1. Introduction

Droplet spreading is a fascinating phenomenon [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

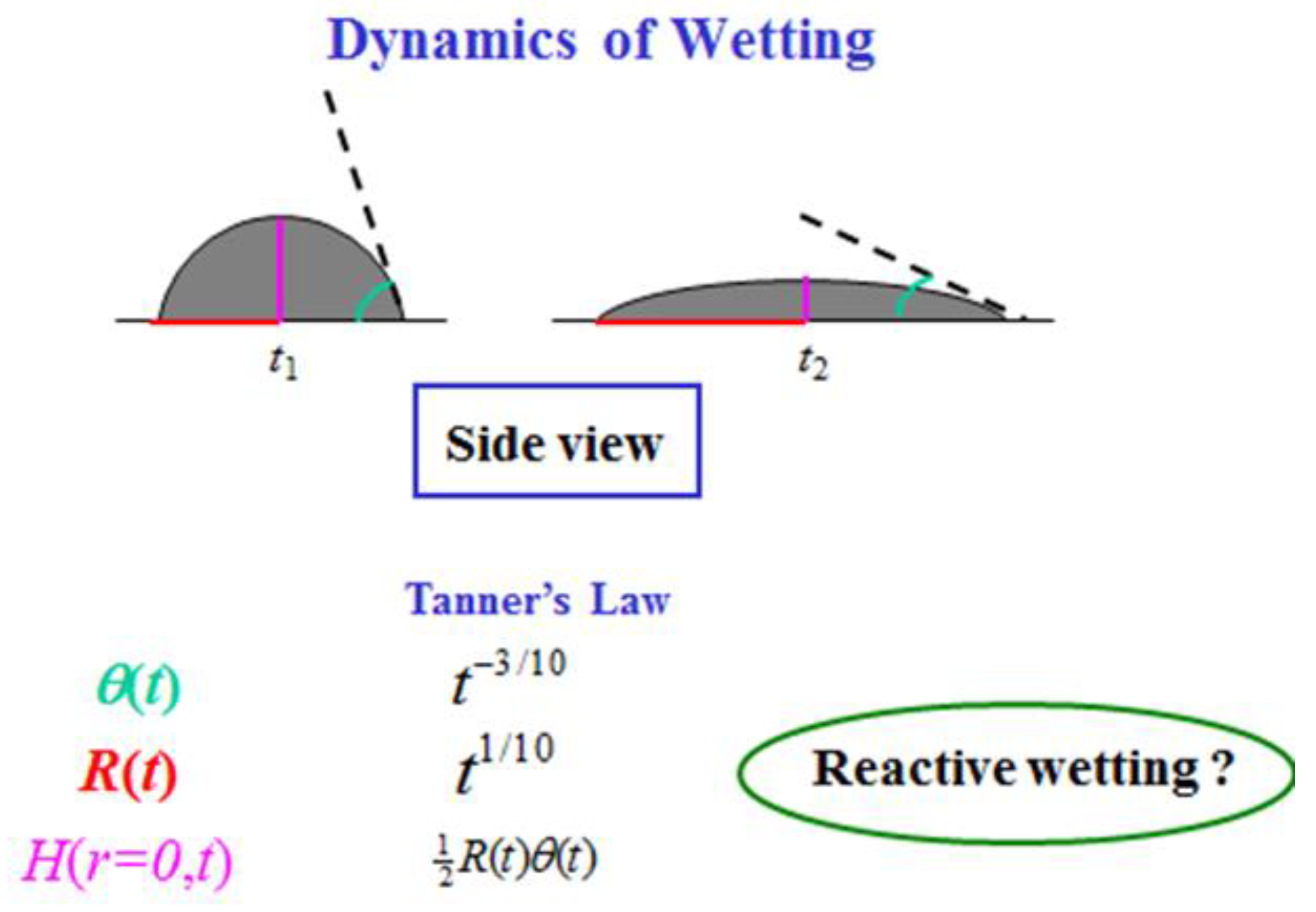

8]. The dynamics of droplet spreading is traditionally described by the change in time of the droplet radius

R(t) and its contact angle

θ(t) [

9,

10,

11,

12] (See

Figure 1). According to the well-known Tanner's Law [

9],

R(t) ~

t1/10 and

θ(t) ~

t-3/10 for a spherical cap shape droplet. When gravity is non-negligible, Lopez et al. [

10] showed that the radius grows slightly faster, as

t1/8. Nevertheless, these dynamics laws deal with a

side-view projection of the spreading droplet in a

classical wetting process. When other mechanisms are involved, e.g. dissolution, compound formation, chemical reaction and more, the wetting is

reactive [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. No theoretical prediction for the dynamic radius and contact angle are known. In turn, based on many empirical results (see, e.g. [

22]), it is commonly believed that in these cases the spreading is much faster, behaving like

R(t) ~ t for the radius. Such reactive wetting systems have many applications in industry and material science.

In this review, we describe the dynamics of droplet spreading in reactive wetting interfaces as obtained in a series of papers by our group [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Several aspects make our reactive wetting system unique. Regarding the experimental system, A) It is metal on

metal-on-glass; B) The spreading droplet material is

mercury [

36]. C) The experiment is performed at

room temperature. D) We follow the

top-view of the entire perimeter of the advancing droplet.

In this review, we describe the dynamics of droplet spreading in reactive wetting interfaces as obtained in a series of papers by our group [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Several aspects make our reactive wetting system unique. Regarding the experimental system, A) It is metal on

metal-on-glass; B) The spreading droplet material is

mercury [

36]. C) The experiment is performed at

room temperature. D) We follow the

top-view of the entire perimeter of the advancing droplet.

In terms of data analysis, our study exploits statistical physics tools to identify the driving mechanisms in the system. The statistical physics point of view enriches the insights into the droplet spreading process. The use of these tools has the advantage of universal applicability of the results to other systems, materials, and experimental conditions such as high temperatures.

The paper consists of the following chapters:

The Experimental System and Methodology

The Spreading Process - Bulk Spreading and Kinetic Roughening

Scaling Exponents - Roughness and Growth exponents, The Persistence Exponent

The Big Picture

Universality – High Temperatures

Kinetic Roughening, the QKPZ Equation and the Ising model

Effect of Temperature on Kinetic Roughening Exponents

Summary

Acknowledgements

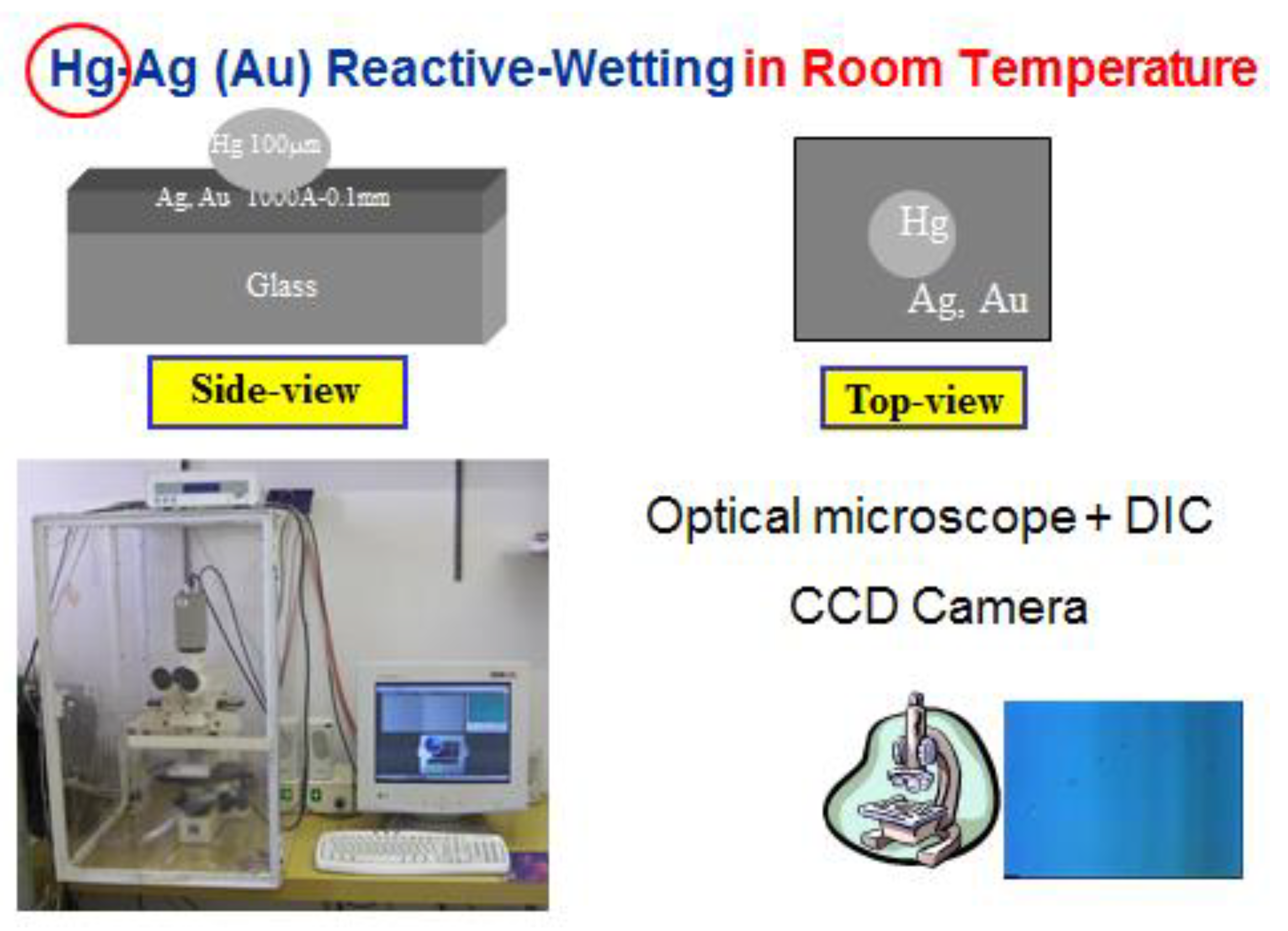

2. The Experimental System and Methodology

The experimental system is described in detail in [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In short, silver (or gold) thin films of various thicknesses (2000-6000

Å) were evaporated, sputtered (or polished) on top of a glass substrate, forming a metal-on-glass substrate. Mercury droplets (100-150μm diameter) were deposited on this substrate at room temperature (

Figure 2). The spreading process was monitored top view using an optical microscope equipped with DIC (Differential Interference Contrast) lenses and a CCD camera. The top-view images have been translated into side-view profiles [

26], based on the various colors obtained using reflection-DIC light microscopy. The idea is that the object reflects light from different points of its surface with different colors that are indicative of its surface slope at each point of the mercury droplet. The measurements were taken in a diametric cross section of the droplet, parallel to the beam-splitting direction.

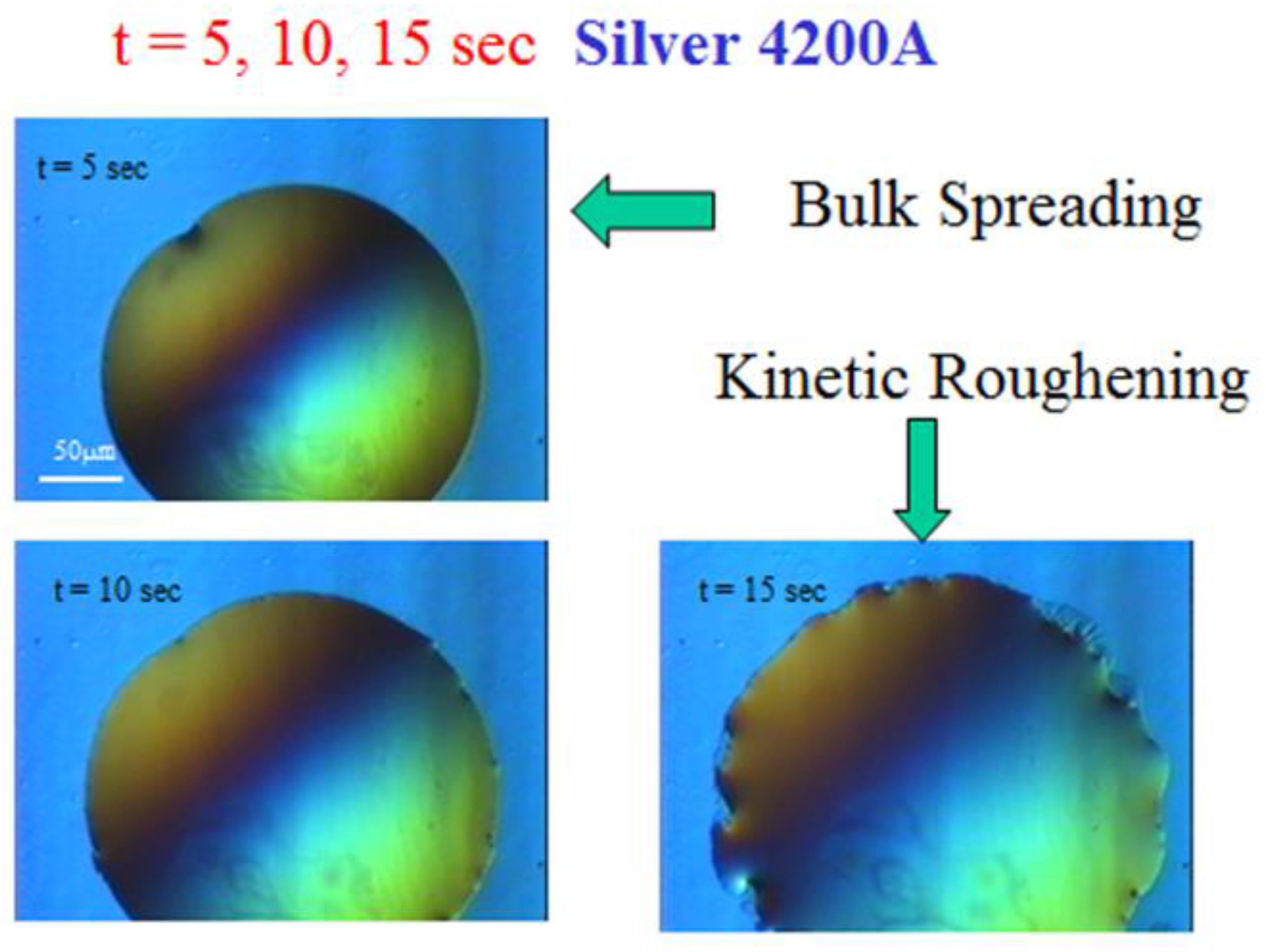

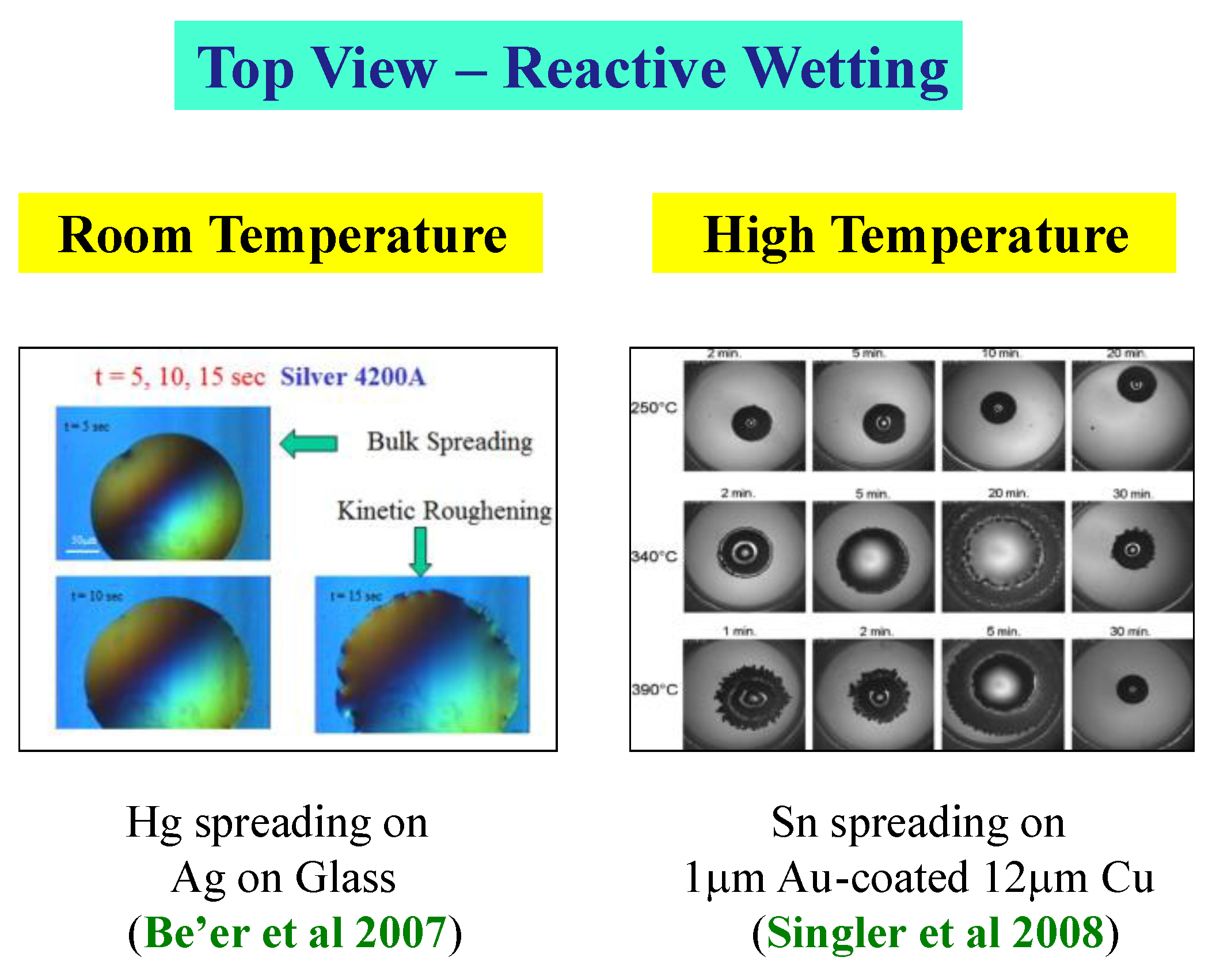

Some typical snapshots are shown in

Figure 3 for mercury spreading on top of a silver film (4200A) on glass, taken at times t = 5, 10, and 15 seconds after the droplet deposition on the film. These snapshots demonstrate that after several seconds the droplet perimeter changes from a seemingly smooth curve into a roughened pattern. This reflects the two main regimes in the droplet spreading process, "bulk spreading" and "kinetic roughening" as will be described below.

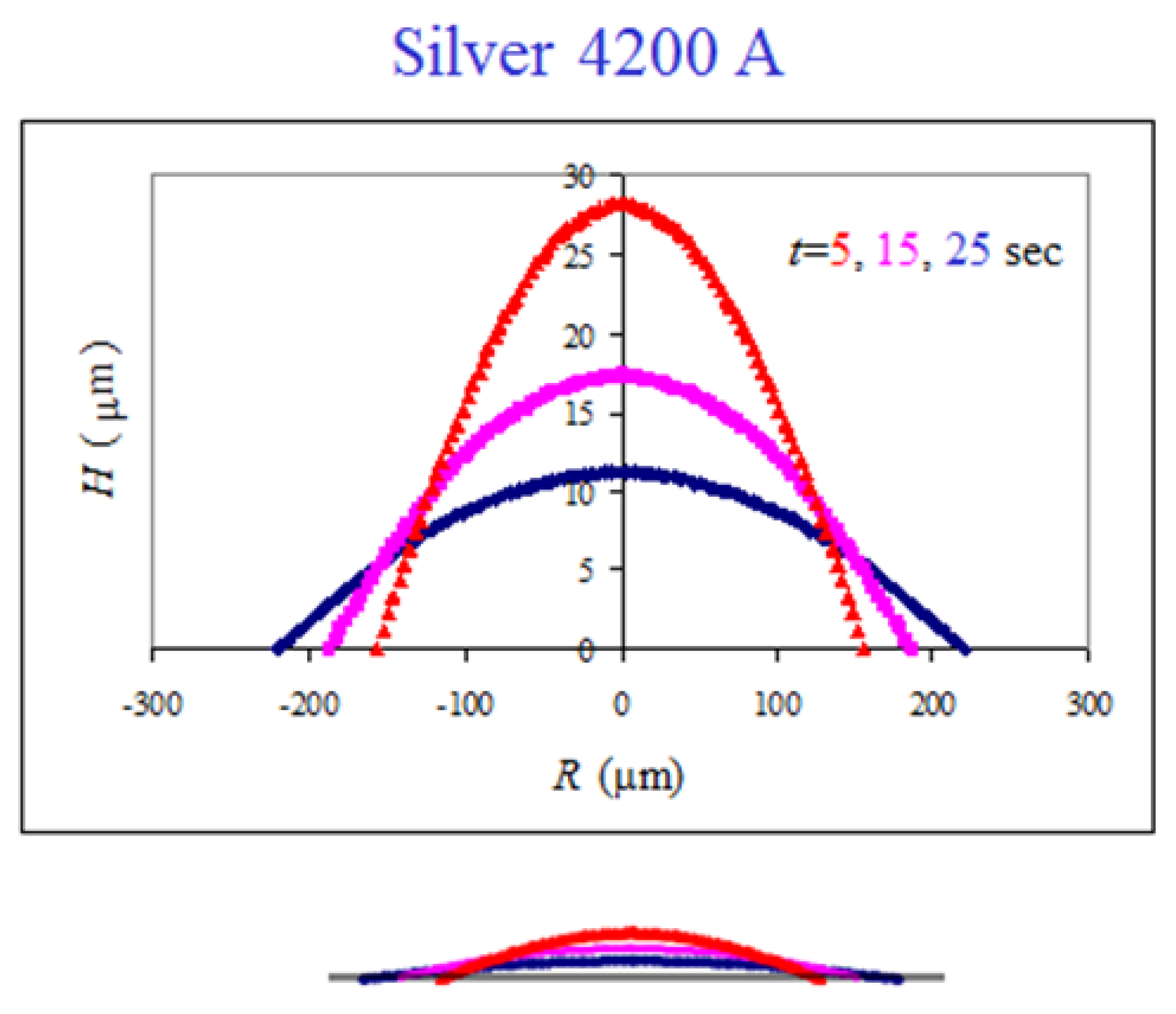

The top-view images are used to reconstruct the

side-view profiles of the spreading droplet using the technique described in detail in [

26]. This is shown in

Figure 4 for the same system, where the vertical scale is stretched in the main graph in order to demonstrate the spherical cap shape of the advancing droplet. The bottom sketch is the real scale. Such reconstructed profiles are used to study the spreading kinetics.

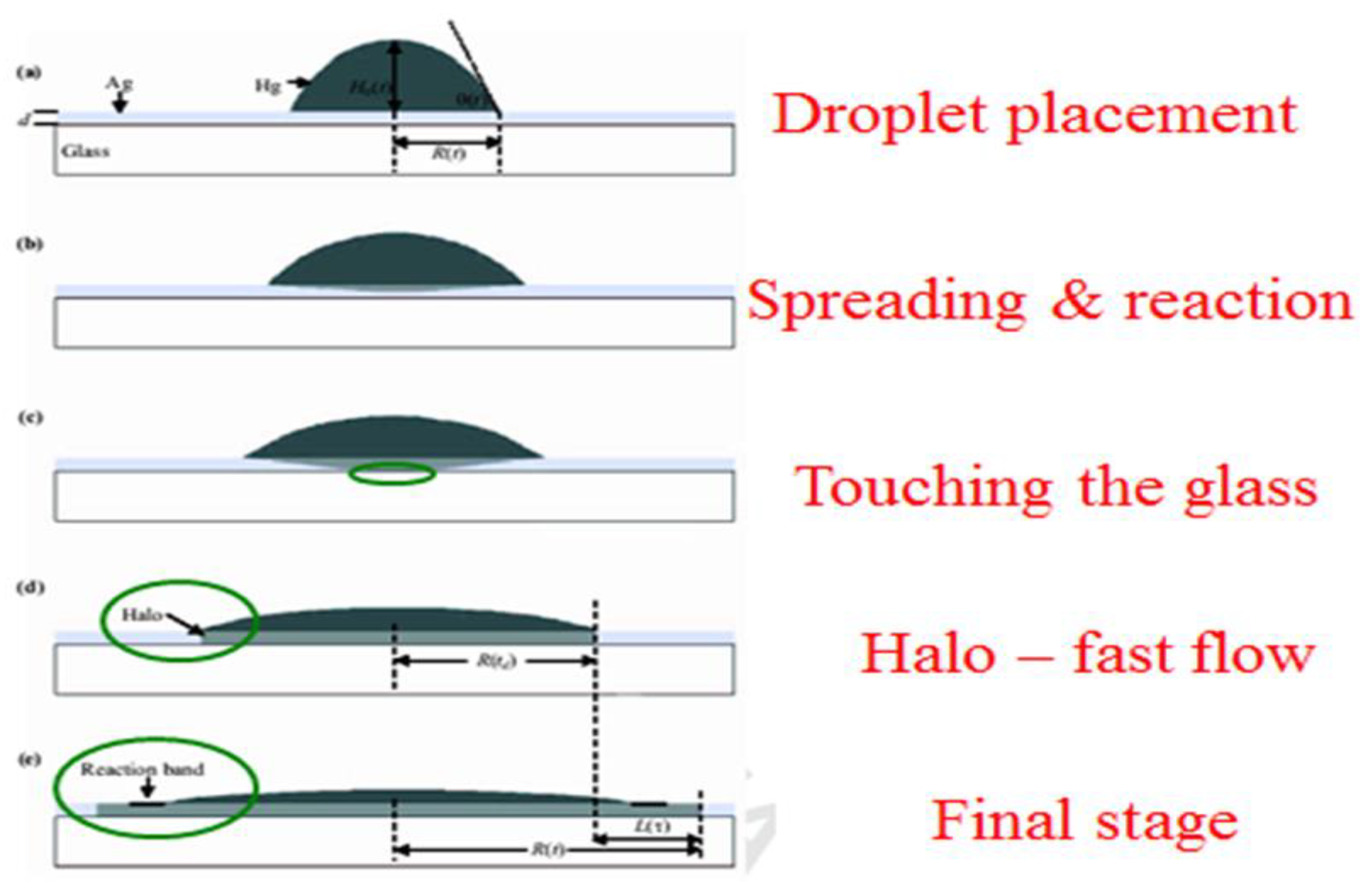

3. The Spreading Process

Using the reconstructed side-view shape profiles one can follow the details of the spreading process of the reactive metal droplet on the metal-on-glass [

30,

31]. This was found to consist of several consecutive

sub-steps (

Figure 5) in the "bulk spreading" regime prior to the "kinetic roughening" regime, with a fast flow region in between.

After placing the mercury droplet on the thin silver layer (a), the droplet starts to spread and react (or dissolve) with the film (b). This "bulk spreading regime", is mainly controlled by chemical reaction and diffusion both on top and inside the silver film. After crossing the entire film downwards, the mercury material touches the underlying glass substrate (c). This is a critical event, as the film-glass interface enters the game and as a dominant player. At this very moment, a new spreading regime, which we call the “fast-flow regime,” occurs abruptly. A new and thin front (500 Å in height), which optically looks like a halo, detaches from the bulk (d) and flows ahead throughout the entire film (e) with a much higher velocity (about two orders of magnitude faster). This is since there is effectively no energy barrier at the Hg-glass interface and the fast flow at this interface can easily lower the entire system energy. The fast-flow dynamics gives rise to the formation of a reaction band on top of the mercury film surface (e), advancing with the average velocity of the bulk propagation regime, and containing various chemical compositions and intermetallic phases [

30,

31]. This reaction band is where the "kinetic roughening" regime takes place. This will be discussed in detail in the next section.

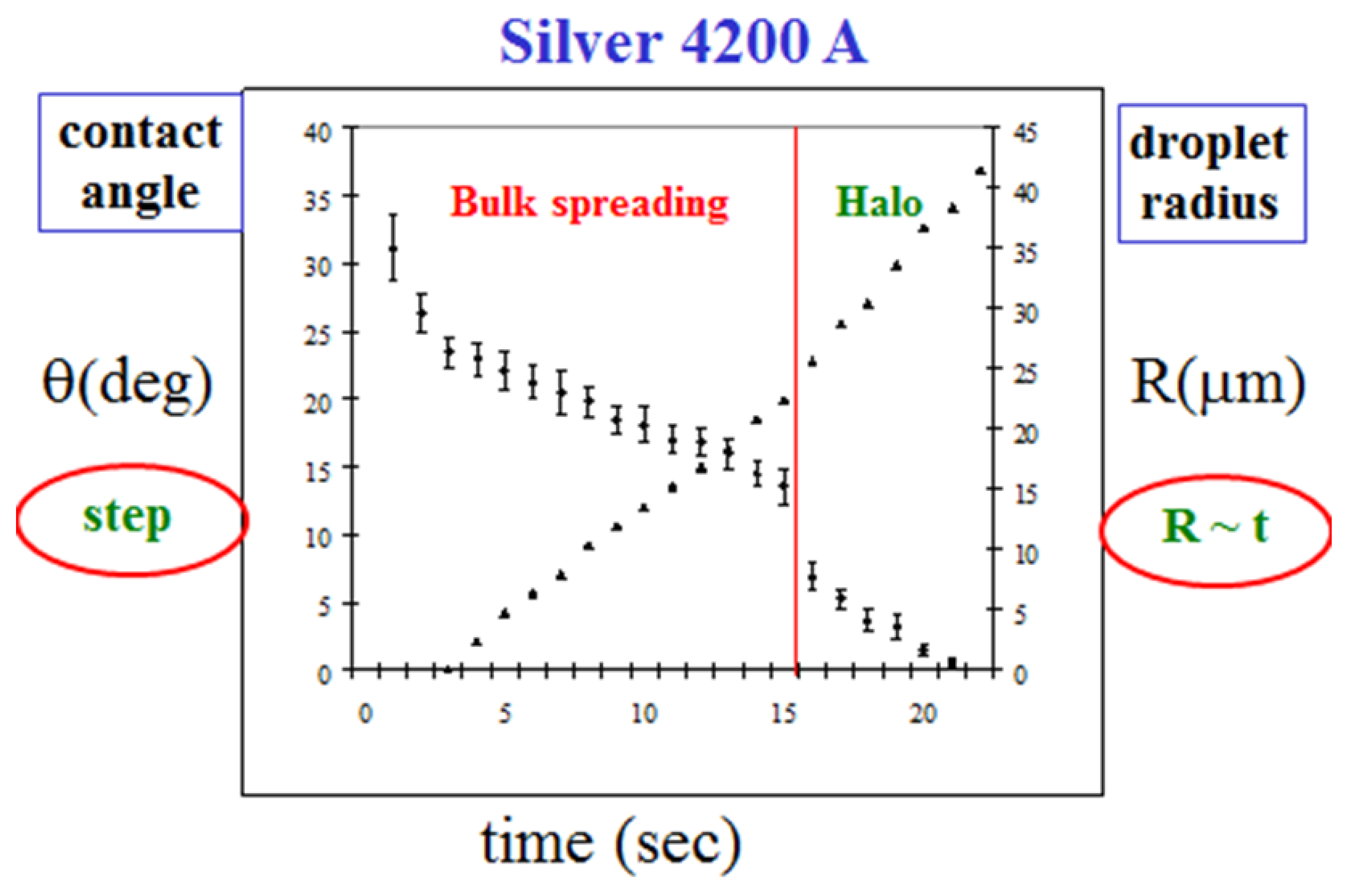

3.1. Bulk Spreading

In

Figure 6, we show our empirical results for the parameters of the bulk spreading, the radius

R(

t) and the angle

θ(t), for the data of

Figure 4. Initially, the droplet radius grows linearly in time,

R(t) ~ t, with a constant velocity, in this case 2.1 m/s, and the angle of contact

θ(t) decreases continuously. At about

t = 15 s,

θ(t) demonstrates a sudden step in its decreasing trend. This is exactly the time when the mercury crosses the entire silver layer for the first time and touches the underlying glass (

Figure 5c). We define this characteristic time as

td, where

d is the thickness of the Ag layer. Hence the step in the behavior of

θ(t) at

td is strongly

thickness dependent. On the other hand, the velocity of the bulk propagation was found to be approximately the same for all Ag thicknesses around 4200 Å (2000, 3000, 3500, 3800, 4200, 5000, and 6000 Å), having the average value of 2.5±0.4 m/s. It is reasonable to assume that this velocity is

material dependent, depending on the reaction of the mercury droplet with the silver surface. This surface velocity is much higher (about two orders of magnitude) than the mercury-silver reaction rate

inside the silver film which is attenuated by diffusion [

30]. The constant velocity remains approximately the same also after

td, with a very slight variation at

td, the time of the fast flow burst. The halo velocity at this regime is also constant, but its specific value is expectedly thickness dependent. It is also important to point out that

td is also the time where the kinetic roughening of the reaction band starts to show up (

Figure 5e).

The bottom line is that the underlying glass plays a significant role in the transition of the system behavior from bulk spreading to kinetic roughening. Hence, spreading of metal liquid on metal-on-glass, which is one of the features of our system, is quite different from spreading of metal on metal. The glass is more than just a platform.

3.2. Kinetic Roughening

In nonequilibrium surface and interface growth processes, kinetic roughening is the statistical physics framework to follow the stochastic dynamics in the processes, which induce scaling laws for the advancing interfaces with respect to time and length scales [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. It is applicable to a large variety of systems, such as tumor growth [

48,

49], bacterial and colonies [

50,

51,

52], biological systems [

53], reaction-diffusion fronts [

54], urban growth [

55], urban skyline [

56], forest fires [

57], slow combustion of paper [

58], drying wet paper [

59], paper wetting [

60], thin film spreading [

61,

62], magnetic flux fronts [

63], viscous fingering [

64] and more [

65,

66].

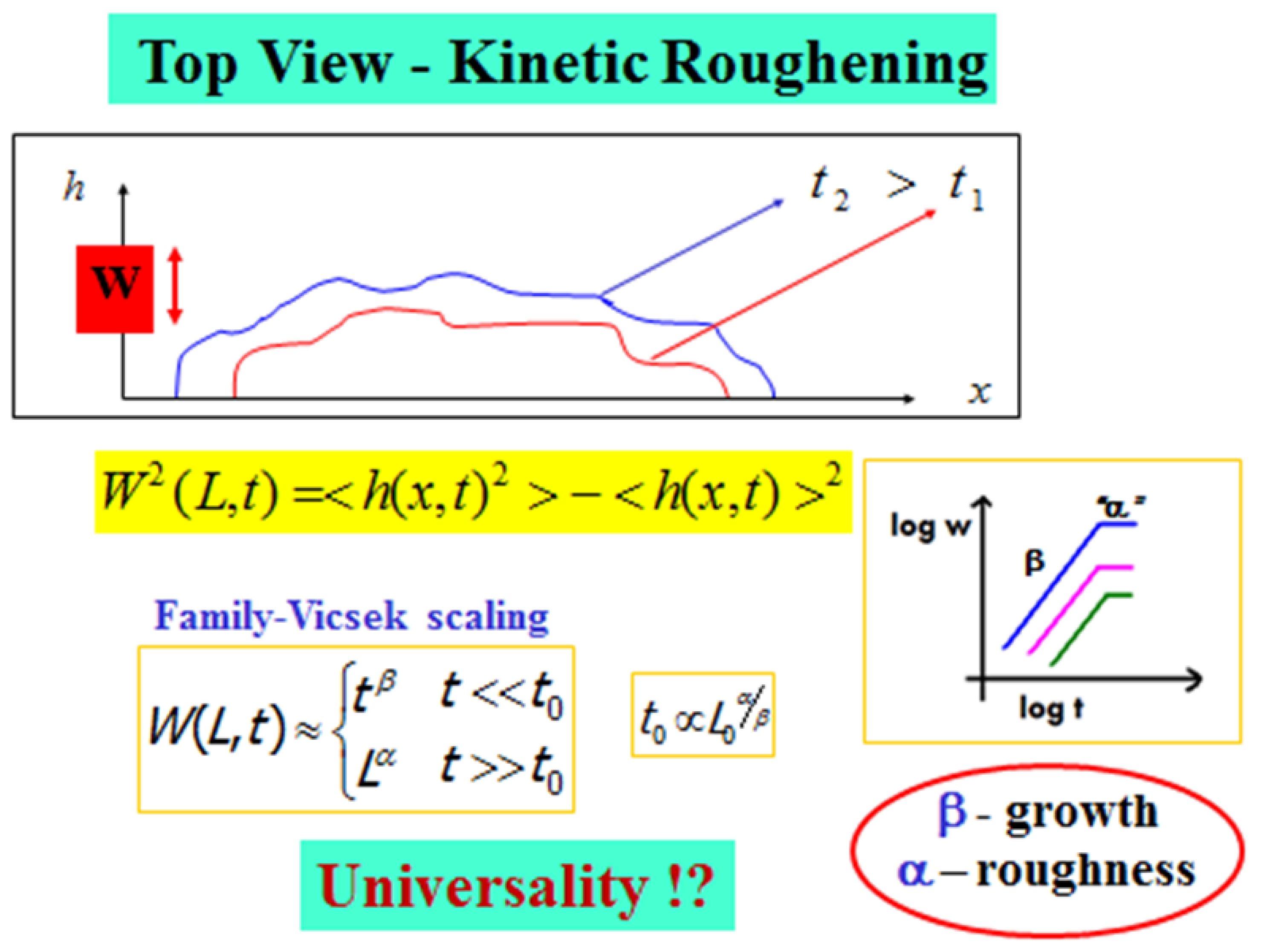

In

Figure 7 we illustrate the top-view of an advancing interface, described by a function

h(x,t), for the horizontal "height" of the interface at position

x at time

t. The kinetic roughening properties of an interface of length

L0 are defined based on the fluctuations or the second moment of

h(x,t). This width function,

W(L,t), is defined as

where the average is over all

x values between

0 or the minimal length scale in the system (e.g. lattice unit) up to half of the system size

L0/2. Family-Vicsek [

44] assumed that the width behavior obeys a scaling relation from which follows a dichotomic behavior,

with

and

β being the roughness and growth exponents, respectively, and

t0 is given in terms of the system size

L0 as

At the beginning of the process, the interface width increases as

. This continues up to time

t0 ≈ L0α/β, when the interface width saturates. At this saturation regime, the width behaves as

, and one can extract the interface roughness defined by the roughness exponent

α, which is related to the interface's autocorrelation. The growth exponent β describes the temporal dynamics of the interface, while the roughness exponent α, which is measured after the interface width reaches saturation, describes the geometric shape of its final stage. Based on these two exponents one can classify the system into a certain

universality class [

40,

41,

42,

43] that may shed light on the fundamental mechanisms in the process.

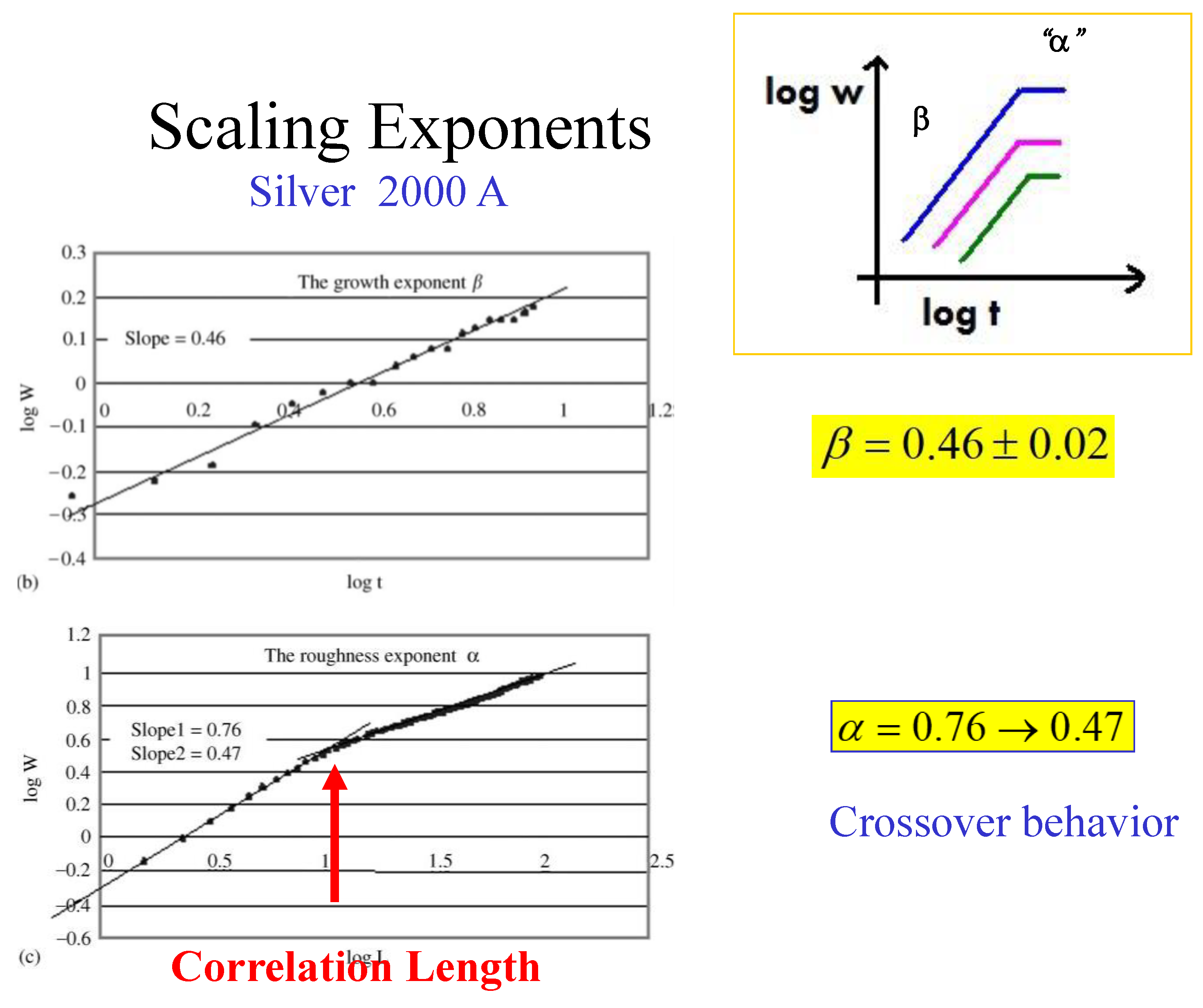

4. Scaling Exponents

4.1. The Roughness and Growth Exponents

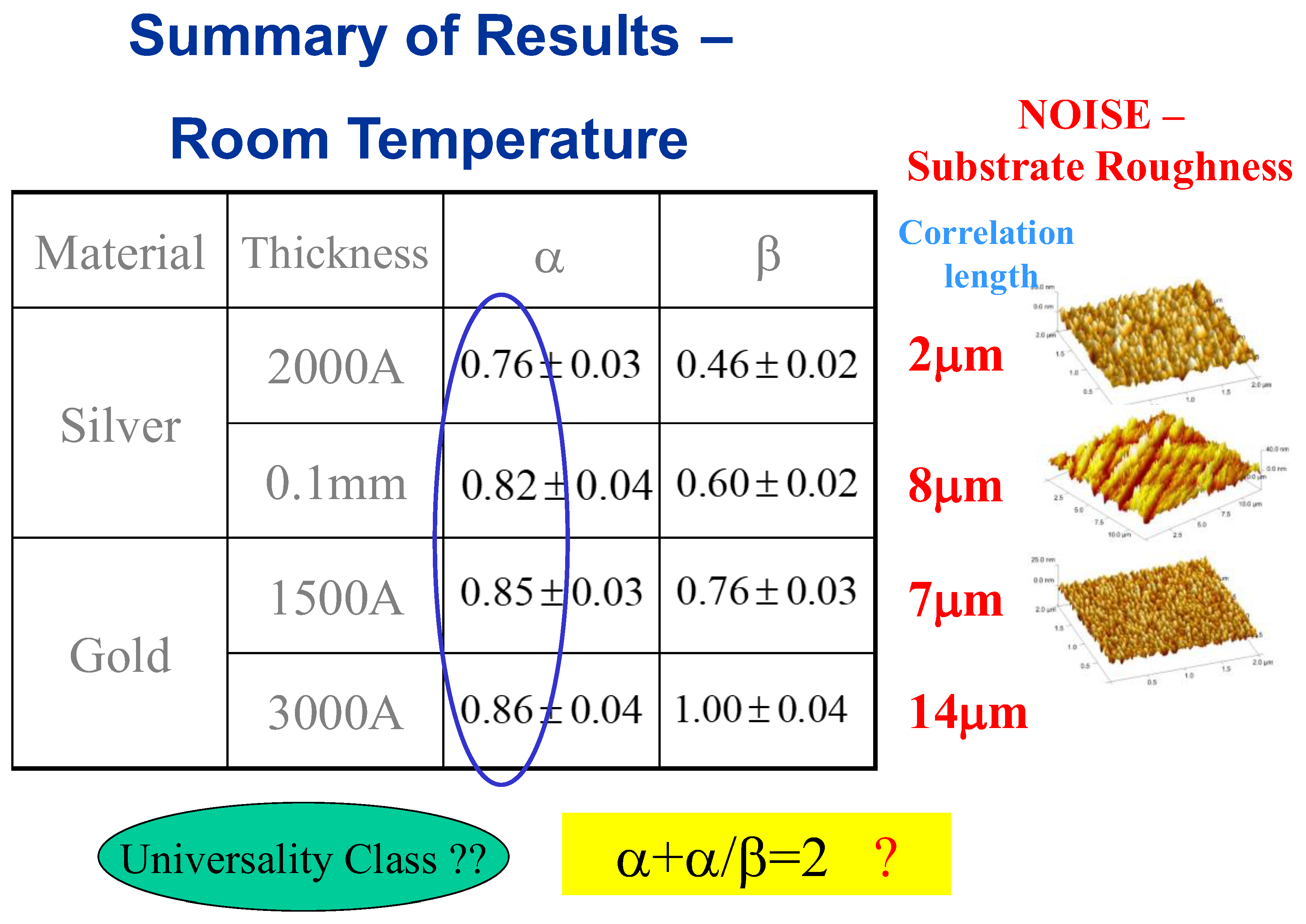

In

Figure 8 we show a typical set of kinetic roughening scaling exponents, obtained for a 2000 Å thick silver film evaporated on top of glass. The results are

for the growth exponent and

for the roughness exponent. However, the experiments reveal another interesting characteristic of the roughness exponent. Plotting this exponent as a function of distance (according to Eq. 2) one obtains a crossover behavior from

at short distances to around

at longer distances. This calls for a deeper look into the meaning of the roughness exponent which reflects the inner correlations of the advancing interface [

28,

29].

When

, there is a strong correlation between nearby interface points which tend to progress in a similar manner, with

for a smooth interface.

describes a lack of correlation (random walk), where every point on the interface moves randomly and independently on the surroundings.

describes anticorrelations between the points. Hence, the crossover behavior of

α in

Figure 8 from

to 0.47, represents a change of the correlation along the interface, from a relatively strong correlation at short distances to a complete loss of correlation at long distances. This is quite intuitive. The crossover occurs at some typical distance which is termed the “correlation length” of the interface.

This correlation length can be also extracted from temporal width fluctuations of the growing interface in its growth regime. The fluctuated behavior results from competing mechanisms in the growth process, the normal growth and the surface tension. This is discussed in detail in [

28,

29].

Regarding the classification of the system into a specific universality class, a common practice in statistical physics, a possibly relevant universality class is

, valid for isotropic systems [

40,

41]. In

Figure 9 we show some more examples of sets of exponents, obtained for a variety of thin films in various thicknesses at room temperature, which show that this is not the case. While the roughness exponent

α seems to be always around 0.8 (at distances shorter than the correlation length) for all cases, the growth exponent

β is significantly different in each system.

This can be attributed to the very different substrate roughness (prior to the mercury droplet deposition) resulting from different thicknesses and preparation conditions. It is also reflected in the different correlation length for each case, as shown next to the table. It is assumed that these different parameters affect the advancing interface growth process (hence the different growth exponent β ), while the roughness exponent α at the saturation regime of the process is more universal.

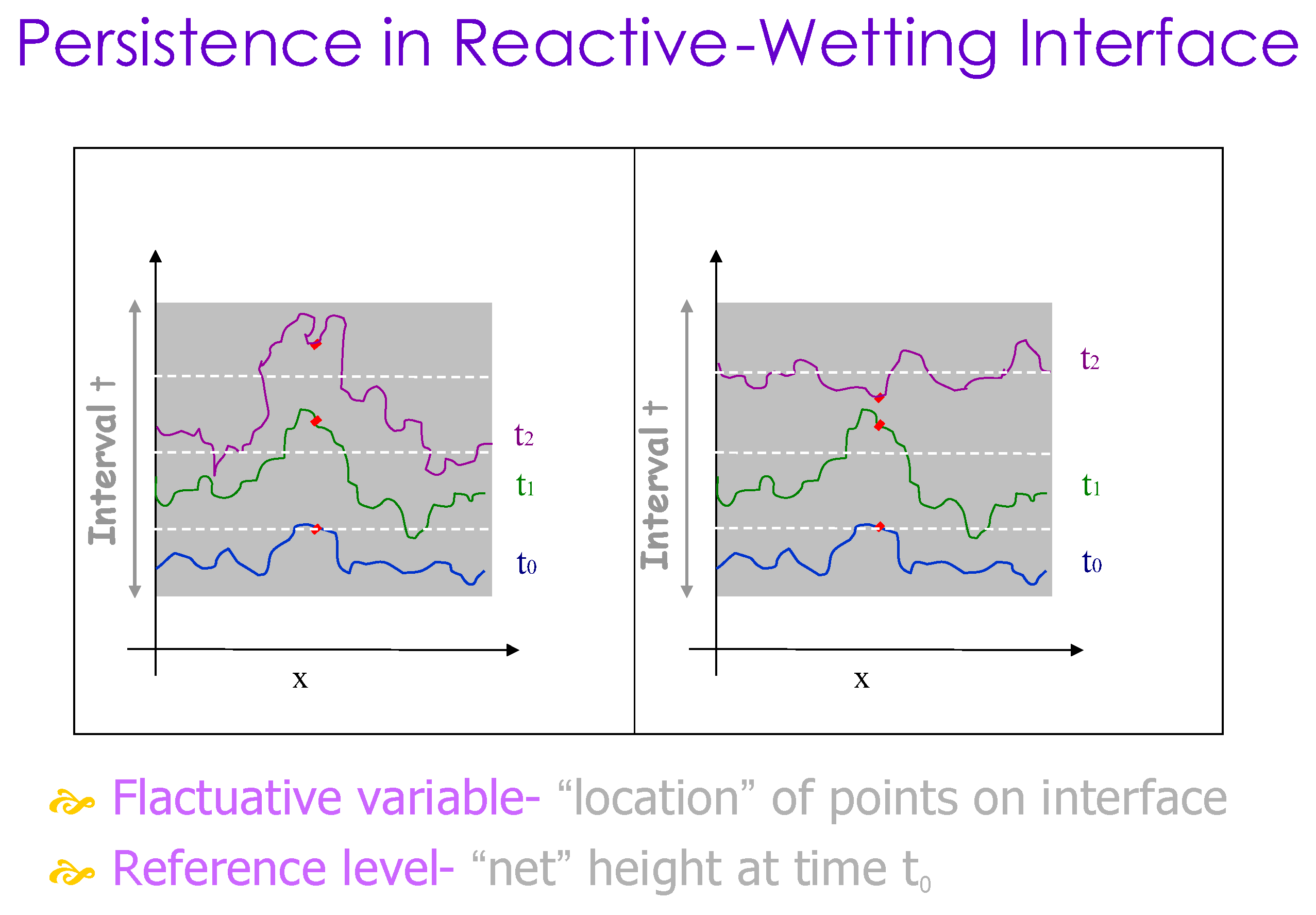

4.2. The Persistence Exponent

The microscopic dynamics of the interface can also be described by another measure, the

persistence probability, defined as the probability that a

stochastic variable will never cross some

reference level within a time interval

t [

47]. In our system the stochastic variable is the location of the interface point(s) along the interface line, and the reference level is the horizonal height

h(x,t) at the point location x at some initial time t

0 (see

Figure 10). It is then averaged over all points in a computational method which is described in detail in Ref. [

34]. This measure is considering local microscopic fluctuations and is expected to reflect an additional statistical physics view on the dynamics of the interface, complementing the more traditional growth exponent.

The persistence probability was shown to obey a power law decay (4) with a persistence exponent

θ [

47]

In linear systems there is a simple relation between the two temporal measures, the growth and the persistence exponents [

47]

Hence, in linear systems one can either measure the persistence exponent directly or indirectly using the growth exponent .

What happens in a

nonlinear system like reactive-wetting or droplet spreading ? In [

34] we report the direct persistence exponent results of the mercury droplet (150 μm) spreading on silver (4000

Å)-on-glass at room temperature. We were able to identify several distinct kinetic time regimes in this process. In the first one, while the interface (i.e. the contact line) is moving but its width is not yet growing, the persistence exponent is

= 0.55 ± 0.05, which is typical for a random, noisy behaviour. In the second regime, there is an effective growth of the interface width with a growth exponent

= 0.67 ± 0.06 followed by a final regime of saturation, according to the Family-Vicsek description of interface growth. The persistence exponent in this regime is

= 0.37 ± 0.05, which indicates that the hyper scaling relation

= 1 −

β seems to hold even for this nonlinear experimental system. The roughness exponent

α, calculated at the end of the process according to Eq. (2) was found to be 0.

83 ± 0.008 [

32], in agreement with previous studies of this system [

24,

28,

29].

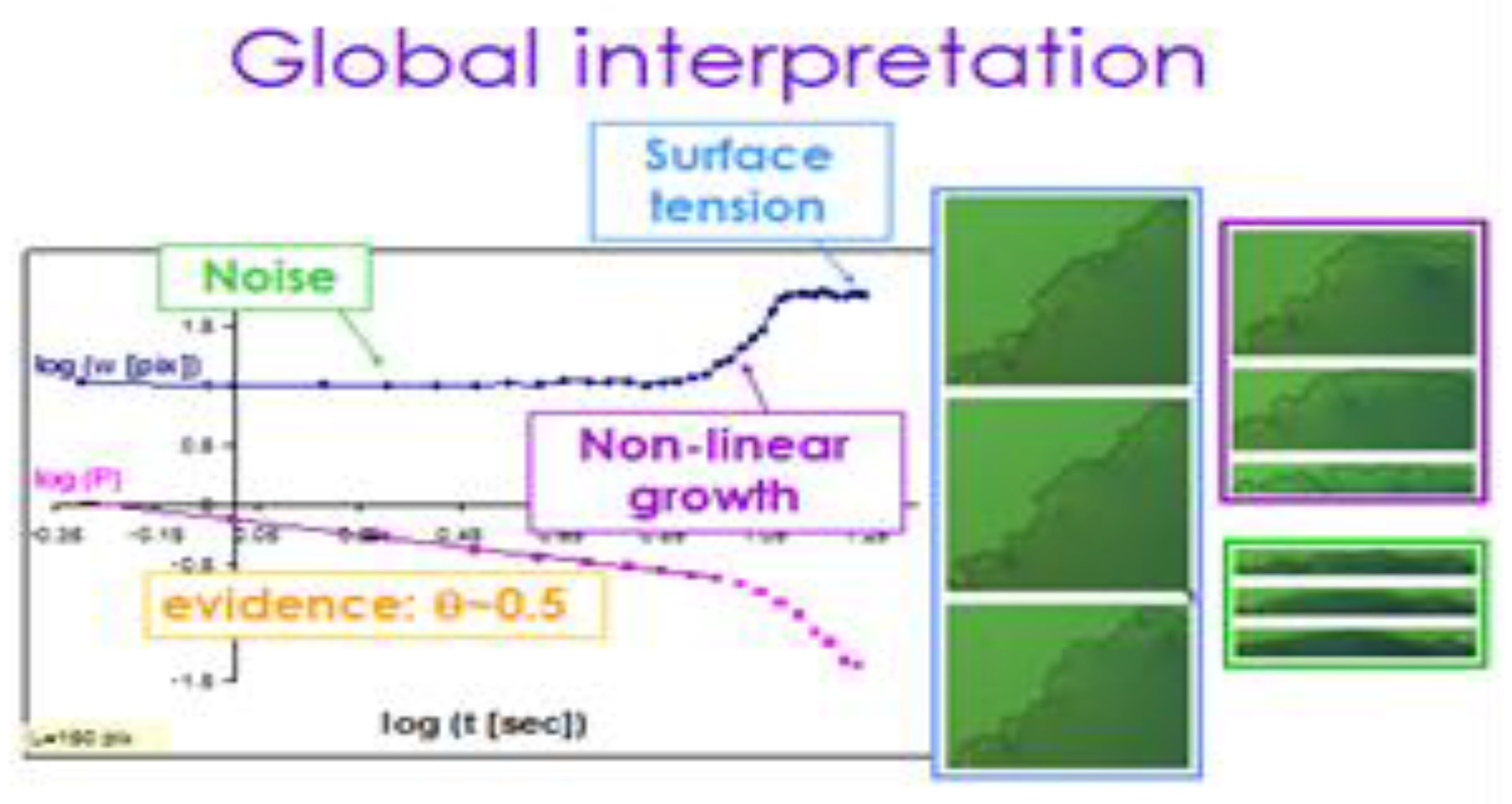

4.3. The Big Picture

Using this insight, we can now look at the “big picture” of the spreading process in our system. In

Figure 11 we summarize the three sub-regimes in the kinetic roughening process of the interface – noise (light green), non-linear growth (purple), and surface tension relaxation (light blue). The upper curve shows the width of the interface

W(t) as a function of time, starting with a region of noisy constant width followed by regions of growth (with the growth exponent

) and then saturation (where the roughness exponent

is measured) as in the inset of

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 above. The lower curve is the independent calculation of the complementary persistence curve, showing the random walk exponent –0.5 for the initial noisy region. The detailed calculation of the persistence exponent in the other two regions requires a shift of the initial time, as is explained in detail in Ref. [

34].

The snapshots presented on the right side of the figure are examples of the time evolution of the interface at each of the three sub regions. One can see the significant increase of the width in the purple growth region, compared with the constant (in time) width in both the preceding noise region (light green) and the succeeding surface tension relaxation / saturation region (light blue).

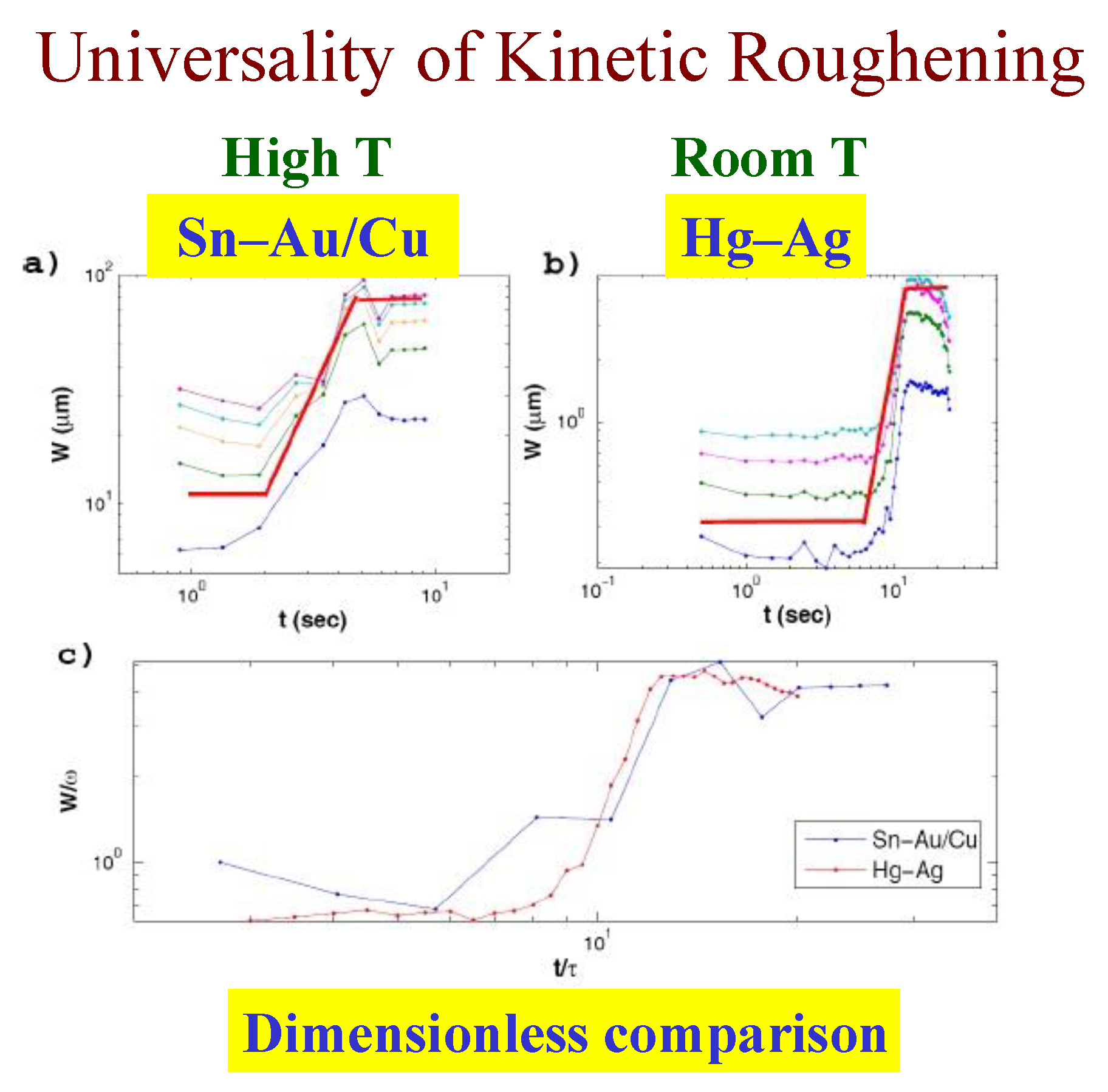

4.4. Universality – High Temperatures

Most of the spreading results in

high-temperature reactive-wetting systems were obtained using

side view of the spreading droplet (see, e.g. [

22]). One of the exceptions is a series of

top view experiments performed by Singler’s group at Binghamton [

17,

18,

33]. They performed experiments of Sn droplets spreading on a 1

μm coating of Au on Cu of thickness 12

μm, deposited on glass, at several high temperatures (390 ◦C). For detailed information on the experimental setup see Yin et al. [

17]).

The kinetic roughening patterns at high temperatures are shown in

Figure 12. They are quite similar to the room temperature patterns presented above. Analyzing the data in the same methodology and plotting the interface width

W as a function of time, one obtains the three typical regimes of the interface dynamics [

33]. It should be mentioned that in the high temperature system there is an additional early and extremely short time regime in which the liquid spreads with no discernible morphological or chemical change of the interface. This very early regime is undetectable in the room temperature reactive-wetting experiment [

33,

34].

The persistence concept allows one to better understand and clearly define these regimes. The dimensionless comparison of the three regions in the room temperature Hg–Ag system and the high temperature Sn–Au/Cu system shown in

Figure 13 speaks for itself.

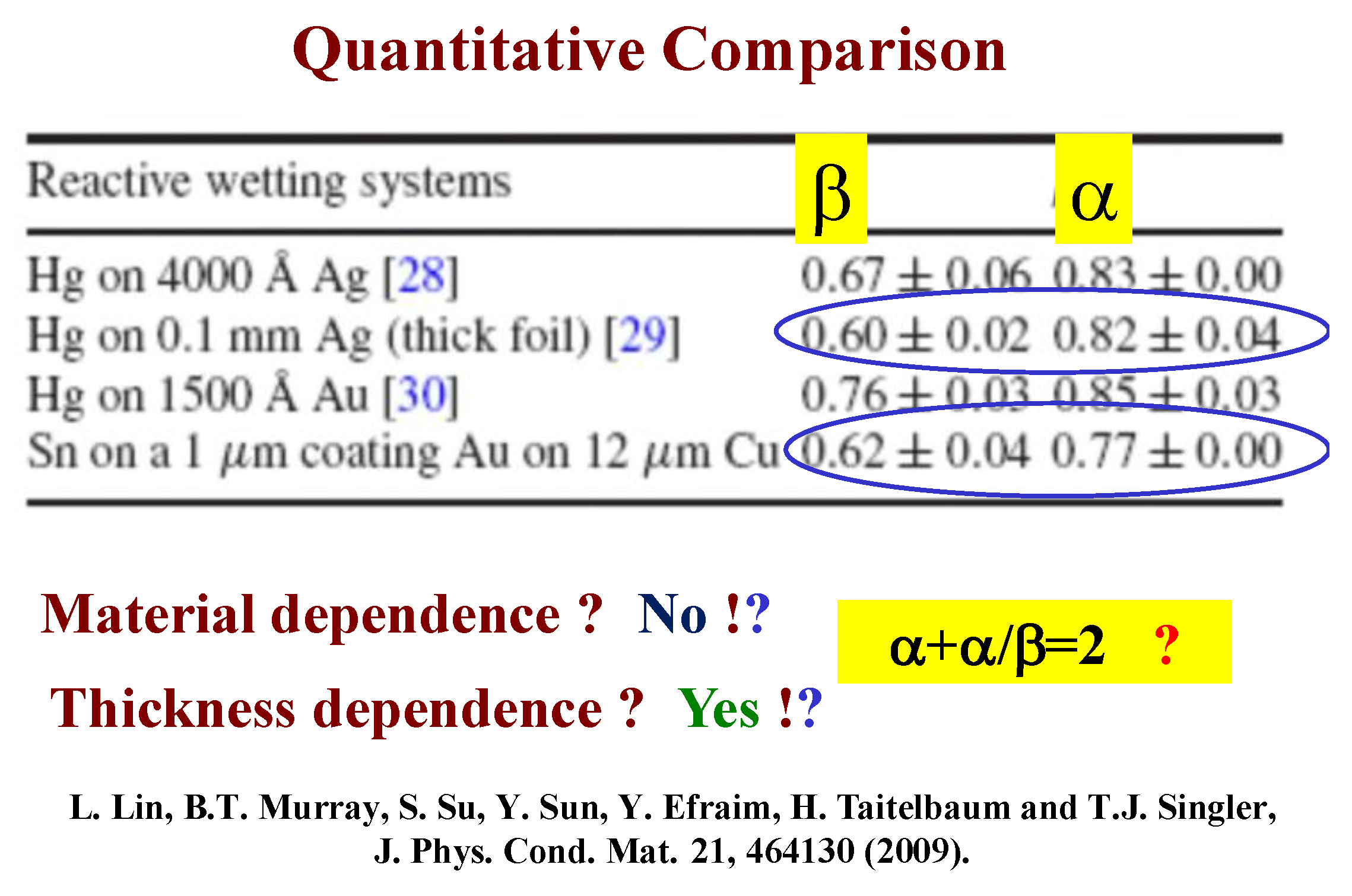

This comparison allows one to compare quantitatively the similarity between reactive wetting experiments of different materials in various thicknesses, as reflected by the kinetic roughening exponents

α and

β (

Figure 14). One can see that the growth exponent of the system under study, Sn–Au/Cu, is very close to the growth exponent of Hg on thick Ag (second and forth lines). The value of the roughness exponent

α is usually around 0.8 with variation that can be caused by other effects, like overhangs [

32]. Therefore, it seems that the Sn–Au/Cu belongs to the same universality class as the Hg–Ag system. According to the value of the exponents, we conjecture that this could be the QKPZ universality class whose exponents are

β = 3

/5 and

α = 3

/4 [

40]. This conjecture should be confirmed by additional experiments. The Hg–Au system belongs to a different universality class; however, it obeys the same hyper-scaling relation, as discussed in detail in [

25].

4.5. Kinetic Roughening, the QKPZ Equation and the Ising Model

The natural question to be asked is whether there exists a well-defined model to describe the interface dynamics of the reaction-diffusion system. In [

32] we investigated two candidates for this task, the QKPZ equation and the Ising chain model in zero temperature. The QKPZ is an explicit equation for describing advancing interfaces, while a given configuration of the spins in an Ising ferromagnetic 1d chain can be converted into a landscape, i.e. can be thought of as an interface. The QKPZ equation was studied in the context of its kinetic roughening exponents, but not for its persistence. The persistence exponent of the Ising model has been calculated, but the kinetic roughening exponents of an Ising chain were not. For more details see Ref. [

32].

In [

32] we calculated for each model its persistence, growth and roughness exponents, and compared them with the available experimental results in room temperature. The results are given in

Table 1. We found that none of these two models gives a complete description of the dynamics of the experimental reactive-wetting system, but each one of them describes quantitatively some aspects of the interface growth process.

We suggest that the behavior of our reactive-wetting system is dichotomic. While kinetic roughening has to do with the collective behavior of the advancing interface, (allowing e.g. for estimation of the lateral correlation length [

28,

29]), the microscopic persistence measure is much more sensitive [

47]. In the macroscopic scale, reflected by the growth exponent, the behavior of the system is QKPZ like, but in the microscopic scale, reflected by the persistence exponent, the system shows Ising-like behavior. This might be supported by the observation that local surface tension resembles the neighboring interactions in the Ising chain, which are dominant for relatively small scales. In larger scales, however, the non-linear growth of the interface is more profound, due to the chemical interaction with the substrate. This growth is better described by the QKPZ equation. These conjectures should be further substantiated

The interpretation of the results for the roughness exponent

[

32] is based on the observation that in the final stages of the spreading process, the interface propagation is not necessarily perpendicular only. This results in an overhangs geometry of the advancing interface which was shown to affect the value of the roughness exponent.

4.6. Effect of Temperature on Kinetic Roughening Exponents

So far, we have described spreading experiments around room temperature. A reasonable question is what is the effect of slight temperature variations

around this temperature. To study experimentally such possible effect, we have used a heating stage which allowed us to change the temperature in a controlled manner in the range -15°

C <

T < 25°

C . Higher temperatures are more difficult to handle with respect to the mercury vapors. The spreading of a mercury droplet (~150

μm) on a silver substrate (4000

Å) at these temperatures was monitored using the optical microscope as in the room temperature experiments. The full details can be found in [

35].

First, we studied the temperature effect on the wetting dynamics (droplet radius and velocity). We found that for all studied temperatures, the spreading radius R(t) grows linearly with time,

R(t) ~ t, with the specific velocity value (the proportionality constant) depending on the specific temperature. We also studied the temperature effect on the kinetic roughening properties of the advancing interface (growth and roughness exponents). Our results [

35] are that the growth exponent

β increases with temperature while the roughness exponent

α is relatively constant for or all studied temperatures, with a value around 0.8. In the literature, there are a variety of dependencies of kinetic roughening exponents on temperature [

35]. Our results show that it depends on the specific system.

In sum, the temperature does play a role in the behavior of reactive-wetting systems, not only in very high temperatures, but also in lower, around room temperatures.

5. Summary

The spreading of a droplet on metal-on-glass is highly non-linear and very sensitive to minor fluctuations. It’s extremely difficult to construct a comprehensive model which fully describes it. Alternatively, one can look at the top-view data of the dynamics and geometry of the horizontal morphology of the advancing triple line. A statistical physics analysis of the common kinetic roughening properties of similar systems can yield universal insights (

Figure 15), allowing for a better understanding of dynamical aspects of the process.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a written summary of numerous talks presented on this subject in international conferences and workshops. I am indebted to my former students Avraham Be’er, Inbal Hecht, Yael Efraim, Meital Harel and late Tal Grynpas-Ya’akov for their immense contribution to this project throughout the years. I am highly thankful to my colleagues Yossi Lereah, Aviad Frydman and of course to Timothy Singler and his group at Binghamton University for their contribution and hospitality.

References

- de Gennes, P.G. Wetting: Statics and Dynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1985, 57, 827. [CrossRef]

- Leger, L.; Joanny, J.F. Liquid Spreading. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1992, 55, 431. [CrossRef]

- Oron, A; Davis, S.H.; Bankoff, S.G. Long-scale evolution of thin liquid films. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1997, 69, 931. [CrossRef]

- de Gennes, P.G. The dynamics of reactive wetting on solid surfaces. Physica A 1998, 249, 196–205. [CrossRef]

- Bonn, D.; Eggers, J.; Indekeu J.; Meunier, J.; Rolley, E. Wetting and Spreading. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 739-805. [CrossRef]

- Tadmor, R. Approaches in wetting phenomena. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 1577–1580. [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.M. A review of physics of moving contact line dynamics models and its applications in interfacial science. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 080701. [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.M.; Suszynski, W.J. Physics of Dynamic Contact Line: Hydrodynamics Theory versus Molecular Kinetic Theory. Fluids 2022, 7, 318 (This special issue). [CrossRef]

- Tanner, L.H. The Spreading of Silicone Oil Drops on Horizontal Surfaces. J. Phys. D. 1979, 12, 1473–1484. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.; Miller, C.A.; Ruckenstein, E. Spreading kinetics of liquid drops on solids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1976, 56, 460. [CrossRef]

- Blake, T.D. Dynamic contact angles and wetting kinetics in Wettability, J.C. Berg (Ed.), Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1993.

- Davidovitch, B.; Moro, E.; Stone, H. A. Spreading of Viscous Fluid Drops on a Solid Substrate Assisted by Thermal Fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 244505. [CrossRef]

- Landry, K.; Eustathopoulos, N. Dynamics of wetting in reactive metal/ceramic systems: linear spreading. Acta Mater. 1996, 44, 3923. [CrossRef]

- Eustathopoulos, N. Dynamics of wetting in reactive metal/ ceramic systems. Acta Mater. 1998, 46, 2319. [CrossRef]

- Eustathopoulos, N.; Nicholas, M.G.; Drevet, B. Wettability at High Temperatures, Pergamon: New York, USA, 1999.

- Kumar,G.; Prabhu, K.N. Review of non-reactive and reactive wetting of liquids on surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 133, 61–89. [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Chauhan, A.; Singler, T.J. Reactive wetting in metal/metal systems: Dissolutive versus compound-forming systems. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 495, 80-89. [CrossRef]

- Singler, T.J.; Su, S.; Yin, L.; Murray, B.T. Modeling and experiments in dissolutive wetting: a review. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47,8261–74. [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, E. Wetting of Real Surfaces, de Gruyter, Berlin, 2013.

- Bormashenko, E. Apparent contact angles for reactive wetting of smooth, rough, and heterogeneous surfaces calculated from the variational principles. J. Colloid and Interface Sci. 2019, 537, 597–603. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q. ; Xie, K.; Sui, R.; Mu, D.; Cao, R.; Chang, J.; Qiu, F. Kinetic analysis of wetting and spreading at high temperatures: A review. Adv. Colloid and Interface Sci. 2022, 305, 102698. [CrossRef]

- 10th International Conference on High Temperature Capillarity, HTC 2022, Kraków, POLAND, Book of Abstracts, HTC 2022 September 12–16, 2022 ISBN 978-83-963247-1-9.

- Be’er, A.; Lereah, Y.; Taitelbaum, H. The Dynamics and Geometry of Solid-Liquid Reaction Interface. Physica A 2000, 285, 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Be’er, A.; Lereah, Y.; Hecht, I.; Taitelbaum, H. The Roughness and Growth of a Silver-Mercury Reaction Interface. Physica A 2001, 302, 297-301. [CrossRef]

- Be’er, A.; Lereah, Y.; Frydman, A.; Taitelbaum, H. Spreading of a Mercury Droplet on Thin Gold Films. Physica A 2002, 314, 325-330. [CrossRef]

- Be’er, A.; Lereah, Y. Time-resolved, three-dimensional quantitative microscopy of a droplet spreading on solid substrates. J. Microscopy 2002, 208, 148-152. [CrossRef]

- Hecht, I.; Taitelbaum, H. Roughness and Growth in a Continuous Fluid Invasion Model. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 70, 046307-1-8. [CrossRef]

- Be’er, A.; Hecht, I.; Taitelbaum, H. Interface Roughening Dynamics: Temporal Width Fluctuations and the Correlation Length. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 72, 031606-1-9. [CrossRef]

- Hecht, I.; Be’er, A.; Taitelbaum, H. Single Interface Growth: Fluctuations and the Correlation Length. Fluct. and Noise Lett. 2005, 5, L319-L324. [CrossRef]

- Be’er, A.; Lereah, Y., Frydman, A.; Taitelbaum, H. Spreading of Mercury Droplets on Thin Silver Films at Room Temperature. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 75, 051601-1-7. [CrossRef]

- Be’er, A.; Lereah, Y.; Taitelbaum, H. Reactive-Wetting of Hg-Ag System at Room Temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 495, 102-107. [CrossRef]

- Efraim, Y.; Taitelbaum, H. Can Ising model and/or QKPZ equation properly describe reactive-wetting interface dynamics? Cent. Eur. J. Phys. 2009, 7, 503-508. [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Murray, B.T.; Su, S.; Sun, Y.; Efraim, Y.; Taitelbaum, H.; Singler, T.J. Reactive Wetting in Metal-Metal Systems. J. Phys. Cond. Mat. 2009, 21, 464130-1-11. [CrossRef]

- Efraim, Y.; Taitelbaum, H. Persistence in Reactive-Wetting Interfaces. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 050602-1-4 (R). [CrossRef]

- Harel, M.; Taitelbaum, H. Effect of Temperature on the Dynamics and Geometry of Reacting-Wetting Interfaces around Room Temperature. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 062801-1-7. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, M; Planting P.J. The wetting of metal surfaces by liquid mercury. ZEITSCHRIFT FUR METALLKUNDE 1969, 60, 10. [CrossRef]

- Vicsek, T. Fractal Growth Phenomena, 2nd ed. ,World Scientific, Singapore, 1992.

- Bunde, A.; Havlin, S. Fractals in Science, 2nd ed., Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1994.

- Bunde, A.; Havlin, S. Fractals and Disordered Systems, 2nd ed., Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1996.

- A. L. Barabasi and H. E. Stanley, Fractal Concepts in Surface Growth (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1995).

- Meakin, P. Fractals, Scaling, and Growth Far from Equilibrium, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1998.

- Halpin-Healy, T.; Zhang, Y.-C. Kinetic Roughening Phenomena, Stochastic Growth, Directed Polymers and all that. Aspects of Multidisciplinary Statistical Mechanics. Phys. Rep. 1995, 254, 215-414. [CrossRef]

- Alava, M.; Dube, M.; Rost, M. Imbibition in disordered media. Adv. Phys. 2004, 53, 83. [CrossRef]

- Family, F.; Vicsek, T. Scaling of the Active Zone in the Eden Process on Percolation Networks and the Ballistic Deposition Model. J. Phys. A 1985, 18, L75. [CrossRef]

- Kardar, M.; Parisi, G.; Zhang, Y. -C. Dynamic Scaling of Growing Interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 56, 889. [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, H. G. E.; Family, F. Scaling in Open Dissipative Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 66, 1982. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.N. Persistence in nonequilibrium systems. Curr. Sci. 1999, 77, 370.

- Br´u, A.; Pastor, J.M.; Fernaud, I.; Br´u, I.; Melle, S.; Berenguer, C. Super-Rough Dynamics on Tumor Growth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 4008. [CrossRef]

- Khain, E.; Sander, L.M. Dynamics and Pattern Formation in Invasive Tumor Growth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 188103. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jacob, E.; Schochet, O.; Tenenbaum, A.; Cohen, I.; Czirok, A.; Vicsek, T. Generic modelling of cooperative growth patterns in bacterial colonies. Nature 1994, 368, 46-49. [CrossRef]

- Huergo, M.A.C; Pasquale, M.A.; Gonz´alez, P.H.; Bolz´an, A.E.; Arvia, A.J. Growth dynamics of cancer cell colonies and their comparison with noncancerous cells. Phys. Rev. E 2012, 85, 011918. [CrossRef]

- Santalla, S.N.; Rodr´ıguez-Laguna, J.; Abad, J.P.; Mar´ın, I.; Espinosa, M.M.; Mu˜noz-Garc´ıa, J.; V´azquez, L.; Cuerno, R. Nonuniversality of front fluctuations for compact colonies of nonmotile bacteria. Phys. Rev. E 2018, 98, 012407. [CrossRef]

- Santalla, S. N.; Ferreira, S. C. Eden model with nonlocal growth rules and kinetic roughening in biological systems. Phys. Rev. E 2018, 98, 022405. [CrossRef]

- Barreales, B. G.; Melendez, J. J.; Cuerno, R.; Ruiz-Lorenzo, J. J. Kardar–Parisi–Zhang universality class for the critical dynamics of reaction–diffusion fronts. J. Stat. Mech. Theor. Exp. 2020, 023203. [CrossRef]

- Makse, H.A.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.E. Modelling urban growth patterns. Nature 1995, 377, 608–612. [CrossRef]

- Najem, S.; Krayem, A., Ala-Nissila, T.; Grant, M. Kinetic Roughening of the Urban Skyline. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 101, 050301(R). [CrossRef]

- Maunuksela, J.; Myllys, M.; Timonen, J.; Alava, M. J.; Ala-Nissila, T. Kardar–Parisi–Zhang scaling in kinetic roughening of fire fronts. Physica A, 1999, 266, 372-376. [CrossRef]

- Maunuksela, J.; Myllys, M.; Kähkönen, O.-P.; Timonen, J.; Provatas, N.; Alava, M. J.; Ala-Nissila, T. Kinetic Roughening in Slow Combustion of Paper. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 1515. [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S.; Morales, D.; Susarrey, O.; Samayoa, D. ; Trinidad, J.M.; Marquez, J.; García, R. Self-similar roughening of drying wet paper. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 73, 065105(R). [CrossRef]

- Balankin, A.S.; Paredes, R.G.; Susarrey, O.; Morales, D.; Vacio, F.C. Kinetic Roughening and Pinning of Two Coupled Interfaces in Disordered Media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 056101. [CrossRef]

- Harel, M.; Taitelbaum, H. Non-Universal Dynamic Exponents for Thin-Film Spreading. Europhys. Lett. (EPL) 2018, 122, 26002-1-6. [CrossRef]

- Harel, M.; Taitelbaum, H. Non-Monotonic Dynamics of Thin Film Spreading. Eur. Phys. J. E 2021, 44, 69. [CrossRef]

- Barness, D.; Efraim, Y.; Taitelbaum, H.; Sinvani, M.; Shaulov, A.; Yeshurun, Y. Kinetic Roughening of Magnetic Flux Fronts in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ Crystals with Columnar Defects. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 174516-1-5. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Yuya Kishimoto, Y. Fingering Instability of Binary Droplets on Oil Pool. Fluids 2023, 8, 138; This special issue. [CrossRef]

- Santalla, S.; Rodr´ıguez-Laguna, J.; Cuerno, R. Circular Kardar-Parisi-Zhang equation as an inflating, self-avoiding ring polymer. Phys. Rev. E 2014, 89, 010401(R). [CrossRef]

- Barreales, B.G.; Meléndez, J.J., Cuerno, R.; Ruiz-Lorenzo, J.J. Large-scale kinetic roughening behavior of coffee-ring fronts. Phys. Rev. E 2022 106, 044801. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Side view of the dynamics of wetting.

Figure 1.

Side view of the dynamics of wetting.

Figure 2.

The experimental system of liquid metal on solid metal-on-glass in room temperature under the optical microscope.

Figure 2.

The experimental system of liquid metal on solid metal-on-glass in room temperature under the optical microscope.

Figure 3.

Typical snapshots of mercury spreading on silver film on glass. From bulk spreading to kinetic roughening.

Figure 3.

Typical snapshots of mercury spreading on silver film on glass. From bulk spreading to kinetic roughening.

Figure 4.

Side-view reconstruction of the droplet shape in the spreading dynamics of mercury droplet on silver thin film. The bottom sketch is the real scale.

Figure 4.

Side-view reconstruction of the droplet shape in the spreading dynamics of mercury droplet on silver thin film. The bottom sketch is the real scale.

Figure 5.

Schematic sequence of mercury droplet spreading on thin silver films in room temperature. (a) Droplet placement on the film. (b) Droplet bulk spreading and reacting with the underlying substrate. (c) Mercury touching the glass. (d) Starting of the fast-flow regime, halo propagation. (e) Formation of a reaction band.

Figure 5.

Schematic sequence of mercury droplet spreading on thin silver films in room temperature. (a) Droplet placement on the film. (b) Droplet bulk spreading and reacting with the underlying substrate. (c) Mercury touching the glass. (d) Starting of the fast-flow regime, halo propagation. (e) Formation of a reaction band.

Figure 6.

The dynamics of the droplet radius and contact angle in the bulk spreading regime.

Figure 6.

The dynamics of the droplet radius and contact angle in the bulk spreading regime.

Figure 7.

Kinetic roughening, Family-Vicsek scaling and the scaling exponents.

Figure 7.

Kinetic roughening, Family-Vicsek scaling and the scaling exponents.

Figure 8.

The scaling exponents α and β and the crossover behavior at the correlation length.

Figure 8.

The scaling exponents α and β and the crossover behavior at the correlation length.

Figure 9.

Scaling exponents at room temperature, for various materials, thicknesses and preparation techniques.

Figure 9.

Scaling exponents at room temperature, for various materials, thicknesses and preparation techniques.

Figure 10.

Persistence in Reactive-Wetting Interfaces.

Figure 10.

Persistence in Reactive-Wetting Interfaces.

Figure 11.

Noise, non-linear growth and surface tension relaxation in the kinetic roughening process.

Figure 11.

Noise, non-linear growth and surface tension relaxation in the kinetic roughening process.

Figure 12.

Kinetic Roughening at High Temperature.

Figure 12.

Kinetic Roughening at High Temperature.

Figure 13.

Universality of kinetic roughening: High temperature vs room temperature. A dimensionless comparison.

Figure 13.

Universality of kinetic roughening: High temperature vs room temperature. A dimensionless comparison.

Figure 14.

High temperature vs room temperature: A quantitative Comparison.

Figure 14.

High temperature vs room temperature: A quantitative Comparison.

Figure 15.

High temperature vs room temperature: A qualitative comparison.

Figure 15.

High temperature vs room temperature: A qualitative comparison.

Table 1.

The persistence, growth and roughness exponents for reactive-wetting experiments, QKPZ and Ising simulations.

Table 1.

The persistence, growth and roughness exponents for reactive-wetting experiments, QKPZ and Ising simulations.

| |

Reactive-wetting experiment |

QKPZ

simulations |

Ising

simulations |

| Persistence |

|

|

|

| Growth b |

|

|

|

| Roughness a |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).