Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Extraction of EEAH

2.2. Studies of Insulin Release In Vitro

2.3. β-Cell Proliferation In Vitro

2.4. In Vitro Starch Digestion

2.5. In Vitro Glucose Diffusion

2.6. Animals

- Group 1: Lean control (saline)

- Group 2: High fat fed diet control (saline)

- Group 3: High fat diet + EEAH (250 mg/5 mL/kg)

- Group 4: High fat diet + EEAH (500 mg/5 mL/kg)

- Group 5: High fat diet + Glibenclamide (5 mg/5 mL/kg)

2.7. Acute and Chronic Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

2.8. Chronic Study of Blood Glucose, Body Weight, Food and Fluid Intake

2.9. Lipid Profile Test

2.10. Gut Motility In Vivo

2.11. Phytochemical Screening

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Insulin Release with EEAH

3.2. Insulin Release with EEAH, Known Modulators and Absence of Extracellular Ca2+

3.3. Proliferation In Vitro with EEAH

3.4. Starch Digestion In Vitro with EEAH

3.5. Glucose Diffusion In Vitro with EEAH

3.6. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test with EEAH

3.7. Chronic Study of Fasting Blood Glucose, Body Weight, Food and Fluid Intake with EEAH

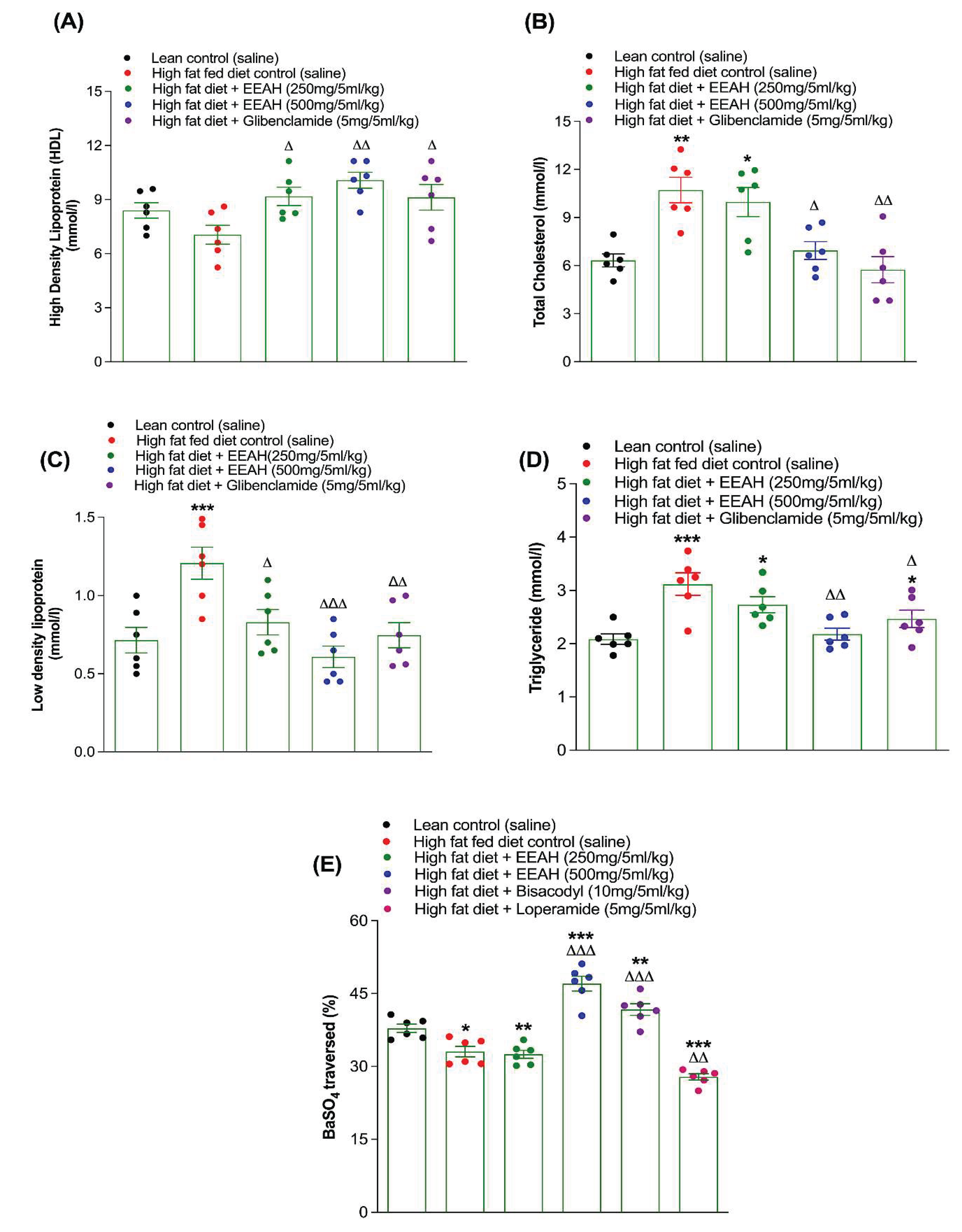

3.8. Lipid Profiling with EEAH

3.9. Gut Motility with EEAH

3.10. Phytochemical Screening with EEAH

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banday, M. Z.; Sameer, A. S.; Nissar, S. Pathophysiology of Diabetes: An Overview. Avicenna J. Med. 2020, 10, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, P.; Samia, J. F.; Khan, J. T.; Rafi, M. R.; Rahman, M. S.; Rahman, A. B.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A.; Seidel, V. Protective Effects of Medicinal Plant-Based Foods Against Diabetes: A Review on Pharmacology, Phytochemistry, and Molecular Mechanisms. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M. J.; Al-Mamun, M.; Islam, M. R. Diabetes Mellitus, the Fastest Growing Global Public Health Concern: Early Detection Should be Focused. Health Sci Rep. 2024, 7, e2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, J. M. A.; Nipa, N.; Toma, F. T.; Talukder, A.; Ansari, P. Acute Anti-Hyperglycaemic Activity of Five Traditional Medicinal Plants in High Fat Diet Induced Obese Rats. Front. Biosci. (Schol. Ed) 2023, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. S.; Hossain, K. S.; Das, S.; Kundu, S.; Adegoke, E. O.; Rahman, M. A.; Hannan, M. A.; Uddin, M. J.; Pang, M.-G. Role of Insulin in Health and Disease: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Gilbert, E. R.; Liu, D. Regulation of Insulin Synthesis and Secretion and Pancreatic Beta-Cell Dysfunction in Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2013, 9, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakilian, M.; Tahamtani, Y.; Ghaedi, K. A Review on Insulin Trafficking and Exocytosis. Gene 2019, 706, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M. C.; Shulman, G. I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2133–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Khan, F.; Hirsch, I. B. New Advances in Type 1 Diabetes. BMJ 2024, 384, e075681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucier, J.; Mathias, P. M. Type 1 Diabetes. In StatPearls [Internet] 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507713/.

- Galicia-Garcia, U.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Jebari, S.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Siddiqi, H.; Uribe, K. B.; Ostolaza, H.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Flatt, P. R.; Harriott, P.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Insulin Secretory and Antidiabetic Actions of Heritiera fomes Bark Together with Isolation of Active Phytomolecules. PloS one 2022, 17, e0264632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmaki, P.; Damaskos, C.; Garmpis, N.; Garmpi, A.; Savvanis, S.; Diamantis, E. Complications of the Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2020, 16, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olokoba, A. B.; Obateru, O. A.; Olokoba, L. B. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Current Trends. Oman Med. J. 2012, 27, 269–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, B. S. Q.; Vadakekut, E. S.; Mahdy, H. Gestational Diabetes. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545196/.

- Polonsky, W. H.; Henry, R. R. Poor Medication Adherence in Type 2 Diabetes: Recognizing the Scope of the Problem and its Key Contributors. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herges, J. R.; Neumiller, J. J.; McCoy, R. G. Easing the Financial Burden of Diabetes Management: A Guide for Patients and Primary Care Clinicians. Clin. Diabetes 2021, 39, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, B. O.; Adeleke Ojo, O.; Adeyonu, O.; Imiere, O.; Emmanuel Oyinloye, B.; Ogunmodede, O. Ameliorative Activity of Ethanolic Extract of Artocarpus heterophyllus Stem Bark on Alloxan-induced Diabetic Rats. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 8, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J. R.; Julius, A.; Chinnapan, V. Health Benefits and Future Prospects of Artocarpus heterophyllus. Res. J. Pharm. Tech. 2023, 16, 4443–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, R. A. S. N.; Maduwanthi, S. D. T.; Marapana, R. A. U. J. Nutritional and Health Benefits of Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.): A Review. Int. J. Food Sci. 2019, 2019, 4327183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, H. S.; El-Beshbishy, H. A.; Moussa, Z.; Taha, K. F.; Singab, A. N. Antioxidant Activity of Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. (Jack Fruit) Leaf Extracts: Remarkable Attenuations of Hyperglycemia and Hyperlipidemia in Streptozotocin-Diabetic Rats. ScientificWorldJournal 2011, 11, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O.; Kumar, R.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, R. Artocarpus heterophyllus (Jackfruit): An Overview. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2009, 3, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, P.; Hannan, J. M. A.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Anti-Diabetic Properties of the Ethanolic Extract of Unripe Artocarpus heterophyllus Fruit Regulates Glucose Homeostasis in High-Fat-Fed Diet Induced Obese Mice. In Endocrine Abstracts 2023, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chackrewarthy, S.; Thabrew, M. I.; Weerasuriya, M. K.; Jayasekera, S. Evaluation of the Hypoglycemic and Hypolipidemic Effects of an Ethylacetate Fraction of Artocarpus heterophyllus (Jak) Leaves in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2010, 6, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, P.; Khan, J. T.; Chowdhury, S.; Reberio, A. D.; Kumar, S.; Seidel, V.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A.; Flatt, P. R. Plant-Based Diets and Phytochemicals in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus and Prevention of Its Complications: A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, P.; Azam, S.; Seidel, V.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. In Vitro and In Vivo Antihyperglycemic Activity of the Ethanol Extract of Heritiera fomes Bark and Characterization of Pharmacologically Active Phytomolecules. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, rgac010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Harte, F. P.; Ng, M. T.; Lynch, A. M.; Conlon, J. M.; Flatt, P. R. Novel Dual Agonist Peptide Analogues Derived from Dogfish Glucagon Show Promising In Vitro Insulin Releasing Actions and Antihyperglycaemic Activity in Mice. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016, 431, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Flatt, P. R.; Harriott, P.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Evaluation of the Antidiabetic and Insulin Releasing Effects of A. squamosa, Including Isolation and Characterization of Active Phytochemicals. Plants 2020, 9, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Khan, J. T.; Soultana, M.; Hunter, L.; Chowdhury, S.; Priyanka, S. K.; Paul, S. Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Insulin Secretory Actions of Polyphenols of Momordica charantia Regulate Glucose Homeostasis in Alloxan-Induced Type 2 Diabetic Rats. RPS Pharm. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 3, rqae005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Hannan, J. M. A.; Seidel, V.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Polyphenol-Rich Leaf of Annona squamosa Stimulates Insulin Release from BRIN-BD11 Cells and Isolated Mouse Islets, Reduces (CH2O)n Digestion and Absorption, and Improves Glucose Tolerance and GLP-1 (7-36) Levels in High-Fat-Fed Rats. Metabolites 2022, 12, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Tanday, N.; Lafferty, R. A.; Flatt, P. R.; Irwin, N. Novel Enzyme-Resistant Pancreatic Polypeptide Analogs Evoke Pancreatic Beta-Cell Rest, Enhance Islet Cell Turnover, and Inhibit Food Intake in Mice. Biofactors 2024, 50, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Islam, S. S.; Akther, S.; Khan, J. T.; Shihab, J. A.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. Insulin Secretory Actions of Ethanolic Extract of Acacia arabica Bark in High Fat-Fed Diet-Induced Obese Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Biosci. Rep. 2023, 43, BSR20230329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, A. M.; Flatt, P. R.; Duffy, G.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. The Effects of Traditional Antidiabetic Plants on In Vitro Glucose Diffusion. Nutr. Res. 2003, 23, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Hannan, J. M. A.; Choudhury, S. T.; Islam, S. S.; Talukder, A.; Seidel, V.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Antidiabetic Actions of Ethanol Extract of Camellia sinensis Leaf Ameliorates Insulin Secretion, Inhibits the DPP-IV Enzyme, Improves Glucose Tolerance, and Increases Active GLP-1 Levels in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Rats. Medicines 2022, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Soldado, I.; Guinovart, J. J.; Duran, J. Increasing Hepatic Glycogen Moderates the Diabetic Phenotype in Insulin-Deficient Akita Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, J. T.; Richi, A. E.; Riju, S. A.; Jalal, T.; Orchi, R. J.; Singh, S.; Bhagat, P.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A.; Ansari, P. Evaluation of Antidiabetic Potential of Mangifera indica Leaf in Streptozotocin-Induced Type 2 Diabetic Rats: Focus on Glycemic Control and Cholesterol Regulation. Endocrines 2024, 5, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, J. M. A.; Ali, L.; Rokeya, B.; Khaleque, J.; Akhter, M.; Flatt, P. R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. Soluble Dietary Fibre Fraction of Trigonella Foenum-graecum (Fenugreek) Seed Improves Glucose Homeostasis in Animal Models of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes by Delaying Carbohydrate Digestion and Absorption, and Enhancing Insulin Action. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, J. M. A.; Ansari, P.; Haque, A.; Sanju, A.; Huzaifa, A.; Rahman, A.; Ghosh, A.; Azam, S. Nigella sativa Stimulates Insulin Secretion from Isolated Rat Islets and Inhibits the Digestion and Absorption of (CH2O)n in the Gut. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20190723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Badhan, S.; Azam, S.; Sultana, N.; Anwar, S.; Mohamed Abdurahman, M. S.; Hannan, J. M. A. Evaluation of Antinociceptive and Anti-inflammatory Properties of Methanolic Crude Extract of Lophopetalum javanicum (Bark). J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 27, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credo, D.; Machumi, F.; Masimba, P. J. Phytochemical Screening and Evaluation of Ant-Diabetic Potential of Selected Medicinal Plants used Traditionally for Diabetes Management in Tanzania. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Chem. 2018, 8, 405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Kooti, W.; Farokhipour, M.; Asadzadeh, Z.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Asadi-Samani, M. The Role of Medicinal Plants in the Treatment of Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 1832–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Harvat, T.; Kinzer, K.; Zhang, L.; Feng, F.; Qi, M.; Oberholzer, J. Diazoxide, a K(ATP) Channel Opener, Prevents Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rodent Pancreatic Islets. Cell Transplant. 2015, 24, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, G. W. The Adenylate Cyclase-Cyclic AMP System in Islets of Langerhans and its Role in the Control of Insulin Release. Diabetologia 1979, 16, 287–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Kang, S. G.; Huang, K.; Tong, T. Dietary Bioactive Ingredients Modulating the cAMP Signaling in Diabetes Treatment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Aguilar, A.; Guillén, C. Targeting Pancreatic Beta Cell Death in Type 2 Diabetes by Polyphenols. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1052317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A. F.; Hussain, M. A.; García-Ocaña, A.; Vasavada, R. C.; Bhushan, A.; Bernal-Mizrachi, E.; Kulkarni, R. N. Human β-cell Proliferation and Intracellular Signaling: Part 3. Diabetes 2015, 64, 1872–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W. J.; Peng, Y. C.; Yang, K. M. Cellular Signaling Pathways Regulating β-cell Proliferation as a Promising Therapeutic Target in the Treatment of Diabetes. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D. T. M.; Palermo, K. R.; Motta, B. P.; Kaga, A. K.; Lima, T. F. O.; Brunetti, I. L.; Baviera, A. M. Rutin Inhibits the in Vitro Formation of Advanced Glycation Products and Protein Oxidation More Efficiently than Quercetin. Rev. Cienc. Farm. Basica Apl. 2021, 42, e718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falla, N. M.; Demasi, S.; Caser, M.; Scariot, V. Phytochemical Profile and Antioxidant Properties of Italian Green Tea, a New High Quality Niche Product. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Flatt, P. R.; Harriott, P.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. Anti-hyperglycaemic and Insulin-Releasing Effects of Camellia sinensis Leaves and Isolation and Characterization of Active Compounds. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 126, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahama, U.; Hirota, S. Interactions of Flavonoids with α-Amylase and Starch Slowing down Its Digestion. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, A. S. D.; Kalansuriya, P.; Attanayake, A. P. Herbal Medicines Targeting the Improved β-Cell Functions and β-Cell Regeneration for the Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 2021, 2920530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winzell, M. S.; Ahrén, B. The High-Fat Diet-Fed Mouse: A Model for Studying Mechanisms and Treatment of Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2004, 53 (Suppl 3), S215–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwitiyanti, D.; Rachmania, R. A.; Efendi, K.; Septiani, R.; Jihadudin, P. In Vivo Activities and In Silico Study of Jackfruit Seeds (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.) on the Reduction of Blood Sugar Levels of Gestational Diabetes Rate Induced by Streptozotocin. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 3819–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, R. A.; Nicolas, S.; Shivkumar, A. Sulfonylureas. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513225/.

- Hussain, A.; Cho, J. S.; Kim, J. S.; Lee, Y. I. Protective Effects of Polyphenol Enriched Complex Plants Extract on Metabolic Dysfunctions Associated with Obesity and Related Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases in High Fat Diet-Induced C57BL/6 Mice. Molecules 2021, 26, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrânceanu, M.; Hegheş, S. C.; Cozma-Petruţ, A.; Banc, R.; Stroia, C. M.; Raischi, V.; Miere, D.; Popa, D. S.; Filip, L. Plant-Derived Nutraceuticals Involved in Body Weight Control by Modulating Gene Expression. Plants 2023, 12, 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccellino, M.; D'Angelo, S. Anti-Obesity Effects of Polyphenol Intake: Current Status and Future Possibilities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, K.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, R.; Saxena, R.; Kumar, A.; Badoni, H.; Goyal, B.; Mirza, A. A. Efficacy of Jackfruit Components in Prevention and Control of Human Disease: A Scoping Review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, I.; Shahat, A. A.; Noman, O. M.; Milenkovic, D.; Amrani, S.; Harnafi, H. Effects of Cynara scolymus L. Bract Extract on Lipid Metabolism Disorders Through Modulation of HMG-CoA Reductase, Apo A-1, PCSK-9, p-AMPK, SREBP-2, and CYP2E1 Expression. Metabolites 2024, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R. A.; Singh, B. K.; Yen, P. M. Direct Effects of Thyroid Hormones on Hepatic Lipid Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, P.; Hannan, J. M. A.; Seidel, V.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. Polyphenol-Rich Leaf of Annona squamosa Stimulates Insulin Release from BRIN-BD11 Cells and Isolated Mouse Islets, Reduces (CH2O)n Digestion and Absorption, and Improves Glucose Tolerance and GLP-1 (7-36) Levels in High-Fat-Fed Rats. Metabolites 2022, 12, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiela, P. R.; Ghishan, F. K. Physiology of Intestinal Absorption and Secretion. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 145–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Kim, J. K.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Chen, X. Tannic Acid Stimulates Glucose Transport and Inhibits Adipocyte Differentiation in 3T3-L1 Cells. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 165–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahakyan, G.; Vejux, A.; Sahakyan, N. The Role of Oxidative Stress-Mediated Inflammation in the Development of T2DM-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy: Possible Preventive Action of Tannins and Other Oligomeric Polyphenols. Molecules 2022, 27, 9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elekofehinti, O. O.; Ejelonu, O. C.; Kamdem, J. P.; Akinlosotu, O. B.; Adanlawo, I. G. Saponins as Adipokines Modulator: A Possible Therapeutic Intervention for Type 2 Diabetes. World J. Diabetes 2017, 8, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M. Á.; Ramos, S. Dietary Flavonoids and Insulin Signaling in Diabetes and Obesity. Cells 2021, 10, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bansal, A.; Singh, V.; Chopra, T.; Poddar, J. Flavonoids, Alkaloids and Terpenoids: A New Hope for the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2022, 21, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group Test | Observation |

|---|---|

| Alkaloids | + |

| Tannins | + |

| Flavonoids | + |

| Saponins | + |

| Steroids | + |

| Terpenoids | + |

| Glycoside | ‒ |

| Reducing Sugar | ‒ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).