Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Experimental Setup

2.2. Preparation of PLLA-GO Nanocomposite

2.3. Cellular Characterization Techniques

2.3.1. Evaluation of Cell Adhesion and Morphology via Inverted Optical Microscopy

2.3.2. Morphological Characterization by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.3. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cell Cycle Distribution

2.3.4. Cell Proliferation Analysis by Generation Tracking with CFSE

2.3.5. Analysis of Mitochondrial Electrical Potential by Flow Cytometry

2.3.6. Analysis of Inflammatory Cytokines by Flow Cytometry (CBA)

| Cell Types | Kit | Catalog Number | Measured Cytokines | Manufacturer |

| FN1, HUVEC | Human Th1/Th2 Cytokine Kit | 551809 | IL-12p70, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, IFN-γ, MCP-1 | BD® Biosciences, Heidelberg, Alemanha |

| mBMSCs | Mouse Th1/Th2 Cytokine Kit | 551287 | IL-12p70, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, IFN-γ, MCP-1 | BD® Biosciences, Heidelberg, Alemanha |

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Cell Adhesion and Morphology by Inverted Optical Microscopy

3.2. Cellular Morphological Characterization by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.3. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cell Cycle Distribution

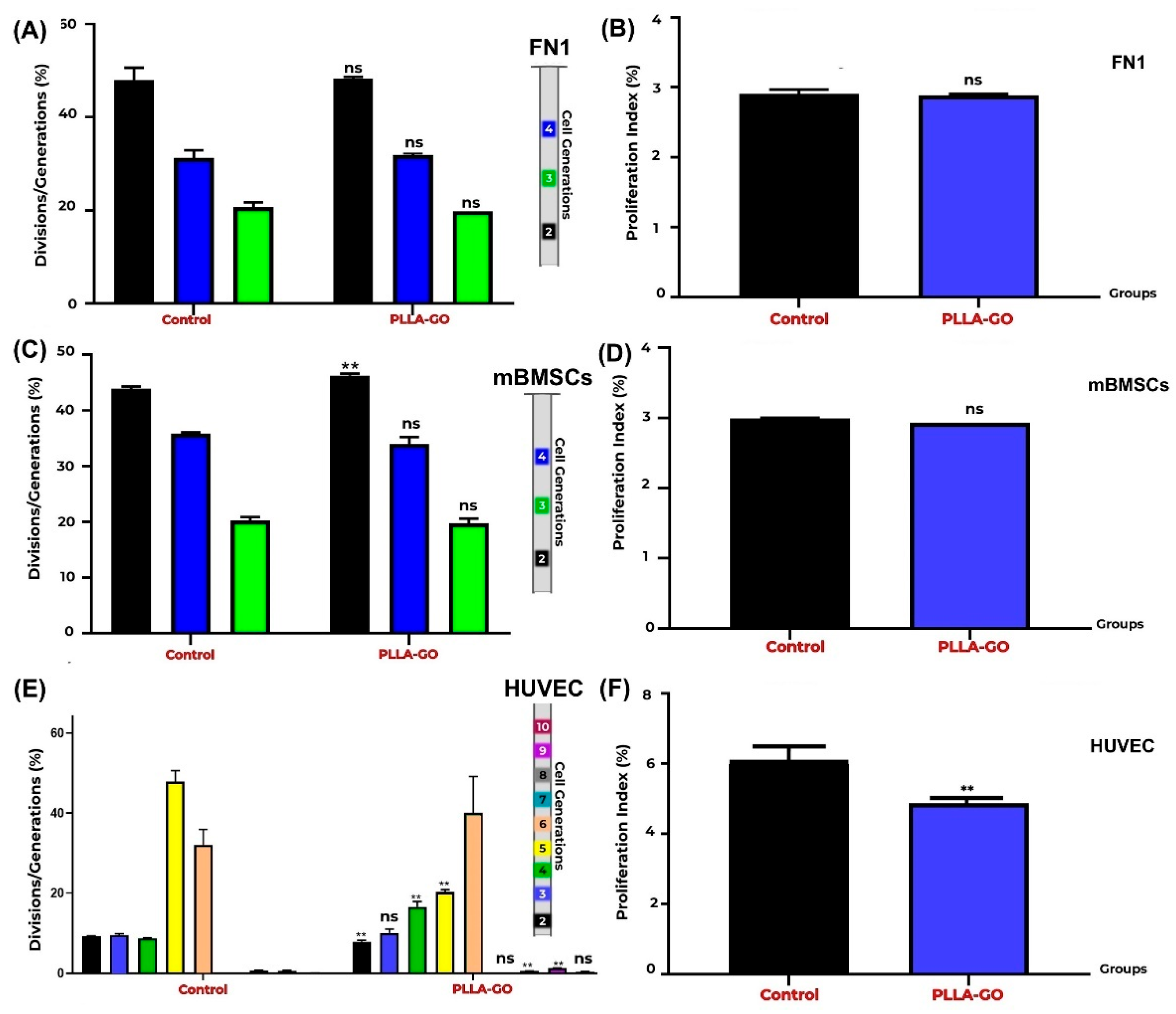

3.4. Cell Proliferation Analysis by Generation Tracking with CFSE

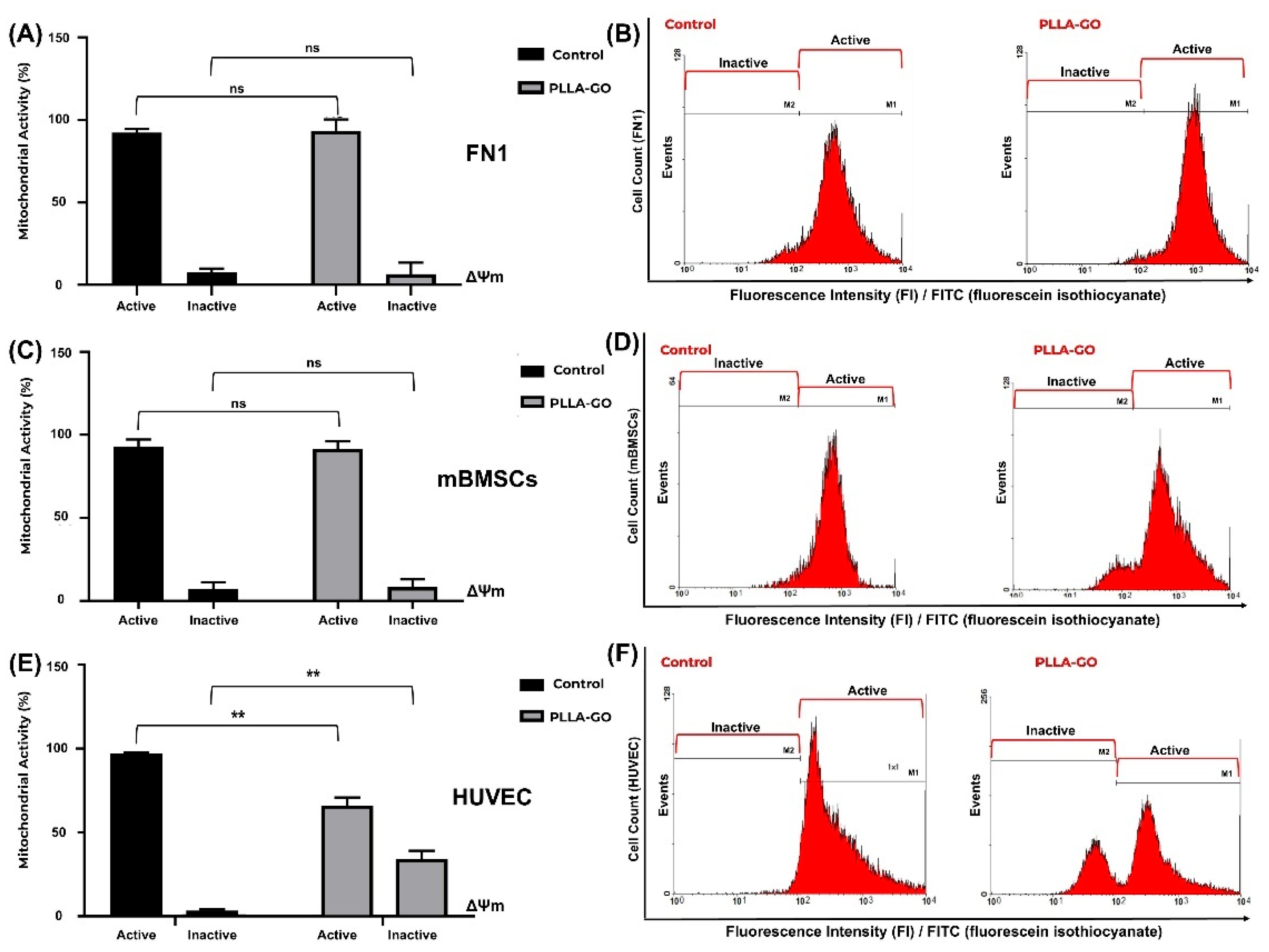

3.5. Analysis of Mitochondrial Electrical Potential by Flow Cytometry

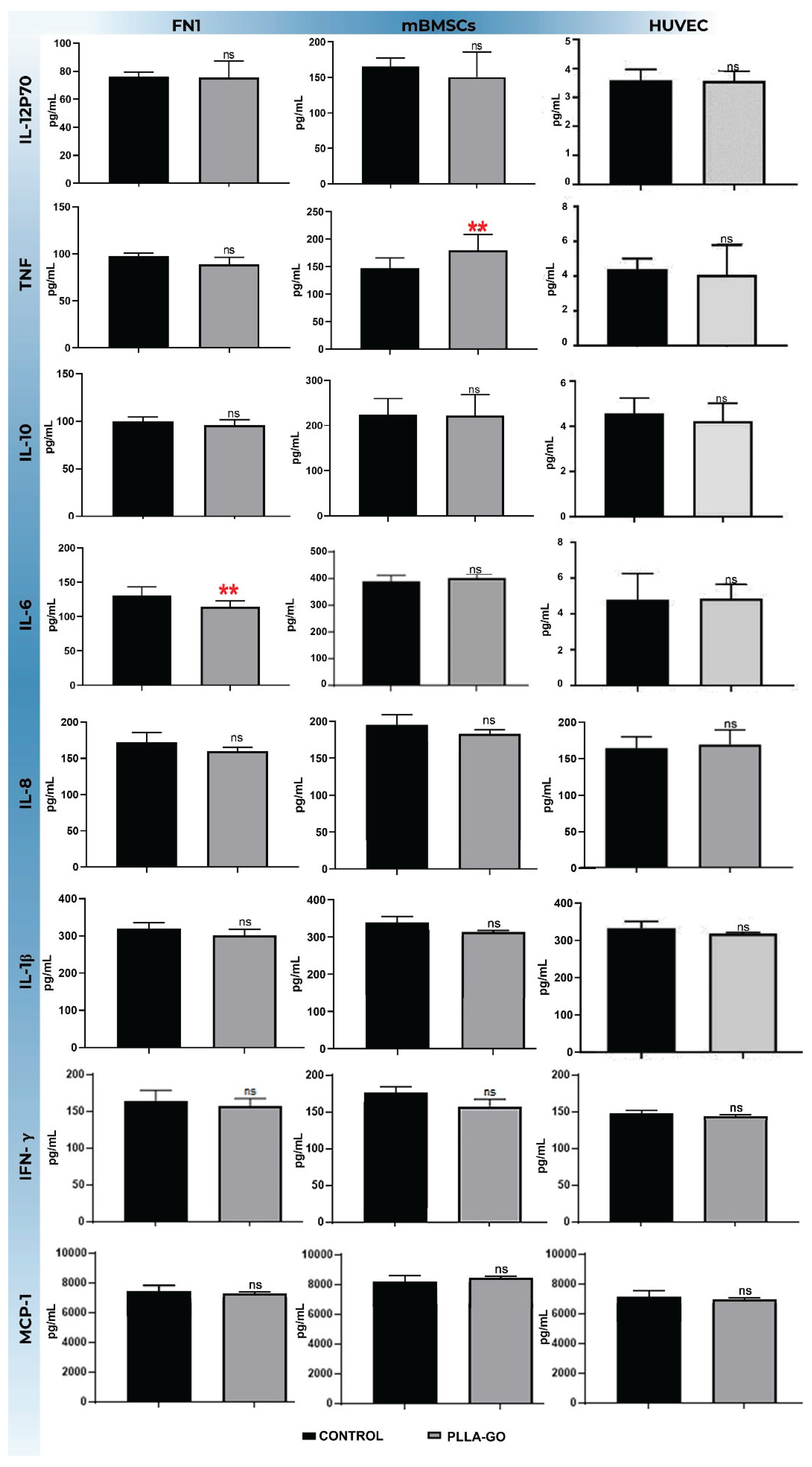

3.6. Analysis of Inflammatory Cytokines by Flow Cytometry (CBA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferraz, M.P. An Overview on the Big Players in Bone Tissue Engineering: Biomaterials, Scaffolds and Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farjaminejad, S.; Farjaminejad, R.; Hasani, M.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Abdouss, M.; Marya, A.; Harsoputranto, A.; Jamilian, A. Advances and Challenges in Polymer-Based Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering: A Path Towards Personalized Regenerative Medicine. Polymers 2024, 16, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzzio, N.; Moya, S.; Romero, G. Multifunctional Scaffolds and Synergistic Strategies in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Gholap, A.D.; Grewal, N.S.; Jun, Z.; Khalid, M.; Zhang, H.-J. Advances in Smart Hybrid Scaffolds: A Strategic Approach for Regenerative Clinical Applications. Engineered Regeneration 2025, 6, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Nasr, S.; Rabiee, N.; Hajebi, S.; Ahmadi, S.; Fatahi, Y.; Hosseini, M.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Ghadiri, A.M.; Rabiee, M.; Jajarmi, V.; et al. Biodegradable Nanopolymers in Cardiac Tissue Engineering: From Concept Towards Nanomedicine. Int J Nanomedicine 2020, Volume 15, 4205–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunatillake, P. Biodegradable Synthetic Polymers for Tissue Engineering. Eur Cell Mater 2003, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouri, N.G.; Bahú, J.O.; Blanco-Llamero, C.; Severino, P.; Concha, V.O.C.; Souto, E.B. Polylactic Acid (PLA): Properties, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications – A Review of the Literature. J Mol Struct 2024, 1309, 138243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limsukon, W.; Rubino, M.; Rabnawaz, M.; Lim, L.-T.; Auras, R. Hydrolytic Degradation of Poly(Lactic Acid): Unraveling Correlations between Temperature and the Three Phase Structures. Polym Degrad Stab 2023, 217, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, R.A.; Davies, M.C.; Tendler, S.J.B.; Chan, W.C.; Shakesheff, K.M. Controlling Biological Interactions with Poly(Lactic Acid) by Surface Entrapment Modification. Langmuir 2001, 17, 2817–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.; Kaduri, M.; Poley, M.; Adir, O.; Krinsky, N.; Shainsky-Roitman, J.; Schroeder, A. Biocompatibility, Biodegradation and Excretion of Polylactic Acid (PLA) in Medical Implants and Theranostic Systems. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 340, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestrelli, L.M.D.; Oyama, H.T.T.; Muñoz, P.A.R.; Cestari, I.A.; Fechine, G.J.M. Role of Graphene Oxide on the Mechanical Behaviour of Polycarbonate-Urethane/Graphene Oxide Composites. Materials Research 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viprya, P.; Kumar, D.; Kowshik, S. Study of Different Properties of Graphene Oxide (GO) and Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO). In Proceedings of the RAiSE-2023; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, December 20, 2023; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada, P.; Palza, H.; Palma, P.; Flores, M.; Caviedes, P. Poly(Lactic Acid) Composites Based on Graphene Oxide Particles with Antibacterial Behavior Enhanced by Electrical Stimulus and Biocompatibility. J Biomed Mater Res A 2018, 106, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, R.; Xue, S.; Zheng, B.; Shen, H.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, H. Graphene Oxide-Enhanced and Dynamically Crosslinked Bio-Elastomer for Poly(Lactic Acid) Modification. Molecules 2024, 29, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, K.; Roca, E.; Ramorino, G.; Sartore, L. Progress in the Mechanical Modulation of Cell Functions in Tissue Engineering. Biomater Sci 2020, 8, 7033–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, K.; Kumar, P.; Choonara, Y.E. The Paradigm of Stem Cell Secretome in Tissue Repair and Regeneration: Present and Future Perspectives. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2025, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.C.; King, A.; Björk, V.; English, B.W.; Fedintsev, A.; Ewald, C.Y. Strategic Outline of Interventions Targeting Extracellular Matrix for Promoting Healthy Longevity. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2023, 325, C90–C128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Ogino, R.; Yamakawa, S.; Suda, S.; Hayashida, K. Role and Function of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Fibroblast in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, R.; Rockel, J.S.; Kapoor, M.; Hinz, B. The Inflammatory Speech of Fibroblasts. Immunol Rev 2021, 302, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancarrow-Lei, R.; Mafi, P.; Mafi, R.; Khan, W. A Systemic Review of Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cell Sources and Their Multilineage Differentiation Potential Relevant to Musculoskeletal Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, M.; Kang, M.; Wu, X.; Chen, J.; Teng, L.; Qiu, L. Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Exosomes: Sources, Characteristics, and Application in Regenerative Medicine. Life Sci 2020, 256, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yang, J.; Fang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Candi, E.; Wang, J.; Hua, D.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y. The Secretion Profile of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Potential Applications in Treating Human Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Z.; Liao, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of Microenvironment and Biological Behavior on the Paracrine Function of Stem Cells. Genes Dis 2024, 11, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouwkema, J.; Khademhosseini, A. Vascularization and Angiogenesis in Tissue Engineering: Beyond Creating Static Networks. Trends Biotechnol 2016, 34, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; Jiang, Z.; Murfee, W.L.; Katz, A.J.; Siemann, D.; Huang, Y. Realizations of Vascularized Tissues: From in Vitro Platforms to in Vivo Grafts. Biophys Rev 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, D.; Wu, L.-P.; Zhao, M. Current Strategies for Engineered Vascular Grafts and Vascularized Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2023, 15, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummers, W.S.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J Am Chem Soc 1958, 80, 1339–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Silva, T.; Melo Soares, M.; Oliveira Carreira, A.C.; de Sá Schiavo Matias, G.; Coming Tegon, C.; Massi, M.; de Aguiar Oliveira, A.; da Silva Júnior, L.N.; Costa de Carvalho, H.J.; Doná Rodrigues Almeida, G.H.; et al. Biological Characterization of Polymeric Matrix and Graphene Oxide Biocomposites Filaments for Biomedical Implant Applications: A Preliminary Report. Polymers 2021, 13, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yan, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiang, H.; Qian, Y.; Fan, C. The Influence of Reduced Graphene Oxide on Stem Cells: A Perspective in Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Regen Biomater 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Shen, H.; Fang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, M.; Dai, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Z. Enhanced Proliferation and Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Graphene Oxide-Incorporated Electrospun Poly(Lactic- Co -Glycolic Acid) Nanofibrous Mats. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015, 7, 6331–6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Capasso, A.; Bonaccorso, F.; Kang, S.-H.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, G.-H. Electrically Conducting and Mechanically Strong Graphene–Polylactic Acid Composites for 3D Printing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11, 11841–11848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, L.; Pérez-Davila, S.; Lama, R.; López-Álvarez, M.; Serra, J.; Novoa, B.; Figueras, A.; González, P. 3D Printing of PLA:CaP:GO Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Applications. RSC Adv 2023, 13, 15947–15959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktay, B.; Ahlatcıoğlu Özerol, E.; Sahin, A.; Gunduz, O.; Ustundag, C.B. Production and Characterization of PLA/HA/GO Nanocomposite Scaffold. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.W.; Cox, A.; Mofarah, H.M.; Jabbour, G. Mechanical and Electrical Properties of 3D-Printed Highly Conductive Reduced Graphene Oxide/Polylactic Acid Composite. Adv Eng Mater 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Singh, J.; Singh, M.; Singh, G.; Parmar, A.S.; Chaudhary, S. Graphene Oxide/ Polylactic Acid Composites with Enhanced Electrical and Mechanical Properties for 3D-Printing Materials. J Mol Struct 2025, 1329, 141420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Bu, W.; Guo, F.; Li, J.; Wang, E.; Peng, Z.; Mai, H.; You, H.; et al. 3D Printed TPMS Structural PLA/GO Scaffold: Process Parameter Optimization, Porous Structure, Mechanical and Biological Properties. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2023, 142, 105848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altankov, G.; Grinnell, F.; Groth, T. Studies on the Biocompatibility of Materials: Fibroblast Reorganization of Substratum-Bound Fibronectin on Surfaces Varying in Wettability. J Biomed Mater Res 1996, 30, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.M.; Moreira, S.; Gonçalves, I.C.; Gama, F.M.; Mendes, A.M.; Magalhães, F.D. Biocompatibility of Poly(Lactic Acid) with Incorporated Graphene-Based Materials. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2013, 104, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausgruber, T.; Fortelny, N.; Fife-Gernedl, V.; Senekowitsch, M.; Schuster, L.C.; Lercher, A.; Nemc, A.; Schmidl, C.; Rendeiro, A.F.; Bergthaler, A.; et al. Structural Cells Are Key Regulators of Organ-Specific Immune Responses. Nature 2020, 583, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laraba, S.R.; Ullah, N.; Bouamer, A.; Ullah, A.; Aziz, T.; Luo, W.; Djerir, W.; Zahra, Q. ul A.; Rezzoug, A.; Wei, J.; et al. Enhancing Structural and Thermal Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid) Using Graphene Oxide Filler and Anionic Surfactant Treatment. Molecules 2023, 28, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Lin, X.; Zou, L.; Fu, W.; Lv, H. Effect of Graphene Oxide/ Poly-L-Lactic Acid Composite Scaffold on the Biological Properties of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Li, K.; Guo, W.; Zhao, G.; Fu, C. Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid)/Graphene Oxide Composites Combined with Electrical Stimulation in Wound Healing: Preparation and Characterization. Int J Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 7039–7052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennigs, J.K.; Matuszcak, C.; Trepel, M.; Körbelin, J. Vascular Endothelial Cells: Heterogeneity and Targeting Approaches. Cells 2021, 10, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, X.; Fan, J.; Qiao, J.; Mao, F. Cell–Cell Communication: New Insights and Clinical Implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaksono, H.; Annisa, A.; Ruslami, R.; Mufeeduzzaman, M.; Panatarani, C.; Hermawan, W.; Ekawardhani, S.; Joni, I.M. Recent Advances in Graphene Oxide-Based on Organoid Culture as Disease Model and Cell Behavior – A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 6201–6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, T. How the Mechanical Microenvironment of Stem Cell Growth Affects Their Differentiation: A Review. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouAitah, K.; Sabbagh, F.; Kim, B.S. Graphene Oxide Nanostructures as Nanoplatforms for Delivering Natural Therapeutic Agents: Applications in Cancer Treatment, Bacterial Infections, and Bone Regeneration Medicine. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway: From Bench to Clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, C.; Ying, M.; Zhang, M.; Lu, L.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; et al. Liposomes with Cyclic RGD Peptide Motif Triggers Acute Immune Response in Mice. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 293, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Zong, X.; Sun, Q.; Lin, Y.-C.; Song, Y.J.; Hashemikhabir, S.; Hsu, R.Y.; Kamran, M.; Chaudhary, R.; Tripathi, V.; et al. The S-Phase-Induced LncRNA SUNO1 Promotes Cell Proliferation by Controlling YAP1/Hippo Signaling Pathway. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Brink, T.; Damanik, F.; Rotmans, J.I.; Moroni, L. Unraveling and Harnessing the Immune Response at the Cell–Biomaterial Interface for Tissue Engineering Purposes. Adv Healthc Mater 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, X.; Feng, B.; Liang, C.; Wan, X.; El-Newehy, M.; Abdulhameed, M.M.; Mo, X.; Wu, J. Fiber Configuration Determines Foreign Body Response of Electrospun Scaffolds: In Vitro and in Vivo Assessments. Biomedical Materials 2024, 19, 025007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, K.; Pan, Z.; Guan, E.; Ge, S.; Liu, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Ren, X.-D.; Rafailovich, M.; Clark, R.A.F. Cell Adaptation to a Physiologically Relevant ECM Mimic with Different Viscoelastic Properties. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudaryeva, O.Y.; Bernhard, S.; Tibbitt, M.W.; Labouesse, C. Implications of Cellular Mechanical Memory in Bioengineering. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2023, 9, 5985–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavkin, N.W.; Genet, G.; Poulet, M.; Jeffery, E.D.; Marziano, C.; Genet, N.; Vasavada, H.; Nelson, E.A.; Acharya, B.R.; Kour, A.; et al. Endothelial Cell Cycle State Determines Propensity for Arterial-Venous Fate. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.J.; Lee, J.H. Exploring the Molecular and Developmental Dynamics of Endothelial Cell Differentiation. Int J Stem Cells 2024, 17, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikiaris, N.D.; Koumentakou, I.; Samiotaki, C.; Meimaroglou, D.; Varytimidou, D.; Karatza, A.; Kalantzis, Z.; Roussou, M.; Bikiaris, R.D.; Papageorgiou, G.Z. Recent Advances in the Investigation of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) Nanocomposites: Incorporation of Various Nanofillers and Their Properties and Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Aguirre, E.; Iñiguez-Franco, F.; Samsudin, H.; Fang, X.; Auras, R. Poly(Lactic Acid)—Mass Production, Processing, Industrial Applications, and End of Life. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016, 107, 333–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.A.; Lee, S.J.; Seok, J.M.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, W.D.; Kwon, I.K. Fabrication of 3D Printed PCL/PEG Polyblend Scaffold Using Rapid Prototyping System for Bone Tissue Engineering Application. J Bionic Eng 2018, 15, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemons, J.M.S.; Feng, X.-J.; Bennett, B.D.; Legesse-Miller, A.; Johnson, E.L.; Raitman, I.; Pollina, E.A.; Rabitz, H.A.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Coller, H.A. Quiescent Fibroblasts Exhibit High Metabolic Activity. PLoS Biol 2010, 8, e1000514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg Effect: The Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Science (1979) 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.R.A.; Marques, C.S.; Arruda, T.R.; Teixeira, S.C.; de Oliveira, T.V. Biodegradation of Polymers: Stages, Measurement, Standards and Prospects. Macromol 2023, 3, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kürten, C.; Carlberg, B.; Syrén, P.-O. Mechanism-Guided Discovery of an Esterase Scaffold with Promiscuous Amidase Activity. Catalysts 2016, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa, Y.; Suzuki, T. Hydrolysis of Polyesters by Lipases. Nature 1977, 270, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvetsova, E.V.; Rogovaya, O.S.; Tkachenko, S.B.; Kiselev, I.V.; Vasil’ev, A.V.; Terskikh, V.V. Contractile Capacity of Fibroblasts from Different Sources in the Model of Living Skin Equivalent. Biology Bulletin 2008, 35, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganuma, T. The Relationship between Cell Adhesion Force Activation on Nano/Micro-Topographical Surfaces and Temporal Dependence of Cell Morphology. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 13171–13186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cun, X.; Hosta-Rigau, L. Topography: A Biophysical Approach to Direct the Fate of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Tissue Engineering Applications. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlender, B.; Windolf, J.; Suschek, C.V. Superoxide Dismutase and Catalase Significantly Improve the Osteogenic Differentiation Potential of Osteogenetically Compromised Human Adipose Tissue-Derived Stromal Cells in Vitro. Stem Cell Res 2022, 60, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Tang, M. Toxicity Mechanism of Engineered Nanomaterials: Focus on Mitochondria. Environmental Pollution 2024, 343, 123231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, R.L.; Agans, R.; Huddleston, M.E.; Snyder, A.; Mendlein, A.; Hussain, S. Toxicological Mechanisms of Engineered Nanomaterials: Role of Material Properties in Inducing Different Biological Responses. In Handbook of Developmental Neurotoxicology; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 237–249.

- Herzig, S.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Guardian of Metabolism and Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Health and Disease: Mechanisms and Potential Targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sampath, H. Mitochondrial DNA Integrity: Role in Health and Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaurrea, A.; Araujo, A.M.; Caffarel, M.M. The Role of the IL-6 Cytokine Family in Epithelial–Mesenchymal Plasticity in Cancer Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque-Campos, N.; Bustamante-Barrientos, F.A.; Pradenas, C.; García, C.; Araya, M.J.; Bohaud, C.; Contreras-López, R.; Elizondo-Vega, R.; Djouad, F.; Luz-Crawford, P.; et al. The Macrophage Response Is Driven by Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Mediated Metabolic Reprogramming. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lategan, K.; Alghadi, H.; Bayati, M.; De Cortalezzi, M.; Pool, E. Effects of Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles on the Immune System Biomarkers Produced by RAW 264.7 and Human Whole Blood Cell Cultures. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md.M.; Shahruzzaman, Md.; Biswas, S.; Nurus Sakib, Md.; Rashid, T.U. Chitosan Based Bioactive Materials in Tissue Engineering Applications-A Review. Bioact Mater 2020, 5, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell cycle (phase) | FN1 vs. control (%) |

mBMSCs vs. control (%) |

HUVEC vs. control (%) |

| Debris | ↑ (34.38 vs. 5.93; p=0.03) | ↑ (34.73 vs. 5.40; p=0.005) | ↔ (2.8 vs. 3.8; p=0,34) |

| G0/G1 | ↑ (71.74 vs. 15.27; p=0.02) | ↑ (61.89 vs. 39.98; p=0.039) | ↔ (54.26 vs. 61.93; p=0.13) |

| S | ↓ (21.58 vs. 81.50; p=0.005) | ↓ (29.16 vs. 54.82; p=0.017) | ↔ (45.74vs. 37.99; p=0.13) |

| G2/M | ↔ (5.93 vs. 3.23; p=0.28) | ↔ (8.96 vs. 5.21; p=0.12) | ↔ (0 vs. 0.09; p=0.08) |

| Generations | FN1 vs. control (pg/mL) | mBMSCs vs. control (pg/mL) | HUVEC vs. control (pg/mL) |

| 2 | ↔ (48.30 vs. 48.01; p=0.89) | ↑(46.26 vs. 43.95; p=0.003); Δ+4.99% | ↓(7.8 vs. 9.24; p=0.0005); Δ-18.46% |

| 3 | ↔ (31.88 vs. 31.28; p=0.61) | ↔ (34.03 vs. 36.34; p=0.34) |

↔ (9.89 vs. 9.41; p=0.16) |

| 4 | ↔ (19.83 vs. 20.72; p=0.42) | ↔ (19.71 vs. 20.21; p=0.72) | ↑(16.53 vs. 8.61; p=0.005); Δ+ 47.91% |

| 5 | N.A | N.A | ↓(20.28 vs. 47.87; p=0.003); Δ-136.05% |

| 6 | N.A | N.A | ↔ (35.13 vs. 32.05; p=0.95) |

| 7 | N.A | N.A | N.D. |

| 8 | N.A | N.A | ↔ (0.61 vs. 0.75; p=0.65) |

| 9 | N.A | N.A | ↔ (1.33 vs. 0.62; p=0.23) |

| 10 | N.A | N.A | ↓(19.83 vs. 20.72; p<0.0001);Δ- 4.49% |

| ΔΨ | FN1 vs. control (%) | mBMSCs vs. control (%) | HUVEC vs. control (%) |

| Active cells | ↔ (88.58 vs. 90.76) | ↔ (91.6 vs. 93.03) | ↓ (65.82 vs. 97.07); Δ-32.19% |

| Inactive cells | ↔ (11.56 vs. 9.32) | ↔ (8.42 vs. 7.03) | ↑ (34.24 vs. 3.04); Δ+1026.32% |

| Citokines | FN1 vs. control (pg/mL) | mBMSCs vs. control (pg/mL) | HUVEC vs. control (pg/mL) |

| IL-12p70 | ↔ (73.14 vs. 76.33; p=0.68) | ↔ (150.52 vs. 165.43; p=0.39) | ↔ (73.13 vs. 76.33; p=0.68) |

| TNF-α | ↔ (89.11 vs. 97.63; p=0.052 ) | ↑(179.67vs. 147.68; p=0.03); Δ+21.66% | ↓ (89.11 vs. 97.63; p=0.05); Δ- 8.73% |

| IL-10 | ↔ (96.21 vs. 99.75; p=0.39) | ↔ (221.52 vs. 224.36; p=0.71) | ↔ (96.21 vs. 99.76; p=0.39) |

| IL-6 | ↓(114.67 vs. 130.10; p=0.019); Δ-1.86% | ↔ (402.57 vs. 388.37; p=0.62) | ↓(114.67vs. 131.00;p=0.02); Δ-12.47% |

| IL-8 | ↔ (150.00 vs. 155.20; p=0.42) | ↔ (185.20 vs. 190.50; p=0.55) | ↔ (165.00 vs. 170.10; p=0.38) |

| 1L-1β | ↔ (301.40 vs. 319.25; p=0.34) | ↔ (330.10 vs. 335.70; p=0.60) | ↔ (310.00 vs. 315.30; p=0.47) |

| IFN- γ | ↔ (155.00 vs. 158.50; p=0.68) | ↔ (157.62 vs. 164.72; p=0.1) | ↔ (148.70 vs. 150.10; p=0.82) |

| MCP-1 | ↔ (7.500 vs. 7.700; p=0.52) | ↔ (8.675. vs. 8.076; p=0.23) | ↔ (7.050 vs. 7.200; p=0.70) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).