1. Introduction

Regenerative medicine aims to replace or restore damaged, malfunctioning, or missing tissues or body systems by using biological substitutes to repair and maintain physiological function. Recent interest in the use of graphene-based nanomaterials for biomedical devices has led to numerous exciting reports in the literature over the past few years [

1,

2,

3] These reports indicate that graphene-based materials are promising nanomaterials for the adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of various cell types, including Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) [

4]. Since the cell cycle plays a crucial role in cell growth, division, and viability, and is one of the most critical events in mammalian cells, increasing our understanding of how graphene properties can modulate cell cycle patterns is essential for designing advanced biomedical applications.

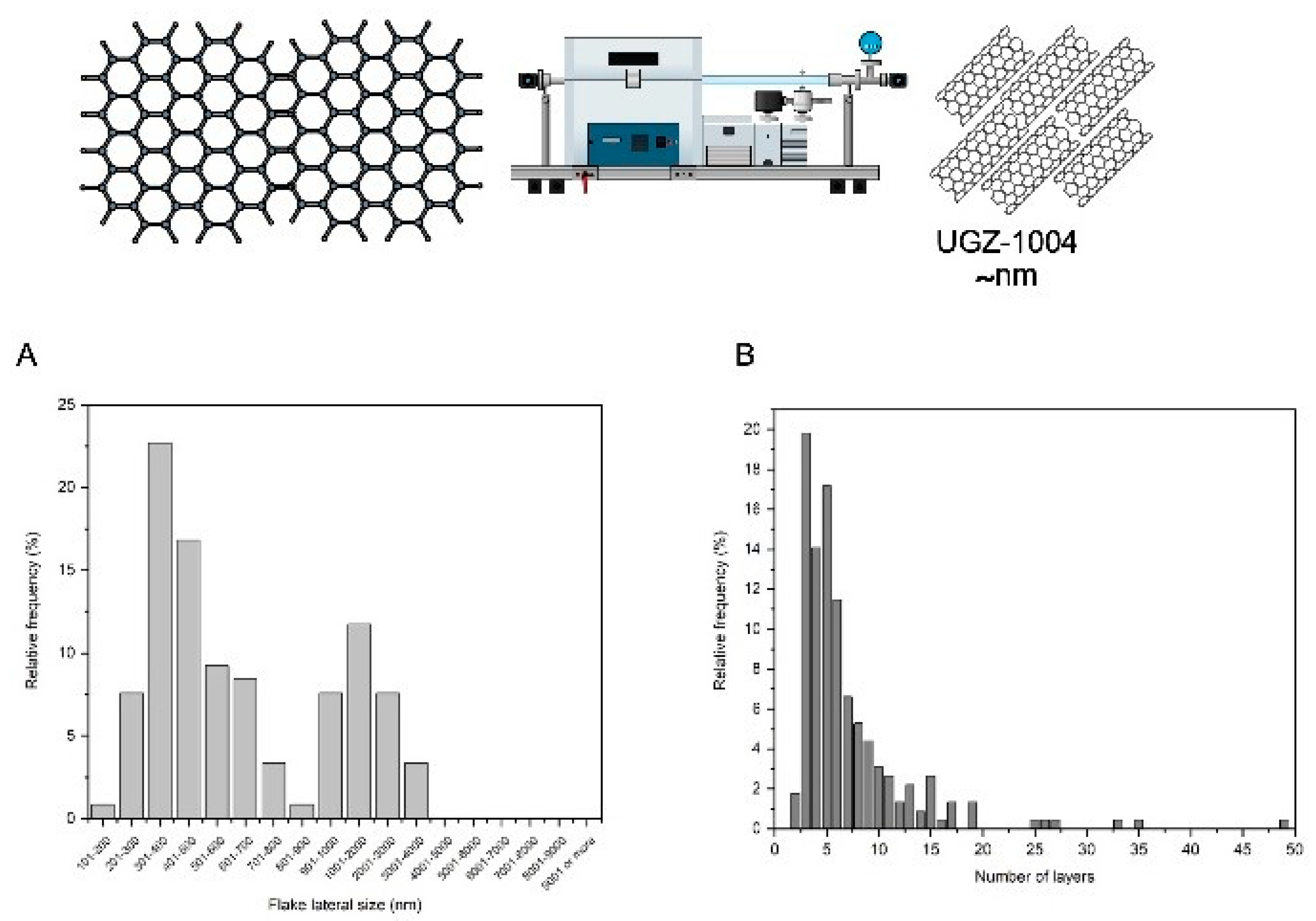

Graphene is considered a disruptive technology due to its exceptional properties. This material is primarily composed of carbon, similar to graphite, but it exhibits unique characteristics such as lightness, strength, and electrical conductivity. Graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a two-dimensional planar sheet with a hexagonal lattice pattern, measuring less than 100 nm in nanoscale dimensions. These remarkable properties have captured the attention of the biomedical sciences. Graphene-based materials can be classified according to the number and spatial arrangement of sheets, oxygen content, and chemical modification. According to ISO/TS 80004-13:2017, the following terms are used for different structures derived from graphene: two-layer graphene (2LG) refers to bilayer graphene, and few-layer graphene (FLG) consists of 3 to 10 graphene layers. Derivatives of graphene include graphene nanoplatelets (GNP), graphene oxide (GO), and reduced graphene oxide (rGO). Graphene nanoplatelets, or nanoplates (NPG), are one of the commercially available graphene derivatives. They consist of graphene sheets that form aggregated plates, with a thickness of a few nanometers and lateral sizes ranging from 100 nm to 100 µm. GO and rGO are more frequently used in biomedical applications due to their distinct chemical properties and versatility [

5].

The discovery of a cutting-edge world in the biocompatibility of graphene and its limitless possibilities makes it an attractive biomaterial, shedding new light on tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Specific graphene-based nanomaterials have been shown to be compatible with human osteoblasts [

6], murine fibroblasts [

7], and mammalian adenocarcinoma cells [

8]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that graphene and its derivatives play a crucial role in enhancing the proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [

6], mimicking the properties of the cells physiological microenvironment. Cells grown in the presence of graphene exhibit improved growth, proliferation, and differentiation, although further research is needed to optimize cell viability.

Controlling cell fate has become one of the most critical topics in regenerative tissue engineering and medicine. Biomaterials that can interact with the intracellular environment of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are central to this endeavor. Understanding these interactions is crucial for controlling the numerous factors that affect cell stimuli and behavior, and for translating these into the restoration of cellular and tissue functions. Therefore, this research proposes the synthesis and optimization of MSC therapy boosted by graphene nanoplatelets as a promising candidate for development into a bioactive and compatible cell product for advanced cellular therapy. Key points to be considered include cell viability and proliferation profiles, cell-cycle checkpoints, and DNA repair mechanisms in graphene-exposed cells.

2. Materials and Methods

Graphene Nanoplatelets

The graphene nanoplatelets used in this study were produced using the liquid-phase exfoliation method. This method is characterized by its ability to produce colloidal graphene suspensions from graphite and is considered the most promising route for large-scale production [

9]. This method separates graphite layers with hexagonal structures using a liquid chemical. Graphite is composed of multiple graphene layers stacked on top of each other, with weak π-π bonds between these layers. The liquid medium facilitates the breaking of these bonds, allowing the graphene layers to separate. An external force is required for the molecules of the liquid medium to penetrate between the layers and break the π-π bonds [

10].

The graphene nanoplatelets were characterized using atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to determine their thickness and lateral size, respectively. AFM measurements were performed using a Shimadzu® SPM-9700HT microscope (Japan) following the ABNT ISO/TS 21356-1 standard. SEM analyses were conducted with a Tescan MIRA3 (Czech Republic), also adhering to the ABNT ISO/TS 21356-1 standard procedures. To characterize the chemical composition of the graphene nanoplatelets, a carbon purity analysis was conducted according to the ISO 11308 standard (Nanotechnologies: Characterization of single-wall carbon nanotubes using thermogravimetric analysis). This analysis was performed on a Netzsch STA 449 F3 Jupiter® thermogravimetric balance, under airflow (100 mL/min), from room temperature to 1000 ºC, with a heating rate of 5 ºC/min. The crucible used was made of alumina. The ISO 11308 standard correlates the purity content with the residual mass contained in the crucible at the end of the analysis.

General Cell Culture Protocols

VERO (African green monkey kidney epithelial cells), 3T3 (murine fibroblast), and BV-2 (murine microglia) cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, Maryland, USA). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at a temperature of 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were obtained from equine bone marrow progenitor cells and cultured in a tissue culture flask with a growth area of 75 cm² in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin (50 U/mL and 50 µg/mL, respectively; Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) until reaching 80% confluence. The cells were then passaged to passage 5. The plates were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48 hours. To exchange the medium, the plates were washed with PBS to remove non-adherent cells, and the medium was subsequently replaced.

All cell lines were pre-seeded at 3-5 x 10³ cells per well in 96-well plates or 15-20 x 10³ cells in 24-well plates, depending on the experimental protocol. Prior to experimentation, the graphene nanoplatelet biomaterial, referred to as UGZ-1004, was exposed to UV light for 30 minutes on each side in a Class II safety cabinet as part of the decontamination protocol.

VERO, 3T3, BV-2, and MSC cells were exposed to UGZ-1004 using both direct contact and elution methods at a concentration of 6 cm²/mL, in accordance with ISO 10993 (2020/2023) standards for the biological evaluation of sterile medical devices in contact with the human body. The MTT and DAPI assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times, as recommended by ISO 10993 (2020/2023).

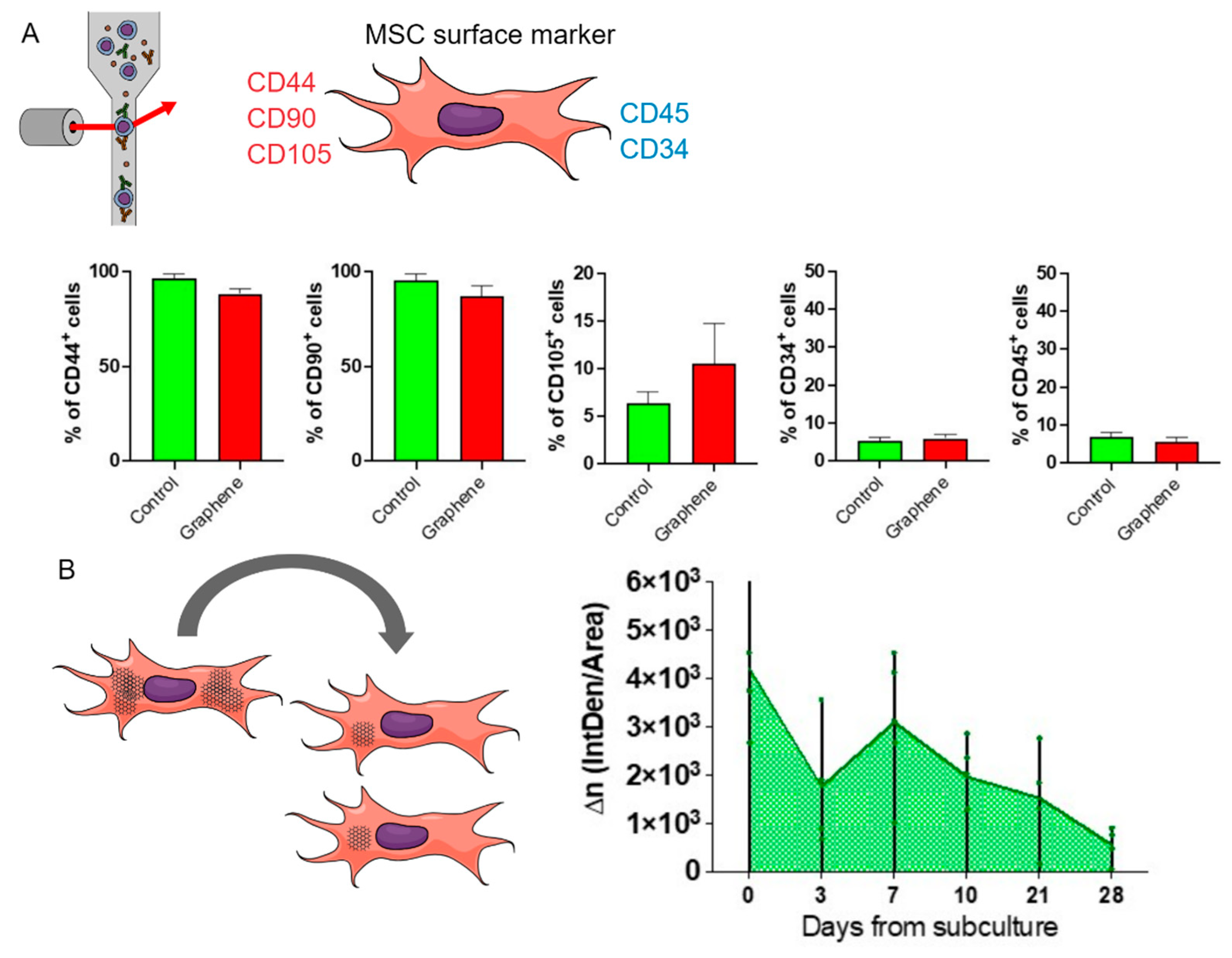

MSCs Characterization by Flow Cytometry

For the characterization of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the surface markers recommended as minimum characterization criteria by the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) were used. MSCs at passage 5 were characterized both before and after exposure to graphene. To detect surface antigens, MSCs were incubated with antibodies against CD44, CD90, CD105, CD45, and CD34. After labeling, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto cytometer (BD - Becton, Dickinson and Company, New Jersey, USA).

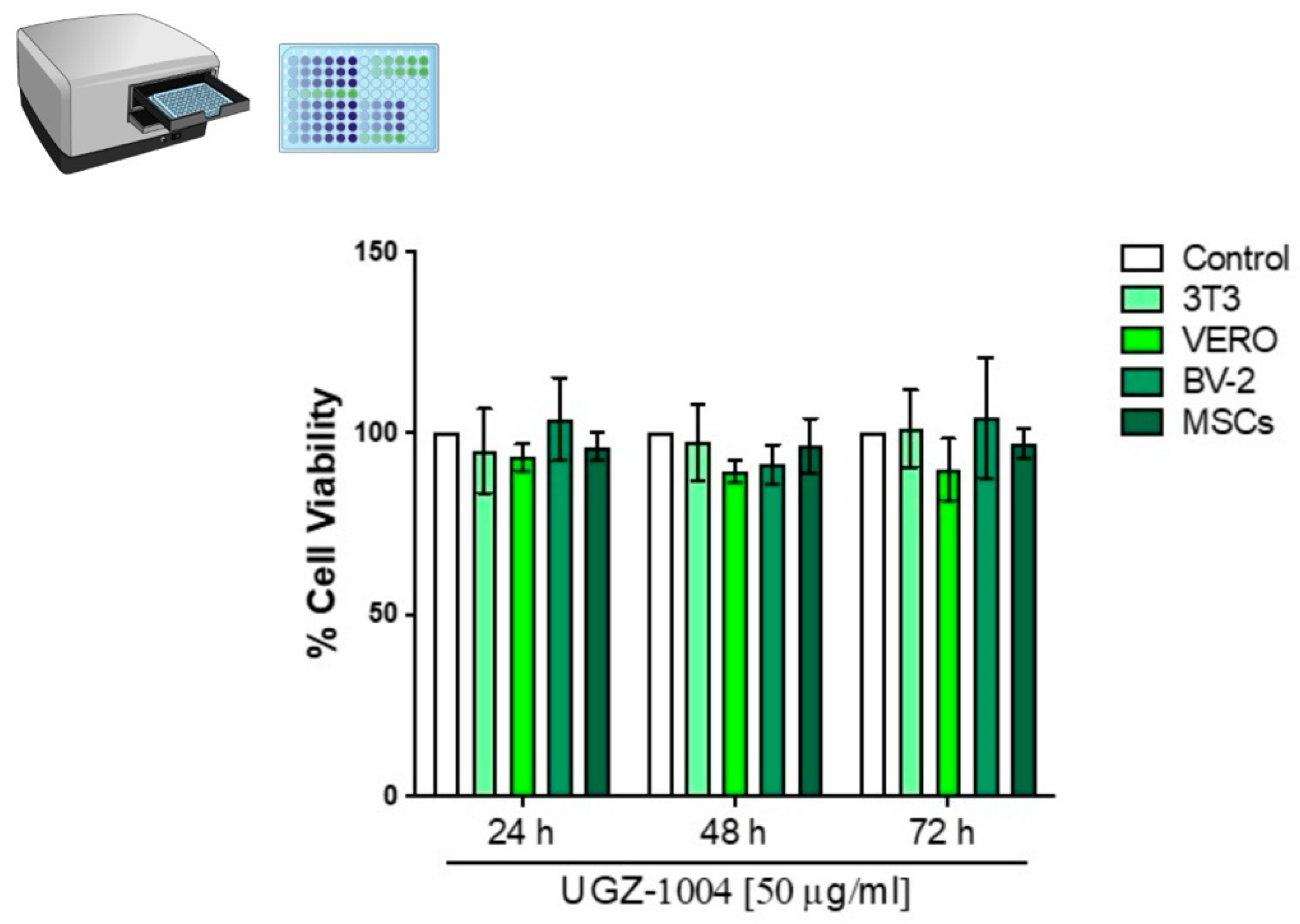

Cytotoxic Potential by MTT

Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay to measure the production of formazan [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium] bromide (Sigma Aldrich, Missouri, USA). Following exposure to UGZ-1004 (24, 48, and 72 hours), 3T3, VERO, BV-2, and MSC cells were incubated with a 0.5 mg/mL MTT solution diluted in PBS (pH 7.4) for three hours at 37°C, protected from light. After incubation, the cells were exposed to 300 µL/well of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) to solubilize the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a Bio-Rad spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, California, USA). Absorbance values were converted into percentages using the formula:

The experiments were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test with GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA). Results are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance compared to the control group.

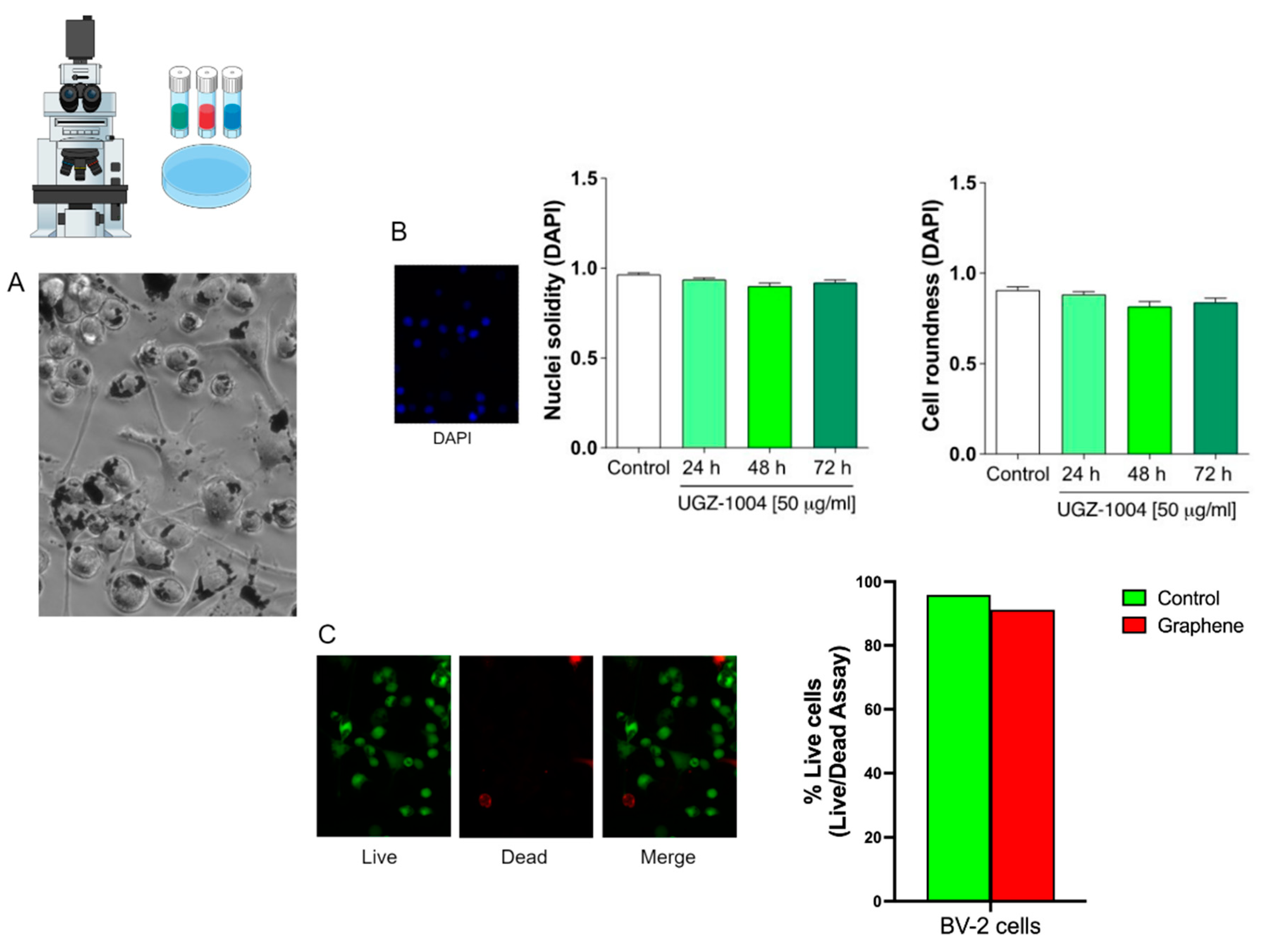

Nuclear Analyses by DAPI

The 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining provides nuclear morphological features (area, roundness, and solidity) and is related to several mechanisms that affect cell survival processes. DAPI staining was used to assess nuclear morphology and establish cell proliferation rates in BV-2 cell lines. Following exposure to UGZ-1004 (24, 48, and 72 hours), cells were washed three times in 1% PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 minutes. The fixed cells were then washed again with 1% PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1% PBS, and stained with a 300 nM DAPI solution (Santa Cruz, CA) at room temperature for 10 minutes.

Nuclear morphology was examined under a fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Germany). DAPI staining delineates the nuclear morphology, allowing quantification of nuclear roundness and solidity using ImageJ Software, with ten fields analyzed per sample. Data from control cells (not exposed to UGZ-1004) were used to set baseline parameters. The experiments were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test using GraphPad Software. Results are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Live/Dead Cells Trial

The LIVE/DEAD Cell Viability Assay kit (Abbikine, China, cat number #KTA1001) was employed to identify and quantify dead cells in mammalian cell types exposed to UGZ-1004 for 48 hours. BV-2 cells were incubated for cell labeling, following the manufacturer’s specifications. In this assay, we load cells with Calcein-AM plus propidium iodide (PI), which penetrate the live (green fluorophore) and dead cells (red fluorophore), respectively, and count red/green fluorescent cells. Then, the cell types were placed back into the incubator for 30 min to allow permeation of Calcein-AM and PI. Acquisition images were taken immediately in each group's four regions of gray matter, three times in triplicate. The image and data analyses were performed using an inverted microscope setup for fluorescence microscopy AXIOVERTII (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Germany) and its respective Zen Blue software.

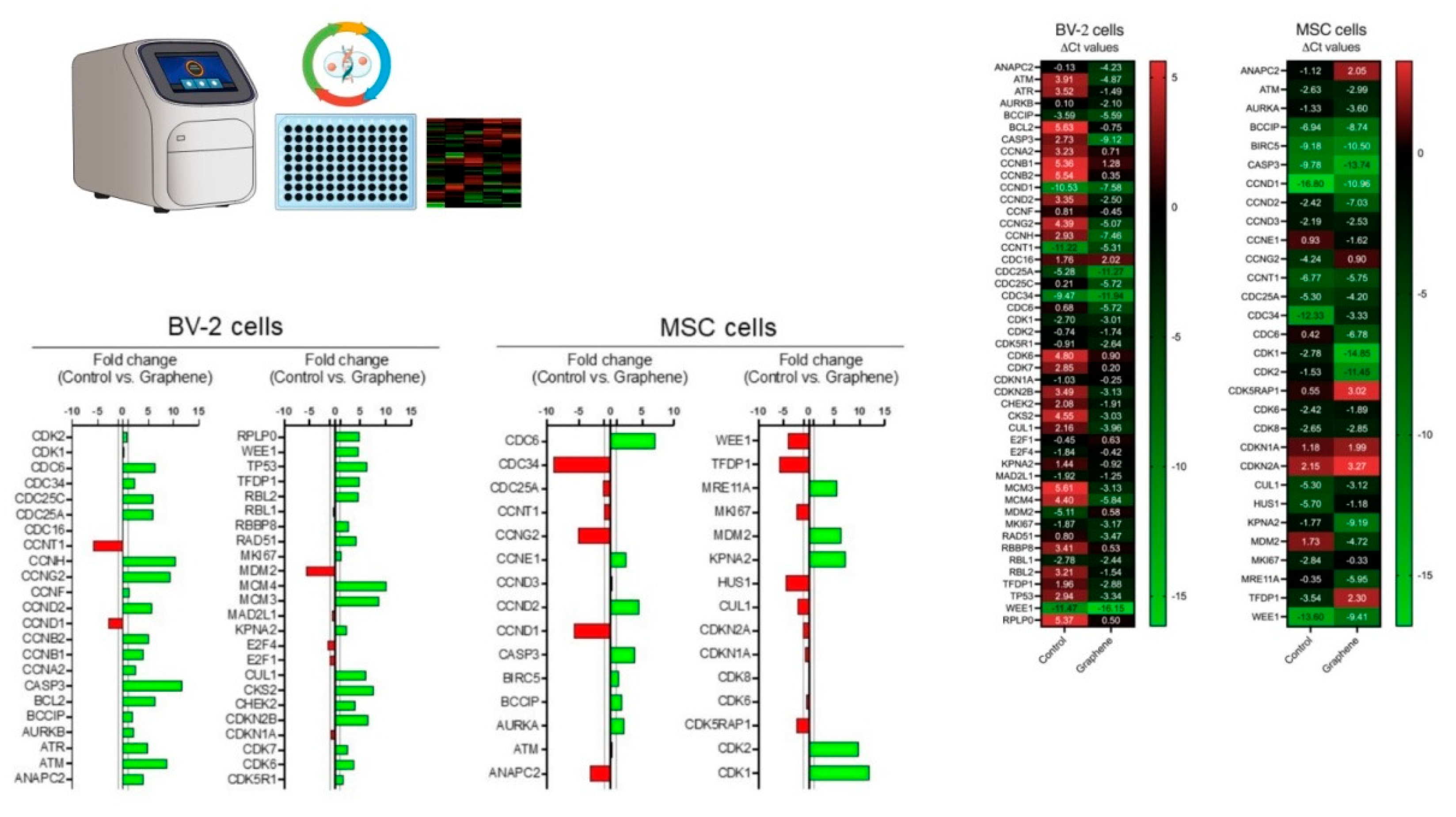

Real-Time qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted from MSC and BV-2 cells after 48 hours of exposure to UGZ-1004 using the SV-Total RNA Isolation System kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were lysed with a lysis buffer, heated to 70°C for 3 minutes, and then centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and 200 µL of 95% ethyl alcohol was added. The mixture was transferred to a spin column and centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 1 minute. The RNA was eluted from the columns with 100 µL of RNase-free water by centrifugation at 12,000 x g for 2 minutes.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed using the GoScript Reverse Transcriptase kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. The generated cDNA was used for the RT² Profiler™ PCR Array Human Cell Cycle (SuperArray Bioscience Corporation, Maryland, USA), which contains 92 primers complementary to gene regions related to the cell cycle, as well as four endogenous gene controls.

Population Doubling Level - PDL

For the population growth assays, BV-2 cells were exposed to UGZ-1004 graphene nanoplatelets and cultured until reaching approximately 70% confluence. After plating, the cells were cultured at intervals of 3, 7, 10, 21, and 28 days, with 70% confluence serving as the criterion for trypsinization. At each trypsinization, half of the trypsinized cell density was inoculated into new wells with fresh medium.

The Population Doubling Level (PDL) was calculated using ImageJ Software. Since graphene nanoplatelets appear gray under light microscopy, they facilitated the analysis of UGZ-1004 retention and depletion over the cultivation period. Digitized RGB (24-bit) images were transferred to a computer and analyzed using a custom macro designed to quantify the positive areas based on pixel color, which enabled the recognition and tracking of graphene until its maximum elimination from the culture. This macro was applied to all images obtained from the experimental design, and results were recorded in terms of optical density.

4. Discussion

Despite the enthusiasm surrounding the extensive use of nanotechnology-based materials in regenerative medicine, the advent of graphene has introduced a unique class of biomaterials with significant potential for medical applications. Given the relatively recent discovery of graphene, it is crucial to thoroughly elucidate the toxicological profiles of graphene nanoplatelets. This scrutiny is essential for ensuring the safety and efficacy of future translational studies.

Graphene-based materials, including pristine graphene sheets, few-layer graphene flakes, and graphene oxide (GO), offer a range of unique, versatile, and tunable properties that can be creatively applied in biomedical fields. For example, graphene can be functionalized with various chemical groups such as carboxyl, amine, epoxy, and hydroxyl groups, which serve as anchoring points for specific biomolecules.

Designing graphene materials for biomedical applications requires a comprehensive understanding of their properties and functionalization strategies to optimize their capabilities and biocompatibility. The diverse functionalization methods available enable the tailoring of graphene's properties to meet specific needs, thereby enhancing its effectiveness in various biomedical applications. To improve dispersion and stability, prolong circulation, and reduce cytotoxicity, functionalization techniques often involve both noncovalent and covalent methods. Noncovalent approaches may include the use of hydrophilic polymers or surfactants, while covalent modifications often involve carboxylic acids and other functional groups. These strategies help to enhance the solubility of graphene materials in biological environments and ensure their safe and effective use in medical applications [

11]. Further functionalization with proteins, DNA, metal nanoparticles, and other biomolecules can enhance the specificity and efficiency of graphene materials for targeted biomedical applications. These advanced modifications allow for the precise targeting of specific biological interactions, thereby improving the performance and efficacy of graphene-based materials in diverse medical contexts.

The primary objective was to evaluate the expression of genes involved in the proliferation and renewal of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) following treatment with non-toxic graphene nanoplatelets. To achieve this, we assessed the biocompatibility of UGZ-1004, a graphene nanoplatelet biomaterial, in contact with mammalian cells, including MSCs. In vitro procedures were employed to determine the cytocompatibility of UGZ-1004, focusing on toxicity, cell viability, and proliferation. Recent investigations have highlighted that the cytotoxicity of graphene and its derivatives is influenced by various factors, such as shape, size, dispersibility, and surface functionalization. Standard measures for evaluating the cytotoxicity of carbon-based nanomaterials include assessing oxidative stress and cell membrane damage [

12,

13]. In the literature, cytotoxicity has been reported in HepG2 cells when treated with GO and rGO and determined an EC50 of 50 µg mL−1 [

14], a concentration in the range of those used in our work. Interestingly, The presence of graphene has been shown to enhance cytoplasmic reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in human macrophages. However, different responses have been observed when comparing human and murine macrophages following treatment with graphene [

15,

16].

Graphene nanoplatelets with varying lateral sizes have increasingly been employed to enhance the growth and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). As the applications of MSCs and research into pristine graphene have expanded, studies have also reported on the cytotoxicity of these materials. For example, graphene oxide (GO) exhibited concentration-dependent cytotoxicity to human MSCs (hMSCs). At a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL, GO did not show any signs of cytotoxicity. However, at concentrations exceeding 0.1 mg/mL, GO was found to be cytotoxic to hMSCs [

17,

18]. Higher oxidative stress and cell membrane damage have been associated with the concentration, shape, and lateral size of graphene-based nanomaterials, as well as their exposure time to MSCs. For instance, after a short exposure time to a low concentration of 1.0 mg/mL, small reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanoplatelets induced substantial destruction of human MSCs (hMSCs). Conversely, the cytotoxicity of larger graphene sheets, which was shape-dependent, became evident only at high concentrations (100 mg/mL) and after prolonged exposure periods [

19].

The biocompatibility of graphene nanoplatelet biomaterials is crucial for understanding their potential impact on macrophage phagocytic activity. Our second key finding pertains to BV-2 microglia, which, due to their inherent phagocytic activity, can significantly interact with exogenous particles, including graphene nanoplatelets, thereby altering their functional responses. Our results are consistent with a recent study that investigated the in vitro interactions between blended graphene nanosheets (approximately 8 to 9 nm in size) and MSCs derived from mouse bone marrow [

20]. Interestingly, the blended biomaterial was effectively taken up by MSCs, accumulating in the cytoplasm without entering the nucleus. Notably, these nanomaterials were not cytotoxic and did not impair the proliferation, differentiation potential, or other cellular functions of MSCs. Only a few studies in the literature have focused on understanding the mechanisms of graphene-based nanomaterial uptake by cells. The primary pathway identified involves the internalization of graphene with lateral dimensions ranging from 100 nm to 1 µm, predominantly through micropinocytosis. The graphene internalized via macropinocytosis was consistent with Linares et al [

22] and Chen et al [

19] who found macropinocytosis to be an uptake mechanism for GO uptake with the lateral dimension of 100 nm in the human liver cancer cell and human bone cancer cell.

Finally, it has been noted that graphene nanosheets with dimensions of hundreds of micrometers can induce concentration-dependent cytotoxicity due to their hydrophobic interactions with the mammalian cell plasma membrane [

19,

23]. Regarding this point, it is crucial to monitor the accumulation of graphene nanosheets on the cellular plasma membrane, as this can disrupt intracellular balance, including the redox equilibrium, potentially leading to programmed cell death. Following exposure to graphene, MSCs exhibited upregulation of genes such as CDK1, CDK2, KPNA2, CDC6, MDM2, and MRE11A. Notably, CDK1, CDK2, and MRE11A are key regulators of cell proliferation. CDK1 and CDK2, members of the Cdk family, are essential for regulating the transition between the G2 phase and mitosis. CDK1, in particular, is closely involved in several critical cellular events essential for cell survival [

24]. Numerous strategies have been employed to modify the modulation of cellular plasticity profiles. For instance, Marinowic et al. investigated the effects of co-culturing skin fibroblasts with a mononuclear fraction of umbilical cord blood, both directly and indirectly. This exposure led to a reduction in the expression of harmful cell cycle control genes in the fibroblasts, which was attributed to an enhancement in the plasticity of these cells through induction. Such findings are highly significant, especially considering the potential application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in treating human pathologies [

25].

Low doses of radiation (75 mGy for 24 hours) modulated the proliferative capacity of MSCs by regulating CDK1. This radiation stimulated proliferation and increased the S-phase proportion of MSCs [

26]. In an attempt to increase the proliferative capacity of MSCs, controlled exposure to different concentrations of zinc also increased the expression of CDK genes, associating these findings with improved adhesion, migration, and self-renewal capabilities of MSCs [

27].

The potential increase in cell proliferation and self-renewal observed in MSCs exposed to graphene can be further supported by the elevated expression of the MDM2 gene. MDM2 encodes an oncoprotein that inhibits p53-mediated transcriptional activation [

28]. Thus, after exposure to graphene, MSCs encounter direct and indirect proliferative stimuli by inhibiting cell cycle suppressors.

This increase in cell proliferation is accompanied by elevated expression of the CDC6 and MRE11A genes. This is a significant finding because both genes play crucial roles in maintaining DNA integrity. CDC6 is involved in regulating the initiation of DNA replication, while MRE11A is essential for effective DNA repair and ensuring that replication is completed before mitosis begins [

29,

30].

The positive fold change in genes associated with increased cell proliferation, as well as checkpoint and DNA repair genes, suggests that the exposure of mesenchymal cells to graphene can safely enhance their proliferative capacity. This enhancement appears to preserve crucial mechanisms that prevent DNA alterations during the transition from the S phase to G1 phase.

Some genes exhibited a negative fold change after exposure to graphene, including CCNG2, CCND1, TFDP1, and CDC34. Notably, CCND1 and TFDP1 are genes whose overexpression is linked to the development of various types of tumors [

31,

32]. MSCs exposed to graphene showed downregulation of these genes, which is a significant finding in the context of tumor inhibition. Increased expression of TFDP1 has been notably associated with the enlargement of hepatocellular carcinoma, and its downregulation has been found to inhibit the growth of Hep3B cells. This suggests that TFDP1 overexpression can contribute to tumor cell progression and growth [

32].

BV-2 cells are microglial cells derived from C57/BL6 mice. Microglia are resident immune cells in the central nervous system that are crucial in regulating neural activity, synaptic plasticity, and neuroinflammation [

33].

There was an 11.84-fold increase in the expression of the CASP3 gene, which plays a crucial role in neuronal apoptosis. Caspase-3 is a key mediator of the apoptosis process and can be activated through both extrinsic (death ligands) and intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways. The hyperactivation of caspase-3 and the subsequent increase in cell death may be associated with the development of neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington's disease (HD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD). While exposure of BV2 cells to graphene did not result in a cytotoxic response, it did increase their apoptotic potential due to the significant upregulation of CASP3 gene expression.

The CCNH and MCM4 genes also showed a significant positive fold change following exposure of BV2 cells to graphene. These genes are directly involved in transcriptional control, particularly in the functionality of the helicase enzyme, which is crucial for DNA recognition and replication initiation. Conversely, the negative cell cycle control gene CCNG2 also exhibited a 9.46-fold increase in fold change. Elevated expression of CCNG2 can inhibit cell proliferation by arresting the cell cycle between G0 and G1 phases, and may even promote apoptosis [

34].

After contact with graphene, BV-2 cells exhibited changes in gene expression profiles, indicating a preparation for cell division, followed by inhibition of this process due to cell cycle arrest and subsequent entry into apoptosis. These data reinforce the safety of mesenchymal stem cells concerning tumorigenesis.

Due to their ability to migrate to injured sites in response to environmental signals and to promote tissue regeneration through the release of anti-inflammatory and growth factors, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are obtained via a minimally invasive method, making them a patient-specific product and a promising tool in regenerative medicine [

35].

5. Conclusion, Strengths and Limitations

The microenvironment can profoundly affect the metabolism and phenotype of all cell types. Understanding the interaction between the chemical composition of graphene and fundamental cellular mechanisms is crucial and should be continuously evaluated due to the diverse production methods and applications of this versatile material. This study not only highlights the non-cytotoxic nature of graphene but also maps genes related to the cell cycle that are essential for cell fate. It demonstrates that exposure to graphene nanoplatelets enhances cell proliferation and self-renewal in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). The positive fold change in genes related to cell proliferation stability, including checkpoint and DNA repair genes, indicates a safe enhancement of the proliferative capacity of mesenchymal cells when boosted with graphene nanoplatelets

Similarly, the negative fold changes observed in genes associated with tumor development suggest that graphene-MSC interactions do not lead to the overexpression of these genes, thereby controlling cell fate and mitigating any potential tumorigenic risks often attributed to undifferentiated cells.

The literature indicates that graphene is not a homogeneous material; rather, each type of graphene can elicit a highly specific molecular response. Thus, the impact of graphene nanoplatelets, such as UGZ-1004, on gene expression is influenced by factors such as time, dose, and cell type. It is crucial to investigate whether the identified mechanisms are transient or if they may have long-term effects on cell fate and health. Future studies should be conducted using appropriate models, such as neurodegenerative disease models or joint trauma/musculoskeletal models, to explore long-term exposure effects comprehensively.

Additionally, future research should expand beyond single exposure scenarios to include repeated and prolonged exposure studies in both in vivo and preclinical models. The novel insights gained into the intracellular mechanisms of graphene nanoplatelets in mammalian cells and MSCs are valuable for advancing research and ensuring the safe use of these promising biomaterials.