Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

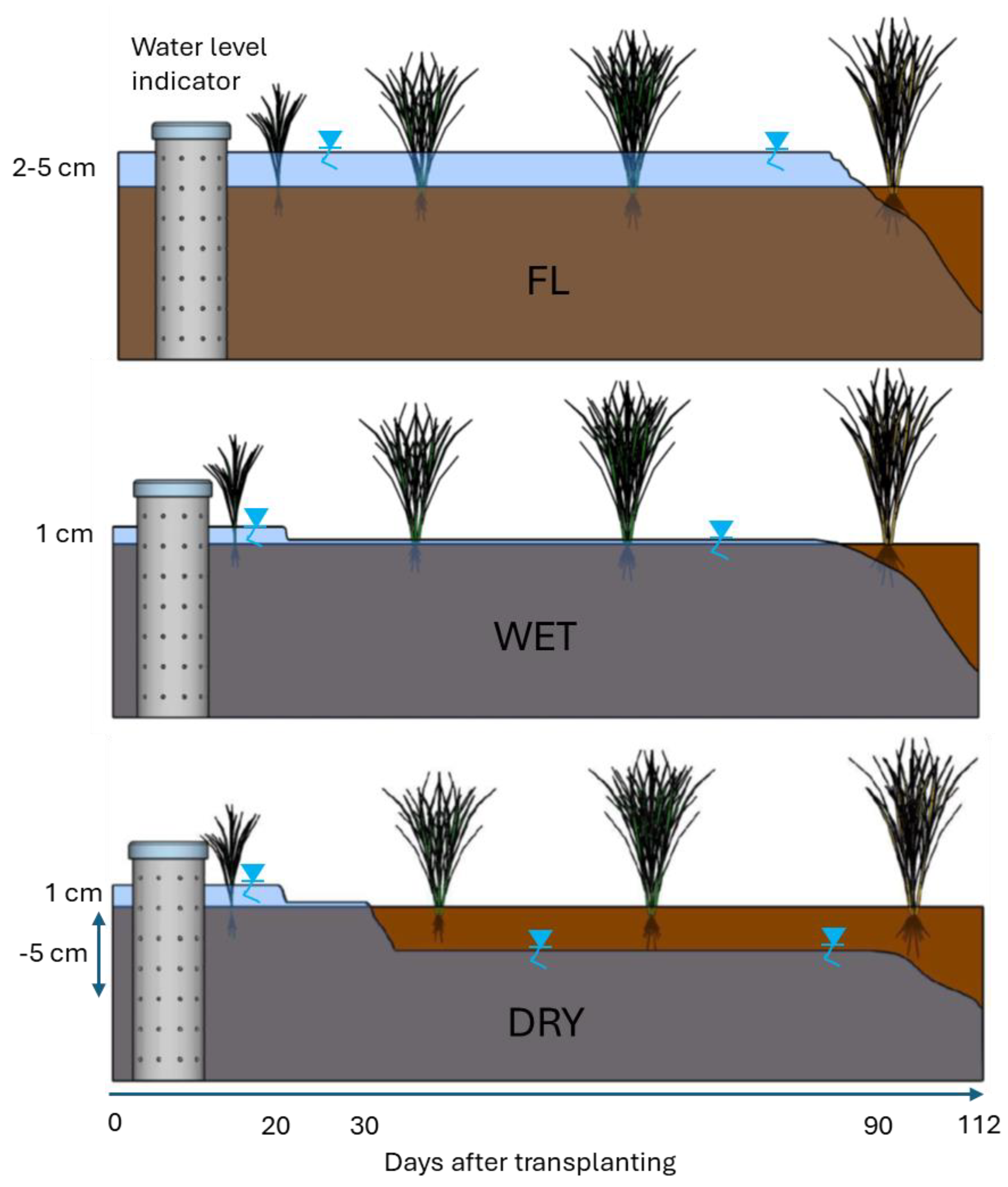

2.1. Experimental setup

2.2. Greenhouse gas emission measurements and analysis

2.3. Water and weathers parameters measurements

2.4. Yield, water productivity, and water use efficiency

3. Results

3.1. Weather conditions among crop seasons

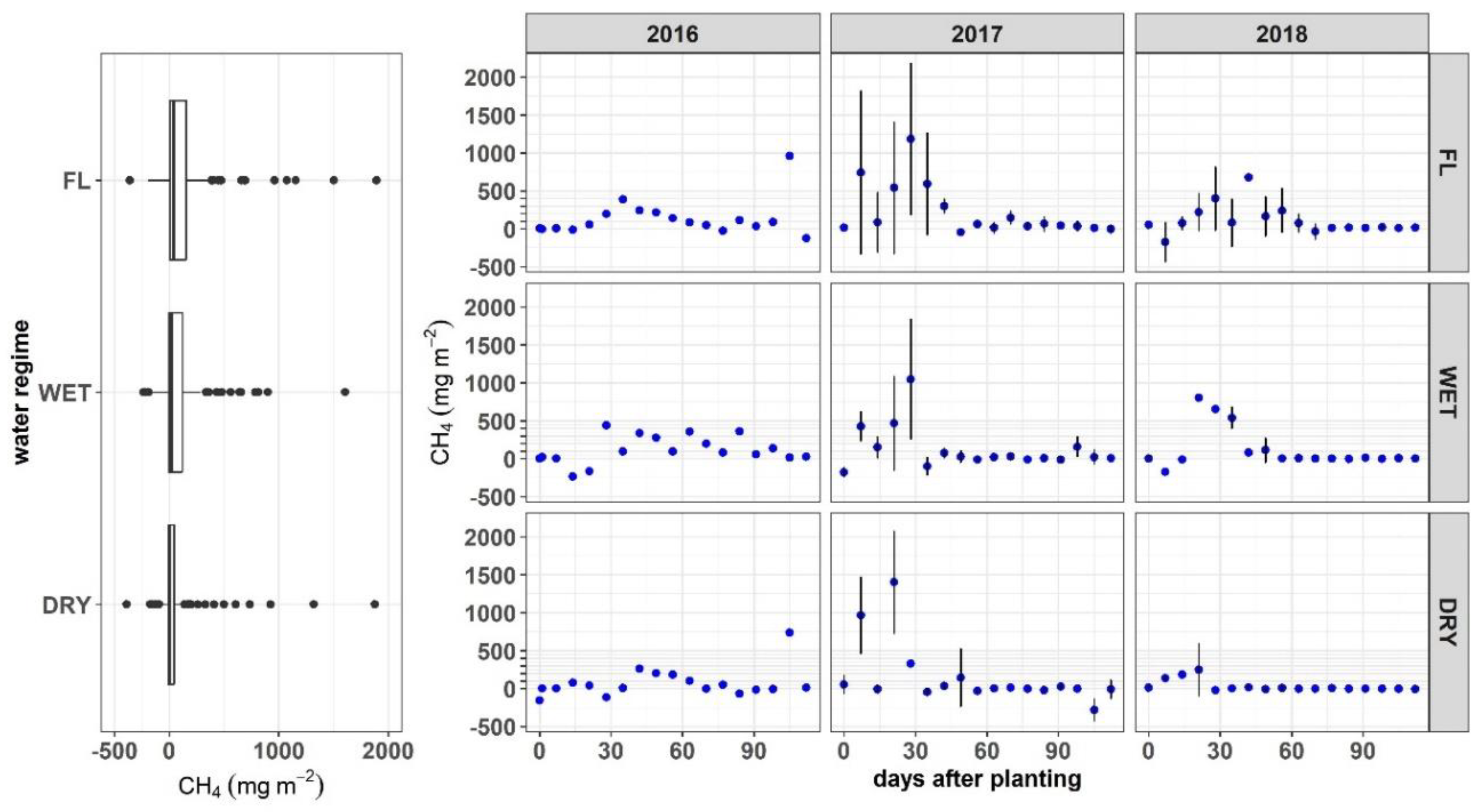

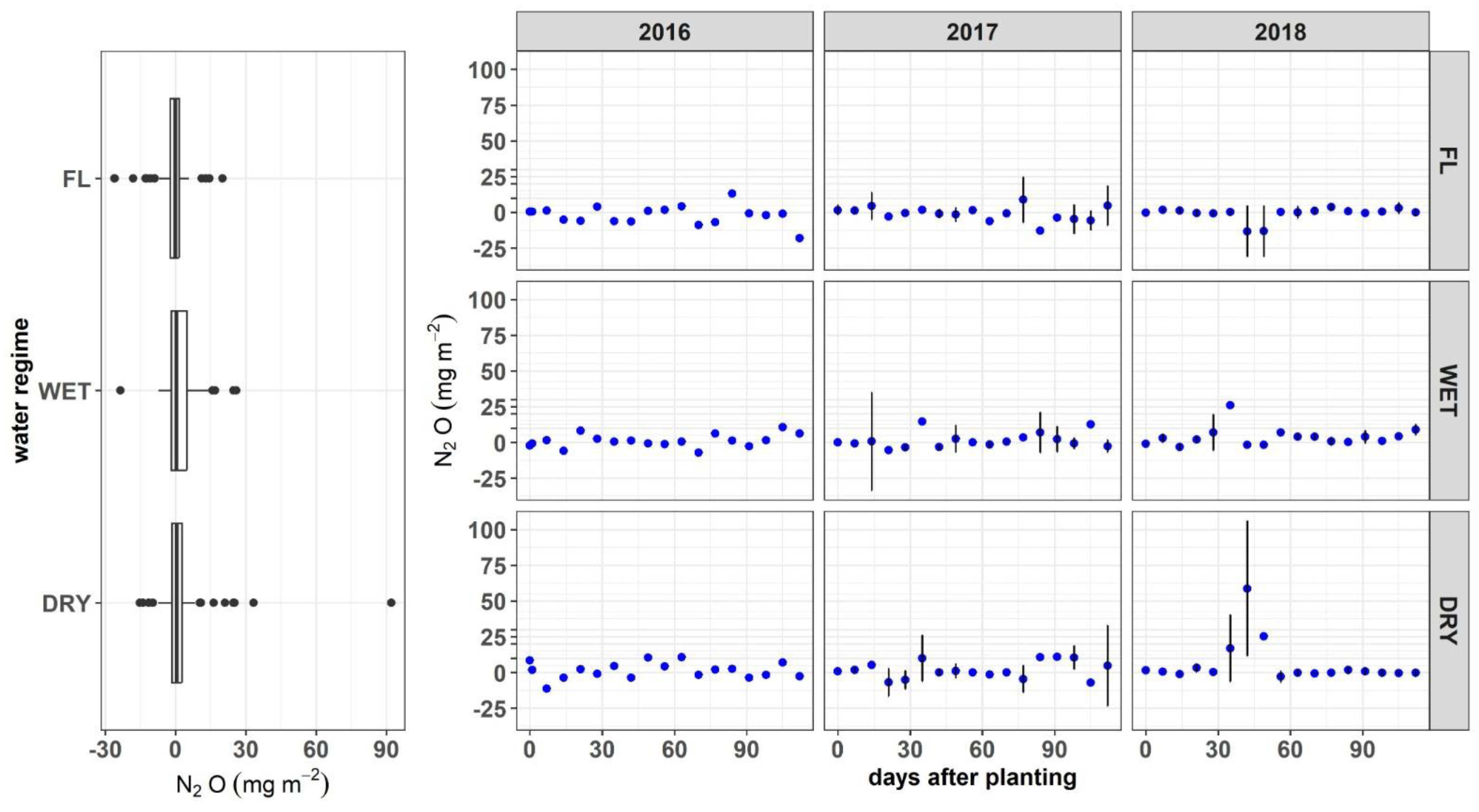

3.2. Seasonal CH4 and N2O emissions

3.3. Water productivity and water use efficiency among regimes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gangopadhyay, S.; Chowdhuri, I.; Das, N.; Pal, S.C.; Mandal, S. The Effects of No-Tillage and Conventional Tillage on Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Paddy Fields with Various Rice Varieties. Soil and Tillage Research 2023, 232, 105772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, A.Z.; Sudo, S.; Fumoto, T.; Inubushi, K.; Ono, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D.; Win, K.T.; Umamageswari, C.; Bama, K.S.; et al. Field Validation of the DNDC-Rice Model for Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Double-Cropping Paddy Rice under Different Irrigation Practices in Tamil Nadu, India. Agriculture 2020, 10, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwire, D.; Saito, H.; Sidle, R.C.; Nishiwaki, J. Water Management and Hydrological Characteristics of Paddy-Rice Fields under Alternate Wetting and Drying Irrigation Practice as Climate Smart Practice: A Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Zhu, X.; Huang, S.; Linquist, B.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wassmann, R.; Minamikawa, K.; Martinez-Eixarch, M.; Yan, X.; Zhou, F.; et al. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Mitigation in Rice Agriculture. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2023, 4, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgreen, J.; Parr, A. Exploring the Impact of Alternate Wetting and Drying and the System of Rice Intensification on Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Review of Rice Cultivation Practices. Agronomy 2024, 14, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallareddy, M.; Thirumalaikumar, R.; Balasubramanian, P.; Naseeruddin, R.; Nithya, N.; Mariadoss, A.; Eazhilkrishna, N.; Choudhary, A.K.; Deiveegan, M.; Subramanian, E.; et al. Maximizing Water Use Efficiency in Rice Farming: A Comprehensive Review of Innovative Irrigation Management Technologies. Water 2023, 15, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, N.; Dazzo, F.B. Making Rice Production More Environmentally-Friendly. Environments 2016, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Dubey, R.; Dubey, D.S.; Singh, J.; Khanna, M.; Pathak, H.; Bhatia, A. Mitigation of Greenhouse Gas Emission with System of Rice Intensification in the Indo-Gangetic Plains. Paddy Water Environ 2014, 12, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, G.; Park, W.; Shin, M.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Yun, D. Effect of SRI Water Management on Water Quality and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Korea. Irrigation and Drainage 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, N.; Kassam, A.; Harwood, R. SRI as a Methodology for Raising Crop and Water Productivity: Productive Adaptations in Rice Agronomy and Irrigation Water Management. Paddy Water Environ. 2011, 9 Sp. Iss. SI MAR, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, C.; Toriyama, K.; Nugroho, B.D.A.; Mizoguchi, M. Crop Coefficient and Water Productivity in Conventional and System of Rice Intensification (SRI) Irrigation Regimes of Terrace Rice Fields in Indonesia. Jurnal Teknologi 2015, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, B.D.A.; Toriyama, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Arif, C.; Yokoyama, S.; Mizoguchi, M. Effect of Intermittent Irrigation Following the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) on Rice Yield in a Famer’s Paddy Fields in Indonesia. Paddy Water Environ 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Yamaji, E.; Kuroda, T. Strategies and Engineering Adaptions to Disseminate SRI Methods in Large-Scale Irrigation Systems in Eastern Indonesia. Paddy Water Environ 2011, 9, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA Manual on Measurement of Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Agricultural; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 1993.

- Sha, C.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Hu, W.; Shen, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, M. Regulation of Methane Emissions in a Constructed Wetland by Water Table Changes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Wehmeyer, H.; Heffner, T.; Aeppli, M.; Gu, W.; Kim, P.J.; Horn, M.A.; Ho, A. Resilience of Aerobic Methanotrophs in Soils; Spotlight on the Methane Sink under Agriculture. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2024, 100, fiae008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, S.; Ohno, H.; Tsuboi, M.; Otsuka, S.; Senoo, K. Identification and Isolation of Active N2O Reducers in Rice Paddy Soil. ISME J 2011, 5, 1936–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouman, B.A.M. Water Management in Irrigated Rice: Coping with Water Scarcity; Int. Rice Res. Inst., 2007; ISBN 978-971-22-0219-3.

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Peng, S.; Castañeda, A.R.; Visperas, R.M. Yield and Water Use of Irrigated Tropical Aerobic Rice Systems. Agricultural Water Management 2005, 74, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, F.; Safitri, R.; Suhaimi, N.S.M.; Miranti, M.; Rossiana, N.; Mispan, M.S.; Anhar, A.; Uphoff, N. Evaluating the Underlying Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms in the System of Rice Intensification Performance with Trichoderma-Rice Plant Symbiosis as a Model System. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, B.I.; Imansyah, A.; Arif, C.; Watanabe, T.; Mizoguchi, M.; Kato, H. SRI Paddy Growth and GHG Emissions at Various Groundwater Levels. Irrigation and Drainage 2014, 63, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziez, A.; Hanudin, E.; Harieni, S. Impact of Water Management on Root Morphology, Growth and Yield Component of Lowland Rice Varieties under the Organic System of Rice Intensification. Journal of Degraded and Mining Lands Management 2018, 5, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, C.; Saptomo, S.K.; Setiawan, B.I.; Taufik, M.; Suwarno, W.B.; Mizoguchi, M. A Model of Evapotranspirative Irrigation to Manage the Various Water Levels in the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) and Its Effect on Crop and Water Productivities. Water 2022, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.K.; Mandal, K.G.; Mohanty, R.K.; Ambast, S.K. Rice Root Growth, Photosynthesis, Yield and Water Productivity Improvements through Modifying Cultivation Practices and Water Management. Agricultural Water Management 2018, 206, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, T.; Yamaji, E. The Effects of Irrigation Method, Age of Seedling and Spacing on Crop Performance, Productivity and Water-Wise Rice Production in Japan. Paddy Water Environ 2010, 8, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.K.; Rath, S.; Patil, D.U.; Kumar, A. Effects on Rice Plant Morphology and Physiology of Water and Associated Management Practices of the System of Rice Intensification and Their Implications for Crop Performance. Paddy and Water Environment 2011, 9, 13–24, Sp. Iss. SI MAR. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwart, S.J.; Bastiaanssen, W.G.M. Review of Measured Crop Water Productivity Values for Irrigated Wheat, Rice, Cotton and Maize. Agricultural Water Management 2004, 69, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Humphreys, E.; Tuong, T.P.; Barker, R. Rice and Water. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press, 2007; Vol. 92, pp. 187–237.

- Geerts, S.; Raes, D. Deficit Irrigation as an On-Farm Strategy to Maximize Crop Water Productivity in Dry Areas. Agricultural Water Management 2009, 96, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, B.O.; Samson, M.; Buresh, R.J. Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Flooded Rice Fields as Affected by Water and Straw Management between Rice Crops. Geoderma 2014, 235–236, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linquist, B.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Adviento-Borbe, M.A.; Pittelkow, C.; van Kessel, C. An Agronomic Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Major Cereal Crops. Global Change Biology 2012, 18, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, A.F.; Boumans, L.J.M.; Batjes, N.H. Emissions of N2O and NO from Fertilized Fields: Summary of Available Measurement Data. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2002, 16, 6-1–6-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, H.; Tewari, A.N.; Sankhyan, S.; Dubey, D.S.; Mina, U.; Singh, V.K. Direct-Seeded Rice: Potential, Performance and Problems - a Review. Current Advances in Agricultural Sciences 2014, 6, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

| Properties | Value |

|---|---|

| Particle density (g/cm3) | 1.96 |

| Total porosity (% volume) | 65.3 |

| Water content (% volume) | |

| pF 1 | 63.3 |

| pF 2 | 46.9 |

| pF 2.54 (Field capacity) | 40.3 |

| pF 4.2 (Permanent wilting point) | 19.6 |

| Permeability (cm/jam) | 8.17 |

| Soil texture (%) | |

| Sand | 23 |

| Silt | 34 |

| Clay | 43 |

| No | Parameters | Season | Unit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |||

| 1 | Max air temperature | 35.9 | 35.9 | 36.2 | oC |

| 2 | Average air temperature | 26.9 | 26.7 | 26.2 | oC |

| 3 | Min air temperature | 20.4 | 20.1 | 20.6 | oC |

| 4 | Relative humidity | 84.6 | 82.7 | 84.5 | % |

| 5 | Average Solar radiation | 13.0 | 12.9 | 12.1 | MJ/m2/d |

| 6 | Average reference evapotranspiration | 3.25 | 2.60 | 2.43 | mm |

| 7 | Total Precipitation | 1211 | 1414 | 1025 | mm |

| Season | Regime | Parameters | Unit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | N2O | GWP* | |||

| 2016 | FL | 173.6 | -1.81 | 4,193 | kg/ha/season |

| WET | 145.1 | 1.34 | 4,283 | kg/ha/season | |

| DRY | 100.7 | 1.33 | 3,082 | kg/ha/season | |

| 2017 | FL | 267.0 | 0.45 | 7,332 | kg/ha/season |

| WET | 153.3 | -0.62 | 3,972 | kg/ha/season | |

| DRY | 118.0 | 0.33 | 3,275 | kg/ha/season | |

| 2018 | FL | 130.2 | -1.26 | 3,172 | kg/ha/season |

| WET | 124.0 | 3.25 | 4,236 | kg/ha/season | |

| DRY | 33.6 | 6.36 | 2,644 | kg/ha/season | |

| Season | Irrigation Regime | Yield (ton/ha) | Irrigation (mm) | ETa (mm) | WPI+P (kg/m3) | WPET (kg/m3) | WUE (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | FL | 4.69 | 498 | 461 | 0.27 | 1.02 | 0.94 |

| WET | 5.19 | 378 | 421 | 0.33 | 1.23 | 1.37 | |

| DRY | 6.00 | 302 | 408 | 0.40 | 1.47 | 1.99 | |

| 2017 | FL | 5.60 | 183 | 378 | 0.35 | 1.48 | 3.06 |

| WET | 6.02 | 153 | 349 | 0.38 | 1.72 | 3.93 | |

| DRY | 6.09 | 145 | 338 | 0.39 | 1.80 | 4.20 | |

| 2018 | FL | 6.51 | 136 | 310 | 0.56 | 2.10 | 4.78 |

| WET | 6.85 | 114 | 295 | 0.60 | 2.32 | 5.99 | |

| DRY | 6.18 | 91 | 280 | 0.55 | 2.21 | 6.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).