1. Introduction

The protein kinase C (PKC) contributes to the malignant progression of several cancers and pushes past some of the cellular defense mechanisms. It is an enzymatic family of proteins that contributes to carcinogenesis through the action of phosphorylating serine/threonine residues of proteins in cancer cascades [

1]. These serine/threonine kinases are generally activated by various stimulating factors such as hormones, growth factors, and neurotransmitters [

2,

3]. There are three classifications within the PKC family: conventional PKC-α, PKC-βI, and PKC-βII (splice variant) and PKC-γ; novel PKC-δ, PKC-ε, PKC-η and PKC-θ; these two isozyme groups need the neutral lipid diacylglycerol (DAG) as their common activator, where the conventional type needs calcium (Ca

2+) additionally. The atypical PKC-ζ and PKC-ι/λ require acidic phospholipids, phosphatidylinositol-1, 3, 5-(PO

4)

3 (PIP

3), and phosphatidic acid (PA) instead of DAG for their activation [

4,

5].

Both atypical PKCs participate in modulating cancer-promoting cell signaling path-ways [

6]. Several in vitro studies, focusing on glioma, melanoma, ovarian and renal cancer cells, indicate the presence of overexpression and the relevance of the PKC-ι oncogene in various cellular mechanisms [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Although PKC-ι and PKC-ζ have a close homology (72% overall similar sequence and 84% similar in the catalytic domain), PKC-ι is heavily implicated in regulating tumorigenesis. These characteristics make it a known prognostic biomarker and a therapeutic target [

6,

11,

12,

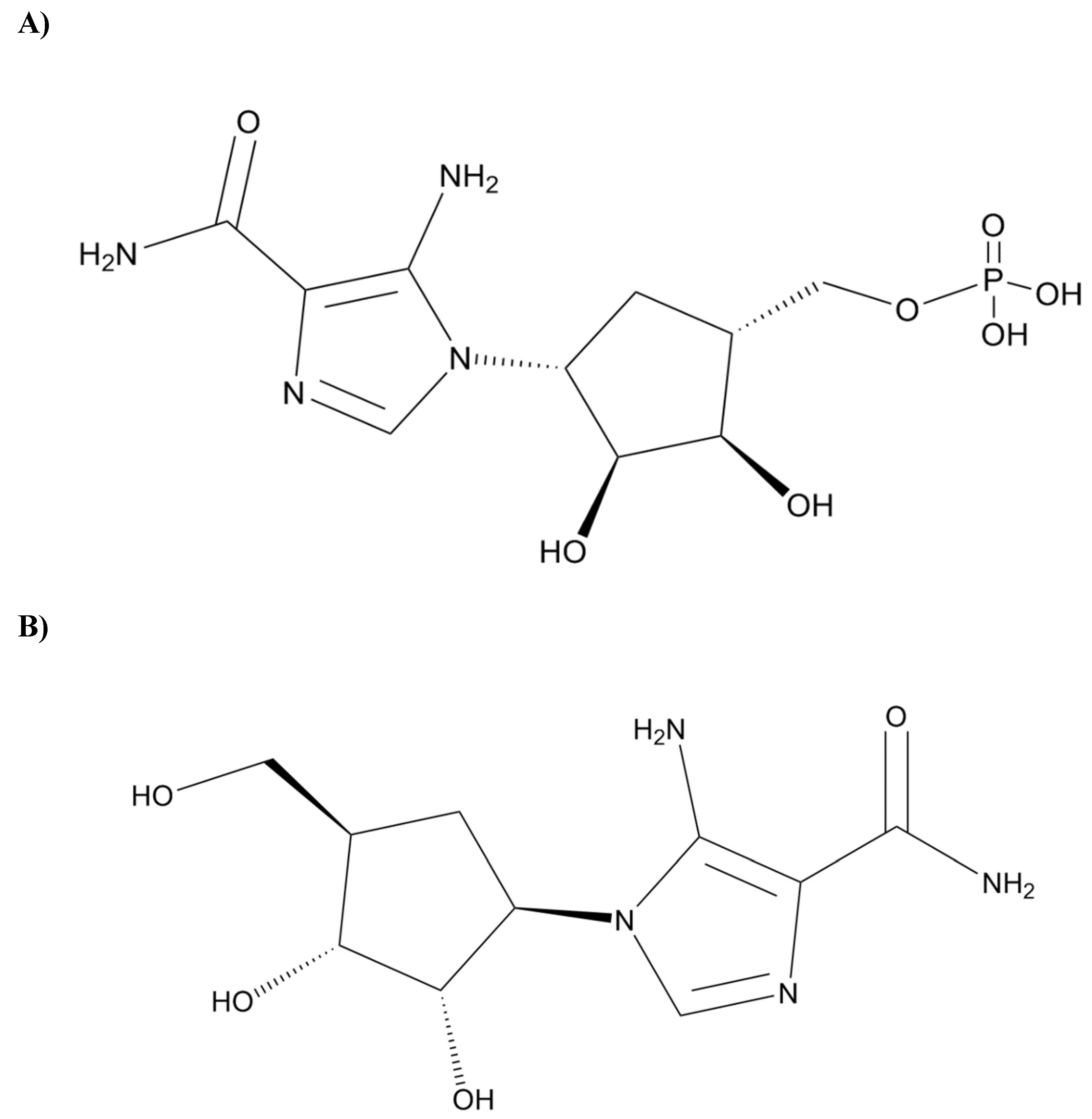

13]. In a previous study, Pillai et al. demonstrated that ICA-1T (

Figure 1A) an experimental drug, explicitly inhibits the kinase activity of PKC-ι over PKC-ζ in the presence of myelin basic protein (MBP), a common substrate of PKCs. In addition, ICA-1T exhibited an inhibitory effect inversely proportional to the varying concentrations of MBP, indicating a competitive mode of inhibition [

12]. Moreover, in previous in vivo toxicological studies with acute and chronic murine models, ICA-1S (

Figure 1B), an analog of ICA-1T, has shown reduced toxicity levels [

14,

15]. These prior developments necessitate further study to obtain insights into the binding interactions between PKC-ι and these specific inhibitors. Therefore, this study was conducted from a biophysical perspective to address this knowledge gap.

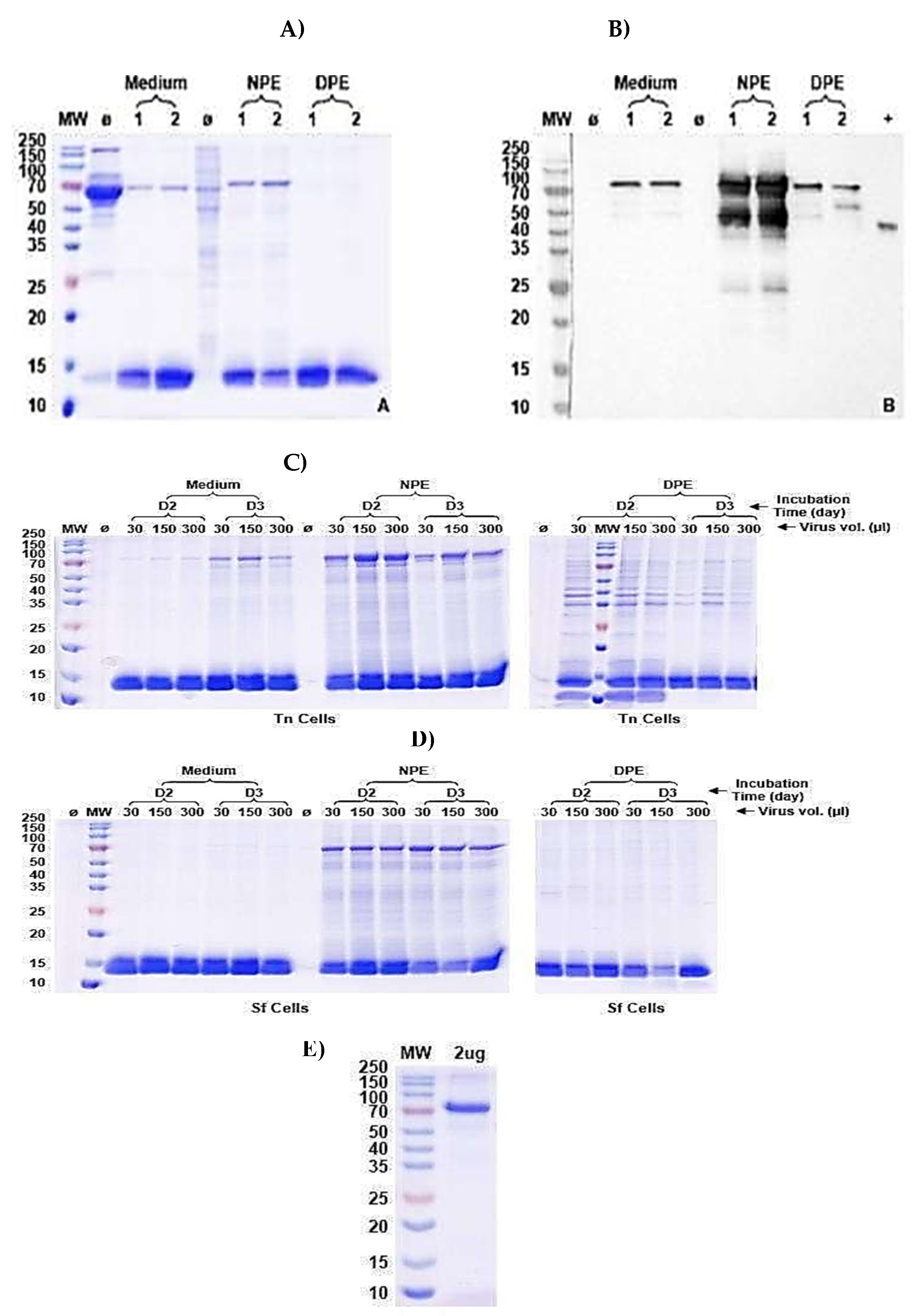

Publications reveal that the full-length and catalytic domain of atypical PKCs is best expressed in insect cell lines due to post-translational modifications (PTMs) and the abundance of eukaryotic protein synthesis machinery [

16,

17]. Messerschmidt et al. found that the expressed catalytic domain of PKC-ι had a higher molecular mass than predicted using mass spectrometry. However, treatment with the lambda-phosphatase followed by mass spectrometry resulted in a lower molecular mass determination of the purified protein domain. This observation suggested that the post-translational modifications resulted in phosphorylation at one, two, or three different sites within the protein structure [

18]. Therefore, in this project, to maintain the optimal environment for PTMs of full-length PKC-ι, High Five Cells (hi5), derived from the ovaries of cabbage loopers (Trichoplusia ni, hereafter referred to as Tn cells) and SF9 cells, derived from the ovaries of Spodoptera frugiperda, were utilized [

19]. The Tn cells showed better expression levels during the test expression phase (details in the Materials and Methods section); therefore, the PKC-ι obtained for this study was expressed accordingly from Tn cells.

After an in silico screening of 300,000 compounds (MW<500), 30 potential candidate molecules (Hit), including ICA-1T, a small molecule inhibitor, were selected for specific structural pockets of PKC-ι. In previous investigations, PKC-ι was found to be inhibited by ICA-1T, as determined via in vitro assays and computational analysis. According to the molecular docking results, it was found that ICA-1T interacts with the 469-475 amino acid residues of the catalytic domain of PKC-ι (PDB: 1ZRZ) [

12]. In this investigation, besides ICA-1T, we studied the intricate binding interactions and conformational stability profile of PKC-ι while interacting with ICA-1S. The compound is a non-phosphorylated nucleosidic homolog of ICA-1T, which contains a hydroxymethyl group attached in the ‘cyclopentyl’moiety. We have applied micro scale thermophoresis (MST), nano differential scanning fluorimetry (nanoDSF), dynamic light scattering (DLS), and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to understand the biophysical properties of the interactions and further corroborate our previously published in vivo, in vitro, and in silico findings [

10,

15]. The pre-conditional validation and protein-ligand complex stability characterization were studied with the state-of-the-art instrument PR.Panta by NanoTemper Technologies. The instrument combines multiple characterization factors such as thermal stability, protein folding status, aggregation, turbidity information, and protein self-association during the protein-ligand conjugate formation [

20,

21]. This multi-parameter information on protein conformational and colloidal stability is crucial in determining the optimum conditions for the protein ligand affinity study. In PR.Panta control outputs software (NanoTemper Technologies) Onset (

TON) is a parameter that marks the temperature at which a physical change in the protein molecule, such as unfolding, size increase (cumulant radius), or aggregation, initiates. It must not be exceeded for any subsequent experiments. The inflection point (

IP) is the temperature at which these biophysical properties change to their maximum, and the corresponding first derivative plots are used to visualize.

The conformational stability profile of the protein domains due to the introduction of the ligand in the bound state is a crucial factor to understand [

22]. Moreover, the buffer system used during experiments must suit the protein-drug affinity study [

23]. PR.Panta provides this information on the target protein by utilizing DLS. In brief, the DLS technique (also known as photon correlation spectroscopy) quantifies the Brownian motion of a protein in a solution as the macromolecules are constantly being collided with solvent molecules. The omnidirectional nature and light intensity of the incident laser light on the macromolecule in motion are detected. The continuous motion of the large-sized molecules, such as proteins in solution, will cause a Doppler broadening of both mutually constructive and destructive phases to produce detectable signals. The mathematical correlation of light intensity fluctuations of the scattered light with respect to time in ns-

µs level determines the level of rapid intensity fluctuations. This intensity change in scattered light gives insight into the diffusion behavior directly correlated to the homogeneity of the macromolecule [

24]. In PR. Panta DLS analysis, the cumulant fit model, first developed by Koppel in 1972, is a frequently used method for DLS data fitting. The autocorrelation function (ACF) was used to obtain a single averaged diffusion coefficient, which results in a single averaged hydrodynamic radius (rH) and a polydispersity index (PDI). Mathematically, the ACF is fit by a polynomial series expanding around the mean decay rate:

here, B is the baseline,

β is the amplitude, µ

2 is a factor for polydispersity, and

τ is the time increment. The mean decay rate Γ is proportional to the mean translational diffusion coefficient D, which calculates rH [

25].

The nano-differential scanning fluorimetry (nanoDSF) mechanism utilizes the intrinsic fluorescence of the aromatic side chains of hydrophobic residues like tryptophan and tyrosine in the protein structure. Unlike conventional DSF, the nanoDSF is a dye-free method that monitors the thermal unfolding as the microenvironment polarity of these hydrophobic residues changes [

26]. Moreover, the gradual unfolding of the protein structure exposes the tryptophan amino acid residues from the hydrophobic core, and the fluorescence emission spectra result in a redshift profile. The thermally denatured protein provides the intrinsic fluorescence signals at 350 nm (unfolded state emission maximum) and 330 nm (folded state emission maximum), plotted as a ratio against a temperature range. As the gradual exposure to the fluorescence source intensifies, a fluorescence intensity ratio of 350/330 nm is registered. Therefore, the unfolding profile of a protein based on fluorescence signals against temperature provides insight into the structural stability of a protein in the presence and absence of a ligand in a specific buffer [

27]. Consequently, the plot provides the biophysical perspective for understanding the transitions from folded to unfolded state with an inflection point (

IP), a parameter often interchangeably used with the melting points (

Tm). A multi-domain protein may exhibit more than one unfolding event or transition, as indicated by the IPs. If a protein’s stability changes due to a reason, such as introducing a foreign molecule, then its

IP will likely change [

28]. In general, the higher the

IP, the more stable the protein under investigation. Here, we have shown the protein unfolding and aggregation profiles of the PKC-ι with or without ICA-1S in phosphate-buffered saline, PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na

2HPO

4, and 1.8 mM KH

2PO

4, pH 7.4).

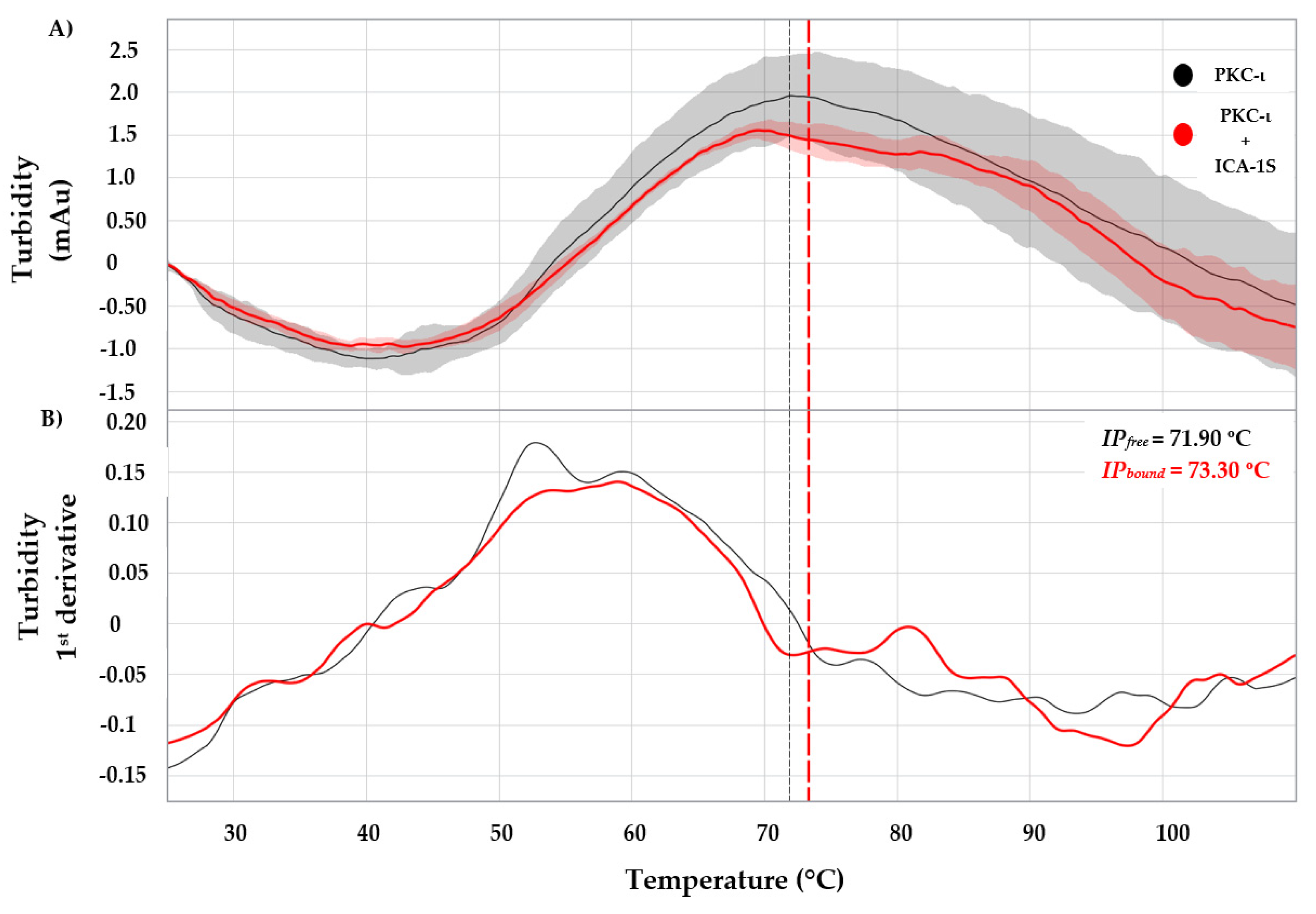

The turbidity profile describes the changes in the light scattering pattern due to the cloudiness of a solution caused by the suspended particles [

29]. The part of incident light from the light source is transmitted (non-scattered light) and is used for turbidity measurements. In the PR.Panta system, the turbidity is measured using the back-reflected part of the incident light (residual light) attenuation to understand the aggregation behavior of a protein sample. The back reflection technology mainly depends on a non-constant parameter called polarizability, other than constant parameters such as the angle between the detector and light source, the distance between the detector and the particle, the wave number and incident light intensity. Moreover, the intensity of the residual light back-reflected after a light scattering caused by a single particle depends on the refractive index and the diameter of the particle. In a protein sample with aggregates, the incident light will be scattered differently depending on the parameters above for each aggregate. As a result, the rest of the light will proportionally decrease based on the aggregate concentration. Therefore, the back-reflected light was measured in the PR. Panta system is influenced by the refractive index of the protein, particle diameter and aggregate concentrations. An increase in detected mAu indicates an increase in particle size and a decrease in the aggregate concentration. A higher IP in the turbidity profile indicates higher stability of the protein [

21]. The turbidity profile of a protein reflects the turbidity average and the inflection increase parameter for both the free-state and bound-state. The turbidity average is the average of all data points after the inflection point. MST uses infrared laser-induced localized temperature fields exerted on a molecule of interest during protein-ligand interaction analysis. The (bio-) molecules in motion due to the temperature fields become highly sensitive to the molecule-solvent interface (thermophoretic effect). During a binding event, minuscule changes in conformation, charge and molecular size induced by the interaction are quantified [

30]. When a molecule displays this directed movement due to the temperature gradient, then molecular size, effective surface charge and hydration entropy are affected.

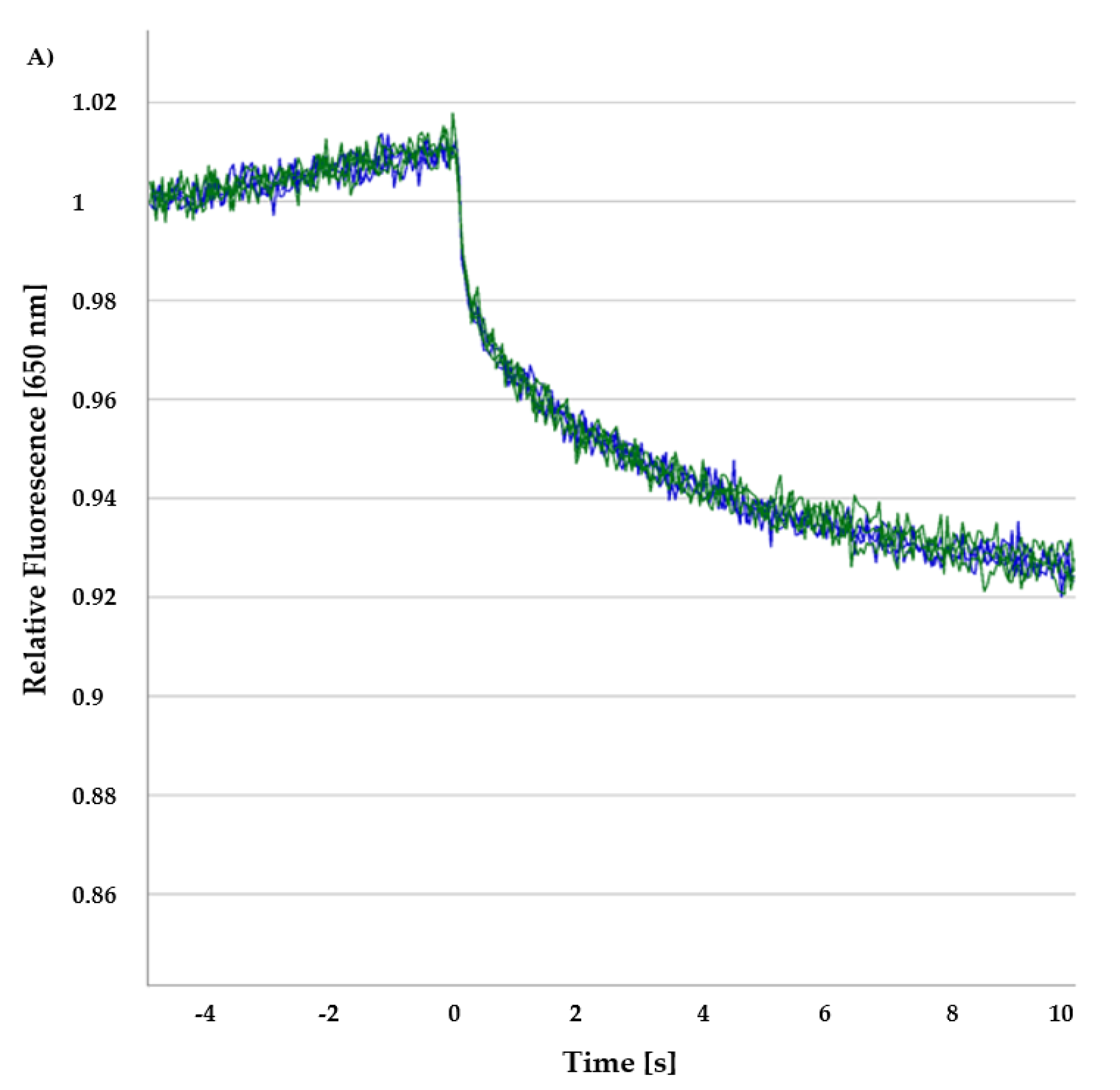

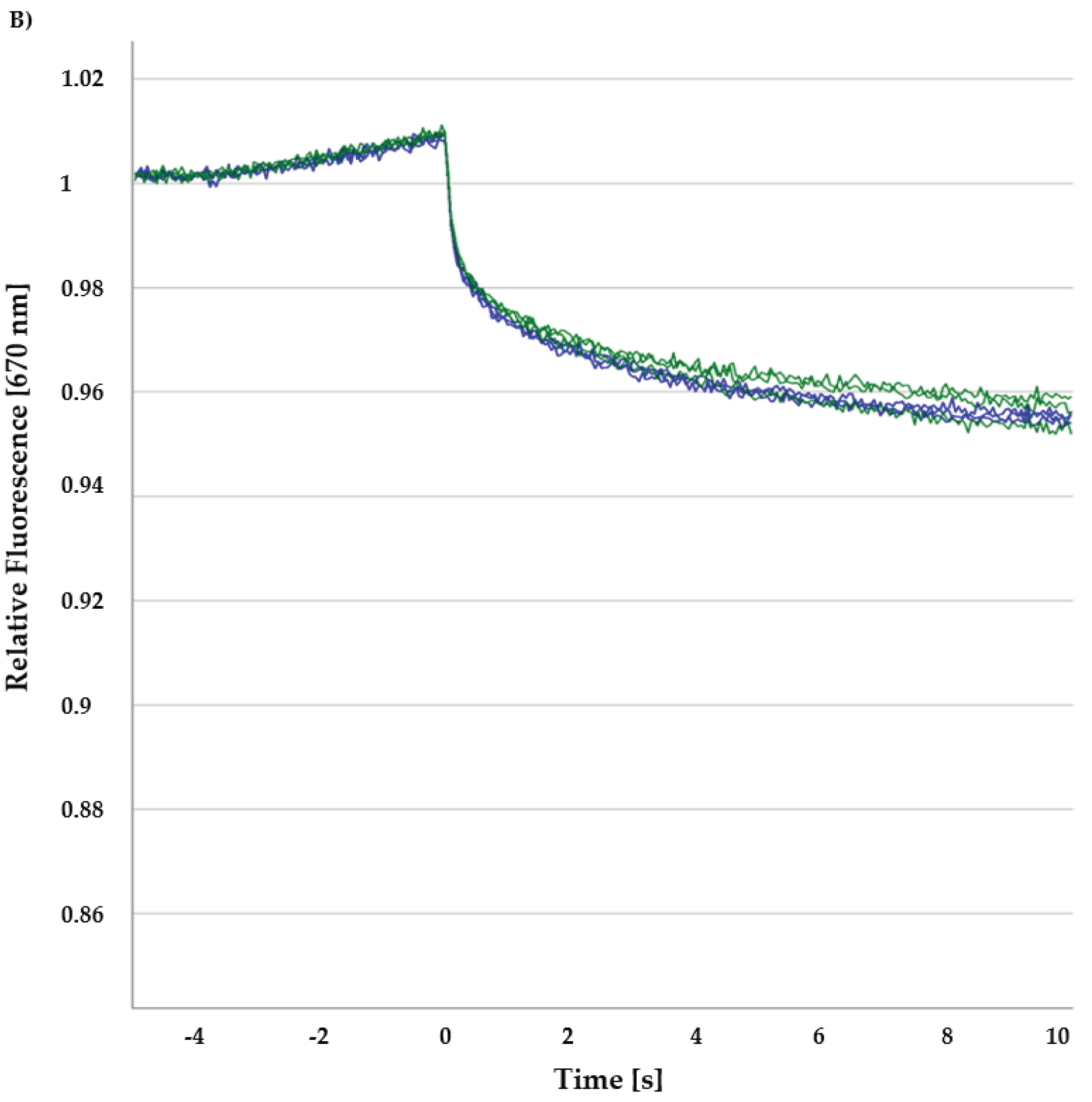

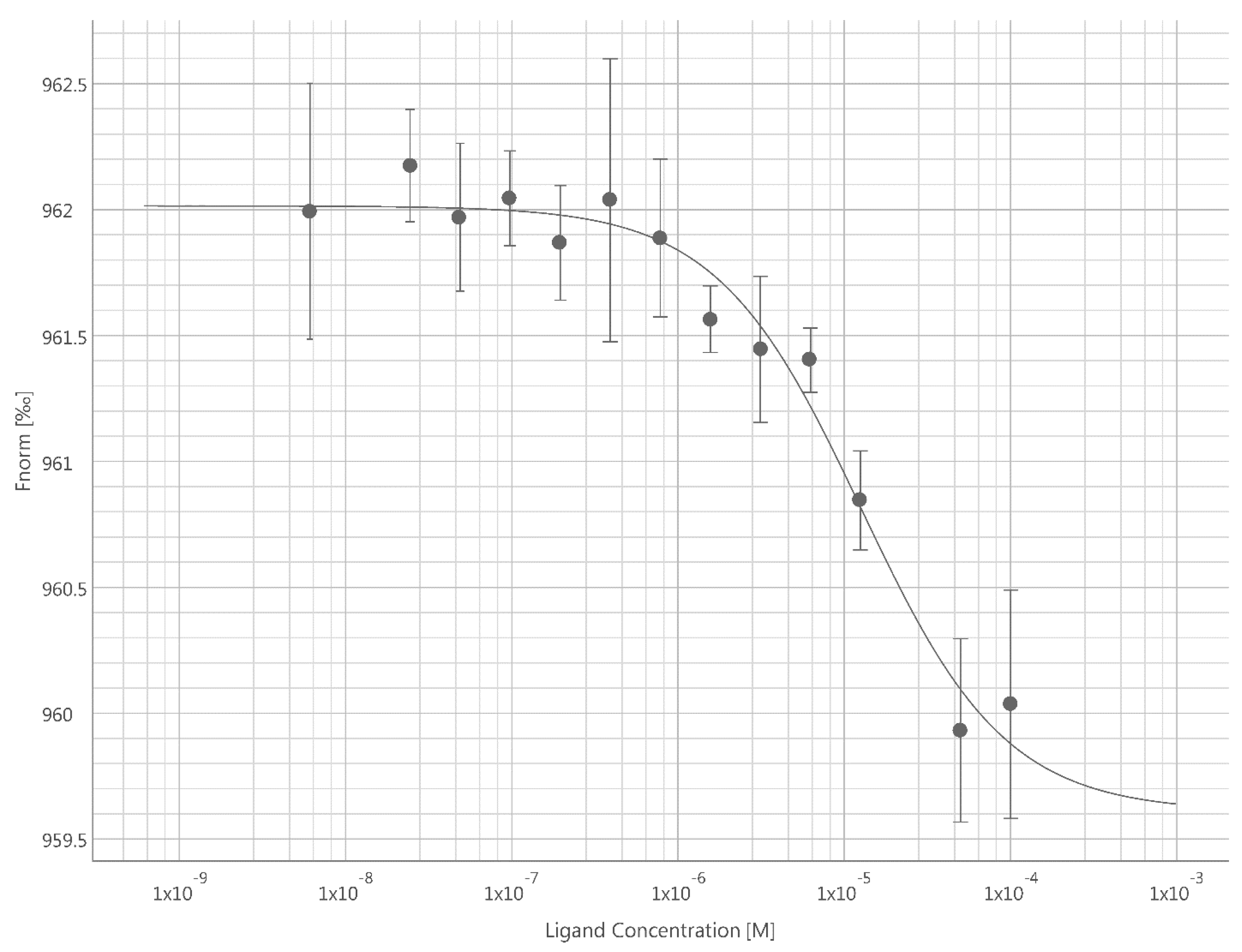

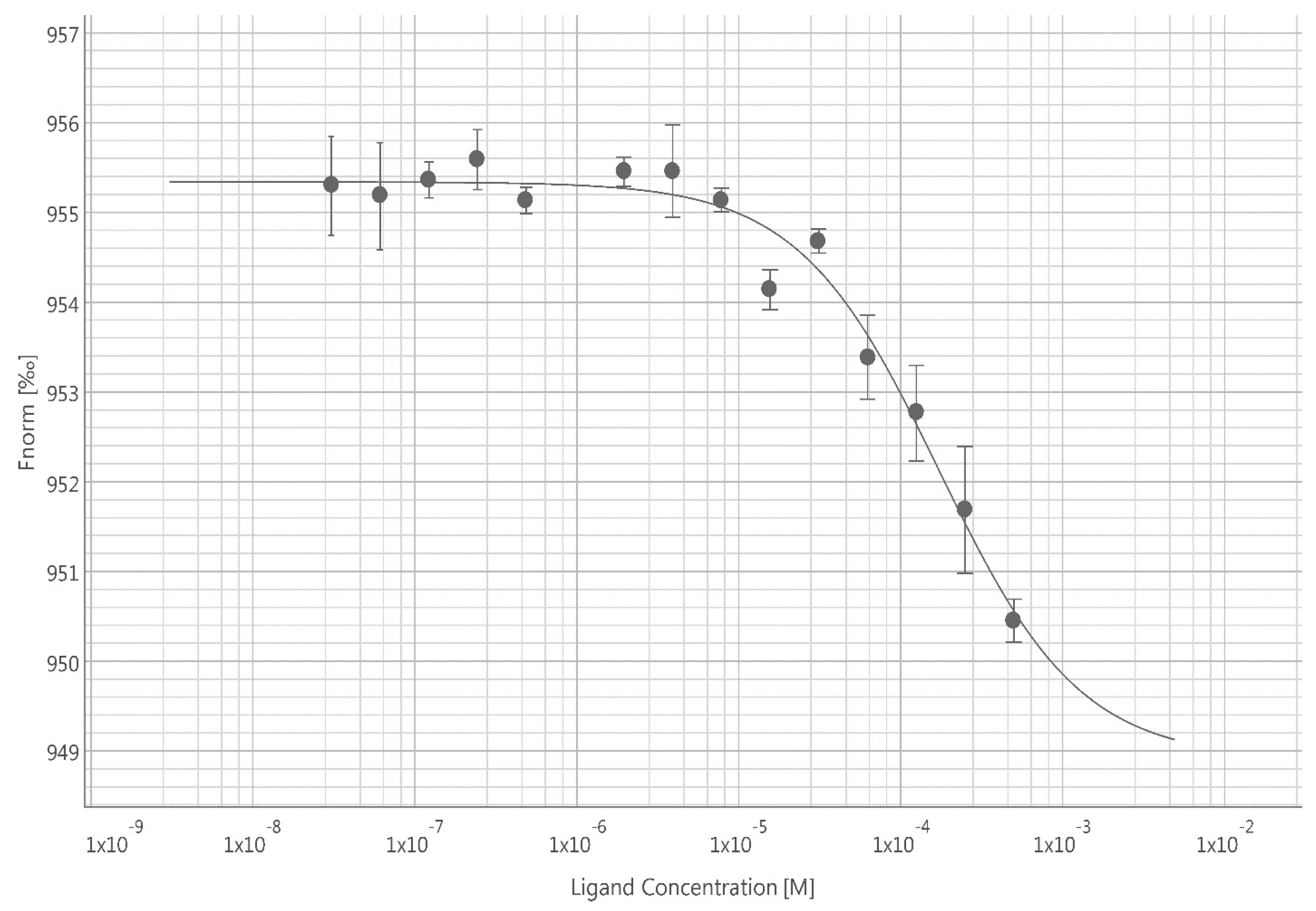

In MST, during a binding event, a local change in concentration results in a quantifiable fluorescence variation in the given sample, which is detected in MST as signals. Hence, when a protein-ligand reaches a binding equilibrium, an affinity constant can be measured where a fluorescence excitation/emission module is coupled with an infrared (IR) laser in the experimental setup. A

Kd is calculated for the interaction of two hetero molecules from measured normalized fluorescence (F

norm) [

31]. Usually, for MST analysis, the ratio of fluorescence values after 1 s and 30 s IR-laser heating is recorded with respect to the concentration of the ligand. In this way, the normalized fluorescence values are free from the initial temperature jump (T-jump) and only fluorescence changes due to the change in the concentrations are considered [

32,

33,

34].

In brief, ITC is a label-free method that measures the intricate heat transfer during a protein-ligand or protein-protein interaction in an adiabatic system. In the instrument, changes in heat energy are quantified based on a reference cell filled with water when the other cell contains the sample. The binding partner is injected from an injection syringe. A binding event results in a temperature difference between cells that is compensated by the instrument’s heaters. This heat compensation is represented by the differential power and utilized to obtain the thermodynamic parameters of the binding reaction. The binding event can be exothermic (heat-releasing) or endothermic (heat-absorbing) in nature. Depending on the heat exchange, the thermodynamic parameters such as enthalpy, entropy, free energy of reaction, and affinity can be calculated [

35] [

36].

3. Discussion

Since the development of the experimental drug ICA-1T as a PKC-ι specific inhibitor, several in vitro and in vivo studies have been performed. The early efficacy report of the ICA-1T highlighted its potential as a chemotherapeutic agent in inhibiting neuroblastoma cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis (Pillai, Desai et al. 2011) [

12]. This potential further inspired more research on the ICA-1T, and ICA-1S was introduced in the scenario. In an in vitro study, the T98G and U87MG glioblastoma cells were treated with ICA-1S in combination with TMZ (Temozolomide), demonstrating a significant inhibitory effect on cellular invasion pathways [

39]. Moreover, the acute and sub-acute toxicity studies in the murine models have shown a reduced toxicity level in prostate carcinoma tumors while treated with ICA-1S [

14]. Therefore, in these studies, both ICA-1T and ICA-1S demonstrated a potent inhibitory effect on PKC-ι, which regulates biological markers in crucial signaling pathways in various cancer cells. Despite these in vitro and in vivo successes, as a potential therapeutic compound, ICA-1S involved studies were missing vital information on binding characteristics and biophysical properties. In the present study, we report the chemical evidence of binding interactions between PKC-ι and ICA-1S/1T as evidenced by the dissociation constants and biophysical characterizations of the PKC-ι protein in complex with ICA-1S.

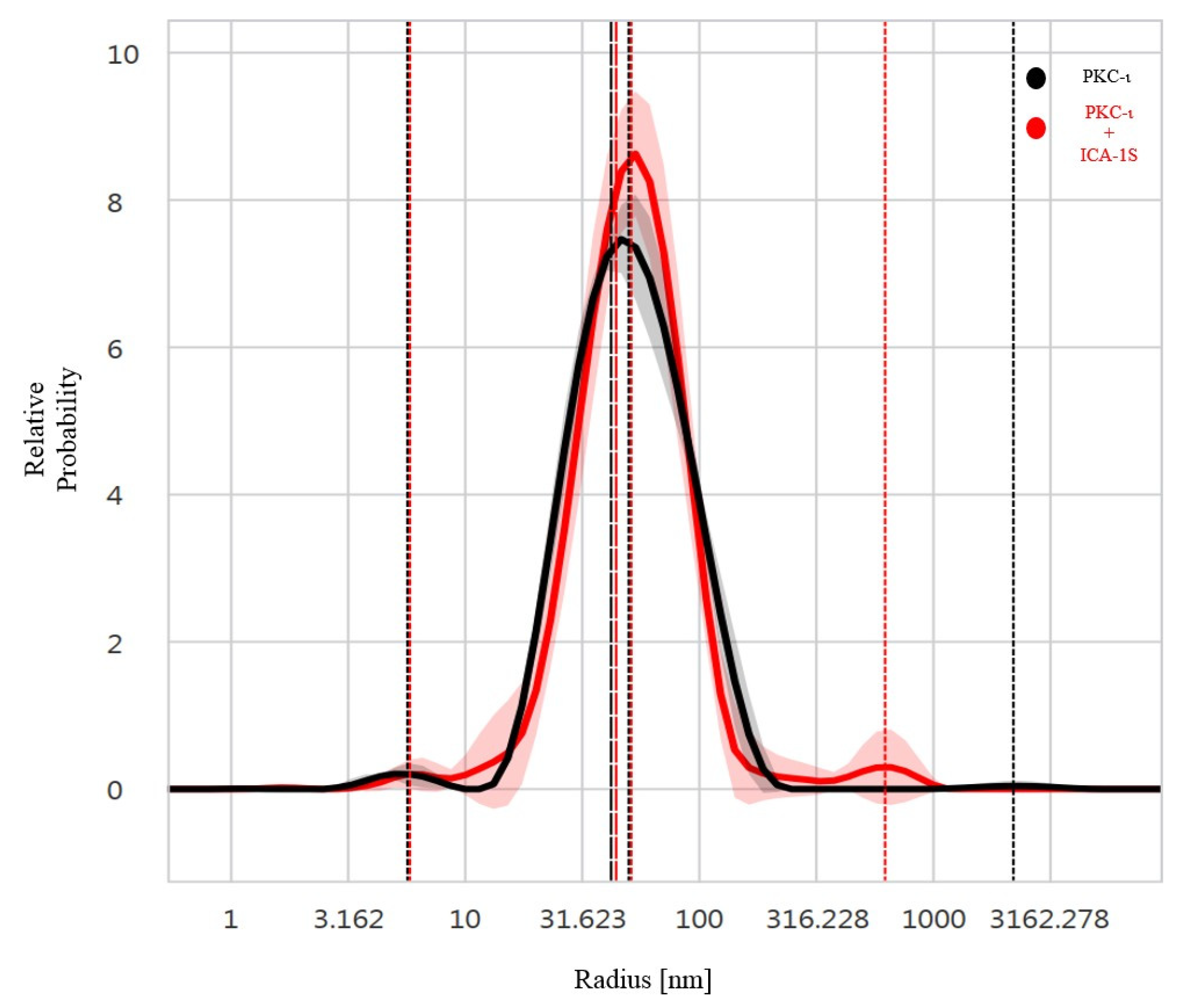

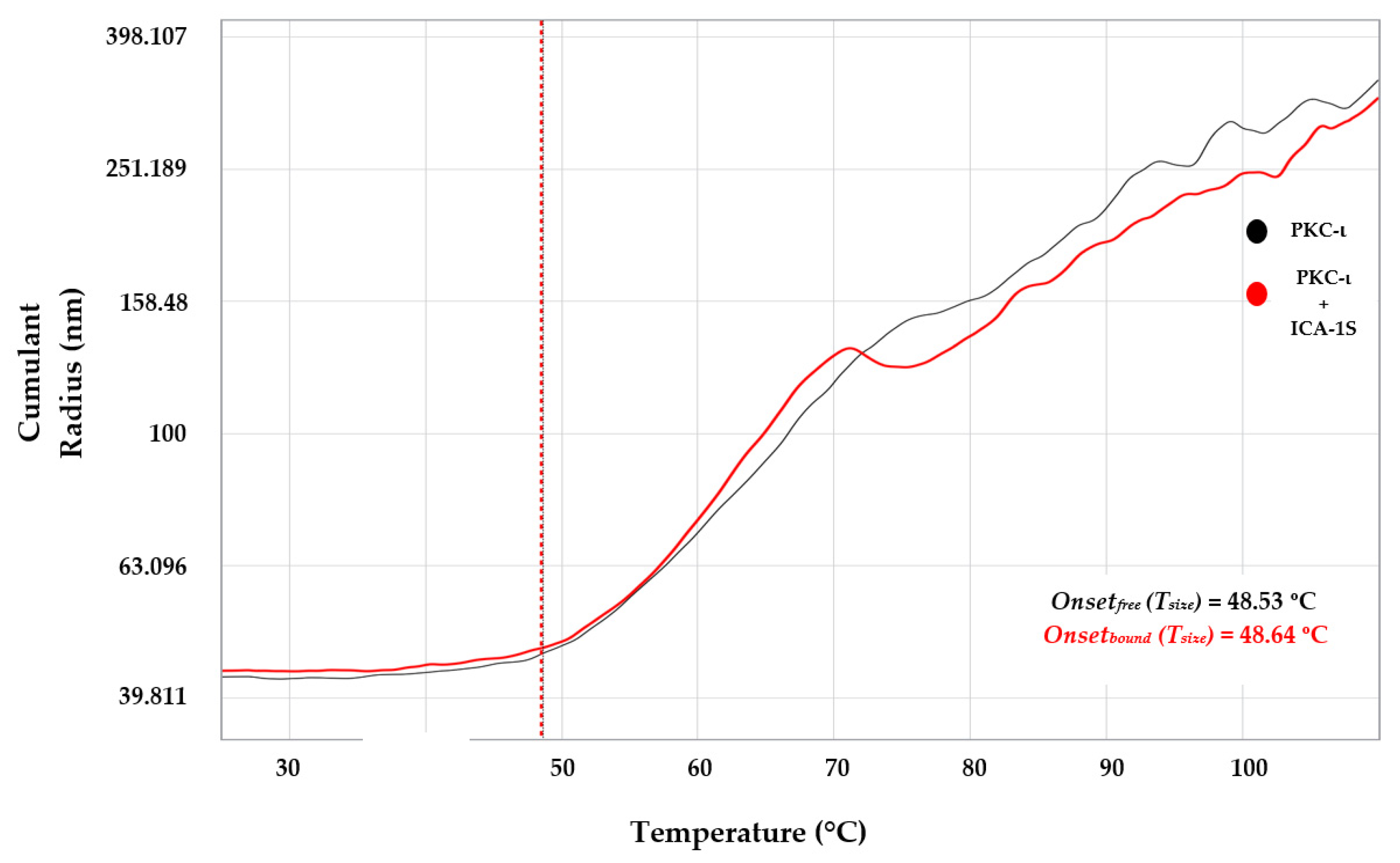

According to the DLS analysis, the PDI of 0.30 ± 0.02 (

Table S1) is close to the monodisperse range (PDI 0.1-0.2). The analysis indicates that the protein size has a hydrodynamic radius of 42.19 ± 0.44nm in the free state and 43.58 ± 0.46 nm in the ICA-1S-bound state. A slight aggregation or oligomerization of the protein may also be present due to the additional peaks observed in the bound state. This observation may result from the addition of ICA-1S, which may cause the aggregate formation as indicated by a minor peak observed in the bound state (

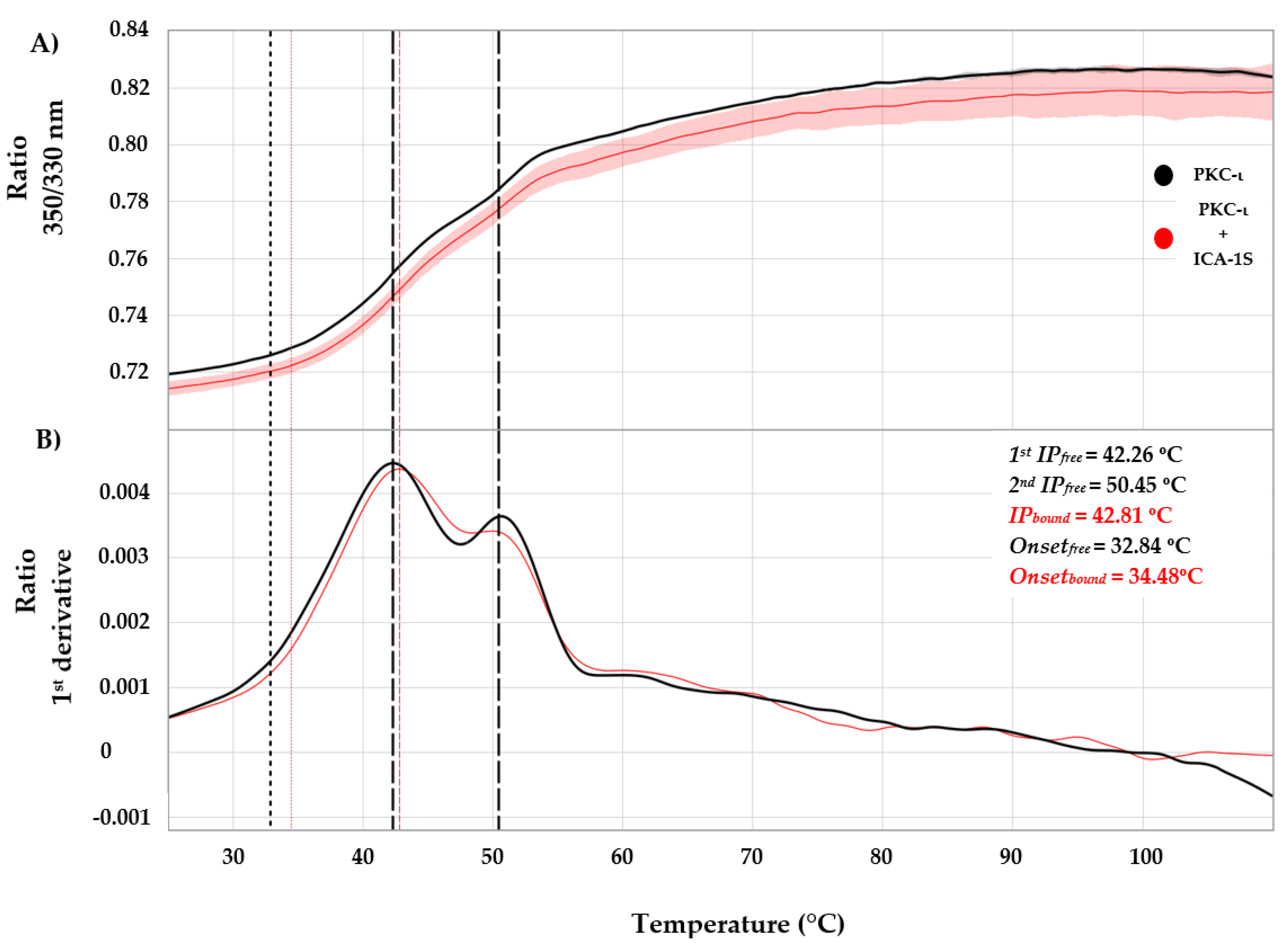

Figure 2, red peak at 626.33 nm). According to NanoTemper Technologies, the PDI value is appropriate for the quantitative DLS analysis, as the higher limit of a sample being inappropriate for DLS analysis is PDI=1.0. In the nanoDSF data analysis of PKC-ι in the presence or absence of ICA-1S interaction, we observe the presence of domain-specific stages in the unfolding profile. Moreover, the protein thermo stability increases due to interaction with ICA-1S as indicated by the derived IP (/

Tm) shifts of 0.55

◦C in the conjugate state (

Figure 3A, 3B). This ligand-induced protein stability in PKC-ι may result from modifications attained in the protein structure. In particular, changes in the binding pocket amino acid residues side chain orientations may contribute to the conformational flexibility of PKC-ι [

26,

28,

40]. In MST analysis, the binding of the low molecular weight ICA-1S/1T to the full-length multi-domain PKC-ι exhibited a change in the thermophoretic property of the protein due to the fluorophore dye labeling (NHS labeling method) without any optimization. Moreover, the PKC-ι concentration was maintained at 30 nM which was sufficient to perform the assays. The initial concentrations ranged from 500

µM (ICA-1T) and 100

µM (ICA-1S) to the 10

−8 M range. The

Kd obtained here for both ligands was under 1 hour of incubation. Further experiments optimized for more extended periods (8 and 24 hours) were also performed, and the effect of the incubation time was observed. However, longer incubation times did not improve (not reported here) the

Kd (s) for the binding interaction between ICA-1S/1T and PKC-ι. MST data reported a direct binding event for both ICA-1S and ICA-1T with the fluorescently labeled PKC-ι. The PKC-ι and ICA-1S complex exhibited a tighter binding (

Kd = 9.14

± 0.19

µM) compared to PKC-ι and ICA-1T (

Kd = 173

± 2.32

µM), as indicated by their dissociation constants.

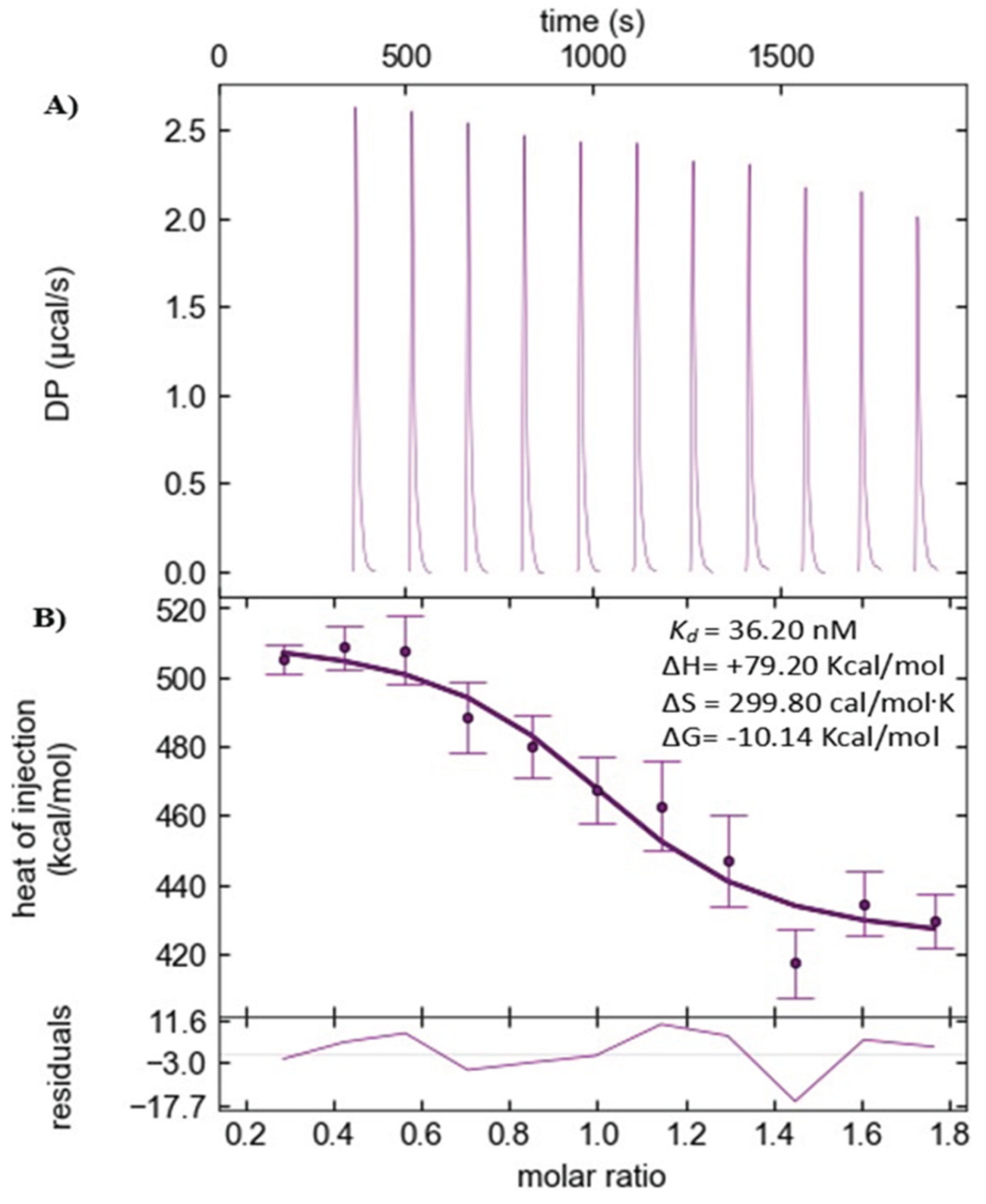

The thermodynamics data obtained from ITC indicate a binding event in an endothermic manner during the calorimetric titrations. The reactions were found to be spontaneous, as indicated by negative free energy differences (∆G = -10.14 Kcal/mol), while the

Kd was found to be in the nM range (36.20 nM). The data indicate that the binding event falls within the strong to moderate range, as per Malvern Panalytical (manufacturer of PEAQ-ITC). [

35,

41]. The initial water-water and ligand-buffer control experiments showed no binding event, confirming that the actual protein-ligand binding event was free from any influence of heat, dilution, or buffer mismatch. The binding equilibrium was achieved, as indicated by the inverse sigmoidal shape of the heat of injection vs. molar ratio plot (

Figure 9B). In addition, the calculated thermodynamic data from the 20

µM PKC-ι and 2

µM ICA-1S ITC experiment exhibit a positive entropic gain of +299.80 cal/mol.K, indicating a possible entropy-driven hydrophobic interaction in the binding pocket. Moreover, a significant positive enthalpy (+79.20 Kcal/mol) contribution, which may consist of heat changes due to conformational changes (∆H

conformation), water displacement from the protein surface (∆H

solvation) and a simultaneous noncovalent hydrogen bond and/or Van Der Waals interactions among the interacting molecules (∆H

interaction) [

38,

42]. It is worth mentioning that the conformational change was also implied by the observation from nanoDSF and DLS experiments, which are in agreement with ITC.

The Kd value determined from ITC is much lower than that determined by MST. These differences might arise due to PKC-ι being labeled with red NHS dye, which covalently binds with the lysine residue of the protein (considering no lysine residue in the ligand binding site). In contrast, protein and ligand remain in identical physiological conditions in ITC. Regardless, the MST-derived affinity constants indicate that the functional group differences from ‘methyl dihydrogenphosphate’ (ICA-1T) to ‘hydroxymethyl’ (ICA-1S) in the ‘cyclopentyl’ moiety resulted in a stronger binding affinity (approximately 18-fold) to PKC-ι. This key information on the chemical structure of these PKC-ι specific inhibitors will be further explored for derivatization to create the next generation of ICA-1S/1T analogs. We aim to explore, in particular, the analogs with long-chain alkyl dihydrogenphosphate, alkyl carboxylic acid and alkyl sulfonic acid functional groups. These analogs are being synthesized in collaboration and will be studied in future. Therefore, for rational drug design, these derivatives of ICA-1S/1T may open a new avenue of structure-activity relationship (SAR) study and enhance our understanding of these inhibitors.