Introduction

Wildlife is now considered an important source and reservoir of a wide range of parasites around the globe, which is also a great threat to wildlife itself and human populations. Parasite flow across wildlife may occur through a variety of routes, one of which is an arthropod vector (Polley, 2005). Anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and theileriosis are a group of tick-borne diseases caused by protozoan parasites and have a great impact on tropical and subtropical ungulates such as hog deer (Axis porcinus) and chinkara (Gazella bennettii) in Pakistan (Demessie and Derso 2015). These parasites have an economic impact on both livestock and wildlife. The infected sporozoite stage of Anaplasma, Babesia, and Theileria is transmitted through the saliva of different tick species like Rhipicephalus and Boophilus as they feed on a host. Anaplasma targets WBCs, Babesia primarily targets RBCs, while Theileria successively targets WBCs and RBCs. (Ibrahim & Sander, 2022).

Overall, in blood-borne diseases, clinical signs and symptoms observed are fever, anaemia, anorexia, constipation, dyspnoea, dehydration, weight loss, poor milk supply, diminished performance, jaundice, sunken eyes, rapid abdominal respiration, severe lung involvement, emaciation, lacrimation, corneal opacity, and frothy nasal discharge (Mattioli et al. 1994); (Buriro et al. 1994); (Naz et al. 2012).

Accurate detection of these parasites is essential for effective disease management, as it can be difficult to differentiate between them when making a diagnosis. Misdiagnosis of disease leads to morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic tests for blood parasites, such as Microscopy, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunofluorescence antibody assay (IFAT), and RDTs (Rapid diagnostic test), give false negative results, and no intra-species differentiation is seen (Berzosa et al. 2018). To identify pathogens in the early phase of disease, a new diagnostic test based on DNA is essential for rapid diagnosis and proper treatment.

Multiplex PCR detects multiple targets in a single reaction well using a distinct pair of primers for each target. It is time and cost effective, especially for detecting mixed infections capable of detecting multiple parasites at various stages of infection at the same time (Edwards and Gibbs 1994). Successful diagnosis of various bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic infections using multiplex PCR has been reported (Markoulatos et al. 2002).

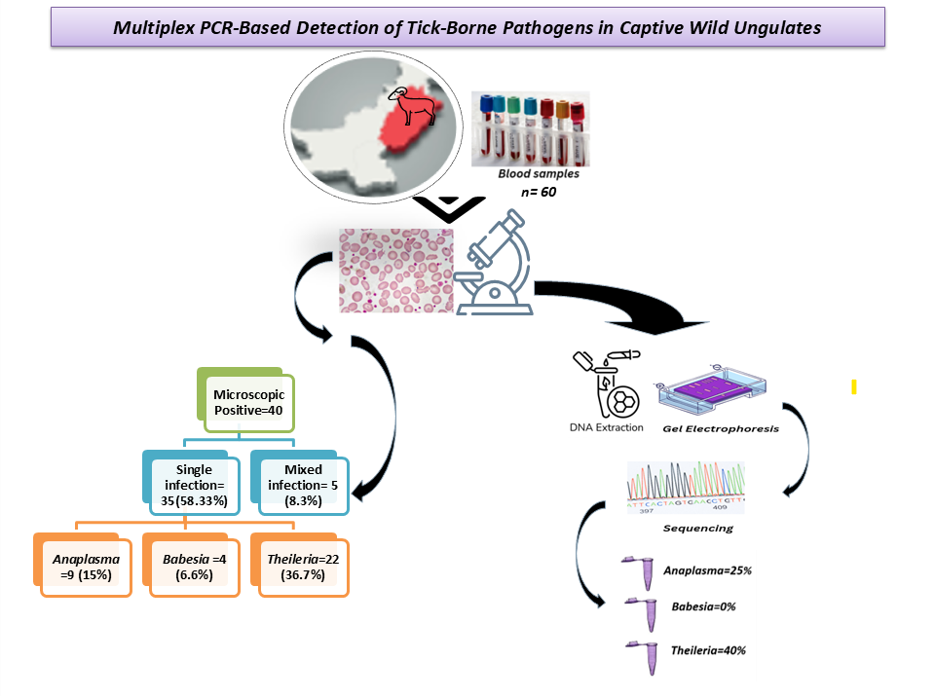

In the current study, we optimized a multiplex PCR assay targeting the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of Anaplasma, Babesia, and Theileria for their detection, as these parasites invade the circulatory system of a host and cause mortality by damaging blood cells. Accurate diagnosis and timely treatment of such diseases, especially in endangered species, is crucial. In wildlife, obtaining samples is a complicated task, particularly in cases of mixed infections. Conducting individual disease tests can lead to a loss of valuable samples and time. This study aims to develop an assay that would be useful for the timely diagnosis of co-infections in a single reaction, which will be very useful in wild animal medicine, where repeated sampling is a major issue.

Materials and Methods

Blood Sample Collection

A total of 60 blood samples were collected from the Chinkara and Hog deer being kept at various public and private wildlife parks and zoos in 14 Districts of Punjab, Pakistan, that displayed one or more typical clinical indications of anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and theileriosis were taken by using common minimally invasive capture methods. The animals were not specifically captured for research purposes; rather, samples were collected opportunistically during routine captures conducted for medical examinations and other scheduled procedures. Positive blood samples from captive animals comprising Chinkara and Hog Deer were further processed. Blood samples were taken from the jugular vein in EDTA vials for the best preservation of cellular components and the morphology of blood cells. Samples were collected by qualified veterinarians as per the standard sample collection method without any undue stress to animals. The blood samples were stored at 20°C until DNA extraction.

Microscopy

Thin blood smears were made from all samples and stained with 10% Giemsa stain after fixation with methanol (Absolute) for 30 seconds. Samples were initially screened based on microscopic examination under a 100X oil immersion lens. The specimens were stated to be positive upon the presence of inclusion bodies resembling hemoparasites i.e., Anaplasma, Babesia and Theileria.

Primer Designing for rDNA Intergenic Spacer Region

For Deoxyribonucleic acid extraction of blood samples phenol-chloroform extraction protocol was used. The blood was lysed with lysis buffer to get white pellets, which was further treated with phenol chloroform isoamyl alcohol to get nucleotides, specifically DNA. The extracted total DNA was visualized by gel electrophoresis using Bio-Helix Novel juice as DNA staining reagent. DNA fragments of different lengths were seen. A Nano-Drop 2000/2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to check the concentration and purity of extracted DNA.

The genus-based primers were designed by aligning sequences of 16S rRNA of

Anaplasma species and 18S rRNA of different

Babesia and

Theileria species at Mega3 software. Various

Theileria Species,

T. buffeli,

T. sergenti,

T. cervi,

T. annulata and

T. parva with accession number of sequences AB000272.1, AB016074.1, AY735122.1, KF429795.1, L02366.1 respectively, those of

Babesia Species

B. ovata,

B. ovis,

B. divergens,

B. odocoilei, and

B. gibosoni with accession number of sequences XR_0037519 73.1, AY260178.1, U07885.1, U16369.2, OQ727056.1, respectively and those of

Anaplasma species,

A. ovis,

A. Phagocytophilum,

A. bovis,

A. Centrale and

A. Playts with accession number of sequences AY262124.1, AB196721.1, AB211163.1, AB211164.21, EU439943.1, respectively were retrieved from NCBI. These primers were further checked by Primer Blast for their specificity for each parasite. Primer sequences and their amplicon sizes are shown in

Table 1. The specificity of primers was bioinformatically aligned with databases in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

PCR Amplification

The PCR assay was standardised using extracted genomic DNA obtained from samples that were tested as a positive control for each parasite by sequencing of monoplex PCR amplicons. PCR primer sets were validated separately to determine their specificity. PCR was optimized to ensure appropriate amplification. The multiplex PCR assay was developed using these newly designed primers in consideration of the size of the PCR product and annealing temperature. The final 35 µl PCR mixture comprised of 5 µl of DNA extract from each positive sample, 2µl of forward and reverse primer (10 pm/ml) from each of the Anaplasma, Babesia and Theileria, 1 µl Taq DNA Polymerase, 1.5 µl MgSO4, 2.5 µl buffer and 3 µl nuclease free water. Amplification was carried out using the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min followed by 10 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 45 s at 65°C (Decreasing 1°C per cycle), at 72°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 45s at 55°C, at 72°C for 1 min and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Samples were held at 4°C before analysis. Each reaction product was visualized using a UV trans illuminator after staining with ethidium bromide.

Sensitivity and Specificity

The sensitivity of the multiplex primer assays (Ana_F/Ana_R, Bab_F/Bab_R, and Thl_F/Thl_R) was assessed by employing serial dilutions of DNA templates (1×102 – 6×102 ng) with strains utilized as positive controls. Specificity was assessed by sequencing.

Results

Microscopy

Microscopy of 60 samples was performed, out of which 40 showed a positive result for parasitic presence. Single infection was observed in 35 (58.33%) samples, including 9 (15%) with Anaplasma, 4 (6.6%) with Babesia, and 22 (36.7%) with Theileria. While 5 (8.3%) samples showed mixed infection, i.e., positive for more than one parasite at a time in a single sample.

Multiplex PCR (mPCR) Standardization

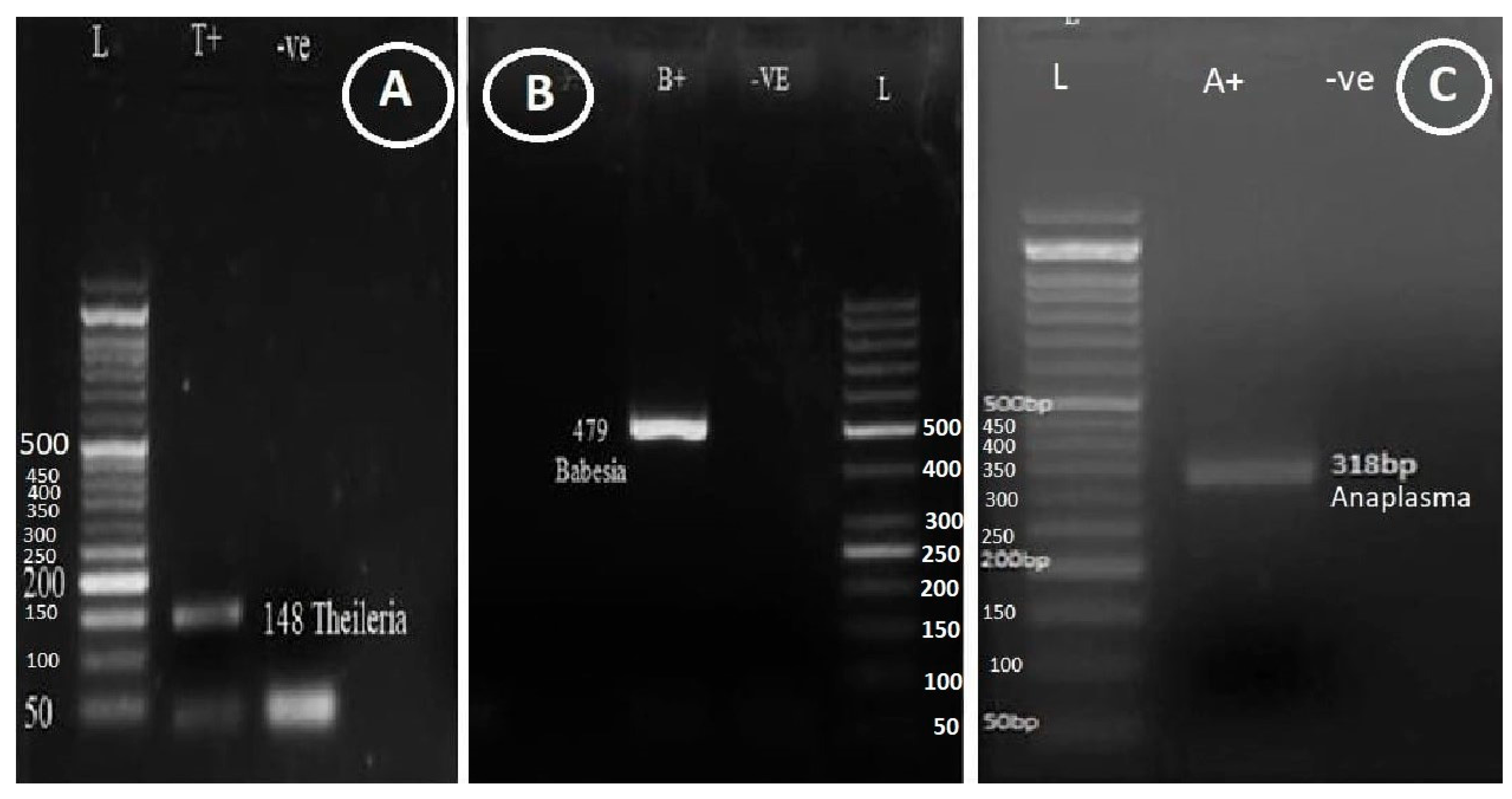

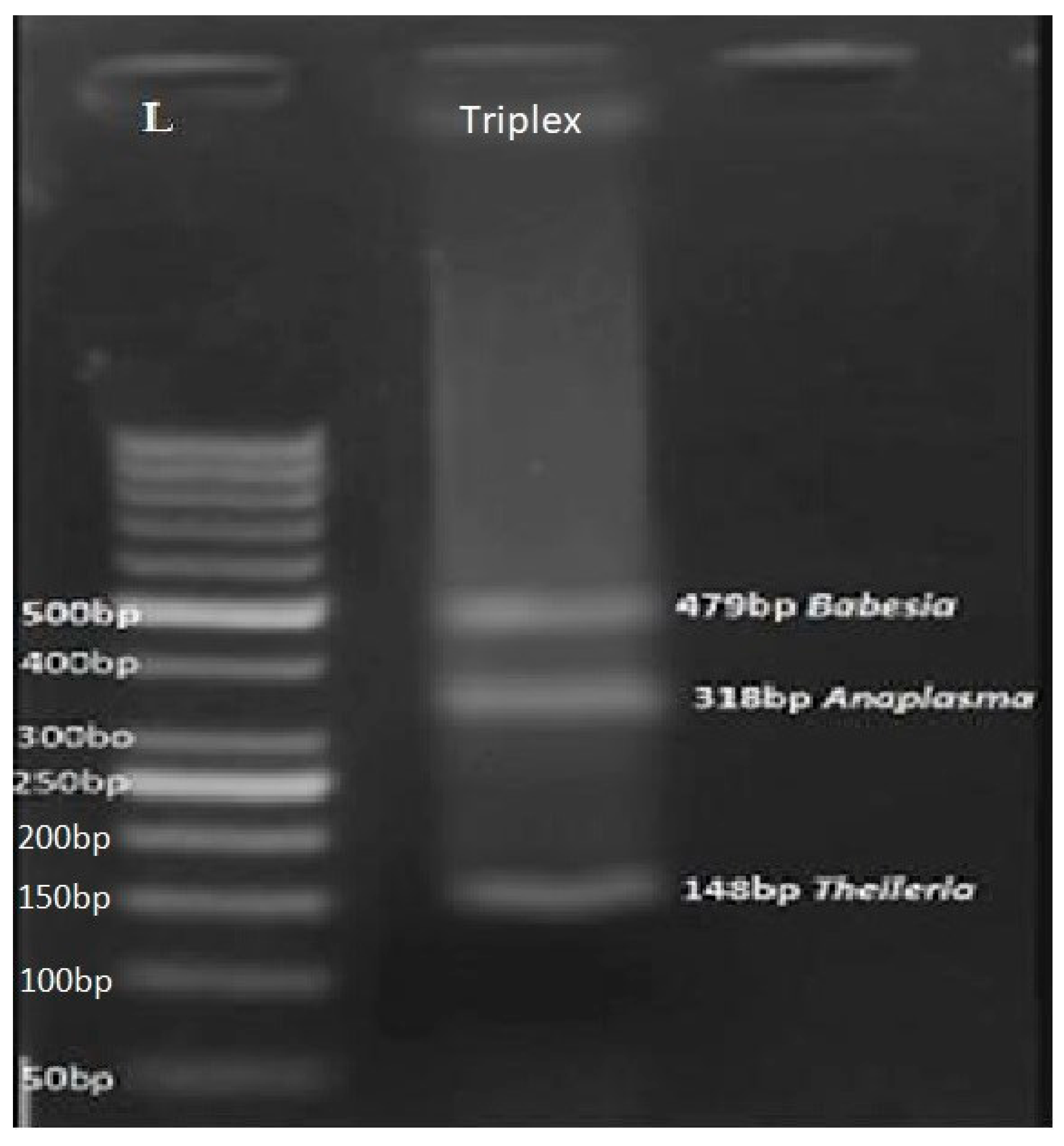

The multiplex PCR (mPCR) assay was optimized using genomic DNA extracted from confirmed positive blood samples. These positive samples were validated through sequencing of monoplex PCR amplicons, each corresponding to a specific band length characteristic of the target protozoa. After analysing the results of monoplex PCR assay, duplex and triplex PCR (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) setups were created by combining specific oligonucleotide sets in different ways, effectively amplifying all relevant markers.

Sensitivity

The mPCR results indicated a sensitivity level of 3×102 ng, establishing the method as sensitive for detecting DNA of Anaplasma, Babesia, and Theileria in all multiplex combinations. Every primer pair utilized in triplex PCR assays was designed to target a specific gene, and their distinct sizes were differentiated through gel electrophoresis for each of the three infectious pathogens.

Validation of Primer Specificity by Sequencing

Sequencing was done on representative positive Controls. Using BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) and MEGA (version 5.05), the acquired sequences were compared to sequences already present in the GenBank database, validating the specificity of the designed primers.

The sequences from all three positive parasite controls were submitted to GenBank, and accession numbers were obtained as OR610413 (Anaplasma), OR512079 (Babesia), and PP455035 (Theileria).

Discussion

The prevalence and importance of tick-borne diseases have been examined worldwide (de la Fuente et al. 2023, Han et al. 2009, Ahmad et al. 2008). Changes in climate and a reduction in environmental diversity have led to an increase in tick-borne disease infections (Seong et al. 2015, Dantas-Torres F. 2015). Hemoprotozoan species such as Anaplasma, Babesia, and Theileria pose significant risks to the health of animals, which include both livestock and wildlife, as well as humans (Maharana et al. 2016). For example, some research indicates that infection rates of Babesia and/or Theileria were found to be 89.7% (156 out of 174) in roe deer in Spain (Remesar et al. 2019), 58.3% in brown brocket deer (Mazama gouazoubira) and marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) in Brazil (Da Silveira et al. 2011), and 35.3% in sika deer (Cervus nippon) in China (Liu et al. 2016). Likewise, Theileria is also notably prevalent in various wild and domestic animals, with studies revealing an infection rate of 4.7% in wild boars, 22.2% in Alpine chamois, and 1.0% in red foxes in Italy (Zanet et al. 2014); 80.0% in cattle, 93.8% in sheep, and 1.9% (5 out of 265) in goats, with a total of 235 out of 525 (44.8%) ruminants testing positive for Theileria in Ethiopia (Gebrekidan et al. 2013); and 6.2% (82 out of 1329) in dogs in South Africa (Matjila et al. 2008). In Korea, as in other nations, ticks are widespread. Numerous studies on tick-borne diseases have been undertaken involving cattle, dogs, and horses (Seong et al. 2015). The infection rates were 1.2% (9 out of 737) in cattle (Kwak et al. 2020), 3.1% (16 out of 510) in dogs (Seo et al. 2020), and 0.9% (2 out of 224) in horses (Seo et al. 2013).

Economic losses have been seen due to high morbidity and mortality rates in small ungulates. This is the first study designed for the molecular detection of three important hemoprotozoan in wild ungulates kept at different wildlife parks of Punjab and comparison of molecular diagnosis with typical microscopy. Multiplex PCR assay was developed focusing on ITS region of Anaplasma, Babesia and Theileria to detect these parasites simultaneously in a single reaction tube. Detection of these parasites is not only crucial for protecting wildlife but also provides epidemiological links and prevalence rates of parasites.

High prevalence rate of Theileria infection shows multiple/repeated exposure to the infection throughout an animal’s whole life. In northwest Poland, 90% of red deer were found positive for theileria (Sawczuk et al. 2008) and also in Korean water deer, Theileria found to be the highly infectious pathogen ( Seong et al. 2015). Current studies show Theileria is more prevalent compared to Anaplasma and Babesia. In this study, the prevalence of Anaplasma spp. as provided by blood smear microscopy is 27.5% which is in accordance with the studies on prevalence of Anaplasma spp. in buffalos and cattle in Pakistan (Buriro et al. 1994; Rajput et al. 2005). Multiplex PCR assay provided 30% Anaplasma positive samples. Molecular detection-based studies have also provided prevalence rates of Anaplasma spp. 32% and 33% in Asia (Kordick et al. 1999; Motoi et al. 2001).

This analysis suggests that deer are not exposed to Babesia as it is not detected even in one out of forty blood samples. It might be due to the small number of samples. In Spain, nearly 90% of roe deer were found to carry either Babesia or Theileria piroplasm, with Theileria spp. showing a higher prevalence of 60.9% compared to Babesia spp. at 19.0%. In 17.3% of positive samples, the specific species could not be identified (Remesar et al. 2019). In a Turkish study on distinct horse sub-populations, 18.50% of samples tested positive for Babesia and Theileria infections using cELISA. T. equi had a significantly higher prevalence (16.21%) compared to Babesia (0.83%) among the examined blood samples. (Sevinc et al. 2008).The trees generated propose that Babesia and Theileria are closely related, originating from a paraphyletic group (Allsopp et al. 1994). The intimate phylogenetic affinity between Theileria and Babesia (Aktas et al. 2002) renders their differentiation via microscopy a formidable task due to this there is difference between microscopy and PCR results in present study. In Kouhdasht, Lorestan Province, PCR testing targeting the 18s-rRNA gene indicated a 4.7% infection rate of B. ovis in sheep and goats, while microscopic examination revealed a significantly higher 12.2% rate for Babesia, attributed to the microscope's inability to distinguish between Babesia and Theileria (Naderi et al. 2017).

The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region is a crucial component of the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene complex, and it plays a significant role in molecular biology, particularly in the fields of genetics, genomics, and phylogenetic Analysis. They have a high degree of variability between species and are used to identify species. ITS2 is a vital marker in molecular systematics and serves in species barcoding and DNA array technologies (Engelmann et al. 2009). It can differentiate closely related species, so it is useful in detecting co-infection in single host (Blouin 2002; Li and Yang 2008). It is a key challenge to find conserved regions and design primers targeting all the species.

Multiplex PCR is the co-amplification of multiple targets, so it depends upon the compatibility of primers used, particularly the Tm adjusted to anneal the specific targets at the same time (Exner 2012). All the primer sets are designed to target the amplicon of distinct size, so that fragments of desired length can be seen easily by agarose gel. This technique's genetic markers enable discrimination between closely related species or strains (Mahoney and Chernesky 1995). It has now been recognized as a rapid and reliable detection tool in clinical and research laboratories because considerable time, effort and cost can be saved by amplifying multiple targets in a single reaction. Successful assay development requires step by step optimization and multiple attempts to adjust concentrations of primers and nucleic acids (Markoulatos et al. 2002). Multiplex PCR assay is developed to overcome the problem of false positive results obtained by microscopy which lead to treatment and cause parasites drug-resistance polymorphism (Cui et al. 2015).

This study can be applied to large sample size to small ungulates to better understand the prevalence of the infections. These infections not only affect the health of animals but also affect the food products harnessed from livestock. This will conserve important wildlife and livestock that are important parts of the economy of our country. Epidemiological studies regarding infections and preventive measures to control the spread of infections will be developed.

Conclusions

This study provided prevalence rates of various parasites Anaplasma (25%), Babesia (0%) and Theileria (40%) by mPCR. Novel mPCR assay development will contribute a significant advancement in veterinary diagnostics. Future studies may expand its application in diverse ecological settings, further aiding in the prevention and control of vector-borne diseases. Overall, this research will help in addressing emerging health challenges in wildlife populations.

Recommendations

It is recommended that multiplex PCR should be used to detect various infections in a single run to save time, and money. Large scale epidemiological study is the need of the hour to protect wildlife.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Visualization, M.A, and M.H.S, M.I , S.Y.S, O.C.A ; Project administration and supervision, M.A, M.H.S, W.S, K.A.; Investigation, N.I, B.A, M.Y.Z, R.L, W.S, Methodology and Validation, N.I, B.A, K.A, R.L, M.A, M.H.S, S.Y.S, O.C.A, Data curation, W.S. M.Y.Z, S.S, M.I.; Resources, Formal analysis, and software M.A, M.H.S, M.J, W.S, R.L, M.I. S.S, M.Y.Z.; Writing- original draft, M.A .; Writing- review and editing, S.Y.S, O.C.A,S.S.

Funding

The research was entirely self-financed; no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors was received.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank the veterinary officers and allied veterinary staff of Wildlife and Parks Punjab, Pakistan and other private zoos for their tremendous cooperation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies: It is declared with honesty that no generative AI and AI-assisted technologies have been used in write up process. The whole manuscript was self-written manually.

References

- Ahmed, J.S.; Glass E.J., Salih D.A., Seitzer U. Innate immunity to tropical theileriosis. Innate Immun. 2008; 14:5–12. [CrossRef]

- Aktas, M., Dumanli, N., Cetinkaya, B., Cakmak, A., 2002. Field evaluation of PCR in detecting Theileria annulata infection in cattle in eastern Turkey. Vet. Rec., 150(17): 548-549.

- Allsopp. M., Cavalier-Smith, T., DeWaal, D., Allsopp, B., 1994. Phylogeny and evolution of the piroplasms. Parasitol., 108(2): 147-152.

- Berzosa, P., DeLucio, A., Romay-Barja, M., Herrador, Z., González, V., García, L., Fernández-Martínez, A., Santana-Morales, M., Ncogo, P., Valladares, B., Riloha, M., 2018. Comparison of three diagnostic methods (microscopy, RDT, and PCR) for the detection of malaria parasites in representative samples from Equatorial Guinea. Malar. J., 17: 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Blouin, M.S., 2002. Molecular prospecting for cryptic species of nematodes: mitochondrial DNA versus internal transcribed spacer. Int. J. Parasitol., 32(5): 527-531. [CrossRef]

- Buriro, S., Phulan, M., Arijo, A., Memon, A., 1994. Incidence of some hemo-protozoans in Bos indicus and Bubalis bubalis in Hyderabad. Pak. Vet. J. 14(1): 28-29.

- Cui, L., Mharakurwa, S., Ndiaye, D., Rathod, P.K., Rosenthal, P.J., 2015. Antimalarial drug resistance: literature review and activities and findings of the ICEMR network. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 93(3): 57. [CrossRef]

- Da Silveira J.A., Rabelo E.M., Ribeiro M.F. Detection of Theileria and Babesia in brown brocket deer (Mazama gouazoubira) and marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;177:61–66. [CrossRef]

- Dantas-Torres F. Climate change, biodiversity, ticks and tick-borne diseases: The butterfly effect. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2015 Aug 28;4(3):452-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de la Fuente J, Estrada-Peña A, Rafael M, Almazán C, Bermúdez S, Abdelbaset AE, Kasaija PD, Kabi F, Akande FA, Ajagbe DO, Bamgbose T, Ghosh S, Palavesam A, Hamid PH, Oskam CL, Egan SL, Duarte-Barbosa A, Hekimoğlu O, Szabó MPJ, Labruna MB, Dahal A. Perception of Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases Worldwide. Pathogens. 2023 Oct 19;12(10):1258. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Demessie, Y., Derso, S., 2015. Tick borne hemoparasitic diseases of ruminants: A review. Adv. Biol. Res., 9(4): 210-224.

- Edwards, M.C., Gibbs, R.A., 1994. Multiplex PCR: advantages, development, and applications. Genome Res., 3(4): S65-S75. [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, J.C., Rahmann, S., Wolf, M., Schultz, J., Fritzilas, E., Kneitz, S., Dandekar, T., Müller, T., 2009. Modelling cross-hybridization on phylogenetic DNA microarrays increases the detection power of closely related species. Mol. Ecol. Res., 9(1): 83-93. [CrossRef]

- Exner, M.M., 2012. Multiplex molecular reactions: design and troubleshooting. Clin. Microbiol. Newsletter, 34(8): 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Gebrekidan H., Hailu A., Kassahun A., Rohoušová I., Maia C., Talmi-Frank D., Warburg A., Baneth G. Theileria infection in domestic ruminants in northern Ethiopia. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;200:31–38. [CrossRef]

- Han J.I., Jang H.J., Lee S.J., Na K.J. High prevalence of Theileria sp. in wild Chinese water deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) in South Korea. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;164:311–314. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.M., Sander, V.A., 2022. Apicomplexa Epidemiology, Control, Vaccines and Their Role in Host-Pathogen Interaction. Front. Vet. Sci., 9: 885181. [CrossRef]

- Kordick, S.K., Breitschwerdt, E., Hegarty, B., Southwick, K., Colitz, C., Hancock, S., Bradley, J., Rumbough, R., Mcpherson, J., MacCormack. J., 1999. Coinfection with multiple tick-borne pathogens in a Walker Hound kennel in North Carolina. J. Clin. Microbiol., 37(8): 2631-2638. [CrossRef]

- Kwak D., Seo M.G. Genetic diversity of bovine hemoprotozoa in South Korea. Pathogens. 2020;9:768. [CrossRef]

- Liu J., Yang J., Guan G., Liu A., Wang B., Luo J., Yin H. Molecular detection and identification of piroplasms in sika deer (Cervus nippon) from Jilin Province, China. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9:156. [CrossRef]

- Maharana BR, Tewari AK, Saravanan BC, Sudhakar NR. Important hemoprotozoan diseases of livestock: Challenges in current diagnostics and therapeutics: An update. Vet World. 2016 May;9(5):487-95. Epub 2016. 20 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahoney, J., Chernesky, M.A., 1995. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Molecular methods for viral detection. Academic Press, Inc., New York, NY. 219-237.

- Mans B.J., Pienaar R., Latif A.A. A review of Theileria diagnostics and epidemiology. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2015;4:104–118. [CrossRef]

- Markoulatos, P., Siafakas, N., Moncany, M., 2002. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction: a practical approach. J. Clin. Lab. Anal., 16(1): 47-51. [CrossRef]

- Matjila P.T., Leisewitz A.L., Oosthuizen M.C., Jongejan F., Penzhorn B.L. Detection of a Theileria species in dogs in South Africa. Vet. Parasitol. 2008;157:34–40. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, R., Zinsstag, J., Pfister, K., 1994. Frequency of trypanosomiasis and gastrointestinal parasites in draught donkeys in The Gambia in relation to animal husbandry. Trop. Anim. Health Pro., 26(2): 102-108. [CrossRef]

- Motoi, Y., Satoh, H., Inokuma, H., Kiyuuna, T., Muramatsu, Y., Ueno, H., 2001. First detection of Ehrlichia platys in dogs and ticks in Okinawa, Japan. Microbiol. Parasitol., 45(1): 89-91.

- Naderi, A., Nayebzadeh, H., Gholami. S., 2017. Detection of Babesia infection among human, goats and sheep using microscopic and molecular methods in the city of Kuhdasht in Lorestan Province, West of Iran. J. Parasit. Dis., 41: 837-842. [CrossRef]

- Naz, S., Maqbool, A., Ahmed, S., Ashraf, K., Ahmed, N., Saeed, K., Latif, M., Iqbal, J., Ali, Z., Shafi, K., 2012. Prevalence of theileriosis in small ruminants in Lahore-Pakistan. J. Vet. Anim. Sci., 2: 16-20.

- Paul, B., Bello, A., Ngari, O., Mana, H., Gadzama, M., Abba, A., Malgwi, K., Balami, S., Dauda, J., Abdullahi, A., 2016. Risk factors of hemoparasites and some haematological parameters of slaughtered trade cattle in Maiduguri, Nigeria. J. Vet. Med. Anim. Health, 8(8): 83-88. [CrossRef]

- Polley, L., 2005. Navigating parasite webs and parasite flow: emerging and re-emerging parasitic zoonoses of wildlife origin. Int. J. Parasitol., 35(11-12): 1279-1294. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, Z., Hu, S.H., Arijo, A., Habib, M., Khalid, M., 2005. Comparative study of Anaplasma parasites in tick carrying buffaloes and cattle. J. Zhejiang Uni. Sci. 6(11): 1057-1062. [CrossRef]

- Remesar S., Díaz P., Prieto A., Markina F., Díaz Cao J.M., López-Lorenzo G., Fernández G., López C.M., Panadero R., Díez-Baños P., et al. Prevalence and distribution of Babesia and Theileria species in roe deer from Spain. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019;9:195–201. [CrossRef]

- Remesar, S., Díaz, P., Prieto, A., Markina, F., Cao, J.M.D., López-Lorenzo, G., Fernández, G., López, C.M., Panadero, R., Díez-Baños, P., 2019. Prevalence and distribution of Babesia and Theileria species in roe deer from Spain. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl., 9: 195-201. [CrossRef]

- Sawczuk, M., Maciejewska, A., Skotarczak, B., 2008. Identification and molecular characterization of Theileria sp. infecting red deer (Cervus elaphus) in northwestern Poland. Eur. J. Wildl. Res., 54: 225-230. [CrossRef]

- Seo M.G., Kwon O.D., Kwak D. Molecular detection and phylogenetic analysis of canine tick-borne pathogens from Korea. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11:101357. [CrossRef]

- Seo M.G., Yun S.H., Choi S.K., Cho G.J., Park Y.S., Cho K.H., Kwon O.D., Kwak D. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis of equine piroplasms in the Republic of Korea. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013;94:579–583. [CrossRef]

- Seong G., Han Y.J., Oh S.S., Chae J.S., Yu D.H., Park J., Park B.K., Yoo J.G., Choi K.S. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in the Korean Water Deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) from Jeonbuk Province, Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2015;53:653–659. [CrossRef]

- Seong G., Han Y.J., Oh S.S., Chae J.S., Yu D.H., Park J., Park B.K., Yoo J.G., Choi K.S. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in the Korean Water Deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) from Jeonbuk Province, Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2015;53:653–659. [CrossRef]

- Seong, G., Han, Y.J., Oh, S.S., Chae, J.S., Yu, D.H., Park, J., Park, B.K., Yoo, J.G., Choi, K.S., 2015. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in the Korean water deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) from Jeonbuk Province, Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 53(5): 653. [CrossRef]

- Sevinc, F., Maden, M., Kumas, C., Sevinc, M., Ekici, O.D., 2008. A comparative study on the prevalence of Theileria equi and Babesia caballi infections in horse sub-populations in Turkey. Vet. Parasitol., 156(3-4): 173-177. [CrossRef]

- Zanet S., Trisciuoglio A., Bottero E., de Mera I.G., Gortazar C., Carpignano M.G., Ferroglio E. Piroplasmosis in wildlife: Babesia and Theileria affecting free-ranging ungulates and carnivores in the Italian Alps. Parasit. Vectors. 2014;7:70. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Detection of Theileria, Babesia and Anaplasma using monoplex PCR. (A) Theileria 148-bp (T+ positive control, -ve negative control, Lane L; BIOLADDER 50-bp DNA ladder), (B) Babesia, 479-bp (B+ positive control, -ve control, Lane L; GB-Ruler 50-bp DNA ladder) and (C) Anaplasma, 318-bp and Lane L; BIOLADDER 50-bp DNA ladder.

Figure 1.

Detection of Theileria, Babesia and Anaplasma using monoplex PCR. (A) Theileria 148-bp (T+ positive control, -ve negative control, Lane L; BIOLADDER 50-bp DNA ladder), (B) Babesia, 479-bp (B+ positive control, -ve control, Lane L; GB-Ruler 50-bp DNA ladder) and (C) Anaplasma, 318-bp and Lane L; BIOLADDER 50-bp DNA ladder.

Figure 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria, Babesia and Anaplasma species using combination of primers in duplex fashion (A) Babesia spp. and Theileria spp., (B) Anaplasma spp. and Babesia spp., (C) Anaplasma spp. and Theileria spp. Specific amplicons for Theileria 148-bp, Babesia 479-bp, and Anaplasma 318-bp approximately. Lanes marked L: GB-Ruler 50-bp Molecular weight marker.

Figure 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria, Babesia and Anaplasma species using combination of primers in duplex fashion (A) Babesia spp. and Theileria spp., (B) Anaplasma spp. and Babesia spp., (C) Anaplasma spp. and Theileria spp. Specific amplicons for Theileria 148-bp, Babesia 479-bp, and Anaplasma 318-bp approximately. Lanes marked L: GB-Ruler 50-bp Molecular weight marker.

Figure 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria, Babesia and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR. (PCR products of Babesia 479bp, Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp). Lane L: GB-Ruler 50-bp molecular weight marker.

Figure 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria, Babesia and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR. (PCR products of Babesia 479bp, Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp). Lane L: GB-Ruler 50-bp molecular weight marker.

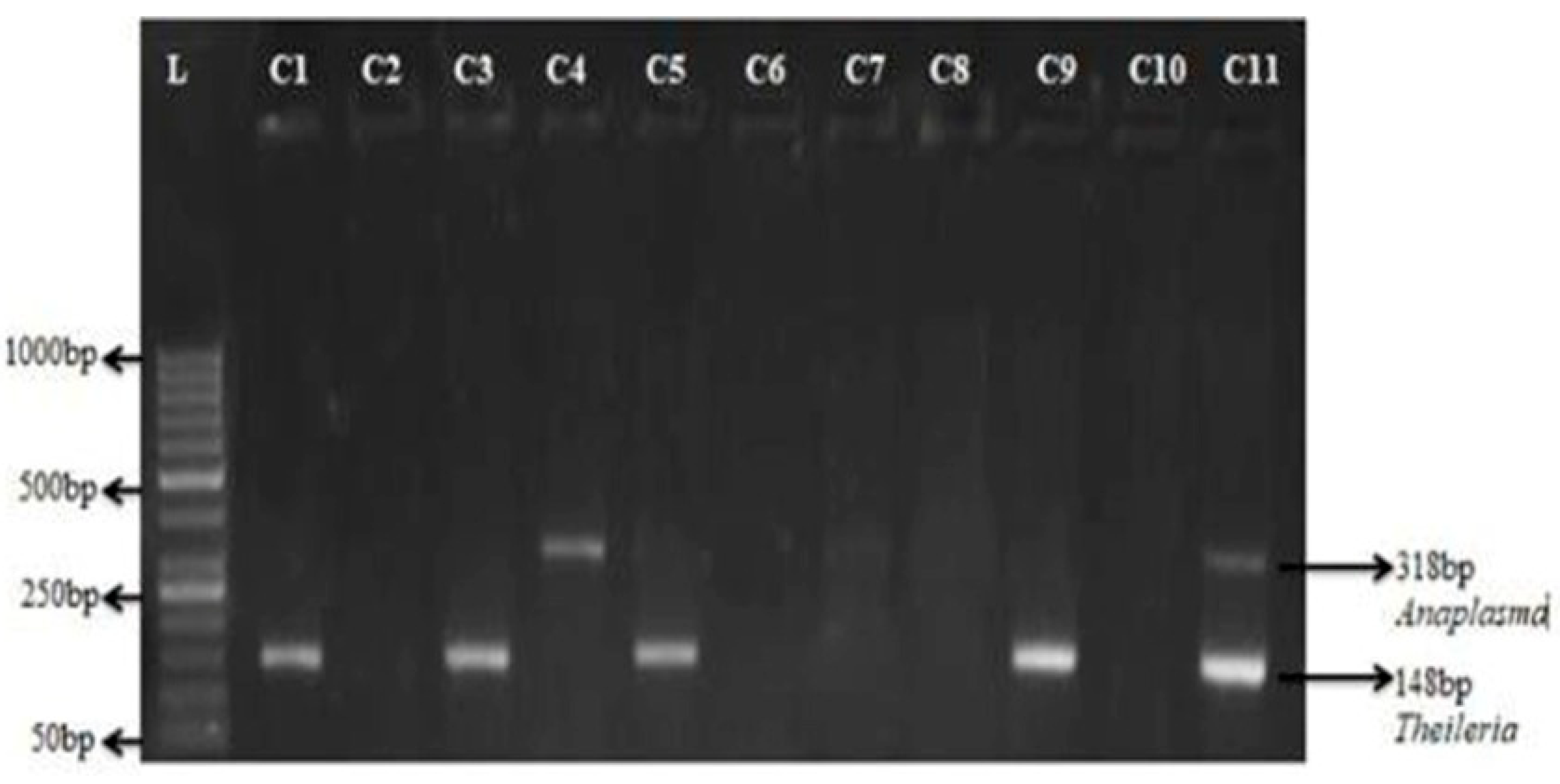

Figure 4.

Detection of Anaplasma in field samples using multiplex PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR on the Field samples of chinkara C1-C11. (PCR products Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp Lane L: 50 bp marker).

Figure 4.

Detection of Anaplasma in field samples using multiplex PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR on the Field samples of chinkara C1-C11. (PCR products Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp Lane L: 50 bp marker).

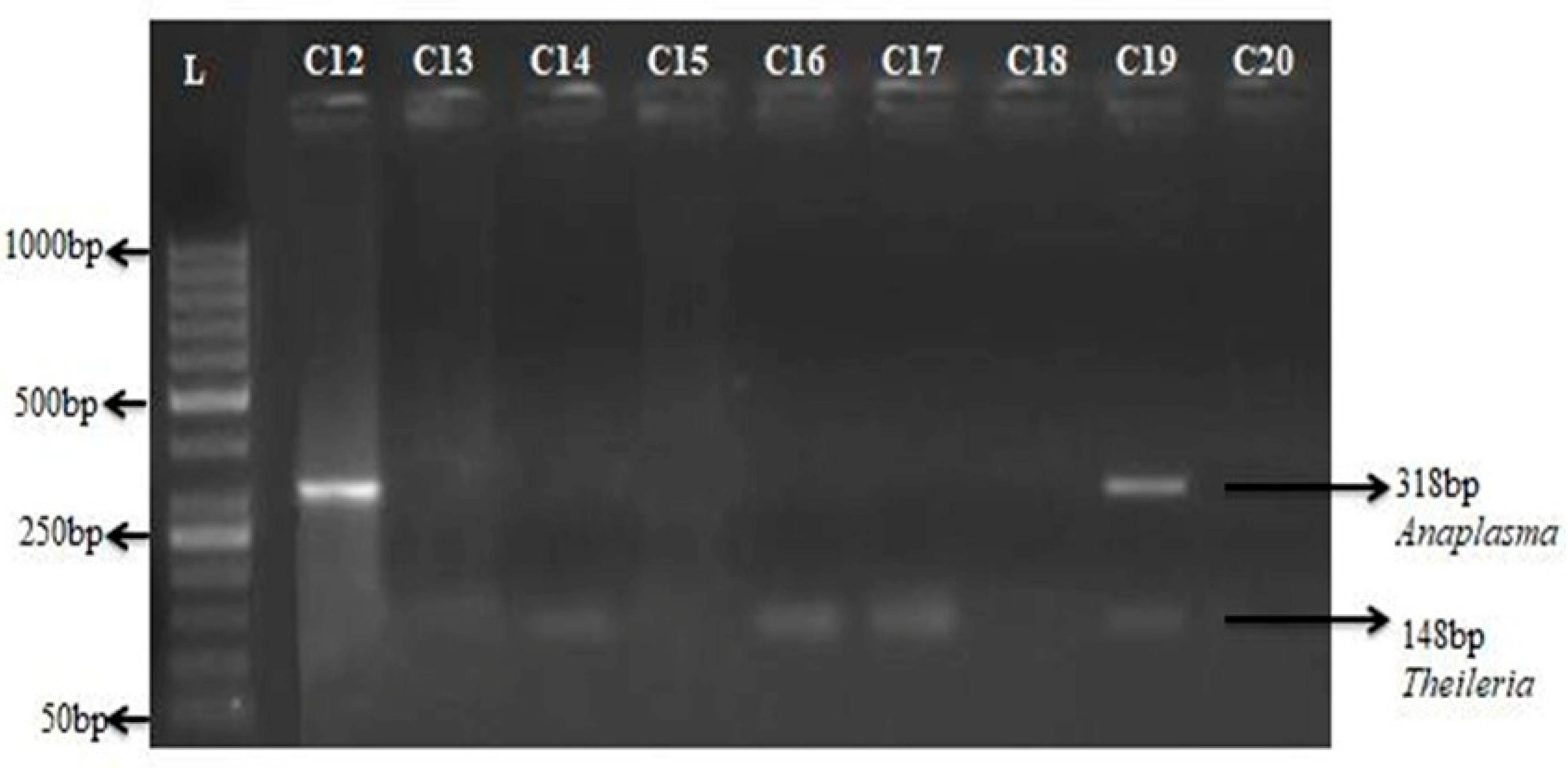

Figure 5.

Detection of Anaplasma in field samples of chinkara using multiplex PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR on the Field samples of chinkara C1-C11. (PCR products Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp Lane L: 50 bp marker).

Figure 5.

Detection of Anaplasma in field samples of chinkara using multiplex PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR on the Field samples of chinkara C1-C11. (PCR products Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp Lane L: 50 bp marker).

Figure 6.

Detection of Anaplasma in field samples of Hog deer using multiplex PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR on the Field samples of Hog deer C1-C11. (PCR products Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp Lane L: 50 bp marker).

Figure 6.

Detection of Anaplasma in field samples of Hog deer using multiplex PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR on the Field samples of Hog deer C1-C11. (PCR products Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp Lane L: 50 bp marker).

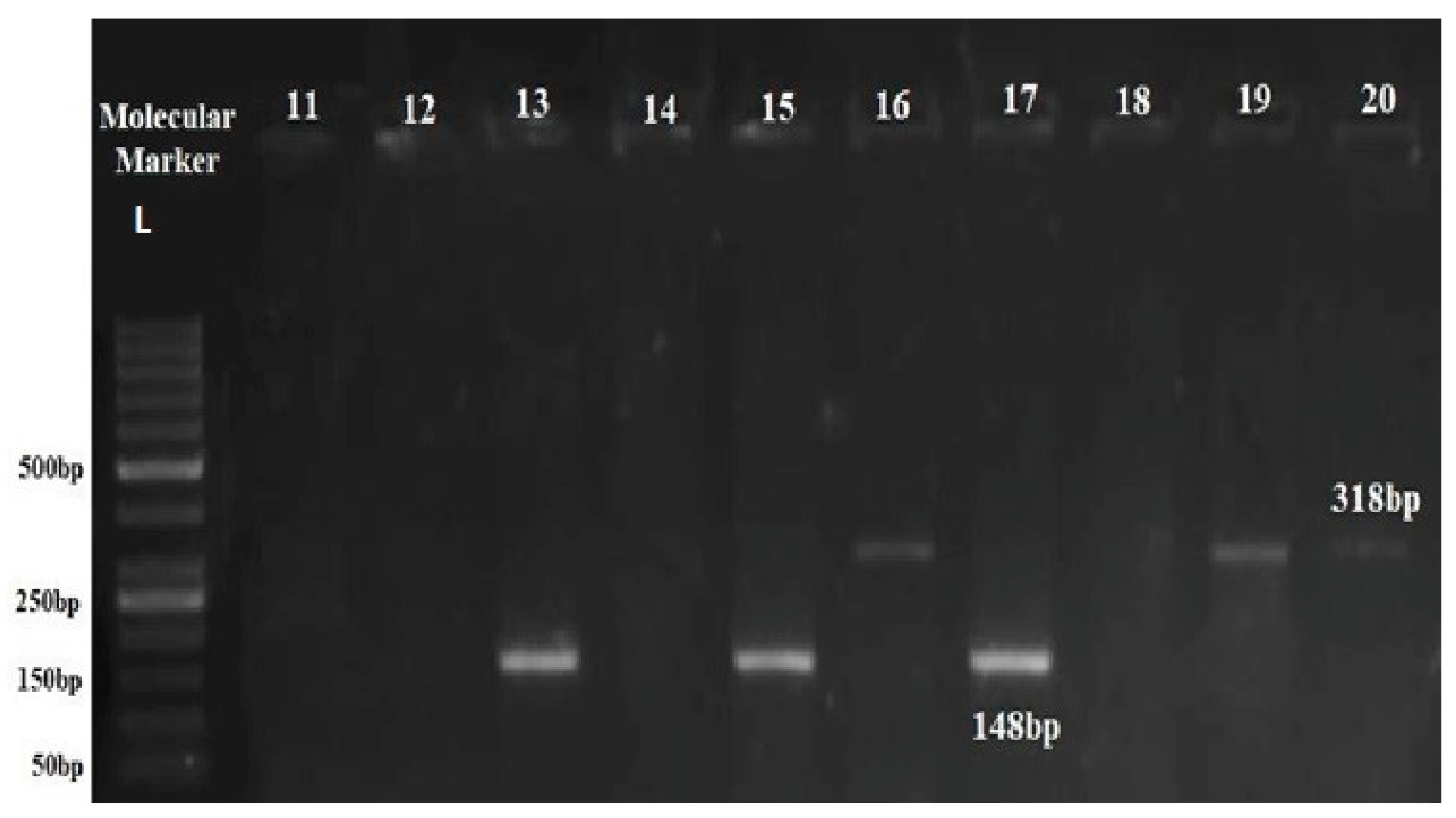

Figure 7.

Detection of Anaplasma in field samples of Hog deer using multiplex PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR on the Field samples of Hog deer C11-C20. (PCR products Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp Lane L: 50 bp marker).

Figure 7.

Detection of Anaplasma in field samples of Hog deer using multiplex PCR. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from different Theileria and Anaplasma species using multiplex PCR on the Field samples of Hog deer C11-C20. (PCR products Theileria 148bp and Anaplasma 318bp Lane L: 50 bp marker).

Table 1.

Primer sequences, targeted genes used for Anaplasma, Babesia and Theileria in the current studies.

Table 1.

Primer sequences, targeted genes used for Anaplasma, Babesia and Theileria in the current studies.

| Target organism |

Genetic marker |

Primer Sequence (5’ to 3’) |

Primer length |

Tm (oC) |

GC% |

Amplicon Size (bp) |

Anaplasmataceae

|

16sRNA Ana_F |

5’AGACGGGTGAGTAATGCAT3’ |

19

|

62.7 |

47.4

|

318 |

| 16sRNA Ana_R |

5’AAGAGTTTTACAACCCTAAG GC3’ |

22 |

62.3 |

40.9 |

Babesia spp.

|

18sRNABab_F |

5’GCTCTTTCTTGATTCTTTGGG T3’ |

22

|

62.9

|

40.9

|

479 |

| 18sRNABab_R |

5’TAGGCAAAACCGACGAATC3’ |

19 |

62 |

47.4 |

Theileria spp.

|

18sRNA

Thl_F |

5’GCTCTTTCTTGATTCTTTGGG T3’ |

22

|

62.9

|

40.9

|

148 |

18sRNA

Thl_R |

5’CTCTAAGAAGCGATAACGGG3’ |

20 |

61.6 |

50 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).