1. Introduction

Urban population growth has placed increasing pressure on transportation networks, leading to widespread traffic congestion, particularly in dense city environments. According to projections by the United Nations, an estimated 68 percent of the global population is expected to reside in urban areas by 2050, reinforcing the urgency of developing effective and scalable traffic management solutions [

1]. Traffic congestion contributes to extended travel times and reduced productivity and has adverse effects on air quality, public health, and energy consumption [

2].

Traditional traffic signal control methods, including fixed-time actuated control systems, which adjust their pattern dynamically based on the presence of vehicles, have long been used to manage vehicular flow at intersections. Fixed-time systems operate based on predetermined schedules, which often fail to accommodate variations in real-time traffic demand. Actuated control systems, although more responsive, rely on preset logic triggered by sensor inputs and are limited in adapting to spontaneous fluctuations in traffic volumes [

3]. Adaptive systems like the Sydney Coordinated Adaptive Traffic System can respond dynamically to changing traffic conditions. However, these systems often require extensive sensor infrastructure and are limited in adaptability when network complexity increases [

4].

Recent research has explored the application of learning-based methods to improve traffic signal responsiveness and network-wide efficiency. Reinforcement learning (RL) offers a framework wherein a controller can improve its decision-making over time based on feedback from the traffic environment. One of the most critical aspects influencing the performance of such methods is the reward function, which directly guides the controller’s behavior during actual operation [

5]. A poorly defined reward can lead to suboptimal or undesirable outcomes, whereas a well-structured reward function, in contrast, can promote effective learning and operational efficiency.

We have investigated how the design of the reward function influences the effectiveness of RF-based traffic signal controllers in urban environments. Using the SUMO platform, three different reward formulations with distinct objectives have been implemented and evaluated, namely (1) minimizing vehicle waiting time, (2) reducing queue length, and (3) a weighted-sum version of both. The simulation scenarios include single and connected intersections to assess the impact of each strategy in different real-world settings, including queue propagation effects. The aim is to determine which reward structure is most effective with the given physical constraints under varying traffic conditions, thereby contributing to the development of efficient traffic signal systems for sustainable urban transport.

The use of SUMO enables the construction of detailed intersection models and offers fine-grained access to lane-level vehicle data, including queue lengths and waiting times. Experiments have shown that signal controllers trained through reinforcement learning can reduce congestion and improve throughput compared to fixed-time and actuated systems [

3]. However, a critical factor in the success of any reinforcement learning-based traffic signal control system is the design of its reward function. The reward function defines controller’s goal by quantifying which outcomes are desirable. A poorly constructed reward function may cause the controller to learn behaviors that do not improve or worsen overall network performance. In contrast, a well-designed reward function can guide the learning process toward effective and generalizable control strategies. Metrics commonly used in reward design include vehicle waiting time, queue length, and throughput. Balancing these objectives presents a challenge, especially in larger networks where local improvements may not always lead to global benefits [

2,

3,

11]. Several studies have emphasized the challenges of reward function design in the context of reinforcement learning. For example, Tan et al. [

4] demonstrated that performance could significantly improve when the reward function aligns with specific operational goals and traffic conditions. Karimipour et al. [

11] further explored reward-shaping techniques to enhance training stability and convergence in RL-based traffic control. Multi-agent approaches have also received increasing attention. Alharbi et al. [

10] proposed a decentralized reinforcement learning framework for urban traffic signal control that incorporates multi-objective optimization, showing that agents can coordinate effectively through shared environmental dynamics. In terms of deployment, Müller et al. [

5] identified the transferability of trained controllers as a major barrier, noting that controllers trained under specific conditions may perform poorly when applied to intersections with different configurations or flow patterns. Other research has explored hybrid approaches. Korkmaz et al. [

6] proposed a method that combines a flower pollination algorithm with type-2 fuzzy logic to improve responsiveness. Similarly, Odeh and Nawayseh [

7] developed a fuzzy-genetic hybrid approach that adjusts signal timings based on evolving traffic states. These approaches benefit from fuzzy logic’s transparency and evolutionary computation’s search capabilities. However, these meta-heuristic approaches often require careful hyperparameter tuning and can become complex when extended to larger networks. Aburas and Bashi [

8] introduced a hybrid system combining fuzzy logic and data-driven methods, reporting improved traffic flow efficiency through real-time learning and decision-making. Although hybrid methods can offer improvements in adaptability, many findings support the idea that RL, when well designed, can achieve high levels of performance and robustness, particularly in rapidly changing traffic conditions. Despite these advances, challenges remain in scaling RL-based control systems to large urban networks. Scalability, transferability, and computational demands are key concerns. A controller that performs well on a single intersection may not generalize to multiple intersections with different traffic demands and signal configurations [

5,

10]. Addressing these challenges is essential for practical deployment. This study builds on the existing body of work by focusing specifically on how different reward structures affect performance.

The key contribution of this study is the comparative evaluation of three distinct reward function designs for reinforcement learning-based traffic signal control, tested under consistent conditions using the SUMO platform. The outcomes provide insight into how reward formulation influences learning behavior, traffic delay, and congestion clearance in both simple and interconnected intersection configurations. The findings support the integration of physical constraints, such as queue spillback limits, into RL reward design to improve real-time responsiveness and network stability. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 outlines the simulation environment and reinforcement learning framework.

Section 3 presents the experimental results under each reward strategy.

Section 4 discusses the implications of the findings.

Section 5 concludes the paper and suggests directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

We present a novel RL-based traffic signal control system to improve urban traffic flow and reduce congestion. The proposed approach was implemented and evaluated in SUMO, which supports the creation of detailed traffic scenarios for controlled testing. An RL agent was trained to adjust signal phases in response to changing traffic conditions by selecting actions that yield higher rewards, i.e., improve performance outcomes. Three reward functions were evaluated separately under the same set of simulation settings. The effectiveness of each reward strategy was assessed using two network configurations: a single isolated intersection and a pair of closely spaced intersections. These scenarios were selected to represent different levels of traffic complexity. The remainder of this section details the simulation environment, mechanism of the RL-based controller, reward function design, configuration of the test scenarios, and the evaluation procedure.

2.1. Simulation Environment

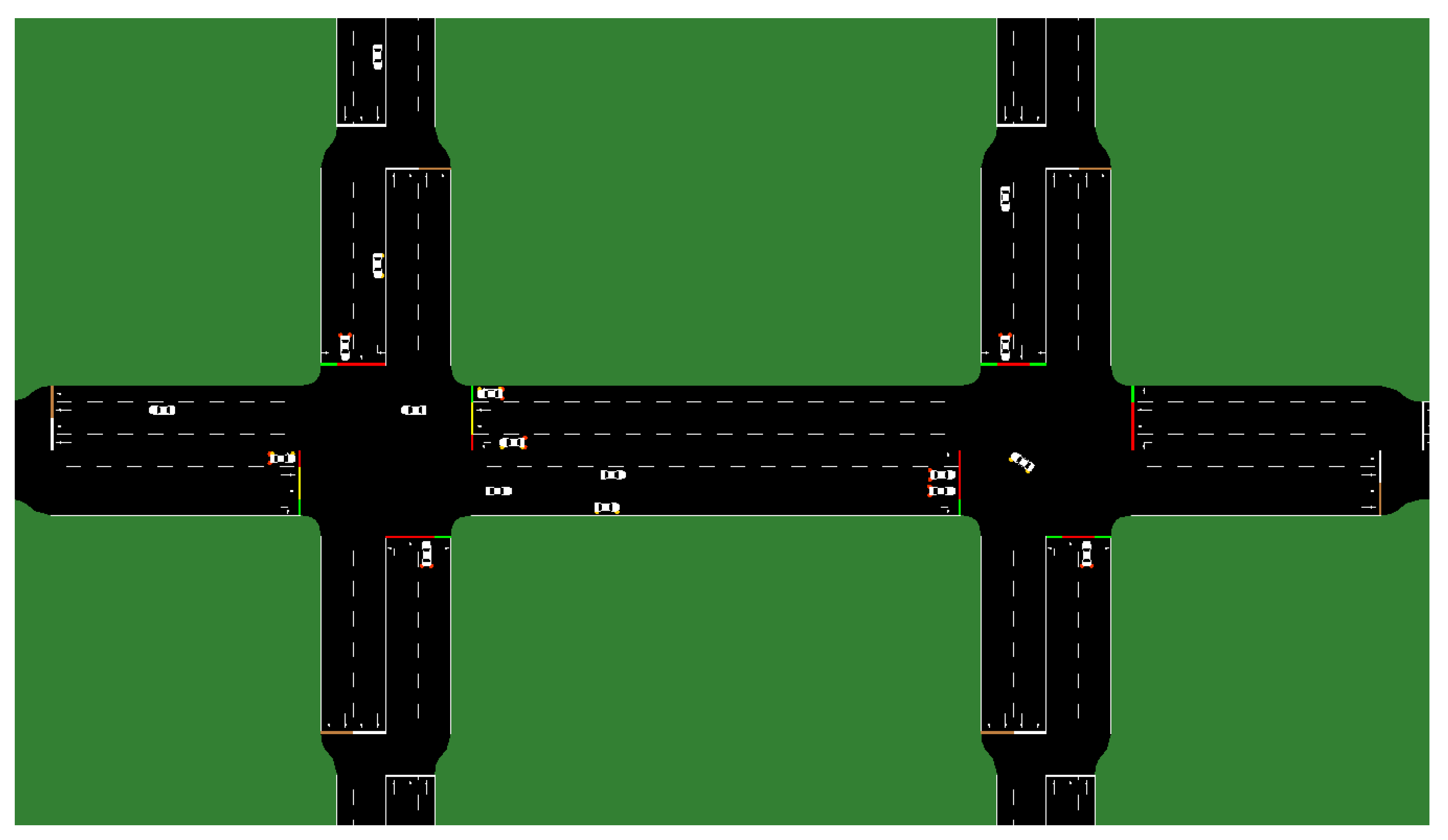

Simulations were carried out using the SUMO platform, an open-source microscopic traffic simulator commonly used in traffic control research. SUMO was selected for its flexibility in modelling realistic traffic conditions, ability to manage large networks, and support for integration with external control systems through the Traffic Control Interface. Version 1.9.2 was employed to ensure compatibility with the RL-based controller that we developed. The simulated network consisted of one or two signalized intersections along a primary road, as shown in

Figure 1. Each intersection included four approaches in the north, south, east, and west directions, with two lanes in each approach. Traffic flows allowed straight movements, lane changing, and turning manoeuvres.

Two adjacent signalized intersections were placed along a main corridor to model typical arterial road conditions. Each node was configured with a four-way layout, enabling the study of queue spillback and phase coordination.

Vehicles were introduced into the network from eight approaches, including the main road and side street entries. Traffic volumes varied between 600 and 1800 vehicles per hour per lane on the main arterial road and between 300 and 900 vehicles per hour per lane on the side streets. These ranges were selected to simulate moderate to heavy urban traffic flow and create a realistic demand imbalance between primary and secondary approaches. In the simulations, the default passenger car profiles in SUMO were used to simulate vehicle behaviors. The profiles incorporated realistic characteristics such as vehicle dimensions, acceleration, deceleration, and maximum speed. Vehicle arrivals and turning behaviors were randomized to increase variability across simulation runs. Vehicles also followed a lane-changing model based on LC2013, incorporating incentive and safety-based decision criteria. Traffic data were collected during the simulation using the Traffic Control Interface (TraCI). Real-time information on lane occupancy, queue length, and vehicle waiting time was passed to an external control program developed in Python version 3.10.

RL controller received traffic state data at regular intervals and decided the next traffic signal phase accordingly. Control decisions were returned to the simulation and applied to the traffic lights. Each simulation scenario was executed in 1000 time steps, representing 1000 seconds of simulated time. To ensure statistical consistency and reduce the impact of stochastic variation, each scenario was repeated ten times using different random seeds to control vehicle generation and route assignment. At the end of each run, key performance indicators were recorded, including average vehicle waiting time, total queue length, and system throughput. These metrics were averaged over the ten runs for comparison. Two distinct traffic network layouts were tested. The first layout included a single isolated intersection. This scenario provided a baseline to evaluate how well the controller could manage basic traffic conditions. The second layout included two intersections placed close to each other along a shared road segment. This configuration enabled analysis of more complex conditions, such as the build-up of queues that extend from one intersection to the next. It also allowed for testing the controller’s ability to prevent queue spillback and alleviate congestion that propagates between intersections.

While the proposed reinforcement learning-based signal control framework assumes access to complete real-time traffic state information, this may not always be practical in real-world applications. The effectiveness of the system depends on the availability of accurate and timely data, including vehicle counts, queue lengths, and delays. This assumption may present a limitation, particularly in environments with limited or unreliable sensing infrastructure. However, recent developments in smart surveillance technologies and Internet of Things (IoT) systems provide a promising foundation for overcoming this constraint. Smart city infrastructure, which includes connected sensors, traffic cameras, and vehicle-to-infrastructure communication, can support continuous data acquisition and transmission at fine temporal and spatial resolutions [

1,

2]. These technologies are becoming increasingly integrated into Intelligent Transportation Systems and offer practical support for the real-time operation of adaptive signal controllers. Nonetheless, future research should address the effects of data uncertainty and explore approaches that maintain performance under partial or delayed observability conditions.

2.1.1. Controller–Simulator Interaction via TraCI

The integration between the RL controller and the SUMO traffic simulator is implemented through the Traffic Control Interface (TraCI), a socket-based API that supports real-time interaction between SUMO and external applications. TraCI allows the controller to retrieve state information from the simulation environment and issue commands to modify simulation parameters during runtime. In this study, the controller was developed in Python. It communicates with SUMO at each simulation timestep using the TraCI Python library. At the beginning of each simulation step, the controller initiates a query to extract traffic state variables from SUMO. These variables include the number of halting vehicles per lane, accumulated waiting times, lane occupancies, and each controlled intersection’s current signal phase state. This raw data is processed into a structured observation vector reflecting the local traffic condition surrounding each signal. The observation is then passed to the RL agent, which uses the encoded traffic state to select an action, typically corresponding to a change in the active signal phase. The selected action is transmitted back to SUMO via TraCI and applied immediately or after a minimum green duration, depending on the simulation parameters. This interaction loop continues until the end of the simulation episode. The seamless data exchange through TraCI enables the controller to influence traffic signal behaviour continuously while adapting to changing vehicle flows. This tight coupling is essential for RL-based control, which requires frequent updates to both policy inputs (observations) and environment outputs (actions and rewards) [

9].

2.1.2. Decentralized Agent Coordination Through Environmental Feedback

In the multi-intersection scenario, the system is designed to operate with a decentralized control architecture, where an independent RL agent manages each traffic signal. Each agent has access only to its local traffic state, including lane-specific vehicle data within its control boundary, and selects actions independently based on its observation space. No direct communication occurs between agents during training or evaluation. Coordination among the agents emerges indirectly through their interaction with the shared traffic environment. For example, a downstream agent’s decision to hold or release traffic can influence the arrival patterns experienced by an upstream intersection. If the downstream signal fails to clear traffic promptly, it can cause queue spillback that affects upstream flow, which alters the reward signals and observations perceived by the upstream agent. Through repeated episodes of interaction and learning, each agent gradually adapts its control strategy to optimize its local performance and accommodate patterns that reflect broader network conditions. This form of decentralized learning is advantageous in urban traffic networks where centralized control may be infeasible due to communication limitations, scalability concerns, or infrastructure constraints. It allows agents to function autonomously, reduces dependency on synchronized data exchange, and supports modular deployment where intersections can be trained and operated independently. Although coordination is not explicitly enforced, the agents’ shared dependence on the environment creates coupling through which cooperative behaviour can emerge over time.

2.1.3. Simulation Scenarios

Each simulation run lasted 100,000 time steps, equivalent to 100,000 seconds of simulated time. Every experiment was repeated ten times using different random seeds to account for stochastic variability. To support comparative analysis, metrics including average waiting time, total queue length, and system throughput were recorded and averaged across all repetitions. The agent was trained separately under each network configuration for all three reward function structures. Policy training was performed from scratch in each case to isolate the effects of the reward design. Final evaluations were conducted using the same traffic input parameters to ensure consistent conditions for all comparisons.

This dual-scenario simulation approach enabled a robust assessment of how reward function design affects controller performance under both simple and interconnected traffic environments, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the scalability and generalisability of reinforcement learning-based signal control strategies.

2.2. Reinforcement Learning Framework

The traffic signal control problem was modelled as an RL task, where an agent interacts with the traffic environment and learns to optimize traffic flow through repeated experience. The RL framework in this investigation is comprised of three core components: state space, action space, and reward function. Each component was designed to reflect the operational characteristics of signalized intersections and support effective control policy development.

State space provided the agent with real-time traffic information required for decision-making. At each decision step, the state was represented as a vector containing the queue lengths of all incoming lanes. In the single-intersection scenario, the agent independently observed the queue lengths for the main and side roads. The state vector included queue length data from both intersections for the two-intersection configuration. Queue length was selected as the primary state variable due to its direct relationship with congestion levels and traffic delay, making it an effective indicator for signal control.

Action space defines the available control actions. The agent selected one traffic signal phase from a predefined set at each decision point. These phases included combinations such as permitting main road through movements, allowing side-road entry, or activating protected turning signals. Once selected, a phase was held for a minimum green duration to ensure safe transitions and stable vehicle movements. This constraint prevented unrealistic phase-switching behaviour and helped maintain intersection flow continuity. The reward function provided numerical feedback based on traffic performance at each time step. Three distinct reward structures were implemented and tested, each aligning with a specific traffic management objective.

2.2.1. Waiting Time-Based Reward

This function,

r1, represents the penalty, which is a function of the total accumulated waiting time of all vehicles,

N, in the network, and it is expressed as

Here, wi(t) denotes the waiting time of vehicle i at time step t. This component encouraged the agent to reduce the overall delay by prioritizing actions that minimize the time vehicles spend stationary at intersections. The negative sign indicates that it is a penalty function instead of a reward.

2.2.2. Queue Length-Based Reward

This function,

r2, represents another penalty, which is a function of the number of vehicles forming queues on incoming lanes,

M, and it is expressed as

Here, qi(t) is a binary number that represents the presence (i.e., 1) or absence (i.e., 0) of vehicle i in a queue at time t. Vehicles were considered queued if they were stationary or travelling below 0.1 m/s, which aligns with the threshold commonly used in SUMO-based traffic control research to indicate queuing behaviour. This component focused on clearing congestion and maintaining continuous flow. As before, the negative sign indicates that it is a penalty function instead of a reward.

2.2.3. Weighted Combination Reward

To balance both objectives, a third component was implemented, combining waiting time and queue length with equal weight:

where

+ β =1 and 0<= α, β <=1. For simplicity, in this work, α = β =0.5.

This approach aimed to achieve a compromise between delay minimization and congestion control. In the later section, we will further investigate the effect of weight combinations on the agents’ performance. To stabilize learning and reduce correlations in the training data, an experience replay buffer was used. An experience replay buffer was used with a capacity of 10,000 transitions to stabilise learning and decorrelate training samples. Such a capacity was selected to balance memory efficiency with the need for varied experience replay in a tabular Q-learning setting. The learning algorithm implemented in this study was Q-learning. The agent maintained a value function that estimated the expected cumulative reward for each state–action pair. The Q-values were updated according to the Bellman equation, which is expressed as

Here, Q(s, a) is the estimated value of action a in state s, r is the reward/penalty received, s′ is the next state, α is the learning rate, and γ is the discount factor determining future rewards’ importance. The term max Q(s′, a′) reflects the best-estimated reward available from the next state. Through this process, the agent learned an adaptive signal control policy capable of responding to real-time traffic conditions without reliance on predefined schedules or manually designed control logic.

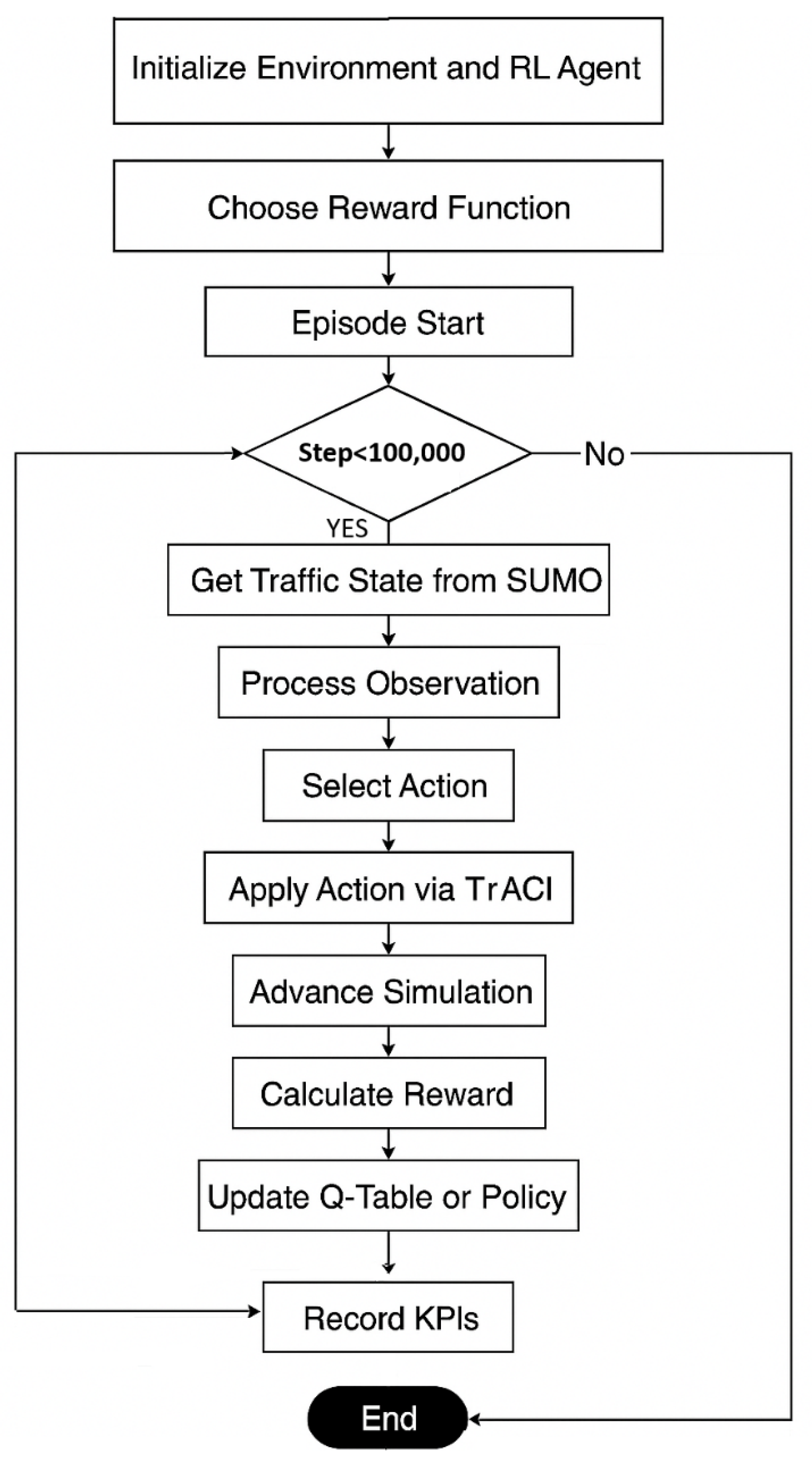

The flowchart in

Figure 2 illustrates the sequential process implemented for training and evaluating the RL-based traffic signal controller. The procedure begins by initializing the simulation environment and the RL agent and selecting one of the three reward functions under investigation.

Once the reward function is selected, the training process proceeds across multiple episodes. Within each episode, the agent interacts with the SUMO simulation environment at each time step by first retrieving the current traffic state via TraCI. This state is processed into a structured observation, which the agent uses to select a signal control action. The chosen action is then applied through TraCI, the simulation advances by one step, and a reward is calculated based on the observed outcome. The agent then updates its Q-table using the received feedback. Since the policy used to select actions is derived directly from the Q-table, any change in Q-values implicitly updates the agent’s policy. This loop continues until the episode concludes. Upon completion of each episode, key performance indicators (KPIs) such as average waiting time, total queue length, and throughput are recorded for evaluation. This framework enables consistent testing and comparison of reward structures under identical simulation conditions.

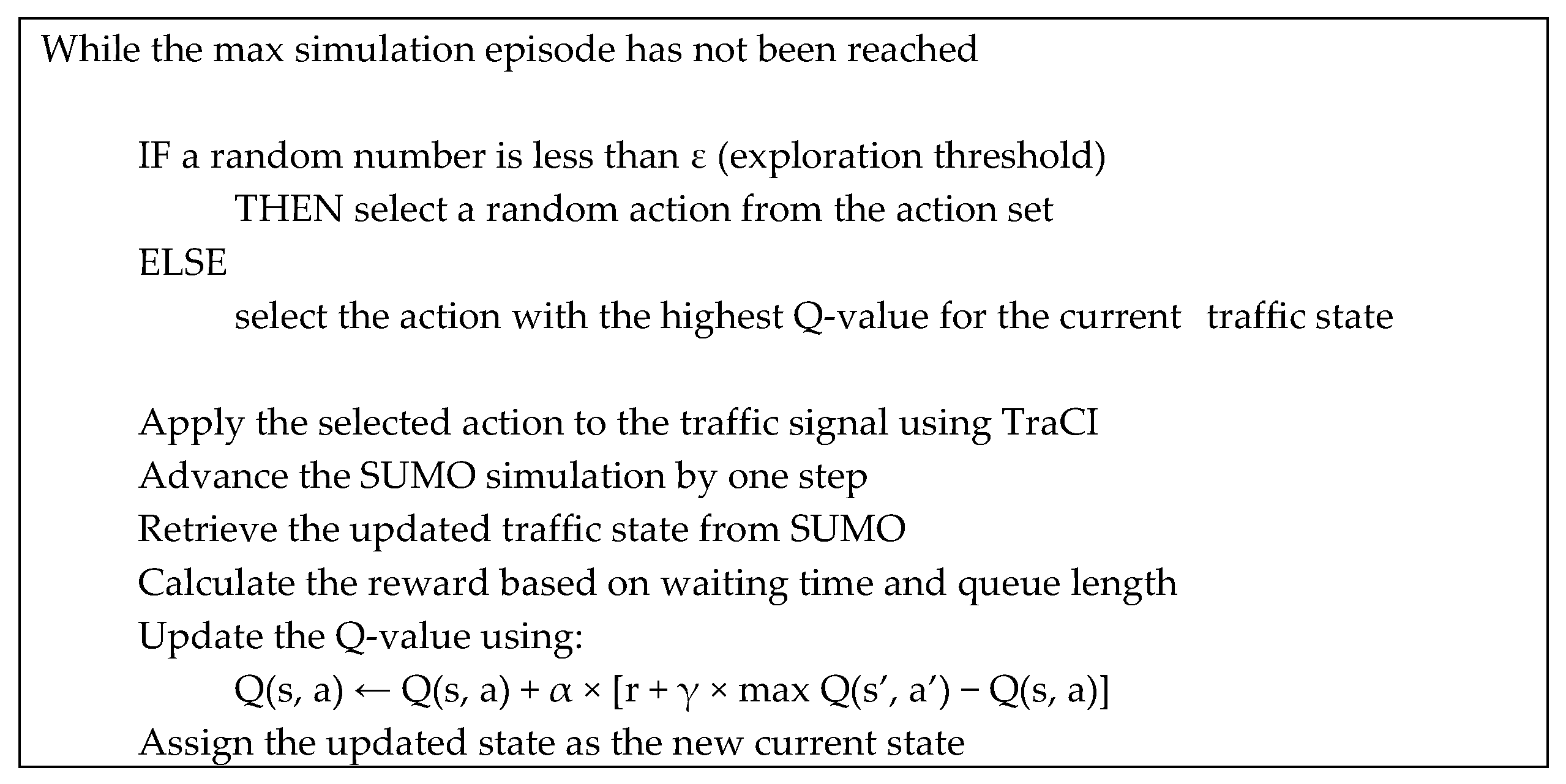

The pseudocode presented below illustrates core operations performed by the RL agent at each simulation time step. Logic includes action selection using an ε-greedy strategy, simulation interaction through TraCI, reward calculation, and Q-value update.

Listing 1.

The pseudocode snippet illustrates agent action selection and Q-value update.

Listing 1.

The pseudocode snippet illustrates agent action selection and Q-value update.

2.3. Reward Function Variations

As already described, three distinct formulations were tested during training and assessment to evaluate how reward function design influences learning dynamics and traffic control performance. The first formulation aimed to reduce delay by penalizing the cumulative waiting time of all vehicles in the network, as defined in (1). This encouraged the agent to minimize vehicle time spent in stationary or slow-moving conditions, improving intersection service levels. The second reward, defined in (2), focused on reducing congestion by penalizing the number of queued vehicles, which promoted smoother traffic flow along inbound lanes. The third structure, described in (3), used a weighted combination of both objectives. While initial tests applied equal weighting, further experimentation showed that a higher weight on queue length (α = 0.99) and a lower weight on waiting time (β = 0.01) resulted in more stable learning, particularly under heavy traffic conditions. This configuration was chosen to mitigate queue spillback while still discouraging prolonged delays.

Each reward formulation was evaluated independently, with the reinforcement learning agent trained from an uninitialized state using identical traffic conditions and simulation parameters. The training was continued until policy performance stabilized across episodes. Final evaluations were conducted under consistent conditions to enable direct comparison of learning outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Performance Under Waiting Time Reward

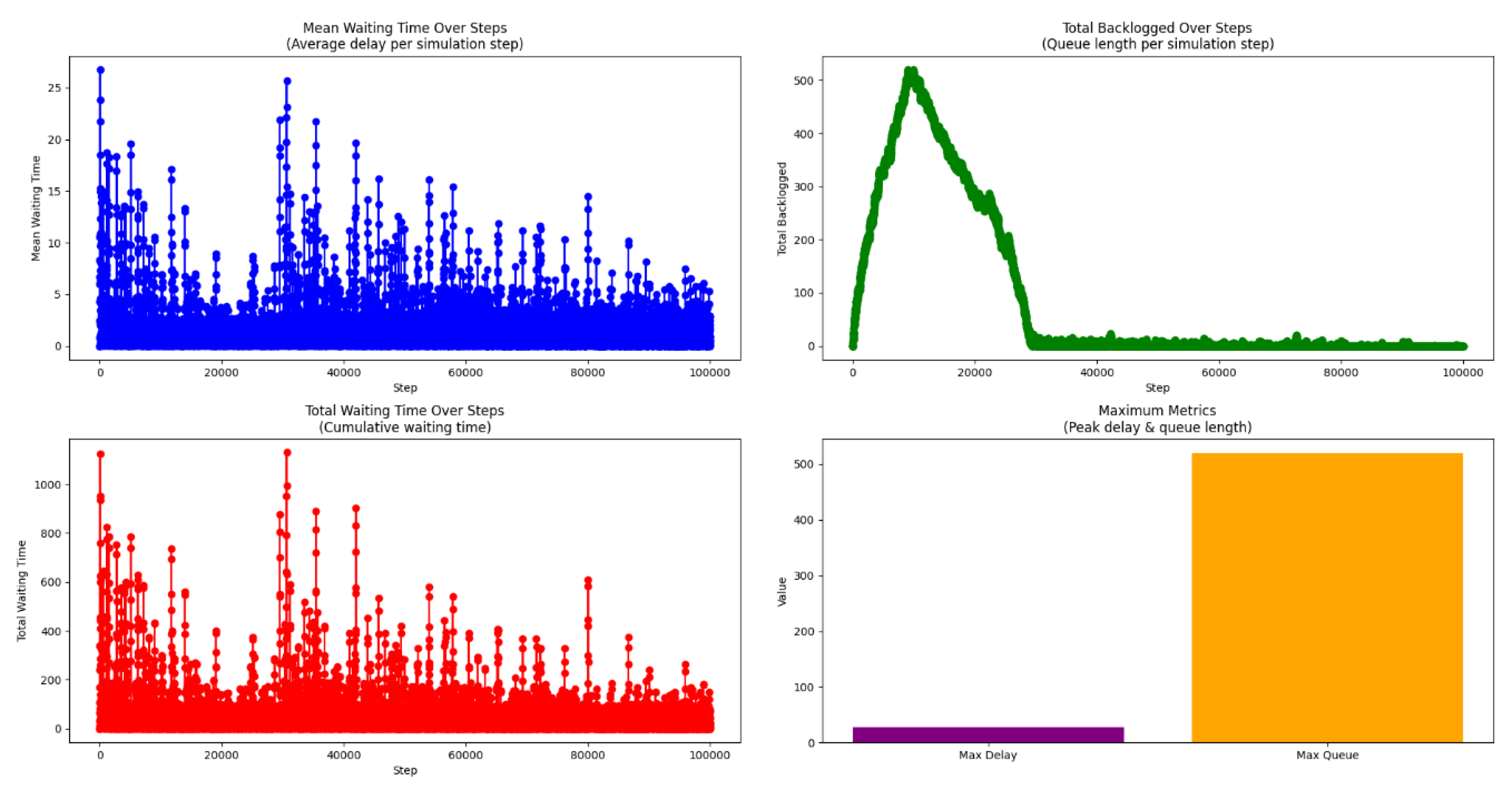

The first set of experiments evaluated the RL agent trained exclusively with the waiting time-based reward function, as defined in (1). This configuration assessed the agent’s ability to minimize cumulative vehicle delays at the intersection.

Figure 3 presents four performance metrics throughout training. The top-left plot shows the mean waiting time per simulation step, which reveals a downward trend despite some fluctuations. The agent successfully reduced the average waiting time from values exceeding 20 seconds to consistently below 5 seconds, demonstrating effective learning and policy adaptation. The top-right plot illustrates the total number of backlogged vehicles across steps. An initial increase, peaking at around 500 vehicles, was followed by a gradual decline, suggesting that queue management improved as a secondary effect of targeting delay minimization. The bottom-left plot displays cumulative waiting time over the simulation period. A consistent reduction confirms that the learned policy effectively lowered system-wide delay. The bottom-right bar graph summarizes peak metrics. While high queue lengths were observed early in training, the final policy achieved significant delay reductions, showing the benefit of targeting waiting time directly.

Overall, this reward structure led to robust improvements in delay-related metrics, indicating that reinforcement learning agents can effectively reduce vehicle waiting times when this objective is prioritized.

3.2. Performance Under Queue Length Reward

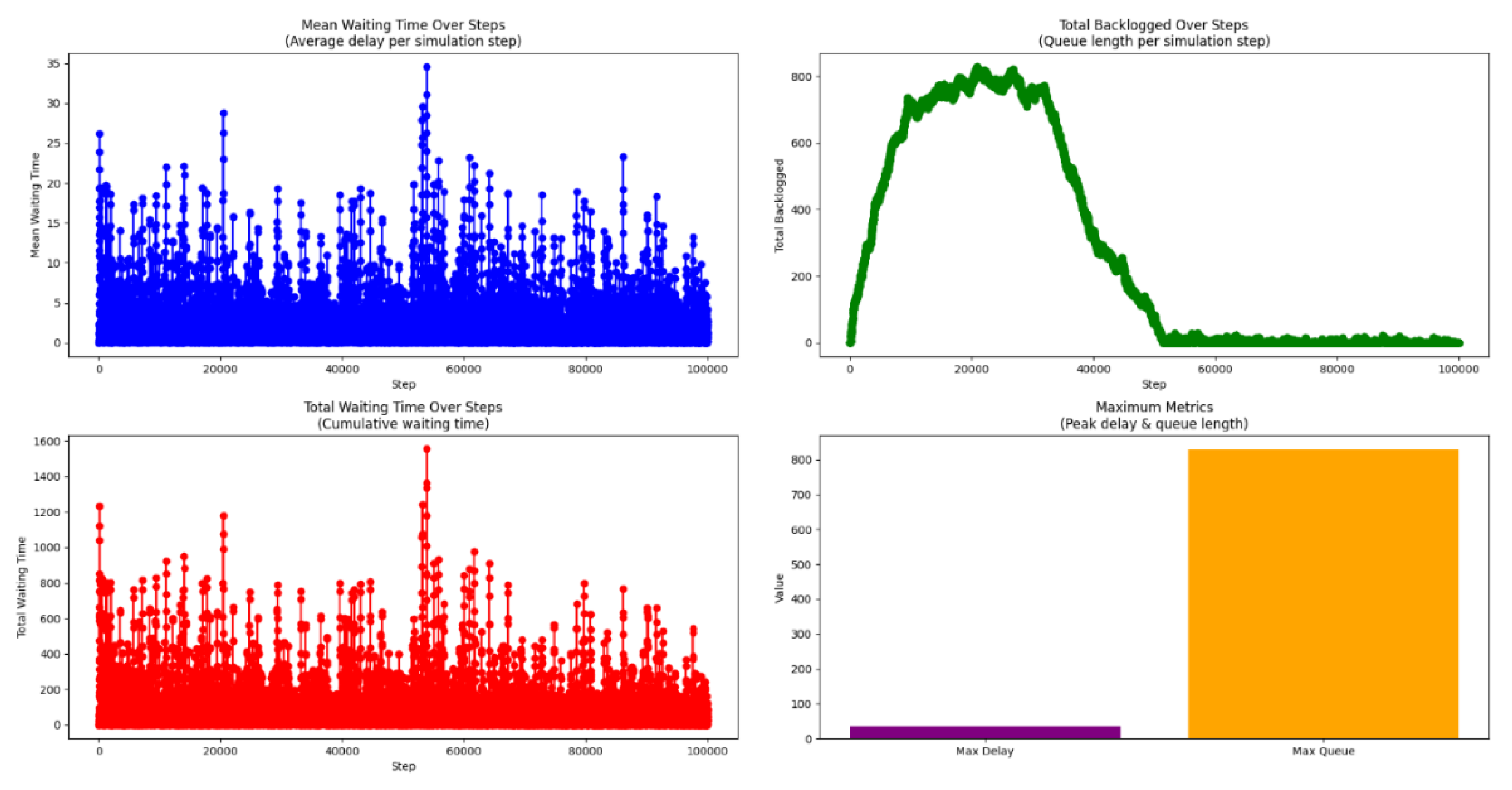

The agent was trained with a reward function targeting queue length reduction in the second experiment set, as (2) defined. The objective was to manage congestion by minimizing the number of queued vehicles at each step. The top-left plot of

Figure 4 shows the mean waiting time per step. Although some reduction is visible, the improvements are less stable and remain higher overall than the previous reward. This observation suggests that minimizing queue size does not necessarily reduce individual vehicle-level delay. The top-right plot reveals a sharp increase in backlog during early training, with a peak near 800 vehicles. However, the agent later succeeded in reducing the queue length to close to zero, typically after 50,000 steps. The bottom-left plot highlights the variability in cumulative waiting time. While the agent effectively reduced queues, it did not consistently minimize total delay. The bottom-right graph shows that maximum vehicle delays remained elevated, although maximum queue lengths were greatly reduced. This finding further confirms the trade-off between congestion clearance and delay management.

In summary, while the queue-based reward function improved traffic fluidity, it was less effective in reducing waiting time, reinforcing the need to balance multiple objectives in traffic signal optimization.

3.3. Performance Under Combined Reward

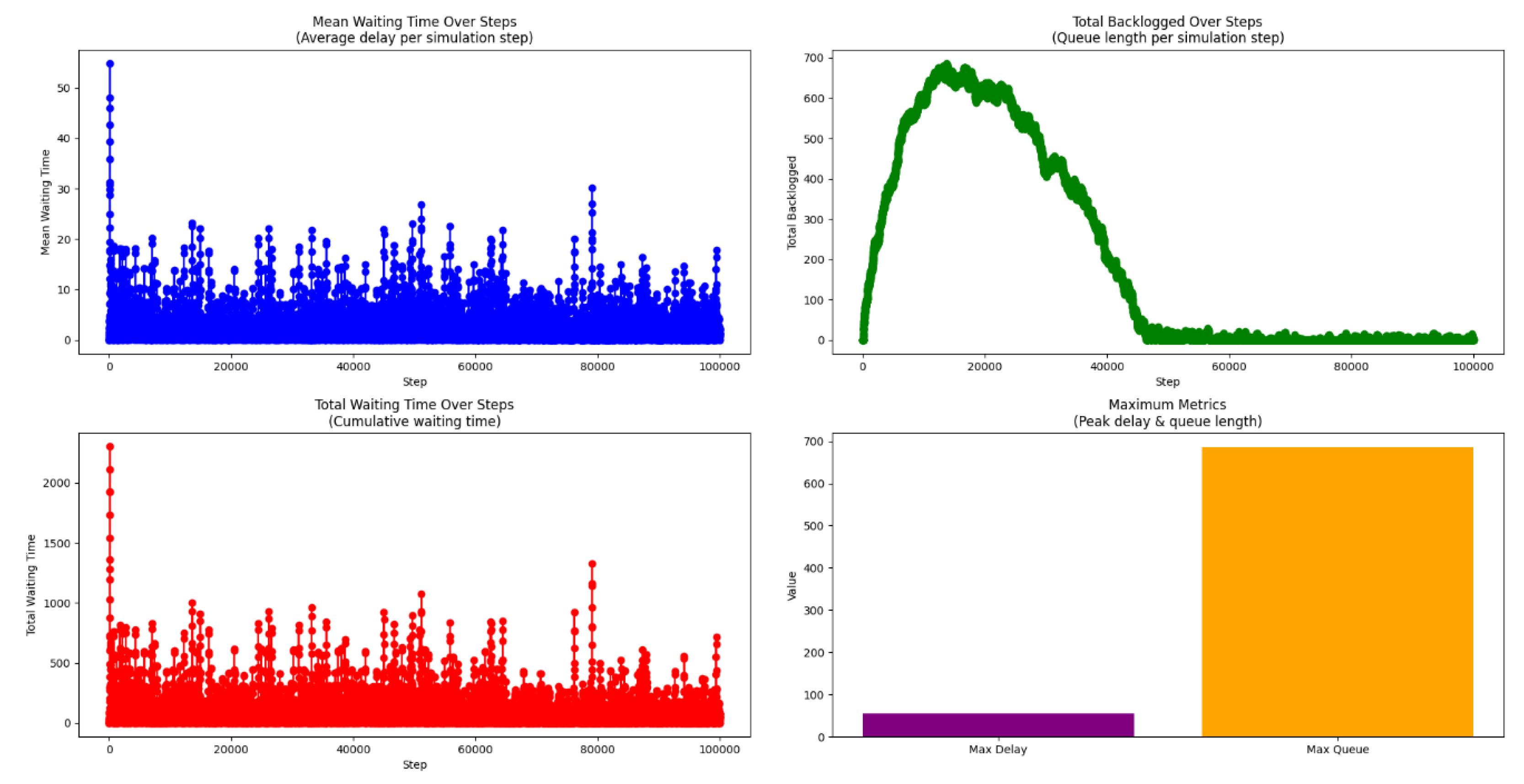

The third experiment tested the combined reward structure, defined by equation (3), which assigns equal weight to waiting time and queue length. As shown in

Figure 5, the mean waiting time (top-left) decreased over time but with more fluctuations compared to single-objective experiments. This outcome indicates that balancing two objectives can make learning less stable but effective overall. The top-right plot shows the evolution of queue length. After peaking at around 700 vehicles, the agent progressively reduced the backlog, achieving a steady state similar to the queue-focused agent. The cumulative waiting time (bottom-left) remained between the extremes of the previous two experiments, reflecting a compromise between the optimization targets. The bottom-right graph reveals that both delay and queue peaks were managed effectively, although not minimized as aggressively as in single-objective cases.

This balanced reward produced consistent overall improvements in traffic control metrics, albeit with slightly longer training convergence.

3.4. Comparative Analysis

Comparative evaluation of the three reward structures provides insight into how different design objectives influence learning outcomes and operational performance. A waiting time-based reward structure achieved the greatest reduction in average vehicle delay. However, queue length control was inconsistent, particularly in the early training stages. Queue length-based reward led to near-complete congestion clearance but did not translate into equivalent reductions in vehicle waiting time. This result suggests that vehicles moved more freely but still experienced periods of inactivity. The combined reward strategy achieved a practical middle ground. While not outperforming the single-objective approaches in any one metric, it produced a stable and well-rounded control method suitable for complex environments requiring multiple priorities to be met. These findings suggest that multi-objective reward design is critical in achieving balanced and generalizable traffic management solutions through RL.

Table 1.

Comparative performance of reinforcement learning-based traffic signal controllers under different reward functions.

Table 1.

Comparative performance of reinforcement learning-based traffic signal controllers under different reward functions.

| Reward Function |

Mean Waiting Time |

Mean Queue Length |

Total Waiting Time |

Maximum Delay |

Maximum Queue Size |

| Waiting Time Only |

Low |

Moderate |

Low |

Lowest |

Moderate |

| Queue Length Only |

High |

Very Low |

High |

High |

Lowest |

| Combined Reward |

Moderate |

Low |

Moderate |

Lower than Queue Only |

Low |

4. Discussion

We have investigated how the design of reward functions affects the performance of reinforcement learning-based traffic signal control in urban environments. Three formulations were tested using the SUMO simulation platform: minimizing vehicle waiting time, reducing queue length, and combining both objectives in a weighted structure. The evaluation was conducted across isolated and coordinated intersection layouts to reflect different levels of traffic complexity.

In contrast to the queue-length-only reward function, which was shown to cause queue spillback and instability under variable traffic conditions, the combined reward function exhibited more reliable behavior. By incorporating both queue length and waiting time, the controller avoided excessive throughput prioritization at the expense of delay management. During testing, the combined reward structure maintained lower maximum queue lengths while preserving reasonable delay levels. This resulted in fewer instances of intersection blockage and sustained network throughput, even under fluctuating demand. When traffic patterns changed unexpectedly, the controller trained with the combined reward showed greater resilience and faster recovery compared to the single-objective configurations. These results suggest that the proposed reward design behaves differently and more robustly under real-world conditions, making it a more practical choice for adaptive traffic signal control in complex urban settings.

Single-objective reward structures demonstrated strong results for their specific targets but lacked adaptability under more complex conditions. In contrast, the combined reward function achieved more balanced results across performance metrics. Assigning greater weight to queue length and a smaller weight to waiting time improved learning stability and responsiveness, particularly under high traffic loads. This shows the importance of designing reward functions that reflect both local and system-wide traffic goals.

The parameters of the combined reward function were tuned through experimentation. A configuration with 0.99 weight on queue length and 0.01 on waiting time was found to effectively prevent queue spillback, which occurs when queues from one intersection block the entry to another. In our tests, this weighting helped maintain throughput and reduced maximum queue lengths, especially during peak traffic.

When queue spillback did occur, key indicators such as average waiting time and throughput were negatively affected. The controller’s actions, when unable to prevent spillback, led to network saturation and lower efficiency. These cases revealed the critical need for active queue monitoring and timely intervention.

The approach assumes real-time availability of detailed traffic information, including lane-level occupancy, queue lengths, and signal states. This is a limitation for current deployment, as such data requires advanced infrastructure. However, developments in smart sensors and connected vehicle technologies suggest this will become more feasible in smart city environments.

Another constraint is that the trained controller may need adjustment when applied to a new traffic network. While the weighted reward structure offered generalizable performance, it may not respond ideally to unfamiliar conditions without further training. This supports the use of pre-training in simulation, followed by on-site refinement.

Additionally, the response time of the system under sudden surges in traffic demand presents an operational challenge. If a large volume of vehicles enters the network unexpectedly, such as after a public event or during an incident reroute, the controller may temporarily revert to behavior similar to early-stage learning. This adaptation period, although brief, may result in localized congestion and reduced KPI performance. Designing mechanisms to detect and react rapidly to such anomalies could improve system resilience.

This study contributes to the broader understanding of traffic signal optimization using reinforcement learning. Properly weighted multi-objective rewards can support more stable and effective control policies in variable traffic environments. Future work should investigate adaptive reward weighting, controller transferability, and real-time system integration to support practical deployment.

5. Conclusion

Future research should extend this framework to larger, more complex multi-agent traffic networks. A key direction is to evaluate the controller’s ability to generalize across varying traffic conditions and network layouts, which includes testing whether a policy trained in one intersection configuration can be applied to a different layout without retraining. Such analysis would offer further insight into the robustness and adaptability of the proposed approach. The practical feasibility of real-time deployment also requires examination. Future studies should assess the computational requirements for policy execution, the response time of the control system, and the frequency with which the policy needs to be updated under live operational conditions. These aspects are critical for transitioning from simulation to real-world application. Further investigations may focus on the system’s performance under uncertain and incomplete information, including sensor inaccuracies, partial observability, and unexpected disruptions. The effectiveness of reward formulations that adjust based on changing traffic conditions should also be explored, as this may improve the controller’s responsiveness and stability. Lastly, implementation in established traffic management environments of the Sydney Coordinated Adaptive Traffic System (SCATS) and validation using hardware in the loop testing would strengthen the practical relevance of the proposed method and support its integration into urban transport systems.

References

- Tan, J.; Yuan, Q.; Guo, W.; Xie, N.; Liu, F.; Wei, J.; Zhang, X. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Traffic Signal Control Model and Adaptation Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 8732. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Kreidieh, A.; Parvate, K.; Vinitsky, E.; Bayen, A.M. Flow: Deep Reinforcement Learning for Control in SUMO. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.15920. [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Widmer, J.; Djukic, T. Towards Real-World Deployment of Reinforcement Learning for Traffic Signal Control. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.15121. [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M.; Cakiroglu, M. A Hybrid Traffic Controller System Based on Flower Pollination Algorithm and Fuzzy Logic. Sensors 2024, 24, 1568. [CrossRef]

- Odeh, S.M.; Nawayseh, K. A Hybrid Fuzzy Genetic Algorithm for an Adaptive Traffic Signal System. Jordanian Journal of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering 2015, 9, 73–78.

- Aburas, A.A.A.; Bashi, A.B. Optimising Traffic Flow with Fuzzy Logic and Machine Learning. Zenodo 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zahwa, F.; Cheng, C.-T.; Simic, M. Novel Intelligent Traffic Light Controller Design. Machines 2024, 12, 469. [CrossRef]

- Zahwa, F.; Simic, M.; Cheng, C.-T. Fuzzy-Based Traffic Light Control Strategy: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. In Big Data Analytics and Data Science; Bhateja, V., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Vol. 1106; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 53–63. [CrossRef]

- Wegener, A.; Piórkowski, M.; Raya, M.; Hellbrück, H.; Fischer, S.; Hubaux, J.-P. TraCI: An Interface for Coupling Road Traffic and Network Simulators. In Proceedings of the 11th Communications and Networking Simulation Symposium (CNS), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 14–17 April 2008; pp. 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.; Alqahtani, H.; Muthanna, A.; Alsubhi, K.; Alzahrani, B. Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning for Urban Traffic Signal Control: A Multi-Agent Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3219. [CrossRef]

- Karimipour, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yu, T. Reward Shaping Techniques in Reinforcement Learning-Based Traffic Signal Control. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8019. [CrossRef]

- Aldakkhelallah, A.A.A.; Shiwakoti, N.; Dabic, T.; Lu, J.; Yii, W.; Simic, M. Development of New Technologies for Real-Time Traffic Monitoring. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2681, 020080. [CrossRef]

- Aldakkhelallah, A.A.A.; Shiwakoti, N.; Dabic, T.; Lu, J.; Yii, W.; Simic, M. Public Opinion Survey on the Development of an Intelligent Transport System: A Case Study in Saudi Arabia. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2681, 020089. [CrossRef]

- Aldakkhelallah, A.A.A.; Simic, M. Autonomous Vehicles in Intelligent Transportation Systems. In Human Centred Intelligent Systems; Zimmermann, A., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C., Schmidt, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 185–198.

- Todorovic, M.; Aldakkhelallah, A.; Simic, M. Managing Transitions to Autonomous and Electric Vehicles: Scientometric and Bibliometric Review. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 314. [CrossRef]

- Aldakkhelallah, A.; Alamri, A.S.; Georgiou, S.; Simic, M. Public Perception of the Introduction of Autonomous Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 345. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Simic, M. Transition to Electric and Autonomous Vehicles in China. In Human Centred Intelligent Systems; Zimmermann, A., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 111–123.

- Liang, X.; Du, X.; Wang, G.; Han, Z. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Network for Traffic Light Cycle Control. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2020, 69, 386–395.

- Van der Pol, E.; Oliehoek, F.A. Coordinated Deep Reinforcement Learners for Traffic Light Control. Proceedings of the NIPS Workshop on Learning, Inference and Control of Multi-Agent Systems, 2016.

- Gao, J.; Shen, Y.; Liu, J.; Ito, M. Adaptive Traffic Signal Control: Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm with Experience Replay and Target Network. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.02755. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lv, Y.; Wang, F.Y. Traffic Signal Timing via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2016, 3, 247–254. [CrossRef]

- El-Tantawy, S.; Abdulhai, B.; Abdelgawad, H. Multiagent Reinforcement Learning for Integrated Network of Adaptive Traffic Signal Controllers (MARLIN-ATSC): Methodology and Large-Scale Application on Downtown Toronto. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2013, 14, 1140–1150. [CrossRef]

- Mannion, P.; Duggan, J.; Howley, E. An Experimental Review of Reinforcement Learning Algorithms for Adaptive Traffic Signal Control. Springer International Publishing, Autonomic Road Transport Support Systems, 2016; pp. 47–66. [CrossRef]

- Genders, W.; Razavi, S. Using a Deep Reinforcement Learning Agent for Traffic Signal Control. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.01142. [CrossRef]

- ei, H.; Zheng, G.; Yao, H.; Li, Z. IntelliLight: A Reinforcement Learning Approach for Intelligent Traffic Light Control. Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2018; pp. 2496–2505. [CrossRef]

- Nishi, T.; Chakraborty, S.; Chakraborty, P. A Reinforcement Learning Approach for Signal Timing of Urban Traffic Network. Transportation Research Record 2020, 2674, 160–172.

- Chu, T.; Wang, J.; Codecà, L.; Li, Z. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Large-Scale Traffic Signal Control. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2020, 21, 1086–1095. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).