1. Introduction

Underground mining requires specialised ventilation solutions to ensure human health, safety, and efficiency. The application of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) techniques in the design and assessment of ventilation systems has not found a wide range of applications in the mining industry’s academic and industrial sectors.

Underground ventilation systems are crucial for providing fresh air flow and removing contaminated air. CFD techniques offer powerful tools for optimizing these systems and evaluating their performance. McPherson [

3] emphasized that airflow, temperature, and humidity variations are fundamental factors in designing underground ventilation systems and demonstrated that these variables can be improved through modeling.

Daloğlu [

1] conducted a study on modelling air velocity and methane behaviour in underground mining operations using CFD. Daloğlu’s reported results examine the accumulation of methane gas and airflow in underground coal mines using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). The study aims to optimise the design of ventilation systems to control and evacuate methane gas safely.

Yi et al. [

7] have published research about CFD modelling applications in mine ventilation since 2000. The paper covers numerical analyses conducted in work surfaces, mine galleries, ventilation systems, and open-pit mines. The CFD modelling processes include geometry creation, mesh generation, equation solving, model validation, mesh independence studies, and solution convergence. The study highlights the advantages of CFD modelling in mine ventilation and provides recommendations for future research.

Ndenguma [

4] developed a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) model to examine airflow patterns in underground coal mines. This study analyses airflow velocities, pressure differences, and turbulence distributions, which are critical for mine ventilation design. The developed model is used to determine the effects of mine geometry on airflow and compare different ventilation scenarios. The results provide significant findings for identifying critical airflow regions, optimising ventilation systems, and enhancing mine safety.

Prasad and Lal’s study [

5] utilised CFD to analyse heat stress experienced by workers in underground coal mines. By modelling airflow and temperature distribution within the mine, the study aims to detect areas susceptible to heat stress due to inadequate ventilation. Problematic regions, such as dead-end tunnels with poor ventilation, are identified, and ventilation adjustments are proposed to prevent sudden heating and ensure worker safety. The Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) index is used to evaluate heat stress and generate thermal load maps within the mine. WBGT is a widely used index for assessing the thermal effects of hot environments on the human body, particularly in occupational health and safety. The study demonstrates that CFD analyses are a powerful tool for protecting worker health and designing effective ventilation systems in underground mines.

Sasmito et. al. [

6] examine various methods to enhance ventilation systems in underground coal mines using CFD. The study models gas control in a “Room and Pillar” structured coal mine based on turbulence flows, mass, energy, and momentum conservation principles. It specifically tests additional ventilation systems and different design scenarios to efficiently remove methane gas in rapidly developing mining intersection areas. The advantages and limitations of these designs are assessed in terms of airflow quality, quantity, and pressure losses. Recommendations are made to enhance worker safety and optimise ventilation. This study demonstrates that CFD analyses are crucial for designing and improving underground mine ventilation systems.

Aksoy et al. [

10] published a study following the Soma mine disaster, revealing that gases such as CO and CO2, HCN, Cl2, and H2S, which are lethal at low concentrations, were released during a conveyor belt fire. This complex situation underscores the need for thorough planning and preparation. Another significant finding was that underground mine thermodynamic conditions could change completely quickly depending on the fire’s magnitude. Additionally, due to conveyor belts made from petroleum derivatives, hydrocarbon products were detected among the combustion gases, which were sometimes recorded as CH4 by gas sensors. Furthermore, the flammability of these combustion gases made it extremely difficult to extinguish conveyor fires, as the presence of hydrocarbon combustion products allowed the fire to continue burning. Another critical conclusion from this study was that air circulation within the mine could change unexpectedly due to a fire. Thus, CFD analysis was recommended when planning emergency response strategies in underground mines.

Aksoy [

8] conducted insightful CFD analyses on a model derived from experimental data to thoroughly explore the impacts of the evolving fire during the 2014 Soma mine disaster.

Aksoy [

9] conducted a comprehensive study, conducting advanced CFD analyses at İMBAT Mining Co.’s Eynez Underground Operation, meticulously investigating fire scenarios involving conveyor belts. This research aimed to critically evaluate the effectiveness of underground ventilation systems in emergencies, highlighting the need for robust safety measures in mining operations.

This study provides a technical analysis and evaluation of underground ventilation operations in a metal mine. Effective ventilation is crucial for ensuring occupational health and safety as well as enhancing operational efficiency in underground mining. The study assesses the performance of ventilation systems under three distinct fire scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

This research endeavors to rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of ventilation systems in the critical context of fire safety. It strategically focuses on key aspects such as the safe evacuation of hazardous gases, comprehensive airflow distribution analysis, and thorough risk assessments post-fire incident. The outcomes will not only assess the adequacy of existing ventilation infrastructure but also pinpoint specific areas that necessitate improvement. This report aims to deliver valuable insights into current conditions and to inform strategic planning for future mining operations. Backed by in-depth technical details, this study plays a vital role in advancing the development of safe and sustainable ventilation strategies, ensuring the well-being of personnel and the integrity of mining operations. The report is prepared to understand the existing conditions and guide future planning for mining operations. Supported by technical details, this study contributes to the development of safe and sustainable ventilation strategies in mining operations.

2.1. Underground Mine and Geometry

In the intriguing world of underground mine ventilation, two essential types of fans are crucial for ensuring the safety and comfort of miners. Main fans, which are powerful machines connected in parallel, each provide an impressive 180 kW of energy. These robust fans work tirelessly to remove contaminated air, creating a healthier and more breathable environment deep underground. breathable environment deep underground.

Auxiliary fans, each with a powerful 55 kW rating, play a vital role in enhancing airflow within the galleries by channeling air through strategically placed ventilation tubes. This thoughtful design guarantees that even the most remote areas benefit from optimal air circulation, ensuring a safe and comfortable environment for all.

Firstly, it is dedicated to calibrating fan performance through advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) analyses combined with actual performance data from mining operations obtained from research conducted at the underground metal mine under study, resulting in significantly improved efficiency. This thoughtful approach emphasizes that this thoughtful approach is essential to maintaining excellent air quality in underground environments. This is an unwavering commitment to maintaining excellent air quality in underground environments.

The underground geometry has been thoughtfully designed, inspired by detailed blueprints from the mining operation. This impressive layout includes comprehensive floor plans and well-placed galleries, all harmoniously integrated with ventilation ducts and crucial air gates. These elements work together to create an efficient and functional mining environment, enhancing accessibility and airflow throughout the underground space.

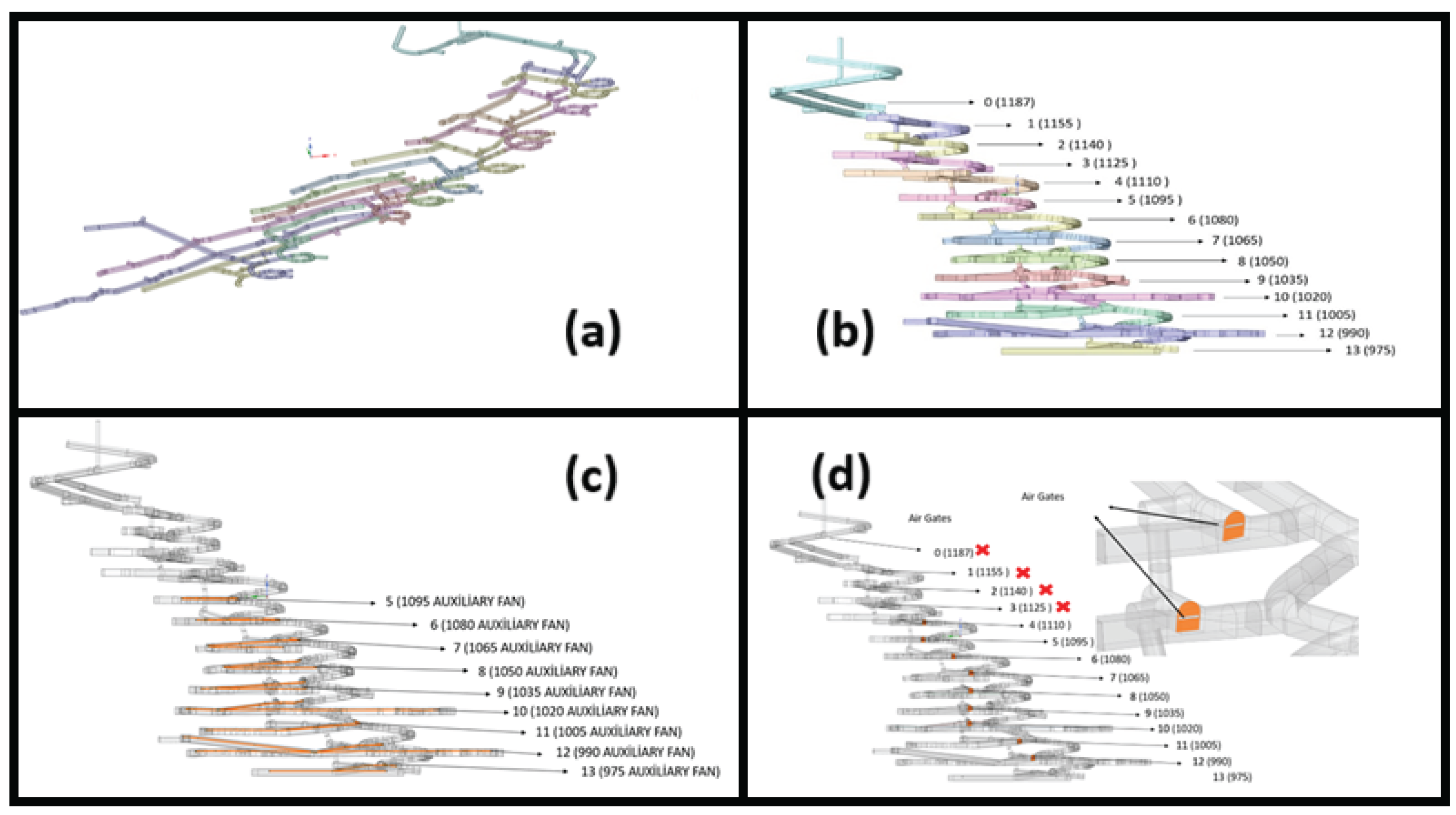

Figure 1 shows the 3D model of the underground mine.

Figure 1b shows the intermediate floors where production takes place in the underground mine and includes infrastructure for ventilation (gallery, fan, air gate),

Figure 1c shows the Placement of Auxiliary Fans and Fan Ducts on Floor Geometries, and

Figure 1d shows the Placement of Air Gates and Open Air Gates on Mine Geometry.

2.2. Computational Fluid Dynamics Analyses

In-depth analyses were conducted using advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) techniques as a crucial component of the metal mine ventilation study. These analyses were specifically designed to rigorously evaluate the conditions within the mine, assess the effectiveness of the existing ventilation infrastructure, and analyze the system’s performance in the event of fire scenarios. This comprehensive approach ensures that we not only understand current ventilation capabilities but also enhance safety and operational efficiency in the mine.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a vital engineering discipline that delves into the intricate movement of fluids and the physical processes that accompany them through advanced numerical methods. At the core of this field are the Navier-Stokes equations, which intricately define crucial parameters such as velocity, pressure, and temperature over time and space. By employing sophisticated numerical techniques—including finite differences, finite volumes, and finite elements—CFD effectively solves these complex equation. CFD stands as an indispensable tool for tackling a wide array of challenges in engineering, such as heat transfer, turbulence, chemical reactions, and multiphase flows. With the right meshing strategies and boundary conditions, CFD simulations can deliver highly detailed insights and predictions, often at a fraction of the cost of traditional experimental testing

Conservation of Momentum (Navier-Stokes Equations):

CFD solves equations by applying appropriate boundary and initial conditions, allowing for the prediction and optimization of fluid systems’ behavior. Today, it finds extensive applications across the aerospace, automotive, mining, and energy industries.

2.2.1. Fire Scenarios and Results in Underground Metal Mines

The analysis of temperature and smoke propagation was meticulously conducted across three distinct regions following a fire incident. Extensive research in the literature has accurately quantified the energy input and smoke production associated with various fire scenarios. Notably, it was determined that a 25 MW fire would achieve its peak temperature by the 10th minute and initiate the extinguishing process by the 20th minute [

2]. This important insight underscores the critical dynamics of fire behaviour, enhancing our understanding of fire management and safety protocols.

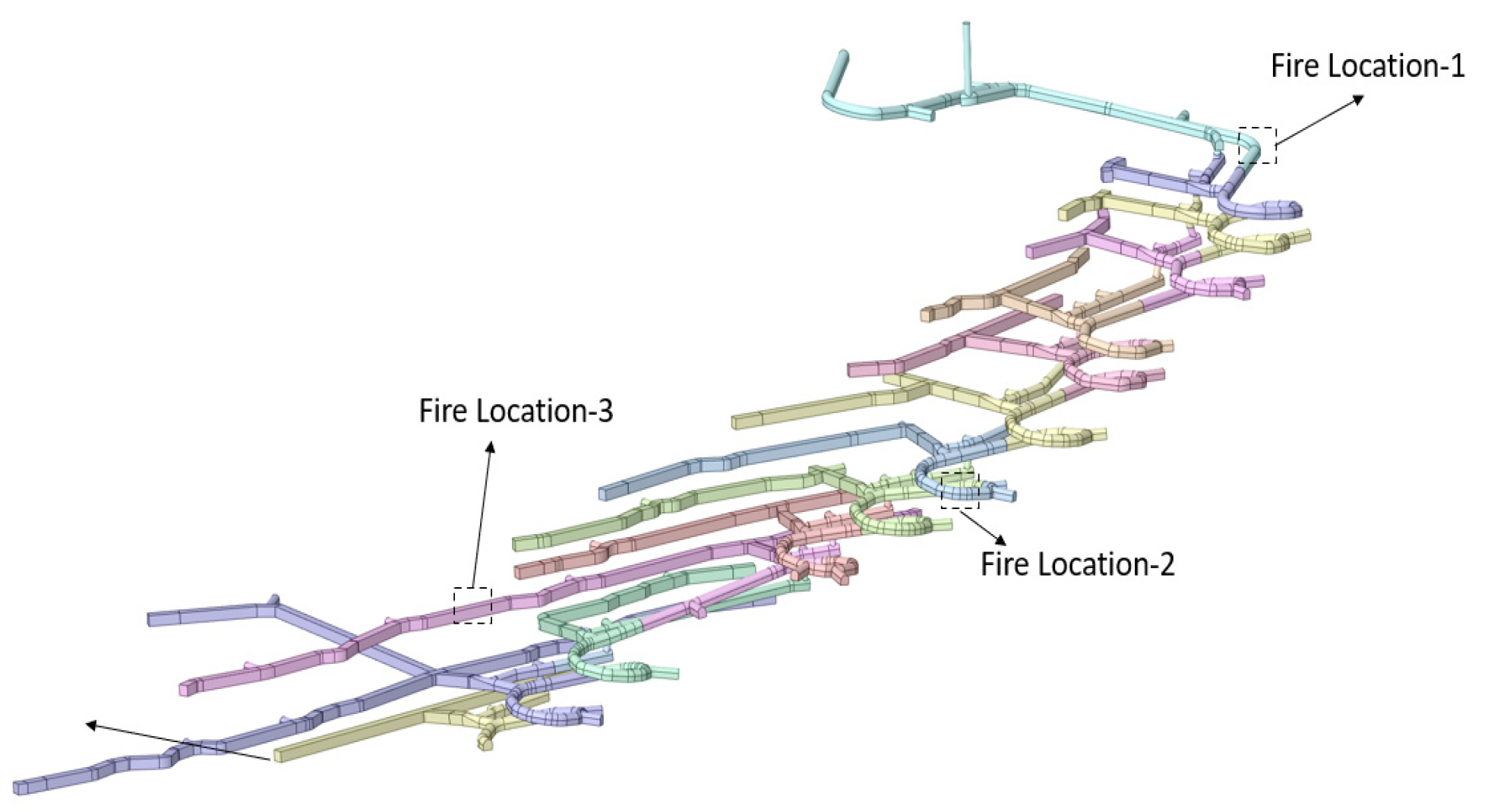

Figure 2 illustrates the strategic locations where fire scenarios were meticulously analysed within the underground mine. The first fire location was strategically chosen near the mine entrance, the second was positioned in the central sections, and the third was situated deep within the mine. Importantly, all three fire scenarios were deliberately planned along the air intake route, highlighting the critical need for proactive fire safety measures in these vulnerable areas.

2.2.1.1. Examination of the Fire Scenario at the Entrance of the Mine and the Air: 1st Fire Scenario

In the first fire scenario, the mine entrance was strategically selected as the focal point of investigation. The key objective is to thoroughly understand how a fire affects the mine’s thermodynamics at both the mine and the air entrance. Furthermore, it was aimed to track the trajectory of toxic gases released during the incident, analysing their concentration levels over time. This comprehensive approach will provide critical insights into the safety implications of fire hazards within the mine.

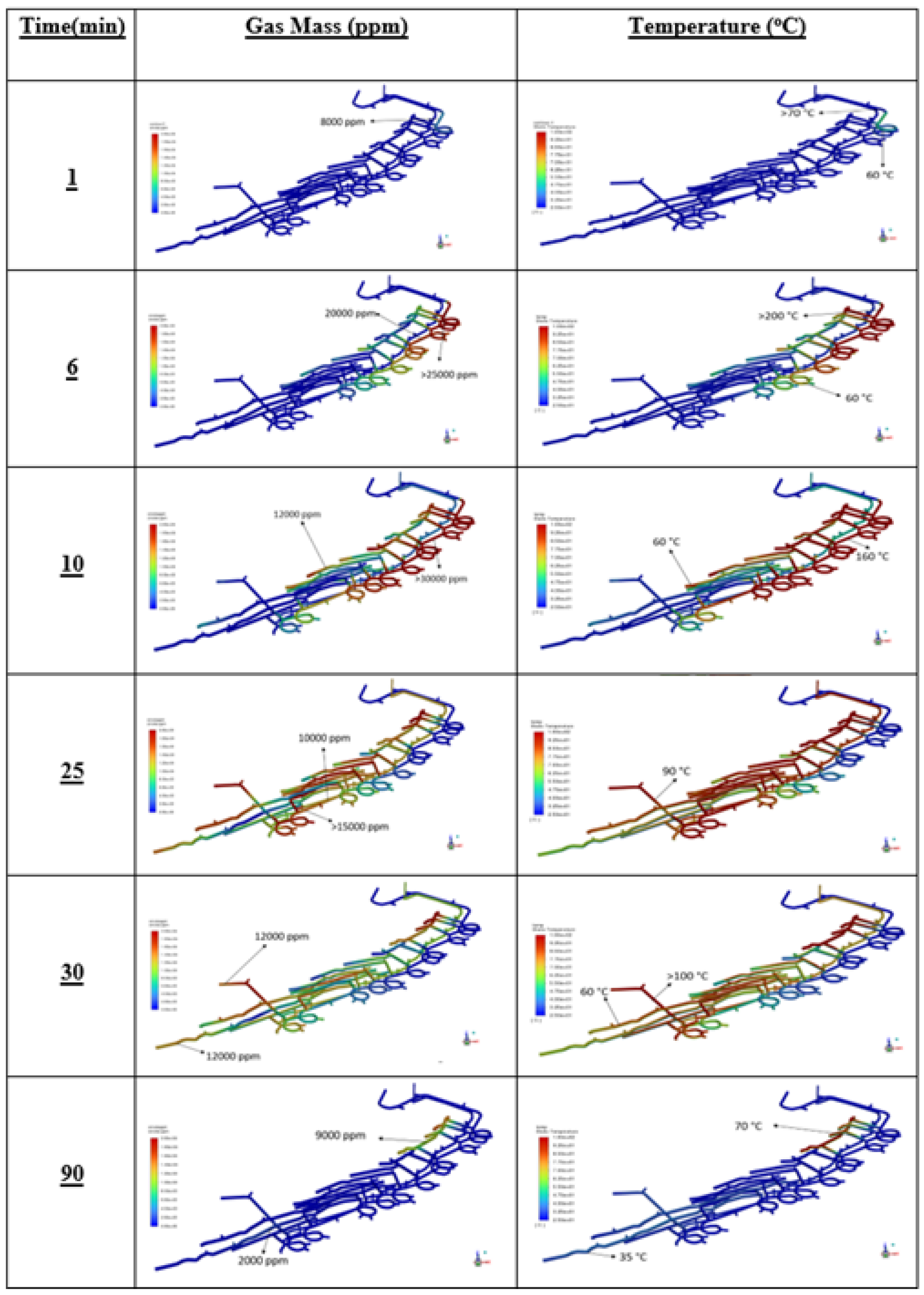

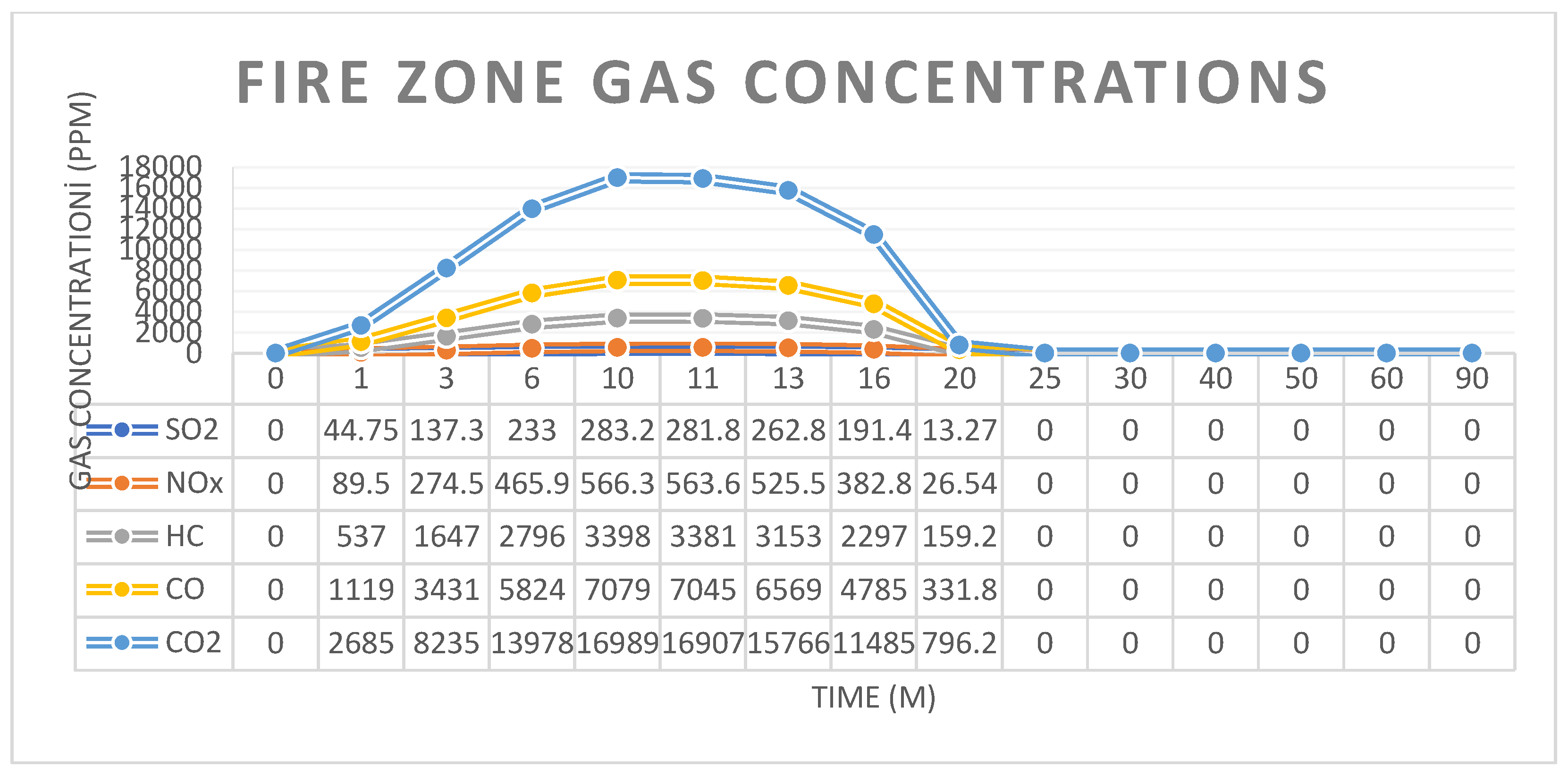

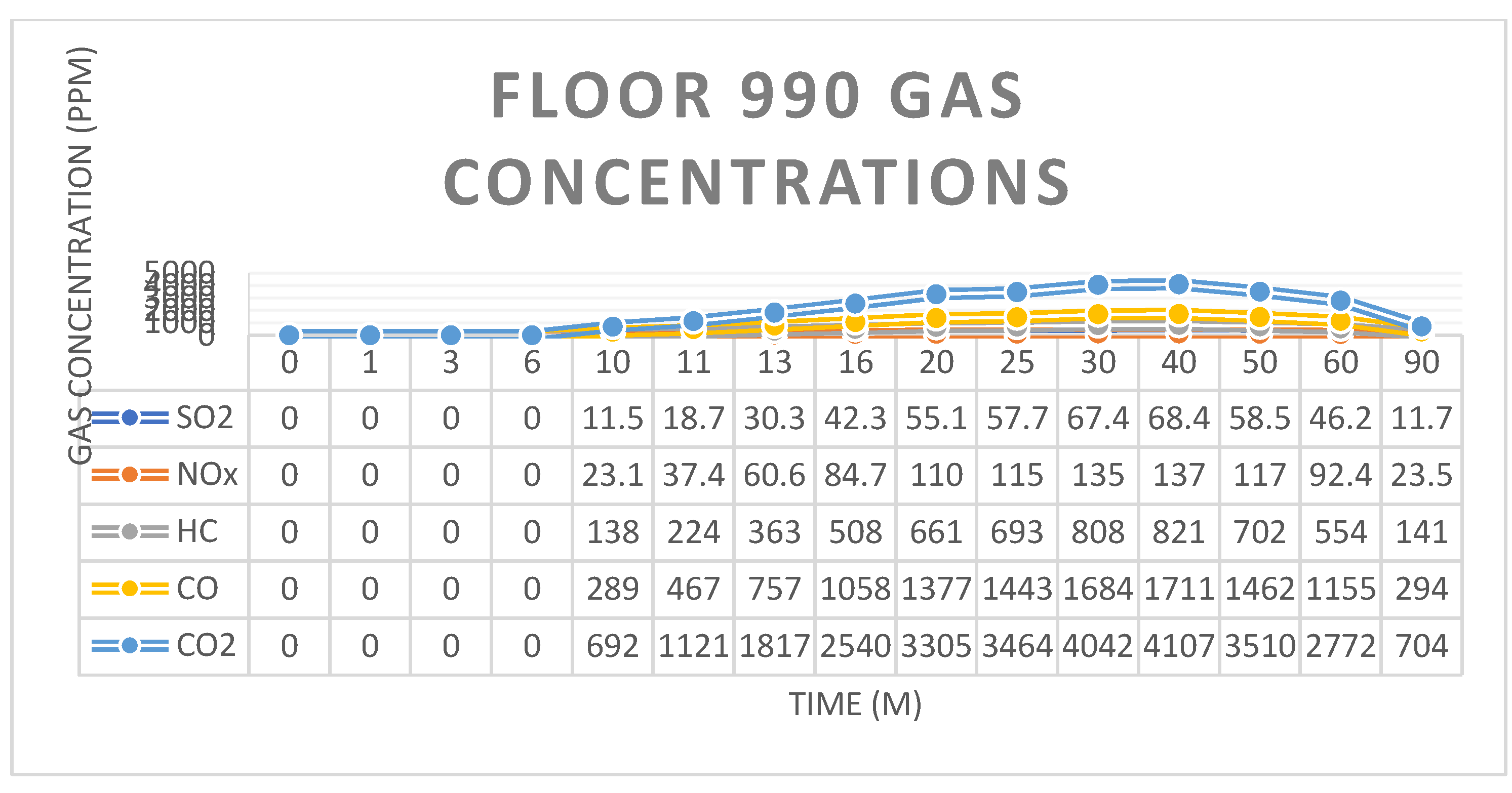

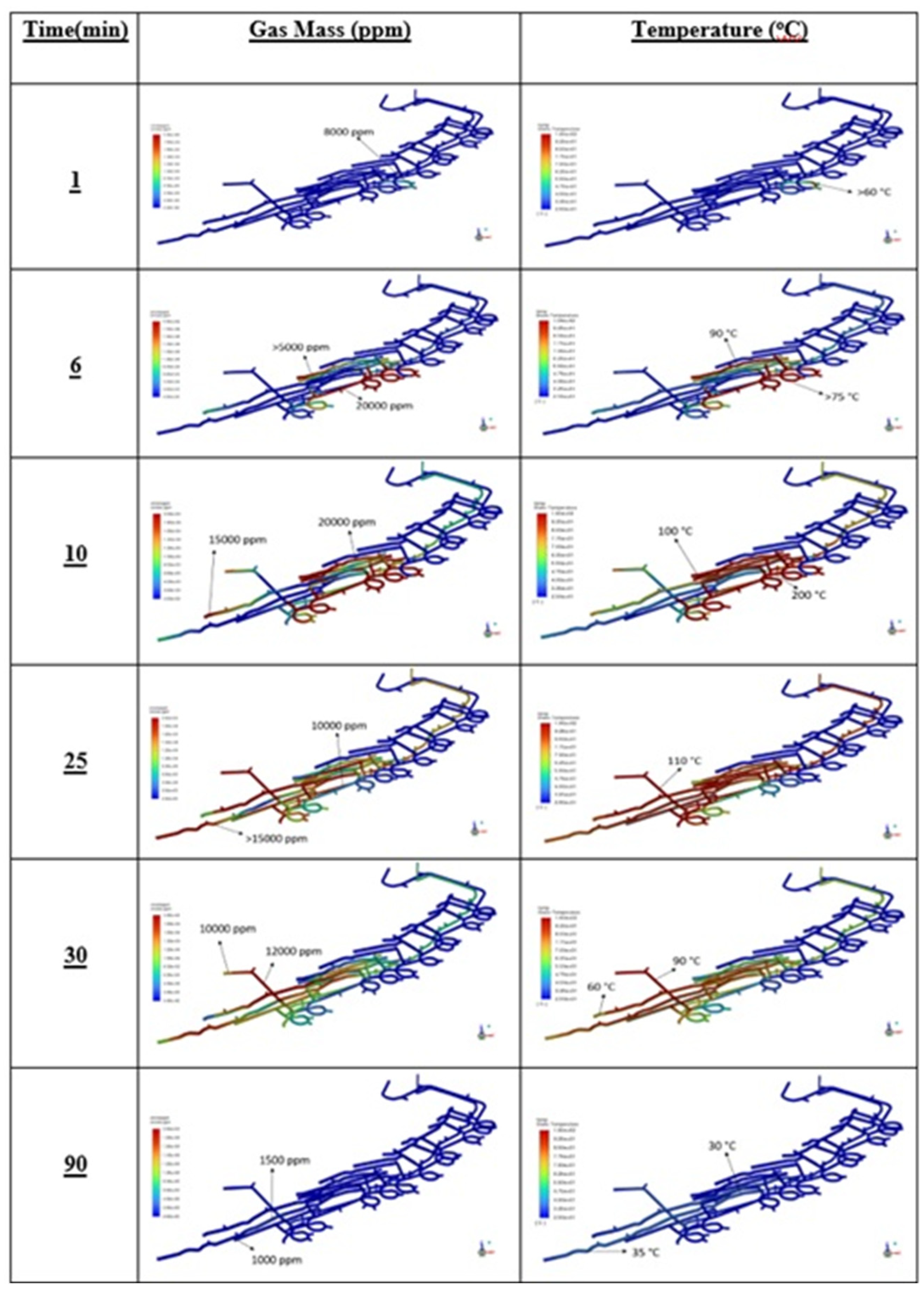

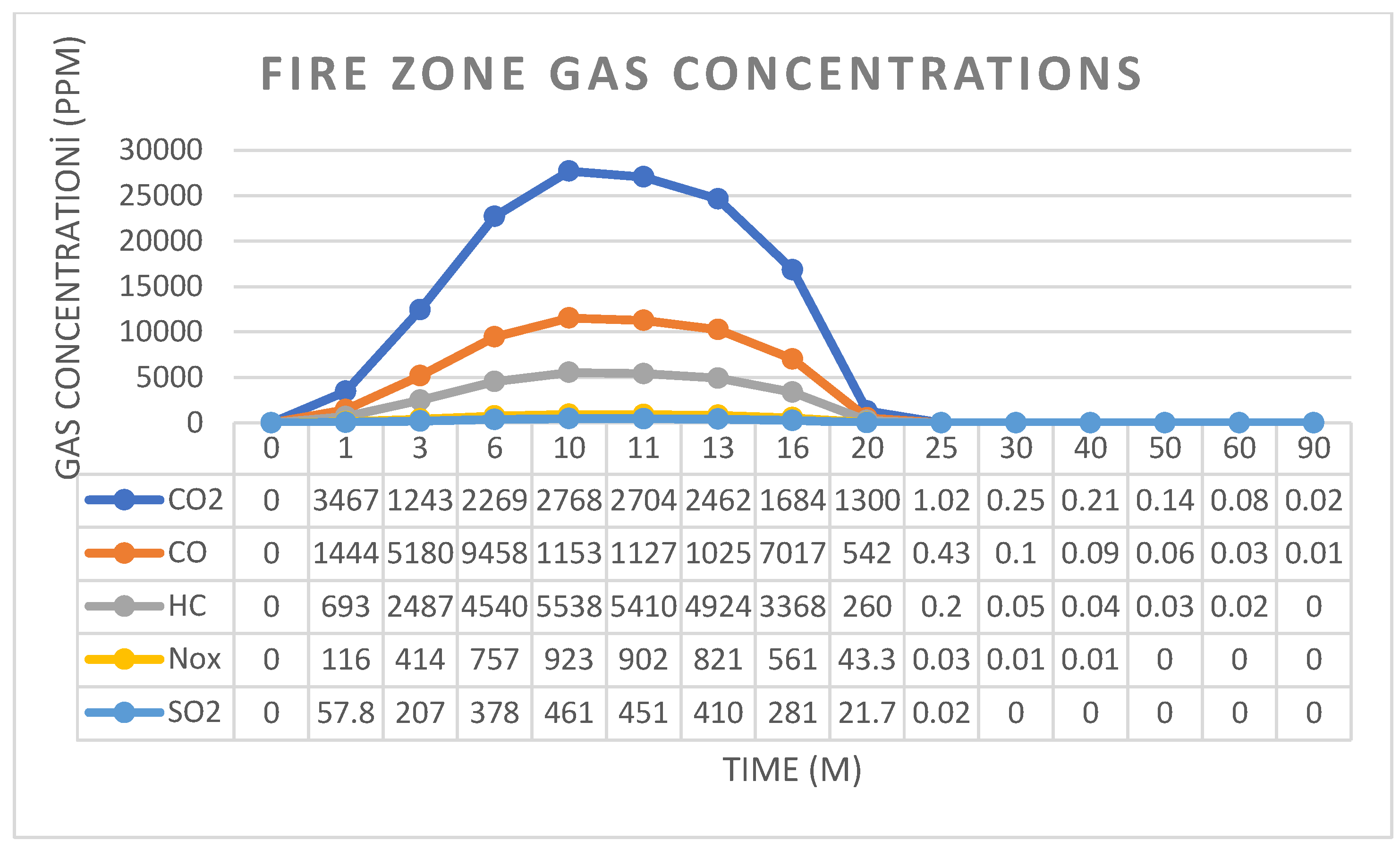

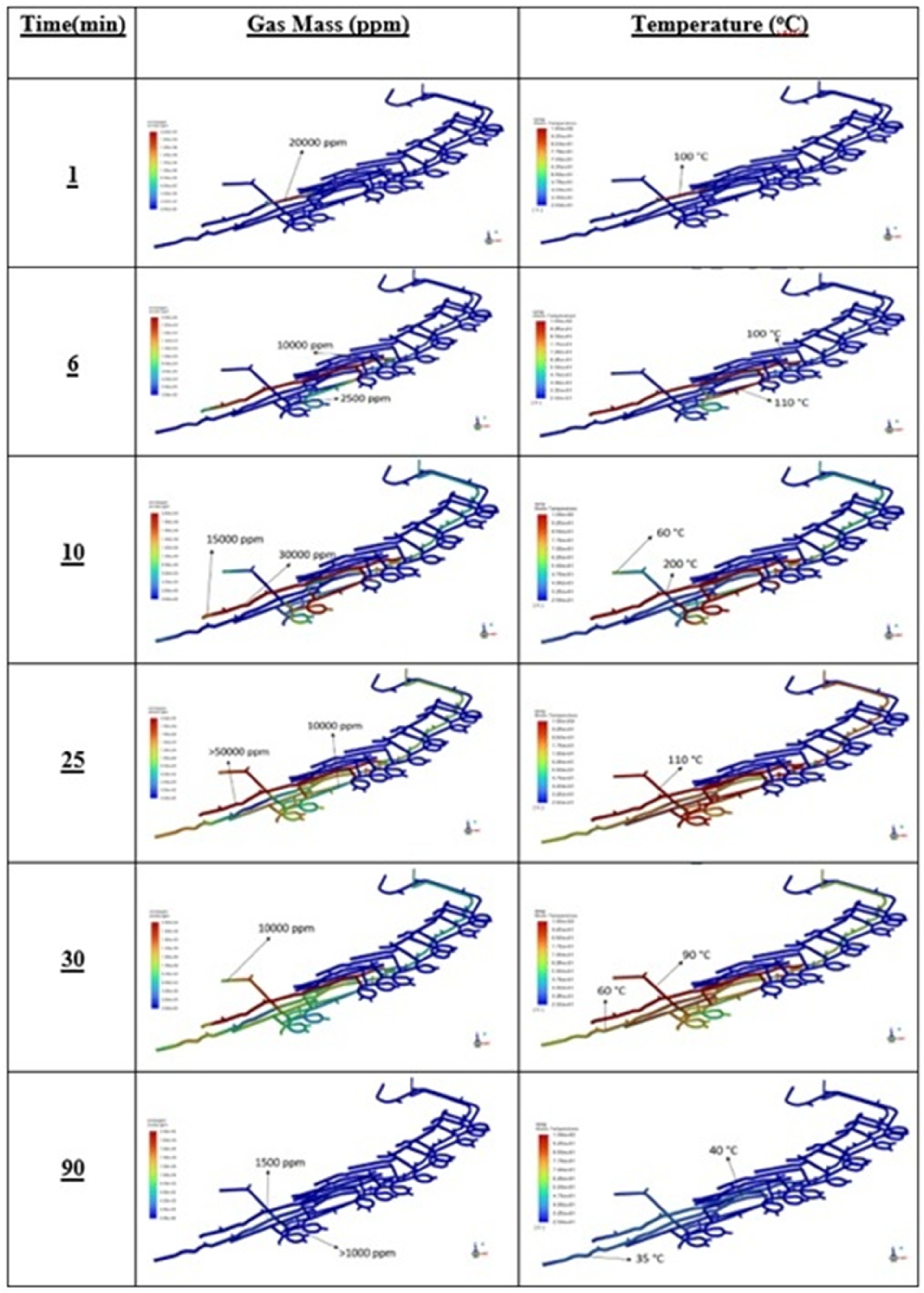

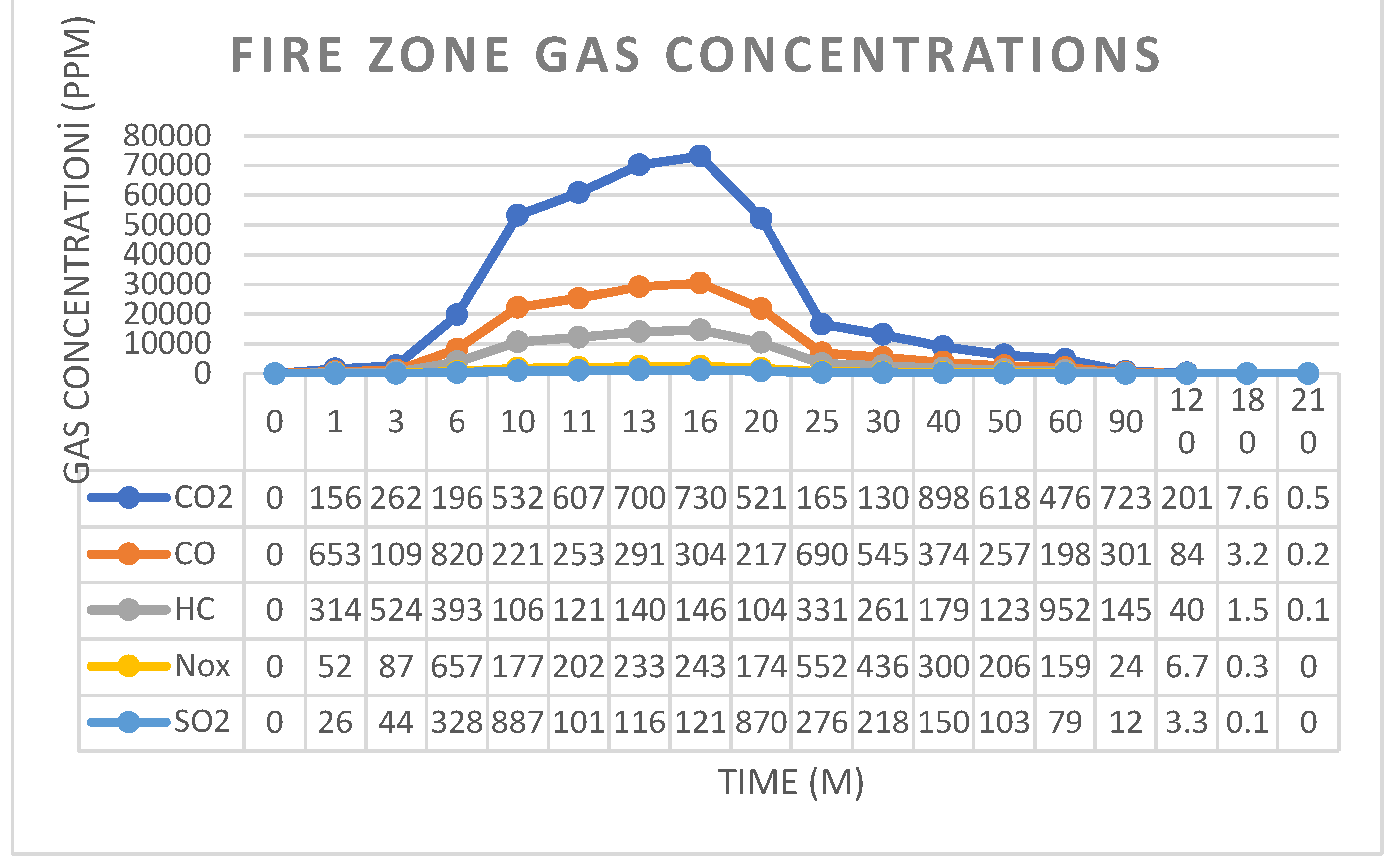

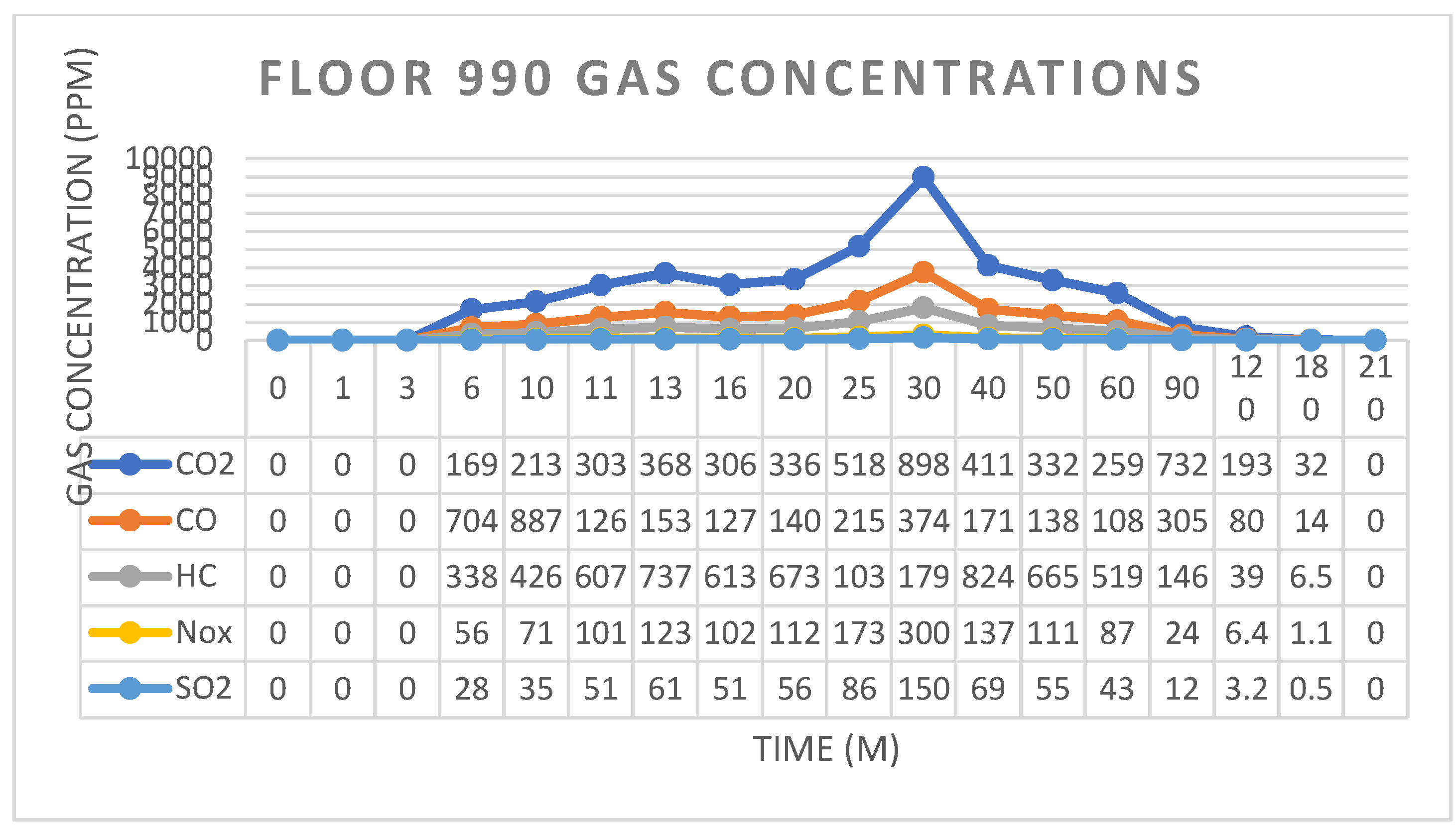

Figure 3 shows the time-dependent changes and paths followed by changes in heat and gas concentration resulting from fire. Time-dependent toxic gas concentrations in the fire zone and the 990 production floor are given in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, respectively.

In just the first minute, it was observed a rapid surge in smoke concentrations of CO₂ and CO, shooting up to an astonishing 8000 ppm. The heat in the fire zone escalates significantly, has reached over 70°C. It’s remarkable to see how hot air is visibly flowing through the main gallery, with temperatures soaring to about 60°C. By the sixth minute, the situation intensifies, with smoke levels skyrocketing to 25,000 ppm, and temperatures soaring past 200°C. Additionally, the hot air continues its journey through the main gallery, beautifully mixing with fresh air and maintaining a stable temperature of around 60°C—showcasing the incredible dynamics at underground mine. As we reach the tenth minute, things get even more interesting. Smoke concentrations in the main gallery was rose above 30,000 ppm, while temperatures stabilize around 160°C. The movement of hot air was persisted, and thanks to auxiliary fans, the warm air and smoke have begun to circulate into the lower galleries at about 60°C. By the twenty-fifth minute, there was a refreshing development as fresh air starts increasing in the main gallery, effectively reducing the concentration of toxic gases to around 10,000 ppm. By the thirty-minute, fresh air flows down to the lower levels. Even in the less active galleries, our auxiliary fans spring into action, supplying much-needed fresh air, and the toxicity begins to drop to 12,000 ppm. This positive air movement has also helped to lower temperatures in these areas. Fast forward to the ninety-minute mark, where fresh air dominates the mine. Though some smoke lingers in lower galleries where air movement was slower, and in upper galleries without fans. Here, smoke concentrations rest at 2000 ppm in the lowest parts and reach 9000 ppm upstairs, with temperatures relatively comfortable at around 35°C below and 70°C above.

In the fire zone, toxic gases was surge until the 10th minute, peaking dramatically before plummeting to nearly 0 ppm by the 20th minute. Meanwhile, on the 990th floor, the presence of auxiliary fans facilitates the transport of smoke, leaded to maximum gas concentrations at 40 minutes, followed by a gradual decline until the 90th minute. The rapid clearing of the fire zone is aided by robust airflow in the main ramp, contrasting sharply with the prolonged clearance on the 990th floor due to its weaker airflow. This stark difference underscores the critical importance of adequate ventilation in emergency scenarios.

2.2.1.2. Investigation of the Fire in the Middle Sections of the Mine: Fire Scenario 2

In the second fire scenario, a location was strategically selected in the central sections of the mine to maximise monitoring efforts. The primary objective was to meticulously track airflow and gas pathways over time, particularly as thermodynamic conditions evolve in response to the fire.

Figure 6 compellingly illustrates the dynamic patterns and trajectories of fire-generated heat and gas concentrations as time elapses. This underscores the urgent need for continuous observation and comprehensive analysis in these critical situations. Adopting this proactive approach is vital for ensuring safety and effectively managing the inherent dangers of such hazardous conditions.

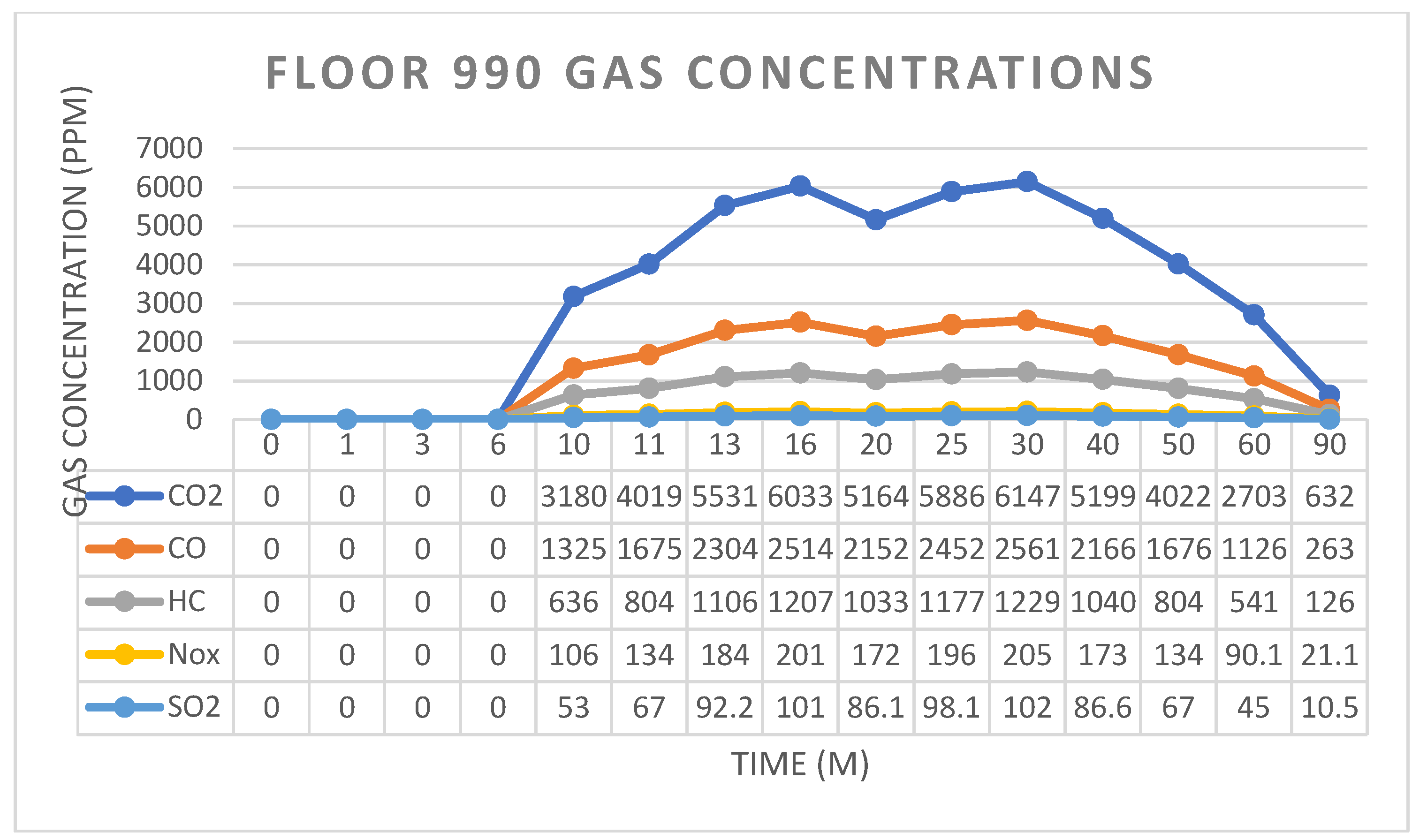

Figure 6 illustrates the changes over time and the pathways taken by heat and gas concentration due to fire. The concentrations of toxic gases in the fire zone and on the 990 production floor are presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, respectively. At 1 minute, it is observed that the concentration of toxic gases resulting from combustion in the fire zone rapidly rises to 8000 ppm. The temperatures in the fire zone exceed 60°C. The movement of hot air through the main gallery can be observed. At 6 minutes, smoke continues to spread through the main ramp, reaching levels of 20,000 ppm. Due to auxiliary fans, the smoke that reaches the inner galleries exceeds 5000 ppm. The temperature on the main ramp rises above 75°C, while the temperatures transmitted to the inner galleries via the auxiliary fans reach 90°C. At 10 minutes, the smoke and associated temperature increase reach the lowest galleries. Due to the auxiliary fans, the smoke concentration in the inner galleries reaches 20,000 ppm. As the density of the heated air decreases in these galleries, gas accumulations are observed near the gallery ceilings. Temperatures rise to 200°C in the main ramp and 100°C in the inner galleries. Smoke starts passing through the ventilation shafts and reaching the main fans. At 25 minutes, fresh air begins to reach the lower levels through the main ramp. As a result, the smoke concentration in the main ramp decreases to 10,000 ppm. Due to the fresh air supplied by the auxiliary fans, the smoke concentration at the ends of the inner galleries also decreases. Temperature reductions are observed at the ends of the inner galleries due to the fresh air provided by the auxiliary fans. However, the overall temperature in the galleries remains around 110°C. After 30 minutes, the smoke concentration in the inner galleries drops to 12,000 ppm. Thanks to the auxiliary fans, the cleaning process continues, starting from the ends of the galleries. As fresh air reaches the lower levels, the air temperature at the ends of the inner galleries drops to 60°C. At 90 minutes, the fire weakens, and fresh air is distributed throughout the mine, reducing the smoke concentration to 1000 ppm. Ventilation reduces temperatures in the galleries to approximately 30°C. By the end of 90 minutes, the mine is free from the effects of the fire. Time-dependent gas concentrations have been meticulously monitored in both the fire zone and the cross-cut gallery on the 990th floor. In the fire zone, it was seen that gas levels surge dramatically, peaking at the 10-minute mark, before plummeting to nearly 0 ppm by the 20-minute mark. Meanwhile, on the 990th floor, the auxiliary fans effectively transport smoke, resulting in gas concentrations reaching their maximum at 30 minutes, followed by a significant decline to almost zero by the 90-minute mark. This data underscores the critical dynamics of gas behaviour in emergency scenarios, highlighting the importance of timely intervention and ventilation strategies.

2.2.1.3. Investigation of the Fire in the Production Area in the Deep Zone of the Mine: 3. Fire Scenario

The selection of the third fire scenario location is crucial, as it represents one of the final points where clean air enters after passing through the mine entrance. The primary objective is to evaluate whether the contaminated air will reverse course and flow back toward the source of the clean air due to the changes in the thermodynamic conditions. If the polluted air indeed travels in the direction from which it originated, it will create serious safety hazards within the mine. Therefore, understanding this air movement is vital for ensuring the safety and well-being of all personnel.

Figure 9 shows how heat and gas concentrations change over time due to fire. The levels of toxic gases in the fire zone are presented in

Figure 10, while

Figure 11 displays the concentrations found on the 990 production floor.

At 1 minute, it was observed that the fire spread rapidly after ignition. The smoke concentration quickly rose to 20,000 ppm. Similarly, the temperature due to the fire rapidly reached 100°C. At 6 minutes, the smoke spreads downward through the main ramp into the lower galleries. In the lower levels of the main ramp, it was observed the smoke concentration reaches 2,500 ppm. In the opposite gallery of the fire zone, accumulations of 10,000 ppm are observed. The temperature in the lower galleries rises quickly to 110°C, while temperatures of 100°C are recorded in the opposite gallery of the fire zone. At 10 minutes, the impact of the fire reaches 15,000 ppm inside the lower galleries due to the auxiliary fans. At the same time, it is observed that gases leaking from the fire zone into the main ramp tend to rise to the upper gallery through the main ramp. The smoke concentration in the fire zone increases to 30,000 ppm, and the temperature in this area reaches 200°C. Additionally, the smoke transported to the lower-level galleries through the auxiliary fans results in temperatures of 60°C at the ends of the galleries. At 25 minutes, fresh air entering from the portal begins to affect the fire level. The smoke concentration in the main ramp decreases to 10,000 ppm, while in the fire zone, it exceeds 50,000 ppm. The temperature in the lower galleries remains at 110°C. At 30 minutes, the main ramp slowly begins to clear. Consequently, the smoke concentration at the ends of the inner galleries decreases to 10,000 ppm. However, smoke accumulation is observed in the fire zone, indicating poor ventilation. Meanwhile, the air temperature in the inner galleries drops to 90°C. By 90 minutes, it was observed that fire-related elements had almost entirely been removed from the mine. However, the smoke concentration in the lower galleries remains above 1,000 ppm, mainly due to weak airflow in these areas. The temperature in the lower galleries is 35°C, while in the fire zone, it is 40°C. The ventilation system has demonstrated successful results for this fire scenario. However, in the case of a stronger fire or a higher rate of smoke leakage from the inner galleries into the main gallery, the possibility of smoke and heat rising to the upper levels should not be overlooked.

Gas concentration levels over time in both the fire zone and the 990th-floor cross-cut gallery have been documented. In the fire zone, gas levels increase until the 16th minute, peaking at that time, and then decline to nearly 0 ppm by the 90th minute. On the 990th floor, the use of auxiliary fans transports smoke, causing gas concentrations to reach their maximum at the 30-minute mark, after which they decrease to nearly zero by the 120th minute.

3. Results and Discussion

This study rigorously evaluated the effectiveness of existing infrastructure in underground metal mines, focusing specifically on the performance of ventilation systems in the aftermath of potential fire incidents. By employing advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), simulations were conducted across three distinct fire scenarios. The findings offer comprehensive insights into the dynamics of heat release, the distribution of toxic gases, and the efficiency of gas evacuation within the ventilation system. This research not only highlights critical vulnerabilities but also underscores the necessity for robust safety measures in underground mining operations.

Fire scenarios featuring 25 MW blazes were strategically simulated at three distinct locations. It was anticipated that these fires would reach their peak temperature by the 10th minute and be successfully extinguished by the 20th minute. This approach allows to evaluate the effectiveness of fire management strategies under controlled conditions.

The analyses have pinpointed critical areas, smoke evacuation times, and key points of smoke accumulation.

In Fire Scenario 1, a fire at the mine entrance revealed an alarming trend. Smoke and heat rapidly spread from the main ramp into the lower levels. In the first three levels, where air gates were closed and no auxiliary fans were operational, it was observed substantial smoke penetration and accumulation in the inner galleries.

Strategically opening the air gates at these levels during a fire could significantly enhance the evacuation of smoke and heat, while simultaneously reducing the smoke that infiltrates the lower levels through the main ramp. Furthermore, dangerous smoke buildup was identified in the lower inner galleries, where air velocity is critically low.

It is imperative taking immediate action to address these vulnerabilities to ensure a safe working environment for all personnel.

The most critical finding in the second fire scenario is that toxic gases and heat increase in the environment very soon after the fire breaks out and then rapidly progress towards the lower production areas of the mine. This air descending to the lower floors rapidly penetrates the main ramp and cross-cut galleries. Auxiliary fans also contribute to this situation. In this case, stopping the auxiliary fans may be the right choice. The main reason is that the fire products rapidly enter the air inlet route. This dirty and hot air descending deep into the mine is directed more slowly to the air outlet. The main reason is that the air doors on the first three floors are open and the auxiliary fans create a pressure difference in the opposite direction on the intermediate floors. Thanks to this scenario, it has been learned that in addition to air doors, auxiliary fans are also crucial for employees’ lives in ventilation performance after the fire. In this way, it is imperative to save employees’ lives in emergency action strategically plans from a possible accident involving auxiliary fans.

The most critical finding in the second fire scenario is that toxic gases and heat begin to increase rapidly in the environment shortly after the fire breaks out and then quickly spread to the lower production areas of the mine. This hot and dirty air descends to the lower levels rapidly with the help of infiltrates the main ramp and cross-cut galleries. Auxiliary fans also contribute to this issue. In this case, it may be advisable to stop the auxiliary fans. The primary reason for this is that the products of combustion quickly enter the air intake path. The hot and contaminated air that descends deep into the mine is then more slowly directed to the air outlet. This slowdown occurs because the air doors on the first three floors are close and the auxiliary fans located lowel levels of mine create a pressure difference that opposes airflow.

This scenario highlights that, in addition to the air doors, auxiliary fans are crucial for the ventilation performance necessary to protect employees’ lives after a fire. Therefore, it is essential to strategically plan emergency actions that address the risks associated with auxiliary fans in order to safeguard employees’ lives in the event of a potential accident.

Local challenges, such as the buildup of hot smoke in confined spaces, highlight the importance of improving airflow. In Scenario 3, we observed that smoke from the fire gallery began rising towards the ceiling within just 6 minutes, demonstrating its natural tendency to ascend. This upward movement continued until the 25th minute, underscoring the need for proactive measures. In more intense fires, changing thermodynamic conditions can elevate smoke and heat through the main ramp, making it essential to address these airflow issues. Enhancing airflow can significantly enhance safety and reduce the risk of severe smoke accumulation during fire incidents.

In the course of the three fire scenarios, no reverse airflow formations were observed during the fire. However, it is crucial to closely monitor the entry of contaminated air from cross-cut galleries into the main ramp, given the challenging mine conditions. Suppose this polluted air is not effectively managed. In that case, it can mix with the clean air in the main ramp, potentially spreading to lower levels and significantly undermining the efficiency of our ventilation system. It is essential that proactive measures are taken to ensure the integrity of air quality and safeguard the safety of all personnel.

The study’s findings reveal significant deficiencies in the current ventilation system, particularly in key areas crucial for effective smoke evacuation. Furthermore, the strategic positioning of auxiliary fans plays a vital role in shaping post-fire smoke distribution and delivery. Through a comprehensive analysis of temperature distribution, toxic gas concentrations, and clean air flow directions during the fire, we identified critical risk points that demand immediate attention. The simulation results are striking: hot smoke accumulates in specific zones, while smoke evacuation is notably delayed in areas marked by low airflow speeds. This underscores the urgent need for improvements to ensure safety and efficiency in smoke management.

The study conclusively demonstrated that the strategic installation of air gates and auxiliary fans can dramatically enhance ventilation efficiency. Notably, the absence of reverse airflow formations during the fire is an encouraging finding; however, it is imperative to direct contaminated airflows with precision. Furthermore, the research underscored that air circulation can transform unpredictably during a fire, with stronger blazes causing smoke to ascend to upper levels. These insights highlight the critical importance of effective airflow management in fire scenarios.

Based on these analyses, optimising post-fire ventilation strategies, strengthening emergency action plans, enhancing the positioning of auxiliary fans and optimizing the air gates’ resistance is strongly recommended. This study underscores the critical importance of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analyses in significantly improving safety and efficiency within the mining industry. Expanding the application of numerical modelling is vital for developing safer and more sustainable underground ventilation systems in mines. Embracing these recommendations can foster a safer working environment and promote long-term operational resilience.

4. Conclusions

Ventilation of underground mines is a very complex situation that includes many parameters. Beyond providing sufficient air in mine galleries with just a fan, air quality, flow rate, humidity, direction, etc., should be taken into consideration. In addition to normal mine ventilation, this ventilation infrastructure is also expected to respond to sudden situations that may occur underground and pollute the air. In this case, many parameters such as fans, auxiliary fans, air doors, airways, airway resistances, and seasons come into play. Thanks to CFD studies, ventilation simulation of the entire underground operation has become possible with today’s technology. Simulation of ventilation performance in a mine can be done with CFD. In this simulation, the whole ventilation infrastructure of the mine can be represented. Although it is not the subject of this article, the results of this study have shown that studies that will increase the functionality of the ventilation on demand concept, which aims to transfer quality and sufficient air to the required area, can be done much closer to reality with CFD analyses. Most importantly, it is possible to obtain results that will both win time to resque and show the right way to ensure the healthy evacuation of workers from the mine in the event of a possible fire, with CFD models and analyses representing the entire mine.

On the other hand, the most important result of this study is that an underground mine with a very large volume is subject to cdf analysis as a whole. Because it is the first study to reveal that the direction of air flow changes as a fire in any part of the mine changes the thermodynamic conditions of the entire mine.

References

- Daloğlu, G. (2017). Modeling air velocity and methane behavior in underground mining operations using computational fluid dynamics (CFD). Doctoral Dissertation, Eskisehir Osmangazi University.

- Hansen, R. (2015). Study of heat release rates of mining vehicles in underground hard rock mines. Mälardalen University Press Dissertations No. 178.

- McPherson, M.J. (1993). Subsurface Ventilation and Environmental Engineering. Springer.

- Ndenguma, F. A computational fluid dynamics model for investigating airflow patterns in underground coal mine sections. Journal of The South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 2014.

- Prasad, N.; Lal, B. (2021). Analysis of heat stress in an underground coal mine using computational fluid dynamics. Civil and Environmental Engineering, Birla Institute of Technology.

- Sasmito, A.P.; Birgersson, E.; Ly, H.C.; Mujumdar, A.S. (2012). Some approaches to improve ventilation systems in underground coal mines - A computational fluid dynamic study. Minerals Metals Materials Technology Centre (M3TC), National University of Singapore.

- Yi, H.; Kim, M.; Lee, D.; Park, J. Applications of computational fluid dynamics for mine ventilation in mineral development. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, C.O.; Uyar Aksoy, G.G.; Fişne, A. (2019). Development of a basin mining model for occupational safety in Soma Kömürleri A.Ş.’s mines. DEPARK, İzmir.

- Aksoy, C.O.; Uyar Aksoy, G.G.; Fişne, A. (2017). Creating a beneficial model for ventilation and emergency safety measures in Eynez-Karanlıkdere Underground Coal Mine of İMBAT Mining Co. using CFD analysis.

- Aksoy, C.O.; Aksoy, G.G.U.; Fişne, A.; Alagöz, I.; Kaya, E. Investigation of a conveyor belt fire in an underground coal mine: Experimental studies and CFD analysis. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 2023, 123, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahif, R.; Attia, S. CFD Assessment of Car Park Ventilation System in Case of Fire Event. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, X.; Liu, J. Numerical Simulation of the Ventilation and Fire Conditions in an Underground Garage with an Induced Ventilation System. Buildings 2023, 13, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, C.; Năstase, I.; Bode, F.; Calotă,, R. Smoke and Hot Gas Removal in Underground Parking Through Computational Fluid Dynamics: A State of the Art and Future Challenges. Fire 2024, 7, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Nie, G.; Li, G.; Zhao, W.; Sheng, B. Optimization of Branch Airflow Volume for Mine Ventilation Network Based on Sensitivity Matrix. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Z. Experiments on a Mine System Subjected to Ascensional Airflow Fire and Countermeasures for Mine Fire Control. Fire 2024, 7, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).