Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Food: More than Nutrients

2. Dietary Choices and Sustainability

3. Diet as a Major Factor in Healthier Living

The Nutraceutical Impact

4. Mediterranean Diet

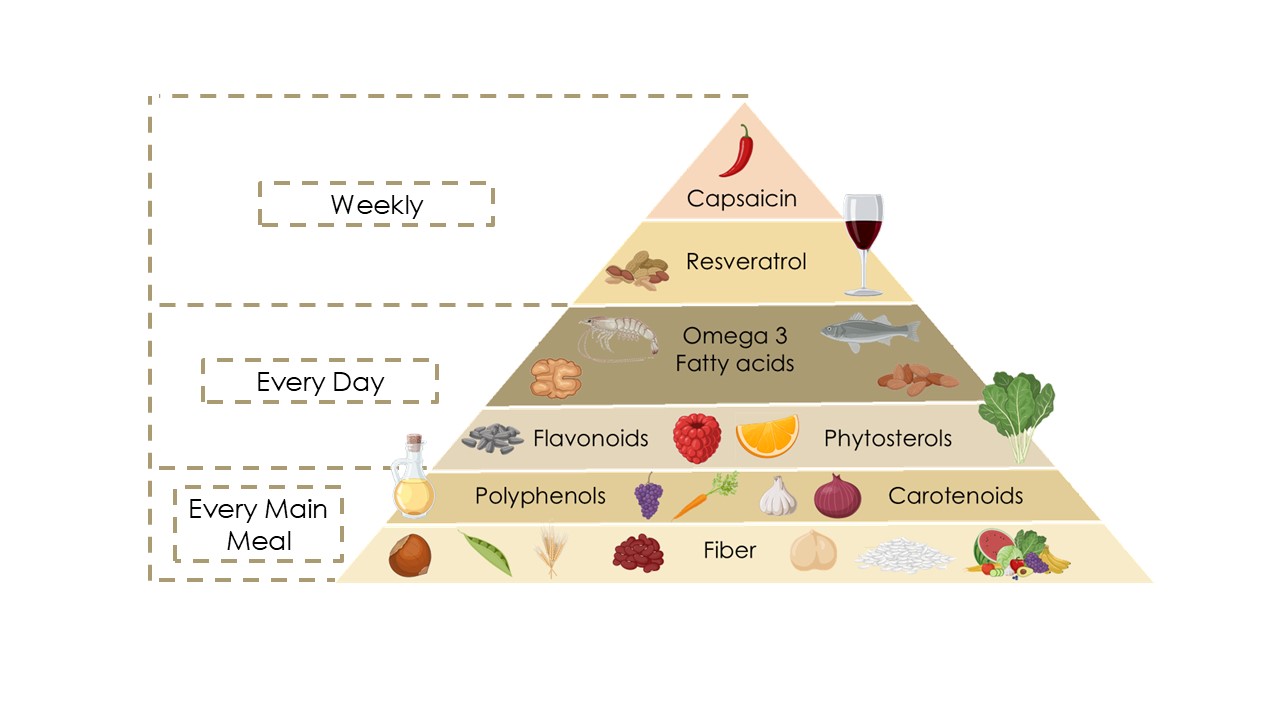

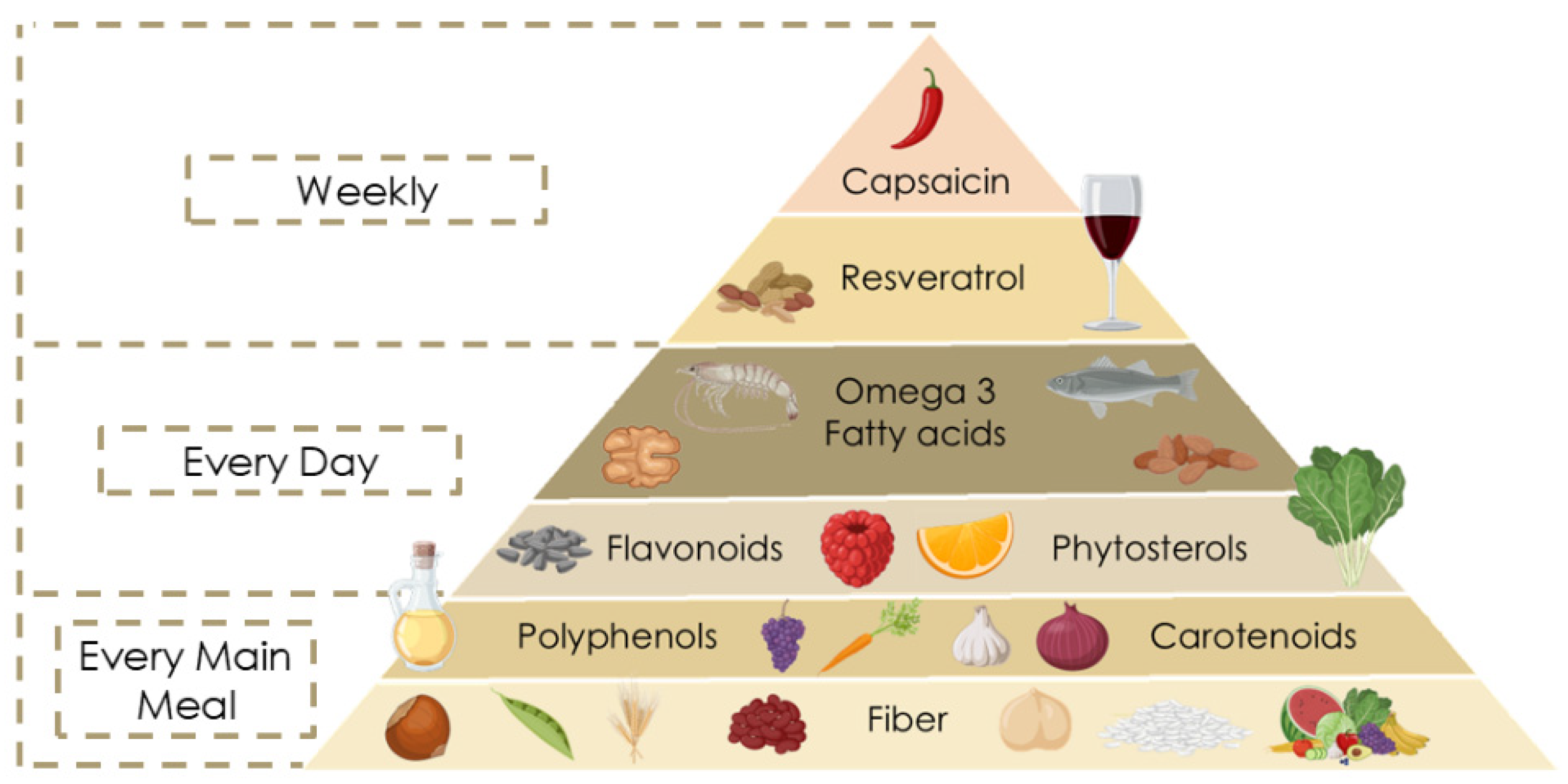

4.1. Mediterranean Diet Pyramid

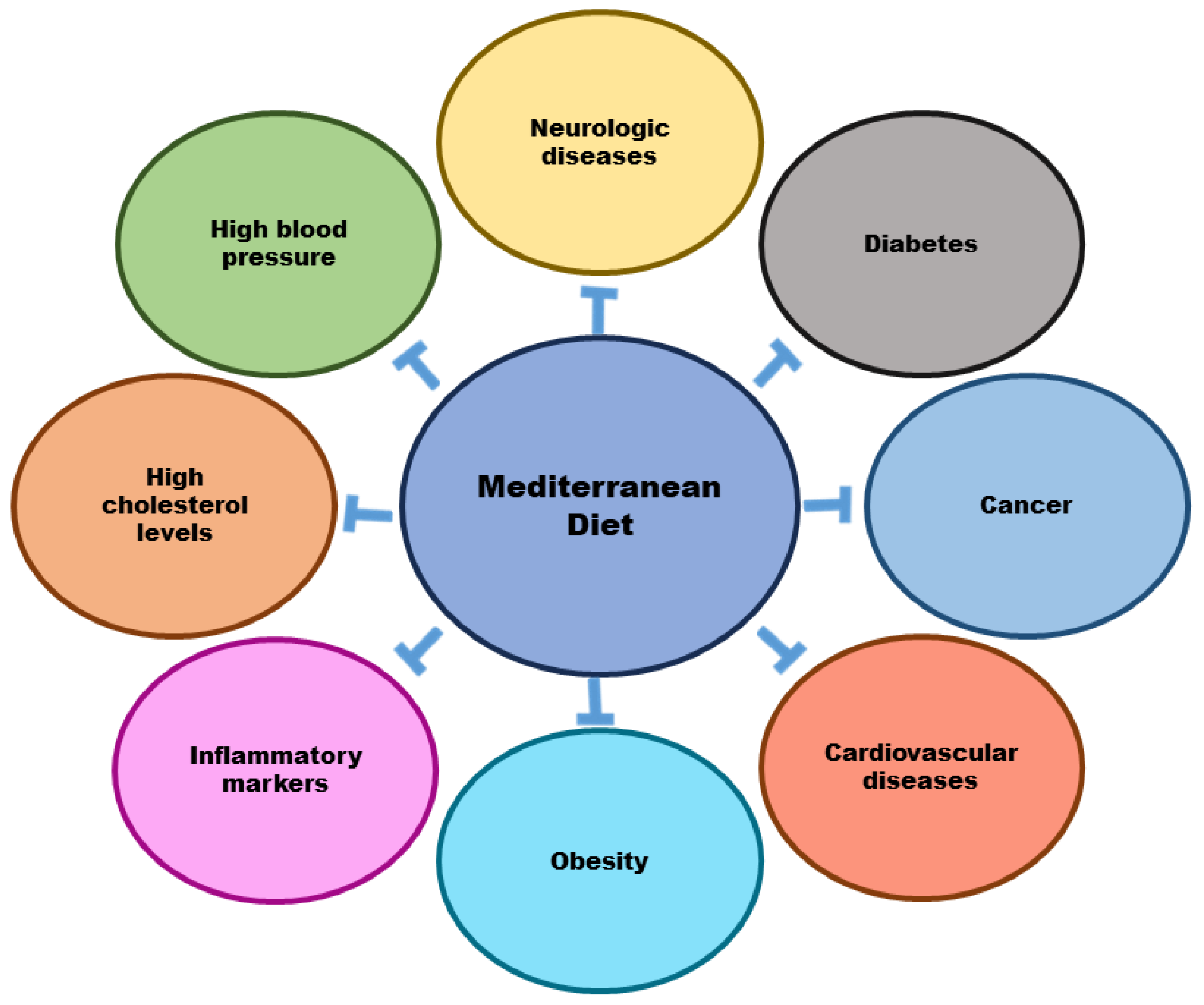

4.2. Mediterranean Diet Health Benefits

4.3. Family of Compounds with Bioactive Potential Associated with the Mediterranean Diet

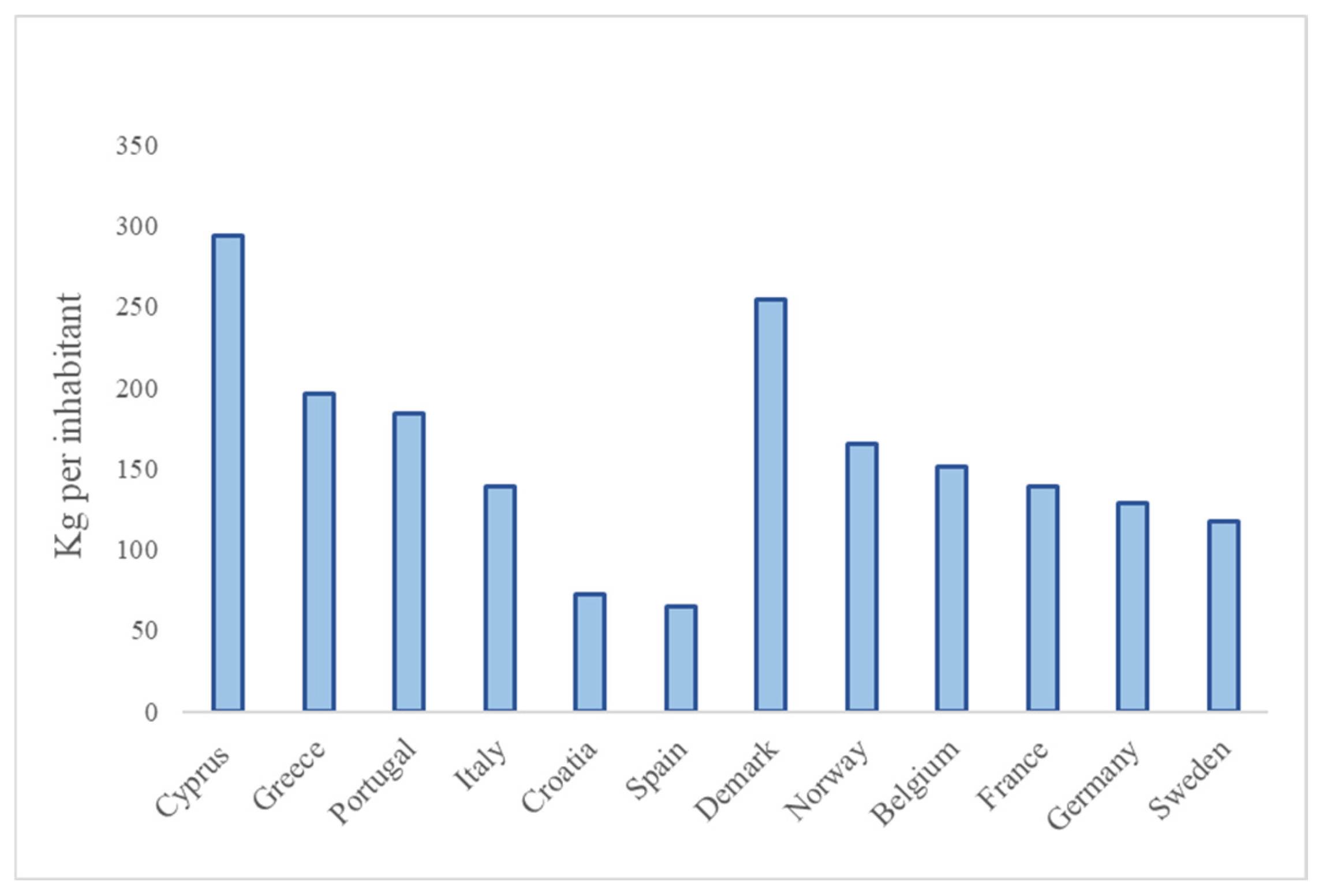

4.4. Environmental Sustainability of the Mediterranean Diet: A Model for Eco-Friendly Nutrition

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MD | Mediterranean Diet |

| NCDs | Non communicable Diseases |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

References

- Andrews, P.; Johnson, R.J. Evolutionary basis for the human diet: Consequences for human health. Journal of Internal Medicine 2020, 287, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tattersall, I. Becoming modern Homo sapiens. Evolution: Education and Outreach 2009, 2, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual models of food choice: Influential factors related to foods, individual differences, and society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symons, M. Simmel’s gastronomic sociology: An overlooked essay. Food and Foodways 1994, 5, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, J.A.; O’Mahony, G.B. Gastronomy: A phenomenon of cultural expressionism and an aesthetic for living. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2001, 20, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Zambrano-Conforme, D.; Carvache Franco, O. Attributes of the service that influence and predict satisfaction in typical gastronomy. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 2021, 24, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Gregory, P.J. Climate change and sustainable food production. Proceedings of the nutrition society 2013, 72, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J. Role of gastronomy and new technologies in shaping healthy diets. In Gastronomy and food science; Academic Press, 2021; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveney, J.; Santich, B. A question of balance: Nutrition, health and gastronomy. Appetite 1997, 28, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, E.K. Nutraceutical-definition and introduction. Aaps Pharmsci 2003, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaicu, P.A.; Untea, A.E.; Varzaru, I.; Saracila, M.; Oancea, A.G. Designing nutrition for health—Incorporating dietary by-products into poultry feeds to create functional foods with insights into health benefits, risks, bioactive compounds, food component functionality and safety regulations. Foods 2023, 12, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.P.; Costa-Camilo, E.; Duarte, I. Advancing health and sustainability: A holistic approach to food production and dietary habits. Foods 2024, 13, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresán, U.; Cvijanovic, I.; Chevance, G. You Can Help Fight Climate Change with Your Food Choices. Frontiers Young Minds 2023, 11, 1004636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; De Witt, A.; Aiking, H. Help the climate, change your diet: A cross-sectional study on how to involve consumers in a transition to a low-carbon society. Appetite 2016, 98, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

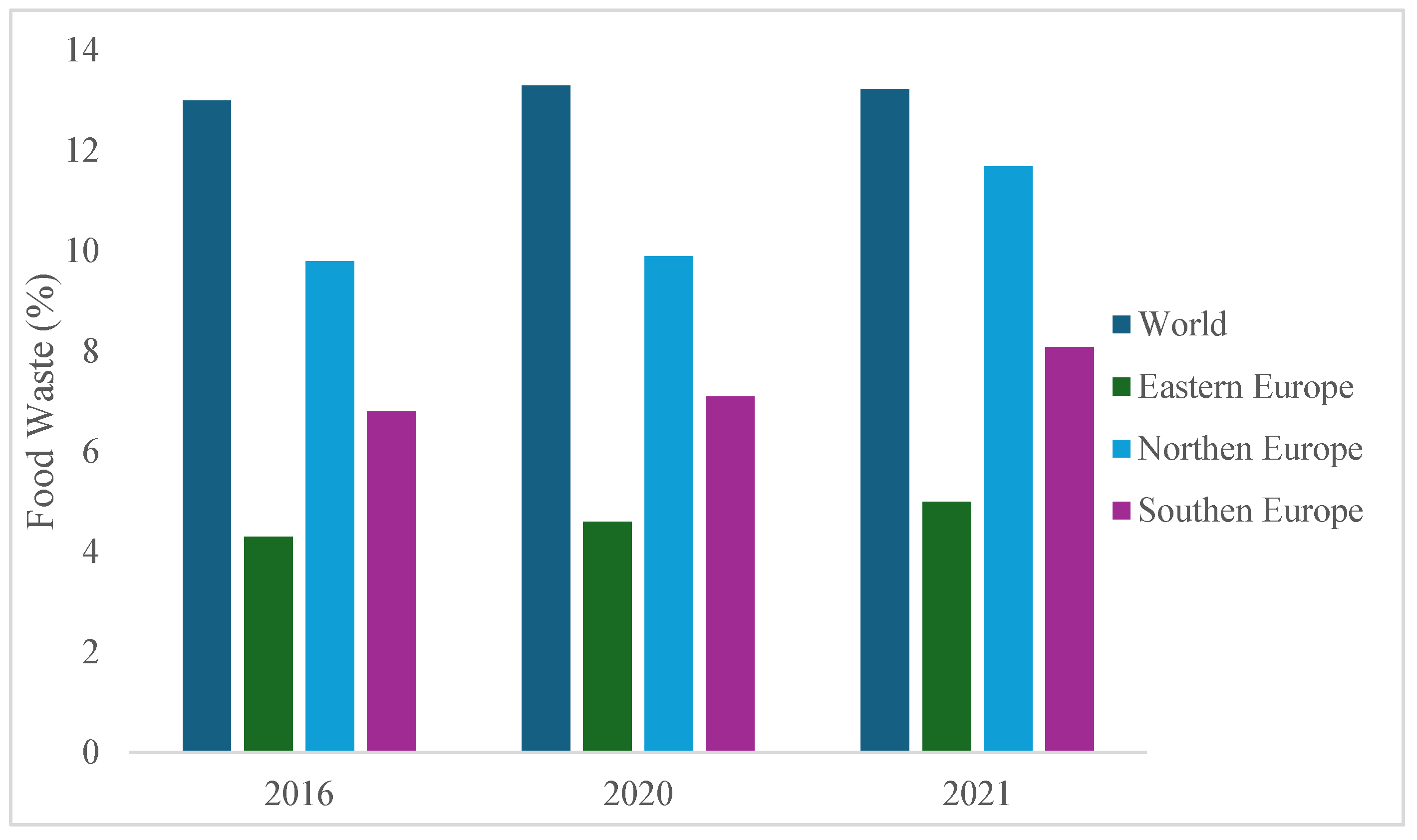

- Eurostat. Food waste by sector (env_wasfw). European Commission. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_wasfw/default/map?lang=en (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Costa-Camilo, E. Setting up the LC-MS/MS approach for plasma proteomics in the DM4You Project. Instituto Superior Técnico. 2024. Available online: https://scholar.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/records/s_aDgpxSd2aeM6GCCGd-nZIDZDu1JIKieaA9.

- Khan, S.; Hanjra, M.A. Footprints of water and energy inputs in food production–Global perspectives. Food policy 2009, 34, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ma, H.; Ozturk, I.; Ulucak, R. Sustainable development and pollution: The effects of CO 2 emission on population growth, food production, economic development, and energy consumption in Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonchyk, M.; Peterson, M.P.; Zhang, L.; Hurynovich, V.; He, Y. Greenhouse gases emissions and global climate change: Examining the influence of CO2, CH4, and N2O. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 173359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, T.L.; Szutu, D.J.; Verfaillie, J.G.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Silver, W.L. Carbon-sink potential of continuous alfalfa agriculture lowered by short-term nitrous oxide emission events. Nature communications 2023, 14, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albou, E.M.; Abdellaoui, M.; Abdaoui, A.; Boughrous, A.A. Agricultural practices and their impact on aquatic ecosystems–a mini-review. Ecological Engineering & Environmental Technology 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizad, S.; Bera, S. The effect of organic farming on water reusability, sustainable ecosystem, and food toxicity. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 71665–71676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jia, N.; Lenzen, M.; Malik, A.; Wei, L.; Jin, Y.; Raubenheimer, D. Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions. Nature food 2022, 3, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterházy, Á.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J. Losses in the grain supply chain: Causes and solutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.; Sánchez, M.V.; Torero, M.; Vos, R. Reducing food loss and waste: Five challenges for policy and research. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K. Sustainable chemistry in adaptive agriculture: A review. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2024, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Zheng, L. Why is it necessary to integrate circular economy practices for agri-food sustainability from a global perspective? Sustainable Development 2025, 33, 600–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.; Kim, H.; Pan, S.Y.; Tseng, P.C.; Lin, Y.P.; Chiang, P.C. Implementation of green chemistry principles in circular economy system towards sustainable development goals: Challenges and perspectives. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 716, 136998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, K.L.; Tonjes, D.J. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggi, S.; Bonomi, S.; Ricciardi, F. Against food waste: CSR for the social and environmental impact through a network-based organizational model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, K.; Ekardt, F.; Sund, L.; Roos, P. Potentials and limitations of subsidies in sustainability governance: The example of agriculture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ju, Z.; Zhou, P.K. A gut dysbiotic microbiota-based hypothesis of human-to-human transmission of non-communicable diseases. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 745, 141030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajat, C.; Stein, E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Preventive medicine reports 2018, 12, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Scheepens, A. Vascular action of polyphenols. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2009, 53, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.H. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Advances in Nutrition 2013, 4, 384S–392S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.-I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. New England journal of medicine 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S. Eating a balanced diet: A healthy life through a balanced diet in the age of longevity. Journal of obesity & metabolic syndrome 2018, 27, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Budreviciute, A.; Damiati, S.; Sabir, D.K.; Onder, K.; Schuller-Goetzburg, P.; Plakys, G.; Katileviciute, A.; Khoja, S.; Kodzius, R. Management and prevention strategies for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors. Frontiers in public health 2020, 8, 574111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Danaei, G.; Riley, L.M.; Paciorek, C.J.; Stevens, G.A.; Gregg, E.W.; Bennett, J.E.; Solomon, B.; Singleton, R.K.; et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: A pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. The lancet 2021, 398, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddy, F.J.; Vanhoutte, P.M.; Feletou, M. Role of potassium in regulating blood flow and blood pressure. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2006, 290, R546–R552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Mahdavi, R.; Vaghef-Mehrabany, E.; Maleki, V.; aramzad, N.; Ebrahimi-Mameghani, M. Potential roles of Citrulline and watermelon extract on metabolic and inflammatory variables in diabetes mellitus, current evidence and future directions: A systematic review. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology 2020, 47, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ried, K.; Frank, O.R.; Stocks, N.P.; Fakler, P.; Sullivan, T. Effect of garlic on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC cardiovascular disorders 2008, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, D.; Necozione, S.; Lippi, C.; Croce, G.; Valeri, L.; Pasqualetti, P.; Desideri, G.; Blumberg, J.B.; Ferri, C. Cocoa reduces blood pressure and insulin resistance and improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypertensives. Hypertension 2005, 46, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.T.; A Bowman, S.; Spence, J.T.; Freedman, M.; King, J. Popular diets: Correlation to health, nutrition, and obesity. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2001, 101, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalbert, A.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Arita, M.; Kroon, P.; Manach, C.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Wishart, D. Databases on food phytochemicals and their health-promoting effects. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2011, 59, 4331–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daliu, P.; Santini, A.; Novellino, E. From pharmaceuticals to nutraceuticals: Bridging disease prevention and management. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology 2019, 12, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, I.; Russo, G.; Curcio, F.; Bulli, G.; Aran, L.; DELLA-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; Bonaduce, D.; et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clinical interventions in aging 2018, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jideani, A.I.; Silungwe, H.; Takalani, T.; Omolola, A.O.; Udeh, H.O.; Anyasi, T.A. Antioxidant-rich natural fruit and vegetable products and human health. International Journal of Food Properties 2021, 24, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (poly) phenolics in human health: Structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Hagen, T.M. Nutritional strategies for healthy cardiovascular aging: From oxidative stress to chronic inflammation. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2007, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C.; Bosco, N.; Bourdet-Sicard, R.; Capuron, L.; Delzenne, N.; Doré, J.; Franceschi, C.; Lehtinen, M.J.; Recker, T.; Salvioli, S.; et al. Health relevance of the modification of low grade inflammation in ageing (inflammageing) and the role of nutrition. Ageing research reviews 2017, 40, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A review of its effects on human health. Foods 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Gordon, G.B. A strategy for cancer prevention: Stimulation of the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2004, 3, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Camilo, E.; Rovisco, B.; Duarte, I.; Pinheiro, C.; Carvalho, G.P. Future-Proof a Mediterranean Soup. In International Conference on Water Energy Food and Sustainability; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, May 2024; pp. 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, P. Breve história do conceito de dieta Mediterrânica numa perspetiva de saúde. Revista Factores de Risco 2014, 20–22. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/10163.

- Hareer, L.W.; Lau, Y.Y.; Mole, F.; Reidlinger, D.P.; O’NEill, H.M.; Mayr, H.L.; Greenwood, H.; Albarqouni, L. The effectiveness of the Mediterranean Diet for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: An umbrella review. Nutrition & Dietetics 2025, 82, 8–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delarue, J. Mediterranean Diet and cardiovascular health: An historical perspective. British Journal of Nutrition 2022, 128, 1335–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. The Mediterranean diet. In Nutritional Health: Strategies for Disease Prevention; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, K.; Bimin, S. Role of Mediterranean diet in prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. Chinese Medical Journal 2014, 127, 3651–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.J.; Mente, A.; Maroleanu, A.; I Cozma, A.; Ha, V.; Kishibe, T.; Uleryk, E.; Budylowski, P.; Schünemann, H.; Beyene, J.; et al. Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Bmj 2015, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, E.A.; McKay, S. The role of specific components of a plant-based diet in management of dyslipidemia and the impact on cardiovascular risk. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, R.G.; Purcell, S.A.; Gold, S.L.; Christiansen, V.; D’Aloisio, L.D.; Raman, M.; Haskey, N. From Evidence to Practice: A Narrative Framework for Integrating the Mediterranean Diet into Inflammatory Bowel Disease Management. Nutrients 2025, 17, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditano-Vázquez, P.; Torres-Peña, J.D.; Galeano-Valle, F.; Pérez-Caballero, A.I.; Demelo-Rodríguez, P.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Katsiki, N.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Alvarez-Sala-Walther, L.A. The fluid aspect of the Mediterranean diet in the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: The role of polyphenol content in moderate consumption of wine and olive oil. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menotti, A.; Puddu, P.E. How the Seven Countries Study contributed to the definition and development of the Mediterranean diet concept: A 50-year journey. Nutrition, metabolism and cardiovascular diseases 2015, 25, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twiss, K. The archaeology of food and social diversity. Journal of archaeological research 2012, 20, 357–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmore, R.D.; Deaux, K.; McLaughlin-Volpe, T. An organizing framework for collective identity: Articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychological bulletin 2004, 130, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Martini, D.; Angelino, D.; Cairella, G.; Campanozzi, A.; Danesi, F.; Dinu, M.; Erba, D.; Iacoviello, L.; Pellegrini, N.; et al. Mediterranean diet: Why a new pyramid? An updated representation of the traditional Mediterranean diet by the Italian Society of Human Nutrition (SINU). Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2025, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naska, A.; Trichopoulou, A. Back to the future: The Mediterranean diet paradigm. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2014, 24, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach-Faig, A.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Reguant, J.; Trichopoulou, A.; Dernini, S.; Medina, F.X.; Battino, M.; Belahsen, R.; Miranda, G.; et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public health nutrition 2011, 14, 2274–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-Cabanas, L.; García-Fernández, E.L.; Estruchm, R.; Bach-Faig, A. Mediterranean diet, the new pyramid and some insights on its cardiovascular preventive effect. Rev Factores Risco 2014, 31, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W. Mediterranean dietary pyramid. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Tomaino, L.; Dernini, S.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Ngo de la Cruz, J.; Bach-Faig, A.; Donini, L.M.; Medina, F.-X.; Belahsen, R.; et al. Updating the mediterranean diet pyramid towards sustainability: Focus on environmental concerns. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17, 8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean diet: A literature review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C.; De Laurentiis, V.; Ghose, A.; Corrado, S.; Sala, S. Grown and thrown: Exploring approaches to estimate food waste in EU countries. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2021, 168, 105426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakırhan, H.; Özkaya, V.; Pehlivan, M. Mediterranean diet is associated with better gastrointestinal health and quality of life, and less nutrient deficiency in children/adolescents with disabilities. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Di Bella, G.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Impact of Mediterranean diet on chronic non-communicable diseases and longevity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H. Protective mechanisms of the Mediterranean diet in obesity and type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2007, 18, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, R.; Sacanella, E.; Estruch, R. The immune protective effect of the Mediterranean diet against chronic low-grade inflammatory diseases. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders) 2014, 14, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean diet: Science and practice. Public health nutrition 2006, 9(1a), 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Covas, M.I.; Fiol, M.; Wärnberg, J.; Arós, F.; Ruíz-Gutiérrez, V.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; et al. Cohort profile: Design and methods of the PREDIMED study. International journal of epidemiology 2012, 41, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriello, A.; Esposito, K.; La Sala, L.; Pujadas, G.; De Nigris, V.; Testa, R.; Bucciarelli, L.; Rondinelli, M.; Genovese, S. The protective effect of the Mediterranean diet on endothelial resistance to GLP-1 in type 2 diabetes: A preliminary report. Cardiovascular diabetology 2014, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; de Gaetano, G.; Moli-Sani Investigators. The Mediterranean diet: The reasons for a success. Thrombosis Research 2012, 129, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.; Masulli, M.; Calabrese, I.; Rivellese, A.A.; Bonora, E.; Signorini, S.; Perriello, G.; Squatrito, S.; Buzzetti, R.; Sartore, G.; et al. IT Study Group. Impact of a Mediterranean dietary pattern and its components on cardiovascular risk factors, glucose control, and body weight in people with type 2 diabetes: A real-life study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Aiello, A.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.; Accardi, G.; Burgos-Ramos, E.; Silva, P. Olive oil components as novel antioxidants in neuroblastoma treatment: Exploring the therapeutic potential of oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol. Nutrients 2024, 16, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.R.; Nabavi, S.F.; Manayi, A.; Daglia, M.; Hajheydari, Z.; Nabavi, S.M. Resveratrol and the mitochondria: From triggering the intrinsic apoptotic pathway to inducing mitochondrial biogenesis, a mechanistic view. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 2016, 1860, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Lin, S.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Liu, P.L.; Chen, J.W. Anti-inflammatory effects of different drugs/agents with antioxidant property on endothelial expression of adhesion molecules. Cardiovascular & Haematological Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Cardiovascular & Hematological Disorders) 2006, 6, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, S.; Dai, H.; Zhang, L. ERK5-regulated RERG expression promotes cancer progression in prostatic carcinoma. Oncology Reports 2019, 41, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanaida, M.; Mykhailenko, O.; Lysiuk, R.; Hudz, N.; Balwierz, R.; Shulhai, A.; Bjørklund, G. Carotenoids for Antiaging: Nutraceutical, Pharmaceutical, and Cosmeceutical Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, T.; Masciangelo, S.; Bicchiega, V.; Bertoli, E.; Ferretti, G. Phytosterols, phytostanols and their esters: From natural to functional foods. Mediterranean Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2011, 4, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Juárez, A.; Pérez-Carrillo, E.; Arredondo-Espinoza, E.U.; Islas, J.F.; Benítez-Chao, D.F.; Escamilla-García, E. Nutraceuticals and their contribution to preventing noncommunicable diseases. Foods 2023, 12, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.; Afonso, C.; Bandarra, N.M. Dietary DHA and health: Cognitive function ageing. Nutrition Research Reviews 2016, 29, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.; Hossain, R.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Islam, M.T.; Atolani, O.; Adeyemi, O.S.; Owolodun, O.A.; Kambizi, L.; Daştan, S.D.; Calina, D.; et al. Natural antioxidants from some fruits, seeds, foods, natural products, and associated health benefits: An update. Food science & nutrition 2023, 11, 1657–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretta, M.D.; Quiroga, J.; López, R.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Burgos, R.A. Participation of short-chain fatty acids and their receptors in gut inflammation and colon cancer. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 662739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthembu, S.X.; Muller, C.J.; Dludla, P.V.; Madoroba, E.; Kappo, A.P.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E. Rooibos flavonoids, aspalathin, isoorientin, and orientin ameliorate antimycin A-induced mitochondrial dysfunction by improving mitochondrial bioenergetics in cultured skeletal muscle cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L.M.; Serra-Majem, L.; Bulló, M.; Gil, Á. The Mediterranean diet: Culture, health and science. British Journal of Nutrition 2016, 113(S2), S6–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dernini, S.; Berry, E.M. Mediterranean diet: From a healthy diet to a sustainable dietary pattern. Frontiers in Nutrition 2015, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Joint Research Centre. Environmental impacts of food consumption and dietary patterns; Publications Office of the European Union, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food wastage footprint: Full-cost accounting; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3991e/i3991e.pdf.

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Renzulli, P.A.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. The role of life cycle assessment in supporting sustainable agri-food systems: A review of the challenges. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 140, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Almendros, S.; Obrador, B.; Bach-Faig, A.; Serra-Majem, L. Environmental footprints of Mediterranean versus Western dietary patterns: Beyond the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Environmental Health 2013, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Vasilopoulou, E.; Georga, K.; Soukara, S.; Dilis, V. Sustainable food consumption: A Mediterranean diet example. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2014, 68, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, C.; Haynes, R.; Oreszczyn, T.; Garrod, G. Seasonal diets: A sustainable approach to food systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 260, 121041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dooren, C.; Marinussen, M.; Blonk, H.; Aiking, H.; Vellinga, P. Exploring dietary guidelines based on ecological and nutritional values: A comparison of six dietary patterns. Food Policy 2014, 44, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diet | Acronym | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension | DASH | A dietary pattern designed to lower blood pressure, emphasising the intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products, while limiting sodium, saturated fats, and added sugars. |

| Flexitarian Diet | FD | A predominantly plant-based diet that permits occasional consumption of meat and fish. It prioritises vegetables, legumes, and whole foods, promoting cardiovascular health and weight management. |

| Mediterranean Diet | MD | Based on traditional eating habits of Mediterranean countries, this diet is rich in olive oil, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fish. It is associated with reduced risk of chronic diseases. |

| Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes | TLC | A dietary strategy aimed at reducing LDL cholesterol. It includes foods high in soluble fibre, plant sterols, and unsaturated fats, and is often combined with regular physical activity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).