Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Lung Cancer in Smokers

4. Smoke-Induced Vascular Pathology

4.1. Circulating Tumor Cells Dynamics in Vasculopathy

4.2. Apolipoproteins

5. Smoking, COPD and Systemic Vasculopathy in Lung Cancer

6. The Immune-Inflammatory Axis in Vasculopathy and Lung Cancer Dissemination.

| l | Factor | Mechanism | Potential actionable target |

| Immune-Inflammatory | IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokines promoting chronic inflammation, tumor promotion, angiogenesis | Anti-cytokine therapies (e.g., IL-1β inhibitors, anti-TNF agents) |

| NF-κB, STAT3, HIF-1α signalling | Sustained pro-survival and inflammatory signalling pathways | NF-κB/STAT3 inhibitors, HIF-1α modulators | |

| T-reg depletion, CD8+ T cell predominance | Immune imbalance, reduced immunosurveillance | T-reg restoration, immune checkpoint modulation | |

| Macrophage polarization (M1 dominance, tumor-associated macrophages) | Pro-tumor inflammation, matrix remodeling | CSF-1R inhibitors, macrophage reprogramming | |

| Oxidative stress | ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction | DNA damage, impaired apoptosis | Antioxidants, mitochondrial protective agents |

| Vascular dysfunction | Endothelial adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin) | Promotes leukocyte adhesion, CTC arrest | Anti-adhesion therapies (e.g., selectin blockers) |

| Reduced NO bioavailability | Endothelial dysfunction, impaired vasodilation | NO donors, endothelial stabilizers | |

| Pathologic angiogenesis (VEGF, Angiopoietin-2) | Abnormal, leaky vessels facilitating metastasis | Anti-VEGF therapies, angiopoietin pathway inhibitors | |

| Biomechanical | Low shear stress, turbulent flow, flow stagnation | Facilitates CTC adhesion, extravasation | Vascular normalization, flow modulation |

| Elevated IFP | Drives outward migration of tumor cells | Anti-VEGF, normalization of tumor IFP | |

| Extracellular matrix | MMP-2, MMP-9 | ECM degradation enabling invasion | MMP inhibitors |

| Epigenetic/Genetic | DNA methylation, histone modifications | Silencing of tumor suppressor genes | Epigenetic drugs (e.g., DNMT inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors) |

| Apolipoproteins/Lipids | Oxidized LDL, ApoB/ApoE dysregulation | Endothelial activation, macrophage recruitment | Lipid-lowering agents, ApoE modulators |

| Aneurysmal niche | MMP overexpression, inflammatory cell infiltration | Vessel wall degradation, permissive microenvironment | MMP inhibitors, anti-inflammatory therapies |

| Hemodynamic abnormalities in aneurysm (low WSS, recirculation zones) | Increased CTC residence time and adhesion | Flow-altering endovascular interventions | |

| Pharmacologic interactions | Corticosteroids, ICS | Immune suppression, impaired antigen presentation | Tapering strategies, ICS alternatives |

| Aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitors | Reduce platelet cloaking of CTCs, inhibit thrombosis | Consider as adjunct to anti-metastatic therapy | |

| Triple inhaled therapy (ICS/LABA/LAMA) | Reduces inflammation, improves oxygenation | May indirectly mitigate hypoxia-driven tumor progression | |

| PD-L1 expression | Immune evasion by inhibiting T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity | Enhances tumor immune escape and metastatic spread | Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy (e.g., pembrolizumab) |

| Tumor-stromal cross-talk | EMT promotion (TGF-β, matrix degradation) | Increases invasiveness, resistance to apoptosis | TGF-β inhibitors, EMT blockers |

| Key points | Knowledge gap |

|

LUNG CANCER →Immune checkpoint inhibitors Inflamed or remodelled vasculature in COPD or systemic vasculopathy may be a critical determinant of response to immunotherapy | |

|

|

|

COPD → Triple bronchodilation Beyond airway-specific effects, it can have systemic implications relevant to tumor-immune dynamics | |

|

|

|

VASCULOPATHY→Antiplatelet therapy Platelets can shield CTCs from immune recognition and promote their extravasation | |

|

|

7. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

Support Statement

References

- Cancer Facts & Figures 2023. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc.; 2022. Accessed January 9, 2024. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2023/2023-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf.

- Kızılırmak D, Yılmaz Z, Havlucu Y, Çelik P. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Diagnosis of Lung Cancer. SN Compr Clin Med. 2023;5(1):23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantini L, Mentrasti G, Russo GL, Signorelli D, Pasello G, Rijavec E, Russano M, Antonuzzo L, Rocco D, Giusti R, Adamo V, Genova C, Tuzi A, Morabito A, Gori S, Verde N, Chiari R, Cortellini A, Cognigni V, Pecci F, Indini A, De Toma A, Zattarin E, Oresti S, Pizzutilo EG, Frega S, Erbetta E, Galletti A, Citarella F, Fancelli S, Caliman E, Della Gravara L, Malapelle U, Filetti M, Piras M, Toscano G, Zullo L, De Tursi M, Di Marino P, D'Emilio V, Cona MS, Guida A, Caglio A, Salerno F, Spinelli G, Bennati C, Morgillo F, Russo A, Dellepiane C, Vallini I, Sforza V, Inno A, Rastelli F, Tassi V, Nicolardi L, Pensieri V, Emili R, Roca E, Migliore A, Galassi T, Rocchi MLB, Berardi R. Evaluation of COVID-19 impact on DELAYing diagnostic-therapeutic pathways of lung cancer patients in Italy (COVID-DELAY study): fewer cases and higher stages from a real-world scenario. ESMO Open. 2022 Apr;7(2):100406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Jan-Feb;74(1):12-49. [CrossRef]

- Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553(7689):446–454.

- Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA. Non–small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(5):584–594.

- Skoulidis F, Heymach JV. Co-occurring genomic alterations in non-small-cell lung cancer biology and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(9):495–509.

- Tsoukalas N, Aravantinou-Fatorou E, Baxevanos P, Tolia M, Tsapakidis K, Galanopoulos M, et al. Molecular biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer: a review. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2018;19(8):586–597.

- O'Donnell JS, Teng MWL, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting and resistance to T cell-based immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(3):151–167.

- Brennan P, Hainaut P, Boffetta P. Genetics of lung-cancer susceptibility. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Apr;12(4):399-408. [CrossRef]

- e Alencar VTL, Formiga MN, de Lima VCC. Inherited lung cancer: a review. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020 Jan 29;14:1008. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal M, Ding XJ, Cao Y. Familial risk for lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017 Feb;13(2):535-542. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian J, Govindan R. Molecular genetics of lung cancer in people who have never smoked. Lancet Oncol. 2008 Jul;9(7):676-82. [CrossRef]

- Stella GM, Luisetti M, Pozzi E, Comoglio PM. Oncogenes in non-small-cell lung cancer: emerging connections and novel therapeutic dynamics. Lancet Respir Med. 2013 May;1(3):251-61. [CrossRef]

- Benusiglio PR, Fallet V, Sanchis-Borja M, Coulet F, Cadranel J. Lung cancer is also a hereditary disease. Eur Respir Rev. 2021 Oct 20;30(162):210045. [CrossRef]

- Smolle E, Pichler M. Non-Smoking-Associated Lung Cancer: A distinct Entity in Terms of Tumor Biology, Patient Characteristics and Impact of Hereditary Cancer Predisposition. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Feb 10;11(2):204. [CrossRef]

- Vancheri C, Failla M, Crimi N, Raghu G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disease with similarities and links to cancer biology. Eur Respir J. 2010 Mar;35(3):496-504. [CrossRef]

- Stella GM, D'Agnano V, Piloni D, Saracino L, Lettieri S, Mariani F, Lancia A, Bortolotto C, Rinaldi P, Falanga F, Primiceri C, Corsico AG, Bianco A. The oncogenic landscape of the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a narrative review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2022 Mar;11(3):472-496. [CrossRef]

- Lettieri S, Oggionni T, Lancia A, Bortolotto C, Stella GM. Immune Stroma in Lung Cancer and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Common Biologic Landscape? Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 12;22(6):2882. [CrossRef]

- Perrotta F, Chino V, Allocca V, D'Agnano V, Bortolotto C, Bianco A, Corsico AG, Stella GM. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer: targeting the complexity of the pharmacological interconnection. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2022 Oct;16(10):1043-1055. [CrossRef]

- CDC https://www.cdc.gov/lung-cancer/risk-factors/index.html#:~:text=People%20who%20smoke%20cigarettes%20are,the%20risk%20of%20lung%20cancer.

- Crispo A, Brennan P, Jöckel KH, Schaffrath-Rosario A, Wichmann HE, Nyberg F, Simonato L, Merletti F, Forastiere F, Boffetta P, Darby S. The cumulative risk of lung cancer among current, ex- and never-smokers in European men. Br J Cancer. 2004 Oct 4;91(7):1280-6. [CrossRef]

- Asomaning K, Miller DP, Liu G, Wain JC, Lynch TJ, Su L, Christiani DC. Second hand smoke, age of exposure and lung cancer risk. Lung Cancer. 2008 Jul;61(1):13-20. [CrossRef]

- Berg CD, Schiller JH, Boffetta P, Cai J, Connolly C, Kerpel-Fronius A, Kitts AB, Lam DCL, Mohan A, Myers R, Suri T, Tammemagi MC, Yang D, Lam S; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Early Detection and Screening Committee. Air Pollution and Lung Cancer: A Review by International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Early Detection and Screening Committee. J Thorac Oncol. 2023 Oct;18(10):1277-1289. [CrossRef]

- Loomis D, Huang W, Chen G. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) evaluation of the carcinogenicity of outdoor air pollution: focus on China. Chin J Cancer. 2014 Apr;33(4):189-96. [CrossRef]

- Myers R, Brauer M, Dummer T, Atkar-Khattra S, Yee J, Melosky B, Ho C, McGuire AL, Sun S, Grant K, Lee A, Lee M, Yuchi W, Tammemagi M, Lam S. High-Ambient Air Pollution Exposure Among Never Smokers Versus Ever Smokers With Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2021 Nov;16(11):1850-1858. [CrossRef]

- Brunekreef B, Beelen R, Hoek G, Schouten L, Bausch-Goldbohm S, Fischer P, Armstrong B, Hughes E, Jerrett M, van den Brandt P. Effects of long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution on respiratory and cardiovascular mortality in the Netherlands: the NLCS-AIR study. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2009 Mar;(139):5-71; discussion 73-89. [PubMed]

- Shahadin MS, Ab Mutalib NS, Latif MT, Greene CM, Hassan T. Challenges and future direction of molecular research in air pollution-related lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 2018 Apr;118:69-75. [CrossRef]

- Celià-Terrassa T, Kang Y. Metastatic niche functions and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Cell Biol. 2018 Aug;20(8):868-877. [CrossRef]

- Patel SA, Rodrigues P, Wesolowski L, Vanharanta S. Genomic control of metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan;124(1):3-12. [CrossRef]

- Kiri S, Ryba T. Cancer, metastasis, and the epigenome. Mol Cancer. 2024 Aug 2;23(1):154. [CrossRef]

- Stella GM, Senetta R, Cassenti A, Ronco M, Cassoni P. Cancers of unknown primary origin: current perspectives and future therapeutic strategies. J Transl Med. 2012 Jan 24;10:12. [CrossRef]

- Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):16–27.

- Hogg JC, Timens W. The pathology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:435–459.

- Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Bracke KR. New insights into the immunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2011;378(9795):1015–1026.

- Mazzuca P, Carloni A, Cazzato F, et al. Tobacco smoke and the vascular endothelium: from inflammation to transformation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):7755.

- Yang IA, Relan V, Wright CM, Davidson MR, Sriram KB, Savarimuthu Francis SM, et al. Common pathogenic mechanisms and epigenetic changes in lung cancer and COPD. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(3):1353–1360.

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Ma J, et al. The role of COPD in lung cancer: insights from human and murine studies. Cancer Lett. 2022;543:215797.

- Moorthy B, Chu C, Carlin DJ. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: from metabolism to lung cancer. Toxicol Sci. 2015 May;145(1):5-15. [CrossRef]

- Goldman R, Enewold L, Pellizzari E, Beach JB, Bowman ED, Krishnan SS, Shields PG. Smoking increases carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human lung tissue. Cancer Res. 2001 Sep 1;61(17):6367-71.

- Martey CA, Baglole CJ, Gasiewicz TA, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a regulator of cigarette smoke induction of the cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin pathways in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005 Sep;289(3):L391-9. [CrossRef]

- Shehata SA, Toraih EA, Ismail EA, Hagras AM, Elmorsy E, Fawzy MS. Vaping, Environmental Toxicants Exposure, and Lung Cancer Risk. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Sep 12;15(18):4525. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Jiang C, Hsu ML, Wisnivesky J, Dowlati A, Boffetta P, Kong CY. E-Cigarette Use and Lung Cancer Screening Uptake. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jul 1;7(7):e2419648. [CrossRef]

- Allbright K, Villandre J, Crotty Alexander LE, Zhang M, Benam KH, Evankovich J, Königshoff M, Chandra D. The paradox of the safer cigarette: understanding the pulmonary effects of electronic cigarettes. Eur Respir J. 2024 Jun 28;63(6):2301494. [CrossRef]

- https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/e-cigarettes/youth.

- Klebe S, Leigh J, Henderson DW, Nurminen M. Asbestos, Smoking and Lung Cancer: An Update. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Dec 30;17(1):258. [CrossRef]

- van Zandwijk N, Frank AL, Reid G, Dimitri Røe O, Amos CI. Asbestos-Related lung Cancer: An underappreciated oncological issue. Lung Cancer. 2024 Aug;194:107861. [CrossRef]

- Saracino L, Zorzetto M, Inghilleri S, Pozzi E, Stella GM. Non-neuronal cholinergic system in airways and lung cancer susceptibility. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2013 Aug;2(4):284-94. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta P, Rizwani W, Pillai S, Kinkade R, Kovacs M, Rastogi S, Banerjee S, Carless M, Kim E, Coppola D, Haura E, Chellappan S. Nicotine induces cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a variety of human cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2009 Jan 1;124(1):36-45. [CrossRef]

- Di Cello F, Flowers VL, Li H, Vecchio-Pagán B, Gordon B, Harbom K, Shin J, Beaty R, Wang W, Brayton C, Baylin SB, Zahnow CA. Cigarette smoke induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition and increases the metastatic ability of breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2013 Aug 6;12:90. [CrossRef]

- Prashanth N, Meghana P, Sandeep Kumar Jain R, Pooja S Rajaput, Satyanarayan N D, Raja Naika H, Kumaraswamy H M. Nicotine promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition and gemcitabine resistance via hENT1/RRM1 signalling in pancreatic cancer and chemosensitizing effects of Embelin-a naturally occurring benzoquinone. Sci Total Environ. 2024 Mar 1;914:169727. [CrossRef]

- Chen PC, Lee WY, Ling HH, Cheng CH, Chen KC, Lin CW. Activation of fibroblasts by nicotine promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and motility of breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2018 Jun;233(6):4972-4980. [CrossRef]

- Dinicola S, Masiello MG, Proietti S, Coluccia P, Fabrizi G, Catizone A, Ricci G, de Toma G, Bizzarri M, Cucina A. Nicotine increases colon cancer cell migration and invasion through epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT): COX-2 involvement. J Cell Physiol. 2018 Jun;233(6):4935-4948.

- Raveendran M, Senthil D, Utama B, Shen Y, Dudley D, Wang J, Zhang Y, Wang XL. Cigarette suppresses the expression of P4H[alpha] and vascular collagen production. Biochem Biophys Res Com. 2004;323:592–598. [CrossRef]

- Lemaître V, Dabo AJ, D'Armiento J. Cigarette smoke components induce matrix metalloproteinase-1 in aortic endothelial cells through inhibition of mTOR signaling. Toxicological Sciences. 2011;123:542–549. [CrossRef]

- Arif B, Garcia-Fernandez F, Ennis TL, Jin J, Davis EC, Thompson RW, Curci JA. Novel mechanism of aortic aneurysm development in mice associated with smoking and leukocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2901–2909. [CrossRef]

- Liao S, Curci JA, Kelley BJ, Sicard GA, Thompson RW. Accelerated replicative senescence of medial smooth muscle cells derived from abdominal aortic aneurysms compared to the adjacent inferior mesenteric artery. J Surg Res. 2000;92:85–95. [CrossRef]

- Polytarchou C, Iliopoulos D, Hatziapostolou M, Kottakis F, Maroulakou I, Struhl K, Tsichlis PN. Akt2 regulates all Akt isoforms and promotes resistance to hypoxia through induction of miR-21 upon oxygen deprivation. Cancer Research. 2011;71:4720–4731. [CrossRef]

- Husgafvel-Pursiainen, K. Genotoxicity of environmental tobacco smoke: a review. Mutat Res. 2004 Nov;567(2-3):427-45. [CrossRef]

- Stannard L, Doak SH, Doherty A, Jenkins GJ. Is Nickel Chloride really a Non-Genotoxic Carcinogen? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017 Sep;121 Suppl 3:10-15. [CrossRef]

- Jianlin L, Guohai C, Guojun Z, Jian J, Fangfang H, Juanjuan X, Shu Z, Zhijian C, Wei J, Yezhen L, Xiaoxue L, Jiliang H. Assessing cytogenotoxicity of cigarette smoke condensates using three in vitro assays. Mutat Res. 2009 Jun-Jul;677(1-2):21-6. [CrossRef]

- Messner B, Frotschnig S, Steinacher-Nigisch A, Winter B, Eichmair E, Gebetsberger J, Schwaiger S, Ploner C, Laufer G, Bernhard D. Apoptosis and necrosis: two different outcomes of cigarette smoke condensate-induced endothelial cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2012 Nov 15;3(11):e424. [CrossRef]

- Khulan B, Ye K, Shi MK, Waldman S, Marsh A, Siddiqui T, Okorozo A, Desai A, Patel D, Dobkin J, Sadoughi A, Shah C, Gera S, Peter Y, Liao W, Vijg J, Spivack SD. Normal bronchial field basal cells show persistent methylome-wide impact of tobacco smoking, including in known cancer genes. Epigenetics. 2025 Dec;20(1):2466382. [CrossRef]

- Herzog C, Jones A, Evans I, Raut JR, Zikan M, Cibula D, Wong A, Brenner H, Richmond RC, Widschwendter M. Cigarette Smoking and E-cigarette Use Induce Shared DNA Methylation Changes Linked to Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2024 Jun 4;84(11):1898-1914. [CrossRef]

- Essogmo FE, Zhilenkova AV, Tchawe YSN, Owoicho AM, Rusanov AS, Boroda A, Pirogova YN, Sangadzhieva ZD, Sanikovich VD, Bagmet NN, Sekacheva MI. Cytokine Profile in Lung Cancer Patients: Anti-Tumor and Oncogenic Cytokines. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Nov 13;15(22):5383. [CrossRef]

- Cook JH, Melloni GEM, Gulhan DC, Park PJ, Haigis KM. The origins and genetic interactions of KRAS mutations are allele- and tissue-specific. Nat Commun. 2021 Mar 22;12(1):1808. [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan É, Keogh A, Henderson B, Finn SP, Gray SG, Gately K. Treatment Strategies for KRAS-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Mar 7;15(6):1635. [CrossRef]

- Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ, Falchook GS, Wolf J, Italiano A, Schuler M, Borghaei H, Barlesi F, Kato T, Curioni-Fontecedro A, Sacher A, Spira A, Ramalingam SS, Takahashi T, Besse B, Anderson A, Ang A, Tran Q, Mather O, Henary H, Ngarmchamnanrith G, Friberg G, Velcheti V, Govindan R. Sotorasib for Lung Cancers with KRASp.G12C Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jun 24;384(25):2371-2381. [CrossRef]

- Jänne PA, Riely GJ, Gadgeel SM, Heist RS, Ou SI, Pacheco JM, Johnson ML, Sabari JK, Leventakos K, Yau E, Bazhenova L, Negrao MV, Pennell NA, Zhang J, Anderes K, Der-Torossian H, Kheoh T, Velastegui K, Yan X, Christensen JG, Chao RC, Spira AI. Adagrasib in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring a KRASG12C Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jul 14;387(2):120-131. [CrossRef]

- Sidaway, P. Sotorasib effective in KRAS-mutant NSCLC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021 Aug;18(8):470. [CrossRef]

- Longo DL, Rosen N. Targeting Oncogenic RAS Protein. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jul 14;387(2):184-186. [CrossRef]

- Le Calvez F, Mukeria A, Hunt JD, Kelm O, Hung RJ, Tanière P, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Zaridze DG, Hainaut P. TP53 and KRAS mutation load and types in lung cancers in relation to tobacco smoke: distinct patterns in never, former, and current smokers. Cancer Res. 2005 Jun 15;65(12):5076-83. [CrossRef]

- Joehanes R, Just AC, Marioni RE, Pilling LC, Reynolds LM, Mandaviya PR, Guan W, Xu T, Elks CE, Aslibekyan S, Moreno-Macias H, Smith JA, Brody JA, Dhingra R, Yousefi P, Pankow JS, Kunze S, Shah SH, McRae AF, Lohman K, Sha J, Absher DM, Ferrucci L, Zhao W, Demerath EW, Bressler J, Grove ML, Huan T, Liu C, Mendelson MM, Yao C, Kiel DP, Peters A, Wang-Sattler R, Visscher PM, Wray NR, Starr JM, Ding J, Rodriguez CJ, Wareham NJ, Irvin MR, Zhi D, Barrdahl M, Vineis P, Ambatipudi S, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Schwartz J, Colicino E, Hou L, Vokonas PS, Hernandez DG, Singleton AB, Bandinelli S, Turner ST, Ware EB, Smith AK, Klengel T, Binder EB, Psaty BM, Taylor KD, Gharib SA, Swenson BR, Liang L, DeMeo DL, O'Connor GT, Herceg Z, Ressler KJ, Conneely KN, Sotoodehnia N, Kardia SL, Melzer D, Baccarelli AA, van Meurs JB, Romieu I, Arnett DK, Ong KK, Liu Y, Waldenberger M, Deary IJ, Fornage M, Levy D, London SJ. Epigenetic Signatures of Cigarette Smoking. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016 Oct;9(5):436-447. [CrossRef]

- Raso MG, Wistuba II. Molecular pathogenesis of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and a proposal for tissue banking to facilitate identification of new biomarkers. J Thorac Oncol. 2007 Jul;2(7 Suppl 3):S128-35. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto T, Suzuki Y, Fujishita T, Kitahara H, Shimamatsu S, Kohno M, Morodomi Y, Kawano D, Maehara Y. The prognostic impact of the amount of tobacco smoking in non-small cell lung cancer--differences between adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2014 Aug;85(2):125-30. [CrossRef]

- Maeda R, Yoshida J, Ishii G, Hishida T, Nishimura M, Nagai K. The prognostic impact of cigarette smoking on patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011 Apr;6(4):735-42. [CrossRef]

- Lee JY, Bhandare RR, Boddu SHS, Shaik AB, Saktivel LP, Gupta G, Negi P, Barakat M, Singh SK, Dua K, Chellappan DK. Molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of tumour suppressor genes in lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024 Apr;173:116275. [CrossRef]

- Tao S, Pu Y, Yang EJ, Ren G, Shi C, Chen LJ, Chen L, Shim JS. Inhibition of GSK3β is synthetic lethal with FHIT loss in lung cancer by blocking homologous recombination repair. Exp Mol Med. 2025 Feb;57(1):167-183. [CrossRef]

- Spira A, Beane J, Shah V, Liu G, Schembri F, Yang X, Palma J, Brody JS. Effects of cigarette smoke on the human airway epithelial cell transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jul 6;101(27):10143-8. [CrossRef]

- Spira A, Beane JE, Shah V, Steiling K, Liu G, Schembri F, Gilman S, Dumas YM, Calner P, Sebastiani P, Sridhar S, Beamis J, Lamb C, Anderson T, Gerry N, Keane J, Lenburg ME, Brody JS. Airway epithelial gene expression in the diagnostic evaluation of smokers with suspect lung cancer. Nat Med. 2007 Mar;13(3):361-6. [CrossRef]

- Castaldi P, Sauler M. Cigarette Smoking and the Airway Epithelium: Characterizing Changes in Gene Expression over Time. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023 Oct 1;208(7):749-750. [CrossRef]

- Lin BC, Li QY, Tian L, Liu HL, Liu XH, Shi Y, He C, Ding SS, Yan J, Li K, Bian LP, Lai WQ, Zhang W, Li X, Xi ZG. Identification of apoptosis-associated protein factors distinctly expressed in cigarette smoke condensate-exposed airway bronchial epithelial cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2020 Mar;34(3):e22444. [CrossRef]

- Alamgeer M, Peacock CD, Matsui W, Ganju V, Watkins DN. Cancer stem cells in lung cancer: Evidence and controversies. Respirology. 2013 Jul;18(5):757-64. [CrossRef]

- Chu X, Tian W, Ning J, Xiao G, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Zhai Z, Tanzhu G, Yang J, Zhou R. Cancer stem cells: advances in knowledge and implications for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Jul 5;9(1):170. [CrossRef]

- Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 21;355(12):1253-61. [CrossRef]

- Bomken S, Fiser K, Heidenreich O, Vormoor J. Understanding the cancer stem cell. Br J Cancer. 2010 Aug 10;103(4):439-45. [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen L, Sprick MR, Kemper K, Stassi G, Medema JP. Cancer stem cells--old concepts, new insights. Cell Death Differ. 2008 Jun;15(6):947-58. [CrossRef]

- Alam H, Sehgal L, Kundu ST, Dalal SN, Vaidya MM. Novel function of keratins 5 and 14 in proliferation and differentiation of stratified epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2011 Nov;22(21):4068-78. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka Y, Yamaguchi M, Hirai S, Sumi T, Tada M, Saito A, Chiba H, Kojima T, Watanabe A, Takahashi H, Sakuma Y. Characterization of distal airway stem-like cells expressing N-terminally truncated p63 and thyroid transcription factor-1 in the human lung. Exp Cell Res. 2018 Nov 15;372(2):141-149. [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra PS, Bourdin A. Club cells, CC10 and self-control at the epithelial surface. Eur Respir J. 2014 Oct;44(4):831-2. [CrossRef]

- Kathiriya JJ, Brumwell AN, Jackson JR, Tang X, Chapman HA. Distinct Airway Epithelial Stem Cells Hide among Club Cells but Mobilize to Promote Alveolar Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 Mar 5;26(3):346-358.e4. [CrossRef]

- Kathiriya JJ, Brumwell AN, Jackson JR, Tang X, Chapman HA. Distinct Airway Epithelial Stem Cells Hide among Club Cells but Mobilize to Promote Alveolar Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 Mar 5;26(3):346-358.e4. [CrossRef]

- Salwig I, Spitznagel B, Vazquez-Armendariz AI, Khalooghi K, Guenther S, Herold S, Szibor M, Braun T. Bronchioalveolar stem cells are a main source for regeneration of distal lung epithelia in vivo. EMBO J. 2019 Jun 17;38(12):e102099. [CrossRef]

- Campo-Trapero J, Cano-Sánchez J, Palacios-Sánchez B, Sánchez-Gutierrez JJ, González-Moles MA, Bascones-Martínez A. Update on molecular pathology in oral cancer and precancer. Anticancer Res. 2008 Mar-Apr;28(2B):1197-205.

- Vairaktaris E, Spyridonidou S, Papakosta V, Vylliotis A, Lazaris A, Perrea D, Yapijakis C, Patsouris E. The hamster model of sequential oral oncogenesis. Oral Oncol. 2008 Apr;44(4):315-24. [CrossRef]

- Willenbrink TJ, Ruiz ES, Cornejo CM, Schmults CD, Arron ST, Jambusaria-Pahlajani A. Field cancerization: Definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep;83(3):709-717. [CrossRef]

- SLAUGHTER DP, SOUTHWICK HW, SMEJKAL W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953 Sep;6(5):963-8. [CrossRef]

- Simple M, Suresh A, Das D, Kuriakose MA. Cancer stem cells and field cancerization of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2015 Jul;51(7):643-51. [CrossRef]

- Aramini B, Masciale V, Grisendi G, Bertolini F, Maur M, Guaitoli G, Chrystel I, Morandi U, Stella F, Dominici M, Haider KH. Dissecting Tumor Growth: The Role of Cancer Stem Cells in Drug Resistance and Recurrence. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Feb 15;14(4):976. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura H, Okudela K, Yazawa T, Sato H, Shimoyamada H. Cancer stem cell: implications in cancer biology and therapy with special reference to lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2009 Dec;66(3):275-81. [CrossRef]

- Tura-Ceide O, Lobo B, Paul T, Puig-Pey R, Coll-Bonfill N, García-Lucio J, Smolders V, Blanco I, Barberà JA, Peinado VI. Cigarette smoke challenges bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell capacities in guinea pig. Respir Res. 2017 Mar 23;18(1):50. [CrossRef]

- Zhu F, Guo GH, Chen W, Wang NY. Effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells engraftment on vascular endothelial cell growth factor in lung tissue and plasma at early stage of smoke inhalation injury. World J Emerg Med. 2010;1(3):224-8.

- Chen JT, Lin TS, Chow KC, Huang HH, Chiou SH, Chiang SF, Chen HC, Chuang TL, Lin TY, Chen CY. Cigarette smoking induces overexpression of hepatocyte growth factor in type II pneumocytes and lung cancer cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006 Mar;34(3):264-73. [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama R, Aoshiba K, Furukawa K, Saito M, Kataba H, Nakamura H, Ikeda N. Nicotine enhances hepatocyte growth factor-mediated lung cancer cell migration by activating the α7 nicotine acetylcholine receptor and phosphoinositide kinase-3-dependent pathway. Oncol Lett. 2016 Jan;11(1):673-677. [CrossRef]

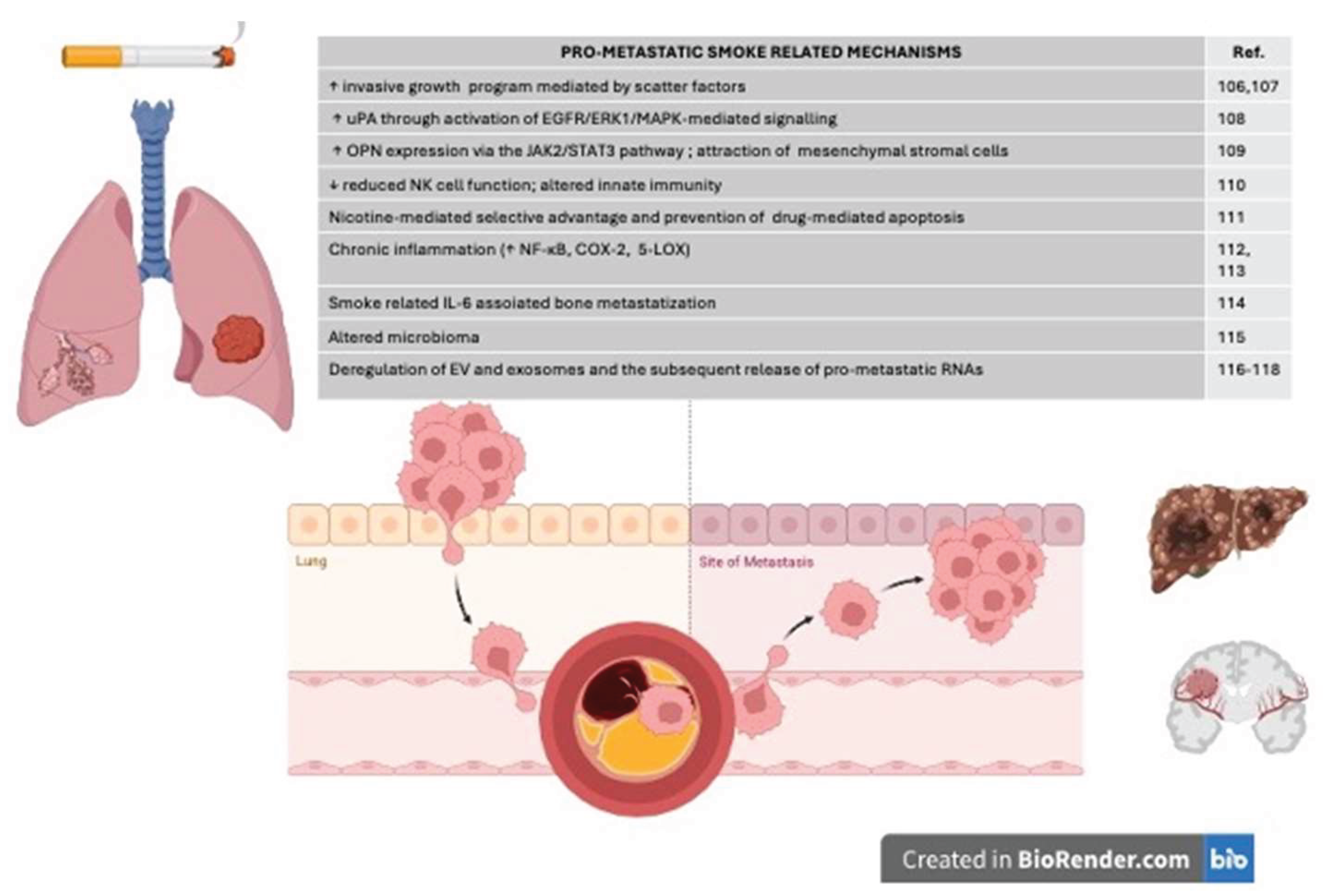

- Du B, Leung H, Khan KM, Miller CG, Subbaramaiah K, Falcone DJ, Dannenberg AJ. Tobacco smoke induces urokinase-type plasminogen activator and cell invasiveness: evidence for an epidermal growth factor receptor dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2007 Sep 15;67(18):8966-72. [CrossRef]

- Jiang YJ, Chao CC, Chang AC, Chen PC, Cheng FJ, Liu JF, Liu PI, Huang CL, Guo JH, Huang WC, Tang CH. Cigarette smoke-promoted increases in osteopontin expression attract mesenchymal stem cell recruitment and facilitate lung cancer metastasis. J Adv Res. 2022 Nov;41:77-87. [CrossRef]

- Jung YS, Park JH, Park DI, Sohn CI, Lee JM, Kim TI. Impact of Smoking on Human Natural Killer Cell Activity: A Large Cohort Study. J Cancer Prev. 2020 Mar 30;25(1):13-20. [CrossRef]

- Dinicola S, Morini V, Coluccia P, Proietti S, D'Anselmi F, Pasqualato A, Masiello MG, Palombo A, De Toma G, Bizzarri M, Cucina A. Nicotine increases survival in human colon cancer cells treated with chemotherapeutic drugs. Toxicol In Vitro. 2013 Dec;27(8):2256-63. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Zhang J, Sun W, Cao J, Ma Z. COX-2 in lung cancer: Mechanisms, development, and targeted therapies. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2024 Mar 12;10(4):281-292. [CrossRef]

- Ahn KS, Aggarwal BB. Transcription factor NF-kappaB: a sensor for smoke and stress signals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005 Nov;1056:218-33. [CrossRef]

- Guo JH, Thuong LHH, Jiang YJ, Huang CL, Huang YW, Cheng FJ, Liu PI, Liu CL, Huang WC, Tang CH. Cigarette smoke promotes IL-6-dependent lung cancer migration and osteolytic bone metastasis. Int J Biol Sci. 2024 Jun 3;20(9):3257-3268. [CrossRef]

- Zheng L, Sun R, Zhu Y, Li Z, She X, Jian X, Yu F, Deng X, Sai B, Wang L, Zhou W, Wu M, Li G, Tang J, Jia W, Xiang J. Lung microbiome alterations in NSCLC patients. Sci Rep. 2021 Jun 3;11(1):11736. [CrossRef]

- Wu F, Yin Z, Yang L, Fan J, Xu J, Jin Y, Yu J, Zhang D, Yang G. Smoking Induced Extracellular Vesicles Release and Their Distinct Properties in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Cancer. 2019 Jun 9;10(15):3435-3443. [CrossRef]

- Jiang C, Zhang N, Hu X, Wang H. Tumor-associated exosomes promote lung cancer metastasis through multiple mechanisms. Mol Cancer. 2021 Sep 13;20(1):117. [CrossRef]

- Liang Z, Fang S, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Xu Y, Qian H, Geng H. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Gastric Cancer Cell Exosomes Affected the Fate of Surrounding Normal Cells via the Circ0000670/Wnt/β-Catenin Axis. Toxics. 2023 May 17;11(5):465. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, Miller ML, Rekhtman N, Moreira AL, Ibrahim F, Bruggeman C, Gasmi B, Zappasodi R, Maeda Y, Sander C, Garon EB, Merghoub T, Wolchok JD, Schumacher TN, Chan TA. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015 Apr 3;348(6230):124-8. [CrossRef]

- Sun S, Schiller JH, Gazdar AF. Lung cancer in never smokers--a different disease. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007 Oct;7(10):778-90. [CrossRef]

- Lam DC, Liam CK, Andarini S, Park S, Tan DSW, Singh N, Jang SH, Vardhanabhuti V, Ramos AB, Nakayama T, Nhung NV, Ashizawa K, Chang YC, Tscheikuna J, Van CC, Chan WY, Lai YH, Yang PC. Lung Cancer Screening in Asia: An Expert Consensus Report. J Thorac Oncol. 2023 Oct;18(10):1303-1322. [CrossRef]

- Luo G, Zhang Y, Rumgay H, Morgan E, Langselius O, Vignat J, Colombet M, Bray F. Estimated worldwide variation and trends in incidence of lung cancer by histological subtype in 2022 and over time: a population-based study. Lancet Respir Med. 2025 Apr;13(4):348-363. [CrossRef]

- Tang FH, Wong HYT, Tsang PSW, Yau M, Tam SY, Law L, Yau K, Wong J, Farah FHM, Wong J. Recent advancements in lung cancer research: a narrative review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2025 Mar 31;14(3):975-990. [CrossRef]

- Thaxton C, Kano M, Mendes-Pinto D, Navarro TP, Nishibe T, Dardik A. Implications of preoperative arterial stiffness for patients treated with endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. JVS Vasc Sci. 2024 May 21;5:100209. [CrossRef]

- Westerhof N, Lankhaar JW, Westerhof BE. The arterial Windkessel. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2009 Feb;47(2):131-41. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz JA, Keagy BA, Johnson G Jr. Determination of whole blood apparent viscosity: experience with a new hemorheologic technique. J Surg Res. 1988 Aug;45(2):238-47. [CrossRef]

- Baieth, HE. Physical parameters of blood as a non - newtonian fluid. Int J Biomed Sci. 2008 Dec;4(4):323-9.

- Lee HJ, Kim YW, Shin SY, Lee SL, Kim CH, Chung KS, Lee JS. A Physics-Integrated Deep Learning Approach for Patient-Specific Non-Newtonian Blood Viscosity Assessment using PPG. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2025 Mar 23;265:108740. [CrossRef]

- Willigendael EM, Teijink JA, Bartelink ML, Kuiken BW, Boiten J, Moll FL, Büller HR, Prins MH. Influence of smoking on incidence and prevalence of peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2004 Dec;40(6):1158-65. [CrossRef]

- Lu L, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Meta-analysis of the association between cigarette smoking and peripheral arterial disease. Heart. 2014 Mar;100(5):414-23. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Zhao T, Geng K, Yuan G, Chen Y, Xu Y. Smoking and the Pathophysiology of Peripheral Artery Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Aug 27;8:704106. [CrossRef]

- Leone A, Landini L. Vascular pathology from smoking: look at the microcirculation! Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013 Jul;11(4):524-30. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead AK, Erwin AP, Yue X. Nicotine and vascular dysfunction. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2021 Apr;231(4):e13631. [CrossRef]

- Lietz M, Berges A, Lebrun S, Meurrens K, Steffen Y, Stolle K, Schueller J, Boue S, Vuillaume G, Vanscheeuwijck P, Moehring M, Schlage W, De Leon H, Hoeng J, Peitsch M. Cigarette-smoke-induced atherogenic lipid profiles in plasma and vascular tissue of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice are attenuated by smoking cessation. Atherosclerosis. 2013 Jul;229(1):86-93. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi Y, Matsuno S, Kagota S, Haginaka J, Kunitomo M. Oxidants in cigarette smoke extract modify low-density lipoprotein in the plasma and facilitate atherogenesis in the aorta of Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 2001 May;156(1):109-17. [CrossRef]

- Centner AM, Bhide PG, Salazar G. Nicotine in Senescence and Atherosclerosis. Cells. 2020 Apr 22;9(4):1035. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead AK, Erwin AP, Yue X. Nicotine and vascular dysfunction. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2021 Apr;231(4):e13631. [CrossRef]

- Siasos G, Tsigkou V, Kokkou E, Oikonomou E, Vavuranakis M, Vlachopoulos C, Verveniotis A, Limperi M, Genimata V, Papavassiliou AG, Stefanadis C, Tousoulis D. Smoking and atherosclerosis: mechanisms of disease and new therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21(34):3936-48. [CrossRef]

- Gimbrone MA Jr, García-Cardeña G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016 Feb 19;118(4):620-36. [CrossRef]

- Aceto, N. Aceto N. Bring it on: blood-based analysis of circulating tumor cells in lung cancer. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12(12):e12802.

- Li F, Tiede C, Massi D, Campaner E, Calorini L, Kohlhammer H, et al. Fluid shear stress regulates epithelial–mesenchymal transition via JNK signaling pathway in circulating tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;533(4):1095–1100.

- Zhang J, Qin Y, Fan J, Zhou J, Zhang Y, Zhong W, et al. Shear stress-induced nuclear expansion through histone acetylation promotes survival of suspended tumor cells. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):2494.

- Krog BL, Henry MD. Biomechanical regulation of CTC metastasis in lung cancer. Biophys J. 2018;115(2):186–195.

- Kurma K, Alix-Panabières C. Platelet–CTC interactions: mechanisms and implications in metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(4):439–452.

- Valastyan S, Weinberg RA. Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell. 2011;147(2):275–292.

- Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the 'seed and soil' hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):453–458.

- Szczerba BM, Castro-Giner F, Vetter M, et al. Neutrophils escort circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature. 2019;566(7745):553–557.

- Mitchell MJ, King MR. Fluid shear stress sensitizes cancer cells to receptor-mediated apoptosis via trimeric death receptors. New J Phys. 2013;15:015008.

- Chien S. Mechanotransduction and endothelial cell homeostasis: the wisdom of the cell. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(3):H1209–H1224.

- Au SH, Storey BD, Moore JC, et al. Clusters of circulating tumor cells traverse capillary-sized vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(18):4947–4952.

- Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):576–590.

- Roh-Johnson M, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Patsialou A, et al. Macrophage contact induces RhoA GTPase signaling to trigger tumor cell intravasation. Cell. 2014;158(5):1045–1059.

- Gimbrone MA Jr, García-Cardeña G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118(4):620–636.

- Pries AR, Secomb TW. Microvascular blood viscosity in vivo and the endothelial surface layer. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(6):H2657–H2664.

- Chiu JJ, Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(1):327–387.

- Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(9):678–689.

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, et al. The prevalence and associated factors of abdominal aortic aneurysm detected through screening. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(6):441–449.

- Rzucidlo EM, Powell RJ. Arterial aneurysms in smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a common pathophysiologic link. Vasc Med. 2009;14(3):195–204.

- Bluestein D, Chandran KB, Manning KB. Towards non-thrombogenic performance of blood recirculating devices. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(3):1236–1256.

- Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, et al. Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(25):2379–2393.

- Hynes RO. The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science. 2009;326(5957):1216–1219.

- Vorp DA, Lee PC, Wang DH, Makaroun MS, Nemoto EM, Ogawa S, Webster MW. Association of intraluminal thrombus in abdominal aortic aneurysm with local hypoxia and wall weakening. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34(2):291–299.

- Demers M, Wagner DD. NETosis: a new factor in tumor progression and cancer-associated thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40(3):277–283.

- Park J, Wysocki RW, Amoozgar Z, et al. Cancer cells induce metastasis-supporting neutrophil extracellular DNA traps. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(361):361ra138.

- Les AS, Shadden SC, Figueroa CA, et al. Quantification of hemodynamic wall shear stress in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms using computational fluid dynamics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(4):1040–1053.

- Fillinger MF, Marra SP, Raghavan ML, Kennedy FE. Prediction of rupture risk in abdominal aortic aneurysm during observation: wall stress versus diameter. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(4):724–732.

- Alix-Panabières C, Pantel K. Liquid biopsy: from discovery to clinical application. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(4):858–873.

- Pfister G, Wang Y, Mehta K, et al. Vascular-targeted therapies: a new approach to fighting metastasis? Trends Mol Med. 2020;26(4):401–414.

- Stroka KM, Jiang H, Chen SH, Tong Z, Wirtz D, Sun SX, Konstantopoulos K. Water permeation drives tumor cell migration in confined microenvironments. Cell. 2014;157(3):611–623.

- Polacheck WJ, Charest JL, Kamm RD. Interstitial flow influences direction of tumor cell migration through competing mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(27):11115–11120.

- Ma H, Wells A, Wei L, Li Y, Yu F. Emerging microfluidic platforms for cancer metastasis research. Trends Biotechnol. 2020;38(6):556–572.

- Les AS, Shadden SC, Figueroa CA, et al. Quantification of hemodynamic wall shear stress in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms using computational fluid dynamics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(4):1040–1053.

- Vorp DA, Lee PC, Wang DH, Makaroun MS, Nemoto EM, Ogawa S, Webster MW. Association of intraluminal thrombus in abdominal aortic aneurysm with local hypoxia and wall weakening. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34(2):291–299.

- Les AS, Shadden SC, Figueroa CA, et al. Quantification of hemodynamic wall shear stress in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms using computational fluid dynamics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(4):1040–1053.

- Polacheck WJ, Charest JL, Kamm RD. Interstitial flow influences direction of tumor cell migration through competing mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(27):11115–11120.

- Ma H, Wells A, Wei L, Li Y, Yu F. Emerging microfluidic platforms for cancer metastasis research. Trends Biotechnol. 2020;38(6):556–572.

- Pan C, Kumar C, Bohl M, Wilkins DE, Gupta N, Bazan NG. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides suppress lung tumor growth by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages. Mol Med. 2017;23(1):79–88. [CrossRef]

- Dong Z, Wang Y, Weng H, Wang B. Apolipoprotein E enhances lung cancer metastasis by interacting with endothelial LRP1 receptors. Cancer Lett. 2018;431:157–167. [CrossRef]

- Kotlyarov, S. High-Density Lipoproteins: A Role in Inflammation in COPD. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jul 23;23(15):8128. [CrossRef]

- Mazzuca P, Carloni A, Cazzato F, et al. Tobacco smoke and the vascular endothelium: from inflammation to transformation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):7755.

- Rzucidlo EM, Powell RJ. Arterial aneurysms in smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a common pathophysiologic link. Vasc Med. 2009;14(3):195–204.

- Pfister G, Wang Y, Mehta K, et al. Vascular-targeted therapies: a new approach to fighting metastasis? Trends Mol Med. 2020;26(4):401–414.

- Tibuakuu M, Kamimura D, Kianoush S, DeFilippis AP, Al Rifai M, Reynolds LM, White WB, Butler KR, Mosley TH, Turner ST, Kullo IJ, Hall ME, Blaha MJ. The association between cigarette smoking and inflammation: The Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy (GENOA) study. PLoS One. 2017 Sep 18;12(9):e0184914. [CrossRef]

- Elisia I, Lam V, Cho B, Hay M, Li MY, Yeung M, Bu L, Jia W, Norton N, Lam S, Krystal G. The effect of smoking on chronic inflammation, immune function and blood cell composition. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 10;10(1):19480. [CrossRef]

- Leduc C, Antoni D, Charloux A, Falcoz PE, Quoix E. Comorbidities in the management of patients with lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2017 Mar 29;49(3):1601721. [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov LB, Ju YS, Haase K, Van Loo P, Martincorena I, Nik-Zainal S, Totoki Y, Fujimoto A, Nakagawa H, Shibata T, Campbell PJ, Vineis P, Phillips DH, Stratton MR. Mutational signatures associated with tobacco smoking in human cancer. Science. 2016 Nov 4;354(6312):618-622. [CrossRef]

- Warren GW, Sobus S, Gritz ER. The biological and clinical effects of smoking by patients with cancer and strategies to implement evidence-based tobacco cessation support. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Nov;15(12):e568-80. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Huang S, Zhu Z, Gatt A, Liu J. E-selectin in vascular pathophysiology. Front Immunol. 2024 Jul 19;15:1401399. [CrossRef]

- Turhan H, Saydam GS, Erbay AR, Ayaz S, Yasar AS, Aksoy Y, Basar N, Yetkin E. Increased plasma soluble adhesion molecules; ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin levels in patients with slow coronary flow. Int J Cardiol. 2006 Apr 4;108(2):224-30. [CrossRef]

- Park-Windhol C, D'Amore PA. Disorders of Vascular Permeability. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016 May 23;11:251-81. [CrossRef]

- Demers M, Wagner DD. NETosis: a new factor in tumor progression and cancer-associated thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40(3):277–283.

- Roh-Johnson M, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Patsialou A, et al. Macrophage contact induces RhoA GTPase signaling to trigger tumor cell intravasation. Cell. 2014;158(5):1045–1059.

- Hargadon, KM. Tumor-altered dendritic cell function: implications for anti-tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2013 Jul 11;4:192. [CrossRef]

- Geindreau M, Bruchard M, Vegran F. Role of Cytokines and Chemokines in Angiogenesis in a Tumor Context. Cancers (Basel). 2022 May 16;14(10):2446. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan R, Subramanian J. Long-Term Survival by Number of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in PD-L1-Negative Metastatic NSCLC: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2025 Feb 3;8(2):e2457357. [CrossRef]

- Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018 Sep;8(9):1069-1086. [CrossRef]

- Braun A, Anders HJ, Gudermann T, Mammadova-Bach E. Platelet-Cancer Interplay: Molecular Mechanisms and New Therapeutic Avenues. Front Oncol. 2021 Jul 12;11:665534. [CrossRef]

- Lycan TW Jr, Norton DL, Ohar JA. COPD and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Cancer: A Literature Review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2024 Dec 9;19:2689-2703. [CrossRef]

- Pfister G, Wang Y, Mehta K, et al. Vascular-targeted therapies: a new approach to fighting metastasis? Trends Mol Med. 2020;26(4):401–414.

- Fillinger MF, Marra SP, Raghavan ML, Kennedy FE. Prediction of rupture risk in abdominal aortic aneurysm during observation: wall stress versus diameter. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(4):724–732.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).