1. Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma is the most severe form of skin cancer, responsible for over 80% of skin cancer mortality [

1,

2]. It is the 5th most common cause of cancer in the United States, the United Kingdon and the European Union [

1,

3,

4], responsible worldwide for approximately 325,000 new cases and 57,000 deaths annually [

5]. Its incidence has been increasing in the last few decades [

1,

6], mainly because of increased UV radiation exposure[

5].

Melanoma earlier detection is of extreme importance as it provides better prognosis for patients and a more cost-effective treatment for healthcare institutions. However, there is still insufficient data to support population-based total body screening examination, and screening initiatives vary among healthcare systems.

For a screening test to be implemented, according to Wilson and Jungner’s screening principals [

7], the condition to be screened should be recognizable at a latent or early symptomatic stage and the screening test should be accurate, reliable and reproductive. Dobrow et al [

8] expanded the classical principles of Wilson and Junger and suggested that positive screening test results should also modify the natural history of the disease and improve patient outcome such as quality of life, increased functioning and reduced mortality.

Screening tests for melanoma include visual inspection of the skin with the naked eye and dermoscopy. The diffusion of dermoscopy has been extremely important for melanoma early diagnosis. Dermoscopy facilitates the diagnosis of thinner melanoma lesions, impacting on smaller surgical excisions [

9]. Dermoscopic characteristics are also relevant to help clinicians differentiate melanomas from equivocal melanocytic nevi, especially in the setting of small diameter lesions [

10].

Screening for skin cancer, however, involves potential harms including false-positive results that indicate the need for an unnecessary skin biopsy, and the possibility of melanoma overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Data regarding the benefit of melanoma population-based screening programs differs substantially [

2,

11,

12,

13]. A Belgium study from Hoorens et al [

11], found that lesion-directed examination detected skin cancer in a similar rate as total body screening skin examination. On the other hand, in Germany, the SCREEN project [

14], with over 360,000 patients, evidenced higher detection rates of melanomas in earlier stages and reduction in 5-years melanoma mortality when screening patients older than 20 years old. However, following the introduction of a nationwide skin cancer screening program in the same country, current data indicates that there has not been a real-life significant decline in melanoma-related mortality [

15].

As studies have not consistently shown evidence of decrease in mortality due to melanoma population-based screening programs, today, there is still no consensus of which would be the ideal melanoma screening strategy. Therefore, melanoma screening programs differ among health care systems and health care practitioners.

According to the US Preventive Services Task Force [

13], there is insufficient data to support melanoma screening in asymptomatic adolescents or adults without high risk for the disease. Thus, physicians should use their clinical judgment when deciding to perform melanoma screening. Similarly, in the United Kingdon, Australia and Italy there is also no recommended population-based melanoma screening program [

3,

16]. In Germany, however, since the results of the SCREEN project [

14], patients insured by statutory health insurance (88% of the population) are eligible for skin cancer screening, which includes biennial full body examination (performed by naked eye inspection) for patients older than 35 years old with a trained primary care physician or dermatologist [

17,

18].

Due to the relevance of melanoma diagnosis, the purpose of this study is to analyze melanoma earlier detection across two different strategies (standard total-body screening (TBS) and lesion-directed examination (LDE) of suspicious lesions) at a cohort of patients in the city of Milan, Italy. Early detection was defined as the detection of lesions with thickness lower than 0.8 mm (≤ T1a), as it is associated with a reduced risk of regional metastasis.

Secondary outcomes include calculating positive predictive value and analyzing patient and melanoma characteristics in both screened and non-screened groups.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design and patient selection

This is a retrospective cohort study conducted at the dermatology department of Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico in the city of Milan, Italy.

Data was collected from consecutive patients who came for dermatology visits and whose appointment reason was either the request of total-body screening examination or lesion-directed examination of a suspicious melanoma lesion, based on the ABCDE criteria. All patients were referred to dermatology visits from their primary care physician. Patients were excluded if they had a positive personal history of melanoma or known genetic predisposition for familial melanoma.

At the dermatology visit, skin examination was performed with naked-eye inspection and dermoscopy. For suspicious lesions, patients were referred to excision biopsies. Melanoma diagnosis was defined based on the histopathology results from skin biopsy. For atypical nevi in which dermoscopic features were not clearly suspicious of melanoma, short-term monitoring (3-6 months after initial appointment) with sequential digital dermoscopy was requested.

Data collection

Data, including clinical information and histopathology reports, were collected from review of electronic medical record of all visits performed between October and December 2023.

Patient data included appointment reason, age, sex, previous skin cancer screening visit, skin phototype (based on the Fitzpatrick classification), lesion anatomic site, personal history of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC), family history of melanoma, nevus count, chronic UV light exposure (represented by the presence of multiple solar lentigo), immunosuppression and histopathology results from skin biopsy.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the analysis, ethical review and approval were waived for this study.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (min–max). Categorial variables are presented in absolute number (percentage).

Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s Chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests, and quantitative variables, using t-Student and Mann-Whitney tests. Multiple logistic regression was performed for the multivariate analysis. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered significant for the univariate and multivariate tests.

Positive predictive value (PPV) was calculated as number of histologically confirmed melanomas/number of lesions excised × 100. Detection rate was defined as the number of histologically confirmed melanomas divided by the respective cohort size.

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

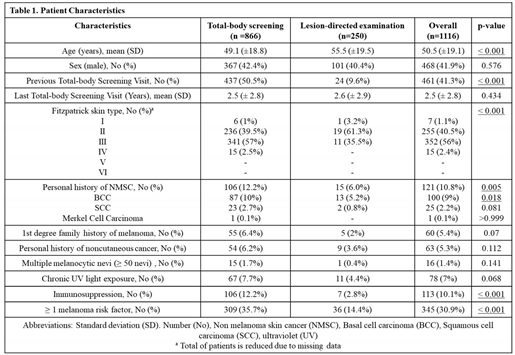

1116 patients were included in the cohort of this study. Out of the total number of participants, 866 came for total-body screening visits, whereas 250 came for lesion-directed examination. Mean age at dermatology visit was 50 years old (median 51 years old) and varied between 14 and 94 years old (

Table 1).

The majority of patients were females (58.1%) and did not have a risk factor for malignant melanoma (69.1%) (

Table 1). Risk factors were defined as first-degree family history of melanoma, personal history of NMSC, immunosuppression, multiple melanocytic nevi (≥ 50 nevi) and history of chronic UV light exposure, evidenced by the presence of solar lentigo.

Fitzpatrick skin type information was available for only 56.3% of patients and 96.5% percent of those patients had skin phototypes 2 or 3. Additional patient characteristics are evidenced in

Table 1.

3.2. Comparative analysis between total-body screening and lesion-directed examination groups

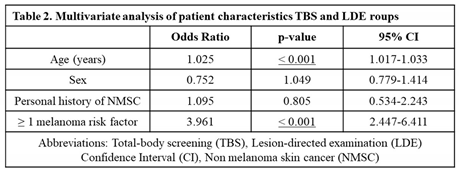

After adjusting for clinical and statistically significant variables including sex and personal history of NMSC, patients who came for total-body screening visits were younger and more frequently associated with a positive risk factor for malignant melanoma, compared to patients in the LDE group (p < 0.001) (

Table 2). Most frequent risk factors in the screening group included personal history of NMSC (specially BCC) and immunosuppression. Patients in both groups, however, did not differ significantly regarding other characteristics including sex, personal history of noncutaneous cancer, first-degree family history of melanoma, multiple melanocytic nevi (≥ 50 nevi) or history of chronic UV light exposure (

Table 1).

Among patients who came for LDE visits, most of them (68.8%) were referred to the dermatology visit from their primary care physician under a priority list, in which the visits were performed up to 72h (9.6% of patients), 10 (33.2%) or 30 days (26%) after the request. For those who were not referred under a priority list, dermatology visits were performed preferentially up to 120 days after the request. Patients in the LDE group whose lesion had indication of excision biopsy came mainly under priority groups in which visits should be performed up to 10 days after the request (61.1%).

Clinical diagnosis of patients who came for LDE but the lesion was considered, on physical examination, clinically negative for melanoma included: melanocytic nevus without atypia (32.5%), seborrheic keratosis (51%), angioma (6.2%), solar lentigo (3.1%) and others (7.2%).

In total, 461 patients declared to have previously done a total-body skin cancer screening examination. This tendency was more evident in screened patients, in which 437 of them had already performed a previous screening visit, compared to 24 from LDE group (p<0.001) (

Table 1). Mean time since the last screening visit was 2.5 years, without significant difference between the two groups (

Table 1). Among patients who came for total body screening visits, 12% of them were part of institutional screening programs for immunosuppressed patients or for occupational exposure to ionizing radiation.

3.3. Melanoma diagnosis

In total, 89 excision biopsies were requested, 71 were performed, and 19 melanomas were histologically confirmed (positive predictive value of 26.7%). The average time between dermatology visit and skin biopsy was 58.8 days.

There was a higher proportion of suspected and diagnosed melanomas in the LDE group. Out of 250 patients, 52 (20.8%) biopsies were requested, 42 (16.8%) were performed, and 10 (4%) melanomas were confirmed (PPV 23.8%). Whereas out of the 866 patients in the TBS group, only 37 biopsies were requested (4.3%), 29 (3.3%) were performed and 9 (1%) melanomas were confirmed (PPV 31%). The detection rate was significantly different between both groups (p-value = 0,003).

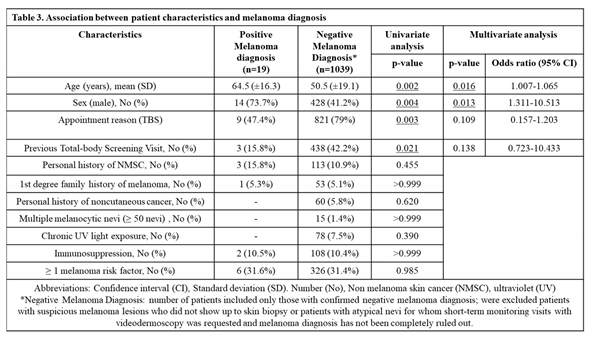

Melanomas were diagnosed more frequently in male sex (73.7%; p = 0.013) and older patients (mean age 64.5 yo; p = 0.016) (

Table 3). No melanomas were confirmed in patients under 30 years old. Demographic, clinical and lesion histologic characteristics of patients diagnosed with the disease are summarized in

Table 3 and

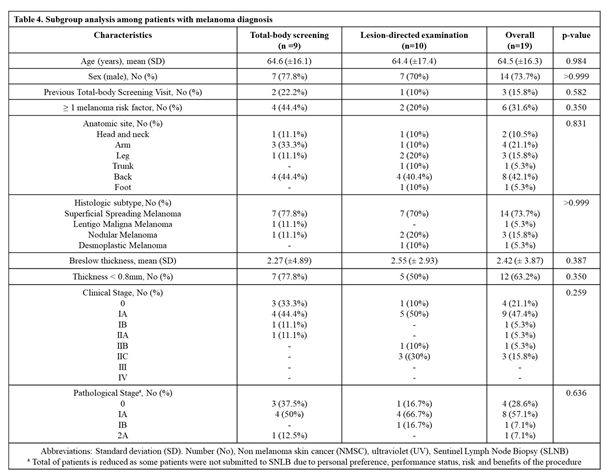

Table 4. Among patients with melanoma, no demographic, clinical or histologic characteristics differed between TBS and LDE groups (summarized in

Table 4).

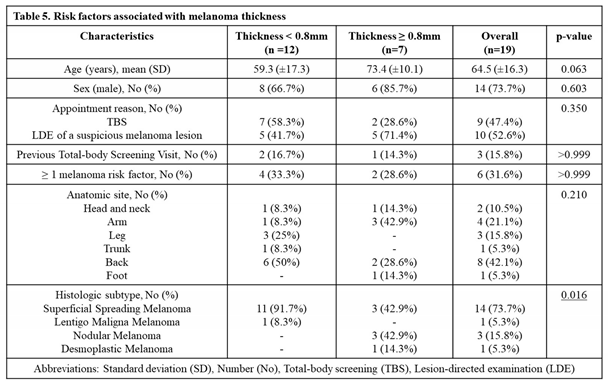

Out of the 9 histologically confirmed melanomas in the TBS group, 7 (77.8%) were diagnosed in earlier stages (thinner than 0.8mm). In comparison, in the LDE group, 5 (50%) out of the 10 histologically confirmed melanomas, were diagnosed in earlier stages (

Table 4 and

Table 5). While thicker melanomas (≥ 0.8mm) were found more often in patients who came for lesion-directed examination, this finding was not confirmed to be statistically significant (p=0.350) (

Table 4). Melanomas in screened patients, therefore, were not statistically associated with thinner lesions. The incidence of thicker melanoma (≥ 0.8mm) was only associated with melanoma histologic subtype, specifically desmoplastic and nodular melanoma. No other characteristic was found to be associated with higher melanoma thickness (

Table 5).

Out of the negative biopsies for melanoma, histologic diagnosis included unspecified melanocytic nevus (55.8%), Spitz nevus (1.9%), blue nevus (7.7%), seborrheic keratosis (11.5%), and others (23.1%).

Atypical nevi not clearly suspicious of melanoma were clinically evidenced in 40 patients (12 from LDE group and 28 from TBS group), for whom short-term monitoring visits (in 3 to 6 months) with videodermoscopy were requested.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that, when performed by dermatologists, population-based total-body screening program might not be more effective in diagnosing melanoma at earlier stages than directed examination of suspicious lesions. In this cohort of patients, total-body screening examination was not associated with the diagnosis of melanoma at earlier stages (thickness < 0.8mm). This finding contradicts current literature that reports reduced melanoma thickness in screening programs compared to usual care rates [

14,

19,

20], Diagnosing melanoma at earlier stages is of extreme importance because of its impact on quality of life and prognosis.

Moreover, in this study, melanoma detection rate was significantly different between groups. Among patients in the LDE group, 4% were diagnosed with melanoma. While, within screened patients, melanoma incidence was 1%. In our study, the incidence of melanoma in screened patients is higher than the ones evidenced in previous studies, which reported an incidence around 0.1-0.5% [

11,

19,

21,

22,

23]. First of all, a higher incidence in screened patients can be due to the visits being performed by dermatologists instead of general practitioners. In literature, most of the screening programs were performed by general practitioners. In addition, the incidence of melanoma in northern Italy, where this study was conducted, is higher than in other parts of the country [

24]. Also, our screening population might not have been fully representative of the general population, instead, it might have represented a higher risk population. Patients who were screened were not invited for a screening visit but requested those visit themselves. This group of patients might have already been more aware of skin cancer. It was evident in this cohort that more patients who came for total-body screening visits had already performed previous screening visits, and were more frequently associated with a positive risk factor for malignant melanoma, compared to patients who came for LDE of a suspicious lesion.Positive predictive value for diagnosing melanoma was also calculated. Herein, PPV was 26.7%, which is consistent with the values described in literature, ranging from 2.5-50% [

11,

20,

25,

26].

Regarding the harms of screening, unnecessary surgical excisions were performed in 20 screened patients. The excised benign/melanoma ratio for screened patients was approximately 2:1, which is slightly lower than the ones found in the literature [

23,

27].

In total, no melanomas were histologically confirmed in patients under 30 years old. Therefore, an option to enhance population-based total-body screening efficiency could be recommending a minimum age for dermatologic screening for patients without a melanoma risk factor. Risk factors include genetic predisposition, first-degree family history of melanoma, personal history of NMSC, immunosuppression, multiple melanocytic nevi (≥ 50 nevi) and history of chronic UV light exposure. Restricting the screening age could be useful especially in healthcare systems with long waiting lists and reduced budgets.

This study, however, had limitations, including a small cohort of patients, the retrospective design of the study and single-center location. Also, the effectiveness of screening and lesion-directed examination strategies were compared based on the diagnosis of melanoma with reduced thickness (< 0.8mm). However, it was not analyzed the effects of both strategies in outcomes such as mortality and cost effectiveness.

5. Conclusions

In this study, there was a high incidence of melanoma diagnosis in this study, both in the lesion-directed examination and total-body screening groups. More importantly, it was evidenced that total-body screening examinations were not associated with earlier diagnosis of melanoma (thickness < 0.8mm).

Therefore, in healthcare systems where budgets are reduced, direct examination of suspicious lesions (previously inspected by general practitioners) can be an alternative to population-based total-body screening visits, when both visits are performed by dermatologists. For this strategy to be implemented, it is imperative that general practitioners know melanoma clinical criteria in order to correctly suspect of a lesion and refer the patient for prompt dermatologic care.

Further studies with higher level of evidence are needed to establish the best melanoma detection strategy to reduce mortality and improve quality of life.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.Conceptualization, Camila Caraviello and Gianluca Nazzaro; Data curation, Camila Caraviello; Formal analysis, Camila Caraviello; Investigation, Camila Caraviello; Methodology, Camila Caraviello and Gianluca Nazzaro; Supervision, Gianluca Nazzaro, Silvia Alberti-Violetti and Angelo Valerio Marzano; Validation, Angelo Valerio Marzano; Visualization, Silvia Alberti-Violetti, Emanuela Passoni, Valentina Benzecry, Paolo Bortoluzzi, Giulia Murgia and Angelo Valerio Marzano; Writing – original draft, Camila Caraviello and Gianluca Nazzaro; Writing – review & editing, Gianluca Nazzaro and Angelo Valerio Marzano.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In our institution, ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the retrospective nature of the analysis.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived as this was a retrospective chart review study of many patients. In addition, patients in the study could not be identified, and this research posed no risk to the patient.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the individuals and institutions that contributed to the completion of this research paper.First of all, we would like to thank Luigia Venegoni for all the dermatopathology help and support throughout the research process. We extend our gratitude to the Department of Dermatology at IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico for the necessary facilities indispensable for carrying out data collection and dermatology visits. Special thanks also to the University of Milan for their commitment to fostering research.We declare this research did not receive funding or financial support for its execution.This research was a collaborative effort from individuals and institutions listed above. Once again, we are grateful for their support and their contributions have greatly improved the quality of this research paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TBS |

Total-Body Screening |

| LDE |

Lesion-Directed Examination |

UV

SD

PPV

NMSC

BCC |

Ultraviolet

Standard Deviation

Positive Predictive Value

Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer

Basal Cell Carcinoma |

References

- National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemioloy, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Melanoma of the Skin. 2024.

- Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Melanoma. Medical Sciences. 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melanoma skin cancer statistics Cancer Research, U.K. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/melanoma-skin-cancer (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- De Angelis R, Demuru E, Baili P, Troussard X, Katalinic A, Chirlaque Lopez MD; et al. Complete cancer prevalence in Europe in 2020 by disease duration and country (EUROCARE-6): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Vaccarella S, Meheus F; et al. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy GP, Thomas CC, Thompson T, Watson M, Massetti GM, Richardson LC; et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections - United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015, 64, 591–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JMG, Jungner G, World Health Organization. Principles and practice of screening for disease. 1968.

- Dobrow, M.J.; Hagens, V.; Chafe, R.; Sullivan, T.; Rabeneck, L. Consolidated principles for screening based on a systematic review and consensus process. Can Med Assoc J. 2018, 190, E422–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, G.; Passoni, E.; Pozzessere, F.; Maronese, C.A.; Marzano, A.V. Dermoscopy Use Leads to Earlier Cutaneous Melanoma Diagnosis in Terms of Invasiveness and Size? A Single-Center, Retrospective Experience. J Clin Med. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro G, Maronese CA, Casazza G, Giacalone S, Spigariolo CB, Roccuzzo G; et al. Dermoscopic predictors of melanoma in small diameter melanocytic lesions (mini-melanoma): a retrospective multicentric study of 269 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2023, 62, 1040–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, Boone B, De Schepper S, Ongenae K; et al. Total-Body Examination vs Lesion-Directed Skin Cancer Screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016, 152, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunssen, A.; Waldmann, A.; Eisemann, N.; Katalinic, A. Impact of skin cancer screening and secondary prevention campaigns on skin cancer incidence and mortality: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017, 76, 129–139e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, Chelmow D, Coker TR, Davis EM; et al. Screening for Skin Cancer. JAMA. 2023, 329, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbart EW, Waldmann A, Nolte S, Capellaro M, Greinert R, Volkmer B; et al. Systematic skin cancer screening in Northern Germany. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012, 66, 201–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katalinic, A.; Eisemann, N.; Waldmann, A. Skin Cancer Screening in Germany. Documenting Melanoma Incidence and Mortality From 2008 to 2013. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015, 112, 629–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The Australasian College of Dermatologists Position Statement: Population-based screening for melanoma. Available online: https://www.dermcoll.edu.au/about/position-statements/ (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Görig, T.; Schneider, S.; Breitbart, E.W.; Diehl, K. Is the quality of skin cancer screening in Germany related to the specialization of the physician who performs it?: Results of a nationwide survey among participants of skin cancer screening. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2021, 37, 454–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datzmann, T.; Schoffer, O.; Meier, F.; Seidler, A.; Schmitt, J. Are patients benefiting from participation in the German skin cancer screening programme? A large cohort study based on administrative data. British Journal of Dermatology. 2022, 186, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, M.; Mahon, S.M.; Eden, K.B.; Frame, P.S.; Orleans, C.T. Screening for skin cancer. Am J Prev Med. 2001, 20, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh HK, Norton LA, Geller AC, Sun T, Rigel DS, Miller DR; et al. Evaluation of the American Academy of Dermatology’s National Skin Cancer Early Detection and Screening Program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996, 34, 971–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton RC, Howe C, Adamson L, Reid AL, Hersey P, Watson A; et al. General practitioner screening for melanoma: sensitivity, specificity, and effect of training. J Med Screen. 1998, 5, 156–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller AC, Zhang Z, Sober AJ, Halpern AC, Weinstock MA, Daniels S; et al. The first 15 years of the American Academy of Dermatology skin cancer screening programs: 1985-1999. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003, 48, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Bakos RM, Bergman W, Blum A; et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening in patients with focused symptoms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012, 66, 212–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIRT Working Group. Italian cancer figures--report 2006: 1. Incidence, mortality and estimates. Epidemiol Prev. 2006, 30, 8–10, 12–28, 30-101 passim. [Google Scholar]

- Jonna, B.P.; Delfino, R.J.; Newman, W.G.; Tope, W.D. Positive Predictive Value for Presumptive Diagnoses of Skin Cancer and Compliance with Follow-Up among Patients Attending a Community Screening Program. Prev Med (Baltim). 1998, 27, 611–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, J.F.; Janda, M.; Elwood, M.; Youl, P.H.; Ring, I.T.; Lowe, J.B. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006, 54, 105–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carli P, De Giorgi V, Crocetti E, Mannone F, Massi D, Chiarugi A; et al. Improvement of malignant/benign ratio in excised melanocytic lesions in the “dermoscopy era”: a retrospective study 1997-2001. British Journal of Dermatology. 2004, 150, 687–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of patient characteristics between total-body screening and lesion-directed examination groups.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of patient characteristics between total-body screening and lesion-directed examination groups.

Table 3.

Association between patient characteristics and melanoma diagnosis.

Table 3.

Association between patient characteristics and melanoma diagnosis.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis among patients with melanoma diagnosis.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis among patients with melanoma diagnosis.

Table 5.

Risk factors associated with melanoma thickness.

Table 5.

Risk factors associated with melanoma thickness.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).