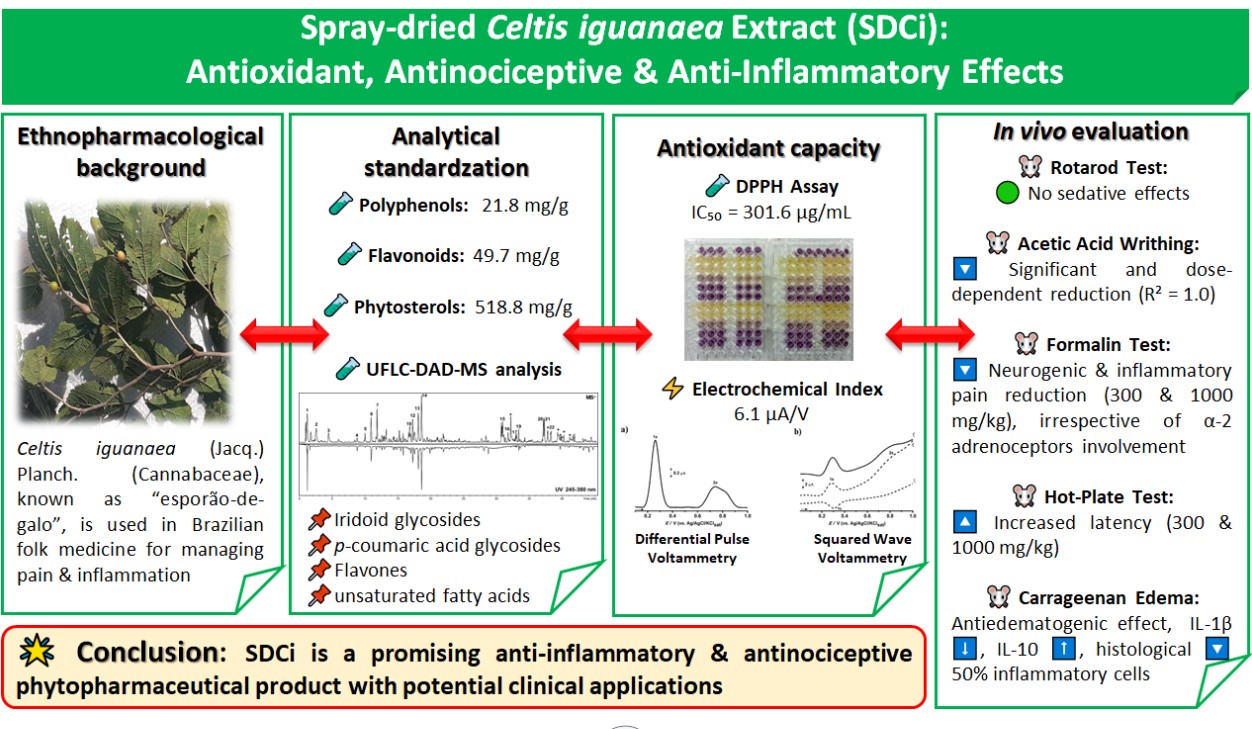

1. Introduction

Medicinal remedies such as infusions and “bottled preparations” derived from the leaves of

Celtis iguanaea (Jacq.) Planch. (Cannabaceae), a plant species widely distributed in Brazil and has been traditionally used in folk medicine to treat various conditions, including body aches, rheumatism, chest pain, asthma, colic, dyspepsia, urinary infections, and diabetes mellitus [

1,

2]. Reports from some cities of Ecuador indicate that infusions made from the leaves, and fruits of

C. iguanaea are used to treat kidney and liver pain [

3].

For over a decade, preclinical studies conducted by our research group and others across the country have investigated these ethnopharmacological claims and confirmed their therapeutic potential [

1,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Recently, our research group demonstrated that oral administration of the crude ethanolic leaf extract of

C. iguanaea (CEE) (300 mg/kg) blocked the vanilloid system, suggesting inhibition of nociceptive transmission mediated by this pathway. Furthermore, the involvement of opioid receptors in the antinociceptive activity was ruled out, as naloxone administration did not reverse the extract's effect on the capsaicin test (TRPV1 receptor agonist) [

5]. The anti-inflammatory activity of CEE was evaluated using the Croton oil-induced ear edema test and the carrageenan-induced pleurisy test. The CEE (300 mg/kg) significantly reduced ear edema, leukocyte migration, myeloperoxidase activity, and TNF-α levels [

10].

Given these outstanding outcomes, complementary studies are needed to ensure the safety and efficacy of phytomedicines derived from

C. iguanaea leaves. It is essential to recognize the ongoing efforts towards standardizing the phytochemical composition of

C. iguanaea extracts and comprehensively understanding their mechanisms of action. Additionally, there is a gap in understanding how these extracts behave during processes commonly used in developing phytopharmaceuticals, such as spray drying. Compared to previously studied crude extracts and fractions, the use of standardized dry extracts offers several significant advantages to the patients. These include high chemical and microbiological stability, ease of handling, transport, and storage, particle morphology, granulometric distribution, density, and flow properties that facilitate the production of solid dosage forms (tablets, capsules, and granules) with predictable dosing and therapeutic effects. These characteristics make standardized dry extracts valuable pharmaceutical intermediates [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Therefore, standardized dried extracts are required by regulatory agencies to ensure the safety and efficacy of phytopharmaceuticals, which can facilitate their registration, prescription, dispensing, and pharmacovigilance in regulated markets. Finally, standardization can promote the more efficient use of plant resources, minimizing waste and ensuring the sustainable production of phytomedicines [

11,

12,

13,

14].

In this study, we aim to address several key questions by obtaining, standardizing, and evaluating the in vivo antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of SDCi: i) Is the antinociceptive activity of SDCi dependent on its sedative properties? ii) Given that α-2 adrenoceptors are involved in the gastroprotective effects of

C. iguanaea [

9], and considering the potential link between these receptors and antinociceptive activity [

15,

16], could α-2 adrenoceptors be involved in the antinociceptive effect of SDCi? iii) Does the spray-drying process affect the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in comparison to our previous findings?

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Composition of SDCi

The spray-drying process resulted in a free-flowing greenish powder with low hygroscopicity and good solubility in water or saline (≤ 2 mg/mL). The TPc, TFc, and TPSc were 21.8 ± 0.8 mg/g (gallic acid equivalents), 49.7 ± 0.6 mg/g (rutin equivalents), and 518.8 ± 18.0 mg/g (β-sitosterol equivalents), respectively. Thus, animals treated with SDCi at doses of 100, 300, and 1000 mg/kg received on average 2.2, 6.6, and 21.8 mg/kg of polyphenols; 5, 15, and 49.7 mg/kg of flavonoids; and 52, 156, and 518.8 mg/kg of phytosterols, respectively.

Figure S1 presents the chromatographic and spectral profiles of SDCi obtained through UFLC-DAD-MS, revealing the presence of at least twenty-two compounds. Additionally,

Table 1 summarizes the results from the UFLC-DAD-MS analyses. By comparing these findings with previously published studies on extracts of

C. iguanaea or other species, the presence of one iridoid glycoside, two hydroxycinnamic acid heterosides (

p-coumaric acid hexosides), two octenol glycosides, four flavonoids (flavones, including two apigenin-derived heterosides and two luteolin-derived heterosides), and eight fatty acid derivatives is suggested. Three compounds remain unidentified.

2.2. In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity of SDCi

The antioxidant capacity of SDCi was demonstrated using well-established analytical techniques. The IC₅₀ value determined for SDCi was 301.6 ± 38.8 µg/mL. The voltammograms obtained by differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) and square-wave voltammetry (SWV) are shown in Figure S2, demonstrating the thermodynamic feasibility of the redox process for SDCi. As shown in Figure S2A, two anodic peaks (Ep1a = 0.26 V and Ep2a = 0.74 V) were detected in the DPV analysis of SDCi. The electrochemical index (IE) calculated by DPV was 6.1 μA/V. Additionally, Figure S2B presents the SWV voltammogram of SDCi, revealing two anodic peaks (Ep1a and Ep2a) and one cathodic peak (Ep1c), with Ep1a and Ep1c occurring at 0.254 V. Thus, the reversibility of the redox pairs can be confirmed based on the equivalence of kinetic parameters (Ipa/Ipc ≈ 1).

The voltammograms illustrate the presence of electroactive species in the phytocomplex. The values of Epa and Ipa are thermodynamic and kinetic parameters of redox processes. Powerful antioxidants undergo electrochemical oxidation at anodic peak potentials (

Epa) below 0.5 V at neutral to acidic pH. SDCi exhibited two anodic peaks with currents of 1.44 µA (

Ip1a) and 0.45 µA (

Ip2a), respectively. The higher the anodic peak current (

Ipa), the greater the concentration of the corresponding species and/or the faster the electron transfer kinetics in the redox reaction [

26]. Moreover, since regeneration capacity can enhance antioxidant function, the reversibility observed in the redox process of SDCi (

Ipa/Ipc ≈ 1) is a noteworthy feature, indicating its efficient antioxidant activity

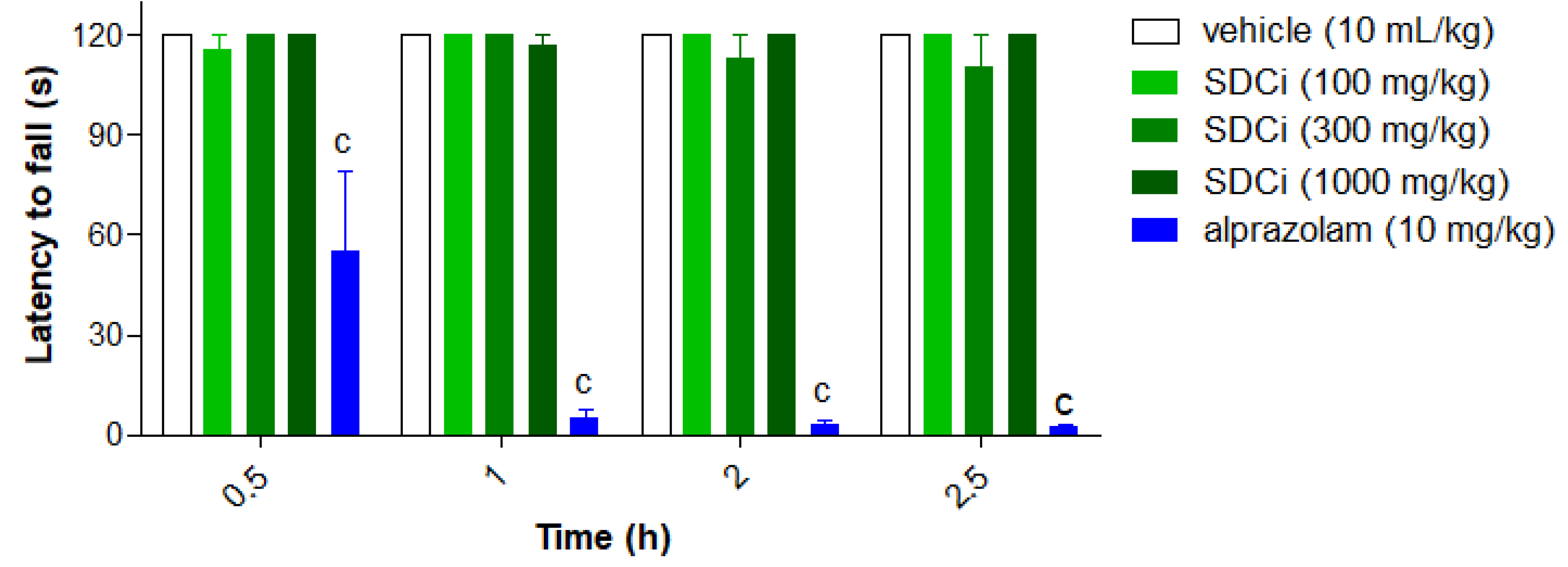

2.3. The SDCi did not Induce Sedative Effects in the Rotarod Test

As shown in

Figure 1, none of the treatments (p.o.) with SDCi significantly affected the animals' locomotor or balance performance over the 2.5-hour period compared to the vehicle (120 s, p-value > 0.05). In contrast, the positive control group (alprazolam, 2 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly reduced (p-value < 0.001) the time the animals remained on the rod at 0.5, 1, 2, and 2.5 hours (by 54%, 96%, 97%, and 98%, respectively). The lack of a significant effect on the duration of stay suggests that the extract does not induce sedative or adverse neurological effects, thereby supporting its safety.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n= 6). cp-value < 0.001 indicates the significant level when compared to the vehicle group using two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-test at the 95% confidence interval.

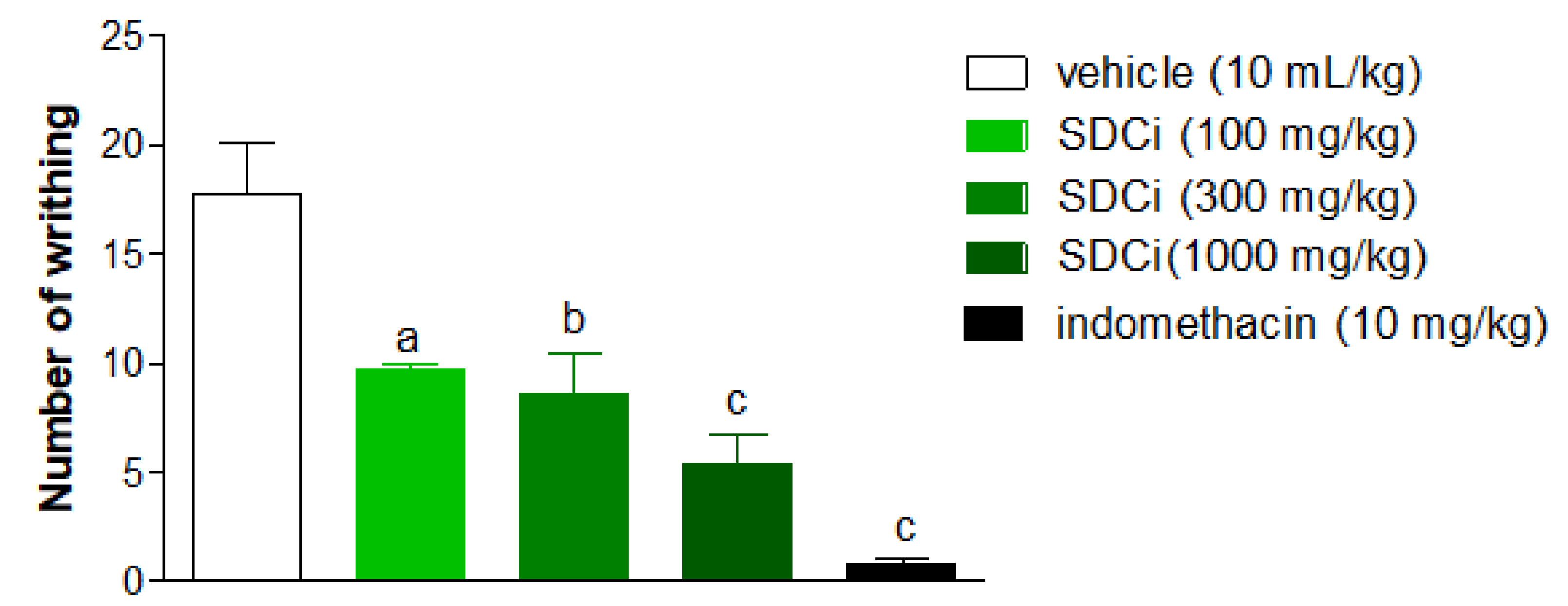

2.4. The SDCi Reduced Abdominal Writhing Induced by Acetic Acid

As shown in

Figure 2, SDCi significantly reduced the number of abdominal writhing or pain induced by intraperitoneal injection of acetic acid in a dose-dependent manner (R² = 1.0). Oral administration of SDCi at doses of 100, 300, and 1000 mg/kg reduced the number of writhing by 44.9% (p-value < 0.01), 51.7% (p-value < 0.01), and 69.7% (p-value < 0.001), respectively, compared to the vehicle (17.8 ± 2.4). The reduction in writhing observed in animals treated with indomethacin (10 mg/kg) was 95.8% (p-value < 0.001). Given the low specificity of the abdominal writhing test, we subsequently conducted the formalin test, which offers a more discriminative measure for determining whether the inhibition of nociceptive stimuli is due to a central or peripheral mechanism

Indomethacin (p.o) was used as a positive control. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6), in absolute values of the number of writhing. ap-value < 0.05, bp-value < 0.01, and cp-value < 0.001 indicate the level of significance when compared with the group that received vehicle (0.9% saline solution, p.o), using the ANOVA test followed by the Newman-Keuls post-hoc test, with a 95% confidence interval.

2.5. SDCi Effectiveness in Both Neurogenic and Inflammatory Phases of the Formalin Test

As shown in

Figure 3A, oral administration of SDCi at doses of 300 and 1000 mg/kg significantly reduced the licking time in the first (neurogenic) phase of the formalin test by 33% (p-value < 0.05) and 38% (p-value < 0.05), respectively, compared to the vehicle group (60.6 ± 3.3 s). In the second (inflammatory) phase, as presented in

Figure 3B, administration of 100, 300, and 1000 mg/kg of SDCi reduced the licking time by 47% (p-value < 0.01), 77% (p-value < 0.001), and 87% (p-value < 0.001), respectively, compared to the vehicle group (147.2 ± 37.9 s). These results indicate a dose-dependent effect (R² = 0.7) in the reduction of nociception.

Indomethacin (p.o) and morphine (s.c.) were used as positive controls. First phase (0-5 min) and second phase (15-30 min). The results represent the means ± EPM (n = 6) of the licking time (s). ap-value < 0.05, bp-value < 0.01, and cp-value < 0.001, indicate the significance levels when compared to the vehicle group (0.9% saline solution, p.o), using the ANOVA test followed by the Newman-Keuls post-hoc test, with a 95% confidence interval.

Treatment with the positive control morphine (7.5 mg/kg) reduced the licking time in the first phase by 97% (p-value < 0.001) and in the second phase by 100% (p-value < 0.001) compared to the vehicle. On the other hand, as expected, the positive control indomethacin (10 mg/kg) only reduced reactivity to nociception in the second phase by 90% (p-value < 0.001) compared to the vehicle. The formalin test confirmed the involvement of both central and peripheral components in the antinociceptive activity of SDCi. To further explore the central effect, we conducted the hot-plate test to determine whether it depends on the activation of vanilloid receptors (TRPV1), known to respond to high temperatures, similar to CEE [

5].

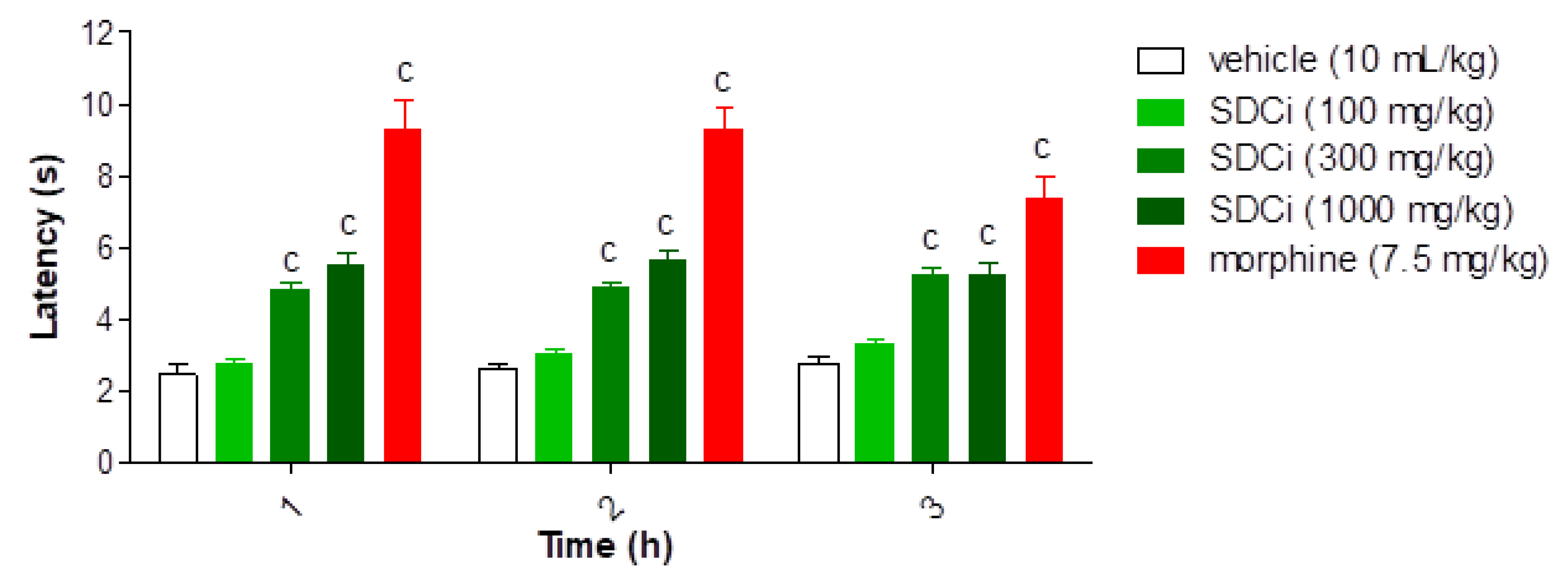

2.6. SDCi Reduced Nociception Induced by Thermal Stimuli in the Hot-Plate Test

As shown in

Figure 4, after 1, 2, and 3 hours, the groups treated with 300 mg/kg (95.8%, 89.5%, and 89.8%, respectively) and 1000 mg/kg (123.5%, 119.4%, and 89.3%, respectively) of SDCi exhibited a statistically significant increase in latency time compared to the control group (2.4 ± 0.3 at 1 hour; 2.6 ± 0.1 at 2 hours; 2.8 ± 0.2 at 3 hours; p-value < 0.001). Similarly, treatment with morphine increased latency time by 280.1% (p-value < 0.001), 258.2% (p-value < 0.001), and 165% (p-value < 0.001) compared to the vehicle group. While the morphine-induced effect on thermal nociception diminished over time, the action of SDCi at both effective doses remained consistent throughout the test.

Morphine (s.c) was used as a positive control. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n= 6). cp-value < 0.001 indicates the level of significance when compared to the vehicle group (0.9% saline solution, p.o), using two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-test at the 95% confidence interval.

Given that previous studies have already refuted the hypothesis of the CEE acting on opioid receptors in its antinociceptive activity [

5], we proceed to investigate the involvement of α-2 adrenergic receptors. The intermediate dose was selected since no statistically significant differences were observed between the 300 mg/kg and 1000 mg/kg doses in the rotarod, formalin (1st phase), and hot-plate tests. This approach also aligns with the 3Rs principles (Reduce, Replace, Refine) by minimizing the number of animals used in the experiments [

27,

28,

29], and preventing potential non-specific interactions associated with adverse effects, as discussed elsewhere [

8].

2.7. The Antinociceptive Effect of SDCi is Independent of α-2 Adrenergic Receptors

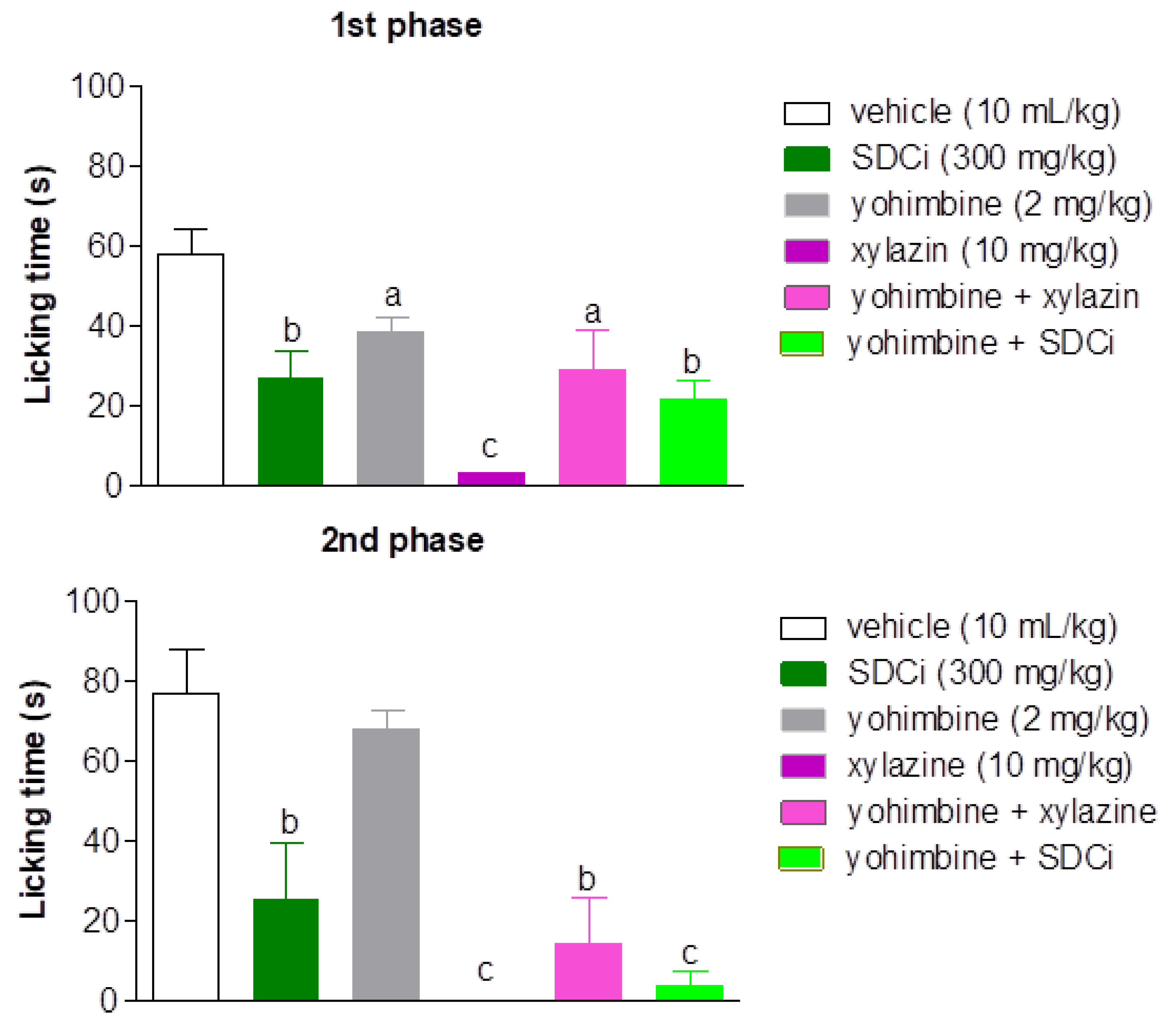

As shown in

Figure 5, all treatments significantly reduced the reactivity time to nociception in the first phase of the formalin test compared to the vehicle-treated group. Xylazine was more effective (94.2%) in reducing the licking time than yohimbine (33% reduction, p-value < 0.05), and was as effective as SDCi (53.2% reduction, p-value > 0.05). Co-administration of yohimbine and xylazine reversed approximately 88% of the agonist’s effect (p-value < 0.05), confirming its α-2 adrenergic antagonist effect. However, yohimbine did not significantly increase the licking time and thus did not reverse the SDCi effect when co-administered (p-value > 0.05).

Yoimbine (p.o, α-2 adrenergic antagonist) and xylazine (i.p, α-2 adrenergic agonist) were positive controls. First phase (0-5 min) and second phase (15-30 min). The results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 6) of the mice' nociception reactivity time expressed in seconds (s). ap-value < 0.05, bp-value < 0.01, and cp-value < 0.001, indicate the significance levels when compared to the vehicle group (0.9% saline solution, p.o), using the ANOVA test followed by the Newman-Keuls post-hoc test, at the 95% confidence interval.

2.8. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of SDCi: Antiedematogenic and Immunomodulatory Activities

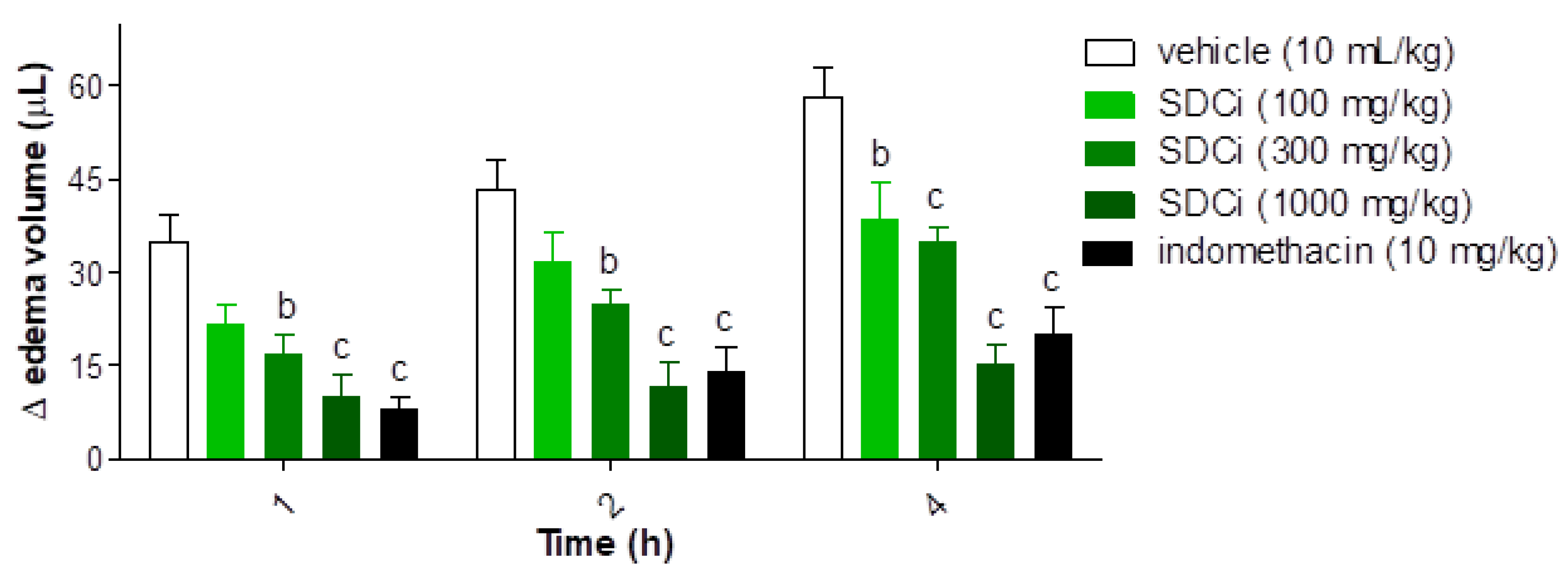

Figure 6 presents the results of an evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of SDCi concerning its antiedematogenic effects. After the administration of the inflammatory agent (carrageenan), a significant reduction in edema was observed in animals treated with SDCi at 300 mg/kg (54%, 42%, and 40%, respectively) and 1000 mg/kg (71%, 73%, and 74%, respectively) at 1, 2, and 4 hours (p-value < 0.001), as well as with indomethacin (10 mg/kg; 77%, 68%, and 66%, respectively; p-value < 0.001), compared to the vehicle group (35.0 ± 4.3 µL at 1 h; 43.3 ± 4.9 µL at 2 h; and 58.3 ± 4.8 µL at 4 h). SDCi at 100 mg/kg showed significant efficacy only at 4 hours (35% reduction in edema; p-value < 0.001) compared to the vehicle-treated group. No significant difference in edema reduction was observed between animals treated with SDCi (1000 mg/kg) or indomethacin at any of the time points evaluated.

Indomethacin (p.o) was used as a positive control. Results expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6), of the volume differences in μL between the paws of each animal in the different experimental groups. bp-value < 0.01 and cp-value < 0.001, indicate the significance levels when compared to the vehicle group (0.9% saline solution, p.o), using two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-test at 95% confidence interval.

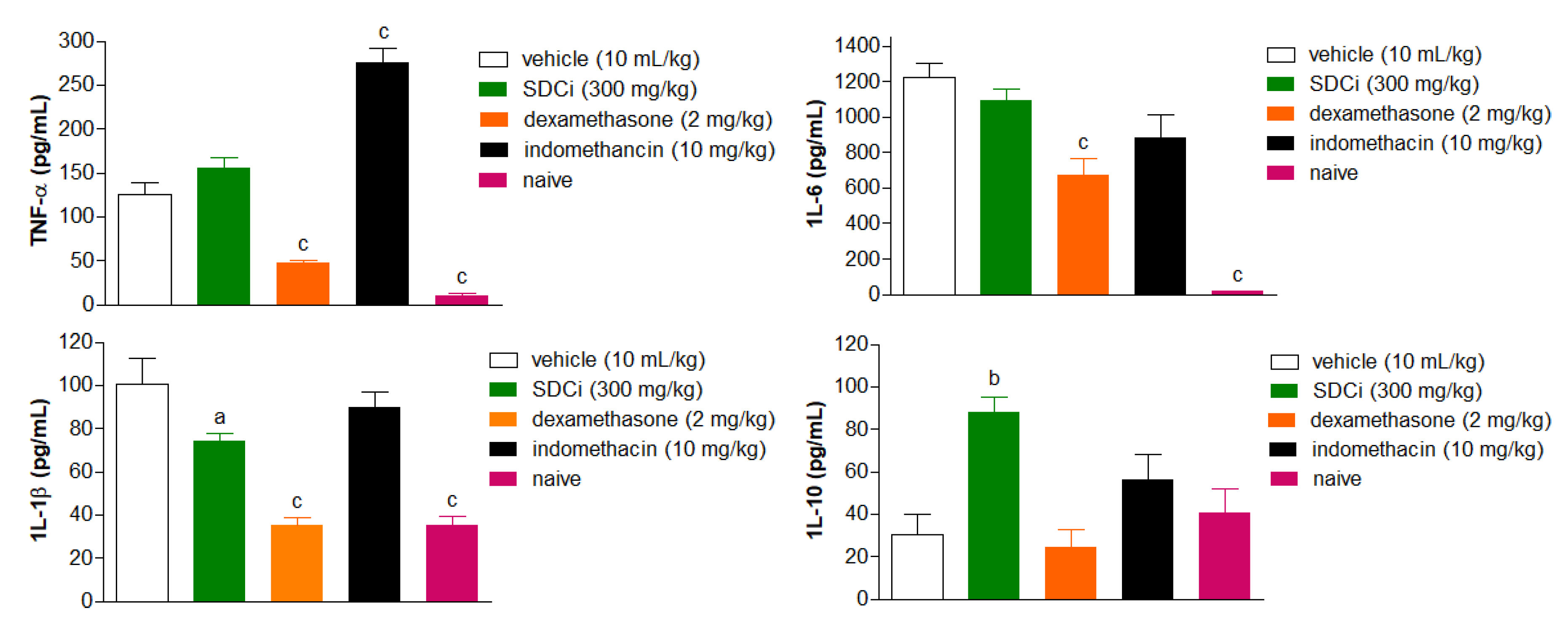

The carrageenan-induced paw edema test also allowed for the evaluation of SDCi's effects on the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) and the anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10). The results are shown in

Figure 7. At the peak of inflammation (4 hours), SDCi (300 mg/kg, p.o.) did not significantly reduce the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 compared to the vehicle-treated group. However, administration (p.o.) of SDCi (300 mg/kg) resulted in a 29% reduction in IL-1β levels and a twofold increase in IL-10 levels compared to the vehicle-treated group. In contrast to the effects observed with dexamethasone administration, SDCi did not reduce IL-1β levels to the same extent as the naive group (p-value > 0.05).

Dexamethasone (p.o) and indomethacin (p.o) were used as positive controls, and the naïve (not-inflamed) group as a negative control. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 random samples) of cytokine levels in carrageenan-induced edema in the different experimental groups. ap-value < 0.05 and cp-value < 0.001 indicate the significance level when compared to the vehicle-treated group (physiological saline, p.o.), using the ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post-test.

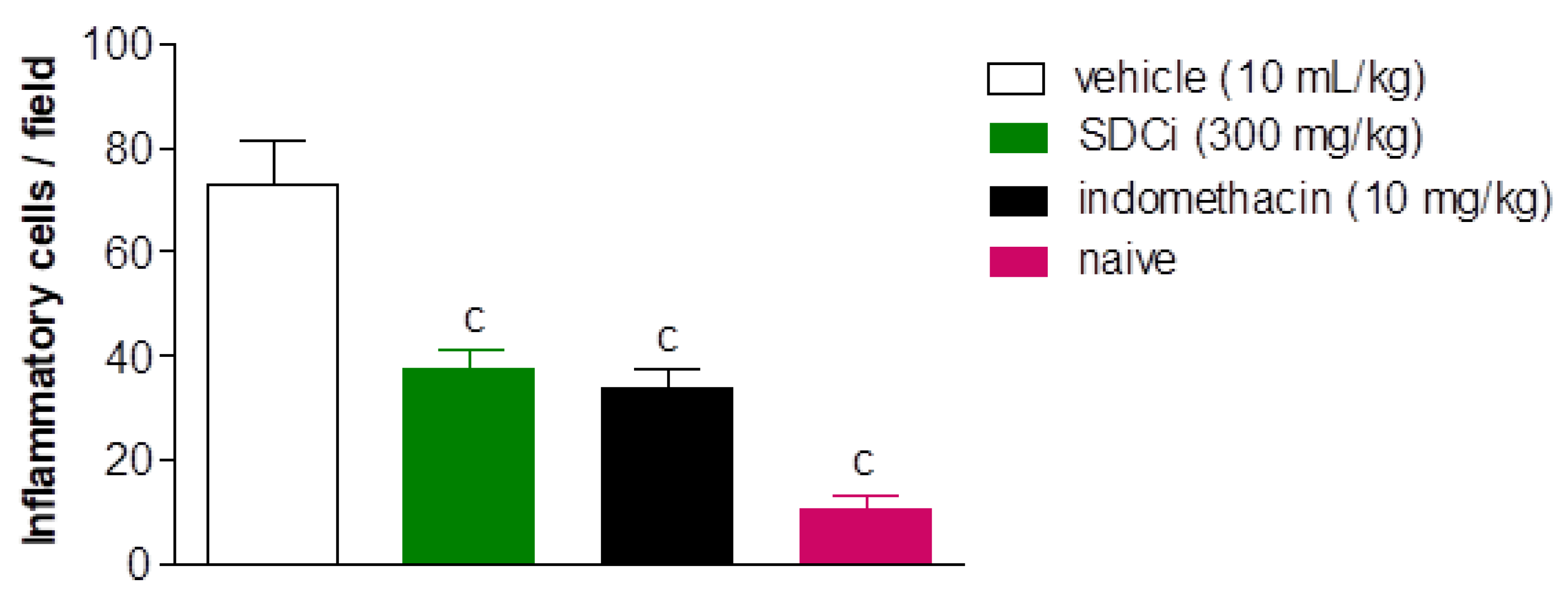

Figure 8 presents photomicrographs of histological analyses of mice paw tissue 4 hours after carrageenan injection. Tissue analysis of animals without inflammation (naive or non-inflammed) showed a normal dermis with minimal leukocyte presence (Fig. 8D). In contrast, animals that received carrageenan and were treated with the vehicle exhibited intense inflammation, characterized by the migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (likely neutrophils) into the tissue (Fig. 8A). Oral administration of 300 mg/kg of SDCi (Fig. 8C) or 10 mg/kg of indomethacin (Fig. 8B) significantly reduced leukocyte migration in the tissue.

Complementarily,

Figure 9 shows the count of inflammatory cells 4 hours after carrageenan-induced paw edema. Treatment (oral) with SDCi or indomethacin significantly reduced the PMN count by approximately 48.2% (37.9 ± 3.3 cells/field) and 53.1% (34.2 ± 3.3 cells/field), respectively, compared to the vehicle-treated group (73.1 ± 8.3 cells/field) (p-value < 0.001). Although the treatments with the extract or indomethacin did not reduce the number of inflammatory cells to the normal levels observed in the naive group (10.9 ± 2.7 cells/field), the obtained results are still relevant.

Indomethacin (p.o) was used as a positive control, and the untreated group as a negative control. The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6 random samples) of the amount of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in carrageenan-induced edema in the different experimental groups. cp < 0.001 indicates the level of significance when compared to the vehicle-treated group (physiological saline, p.o), using the ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post-test.

No statistically significant difference was observed between the groups treated with SDCi or indomethacin, suggesting that the extract exhibited anti-inflammatory activity comparable to the clinically validated positive control. However, it is important to note that indomethacin is associated with relevant adverse reactions and drug interaction, limiting its use in long-term treatments [

30,

31]. In this regard, SDCi may serve as a promising therapeutic option for patients requiring long-term management of inflammatory conditions, offering both antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects while potentially presenting lower toxicity.

3. Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of the phytochemical profile, in vitro antioxidant capacity, and in vivo antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory efficacy of a high-value intermediate phytopharmaceutical product derived from C. iguanaea. We investigated the mechanisms underlying its antinociceptive effects and anti-inflammatory activity of the extracts using experimental models not previously explored, including α-2 adrenoceptor involvement, and carrageenan-induced paw edema. This highlights the innovative nature of our work and advances the understanding of the therapeutic potential of C. iguanaea. Our findings represent a step forward in the development of safe and effective phytomedicines from this species, reinforcing its significance in Brazilian complementary medicine.

The reducing capacity of SDCi, determined by spectrophotometry and expressed as IC₅₀, is superior to that of several standardized dry extracts available on the Brazilian market. Comparatively, the IC₅₀ values of these extracts are as follows:

Hypericum perforatum (standardized in hypericin - 0.3%, IC

50 = 610 ± 20 μg/mL)

Ginkgo biloba (standardized in flavonoid glycosides - 24%, IC

50 = 560 ± 20 μg/mL),

Trifolium pretense (standardized in isoflavones - 8%, IC

50 = 720 ± 20 μg/mL),

Vaccinium macrocarpon (standardized in proanthocyanidins - 25%, IC

50 = 610 ± 20 μg/mL),

Crataegus oxyacantha (standardized in proanthocyanidins - 0.4 to 1%, IC

50 = 2390 ± 18 μg/mL),

Camellia sinensis (standardized in catechin and polyphenols - 30% and 50% respectively; IC

50 = 1930 ± 30 μg/mL),

Centella asiatica (standardized in saponins - 4 to 6.5%, IC

50 = 7610 ± 60 μg/mL), and

Aesculos hippocastanum (standardized in eascin - 1 to 4%, IC

50 = 2900 ± 204 μg/mL) [

26]. To interpret these results, it is necessary to consider that the higher the IC

50, the lower the reducing capacity of the extract.

Consistent with the trends observed in the reducing capacity results, the EI of SDCi demonstrates that its overall antioxidant capacity exceeds that of the standardized dry extracts of

C. oxyacantha (3.76 µA/V),

C. sinensis (0.68 µA/V),

C. asiatica (4.69 µA/V), and

A. hippocastanum (0.36 µA/V) [

26].

Arachidonic acid (AA) degradation products, including thromboxanes and prostaglandins, play a pivotal role in both inflammation and pain [

32,

33]. Prostaglandins primarily function to sensitize pain receptors to biomarkers, such as AA oxygenation products. A key step in the production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes involves the metabolism of AA into PGH

2 by the enzyme prostaglandin H

2 synthase, also known as COX-2 [

34]. During inflammation, COX-2 catalyzes the oxidation of AA, along with two O

2 molecules, to form PGG

2. This is followed by a peroxidase reaction in which PGG

2 loses two electrons to form PGH

2 [

35].

Spectroelectrochemical analysis of pain biomarkers has revealed that AA oxidation produces two anodic peaks, with potentials at 0.79 V (

Ep1a) and 0.52 V (

Ep2a). For PGG

2, an anodic peak was observed at 0.85 V (

Ep1a) [

35]. Given that SDCi exhibits lower

Epa values than those required for the oxidation of AA and PGG

2, and thus for the performance that would promote the redox stability? of these inflammatory markers, we hypothesize that its in vitro antioxidant capacity may correlate with its in vivo anti-inflammatory efficacy.

The phytochemical profile of SDCi likely underlies the remarkable antioxidant, antinociceptive, and anti-inflammatory activities reported here. Flavonoids, in particular, stand out for their ability to target multiple pathways that reduce inflammation, including the inhibition of COX-2 [

36]. From a structure-activity relationship perspective, the key requirement for flavonoids to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects is the presence of a C2-C3 double bond (C ring) and hydroxyl groups at the C3', C4', C5, and C7 positions on both the A and B rings of the flavonoid skeleton [

36]. Notably, the compounds corresponding to peaks 11 and 12 (

Table 1), luteolin heterosides, fulfill all these structural requirements. In contrast, the compounds associated with peaks 13 and 14 (

Table 1), apigenin heterosides, are missing the hydroxyl group at position C3.

Similarly, oxygenated and polyunsaturated fatty acids have been linked to the modulation of cell signaling pathways that regulate the production of inflammatory mediators and play a role in the initial mechanisms of nociception. This occurs through the inhibition of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6) and modulation of the enzymes COX and lipoxygenase [

37,

38].

Polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as octadecadienoic and octadecatrienoic derivatives, can directly interact with the cell membrane, altering the fluidity of immune cells and influencing the production of inflammatory mediators [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Additionally, these fatty acids can be converted into eicosanoids, which play a crucial role in the inflammatory response and pain regulation [

38,

42,

43]. These phytochemicals also function as antioxidants, helping to mitigate oxidative stress [

44], a key factor in the development of inflammation and pain. The antioxidant capacity may serve as an additional mechanism underlying the observed anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities. To confirm the role of these active compounds in these effects, further isolation and purification studies will be required.

The flavone glycoside 2-

O-pentosyl-8-

C-hexosyl-apigenin and the hydroxy fatty acid (9

S,10

E,12

Z,15

Z)-9-hydroxy-10,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid, which meet the chemical features of compounds 14 and 20 presented in

Table 1 (apigenin-

C-hexoside-

O-pentoside and hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid, respectively), have been previously identified in other

C. iguanaea leaf extracts of intermediate polarity that showcased meaningful bioactivities [

1,

8]. The recurrence of these compounds, regardless of the origin of the plant, solvent, and extraction method used, may justify their being considered analytical and pharmacological markers of the species. For this reason, the isolation and purification of these phytochemicals are already in the pipeline for future investigations by our research group.

It is worth understanding that the antinociceptive efficacy of SDCi at the tested doses (100, 300, and 1000 mg/kg) was, on average, 6.4, 2.7, and 2.4 times greater than that of CEE, respectively. In the acetic acid-induced abdominal writhing model, SDCi showed 7%, 19%, and 29% greater efficacy, respectively [

5]. In the formalin test, SDCi at 300 mg/kg reduced nociception in the inflammatory phase by 2-fold more than CEE (i.e., 39%) [

5]. However, in phase 1 (neurogenic nociception), SDCi showed a 21% reduction in antinociceptive efficacy compared to CEE (i.e., a 42% reduction) [

5]. These results suggest that the factors involved in the production cycle of SDCi (e.g., local and period of collection, extraction, concentration, and drying processes) may be more favorable for preserving its anti-inflammatory efficacy in vivo than its central nervous system activity. This could be related to the qualitative and quantitative phytoconstituents present in the extract. Based on the comparison of efficacy observed in the first and second phases of the formalin test, we hypothesize that the antinociceptive effect observed in the abdominal writhing test is more dependent on anti-inflammatory activity than on central action.

Given that the results obtained for SDCi are even more promising than those of CEE in the acetic acid-induced abdominal writhing test and the second phase of the formalin test, despite small differences in sample sizes, it is reasonable to conclude that the mechanisms underlying the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of CEE are similar to those of SDCi. It is reasonable to assume that the spray-drying process did not compromise the preclinical efficacy of the extract.

A reasonable explanation for the observed effect in the hot-plate test could lie in the difference in the pharmacokinetics of the phytochemicals in SDCi and morphine. Morphine has a relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), which may account for the reduction in its effectiveness over time following a single administration [

45]. On the other hand, SDCi may contain active compounds with a longer half-life. The phytochemical profile of SDCi could include a combination of bioactive compounds that act on multiple molecular targets, such as balancing inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, preventing neurotransmitter degradation, or prolonging antinociceptive signaling through other pathways. This multifaceted action may result in a more stable and long-lasting antinociceptive effect. The prolonged action of SDCi, with minimal reduction over time, suggests its potential clinical use as an alternative or adjunct to opioids, particularly in cases where tolerance or abuse are concerns.

For comparison, using the same experimental model, the anti-edematogenic activity of SDCi at the intermediate dose (300 mg/kg) was 20% greater than that of the spray-dried, standardized extract of

Phyllanthus niruri L. (Phyllanthaceae), commonly known as 'stone breaker' ('quebra-pedra' in Portuguese), which is traditionally used in Brazilian complementary medicine for treating urolithiasis [

46]. Further comparisons were not feasible due to differences in the doses tested and the experimental protocol employed.

The trends observed while assessing the involvement of adrenoceptors in the antinociceptive activity of SCDi remained consistent in the inflammatory phase of the formalin test, except for the fact that, contrary to previous reports [

47,

48], yohimbine did not reduce the licking time. These results further reinforce the reproducibility of the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory efficacy of SDCi and suggest that its antinociceptive activity does not depend on α-2 adrenergic receptors. Therefore, the extract may exert a broader action, possibly modulating other receptors or pathways, such as prostaglandin receptors and antioxidant systems, which are not affected by the presence of yohimbine. Other potential mechanisms, such as the involvement of cannabinoid receptors, remain to be investigated.

Regarding the set of experiments conducted to confirm the anti-inflammatory efficacy of SDCi, the results obtained with the positive controls align with the known mechanisms of action of the drugs used. Dexamethasone, a corticosteroid, effectively modulates the production of inflammatory cytokines [

49]. In contrast, indomethacin, an NSAID, although effective in reducing prostaglandins, does not directly reduce the level of IL-6 and IL-1β and may even provoke additional inflammatory responses due to compensatory effects. [

50,

51].

The cytokines studied here were selected because they play critical roles in regulating and advancing the inflammatory process, orchestrating the body’s immune response at different stages of inflammation. TNF-α is one of the first cytokines released in response to infection or injury. It induces fever, increases the production of acute-phase proteins by the liver, and triggers apoptosis in infected or damaged cells. Additionally, TNF-α enhances vascular permeability and enhances the entry of immune cells and proteins into the affected tissue, potentially leading to inflammatory edema. Furthermore, TNF-α amplifies the inflammatory response by stimulating the release of other cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6, thus sustaining a cycle of immune activation until the inflammation is resolved [

52,

53].

The increase in TNF-α levels observed in the group treated with indomethacin (119%, Fig. 7) can be attributed to a combination of factors, including the disruption of the balance of inflammatory mediators and the effect of this NSAID on the kinetics of cytokine release [

54]. This paradoxical effect exemplifies the complexity of the inflammatory response and highlights how NSAID treatments can, in some cases, trigger nonlinear immune reactions. It emphasizes the importance of carefully considering the effects of anti-inflammatory drugs across different phases and types of inflammation [

51,

55].

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a significant role in the initial inflammatory response. It is produced by cells like macrophages and lymphocytes in response to infection or tissue injury. IL-6 promotes the activation of lymphocytes, the differentiation of T and B cells, and stimulates antibody production. It also activates endothelial cells, increasing vascular permeability to facilitate the recruitment of immune cells. Furthermore, IL-6 is essential for inducing the production of acute-phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein, by the liver, which are key markers of inflammation [

52,

53].

Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine in the innate immune response, known for inducing fever and increasing pain sensitivity. It is released primarily by macrophages and activates the production of other inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, thereby amplifying the inflammatory response. IL-1β also enhances the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, facilitating the recruitment of immune cells to the site of inflammation. Additionally, it plays a role in tissue remodeling processes following injury [

52,

53].

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that plays a crucial role in regulating the intensity of the inflammatory response, helping to prevent excessive tissue damage. It inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, thereby promoting the resolution of inflammation. IL-10 also reduces the activity of macrophages and dendritic cells, limiting antigen presentation and T-cell responses, which aids in restoring homeostasis after the acute phase of inflammation [

52,

53].

The balance between pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines is crucial for an effective inflammatory response. It ensures that the response is neither insufficient nor excessive, as uncontrolled inflammation can lead to tissue damage and contribute to the development of chronic inflammatory diseases, including diabetes mellitus, obesity, and cancer [

52,

53].

Therefore, the anti-inflammatory activity of SDCi appears to be primarily mediated by its modulatory effects on IL-1β and IL-10. By downregulating IL-1β and upregulating IL-10, SDCi may effectively regulate the inflammatory response, preventing its progression and promoting resolution which indicates an important therapeutic strategy. Notably, the extract's lack of impact on TNF-α and IL-6 suggests that it may operate through distinct pathways and cytokines. These findings suggest a targeted immunomodulatory effect, controlling inflammation while promoting IL-10 production, which may aid in its resolution.

Across all in vivo experiments assessing antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities, no adverse effects or animal deaths were observed, indicating the extract's safety at the tested doses. This finding is particularly significant. Since SDCi showcased dual action on both nociceptive and inflammatory pathways, it could serve as a potential therapeutic agent for treating a wide range of conditions, including chronic pain syndromes, arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. These conditions are often difficult to manage with current pharmacotherapies due to the risk of side effects and tolerance [

56,

57]. Therefore, the low toxicity profile of SDCi may offer an important advantage in these therapeutic areas.

While these results are promising, some limitations should be considered. The preclinical in vivo efficacy of SDCi may not fully translate to human responses, necessitating further clinical studies. To bridge this gap, various dose conversion strategies between animals and humans could help estimate a safe starting dose, ensuring safety and tolerability in phase I clinical trials [

58,

59]. Future research should focus on investigating its pharmacokinetic profile and drug interaction mechanisms (e.g., competitive hepatic metabolism) in animals. This could provide important insights into its therapeutic potential and safety before undergoing clinical trials. Additionally, as

C. iguanaea is a native species, agronomic studies on domestication and seasonality are essential to ensure a consistent supply of high-quality plant material for large-scale product development.

A key challenge in analytical standardization remains the precise identification of phytochemicals in the extract, particularly the sugar moieties (hexoses and pentoses) that comprise the heterosides. Without a well-defined analytical marker for unequivocal quantification via HPLC-PDA, quality control, and pharmacokinetic studies remain limited. Currently, the electrochemical profile and the total content of polyphenols, flavonoids, and phytosterols serve as primary indicators of the extract's physicochemical quality.

4. Methods and Materials

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Dexamethasone elixir 0.1 mg/mL from Geolab® (Anápolis, GO, Brazil); alprazolam tablets (2mg) from Eurofarma (São Paulo, SP, Brazil); glacial acetic acid (99,7%) from Alphatec (Macaé, RJ, Brazil); indomethacin, ʎ-carrageenan, rutin (95%), β-sitosterol, and DPPH from Sigma Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA); morphine sulfate injectable solution (10 mg/mL, Dimorf®) from Cristália (Itapira, SP, Brazil); yohimbine from Infinity® Pharma (Campinas, SP, Brazil); xylazine hydrochloride 2% injectable solution (Xilazin®, Syntec do Brasil, Tamboré, SP, Brazil); ethanol from Synth® (Diadema, SP, Brazil); gallic acid from Êxodo Científica (Sumaré, SP, Brazil); chloroform from Cromato (Diadema, SP, Brasil); Na2CO3 from Sciavicco (Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil); AlCl3 from Neon (Suzano, SP, Brazil); Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and acetic anhydride from Dinâmica (Indaiatuba, SP, Brazil); and leucine from Jiangsu Xinhanling Biological Engineering (Xinyi City, Jiangsu, China) were used in this research. All the other chemicals were of analytical grade.

4.2. Animals

The assays were conducted using adult male Swiss albino mice weighing between 30 and 35 g, provided by the Department of Natural Sciences mouse breeding facility at the Federal University of São João Del-Rei (NUCAL/DCNAT/UFSJ). The animals were kept under controlled temperature (between 21-22°C) and lighting (12-hour light/dark cycle), with free access to water and food. All experimental protocols were performed in accordance with the principles of Law 11,794 of October 8, 2008, Decree 6,899 of July 15, 2009, and the guidelines established by the National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation, after approval by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals of the Federal University of São João Del-Rei [(protocol CEUA/UFSJ No. 6135130223, ID 000283)].

4.3. Plant Material

The access to the genetic heritage of C. iguanaea was duly registered in SisGen (National System for the Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge) under code A908B3F, in compliance with Brazilian Law No. 13,123/2015. Leaf samples were collected on March 27 and April 2, 2022, during early autumn in Brazil, from the third and fourth nodes of plants located in a modified "Cerrado" area in the rural municipality of São Sebastião do Oeste, Minas Gerais, Brazil (coordinates: 20°16'30.9"S, 44°56'40.8"W and 20°19'21.2"S, 45°03'24.1"W). Dr. Andréia Fonseca Silva carried out botanical identification, and a voucher specimen (PAMG 59090) was deposited at the PAMG Herbarium of EPAMIG. The harvested leaves were oven-dried at temperatures below 40°C using natural air circulation until constant weight was achieved, followed by pulverization in a Willey-type knife mill to yield the powdered plant material.

4.4. Obtaining the Hydroethanolic Fluid C. iguanaea Extract

The hydroethanolic fluid extract of C. iguanaea (HECi) was obtained by percolating 2 kg of plant material with a 70% hydroethanolic mixture (w/w) as the solvent. The percolation flow rate was 0.7 mL/min. Thin-layer chromatography coupled with ultraviolet/visible detection was used to monitor the leaching of bioactive compounds (i.e., polyphenols, flavonoids, and phytosterols) from the plant material during the extraction process. The extraction process was terminated when none of these markers were detected in the chromatographic analyses.

For polyphenol detection, elution was performed with ethyl acetate:acetic acid:water (100:11:10). Revelation was done by spraying the chromatographic plate with a natural products reagent (1% diphenylborinoxyethylamine in methanol), followed by polyethylene glycol 4000 in 5% ethanol, and reading at 365 nm. For terpene detection, the eluent was toluene: ethyl acetate (93:7), and the revelator was 1% vanillin in ethanol, followed by a 10% ethanolic solution of sulfuric acid, and heating at 100°C for 10 minutes. The HECi was concentrated in a rotary evaporator (RV 10 digital, IKA do Brazil, Campinas, SP, Brazil) under reduced pressure (-600 mmHg) at a temperature below 40°C to adjust the solid and ethanol content to levels suitable for spray drying, ensuring satisfactory yield and safety

4.5. Obtaining and Standardizing the Spray-Dried C. iguanaea Hydroethanolic Leaf Extract

4.5.1. Spray Drying

For the drying of HECi and obtaining the spray-dried C. iguanaea hydroethanolic leaf extract (SDCi), a spray dryer (model MDS 1.0, Labmaq, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil) was used, featuring a co-current flow regime, an evaporation capacity of up to 1.0 L/h, and a maximum operating temperature of 180°C. The system consisted of a peristaltic pump, a dual-fluid top pneumatic atomizer with an internal diameter of 1.2 mm, and a cylindrical drying chamber with a 160 mm diameter and 645 mm length, made of polished stainless steel with a sanitary finish.

The drying air was supplied by a compressor electrically heated with the temperature regulated by a digital thermostat. The drying conditions were as follows: an atomizing air flow rate of 40 L/min, a drying air flow rate of 405 L/min, a drying air temperature of 120°C, an extract feeding rate of 0.3 L/h, an atomizing air pressure of 6 bar, and a feed extract mass of 100 g. Leucine was used as a drying adjuvant (45% w/w based on the solid content of the sample). The drying process was initialized with distilled water to reach thermal equilibrium. The dried extract was separated from the air with a stainless-steel cyclone, collected in a borosilicate glass container, weighed, and stored in sealed flasks, sheltered from light and moisture, in desiccators at room temperature (24 ± 2°C) before and after characterization.

4.5.2. Quantitative Analysis

The total phenolic content (TPc), total flavonoid content (TFc), and total phytosterol content (TPSc) were determined using widely established spectrophotometric methods, specifically the Folin-Ciocalteu [

60], AlCl

3 [

61], and Liebermann-Burchard [

62] colorimetric reactions, respectively. Additional experimental details are provided in the Supplementary Material. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are expressed on a dry basis (mg/g) as mean ± standard deviation (SD)

4.5.3. UFLC-DAD-MS Analysis

The phytochemical profile of the SDCi was evaluated using the hyphenated technique of UFLC-DAD-MS [

63]. The phytochemical profile of the SDCi was evaluated using the hyphenated technique of UFLC-DAD-MS [

63]. The SDCi was solubilized in a 7:3 v/v mixture of methanol and water (1 mg/mL), filtered through a 0.22 μm PTFE membrane (Millex, Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA), and 4 μL were injected into a high-speed liquid chromatography system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) coupled with a DAD and a high-resolution MS with an electrospray ionization source (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA).

A Kinetex C18 chromatography column (150 mm × 2.2 mm, 100 Å; 2.6 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, California, USA) was used, protected by a pre-column and maintained at 50°C. The gradient elution profile used as the mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and ultrapure water with 0.1% formic acid. The applied elution gradient was as follows: 0-2 min, 3% B; 2-25 min, 3-25% B; 25-40 min, 25-80% B; 40-43 min, 80% B, followed by 5 minutes of washing and column reconditioning. The flow rate was 0.3 μL/min, and the analyses were monitored between 240-800 nm and acquired in both positive and negative ion modes (m/z 120-1200, collision energy 45-65 V). Compound identification was performed through UV spectra, mass spectra, and fragmentation profiles, compared with literature data.

4.5.4. In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity

For the evaluation of reducing capacity, the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging method [

64] was used with adaptations for a 96-well microplate format (Araújo et al., 2013b). The redox profile of SDCi was evaluated using DPV and SWV electrochemical techniques [

8]. The DPV analysis made it possible to determine the EI of the sample. Further experimental details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

4.6. In Vivo Evaluation of Antinociceptive Activity

4.6.1. Rotarod Test

Initially, the mice were subjected to the rotarod test (Insighit

®, Brazil, 16 rpm) 24 hours before the experiment, and those that did not remain on the apparatus for two consecutive 60-second sessions were excluded. The selected animals were randomly assigned to five distinct groups (n = 6), receiving treatment with 0.9% saline solution (vehicle, 10 mL/kg), SDCi (100, 300, and 1,000 mg/kg), or alprazolam (2 mg/kg) via oral administration (p.o.). The time each animal remained on the rotarod (Insighit

®, Brazil) set at 16 rpm was recorded at 0.5, 1, 2, and 2.5 hours after administering the treatments and controls [

66]. The results were expressed as mean ± SEM. The percentage of reduction in the time spent on the rod was calculated using

Equation 1:

4.6.2. Acetic Acid-Induced Abdominal Writhing Test

The mice were divided into five distinct groups (n = 6) and treated orally (p.o.) with vehicle (10 mL/kg), or SDCi (100, 300, and 1000 mg/kg) or indomethacin (10 mg/kg). One hour after treatment, each animal received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 1% acetic acid (v/v, 10 mL/kg) and was placed on a flat surface under a glass funnel for 30 minutes to count abdominal writhing. These were considered as a wave of contraction and stretching of the lateral abdominal wall, sometimes accompanied by trunk twisting followed by the extension of the hind limbs [

63]. The results were expressed as mean ± SEM. The percentage of inhibition of writhing was calculated using

Equation 2:

4.6.3. Formalin Test

The mice were divided into six distinct groups (n = 6) and treated orally (p.o.) with vehicle (10 mL/kg), or SDCi (100, 300, and 1,000 mg/kg), or indomethacin (10 mg/kg), or intraperitoneally (i.p.) with morphine (7.5 mg/kg). One hour after oral treatments or 30 minutes after intraperitoneal treatments, 20 μL of 2.5% (v/v) formalin was injected into the left hind paw of the animal. Immediately after the injections, the animals were placed in acrylic boxes with white bottoms to allow observation of the nociceptive response.

The paw-licking time (s) was measured over 30 minutes after the inflammatory agent application. The first phase (0-5 min), known as neurogenic nociception, begins immediately after the injection of the inflammatory agent due to the activation of nociceptors. The second phase (15-30 min) is considered inflammatory nociception caused by the intense release of inflammatory mediators, increasing nerve fiber sensitization [

63]. The results were expressed as mean ± SEM. The percentage of inhibition in nociception was calculated using

Equation 3:

4.6.4. Hot-Plate Test

Mice were previously selected (24 hours before the test), and those with a latency time greater than 15 seconds in response to the thermal stimulus (metal plate heated to 55±0.5°C; Insight

®, Brazil) were excluded. The animals (n = 8) were treated orally with vehicle (10 mL/kg), SDCi (100, 300, and 1,000 mg/kg), or intraperitoneally with morphine (7.5 mg/kg). The mice were individually placed on the metal plate (55 ± 0.5°C) 1, 2, and 3 hours after treatment. The latency time of the animals (the period during which the animal remained without jumping, shaking, biting, or licking its paws) was timed. A cutoff time of 30 seconds was established to prevent tissue damage [

63]. The results were expressed as mean ± SEM. The percentage of increase in the latency time to the thermal stimulus was calculated using

Equation 4:

4.6.5. Investigation of the Involvement of α-Adrenergic Receptors

To investigate the role of α-2 adrenergic receptors in the modulation of the antinociceptive action of the SDCi, the formalin test was performed using yohimbine (antagonist) and xylazine (agonist) [

47,

48,

67]. Six experimental groups of mice (n = 6) were treated with: i) vehicle (10 mL/kg, p.o.), ii) SDCi (300 mg/kg, p.o.), iii) yohimbine (5 mg/kg, p.o.), iv) xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.), v) yohimbine (5 mg/kg, p.o.) + xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.), and vi) yohimbine (5 mg/kg, p.o.) + SDCi (300 mg/kg, p.o.).

Sixty minutes after oral treatments or thirty minutes after intraperitoneal treatments, 20 μL of formalin was injected into the plantar surface of the left hind paw of the animal, licking time was recorded for 30 minutes, covering the first (0–5 min) and second (15–30 min) phases of the test. The results were expressed as the mean ± SEM of the licking time in seconds (s). The percentage increase in the latency time to the nociceptive stimulus was calculated using Equation 3.

4.7. In Vivo Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4.7.1. Carrageenan-Induced Paw Edema Test

The groups of mice (n = 6) were treated orally with vehicle (10 mL/kg), SDCi (100, 300, and 1,000 mg/kg), or indomethacin (10 mg/kg). One hour after the treatments, the animals received a subplantar (s.p.) injection of 30 μL of carrageenan solution (400 µg/paw) into the left hind paw. Edema formation was evaluated by measuring the difference in volume between the paws using a plethysmometer (Insight

®, Brazil) at 1, 2, and 4 hours after the carrageenan injections, with a baseline reading taken before the treatments [

63]. The results were expressed as the mean ± SEM of the paw volume (μL). The percentage of edema inhibition was calculated using

Equation 5:

Wherein, Vc is the mean volume of the paw where carrageenan was administered and Vs is the mean volume of the paw where saline was administered.

4.7.2. Cytokine Measurement

The carrageenan-induced paw edema assay was also used to quantify the pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) and the anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10). In this case, animals (n = 6 per group) were treated with vehicle (10 mL/kg, p.o.), SDCi (300 mg/kg, p.o.), indomethacin (10 mg/kg, p.o.), or dexamethasone (2 mg/kg, p.o.) one hour before the subplantar injection of carrageenan solution into the paws. After 4 hours of edema induction, the animals were euthanized. The plantar cushions were carefully excised using a scalpel, weighed, and homogenized in 1 mL of cytokine extraction solution containing protease inhibitors and bovine serum albumin (1 mL of solution per 50 mg of tissue). Plantar cushions from animals (n = 6) where inflammation was not induced (naïve or non-inflamed group) were also collected. The samples were immediately triturated and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 8 minutes. The supernatants were then collected and stored at -80 °C until further use [

68].

The cytokine measurements were performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits specific to each cytokine, purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance was read at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer. Measurements were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as the mean ± SEM (pg/mL).

4.7.3. Histopathological Analysis

The edema induction and treatments were performed under the same conditions described in the previous section. After collection, the plantar footpad tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde solution for 24 hours, dehydrated in ascending graded ethanol solution (70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 3 changes of 100%) for 3 hours, dewaxed in xylene for 3 hours, and embedded in paraffin wax. 5 µm sections were cut using an RM2245 microtome (Leica do Brasil Importação e Comércio Ltda., São Paulo, SP, Brazil), stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined under an optical microscope.

Digital images were captured at 400x magnification, and inflammatory infiltrates were evaluated using ImageJ software version 1.44 (Research Services Branch, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Inflammatory cells were counted in six fields per case/slide, and results were expressed as the mean ± SEM of the number of inflammatory cells per field.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

The differences between the groups were detected by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey or Newman-Keuls post-tests, or by two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post-test. Differences were considered significant when p-value < 0.05 at a 95% confidence interval. The statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8.0® software (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). Regression and linear correlation analyses were conducted using Excel 2016 version (Microsoft Inc., USA).