1. Introduction

The building and construction sector accounts for approximately 40% of global primary energy consumption and over 30% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, positioning it as a key contributor to climate change and the urban heat island effect [

1,

2]. In response, considerable effort has been directed toward developing strategies that reduce operational energy demand while addressing the broader environmental and thermal challenges of urbanization. These strategies range from passive design interventions—such as thermal insulation, natural ventilation, and solar shading—to advanced solutions incorporating renewable energy systems, phase-change materials, and hybrid control mechanisms [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

A central driver of these advancements is the integration of computational tools for simulating and optimizing building energy performance. Physics-based simulation models enable detailed thermal analysis by incorporating envelope characteristics, occupancy schedules, and site-specific climatic conditions [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. When combined with optimization algorithms, these models support the systematic evaluation of design alternatives across multiple, often conflicting objectives. Concurrently, Machine Learning (ML) techniques have emerged as powerful data-driven tools for pattern recognition, energy forecasting, and system control. Supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning methods offer capabilities for adaptive control, anomaly detection, and demand prediction with increasing accuracy and autonomy [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Together, simulation and ML-based frameworks facilitate robust, dynamic, and intelligent building energy management, accounting for environmental, behavioral, and operational complexities [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Optimization frameworks in this domain commonly target objectives such as minimizing energy consumption, reducing costs, and mitigating environmental impacts, while satisfying thermal comfort requirements and regulatory constraints. Design variables often span envelope configuration, insulation levels, glazing ratios, HVAC operational parameters, and material choices [

27,

28]. These frameworks serve as essential tools for navigating tradeoffs among energy efficiency, economic viability, and occupant comfort, supporting data-informed, performance-driven design decisions [

29].

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a simulation-based multi-objective optimization framework for improving both the energy and economic performance of residential buildings, using a single-family dwelling in Patras, Greece, as a case study. Building on the review presented in section 2, the study focuses on minimizing two conflicting objective functions—annual thermal energy demand and construction material cost—under realistic climatic and architectural constraints. The proposed approach integrates MATLAB’s [

30] multi-objective genetic algorithm with a modular Excel interface, enabling dynamic scenario generation and scalability for diverse use cases. A key aspect of the investigation is the sensitivity analysis of optimization hyperparameters, specifically population size, number of generations, and mutation rate, with respect to their influence on convergence quality and Pareto front resolution. The overarching objective is to provide a reproducible, adaptable framework that supports informed design decision-making in the early stages of residential project development.

The novelty of this work lies in its structured application of a flexible simulation–optimization platform, capable of accommodating diverse design inputs and boundary conditions through a modular Excel–MATLAB interface. Unlike many conventional studies limited by static configurations or narrow performance criteria, this study explores the influence of varying hyperparameter settings on the quality of optimization results. This enables a deeper understanding of how algorithmic configurations shape solution space coverage and Pareto front quality. The methodological flexibility ensures the approach can be readily adapted to different building typologies, climates, and performance objectives. By bridging algorithmic precision with practical design workflows, this study advances the integration of optimization techniques into real-world building design processes.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents a comprehensive review of simulation-based optimization techniques in energy-efficient building design.

Section 3 details the methodological framework, including the case study context, model setup, definition of objectives and design parameters, and optimization implementation.

Section 4 reports and discusses the optimization results, with particular attention to the influence of hyperparameter settings on solution quality and decision-support potential. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of key findings and recommendations for further research.

2. Simulation-Based Approaches for Multi-Objective Energy Optimization in Buildings

The ongoing effort to lower energy consumption in buildings has been significantly aided by advancements in Building Performance Simulation (BPS) tools. These tools simulate the complex, time-dependent behavior of building systems and have played a key role in enabling energy-conscious design, enhancing indoor comfort conditions, and supporting the adoption of sustainable construction strategies. With improvements in computational capabilities and the emergence of sophisticated optimization algorithms, the field has transitioned from simple parametric studies to fully integrated simulation–optimization environments. Such environments combine simulation platforms with advanced search techniques, promoting a more structured and data-informed approach to designing high-performance buildings.

Traditional approaches to evaluating building performance often utilize parametric analyses, which involve varying a single input parameter at a time to observe its individual effect. While these studies have provided initial guidance, they are limited by assumptions of linearity, an inability to reflect interactions between multiple parameters, and a lack of computational efficiency. Critically, they rarely identify truly optimal configurations. In response to these shortcomings, Simulation-Based Optimization (SBO) techniques have emerged as a more robust alternative. SBO methods combine simulation tools—such as EnergyPlus [

31] or TRNSYS [

32]—with optimization algorithms that iteratively search for superior design solutions. This integration supports the resolution of complex, multi-objective design problems, where tradeoffs must be made between energy use, occupant comfort, environmental performance, and cost considerations [

33,

34,

35].

2.1. Classification of Simulation-Based Optimization Methods

SBO methods comprise a wide array of algorithmic methods, which can be classified according to their approach to navigating the search space and managing problem constraints. The choice of a suitable optimization technique is largely dictated by the specific features of the problem at hand—such as the number of decision variables, the type of variables involved (e.g., continuous, discrete, or hybrid), and the mathematical properties of the objective functions, including whether they are linear or nonlinear, convex or non-convex [

11,

36,

37,

38,

39].

Deterministic optimization techniques—such as Linear Programming (LP), Non-Linear Programming (NLP), and Integer Programming (IP)—use formal mathematical models to derive optimal solutions [

40,

41,

42,

43]. These methods are typically efficient and well-suited for problems with convex structures and clearly defined constraints. However, their applicability in practical building design is limited, as real-world scenarios often involve nonlinear behavior, intricate constraints, and a mix of continuous and discrete variables.

Metaheuristic and evolutionary algorithms —including Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Simulated Annealing (SA), and ant Colony Optimization (ACO)—have demonstrated strong performance in the context of building design optimization [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. Drawing inspiration from natural and biological systems, these approaches are particularly effective in exploring large, complex search spaces with multiple local optima. Unlike gradient-based methods, they do not require derivative information, which makes them well-suited for nonlinear problems. Their ability to escape local minima is especially beneficial in optimizing various building parameters such as thermal insulation, HVAC configurations, lighting strategies, and occupancy-related controls.

Gradient-based methods, such as gradient descent and conjugate gradient methods, utilize derivative information to guide the search toward optimal solutions [

16,

17,

50]. While these algorithms are generally efficient when applied to smooth and continuously differentiable problems, their effectiveness is often limited in building optimization contexts [

36,

40]. This is due to challenges like entrapment in local optima and high sensitivity to initial parameter values, which are common in the highly nonlinear nature of building energy models.

Stochastic and direct-search techniques—including dynamic programming, tabu search, and pattern search—investigate the solution space using probabilistic strategies or predefined heuristic rules [

18,

19,

20,

21]. These approaches are known for their robustness and simplicity in implementation [

51]. However, they often demand significant computational resources, particularly when applied to large-scale optimization problems involving multiple, interrelated objectives.

Among the various optimization approaches, multi-objective evolutionary algorithms—especially the Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II)—have gained widespread adoption in building performance studies [

36,

52]. Their strength lies in generating Pareto-optimal solution sets, which enable designers to assess tradeoffs between conflicting objectives, such as minimizing energy consumption while maintaining thermal comfort, without committing to a single optimal outcome [

36,

44,

48].

2.2. Integration of Simulation and Optimization: Methods and Applications

SBO methods of building performance typically rely on two fundamental components: (a) a dynamic simulation tool capable of accurately modeling building behavior across various design alternatives, and (b) an optimization algorithm that systematically explores possible configurations to identify those that satisfy predefined performance criteria.

The combined use of simulation and optimization facilitates informed decision-making during both the early design phase and building retrofit processes. It enables a thorough investigation of the design space across a wide range of applications, including optimization of the building envelope, HVAC systems, daylight utilization, spatial layout, and construction material choices [

25,

26,

53]. Common design variables targeted in optimization studies include building geometry, insulation levels, glazing characteristics, window-to-wall ratios, HVAC operating parameters, and passive design elements like shading devices or thermal mass [

29,

54,

55]. The performance criteria, or objective functions, often focus on indicators such as annual energy use, thermal comfort (e.g., PMV, hours of discomfort), Life-Cycle Cost (LCC), and carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions—or a weighted combination of these. In multi-objective settings, Pareto-based methods such as NSGA-II are widely used to explore tradeoffs among competing goals and provide a range of balanced solutions [

12,

44,

48,

56].

SBO has seen extensive application in both newly constructed and existing buildings, consistently contributing to enhanced energy efficiency, occupant comfort, and reduced environmental impact. Empirical research emphasizes the critical role of the building envelope—especially insulation and glazing—in determining thermal performance [

22,

24,

25]. Additionally, SBO approaches provide valuable guidance in selecting design solutions that align with budgetary limits, regulatory requirements, and broader sustainability objectives.

Although SBO methods have demonstrated considerable effectiveness, they are not without limitations. One of the primary challenges is the high computational cost associated with coupling dynamic simulations with sophisticated optimization algorithms. Additional difficulties arise from modeling uncertainties, the variability of occupant behavior, and the need to simplify real-world complexities for practical implementation [

54,

57,

58]. As a result, achieving a balance between model accuracy and usability often requires careful selection and limitation of the design parameters included in the analysis. Despite these challenges, a broad body of literature affirms that SBO serves as a powerful tool for performance-oriented building design. When applied appropriately, it allows architects, engineers, and decision-makers to uncover optimal or near-optimal solutions that successfully balance energy efficiency, occupant comfort, cost considerations, and environmental impact [

56,

58,

59,

60].

3. Methodology

This section describes the methodological approach adopted to evaluate how simulation-based multi-objective optimization can improve both energy efficiency and construction cost in residential buildings. A real-world case study involving a detached single-family house located in Patras, Greece, is used to demonstrate the combined use of climatic data, detailed building parameters, optimization modeling, and computational tools.

3.1. Climatic Context and Building Description

The residential building examined in this study is located in the city of Patras, western Greece (38.25°N latitude, 21.73°E longitude), with elevations ranging from 0 to 100 meters above sea level. According to the Köppen–Geiger classification, Patras falls within the climatic zone, characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters.

To support accurate energy modeling, particularly heating demand estimation, the study uses long-term climatic data in the form of Heating Degree Days (HDD), provided by the National Observatory of Athens (NOA). The dataset includes monthly values for the period 2010 to 2021, calculated with a base indoor temperature of 18°C. Table 3.1 summarizes the monthly HDD values for Patras, totaling 766 HDD annually [

61].

Table 1.

Monthly Heating Degree Days (HDD) for Patras (2010–2021).

Table 1.

Monthly Heating Degree Days (HDD) for Patras (2010–2021).

| Month |

HDD value |

| January |

199 |

| February |

156 |

| March |

131 |

| April |

58 |

| May |

10 |

| June |

0 |

| July |

0 |

| August |

0 |

| September |

2 |

| October |

11 |

| November |

50 |

| December |

149 |

| Total (annual) |

766 |

The building under analysis is a single-story, detached residential unit representative of low-rise housing in Greece. It includes five functional spaces: kitchen, living room, dining area, bedroom, and bathroom. Each space is naturally ventilated and illuminated, and the structure has two external doors. The internal ceiling height is uniformly 2.75 meters. Geometric modeling was carried out using simplified envelope data. Table 3.2 provides the surface areas of the building’s elements.

Table 2.

Surface areas of building elements.

Table 2.

Surface areas of building elements.

| Building element |

Area (m2) |

| Floor, Roof |

92.36 |

| Walls |

85.06 |

| Windows |

18.89 |

| Doors |

4.62 |

| Internal walls |

65.75 |

3.2. Optimization Framework

An SBO framework was employed to simultaneously reduce energy consumption and material costs. The optimization was conducted in MATLAB using the Global Optimization Toolbox, specifically through the gamultiobj function. This function implements a Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA), which is well-suited for addressing continuous, nonlinear, and multi-modal optimization problems. The algorithm progresses by evolving a population of candidate solutions using genetic operators such as selection, crossover, mutation, and elitism. Critical parameters—including the number of individuals per generation, total generations, and mutation probability—are specified by the user.

In this study, typical settings involved 100 to 150 individuals per generation across 50 to 75 generations, with mutation rates ranging from 0.03 to 0.05. The result is a Pareto front that illustrates the tradeoffs among competing design objectives. For greater flexibility and ease of use, the optimization algorithm was integrated with a modular Microsoft Excel interface. This linkage enables users to modify input parameters—such as design variables, material specifications, and building features—without directly editing the MATLAB source code.

3.2.1. Objective Functions

The optimization targets two competing objectives: (1) minimizing the building’s annual thermal energy demand, and (2) reducing the cost of construction materials.

The first objective function, denoted as

and expressed in kWh/year, represents the heating energy required to maintain indoor thermal comfort. It is influenced by the thermal properties of the building envelope and the prevailing climatic conditions at the building location. The thermal demand (

) values are estimated using HDD data and the overall thermal transmittance of the building, represented by a weighted-average U-value (

) along and adjustment factors accounting for orientation, building height, and heating duration. The calculation is based on a simplified steady-state heat transfer model based that employes the HDD concept to approximate the cumulative temperature difference between indoor and outdoor environmental conditions over the heating season [

62]. The thermal demand (

) is thus calculated as a function of geometrical and operational factors affecting heat losses [

62,63]:

where HDD is the annual heating degree days,

is the weighted-average U value of the entire building envelope,

is the total surface area of the building,

accounts for heat losses due to infiltration and ventilation, and

,

, and

are adjustment multipliers for orientation, heating duration, and height.

The second objective function is the material cost of construction (in €), which represents the total cost of key building components such as insulation, glazing, and wall assemblies. The construction material cost, denoted as

(in €), can be expressed as follows [63]:

represents the cost of the building’s foundations, as well as the beams and columns of the structure, assuming they are made of reinforced concrete. For simplification, this cost is assumed to be fifteen thousand euros (€15,000), which is considered reasonable for a residential building with a living area of around 80 m

2. Among the other symbols,

is the specific cost of the roof (in €/m²),

is the specific cost of the floor (in €/m²),

is the specific cost of the walls (in €/m²),

is the area of the internal walls (included to account total material cost),

is the specific cost of the insulation applied to the building (in €/m²),

is the cost of the doors, and

is the specific cost of the windows (in €/m²). Finally,

is the total insulated area (in m²), including exterior walls, the roof and the floor:

Equation 2 is based on a bottom-up construction cost estimation approach, widely used in early-stage building design and life cycle cost analyses [

29,63].

Additional construction expenses—such as labor, permits, and administrative costs—were excluded from the analysis due to their significant regional variability and lack of standardization. The selected objectives reflect key priorities in the early design phase of residential buildings, where tradeoffs between energy performance and financial feasibility must be carefully balanced. Reducing thermal energy demand supports environmentally sustainable design and enhances indoor comfort, while limiting material costs is essential for ensuring that energy-efficient solutions remain both economically viable and broadly implementable.

3.2.2. Design Variables

The optimization process considers 12 design variables that characterize both the thermal performance and material costs of the building envelope. These variables are grouped into two main categories: (a) U-values, representing the thermal transmittance of the roof, floor, external walls, windows, doors, and insulation layers; and (b) unit costs of materials for building surfaces (in €/m²) and doors (in €/unit).

Each material complies with standardized thermal performance values defined by the Technical Chamber of Greece, ensuring alignment with national building energy regulations. Cost data were collected from regional suppliers in Patras, with the flexibility to adapt the dataset for alternative scenarios. To maintain consistency, each thermal transmittance value is directly linked to a corresponding material cost. Combinations deemed unrealistic or non-compliant are penalized during the optimization run. The material palette includes various types of insulation—such as EPS, XPS, GEPS, mineral wool, and polyurethane—as well as variations in wall assemblies, glazing systems, and structural components for floors, roofs, and doors.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents a critical evaluation of the results obtained from the simulation-based multi-objective optimization framework, aiming to assess the effectiveness of the MATLAB-based algorithm in navigating the design space and identifying robust Pareto-optimal solutions. Emphasis is placed on the influence of key algorithmic hyperparameters—namely, population size, maximum number of generations, and mutation rate—on convergence dynamics, diversity of solutions, and the resolution of the Pareto front.

To enable a systematic analysis, four optimization scenarios were executed, each defined by a distinct configuration of the hyperparameters. In each scenario, only one parameter was varied at a time, thereby isolating and enabling the evaluation of its specific impact on the behavior and efficiency of the optimization process. The specific values assigned in each scenario are summarized in

Table 3.

The performance of the optimization process is assessed by analyzing the structure of the Pareto front and the density of solution points across the objective space. In multi-objective optimization, a well-formed Pareto front is typically smooth and continuous, allowing for the identification of high-quality, non-dominated solutions. Discontinuities, jagged edges, or sparsely populated regions may indicate inadequate convergence or limited search space exploration.

The optimization outcomes are illustrated through a series of comparative diagrams, each representing the tradeoff landscape between the two conflicting objectives: annual thermal energy demand and construction material cost. The shape, density, and continuity of the Pareto front are employed as qualitative indicators of the algorithm’s exploratory capacity and optimization performance.

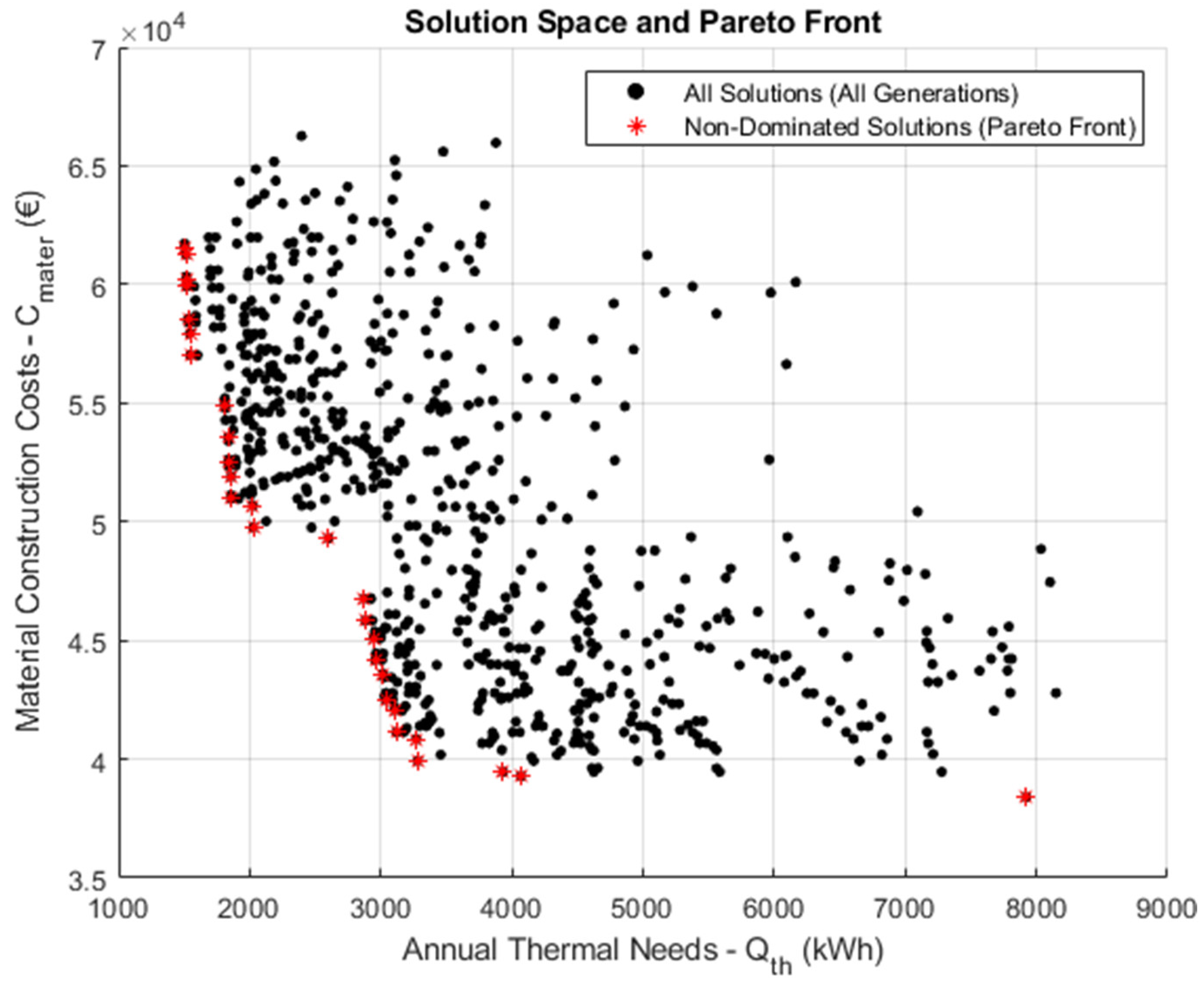

In Scenario 1 (

Figure 1), which corresponds to the lowest-resolution configuration—comprising a population size of 100, a maximum of 50 generations, and a relatively high mutation rate of 0.10—the algorithm successfully generates a broad set of feasible solutions. Nonetheless, the resulting Pareto front displays discernible discontinuities along both objective axes (i.e., material cost and annual thermal energy demand), indicating incomplete exploration of the design space. Despite these irregularities, the Pareto front generally preserves the expected concave (hyperbolic) profile characteristic of bi-objective optimization problems. The distribution of objective function values remains within technically acceptable bounds, affirming the basic validity of the optimization process under this minimal configuration. However, the observed gaps and uneven density of solutions emphasize the sensitivity of the algorithm’s performance to hyperparameter selection—particularly the role of mutation rate and computational budget in achieving adequate search space coverage.

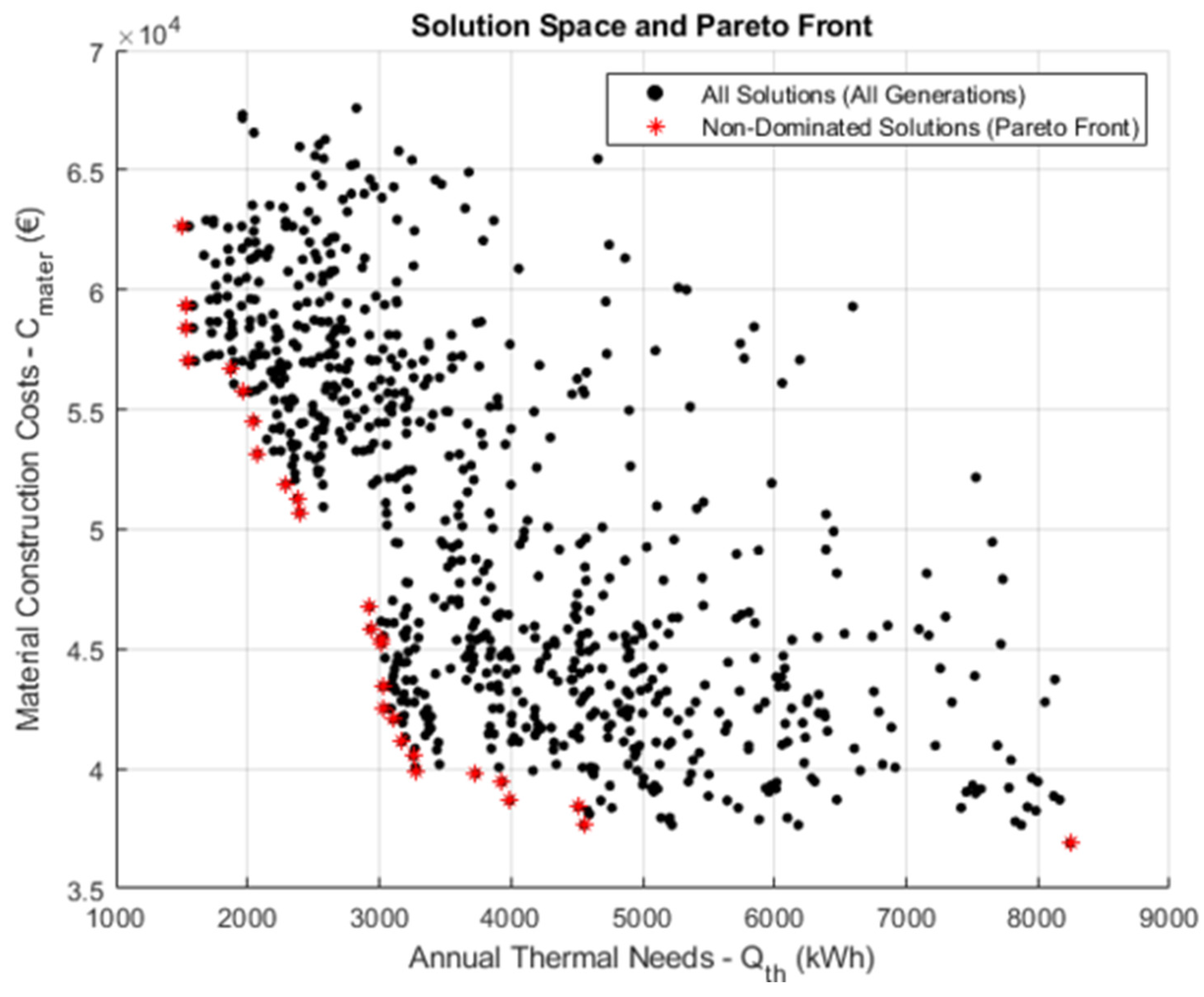

Scenario 2 investigates the effect of reducing the mutation rate from 0.10 to 0.04, while keeping the population size and number of generations constant at 100 and 50, respectively. This lower mutation rate constrains the magnitude of variation introduced between generations, resulting in smaller incremental changes within the design variable space. While such fine-tuning is generally conducive to improved accuracy, it also slows the algorithm’s capacity to explore the solution space effectively. The resulting diagram (

Figure 2) bears superficial resemblance to that of Scenario 1; however, a more detailed examination reveals a more jagged and fragmented Pareto front, along with a sparser distribution of solutions across the objective space. These patterns point to diminished search space coverage and reduced convergence performance under the current computational constraints. Importantly, the observed limitations are not solely attributable to the lower mutation rate. Rather, the effectiveness of a reduced mutation rate typically relies on extended search efforts—namely, an increased number of generations and/or larger population sizes—to counterbalance the slower evolutionary dynamics. In this configuration, the restricted number of generations impeded the algorithm’s ability to fully leverage the benefits of a more conservative mutation strategy. Consequently, Scenario 2 illustrates the inherent tradeoff between search precision and convergence rate when calibrating mutation-related hyperparameters.

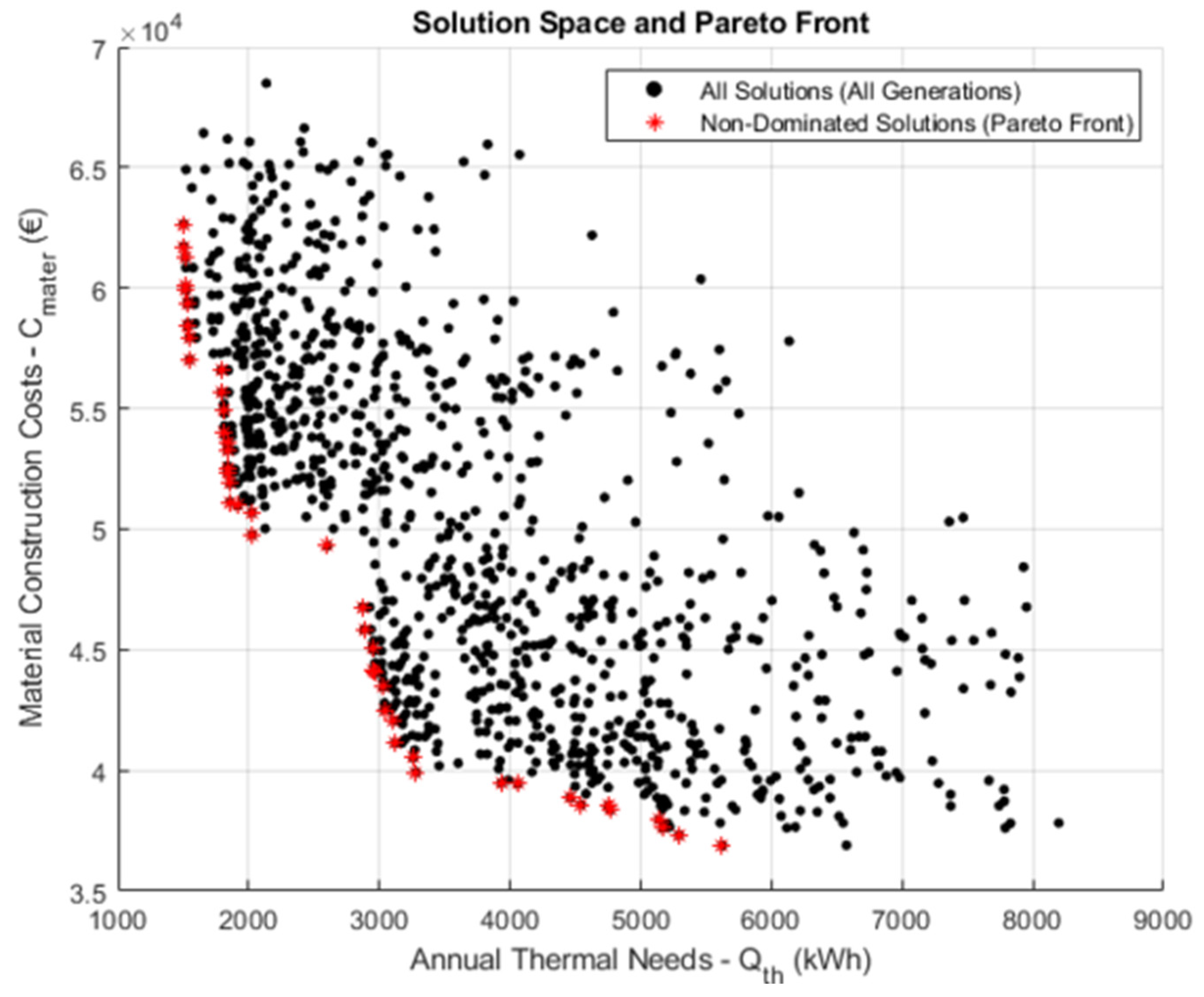

Scenario 3 isolates the influence of population size by increasing it from 100 to 200, while holding both the number of generations (50) and the mutation rate (0.04) constant—identical to the configuration used in Scenario 2. This modification aims to assess how a larger population affects solution diversity, convergence behavior, and the overall quality of the Pareto front. As illustrated in

Figure 3, expanding the population size markedly improves the resolution and uniformity of the search space. The resulting Pareto front is smoother, more densely populated, and exhibits fewer discontinuities compared to Scenario 2. The tradeoff surface between thermal energy demand and construction material cost appears more continuous, reflecting improved exploration and convergence characteristics. These enhancements align with theoretical expectations: a larger population enables broader sampling of the design space within each generation, increasing the likelihood of identifying non-dominated solutions and reducing the risk of premature convergence. The comparative findings underscore that population size plays a critical role in enhancing both the diversity and robustness of the optimization outcomes—particularly under conditions of low mutation rate and limited generational depth.

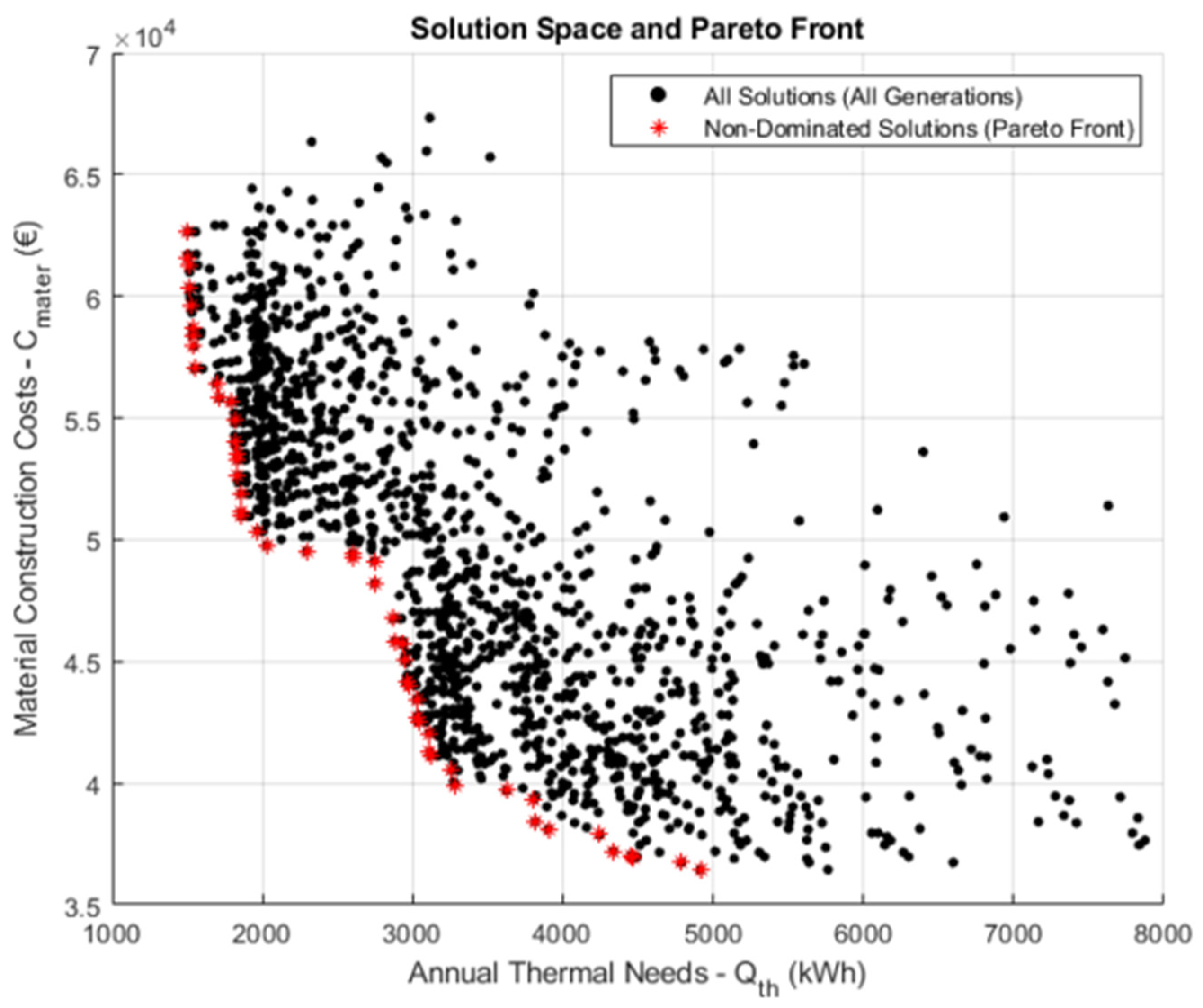

Scenario 4 represents the highest-resolution configuration explored in this study, combining an expanded population size (200) with an increased number of generations (100) and a low mutation rate (0.04). This setup was designed to maximize both the breadth and depth of the evolutionary search, thereby improving the algorithm’s ability to identify high-quality Pareto-optimal solutions. While this configuration entails a higher computational cost, it provides greater opportunities for both exploration of the design space and refinement of convergence behavior. As shown in

Figure 4, the resulting Pareto front exhibits the highest level of continuity and density among all tested scenarios. The solution space is thoroughly covered, with minimal discontinuities and a well-distributed set of non-dominated solutions. The tradeoff curve maintains a generally concave (hyperbolic) shape, although minor irregularities persist, consistent with those observed in previous scenarios. These deviations may be attributed to two factors. First, the discretization of design variables—stemming from the use of a finite set of material options—can inherently limit the smoothness of the Pareto front. Second, even with extended evolutionary cycles, low mutation rates may constrain the algorithm’s ability to traverse sparsely populated regions of the solution space, particularly when separated by large performance gaps. Nevertheless, the consistency of these anomalies across all scenarios suggests they are not artifacts of algorithmic failure but rather intrinsic features of the optimization landscape defined by the problem’s structure and variable granularity.

A defining feature of multi-objective optimization is the existence of tradeoffs between conflicting objectives. In this study, the dual goals of minimizing annual thermal energy demand and construction material cost illustrate this tension. These objectives are inherently at odds—reducing energy demand often requires higher-performance (and therefore costlier) materials, while minimizing cost may compromise thermal efficiency. The optimization process yields a Pareto front, which represents the set of non-dominated solutions. Each point on this front offers a unique compromise between the two objectives, and any solution not on the front is suboptimal, being outperformed in at least one criterion by a Pareto-optimal alternative.

Navigating the Pareto front empowers decision-makers—whether architects, engineers, or investors—to select solutions that align with project-specific priorities, such as budget constraints or sustainability goals. Moving along the front quantifies the tradeoffs: for instance, a shift toward lower thermal demand typically incurs increased material cost, and vice versa. While no single solution on the Pareto front is universally optimal, the concept of a utopia point—a theoretical minimum for both objectives—can serve as a reference. Selecting the Pareto solution nearest to this point (e.g., using Euclidean distance) provides a structured approach for identifying balanced tradeoffs when simultaneous minimization of both objectives is unattainable. Overall, the Pareto front acts as a robust decision-support mechanism, facilitating transparent, data-driven evaluation of alternatives. The algorithmic framework presented—reinforced by sensitivity analysis across multiple hyperparameter configurations—demonstrates both its effectiveness and adaptability for performance-based building design under competing objectives.

5. Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

The present study investigated the implementation of a simulation-based multi-objective optimization framework aimed at enhancing the energy and economic performance of residential buildings, using a single-family dwelling in Patras, Greece, as a case study. The methodology integrated a physics-based simulation model with a MOGA executed in MATLAB and coupled with a modular Excel interface to enable flexible scenario definition and input management. The optimization targeted two inherently conflicting objectives: minimizing annual thermal energy demand and reducing construction material costs.

A parametric evaluation of key algorithmic hyperparameters—population size, mutation rate, and maximum number of generations—was conducted across four distinct optimization scenarios. The findings revealed that the algorithm’s performance and the quality of the resulting Pareto fronts are highly dependent on the hyperparameter configurations. Larger population sizes and more generations contributed to a more continuous and densely populated Pareto front, enhancing the exploration of the solution space. Conversely, lower mutation rates yielded finer local search resolution but required sufficient iterations to prevent premature convergence or limited search coverage. In contrast, configurations with reduced computational effort or higher mutation rates resulted in irregular and less comprehensive solution sets, underscoring the critical tradeoffs between computational efficiency and optimization fidelity.

The proposed framework demonstrated robustness in generating technically viable and diverse non-dominated solutions, facilitating informed, performance-driven decision-making during early-stage building design. Furthermore, the integration of a modular Excel-MATLAB interface provides a scalable and user-adaptable platform that accommodates variations in climatic conditions, design parameters, and material databases, thereby broadening its applicability across different residential contexts and geographical regions.

The present research contributes to the advancement of simulation-based optimization methodologies by providing a reproducible, adaptable, and practical tool for multi-objective building performance assessment. Future extensions may include incorporating additional objectives, such as life cycle environmental impacts or occupant thermal comfort indices, integrating real-time operational data, or coupling with machine learning algorithms to further improve prediction accuracy and adaptive control capabilities.

List of Abbreviations

| ACO |

Ant Colony Optimization |

| BPS |

Building Performance Simulation |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| GHG |

Greenhouse Gas |

| HDD |

Heating Degree Days |

| HVAC |

Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning |

| IP |

Integer Programming |

| LCC |

Life Cycle Cost |

| LP |

Linear Programming |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MOGA |

Multi Objective Genetic Algorithm |

| NLP |

Nonlinear Programming |

| NOA |

National Observatory of Athens |

| NSGA-II |

Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| PMV |

Predicted Mean Vote |

| PSO |

Particle Swarm Optimization |

| SA |

Simulated Annealing |

| SBO |

Simulation-Based Optimization |

References

- International Energy Agency, Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction, Paris, 2019. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-status-report-for-buildings-and-construction-2019, Licence: CC BY 4.0.

- M. Santamouris, K. Vasilakopoulou, Present and future energy consumption of buildings: Challenges and opportunities towards decarbonisation, E-Prime - Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 1 (2021) 100002. [CrossRef]

- G. Mihalakakou, M. Souliotis, M. Papadaki, G. Halkos, J. Paravantis, S. Makridis, S. Papaefthimiou, Applications of earth-to-air heat exchangers: A holistic review, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 155 (2022) 111921. [CrossRef]

- G. Mihalakakou, M. Souliotis, M. Papadaki, P. Menounou, P. Dimopoulos, D. Kolokotsa, J.A. Paravantis, A. Tsangrassoulis, G. Panaras, E. Giannakopoulos, S. Papaefthimiou, Green roofs as a nature-based solution for improving urban sustainability: Progress and perspectives, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 180 (2023) 113306. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Chwieduk, Towards modern options of energy conservation in buildings, Renew. Energy 101 (2017) 1194–1202. [CrossRef]

- X. Cao, X. Dai, J. Liu, Building energy-consumption status worldwide and the state-of-the-art technologies for zero-energy buildings during the past decade, Energy Build. 128 (2016) 198–213. [CrossRef]

- A.N. Tombazis, S.A. Preuss, Design of passive solar building in urban areas, Sol. Energy 70 (2001) 311–318. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Athienitis, Thermal Analysis and Design of Passive Solar Buildings, 1st Edition, Routledge, 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. Kappou, M. Souliotis, S. Papaefthimiou, G. Panaras, J.A. Paravantis, E. Michalena, J.M. Hills, A.P. Vouros, K. Dimenou, G. Mihalakakou, Review Cool Pavements: State of the Art and New Technologies, Sustain. 14 (2022). [CrossRef]

- A. Giannadakis, A. Romeos, I. Kalogirou, D.I. Dimopoulos, G.P. Trachanas, V. Marinakis, G. Mihalakakou, Energy performance analysis of a passive house building, Energy Sources, Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 20 (2025). [CrossRef]

- T.R. Nielsen, Optimization of buildings with respect to energy and indoor environment, Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Byg Rapport No. R-036, 2003.

- V. Machairas, A. Tsangrassoulis, K. Axarli, Algorithms for optimization of building design: A review, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 31 (2014) 101–112. [CrossRef]

- F. Rothlauf, Design of Modern Heuristics, 1st Editio, Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Wetter, GenOpt - A Generic Optimization Program, Seventh Int. IBPSA Conf. 7 (2001) 601–608. [CrossRef]

- Hwang C. L., Masud A. S. Md., Multiple Objective Decision Making—Methods and Applications, Springer-Velag, 1979.

- N. Qian, On the momentum term in gradient descent learning algorithms, Neural Networks 12 (1999) 145–151. [CrossRef]

- H.I. Ahmed, E.T. Hamed, H. Th Saeed Chilmeran, A Modified Bat Algorithm with Conjugate Gradient Method for Global Optimization, (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. Nayak, Fundamentals of Optimization Techniques with Algorithms, 1st Edition, Elsevier, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Chelouah, P. Siarry, Tabu search applied to global optimization, Eur. J. Oper. Res. 123 (2000) 256–270. [CrossRef]

- R. Hooke, T.A. Jeeves, “Direct Search” Solution of Numerical and Statistical Problems, J. ACM 8 (1961) 212–229. [CrossRef]

- T.G. Kolda, R.M. Lewis, V. Torczon, Optimization by Direct Search: New Perspectives on Some Classical and Modern Methods, Soc. Ind. Apllied Math. 45 (2003) 385–482. [CrossRef]

- F. Kheiri, A review on optimization methods applied in energy-efficient building geometry and envelope design, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 92 (2018) 897–920. [CrossRef]

- J.S. Gero, N. D’Cruz, A.D. Radford, Energy in context: A multicriteria model for building design, Build. Environ. 18 (1983) 99–107. [CrossRef]

- P. Heiselberg, H. Brohus, A. Hesselholt, H. Rasmussen, E. Seinre, S. Thomas, Application of sensitivity analysis in design of sustainable buildings, Renew. Energy 34 (2009) 2030–2036. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, J.L. Niu, Optimal building envelope design based on simulated performance: History, current status and new potentials, Energy Build. 117 (2016) 387–398. [CrossRef]

- V.J.L. Gan, I.M.C. Lo, J. Ma, K.T. Tse, J.C.P. Cheng, C.M. Chan, Simulation optimisation towards energy efficient green buildings: Current status and future trends, J. Clean. Prod. 254 (2020) 120012. [CrossRef]

- C. Deb, F. Zhang, J. Yang, S.E. Lee, K.W. Shah, A review on time series forecasting techniques for Building energy consumption, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 74 (2017) 902–924. [CrossRef]

- G. Shi, D. Liu, Q. Wei, Prediction of energy consumption in office buildings based on echo state network, Proc. World Congr. Intell. Control Autom. 2016-Septe (2016) 895–899. [CrossRef]

- A.T. Nguyen, S. Reiter, P. Rigo, A review on simulation-based optimization methods applied to building performance analysis, Appl. Energy 113 (2014) 1043–1058. [CrossRef]

- MathWorks, MATLAB, Version R2024a, Natick, Massachusetts, USA, 2024, (2024). https://www.mathworks.com.

- U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Plus: Weather Data, (2024). https://energyplus.net/weather.

- S.A. Klein, TRNSYS 18: A Transient System Simulation Program, (2017). http://sel.me.wisc.edu/trnsys.

- J.A. Wright, H.A. Loosemore, R. Farmani, Optimization of building thermal design and control by multi-criterion genetic algorithm, Energy Build. 34 (2002) 959–972. [CrossRef]

- S. Attia, M. Hamdy, W. O’Brien, S. Carlucci, Assessing gaps and needs for integrating building performance optimization tools in net zero energy buildings design, Energy Build. 60 (2013) 110–124. [CrossRef]

- T. Al Mindeel, E. Spentzou, M. Eftekhari, Energy, thermal comfort, and indoor air quality: Multi-objective optimization review, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 202 (2024) 114682. [CrossRef]

- R. Evins, A review of computational optimisation methods applied to sustainable building design, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 22 (2013) 230–245. [CrossRef]

- S.R. Branke J., Deb K., Miettinen K., Multi-objective optimization: Interactive and Evolutionary Approaches, 1st Editio, Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008. [CrossRef]

- D.E. Goldberg, Genetic algorithms in search, optimization, and machine learning, Publishing Co., Inc.75 Arlington Street, Suite 300 Boston, MAUnited State, 1989.

- E. Taveres-Cachat, F. Goia. Exploring the impact of problem formulation in numerical optimization: A case study of the design of PV integrated shading systems. Building and Environment 188 (2021) 107422. [CrossRef]

- J. Nocedal, S.J. Wright, Numerical optimization, 2nd Editio, Springer Series in Operations Research and Financial Engineering, 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Chanas, P. Zieliński, On the equivalence of two optimization methods for fuzzy linear programming problems, Eur. J. Oper. Res. 121 (2000) 56–63. [CrossRef]

- W.H. Swann, A survey of non-linear optimization techniques, FEBS Lett. 2 (1969). [CrossRef]

- L. Wolsey, Integer Programming, John Wiley & Sons, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Deb, A. Pratap, S. Agarwal, T. Meyarivan, A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II, IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 6 (2002) 182–197. [CrossRef]

- D.E. Goldberg, Genetic algorithms in search, optimization, and machine learning, Publishing Co., Inc.75 Arlington Street, Suite 300 Boston, MAUnited State, 1989.

- Kennedy, J., Eberhart, R., Particle swarm optimization, in: Proc. ICNN’95 - Int. Conf. Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Aust. 1995, 1995: pp. 1942–1948. [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M., Maniezzo, V., Colorni, A., Ant system: optimization by a colony of cooperating agents, in: IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Part B (Cybernetics), Vol. 26, 1996: pp. 29–41. [CrossRef]

- K. Deb, Multi-Objective Optimization using Evolutionary Algorithms, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., United States, 2001.

- A.E. Eiben, J.E. Smith, Introduction to evolutionary computing: Natural Computing Series, 2nd editio, Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kegl, M., Butinar, B. J., Kegl, B., An efficient gradient-based optimization algorithm for mechanical systems, Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng. 18 (2002) 363–371. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-S. (2014). Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms. Elsevier.

- Asadi, E., Silva, M. G., Antunes, C. H., Dias, L., & Glicksman, L. (2014). Multi-objective optimization for building retrofit: A model using genetic algorithm and artificial neural network and an application. Energy and Buildings, 81, 444–456. [CrossRef]

- S. Attia, M. Hamdy, W. O’Brien, S. Carlucci, Computational optimisation for zero energy buildings design: Interviews results with twenty eight international experts, Proc. BS 2013 13th Conf. Int. Build. Perform. Simul. Assoc. (2013) 3698–3705. [CrossRef]

- S. Arani, Optimizing energy performance of building renovation using traditional and machine learning approaches, PhD thesis, Concordia University, 2020.

- A.D. Russell, G.A. Arlani, Objective functions for optimal building design, Comput. Des. 13 (1981) 327–338. [CrossRef]

- F. Zahra Benaddi, L. Boukhattem, P. Cesar Tabares-Velasco, Multi-objective optimization of building envelope components based on economic, environmental, and thermal comfort criteria, Energy Build. 305 (2024) 113909. [CrossRef]

- N. Delgarm, B. Sajadi, F. Kowsary, S. Delgarm, Multi-objective optimization of the building energy performance: A simulation-based approach by means of particle swarm optimization (PSO), Appl. Energy 170 (2016) 293–303. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Sharif, A. Hammad, Simulation-Based Multi-Objective Optimization of institutional building renovation considering energy consumption, Life-Cycle Cost and Life-Cycle Assessment, J. Build. Eng. 21 (2019) 429–445. [CrossRef]

- F.P. Chantrelle, H. Lahmidi, W. Keilholz, M. El Mankibi, P. Michel, Development of a multicriteria tool for optimizing the renovation of buildings, Appl. Energy 88 (2011) 1386–1394. [CrossRef]

- R. Evins, P. Pointer, R. Vaidyanathan, S. Burgess, A case study exploring regulated energy use in domestic buildings using design-of-experiments and multi-objective optimisation, Build. Environ. 54 (2012) 126–136. [CrossRef]

- Karagiannidis, A., Lagouvardos, K., Kotroni, V., & Galanaki, E. (2023). Analysis of Current and Future Heating and Cooling Degree Days over Greece Using Observations and Regional Climate Model Simulations. Environmental Sciences Proceedings, 26(1), 149. [CrossRef]

- Kreider, J. F., & Rabl, A. (1994). Heating and Cooling of Buildings: Design for Efficiency. McGraw-Hill, New York.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).