1. Introduction

Modern agriculture faces complex challenges, including rapidly expanding population demographics and growing environmental concerns [

1]. As the population continues to increase, the agricultural sector must address on of its greatest challenges: producing sufficient, safe, and nutritious food on a large scale to meet demand, while ensuring environmental sustainability [

2,

3]. Agricultural production in regions dominated by rainfed agricultural systems depends on the availability of rainfall, limiting yields and threatening the stability of local food sources [

4,

5]. Reconciling the need to improve crop yields with environmental management requires innovative approaches one promising avenue is the utilization of beneficial microorganisms, particularly plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria [

3].

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) are a group of bacteria that inhabit the root zone and possess the capacity to influence plant growth positively. The PGPR stimulates plant growth through various mechanisms, including the synthesis of phytohormones, phosphate solubilization, iron chelation via siderophore production, biological control of pests and diseases, and induction of plant tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses [

2,

6]. Among the most well-studied and commercially utilized PGPR is the genus

Azospirillum, a free-living nitrogen-fixing bacterium known for enhancing plant growth in various crops [

3].

Azospirillum brasilense has been extensively studied for its beneficial effects on a wide range of crops, including wheat, rice, soybean, and particularly maize, positioning it as a key element in the advancement of sustainable agricultural practices [

7,

8,

9,

10]. This bacterium promotes root development, improves nutrient assimilation, and increases overall plant vigor [

11]. Its contributions to plant growth are primarily attributed to its capacity to fix atmospheric nitrogen and synthesize phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid, gibberellins, and cytokinins, which collective stimulate root formation and promote plant development [

12]. Application methods include seed coating and in-furrow soil applications [

13,

14]. One in the soil,

A. brasilense colonizes the rhizosphere and stablishes close interactions with plant roots [

15].

Maize is essential for food security and a stable crop in Mexico, where most production depends on rain [

16]. To achieve optimal growth and high yield, maize cultivation requires substantial nitrogen fertilization, which often leads to environmental problems like greenhouse gas emissions and water contamination [

17,

18]. Moreover, maize cultivation under rainfed conditions is often exposed to water stress, which can significantly reduce crop yield [

19]. Rainfed agriculture in Mexico is affected by water scarcity limiting agricultural production.

In this context, PGPR represents a viable alternative to mitigate the environmental effects associated with conventional fertilization practices [

20]. When used in combination chemical fertilizers and PGPR like

A. brasilense can form synergistic interactions that may significantly influence yield and nutrient use efficiency in maize production [

14]. This research aims to evaluate the impact of

A. brasilense inoculation applied as either as seed treatment or in-furrow application, combined with full and half-dose nitrogen fertilization on grain yield of maize under rainfed conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in 2023 in the municipality of Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, Jalisco, located in the west-central region of Mexico (20° 27’ 13” N, 103° 26’ 18” W). According to the Köppen climate classification, the area has a semi-warm, sub-humid climate with summer rainfall (A)Ca(w1), an average temperature of 18.6 °C, an average annual precipitation of 944.7 mm, and an altitude of 1560 meters above sea level [

21].

2.2. Soil Sampling and Characteristics

A zigzag sampling method was used to collect soil samples. Six sampling points were identified within the plot, and 30 cm deep holes were dug at each point. From each hole, a soil sample was taken by scraping the walls. At the end, a composite sample was prepared and sent to the laboratory for analysis. The results are shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Inoculation of Azospirillum brasilense

Prior to sowing, seed inoculation with A. brasilense was performed. For this procedure, a portion of the seeds was submerged in a bacterial suspension (2 × 10¹² CFU/ per liter) by adding 151 mL of the suspension to a volume of water sufficient to completely cover the seeds, followed by thorough mixing. Simultaneously, another batch of seeds was soaked only in water to ensure a similar moisture content in both treatments. After 12 hours, the excess water was drained, and the seeds were left at room temperature to remove residual moisture before sowing. The in-furrow as spray inoculation was performed at the end of sowing by applying 151 mL of the bacterial suspension, diluted in seven liters of water.

2.4. Experimental Design

The experimental design followed a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD). Five treatments with three replicates were included (

Table 2). The experimental plots had a surface area of 42 m², measuring 6 m in length and 7 m in width, with a 1.5 m separation between plots.

2.5. Sowing and Crop Management

Maize was sown using a three-row mechanical planter at a density of 88,000 plants per hectare, with 87 cm spacing between rows. A commercial white hybrid maize seed, with medium yield potential for the western region of Mexico, was used.

Chemical fertilization consisted of the application of 218.4 kg ha⁻¹ of nitrogen (N), 176.8 kg ha⁻¹ of phosphorus (P₂O₅), 31.2 kg ha⁻¹ of potassium (K₂O), 124.8 kg ha⁻¹ of sulfur (S), 4.16 kg ha⁻¹ of magnesium (MgO), and 1.87 kg ha⁻¹ of zinc (Zn), applied in three split doses. In treatments T4 and T5, fertilizer doses were reduced by 50%.

Weed control was performed with 1350 g ha⁻¹ of atrazine, applied according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Insect control consisted of foliar spraying with 750 g ha⁻¹ of chlorpyrifos, carried out 25 days after plant emergence.

During crop development, four applications of a bacterial suspension were conducted by spraying at the base of the plant. This procedure was repeated monthly for four months until the crop reached physiological maturity. A total of 25.16 mL of the concentrated product diluted in water was applied per plot.

2.6. Data Collection

Data collection began at plant emergence, starting with measurements of plant height. This procedure was repeated periodically until the appearance of reproductive structures. For this monitoring, 30 plants were marked per replicate. Once the crop reached physiological maturity and the grain moisture content was 13%, manual harvesting was carried out in the 42 m² of each experimental plot. Subsequently, 30 ears per treatment were randomly selected to measure ear length and diameter using a measuring tape and caliper. After measurements were taken, the ears were shelled, and the grain weight was recorded using a digital scale. In addition, climatic data were recorded using a Davis Vantage Pro2 automatic weather station, monitoring maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation throughout the crop cycle.

In addition, root development was evaluated in 30 plants sampled seven days after emergence. The primary root length was measured, and the number of secondary roots was counted. The plants were grouped into three blocks according to the bacterial application method: in-furrow as spray, seed inoculation, and a control treatment with chemical fertilization only.

2.7. Data Analysis

The response variables evaluated were plant height, ear length and diameter, and grain yield. The collected data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, using the R statistical software (version 2024.12.0).

3. Results

3.1. Root Development

Significant differences in primary root length and the number of secondary roots were observed among groups, seven days after plant emergence (

p < 0.05). The greatest primary root length was recorded in the group where

A. brasilense was applied in-furrow as a spray, followed by the seed inoculation. The control group showed the lowest values (Figure 1). For the number of secondary roots, both bacterial application methods: spray and seed inoculation, resulted in significantly higher values compared to the control (

Table 3).

Figure 3.

Control group (a). Seed-inoculated bacterium (b). Bacterium applied as a spray (c).

Figure 3.

Control group (a). Seed-inoculated bacterium (b). Bacterium applied as a spray (c).

3.2. Vegetative Development of Plants

During the vegetative stage of the crop, plant height was evaluated. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) among treatments. The average plant height was 207.41 cm. Overall, the five treatments exhibited similar growth patterns, from germination and the emergence of the first true leaf to the end of the vegetative phase.

3.3. Ear Length

Visual differences in ear length were observed among the evaluated treatments. Treatments T4 and T5 showed the highest average lengths (10.83 cm), followed by T1 (10.78 cm), T3 (10.51 cm), and T2 (10.46 cm). However, the analysis of variance and Tukey’s mean comparison test did not reveal statistically significant differences among treatments (p > 0.05), as the difference between the highest and lowest mean was only 0.37 cm.

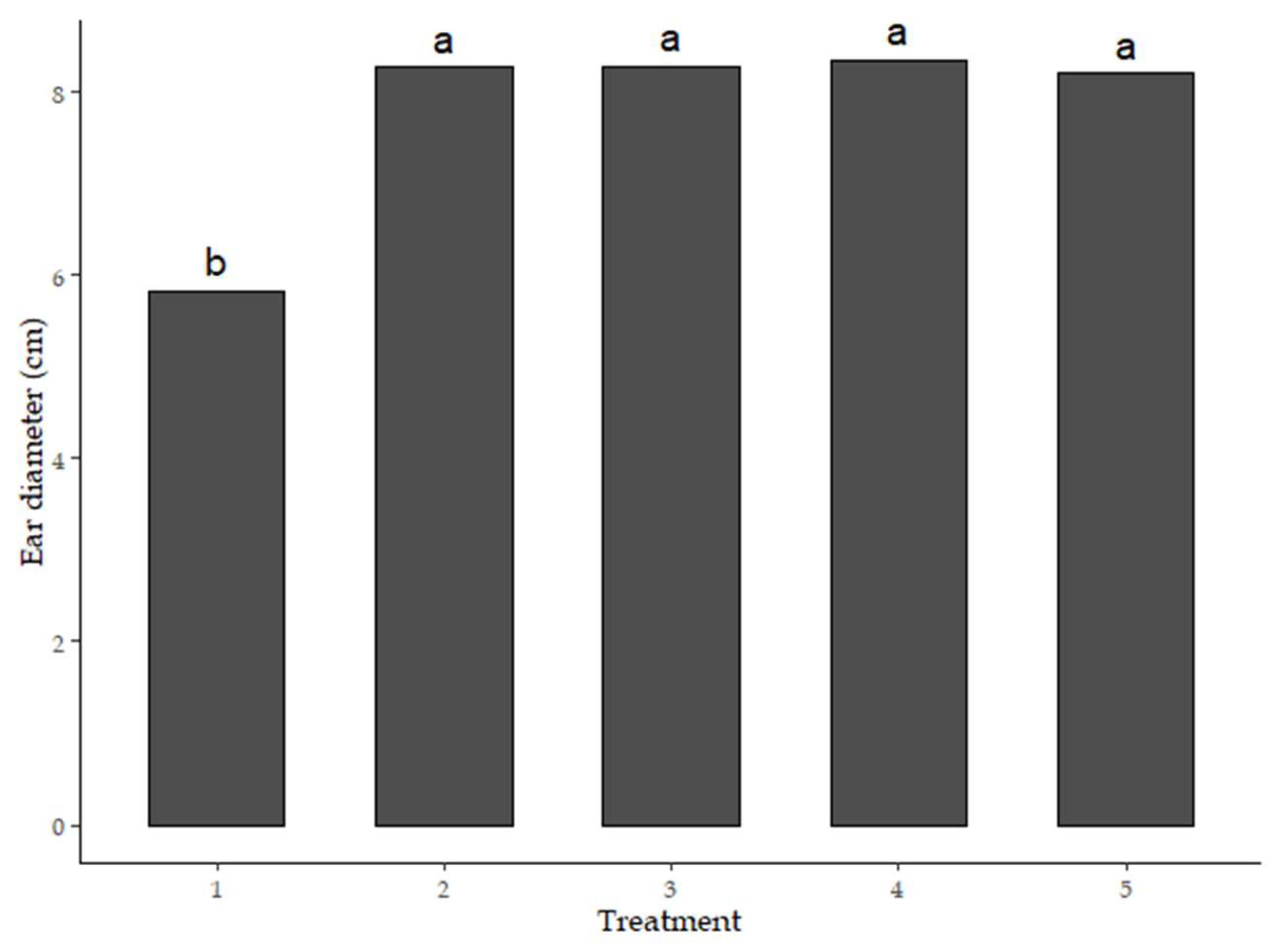

3.4. Ear Diameter

Ear diameter was one of the variables analyzed due to its relationship with the number of kernels per ear. At first glance, differences between treatments were not visually apparent, as the ears showed a similar external appearance. However, the mean diameter values (cm) recorded were as follows: T1 (5.83), T2 (8.25), T3 (8.28), T4 (8.35), and T5 (8.19). The analysis of variance revealed statistically significant differences among treatments (

p < 0.05). Tukey’s multiple comparison test indicated the formation of two statistically distinct groups, showing that treatment T1 differed significantly from the rest (

Figure 2).

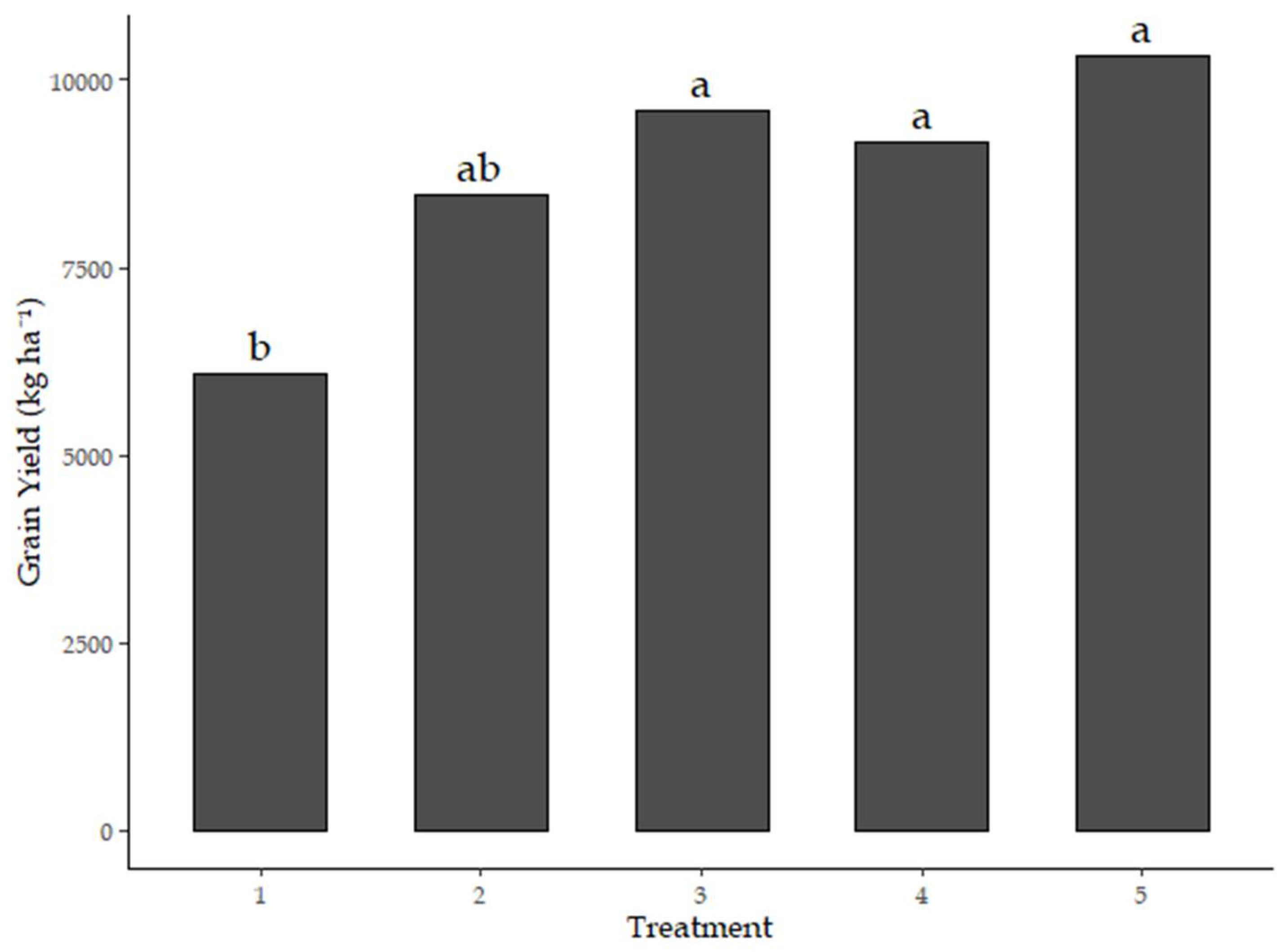

3.5. Grain Yield

The grain yield analysis revealed significant differences among the treatments applied (

p < 0.05). The average yield per plot, expressed in kilograms, was as follows: T1 (6,069.21), T2 (8,471.75), T3 (9,592.70), T4 (9,170.16), and T5 (10,336.51). A difference of 4,267.30 kg was observed between the highest-yielding treatment (T5) and the lowest (T1). The Tukey multiple comparison test identified three statistically distinct groups, indicating that the productive response varied considerably depending on the treatment applied (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Grain yield by treatment. Means expressed in kilograms per plot. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Grain yield by treatment. Means expressed in kilograms per plot. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

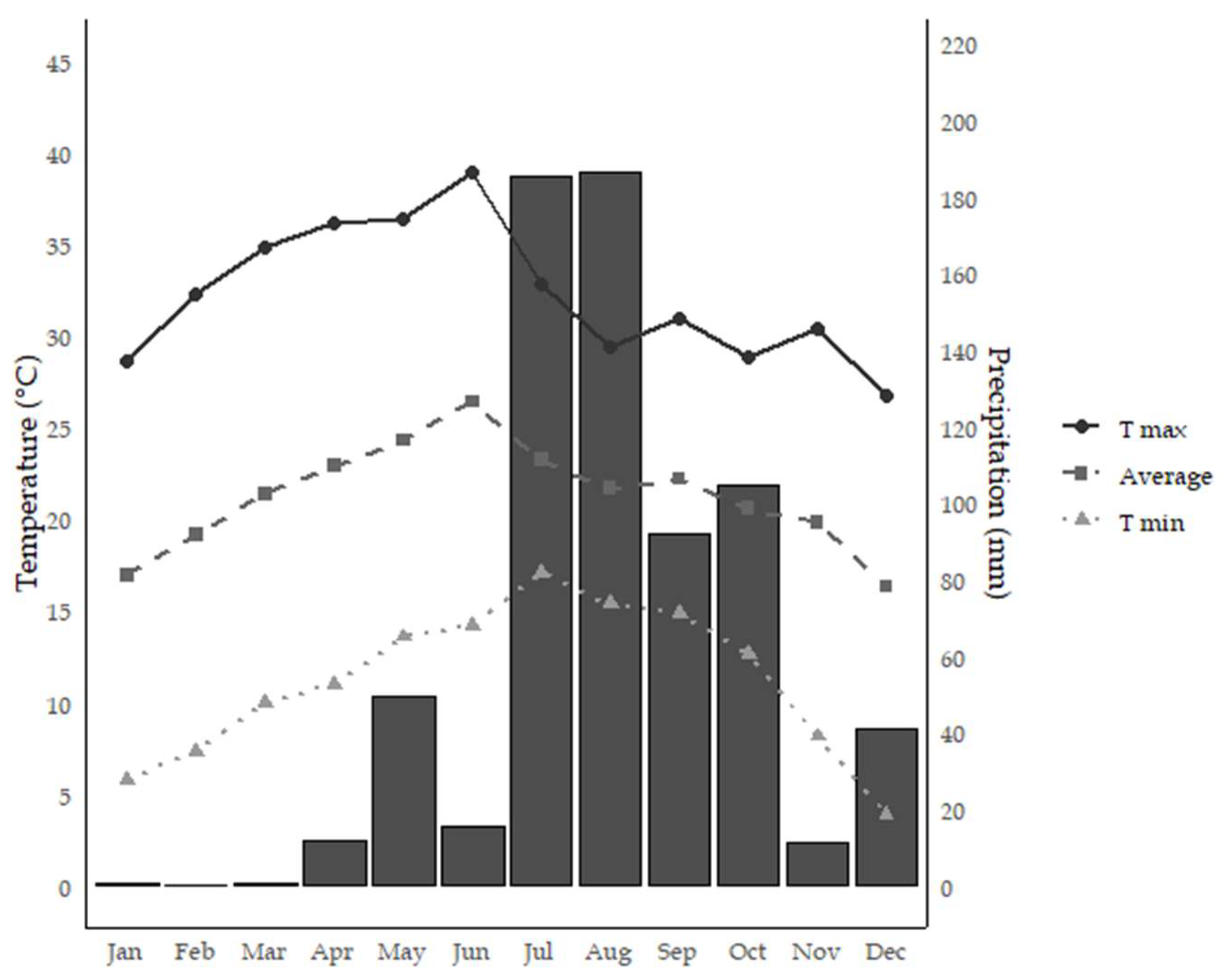

3.6. Climatic Conditions

During the study period (2023), total precipitation reached 697.8 mm, representing a reduction of 129.19 mm compared to the previous year (2022) and 104.52 mm compared to the following year (2024). Most of the rainfall was concentrated between July and October, while the remaining months experienced low or no precipitation.

Temperature fluctuations were considerable, ranging from a minimum of 3.92 °C to a maximum of 38.96 °C. The highest temperatures were recorded between July and October, coinciding with the maize crop development period (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that inoculation with A. brasilense, applied either as a seed treatment or through in-furrow spraying, significantly enhanced root system development, ear diameter, and grain yield of white maize under rainfed conditions during a water stress affected agricultural season. While plant height development did not show statistically significant differences between treatments, grain yield improved in the inoculated groups when nitrogen fertilization was reduced by 50%. These results highlight the capacity of A. brasilense to improve nutrient assimilation and underscore its potential as a biofertilizer within climate-smart strategies for sustainable maize production.

Root development of maize plants inoculated with

A. brasilense exhibited significantly longer primary roots and a greater number of secondary roots compared to the control group. These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the ability of

A. brasilense to promote root development through the synthesis of phytohormones, particularly indole-3-acetic acid, gibberellins, and cytokinins [

22,

23]. Furthermore [

13], reported that various application methods of

A. brasilense, including seed inoculation, in-furrow spraying, and foliar spraying, effectively enhanced root development in maize and wheat, improving water and nutrient uptake.

In rainfed agriculture, root development is a key trait. The observed improvements in root architecture in this study likely enhanced soil exploration and moisture uptake during atypically dry year (697.8 mm total precipitation, compared to the historical average of 944.7 mm). This finding is particularly relevant, as water scarcity represents a significant limitation for maize production in rainfed systems in Mexico [

16]. Our results contrast with those of [

24], who demonstrated that

A. brasilense inoculation under water stress conditions showed limited root development, however, they report the accumulation of key nutrients, such as potassium (K) and nitrogen (N) in maize tissues. This suggests that improved root system volume allows plants to access deeper moisture reserves, thereby mitigating damage from water stress [

13,

24].

Interestingly, ear length showed minor differences between treatments: T4 and T5 reached 10.83 cm, while T2 measured 10.46 cm. These results are consistent with those reported by [

25] who found no significant differences in ear length in maize plants inoculated with

A. brasilense. In contrast, ear diameter was significantly greater in all

A. brasilense inoculated treatments (8.25-8.35 cm) compared to the uninoculated control (5.83 cm). This suggests that the primary benefit of inoculation under water stress lies in enhancing ear circumference and kernel set, rather than in promoting ear elongation. This distinction is critical, as ear diameter is often more directly associated with kernel development and final yield particularly in environments where water availability is limited.

Our re Our results, while not directly measuring nutrient concentrations, suggest that yield and ear trait improvements in inoculated treatments were likely supported by enhanced nutrient acquisition, especially of phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). [

26] reported an increase P assimilation in maize inoculated with

A. brasilense, while [

24], showed greater K accumulation in the shoot and root of inoculated plants under drought conditions. This capacity to enhance nutrient availability and uptake efficiency is critical for maintaining yield under rainfed conditions, where nutrient diffusion in the soil is often limited by low moisture [

27].

An important aspect of our study was the comparison of application methods. Our data indicate that in-furrow spray application and seed inoculation improved root development and yield in rainfed conditions, with no differences observed in plant height. [

13] observed similar results, finding that seed inoculation and foliar spray are effective at improving yield. On the other hand, inoculation by soil spray and full N fertilization significantly improved plant height, which contrast with our findings. However, the absence of height differences indicates that in water stress scenarios, root system architecture is related to yield gains rather than vegetative biomass, underscoring the importance of root development to improve productivity in rainfed maize. Furthermore, [

28] showed similar results using seed with

A. brasilense, foliar spray, and application of soil bioactivator, finding higher heights and no affected yield. This suggests that application flexibility (seed, in-furrow, foliar) allows for integration into diverse farming systems, particularly where seed treatment infrastructure is unavailable or incompatible with chemical seed treatments.

5. Conclusions

This study confirmed that inoculation with A. brasilense has a positive effect on root development, ear diameter, and grain yield in maize under rainfed conditions and water stress. Although no statistically significant differences were observed in plant height or ear length, the results highlight the potential of A. brasilense to enhance crop tolerance to adverse conditions such as drought and reduced chemical fertilization.

The research also indicates that in-furrow spraying of the bacterial solution can be as effective as seed inoculation, thereby expanding the applicability of A. brasilense across various agricultural contexts. This flexibility in application is advantageous in settings where seed treatment infrastructure is limited.

However, further field trials across multiple growing seasons and agroecological regions are recommended. These should aim to monitor the persistence of A. brasilense in the soil, its interaction with the microbiome, and its physiological impact on plants under abiotic stress. The integration of A. brasilense with rational fertilization practices may offer synergistic benefits, particularly in soils with low phosphorus and potassium availability. These findings reinforce the value of microbial inoculants as key tools for more sustainable, resilient, and climate-smart agriculture, especially in rainfed production systems where water stress is a common constraint.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.G. and G.A.G.; Formal analysis, J.A.G.; Methodology, R.AM.I., G.B.M. and M.A.M.A; Writing – original draft, J.A.G and G.A.G; Writing – review & editing, JA.G., G.B.M, M.A.M.A. and G.A.G. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are provided within the manuscript. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Centro de Investigación Agropecuaria y del Medio Ambiente de Tlajomulco (CIAMAT) for providing the facilities that enabled the successful completion of this research. Special thanks for their support to the social service and professional internship students from the Ingeniero Empresarial Agropecuario program at the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nazarova, N.; Sazhneva, L.; Sakhbieva, A.; Kokhreidze, M. Biotechnology and its contribution to the agricultural economy: Using microbes for increasing crop yields. BIO Web Conf 2024, 141, 1024. [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungría, M. Outstanding impact of Azospirillum brasilense strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 on the Brazilian agriculture: Lessons that farmers are receptive to adopt new microbial inoculants. Rev Bras Ci Solo 2021, 45, e028. [CrossRef]

- Siddhartha, P.S.; Debashish, B.; Goswami, A.; Kalpataru, D.M.; Animesh, G. A review on the role of Azospirillum in the yield improvement of non-leguminous crops. Afr J Microbiol Res 2012, 6, 1085–1091. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; McClean, C.J.; Büker, P.; Hartley, S.E.; Hill, J.K. Mapping regional risks from climate change for rainfed rice cultivation in India. Agric Syst 2017, 156, 76–84. [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, B.; Prasanna, B.M.; Hellin, J.; Bänziger, M. Crops that feed the world 6. Past successes and future challenges to the role played by maize in global food security. Food Secur 2011, 3, 307–327. [CrossRef]

- Khoso, M.A.; Wagan, S.; Álam, I.; Hussain, A.; Ali, Q.; Saha, S.; Poudel, T.R.; Manghwar, H.; Liu, F. Impact of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on plant nutrition and root characteristics: Current perspective. Plant Stress 2023, 11, 100341. [CrossRef]

- Licea-Herrera, J.I.; Velásquez, J.D.C.Q.; Hernández-Mendoza, J.L. Impacto de Azospirillum brasilense, una rizobacteria que estimula la producción del ácido indol-3-acético como el mecanismo de mejora del crecimiento de las plantas en los cultivos agrícolas. Rev Bol Quím 2020, 37, 34-39. [CrossRef]

- Mattos, M.L.T.; Valgas, R.A.; Martins, J.F.S. Evaluation of the agronomic efficiency of Azospirillum brasilense strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 in flood-irrigated rice. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3047. [CrossRef]

- Alhammad, B.A.; Zaheer, M.S.; Ali, H.H.; Hameed, A.; Ghanem, K.Z.; Seleiman, M.F. Effect of co-application of Azospirillum brasilense and Rhizobium pisi on wheat performance and soil nutrient status under deficit and partial root drying stress. Plants 2023, 12, 3141. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H.; Wang, N. A study of the different strains of the genus Azospirillum spp. on increasing productivity and stress resilience in plants. Plants 2025, 14, 267. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.J.; Fontes, J.R.A.; Pereira, B.F.F.; Muniz, A.W. Inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense increases maize yield. Chem Biol Technol Agric 2018, 5, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Coniglio, A.; Mora, V.; Puente, M.; Cassán, F. Azospirillum as biofertilizer for sustainable agriculture: Azospirillum brasilense AZ39 as a model of PGPR and field traceability. In: Sustainability in plant and crop protection. Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 45–59. [CrossRef]

- Fukami, J.; Nogueira, M.A.; Araújo, R.S.; Hungría, M. Accessing inoculation methods of maize and wheat with Azospirillum brasilense. AMB Express 2016, 6, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.C.; Pereira, C.B.; Correia, L.V.; Matera, T.C.; Santos, R.F.; Carvalho, C.; Osipi, E.A.F.; Braccini, A.L. Corn responsiveness to Azospirillum: Accessing the effect of root exudates on the bacterial growth and its ability to fix nitrogen. Plants 2020, 9, 923. [CrossRef]

- Behera, A.; Gorai, S.; Singh, R.; Ashrutha, M.A. Response of different endophytic bacterial strain on seedling growth and their co-inoculation on growth and development of maize plant (Zea mays L.) under laboratory condition and polyhouse condition. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 2020, 9, 2859–2868. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Sánchez, H.; Tadeo-Robledo, M.; Espinosa-Calderón, A.; Zaragoza-Esparza, J.; López-López, C. Water productivity and corn yield under different humidity availability. Rev. Mex. Cien. Agric, 2020,11, 1005-1016.

- Imran, M.; Ali, A.; Safdar, M.E. The impact of different levels of nitrogen fertilizer on maize hybrids performance under two different environments. Asian J Agric Biol 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Igiehon, N.O.; Babalola, O.O. Rhizosphere microbiome modulators: Contributions of nitrogen fixing bacteria towards sustainable agriculture. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15, 574. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.L.; Hua, Q.; Nie, L.X.; Zhang, W.J.; Zheng, H.B.; Liu, M.; Lin, Z.Q.; Gao, M. Effects of environment variables on maize yield and ear characters. Adv Mater Res 2013, 106, 726–731. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Tabassum, B.; Hashim, M.; Khan, N. Role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) as a plant growth enhancer for sustainable agriculture: A review. Bacteria 2024, 3, 59. [CrossRef]

- Alcalá-Gómez, J.; Medina-Esparza, L.; Tristán, T.Q.; Alcalá-Gómez, G. Impact of environmental factors on Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii infection in breeding ewes from western Mexico. Int. J. Biometeorol 2024, 69, 441-448. [CrossRef]

- Cassán, F.; Díaz-Zorita, M. Azospirillum sp. in current agriculture: From the laboratory to the field. Soil Biol Biochem 2016, 103, 117. [CrossRef]

- Bashan, Y.; de-Bashan, L.E. How the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum promotes plant growth—A critical assessment. Adv Agron 2010, 77. [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.M.; Magalhães, P.C.; Marriel, I.E.; Gomes, C.C.; Silva, A.B.; Melo, I.G.; Souza, T.C.D. Azospirillum brasilense favors morphophysiological characteristics and nutrient accumulation in maize cultivated under two water regimes. Rev Bras Milho Sorgo 2020, 19, 17. [CrossRef]

- Ávalos, D.F.L.; Ocampo, F.D.V.; Bogarin, N.F.L.; López, E.M.; Pereira, W.D.L.; Casuriaga, O.L.C.; Oviedo, M.O.D.S.; Niz, A.I.S.; Jara, R.S. Effect of different doses of nitrogen and inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense on the productive characteristics of maize. J Exp Biol Agric Sci 2024, 12, 257–265. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.C.M.; Galindo, F.S.; Gazola, R.P.D.; Dupas, E.; Rosa, P.A.L.; Mortinho, E.S.; Filho, M.C.M.T. Corn yield and phosphorus use efficiency response to phosphorus rates associated with plant growth promoting bacteria. Front Environ Sci 2020, 8, 00040. [CrossRef]

- Keteku, A.K.; Yeboah, P.A.; Yeboah, S.; Dormatey, R.; Agyeman, K.; Brempong, M.B.; Ghanney, P.; Poku, S.A.; Danquah, E.O.; Frimpong, F.; Addy, S.; Bosompem, F.; Aggrey, H. Plant nutrition in relation to water-use efficiency in crop production: A review. AGRICA 2024, 17, 67. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.W.; Guimarães, V.F.; Brito, T.S.; Röske, V.M.; Cecatto, R.; Silva, A.S.L.; Weizenmann, J.C. Inoculation methods of Azospirillum brasilense associated to the application of soil bioactivator in the maize crop. Commun Plant Sci 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).