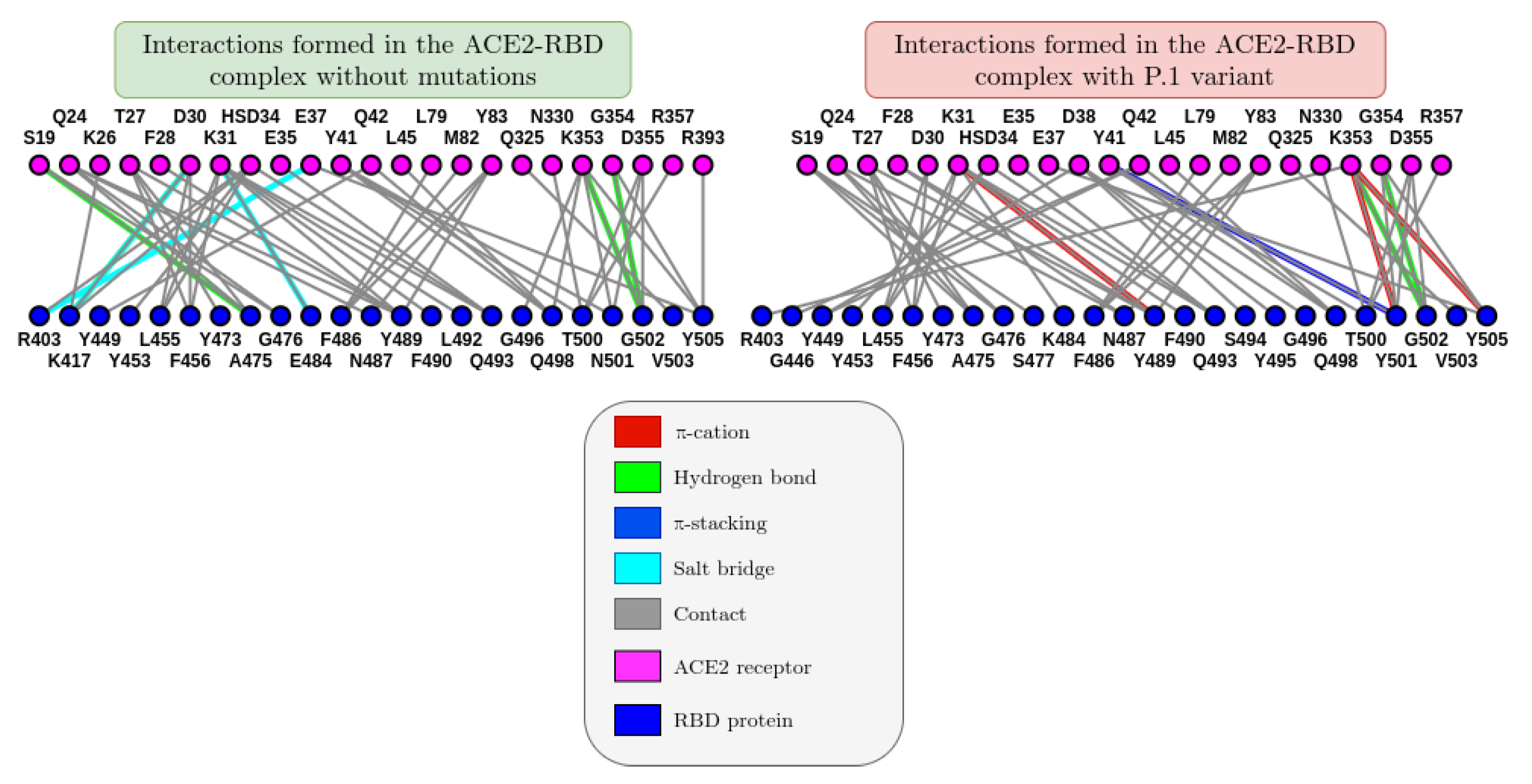

When constructing a 2D graph (see graph_ACE2_RBD) for residue interactions based on the last frame of molecular dynamics, we can better visualize the impact of mutations on the ACE2-RBD and antibody-antigen interaction. It was observed that, in the presence of the P.1 variant, three cation-π interactions (in red) formed, in addition to one π-stacking interaction (in dark blue). It is important to note that although interactions tend to change throughout the molecular dynamics, the last frame was chosen to provide more consistent results.

Figure 8.

Comparison between the graphs of the interaction between the amino acids of the ACE2 receptor with those of the RBD protein referring to the last one of the crystallographic structure PDB ID: 6M0J. The images were generated on the ICn3D online platform (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/icn3d/).

Figure 8.

Comparison between the graphs of the interaction between the amino acids of the ACE2 receptor with those of the RBD protein referring to the last one of the crystallographic structure PDB ID: 6M0J. The images were generated on the ICn3D online platform (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/icn3d/).

4. Discussion

The K417T mutation that emerged in Amazonas generated an unexpected destabilization in ACE2-Spike recognition in addition to high conformational entropy, which, although it may decrease the probability of cellular invasion, could perhaps hinder the recognition of the immune response generated by vaccines according to [

37,

38,

39,

40]. In addition, the critical destabilization due to K417T could be correlated with the unprecedented increase in infections and deaths in Amazonas due to COVID-19 in January and February 2021.

It should be noted that in the results presented in (

Table 2), a negative value for the stability/affinity (Δ) indicates that the mutation interacts more spontaneously and favorably compared to the structure without mutations [

16]. Thus, it becomes clear that the N501Y mutation is one of the most favorable for structural stability in the ACE2-RBD interaction. The mutation R190S ranks first in terms of structural stability; however, it fortunately did not affect the RBD region and therefore did not generate significant phenotypic changes.

A notable observation regarding the 11 mutations constituting the P.1 variant is that only the three most critical ones—K417T, N501Y, and E484K—which directly affected the RBD region, presented non-zero affinity changes. This is because these critical mutations were located near the ACE2-RBD interface, directly impacting interaction affinity. It was observed that electrostatic interactions increased drastically due to the E484K mutation, although this did not significantly impact the affinity and stability of the interaction.

In addition to the RMSD values of the P.1 variant being statistically significant (see

Figure 6), we noticed that they are much greater than the standard deviation of the simulations, and therefore we can conclude that these differences in structural stability in the ACE2-RBD interaction are not only due to chance, and that in fact the mutations present in these variants impacted the molecular recognition of the virus by the human ACE2 receptor.

These results reflect that perhaps the virus is seeking to benefit by increasing structural stability in the ACE2-Spike interaction. A curious point is that not all mutations necessarily contribute to greater stability or affinity in the ACE2-Spike interaction. This may be an indication of the stochastic behavior of mutations, although natural selection favors some mutations over others.

We also studied the stability of mutations in the P.1 variant using MM-GBSA energy decomposition. According to the results (see Supplementary Material), the N501Y mutation contributed most significantly to structural stability in the ACE2-RBD interaction. Consequently, it is regarded as the most concerning mutation, with a strong correlation to changes in transmissibility and lethality. Unexpectedly, the K417T mutation was less critical compared to other mutations present in SARS-CoV-2 variants, as indicated by lower spontaneous energy contributions in ΔEVdW, ΔGsolvation, and ΔEelec.

Within the P.1 variant, the E484K mutation was particularly alarming, as it induced an 11.136 kcal/mol decrease in the antibody-antigen interaction affinity. Additionally, the N501Y mutation favored structural affinity in the ACE2-Spike interaction, showing an increase of 7.969 kcal/mol. Initially, the R190S mutation was suspected to be worrisome in terms of structural stability; however, it did not affect the RBD region and therefore did not result in significant phenotypic changes. Among the 11 mutations in the P.1 variant, the three most critical ones—K417T, N501Y, and E484K—directly affected the RBD region. These were the only mutations to exhibit non-zero alterations in interaction affinity, as they were located near the ACE2-RBD interface, directly impacting binding affinity.

From the electrostatic surface distribution (see

Figure 6), calculated using the APBS (Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver) algorithm [

41], the P.1 variant showed a charge distribution of (-615.814 kT to +529.056 kT) for the ACE2-RBD complex (PDB ID: 6M0J). In contrast, the Omicron variant exhibited a slightly more negative charge distribution (-596.088 kT to +489.084 kT) when averaged over extreme values.

Through molecular dynamics simulations, we also evaluated the impact of the P.1 lineage on the efficacy of neutralizing antibodies in interacting with the Spike protein (RBD). The antibody studied, P2B-2F6, is naturally produced by the human body in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is not synthetically manufactured due to the high production costs of monoclonal antibodies.

Additionally, there was a decrease in one salt bridge during MD simulations. The RBD + P2B-2F6 complex (PDB ID: 7BWJ) lost interactions between RBD:Glu484 and Heavy Chain:Arg112, as well as between RBD:Glu484 and Light Chain:Lys55, while forming an interaction between RBD:Lys484 and Light Chain:Glu52. This reflects a potential reduction in neutralizing antibody efficacy due to greater instability in the antibody-antigen complex.

Alignment of the crystallographic structure of the RBD + P2B-2F6 complex (PDB ID: 7BWJ) with the final molecular dynamics frame of the P.1 variant yielded an RMSD value of 2.5636 Å, indicating substantial conformational changes and, consequently, increased instability.

Although we can conclude from the results of this research that the virus has been seeking greater structural stability, it is still very difficult to predict whether the increase in the stability/affinity of the ACE2-RBD complex will impact transmissibility, lethality, or some other phenotypic effect. Therefore, it is not possible to estimate the evolutionary trajectory of SARS-CoV-2 solely from these results. However, there does seem to be a tendency for each emergence of a new variant of concern to gradually increase this interaction stability. Therefore, if the virus follows a trajectory similar to the Spanish flu of 1918, stability will reflect an increase in transmissibility until it reaches a maximum peak, thus decreasing the probability of new variants, while its lethality will be equivalent to a common flu.

5. Conclusions

In general, the P.1 variant led to greater stabilization of the ACE2-RBD complex, as supported by three molecular dynamics analyses. The average RMSF values, increased hydrogen bond formation, and reduced solvent exposure, measured by the SASA value, corroborate this. These results reflect lower entropic penalty and, therefore, greater susceptibility to seasonal influences, along with a possible increase in interaction affinity and a higher likelihood of cellular entry. Through MM-PBSA energy decomposition, we observed that Van der Waals interactions predominated and were more favorable when the structure contained mutations from the P.1 variant. Consequently, the variants are likely to persist for some time due to evolutionary pressure, as they benefit the virus. This may explain the convergence of certain mutations, such as E484K and N501Y, which were theoretically explained through molecular dynamics. This research showed a decrease in hydrogen bond formation in the P.1 variant. The P.1 variant remains recognizable by the immune system, and although the efficacy of the P2B-2F6 antibody induced by vaccines may be diminished according to molecular dynamics results, there are no conclusive findings in the literature suggesting its complete neutralization. As long as we do not fully stop the virus, the emergence of new variants remains imminent. Therefore, widespread vaccination is essential for the eradication of the pandemic.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) under grant 136222/2020-0 as a scientific initiation scholarship. This research was funded in part by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Financial Code 001, as well as funding from the Amazonas State Research Support Foundation (FAPEAM) under codes POSGRAD 2021-2022/FAPEAM and PRODOC/FAPEAM003-2022.

Author Contributions

Micael D. L. Oliveira - Developed the research and conducted all molecular dynamics simulations, and is responsible for the integrity of the data and discussion. Caroline Honaiser - reviewed the scientific article and suggested relevant changes for its understanding. Isabelle B. Cordeiro: contributed significantly to the review process of the work, suggesting new ideas and computational experiments. Ana C. O. Lima: played a key role throughout the review process of this research and provided valuable insights into the discussion of the results. Nathalia S. Faria – Large contribution to the molecular dynamics methodology. Jonathas N. Silva: was responsible for validating all the results and discussions conducted in the study. Kelson M. T. Oliveira - led the research, offering full support for its execution.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all those who directly or indirectly contributed to the completion of this research. We also thank the healthcare professionals and researchers who tirelessly fought against the COVID-19 pandemic by providing invaluable insights and data that made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACE2 |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| RBD |

Receptor binding-domain |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| MM-GBSA |

Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area |

| RMSD |

Root-mean square-deviation |

| RMSF |

Root-mean square-fluctuation |

| SASA |

Solvent Accessible Surface Area |

| Rgyr |

Radius of gyration |

References

- Naveca, F.G.; Nascimento, V.; de Souza, V.C.; Corado, A.d.L.; Nascimento, F.; Silva, G.; Costa, Á.; Duarte, D.; Pessoa, K.; Mejía, M.; et al. COVID-19 in Amazonas, Brazil, was driven by the persistence of endemic lineages and P.1 emergence. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, N.R.; Mellan, T.A.; Whittaker, C.; Claro, I.M.; Candido, D.D.S.; Mishra, S.; Crispim, M.A.E.; Sales, F.C.S.; Hawryluk, I.; McCrone, J.T.; et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 2021, 372, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, G.S.; Silva, J.d.M.; Pinheiro-Silva, R.; Barbosa, A.N.; Santos, L.C.; Ramalho, A.d.P.Q.; Alves, C.E.d.C.; da Silva, D.F.; de Oliveira, L.C.; da Costa, A.G.; et al. Increased vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection among indigenous people living in the urban area of Manaus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, R.M.; Marquitti, F.M.D.; Ferreira, L.S.; Borges, M.E.; da Silva, R.L.P.; Canton, O.; Portella, T.P.; Poloni, S.; Franco, C.; Plucinski, M.M.; et al. Model-based estimation of transmissibility and reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 P.1 variant. Commun. Med. 2021, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliam, J.R.C.; van Schalkwyk, C.; Govender, N.; von Gottberg, A.; Cohen, C.; Groome, M.J.; Dushoff, J.; Mlisana, K.; Moultrie, H. Increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection associated with emergence of Omicron in South Africa. Science 2022, 376, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint J, Racaniello VR, Rall GF, Shalka AM. Principles of Virology. Em: 4o ed American Society for Microbiology; 2015. p. 321–7.

- Resende, P.C.; Bezerra, J.F.; de Vasconcelos, R.H.T.; Arantes, I.; Appolinario, L.; Mendonça, A.C.; Paixao, A.C.; Rodrigues, A.C.D.; et al. Spike E484K mutation in the first SARS-CoV-2 reinfection case confirmed in Brazil, 2020. 2021. Available online: https://virological.org/t/Spike-e484k-mutation-in-the-first-sars-cov-2-reinfection-case-confirmed-in-brazil-2020/584 (accessed on day month year).

- Greaney, A.J.; Loes, A.N.; Crawford, K.H.; Starr, T.N.; Malone, K.D.; Chu, H.Y.; Bloom, J.D. Comprehensive mapping of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human plasma antibodies. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 463–476.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Han, W.; Hong, X.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 trimeric spike glycoprotein in complex with receptor ACE2 revealed by cryo-EM. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejnirattisai W, Zhou D, Supasa P, Liu C, Mentzer AJ, Ginn HM, et al. Antibody evasion by the P.1 strain of SARS-CoV-2. Cell. maio de 2021;184(11):2939-2954.e9.

- Burley, S.K.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Bittrich, S.; Chen, L.; Crichlow, G.V.; Christie, C.H.; Dalenberg, K.; Di Costanzo, L.; Duarte, J.M.; et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank: powerful new tools for exploring 3D structures of biological macromolecules for basic and applied research and education in fundamental biology, biomedicine, biotechnology, bioengineering and energy sciences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D437–D451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, E.; Fariselli, P.; Casadio, R. I-Mutant2.0: predicting stability changes upon mutation from the protein sequence or structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W306–W310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Han, W.; Hong, X.; Wang, Y.; Hong, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Conformational dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 trimeric spike glycoprotein in complex with receptor ACE2 revealed by cryo-EM. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, L.; Perez, L.V.; Sheward, D.J.; Das, H.; Schulte, T.; Moliner-Morro, A.; Corcoran, M.; Achour, A.; Hedestam, G.B.K.; Hällberg, B.M.; et al. An alpaca nanobody neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 by blocking receptor interaction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. E. Shaw Research. Schrödinger Release 2021-2: Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, New York, NY, 2021. Maestro-Desmond Interoperability Tools, Schrödinger, New York, NY, 2021. New York; 2021.

- Beard, H.; Cholleti, A.; Pearlman, D.; Sherman, W.; Loving, K.A. Applying Physics-Based Scoring to Calculate Free Energies of Binding for Single Amino Acid Mutations in Protein-Protein Complexes. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e82849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Ascher, D.B.; Blundell, T.L. mCSM: predicting the effects of mutations in proteins using graph-based signatures. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.H.; Pires, D.E.; Ascher, D.B. DynaMut2: Assessing changes in stability and flexibility upon single and multiple point missense mutations. Protein Sci. 2020, 30, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Ascher, D.B.; Blundell, T.L. DUET: a server for predicting effects of mutations on protein stability using an integrated computational approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W314–W319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Ge, J.; Yu, J.; Shan, S.; Zhou, H.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, B.; Zhang, Q.; Ge, J.; Wang, R.; Sun, J.; Ge, X.; Yu, J.; Shan, S.; Zhou, B.; Song, S.; et al. Human neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature 2020, 584, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, L. Schrödinger Release 2021-2. New York; 2021.

- Ribeiro J, V. , Bernardi RC, Rudack T, Stone JE, Phillips JC, Freddolino PL, et al. QwikMD — Integrative Molecular Dynamics Toolkit for Novices and Experts. Sci Rep. 24 de maio de 2016;6(1):26536.

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, P.; Nilsson, L. Structure and Dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E Water Models at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 9954–9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Mackerell, A.D., Jr. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckerman, M.; Berne, B.J.; Martyna, G.J. Reversible multiple time scale molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.J.; Holian, B.L. The Nose–Hoover thermostat. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 4069–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, H.G. Accuracy and efficiency of the particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 3668–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kr utler V, van Gunsteren WF, H nenberger PH. A fast SHAKE algorithm to solve distance constraint equations for small molecules in molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 15 de abril de 2001;22(5):501–8.

- Phillips, J.C.; Hardy, D.J.; Maia, J.D.C.; Stone, J.E.; Ribeiro, J.V.; Bernardi, R.C.; Buch, R.; Fiorin, G.; Hénin, J.; Jiang, W.; et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 044130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancien, F.; Pucci, F.; Godfroid, M.; Rooman, M. Prediction and interpretation of deleterious coding variants in terms of protein structural stability. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimer, J.; Hofer, H.; Fritz, M.; Wegenkittl, S.; Lackner, P. MAESTRO - multi agent stability prediction upon point mutations. BMC Bioinform. 2015, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krissinel, E. Crystal contacts as nature's docking solutions. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 31, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P.; Li, B.; Huang, S.-Y. HDOCK: a web server for protein–protein and protein–DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W365–W373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidman-Duhovny, D.; Inbar, Y.; Nussinov, R.; Wolfson, H.J. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W363–W367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socher, E.; Heger, L.; Paulsen, F.; Zunke, F.; Arnold, P. Molecular dynamics simulations of the delta and omicron SARS-CoV-2 spike – ACE2 complexes reveal distinct changes between both variants. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitò, L.; Rujan, R.; Reynolds, C.A.; Deganutti, G. Molecular dynamics studies reveal structural and functional features of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. BioEssays 2022, 44, e2200060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, S.-P.; Yang, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-Y. Unraveling the binding mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 variants through molecular simulations. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitsillou, E.; Liang, J.J.; Beh, R.C.; Hung, A.; Karagiannis, T.C. Molecular dynamics simulations highlight the altered binding landscape at the spike-ACE2 interface between the Delta and Omicron variants compared to the SARS-CoV-2 original strain. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 149, 106035–106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurrus, E.; Engel, D.; Star, K.; Monson, K.; Brandi, J.; Felberg, L.E.; Brookes, D.H.; Wilson, L.; Chen, J.; Liles, K.; et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein Sci. 2017, 27, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).