1. Introduction

To optimize treatment outcomes, the World Health Organization strongly recommends initiating ART on the same day as an HIV diagnosis, a strategy that improves both immediate and long-term health outcomes for patients [

1,

2]. However, despite the potential benefits, the immediate initiation of ART can pose challenges to treatment adherence and retention in care if patients do not receive sufficient support during the initiation process. This lack of support may hinder patients' ability to effectively engage with their treatment regimen [

3].

Patient navigation is critical in addressing these challenges, as it integrates both relational and functional aspects of care to enhance patient outcomes [

4]. The functional aspects of patient navigation include coordinating healthcare services and removing barriers to care, essential for ensuring continuous and accessible treatment [

5,

6]. Moreover, the relational dimension of patient navigation focuses on establishing a trusting relationship between the navigator and the patient, which is crucial for encouraging ongoing engagement in care. As noted by Cook et al. [

7], this emotional support fosters a strong emotional bond integral to the patient’s overall experience and adherence to treatment.

According to DiMatteo [

8], this relationship support plays a crucial role in enhancing the psycho-social wellness and adherence to the care of clients. Perlman [

9] described a connection as an emotional bond with another person marked by unity, understanding, caring, admiration, and acknowledgment. Often more intense than the usual patient-provider contact, the navigator-client relationship can foster trust and offer emotional support [

10]. Although patient navigation has been demonstrated to enhance health outcomes in several chronic conditions, its effect on retention in care and suppressing the HIV viral load among newly diagnosed persons living with HIV is not fully understood. The study aims to use a randomized controlled trial to analyze how patient navigation, as an intervention, influences treatment adherence and virological outcomes in this specific population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

In this randomized controlled experiment (Study ID: ISRCTN99248870), two groups were compared: the exposed group (using patient navigation), which consisted of same-day ART initiators, and the control group, which used the standard operating procedure. The exposed group began antiretroviral medication (ART) on the same day as HIV diagnosis. Adolescents aged 12 to 17 and adults aged 18 and up with WHO illnesses stage 1 or 2 were among the participants' selection criteria. Participants had to be mentally competent to give informed permission, have a recent HIV diagnosis, or have a prior HIV diagnosis but have never been connected to treatment. From January 2023 to August 2023, participants were gathered from HIV Testing Services units in three busy facilities in the O.R. Tambo district: Flagstaff Clinic, Mthatha Gateway, and Tsolo Clinic. Preparatory services, HIV testing, and post-test counseling were all part of the recruitment process. After giving informed consent, participants also had opportunistic infection screening and blood drawn for baseline tests (hepatitis B antigen, creatinine clearance, and CD4 count). Patients who had previously received ART were pregnant or nursing, lived outside of the O.R. Tambo district, planned to switch treatments during the study period, or chose not to participate for personal reasons, were not allowed to enroll.

2.2. Approach

This study used the 4R systems engineering approach (right information and treatment to the right patient at the right time) and project management discipline concepts to create care sequence templates that act as patient-centered project plans for patients and their care team.[

11] Furthermore, 4R was utilized in patient guidance using the following 5 strategies [

12]:

Patient needs assessment: The navigator thoroughly assessed the patient's medical history, socioeconomic determinants of health, and any barriers to care.

Care plan development: Using the assessment, a personalized care plan was constructed, defining the "right" treatment options, information, and timing for each patient.

Coordination and communication: Patient navigators worked closely with healthcare personnel in the facility, community teams, and the patient to ensure that treatment was coordinated seamlessly

Monitoring and adjustments: Regular follow-ups are undertaken to track progress, identify new barriers, and make appropriate changes to the treatment plan.

2.3. Procedure

After obtaining the patients' signed informed consent, the researcher performed a screening evaluation to determine the study exclusion criteria. On the day of the HIV test, eligible individuals were then enrolled and assigned at random. With allocation concealment, participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either standard ART or same-day ART commencement using a computer-generated random-number list. The researcher recruited participants and assigned them to study groups. However, the study supervisor, site staff, and participants were not blinded to the group assignments.

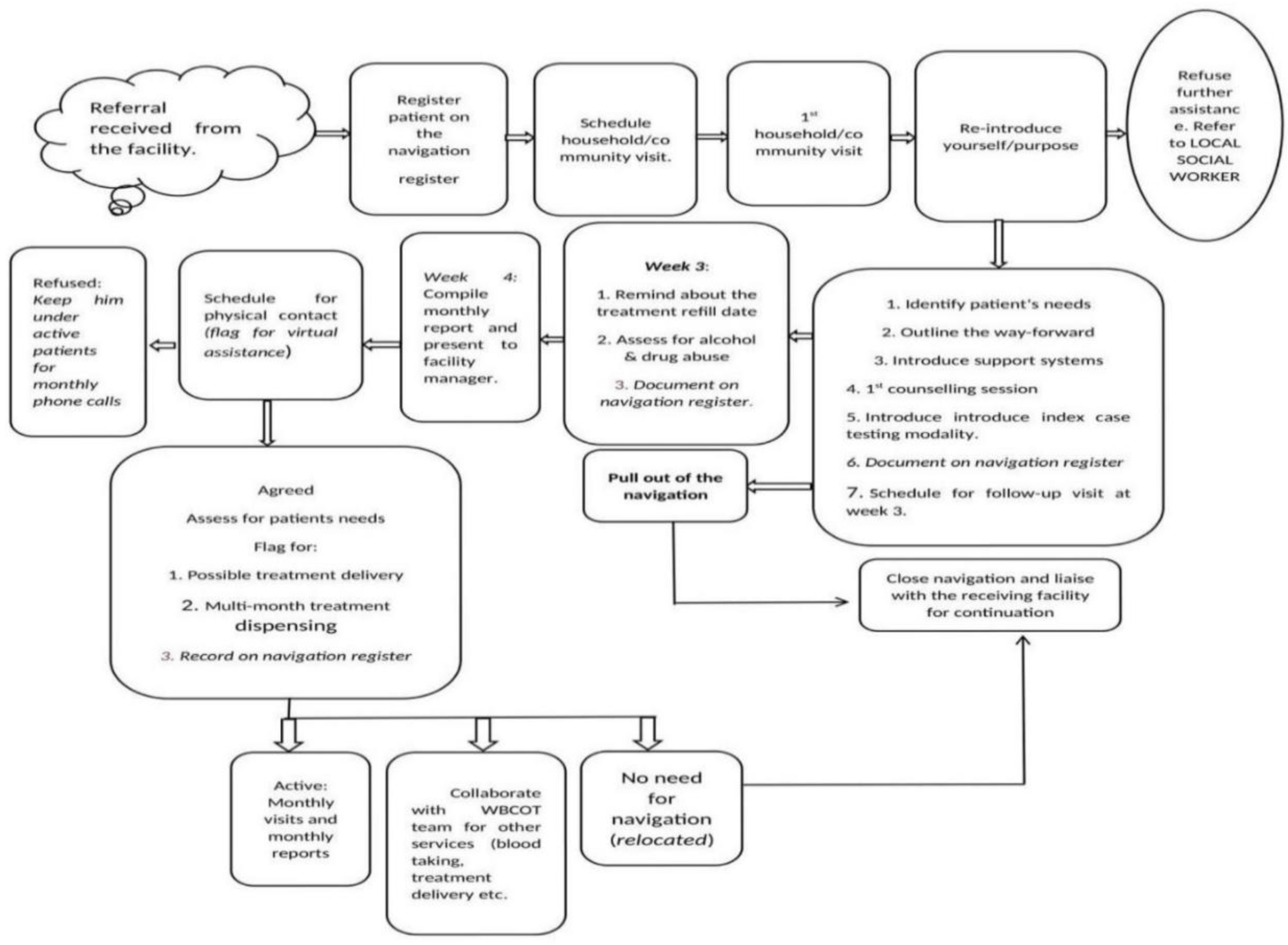

After being initiated on HIV treatment, a patient is referred to a patient navigator for coaching. The navigator seeks verbal consent to visit the patient at home or in their community, and they schedule a meeting for Day 5 of treatment (

Figure 1). During this meeting, the navigator introduces themselves, explains their role, and connects the patient with local support systems, such as Social Auxiliary Workers and community outreach teams. However, when the patient refused coaching, the navigator would refer the patient to a social worker for further management (

Figure 1). For those patients willing to participate, the navigator would assess their needs, provide disease and treatment education, and emphasize the importance of index case testing to help them disclose their diagnosis to loved ones and refer them for testing.

The patient and navigator scheduled a follow-up meeting for Week 3 of treatment. During this meeting, the navigator reminds the patient about their treatment collection date and the assessment of alcohol and drug abuse (

Figure 1). In addition, for patients who were transferred out to other facilities within 3 weeks, the navigation process was discontinued, and the receiving facility was phoned, and the patient was handed over. After four weeks of treatment, the navigator compiles a report and presents it to the facility's operational manager. For patients who showed no interest in further one-on-one sessions after 1-month, monthly telephonic conversations with the patient navigator were offered. Over the next 6 months, the navigator continues to support the patient, reminding them of treatment appointments, screening for substance abuse, and documenting all interactions. The navigator ensures that blood is collected from the patient for viral load testing and that the patient's viral load is reviewed the following month. In month 7, if viral load is suppressed, the patient is enrolled in a multi-month medication dispensing program called Central Chronic Medicine Dispensing Distribution (CCMDD). If the patient relocates, the navigator ensures a smooth transition of care to the new facility. Moving forward, the navigator and patient agree on a plan for ongoing engagement, including virtual or telephonic check-ins. The navigator continues to monitor the patient's progress, flagging those who miss appointments and assisting with treatment delivery.

Retention in care, defined as keeping an HIV-1 RNA level less than 50 copies/mL six months after HIV testing, was the study's initial result. Regular attendance at the 6-month appointment was regarded as a sign of retention, but nonattendance was categorized as a loss to follow-up (LTFU). Medical data or phone reports from family members were used to determine deaths. The study team updated the participant file upon learning of any deaths, and the results were entered into Tier.net, an electronic registry authorized by the SADoH. Transfer transfers or transfer-outs were identified by verifying that the participant received care at a new location. The following were secondary outcomes: retention in care with HIV-1 RNA <1,000 copies/mL at 6 months post-testing, death rate, and loss to follow-up.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Stata v18 software (StataCorp, Texas) was used to analyze the de-identified laboratory, clinical, and demographic data after it had been imported into an Excel spreadsheet. The retention rate with HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL (primary outcome), retention with HIV-1 RNA <1,000 copies/mL, retention without HIV-1 RNA, and mortality (secondary outcome) at 6 months were compared using the chi-square test. The risk difference (RD) was displayed along with 95% CIs for unadjusted instances, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.5. Ethical Consideration

The Eastern Cape Health Research Committee (protocol number EC_202210_008) and the Institutional Ethics Committee of Walter Sisulu University's Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (protocol code 027/2022) gave their approval to the study, which was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Each participant was thoroughly told about the purpose and difficulties of our research before signing an informed consent form to participate in the study. Each participant was given a unique code used in place of their name to maintain secrecy.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, Clinical, and Behavioral Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of participants' demographic and clinical characteristics in the standard group (n=72) and the navigation group (n=70). The results show significant differences in terms of gender (P=0.0173), marital status (P=0.001), and place of residence (P=0.0173). However, age, education, disease stage, BMI, and CD4 cell count did not differ significantly between the groups. Additionally, there were significant behavioral differences between the two groups, particularly in smoking status and alcohol consumption, with the control group exhibiting a significantly higher proportion of smokers (P=0.002) and drinkers (P=0.019).

3.2. Impact of Patient Navigation on Retention in Care

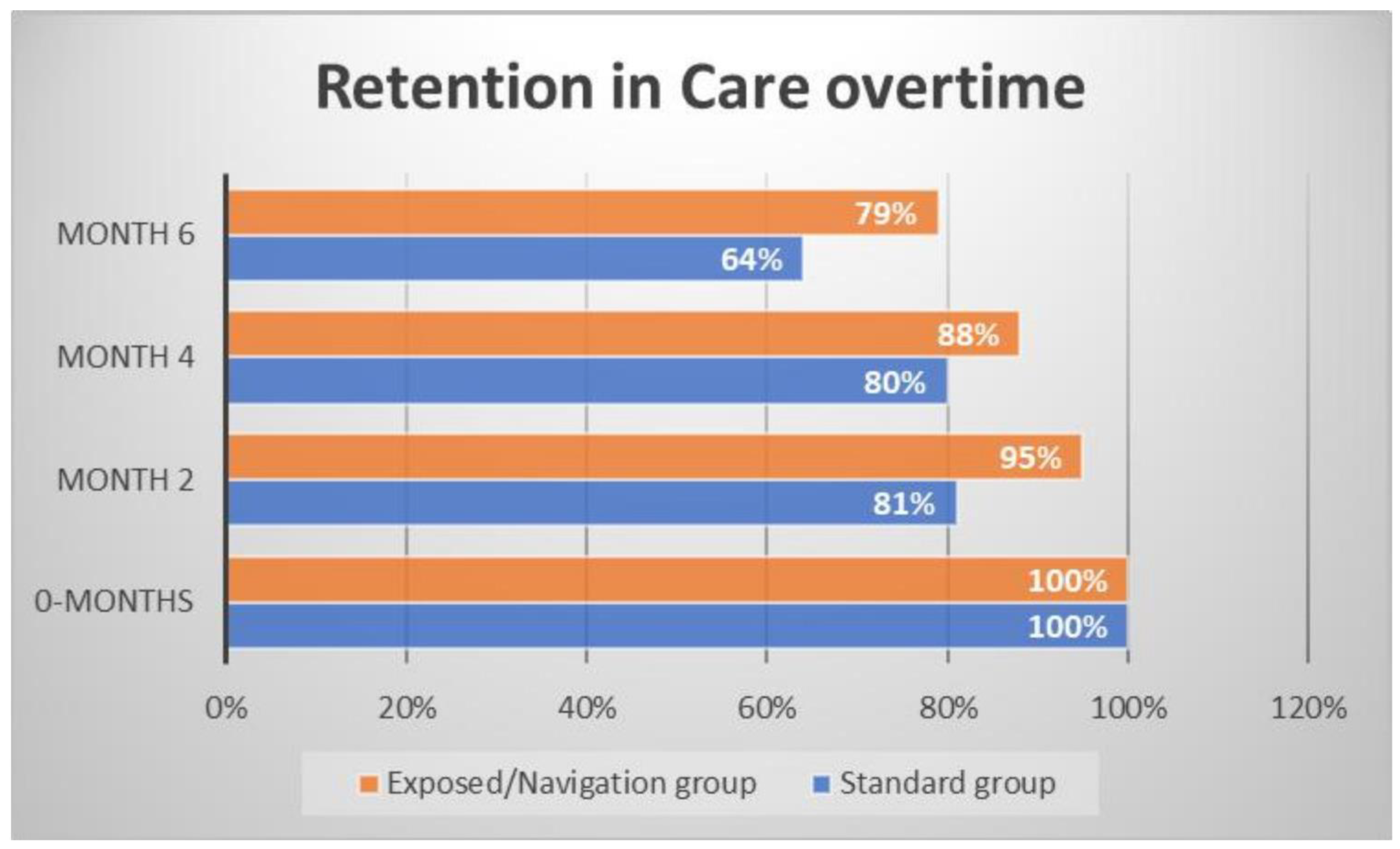

Figure 2 shows the evolution of retention in care over time for both the navigation and standard groups. The analysis reveals significant differences in retention rates between the two groups, particularly between months two and six. By the end of the 6-month trial, 79% of participants in the navigation group remained in care, compared to only 64% in the standard group. Retention in care was notably higher in the navigation group, with a p-value of 0.05. Additionally, the results showed six deaths in the standard group, compared to three deaths in the navigation group by the end of the study.

3.3. Effect of Patient Navigation on Retention in Care and Virologic Suppression

Table 2 examines the impact of the navigation approach on participants' viral load after 6 months of follow-up. The results show a significant improvement in retention in care and viral load control in the navigation group compared with the standard group. For participants with a viral load of less than 50 copies/mL, retention was significantly higher in the navigation group (64%) compared with 39% in the standard group (p = 0.0025). There was no significant difference between the two groups for viral load between 50 and 1000 copies/mL (p = 0.88). However, for participants with a viral load above 1000 copies/mL, the navigation group showed significantly lower retention (24.7%) than the standard group (50%, p = 0.001). Finally, irrespective of viral load results, retention in care was higher in the navigation group (79%) compared with the standard group (64%, p = 0.05), highlighting the overall positive effect of navigation on treatment adherence.

4. Discussion

In contrast to traditional methods, this study explored adopting a comprehensive and innovative process, namely patient navigation, to monitor ART uptake and evaluate treatment outcomes in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. This study also highlights the importance of the support provided by navigators, with 99% of patients assigned to a navigator in the exposed group, compared with only 14% in the standard group (p = 0.001). The use of WhatsApp, a modern, low-cost communication solution, has played a crucial role in keeping patients connected and adhering to treatment. These results are consistent with those of Roy et al. [

13] and Wang et al. [

14], who have shown that regular reminders via these tools contribute to viral load reduction, particularly in low-resource settings.

In addition, the Navigation model, incorporating psychosocial interventions and home-based care provision, has been shown to improve adherence and promote viral suppression, as reported in the work of Ridgeway et al. [

15] and Laurenzi et al. [

16] This study also supports the findings of Shade et al. [

17], who observed that patient navigation improves viral suppression in developing countries. It outperforms the results observed in other studies, such as Mizuno et al. [

18], where viral suppression increased from 0% to 58% through navigation, and Shacham et al. [

19] and Steward et al. [

20], which demonstrated even better outcomes with a different approach. Furthermore, the exposed group significantly reduced loss to follow-up (LTFU) rates, with respective rates of 17% and 28%. These results are lower than those observed in certain programs, particularly in Nigeria [

21,

22,

23], confirming the essential role of patient navigation in reducing loss to follow-up. Finally, the study highlights that patient navigation improves treatment adherence and viral suppression in newly diagnosed patients who start treatment immediately. This is consistent with the findings of Labhardt et al. [

2], who emphasized that initiating ART treatment without proper support, such as navigation, can compromise long-term adherence. These results highlight the importance of support from the outset of treatment to ensure sustained patient engagement in care.

The data showed that patient navigation positively affected retention in care and viral suppression. 64% of participants in the navigation group had a VL <50 copies/mL compared to the standard group. These factors contribute to improved treatment adherence and a lower viral load in the navigation group [

24]. The exposed group also showed a 25% higher retention rate of patients with viral suppression below 50 copies/mL than the standard group. These results are consistent with those of Voloshyn [

25], who observed higher risk ratios in the exposed group, suggesting an increased risk. This highlights the effectiveness of the navigation model in maintaining viral suppression at low levels. Furthermore, a statistically significant difference was observed (p = 0.003), with 94.5% of patients with viral suppression (VL <50 and <1000) in the exposed group remaining on treatment after six months, compared to 78% in the standard group. These results are comparable to those of Mnzava [

26], who reported a viral suppression rate of 88% and a 91% rate observed during the HIV impact census in Tanzania [

26,

27]. These findings confirm the importance of virological monitoring, treatment adherence, and clinical follow-up in maintaining treatment efficacy in sub-Saharan Africa, as emphasized by Nanyeenya et al. [

28].

The results of our study also revealed significant demographic differences between the groups, particularly in terms of age, marital status, and place of residence. These differences may reflect the diversity of the population the navigation program targeted, attracting participants from various backgrounds. Place of residence underlines the challenges of access to care in the region, an essential factor to be considered. However, these demographic variations did not significantly impact clinical variables related to disease progression, which reinforces the validity of the navigation intervention as a factor positively influencing retention in care and viral load. In addition, significant behavioral differences were observed, with a significantly higher proportion of smokers (p = 0.002) and drinkers (p = 0.019) in the control group. These findings highlight the importance of considering contextual and behavioral factors that may influence the effectiveness of interventions in patient groups, as suggested by Mizuno et al. [

18] and Buh [

29]. However, these parameters did not affect the navigation results separately, suggesting that the navigation intervention was effective independently of these behavioral or demographic variables.

5. Conclusion

Our randomized controlled trial shows that patient navigation significantly improves viral load suppression and retention in care. Compared to the standard approach, this is especially true for newly diagnosed patients who begin treatment with early-stage disease and a CD4 count ≥50 cells/mm³. Including psychosocial support and community healthcare services in the navigation process further improved the outcomes. This study highlights the importance of integrating patient navigation into HIV care to improve treatment outcomes. However, further research is needed to assess the long-term impact of patient navigation on HIV outcomes.

Funding

This study was supported by the Chemical Industries Education and Training Authority (CHIETA) and the Strategic Health Innovation Partnerships (SHIP) of the Medical Research Council (MRC), fundings attributed to Prof. E.J.N.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available owing to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to this study's participants and the dedicated medical staff for their invaluable contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/208825/1/9789241549684_eng.

- Labhardt, N.D.; Brown, J.A.; Sass, N.; Ford, N.; Rosen, S.; et al. Treatment Outcomes After Offering Same-Day Initiation of HIV Treatment—How to Interpret Discrepancies Between Different Studies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govere, S.M.; Kalinda, C.; Chimbari, M.J. The impact of same-day antiretroviral therapy initiation on retention in care and clinical outcomes at four eThekwini clinics, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.; Nonzee, N.; Tom, L.; Murphy, K.; Hajjar, N.; Bularzik, C.; Dong, X.; Simon, M.A. Patient navigators' reflections on the navigator-patient relationship. J. Cancer Educ. 2014, 29, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, N.; Caffrey, L.; Smith, A. Patient navigation: a new role for nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 2554–2561. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, H.P.; Rodriguez, R.L. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 2011, 117, 3539–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Fillion, L.; Fergus, K. Patient navigation in cancer care. J. Oncol. Nav. Surv. 2018, 9, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo, M.R. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations. Med. Care 2004, 42, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, D. Intimacy and social exchange. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1979, 42, 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.; Dreyer, P.; Clark, P. Patient navigation: a systematic review. J. Healthc. Manag. 2017, 62, 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, M.A.; Trosman, J.R.; Rapkin, B.; et al. Systematic Patient Navigation Strategies to Scale Breast Cancer Disparity Reduction by Improved Cancer Prevention and Care Delivery Processes. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e1462–e1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trosman, J.R.; Carlos, R.C.; Simon, M.A.; et al. Care for a patient with cancer as a project: Management of complex task interdependence in cancer care delivery. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, M.; Bolton Moore, C.; Sikazwe, I.; Holmes, C.B. A Review of Differentiated Service Delivery for HIV Treatment: Effectiveness, Mechanisms, Targeting, and Scale. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Violette, L.R.; Dorward, J.; Ngobese, H.; Sookrajh, Y.; Bulo, E.; Quame-Amaglo, J.; Thomas, K.K.; Garrett, N.; Drain, P.K. Delivery of Community-based Antiretroviral Therapy to Maintain Viral Suppression and Retention in Care in South Africa. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2024, 93, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, K.; Dulli, L.S.; Murray, K.R.; Silverstein, H.; Dal Santo, L.; Olsen, P.; et al. Interventions to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0189770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenzi, C.A.; du Toit, S.; Ameyan, W.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Kara, T.; Brand, A.; et al. Psychosocial interventions for improving engagement in care and health and behavioural outcomes for adolescents and young people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 24, e25741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shade, S.B.; Osmand, T.; Mwangi, M. Patient navigation and viral suppression among people living with HIV in Kenya. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Y.; Higa, D.H.; Leighton, C.A.; Roland, K.B.; Deluca, J.B.; Koenig, L.J. Is HIV patient navigation associated with HIV care continuum outcomes? AIDS 2018, 32, 2557–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacham, E.; López, J.D.; Brown, T.M.; Tippit, K.; Ritz, A. Enhancing Adherence to Care in the HIV Care Continuum: The Barrier Elimination and Care Navigation (BEACON) Project Evaluation. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, W.T.; Agnew, E.; de Kadt, J.; Ratlhagana, M.J.; Sumitani, J.; Gilmore, H.J.; Grignon, J.; Shade, S.B.; Tumbo, J.; Barnhart, S.; Lippman, S.A. Impact of SMS and peer navigation on retention in HIV care among adults in South Africa: results of a three-arm cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, e25774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürcher, K.; Mooser, A.; Anderegg, N.; Tymejczyk, O.; Couvillon, M.J.; Nash, D. Outcomes of HIV-positive patients lost to follow-up in African treatment programmes. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaba, P.A.; Genberg, B.L.; Sagay, A.S.; Agbaji, O.O.; Meloni, S.T.; Dadem, N.Y.; et al. Retention in Differentiated Care: Multiple Measures Analysis for a Decentralized HIV Care and Treatment Program in North Central Nigeria. J. AIDS Clin. Res. 2018, 9, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogun, M.; Meloni, S.T.; Igwilo, U.U.; Roberts, A.; Okafor, I.; Sekoni, A.; et al. Status of HIV-infected patients classified as lost to follow up from a large antiretroviral program in southwest Nigeria. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0219903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stitzer, M.L.; Hammond, A.S.; Matheson, T.; Sorensen, J.L.; Feaster, D.J.; Duan, R.; Gooden, L.; Del Rio, C.; Metsch, L.R. Enhancing Patient Navigation with Contingent Incentives to Improve Healthcare Behaviors and Viral Load Suppression of Persons with HIV and Substance Use. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018, 32, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloshyn, I. Predicting the Utilization Rate and Risk Measures of Committed Credit Facilities. Visnyk Natl. Bank Ukraine 2017, 240, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnzava, D.; Okuma, J.; Ndege, R.; et al. Decentralization of viral load testing to improve HIV care and treatment cascade in rural Tanzania: observational study from the Kilombero and Ulanga Antiretroviral Cohort. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. United Republic of Tanzania | UNAIDS. https://www.unaids.org/en/keywords/united-republic-tanzania (accessed on , 2024). 7 July.

- Nanyeenya, N.; Kiwanuka, N.; Nakanjako, D.; Nakigozi, G.; Kibira, S.P.S.; Nabadda, S.; Kiyaga, C.; Sewanyana, I.; Nasuuna, E.; Makumbi, F. Low-level viraemia: An emerging concern among people living with HIV in Uganda and across sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. J. Lab. Med. 2022, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buh, A.W. Non-Adherence to HIV Treatment Among Patients in Cameroon: Prevalence, Predictors and Effective Strategies Improving Treatment Adherence. Ph.D. Thesis, Université d’Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).