Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A task offloading problem is formulated as a multi-objective optimization problem to minimize both latency and energy.

- A DQN learning-based energy-efficient and latency-aware algorithm is proposed for optimal offloading decision strategies in the IoT-fog-cloud collaboration model and provides a methodology for assigning tasks to different layers.

- We evaluated and validated the suggested model and showed how this model improves QoS metrics by comparing it with previous studies. (in particular, energy consumption and application latency).

2. Related Works

2.1. Energy-Aware Task Offloading

2.2. Latency Aware Task Offloading

3. System Model and Problem Formulation

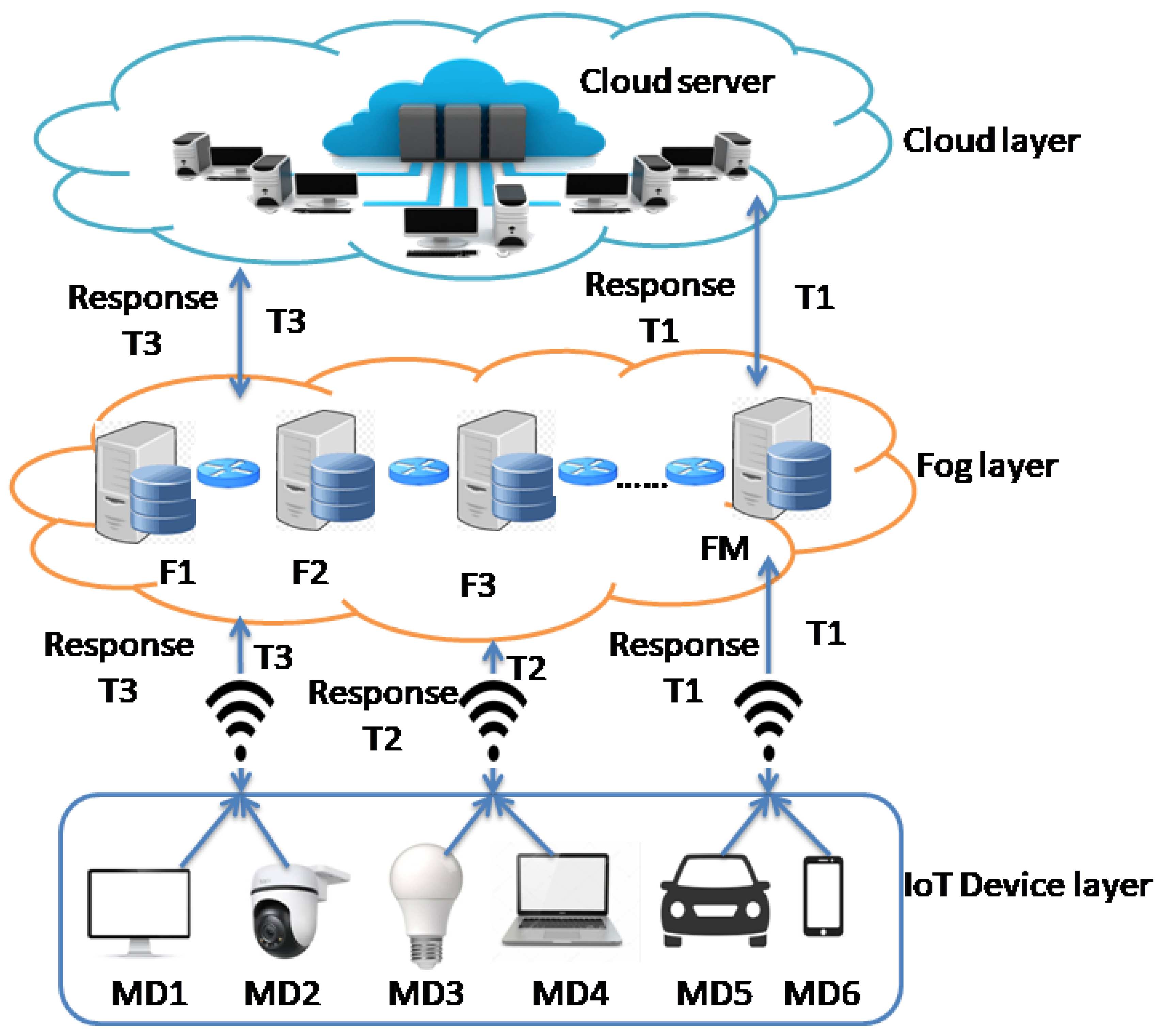

3.1. System model

3.2. Task Offloading Model

3.3. The three variant executions

3.3.1. Local Execution

3.3.2. Fog Execution

3.3.3. Cloud Execution

3.4. Problem Formulation

- C1 :

- C2 :

- C3 :

- C4 :

- C5 :

- C6 :

- C1, C2, and C3 denote that these decision variables are guaranteed to be binary through these 3 constraints.

- C4 indicates that there should only be one location in which each work is completed, so the choice location variable will be equal to 1.

- C5 ensures that the bandwidth assigned to the task must be positive.

- C6 indicates that the task latency must not exceed the maximum tolerable delay to execute task , whether in a local, fog, or cloud server.

4. Proposed Solution

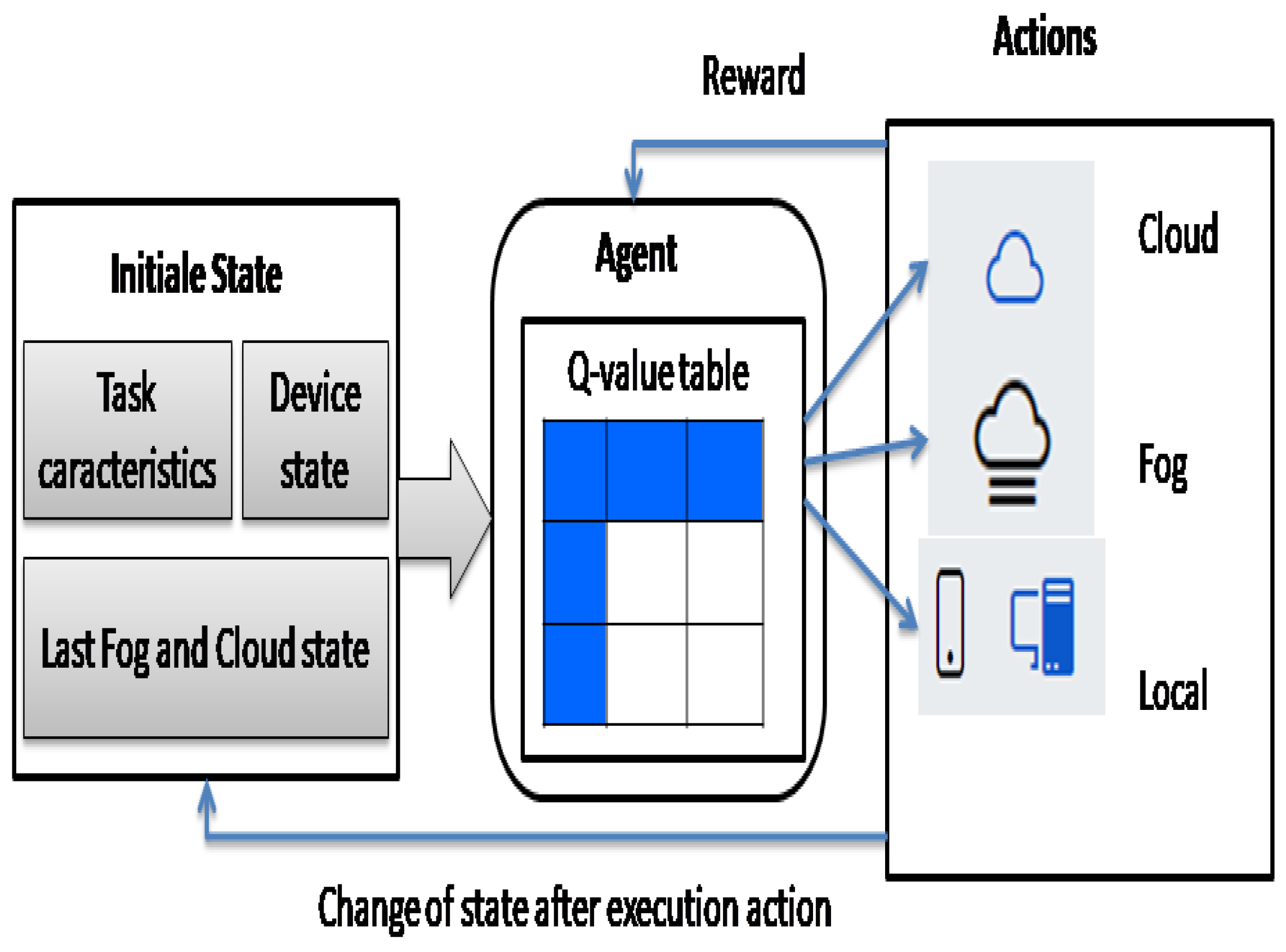

4.1. Optimal Task Offloading Strategy

| Algorithm 1 Optimal task offloading strategy |

|

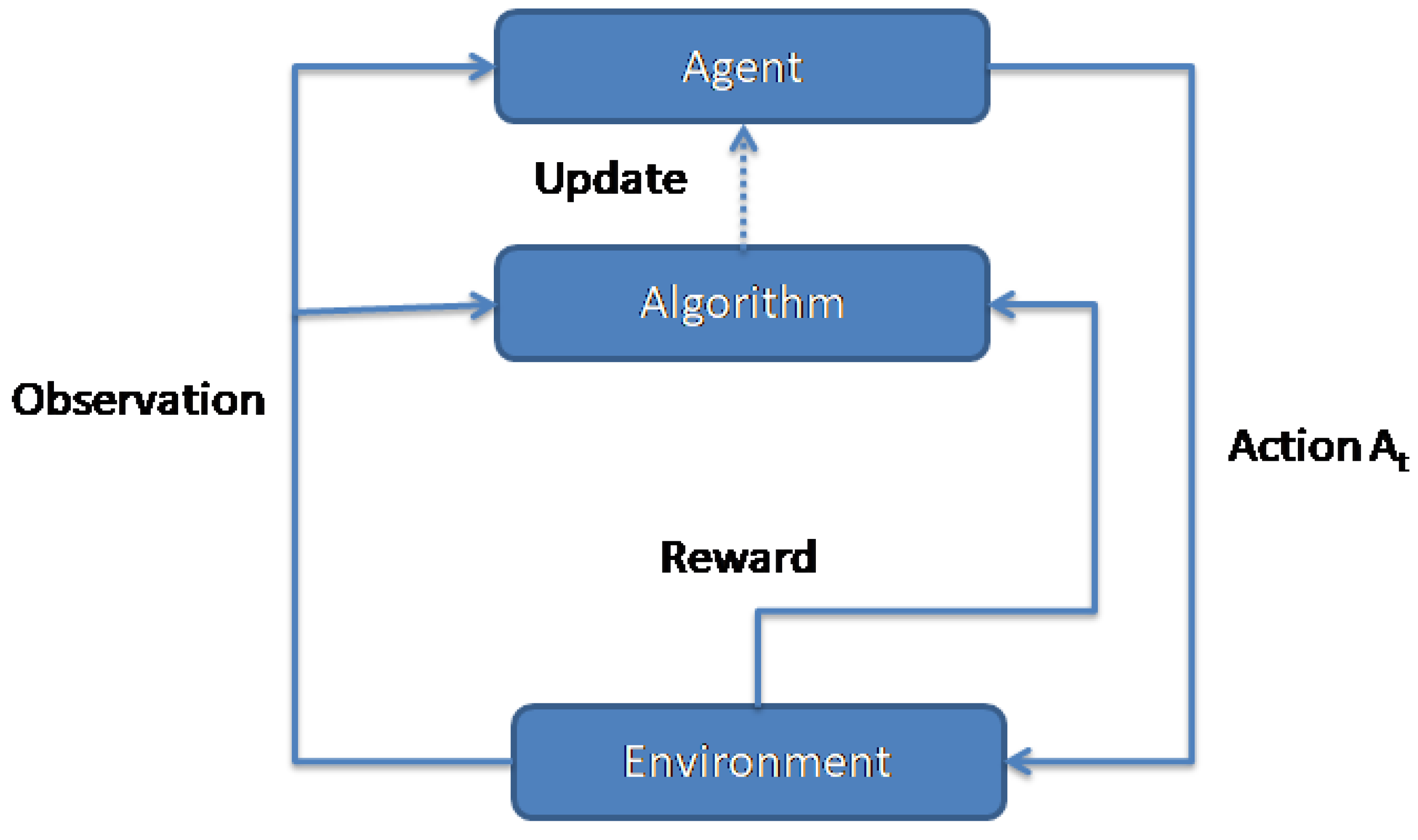

4.2. DQN-Based Task Offloading

| Algorithm 2 DQN-based task offloading strategy |

|

5. Performance Analysis and Discussion

5.1. Simulation Model

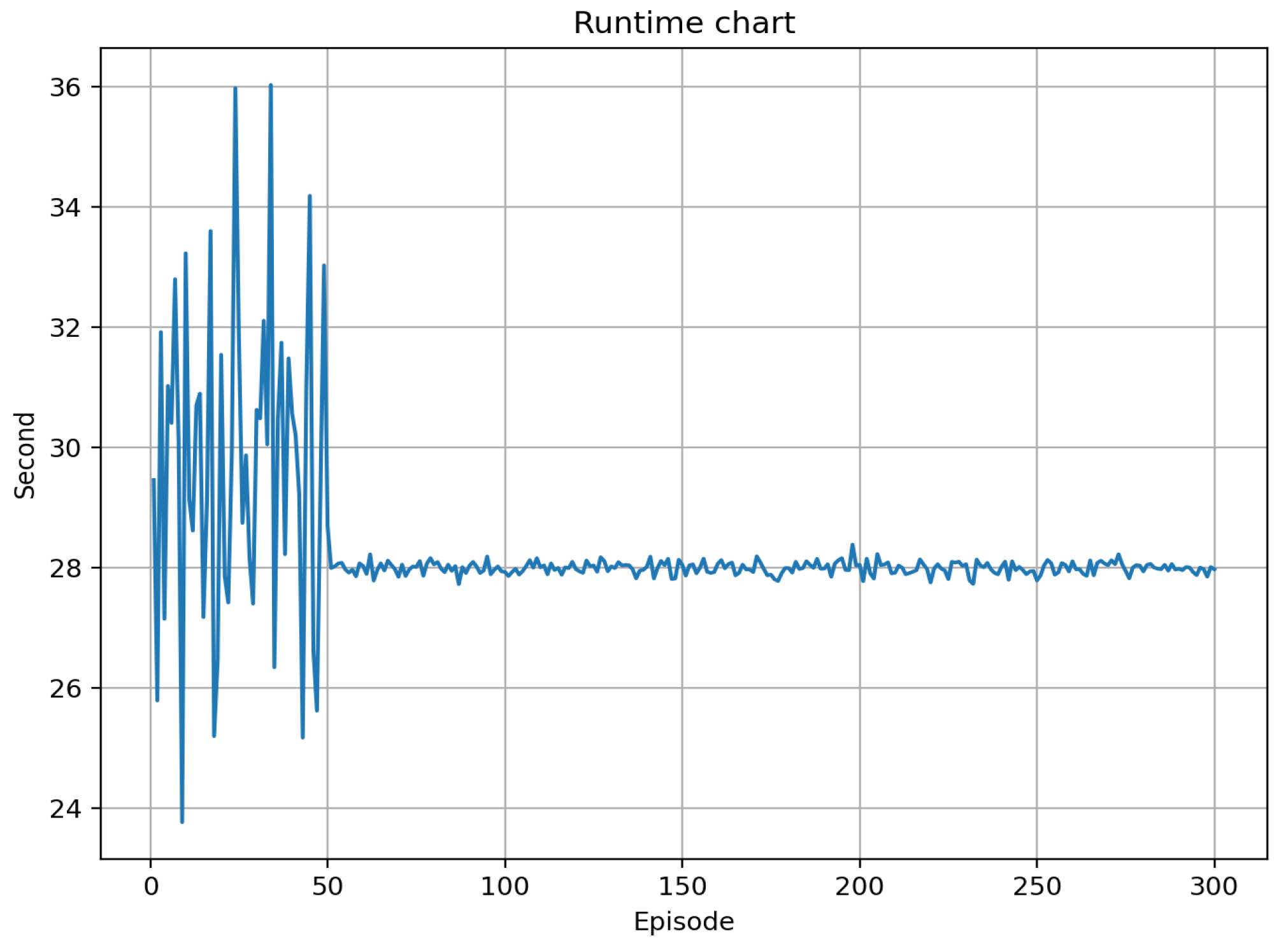

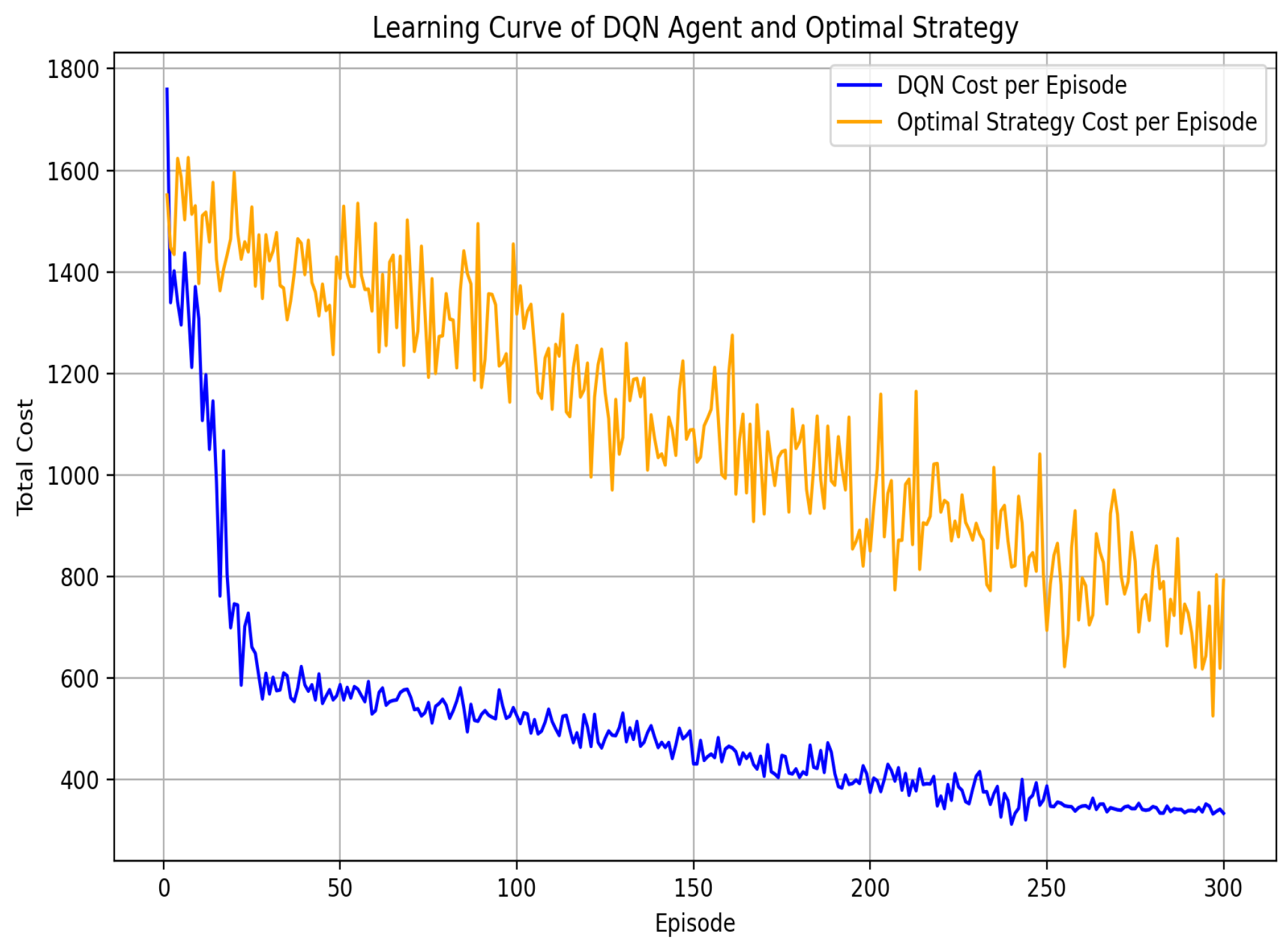

5.2. The proposed algorithms convergence proof

5.3. The proPosed Algorithms Comparative Analysis

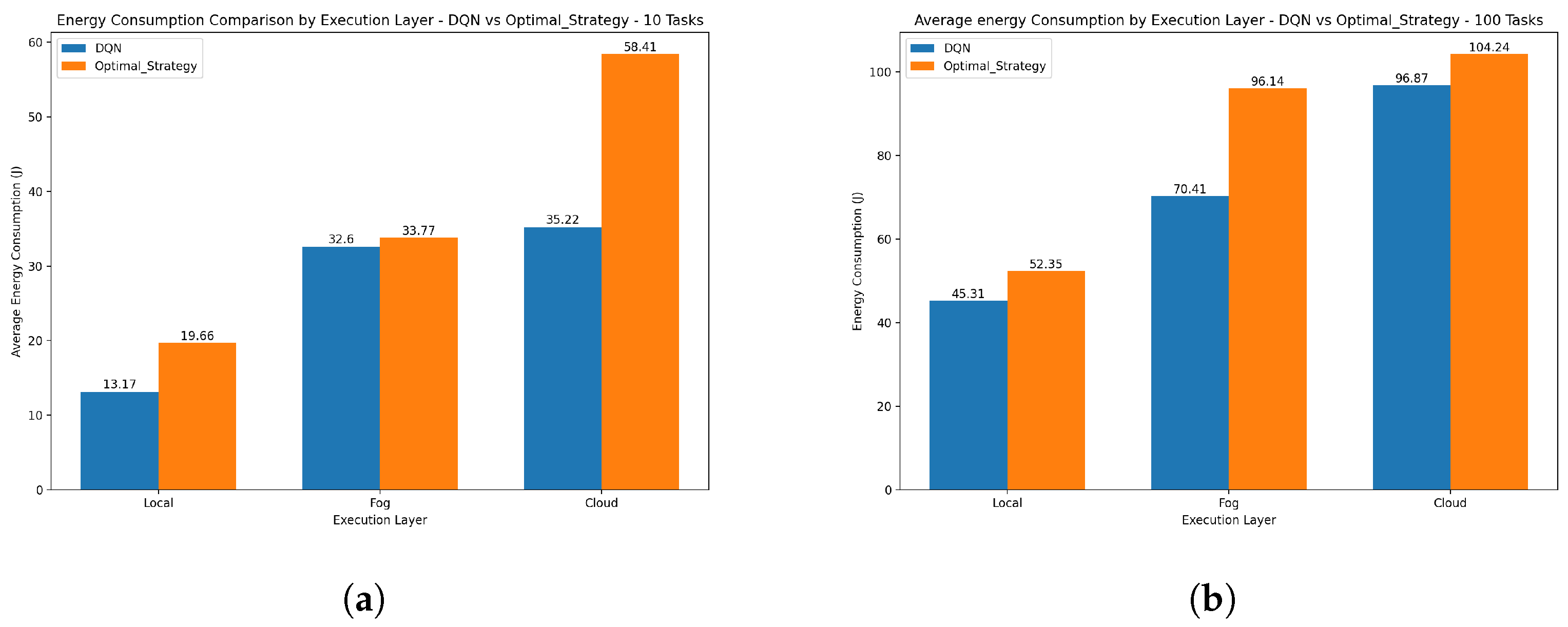

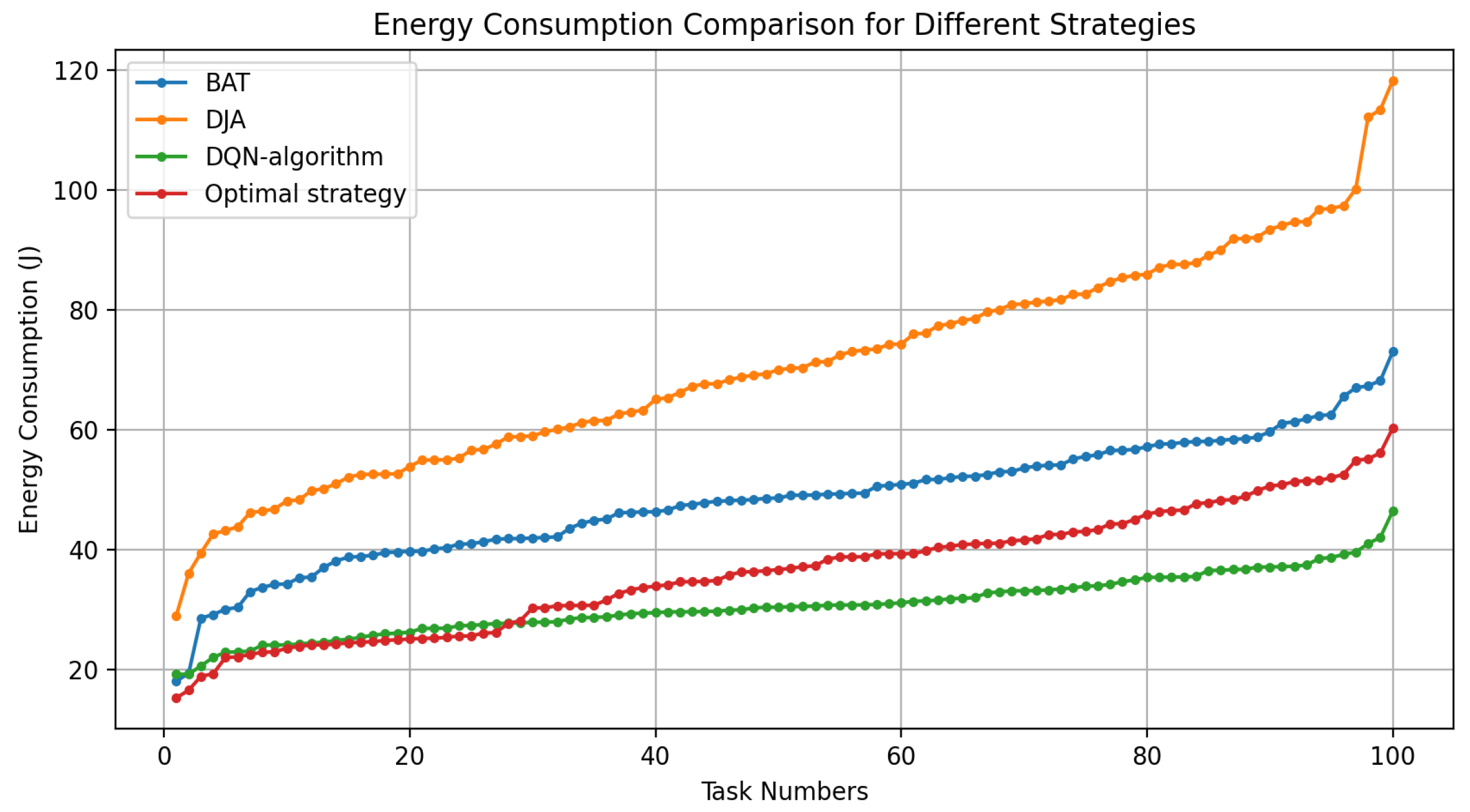

5.3.1. Energy consumption

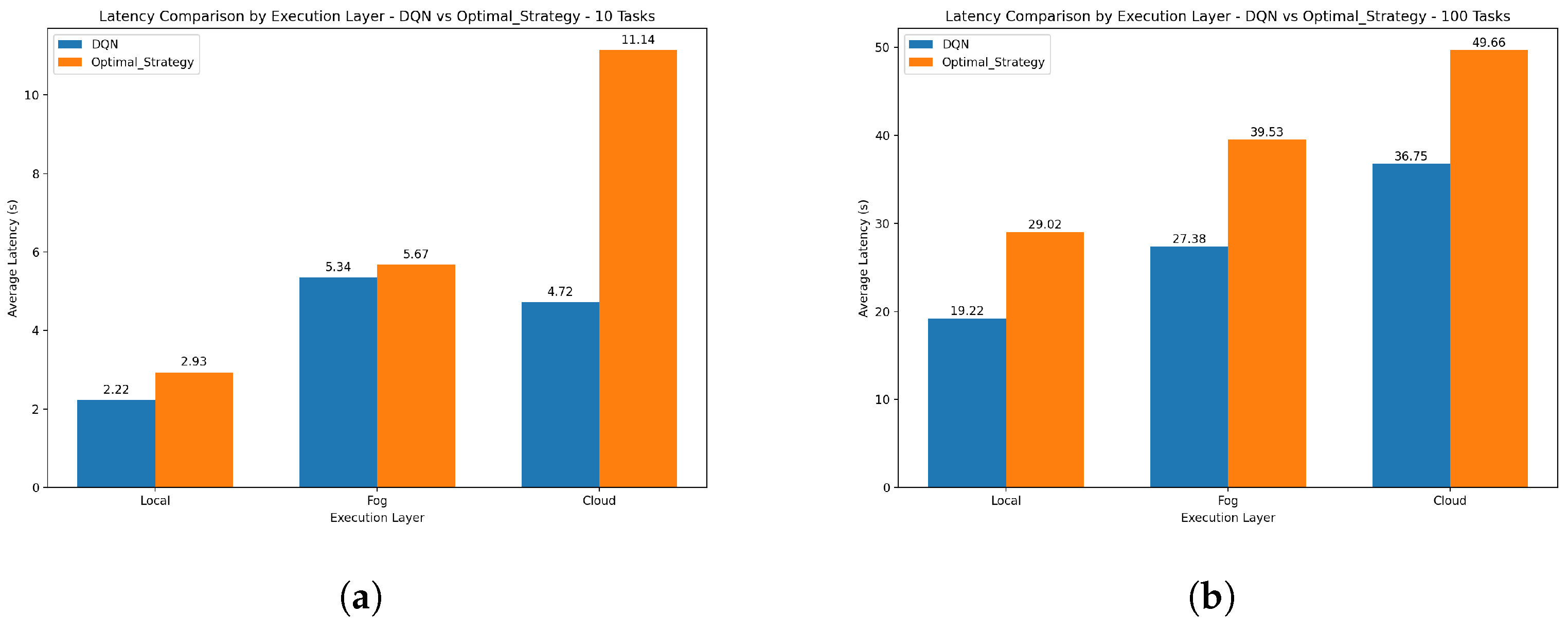

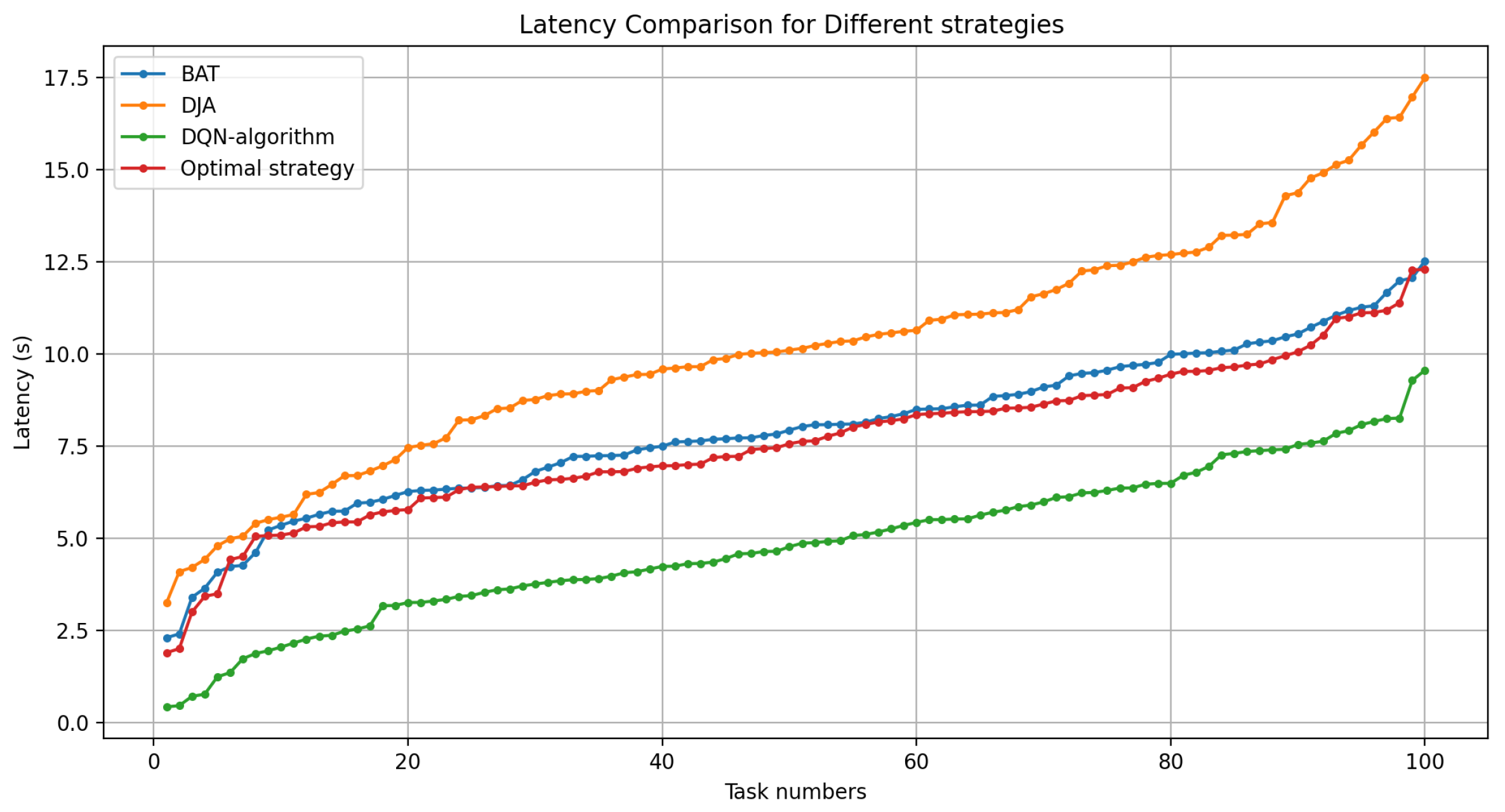

5.3.2. Latency

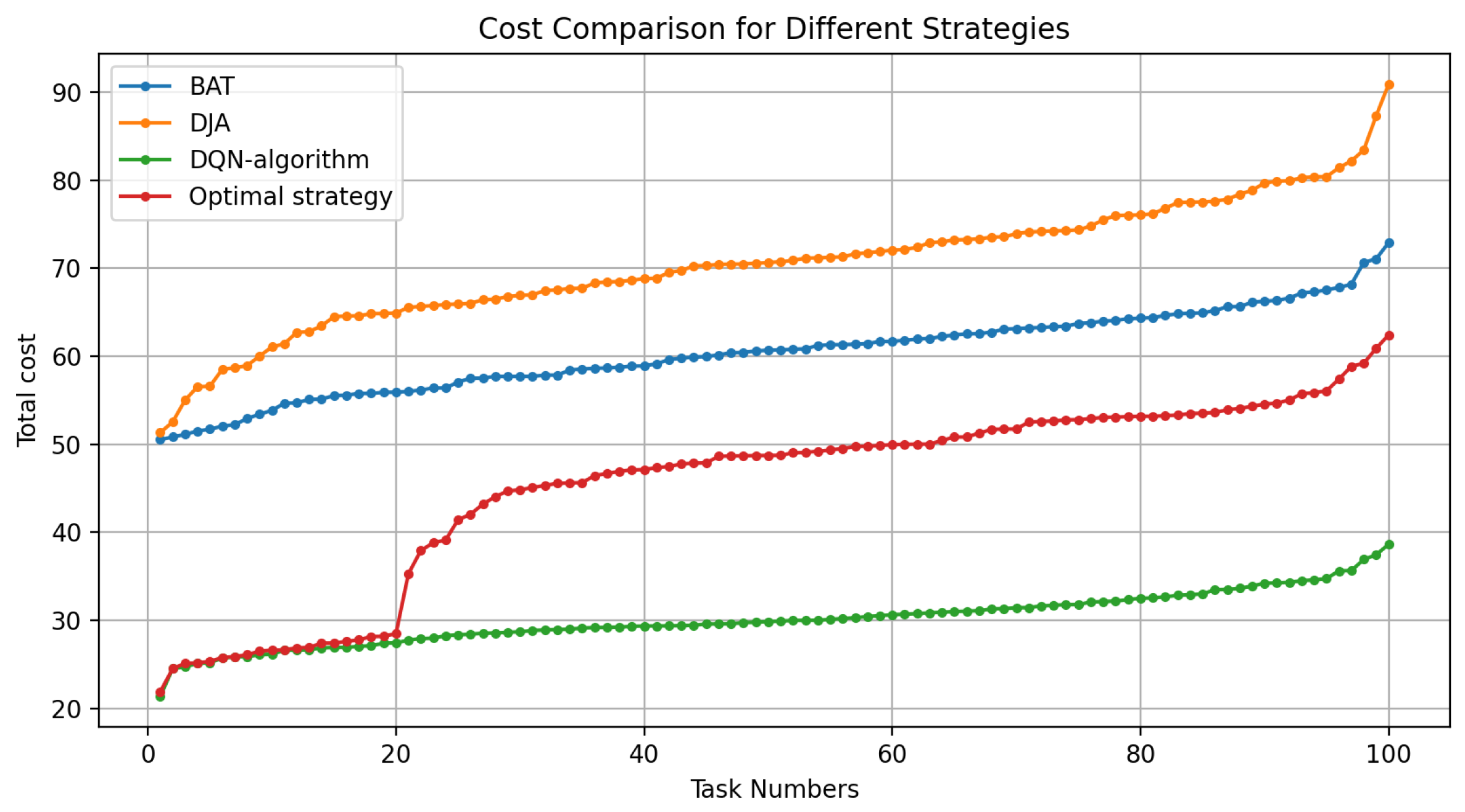

5.4. Compared Method

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aknan, M.; Arya, R. AI and Blockchain Assisted Framework for Offloading and Resource Allocation in Fog Computing. Journal of Grid Computing 2023, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei, B.; Mohammadsalehi, A.A.; Khoosani, K.T.; Zarbaf, S.; Monazzah, A.M.H.; Samie, F.; Bauer, L.; Henkel, J.; Ejlali, A. Impacts of Mobility Models on RPL-Based Mobile IoT Infrastructures: An Evaluative Comparison and Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 167779–167829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, M.; Wu, H.; Palaniswami, M.; Buyya, R. An Application Placement Technique for Concurrent IoT Applications in Edge and Fog Computing Environments. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2021, 20, 1298–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, M.K.; Alwakeel, S.S.; Alohali, Y.A. A Multi-Classifier-Based Algorithm for Energy-Efficient Tasks Offloading in Fog Computing. Sensors 2023, 23, 7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; Jabir, A. A Lightweight Multi-Objective Task Offloading Optimization for Vehicular Fog Computing. Iraqi Journal for Electrical and Electronic Engineering 2021, 17(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Du, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yuan, J. Priority-Aware Task Offloading in Vehicular Fog Computing Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69(12), 16067–16081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H. A.; Aldossary, M. ; Jaber Almutairi; Elgendy, I. A. Energy-Aware and Secure Task Offloading for Multi-Tier Edge-Cloud Computing Systems. Sensors 2023, 23 (6), 3254–3254. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sharma, S. C.; Goel, A.; Singh, S. P. A Comprehensive Survey for Scheduling Techniques in Cloud Computing. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2019, 143, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-L.; Chen, Y.-S.; Yang, S.-W.; Wu, C.-H. Energy-Efficient Task Offloading for Time-Sensitive Applications in Fog Computing. IEEE Systems Journal 2019, 13(3), 2930–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, S.; Gill, S. S.; Song, C.; Xu, M.; Aslanpour, M. S.; Toosi, A. N.; Du, J.; Wu, H.; Ghosh, S.; Chowdhury, D.; Golec, M.; Kumar, M.; Abdelmoniem, A. M.; Cuadrado, F.; Varghese, B.; Rana, O.; Dustdar, S.; Uhlig, S. AI-Based Fog and Edge Computing: A Systematic Review, Taxonomy and Future Directions. Internet of Things 2023, 21, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhang, X.; Qin, S.; John, C.S. Lui; Zhou, Z. Online Task Offloading for 5G Small Cell Networks. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2022, 21(6), 2103–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsyafizan, W.; Mohd, S. ; Kaharudin Dimyati; Muhammad Awais Javed; Idris, A. ; Darmawaty Mohd Ali; Abdullah, E. Energy-Efficient Task Offloading in Fog Computing for 5G Cellular Network. Engineering Science and Technology an International Journal 2024, 50, 101628–101628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Vahid Dastjerdi, A.; Ghosh, S. K.; Buyya, R. IFogSim: A Toolkit for Modeling and Simulation of Resource Management Techniques in the Internet of Things, Edge and Fog Computing Environments. Software: Practice and Experience 2017, 47 (9), 1275–1296. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Song, Q.; Guo, L.; Lee, I. Energy-Efficient Secure Computation Offloading in Wireless Powered Mobile Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72(5), 6907–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-L.; Cheng, C.-S.; Shen, Y.-H. A Reinforcement Learning-Based Multi-Objective Bat Algorithm Applied to Edge Computing Task-Offloading Decision Making. Applied Sciences 2024, 14(12), 5088–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, K. M.; Awad, A. I.; Khashaba, M. M.; Fouda, M. M. ; Mohsen Guizani; Mohamed, E. R. Optimized Multi-User Dependent Tasks Offloading in Edge-Cloud Computing Using Refined Whale Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing 2024, 9 (1), 14–30. [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Xing, H.; Wang, X.; Luo, S.; Dai, P.; Li, K. Offloading Dependent Tasks in Multi-Access Edge Computing: A Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning Approach. Future Generation Computer Systems 2022, 128, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Song, S.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Yang, F.; Zhai, L. Dependent Tasks Offloading Based on Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm in Multi-Access Edge Computing. Applied Soft Computing 2021, 112, 107790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Duan, X.; Xu, C. SLA-Based Task Offloading for Energy Consumption Constrained Workflows in Fog Computing. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 156, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ale, L.; Zhang, N.; Fang, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Li, L. Delay-Aware and Energy-Efficient Computation Offloading in Mobile-Edge Computing Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking 2021, 7(3), 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Sabireen; Venkataraman, N. A Hybrid and Light Weight Metaheuristic Approach with Clustering for Multi-Objective Resource Scheduling and Application Placement in Fog Environment. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 223, 119895–119895. [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Yu, G.; He, Y.; Li, G. Y. Collaborative Cloud and Edge Computing for Latency Minimization. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68(5), 5031–5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Huang, J.; Gao, H.; Deng, S. A Differential Evolution Offloading Strategy for Latency and Privacy Sensitive Tasks with Federated Local-Edge-Cloud Collaboration. ACM Transactions on Sensor Networks 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S. Task Offloading in MEC Systems Interconnected by Metro Optical Networks: A Computing Load Balancing Solution. Optical Fiber Technology 2023, 81, 103543–103543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Enciso, A.; Skarmeta, A. F. A Multi-Layer Guided Reinforcement Learning-Based Tasks Offloading in Edge Computing. Computer Networks 2023, 220, 109476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, P.; Du, C.; Li, Y. Energy-Efficient Edge Caching and Task Deployment Algorithm Enabled by Deep Q-Learning for MEC. Electronics 2022, 11(24), 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendebudi, A.; Choudhury, S. Designing a Deep Q-Learning Model with Edge-Level Training for Multi-Level Task Offloading in Edge Computing Networks. Applied Sciences 2022, 12(20), 10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C. J. C. H.; Dayan, P. Q-Learning. Machine Learning 1992, 8 (3-4), 279–292. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; He, X.; Zhang, D. Security-Aware Task Offloading Using Deep Reinforcement Learning in Mobile Edge Computing Systems. Electronics 2024, 13(15), 2933–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy, A.; Elgendy, I. A.; Yu, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. Secure Task Offloading in Blockchain-Enabled Mobile Edge Computing with Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2022, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Qu, D.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y. Dependency-Aware Dynamic Task Offloading Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning in Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2023, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, K.; Xiao, B.; Li, K. Multi-Objective Optimization for Joint Task Offloading, Power Assignment, and Resource Allocation in Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtamu Mohammed Birhanie; Mohammed Oumer Adem. Optimized Task Offloading Strategy in IoT Edge Computing Network. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2024, 36 (2), 101942–101942. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Jana, P. K. A Metaheuristic-Based Task Offloading Scheme with a Trade-off between Delay and Resource Utilization in IoT Platform. Cluster computing 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Baranwal, G.; Shankar, Y.; Vidyarthi, D. P. A Survey on Nature-Inspired Techniques for Computation Offloading and Service Placement in Emerging Edge Technologies. World Wide Web 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Deng, D.-J.; Suwatcharachaitiwong, S.; Li, Y.-S. Dynamic Weighted Fog Computing Device Placement Using a Bat-Inspired Algorithm with Dynamic Local Search Selection. Mobile Networks and Applications 2020, 25(5), 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicone, C. Stability Theory of Ordinary Differential Equations. Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science 2009, 8630–8649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Baranwal, G.; Shankar, Y.; Vidyarthi, D. P. A Survey on Nature-Inspired Techniques for Computation Offloading and Service Placement in Emerging Edge Technologies. World Wide Web 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yan, L.; Zhou, X. Task Offloading Based on LSTM Prediction and Deep Reinforcement Learning for Efficient Edge Computing in IoT. Future Internet 2022, 14(2), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeeb, H. B.; Naser, S.; Bariah, L. ; Sami Muhaidat; Murat Uysal. Digital Twin-Assisted OWC: Towards Smart and Autonomous 6G Networks. IEEE Network 2024, 38 (6), 153–162. [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Choudhury, S. Deep Q-Learning Enabled Joint Optimization of Mobile Edge Computing Multi-Level Task Offloading. Computer Communications 2021, 180, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Wong, V. W. S. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Task Offloading in Mobile Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2020, 21(6), 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.; Hsu, C.-H.; Chen, G.-H.; Wei, H.-Y. Deep Q-Learning Based Dynamic Network Slicing and Task Offloading in Edge Network. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2022, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penmetcha, M.; Min, B.-C. A Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Dynamic Computational Offloading Method for Cloud Robotics. IEEE Access 2021, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, K.; Ming, Z.; Cheng, L. Dependency-Aware Task Offloading Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning in Mobile Edge Computing Networks. Wireless Networks 2023, 30(6), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Objectives | Proposed solution | Executions locations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Minimize network latency and energy | BAT based | Local devices, fog, and cloud . |

| [4] | Minimize energy | MCEETO | local devices, fog, and cloud. |

| [13] | Minimize latency | Edge-ward | local devices, edge, fog, and cloud. |

| [14] | Minimize energy | SEE | local devices and MEC. |

| [15] | Minimize network latency and energy | MOBA-CV-SARSA | local device and edge server . |

| [16] | Minimize latency, energy and cost | RWOA | Local device, MEC, and cloud . |

| [19] | Minimize energy consumption | MSTEC and HREC | Local device, fog, and cloud. |

| [20] | Minimize energy consumption | DRL-based | Local device, fog, and cloud. |

| [21] | Minimize cost and latency | PSO | Local device, fog, and cloud. |

| [22] | Minimize latency | Collaborative cloud-edge scheme | Local device, edge, and cloud. |

| [23] | Minimize latency | federated learning-based | Local device, edge, cloud. |

| [24] | Minimize delay | TD-based CLB-TO and GA-based CLB-TO | Local device, edge servers connected by optical network |

| [32] | Minimize latency | Scheduling and queue management algorithms | Local device, edge, and cloud. |

| [41] | Minimize latency and energy | Deep Q-learnin | Local device and edge. |

| [42] | Minimize latency | LSTM and dual DQN | Local device and edge. |

| [43] | Minimize latency and energy | DRL-based | Local device and edge. |

| Our | Minimize latency, energy, and cost | DQN-based | Local device, fog, and cloud. |

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| MD | A set of mobile devices. |

| N | Number of tasks. |

| T | Set of tasks. |

| The task number i. | |

| Task data size. | |

| The maximum acceptable delay to execute task . | |

| CB | CPU cycles required per bit of data. |

| Total workload of the task . | |

| F | Set of fog node. |

| M | Number of fog nodes. |

| C | Cloud server. |

| Latency(execution time of task ). | |

| Decision offloading matrix of task from user i in the location k. | |

| CPU frequency of device d for a processing task. | |

| Q | The initial latency queue. |

| E | Energy consumption of the task. |

| Energy efficiency factor. | |

| Time processing of task locally. | |

| The total latency of processing task . | |

| Energy consumption of task that processing locally. | |

| Overall cost of task that processing locally. | |

| The transmission time of task to fog layer. | |

| The processing time of task in fog layer. | |

| The total latency of processing task in fog layer. | |

| The energy consumption of task that processing in fog layer. | |

| The MD and fog node communication bandwidth. | |

| The communication transmission power between MD and fog node. | |

| Cost of processing task over fog layer. | |

| The transmission time of task to cloud server. | |

| The processing time of task in cloud server. | |

| The total latency of processing task in cloud server. | |

| The communication bandwidth between fog node and cloud server. | |

| The communication transmission power between the cloud server and fog node. | |

| Cost of processing task over cloud server. |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning rate () | 0.001 |

| Discount factor () | 0.99 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Replay memory size | 100,000 |

| Initial exploration rate () | 1.0 |

| Maximum Episodes | 1000 |

| Maximum Steps per Episode | 200 |

| Latency Factor () | 0.18 |

| Energy Factor () | 0.82 |

| CPU Frequency of device() | 2.0 GHz |

| The CPU frequency of the fog node() | 2.5 GHz |

| The CPU frequency of the cloud server() | 3.0 GHz |

| Energy efficiency of the device () | 0.5 |

| Energy efficiency of the fog node () | 0.4 |

| Energy efficiency of the cloud server () | 0.3 |

| Device Queue latency | 5ms |

| Fog layer Queue latency | 10ms |

| Cloud Server Queue latency | 15ms |

| Bandwidth between the MD and fog node() | 0.1 W |

| The bandwidth between the fog node and cloud server () | 0.05W |

| Task data size () | [10-500] MB |

| Task Workload () | 500 MFLOPS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).