2. Methodology

This research utilizes Google cluster datasets to evaluate a BLSTM architecture for IoT task offloading and resource management datasets proposed in[

13]. The dataset, released in 2011, contains 29 days of comprehensive cloud environment data, including information from 10,388 machines, over 670,000 jobs, and 20 million tasks, with details on task arrival times, data sizes, processing times, and deadlines. The data is organized across six separate tables, and to improve data quality and usability, the researchers performed preprocessing steps, notably converting time measurements from microseconds to seconds, while addressing common challenges like noise, inconsistency, and missing data in the raw dataset.

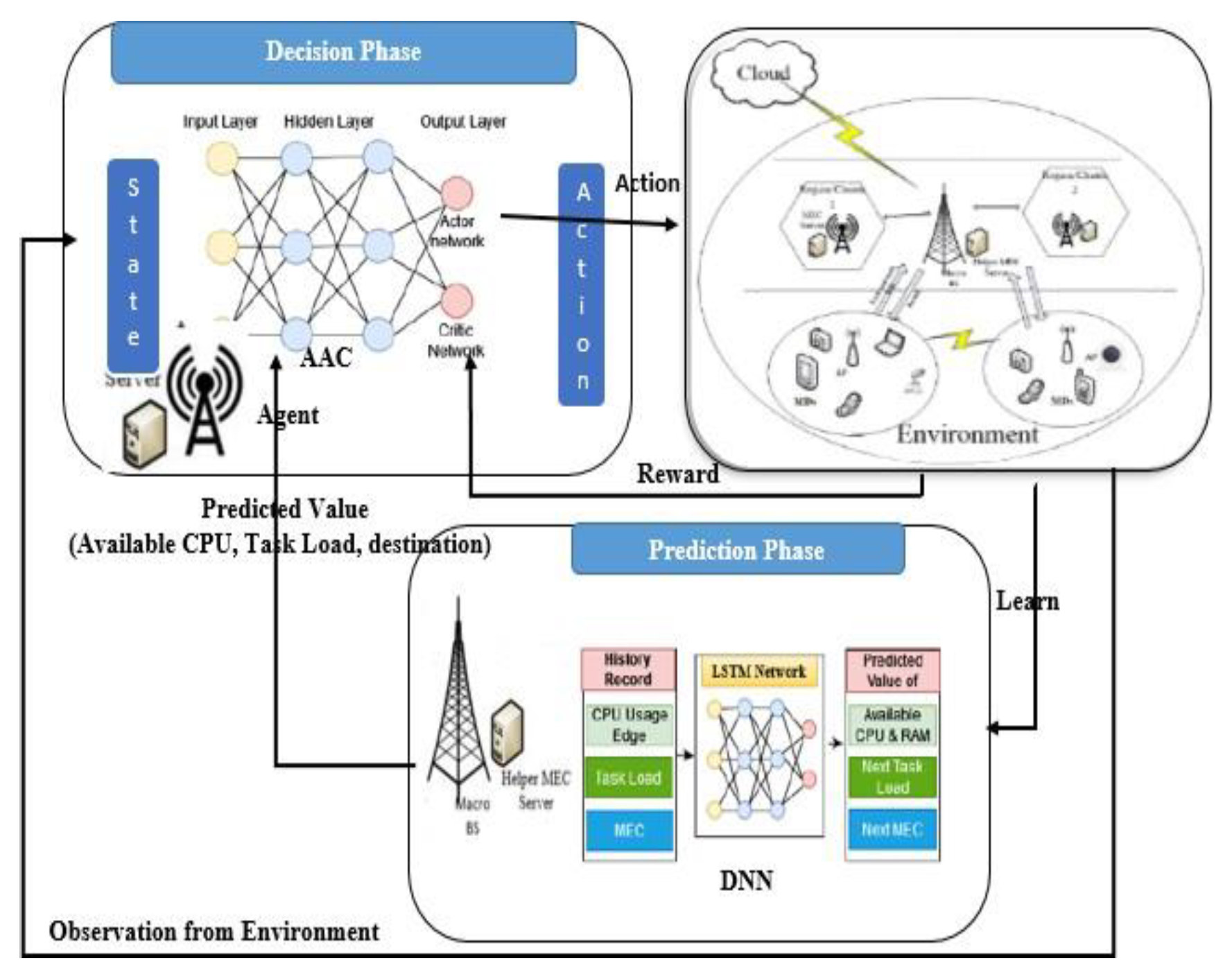

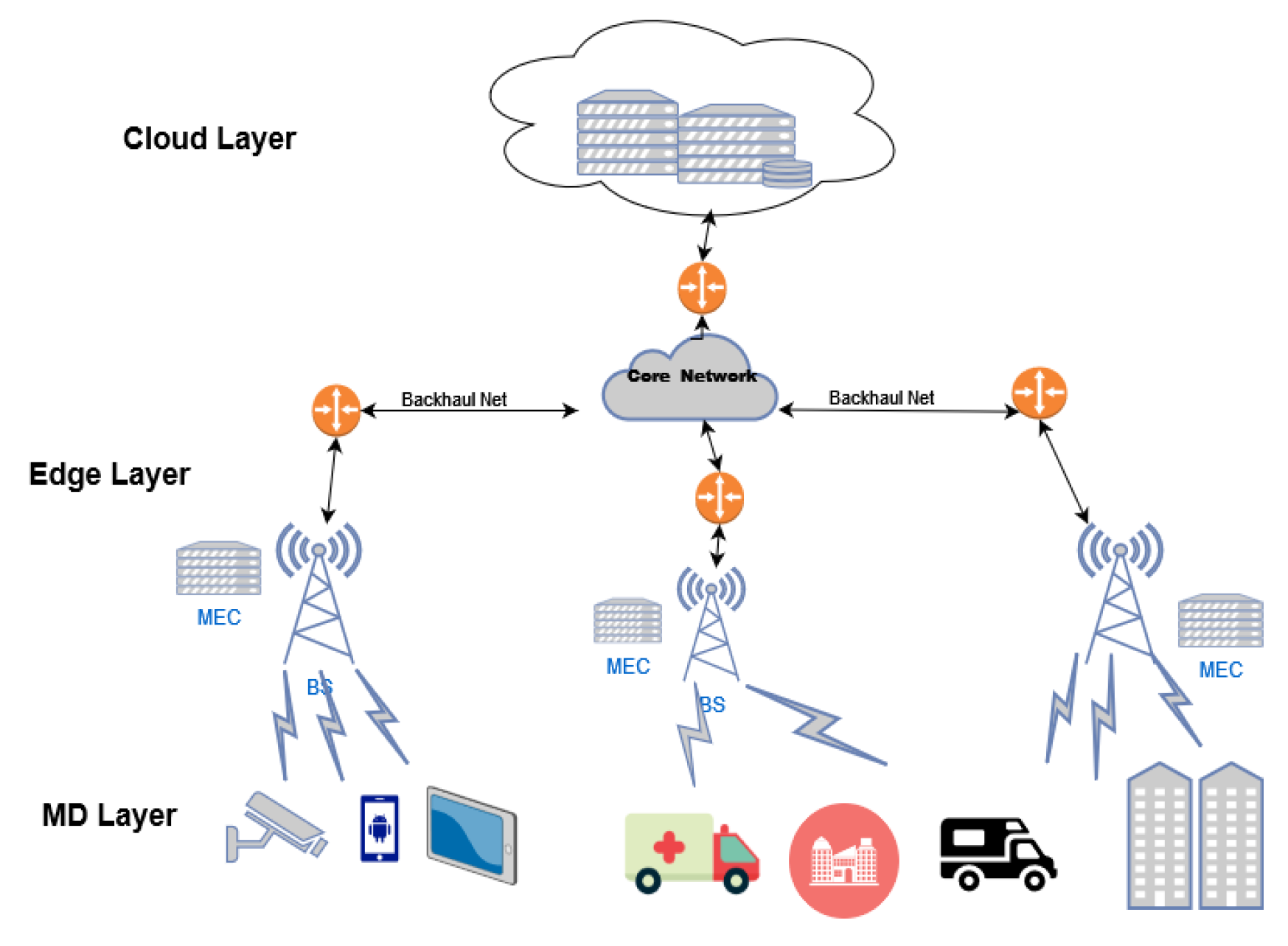

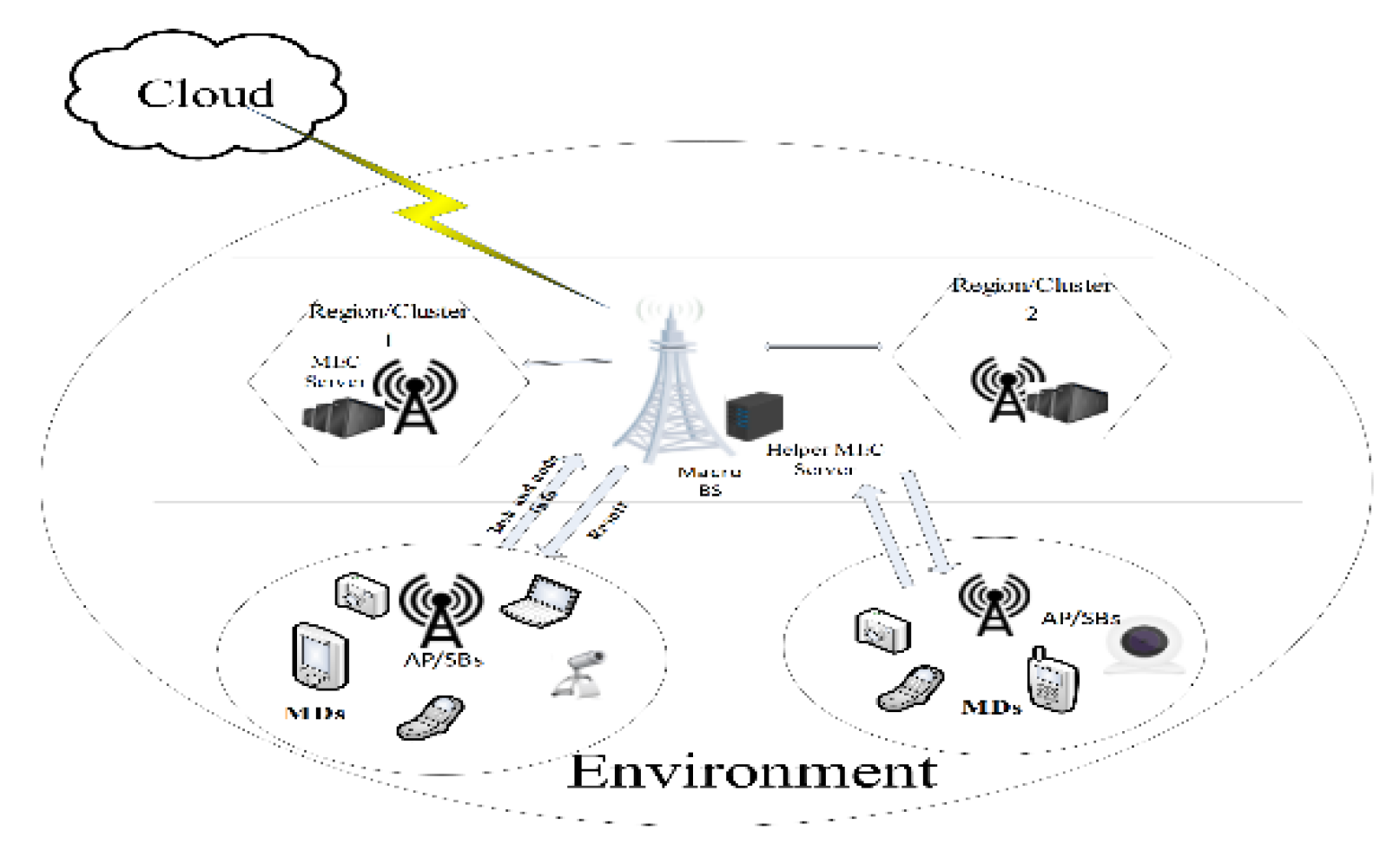

The proposed framework employs a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) agent to optimize task offloading in a Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) environment, as shown in Figure. 2. The system consists of N mobile devices and M MEC servers connected to a macro–Base Station (BS) via fiber cables, with the DRL agent centrally managing task distribution based on historical performance patterns. The agent aims to minimize system cost and task drop rates while maximizing rewards by analyzing server load patterns and predicting capable nodes based on their CPU and memory resource history. The MEC servers, co-located with the macro-BS and Small Base Stations (SBSs), are responsible for collecting, processing, and delivering results for computation tasks submitted by mobile devices within specified time slots, with the goal of achieving optimal cost efficiency and reduced latency for time-sensitive data.

- 1)

Task Model

IoT devices generate tasks across different time slots, represented as T = (1, 2, 3, . . ., Tn), with arrival times and data sizes based on real-world IoT data. Each task is initially sent to the Helper MEC with relevant task and device information. The decision model then determines whether to offload the task to the MEC server or process it locally. In a given time slot t ∈ T, a new task generated by IoT device n ∈ N is characterized by the tuple , , , B, where is the task data size, is the required computational resources per bit (in CPU cycles/bit), ( B ) is the task’s communication bandwidth, and is the maximum tolerated delay to meet QoS demands. If the task isn’t completed by the end of time slot , it’s discarded.

- 2)

Decision model

When a new task arrives for MD n ∈ N at the start of time slot t ∈ T, an optimal offloading decision is required. We use a binary variable to represent this decision: indicates local processing, while signifies offloading to an edge node. The decision model’s role is to determine this offloading scheme optimally.

The decision model will provide the offloading scheme for this task.

In our model, IoT devices generate tasks in real-time. Each task is considered atomic, it cannot be divided or split into smaller parts. This indivisibility is a key characteristic that influences the offloading decision process.

- 3)

Channel /communication Model

Our system, depicted in

Figure 2, features MEC nodes distributed across various regions. This infrastructure includes multiple APs, edge servers, and N MDs, indexed as n= (1,2,3, . . ., N). MDs connect to the MEC through either APs or mobile networks. The macro-BS must determine the optimal task offloading location within the network, considering factors such as edge server workload, response time, latency, and energy consumption.

The utilization of resources and the introduction of transmission delays occur exclusively when the task is offloaded to the edge server for execution. The offloading of the task

is denoted as

where B

NM represents the corresponding bandwidth allocation, consisting of

This task offloading is governed by the bandwidth constraint, signifying that

must be less than or equal to

, which is further constrained by

Utilizing Shannon’s formula enables the determination of the transmission rate[

14].

In the context provided, the channel gain of between MD and the AP is represented by g and

representing a distance from the MD and the nearest AP., and the power of additive Gaussian white noise is denoted by

. We define

as the distance between MD n and MEC server m, where

denotes the current location of m and

is the location of m[

15]. Consequently, the equations allow for the derivation of the task’s transmission delay and transmission energy consumption.

we set,

where P

max is the maximum transmit power when the battery.

- 4)

Computation Model

Computation time, measured time duration from request to submit result, it is a key QoS metric in offloading design. It’s affected by waiting, transmission, and processing delays. Energy consumption, crucial due to limited device batteries, includes data processing and transmission costs[

8].

- a)

Local Execution

Processing a task locally on a device incurs both a time delay and power consumption. If we denote the processing capacity of the IoT device as

, then the processing delay

for task m on MD n can be calculated using Equation 5. These factors contribute to the overall cost of local task execution and play a crucial role in decision-making for task offloading.

Similarly, the energy consumption for task m of user n during local computation is denoted by

and is defined by Equation 6. This equation captures the power consumed during the local execution of the task.

where

,

denotes the energy consumption and the power coefficient, which depends on the chip architecture[

16] respectively when the task is processed in the MD. Therefore, the computational cost is characterized as the weighted aggregate of both the energy consumed and the time taken for the completion of a task

assigned to node n. The overall cost is then computed as the weighted sum of local costs in the subsequent manner as shown in Equation 7.

Where α and β are constant weighting parameters corresponding to the time and power consumption of the task λ

nm and the sum of weights is always equal to 1, α + β = 1 and must fulfill 0 <= α <= 1 and 0 <= β <= 1. In this scenario, diverse user requirements can be accommodated through the adjustment of weights. For instance, prioritizing

over

indicates a higher emphasis on minimizing delay rather than energy consumption, making it suitable for latency- sensitive applications.

- b)

Algorithm for calculating local cost

Algorithm 1, which calculates the local cost, begins by setting the initial action for each device to local computation

and the system’s total cost to zero

. Following this initialization phase, the algorithm takes several parameters as input. These include the size of computation

, the number of CPU cycles required

) the local computation power of the device

and the decision weights (α and β). These parameters are used to determine the cost of local computation for each device.

|

Algorithm 1: calculate the cost |

| Require: N, , , , , α, β, |

| Ensure: |

| 1: ← 0 ▷ Set total system cost |

| 2: for n ∈ N do |

| 3: ▷ time to execute |

| 4: ← ▷ energy consumption |

| 5: ← ( ▷ Calculate cost |

| 6: ← + ▷ Update the cost |

| 7: end for |

| 8: return |

- c)

MEC Execution

When the decision unit opts to offload a task to an edge server (represented by

), it does so because the edge server’s computational resources significantly surpass those of the MD. The processing time per task on the edge server is denoted as

, which encompasses both transmission and computing delays. The computing delay is influenced by factors such as the edge server’s CPU frequency and other available resources. It’s important to note that in this study, we make the assumption that the size of the computed results is minimal. Consequently, the time required to download these results from the MEC server is considered negligible. Given these conditions, the processing time can be expressed using equation 8.

Similarly, the corresponding power cost for task

of user n is denoted by

and is defined as equation 10.

Where

is the power coefficient, The total system cost in edge computing is derived from two primary factors: the time required for computation and the associated power consumption. This can be expressed as:

The overall expense, denoted as

, to calculate a task

send from device n can be formulated as...

where

is considered when the

is not guaranteed when doing offloading.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of the key notations used consistently throughout this paper.

- 5).

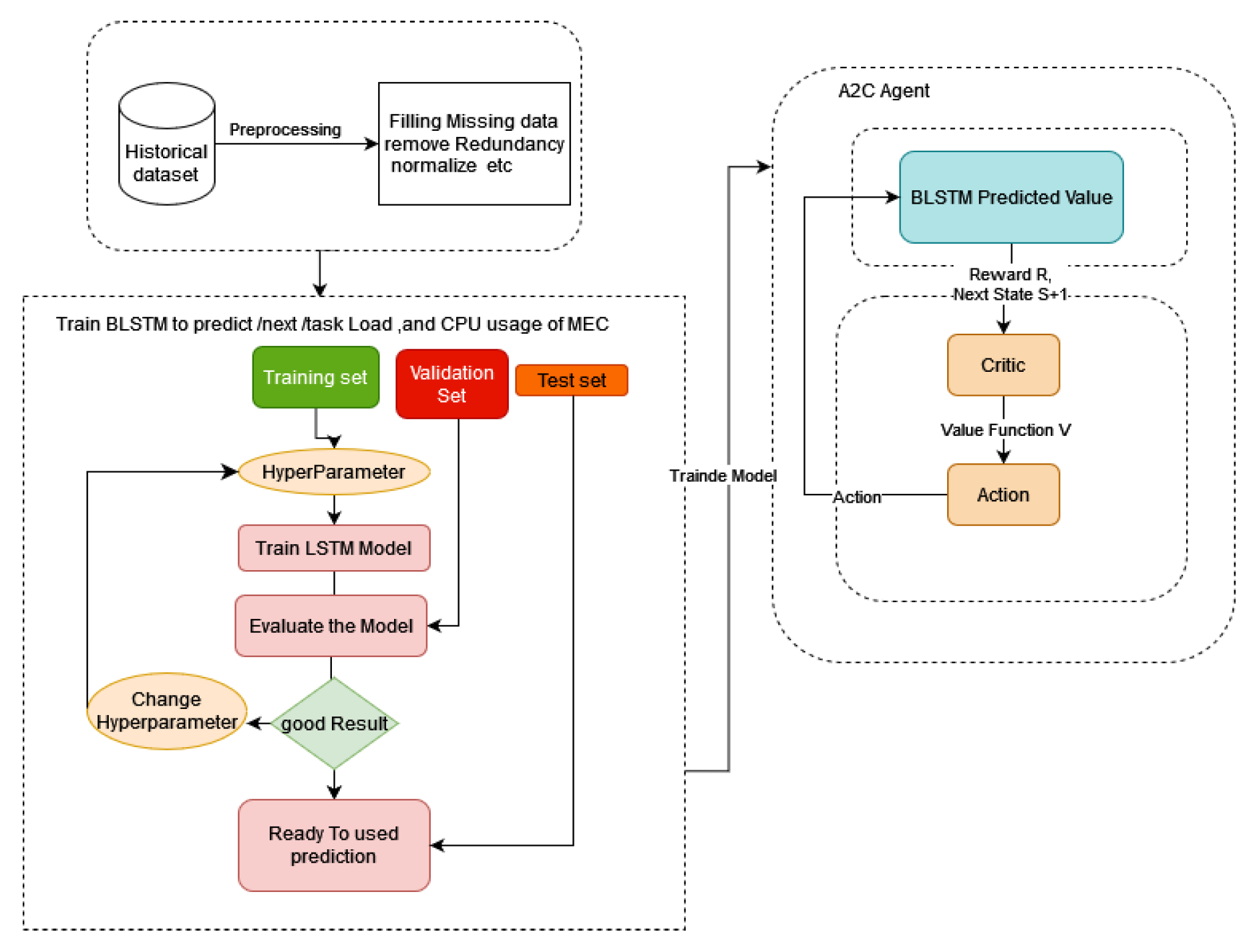

Prediction Model

Traditional RL-based task offloading systems make decisions reactively, leading to potential delays and failures. By analyzing historical patterns of task generation, server usage, and mobile device movements, our system can predict future resource needs and pre-allocate computing resources to optimal MEC nodes before tasks arrive, significantly reducing decision-making delays and task failures.

- 6).

Task Load Prediction Model

Using a trained LSTM model, our system predicts future task data by analyzing historical task sequences D1, D2, D3, from mobile devices. The model aims to minimize prediction error, enabling proactive resource allocation and service package loading before tasks arrive. and prediction of future MEC server loads using an LSTM model trained on historical CPU utilization data sequences H1, H2, .

The model outputs predicted server loads , identifying potentially idle servers

that can be prioritized for task offloading, thus preventing workload imbalances and enabling more efficient resource allocation decisions.

- B.

Offloading Algorithm Design

To dynamically adjust to changing conditions and make optimal choices, we’ve developed an innovative decision-making solution that combines two powerful techniques: BLSTM from deep learning and A2C from reinforcement learning. This integration results in a DRL based approach for task offloading, designed to anticipate and respond effectively to environmental shifts.

- 1).

Prediction phase (BLSTM)

During the Prediction Phase, as illustrated in

Figure 3, the algorithm forecasts future conditions such as CPU availability, upcoming task loads, and the nearest edge node. Upon arrival of an actual task, the system compares the predicted values with the real data for CPU, task, and node. If the discrepancy falls within an acceptable range, the task is offloaded to the location determined by the DRL Agent in the Decision Phase. However, if the error exceeds the set threshold, the Decision Phase reevaluates the offloading decision using the actual values. This new information is then incorporated into the historical dataset for future training. The training process of the BLSTM Net- works involves adjusting weights and biases to improve prediction accuracy.

- 2).

Decision Phase (A2C)

Each IoT device generates various tasks at different times, and when a new task is created, there is a delay in the system’s response to the decision request for that task. To optimize performance, the system uses information from a prediction phase before it receives real task information. A DRL model called A2C is used to make offloading decisions for newly arrived tasks. The A2C network consists of two sub-networks: an actor and a critic, with shared layers to simplify the model and speed up network convergence. The network structure of the model is shown in

Figure 3.

The edge server within A2C-BLSTM-based algorithm functions as a smart brain, where a RL agent interacts with the environment to learn optimal policies. The agent consists of two components: an actor, which defines a policy and performs actions based on observed states, and a critic, which evaluates the current policy and updates its parameters based on rewards from the environment[

17].

The A2C algorithm initializes an actor to interact with the environment, using BLSTM networks to predict system parameters and select actions based on policies. After executing actions, the algorithm captures states and rewards in a replay buffer for iterative learning. A critic network estimates the advantage function to evaluate the actor’s decisions, and both the policy and critic networks are refined through gradient-based optimization to improve decision-making and maximize cumulative rewards within the A2C ecosystem.

Figure 4.

Decision Phase of A2C Network.

Figure 4.

Decision Phase of A2C Network.

- C.

DRL Decision model Elements

- 1)

Environment State S

The state describes the environment and changes when the agent generates an action. In this model, each state consists of five pieces of information: task size (in bytes), deadline (in milliseconds), processing queue of the MD, transmission queue, and MEC processing queue information (all in bytes), and communication type (5G or Wi-Fi). The state is characterized as follows:

where

is the task size,

denotes the historical load level on each edge node,

is the task deadline, and

represent the processing state of devices, the transmission state of devices, and the MEC node state information for time slot t - 1, respectively. Additionally,

represents the transmission rate of the MD.

- 2).

Action a

The action space of this model comprised as a binary

Where N represents the computation server, and

determines whether a task

is processed at the MEC or locally. Specifically,

is local when

, and N is one of the MEC servers {1, 2, ..., M} when

. The agent will make decisions based on the task offloading strategy at each time step and receive rewards from the environment in the subsequent time step. When local and MEC processing are both possible, the choice should optimize either latency or energy efficiency. If neither option is suitable, the task should be discarded.

- 3).

Reward

After the agent executes an action, the reward serves as the environment’s feed- back to the agent. This reward, a numerical value, reflects the agent’s performance; at each time step (t + 1), the agent receives the reward and information about the updated state from the environment. Based on this feedback, the agent learns a policy (π), which is considered optimal (

) when consistently yielding the highest rewards. In this section, the costs and rewards are quantified based on local processing, remote processing, and task dropping to execute task λ(n). For every action, the system must choose between executing the task locally or offloading it to external resources.

α and β are weighting coefficients that balance the importance of processing time against energy consumption.

represents the penalty cost for exceeding the allocated time.

Equation 15 is applied to choose a minor action with lower cost value for all multi- devices capable of processing data locally and remotely. if the allocated server is wrong or busy, that task will be discarded. The cost associated with discarding the task is denoted as

, with a fixed value of 1. If the processing time surpasses the deadline, the algorithm imposes

. In time-sensitive systems, tasks are evaluated against predetermined deadlines. Those exceeding these limits may be discarded to maintain overall system efficiency. While minor delays are of- ten tolerable, the acceptable threshold varies based on task type and criticality. A penalty system quantifies the cost of delays, helping to prioritize timely task completion and optimize resource allocation. This approach balances the need for thorough processing with the demands of real-time responsiveness across diverse application scenarios. The penalty for breaching the deadline is defined as:

When a task meets its deadline,

becomes 0, having no impact on the cost. However, for tasks exceeding the deadline, a penalty is applied using a squared function, which amplifies the effect of larger delays. To address the negligible impact of delays less than 1 second due to the squaring effect, time calculations in this range are processed in milliseconds. For instance, a 0.1second delay translates to a

value of 10,000ms rather than 0.01. This approach ensures that even small delays contribute meaningfully to the penalty calculation. For offloading tasks

, the costs

and

are calculated using Equations 17 and 18, respectively. These equations account for the specific characteristics of edge processing and its associated penalties.

At each time slot t, the agent is given an immediate reward

for choosing action A. Typically, this reward function is inversely related to the cost function. The primary objective of the optimization problem is to minimize overall costs.

The objective of this research is to simultaneously reduce costs and increase re- wards, optimizing the system’s overall performance and efficiency.

- D.

Prediction Based Decision Task offloading framework

Our algorithm combines A2C (Actor-Critic) with BLSTM (Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory) to optimize task offloading in MEC environments. The system makes offloading decisions based on both predicted and actual server loads, choosing between edge processing and local execution. With probability ϵ, the agent selects minimum- cost actions; otherwise, it follows predicted or mathematical solutions with probability 1 − ϵ. The optimal policy

minimizes the expected long-term cost:

, where the total reward is calculated as

The model continuously updates through policy gradients and advantage estimates, improving its decision-making capabilities over time.

|

Algorithm 2: Proposed A2C-BLSTM-Based Task Offloading Decision Algorithm |

| 1: Input: Task in each time slot |

| 2: Output: Optimal offloading decision and total cost |

| 3: Initialize: |

| 4: Actor-Critic model and related parameters (γ) |

| 5: LSTM model for task prediction |

| 6: Error threshold ϵ |

| 7: Maximum tolerance time ψ |

| 8: for episode e = 1 to M do |

| 9: Initialize sequence s sequence |

| 10: for time slot t = 1 to T do |

| 11: Predict Load BLSTM |

| 12: Predict Task |

| 13: Wait for Real task (n) |

| 14: With probability 1 − ϵ, select mathematical A or predicted A |

| 15: δ =real task load ▷ real task load |

| 16: if δ > ϵ then |

| 17: for each m = 1 to M do |

| 18: [m]= |

| 19: end for |

| 20: |

| 21: if ≤ ψ then |

| 22: ▷ Select the edge server with minimum load |

| 23: else |

| 24: ▷ Select to process the task locally |

| 25: end if |

| 26: else |

| 27: Select → Predic Action (, ) |

| 28: if Predic Action ≤ ψ then |

| 29: = selected ▷ Select the edge server to processed the task |

| 30: else |

| 31: ▷ Select to process the task locally |

| 32: end if |

| 33: end if |

| 34: Execute action at (local or MEC) |

| 35: Calculate the cost of the action taken: |

| 36: if then |

| 37: Calculate local cost: ▷ Eq. 15 |

| 38: else |

| 39: Calculate MEC cost: ▷ Eq. 17 |

| 40: Receive reward = ▷ Reward is the negative cost |

| 41: Observe next state |

| 42: Calculate advantages: |

| 43: +V () |

| 44: Update Critic: Minimize |

| 45: Update Actor: Use policy gradient |

| 46: end for |

| 47: end for |

- 2.

Experimental Result and Discussion

We use PYTHON simulation to evaluate the performance of our proposed algorithm. The A2C-BLSTM algorithm is conducted using Keras plus TensorFlow[

18], where Keras is adopted to build the DNN training model and TensorFlow supplies the back- ground support. We utilize a dataset from Google Cluster[

13], which contains details about task arrival times, data sizes, processing times, and deadlines of the task. Tasks vary from complex big data analysis to simpler image processing, each with unique processing requirements and data volumes. We preprocess and normalize the data based on task characteristics to ensure compatibility with our model, accounting for the interrelation between processing density, time, and data size across different task types. Based on similar research in the field[

13,

19,

20], the authors have recommended and used specific simulation parameters to evaluate task offloading solutions. Accordingly, we have adopted and simulated their recommended parameters, as shown in

Table 2

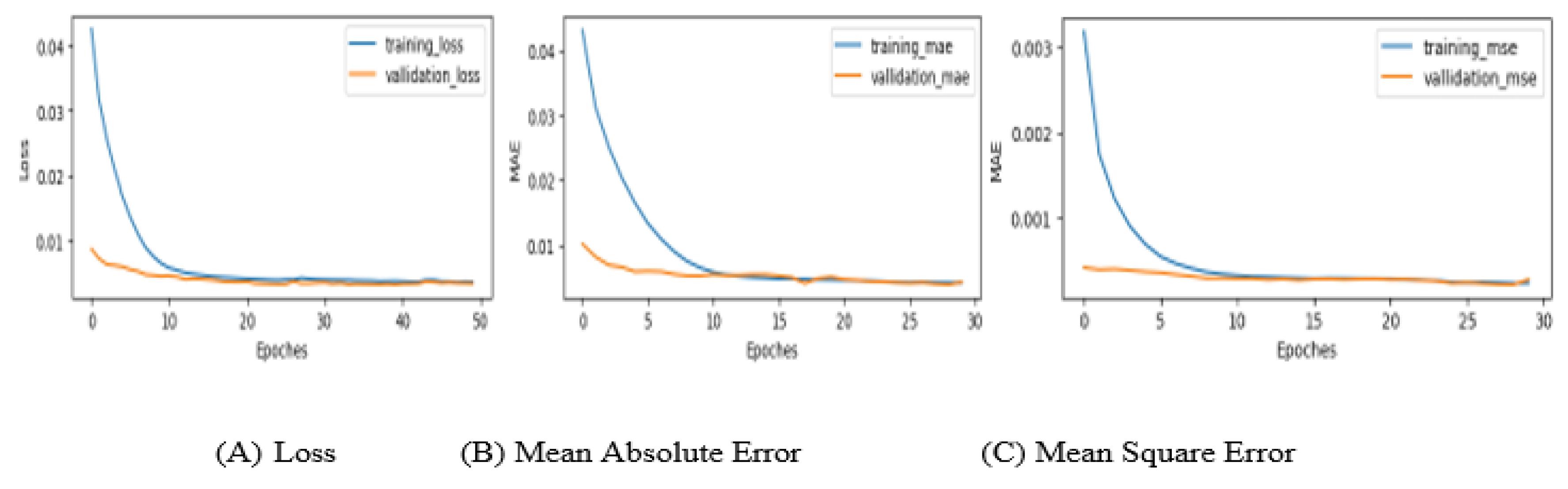

Figure 5 shows that the model that used to predict the task load and CPU usage is well fitted, the LOSS decreases for larger epoch values hence it shows how the model starts to optimize properly heavily for a larger epoch. The model learns any pattern or context and adapts the workload fluctuation. This will lead to that out validation LOSS will decrease for longer epochs.

Prediction on Historical Data from the Google Cluster Dataset

The proposed model demonstrates strong predictive accuracy when compared against actual values using a historical data dataset and is applied to authentic cloud data sets, significantly impacting accuracy and performance.

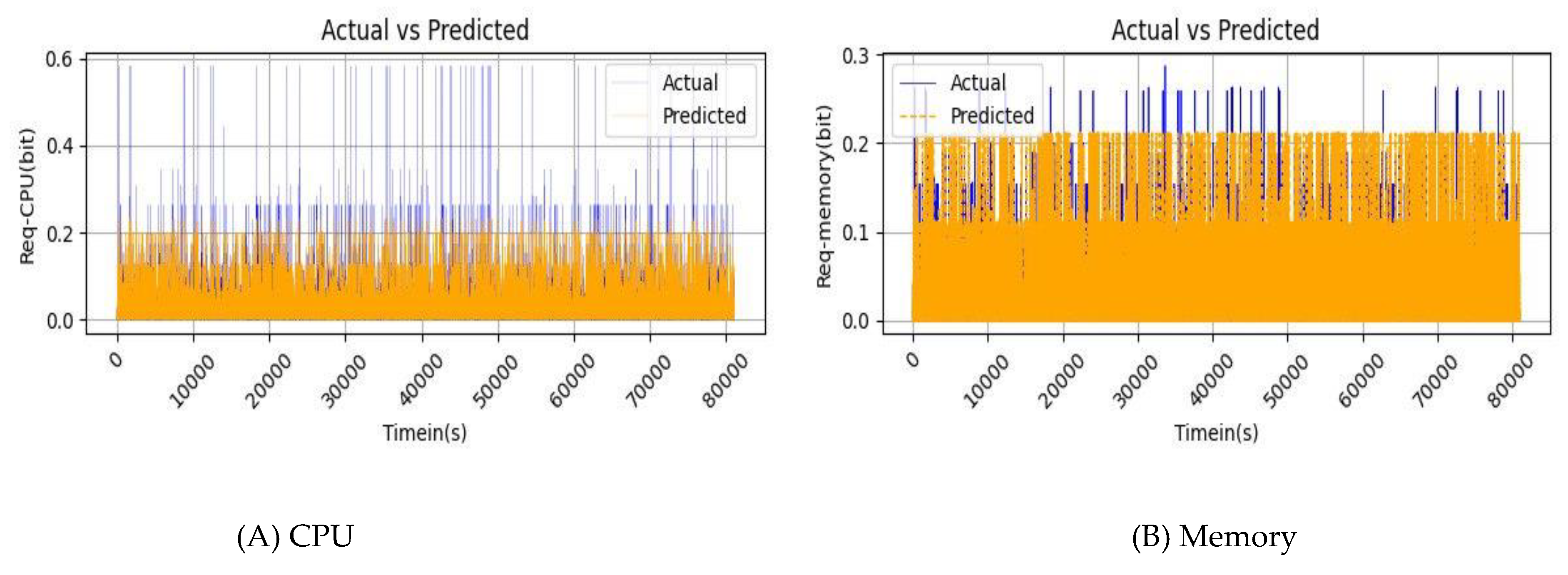

Figures 6a and

6b illustrate the prediction outcomes of the BLSTM model, contrasting actual data (blue line) with predicted data (orange line). The close alignment between the two lines (actual and predicted) in these figures indicates the robust fit of the proposed model.

- B.

Discussion on Performance Comparison

To evaluate the performance of our A2C-BLSTM-based scheme in real-time for IoT, we compared our model with three benchmark algorithms: MADDPG[

21], MAAC-based algorithm[

17], and DQN-based algorithm[

22]. We trained our model and the other three algorithms simultaneously in the same environment, including A2C-BLSTM with prediction and A2C without prediction.

These benchmark algorithms are commonly employed in MDP scenarios. The DQN algorithm operates as a single agent for dependent computation offloading, while MAD- DPG represents a state-of-the-art Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL) framework. The MAAC algorithm, like our approach, utilizes a multi-agent reinforcement learning strategy based on the actor-critic method. Our comparison focused on key performance indicators: task drop rate, energy consumption, and task execution delay. To assess prediction accuracy, we employed Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). For optimization evaluation, we examined total system cost, total reward, and task throughput volume. The experimental setup involved eight edge servers and 80 terminal devices. As illustrated in

Figure 6, our model consistently outperformed the benchmark methods across all metrics. This superior performance can be attributed to the model’s effective integration of predictive and decision-making techniques, which optimally utilize task characteristics and edge server load information.

- 1)

Impact of Task Number

Previous studies have demonstrated that the task arrival rate significantly affects the system state due to the random generation of tasks. In this paper, we utilize data from real scenarios for data streams. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on task arrival rates to evaluate the system state, our study uses different time slots to assess the impact of the number of tasks on system cost, average task delay, and task discard rate.

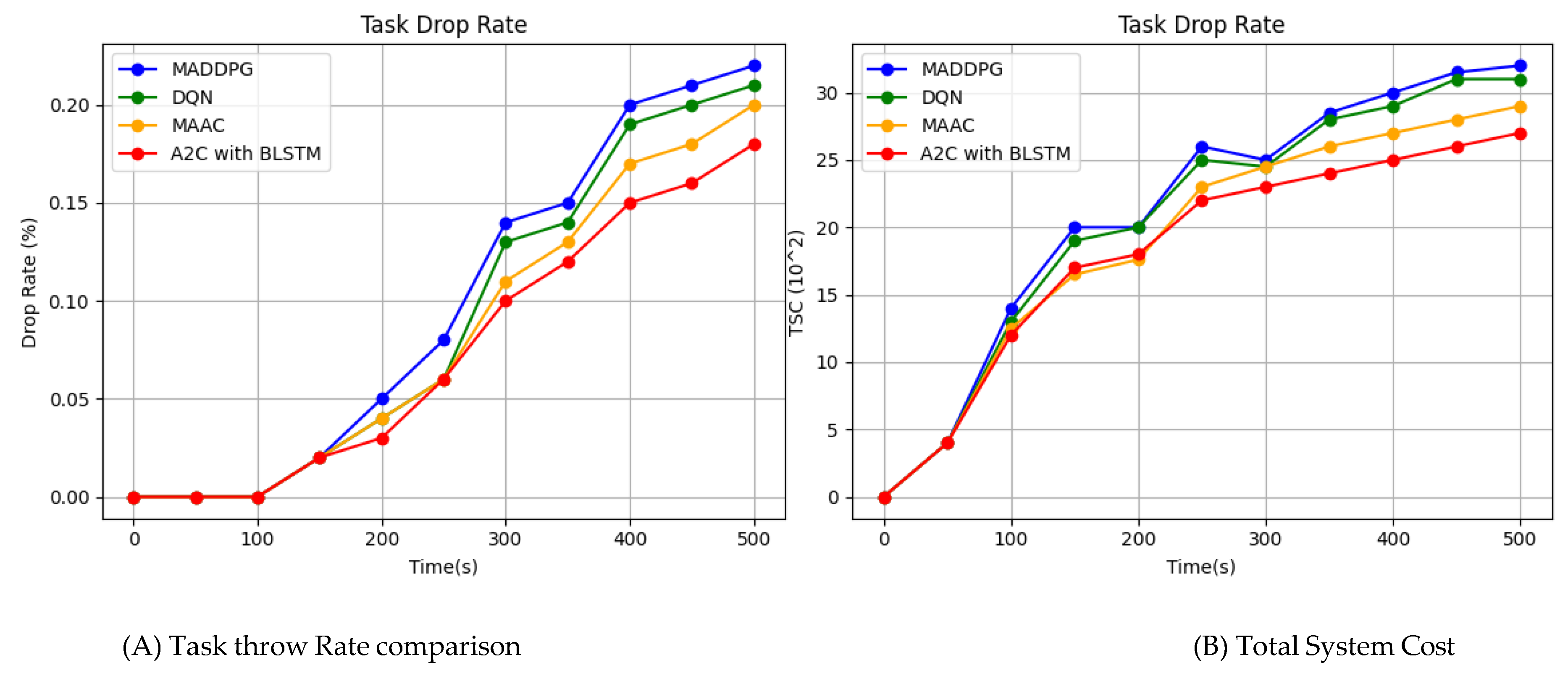

Specifically, we set the time slots in the dataset to T = 0, T = 100, 200, and 500 and compare the performance of MADDPG, MAAC, DQN, and our A2C-BLSTM scheme under these different time slots. The experimental results are presented in

Figure 7.

Figure 7a presents a comprehensive comparison of the task rejection ratios across four different schemes. As the number of tasks increases, the rejection ratio for all schemes also rises. However, our scheme demonstrates a significantly lower increase compared to the other schemes, indicating better performance in terms of task acceptance ratio and a lower rejection rate. The proposed model’s ability to accept more tasks stems from its intelligent assignment of tasks to servers that are optimally matched in terms of resource requirements and availability. This approach not only preserves resources for future use but also allows for more tasks to be accepted, reducing the overall time to complete tasks, which is a critical factor for real-time communication scenarios. A high acceptance rate is beneficial as it leads to higher resource utilization and reduces system idle time. Consequently, our proposed work outperforms other methods in terms of cost (latency and power consumption), demonstrating its effectiveness in improving the proposed MEC system.

The task throw rate is a crucial metric directly impacting QoS. A low task rejection ratio indicates high QoS. The proposed A2C-BLSTM-based scheme employs a robust mechanism for selecting the best servers by assessing CPU usage and task requirements, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the MEC system. Additionally, it leverages intelligent resource allocation strategies, resulting in an increased task acceptance rate while maintaining QoS. A higher acceptance rate typically leads to higher average resource utilization relative to cost. The results demonstrate that our model achieves a higher utilization rate than other algorithms, underscoring the effectiveness of the proposed approach in improving MEC system performance.

Figure 7b also presents a comprehensive comparison of the cost ratios of three different schemes as the number of tasks increases. It can be observed that the cost ratio for all schemes increases with the number of tasks. However, the proposed scheme exhibits a significantly lower increase compared to the other schemes, indicating better performance in terms of cost ratio. Additionally, it has a significantly lower task rejection rate compared to the MADDPG, MAAC and DQN algorithms, implying that it accepts more tasks for offloading and enhances the QoS of the MEC system. The key factor enabling the proposed one to achieve this is its ability to intelligently assign tasks to servers that are optimally matched in terms of resource requirements and availability, thus minimizing overall cost and maximizing resource utilization of the MEC system.

- 2)

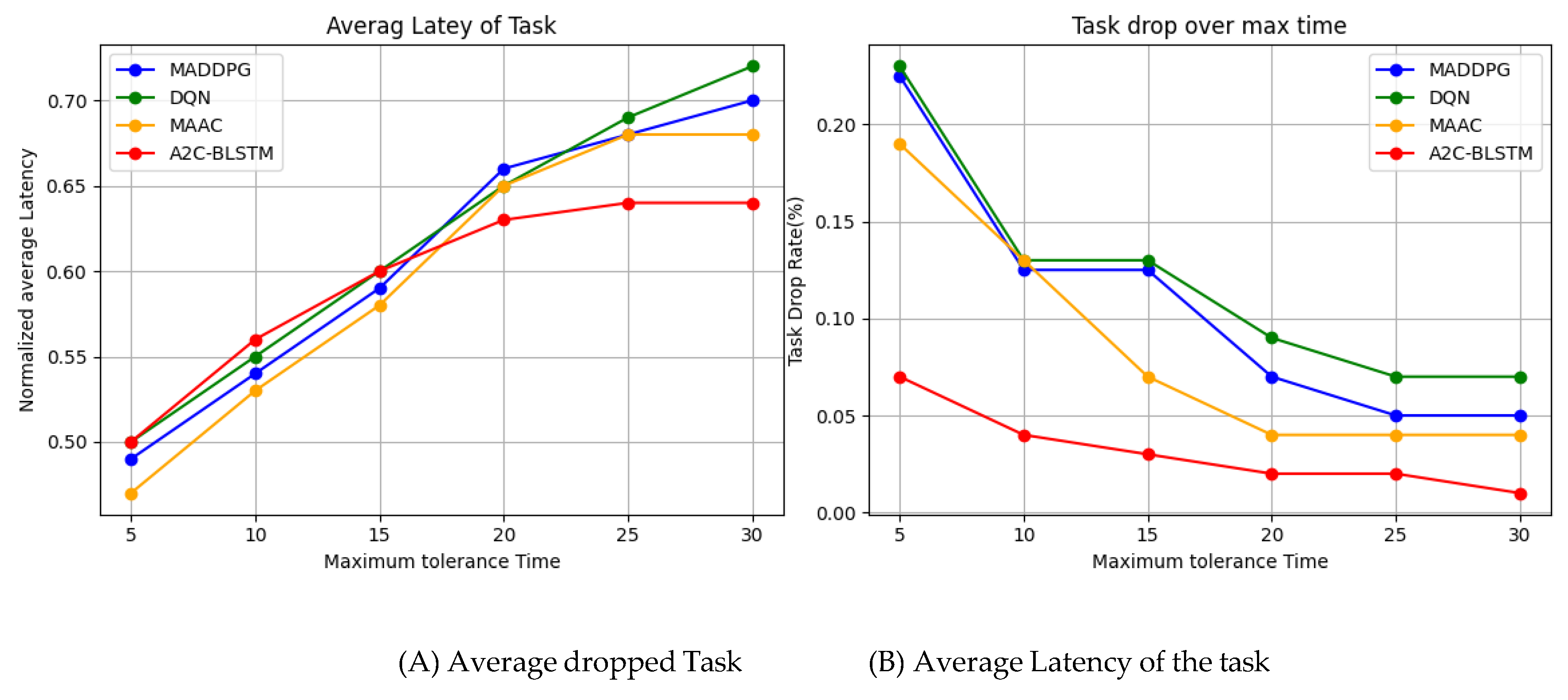

Impacts of Max tolerable time

Figure 8a illustrates our system’s performance across varying maximum tolerance latencies and algorithm configurations. The data reveals an inverse relationship between maximum tolerance latency and task drop rate for all four methods tested. As the tolerance increases from 5 to 30 seconds, task drop rates decrease markedly. Our proposed A2C-BLSTM algorithm consistently maintains a lower task drop rate compared to its counterparts. This advantage is particularly pronounced at lower maximum tolerance latencies, highlighting our algorithm’s efficacy for time-critical tasks. Conversely,

Figure 8b demonstrates that average system latency increases for all methods as maximum tolerance latency extends from 5 to 30 seconds. This trend is attributed to task completion dynamics: at shorter tolerance levels, many tasks fail to complete, whereas longer tolerances allow more tasks to be processed and transmitted, resulting in higher aver- age system latencies.

- 3)

Impacts of Prediction

The newly generated tasks demand optimal allocation of computational resources, which is achieved through a decision model. From the moment of task generation until the al- location decision is made, these tasks experience queuing and decision response delays within the cache queue. Our system employs a BLSTM prediction model to forecast incoming tasks based on historical data. This prediction then feeds into the decision model, which proposes an offloading scheme for task assignment. For the purpose of our experiment, we analyze the performance using the first 500 tasks generated. This approach combines predictive modeling with decision-making to optimize resource allocation and task management in a dynamic computational environment.

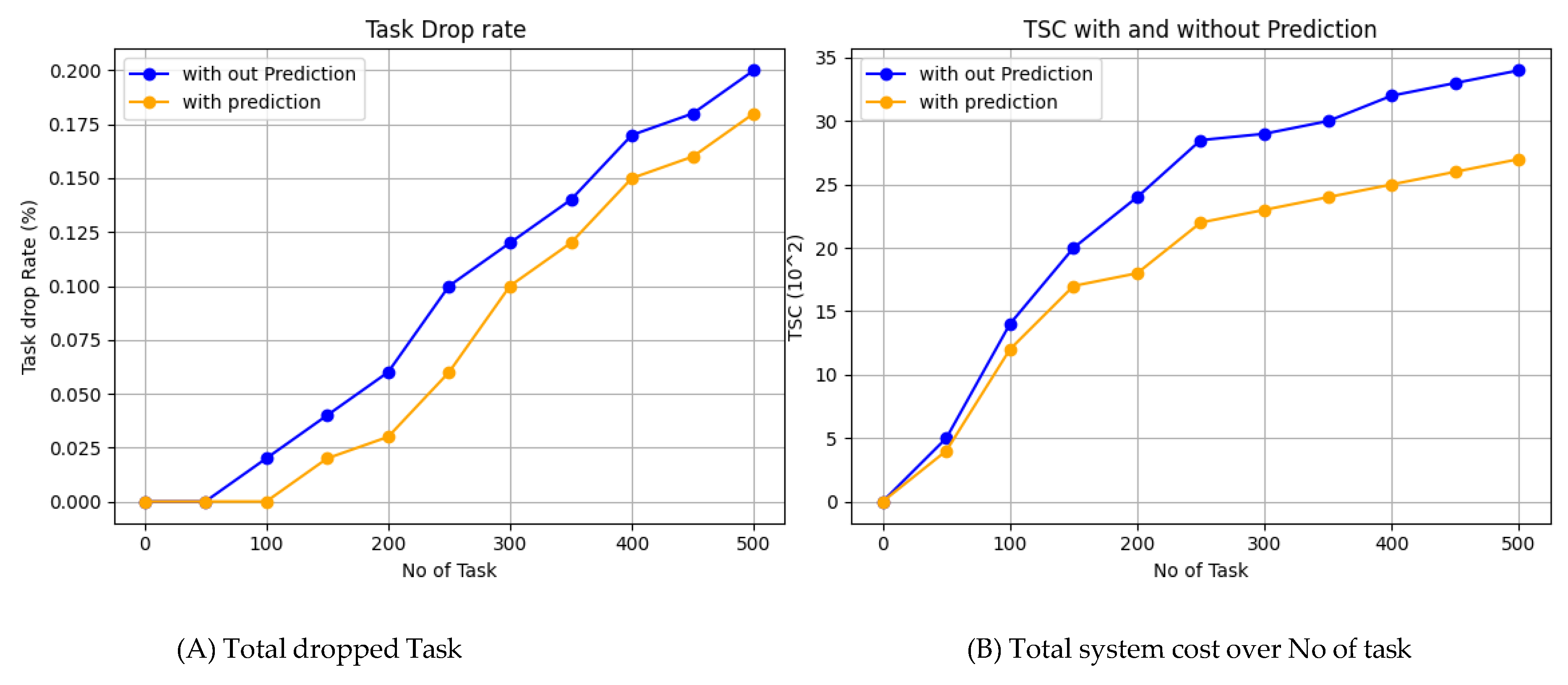

The results depicted in

Figure 9 considerable advantages of utilizing prediction in task execution, comparing total task drop rate and system cost when doing prediction with the pro- posed algorithm and with just only implementing A2C without BLSTM prediction for decision making. Both graphs show a linear increase in task drop and cost as the number of tasks grows, but these increases are significantly steeper without prediction. The blue lines, representing execution without prediction, indicate higher task drop and costs than the orange lines, which represent a BLSTM prediction based A2C decision making to offload and a predicted resource allocation. Using prediction reduces both tasks drop rate and system cost, resulting in more efficient and cost-effective task management. These benefits become increasingly pronounced with a higher number of tasks, underscoring the scalability and strategic importance of predictive mechanisms in task management.

When comparing the results of prediction-based approaches versus those without pre- diction, it is evident that our method performs significantly better overall. However, our scheme requires additional energy initially to train the model until it reaches an error-tolerant threshold during prediction. This increased energy consumption occurs only during the initial deployment and training stage. Additionally, the training process is conducted on the MEC server and macro base stations, ensuring that this initial energy expenditure does not significantly impact the overall performance of the system.

Once the model is trained and deployed, the energy requirements stabilize, and the benefits of the prediction-based approach become more pronounced. These benefits include improved task offloading efficiency, reduced latency, and higher system reliability. By leveraging the computational resources of the MEC server and macro base stations, we ensure that the end-user experience remains unaffected during the training phase. This strategic deployment of training processes helps maintain optimal system performance while reaping the long-term advantages of our enhanced predictive model.