Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

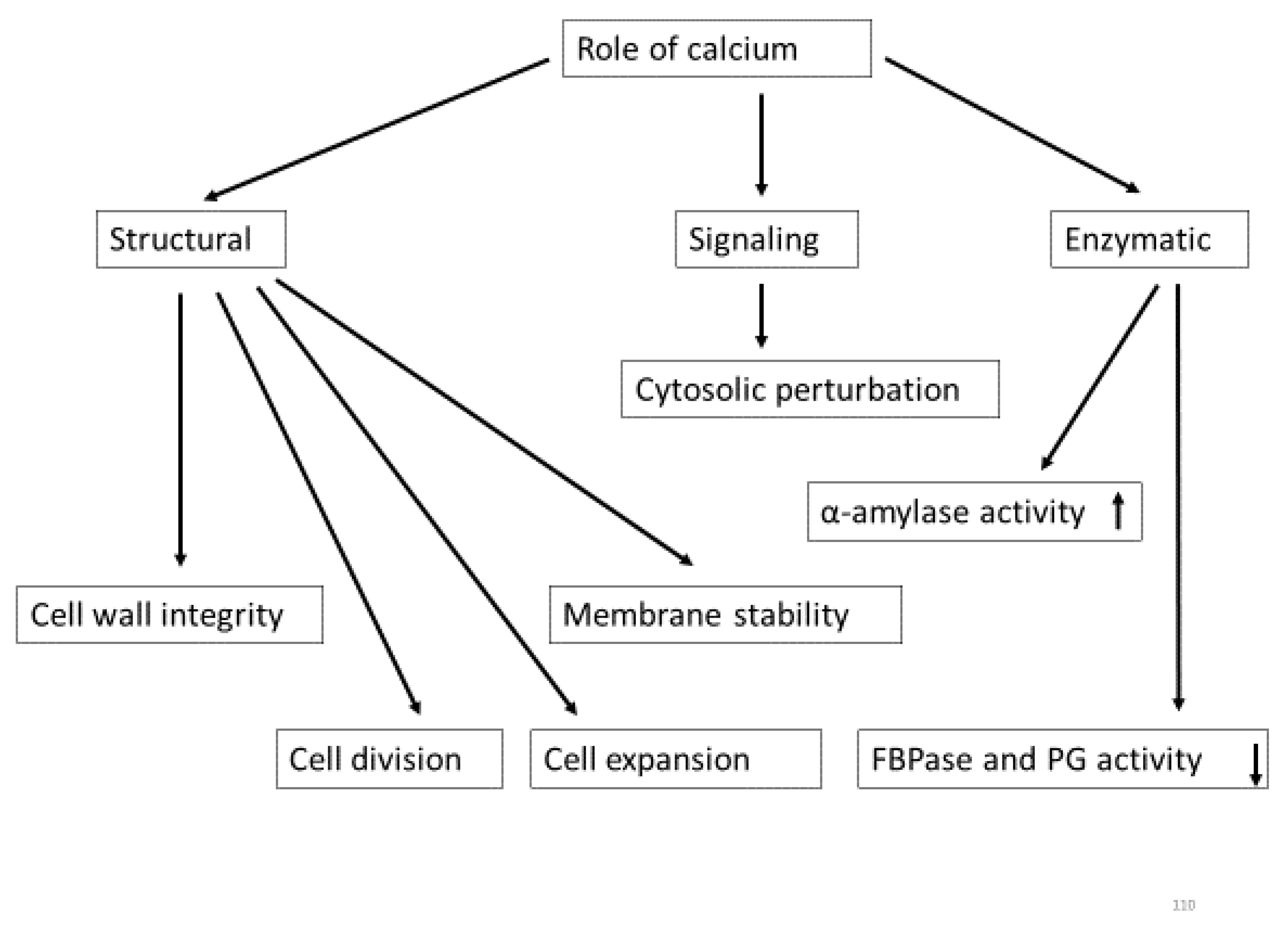

2. Function of Calcium in Plants

2.1. Structural Role of Calcium

2.2. Enzymatic Role of Calcium

2.3. Calcium and Signal Transduction

2.3.1. Calcium Proteins

2.3.2. Calcium Channels

2.3.2. Calcium Efflux Systems

3. Plant Calcium Uptake by the Root System

4. Calcium Uptake Through Foliar Application

5. Calcium Uptake Through the Fruit

6. Calcium Translocations

6.1. Calcium Translocations Within the Plant

6.2. Leaf or Fruit?

6.3. Calcium Translocation Within the Fruit

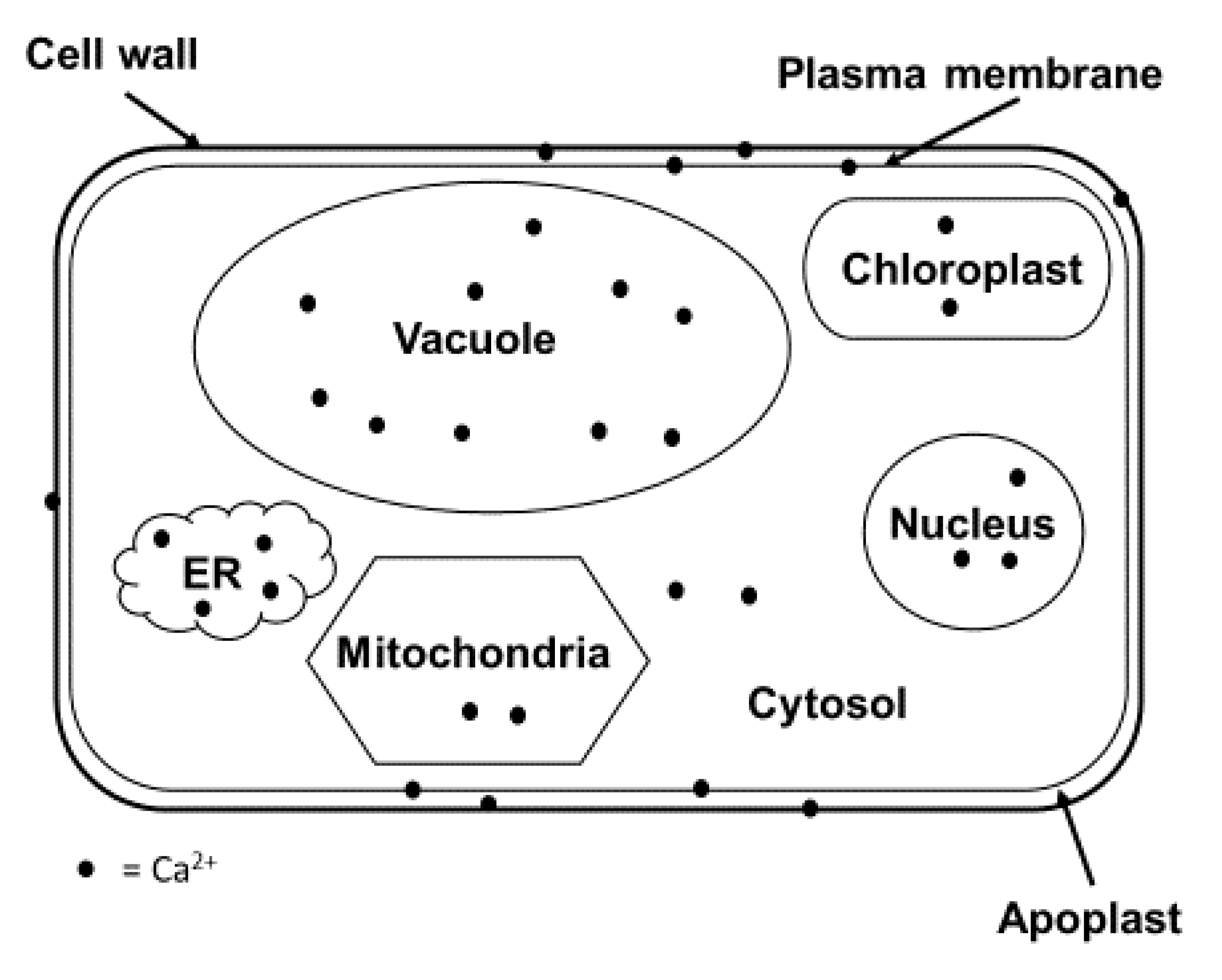

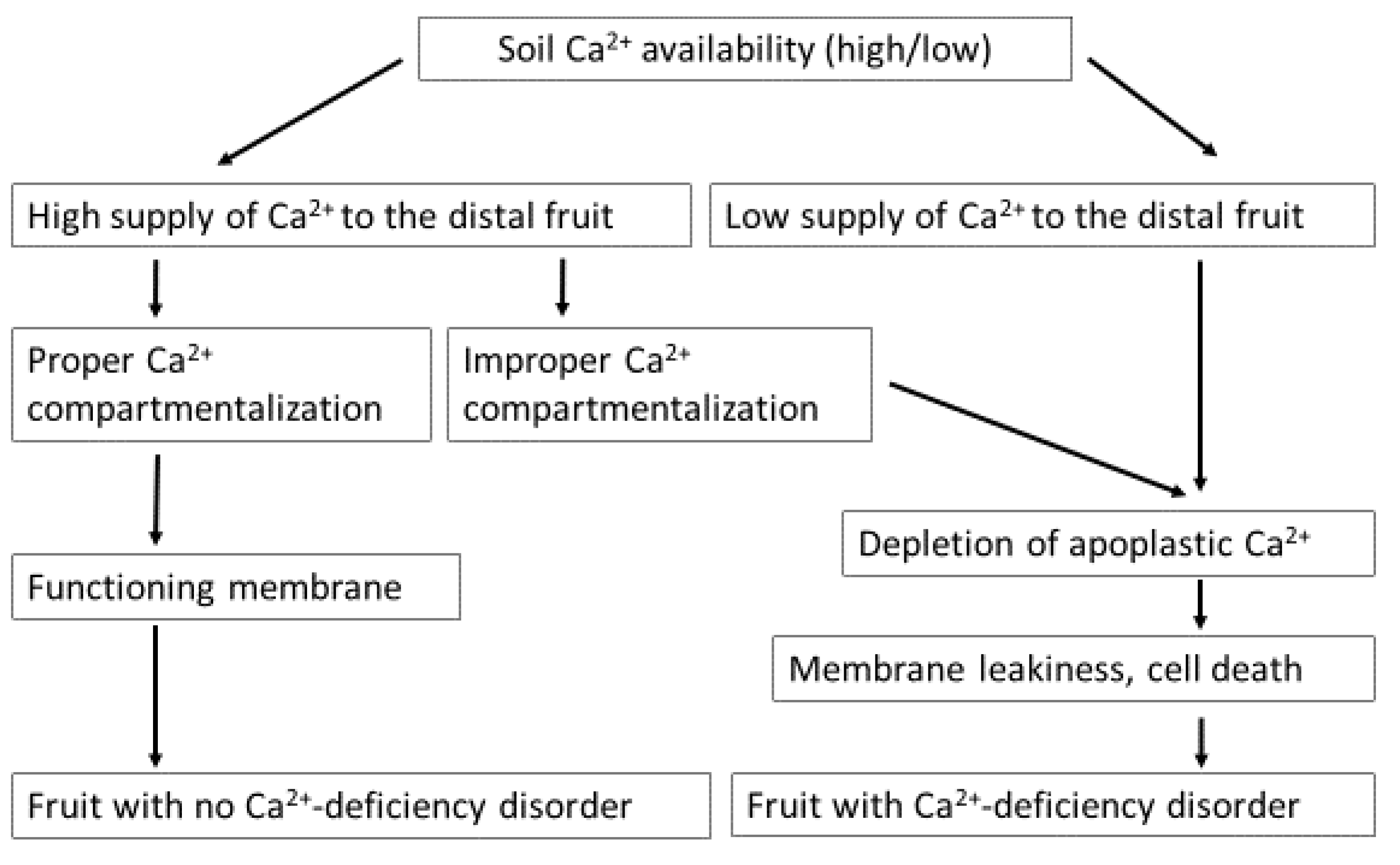

7. Calcium Compartmentalization Within the Cell

8. Calcium Deficiency Disorders

| Deficiency symptoms | Crops | Description | Reference |

| Blossom-end rot | Bell pepper, tomato, watermelon, eggplant, Squash | Blossom-end rot in fruit and vegetables develops dry, brown/black, sunken spots, leading to rotting that may cover most of the fruit. | [20,22,24,172,182,183] |

| Blackheart | Celery | Young leaf tissue collapsed and turned black, usually at the center (heart) of celery. | [126,181] |

| Bitter pit | Apple | Development of brown/black depressed spots on the fruits. | [20,134,158] |

| Empty pod | Peanut | Poor or no development of the seed kernel results in an empty pod/shell of the peanut | [20] |

| Tip burn | Cabbage, Chinese cabbage, other cabbages | The tips of rapidly growing young leaves become necrotic | [23,25,178] |

| Brussels sprouts, lettuce |

Necrosis of the tip of rapidly growing young leaves | [23,179,180] | |

| Chervil | Tip of rapidly growing young leaves become necrotic | [23,177] | |

| Chicory, escarole, onion, fennel, potatoes | Necrosis of tip of rapidly growing young leaves | [23] | |

| Brown heart | Leafy vegetables | Necrosis of tip of young leaves that cover the entire leaf later | [20] |

| Fruit cracking | Tomato, cherry, apple | Splitting of skin or cuticle | [20] |

8.1. Genesis of Blossom-End Rot Development

8.2. Incidence of BER Based on Variety, Season, and Truss

9. Control of BER

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keiser, J. R., & Mullen, R. E. (1993). Calcium and relative humidity effects on soybean seed nutrition and seed quality. Crop Science, 33(6), 1345-1349. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S. B., & Wimmer, R. (1999). Tansley Review No. 104 Calcium physiology and terrestrial ecosystem processes. The New Phytologist, 142(3), 373-417. [CrossRef]

- Zartdinova, R., & Nikitin, A. (2023). Calcium in the life cycle of legume root nodules. Indian Journal of Microbiology, 63(4), 410-420. [CrossRef]

- Hawkesford, Malcolm, Walter Horst, Thomas Kichey, Hans Lambers, Jan Schjoerring, Inge Skrumsager Møller, and Philip White. 2012. 'Chapter 6 - Functions of Macronutrients A2 - Marschner, Petra.' in Marschner's Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (Third Edition) (Academic Press: San Diego).

- Saito, S., & Uozumi, N. (2020). Calcium-regulated phosphorylation systems controlling uptake and balance of plant nutrients. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 44. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. C., Chung, W. S., Yun, D. J., & Cho, M. J. (2009). Calcium and calmodulin-mediated regulation of gene expression in plants. Molecular plant, 2(1), 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Feng, D., Wang, X., Gao, J., Zhang, C., Liu, H., Liu, P., & Sun, X. (2023). Exogenous calcium: Its mechanisms and research advances involved in plant stress tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1143963. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., Liu, J., Liu, T., Zhu, C., Wu, F., Jiang, C., ... & Zheng, H. (2023). Exogenous calcium regulates the growth and development of Pinus massoniana detecting by physiological, proteomic, and calcium-related gene expression analysis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 196, 1122-1136. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., Tian, S. B., Di, Q., Duan, S. H., & Dai, K. (2018). Effects of exogenous calcium on mesophyll cell ultrastructure, gas exchange, and photosystem II in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum Linn.) under drought stress. Photosynthetica, 56(4), 1204-1211. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Pan, B., Wang, Y., Xu, W., & Zhang, S. (2020). Exogenous calcium improved resistance to Botryosphaeria dothidea by increasing autophagy activity and salicylic acid level in pear. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 33(9), 1150-1160. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M. T., Torres-Vidal, P., Calvo, B., Rodriguez, C., Delrio-Lorenzo, A., Rojo-Ruiz, J., ... & Patel, S. (2023). Use of aequorin-based indicators for monitoring Ca2+ in acidic organelles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research, 1870(6), 119481. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, M. K. (2020). Arginine vasotocin and vertebrate reproduction. In The Pineal Gland (pp. 125-163). CRC Press.

- Lecourieux, D., Mazars, C., Pauly, N., Ranjeva, R., & Pugin, A. (2002). Analysis and effects of cytosolic free calcium increases in response to elicitors in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia cells. The Plant Cell, 14(10), 2627-2641. [CrossRef]

- Carafoli, E. (2005). Calcium–a universal carrier of biological signals: delivered on 3 July 2003 at the Special FEBS Meeting in Brussels. The FEBS journal, 272(5), 1073-1089. [CrossRef]

- Marschner, Horst. 1995. '8 - Functions of Mineral Nutrients: Macronutrients.' In, Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (Second Edition) (Academic Press: London).

- Kulik, L. V., Epel, B., Lubitz, W., & Messinger, J. (2007). Electronic structure of the Mn4O x Ca cluster in the S0 and S2 States of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II based on pulse 55Mn-ENDOR and EPR spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 129(44), 13421-13435. [CrossRef]

- McAinsh, M. R., & Hetherington, A. M. (1998). Encoding specificity in Ca2+ signalling systems. Trends in Plant Science, 3(1), 32-36. [CrossRef]

- Simon, E. W. (1978). The symptoms of calcium deficiency in plants. New phytologist, 80(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Barber, S. A. (1995). Soil nutrient bioavailability: a mechanistic approach. John Wiley & Sons.Barickman, T. C., Kopsell, D. A., & Sams, C. E. (2014). Foliar applications of abscisic acid decrease the incidence of blossom-end rot in tomato fruit. Scientia Horticulturae, 179, 356-362. [CrossRef]

- White, P.J., Broadley, M.R., 2003. Calcium in plants. Annals of Botany, 92(4), 487-511. [CrossRef]

- Morard, P., Lacoste, L., & Silvestre, J. (2000). Effects of calcium deficiency on nutrient concentration of xylem sap of excised tomato plants. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 23(8), 1051-1062. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-P´erez, J.C., Hook, J.E., 2017. Plastic-mulched bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plant growth and fruit yield and quality as influenced by irrigation rate and calcium fertilization. HortScience 52, 774–781. [CrossRef]

- Olle, M., & Bender, I. (2009). Causes and control of calcium deficiency disorders in vegetables: A review. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 84(6), 577-584. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. D., & Locascio, S. J. (2004). Blossom-end rot: a calcium deficiency. Journal of Plant nutrition, 27(1), 123-139. [CrossRef]

- Aloni, B., Pashkar, T., Libel, R., 1986. The possible involvement of gibberellins and calcium in tipburn of Chinese cabbage: study of intact plants and detached leaves. Plant Growth Regulation, 4, 3-11. [CrossRef]

- Geraldson, C. M. (1956). The use of calcium for control of blossom-end rot of Tomatoes. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society, 68: 197-202.

- Adams, P., & El-Gizawy, A. M. (1988). Effect of calcium stress on the calcium status of tomatoes grown in NFT. Acta Horticulturae, 222: 15-22.

- Banuelos, G. S., Offermann, G. P., & Seim, E. C. (1985). High relative humidity promotes blossom-end rot on growing tomato fruit. HortScience, 20(5), 894-895.

- Barke, R. E. (1968). Absorption and translocation of calcium foliar sprays in relation to the incidence of blossom-end rot in tomatoes. Queensland Journal of Agricultural and Animal Sciences, 25(4), 179-197.

- Cho, I. H., Lee, E. H., Kim, T. Y., Woo, Y. H., & Kwon, Y. S. (1998). Effects of high humidity on occurrence of tomato blossom-end rot. Journal of the Korean Society for Horticultural Science (Korea Republic), 39(3). 47-249.

- El-Gizawy, A. M., & Adams, P. (1985, June). Effect of temporary calcium stress on the calcium status of tomato fruit and leaves. In Symposium on Nutrition, Growing Techniques and Plant Substrates 178: 37-44. 10.17660/ActaHortic.1986.178.3.

- Gutteridge, C. G., & Bradfield, E. G. (1983). Root pressure stops blossom-end rot. Grower 100(6): 25-26.

- Saure, M. C. (2001). Blossom-end rot of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.)—a calcium-or a stress-related disorder? Scientia Horticulturae, 90(3-4), 193-208. [CrossRef]

- Spurr, A. R. (1959). Anatomical aspects of blossom-end rot in the tomato with special reference to calcium nutrition. Hilgardia 28 (12): 269-295.

- Wada, T., Ikeda, H., Ikeda, M., & Furukawa, H. (1996). Effects of foliar application of calcium solutions on the incidence of blossom-end rot of tomato fruit. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science, 65(3), 553-558. [CrossRef]

- Westerhout, J. (1962). Relation of fruit development to the incidence of blossom-end rot of tomatoes. Netherlands Journal of Agricultural Science, 10(3), 223-234. [CrossRef]

- Wui, M., & Takano, T. (1995). Effect of Temperature and Concentration of Nutrient Solution during the Stage of the Fruit Development on the Incidence of Blossom-End Rot in Fruits of Tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum L. Environment Control in Biology, 33(1), 7-14.

- De Freitas, S. T., McElrone, A. J., Shackel, K. A., & Mitcham, E. J. (2014). Calcium partitioning and allocation and blossom-end rot development in tomato plants in response to whole-plant and fruit-specific abscisic acid treatments. Journal of Experimental Botany, 65(1), 235-247. [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, M., Elkhawaga, F. A., Suliman, A. A., Puchkov, M., Kuranova, K. N., Mahmoud, M. H., & Abdelkader, M. F. (2024). Understanding the Regular Biological Mechanism of Susceptibility of Tomato Plants to Low Incidences of Blossom-End Rot. Horticulturae, 10(6), 648. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M. Y., Díaz-Pérez, J. C., Doyle, J. W., Berenguer, E. I., van der Knaap, E., & Nambeesan, S. U. (2017, September). The Effect of Calcium Application and Irrigation on Development of Blossom-end Rot in Tomato. In 2017 ASHS Annual Conference. ASHS.

- De Freitas, S. T., Padda, M., Wu, Q., Park, S., & Mitcham, E. J. (2011a). Dynamic alternations in cellular and molecular components during blossom-end rot development in tomatoes expressing sCAX1, a constitutively active Ca2+/H+ antiporter from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology, 156(2), 844-855. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Wu, X., Zorrilla, C., Vega, S. E., & Palta, J. P. (2020). Fractionating of calcium in tuber and leaf tissues explains the calcium deficiency symptoms in potato plant overexpressing CAX1. Front. Plant Sci., 10, 1793. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Kim, C. K., Pike, L. M., Smith, R. H., & Hirschi, K. D. (2004). Increased calcium in carrots by expression of an Arabidopsis H+/Ca 2+ transporter. Molecular Breeding, 14, 275-282. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q., Shigaki, T., Han, J. S., Kim, C. K., Hirschi, K. D., & Park, S. (2012). Ectopic expression of a maize calreticulin mitigates calcium deficiency-like disorders in sCAX1-expressing tobacco and tomato. Plant Mol. Biol., 80, 609-619. [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla, C., Schabow, J. E., Chernov, V., & Palta, J. P. (2019). CAX1 vacuolar antiporter overexpression in potato results in calcium deficiency in leaves and tubers by sequestering calcium as calcium oxalate. Crop Science, 59(1), 176-189. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, S. E., Tsou, P. L., & Robertson, D. (2002). Expression of the high capacity calcium-binding domain of calreticulin increases bioavailable calcium stores in plants. Transgenic Research, 11, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kuronuma, T., & Watanabe, H. (2021). Identification of the Causative Genes of Calcium Deficiency Disorders in Horticulture Crops: A Systematic Review. Agric, 11, 906. [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, K. D. (2004). The calcium conundrum. Both versatile nutrient and specific signal. Plant Physiology, 136(1), 2438-2442. [CrossRef]

- Weng, X., Li, H., Ren, C., Zhou, Y., Zhu, W., Zhang, S., & Liu, L. (2022). Calcium regulates growth and nutrient absorption in poplar seedlings. Front. Plant Sci., 13, 887098. [CrossRef]

- Kitano, M., Araki, T., Yoshida, S., & Eguchi, H. (1999). Dependence of calcium uptake on water absorption and respiration in roots of tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Biotronics: Environment Control and Environmental Biology || 28 |, p121-130. http://133.5.207.201/index.html.

- Hewitt, E. J. (1963). The essential nutrient elements: Requirements and interactions. Plant Physiology, 137-360.

- White, P. J. (2001). The pathways of calcium movement to the xylem. Journal of Experimental Botany, 52(358), 891-899. [CrossRef]

- Ho, L. C., & White, P. J. (2005). A cellular hypothesis for the induction of blossom-end rot in tomato fruit. Annals of Botany, 95(4), 571-581. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, E. (1972). Mineral Nutrition of Plants: Principles and Perspectives. (New York: John Wiley & Sons).

- Fuller, G. M., Ellison, J. J., McGill, M., Sordahl, L. A., & Brinkley, B. R. (1975). Studies on the inhibitory role of calcium in the regulation of microtubule assembly in vitro and in vivo. Microtubules and microtubule inhibitors, 379-390.

- Taiz, L, and E Zeiger. 2011. 'Plant Physiology Online Fifth Edition [WWW Document]', URL http://5e. plantphys. net.

- Wehr, J. B., Menzies, N. W., & Blamey, F. P. C. (2004). Inhibition of cell-wall autolysis and pectin degradation by cations. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 42(6), 485-492. [CrossRef]

- Ralet, M. C., Dronnet, V., Buchholt, H. C., & Thibault, J. F. (2001). Enzymatically and chemically de-esterified lime pectins: characterisation, polyelectrolyte behaviour and calcium binding properties. Carbohydrate Research, 336(2), 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Goulao, L. F., Santos, J., de Sousa, I., & Oliveira, C. M. (2007). Patterns of enzymatic activity of cell wall-modifying enzymes during growth and ripening of apples. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 43(3), 307-318. [CrossRef]

- Massiot, P., Baron, A., & Drilleau, J. F. (1994). Characterisation and enzymatic hydrolysis of cell-wall polysaccharides from different tissue zones of apple. Carbohydrate Polymers, 25(3), 145-154. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A., Frolich, E., & Lunt, O. R. (1966). Calcium requirements of higher plants. Nature, 209(5023), 634-634. [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, P. A., & Epstein, E. (1971). Calcium and salt toleration by bean plants. Physiologia Plantarum, 25(2), 213-218. [CrossRef]

- Asher, C. J., & Edwards, D. G. (1983). Modern solution culture techniques. In Inorganic plant nutrition (pp. 94-119). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Cramer, G. R. (2002). Sodium-calcium interactions under salinity stress. In Salinity: Environment-plants-molecules (pp. 205-227). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Horst, W. J., Wang, Y., & Eticha, D. (2010). The role of the root apoplast in aluminium-induced inhibition of root elongation and in aluminium resistance of plants: a review. Annals of Botany, 106(1), 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Kirkby, E. A., & Pilbeam, D. J. (1984). Calcium as a plant nutrient. Plant, Cell & Environment, 7(6), 397-405. [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, A., & Hooley, R. (2000). Gibberellin and abscisic acid signalling in aleurone. Trends in Plant Science, 5(3), 102-110. [CrossRef]

- Bush, D. S., Cornejo, M. J., Huang, C. N., & Jones, R. L. (1986). Ca2+-stimulated secretion of α-amylase during development in barley aleurone protoplasts. Plant Physiology, 82(2), 566-574. [CrossRef]

- Luan, S., & Wang, C. (2021). Calcium signaling mechanisms across kingdoms. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 37(1), 311-340. [CrossRef]

- Naz, M., Afzal, M. R., Raza, M. A., Pandey, S., Qi, S., Dai, Z., & Du, D. (2024). Calcium (Ca2+) signaling in plants: A plant stress perspective. South African Journal of Botany, 169, 464-485. [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y., Fu, W., Chen, J., Takano, T., & Liu, S. (2021). Description of AtCAX4 in response to abiotic stress in Arabidopsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(2), 856. [CrossRef]

- Pirayesh, N., Giridhar, M., Khedher, A. B., Vothknecht, U. C., & Chigri, F. (2021). Organellar calcium signaling in plants: An update. biochimica et biophysica Acta (bbA)-molecular Cell Research, 1868(4), 118948. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A. K., Shankar, A., Nalini Chandran, A. K., Sharma, M., Jung, K. H., Suprasanna, P., & Pandey, G. K. (2020). Emerging concepts of potassium homeostasis in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 71(2), 608-619. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., Ma, C., Li, M., Zhangzhong, L., Song, P., & Li, Y. (2023). Interaction and adaptation of phosphorus fertilizer and calcium ion in drip irrigation systems: the perspective of emitter clogging. Agricultural Water Management, 282, 108269. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S., Negi, N. P., Narwal, P., Kumari, P., Kisku, A. V., Gahlot, P., ... & Kumar, D. (2022). Calcium signaling in coordinating plant development, circadian oscillations and environmental stress responses in plants. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 201, 104935. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S., Bheri, M., & Pandey, G. K. (2021). Delineating calcium signaling machinery in plants: tapping the potential through functional genomics. Current Genomics, 22(6), 404-439. [CrossRef]

- Fedrizzi, L., Lim, D., & Carafoli, E. (2008). Calcium and signal transduction. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 36(3), 175-180. [CrossRef]

- Lecourieux, D., Ranjeva, R., & Pugin, A. (2006). Calcium in plant defence-signalling pathways. New Phytologist, 171(2), 249-269. [CrossRef]

- Paliyath, G., & Thompson, J. E. (1987). Calcium-and calmodulin-regulated breakdown of phospholipid by microsomal membranes from bean cotyledons. Plant Physiology, 83(1), 63-68. [CrossRef]

- Rudd, J. J., & Franklin-Tong, V. E. (1999). Calcium signaling in plants. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences CMLS, 55, 214-232. [CrossRef]

- McAinsh, M. R., & Pittman, J. K. (2009). Shaping the calcium signature. New Phytologist, 181(2), 275-294. [CrossRef]

- Putney Jr, J. W. (1998). Calcium signaling: Up, down, up, down.... What's the point? Science, 279(5348), 191-192. [CrossRef]

- Luan, S., Kudla, J., Rodriguez-Concepcion, M., Yalovsky, S., & Gruissem, W. (2002). Calmodulins and calcineurin B–like proteins: Calcium sensors for specific signal response coupling in plants. The Plant Cell, 14(suppl_1), S389-S400. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D., Pelloux, J., Brownlee, C., & Harper, J. F. (2002). Calcium at the crossroads of signaling. The Plant Cell, 14(suppl_1), S401-S417. [CrossRef]

- Bouché, N., Scharlat, A., Snedden, W., Bouchez, D., & Fromm, H. (2002). A novel family of calmodulin-binding transcription activators in multicellular organisms. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277(24), 21851-21861. [CrossRef]

- Doherty, C. J., Van Buskirk, H. A., Myers, S. J., & Thomashow, M. F. (2009). Roles for Arabidopsis CAMTA transcription factors in cold-regulated gene expression and freezing tolerance. The Plant Cell, 21(3), 972-984. [CrossRef]

- Laohavisit, A., & Davies, J. M. (2009). Multifunctional annexins. Plant Science, 177(6), 532-539. [CrossRef]

- Miedema, H., Bothwell, J. H., Brownlee, C., & Davies, J. M. (2001). Calcium uptake by plant cells–channels and pumps acting in concert. Trends in Plant Science, 6(11), 514-519. [CrossRef]

- White, P. J. (2000). Calcium channels in higher plants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 1465(1-2), 171-189. [CrossRef]

- White, P. J., Bowen, H. C., Demidchik, V., Nichols, C., & Davies, J. M. (2002). Genes for calcium-permeable channels in the plasma membrane of plant root cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 1564(2), 299-309. [CrossRef]

- White, P. J. (2009). Depolarization-activated calcium channels shape the calcium signatures induced by low-temperature stress. New Phytologist, 6-8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40302000.

- Miedema, H., Demidchik, V., Véry, A. A., Bothwell, J. H., Brownlee, C., & Davies, J. M. (2008). Two voltage-dependent calcium channels co-exist in the apical plasma membrane of Arabidopsis thaliana root hairs. New Phytologist, 179(2), 378-385. [CrossRef]

- Amtmann, A., & Blatt, M. R. (2009). Regulation of macronutrient transport. New Phytologist, 181(1). 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02666.x.

- Kim, M. D., Kim, Y. H., Kwon, S. Y., Yun, D. J., Kwak, S. S., & Lee, H. S. (2010). Enhanced tolerance to methyl viologen-induced oxidative stress and high temperature in transgenic potato plants overexpressing the CuZnSOD, APX and NDPK2 genes. Physiologia Plantarum, 140(2), 153-162. [CrossRef]

- Moran, N. (2007). Osmoregulation of leaf motor cells. FEBS letters, 581(12), 2337-2347. [CrossRef]

- Harper, J. F. (2001). Dissecting calcium oscillators in plant cells. Trends in Plant Science, 6(9), 395-397. [CrossRef]

- Klüsener, B., Boheim, G., Liss, H., Engelberth, J., & Weiler, E. W. (1995). Gadolinium-sensitive, voltage-dependent calcium release channels in the endoplasmic reticulum of a higher plant mechanoreceptor organ. The EMBO Journal, 14(12), 2708-2714. [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, K. D. (2001). Vacuolar H+/Ca2+ transport: who's directing the traffic?. Trends in plant science, 6(3), 100-104. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Liang, F., Hong, B., Young, J. C., Sussman, M. R., Harper, J. F., & Sze, H. (2002). An endoplasmic reticulum-bound Ca2+/Mn2+ pump, ECA1, supports plant growth and confers tolerance to Mn2+ stress. Plant Physiology, 130(1), 128-137. [CrossRef]

- Blatt, M. R. (2000). Cellular signaling and volume control in stomatal movements in plants. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 16(1), 221-241. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S. M., Swanson, S. J., & Gilroy, S. (2002). From common signalling components to cell-specific responses: insights from the cereal aleurone. Physiologia Plantarum, 115(3), 342-351. [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. E., & Williams, L. E. (1998). P-type calcium ATPases in higher plants–biochemical, molecular and functional properties. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Biomembranes, 1376(1), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Berkelman, T., Franklin, A. E., & Hoffman, N. E. (1993). Characterization of a gene encoding a Ca (2+)-ATPase-like protein in the plastid envelope. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 90(21), 10066-10070. [CrossRef]

- Harper, J. F., Hong, B., Hwang, I., Guo, H. Q., Stoddard, R., Huang, J. F., ... & Sze, H. (1998). A novel calmodulin-regulated Ca2+-ATPase (ACA2) from Arabidopsis with an N-terminal autoinhibitory domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273(2), 1099-1106. [CrossRef]

- Bonza, M. C., Morandini, P., Luoni, L., Geisler, M., Palmgren, M. G., & De Michelis, M. I. (2000). At-ACA8 encodes a plasma membrane-localized calcium-ATPase of Arabidopsis with a calmodulin-binding domain at the N terminus. Plant Physiology, 123(4), 1495-1506. [CrossRef]

- George, L., Romanowsky, S. M., Harper, J. F., & Sharrock, R. A. (2008). The ACA10 Ca2+-ATPase regulates adult vegetative development and inflorescence architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology, 146(2), 716. [CrossRef]

- Schiøtt, M., Romanowsky, S. M., Bækgaard, L., Jakobsen, M. K., Palmgren, M. G., & Harper, J. F. (2004). A plant plasma membrane Ca2+ pump is required for normal pollen tube growth and fertilization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(25), 9502-9507. [CrossRef]

- Geisler, M., Frangne, N., Gomes, E., Martinoia, E., & Palmgren, M. G. (2000). The ACA4 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a vacuolar membrane calcium pump that improves salt tolerance in yeast. Plant Physiology, 124(4), 1814-1827. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Kim, B. G., Cheong, Y. H., Pandey, G. K., & Luan, S. (2006). A Ca2+ signaling pathway regulates a K+ channel for low-K response in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(33), 12625-12630. [CrossRef]

- Liang, F., Cunningham, K. W., Harper, J. F., & Sze, H. (1997). ECA1 complements yeast mutants defective in Ca2+ pumps and encodes an endoplasmic reticulum-type Ca2+-ATPase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94(16), 8579-8584. [CrossRef]

- Mills, R. F., Doherty, M. L., López-Marqués, R. L., Weimar, T., Dupree, P., Palmgren, M. G., ... & Williams, L. E. (2008). ECA3, a Golgi-localized P2A-type ATPase, plays a crucial role in manganese nutrition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology, 146(1), 116-128. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Chanroj, S., Wu, Z., Romanowsky, S. M., Harper, J. F., & Sze, H. (2008). A distinct endosomal Ca2+/Mn2+ pump affects root growth through the secretory process. Plant Physiology, 147(4), 1675-1689. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N. H., Pittman, J. K., Shigaki, T., Lachmansingh, J., LeClere, S., Lahner, B., ... & Hirschi, K. D. (2005). Functional association of Arabidopsis CAX1 and CAX3 is required for normal growth and ion homeostasis. Plant Physiology, 138(4), 2048-2060. [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, K. D., Korenkov, V. D., Wilganowski, N. L., & Wagner, G. J. (2000). Expression of Arabidopsis CAX2 in tobacco. Altered metal accumulation and increased manganese tolerance. Plant Physiology, 124(1), 125-134. [CrossRef]

- Luo, G. Z., Wang, H. W., Huang, J., Tian, A. G., Wang, Y. J., Zhang, J. S., & Chen, S. Y. (2005). A putative plasma membrane cation/proton antiporter from soybean confers salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Molecular Biology, 59, 809-820. [CrossRef]

- Hepler, P. K., & Winship, L. J. (2010). Calcium at the cell wall-cytoplast interface. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 52(2), 147-160. [CrossRef]

- De Kreij, C. (1996). Interactive effects of air humidity, calcium and phosphate on blossom-end rot, leaf deformation, production and nutrient contents of tomato. Journal of plant nutrition, 19(2), 361-377. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, D. T. (1993). Roots and the delivery of solutes to the xylem. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 341(1295), 5-17. [CrossRef]

- Moore, C. A., Bowen, H. C., Scrase-Field, S., Knight, M. R., & White, P. J. (2002). The deposition of suberin lamellae determines the magnitude of cytosolic Ca2+ elevations in root endodermal cells subjected to cooling. The Plant Journal, 30(4), 457-465. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Waterland, N. L. (2021). Evaluation of calcium application methods on delaying plant wilting under water deficit in bedding plants. Agronomy, 11(7), 1383. [CrossRef]

- Santos, E., Montanha, G. S., Agostinho, L. F., Polezi, S., Marques, J. P. R., & de Carvalho, H. W. P. (2023). Foliar calcium absorption by tomato plants: Comparing the effects of calcium sources and adjuvant usage. Plants, 12(14), 2587. [CrossRef]

- Haleema, B., Shah, S. T., Basit, A., Hikal, W. M., Arif, M., Khan, W., ... & Fhatuwani, M. (2024). Comparative Effects of Calcium, Boron, and Zinc Inhibiting Physiological Disorders, Improving Yield and Quality of Solanum lycopersicum. Biology, 13(10), 766. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Ma, J., Gao, X., Tie, J., Wu, Y., Tang, Z., ... & Yu, J. (2022). Exogenous brassinosteroids alleviate calcium deficiency-induced tip-burn by maintaining cell wall structural stability and higher photosynthesis in mini Chinese Cabbage. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 999051. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Ma, J., Zhang, W., Gao, X., Wang, X., Chen, W., ... & Hu, L. (2025). Quality Response of Two Mini Chinese Cabbage Cultivars to Different Calcium Levels. Foods, 14(5), 872. [CrossRef]

- Geraldson, C.M., 1952. Studies on control of blackheart of celery. In Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society, 65, 171-172.

- Vergara, C., Araujo, K. E. C., Santos, A. P., de Oliveira, F. F., de Souza Silva, G., de Oliveira Miranda, N., ... & de Medeiros, J. F. (2024). Use of crushed eggshell to control tomato blossom-end rot. Research, Society and Development, 13(5), e2213545667-e2213545667. [CrossRef]

- Geraldson, C. M. (1954). The control of blackheart of celery. In Proceedings of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 353-58.

- Kleemann, M. (2000). Effects of salinity, nutrients and spraying with cacl2 solution on the development of calcium deficiency in chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium (L.) Hoffm.) and curled parsley (Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) nym. Convar. Crispum). In Integrated View of Fruit and Vegetable Quality (pp. 41-53). CRC Press.

- Schmitz-Eiberger, M., Haefs, R., & Noga, G. (2002). Calcium deficiency-influence on the antioxidative defense system in tomato plants. Journal of Plant Physiology, 159(7), 733-742. [CrossRef]

- Parađiković, N., Lončarić, Z., Bertić, B., & Vukadinović, V. (2004). Influence of Ca-foliar application on yield and quality of sweet pepper in glasshouse conditions. Poljoprivreda, 10(2), 24-27. https://hrcak.srce.hr/22919.

- Raven, J. A. (1977). H+ and Ca2+ in phloem and symplast: relation of relative immobility of the ions to the cytoplasmic nature of the transport paths. New Phytologist, 79(3), 465-480. [CrossRef]

- Kohl, W. (1966). Die calciumverteilung in apfeln und ihre veranderung wahrend des wachstums. Die Gartenbauwissenschaft, 31: 513-47.

- Perring, M. A., & Jackson, C. H. (1975). The mineral composition of apples. Calcium concentration and bitter pit in relation to mean mass per apple. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 26(10), 1493-1502. [CrossRef]

- Bangerth, F. (1979). Calcium-related physiological disorders of plants. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 17(1), 97-122.

- Chamel, A. R. (1989). Permeability characteristics of isolated 'Golden Delicious' apple fruit cuticles with regard to calcium. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 114 (5): 804-809.

- Glenn, G. M., & Poovaiah, B. W. (1985). Cuticular permeability to calcium compounds in ‘Golden Delicious’ apple fruit. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 110(2), 192-195.

- Schlegel, T. K., & Schönherr, J. (2002). Penetration of calcium chloride into apple fruits as affected by stage of fruit development. Acta Horticulturae, 594: 527-533.

- Wojcik, P. (2001). Effect of calcium chloride sprays at different water volumes on “Szampion” apple calcium concentration. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 24(4-5), 639-650.

- Sarijan, A., Limbongan, A. A., Ekowati, N. Y., & Kusumah, R. (2025, March). Calcium nitrate application on tomatoes to increase blossom-end rot disease resistance. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 1471, No. 1, p. 012025). IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Assaha, D. V., & Petang, L. Y. (2024). Bone meal enhances the growth and yield of the tomato cultivar Cobra F1 by increasing fruit Ca content and alleviating blossom-end rot. Asian Journal of Agriculture, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Madani, B., Mirshekari, A., Sofo, A., & Tengku Muda Mohamed, M. (2016). Preharvest calcium applications improve postharvest quality of papaya fruits (Carica papaya L. cv. Eksotika II). Journal of Plant Nutrition, 39(10), 1483-1492. [CrossRef]

- Parsa, Z., Roozbehi, S., Hosseinifarahi, M., Radi, M., & Amiri, S. (2021). Integration of pomegranate peel extract (PPE) with calcium sulphate (CaSO4): A friendly treatment for extending shelf-life and maintaining postharvest quality of sweet cherry fruit. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 45(1), e15089. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J., Gao, Y., Zhang, X. W., Han, L. J., Bi, H. A., Li, Q. M., & Ai, X. (2019). Effects of silicon and calcium on photosynthesis, yield and quality of cucumber in solar-greenhouse. Acta Hortic. Sin., 46: 701–713. 10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2018-0687.

- Ahn, J., Park, M., Kim, J., Huq, E., Kim, J., & Kim, D. H. (2024). Physiological and transcriptomic analyses of healthy and blossom-end-rot (BER)-defected fruit of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum. L.). Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, I. B., & Watkins, C. B. (1989). Bitter pit in apple fruit. Horticultural Reviews, 11, 289-355. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, I. B., & Watkins, C. B. (1983). Cation distribution and balance in apple fruit in relation to calcium treatments for bitter pit. Scientia Horticulturae, 19(3-4), 301-310. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Takemoto, T., Omwange, K. A., Orsino, M., Konagaya, K., & Kondo, N. (2025). Early detection of Blossom-End Rot in green peppers using fluorescence and normal color images in visible region. Food Control, 172, 111156. [CrossRef]

- Karley, A. J., & White, P. J. (2009). Moving cationic minerals to edible tissues: potassium, magnesium, calcium. Current opinion in plant biology, 12(3), 291-298. [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S. T., Shackel, K. A., & Mitcham, E. J. (2011b). Abscisic acid triggers whole-plant and fruit-specific mechanisms to increase fruit calcium uptake and prevent blossom end rot development in tomato fruit. Journal of Experimental Botany, 62(8), 2645-2656. [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.C., 1989. Environmental effects on the diurnal accumulation of 45Ca by young fruit and leaves of tomato plants. Annals of Botany, 63(2), 281-288. [CrossRef]

- Ho, L. C., Belda, R., Brown, M., Andrews, J., & Adams, P. (1993). Uptake and transport of calcium and the possible causes of blossom-end rot in tomato. Journal of Experimental Botany, 44(2), 509-518. [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T., Nichols, M.A., Hewett, E.W., Fisher, K.J., 2001. Relative humidity around the fruit influences the mineral composition and incidence of blossom-end rot in sweet pepper fruit. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 76(1), 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A. M. (2007). Nutrient remobilization during leaf senescence. Annual Reviews of Senescence Processes in Plants, 26, 87-107.

- Marschner, P. (2011). Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Academic press: Cambridge, MA, USA; ISBN 9780123849052.

- Bar-Tal, A., Aloni, B., Karni, L., Oserovitz, J., Hazan, A., Itach, M., ... & Rosenberg, R. (2001). Nitrogen nutrition of greenhouse pepper. I. Effects of nitrogen concentration and NO3: NH4 ratio on yield, fruit shape, and the incidence of blossom-end rot in relation to plant mineral composition. HortScience, 36(7), 1244-1251.

- Schönherr, J., & Bukovac, M. J. (1973). Ion exchange properties of isolated tomato fruit cuticular membrane: exchange capacity, nature of fixed charges and cation selectivity. Planta, 109, 73-93. [CrossRef]

- Yermiyahu, U., Nir, S., Ben-Hayyim, G., & Kafkafi, U. (1994). Quantitative competition of calcium with sodium or magnesium for sorption sites on plasma membrane vesicles of melon (Cucumis melo L.) root cells. The Journal of Membrane Biology, 138, 55-63. [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S. T., do Amarante, C. V., Labavitch, J. M., & Mitcham, E. J. (2010). Cellular approach to understand bitter pit development in apple fruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 57(1), 6-13. [CrossRef]

- Dris, R., Niskanen, R., & Fallahi, E. (1998). Nitrogen and calcium nutrition and fruit quality of commercial apple cultivars grown in Finland. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 21(11), 2389-2402. [CrossRef]

- Lanauskas, J., & Kvikliene, N. (2006). Effect of calcium foliar application on some fruit quality characteristics of ‘Sinap Orlovskij’apple. Agronomy Research, 4(1), 31-36.

- Gilliham, M., Dayod, M., Hocking, B. J., Xu, B., Conn, S. J., Kaiser, B. N., ... & Tyerman, S. D. (2011). Calcium delivery and storage in plant leaves: exploring the link with water flow. Journal of Experimental Botany, 62(7), 2233-2250. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Cheng, N. H., Pittman, J. K., Yoo, K. S., Park, J., Smith, R. H., & Hirschi, K. D. (2005). Increased calcium levels and prolonged shelf life in tomatoes expressing Arabidopsis H+/Ca2+ transporters. Plant Physiology, 139(3), 1194-1206.

- De Freitas, S. T., & Mitcham, E. I. (2012). 3 factors involved in fruit calcium deficiency disorders. Horticultural Reviews, 40(1), 107-146. [CrossRef]

- Picchioni, G. A., Watada, A. E., Conway, W. S., Whitaker, B. D., & Sams, C. E. (1998). Postharvest calcium infiltration delays membrane lipid catabolism in apple fruit. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 46(7), 2452-2457. [CrossRef]

- Lund, Z. F. (1970). The effect of calcium and its relation to several cations in soybean root growth. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 34(3), 456-459. [CrossRef]

- Caffall, K. H., & Mohnen, D. (2009). The structure, function, and biosynthesis of plant cell wall pectic polysaccharides. Carbohydrate Research, 344(14), 1879-1900. [CrossRef]

- Bush, D. S. (1995). Calcium regulation in plant cells and its role in signaling. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 46(1), 95-122. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, J. M., Dormer, R. L., & Campbell, A. K. (1992). Targeting aequorin to the endoplasmic reticulum of living cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 189(2), 1008-1016. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C. H., Knight, M. R., Kondo, T., Masson, P., Sedbrook, J., Haley, A., & Trewavas, A. (1995). Circadian oscillations of cytosolic and chloroplastic free calcium in plants. Science, 269(5232), 1863-1865. [CrossRef]

- Logan, D. C., & Knight, M. R. (2003). Mitochondrial and cytosolic calcium dynamics are differentially regulated in plants. Plant Physiology, 133(1), 21-24. [CrossRef]

- Pauly, N., Knight, M. R., Thuleau, P., Graziana, A., Muto, S., Ranjeva, R., & Mazars, C. (2001). The nucleus together with the cytosol generates patterns of specific cellular calcium signatures in tobacco suspension culture cells. Cell Calcium, 30(6), 413-421. [CrossRef]

- Voyle, G. (2021). Blossom end rot causes and cures in garden vegetables. Michigan State University Extension, MI, USA.

- de Freitas, S. T., Amarante, C. D., & Mitcham, E. J. (2016). Calcium deficiency disorders in plants. In: Postharvest Ripening Physiology of Crops, 477-502. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA. ISBN 9781498703819.

- Hocking, B., Tyerman, S. D., Burton, R. A., & Gilliham, M. (2016). Fruit calcium: transport and physiology. Frontiers in plant science, 7, 569. [CrossRef]

- Ren, H., Zhao, X., Li, W., Hussain, J., Qi, G., & Liu, S. (2021). Calcium signaling in plant programmed cell death. Cells, 10(5), 1089. [CrossRef]

- Ojha, R. K., & Jha, S. K. (2021). Role of mineral nutrition in management of plant diseases. Farmers’ Prosperity through Improved Agricultural Technologies, 241-261.

- Kleemann, M. (1999). Development of calcium deficiency symptoms in chervil (Antriscus cerefolium (L.) Hoffm.) and curled parsley (Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Nym. convar crispum). Zeszyty Problemowe Postępów Nauk Rolniczych, (468).

- Aloni, B., 1986. Enhancement of leaf tip burn by restricting root growth in Chinese cabbage plants. Journal of Horticultural Science, 61(4), 509-513. [CrossRef]

- Collier, G.F., Tibbitts, T.W., 1982. Tipburn of lettuce. Horticultural Reviews, 4, 49-65. [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.F., McKee, J.M.T., Dearman, A.S., 1976. The effect of growth rate on tipburn occurrence in lettuce. Journal of Horticultural Science, 51(3), 297-309. [CrossRef]

- Bible, B.B., Stiehl, B., 1986. Effect of atmospheric modification on the incidence of blackheart and the cation content of celery. Scientia Horticulturae, 28(1-2), 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Adams, P., & Holder, R. (1992). Effects of humidity, Ca and salinity on the accumulation of dry matter and Ca by the leaves and fruit of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Journal of Horticultural Science, 67(1), 137-142. [CrossRef]

- De Kreij, C., Janse, J., Van Goor, B. J., & Van Doesburg, J. D. J. (1992). The incidence of calcium oxalate crystals in fruit walls of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) as affected by humidity, phosphate and calcium supply. Journal of Horticultural Science, 67(1), 45-50. [CrossRef]

- Mengel, K., & Kirkby, E. A. (1987). Principles of Plant Nutrition. (No. Ed. 4, p. 687pp), , ISBNs: 978-1-4020-0008-9, 978-9-40-101009-2 . [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M. Y. (2019). Abiotic Factors Affecting Plant Physiology and Fruit Yield and Physiological Disorders in Bell Pepper and Tomato (Doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia). 219 p.

- Horst, W. J. (1987). Aluminium tolerance and calcium efficiency of cowpea genotypes. Journal of plant nutrition, 10(9-16), 1121-1129.

- Ho, L. C., Hand, D. J., & Fussell, M. (1997, May). Improvement of tomato fruit quality by calcium nutrition. In International Symposium on Growing Media and Hydroponics 481 (pp. 463-468). 10.17660/ActaHortic.1999.481.53.

- Ho, L. C., Adams, P., Li, X. Z., Shen, H., Andrews, J., & Xu, Z. H. (1995). Responses of Ca-efficient and Ca-inefficient tomato cultivars to salinity in plant growth, calcium accumulation and blossom-end rot. Journal of Horticultural Science, 70(6), 909-918. [CrossRef]

- Adams, P., & Ho, L. C. (1992). The susceptibility of modern tomato cultivars to blossom-end rot in relation to salinity. Journal of Horticultural Science, 67(6), 827-839. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M. O., Queiróz, M. D., & Souza, R. F. (1995). Incidence of blossom-end rot in five tomato cultivars grown in soil with three calcium levels. Horticultura Brasileira, 13 (2): 172-175.

- Sperry, W. J., Davis, J. M., & Sanders, D. C. (1996). Soil moisture and cultivar influence cracking, blossom-end rot, zippers, and yield of staked fresh-market tomatoes. HortTechnology, 6(1), 21-24.

- Maynard, D. N., Barham, W. S., & McCombs, C. L. (1957). The effect of calcium nutrition of tomatoes as related to the incidence and severity of blossom-end rot. In Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci, 318-22.

- Magán, J. J., Gallardo, M., Thompson, R. B., & Lorenzo, P. (2008). Effects of salinity on fruit yield and quality of tomato grown in soil-less culture in greenhouses in Mediterranean climatic conditions. Agricultural Water Management, 95(9), 1041-1055. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S., Singh, L., Debnath, B., Shukla, M., Kumar, S., Rana, M., & Meshram, S. (2022). Blossom end-rot (BER): an abiotic devastating disorder of tomato. Climate Change and Environmental Sustainability, 10(1), 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., Darvhankar, M., & Srivastava, S. (2019). Evaluation of Trichoderma species and fungicides on nutritional quality and yield of tomato. Pl. Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol, 20, 331-338.

- Das, K. A., Bhosale, R. K., Chavan, S. S., Rana, M., & Srivastava, S. (2023). Effect of physiological factors and different growth media on Alternaria solani under in vitro condition and eco-friendly management of early blight of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Ann Biol 39(1):66-72.

- Zhou, L., Fu, Y., & Yang, Z. (2009). A genome-wide functional characterization of Arabidopsis regulatory calcium sensors in pollen tubes. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 51(8), 751-761. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y., Irie, N., Vinh, T. D., Ooyama, M., Tanaka, Y., Yasuba, K. I., & Goto, T. (2014). Incidence of blossom-end rot in relation to the water-soluble calcium concentration in tomato fruits as affected by calcium nutrition and cropping season. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science, 83(4), 282-289. [CrossRef]

- Barickman, T. C., Kopsell, D. A., & Sams, C. E. (2014). Abscisic acid increases carotenoid and chlorophyll concentrations in leaves and fruit of two tomato genotypes. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 139(3), 261-266. [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S. T., Martinelli, F., Feng, B., Reitz, N. F., & Mitcham, E. J. (2018). Transcriptome approach to understand the potential mechanisms inhibiting or triggering blossom-end rot development in tomato fruit in response to plant growth regulators. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 37, 183-198. [CrossRef]

- R'him, T., & Jebari, H. (2008). Blossom-end rot in relation to morphological parameters and calcium content in fruits of four pepper varieties (Capsicum annuum L.). Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement,12 (4): 361-366.

- Grasselly, D., Rosso, L., Holgard, S., Cottet, V., Navez, B., Jost, M., & Berier, A. (2008). Soilless culture of tomato: effect of salinity of the nutrient solution. Infos-Ctifl, 239: 41-45.

- Robbins, W. R. (1937). Relation of nutrient salt concentration to growth of the tomato and to the incidence of blossom-end rot of the fruit. Plant Physiology, 12(1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Dekock, P. C., Hall, A., Inkson, R. H., & Alan Robertson, R. (1979). Blossom-end rot in tomatoes. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 30(5), 508-514. [CrossRef]

- Adams, P., & Ho, L. C. (1993). Effects of environment on the uptake and distribution of calcium in tomato and on the incidence of blossom-end rot. Plant and soil, 154, 127-132. [CrossRef]

- Pill, W. G., & Lambeth, V. N. (1981). Effects of soil water regime and nitrogen form on blossom-end rot, yield, water relations, and elemental composition of tomato. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science,105 (5): 730-734.

- Paiva, E. A. S., Sampaio, R. A., & Martinez, H. E. P. (1998). Composition and quality of tomato fruit cultivated in nutrient solutions containing different calcium concentrations. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 21(12), 2653-2661. [CrossRef]

- van Goor, B. J. (1974). Influence of restricted water supply on blossom-end rot and ionic composition of tomatoes grown in nutrient solution. Communications in soil science and plant analysis, 5(1), 13-24. [CrossRef]

- Franco, J. A., Perez-Saura, P. J., Ferná Ndez, J. A., Parra, M., & Garcia, A. L. (1999). Effect of two irrigation rates on yield, incidence of blossom-end rot, mineral content and free amino acid levels in tomato cultivated under drip irrigation using saline water. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 74(4), 430-435. [CrossRef]

- Franco, J., Bañón, S., & Madrid, R. (1994). Effects of a protein hydrolysate applied by fertigation on the effectiveness of calcium as a corrector of blossom-end rot in tomato cultivated under saline conditions. Scientia Horticulturae, 57(4), 283-292. [CrossRef]

- Marcelis, L. F. M., & Ho, L. C. (1999). Blossom-end rot in relation to growth rate and calcium content in fruits of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Journal of Experimental Botany, 50(332), 357-363. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. F., & Bould, C. (1976). Effects of shortage of calcium and other cations on 45Ca mobility, growth and nutritional disorders of tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 27(10), 969-977. [CrossRef]

- Saure, M. C. (2014). Why calcium deficiency is not the cause of blossom-end rot in tomato and pepper fruit–a reappraisal. Scientia Horticulturae, 174, 151-154. [CrossRef]

- Gent, M. P. (2007). Effect of degree and duration of shade on quality of greenhouse tomato. HortScience, 42(3), 514-520. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Perez, J.C., 2014. Bell pepper (Capsicum annum L.) crop as affected by shade level: fruit yield, quality, and postharvest attributes, and incidence of phytophthora blight (caused by Phytophthora capsici Leon.). HortScience 49 (7), 891–900. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.Y., Díaz-Pérez, J.C., Nambeesan, S.U. (2020). Effect of shade levels on plant growth, physiology, and fruit yield in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). In: XI International Symposium on Protected Cultivation in Mild Winter Climates and I International Symposium on Nettings and 1268, pp. 311–318. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.Y., Nambeesan, S.U., Bautista, J., Díaz-Pérez, J.C. (2022). Plant water status, plant growth, and fruit yield in bell pepper (Capsicum annum L.) under shade nets. Sci. Hortic. 303, 111241 . [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M. Y., Nambeesan, S. U., & Díaz-Pérez, J. C. (2024). Shade nets improve vegetable performance. Scientia Horticulturae, 334, 113326. [CrossRef]

- Jing, T., Li, J., He, Y., Shankar, A., Saxena, A., Tiwari, A., ... & Awasthi, M. K. (2024). Role of calcium nutrition in plant Physiology: Advances in research and insights into acidic soil conditions-A comprehensive review. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 108602. [CrossRef]

- Topcu, Y., Nambeesan, S. U., & van der Knaap, E. (2022). Blossom-end rot: a century-old problem in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) and other vegetables. Molecular Horticulture, 2(1), 1. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).