Introduction

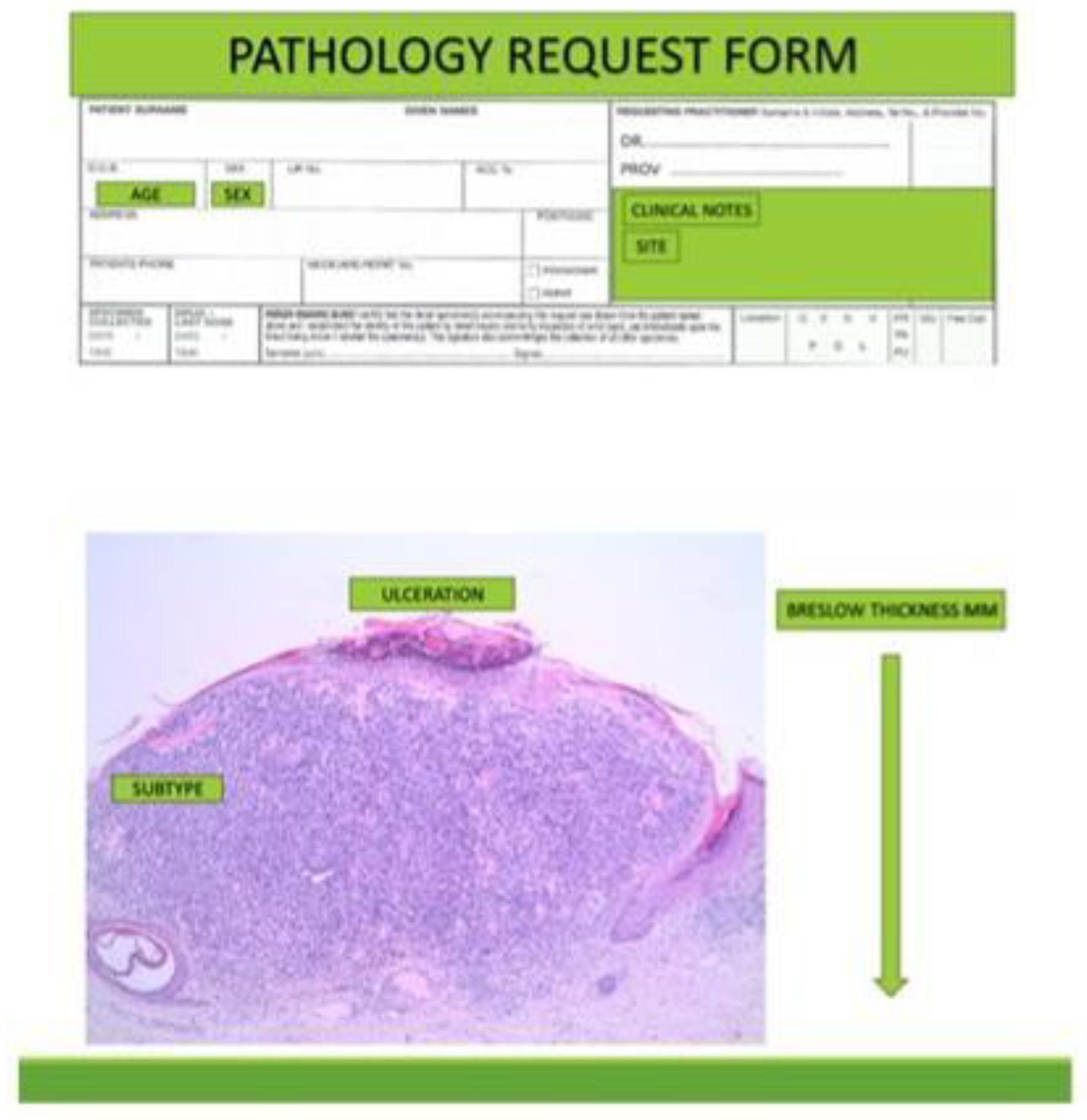

The pathology report communicates information to the clinician gathered from the biopsy for planning further management of the patient. There has been variability in the information provided in pathology reports, both in the information provided and from inter-observer variability in interpretation of parameters. Pathologists’ reporting styles vary in their inclusion of descriptive reports, synoptic reports or a combination of both.[

1,

2] Regardless, essential data must be included.

To consolidate such reporting variability, recommendations for standardisation of reports were introduced, including those by the Royal College of Pathologists (RCPath) in 2002.[

3] The RCPath format has undergone several revisions, the latest being in 2019, which is currently undergoing further revision.[

4] The RCPath document includes recommendations for laboratory handling of skin specimens and outlines information that should be included in the report.

The macroscopic specimen description should include the type of biopsy or excision, its dimensions, including thickness, and a description and measurements of any visible lesion. Additional information should include patient demographics and anatomic site.

Inclusion of clinical photographs and/or dermoscopic images of the lesion can be diagnostically helpful in improving clinicopathological correlation.[

5] Information provided in a report should be relevant to the clinician in formulating further management of the patient based on scientific evidence.

Breslow Thickness

BT is the most accurate prognostic predictor of melanoma[

7] applies to primary tumors. It is the measurement from the top of the epidermal granular layer to the deepest melanoma cell in the dermis or fat. If the thickest part of the tumor is ulcerated, the measurement is taken from the base of the ulcer to the deepest melanoma cell.

In a polypoid melanoma, BT is the tumor thickness measured perpendicular to the skin surface across the largest diameter of the polypoidal projection.[

8]

A recent study found that BT was not associated with the diameter of melanoma.[

6] Importantly, the radial size of melanoma in situ is not prognostically relevant.[

6]

Extension along adnexa, nerves or vessels are not used in determining BT.[

8] Periadnexal involvement that extends more deeply than the thickness of the main tumor does not worsen clinical outcomes overall.[

9]

BT correlates with recurrence rate, with a progressive increase in the rate of local recurrence with each 1.0 mm increment of BT, with overall rates of recurrence of 2.3% for melanomas 1.0-2.0 mm in BT, 4.2% for those 2.01-3.0 mm BT and 11.7% for those 3.01-4.0 mm BT.[

10] The progressive relationship between increasing BT and decreasing survival is lost in patients with ultrathick melanomas, defined as Breslow values of 15 or more millimetres.[

11]

Clark's level (CL) of melanoma is no longer included in staging criteria. Clark’s level describes the degree of melanoma invasion into the papillary dermis, reticular dermis or fat. Although CL and BT both describe the vertical depth of melanoma invasion, on multivariate analysis it is the thickness in mm, not the degree of tissue layer invasion, that provides prognostic significance.[

12] CL is also more subjective than BT and thus less reproducible.[

13] Nevertheless, some authors still retain CL in reporting.[

14]

ADNEXAL AND PERIADNEXAL EXTENSION

Although any in-situ component may extend vertically along adnexal epithelium, including hair follicles and acrosyringia, it is still considered to be in-situ melanoma and is not included in Breslow measurements.

Periadnexal extension is growth of the melanoma immediately adjacent to adnexal structures within the adventitial or extra-adventitial dermal tissue. Although this extension may be greater than the Breslow depth of invasion into dermal stroma, it is also not included in determining BT. One study found that the incidence of periadnexal extension deeper than the BT was 1.5%, but did not increase the risk of death or recurrence.[

9]

Clinical Indicators: Patient Age, Sex and Site of Melanoma

Patient age, sex and anatomic site of the melanoma are important prognostic indicators. Patient age is second to BT as a prognostic indicator, and patient sex is also included as a prognostic factor in BAUSSS biomarker.[

7]

Ulceration

Ulceration is the third most important prognostic factor.[

7] Ulceration is defined as a full thickness loss of epidermis and basement membrane, with evidence of host response, including fibrosis, inflammation and thinning, effacement or reactive hyperplasia of the surrounding epidermis.[

15] Ulceration may be due to either tumor cells infiltrating and eroding the epidermis (infiltrative type) or expansile (nodular) growth without epidermal invasion that stretches the epidermis, thinning and disrupting it (attenuative type).[

16]

Consumption of the epidermis, microscopically seen as thinning of the epidermis, most likely precedes ulceration. This is supported by its presence at the edge of ulcers.[

17] Consumption of the epidermis is significantly associated with an increased BT and histological type of melanoma, and is most common in superficially spreading melanoma and age over 50 years. There is no correlation of consumption with an increased inflammatory response.[

17,

18]

The extent and type of tumoral ulceration provides more accurate prognostic information and should be reported, rather than reporting the mere presence or absence of ulceration. Excessive ulceration, defined as more than or equal to 70% of total tumor diameter, is found to be an independent predictor of poor survival compared with minimal to moderate ulceration of less than 70%.[

19] The presence of extensive ulceration is associated with a worse prognosis.[

20]

Tumor ulceration must be differentiated from traumatic ulceration, as the latter is prognostically irrelevant. Clues to traumatic ulceration include sharp demarcation with "squared off" edges and underlying wedged-shaped granulation tissue.[

16]

Risk factors for ulceration include the site of the primary melanoma. In one study the recurrence rate was 1.1% on the proximal extremity, 3.1% on the trunk, 5.3% on the distal extremity and 9.4% on the head and neck. In all sites, the presence of ulceration was the greatest risk factor, with recurrent rates of 1.1% for non-ulcerated and 6.6% for ulcerated melanoma is on the trunk and proximal extremity, and 2.1% 4 non-ulcerated and 16.2% for ulcerated melanoma is on the distal extremity or head and neck area.[

21]

Subtype of Melanoma

The traditional melanoma classification has been supplanted by a genetic model published by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2018, in which melanomas are categorized into those related to sun exposure and those not related, determined by their mutational signatures, epidemiology and anatomic site. Melanomas on sun-exposed skin were further divided into two groups based on their degree of cumulative sun damage (CSD) as determined by the severity of solar elastosis in the surrounding skin.[

22]

High CSD subtypes include lentigo maligna and desmoplastic melanomas. Low CSD subtypes include superficial spreading melanomas. Non-CSD subtypes include Spitz melanoma, acral melanoma, mucosal melanoma, some melanoma arising in congenital nevi, melanoma arising in blue nevi and uveal melanoma. Nodular melanoma may occur as high CSD, low CSD or non-CSD subtypes.[

22]

The genetic pathways correlate histologic subtypes with genetic alterations.[

22] For example, BRAF mutated melanomas are typically associated with low CSD while NRAS or S1 mutated melanomas are associated with high CSD. These findings have enabled more targeted immune therapy.[

23]

Mitotic Activity

Once thought to be more significant, mitotic activity is no longer part of pathological staging of melanoma. Studies found mitotic activity was not a significant independent predictor of survival, rather it largely reflects a correlation with BT.[

24] Its C-statistic is only 0.54, which indicates that its prognostic accuracy is just above random (a C-statistic of 1.0 means certainty and 0.5 means random accuracy).[

7]

Although included in the melanoma staging system and the seventh edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, it was removed in the eighth edition as tumor thickness and ulceration were recognised as the true independent predictors of melanoma specific survival. Nevertheless, the recommendation was to continue including mitotic activity in melanoma pathology reports.[

25] In view of the most recent multivariate data, evidence is lacking for recommending its continued inclusion.

Apart from the proliferative rate of the melanoma, other factors may affect the number of mitotic figures in the tumour. These include delays in fixation, with the mitotic cycle continuing ex vivo on fresh tissue until arrested by formalin fixation, and may result in either a decline or increase in observable mitotic figures.[

26]

Regression

10 to 35% of melanomas show regression. In regression, a tumor diminishes or disappears along with the appearance of lymphocytes, melanophages, newly formed vessels and fibrosis. It is presumed that inflammation predominates in the initial phases and fibrosis with melanophages appear subsequently. In the late stage, a non-lamellar fibrosis with melanophages develops (tumoral melanosis).[

27] Regression in melanomas is an immune response related to CD4+ lymphocytes.[

28]

Assessment of the regression includes description of the dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate, non-lamellar fibrosis, angiectatic blood vessels and attenuation of the epidermis. The horizontal extent and depth of regression allows for categorisation into focal (less than 50%), intermediate (50 to 75%) or extensive (more than 75%) regression.[

29] However, the College of American Pathologists recommends reporting the degree of regression using less than or equal to 75% or more than 75% as a cut-off.[

30]

Studies on the prognostic implications of regression have been contradictory.[

27] Given that the C-statistic for regression is only 0.54, as with mitotic index, this indicates that its prognostic accuracy is just above random.

Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes

The host immune response to melanoma includes CD4+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL).[

31] Studies on their prognostic value has yielded inconsistent results. The degree of TIL response is reported as absent, non-brisk and brisk. A brisk TIL response was associated with improved overall survival.[

32,

33]

Absent TIL is defined as no lymphocytes or, if present, lymphocytes which do not infiltrate the tumor. In non-brisk TIL there is a focal distribution of lymphocytes not present along the entire base of the invasive component. Brisk TIL indicates that the infiltrate is diffuse within the invasive component or infiltrates across the entire base of the invasive component.[

34]

It is the authors’ opinion that a more measurable parameter be used in place of the words "non-brisk" and "brisk", such as mild, moderate or marked.

Studies of TIL and other mechanisms of host immune response have led the way to immune therapy for melanoma.[

31]

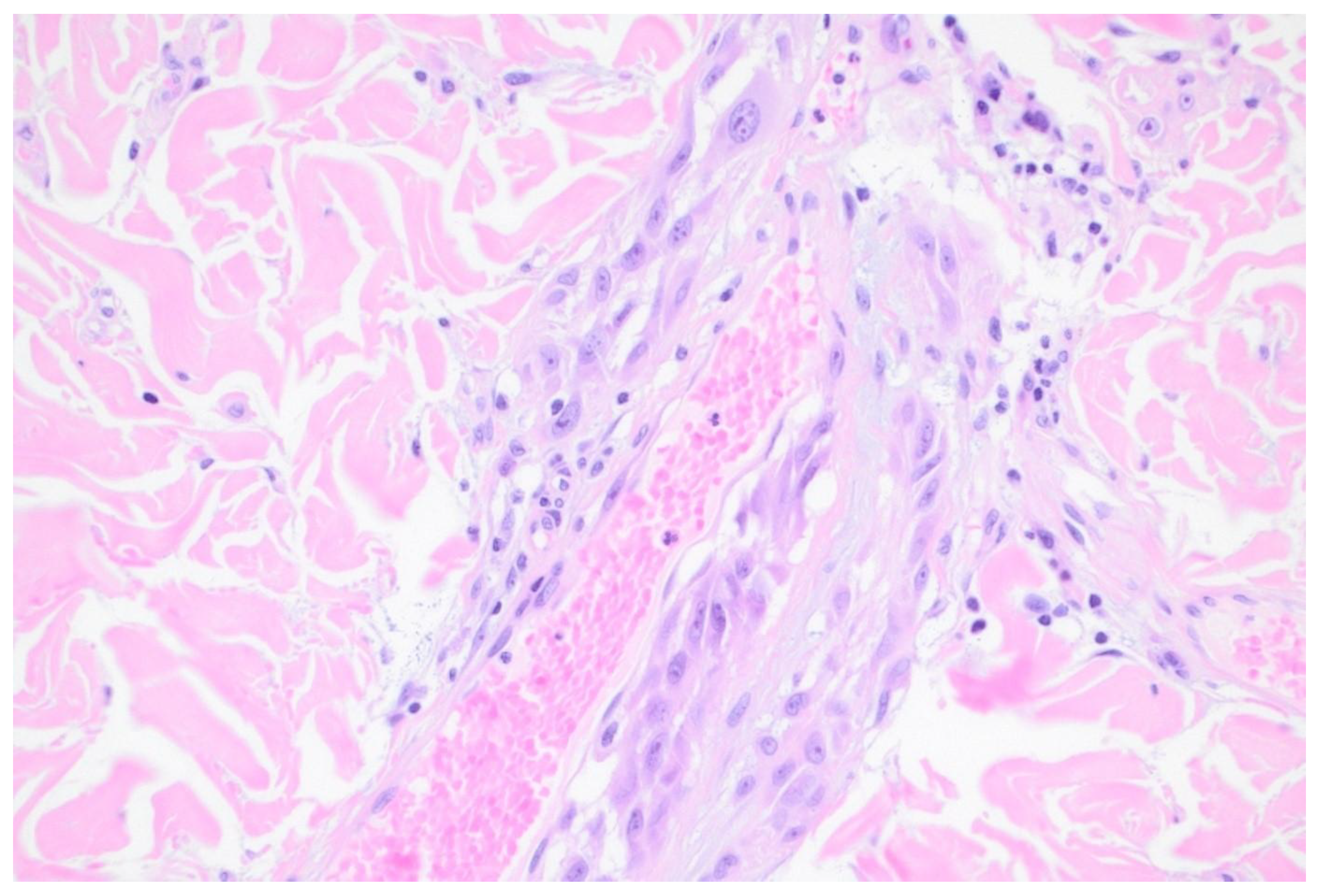

Lymphovascular Invasion

There are two modes of lymphovascular spread (LI), intravascular (lymphatic or vascular) and extravascular (abluminal). Access of melanoma cells to vasculature is the proposed mechanism for metastasis.[

35]

LI is detected in H&E sections. Postulated pitfalls in detecting LI include compression and obliteration of lymphatic endothelial cells, possibly leading to a false negative assessment, and stromal retraction artefact leading to a false positive assessment.[

35] Where LI is suspected in H&E sections, immunohistochemical staining reactions with endothelial markers may be helpful, particularly when used in combination with melanocytic markers such as SOX10. S100 is a less specific melanocytic marker as it may also stain histiocytes and dendritic cells, leading to a false positive result. Melan-A and MiTF are less sensitive than S100 and may also stain histiocytes. Endothelial markers include ERG. More specific stains for blood vessel endothelium are CD31 and CD34, and for lymphatic endothelium are D2-40 and LYVE-1, allowing distinction between the two.[

35,

36] Fli-1 also stains endothelial cells,[

37] but is less widely used.

LI is more commonly noted in lymphatic vessels than blood vessels, with one study finding lymphatic and vascular invasion rates of 27% and 4% respectively.[

38]

The presence of LI is associated with established features of worse prognosis, including higher BT and ulceration, and the presence of microsatellites and nodular subtype of melanoma.[

38]

Extravascular migratory metastasis of melanoma (EVMM) is the spread of melanoma cells on the external surfaces of vessels. This involves pericyte mimicry by melanoma cells. Pericytes are multifunctional, modified smooth muscle cells present in capillaries. EVMM is associated with regional and distant metastases in primary cutaneous melanomas. This phenomenon is probably under reported.[

39] [

Figure 2]

Perineural Invasion

Perineural invasion by melanoma is rare and is more commonly seen in desmoplastic melanoma. Neurotropism by melanoma is related to high expression of p75 neurotrophic receptor involved in the migration of Schwann cells to nerves. Perineural invasion has been described in melanomas affecting the cranial and cervical nerves, and the brachial plexus.[

42]

Association with Nevi

Meta-analysis indicates that 29.1% of melanomas are associated with a pre-existing nevus and 70.9% arise de novo. Melanomas associated with nevi are defined by histologic contiguity of the two.[

43]

However, it may not be possible to determine the exact percentages as the thicker the melanoma the higher is the probability for nevus remnants to be obscured or destroyed by malignant proliferation.[

44] Melanomas associated with nevi are more common in younger people, and more commonly associated with acquired nevi than congenital nevi. They most commonly occur in the sun-protected skin of the trunk and extremities. There is no significant difference between the sexes.[

44] Some studies found that melanoma associated with nevi have lower Breslow depth, however this was not corroborated in all studies.[

45]

The rate of transformation of nevi into cutaneous melanoma is low, ranging from 0.0005% or less in males and females younger than 40 years to 0.003% for patients older than 60 years, with an increase risk in males. The lifetime risk of any selected nevus transforming into melanoma by age 80 is approximately 0.03% for men and 0.009% for women.[

43] This is substantially lower than the rate of association of nevi with melanoma.

Gene-wide association studies have identified a number of genetic variants associated with a predisposition to develop nevi and are implicated in melanoma susceptibility. Different variants of IRF4 and BRAF V800E mutations have associations with both nevus-associated melanomas and de novo melanomas. Genetic analyses of microscopically contiguous nevus-melanoma pairs support the hypothesis that in nevus-associated melanomas, melanoma cells may be derived from nevus cells.[

46]

De novo melanoma (i.e. not associated with nevi) is more prevalent in older patients, females more than males, ulceration, and location on the head, neck or extremities compared to the trunk, and is less likely to have regression.[

47]

The differences between melanomas associated with nevi and de novo melanoma suggest that they are biologically different. However, there are no statistically significant differences in melanoma-specific death rates between melanomas associated with nevi and those that are not, after taking BT and ulceration into account.[

47]

Atypical Melanocytic Hyperplasia

Melanocytic hyperplasia with atypia, also known as de novo intraepidermal epithelioid melanocytic dysplasia, may be associated with dysplastic nevi and melanoma, suggesting that it is a marker for increased risk of developing melanoma. There is an association with chronic sun damage and an increased susceptibility to its damaging effects.[

48] Microscopically, there is a dominant single cell proliferation of atypical epithelioid melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis and may show pagetoid scatter.[

49] [

Figure 3]

Melanocytic hyperplasia may also be seen in association with inflammation, repeated ultraviolet light exposure, surgical excision sites, overlying vascular tumors and adjacent to basal cell carcinomas.[

50] Therefore, melanocytic hyperplasia may be a field change and it remains unclear whether these field changes are a precursor to melanoma development or represent features that occur after melanomagenesis.[

51] For this reason, it is the authors’ belief that it is not clinically warranted to attempt to eradicate field type melanocytic hyperplasia. Clinical follow-up with photography and dermoscopy is the recommended management.

Special Stains

Special stains include histochemical stains and immunohistochemical reactions. These may be used to identify melanocytes not clearly identifiable in ordinary H&E-stained slides and to identify melanocytes obscured by dense pigment or inflammation. In addition, panels of immunohistochemical stains may be used to subclassify melanocytic lesions and to assist in characterizing the biological potential of melanocytic lesions. The more commonly used stains are discussed in this section however a comprehensive review is outside the scope of this paper.

Histochemical stains are used to differentiate melanin pigment from iron pigment when this is not clear in H&E sections. Melanin stains with Schmorl’s or Fontana-Masson stain and iron pigment stains with Perls’ stain.[

52,

53]

Immunohistochemical reactions may be used to distinguish melanocytes from other cell types, in determining their biological potential where this may be uncertain from the H&E appearance of borderline lesions, and to determine possible response to immune therapy.

Immunohistochemical reactions are helpful in identifying and distinguishing melanocytes from other cell types in heavily pigmented or inflamed lesions. SOX10 is the most specific immunohistochemical reaction for melanocytes,[

54] however it may also react with non-melanocytic cells in scars which is a potential pitfall in melanoma re-excision specimens.[

55] S100 is more sensitive than SOX10, except for nail matrix melanocytes, but is less specific.[

54]

Melan-A/MART-1 is also less specific than SOX10, and also reacts with histiocytes and therefore overestimates the number of melanocytes. It is less sensitive in desmoplastic melanoma. SOX10 and MiTF have the advantage of being nuclear reactants, and are therefore useful in distinguishing pigmented melanocytes from histiocytes.[

54] MiTF is also less sensitive than SOX10 in desmoplastic melanoma. Epithelial reactants such as cytokeratin markers should be included in the panel to help distinguish melanocytes from other cell types.[

56]

Tyrosinase is expressed in junctional melanocytes, and expression decreases with dermal descent in compound melanocytic nevi. It stains 84% of metastatic melanoma and is essentially negative in desmoplastic melanomas.[

57]

Distinguishing benign from malignant tumours may be assisted with stains such as HMB-45, p16 and PRAME. HMB-45 tends to have decreased expression with depth and maturation in nevi while its expression in melanoma is often more consistent in the deeper component. However, exceptions to this deeper staining occur, particularly in nevoid melanomas.[

56]

P16 reacts with most nevi but not consistently in melanomas. P16 expression is seen in 61-100% of nevi, with most studies showing positivity closer to 100%. In these studies, 12-93% of melanomas stained for p16, with most studies[

11] reporting percentages within the range of 40s to 60s. If only nuclear staining is considered to be positive, the figures are 89-100% for nevi and 50-68% for invasive melanomas. The wide variation undermines the value of using p16 to differentiate between benign and malignant melanocytic lesions.[

58]

PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) is used to assist differentiation of benign melanocytic lesions from melanoma, however like other stains discussed, this is not entirely definitive. In a recent study, 13% of dysplastic nevi had diffuse reaction, and 20% of non-desmoplastic melanomas lacked reaction. Staining is seen in 35% of desmoplastic melanomas.[

59] PRAME staining may be seen in rare isolated junctional melanocytes in solar lentigines and benign non-lesional skin.[

60] In addition, PRAME staining may be seen in some poorly differentiated tumors including atypical fibroxanthomas.[

59]

Ki67 is a proliferation marker and is not a substitute for melanocytic mitotic counts in H&E sections. Nevertheless, it is an expression of tumor proliferation. In order to ensure that only staining in melanocytes and not inflammatory cells is counted, use of Ki67 combined with a cytoplasmic melanocytic marker such as melan-A and Ki-67 is recommended.[

54,

56]

It is evident from the above discussion that none of the antibodies alone will distinguish malignant from benign melanocytic lesions with certainty. However, as a panel they may be helpful in certain borderline tumors. Nevertheless, the immunohistochemical reactions should be interpreted considering the H&E appearance, and the diagnosis of melanoma should not be made solely based on the immunohistochemical staining profile if there is no corresponding atypia in the H&E sections.

Biomarkers used to determine possible response to immune therapy include markers for BRAF, V600E, NRAS and KIT mutations. Markers for immune checkpoint status, including PD-1 and PD-L1 are available.[

56]

Genetic Studies

Genetic studies are employed to detect certain genetic mutations or fusions for the purposes of tailoring immune therapy or to assist in subclassification of lesions where this is not apparent from the H&E sections.[

61] A comprehensive review is beyond the scope of this paper however some examples follow.

Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) is used to detect a limited number of mutations which may assist in determining whether a melanocytic lesion is benign or malignant.[

62]

Comparative genomic hybridisation tests for chromosomal gains and losses, and has some correlation with benign versus malignant tumors.[

63]

Next generation sequencing approaches detect specific point mutations to subclassify a melanocytic lesion or to determine its likelihood of being malignant. For example, the presence of a TERT promoter indicates malignancy.[

64]

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small, short-stranded non-coding RNAs.[

65] They are mediators in gene expression and their dysregulation plays a role in melanogenesis.[

66] They may have use as diagnostic markers.[

65] Assays of miRNAs may enhance the efficacy of staging systems, predicting patient prognoses and management in terms of choosing adjuvant therapies.[

66]

With the advent of immunotherapy, certain mutations, such as BRAF, NRAS and KRAS, are also used to guide treatment.[

61]

Margins

In excisional specimens, microscopic margins are measured from melanoma cells nearest the margin to the margin, and quoted in millimetres. It should be noted that guidelines for recommended excision margins refer to surgical margins.[

5] This is an important point as microscopic margins are smaller than surgical margins. The reasons for this are twofold. Firstly, natural skin tension due to intrinsic contractility of dermal elastin fibres is released after excision, causing the excised skin to contract. The percentage of shrinkage has been measured, with a mean of approximately 21% for length and approximately 12% for width of the biopsy. Shrinkage decreased 0.3% per year of increasing age of the patient. There was approximately 5% or greater shrinkage of the trunk compared to the head and neck.[

67] Secondly, further shrinkage occurs with formalin fixation according to most studies, with one study showing 11% shrinkage, being more pronounced in length than in width. One study showed increase in the tissue size following fixation.[

68]

Specimens may be orientated by the surgeon by placing sutures or nicks in the specimen at the time of surgery. There is no difference in recurrence rates for 2 cm versus 1 cm margins.[

69]

Conclusion

Thorough and accurate pathology evaluation and reporting of melanoma and its understanding by clinicians is vital to help determine further management. Reporting of Breslow thickness, patient Age, Ulceration, Subtype of melanoma, Sex of patient and Site of melanoma (BAUSSS biomarker) is essential to assess prognosis. Pathology documentation and clinician understanding of adequate margins, other associated pathology findings, special stains and genetic studies are equally important.

References

- Monshizadeh, L.; Hanikeri, M.; Beer, T.W.; et al. A critical review of melanoma pathology reports for patients referred to the Western Australian Melanoma Advisory Service. Pathology 2012, 44, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, L.A.; Eguchi, M.M.; Reisch, L.M.; et al. Histopathologic synoptic reporting of invasive melanoma: How reliable are the data? Cancer 2021, 127, 3125–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.R.; Colloby, P.S.; Martin-Clavijo, A.; et al. Melanoma histopathology reporting: are we complying with the National Minimum Dataset? J Clin Pathol 2007, 60, 1121–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, D. Dataset for histopathological reporting of primary cutaneous malignant melanoma and regional lymph nodes. Standards and datasets for reporting cancers: The Royal College of Pathologists. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, A.J.; Sladden, M.; Zouboulis, C.C.; et al. Primary Cutaneous Melanoma-Management in 2024. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessinioti, C.; Plaka, M.; Befon, A.; et al. A Retrospective Study of Diameter and Breslow Thickness in Invasive Melanomas. Dermatology 2024, 240, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.J.; Steinman, H.K.; Kyrgidis, A.; et al. Improved methodology in determining melanoma mortality and selecting patients for immunotherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2023, 37, e843–e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterpol, K.S.P.A.; Duncan, L.M. Measuring Melanoma Thickness. In Atlas of Essential Dermatopathology; Masterpol, K.S.P.A., Duncan, L.M., Eds.; Springer: London, 2013; pp. 104–105. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, T.J.; Lo, S.; Jackett, L.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Periadnexal Extension in Cutaneous Melanoma and its Implications for Pathologic Reporting and Staging. Am J Surg Pathol 2018, 42, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakousis, C.P.; Balch, C.M.; Urist, M.M.; et al. Local recurrence in malignant melanoma: long-term results of the multiinstitutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg Oncol 1996, 3, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sharouni, M.A.; Rawson, R.V.; Sigurdsson, V.; et al. The progressive relationship between increasing Breslow thickness and decreasing survival is lost in patients with ultrathick melanomas (≥15 mm in thickness). J Am Acad Dermatol 2022, 87, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, C.M.; Murad, T.M.; Soong, S.J.; et al. A multifactorial analysis of melanoma: prognostic histopathological features comparing Clark's and Breslow's staging methods. Ann Surg 1978, 188, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopf, A.W.; Welkovich, B.; Frankel, R.E.; et al. Thickness of malignant melanoma: global analysis of related factors. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1987, 13, 345–390, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marghoob, A.A.; Koenig, K.; Bittencourt, F.V.; et al. Breslow thickness and clark level in melanoma: support for including level in pathology reports and in American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging. Cancer 2000, 88, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatz, A.; Cook, M.G.; Elder, D.E.; et al. Interobserver reproducibility of ulceration assessment in primary cutaneous melanomas. Eur J Cancer 2003, 39, 1861–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolyer, R.A.; Shaw, H.M.; Thompson, J.F.; et al. Interobserver reproducibility of histopathologic prognostic variables in primary cutaneous melanomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2003, 27, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hantschke, M.; Bastian, B.C.; LeBoit, P.E. Consumption of the epidermis: a diagnostic criterion for the differential diagnosis of melanoma and Spitz nevus. Am J Surg Pathol 2004, 28, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bønnelykke-Behrndtz, L.M.; Schmidt, H.; Damsgaard, T.E.; et al. Consumption of the epidermis: a suggested precursor of ulceration associated with increased proliferation of melanoma cells. Am J Dermatopathol 2015, 37, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bønnelykke-Behrndtz, M.L.; Schmidt, H.; Christensen, I.J.; et al. Prognostic stratification of ulcerated melanoma: not only the extent matters. Am J Clin Pathol 2014, 142, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In 't Hout, F.E.; Haydu, L.E.; Murali, R.; et al. Prognostic importance of the extent of ulceration in patients with clinically localized cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg 2012, 255, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, C.M.; Soong, S.J.; Smith, T.; et al. Long-term results of a prospective surgical trial comparing 2 cm vs. 4 cm excision margins for 740 patients with 1-4 mm melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol 2001, 8, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, D.E.; Bastian, B.C.; Cree, I.A.; et al. The 2018 World Health Organization Classification of Cutaneous, Mucosal, and Uveal Melanoma: Detailed Analysis of 9 Distinct Subtypes Defined by Their Evolutionary Pathway. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2020, 144, 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.A.N.; Armstrong, S.M.; Hogg, D.; et al. Biologic subtypes of melanoma predict survival benefit of combination anti-PD1+anti-CTLA4 immune checkpoint inhibitors versus anti-PD1 monotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi Basir, H.R.; Alirezaei, P.; Ahovan, S.; et al. The relationship between mitotic rate and depth of invasion in biopsies of malignant melanoma. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2018, 11, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershenwald, J.E.; Scolyer, R.A.; Hess, K.R.; et al. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017, 67, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cree, I.A.; Tan, P.H.; Travis, W.D.; et al. Counting mitoses: SI(ze) matters! Mod Pathol 2021, 34, 1651–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, C.; Botella-Estrada, R.; Traves, V.; et al. [Problems in defining melanoma regression and prognostic implication]. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2009, 100, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, G.M.; Patel, A.; Hunt, M.J.; et al. Spontaneous regression of human melanoma/nonmelanoma skin cancer: association with infiltrating CD4+ T cells. World J Surg 1995, 19, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartron, A.M.; Aldana, P.C.; Khachemoune, A. Reporting regression in primary cutaneous melanoma. Part 2: prognosis, evaluation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol 2020, 45, 818–823. [Google Scholar]

- Colagrande, A.; Ingravallo, G.; Cazzato, G. Is It Time to Supersede the Diagnostic Term "Melanoma In Situ with Regression?" A Narrative Review. Dermatopathology (Basel) 2023, 10, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M. New modalities of cancer treatment for NSCLC: focus on immunotherapy. Cancer Manag Res 2014, 6, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lian, J.W.; Chin, Y.H.; et al. Assessing the Prognostic Significance of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Patients With Melanoma Using Pathologic Features Identified by Natural Language Processing. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2126337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Chen, N.; Ge, C.; et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, 1593806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antohe, M.; Nedelcu, R.I.; Nichita, L.; et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes: The regulator of melanoma evolution. Oncol Lett 2019, 17, 4155–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy, A.P.; Duncan, L.M.; Kraft, S. Lymphatic invasion and angiotropism in primary cutaneous melanoma. Lab Invest 2017, 97, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgrabinska, S.; Braun, P.; Velasco, P.; et al. Molecular characterization of lymphatic endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 16069–16074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folpe, A.L.; Chand, E.M.; Goldblum, J.R.; et al. Expression of Fli-1, a nuclear transcription factor, distinguishes vascular neoplasms from potential mimics. Am J Surg Pathol 2001, 25, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, S.J.; Safuan, S.; Mitra, A.; et al. Objective assessment of blood and lymphatic vessel invasion and association with macrophage infiltration in cutaneous melanoma. Mod Pathol 2012, 25, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirenberg, A.; Steinman, H.; Dixon, A. Melanoma extravascular migratory metastasis: an important underrecognized phenomenon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020, 34, e598–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, C.M.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Soong, S.J.; et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27, 6199–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bann, D.V.; Chaikhoutdinov, I.; Zhu, J.; et al. Satellite and In-Transit Metastatic Disease in Melanoma Skin Cancer: A Retrospective Review of Disease Presentation, Treatment, and Outcomes. Dermatol Surg 2019, 45, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, W.P.; Pereira, N.; Vaska, K. Perineural spread of recurrent cutaneous melanoma along cervical nerves into the spinal cord. BJR Case Rep 2017, 3, 20160122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, H.; Bevona, C.; Goggins, W.; et al. The transformation rate of moles (melanocytic nevi) into cutaneous melanoma: a population-based estimate. Arch Dermatol 2003, 139, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampena, R.; Kyrgidis, A.; Lallas, A.; et al. A meta-analysis of nevus-associated melanoma: Prevalence and practical implications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017, 77, 938–945.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gorgojo, A.; Nagore; et al. Melanoma Arising in a Melanocytic Nevus. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed) 2018, 109, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessinioti, C.; Geller, A.C.; Stratigos, A.J. A review of nevus-associated melanoma: What is the evidence? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022, 36, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessinioti, C.; Geller, A.C.; Stergiopoulou, A.; et al. A multicentre study of naevus-associated melanoma vs. de novo melanoma, tumour thickness and body site differences. Br J Dermatol 2021, 185, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessup, C.J.; Cohen, L.M. De novo intraepidermal epithelioid melanocytic dysplasia: a review of 263 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2010, 37, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, C.M.; Crowson, A.N.; Mihm, M.C.; et al. De novo intraepidermal epithelioid melanocytic dysplasia: an emerging entity. J Cutan Pathol 2010, 37, 866–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyers, W.; Bonczkowitz, M.; Weyers, I.; et al. Melanoma in situ versus melanocytic hyperplasia in sun-damaged skin. Assessment of the significance of histopathologic criteria for differential diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol 1996, 18, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, D.A.; Lian, C.G.; Hafeez, F. Determining the Association Between Melanomas and Fields of Melanocytic Dysplasia. Am J Dermatopathol 2023, 45, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shataer, M.; Shataer, S.; Libin, L.; et al. Histological comparison of two special methods of staining melanin in human skin. Int J Morphol 2020, 38, 1535–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, M.E.; Zaim, M.T. Histologic stains in dermatopathology. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990, 22, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferringer, T. Update on immunohistochemistry in melanocytic lesions. Dermatol Clin 2012, 30, 567–579, v. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, E.L.; Boothe, W.; D'Silva, N.; et al. SOX-10 staining in dermal scars. J Cutan Pathol 2019, 46, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, L.A.; Murphy, G.F.; Lian, C.G. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry in Cutaneous Neoplasia: An Update. Dermatopathology (Basel) 2015, 2, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, A.; Narala, S.; Raghavan, S.S. Immunohistochemistry in melanocytic lesions: Updates with a practical review for pathologists. Semin Diagn Pathol 2022, 39, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, S.S.; Cassarino, D.S. Immunohistochemical Expression of p16 in Melanocytic Lesions: An Updated Review and Meta-analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018, 142, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Ko, C.J.; McNiff, J.M.; et al. Pitfalls of PRAME Immunohistochemistry in a Large Series of Melanocytic and Nonmelanocytic Lesions With Literature Review. Am J Dermatopathol 2024, 46, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezcano, C.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Nehal, K.S.; et al. PRAME Expression in Melanocytic Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2018, 42, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Oak, A.S.W.; Slominski, R.M.; et al. Current Molecular Markers of Melanoma and Treatment Targets. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, G.; De Vanna, A.C. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization for Melanoma Diagnosis: A Review and a Reappraisal. Am J Dermatopathol 2016, 38, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanison, C.; Tanna, N.; Murthy, A.S. Comparative genomic hybridization for the diagnosis of melanoma. Eur J Plast Surg 2010, 33, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, G.; Colombino, M.; Casula, M.; et al. Molecular Pathways in Melanomagenesis: What We Learned from Next-Generation Sequencing Approaches. Curr Oncol Rep 2018, 20, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Sun, H.; Sun, Q.; et al. Circulating microRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Gholipour, M.; Taheri, M. MicroRNA Signature in Melanoma: Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 608987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, M.J.; Darst, M.A.; Olsen, T.G.; et al. Shrinkage of cutaneous specimens: formalin or other factors involved? J Cutan Pathol 2008, 35, 1093–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, J. Skin tumour specimen shrinkage with excision and formalin fixation-how much and why: a prospective study and discussion of the literature. ANZ J Surg 2021, 91, 2744–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doepker, M.P.; Thompson, Z.J.; Fisher, K.J.; et al. Is a Wider Margin (2 cm vs. 1 cm) for a 1.01-2.0 mm Melanoma Necessary? Ann Surg Oncol 2016, 23, 2336–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, C.M.; Urist, M.M.; Karakousis, C.P.; et al. Efficacy of 2-cm surgical margins for intermediate-thickness melanomas (1 to 4 mm). Results of a multi-institutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg 1993, 218, 262–267; discussion 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).