Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Rheology

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DHBCs | double hydrophilic block copolymers |

| POEGMA | poly[oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate] |

| PVBTMAC | poly(vinyl benzyl trimethylammonium chloride) |

| SAOS | small amplitude oscillatory shear |

| Tginter | interfacial glass transition temperature |

| RAFT | reversible addition−fragmentation chain transfer |

| Tg | glass transition temperature |

| LVR | linear viscoelastic regime |

| CY | Carreau-Yasuda model |

| MC | modified Cross model |

| |G*| | complex shear moduli |

| G' | shear storage moduli |

| G'' | shear loss moduli |

| η0 | zero-shear viscosity |

| tTs | time-temperature superposition |

| αT | horizontal shift factor |

| f(Tg) | fractional free volume at Tg |

| αf | thermal expansion coefficient of free volume at Tg |

| m* | fragility |

| Eg | apparent activation energy |

| PS | Polystyrene |

References

- Tsukahara, Y.; Kohjiya, S.; Tsutsumi, K.; Okamoto, Y. On the intrinsic viscosity of poly (macromonomer) s. Macromolecules 1994, 27 (6), 1662-1664. [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, D.; Zhang, Y.; Pakula, T.; Sheiko, S. S.; Matyjaszewski, K. Densely-grafted and double-grafted PEO brushes via ATRP. A route to soft elastomers. Macromolecules 2003, 36 (18), 6746-6755. [CrossRef]

- Vlassopoulos, D.; Fytas, G.; Loppinet, B.; Isel, F.; Lutz, P.; Benoit, H. Polymacromonomers: Structure and dynamics in nondilute solutions, melts, and mixtures. Macromolecules 2000, 33 (16), 5960-5969. [CrossRef]

- Kapnistos, M.; Vlassopoulos, D.; Roovers, J.; Leal, L. Linear rheology of architecturally complex macromolecules: Comb polymers with linear backbones. Macromolecules 2005, 38 (18), 7852-7862. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Xia, Y.; McKenna, G. B.; Kornfield, J. A.; Grubbs, R. H. Linear rheological response of a series of densely branched brush polymers. Macromolecules 2011, 44 (17), 6935-6943. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, W. F.; Burdyńska, J.; Vatankhah-Varnoosfaderani, M.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Paturej, J.; Rubinstein, M.; Dobrynin, A. V.; Sheiko, S. S. Solvent-free, supersoft and superelastic bottlebrush melts and networks. Nature materials 2016, 15 (2), 183-189. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Chen, D.; McKenna, G. B. Re-visiting the “consequences of grafting density on the linear viscoelastic behavior of graft polymers”. Polymer 2020, 186, 121992. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Leo, C. M.; Santiago, P.; Kennemur, J. G. Unraveling the Linear-to-Bottlebrush Transition by Linear Viscoelastic Response to Increasing Side Chain Length. Macromolecules 2025. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, D.; McLeish, T.; Crosby, B.; Young, R.; Fernyhough, C. Molecular rheology of comb polymer melts. 1. Linear viscoelastic response. Macromolecules 2001, 34 (20), 7025-7033. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Fetters, L. J.; Archer, L. A. Stress relaxation of branched polymers. Macromolecules 2005, 38 (26), 10763-10771. [CrossRef]

- Roovers, J.; Graessley, W. Melt rheology of some model comb polystyrenes. Macromolecules 1981, 14 (3), 766-773. [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Witt, C. L.; Fatima, R.; Uchiyama, T.; Pande, V.; Song, D.-P.; Fei, H.-F.; Yavitt, B. M.; Watkins, J. J. Opportunities in Bottlebrush Block Copolymers for Advanced Materials. ACS nano 2024, 19 (2), 1884-1910. [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Zhang, B.; Shen, L.; Bates, F. S.; Lodge, T. P. Core–shell gyroid in ABC bottlebrush block terpolymers. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2022, 144 (47), 21719-21727. [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Dong, Q.; Liang, R.; Xue, Y.; Zhong, M.; Li, W. Hierarchical self-assembly of ABC-type bottlebrush copolymers. Macromolecules 2023, 56 (14), 5470-5481. [CrossRef]

- Detappe, A.; Nguyen, H. V.-T.; Jiang, Y.; Agius, M. P.; Wang, W.; Mathieu, C.; Su, N. K.; Kristufek, S. L.; Lundberg, D. J.; Bhagchandani, S. Molecular bottlebrush prodrugs as mono-and triplex combination therapies for multiple myeloma. Nature nanotechnology 2023, 18 (2), 184-192. [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Dutta, S.; Kamble, Y.; Patel, B. B.; Wade, M. A.; Rogers, S. A.; Diao, Y.; Guironnet, D.; Sing, C. E. Materials design of highly branched bottlebrush polymers at the intersection of modeling, synthesis, processing, and characterization. Chemistry of Materials 2022, 34 (5), 1990-2024. [CrossRef]

- Lapkriengkri, I.; Albanese, K. R.; Rhode, A.; Cunniff, A.; Pitenis, A. A.; Chabinyc, M. L.; Bates, C. M. Chemical Botany: Bottlebrush Polymers in Materials Science. Annual Review of Materials Research 2024, 54 (1), 27-46. [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Choudhury, C. K.; Luzinov, I.; Kuksenok, O. Recent advances towards applications of molecular bottlebrushes and their conjugates. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 2019, 23 (1), 50-61. [CrossRef]

- Zardalidis, G.; Pipertzis, A.; Mountrichas, G.; Pispas, S.; Mezger, M.; Floudas, G. Effect of polymer architecture on the ionic conductivity. Densely grafted poly (ethylene oxide) brushes doped with LiTf. Macromolecules 2016, 49 (7), 2679-2687.

- Pipertzis, A.; Kafetzi, M.; Giaouzi, D.; Pispas, S.; Floudas, G. A. Grafted Copolymer Electrolytes Based on the Poly (acrylic acid-co-oligo ethylene glycol acrylate)(P (AA-co-OEGA)) Ion-Conducting and Mechanically Robust Block. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2022, 4 (10), 7070-7080. [CrossRef]

- Rolland, J.; Brassinne, J.; Bourgeois, J.-P.; Poggi, E.; Vlad, A.; Gohy, J.-F. Chemically anchored liquid-PEO based block copolymer electrolytes for solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2014, 2 (30), 11839-11846. [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Bates, F. S.; Lodge, T. P. Superlattice by charged block copolymer self-assembly. Nature communications 2019, 10 (1), 2108. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zheng, C.; Sims, M. B.; Bates, F. S.; Lodge, T. P. Influence of charge fraction on the phase behavior of symmetric single-ion conducting diblock copolymers. ACS Macro Letters 2021, 10 (8), 1035-1040. [CrossRef]

- Pispas, S. Double hydrophilic block copolymers of sodium (2-sulfamate-3-carboxylate) isoprene and ethylene oxide. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2006, 44 (1), 606-613.

- Mountrichas, G.; Pispas, S. Novel double hydrophilic block copolymers based on poly (p-hydroxystyrene) derivatives and poly (ethylene oxide). Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2007, 45 (24), 5790-5799. [CrossRef]

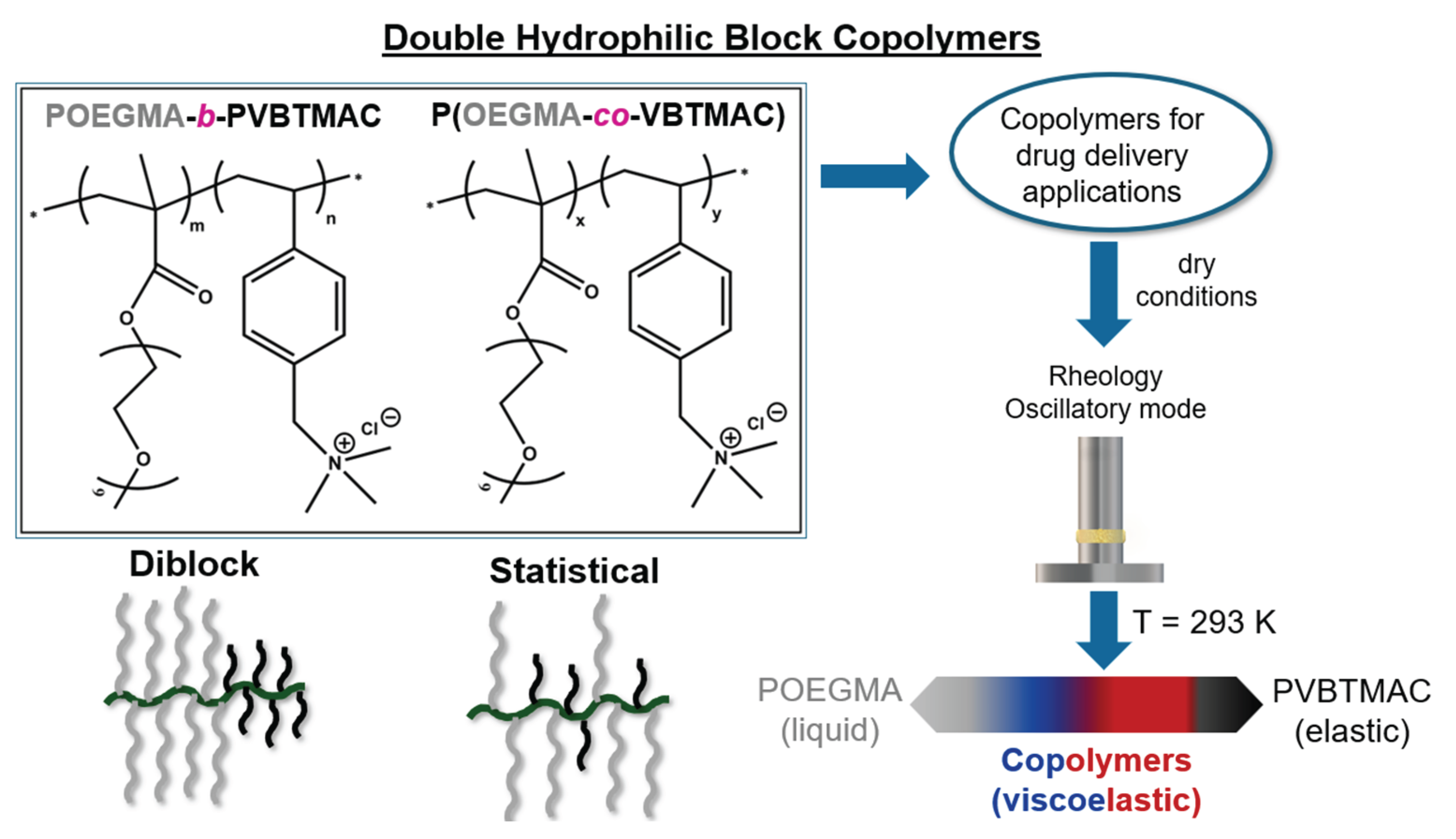

- Chroni, A.; Forys, A.; Sentoukas, T.; Trzebicka, B.; Pispas, S. Poly [(vinyl benzyl trimethylammonium chloride)]-based nanoparticulate copolymer structures encapsulating insulin. European Polymer Journal 2022, 169, 111158. [CrossRef]

- Chroni, A.; Forys, A.; Trzebicka, B.; Alemayehu, A.; Tyrpekl, V.; Pispas, S. Poly [oligo (ethylene glycol) methacrylate]-b-poly [(vinyl benzyl trimethylammonium chloride)] Based Multifunctional Hybrid Nanostructures Encapsulating Magnetic Nanoparticles and DNA. Polymers 2020, 12 (6), 1283. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tahami, K.; Singh, J. Smart polymer based delivery systems for peptides and proteins. Recent patents on drug delivery & formulation 2007, 1 (1), 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Pipertzis, A.; Chroni, A.; Pispas, S.; Swenson, J. Molecular Dynamics and Self-Assembly in Double Hydrophilic Block and Random Copolymers. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2024, 128 (45), 11267-11276. [CrossRef]

- Moad, G.; Rizzardo, E.; Thang, S. H. Radical addition–fragmentation chemistry in polymer synthesis. Polymer 2008, 49 (5), 1079-1131. [CrossRef]

- Skandalis, A.; Sentoukas, T.; Selianitis, D.; Balafouti, A.; Pispas, S. Using RAFT Polymerization Methodologies to Create Branched and Nanogel-Type Copolymers. Materials 2024, 17 (9), 1947. [CrossRef]

- Ferry, J. D. Viscoelastic properties of polymers; John Wiley & Sons, 1980.

- Carreau, P. J. Rheological equations from molecular network theories. Transactions of the Society of Rheology 1972, 16 (1), 99-127. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K. Investigation of the analogies between viscometric and linear viscoelastic properties of polystyrene fluids. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1979.

- Cross, M. M. Rheology of non-Newtonian fluids: a new flow equation for pseudoplastic systems. Journal of colloid science 1965, 20 (5), 417-437. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. H.; Narimissa, E.; Poh, L.; Shahid, T. Modeling elongational viscosity and brittle fracture of polystyrene solutions. Rheologica Acta 2021, 60 (8), 385-396. [CrossRef]

- Plazek, D. J.; Ngai, K. L. Correlation of polymer segmental chain dynamics with temperature-dependent time-scale shifts. Macromolecules 1991, 24 (5), 1222-1224. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; McKenna, G. B. Correlation between dynamic fragility and glass transition temperature for different classes of glass forming liquids. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2006, 352 (28-29), 2977-2985. [CrossRef]

- Angell, C. Spectroscopy simulation and scattering, and the medium range order problem in glass. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 1985, 73 (1-3), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Pipertzis, A.; Hossain, M. D.; Monteiro, M. J.; Floudas, G. Segmental dynamics in multicyclic polystyrenes. Macromolecules 2018, 51 (4), 1488-1497. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; McKenna, G. B. New insights into the fragility dilemma in liquids. The Journal of chemical physics 2001, 114 (13), 5621-5630. [CrossRef]

- Böhmer, R.; Ngai, K. L.; Angell, C. A.; Plazek, D. J. Nonexponential relaxations in strong and fragile glass formers. The Journal of chemical physics 1993, 99 (5), 4201-4209. [CrossRef]

- Kunal, K.; Robertson, C. G.; Pawlus, S.; Hahn, S. F.; Sokolov, A. P. Role of chemical structure in fragility of polymers: a qualitative picture. Macromolecules 2008, 41 (19), 7232-7238. [CrossRef]

- Floudas, G.; Štepánek, P. Structure and dynamics of poly (n-decyl methacrylate) below and above the glass transition. Macromolecules 1998, 31 (20), 6951-6957. [CrossRef]

- Pipertzis, A.; Hess, A.; Weis, P.; Papamokos, G.; Koynov, K.; Wu, S.; Floudas, G. Multiple segmental processes in polymers with cis and trans stereoregular configurations. ACS Macro Letters 2018, 7 (1), 11-15. [CrossRef]

- Pipertzis, A.; Skandalis, A.; Pispas, S.; Floudas, G. Nanophase Segregation Drives Heterogeneous Dynamics in Amphiphilic PLMA-b-POEGMA Block-Copolymers with Densely Grafted Architecture. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 2024, 225 (19), 2400180.

- Mierzwa, M.; Floudas, G.; Neidhöfer, M.; Graf, R.; Spiess, H. W.; Meyer, W. H.; Wegner, G. Constrained dynamics in supramolecular structures of poly (p-phenylenes) with ethylene oxide side chains: A combined dielectric and nuclear magnetic resonance investigation. The Journal of chemical physics 2002, 117 (13), 6289-6299. [CrossRef]

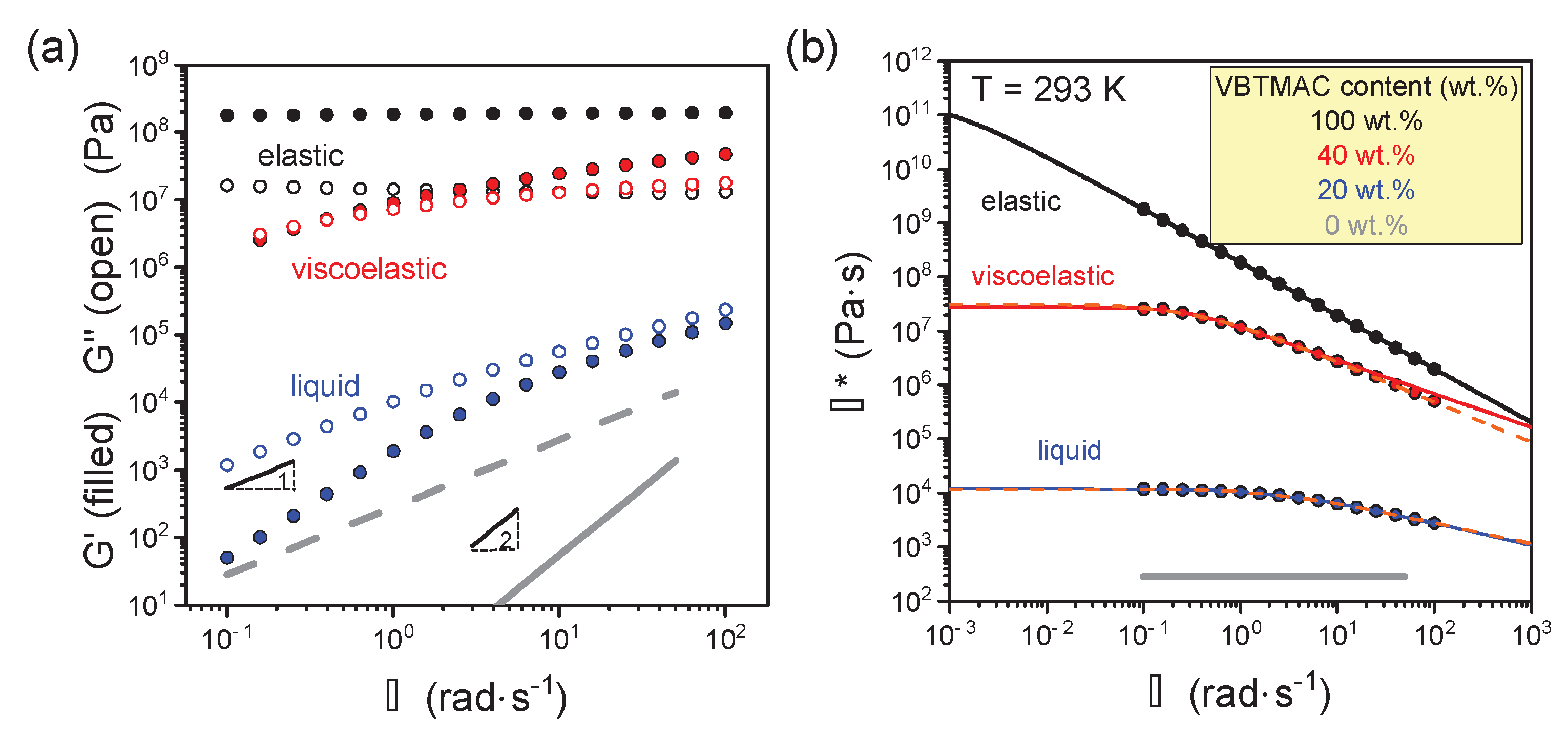

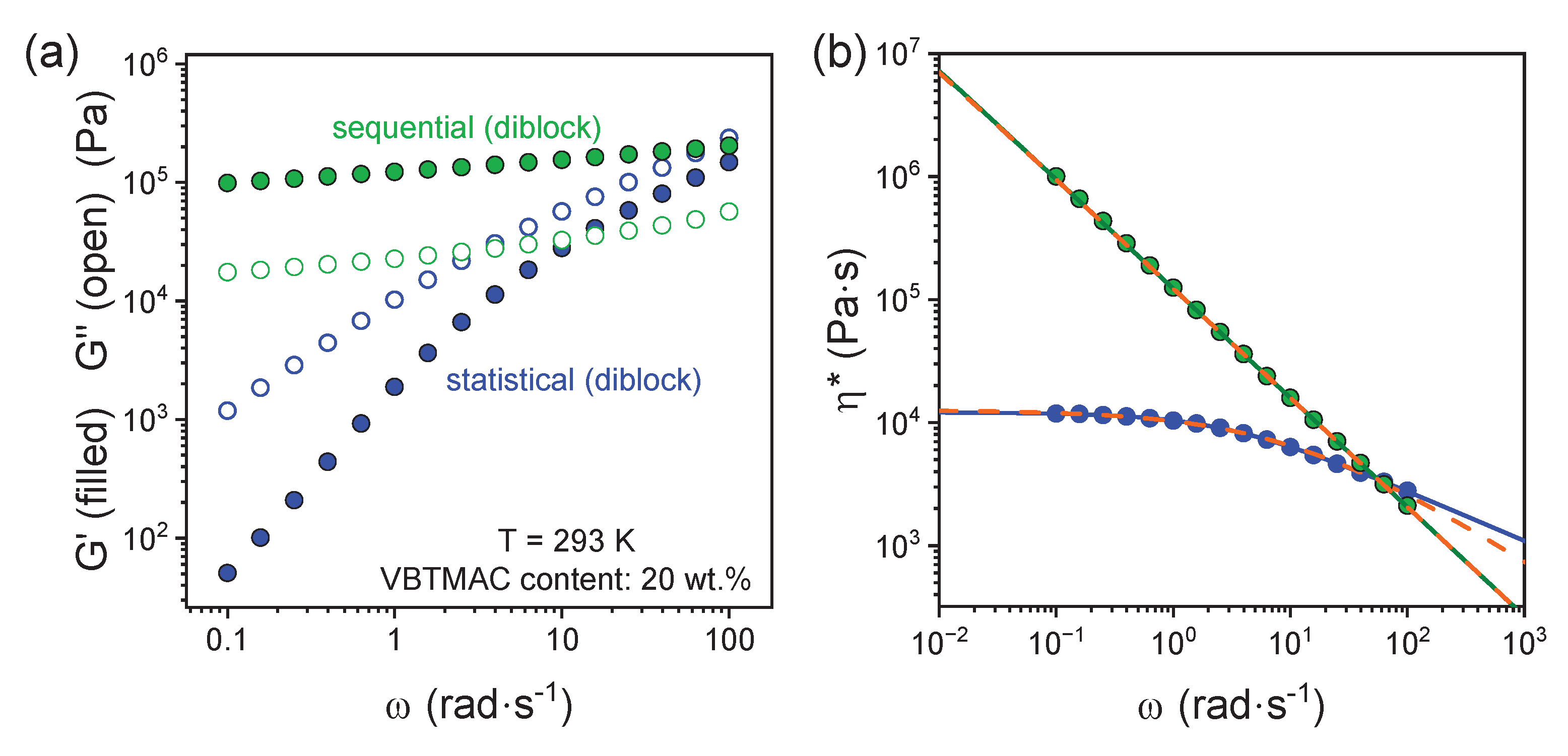

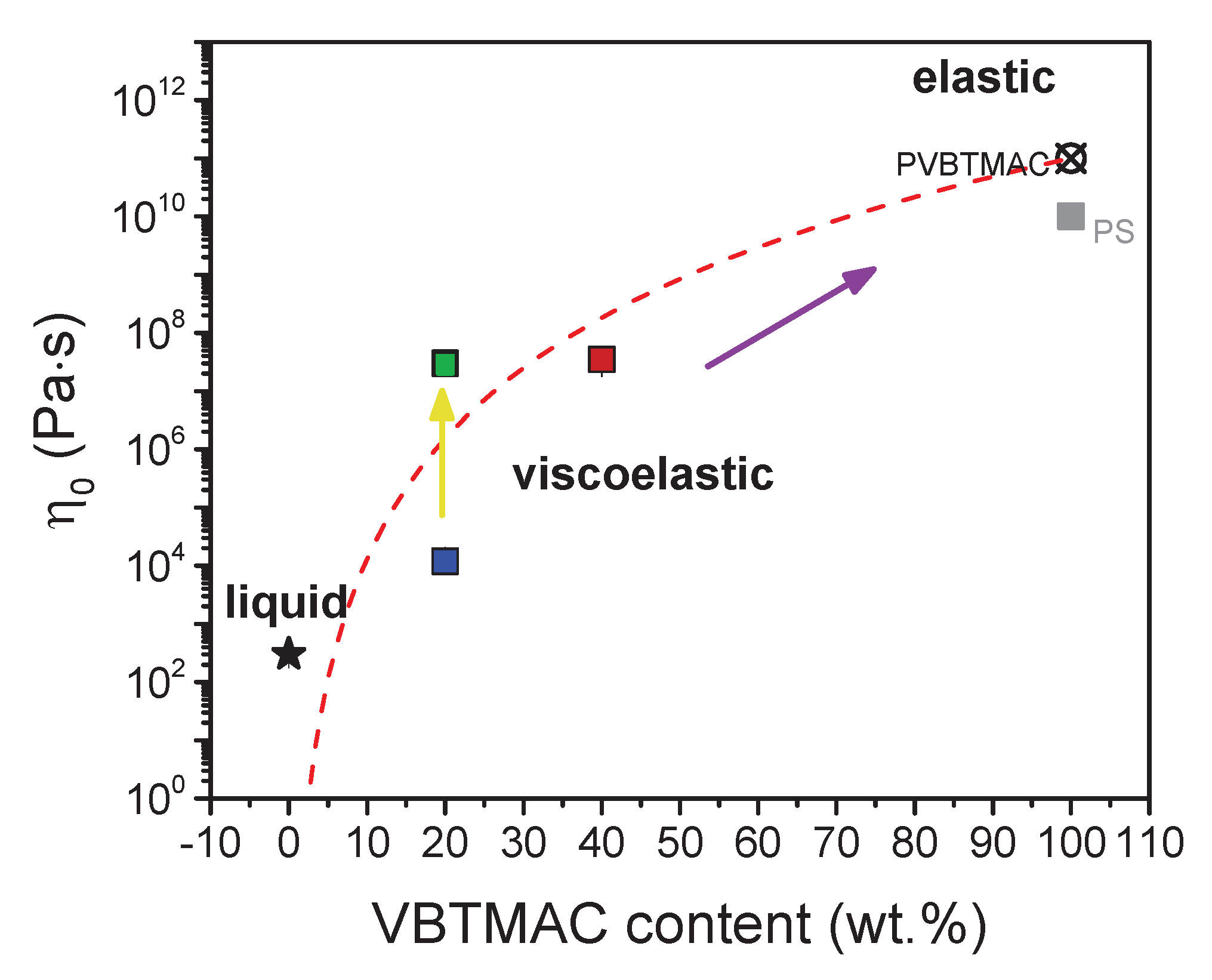

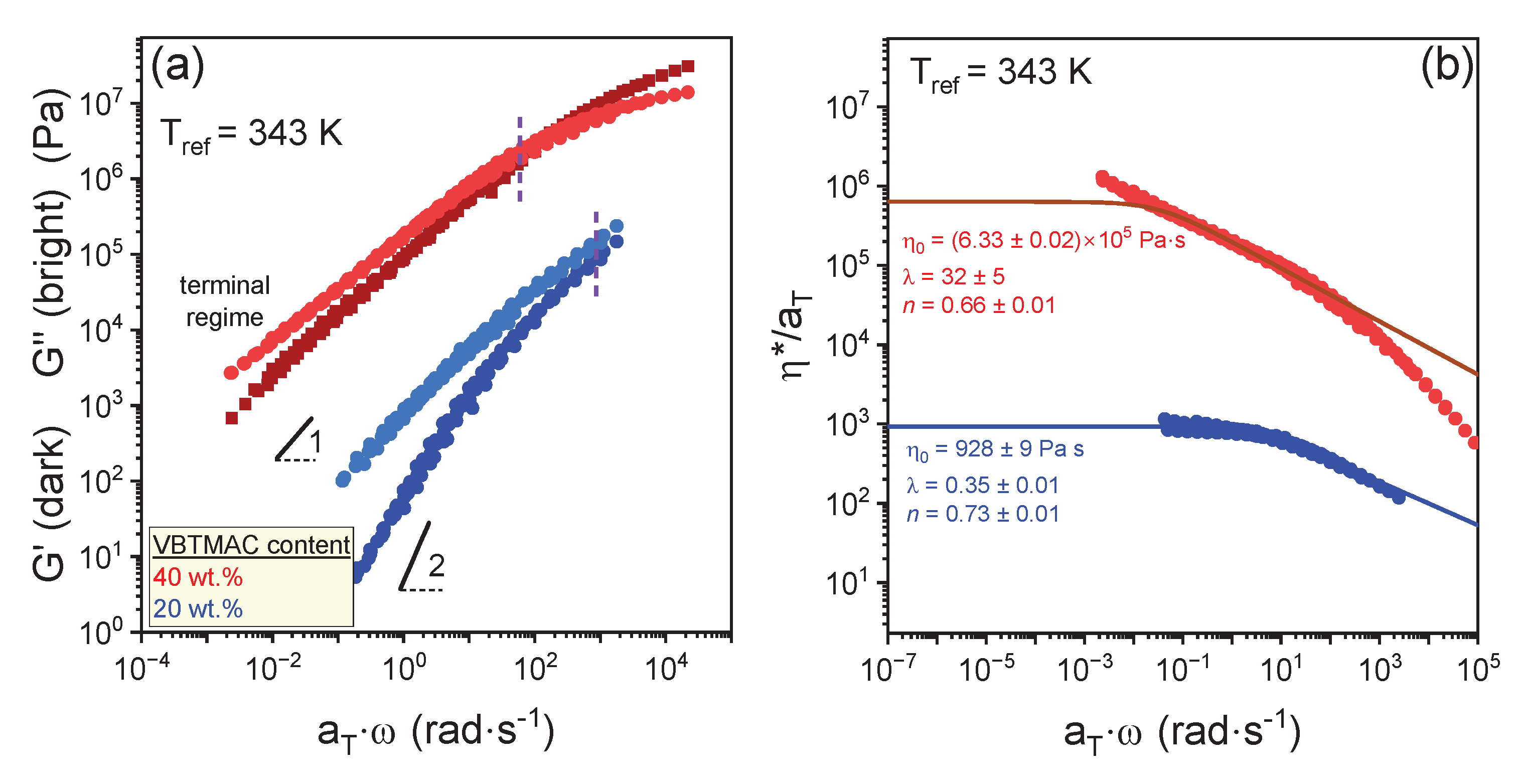

| VBTMAC (wt.%) | η0 (Pa·s) | λ (s) | n | α |

| Carreau-Yasuda (CY) model | ||||

| 20 (sequential) | (3 ± 1) 107 | 580 ± 10 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 2 (fixed) |

| 20 (statistical) | 11970 ± 30 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.59 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.03 |

| 40 (statistical) | (2.68± 0.08) 107 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| 100 | (2 ± 2) 1011 | 2000 ± 1000 | 0.015 ± 0.002 | 0.99 ± 0.2 |

| Modified Cross (MC) model | ||||

| 20 (sequential) | (3 ± 1) 107 | 1800 ± 900 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | - |

| 20 (statistical) | 11970 ± 30 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.61 ± 0.01 | - |

| 40 (statistical) | (3.13 ± 0.08) 107 | 2.65 ± 0.4 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | - |

| 100 | (2.47 ± 0.09) 1011 | 1490 ± 60 | 0.015 ± 0.002 | - |

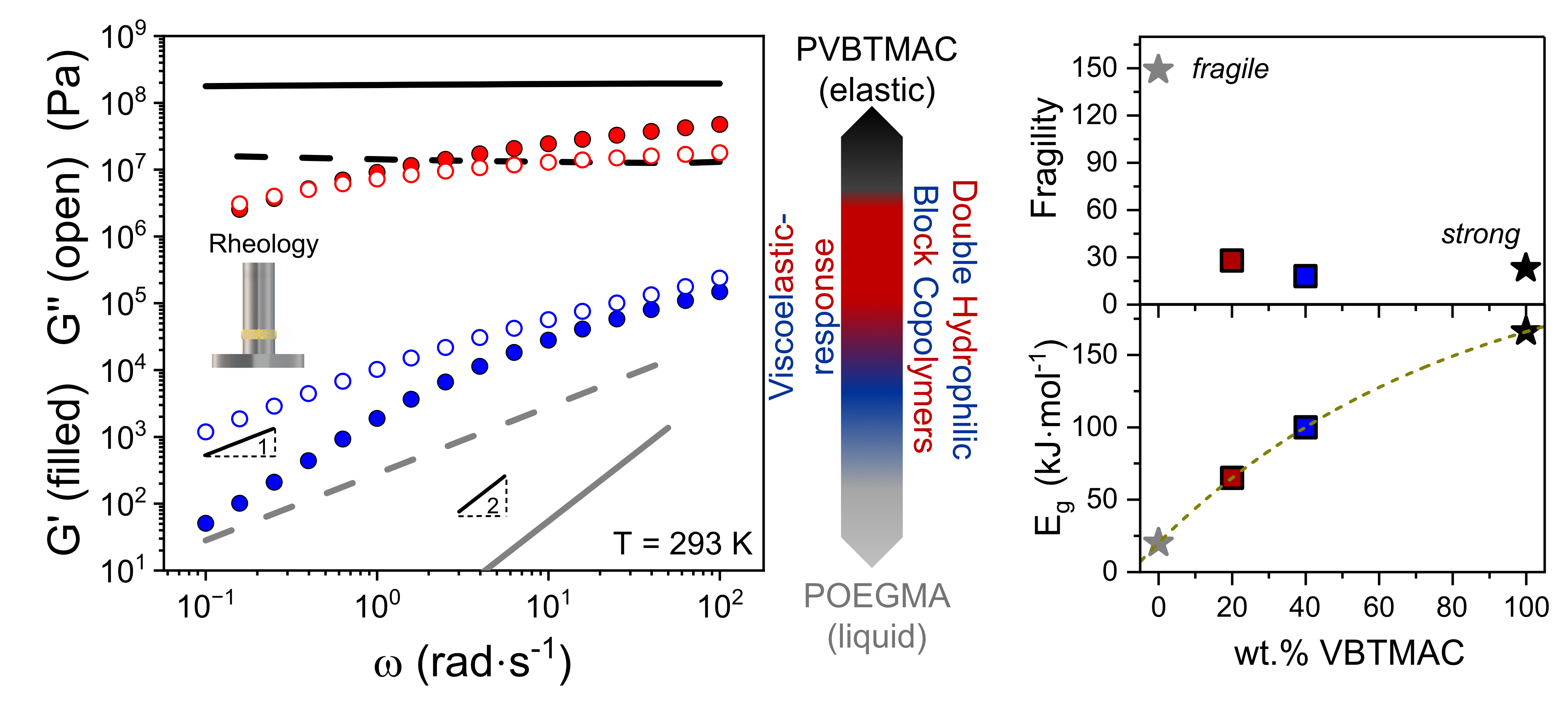

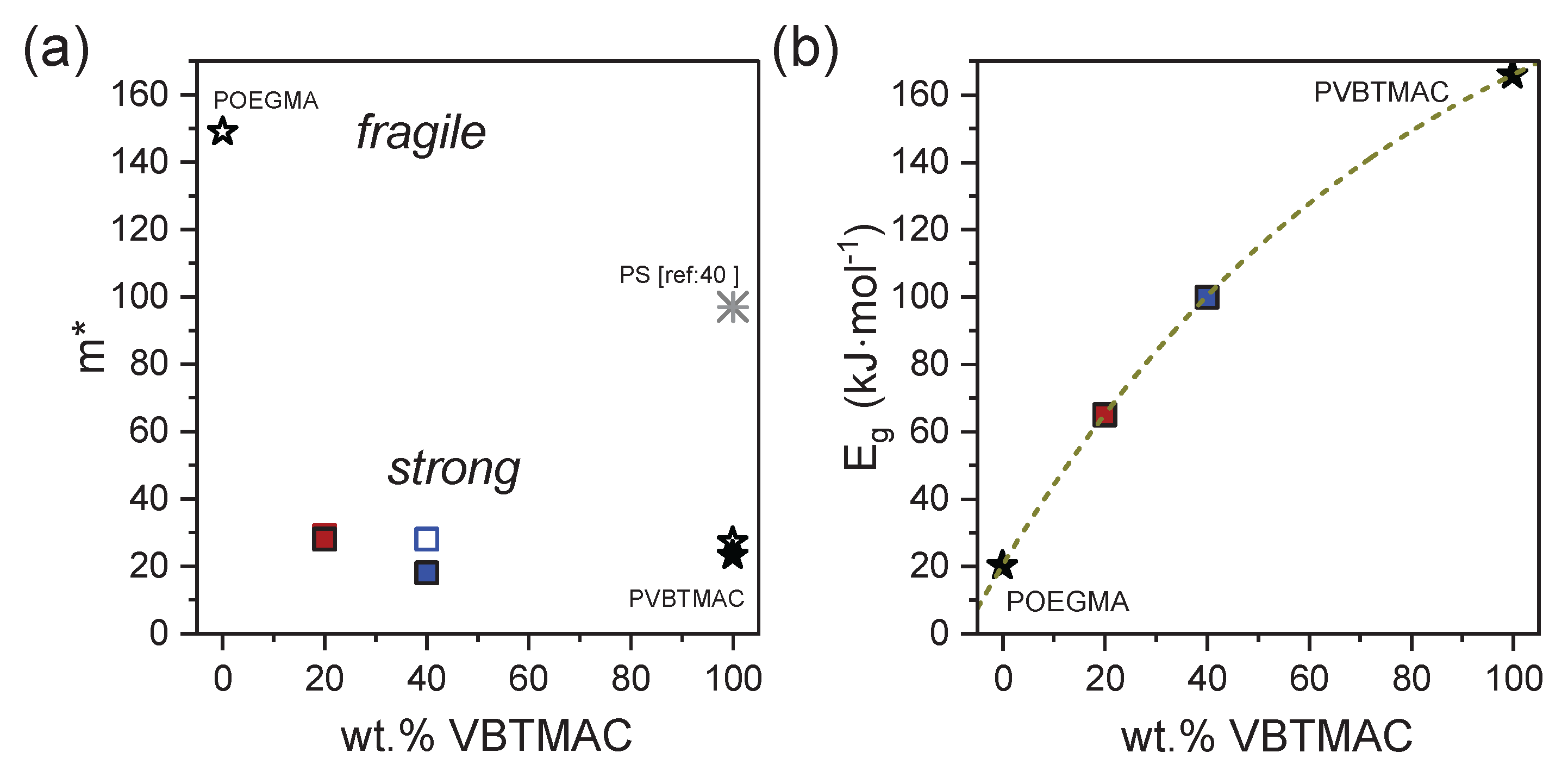

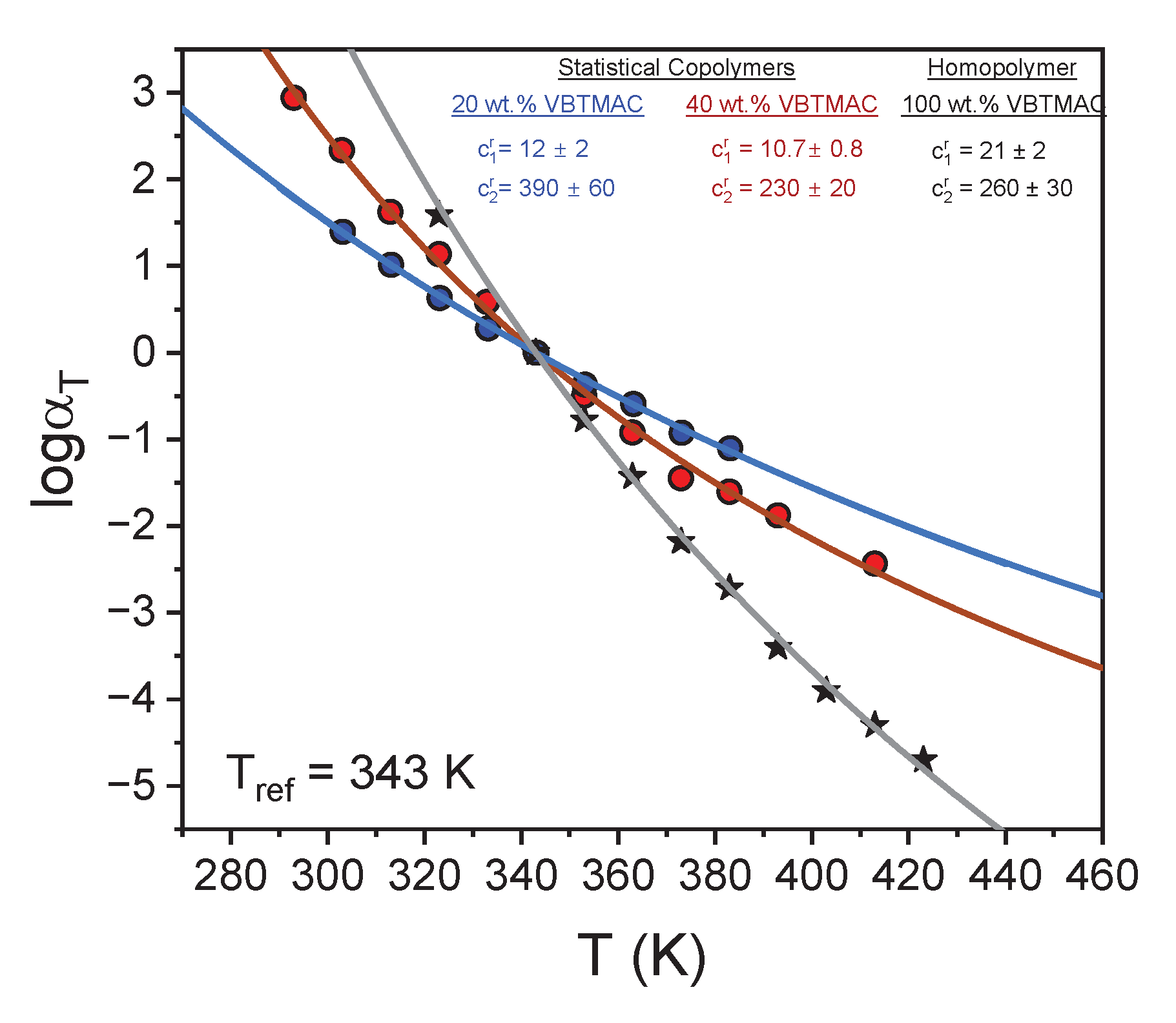

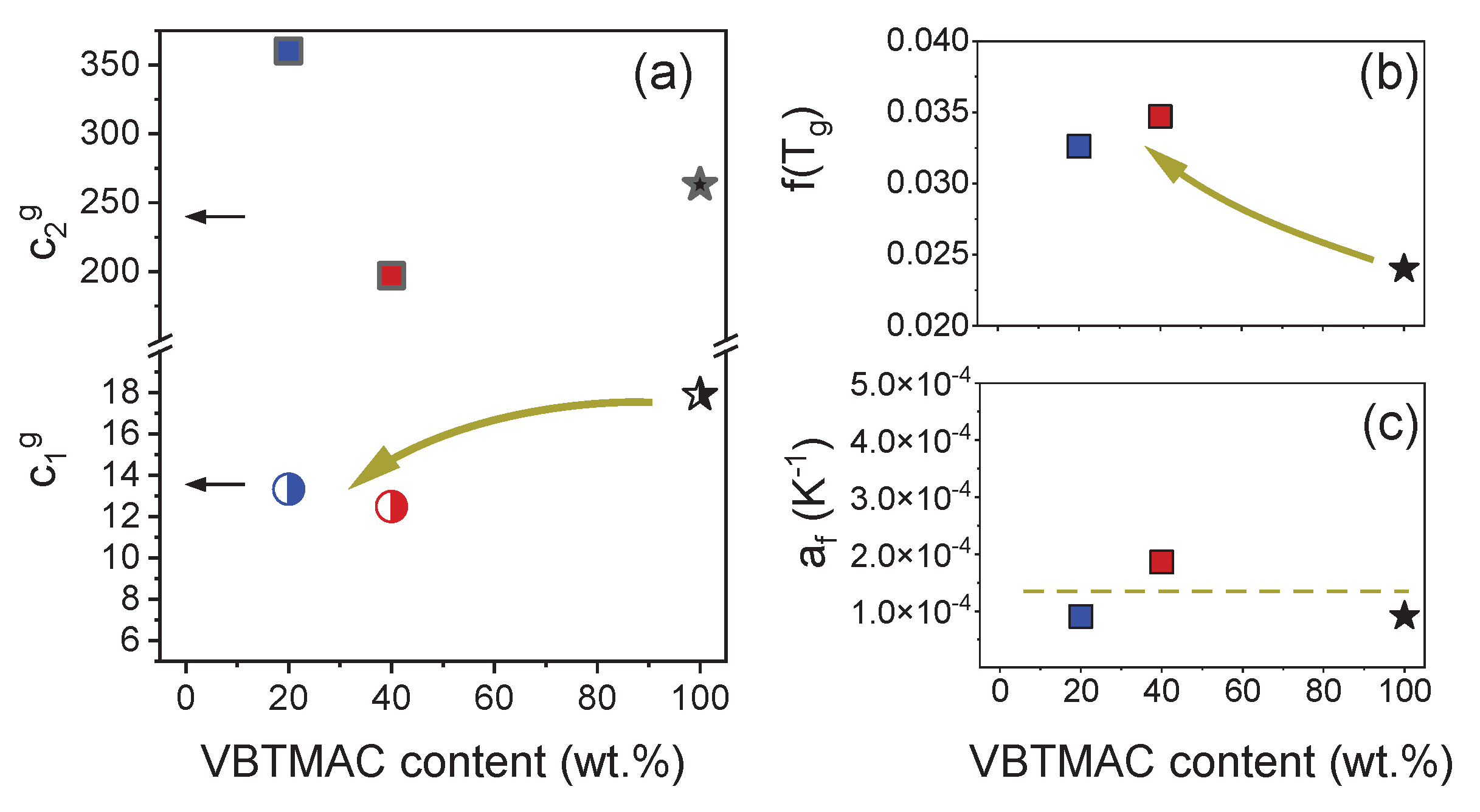

| Sample code | Tg (K)* | c1g | c2g (K) | f(Tg) | αf (K-1) | m* |

Eg (kJ·mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P(OEGMA80-co-VBTMAC20) | 290 | 13.33 | 360 | 0.0326 | 9.05 10-5 | 28 | 65.1 |

| P(OEGMA60-co-VBTMAC40) | 310 | 12.49 | 197 | 0.0347 | 1.51 10-4 | 23 | 99.9 |

| PVBTMAC | 383 | 17.9 | 303 | 0.024 | 9.1 10-5 | 23 | 166 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).