1. Introduction

The involvement of oral bacteria with pathogenesis of distant organs have been shown [

1,

2]. Dysbiosis is known as pathological changes (type and/or proportion of bacteria) of commensal bacteria in some organs, which causes various diseases [

3]. Recently, several reports have shown the association of oral bacteria or oral dysbiosis with diseases of other organs by the metagenome analysis and the molecular biological analysis [

4,

5].

One known disease closely associated with oral bacteria is infectious endocarditis (IE), which causes verrucae on the endocardium. Aortic valve disease (AV) is a known cause of IE. Among aortic valve diseases (aortic stenosis (AS) and aortic regurgitation (AR)), AS is a condition in which blood flow from the left ventricle to the ascending aorta during systole is obstructed due to narrowing of the aortic valve orifice [

6]. The causes include idiopathic degenerative sclerosis with calcification (congenital bicuspid valves prone to sclerosis) and rheumatic fever. Valve replacement or valvuloplasty is indicated when stenosis and regurgitation after AS/AR are severe [

7].

We have previously reported that more than 60% of bacteria identified in the blood cultures of patients with IE are recognized as oral bacteria [

8]. In our previous study, bacterial cultures of blood from patients with IE were compared with dental plaque cultures in the oral cavity to verify the identity of the oral bacteria and the causative bacteria of IE. The culture test was able to detect identical bacterial species; however, only in one case, the bacteria detected from dental plaque and blood had a complete match in the 16s rRNA gene sequence [

8]. Although this study showed indirect evidence for so-called focal dental infections in distant organs, it was difficult to identify the causative bacteria by comparing the limited number of clones detected in the bacterial cultures.

In this study, we attempted to detect bacteria in the resected aortic valve, and analyze the hierarchy of bacterial species in the resected aortic valve by metagenomic analysis. Simultaneously, we analyzed the hierarchy of bacterial species in subgingival dental plaque, which causes periodontal disease, and in swabs of the tongue dorsal surface, which reflects the flora of the oral cavity in the same patients. Then we verified whether oral bacteria reached the aortic valve by directly comparing their gene sequences.

2. Results

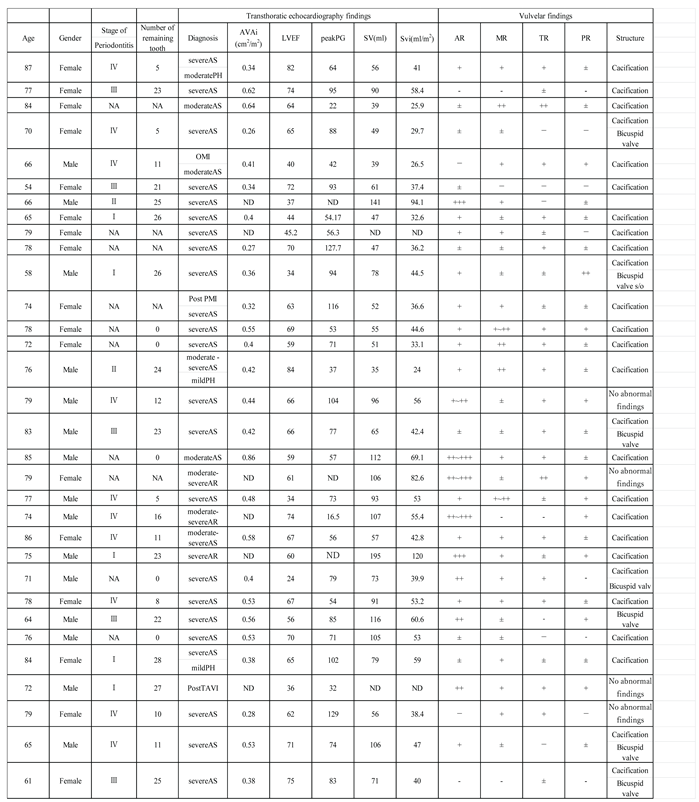

2.1. Periodontitis and Aortic Valve Condition in Patients with Aortic Valve Disease

Thirty-two patients with AS or AR who underwent aortic valve replacement between May 2020 and March 2021 at Dokkyo Medical University Hospital were enrolled in this study. The patients’ demographic data are presented in

Table 1. These patients underwent oral examination and management before surgery, and periodontal disease was staged based on an intraoral examination, panoramic radiograph, and periodontal pocket depth [

9].

Of the 32 patients, 15 were males, and 17 were females, with an average age of 74.15 years, 28 had severe AS, 2 had moderate to severe AS, and 2 had severe AS. Five patients had periodontal disease stage I, 2 patients had stage II, 5 had stage III, 10 patients had stage IV, and 10 patients were edentulous (

Table 1). Twenty-six patients had calcification in the aortic valves and seven were suspected to have bicuspid valves based on transthoracic echocardiography. AVAi averaged 0.45±0.0012, SV averaged 78.93±78.60, and SVi averaged 49.23±27.57 (

Table 1).

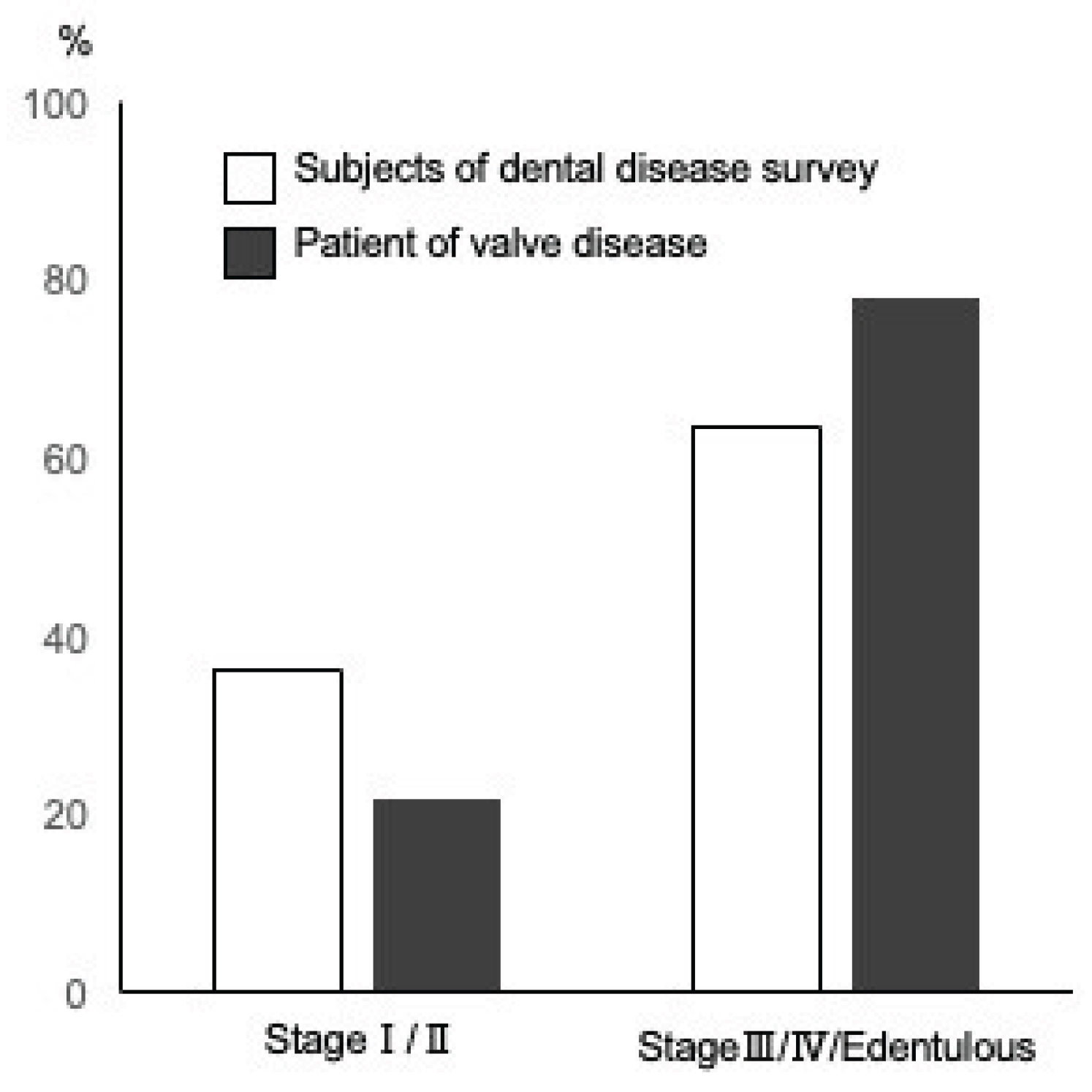

We compared the severity of periodontitis in the patients in this study and of the same age group from the results of the Survey of Actual Conditions of Dental Diseases in Japan

[10]; 36.5% of the patients were classified as having mild disease in stages I and II, while 25.9% of patients with aortic disease were in the same category. In contrast, the percentage of patients with advanced periodontitis in stages III and IV and the edentulous jaw group was 74.1% in patients with aortic disease and 63.5% in the Survey of Dental Diseases in Japan (

Figure 1). Although statistical comparisons were difficult because of the large difference in population size (32 patients in this study and 2378 patients in the survey), there was a tendency for more patients with aortic valve disease to have stage III or IV advanced periodontitis and edentulous jaws (odds ratio 1.602 [95%CI: 0.709 – 3.805]).

2.2. Measurement of Serum Antibody Titer Against Periodontal Pathogenic Bacteria in Patients with Aortic Valve Disease

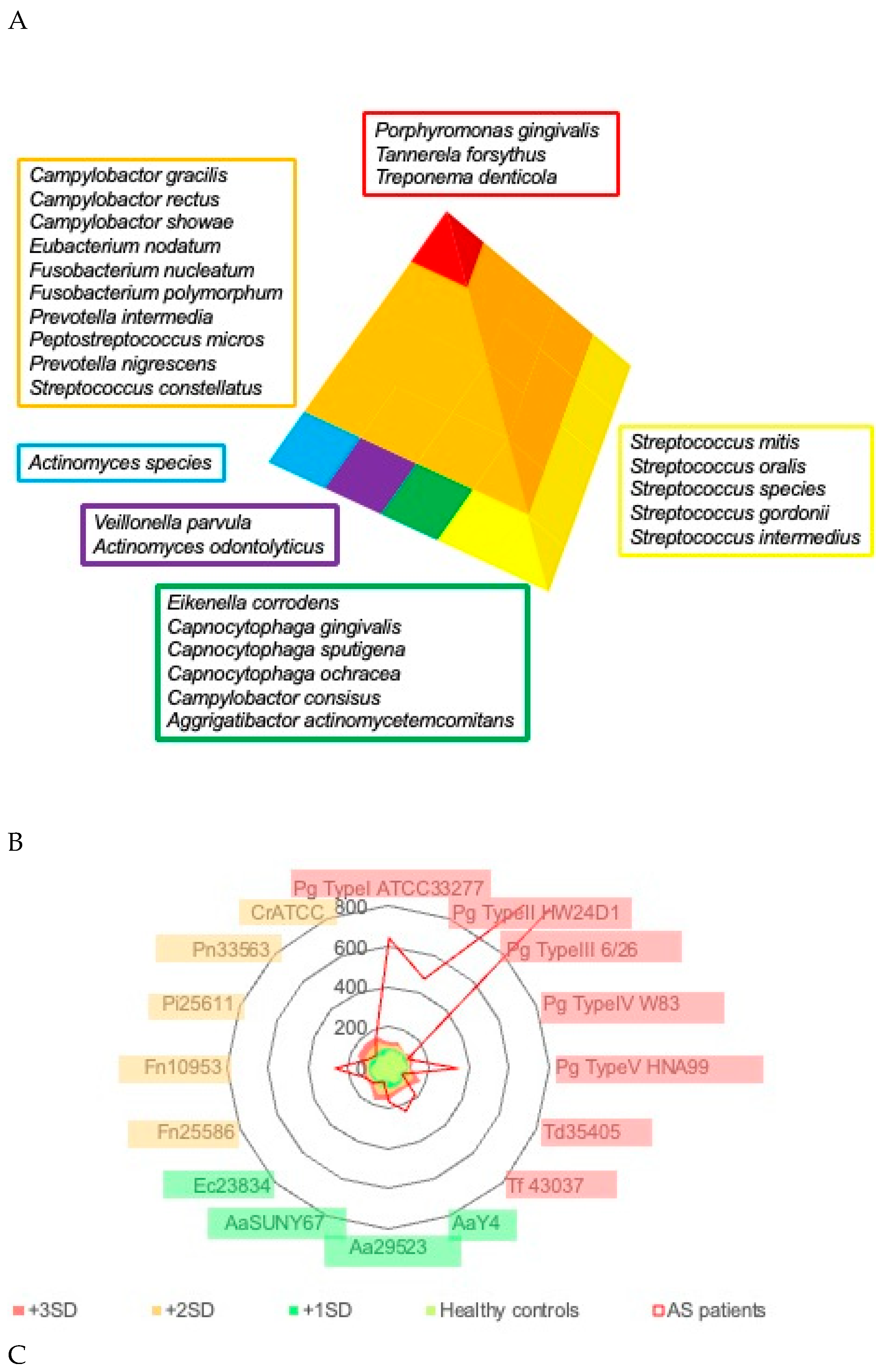

Periodontal pathogenic bacteria are classified into several categories (color-coded as red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple complexes) based on their importance in clinical pathogenesis by Socransky et al. [

13], and bacteria classified in the red complex (

Porphyromonas gingivalis,

Tannerella forsythia,

Treponema denticola) are considered to be important for the pathogenesis of periodontitis (

Figure 2A). The radar chart in

Figure 2B shows the mean antibody titers of various periodontal pathogenic bacteria in the serum of patients with aortic valve disease. Antibody titers against bacteria in the red complex category were significantly elevated in patients compared to healthy controls. A comparison of serum antibody titers against red complex bacteria by periodontitis stage in patients with aortic valve disease showed that antibody titers tended to increase with the progression of the periodontitis stage, and antibody titers to red-complex bacteria were positively correlated with the periodontitis stage (

Figure 2C). A weak but positive correlation was also observed between the antibody titer against the bacteria of the orange complex and periodontitis stage (

Figure 2C). Antibody titers against the bacteria of the blue and green complexes were weakly correlated with the periodontitis stage, although there was a tendency for antibody titers to increase.

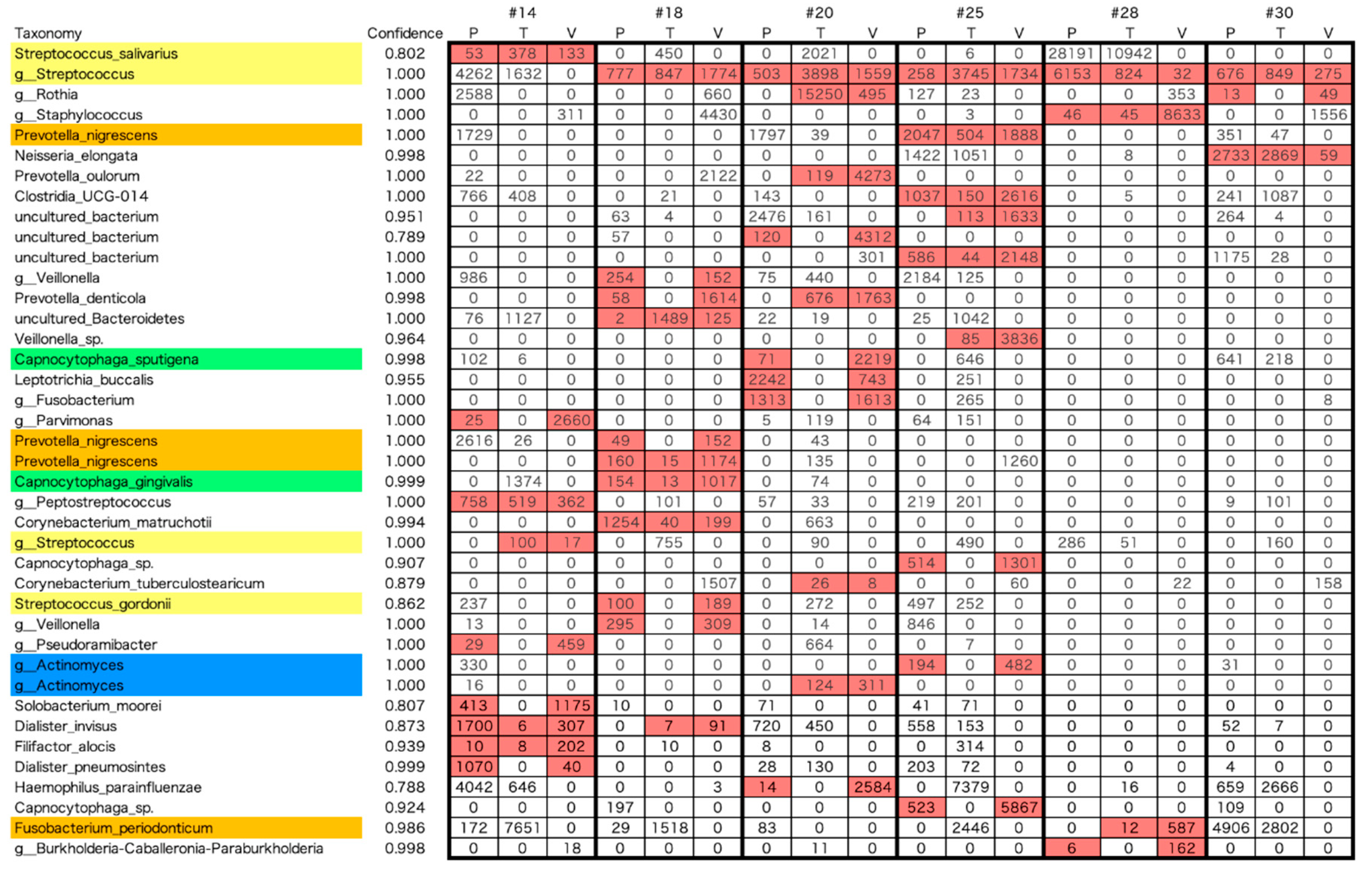

2.3. Taxonomy Analysis

Bacterial 16S rRNA was detected in 12 aortic valves of 32 patients examined using PCR. We obtained sufficient DNA for amplicon sequencing analysis in six cases. Taxonomic analysis was performed to identify ASVs with > 70% homology. The flora composition based on the read count of each ASV is shown in (Fig. S1). Surprisingly, several bacterial species were detected in the resected aortic valve. As expected, the flora of the tongue and periodontal pocket dental plaque were similar in many cases; however, the flora detected in the aortic valve showed a different pattern.

2.4. α-Diversity and β-Diversity

Examination of α-diversity and β-diversity indicated that the bacterial flora in the resected aortic valve tended to be similar, although not identical, to the composition of the oral flora. We examined the α-diversity of the plaques, tongue swabs, and excised aortic valves (Fig. S2). There was no significant difference in the diversity within each flora detected at each site (p = 0.547). This suggests that a wide variety of bacteria are present in the resected aortic valve, and that, like the oral environment, the flora may be diverse. When we examined the β-diversity among the flora (Fig. S3), we found that the vectors of diversity of the flora in the three groups were different (p = 0·001): plaque, tongue, and resected aortic valve. Among the resected aortic valves, we recognized two groups with different vectors of diversity, and among the two groups, three cases, AS 14, 20, and 25, were considered to have flora similar to those of the oral-derived specimens, being closer to the oral bacteria. The frequency of detection of ASV in AS 18, 28, and 30 was higher than that in the Unassigned group, which may have been a factor in the division into two groups. (Although the Gene analyzer detected the expected size of PCR products in these three samples at the 1stPCR stage, it was insufficient in quantity. As the primary purpose of this study was to examine whether bacteria were present in the resected aortic valve, we performed 1st PCR again using the 1st PCR product as a PCR template. This increased nonspecific amplification, and unassigned ASVs became more frequent. However, from the viewpoint of Axis 2 and 3, there was a similar trend to that of the oral-derived specimens.

2.5. Characteristics of Bacteria Detected in the Tongue, Dental Plaque, and Resected Aortic Valve

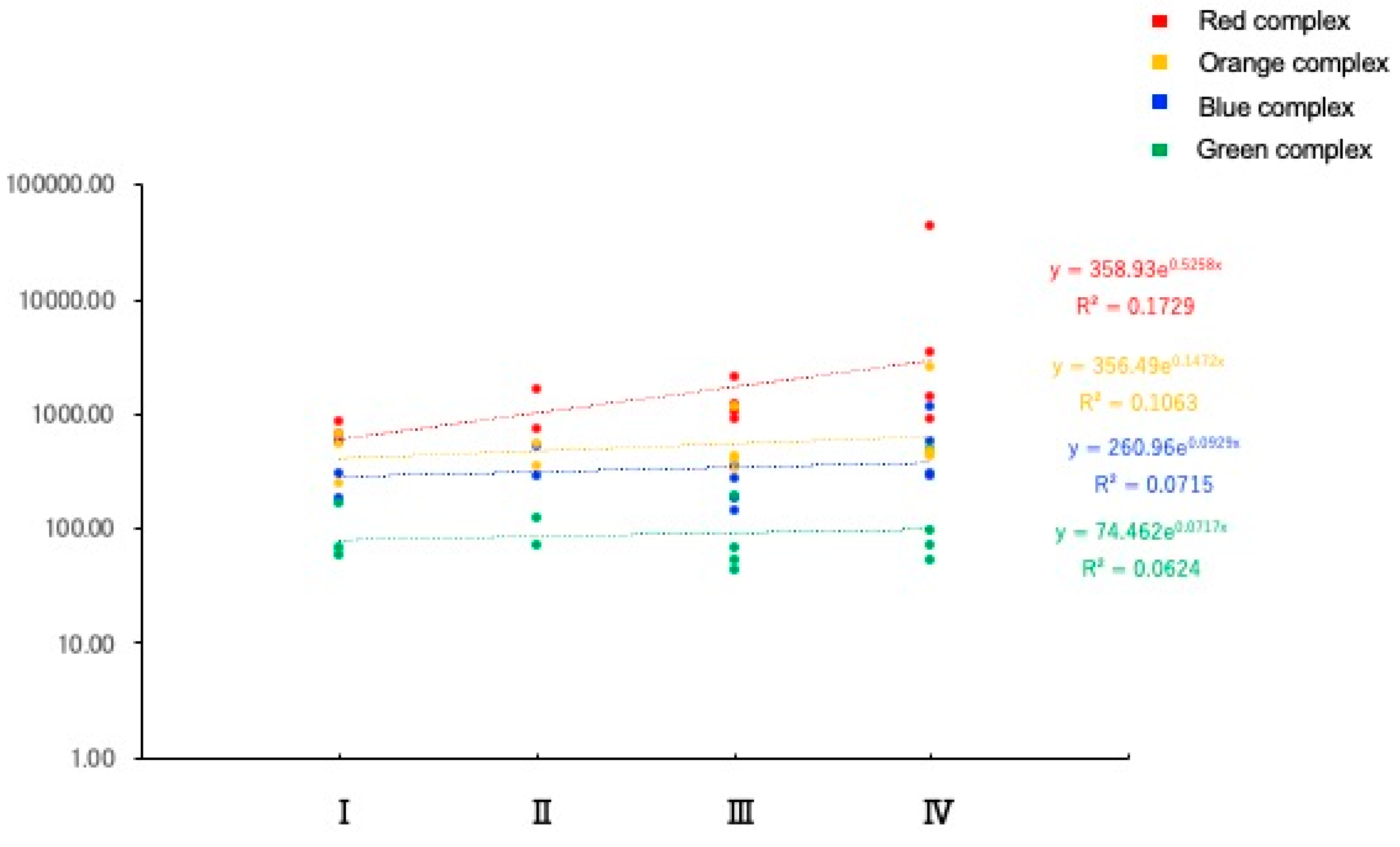

The 195 bacteria detected in the tongue, dental plaque, and resected aortic valve specimens were ranked according to read count. The lists of the top 25 bacteria are shown in

Figure 3A, B, and C. Among the bacteria listed for resected aortic valves, 48% (16-64%) of the 35 species were associated with the oral cavity, and 18% (4-28%) were periodontal pathogenic bacteria (color-coded as red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple) according to Socransky’s classification [

14]. In cases 20, 25, and 30, a significant number of red and orange bacteria were included in the flora considered endemic to the oral cavity detected on the dorsal surface of the tongue. In cases 20 and 25, red and orange bacteria were detected in the aortic valve. In Case 30, neither red nor orange complex bacteria were detected in the aortic valve. In cases 14, 18, and 28, the bacterial flora detected on the dorsal surface of the tongue contained no red and only a few orange bacteria. In contrast, red and orange bacteria were detected in the aortic valve.

2.6. Identification of the Same Bacterial Clones in the Tongue, Dental Plaque, and Resected Aortic Valve

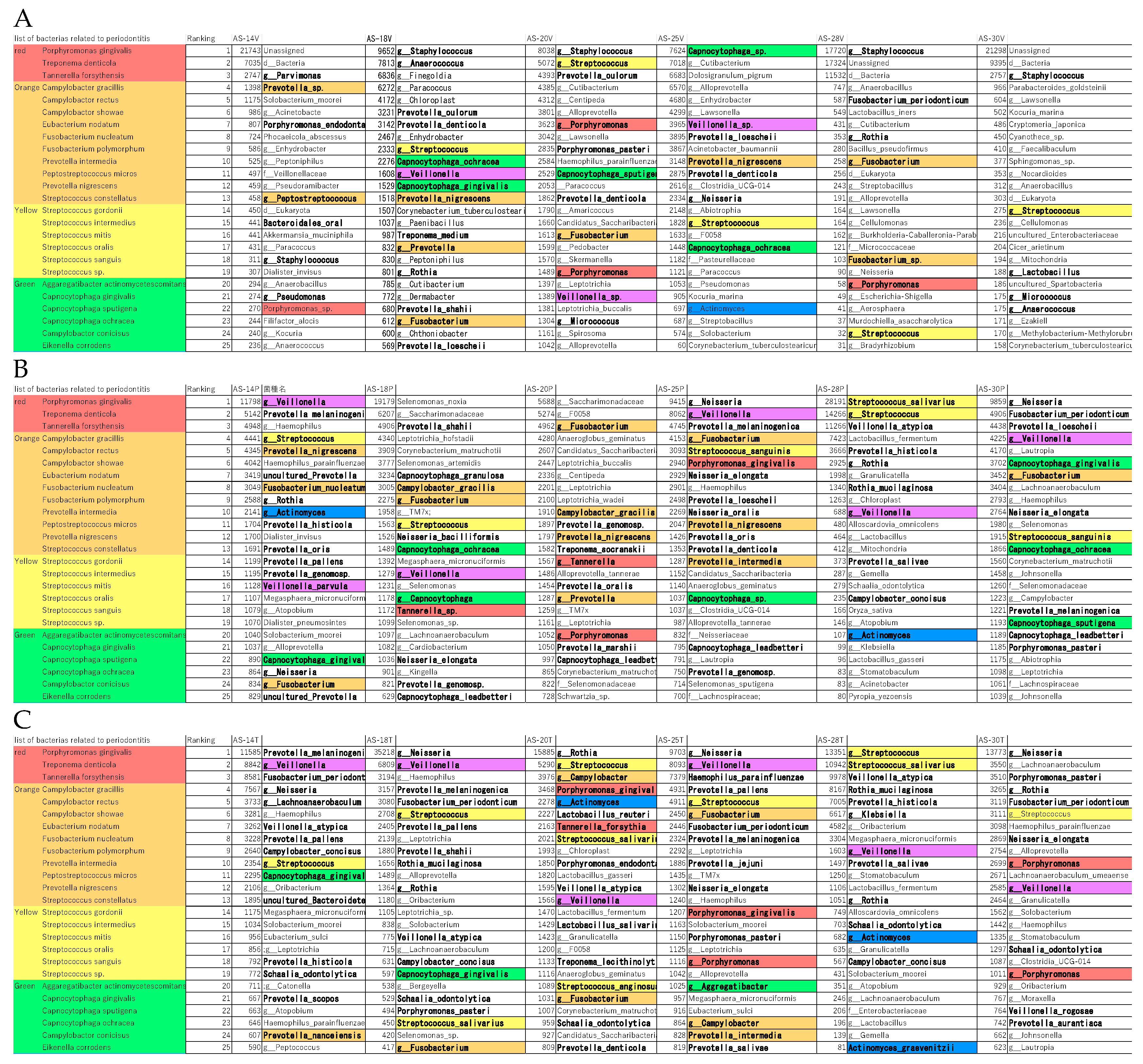

The same ASV was detected in the tongue, dental plaque, and the resected aortic valve (

Figure 4). This indicates that bacteria with the same genetic background, that is, the same clones of the bacteria, are present in the oral cavity and aortic valve. A total of 2,524 independent ASVs were detected in all samples. Forty bacteria were found to have identical ASVs in the excised aortic valve and oral cavity (dorsal surface of the tongue and/or dental plaque). Fourteen bacteria were detected with identical ASVs from the three sites of the tongue, dental plaque, and excised aortic valve, and 26 bacteria were detected with identical ASVs from the excised aortic valve and tongue or dental plaque (

Figure 4). Twelve of the 40 bacteria were periodontal pathogenic bacteria, according to Socransky’s classification.

3. Discussion

In this study, we found the following points: [

1] patients with aortic valve disease were more likely to have periodontitis and more of them had severe disease or edentulous jaws; [

2] serum titers of antibodies against periodontal pathogenic bacteria and red complexes were high in patients with aortic valve disease; [

3] Bacterial DNA was detectable in the resected aortic valve of 12/32 (37.5%) patients with aortic valve disease; [

4] a wide variety of bacteria were detected in the resected aortic valves of 6 patients who underwent amplicon sequencing analysis; [

5] 40 identical bacteria were found in both the resected aortic valve and oral bacterial ASVs; [

6] among the 40 identical bacteria,12 were periodontal pathogenic bacteria according to Socransky’s classification. These results strongly suggests that in patients with current periodontitis or previous periodontitis, oral bacteria invade the body and settle in the aortic valve via the blood stream.

In some cases (cases 20, 25, and 30), bacteria in the red and orange complexes were significant in the flora of the oral cavity. It was endemic to the oral cavity and was detected on the dorsal surface of the tongue, suggesting that dysbiosis had occurred. In cases 20 and 25, bacteria in the red and orange complexes were also detected in the aortic valve. In contrast, the dorsal surface of the tongue contained less orange complex bacteria in cases 14, 18, and 28, without red complexes. Nevertheless, red and orange complexes were detected in the aortic valve, suggesting that colonization of the aortic valve via bacteremia from periodontal bacteria in the periodontal pocket occurs even in the absence of oral bacterial dysbiosis. The identity of the bacteria detected in the oral cavity (dorsal surface of the tongue or periodontal pockets) and the aortic valve was examined, and in cases 14, 18, 20, and 25, a significant number of bacteria were detected from both sources. Only Staphylococcus and Neisseria were detected in cases 28 and 30, respectively, suggesting that oral bacteria may be less involved.

In many cases, Streptococcus, which appears to be an early colonizer, and subsequent dental plaque constituent bacteria were also present in the aortic valve, suggesting that they may be involved in bacterial colonization. However, some ASV species that were detected in the resected aortic valve were not detected in the oral cavity. Because oral dysbiosis has been present for a considerable period and the timing of bacterial invasion and settlement in the aortic valve does not always coincide because of repeated acute conversion and remission of periodontal disease, it is thought that there were bacterial clones that existed in the oral cavity but whose ASVs did not coincide.

Although there have been many reports on the detection of oral bacteria in distant organs using PCR [

8,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], a few reports have verified whether the bacteria detected in the oral cavity and distant organs are the same clone [

8]. For example, Zeibolz et al. examined the presence of pathogenic periodontal bacteria in aortic valves using PCR [

15]. The relationship between oral bacteria and diseases of distant organs is also well known. Periodontal pathogens are known to be risk factors for atherosclerosis [

16,

17] and, as a result, are thought to be involved in the development of several cardiac diseases, including infective endocarditis [

18]. Streptococcus mutans, a well-known caries-causing bacterium, is involved in the development of cerebral hemorrhage [

19,

20,

21]. Although these findings are valuable as circumstantial evidence that oral bacteria can infect distant organs via the bloodstream, it is not easy to examine whether the diseases in oral cavity, such as periodontitis and dental caries can be the gateway to entry. In this study, we found that identical clones of bacteria were present in the oral cavity, distant organs, and the aortic valve. However, at present, we did not clarify whether oral bacteria caused aortic valve disease or colonized the injured aortic valve.

The importance of oral management during surgery and several medical treatments have recently been reported [

22]. However, there is no clear direct evidence that bacteria in the oral cavity can induce secondary infections in other organs. Accumulated experience strongly suggests that oral lesions (dental caries reaching the root canal or periodontal disease) may serve as a gateway for bacterial invasion into the body, and studies providing direct evidence have increased. In this study, we detected bacteria with the same genetic background, that is, the same clone of bacteria, in the oral cavity and resected aortic valve of patients with aortic valve disease. Oral dysbiosis and the resulting bacteremia may be associated with the onset or progression of aortic valve disease.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

Thirty-two patients with AS or AR who underwent aortic valve replacement between May 1, 2020 and March 31, 2021 at Dokkyo Medical University Hospital were enrolled in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dokkyo Medical University (approval no. R-37-20J). Patients were included in the study only when consent was obtained from the patient or the key person. In cases where the patients themselves could not make a decision; we explained the details of the research to the key participants in the study. In this study, we obtained genetic information from microorganisms, but not human-derived information.

4.2. Measurement of Serum Antibody Titer Against Periodontal Pathogenic Bacteria

Serum antibody titers were measured according to a previously reported [

9]. Serum from the preoperative blood collection of patients was isolated and stored at -80°C. Serum was collected from patients during surgery and stored at -80°C. Serum IgG antibody titers against periodontal pathogenic bacteria were determined by ELISA using strains of bacteria that had already been isolated and identified. The antibody titer against each bacterium was expressed as a relative value using the antibody titer in the sera of adults without advanced periodontal disease as the standard [

9]. We examined the stages of periodontitis and antibody titers against periodontal pathogenic bacteria using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The correlation between the antibody titer and stage of periodontitis was analyzed.

4.3. DNA Extraction from the Aortic Valve or Oral Bacteria

Aortic valves were stored in 1.5 ml microtubes at -80°C immediately after surgical excision. Isospin Tissue DNA (Nippon Gene Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used to extract DNA from excised aortic valves. Samples of the dorsal surface of the tongue, representing the flora of the oral cavity, were collected using cotton swabs. The swabs were rubbed on the dorsal surface of the tongue and stored in conical tubes at -80°C until DNA extraction. In addition, subgingival plaque samples were collected from sites with obvious inflammatory conditions, such as periodontitis, using a manual scaler and stored in 1.5-ml microtubes at -80°C until DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from plaque and tongue swab samples using the Isoil DNA extraction kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Nippon Gene Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The plaques were added directly to the extraction buffer, and the swab tips were cut into the extraction buffer, thoroughly agitated, and centrifuged to obtain the supernatant.

4.4. Confirmation of Bacterial DNA in the Extracted Samples

Extracted DNA was confirmed using primers against bacterial 16S rRNA. The primers used were 16S rRNA-27f: 5’-AGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’,16S rRNA-1492r: 5’-ACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’. We performed PCR on extracted DNA samples using QUICK Taq HS DyeMix (TOYOBO Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The PCR products were subjected to 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis to detect a band of approximately 1,500 bp corresponding to 16S rRNA.

4.5. 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing Analysis

For amplicon sequencing, libraries were prepared according to the Illumina 16S metagenomic sequencing library preparation protocols. 2.5 µl of microbial genomic DNA (5 ng/µL in 10 mM Microbial genomic DNA 2.5 µl (5 ng/µL in 10 mM Tris pH 8.5) was used for 1st PCR with the following primers: forward, 5’-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGAGACAGCCTAHGGGRBGCAGCAG-3,’ Reverse 5’-GTCGTGGGCTCTCGAGAGATGTGTAGTAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGGTATCTAATCC-3’. PCR was performed using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (KAPA Biosystems Inc., Washington, MA, United States) was used for PCR, and PCR products were analyzed using a Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 chip (Agilent Technologies LTD., Santa Clara, CA, United States). PCR products were purified using an Agencourt AMPure XP 60 ml kit (Beckman Coulter Co., Brea, CA, United States). Then, 2nd PCR was performed to construct a sequencing library following the Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Protocol, and the PCR products were purified and subjected to amplicon sequencing. Sample sequencing was performed using Illumina MiSeq (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) and Paired-End Sequence data detected in each sample were stored in separate FASTAQ files for Read1 and Read2. Sequence data were analyzed using the Qiime2. First, demultiplexing and denoising were performed to remove adapter sequences, linker sequences, and primer sequences.

4.6. Microbial Population Analysis

Before analysis, ASVs (Amplicon Sequence Variants) were generated by filtering, denoising, chimera check, and merging pair-reads of the sequence data according to the DADA2 workflow [

8]. The Silva dataset was used for the 16S rRNA taxonomy database [

9] and the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA was cut from the full-length sequence to adjust the dataset for analysis. The alpha diversity of each flora and beta diversity of the detected sites were examined. Kruskal-Wallis test was used for alpha diversity and evenness, and the observed features, Faith pd index, and Shannon index were used for beta diversity. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) was performed based on the distance and read count values in the phylogenetic tree of the detected fungi and PERMANOVA was used for the test.

5. Conclusions

Oral dysbiosis and the resulting bacteremia may be associated with the onset or progression of aortic valve disease.

Supplementary Materials

The supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; Y.K., E.Y., H.K.: Methodology; Y.K., E.Y., H.K.: Conceptualization; Y.K., E.Y., H.K.: Methodology; Y.K., E.Y., H.K.: Investigation; E.Y., Y.K., R.S., T.H., S.I., T.S.: Visualization; Y.K., E.Y., S.I., T.S.: Funding acquisition; E.Y., Y.K.: Project administration; Y.K., E.Y.: Supervision; H.S., S.H., H.F., S.T., C.F., S.I., T.W., H.K.: Writing – original draft; Y.K., E.Y.: Writing – review & editing; Y.K., E.Y., H.K.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP20K10123 (Y.K.), Dokkyo Medical University Grant in Aid No.1864 (E.Y.) and Dokkyo Medical University Grant in Aid No.2153 (E.Y.)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects issued by Japan Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and approved by the Ethics Committee of Dokkyo Medical University (Approval No. R-37-20J).

Informed Consent Statement

Written Informed consent was obtained from all participants. In cases where the patients themselves could not decide; we explained the details of the research to the legal guardian of the patient. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper

Data Availability Statement

Authors declare that they have no competing interests. All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the staff members of the Bacteriology Laboratory of Dokkyo Medical University Hospital for their useful advice and support regarding sample collection from the oral cavity. We also appreciate all the staff members of the Operating room of Dokkyo Medical University Hospital for their support with sample collection. We are grateful to Ms. Yuki Hirano and Ms. Mayumi Sakata for coordinating the schedule and liaison for collecting the surgical specimens.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kumar, P S. From focal sepsis to periodontal medicine: a century of exploring the role of the oral microbiome in systemic disease. Journal of Physiology. J Physiol. 2017 Jan 15;595(2):465-476. [CrossRef]

- Freire, K.; Nelson, K E.; Edlund, A. The Oral Host–Microbial Interactome: An Ecological Chronometer of Health? Trends Microbiol. 2021 Jun;29(6):551-561.

- Sampaio-Maia, B.; Caldas, I M.; Pereira, M L.; Pérez-Mongiovi, D.; Araujo, R. The Oral Microbiome in Health and Its Implication in Oral and Systemic Diseases. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2016:97:171-210.

- Yoshida, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Kuwata, H.; Nabuchi, A.; Yaso, A.; Shirota, T. Metagenomic analysis of oral plaques and aortic valve tissues reveals oral bacteria associated with aortic stenosis. Clin Oral Investig. 2023 Aug;27(8):4335-4344. [CrossRef]

- Pardo, A.; Signoriello, A.; Signoretto, C.; Messina, E.; Carelli, M.; Tessari, M.; De Manna, N D,; Rossetti, C.; Albanese,M.; Lombardo, G. Detection of Periodontal Pathogens in Oral Samples and Cardiac Specimens in Patients Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement: A Pilot Study. J Clin Med. 2021 Aug 28;10(17):3874. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Naqvi, S Y.; Giri, J.; Goldberg, S. Aortic Stenosis: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Am J Med. 2017 Mar;130(3):253-263.

- 7. Boskovski, M T.; Gleason, T G. Current Therapeutic Options in Aortic Stenosis. Circ Res. 2021 Apr 30;128(9):1398-1417. [CrossRef]

- Hakata, K.; Kawamata, H.; Imai, Y. Implication of the Oral Bacteria on the Onset of Infective Endocarditis. Dokkyo Journal of Medical Sciences.2014: 41: 103– 113. [CrossRef]

- Nishi, H.; Hosomi, N.; Ohta, K.; Aoki, S.; Nakamori, M.; Nezu, T.; Shigeishi, H.; Shintani,T.; Obayashi, T.; Ishikawa, K.; et al. Serum immunoglobulin G antibody titer to Fusobacterium nucleatum is associated with unfavorable outcome after stroke. Clin Exp Immunol. 2020 Jun;200(3):302-309. [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J R.; Dillon, M R.; Bokulich, N A.; Abnet, C C.; Al-Ghalith, G A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019 Aug;37(8):852-857.

- 11. Robeson, M S.; O’Rourke, D R.; Kaehler, B D.; Ziemski, M.; Dillon, M R.; Foster, J T.; Bokulich, N A. RESCRIPt: Reproducible sequence taxonomy reference database management. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021 Nov 8;17(11). [CrossRef]

- 12. Caton, J G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I L C.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K S.; Mealey, B L.; Papapanou, P N.; Sanz, M,; Tonetti, M S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions – Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Clin Periodontol. 2018 Jun:45 Suppl 20:S1-S8.

- 13. Japanese Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare: Heisei 28 nenn Sikasikkannjittaityousa[Dental disease survey]., 2016.

- 14. Socransky S and Haffajee A: Dental biofilms: difficult theraputic targets. Periodontology 2000 28: 12–55, 2002.

- Ziebolz, D.; Jahn, C.; Pegel, J.; Semper-Pinnecke, E.; Mausberg, R F.; Waldmann-Beushausen, R.; Schöndube,F A.; Danner, B C. Periodontal bacteria DNA findings in human cardiac tissue - Is there a link of periodontitis to heart valve disease? Int J Cardiol. 2018 Jan 15:251:74-79.

- Bartova, J.; Sommerova, P.; Lyuya-Mi, Y.; Mysak, J.; Prochazkova, J.; Duskova, J.; Janatova, T.; Podzimek, S. Periodontitis as a risk factor of atherosclerosis. J Immunol Res. 2014:2014:636893.

- Olsen, I.; Taubman, M A.; Singhrao, S K. Porphyromonas gingivalis suppresses adaptive immunity in periodontitis, atherosclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Oral Microbiol. 2016 Nov 22:8:33029.

- 18. Carrizales-Sepúlveda, E F.; Ordaz-Farías, A.; Vera-Pineda, R.; Flores-Ramírez, R. Periodontal Disease, Systemic Inflammation and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2018 Nov;27(11):1327-1334. [CrossRef]

- 19. Pyysalo, M J.; Pyysalo, L M.; Pessi, T.; Karhunen, P J.; Öhman, J E. The connection between ruptured cerebral aneurysms and odontogenic bacteria. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013 Nov;84(11):1214-8. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Ouhara, K.; Kitagawa, M.; Akutagawa, K.; Kawada-Matsuo, M.; Tamura, T.; Zhai, R.; Hamamoto, Y.; Kajiya, M.; Matsuda, S.; et al. Periapical lesion following Cnmpositive Streptococcus mutans pulp infection worsens cerebral hemorrhage onset in an SHRSP rat model . Clin Exp Immunol. 2022 Dec 31;210(3):321-330.

- Hosoki, S.; Saito, S.; Tonomura, S.; Ishiyama, H.; Yoshimoto, T.; Ikeda, S.; Ikenouchi, H.; Yamamoto,Y.;Hattori, Y.; Miwa, K.; et al. Oral Carriage of Streptococcus mutans Harboring the cnm Gene Relates to an Increased Incidence of Cerebral Microbleeds. Stroke. 2020 Dec;51(12):3632-3639. [CrossRef]

- Tsubura-Okubo, M.; Komiyama, Y.; Kamimura, R.; Sawatani, Y.; Arai, H.; Mitani, K.; Haruyama, Y.; Kobashi, G.; Ishihama, H.; Uchida, D.; Kawamata, H. Oral management with polaprezinc solution reduces adverse events in haematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Jul;50(7):906-914. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).