Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. miRNA and Noncoding-RNA Sequencing, Differential Expression, Number of Reported Studies

| miRNA ID | Fold Change | p-Value | Role in MASLD | |

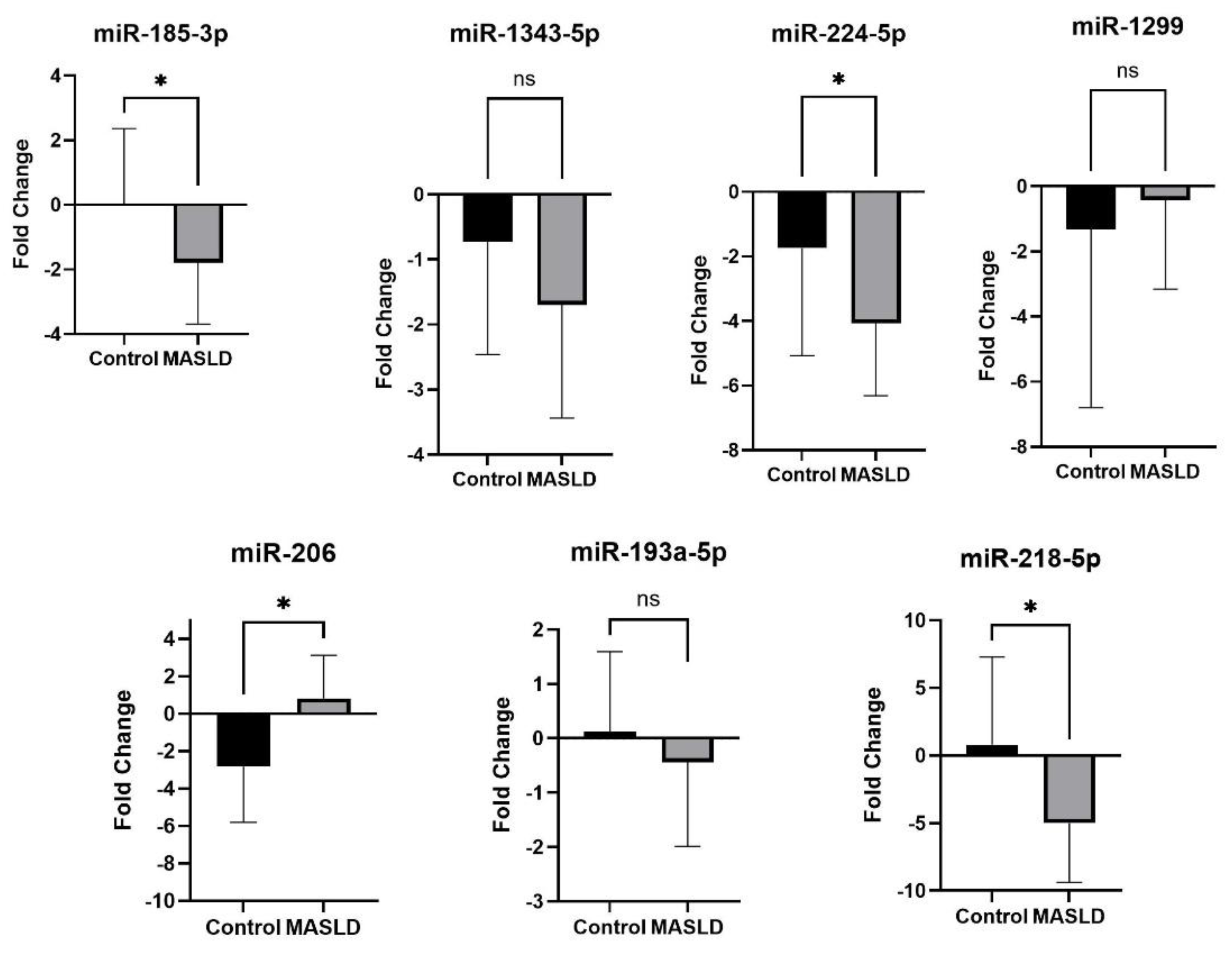

| miR-206 | 2.22±0.19 | 0.0353 | miR-206 regulates lipid metabolism and fibrosis in MASLD by downregulating FGF21 and modulating the MAPK pathway. | |

| miR-1343-5p | -3.98±2.50 | 0.0020 | miR-1343-5p contributes to MASLD by modulating the PI3K/Akt pathway, promoting hepatic lipid accumulation and inflammation. | |

| miR-224-5p | -2.65±0.52 | 0.0001 | miR-224-5p exacerbates MASLD by activating the TGF-β/Smad pathway, promoting liver fibrosis and inflammation. | |

| miR-1299 | -3.59±1.71 | 0.0055 | miR-1299 plays a role in MASLD by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thereby reducing hepatic fibrosis and lipid accumulation. | |

| miR-193a-5p | -1.79±0.26 | 0.0031 | miR-193a-5p contributes to MASLD by deactivating the JNK/c-Jun pathway, which reduces inflammation and hepatic injury. | |

| miR-185-3p | -2.59±1.06 | 0.0038 | miR-185-3p mitigates MASLD by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway, reducing inflammation and liver damage. | |

| miR-3960 | -1.64±0.95 | 0.0270 | miR-3960 contributes to MASLD by activating the SIRT1/AMPK pathway, promoting lipid metabolism and reducing hepatic steatosis. | |

2.3. Top Biofunctions, Canonical Pathways, and Network Analysis

2.4. qRT-PCR Validation of Differentially Expressed miRNAs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Particepants and Blood Sample Collection.

4.2. RNA Extraction and miRNA Library Preparation

4.3. Sequencing and Data Analysis

4.4. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)

4.5. qRT-PCR Validation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Afendy, M.; Fang, Y.; Younossi, Y.; Mir, H.; Srishord, M. Changes in the Prevalence of the Most Common Causes of Chronic Liver Diseases in the United States From 1988 to 2018. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N.; Younossi, Z.; LaVine, J.E.; Charlton, M.; Cusi, K.; Rinella, M.; Harrison, S.A.; Brunt, E.M.; Sanyal, A.J. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2021, 67, 328–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, A.M.; Day, C. Cause, Pathogenesis, and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, J.D.; Szczepaniak, L.S.; Dobbins, R.; Nuremberg, P.; Horton, J.D.; Cohen, J.C.; Grundy, S.M.; Hobbs, H.H. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: Impact of ethnicity. Hepatology 2004, 40, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, N.E.; Oji, S.; Mufti, A.R.; Browning, J.D.; Parikh, N.D.; Odewole, M.; Mayo, H.; Singal, A.G. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Prevalence, Severity, and Outcomes in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmalek, M.F.; Suzuki, A.; Guy, C.; Unalp-Arida, A.; Colvin, R.; Johnson, R.J.; Diehl, A.M. Ethnic differences in the histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2019, 50, 792–799. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, T.; Smith, C.I.; Loffredo, C.A.; Quartey, R.; Moses, G.; Howell, C.D.; Korba, B.; Kwabi-Addo, B.; Nunlee-Bland, G.; Rucker, L.R.; et al. Transcriptomics of MASLD Pathobiology in African American Patients in the Washington DC Area †. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, T.; Loffredo, C.A.; Simhadri, J.; Nunlee-Bland, G.; Korba, B.; Johnson, J.; Cotin, S.; Moses, G.; Quartey, R.; Howell, C.D.; et al. Insights on the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes as revealed by signature genomic classifiers in an African American population in the Washington, DC area. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2023, 39, e3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookoian, S.; Pirola, C.J. Genetic predisposition in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2018, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klett, D.; Moehle, C.; García-Rodríguez, J.L. MicroRNAs in NAFLD: Progress and perspectives. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Pirola, C.J.; Sookoian, S. Noncoding RNAs in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Molecular insights and therapeutic implications. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2020, 17, 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Estep, M.; Armistead, D.; Hossain, N.; Elarainy, H.; Goodman, Z.; Baranova, A.; Chandhoke, V.; Younossi, Z.M. Differential expression of miRNAs in the visceral adipose tissue of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 32, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-H.; Ampuero, J.; Gil-Gómez, A.; Montero-Vallejo, R.; Rojas, Á.; Muñoz-Hernández, R.; Gallego-Durán, R.; Romero-Gómez, M. miRNAs in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrese, M.; Cabrera, D.; Kalergis, A.M.; Feldstein, A.E. Innate Immunity and Inflammation in NAFLD/NASH. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, T.K.; Mondal, T.; Noreen, Z.; Johnson, J.; Nunlee-Bland, G.; Loffredo, C.A.; Korba, B.E.; Chandra, V.; Jana, S.S.; Kwabi-Addo, B.; et al. Developing non-invasive molecular markers for early risk assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Biomarkers Neuropsychiatry 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, T.; Noreen, Z.; Loffredo, C.A.; Johnson, J.; Bhatti, A.; Nunlee-Bland, G.; Quartey, R.; Howell, C.D.; Moses, G.; Nnanabu, T.; et al. Transcriptomic Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathways in a Pakistani Population. J. Alzheimer's Dis. Rep. 2024, 8, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, T.; Johnson, J.; Sur, T.K.; Loffredo, C.A.; Cotin, S.T.; Sahota, J.; Korbe, B.E.; Nunlee-Blnad, G.; Ghosh, S.G. Metabolic Dysfunction and Alzheimer’s Disease Risks in African Americans. Alzheimer's Dement. 2025, 20, e086476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulf, M.; Shunkina, D.; Komar, A.; Bograya, M.; Zatolokin, P.; Kirienkova, E.; Gazatova, N.; Kozlov, I.; Litvinova, L. Analysis of miRNAs Profiles in Serum of Patients With Steatosis and Steatohepatitis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leti, F.; Malenica, I.; Doshi, M.; Courtright, A.; Van Keuren-Jensen, K.; Legendre, C.; Still, C.D.; Gerhard, G.S.; DiStefano, J.K. High-throughput sequencing reveals altered expression of hepatic microRNAs in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease–related fibrosis. Transl. Res. 2015, 166, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, O.; Puri, P.; Eicken, C.; Contos, M.J.; Mirshahi, F.; Maher, J.W.; Kellum, J.M.; Min, H.; Luketic, V.A.; Sanyal, A.J. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with altered hepatic MicroRNA expression. Hepatology 2008, 48, 1810–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Otgonsuren, M.; Younoszai, Z.; Allawi, H.; Raybuck, B.; Younossi, Z. Circulating miRNA in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary artery disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016, 3, e000096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Shaker, O.G.; Khalil, M.A.F.; Abu-El-Azayem, A.K.; Samy, A.; Fathy, S.A.; AbdElguaad, M.M.K.; Mahmoud, F.A.M.; Erfan, R. Circulating miR-206, miR-181b, and miR-21 as promising biomarkers in hypothyroidism and their relationship to related hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1307512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tan, Q.-Q.; Tan, X.-R.; Li, S.-J.; Zhang, X.-X. Circ_0057558 promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating ROCK1/AMPK signaling through targeting miR-206. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Deng, Y.-Y.; Liu, H.-X.; Pu, Y. LncRNA MALAT1 Promotes PPARα/CD36-Mediated Hepatic Lipogenesis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Modulating miR-206/ARNT Axis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, Q.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Fang, W.; Ma, Z. miR-224-5p-enriched exosomes promote tumorigenesis by directly targeting androgen receptor in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2021, 23, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A.; Rutledge, B.; Damughatla, A.R.; Rasheed, M.; Naylor, P.; Mutchnick, M. Manifestation and Progression of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in a Predominately African American Population at a Multi-Specialty Healthcare Organization. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-J.; O Baumert, B.; Stratakis, N.; A Goodrich, J.; Wu, H.-T.; He, J.-X.; Zhao, Y.-Q.; Aung, M.T.; Wang, H.-X.; Eckel, S.P.; et al. Circulating microRNA expression and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescents with severe obesity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolzenburg, L.R.; Harris, A. Microvesicle-mediated delivery of miR-1343: impact on markers of fibrosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 371, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.; Leary, P.J.; Govaere, O.; Barter, M.J.; Charlton, S.H.; Cockell, S.J.; Tiniakos, D.; Zatorska, M.; Bedossa, P.; Brosnan, M.J.; et al. Increased serum miR-193a-5p during non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression: Diagnostic and mechanistic relevance. JHEP Rep. 2021, 4, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mens, M.M.J.; Abozaid, Y.J.; Bos, D.; Murad, S.D.; de Knegt, R.J.; Ikram, M.A.; Pan, Q.; Ghanbari, M. Circulatory microRNAs as potential biomarkers for fatty liver disease: the Rotterdam study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg, J.T.; Sohal, A.; Handa, P.; Maliken, B.D.; Kim, T.-K.; Wang, K.; Gochanour, E.; Li, Y.; Rose, J.B.; Nelson, J.E.; et al. Serum miRNA profiles are altered in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis receiving high-dose ursodeoxycholic acid. JHEP Rep. 2023, 5, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrooz, M.; Hajjarzadeh, S.; Kahroba, H.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Bastami, M. Expression pattern of miR-193a, miR122, miR155, miR-15a, and miR146a in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of children with obesity and their relation to some metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estep, M.; Armistead, D.; Hossain, N.; Elarainy, H.; Goodman, Z.; Baranova, A.; Chandhoke, V.; Younossi, Z.M. Differential expression of miRNAs in the visceral adipose tissue of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 32, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Bu, X.; Zhang, X.; Cui, L. Identification of a novel miRNA-based recurrence and prognosis prediction biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, T.; Yang, Y.; Cho, W.C.; Flynn, R.J.; Harandi, M.F.; Song, H.; Luo, X.; Zheng, Y. Interplays of liver fibrosis-associated microRNAs: Molecular mechanisms and implications in diagnosis and therapy. Genes Dis. 2022, 10, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tao, X.; Wang, M.; Cannon, R.D.; Chen, B.; Yu, X.; Qi, H.; Saffery, R.; Baker, P.N.; Zhou, X.; et al. Circulating extracellular vesicle-derived miR-1299 disrupts hepatic glucose homeostasis by targeting the STAT3/FAM3A axis in gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Meng, J.; Shen, X.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.-L.; Hassan, H.M.; Li, H.; He, Z.-X.; et al. Formononetin Mitigates Liver Fibrosis via Promoting Hepatic Stellate Cell Senescence and Inhibiting EZH2/YAP Axis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 22606–22620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Gui, S.; Yang, F.; Cao, Z.; Cheng, R.; Xia, X.; Li, C. The Roles and Mechanisms of lncRNAs in Liver Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 779606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, Biogenesis, Mechanism, and Function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'BRien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, B.; Yin, L.; Gao, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Han, X.; Qi, Y.; Liu, F.; et al. miR-218-5p promotes hepatic lipogenesis through targeting Elovl5 in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 226, 116411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanni, J.; D’sOuza, A.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Hansen, B.J.; Zakharkin, S.O.; Smith, M.; Hayward, C.; Whitson, B.A.; Mohler, P.J.; et al. Silencing miR-370-3p rescues funny current and sinus node function in heart failure. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdi, A.; Arefian, E.; Soleimani, M.; Ai, J.; Nahanmoghaddam, N.; Yousefi-Ahmadipour, A.; Ebrahimi-Barough, S. MicroRNA-4731-5p delivered by AD-mesenchymal stem cells induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in glioblastoma. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 8167–8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozuacik, D.; Akkoc, Y.; Ozturk, D.G.; Kocak, M. Autophagy-Regulating microRNAs and Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Rao, Y.; Pi, L.; Li, J. A review on the role of MiR-193a-5p in oncogenesis and tumor progression. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1543215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.-B.; Du, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ji, Z.-G.; Yang, P.-Q. MiR-1299 functions as a tumor suppressor to inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of prostate cancer by targeting NEK2. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, M.J.; Aygün, N.; Patel, N.K.; Krupa, O.; Liang, D.; Wolter, J.M.; Geschwind, D.H.; de la Torre-Ubieta, L.; Stein, J.L. MicroRNA-eQTLs in the developing human neocortex link miR-4707-3p expression to brain size. eLife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, B; Zhao, S; Kang, X; Wang, B. MicroRNA-133a-3p inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion in colorectal cancer by targeting AQP1 [retracted in: Oncol Lett. 2024 Nov 20;29(2):66. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2024.14812.]. Oncol Lett. 2021, 22(3), 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Yang, M.-M.; Yang, R.-H. MiRNA-365a-3p promotes the progression of osteoporosis by inhibiting osteogenic differentiation via targeting RUNX2. 2019, 23, 7766–7774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dingerdissen, H.; Gupta, S.; Kahsay, R.; Shanker, V.; Wan, Q.; Yan, C.; Mazumder, R. Identification of key differentially expressed MicroRNAs in cancer patients through pan-cancer analysis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 103, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Shi, R.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Ye, L.; Peng, L.; Guo, S.; He, J.; Yang, H.; Jiang, Y. miR-539-5p targets BMP2 to regulate Treg activation in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia through TGF-β/Smads/MAPK. Exp. Biol. Med. 2024, 249, 10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; Xu, X.; Gao, L.; Meng, Y.; Yan, J. MiR-369-5p inhibits the proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by down-regulating HOXA13 expression. Tissue Cell 2022, 74, 101721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wei, X.; Xu, L. miR-150 promotes the proliferation of lung cancer cells by targeting P53. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 2346–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Mannoor, K.; Gao, L.; Tan, A.; Guarnera, M.A.; Zhan, M.; Shetty, A.; Stass, S.A.; Xing, L.; Jiang, F. Characterization of microRNA transcriptome in lung cancer by next-generation deep sequencing. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 1208–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado-Flores, F.; Kaneko-Tarui, T.; Beyer, W.; Katz, J.; Chu, T.; Catalano, P.; Sadovsky, Y.; Hivert, M.-F.; O’tIerney-Ginn, P. Placental miR-3940-3p Is Associated With Maternal Insulin Resistance in Late Pregnancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 3526–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Liu, K.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, L.; Gao, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, N.; He, J. The role of miR-369-3p in proliferation and differentiation of preadipocytes in Aohan fine-wool sheep. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2023, 66, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, I.; Hsieh, T.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Kao, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-J. MicroRNA-452-5p regulates fibrogenesis via targeting TGF-β/SMAD4 axis in SCN5A-knockdown human cardiac fibroblasts. iScience 2024, 27, 110084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraldeschi, M.; Romano, S.; Giglio, S.; Romano, C.; Morena, E.; Mechelli, R.; Annibali, V.; Ubaldi, M.; Buscarinu, M.C.; Umeton, R.; et al. Circulating hsa-miR-323b-3p in Huntington's Disease: A Pilot Study. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 657973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Di, H.; Du, J.; Xu, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J. MiR-433-3p suppresses cell growth and enhances chemosensitivity by targeting CREB in human glioma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 5057–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Du, Y.; Deng, B.; Duan, Y. miR-379-5p regulates the proliferation, cell cycle, and cisplatin resistance of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by targeting ROR1. 2023, 15, 1626–1639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Josson, S.; Gururajan, M.; Hu, P.; Shao, C.; Chu, G.C.-Y.; Zhau, H.E.; Liu, C.; Lao, K.; Lu, C.-L.; Lu, Y.-T.; et al. miR-409-3p/-5p Promotes Tumorigenesis, Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition, and Bone Metastasis of Human Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 4636–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, J.; Qi, Q.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hu, L.; Chen, H.; Fang, X. miR-487b-3p Suppresses the Proliferation and Differentiation of Myoblasts by Targeting IRS1 in Skeletal Muscle Myogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 760–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, X.; Dou, L.; Huang, X.; Zhu, K.; Guo, J.; Yan, M.; Wang, S.; Man, Y.; Tang, W.; et al. miR-154-5p Functions as an Important Regulator of Angiotensin II-Mediated Heart Remodeling. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Bao, D.; Ye, Z.; Cao, B.; Jin, G.; Lu, Z.; Chen, J. miR-3195 suppresses the malignant progression of osteosarcoma cells via targeting SOX4. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Song, X.; Wang, K.; Zheng, B.; Lin, Q.; Yu, M.; Xie, L.; Chen, L.; Song, X. Plasma exosomal miR-320d, miR-4479, and miR-6763-5p as diagnostic biomarkers in epithelial ovarian cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 986343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z. miR-196a-5p promotes metastasis of colorectal cancer via targeting IκBα. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Tan, G.; Wang, Z. FZD1/KLF10-hsa-miR-4762-5p/miR-224-3p-circular RNAs axis as prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for glioblastoma: a comprehensive report. BMC Med Genom. 2023, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, J.; Zeng, G.; Pang, J.; Zheng, X.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J. MiR-129-5p inhibits liver cancer growth by targeting calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (CAMK4). Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilian, S.; Imani, S.Z.H.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. Emerging roles and mechanisms of miR-206 in human disorders: a comprehensive review. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, K.; Li, F.; Wen, H.; Yang, R. Exosomal miR-4645-5p from hypoxic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells facilitates diabetic wound healing by restoring keratinocyte autophagy. Burn. Trauma 2024, 12, tkad058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.-B.; Zhou, Z.-J.; Xiao, K.; Zhu, G.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhou, S.-L.; Chen, Q.; Yin, D.; Wang, Z.; et al. The miR-561-5p/CX3CL1 Signaling Axis Regulates Pulmonary Metastasis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Involving CX3CR1+ Natural Killer Cells Infiltration. Theranostics 2019, 9, 4779–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Chen, C.-L.; Chen, I.-H.; Tseng, H.-P.; Chiang, K.-C.; Lai, C.-Y.; Hsu, L.-W.; Goto, S.; Lin, C.-C.; Cheng, Y.-F. Overexpression of miR-4669 Enhances Tumor Aggressiveness and Generates an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Its Clinical Value as a Predictive Biomarker. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathipati, S.Y.; Tsai, M.-J.; Aimalla, N.; Moat, L.; Shukla, S.K.; Allaire, P.; Hebbring, S.; Beheshti, A.; Sharma, R.; Ho, S.-Y. An evolutionary learning-based method for identifying a circulating miRNA signature for breast cancer diagnosis prediction. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2024, 6, lqae022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Najafi, S.; Hussen, B.M.; Ganjo, A.R.; Taheri, M.; Samadian, M. DLX6-AS1: A Long Non-coding RNA With Oncogenic Features. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 746443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, S.; Fuchs, U.; Gisa, V.; Pena, T.; Krüger, D.M.; Hempel, N.; Burkhardt, S.; Salinas, G.; Schütz, A.-L.; Delalle, I.; et al. PRDM16-DT is a novel lncRNA that regulates astrocyte function in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 148, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Cumming, H.; Cerruti, L.; Cunningham, J.M.; Jane, S.M. Site-specific Acetylation of the Fetal Globin Activator NF-E4 Prevents Its Ubiquitination and Regulates Its Interaction with the Histone Deacetylase, HDAC1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41477–41486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Wu, W.; Chen, X.; Bao, H.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, X.; Chen, S. SNORD99 promotes endometrial cancer development by inhibiting GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis through 2'-O-methylation modification. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Song, X.; Wang, K.; Yu, M.; Ding, S.; Dong, X.; Xie, L.; Song, X. SNORD63 and SNORD96A as the non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wen, J.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.-P.; Zhang, B.-X.; Chu, L. Small Nucleolar RNAs: Insight Into Their Function in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Hu, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Zhong, M. Long non-coding RNA SNHG29 regulates cell senescence via p53/p21 signaling in spontaneous preterm birth. Placenta 2021, 103, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Chen, D.; Hu, Z.; Yu, T.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; et al. The LINC01138 drives malignancies via activating arginine methyltransferase 5 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ren, M.; Song, C.; Li, D.; Soomro, S.H.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, H. LINC00461, a long non-coding RNA, is important for the proliferation and migration of glioma cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 84123–84139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Ding, J.-M.; Zheng, X.-Z.; Chen, J.-G. Immunity-related long noncoding RNA WDFY3-AS2 inhibited cell proliferation and metastasis through Wnt/β-catenin signaling in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Oral Biol. 2023, 147, 105625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.; Bhowmick, K.; Park, A.; Huang, H.; Yang, X.; Mishra, L. Recent advances in targeting obesity, with a focus on TGF-β signaling and vagus nerve innervation. Bioelectron. Med. 2025, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iruzubieta, P.; Jimenez-Gonzalez, C.; Cabezas, J.; Crespo, J. From NAFLD to MASLD: transforming steatotic liver disease diagnosis and management. Metab. Target Organ Damage 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, E.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E.A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016, 65, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunny, N.E.; Parks, E.J.; Browning, J.D.; Burgess, S.C. Excessive Hepatic Mitochondrial TCA Cycle and Gluconeogenesis in Humans with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Lei, G.; Ma, X.; An, L.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Lin, L.; He, Q.; Xu, R.; et al. Serum Exosome–Derived microRNA-193a-5p and miR-381-3p Regulate Adenosine 5'-Monophosphate–Activated Protein Kinase/Transforming Growth Factor Beta/Smad2/3 Signaling Pathway and Promote Fibrogenesis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2024, 15, e00662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Discovery Cohort | Validation Cohort | ||||||

| Control (n=4) | MASLD (n=4) | P-value | Control (n=16) | MASLD (n=14) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | 61±4.83 | 53±5.94 | 0.08 | 53±12.97 | 46±8.36 | 0.08 | |

| Male/Female | 2/2 | 2/2 | - | 6/10 | 6/8 | - | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.22±1.53 | 27.8±4.25 | 0.29 | 30.61±8.38 | 30.26±7.81 | 0.90 | |

| Hba1c (%) | 5.26±0.37 | 5.65±0.07 | 0.27 | 5.35±0.57 | 6.58±1.56 | 0.01 | |

| LDL (Optimal range <100 mg/dL) * | - | 137.34±26.65 | - | - | 102.5±49.17 | - | |

| HDL (Optimal range 40-70 mg/dL) * | - | 50.34±18.82 | - | - | 48.93±17.94 | - | |

| Triglyceride (Optimal range <150 mg/dL)* | - | 124±85.08 | - | - | 138.64±75.11 | - | |

| FibroScan** | - | Patient 1 – F0; Patient 2 – F2-F3; Patient 3 – F0-F1; Patient 4 – F0-F1 | - | - | Patient 5 – F2; Patient 6 – F4; Patient 7 – F0-F1; Patient 8 –F0-F1; Patient 9 – F3; Patient 10 – F2; Patient 11 – F2; Patient 12 – F0-F1; Patient 13 – F0; Patient 14 – F0; Patient 15 – F0-F1; Patient 16 – F2; Patient 17 – F2; Patient 18 – F0 | - | |

| Steatosis Stage*** | - | Patient 1 – S3; Patient 2 – S3; Patient 3 – S1; Patient 4 – S3 | - | - | Patient 5 – S1-S2; Patient 6 – S1-S2; Patient 7 – S3; Patient 8 – S0; Patient 9 – S0; Patient 10 – S3; Patient 11 – S2; Patient 12 – S2; Patient 13 – S2-S3; Patient 14 – S0; Patient 15 – S0; Patient 16 – S3; Patient 17 – S3; Patient 18 – S0 | - | |

| miRNA | Fold Change | P-Value | Biological Functions |

| hsa-miR-218-5p | -5.82 | 0.0003 | Regulates placental development, airway inflammation, and hepatic lipogenesis; targets TGFβ2, SMAD2, TLR4, Elovl5. [41] |

| hsa-miR-370-3p | -3.88 | 0.0005 | Regulates VSMC phenotype, glioblastoma suppression, and sinus node dysfunction in heart failure. [42] |

| hsa-miR-4731-5p | -3.57 | 0.0125 | Tumor suppressor in glioblastoma, melanoma, and NSCLC; impacts viability, EMT, and apoptosis. [43] |

| hsa-miR-1343-5p | -3.48 | 0.0020 | Reduces TGF-β signaling and fibrosis via exosomal delivery; therapeutic potential in lung disease. [28] |

| hsa-miR-224-5p | -2.88 | 0.0001 | Promotes EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma, regulates autophagy in breast cancer, and modulates cardiovascular inflammation. [44] |

| hsa-miR-193a-5p | -2.80 | 0.0031 | Tumor suppressor; inhibits proliferation and metastasis in ovarian and prostate cancers. [45] |

| hsa-miR-1299 | -2.78 | 0.0055 | Tumor suppressor; inhibits NEK2 in prostate cancer, also regulates RHOT1 and PDL1 in other cancers. [46] |

| hsa-miR-4707-3p | -2.69 | 0.0021 | Modulates cell fate in human neocortex development. [47] |

| hsa-miR-133a-3p | -2.67 | 0.0247 | Tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer; inhibits angiogenesis. [48] |

| hsa-miR-365a-3p | -2.59 | 0.0236 | Promotes lung cancer via PI3K/AKT; affects osteogenesis by targeting RUNX2. [49] |

| hsa-miR-4664-5p | -2.59 | 0.0223 | Detected in breast cancer; potential cancer biomarker. [50] |

| hsa-miR-539-5p | -2.51 | 0.0039 | Inhibits pancreatic cancer proliferation; regulates Tregs in leukemia. [51] |

| hsa-miR-369-5p | -2.37 | 0.0175 | Inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting HOXA13. [52] |

| hsa-miR-150-3p | -2.12 | 0.0275 | Antitumor in lung cancer; enhances neuronal proliferation. [53] |

| hsa-miR-1185-1-3p | -2.05 | 0.0267 | Biomarker for weight loss response; associated with lung cancer. [54] |

| hsa-miR-3940-3p | -2.01 | 0.0026 | Promotes granulosa cell proliferation; linked to insulin resistance in pregnancy. [55] |

| hsa-miR-369-3p | -1.90 | 0.0373 | Anti-inflammatory; inhibits preadipocyte proliferation and differentiation. [56] |

| hsa-miR-452-5p | -1.89 | 0.0297 | Regulates fibrosis and promotes cancer progression. [57] |

| hsa-miR-323b-3p | -1.86 | 0.0363 | Upregulated in Huntington’s disease; involved in neurodegeneration. [58] |

| hsa-miR-433-3p | -1.82 | 0.0236 | Suppresses glioma growth; enhances chemotherapy sensitivity. [59] |

| hsa-miR-379-5p | -1.81 | 0.0209 | Plays a role in regulating cellular processes, particularly in cancer development and progression. [60] |

| hsa-miR-409-5p | -1.71 | 0.0480 | Promotes tumor growth, EMT, and bone metastasis in prostate cancer. [61] |

| hsa-miR-487b-3p | -1.69 | 0.0112 | Negative regulator of skeletal myogenesis; suppresses C2C12 myoblast proliferation. [62] |

| hsa-miR-154-5p | -1.65 | 0.0451 | Triggers cardiac oxidative stress and inflammation; tumor suppressor in glioblastoma. [63] |

| hsa-miR-3195 | 1.60 | 0.0125 | Suppresses osteosarcoma progression by targeting SOX4; linked to prostate cancer. [64] |

| hsa-miR-6758-5p | 1.65 | 0.0165 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| hsa-miR-4479 | 1.7 | 0.0198 | Potential biomarker in cancer; roles in immunosuppression and metastasis. [65] |

| hsa-miR-196a-5p | 1.7 | 0.0437 | Oncogene; promotes invasion, metastasis, and proliferation in many cancers. [66] |

| hsa-miR-4762-5p | 2.0 | 0.0034 | Detected in breast cancer tissues; role in tumorigenesis is under study. [67] |

| hsa-miR-129-5p | 2.35 | 0.0147 | Tumor suppressor; inhibits proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma. [68] |

| hsa-miR-206 | 2.56 | 0.0353 | Involved in cancers, neurodegenerative, and cardiovascular diseases; tumor suppressor. [69] |

| hsa-miR-4645-5p | 3.02 | 0.0309 | Facilitates diabetic wound healing by restoring keratinocyte autophagy. [70] |

| hsa-miR-561-3p | 3.80 | 0.0122 | Modulates CX3CL1 signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma; suppresses metastasis. [71] |

| hsa-miR-4669 | 3.85 | <0.0001 | Enhances tumor aggressiveness creates immunosuppressive environment in liver cancer. [72] |

| hsa-miR-5698 | 5.29 | <0.0001 | Identified as breast cancer biomarker; functions not well characterized. [73] |

| Other ncRNA | Fold Change | P-Value | Biological Functions |

| Homo_sapiens_tRNA-Leu-AAG-1 | -8.03 | 0.043 | Encodes a tRNA specific for leucine with the AAG anticodon, essential for protein synthesis. |

| ENSG00000282021 | -6.29 | 0.004 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| ENSG00000285756 | -5.95 | 0.006 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| DLX6-AS1 | -5.76 | 0.009 | Long non-coding RNA implicated in promoting tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in various cancers. [74] |

| FMNL1-DT | -5.44 | 0.034 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| APOBEC3B-AS1 | -5.42 | 0.003 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| RN7SL426P | -5.23 | 0.012 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| ENSG00000254639 | -5.23 | 0.020 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| RSF1-IT1 | -5.20 | 0.020 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| ENSG00000273064 | -5.07 | 0.036 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| PRDM16-DT | -5.03 | 0.031 | Long non-coding RNA involved in regulating astrocyte function and implicated in colorectal cancer metastasis and drug resistance. [75] |

| RNU6-70P | -5.02 | 0.025 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| Homo_sapiens_tRNA-Gly-GCC-5 | -4.41 | 0.005 | Encodes a tRNA specific for glycine with the GCC anticodon, essential for protein synthesis. |

| U8 | -3.75 | 0.019 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| NFE4 | -3.11 | 0.014 | Transcription factor involved in regulating fetal γ-globin gene expression. Acetylation of NFE4 prevents its ubiquitination and modulates its interaction with histone deacetylase HDAC1, influencing gene activation. [76] |

| Homo_sapiens_tRNA-Met-CAT-6 | -1.95 | 0.037 | Encodes transfer RNA for methionine with anticodon CAT, essential for initiating protein synthesis. |

| Homo_sapiens_tRNA-Asp-GTC-2 | -1.86 | 0.002 | Encodes transfer RNA for aspartic acid with anticodon GTC, facilitating incorporation of aspartic acid during protein synthesis. |

| SNORD99 | 1.69 | 0.007 | Small nucleolar RNA involved in 2'-O-methylation of ribosomal RNA. Overexpression promotes endometrial cancer development by inhibiting GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis. [77] |

| SNORD96A | 1.71 | 0.005 | Small nucleolar RNA implicated in ribosomal RNA modification. Elevated levels in plasma serve as a non-invasive diagnostic biomarker for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). [78] |

| SNORD48 | 1.71 | 0.030 | Small nucleolar RNA involved in post-transcriptional modification of other small nuclear RNAs. Associated with prostate and hematologic cancers. [79] |

| ENSG00000280434 | 1.97 | 0.004 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| SNHG29 | 2.40 | 0.000 | Long non-coding RNA that regulates cell senescence via p53/p21 signaling and promotes glioblastoma progression through the miR-223-3p/CTNND1 axis. [80] |

| LINC01138 | 2.74 | 0.012 | Long intergenic non-coding RNA that acts as an oncogenic driver by interacting with PRMT5, enhancing its stability, and promoting tumorigenicity in hepatocellular carcinoma. [81] |

| ENSG00000253374 | 3.86 | 0.033 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| RN7SL33P | 4.58 | 0.021 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| LINC00461 | 4.96 | 0.000 | Long non-coding RNA important for glioma progression, affecting cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. [82] |

| ENSG00000286834 | 5.09 | 0.012 | Specific function remains unknown. |

| WDFY3-AS2 | 5.28 | 0.022 | Long non-coding RNA that acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting cell proliferation and metastasis through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. [83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).