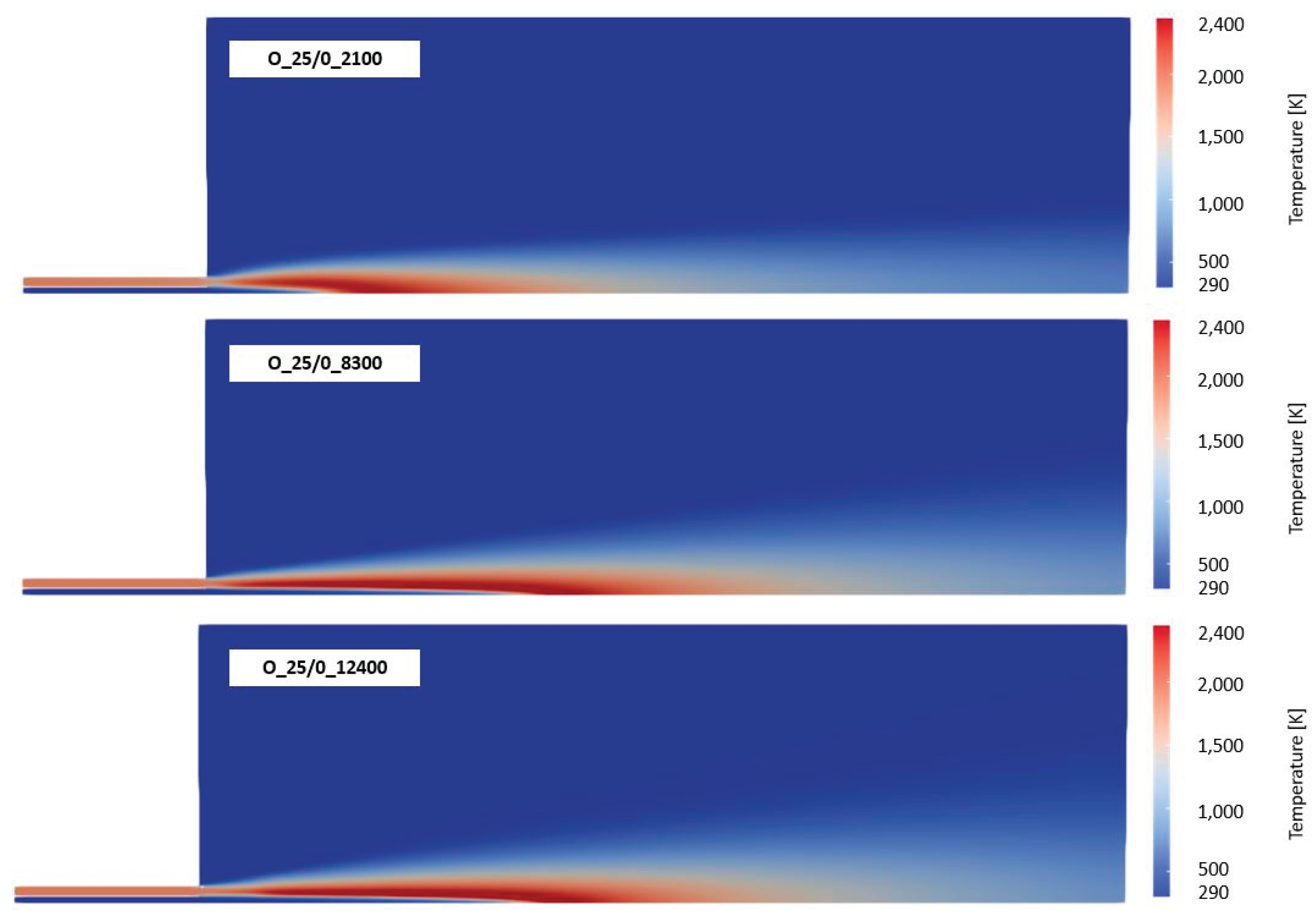

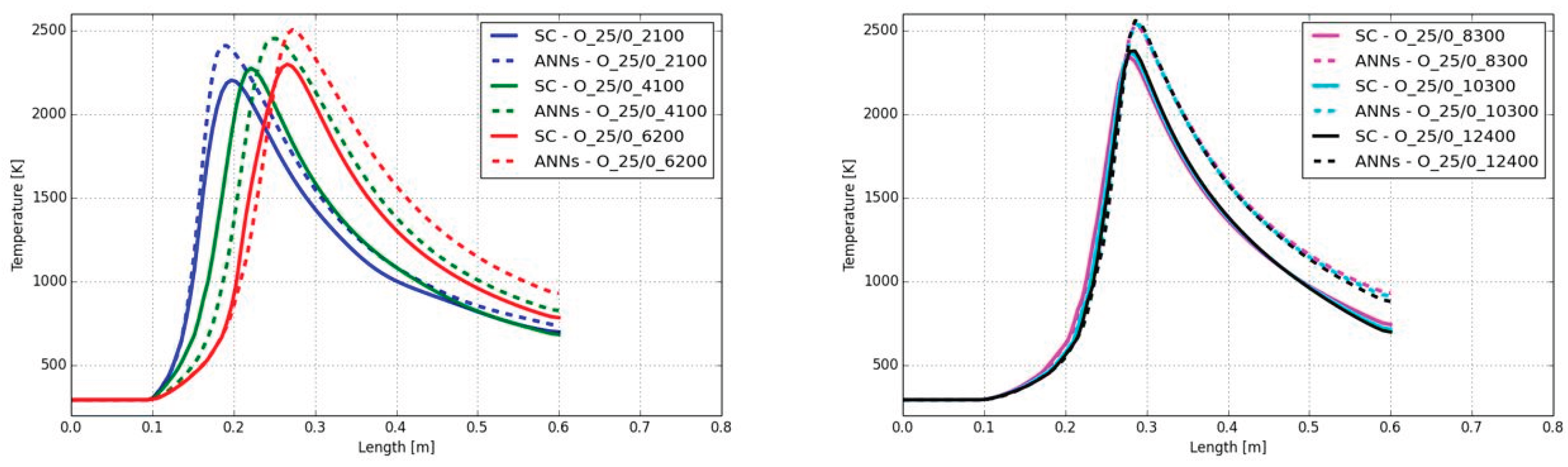

3.1. CFD Simulation of the Turbulent Flame and Reaction Mechanism

In this study the open-source code OpenFOAM v11 [

35] was used for the CFD simulations of the turbulent flame using the RANS equations. The information presented in this subsection can be found in more detail in [

36] and in the corresponding online user guide [

37]. For the simulation the “multicomponentFluid” solver [

38] was used, which is suitable for reactive flows and combustion simulation. In the solution procedure the PIMPLE algorithm was applied, which is a combination of the “pressure implicit with split of operators” (PISO) and “semi-implicit method for pressure-linked equations” (SIMPLE) methods. The basic principle is based on the calculation of an approximated velocity from the momentum equation. An additional equation is used to calculate the pressure. To calculate the continuity equation, the pressure and velocity are then corrected. However, this correction step means that the momentum equation is no longer fulfilled. The process is continued iteratively until the deviations in both the continuity equation and the momentum equation is sufficiently low.

To solve the momentum equation (see equation 8) the class “momentumPredictor()” is used. This step is used to calculate an initial guess of the velocity, which is corrected in later steps of the PIMPLE algorithm to fulfil the continuity equation (see equation 7). In equation 8 the variable

stands for the pressure and

is the dynamic viscosity. Additionally, in the class “thermophysicalPredictor()” in OpenFOAM the transport equations for the energy (see equation 9), based on the specific energy (see equation 10), and species (see equation 1) are solved. In the energy equation,

is the stress tensor,

is the thermal conductivity,

is the enthalpy. The last term in the energy equation stands for the heat source from the chemical reaction and is related to the calculated species source term from the chemistry calculation. Since the flames investigated in this study are of turbulent nature, a turbulence model was used, which was the standard k-epsilon model proposed by Launder and Spalding [

39]. As radiation model the P1 model was activated [

40,

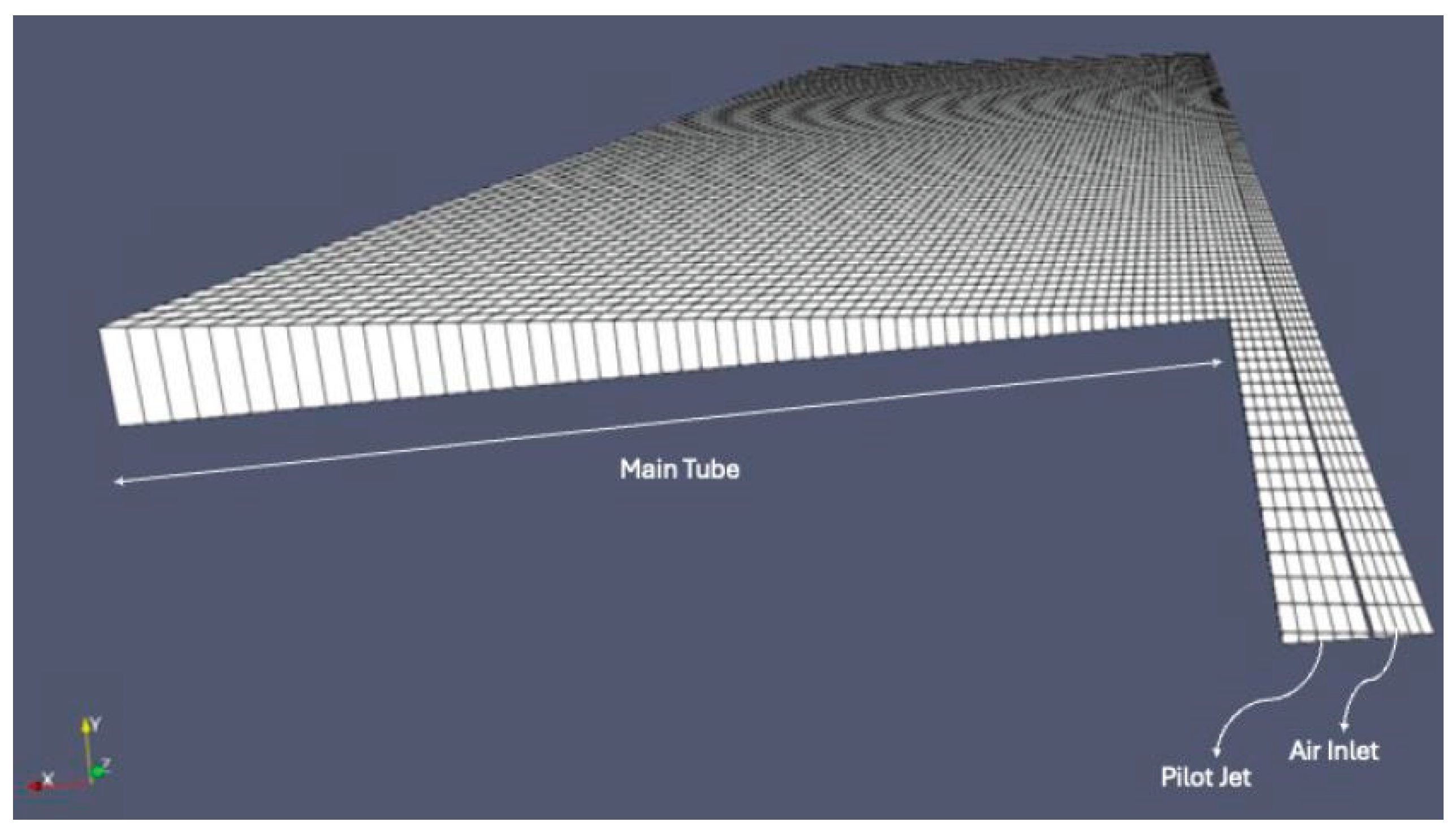

41]. The numerical grid, which was used for the simulations is later shown in section 4.

As explained in section 2, the source term for each chemical species

has to be determined. Considering equation 2, the volume fraction of the fine structure and the time scale will be determined based on the results from the turbulence models (turbulent kinetic energy, dissipation rate of the kinetic energy). However, the mass fractions in the fine structure after the fine structure time scale has to be calculated by the chemistry solver (integrating the chemistry). In the present study, reference simulations of all combustion cases (see section 4) will be carried out using the “seulex” solver [

42] in OpenFOAM, which is based on the linearly implicit Euler method with step size control [

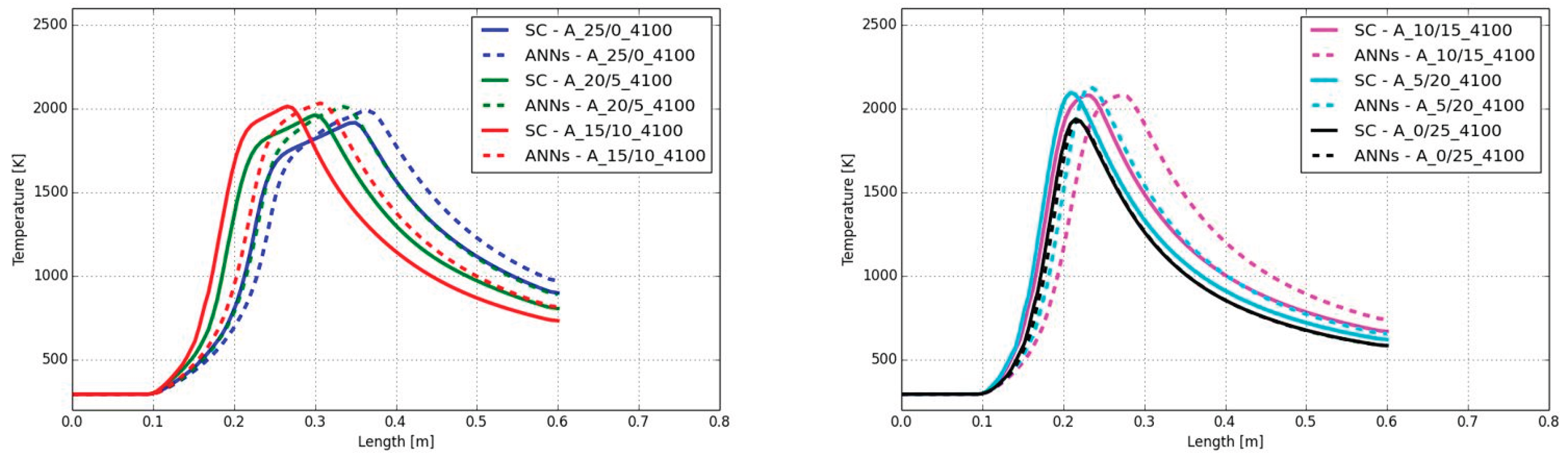

43]. For comparison in section 5 the simulations with this solver will be denoted as “standard” chemistry (SC) solver.

For the prediction of the reaction kinetics within the fine structure of a numerical cell, a so-called reaction mechanism has to be chosen. In the reaction mechanism the species involved in the chemical reactions as well as the equations of the chemical reactions are defined. So, for each reaction

the reaction rate of a species

can be calculated by equation 11. In this equation

and

are the stoichiometric coefficients of the species

at the reactant and the product side of the chemical equation,

and

are the reaction rate coefficients for the forward and backward direction of reaction

and

is the molar concentration of the species in the reaction

. Furthermore,

stands for the overall number of species in the reaction mechanism and

as well as

are the exponents forming the reaction order. In case of elementary reactions, the exponents are equal to the stoichiometric coefficients. The reaction rate coefficients can be derived by the Arrhenius equation (see equation 12 as example for a forward reaction). The Arrhenius approach includes the pre-exponential factor

, the temperature exponent

, the activation energy

and the universal gas constant

.

The values used in equation 12 can be found in the reaction mechanism. In the present study the authors used a modified mechanism from Jones and Lindstedt (JL), which was optimized in the work of Frassoldati et al. [

44]. All parameters of the reaction mechanism can be found in

Table 1.

Although more detailed reaction mechanisms are available in literature with several hundreds or even thousands of species and reactions, a rather simple mechanism with 10 species and 6 chemical reactions was used. Other authors already used more detailed mechanisms for the training of their ANNs (e.g., [

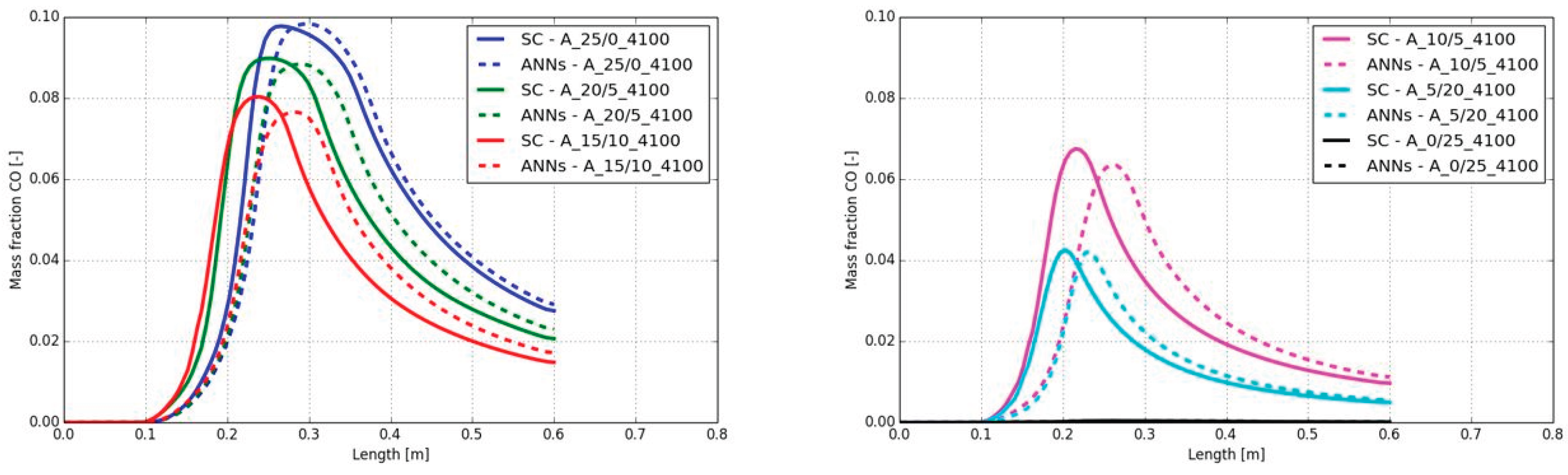

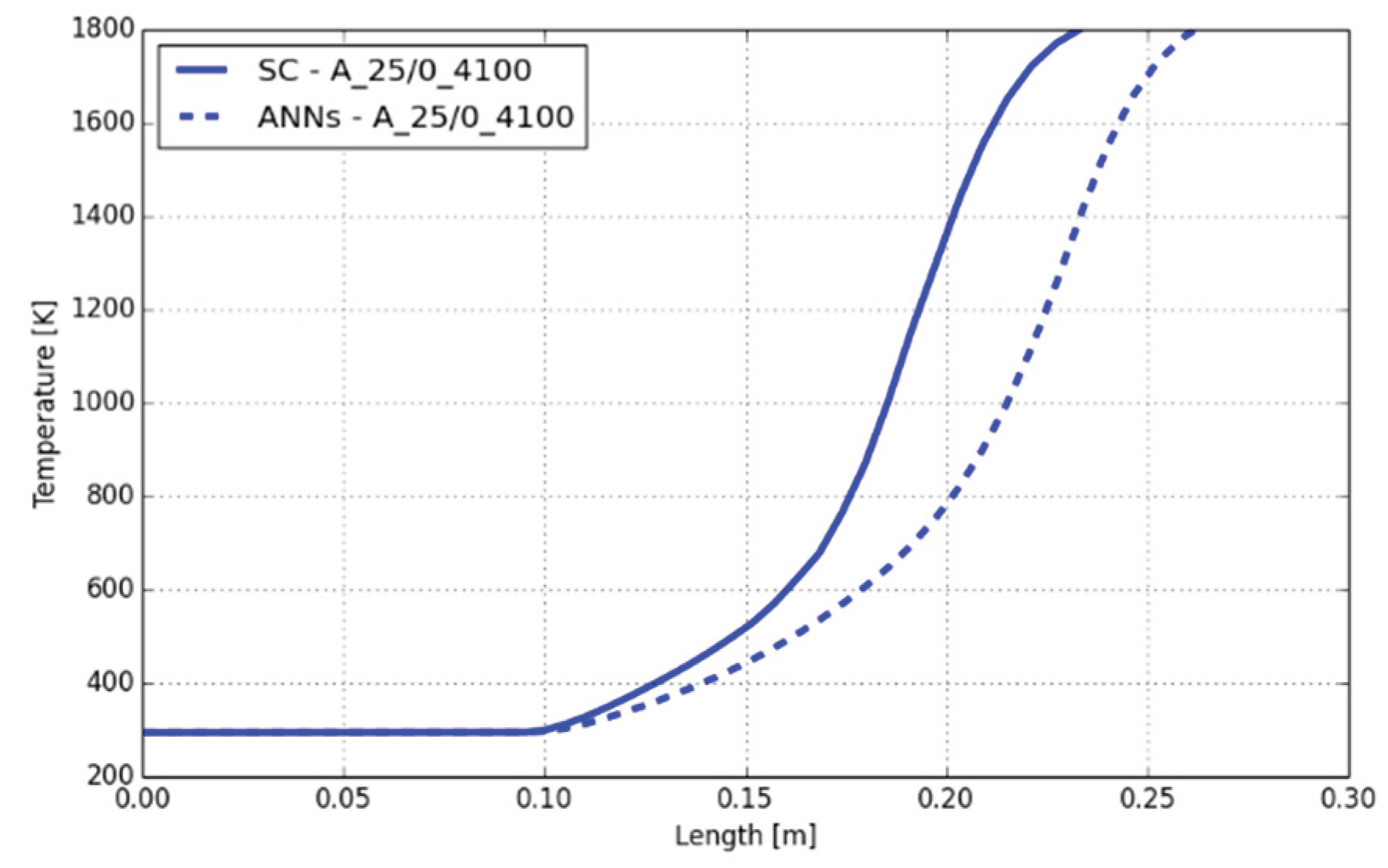

6]). However, the applicability or feature space (temperature and species concentrations) is often limited (e.g., from 700 to 3,100 K). So, using a reduced reaction mechanisms allows the training of the ANNs in the present study for a much wider range of the feature space without extensively increasing the size of the training data or training time. The size of the data for a detailed reaction mechanism for conventional natural gas combustion is already quite large. Extending the training data sets to different turbulence levels (affecting the time scale in the EDC), different fuel mixtures as well as oxy-fuel combustion would therefore lead to a large data size. Furthermore, important for an accurate prediction of the chemistry by the ANNs is that the AI-based method can handle the complexity of the reaction kinetic based on the high variation on the time scale and level of occurrence of some minor species. For example, from

Table 1 it can be seen that reaction 6 is much faster than reaction 1, 2 or 3 by several orders of magnitude. Additionally, the reaction mechanism comprises major species, such as CH

4, with high concentrations (mass fractions) and minor species, such as OH, with low amounts. In between the major and minor species also several orders of magnitude occur. These two aspects are the most critical parts for an accurate training of the ANNs and can be covered with the chosen reaction mechanism. The proposed training methodology described in the next sections should be applicable for larger reaction mechanisms, which will be worth investigating in future works.

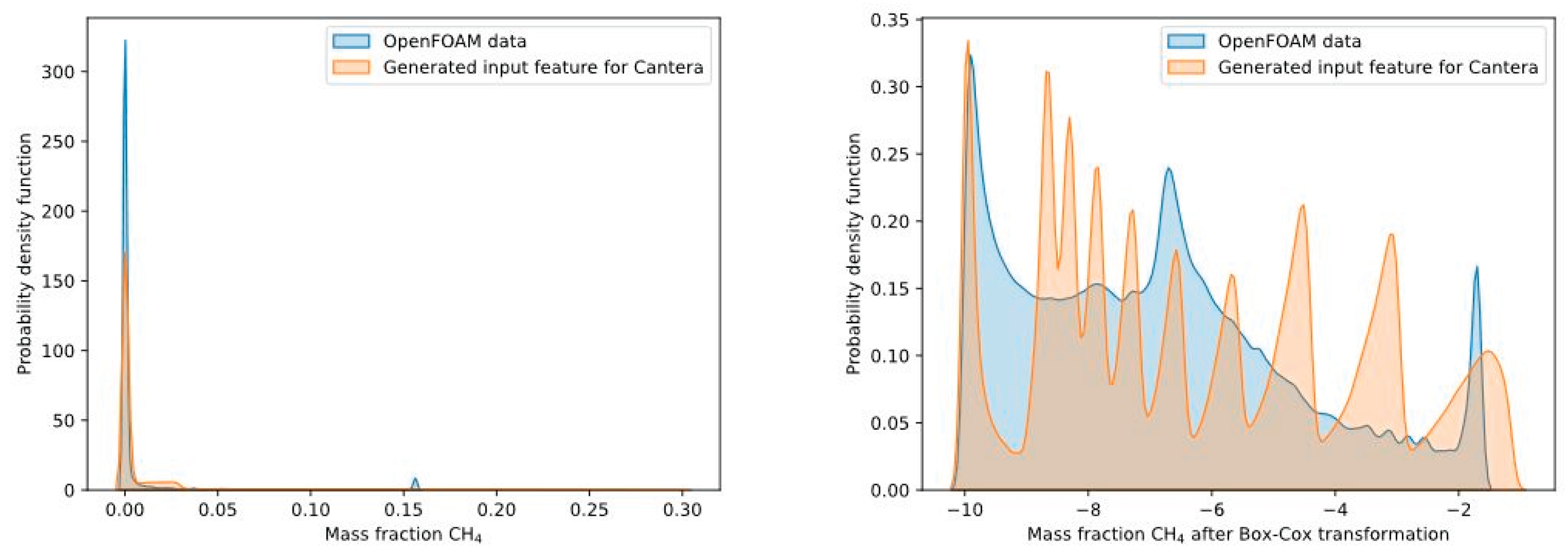

3.2. Data Generation and Pre-Processing

To avoid the usage of chemistry solvers for the predictions of the species source terms

, ANNs will be trained. It has to be mentioned that in the proposed framework not the species source term

will be predicted directly from the ANN. Looking at equation 13, the ANNs in the present study will calculate the source term

. The multiplication with the fine structure volume fraction

is done separately in OpenFOAM.

The resulting network function to approximate the species source term is denoted as in equation 13, where represents the input feature space defined within the domain Since the reaction rate of a species within a reactor (or fine structure) depends on the temperature, species concentrations and residence time (fine structure time scale), the input feature vector can be defined as . Subsequently, the vector for the species mass fractions is defined by all species involved in the reaction mechanism. During the CFD simulation the input feature vector for the ANNs can be formed by the values from the previous iteration step as well as the calculated time scale from the turbulence model according to equation 5 . It has to be mentioned that also the pressure is affecting the reaction rates, and should be considered in the input feature vector. However, in the present study the combustion takes place at ambient pressure without high gradients. Thus, the pressure is not part of the input feature space here.

For the supervised learning of the ANNs corresponding outputs are necessary. For this purpose, the open-source software Cantera [

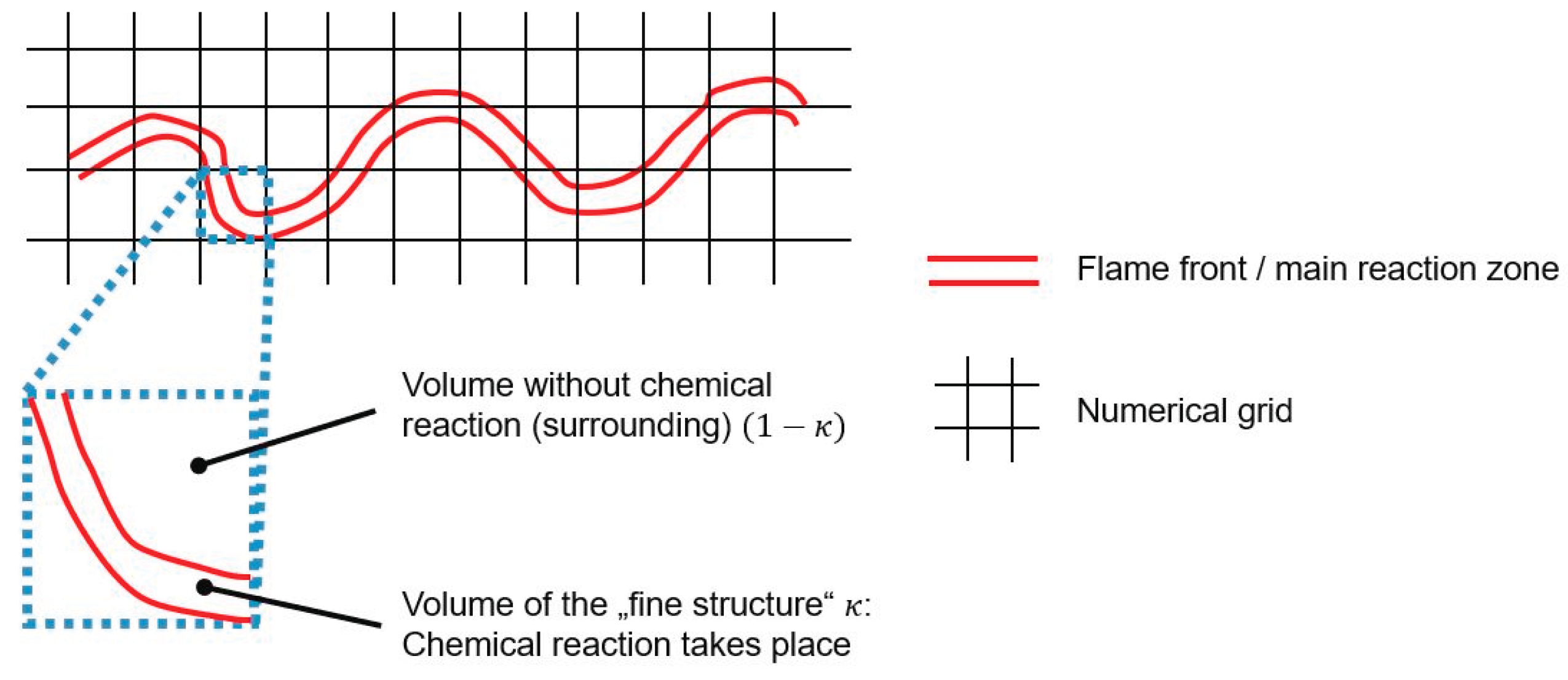

7] was used. As mentioned in section 2, the chemical reactions in the fine structures of a numerical cell can be approximated by a PSR or PFR. Due to the different modelling of the chemistry in the fine structures, which is shown in

Figure 2, the results of the two concepts also deviate from each other under the same initial conditions. When considering the fine structures as PSR, small eddies that arise on the surface or diffusion effects enable mass transfer with the environment of the main reaction zone. In the PFR, there is no mass transfer with the environment and the reactions can be considered as isolated from the environment. Accordingly, the consideration as PFR leads to a higher mean reaction rate compared to the PSR, since there is no back-mixing of reactants in the PFR. Bösenhofer et al. [

45] indicate that modelling of the fine structures as PFR provides good results under classical combustion conditions. If the focus is on a very detailed consideration of the reaction zone, the PSR approach should be chosen. Due to the lower numerical effort, the PFR approach was chosen for the data generation procedure with Cantera.

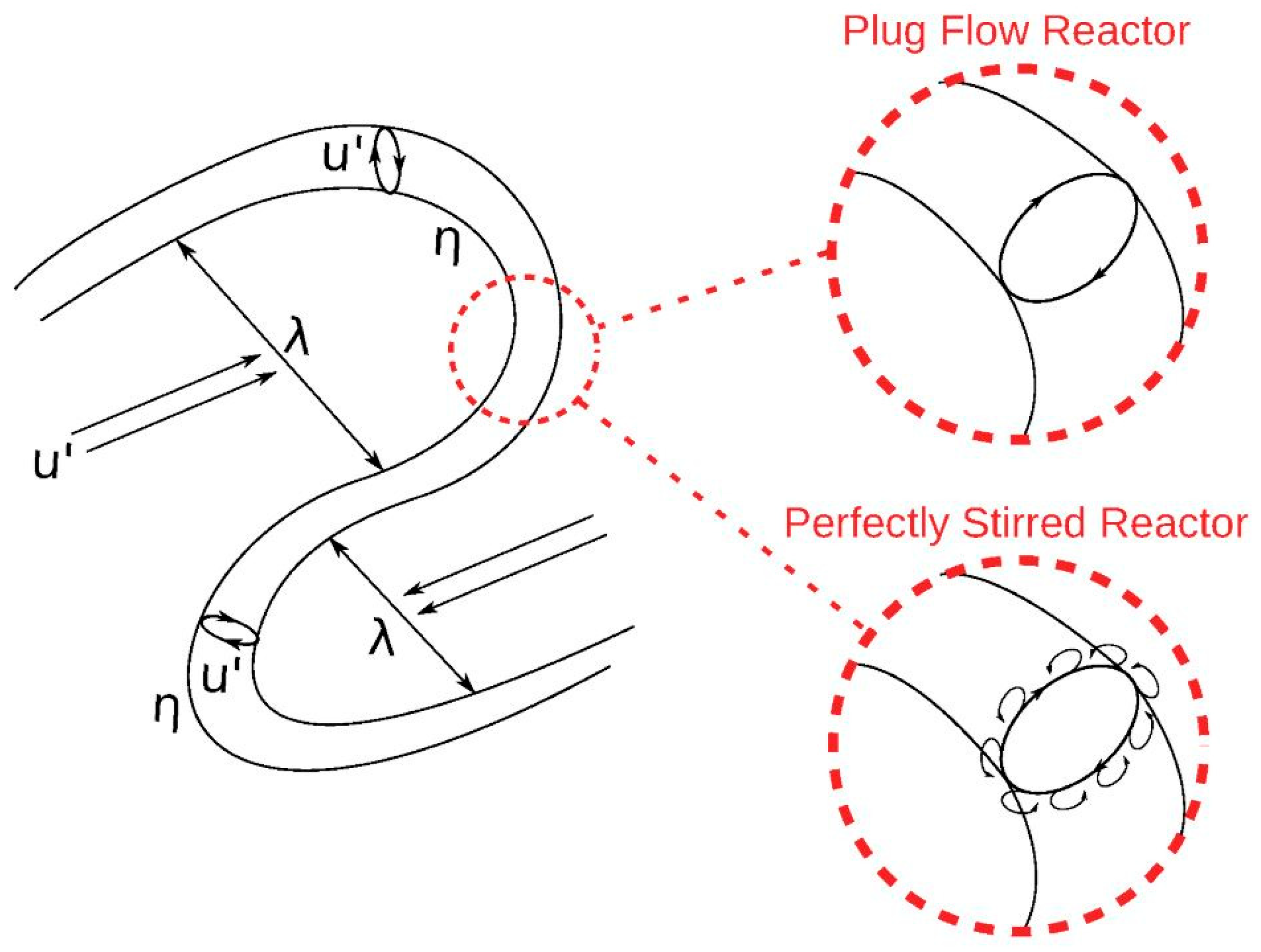

The PFR in Cantera is considered as a 1D stationary tubular reactor with a constant cross-section and constant flow-rate. The fluid is considered to be homogeneous in the radial direction and all diffusion processes in the radial and axial direction are neglected. Furthermore, the reactor is seen as operated under isobaric and adiabatic conditions. As an example for the species concentrations over time (length) in the PFR,

Figure 3 is shown below. The inlet conditions for the PFR can be seen as the species concentrations and temperature from the previous iteration step (conditions of the surrounding of the fine structure in the cell -

). The horizontal axis in

Figure 3 represents the residence time of the reactants in the PFR, which is equal to the fine structure time scale

, which means that with one PFR simulation several input features of the time scale can be derived. If a PSR would be used, a single simulation for each

has to be carried out, which would have significantly increased the time for data generation. Based on the input features temperature and species concentrations, the species mass fractions in the fine structure

after the time scale

can be determined. As a consequence, the network prediction (output feature)

can be formed in accordance to equation 13.

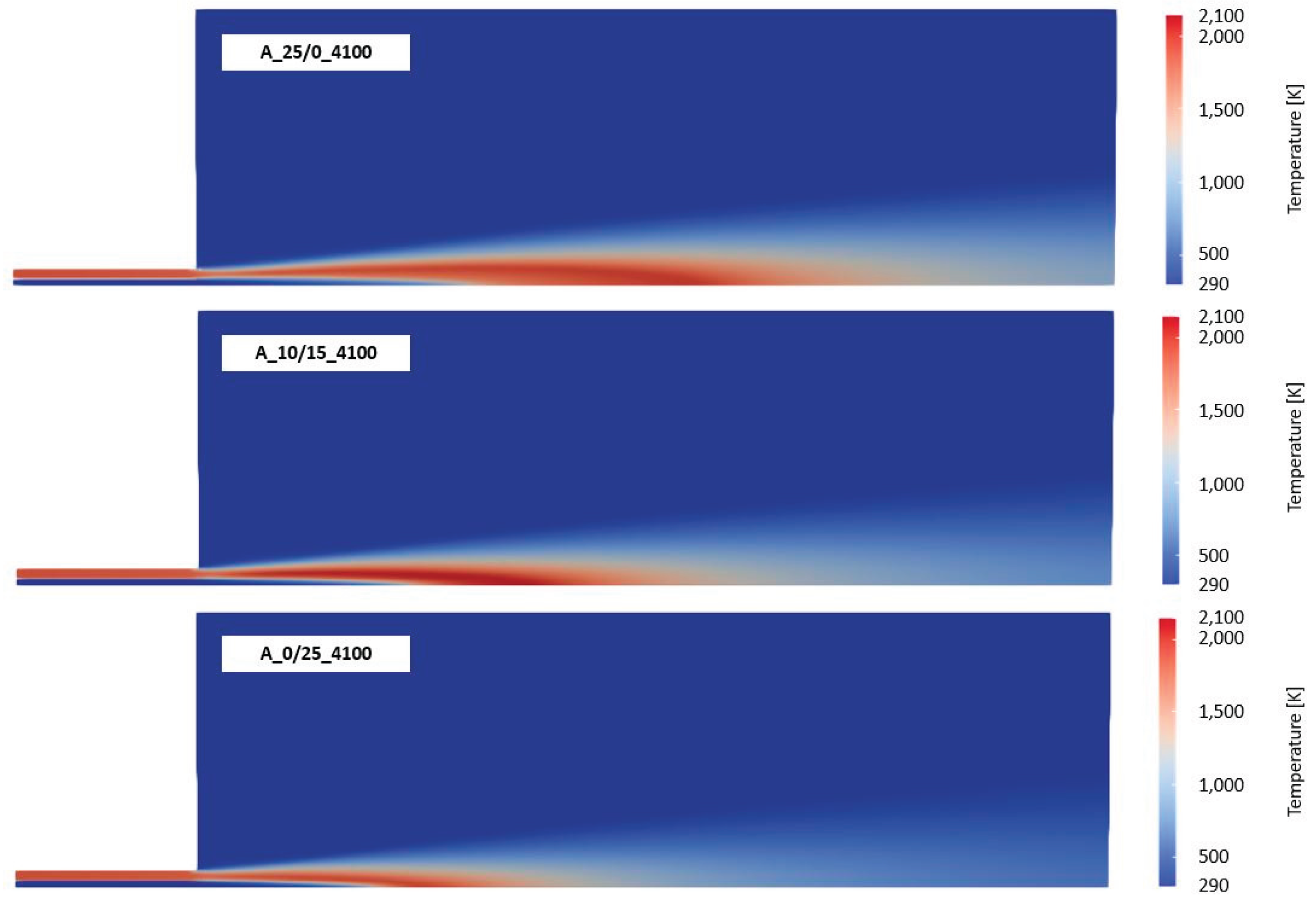

To define the input feature space, OpenFOAM simulations with the standard chemistry solver were carried out for all considered combustion cases (see section 4). During the simulations the minimum and maximum values of all species concentrations, temperatures and fine structure time scales were monitored. The observed maximum and minimum values were slightly extended to clearly avoid leaving the input feature space of the trained ANNs during the simulation. The range of each feature is shown in

Table 2. It can be seen that the temperature range is from below 0°C up to 2,600 K, which considers the full range of possible temperature in the considered combustion cases. Also, the oxygen mass fraction is significantly extended to 1. Thus, also oxy-fuel combustion can be considered by the ANNs. Since in combustion with pure oxygen the possible nitrogen mass fraction is reduced to 0. Within the ranges defined in

Table 2 the input features were chosen by Monte Carlo sampling. Only nitrogen was determined by the fact that the sum of all mass fractions must be 1. In

Table 2 also the distribution of the feature sampling is shown. For the time scale

a logarithmic sampling was chosen. This means that for the 30 samples of

in one PFR simulation more samples were defined for smaller time scales, since the gradients of the species concentrations and temperature are higher. For larger time scales the reaction moves towards equilibrium with low gradients. For the Monte Carlo sampling of the temperature and oxygen mass fraction a homogenous distribution of the random values was defined. The other distributions depend on whether the mass fractions of the species can reach larger values (l) or smaller values (s). For the species O and H (radicals) it can be seen in

Table 2 that the maximum mass fractions are below 0.005. So, these species are defined as small (s) and the other ones as large (l).

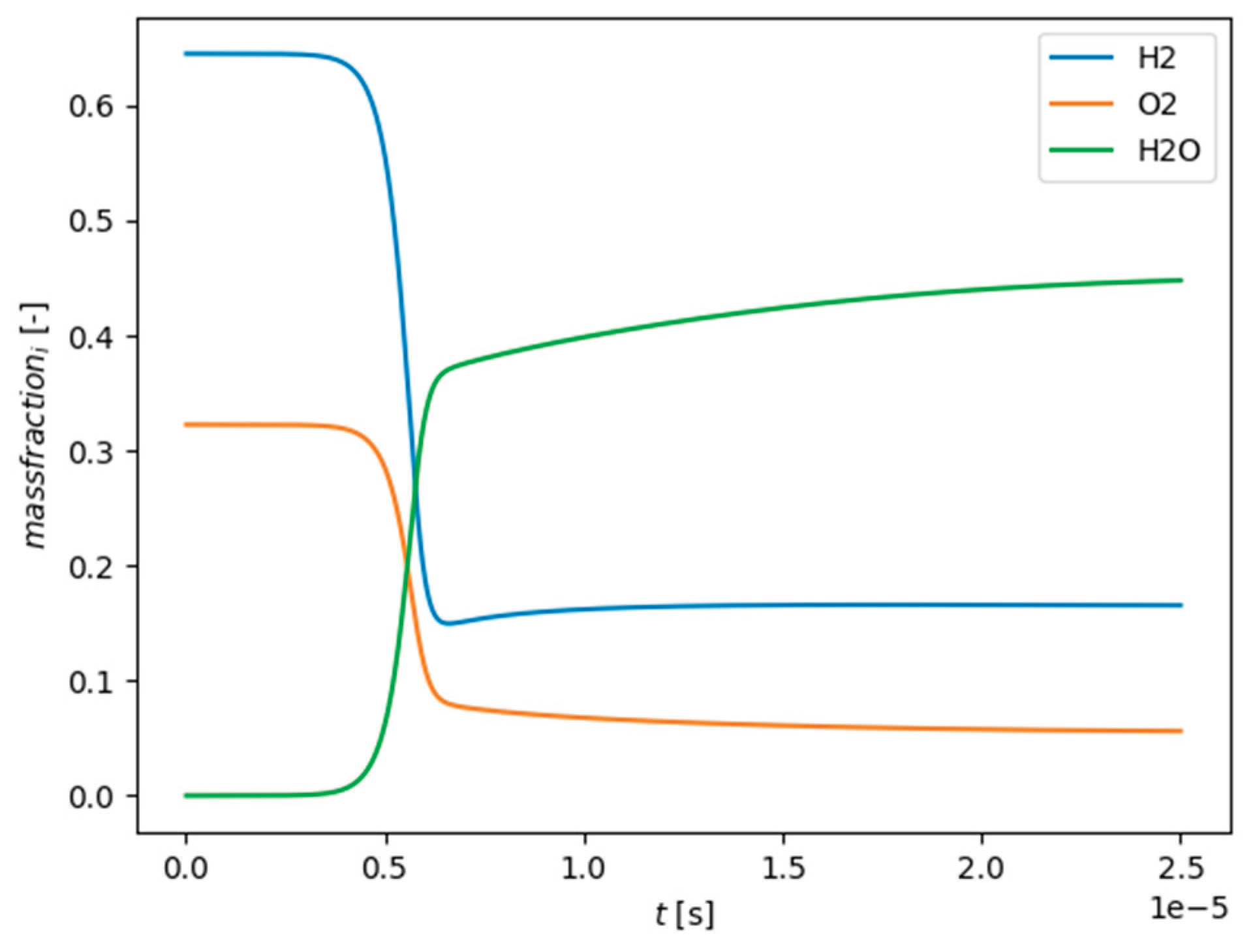

For data generation the input feature vector is formed by Monte Carlo sampling, which is quite clear for the time scale, the temperature and the oxygen mass fraction. At the first glance, it might be the case that the species mass fractions in all numerical cells during the OpenFOAM simulations are homogeneously distributed. For example, this can be seen in

Figure 4 (left) by the purple area, highlighting the probability density of the mass fraction of CH

4. In the majority of the numerical cells a very low mass fraction with an apparently Gaussian distribution is present. However, analyzing the results of the OpenFOAM simulations of all combustion cases showed that the mass fractions in all numerical cells of the simulation are not homogenously distributed. After transformation of the species mass fractions using the Box-Cox transformation with

[

48] according to equation 14, the distribution looks clearly different (see

Figure 4 (right)). Since the generated training data with Cantera should represent the “reality” (reference simulation with OpenFOAM) as good as possible, the distribution of the data sampling for the species mass fractions was defined as shown in

Table 3.

In

Table 3, 6 ranges for the species mass fractions were defined with a certain probability that the Monte Carlo sampling is using the specific range for the sampling. Considering the small mass fractions, it can be seen that most input features for these mass fractions will be generated from 10

-4 to 10

-3. For large mass fractions the majority of the input data will be generated in a range of 10

-3 to 10

-1, but also very small mass fractions will be considered during the sampling of the input features. With this sampling methodology for the input feature mass fraction, it is possible to generate input training data, which are in close accordance to the “real” conditions in the flame.

Figure 4 (right) shows that the generated input feature for Cantera matches well with the OpenFOAM simulation data. Now, the input features cover the entire range for all combustion cases and also the distribution of the features is in good agreement with “reality”. With these input features, Cantera simulations of the PFR will be done.

Before the input and corresponding output data

can be used for the training of the ANNs, pre-processing steps have to be carried out. Data pre-processing is an important tool for improving the convergence of the training algorithm. For example, the data should be normalized to an order of magnitude of

to prevent difficulties during the network training, which would lead to a lower learning rate for reasons of stability, and, thus slow down the learning process [

50]. It was proposed in [

51] that training usually converges faster when the data is close to a standard normal distribution. If the underlying data is not normally distributed, the data should be brought into an order of

. For the normalization of the input and output data the equations 15 (e.g., for species mass fraction

) and 16 (for the reaction rates

) were used. Both were normalized within a range of 0…1. Additionally, for the output data a root function was used. With the root function the output data fits the normal distribution much better.

Finally, the pre-processed data set has a size of approx. 32 GB and consists of approx. 38 million data points

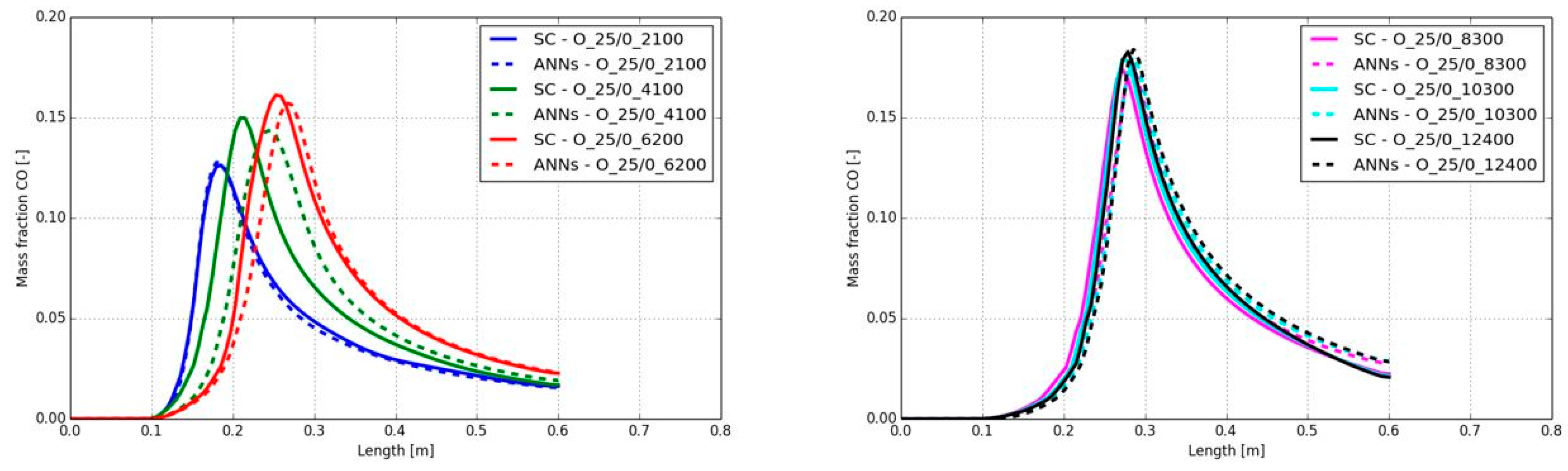

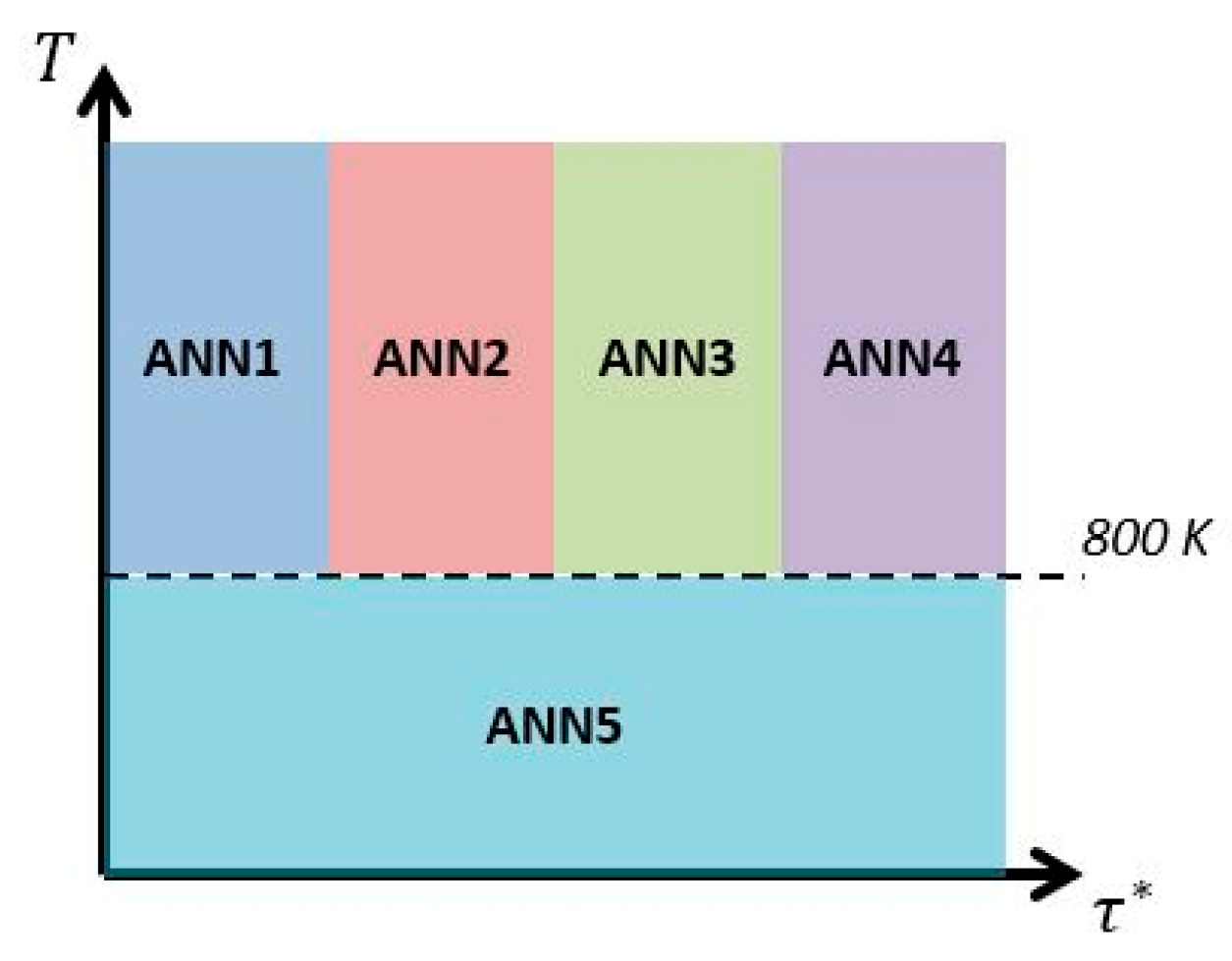

3.3. Subdivision of the Feature Space

The literature in section 1 highlighted that using one ANN might be not feasible for the prediction for the chemistry in the full range of input features. Several authors dramatically increased the number of ANNs in conjunction with a classification methodology (e.g., SOM in [

27]). An alternative is given by the DeepFlame framework [

6], which reduced the range for the input features for the single ANN trained for the chemistry prediction. Prieler et al. [

29] only trained two ANNs for the prediction of the chemical reactions in laminar counter-flow diffusion flames. The ANNs were trained for cases where ignition occurs and cases without ignition. Since this study revealed promising results with a limited number of ANNs significantly reducing the training time, a similar approach was used in the present study. Volgger [

52] stated that the applicability range for the separate ANNs can be related to the input feature of the temperature or the fine structure time scale. The temperature is highly affecting the reaction rates in the fine structure caused by the definition of the Arrhenius approach (see equation 12). However, the time scale was used as criterion, which ANN should be used in the numerical cell for the prediction of the reaction kinetics.

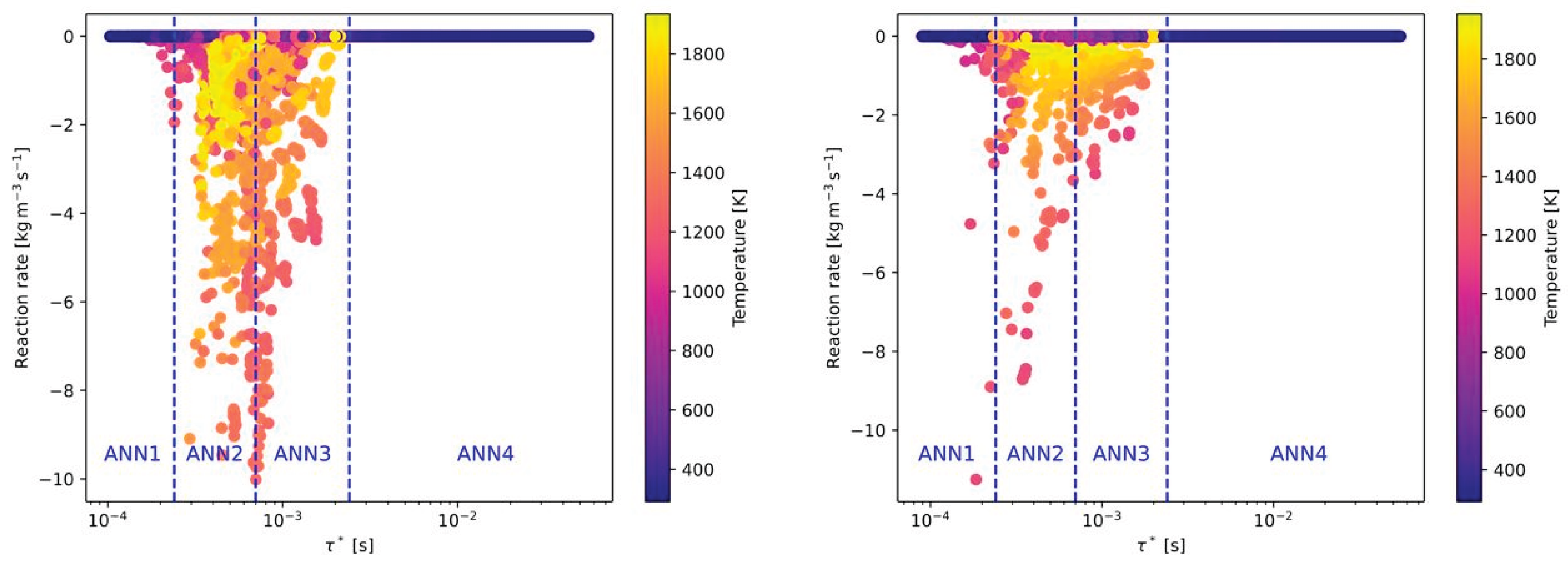

Four different ANNs were trained for pre-defined ranges of the fine structure time scale. In the following figures the reaction rates of all OpenFOAM simulations were presented depending on the fine structure time scale. The final regions of the time scale for each ANN (ANN1 to ANN4) are already marked in these figures and summarized in

Table 4. In

Figure 5 all reaction rates from the OpenFOAM simulations are presented for the combustion of CH

4 and H

2 with air. The reaction rates of these species were chosen because they are main fuel in these cases. The main target in defining the range of the time scale was, that one or two ANNs should cover the range where it comes to a combustion. The other ANNs should cover ranges without or a minor number of combustion cases. This approach is similar to Prieler et al. [

29] From

Figure 5 it can be seen that ANN2 and 3 cover the full range of the combustion cases with an equal distribution. ANN1 and ANN4 are considering time scales (nearly) without combustion. The highest reaction rates of CH

4 were found around a time scale of 0.0005 s

-1 and within a range of 0.0002 and 0.0011 s

-1. Thus, ANN2 and ANN3 were trained with data (input features) with these time scales. For the combustion of H

2 the maximum reaction rates occurred in a similar time scale (see

Figure 5 (right)).

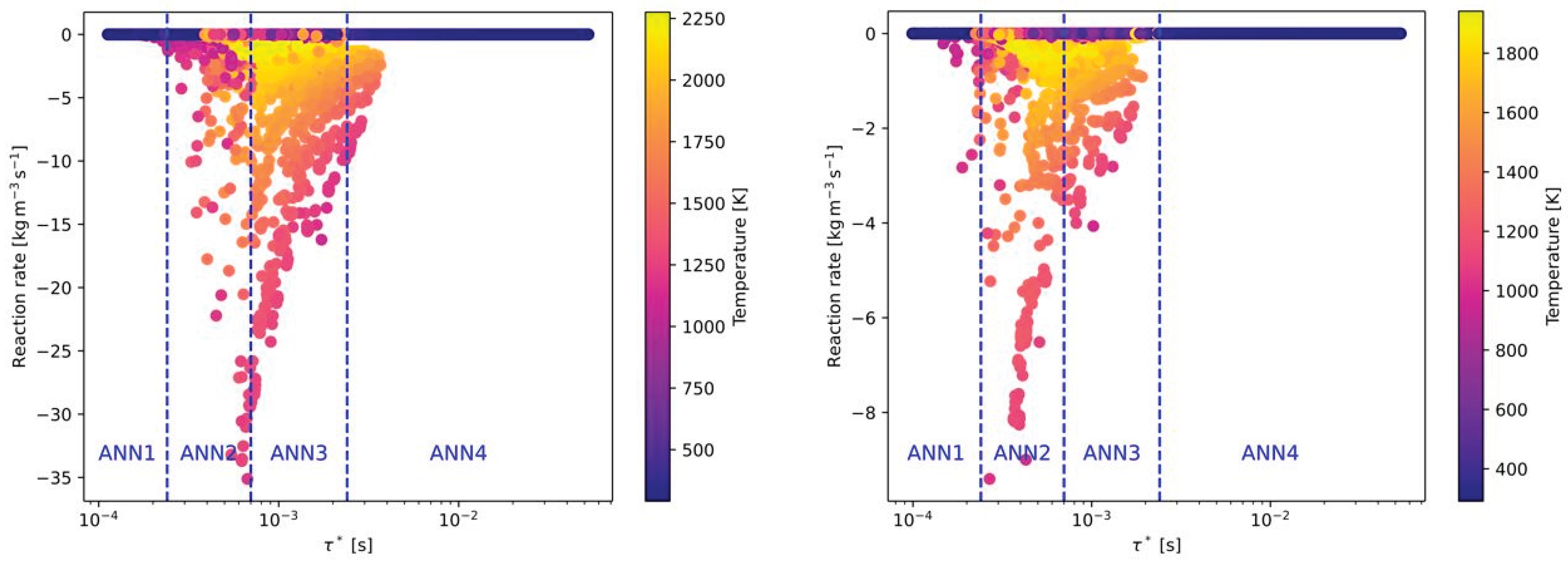

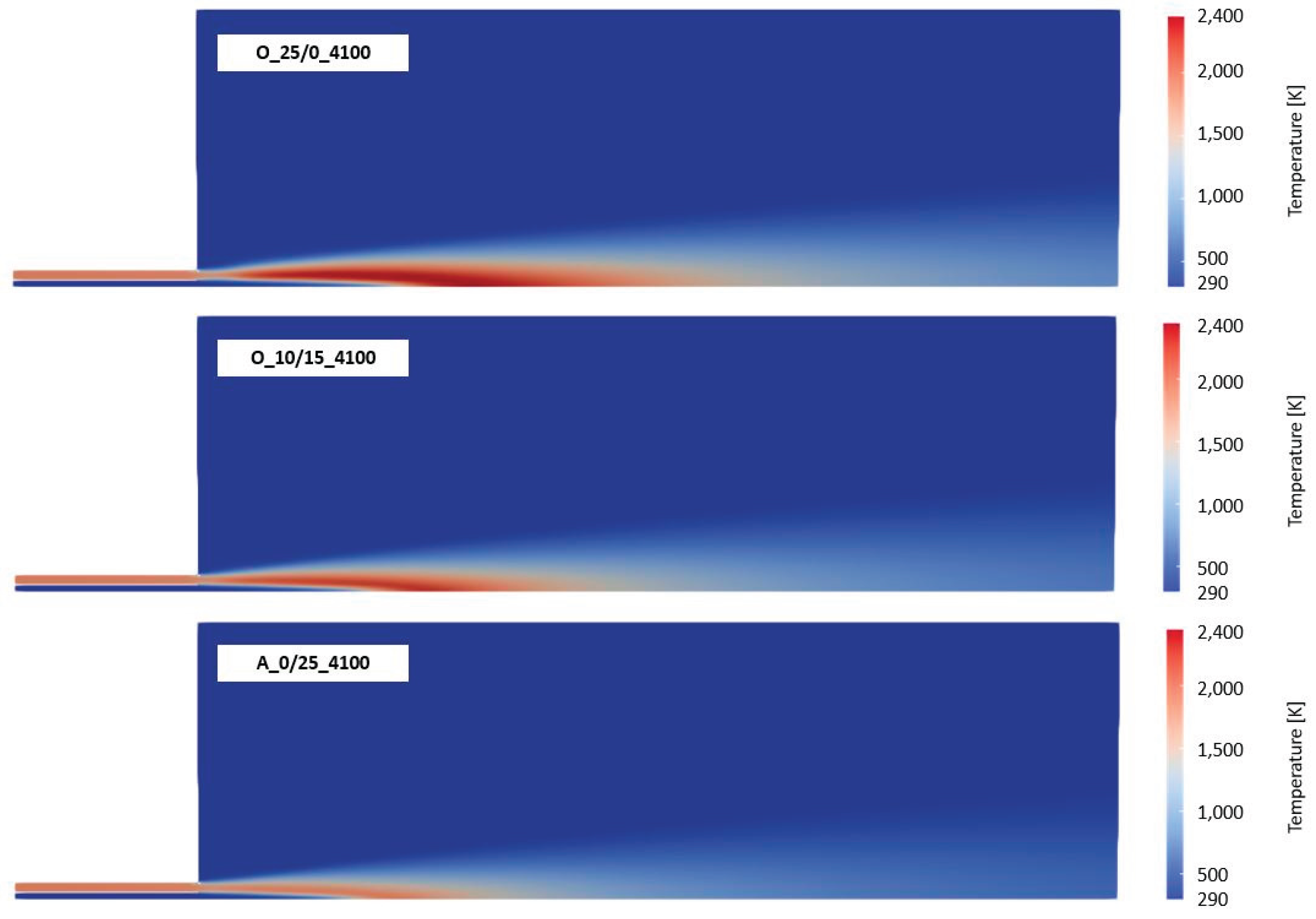

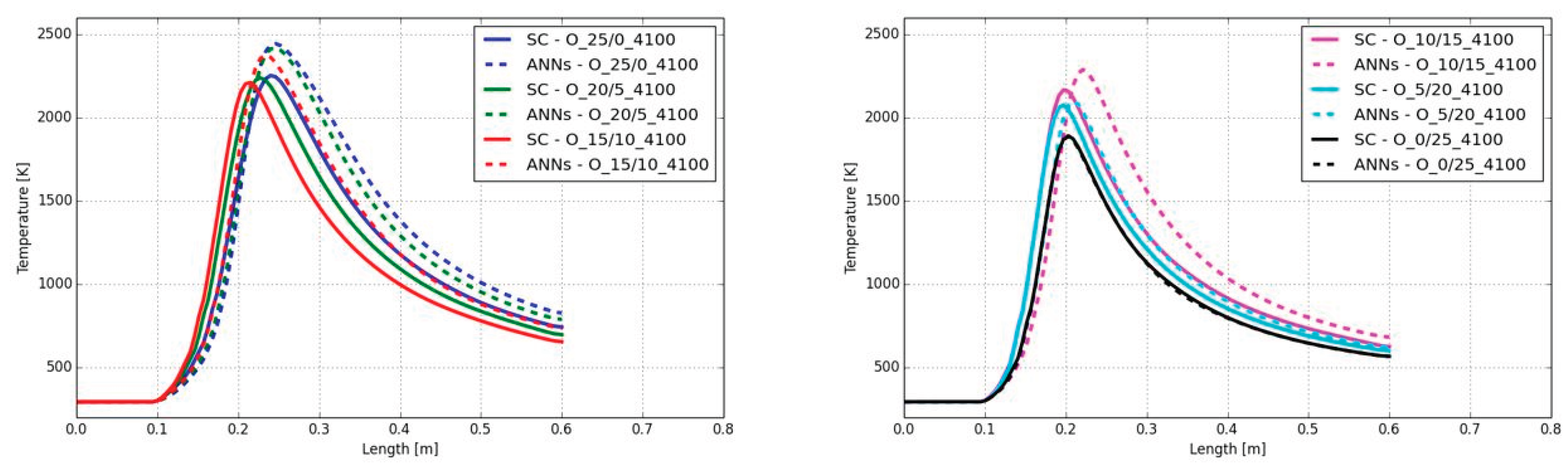

In

Figure 6 the same combustion cases (CH

4 and H

2) from

Figure 5 are presented, but with pure oxygen as oxidizer instead of air (without nitrogen). Although the combustion with pure oxygen is in general related to a higher reactivity, the OpenFOAM data showed that the time scales are similar to the combustion with air as oxidizer. Only a slight shift of the reaction rates to higher time scales can be observed. Therefore, the defined time scale ranges of the ANNs are also suitable for oxy-fuel combustion. It has to be mentioned that value of the reaction rates between air-fuel and oxy-fuel combustion is clearly different for the combustion of CH

4 with air (see

Figure 5 (left) and

Figure 6 (left)). Whereas the maximum reaction rates with air are approximately 10 kg/(m³s), the reaction rates with oxygen are more than 3 times higher. This difference between air-fuel and oxy-fuel combustion cannot be observed when H

2 is used as fuel.

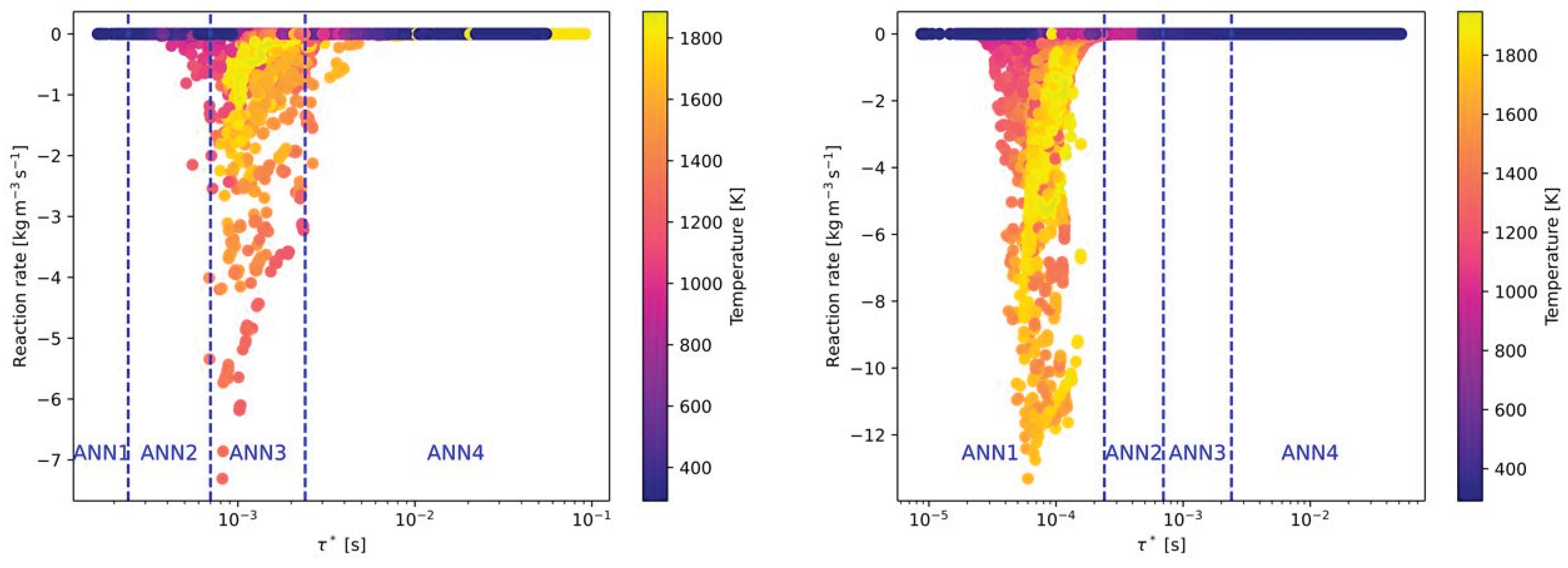

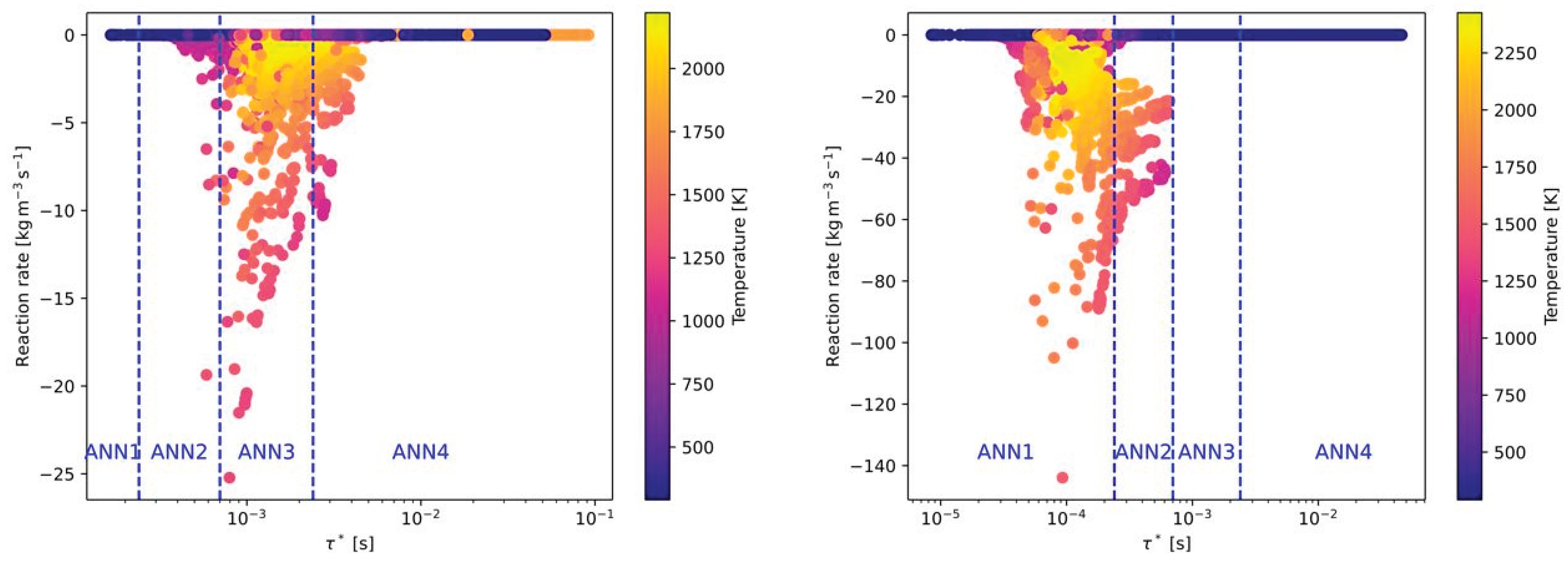

Besides the composition of the fuel and oxidizer, the third effect to by covered by the ANNs is the level of turbulence. As described later in section 4, 6 Reynolds numbers related to the flow conditions in the main jet of the burner were investigated. In

Figure 7 the effect of the Reynolds numbers on the reaction rates and time scales for the combustion of CH

4 with air is presented. Compared to

Figure 5 (left), the time scale, where the highest reaction rates occurred was shifted slightly to higher time scales (see

Figure 7 (left)). Thus, all cases with ignition are now located in ANN3. In contrast, higher turbulence in the main jet is significantly decreasing the time scales for high reaction rates. As a consequence, all burning cases are now in the range of ANN1. Similar as for air-fuel and oxy-fuel combustion of different fuels (see

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), there is hardly any difference on the time scales when switching from air-fuel (

Figure 7) to oxy-fuel combustion (

Figure 8) under different turbulence levels. But the maximum reaction rate is increasing again when oxy-fuel is used as oxidizer instead of air.

Finally, the analysis using the OpenFOAM simulation data showed that the time scale is only affected by the turbulence levels. The effect of the fuel mixture and the oxidizer is minor. However, the oxidizer is significantly affecting the level of the maximum reaction rates.

For the air-fuel and oxy-fuel combustion cases with all fuel types the ANN1 was should be used for higher Reynolds numbers when an ignition case is considered. With decreasing turbulence level in the main jet, the ANN1 is replaced by ANN2 and ANN3. For larger time scales ANN4 is applied, which represents cases without ignition for all air-fuel cases. In

Table 4 the ranges of the time scales for each ANN are summarized.