Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Homology Modeling of Some Key Proteins of the Avian H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b (HA, NA, PB2/CBD, and M2)

2.2. Results of the Binding Affinity of the Antiviral Compounds/Ligands with the Avian H5N1 Clade 2.2.4.4b HA Protein Using the Molecular Docking Approach

2.3. Results of the Calculation of the Ligands- H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b Proteins Binding Energy – (MM-GBSA)

2.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Results for Avian H5N1 Clade 2.2.4.4b (HA, NA, PB2, and M2) Proteins and Some Selected Compounds/Drugs

2.4.1. Analysis of the RMSD Calculations Conferring Stability of Ligand-Protein Complexes

2.4.2. Analysis of the Stability and Mobility of the Interaction Between the H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b Proteins and the Selected Drugs/Compounds -RMSF

2.4.3. Assessment of the Compactness and Structural Integrity of the H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b Proteins-Ligands Complex over Time-Based on the Radius of Gyration (Rg) Using the Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations Approach

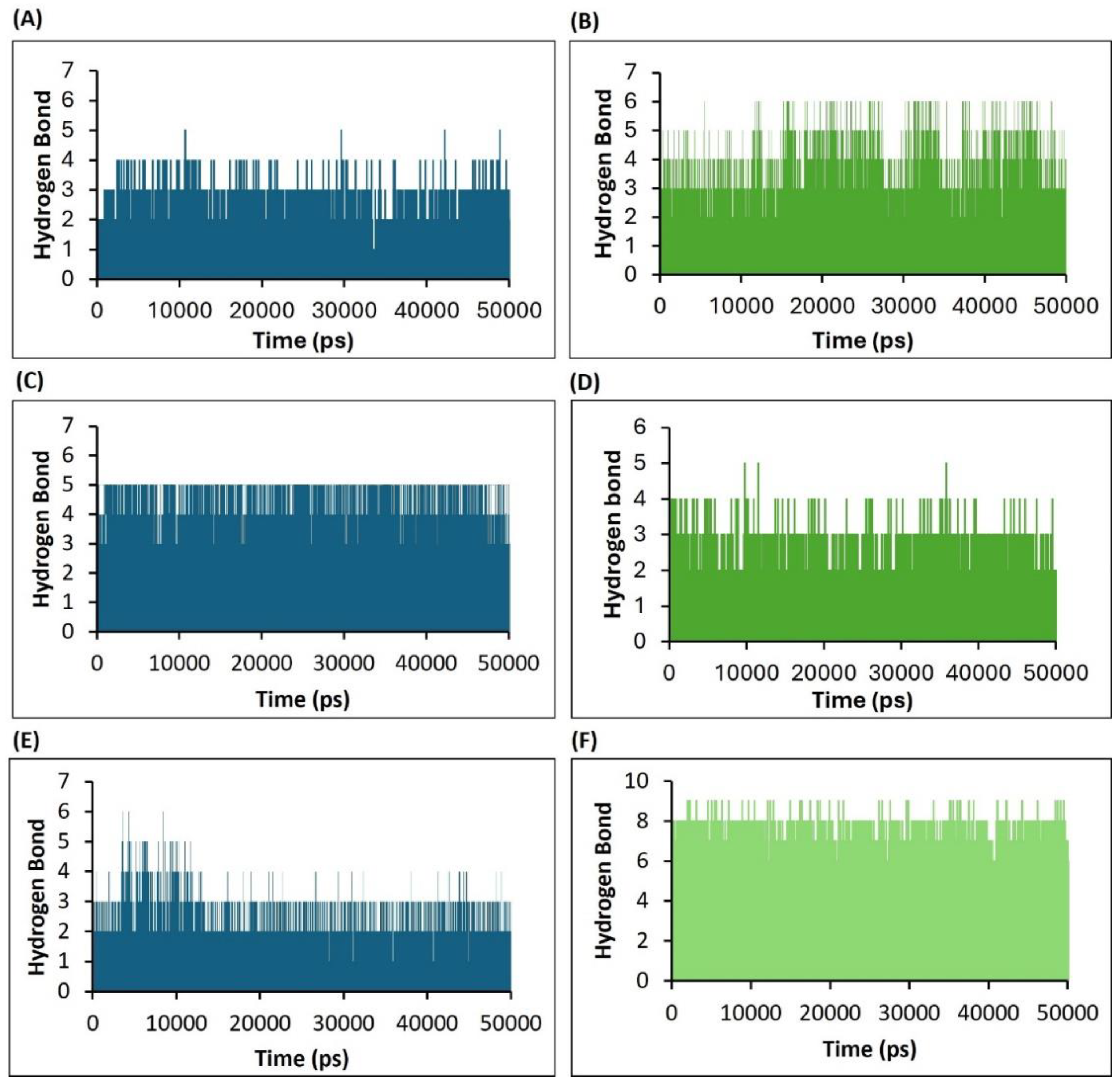

2.4.4. Assessment of H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b Proteins–Ligands Interactions Based on the Hydrogen Bonds Analysis of the Molecular Dynamics Simulations

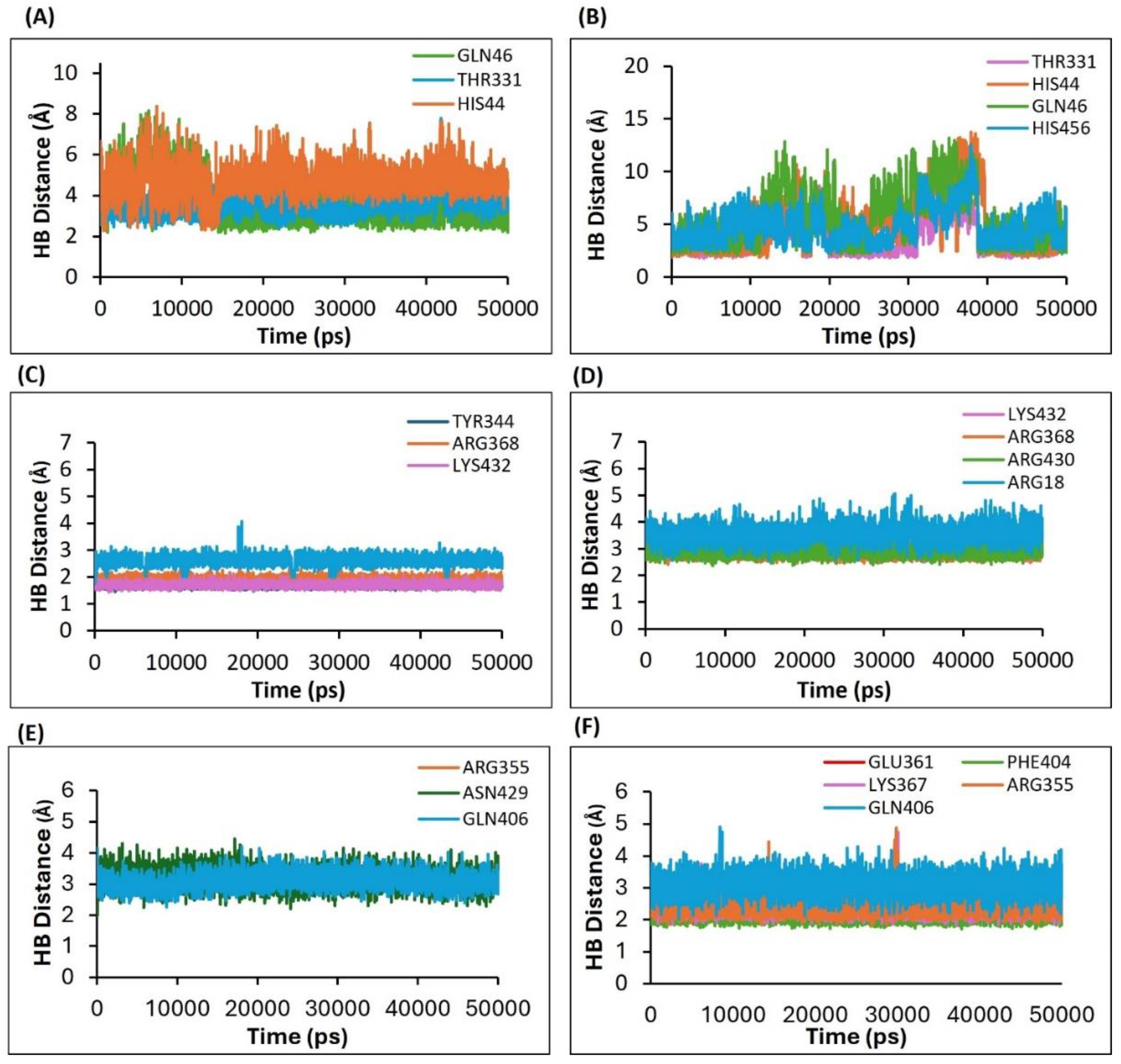

2.4.5. Results of the Estimation of the Hydrogen Bond Distances as a Measure of the Complex Stability Between the H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b with the Selected Legends

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b Sequences Retrieval from the GenBank

4.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) and Generation of the Consensus Sequences

4.3. The Homology Modeling of the H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b (HA, NA, PB2 abd M2) Proteins

4.4. Protein and Ligand Preparation

4.5. Molecular Docking of Compounds with Target Proteins

4.6. Calculations of the Molecular Mechanics-Generalize-Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA)

4.7. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dou, D.; Revol, R.; Ostbye, H.; Wang, H.; Daniels, R. Influenza A Virus Cell Entry, Replication, Virion Assembly and Movement. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vlugt, C.; Sikora, D.; Pelchat, M. Insight into Influenza: A Virus Cap-Snatching. Viruses 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, L.D. Avian influenza: past, present and future. Rev Sci Tech 2024, Special Edition, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Webster, R.G.; Webby, R.J. Influenza Virus: Dealing with a Drifting and Shifting Pathogen. Viral Immunol 2018, 31, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y. Pathogenicity and virulence of influenza. Virulence 2023, 14, 2223057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayun, F.; Khan, F.; Fawad, N.; Shamas, S.; Fazal, S.; Khan, A.; Ali, A.; Farhan, A.; Wei, D.Q. Computational Method for Classification of Avian Influenza A Virus Using DNA Sequence Information and Physicochemical Properties. Front Genet 2021, 12, 599321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webby, R.J.; Uyeki, T.M. An Update on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus, Clade 2.3.4.4b. J Infect Dis 2024, 230, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrough, E.R.; Magstadt, D.R.; Petersen, B.; Timmermans, S.J.; Gauger, P.C.; Zhang, J.; Siepker, C.; Mainenti, M.; Li, G.; Thompson, A.C.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus Infection in Domestic Dairy Cattle and Cats, United States, 2024. Emerg Infect Dis 2024, 30, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulit-Penaloza, J.A.; Brock, N.; Belser, J.A.; Sun, X.; Pappas, C.; Kieran, T.J.; Basu Thakur, P.; Zeng, H.; Cui, D.; Frederick, J.; et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus of clade 2.3.4.4b isolated from a human case in Chile causes fatal disease and transmits between co-housed ferrets. Emerg Microbes Infect 2024, 13, 2332667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loregian, A.; Mercorelli, B.; Nannetti, G.; Compagnin, C.; Palu, G. Antiviral strategies against influenza virus: towards new therapeutic approaches. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014, 71, 3659–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Gu, Z.; Mao, L.; Ge, Y.; Hou, D.; Fang, J.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Z. Influenza-existing drugs and treatment prospects. Eur J Med Chem 2022, 232, 114189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vries, E.; Schutten, M.; Fraaij, P.; Boucher, C.; Osterhaus, A. Influenza virus resistance to antiviral therapy. Adv Pharmacol 2013, 67, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S. Emerging antiviral therapies and drugs for the treatment of influenza. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2022, 27, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomini, A.; Mercorelli, B.; Loregian, A. Antiviral strategies against influenza virus: an update on approved and innovative therapeutic approaches. Cell Mol Life Sci 2025, 82, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Wohlbold, T.J.; Zheng, N.Y.; Huang, M.; Huang, Y.; Neu, K.E.; Lee, J.; Wan, H.; Rojas, K.T.; Kirkpatrick, E.; et al. Influenza Infection in Humans Induces Broadly Cross-Reactive and Protective Neuraminidase-Reactive Antibodies. Cell 2018, 173, 417–429.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Bao, Z.; Tang, S.; Yi, C.; Sun, B. Broadly neutralizing antibodies to combat influenza virus infection. Antiviral Res 2024, 221, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ma, C.; Wang, J. Inhibitors targeting the influenza virus hemagglutinin. Curr Med Chem 2015, 22, 1361–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, F.G.; Atmar, R.L.; Schilling, M.; Johnson, C.; Poretz, D.; Paar, D.; Huson, L.; Ward, P.; Mills, R.G. Use of the selective oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir to prevent influenza. N Engl J Med 1999, 341, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, R.C. Treating influenza with zanamivir. Lancet 1998, 352, 1872–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slain, D. Intravenous Zanamivir: A Viable Option for Critically Ill Patients With Influenza. Ann Pharmacother 2021, 55, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massari, S.; Desantis, J.; Nizi, M.G.; Cecchetti, V.; Tabarrini, O. Inhibition of Influenza Virus Polymerase by Interfering with Its Protein-Protein Interactions. ACS Infect Dis 2021, 7, 1332–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Guo, Y.; Gao, X.; Peng, W.; Shu, S.; Zhao, C.; Cui, D.; et al. BAG6 inhibits influenza A virus replication by inducing viral polymerase subunit PB2 degradation and perturbing RdRp complex assembly. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finberg, R.W.; Lanno, R.; Anderson, D.; Fleischhackl, R.; van Duijnhoven, W.; Kauffman, R.S.; Kosoglou, T.; Vingerhoets, J.; Leopold, L. Phase 2b Study of Pimodivir (JNJ-63623872) as Monotherapy or in Combination With Oseltamivir for Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Seasonal Influenza A: TOPAZ Trial. J Infect Dis 2019, 219, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neil, B.; Ison, M.G.; Hallouin-Bernard, M.C.; Nilsson, A.C.; Torres, A.; Wilburn, J.M.; van Duijnhoven, W.; Van Dromme, I.; Anderson, D.; Deleu, S.; et al. A Phase 2 Study of Pimodivir (JNJ-63623872) in Combination With Oseltamivir in Elderly and Nonelderly Adults Hospitalized With Influenza A Infection: OPAL Study. J Infect Dis 2022, 226, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayari, M.G.; Favetta, P.; Warszycki, D.; Vasseur, V.; Herve, V.; Degardin, P.; Carbonnier, B.; Si-Tahar, M.; Agrofoglio, L.A. Molecularly Imprinted Hydrogels Selective to Ribavirin as New Drug Delivery Systems to Improve Efficiency of Antiviral Nucleoside Analogue: A Proof-of-Concept Study with Influenza A Virus. Macromol Biosci 2022, 22, e2100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosaro, E.; Pires, J.; Castillo, D.; Murphy, B.G.; Reagan, K.L. Efficacy of Oral Remdesivir Compared to GS-441524 for Treatment of Cats with Naturally Occurring Effusive Feline Infectious Peritonitis: A Blinded, Non-Inferiority Study. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.G.; Perron, M.; Murakami, E.; Bauer, K.; Park, Y.; Eckstrand, C.; Liepnieks, M.; Pedersen, N.C. The nucleoside analog GS-441524 strongly inhibits feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) virus in tissue culture and experimental cat infection studies. Vet Microbiol 2018, 219, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhang, J.; Bourgeois, M.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.; Recuenco, S.; Gomez, J.; et al. New world bats harbor diverse influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.F.A.; Cheng, H.; Tundup, S.; Antanasijevic, A.; Varhegyi, E.; Perez, J.; AbdulRahman, E.M.; Elenany, M.G.; Helal, S.; Caffrey, M.; et al. Identification of entry inhibitors with 4-aminopiperidine scaffold targeting group 1 influenza A virus. Antiviral Res 2020, 177, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Chu, H.; Zhang, K.; Ye, J.; Singh, K.; Kao, R.Y.; Chow, B.K.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, B.J. A novel small-molecule compound disrupts influenza A virus PB2 cap-binding and inhibits viral replication. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016, 71, 2489–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charostad, J.; Rezaei Zadeh Rukerd, M.; Mahmoudvand, S.; Bashash, D.; Hashemi, S.M.A.; Nakhaie, M.; Zandi, K. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: An imminent threat at doorstep. Travel Med Infect Dis 2023, 55, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.; Luthy, R.; Bowie, J.U. VERIFY3D: assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Methods Enzymol 1997, 277, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, W.I.; Cusack, S.C.; Brown, J.H.; Daniels, R.S.; Skehel, J.J.; Wiley, D.C. The structure of a membrane fusion mutant of the influenza virus haemagglutinin. EMBO J 1990, 9, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, T.M.; Jaentschke, B.; Van Domselaar, G.; Hashem, A.M.; Farnsworth, A.; Forbes, N.E.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; He, R.; Brown, E.G.; et al. The universal epitope of influenza A viral neuraminidase fundamentally contributes to enzyme activity and viral replication. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 18283–18289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, P.M. Zanamivir: an influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitor. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2005, 3, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, S.D.; Hong, M. Amantadine-induced conformational and dynamical changes of the influenza M2 transmembrane proton channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.H.; Holsinger, L.J.; Lamb, R.A. Influenza virus M2 protein has ion channel activity. Cell 1992, 69, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakov, D.; Chuang, G.Y.; Beglov, D.; Vajda, S. Where does amantadine bind to the influenza virus M2 proton channel? Trends Biochem Sci 2010, 35, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaston, J.L.; Samways, M.L.; Konstantinidi, A.; Ma, C.; Hu, Y.; Bruce Macdonald, H.E.; Wang, J.; Essex, J.W.; DeGrado, W.F.; Kolocouris, A. Rimantadine Binds to and Inhibits the Influenza A M2 Proton Channel without Enantiomeric Specificity. Biochemistry 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intharathep, P.; Laohpongspaisan, C.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; Loisruangsin, A.; Malaisree, M.; Decha, P.; Aruksakunwong, O.; Chuenpennit, K.; Kaiyawet, N.; Sompornpisut, P.; et al. How amantadine and rimantadine inhibit proton transport in the M2 protein channel. J Mol Graph Model 2008, 27, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzied, A.S.; Alqarni, S.; Younes, K.M.; Alanazi, S.M.; Alrsheed, D.M.; Alhathal, R.K.; Huwaimel, B.; Elkashlan, A.M. Structural and free energy landscape analysis for the discovery of antiviral compounds targeting the cap-binding domain of influenza polymerase PB2. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 25441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouzied, A.S.; Alqarni, S.; Younes, K.M.; Alanazi, S.M.; Alrsheed, D.M.; Alhathal, R.K.; Huwaimel, B.; Elkashlan, A.M. Author Correction: Structural and free energy landscape analysis for the discovery of antiviral compounds targeting the cap-binding domain of influenza polymerase PB2. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, L.; Amichai, S.; Zandi, K.; Cox, B.; Schinazi, R.; Amblard, F. Novel influenza polymerase PB2 inhibitors for the treatment of influenza A infection. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2019, 29, 126639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, S.; Speranzini, V.; Hashimoto, T.; Noshi, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kawai, M.; Kawaguchi, K.; Uehara, T.; Shishido, T.; Naito, A.; et al. Characterization of influenza virus variants induced by treatment with the endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 9633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graef, K.M.; Vreede, F.T.; Lau, Y.F.; McCall, A.W.; Carr, S.M.; Subbarao, K.; Fodor, E. The PB2 subunit of the influenza virus RNA polymerase affects virulence by interacting with the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein and inhibiting expression of beta interferon. J Virol 2010, 84, 8433–8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumosani, T.A.; Abbas, A.T.; Basheer, B.; Hassan, A.M.; Yaghmoor, S.S.; Alyahiby, A.H.; Asseri, A.H.; Dwivedi, V.D.; Azhar, E.I. Investigating Pb2 CAP-binding domain inhibitors from marine bacteria for targeting the influenza A H5N1. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0310836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, J.; Babusis, D.; Vermillion, M.S.; Subramanian, R.; Barrett, K.; Lye, D.; Ma, B.; Zhao, X.; Riola, N.; Xie, X.; et al. Intravenous delivery of GS-441524 is efficacious in the African green monkey model of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Antiviral Res 2022, 203, 105329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, N.; Royster, A.; Ren, S.; Ma, Y.; Pintado, M.; Mir, M.; Mir, S. A novel compound targets the feline infectious peritonitis virus nucleocapsid protein and inhibits viral replication in cell culture. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 102976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.M.; Wolf, J.D.; Lieber, C.M.; Sourimant, J.; Lin, M.J.; Babusis, D.; DuPont, V.; Chan, J.; Barrett, K.T.; Lye, D.; et al. Oral prodrug of remdesivir parent GS-441524 is efficacious against SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Y.; Shah, A.U.; Duraisamy, N.; ElAlaoui, R.N.; Cherkaoui, M.; Hemida, M.G. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence and Gene Expression Analysis to Identify Some Potential Bovine Coronavirus (BCoV) Receptors and Host Cell Enzymes Potentially Involved in the Viral Replication and Tissue Tropism. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda-Shitaka, M.; Nojima, H.; Takaya, D.; Kanou, K.; Iwadate, M.; Umeyama, H. Evaluation of homology modeling of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus main protease for structure based drug design. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2004, 52, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.Y.; Zhang, H.X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des 2011, 7, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agu, P.C.; Afiukwa, C.A.; Orji, O.U.; Ezeh, E.M.; Ofoke, I.H.; Ogbu, C.O.; Ugwuja, E.I.; Aja, P.M. Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, J.K.; Law, S.M.; Brooks, C.L. , 3rd. Flexible CDOCKER: Development and application of a pseudo-explicit structure-based docking method within CHARMM. J Comput Chem 2016, 37, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Vilseck, J.Z.; Brooks, C.L. , 3rd. Accelerated CDOCKER with GPUs, Parallel Simulated Annealing, and Fast Fourier Transforms. J Chem Theory Comput 2020, 16, 3910–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Nabi, R.; Alvi, S.S.; Khan, M.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.Y.; Hussain, I.; Shahanawaz, S.D.; Khan, M.S. Carvacrol protects against carbonyl osmolyte-induced structural modifications and aggregation to serum albumin: Insights from physicochemical and molecular interaction studies. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 213, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.F.; Tan, Q.Q.; Liang, S.S.; Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Shaw, P.C.; Wang, J.; Hu, C. Structure-based virtual screening of influenza virus RNA polymerase inhibitors from natural compounds: Molecular dynamics simulation and MM-GBSA calculation. Comput Biol Chem 2020, 85, 107241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Predicted Homology Model | PDF total energy | DOPE Score | Verify Score | Verify Expected High Score | Expected Low Score |

| 1 | HA | 26755 | -54478 | 205 | 232 | 104 |

| 2 | NA | 18118 | -43552 | 180 | 176 | 79 |

| 3 | PB2/CBD | 1926 | -79787 | 277 | 333 | 154 |

| 4 | M2 | 5702 | -10588 | 31 | 45 | 20 |

| N | Protein | Ligands/ Compound-ID |

MM-GBSA Binding energy |

-CDOCK Score (Binding affinity score) |

Interacting amino acid residues |

| 1 | HA | *F0045(S) (CID: 25281297) |

-48.864 | 22.9215 | HIS24, TRP366, ILE390, VAL393 |

| 2 | HA | GS441524 (CID: 44468216) |

-61.432 | 26.672 | ALA45, THR331, ILE390, VAL393, THR394 |

| 3 | PB2/CBD | *MGT (CID: 175837) |

-486.373 | 80.6777 | PHE323, PHE325, LYS339, ARG355, HIS357, GLU361, VAL403, PHE404, MET431 |

| 4 | PB2/CBD | *PB2-39 (CID: 54694510) |

-236.799 | 54.5527 | PHE404, ASN429, PRO430, HIS432, ARG355 |

| 5 | PB2/CBD | Sofosbuvir (CID: 45375808) |

-110.053 | 50.8859 | PHE323, SER324, LYS339, HIS357, LYS367 |

| 6 | PB2/CBD | GS441524 (CID: 44468216) |

-99.0791 | 34.2346 | ARG324, ARG355, HIS357, PHE404, GLN406, GLU361, LYS376 |

| 7 | NA | *Zanamivir (CID: 60855) |

-201 | 49.26 | ASP151, TYR344, SER367, ARG368, LYS432 |

| 8 | NA | *Oseltamivir (CID: 65028) |

28 | -65.74 | SER101, ASP103, ILE117, ILE122, THR131, PRO162, VAL163, GLU165, PRO167, SER441 |

| 9 | NA | GS441524 (CID: 44468216) |

-83.10 | 32.34 | VAL149, ASP151, SER367, ARG368, PRO431, LYS432 |

| 10 | NA | Sofosbuvir (CID: 45375808) |

-138.23 | 53.43 | VAL149, ASP151, ARG225, GLU278, TYR344, ARG368, TYR402, ILE427, PRO431, LYS432 |

| 11 | M2 | Rimantadine (CID: 5071) |

-112.23 | 33.02 | Chain 1: AlA30; Chain 2: VAL27,ALA30 Chain 3: ALA30; Chain 4: VAL27, ALA30 |

| 12 | M2 | Amantadine (CID: 5071) |

-104.46 | 27.55 | Chain 2: VAL27,ALA30; Chain 3: ALA30; Chain 4: ALA30, GLY34 |

| 13 | M2 | Sofosbuvir (CID: 45375808) |

-116.11 | 62.05 | Chain 1: VAL27, AlA30, GLY34, HIS37; Chain 2: ALA30, SER31, HIS37, LEU38 Chain 3: VAL27, ALA30, HIS37 Chain 4: VAL27, ALA30, GLY34, HIS37 |

| 14 | M2 | GS441524 (CID: 44468216) |

-120.65 | 42.59 | Chain 1: AlA30, GLY34; Chain 2: SER22, VAL27, ALA30 Chain 3: ALA30, HIS37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).