1. Introduction

The human microbiome represents an ecosystem of microorganisms that inhabit the human body and interact with each other based on the principles of symbiosis [

1]. The formation of the modern microbiome reflects millions of years of co-evolution between humans and microorganisms. Over time, both sides have mutually adapted, and the microbiome now plays a crucial role in both our health and the development of pathological conditions [

2].

The oral cavity harbors the second most diverse microbial ecosystem in the human body after the intestines, accommodating over 700 different species of bacteria [

3]. These bacteria inhabit various sites within the oral environment, including the teeth, tongue, periodontal structures, and cheeks, all interconnected through saliva [

4]. Interactions between the microbiome and the human host during the early stages of development play a crucial role in physiological growth and the formation of both innate and adaptive immunity, which, in turn, influences future health status [

5].

Dental biofilm is defined as a highly organized microbial community composed of cells attached to the tooth surface or to each other, embedded in an extracellular matrix [

6]. The predominant early colonizers of dental biofilm are oral streptococci, primarily from the Streptococcus mitis group, followed by gram-positive rods from the Actinomyces genus. Gradually, gram-negative cocci and rods integrate into the initially gram-positive biofilm. The microorganisms forming the dental biofilm gradually alter their phenotype in response to changing environmental conditions within the community, resulting in enhanced growth rates, adaptation, and increased pathogenic potential [

7].

Traditionally, various cultural methods have been relied upon for isolating individual microbial species and studying their interactions with the host [

8]. These methods are based on cultivating microorganisms under laboratory conditions, allowing for a detailed analysis of their biochemical and physiological characteristics, such as metabolic functions and antibiotic resistance. Although these methods are fundamental in microbiology, they have significant limitations, particularly in detecting anaerobic bacterial species, which are difficult to culture under standard laboratory conditions.

Studies indicate that traditional culturing techniques may overlook a significant portion of the oral microbiome, with estimates suggesting that over 50% of oral bacteria are considered "unculturable" using conventional approaches [

9]. Modern genetic identification methods, such as Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), which is regarded as the most effective method for detecting periodontopathogens without cultivation, can identify a wide range of species even when their quantity in the sample is minimal [

10].

A review of the global literature primarily highlights studies focused on the oral microbiome in adults, while research on children remains relatively limited, with an emphasis mainly on dental caries [

11]. This provides a strong rationale for investigating the current state of the subgingival microbiome in children in the context of their periodontal health.

The aim of this study is to investigate and compare key microorganisms of the subgingival microflora in healthy children and children with diagnosed gingival inflammation (ages 10-14).

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

The study included 73 children aged 10 to 14 years, all undergoing puberty and the formation of a permanent dentition, with no systemic diseases, no fixed orthodontic appliances, and no antibiotic use in the last three months. Informed consent was obtained from parents of all subjects involved in the study.

Children with gingival pathology were selected based on the following criteria:

After selection, the children were divided into two groups:

Methodology for Clinical Examination of Children

Each child underwent a clinical periodontal examination at four levels:

First level. General Health Status Assessment – Conducted through anamnesis to gather information on the child’s overall health.

Second level. Oral Hygiene Status Assessment – Evaluated using the Hygiene Index (HI), which measures the percentage of plaque-free surfaces. All fully erupted permanent teeth were stained with a plaque-disclosing solution. Each tooth was divided into four surfaces (vestibular, distovestibular, mesiovestibular, and oral), with plaque presence recorded as “+” and plaque absence as “-”.

Third level. Assessment of Teeth and Gingiva – Included the registration of dental status, condition of soft tissues, and presence of orthodontic anomalies.

Forth level. Gingival Sulcus Assessment – Evaluated by measuring gingival sulcus depth and the Papilla Bleeding Index (PBI). For the PBI, all fully erupted permanent teeth were probed.

Bleeding on probing was recorded as “+” (presence of bleeding) or “-” (absence of bleeding). The final PBI value was calculated as the relative percentage of bleeding points, indicating the extent of gingival inflammation.

PCR-Real Time Method for Identifying Subgingival Microorganisms

To identify subgingival microorganisms and determine their quantities, the PCR – Real-Time method was used.

For the purposes of this study, nine control strains of subgingival microorganisms were analyzed in a pooled sample: A.actinomycetemcomitans, P.gingivalis, T.denticola, T.forsythia, P.intermedia, P.(micromonas)micros, F.nuleatum, E.nodatum, C.gingivalis.

Methodology for Sample Collection for PCR Analysis

After evaluating the gingival status of the children, five teeth were selected (at least one fully erupted tooth from each quadrant) with the greatest probing depth, from which a sample was taken for PCR analysis.

The PCR samples were taken in the morning – at least ½ hour after tooth brushing and 1 hour after eating. Immediately before collection, the children rinsed their mouths with physiological saline solution, and supragingival deposits were removed using a dry sterile cotton swab. The field was isolated with a lignin roll, dried, and a sterile paper point was inserted into the gingival sulcus of each selected tooth. After waiting for approximately 20 seconds, the paper points were collected in a common standardized container (pooled sample), which was sent for analysis (

Figure 1).

Statistical Methods

The recorded data from the study were coded and entered into a computerized database, then processed using the specialized software IBM SPSS, version 19.0, and MS Excel 2019. The critical level of significance for testing the null hypothesis (H₀) was set at α = 0.05 (Z-criterion = 1.96) with a 95% confidence level.

The following methods were used to analyze the collected data:

Descriptive Analysis – Presented in tabular form, showing the frequency distribution of the studied characteristics based on specific indicators.

Method for Comparing Independent Groups – Independent T-test.

Pearson Chi-Square Test (χ²) – Used to test hypotheses for the presence of dependence between categorical variables.

Alternative Analysis – Used to compare two relative shares.

3. Results

1. Distribution by Gender and Age

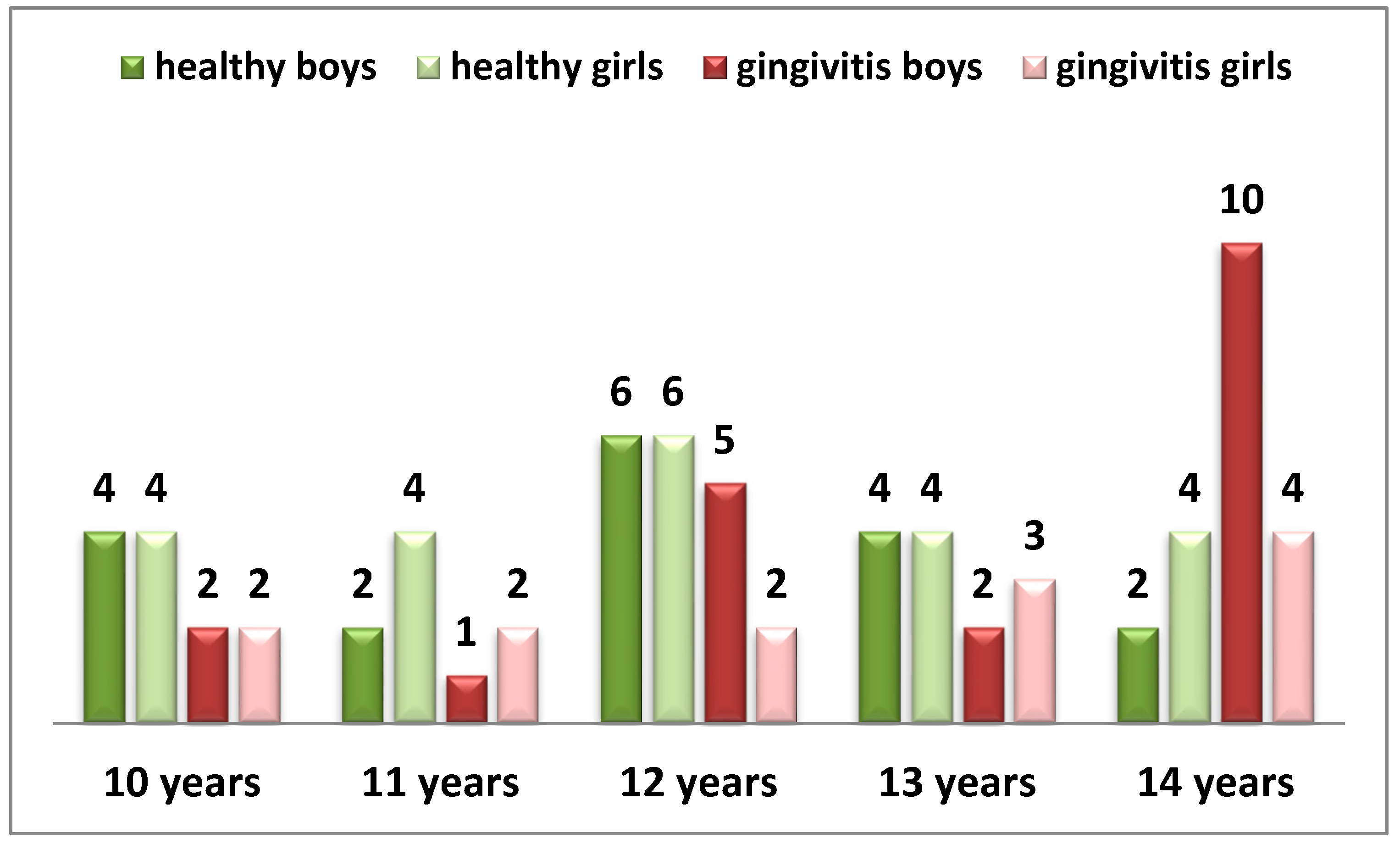

The following table presents the distribution of children participating in the study by gender and age (Diagram 1).

Diag. 1 Distribution of children by gender and age.

From the diagram, it can be seen that out of all examined children, 40 have preserved periodontal health, while 33 have gingival inflammation. A balanced gender distribution is observed in both groups (p > 0.05).

The children participating in the study are in a stage of late mixed or permanent dentition, with a stabilized periodontium.

2. Oral Hygiene Status (HI - Plaque-Free Surfaces)

A key etiological factor in the development of periodontal diseases is the subgingival biofilm, whose formation is directly linked to the development of supragingival dental biofilm. The lack of proper oral hygiene habits and the uncontrolled accumulation of plaque on tooth surfaces near the gingival sulcus represent major risk factors in the pathogenesis of gingival pathology.

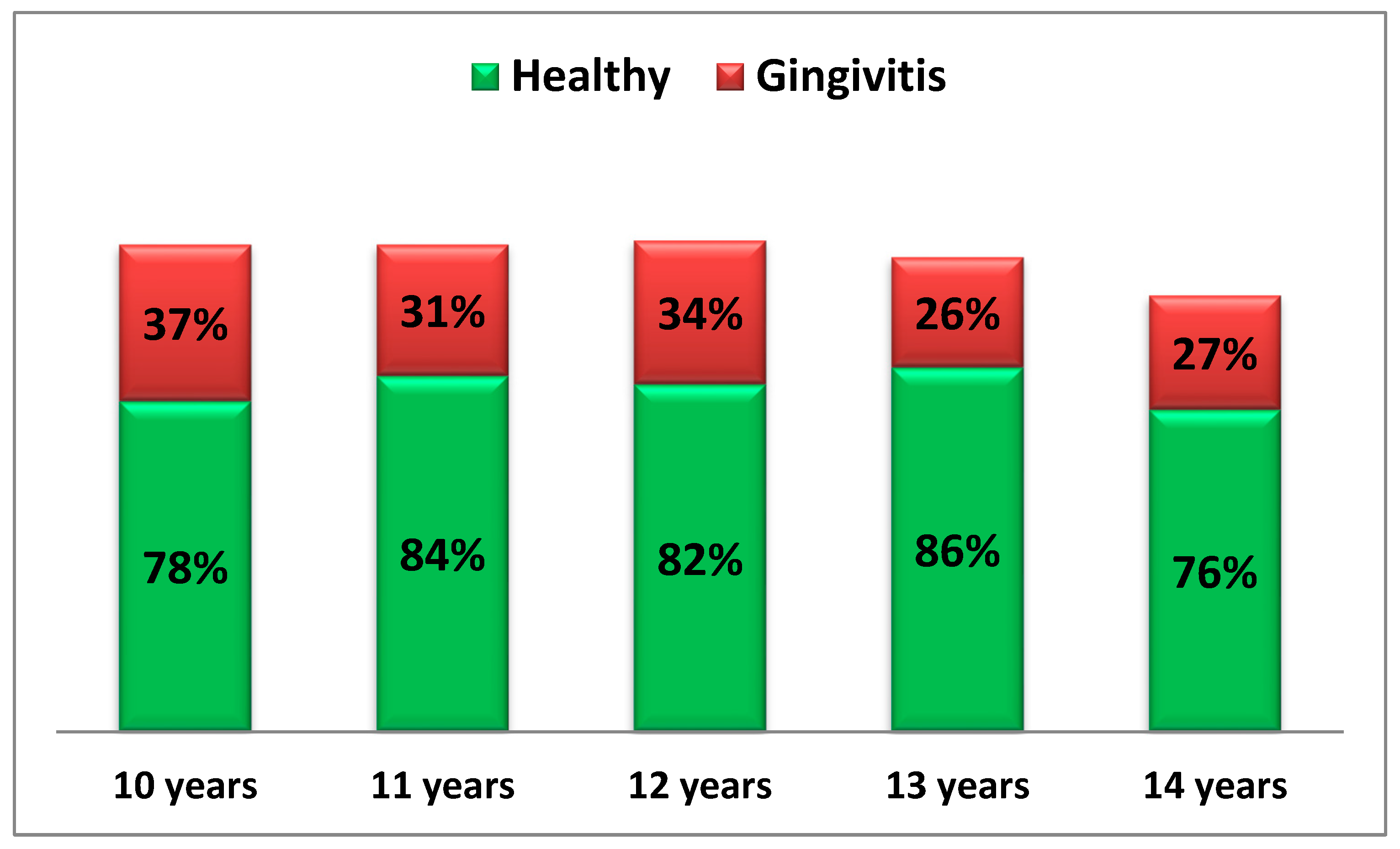

The following diagram presents the oral hygiene status (HI index) of the children from both study groups (Diagram 2).

Diag. 2 Oral Hygiene Status of Examined Children.

From the diagram, it is clearly visible that in healthy children, the percentage of plaque-free surfaces is around or above 80%, indicating that plaque accumulation affects less than ¼ of the examined surfaces.

In contrast, children with gingival inflammation show only 1/3 of surfaces free from plaque, meaning that over 70% of surfaces are affected by plaque accumulation.

Furthermore, it is observed that in the gingival inflammation group, the highest plaque accumulation is recorded among 13- and 14-year-old children.

3. Gingival Status – PBI (Prevalence)

According to the new classification of periodontal diseases, the presence of provoked gingival bleeding affecting more than 10% of gingival units categorizes a patient as having "gingivitis case."

The assessment of provoked gingival bleeding is considered an objective and simple method for differentiating isolated sites of inflammation from inflammatory periodontal changes as a distinct nosological entity [

12].

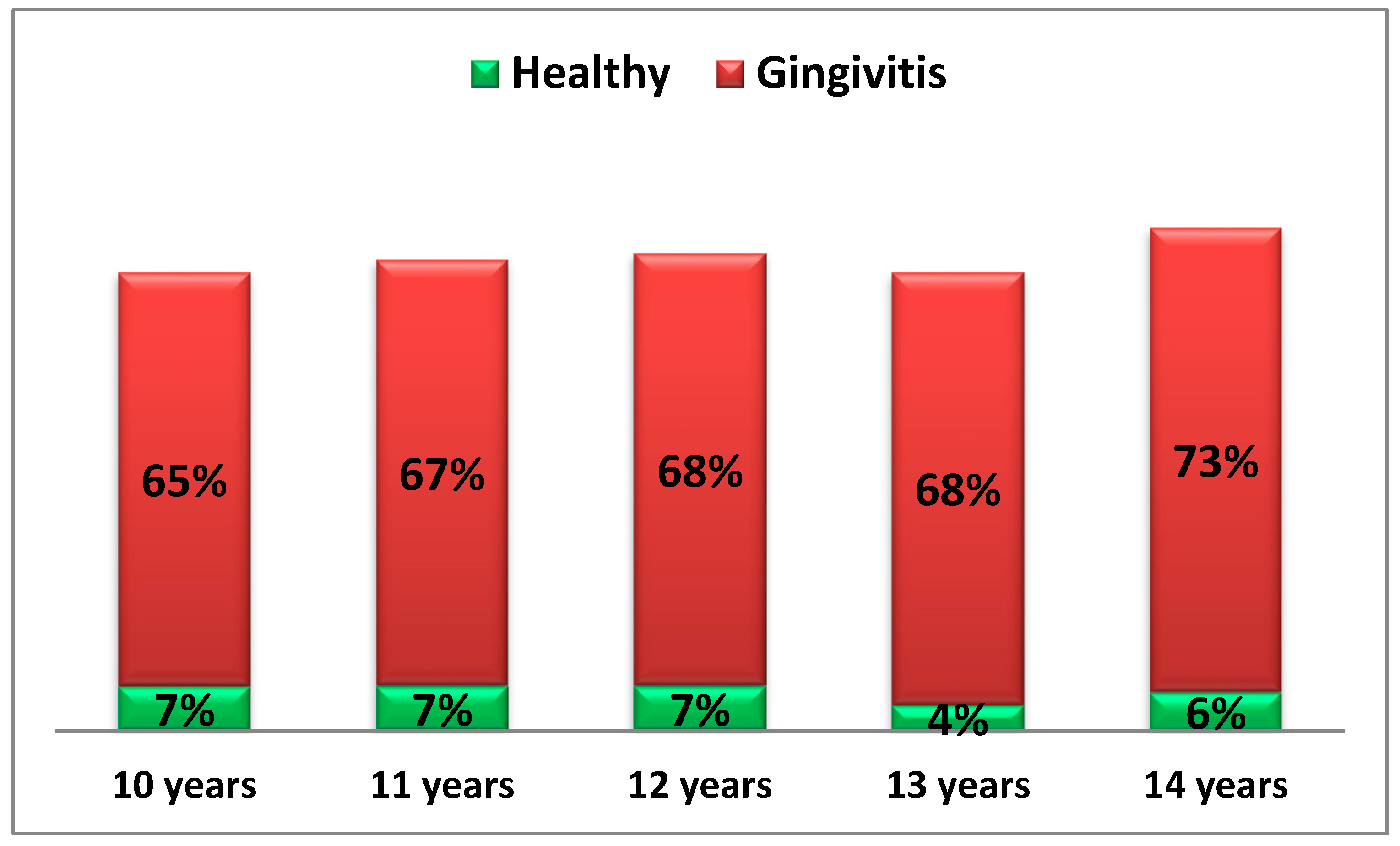

The following diagram presents the gingival status, recorded through the prevalence of provoked gingival bleeding among the examined children across different age groups (Diagram 3).

Diag. 3 Gingival Status of Children by Age.

From the diagram, it is evident that the prevalence of provoked gingival bleeding in the group of healthy children has an average value of approximately 6%.

In contrast, in the group of children with gingival inflammation, the average value is 69.8%, which, according to the new classification of periodontal diseases, characterizes generalized gingival inflammation.

Significant differences between healthy children and those with gingival inflammation are observed across all age groups (t₁,₂ = 2210.3, p < 0.05).

4. Total Microbial Load

The following table presents the quantity (total count per sample) of examined subgingival microorganisms in all children included in the study (

Table 1).

From the table, it can be seen that the average quantity of isolated microorganisms (MO) in healthy children is 3.8 × 10⁷ ± 5.9 × 10⁷, while a significantly higher quantity is isolated in children with gingival inflammation – 4.0 × 10⁸ ± 1.1 × 10⁹ (p < 0.05).

5. Relative Proportion of Isolated Microorganisms in Different Groups of Children

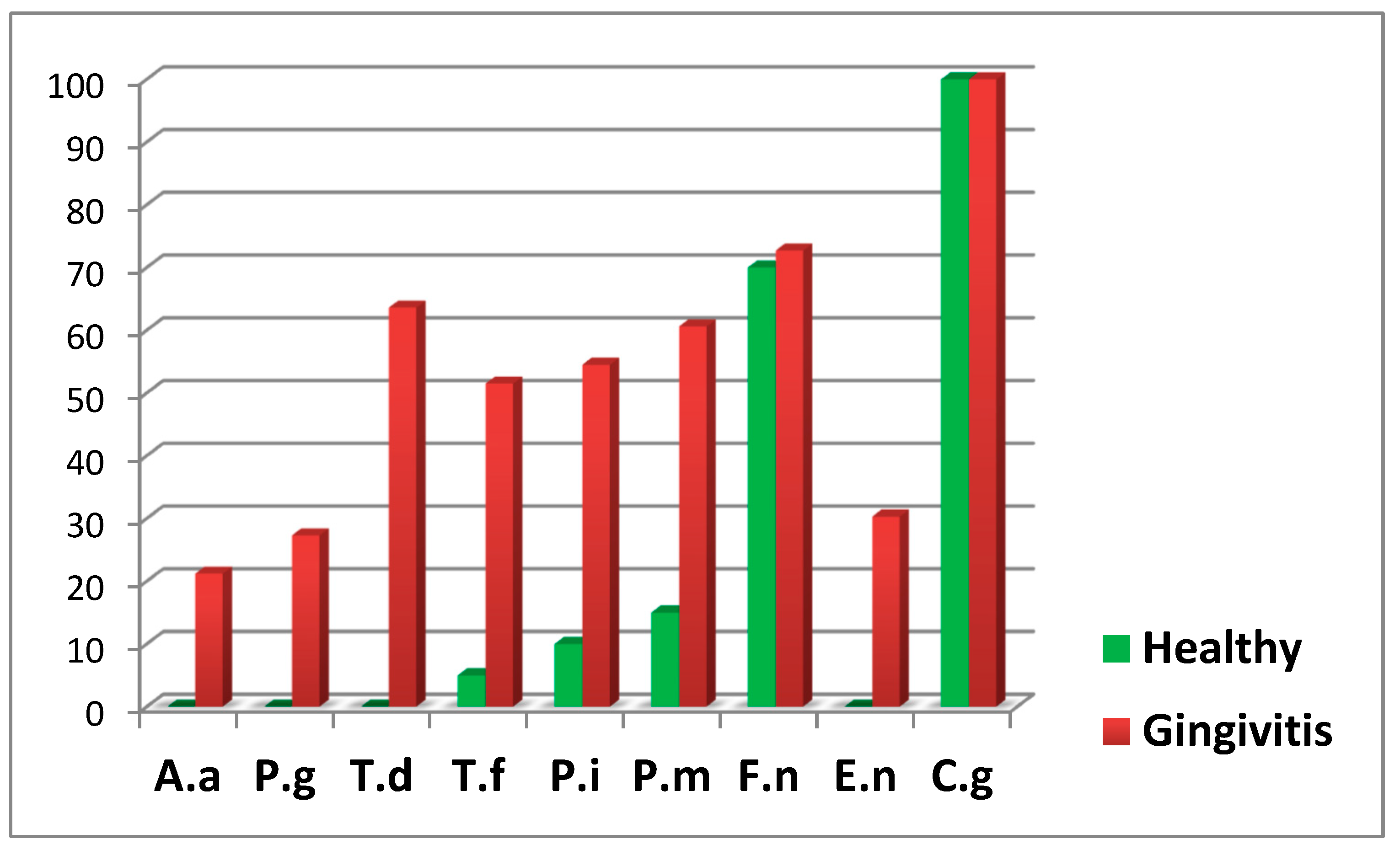

The following diagram presents the relative proportion of the examined periodontopathogens in children from both groups (Diagram 4).

Diag. 4 Relative Proportion of Isolated Microorganisms.

From the diagram, it is notable that four of the examined periodontopathogens (A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. denticola, and E. nodatum) were not isolated in healthy children.

In both groups, T. forsythia, a representative of the red complex according to Socransky, was isolated. However, in the group of children with gingival inflammation, the frequency of isolation was significantly higher (p < 0.05).

Among the microorganisms from the orange complex, F. nucleatum, which is the second most frequently isolated microorganism, was found in over 70% of the examined children and was relatively evenly distributed between children with gingival inflammation and healthy children.

However, P. intermedia and P. micros were found significantly more frequently in children with generalized gingival inflammation.

The representative of the green complex according to Socransky, C. gingivalis, was present in all examined children and was equally identified in both healthy cases and those with gingivitis.

6. Quantitative Characteristics of Isolated Periodontopathogens by Group

The following table presents the quantities of isolated periodontopathogens in both study groups (

Table 2).

From the table, it is evident that in healthy children, the isolated periodontopathogen T. forsythia from the red complex, which exhibits high virulence, is not only found in isolated cases but also in insignificantly low quantities.

Only F. nucleatum and C. gingivalis were isolated in higher quantities among healthy children.

In children with gingival inflammation, the highest quantities of isolated periodontopathogens were P. intermedia and C. gingivalis.

Regarding T. forsythia from the red complex and P. intermedia from the orange complex, significantly higher values were recorded in children with gingival inflammation (p < 0.05).

7. Isolated Microorganisms by Complexes in Different Groups of Children

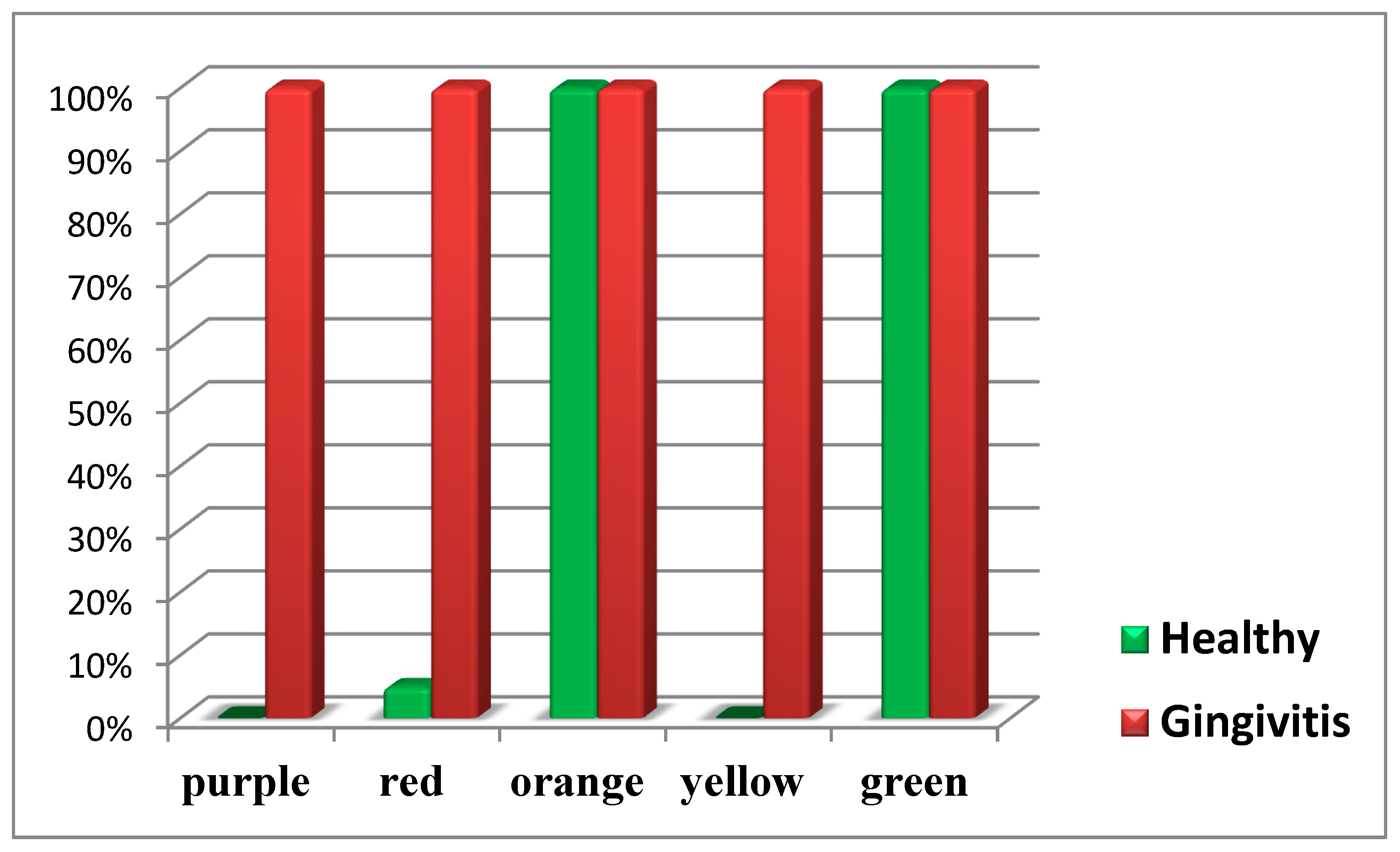

The following diagram presents the isolated microorganisms by complexes in healthy children and children with gingivitis (Diagram 5).

From the diagram, it is clearly visible that representatives of the orange and green complexes according to Socransky are present in both healthy children and those with generalized gingival inflammation.

In contrast, representatives of the purple and yellow complexes are found only in children with gingival inflammation.

The highly pathogenic representatives of the red complex according to Socransky are detected in all children with gingival inflammation and only in isolated cases among healthy children.

4. Discussion

The oral cavity is home to hundreds of unique microbial species, with specific periodontopathogens being isolated from different ecological niches [

13]. In the context of periodontal pathology, the composition of microbial species in the supra- and subgingival biofilm undergoes dramatic changes [

10,

14,

15].

The aim of this study was to isolate and compare key microorganisms from the subgingival microflora in healthy children and children with diagnosed gingival inflammation between the ages of 10 and 14.

As expected, children with gingival inflammation exhibited poor oral hygiene status and, consequently, a significantly higher microbial load compared to healthy subjects.

With this study, we established that four of the examined microorganisms were not isolated in healthy children – A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. denticola, and E. nodatum.

A study by Papaioannou et al. on 93 healthy children aged 3-12 years found that A. actinomycetemcomitans was not isolated in any of the examined samples, while P. gingivalis and T. denticola were isolated in subgingival samples from children aged 9-12 years. The authors suggest that as age increases, the subgingival microflora becomes more complex, though this does not necessarily lead to the manifestation of gingival inflammation [

16].

Relatively high levels of P. gingivalis isolation have been reported even in very young healthy children using genetic methods. One study reported that approximately 40% of children aged 6 to 36 months were carriers of this periodontopathogen [

17].

In another study, Umeda et al. examined Japanese children aged 8 years and reported an isolation rate of P. gingivalis at 8.9% and T. denticola at 48.2% [

18].

Researchers believe that the presence of certain oral pathogens in the oral cavity of healthy children may be a temporary phenomenon. Ooshima et al. concluded that pathogens such as P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, and T. denticola appear to be temporary colonizers in the oral cavity. The authors used the PCR method for isolating periodontopathogens [

19].

Similarly, Lamell et al. reached the same conclusion for A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, although the colonization of P. gingivalis appears to be more stable during the late teenage years [

17].

With this study, we also established that F. nucleatum, the second most frequently isolated microorganism, was detected in over 70% of the examined children and was relatively evenly distributed between children with gingival inflammation and healthy subjects.

Fusobacterium species play a crucial role in the formation of mature dental biofilm, as these bacteria coaggregate both with initial gram-positive bacteria from supragingival plaque and with subgingival colonizers, including most gram-negative and motile bacteria, which rely on cell-to-cell adhesion [

21,

22].

Piwat et al. conducted a study on 192 children aged 12-18 years, collecting a pooled microbiological sample from the gingival sulcus of four teeth per child. The samples were collected using a sterile curette and transferred to a transport medium, with the results analyzed using culture-based methods and PCR.

The authors found that healthy children had a lower relative proportion of F. nucleatum compared to children with gingivitis and those with stage 1 periodontitis [

20].

Contrary to this study, Wendland et al. reported that F. nucleatum was isolated twice as often in healthy children compared to those with diagnosed gingivitis [

23].

Our study found that C. gingivalis, a representative of the green complex according to Socransky, was present in all examined children and was equally identified in both healthy children and those with gingivitis.

Similar results have been reported by other research groups [

20,

23,

24]. These findings are likely related to the role of this microorganism in coaggregation processes, which are essential for the development of the subgingival biofilm.

Regarding the quantitative characteristics of isolated periodontopathogens, we found that in children with gingival inflammation, the highest quantities of isolated periodontopathogens were P. intermedia and C. gingivalis.

Similar to our findings, Albandar et al. reported that P. intermedia was significantly more frequently isolated in adolescents with active periodontal disease. Other researchers have also made similar observations, associating aggressive periodontitis with increased levels of P. intermedia and P. gingivalis [

25,

26].

Additionally, high levels of P. intermedia, similar to those found in our study, have also been detected in girls with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and diagnosed gingivitis [

23].

It is important to note that we also found high levels of T. denticola in the group of children with gingival inflammation.

Using state-of-the-art data analysis tools, Marotz et al. identified the relationship between Treponema and Corynebacterium as a new microbial indicator for periodontitis. The authors determined that this early indicator correlates with poor periodontal health and cardiometabolic markers in the early stages of disease pathogenesis, which should not be underestimated, especially in childhood and adolescence [

27].

With this study, we established that representatives of the orange and green complexes according to Socransky were present in both healthy children and those with generalized gingival inflammation. This finding suggests that these complexes participate in coaggregation processes and only under specific conditions may lead to the development of gingival pathology.

This study also established that the highly pathogenic representatives of the red complex according to Socransky were present in all children with gingival inflammation.

In healthy children, only T. forsythia was isolated, and only in rare cases and in minimal quantities. The red complex has been extensively studied due to its ability to negatively impact host physiology through virulence factors that directly damage periodontal structures [

27].

Papaioannou et al. reported a significant effect of age on the proportions of red complex species overall. The authors suggest that the increase in P. gingivalis proportions with age may be related to the increase in plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation. We observed a similar pattern, which suggests that as plaque accumulation increases, conditions become more favorable for the survival of red complex bacteria.

Nakagawa et al. [

28] reported a positive correlation between age progression to puberty and rising levels of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against P. gingivalis, which in turn correlates with the levels of this microorganism in the oral cavity.

Similar results were also reported by Morinushi et al. [

29]. This could further explain the increase in T. denticola levels, particularly in the subgingival dental biofilm.