Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reis, N.R.; Peracchi, A.L.; Batista, C.B.; Rosa, G.L.M. Primatas Brasileiros: guia de campo, 1st ed.; Technical Books: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015; p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Primates in peril, 2012. Available online: http://www.iucnredlist.org/news/primates-in-peril (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Culot, L.; Mann, D.J.; Munoz, F.J.J.L.; Huynen, M.C.; Heymann, E.W. Tamarins and dung beetles: an efficient diplochorous dispersal system for Forest regeneration. Biotropica 2010, 43, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerusalinsky, L.; Melo, F.R. Conservação de Primatas no Brasil: perspectivas e desafios. In La primatología en Latinoamérica 2 – A primatologia na America Latina 2 Tomo II Costa Rica-Venezuela, 2nd ed.; Urbani, B., Kowalewski, M., Cunha, R.G.T., Torre, S., Cortés-Ortiz, L., Eds.; Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas (IVIC): Caracas, Venezuela, 2018; pp. 161–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, United States of America, 2005; pp. 111–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Well-Being of Nonhuman Primates Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Commission on Life Sciences National Research Council. The Psychological Well-Being of Nonhuman Primates, 1st ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, United States of America, 1998; pp. 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rylands, A.B.; Doris, S.F. Marmosets and Tamarins: Systematics, Behaviour, and Ecology, 1st ed.; Oxford Science Publication: Oxford, England, 1993; pp. 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivo, M. Taxonomia de Callithrix Erxleben, 1777 (Callitrichidae, Primates), 1st ed.; Fundação Biodiversitas: Belo Horizonte, Brasil, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pyritz, L.; Buntge, A.; Herzog, S.; Kessler, M. Effects of habitat structure and fragmentation on diversity and abundance of primates in tropical decíduos forests in Bolívia. Int. J. Primatol. 2010, 31, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milagres, A.P.; Rímoli, J.; Santos, M.C.; Wallace, R.B.; Rumiz, D.I.; Mollinedo, J.; Rylands, A.B. Mico melanurus (amended version of 2020 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021, e.T136294A192400781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roosmalen, M.G.M.; Van Roosmalen, T.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Rylands, A.B. Two new species of marmoset, genus Callithrix Erxleben, 1777 (Callithrichidae, Primates) from the Tapajós/Madeira interfluvium, South Central Amazonia, Brazil. Neotrop. Primates 2000, 8, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, M.A.; Spironello, W.R.; Ferreira, D.C. New occurrence records for Mico melanurus (Primates, Callitrichidae). Neotrop. Primates 2008, 15, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rímoli, J.; Milagres, A.P. Mamíferos—Mico melanurus—Sagui Marrom. Avaliação do Risco de Extinção de Mico melanurus (É. Geofrroy Em Humboldt, 1812) No Brasil. Processo de Avaliação do Risco de Extinção Da Fauna Brasileira. ICMBio, 2015.

- Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção, Vol. I, 1st ed.; ICMBio/MMA492: Brasilia, Brazil, 2018; p. 492. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, A.C.L.; Barroso, W.A.; Santos, U.F.; Portela, J.L.; Machado, A.F.; Camera, B.F.; Canale, G.R. Efeito da sazonalidade sobre o padrão comportamental de um grupo de saguis-do-rabo-preto (Mico melanurus) em um fragmento florestal urbano. In A Primatologia no Brasil, 1st ed.; Silva, V.L., Ferreira, R.G., Oliveira, M.A., Eds.; Sociedade Brasileira de Primatologia: Recife, Brazil, 2017; Volume 14, pp. 266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, I.G. Padrão de atividade do sagui Callithrix jacchus numa área de Caatinga. Master's dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, 2007.

- Ludlage, E.; Mansfield, K. Clinical care and diseases of the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Comp. Med. 2003, 53, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fitz, C.; Goodroe, A.; Wierenga, L.; Mejia, A.; Simmons, H. Clinical Management of Gastrointestinal Disease in the Common Marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). ILAR J. 2020, 61, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenacci, L.S.; Oliveira, J.B.S.; Vleeschouwer, K.M.; Carvalho Oliveira, L.; Deem, S.L.; Sousa Júnior, S.C.D.; Santos, K.R.D. Gastrointestinal parasites of Leontopithecus chrysomelas in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, P.; Bueno, C.; Soares, R.; Vieira, F.M.; Muniz-Pereira, L.C. Checklist of helminth parasites of wild primates from Brazil. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2016, 87, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, D.M.; Pereira, L.H.; Melo, A.L.; Tafuri, W.L.; Moreira, N.B.; Oliveira, C.L. Parasitism by Primasubulura jacchi (Marcel, 1857) Inglis, 1958 and Trichospirura leptostoma Smith and Chitwood, 1967 in Callithrix penicillata marmosets, trapped in wild environment and maintained in captivity. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1994, 89, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, A.L. Helminth parasites of Callithrix geoffroyi. Lab. Primate News 2004, 43, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, A.S.; Pissinatti, A.; Dib, L.V.; Siqueira, M.P.; Cardozo, M.L.; Fonseca, A.B.M.; Amendoeira, M.R.R. Balantidium coli and other gastrointestinal parasites in captives non-human primates of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J. Med. Primatol. 2015, 44, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galecki, R.; Sokol, R.; Koziatek, S. Parasites of wild animals as a potential source of hazard to humans. Annals of Parasitology 2015, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, R.P. Diagnóstico de parasitismo veterinário, 1st ed.; Sulina: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1987; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, J.J.; Rodrigues, H.O.; Gomes, D.C.; Pinto, R.M. Nematóides do Brasil. Parte V: nematóides de mamíferos. Rev. Brasil. Zoo. 1997, 14, 1–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C.; Chabaud, A.G.; Willmott, S. Keys to the nematode parasites of vertebrates: archival volume, 1st ed.; Cab international: Oxfordshire, England, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, A.O.; Lafferty, K.D.; Lotz, J.M.; Shostak, A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997, 83, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.M. Taxonomia de nematóides parasitos de primatas neotropicais, Callithrix penicillata (Geoffroy, 1812)(Primata: Callitrichidae), Alouatta guariba (Humboldt, 1812) (Primata: Atelidae) e Sapajus apella (Linnaeus, 1758) grooves, 2005 (Primata: Cebidae), do estado de Minas Gerais, 2014. Master 's dissertation, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora, 2014.

- Souza, D.D.P.; Magalhães, C.M.F.R.; Vieira, F.M.; Souzalima, S. Ocorrência de Trypanoxyuris (Trypanoxyuris) minutus (Schneider, 1866) (Nematoda, Oxyuridae) em Alouatta guariba clamitans Cabrera, 1940 (Primates, Atelidae) em Minas Gerais, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2010, 19, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verona, C.E.D.S. Parasitos em sagui-de-tufo-branco (Callithrix jacchus) no Rio de Janeiro. Doctorate’s dissertation, Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca, Rio de Janeiro, 2008.

- Strait, K.; Elese, J.G.; Eberhard, M.L. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates. In Nonhuman primates in biomedical research, 2nd ed.; Abee, C.R., Mansfield, K., Tardif, S.D., Morris, T., Eds.; Elsevier: Canada, 2012; pp. 197–297. [Google Scholar]

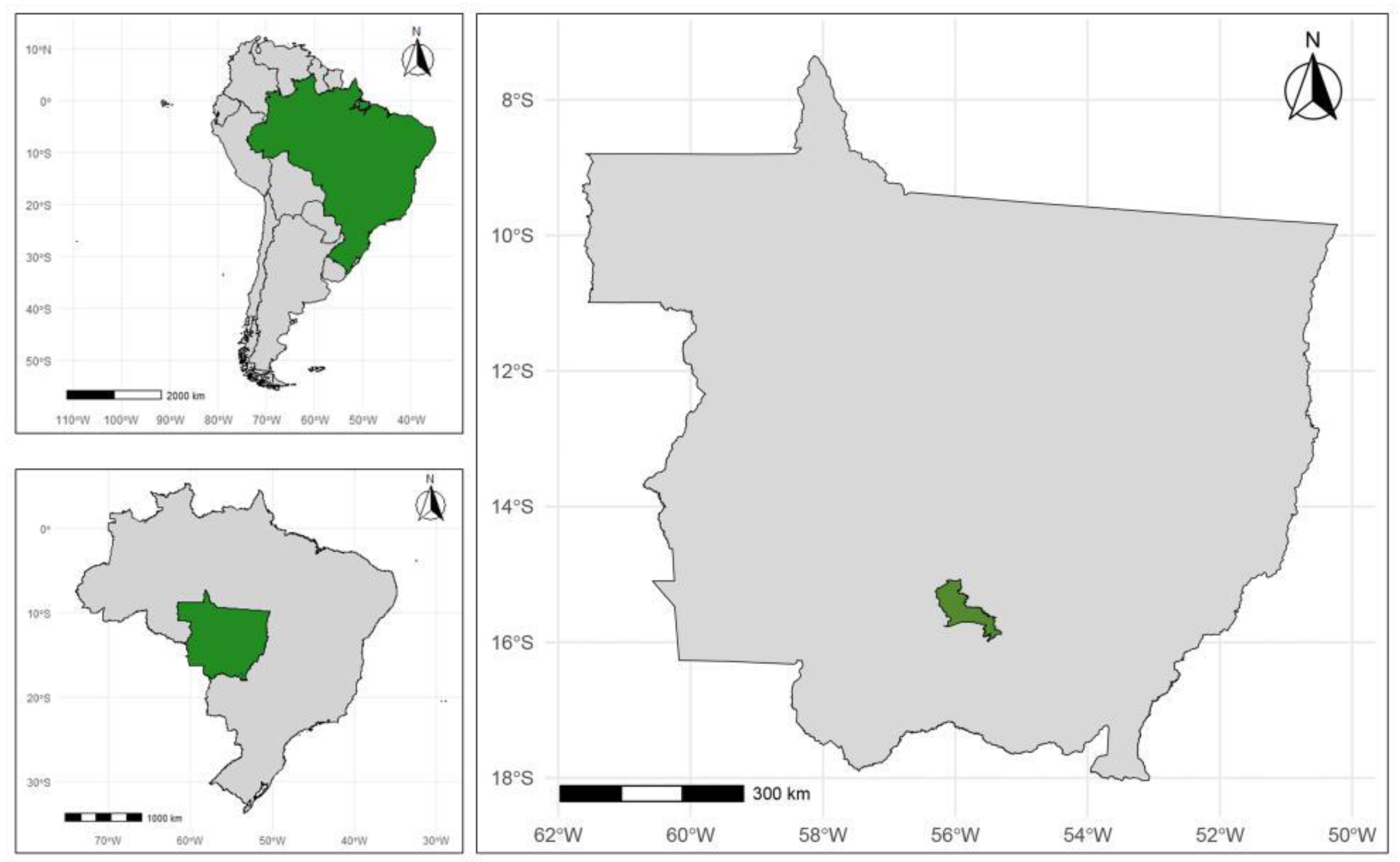

- Cândido, S.L.; Pereira, N.A.; Fonseca, M.J.O.R.; Pacheco, R.C.; Morgado, T.O.; Colodel, E.M.; Nakazato, L.; Dutra, V.; Vieira, T.S.W.J.; Aguiar, D.M. Molecular detection and genetic characterization of Ehrlichia canis and Ehrlichia sp. in neotropical primates from Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, C.; Langguth, A. Ecologia e comportamento de Callithrix jacchus (Primates: Callitrichidae) numa ilha de floresta atlântica. Rev. Nordestina Biol. 1989, 6, 105–137. [Google Scholar]

- Tavela, A.D.O.; Fuzessy, L.F.; Silva, V.H.D.; Silva, F.F.R.; Junior, M.C.; Silva, I.D.O.; Souza, V.B. Helmintos de saguis (Callithrix sp.) híbridos de vida livre vivendo em ambientes com alta atividade humana. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2013, 22, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Protocolos clínicos e diretrizes terapêuticas. Ministério da Saúde: Brasília 2010; 3.

- Urquhart, G.M.; Armour, J.; Duncan, J.L.; Dunn, A.M.; Jennings, F.W. Parasitologia veterinária, 2nd ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1998; p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Felt, S.A.; White, C.E. Evaluation of a timed and repeated perianal tape test for the detection of pinworms (Trypanoxyuris microon) in owl monkeys (Aotus nancymae). J. Med. Primatol. 2005, 34, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, D.G.S.; Santos, A.R.G.L.O.; Freitas, L.C.; Correa, S.H.R.; Kempe, G.V.; Morgado, T.O.; Aguiar, D.M.; Wof, R.W.; Rossi, R.V.; Pacheco, R.C. Endoparasites of wild animals from three biomes in the State of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Arq. Bras. Med. 2016, 68, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, R. Are there general laws in parasite ecology? Parasitol. 2007, 134, 763–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignon, M.; Sasal, P. Multiscale determinants of parasite abundance: a quantitative hierarchical approach for coral reef fishes. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010, 40, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarante, C.F.; Tassinari, W.S.; Luque, J.L.; Pereira, M.J.S. Factors associated with parasite aggregation levels in fishes from Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2015, 24, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantaleán, M.; Gozalo, A. Parasites of the Aotus monkey. In Aotus: the owl monkey, 1st ed.; Baer, J.F., Weller, R.E., Kakoma, I., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, United States of America, 1994; pp. 353–374. [Google Scholar]

- Fiennes, R.N. Pathology of simian primates Part II: infectious and parasitic diseases, 1st ed.; S. Karger: London, England, 1972; p. 770. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, N.; Galvez, H.; Montoya, E.; Gozalo, A. Mortalidad en crías de Aotus sp. (Primates: Cebidae) en cautiverio: una limitante para estudios biomédicos con modelos animales. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2006, 23, 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, R.F.F. Doenças de primatas não humanos de vida livre e em cativeiro no nordeste do Brasil. Master 's dissertation, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Paraíba, 2021.

- Jousimo, J.; Tack, A.J.; Ovaskainen, O.; Mononen, T.; Susi, H.; Tollenaere, C.; Laine, A.L. Disease ecology. Ecological and evolutionary effects of fragmentation on infectious disease dynamics. Science 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, A.; Jokela, J.; Laine, A.L. Importance of Sequence and Timing in Parasite Coinfections. Trends Parasitol. 2019, 35, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcintyre, K.M.; Setzkorn, C.; Hepworth, P.J.; Morand, S.; Morse, A.P.; Babylis, M. Systematic Assessment of the Climate Sensitivity of Important Human and Domestic Animals Pathogens in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poglayen, G.; Gelati, A.; Scala, A.; Naitana, S.; Musalla, V.; Nocerino, M.; Cringoli, G.; Regalbono, A.F.D.; Habluetzel, A. Do natural catastrophic events and exceptional climatic conditions also affect parasites? Parasitol. 2023, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE – INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/saude/22827-censo-demografico-2022.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Alho, C.J.R. Importância da biodiversidade para a saúde humana: uma perspectiva ecológica. Estud. Av. 2012, 26, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, V.M.; Tambellina, A.T.; Castro, H.A.; Waissmann, W. Saúde Ambiental e Saúde do Trabalhador: epidemiologia das relações entre a produção, o ambiente e a saúde. In Epidemiologia e Saúde, 6th ed.; MEDSI: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003; pp. 469–497. [Google Scholar]

- Seip, D.R.; Bunnell, F.L. Foraging behaviour and food habits of Stone's sheep. Can. J. Zoo. 1985, 49, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, O.M. Classification of the Acanthocephala. Folia Parasitol. 2013, 60, 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample number | Helminth species/genus | Number of individuals |

|---|---|---|

| CHUFJ - 0016 | Primasubulura jacchi | 1 |

| CHUFJ - 0017 | P. jacchi | 2 |

| CHUFJ - 0018 | P. jacchi | 5 |

| CHUFJ - 0019 | Trypanoxyuris spp. | 115 |

| CHUFJ - 0020 | P. jacchi | 9 |

| CHUFJ - 0021 | P. jacchi | 49 |

| CHUFJ - 0022 | P. jacchi | 7 |

| CHUFJ - 0023 | P. jacchi | 2 |

| CHUFJ - 0024 | P. jacchi | 15 |

| CHUFJ - 0025 | P. jacchi | 66 |

| CHUFJ - 0026 | Trypanoxyuris spp. | 11 |

| CHUFJ - 0027 | P. jacchi | 25 |

| CHUFJ - 0028 | P. jacchi | 1 |

| CHUFJ - 0029 | P. jacchi | 5 |

| CHUFJ - 0030 | P. jacchi | 94 |

| CHUFJ - 0031 | P. jacchi | 66 |

| CHUFJ - 0032 | P. jacchi | 38 |

| CHUFJ - 0033 | P. jacchi | 2 |

| CHUFJ - 0034 | P. jacchi | 132 |

| CHUFJ - 0035 | P. jacchi | 97 |

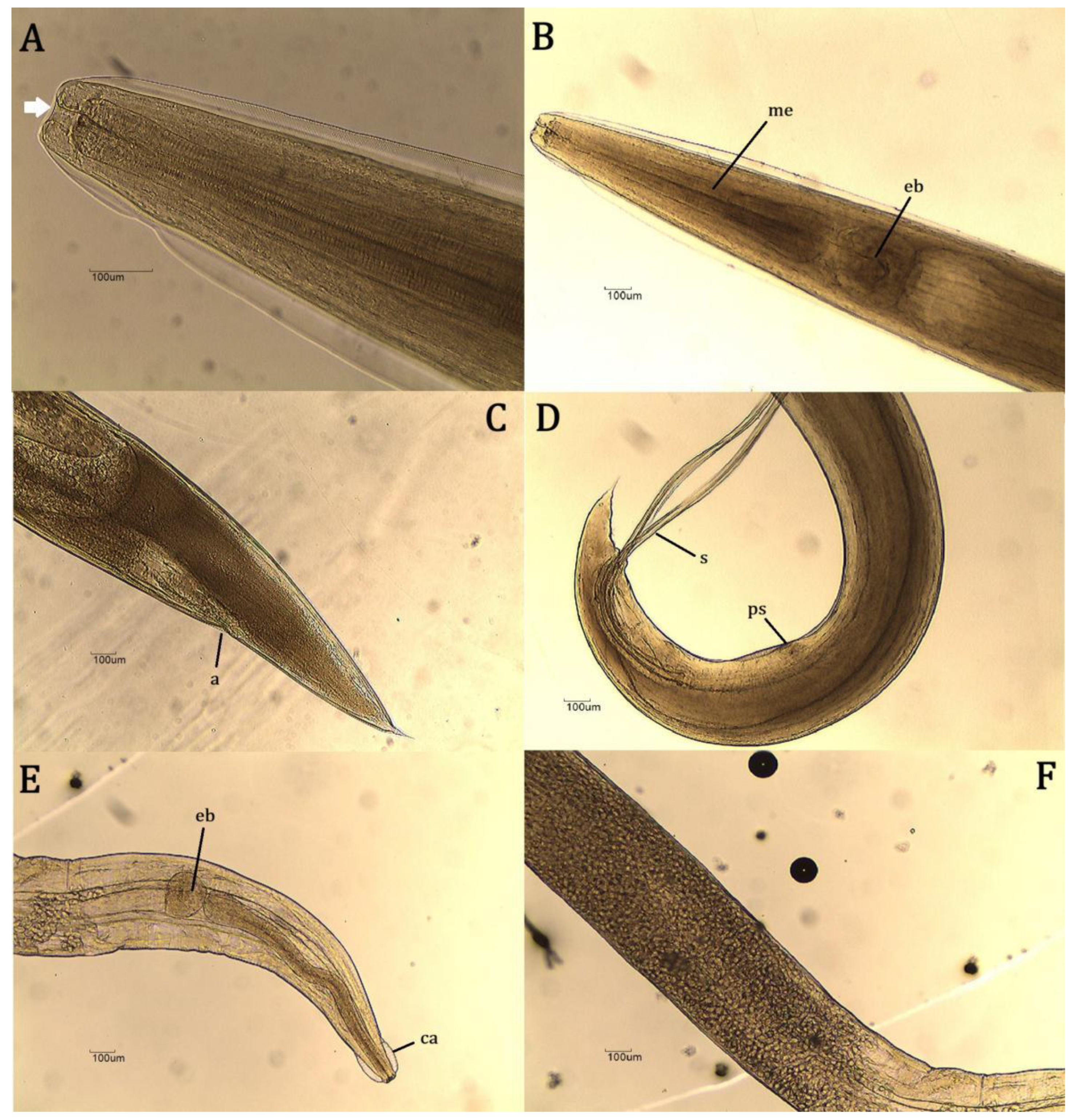

| Measurements (micrometers) | Present Study | Rocha (2014) [29] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Length | 14.100 ± 1.200 | 23.000 ± 6.000 | 12.800 ± 2.644 | 13.235 ± 7.291 |

| Width | 477 ± 111 | 658 ± 163 | 542 ± 180 | 750 ± 264 |

| Buccal capsule length | 50 ± 12 | 54 ± 9,5 | 34,5 ± 9,5 | 45 ± 10 |

| Buccal capsule width | 37 ± 7,8 | 47 ± 18 | 24 ± 9 | 23 ± 13 |

| Esophagus length | 1.238 ± 121 | 1.345 ± 221 | 991,5 ± 54,5 | 1.140 ± 119 |

| Bulb length | 267 ± 32 | 267 ± 32 | 248,5 ± 31 | 272,5 ± 71 |

| Bulb width | 225 ± 40 | 270 ± 63 | 245 ± 42 | 243,5 ± 74 |

| Spike length | 1.892 ± 249 | - | 1.542 ± 288 | - |

| Gubernaculum length | 195 ± 22,5 | - | 198 ± 15 | - |

| Distance from cloaca to posterior portion | 290,5 ± 19 | - | - | - |

| Pre-cloacal sucker length | 65 ± 22 | - | 214 ± 32 | - |

| Cloaca to suction cup distance | 584 ± 227,5 | - | - | - |

| Nerve ring length | - | 42 ± 18 | - | - |

| Nerve ring width | - | 161 ± 68 | - | - |

| Distance from anus to posterior portion | - | 902 ± 187 | - | - |

| Egg length | - | 66 ± 13 | - | 62 ± 8,5 |

| Egg width | - | 50 ± 11 | - | 52 ± 9 |

| Measurements (micrometers) | Our Study | Rocha (2014) [29] | Souza et al. (2010) [30] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 7.500 ± 1.000 | 6.650 ± 911 | 6.650 ± 690 |

| Width | 351 ± 87 | 311 ± 40 | 307 ± 45 |

| Esophagus length | 984 ± 119 | 1.600 ± 80 | 1.600 ± 50 |

| Bulb length | 136 ± 17 | - | - |

| Bulb width | 122 ± 17 | - | - |

| Nerve ring length | 44 ± 19,8 | - | - |

| Nerve ring width | 115 ± 7,8 | - | - |

| Distance from anus to posterior portion | 1.159 ± 629 | 1.470 ± 82 | 1.470 ± 90 |

| Egg length | 42,5 ± 6,2 | 47 ± 2,8 | 47 ± 2,8 |

| Egg width | 23,5 ± 1,8 | 23,5 ± 1 | 23,5 ± 0,8 |

| Vulva to the anterior portion | 1.538 ± 262 | 2.600 ± 270 | 2.600 ± 230 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).