Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data & Methods

3.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

3.1.1. Resident Population Data for Cities During 2004-2019

3.1.2. 280 Cities and 19 Industries

| Variable | Variable Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Employment in China | The employment of 19 industries in prefecture-level and above cities, annual data during 2004-2019, from “China City Statistical Yearbook”, 10 thousands people. | https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2025020156&pinyinCode=YZGCA |

| GRP, GRP (per capita) in China | The gross regional product and gross regional product per capita in prefecture-level and above cities of China, the annual data during 2004-2012 and 2014-2019 are from “China City Statistical Yearbook”, and the annual data in 2013 is from “China Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook”, yuan. | https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2025020156&pinyinCode=YZGCA; https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2015070200&pinyinCode=YZXDR |

| Sales of commodities in China | Total retail sales of consumer goods + total sales of commodities of enterprises above designated size in wholesale and retail trades prefecture-level and above cities of China, annual data in 2019, from “China City Statistical Yearbook”, 10 000 yuan. | https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2025020156&pinyinCode=YZGCA |

| GDP (per capita) in the United States | CAGDP1 gross domestic product (GDP) summary by metropolitan area, from U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, annual data during 2004-2019, thousands of chained 2012 dollars. | https://www.bea.gov/data/gdp/gdp-county-metro-and-other-areas |

| Polulation in the United States | Annual estimates of the resident population for metropolitan statistical areas in the United States, from U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, annual data in 2019, people. | https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-total-metro-and-micro-statistical-areas.html |

| Sales of commodities in the United States | Real personal consumption expenditures by States, real personal income by metropolitan area, annual data in 2019, from U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, millions of constant (2012) dollars. | https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-12/rpp1221.xlsx |

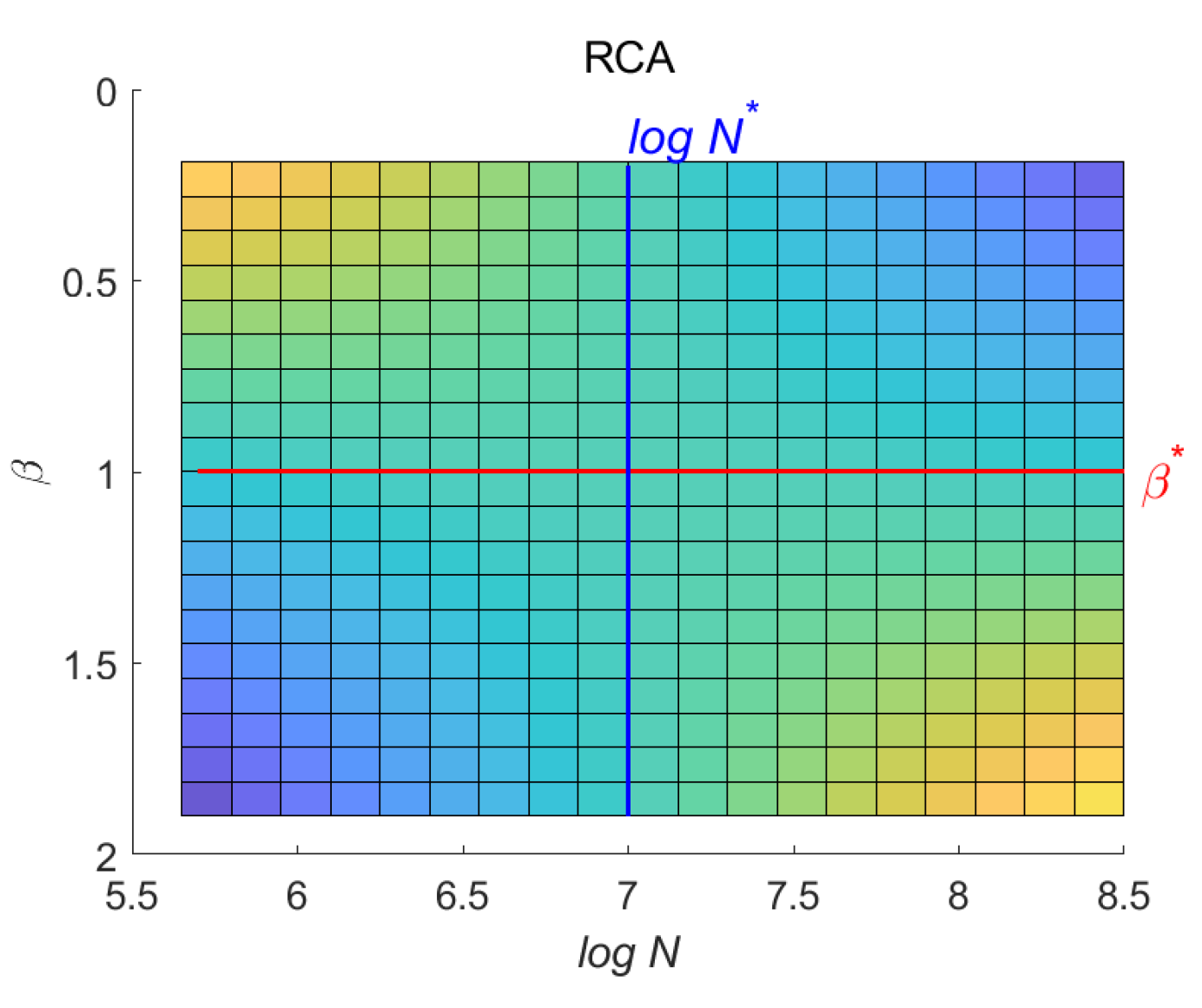

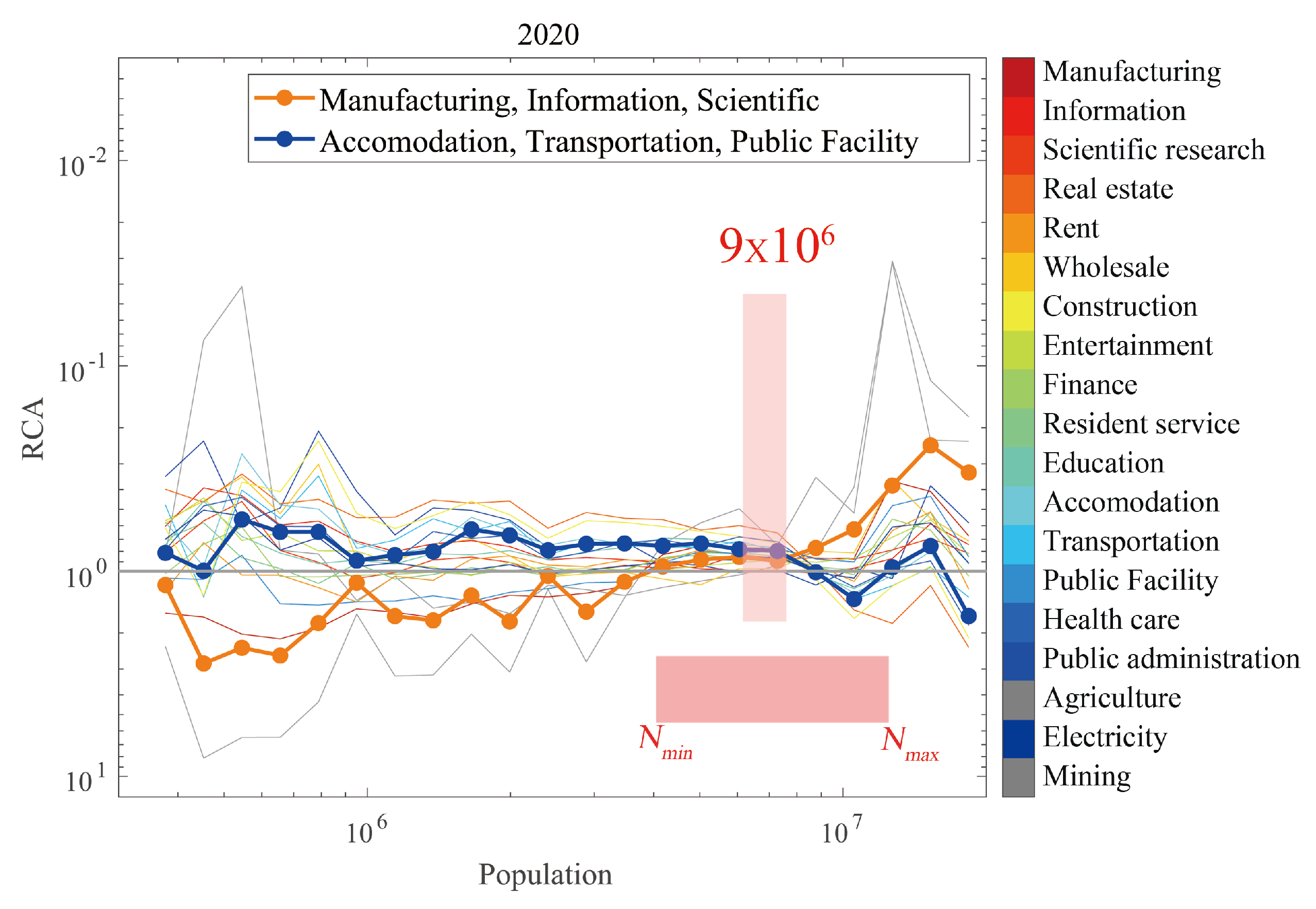

3.2. The Comparative Advantage of Industries and Its Critical Point Analysis

4. Results

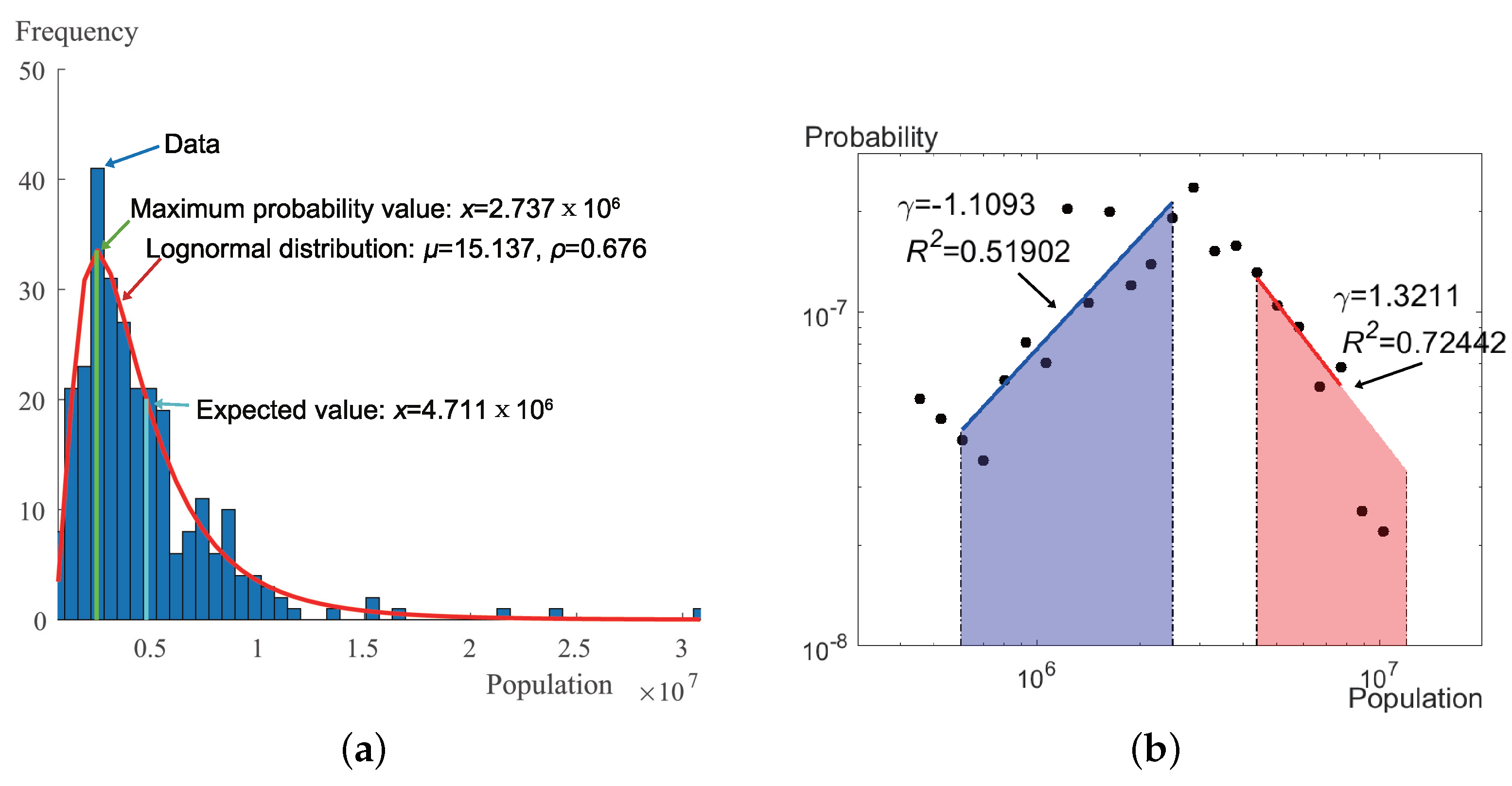

4.1. The Distribution and Evolution of Scale Characteristics

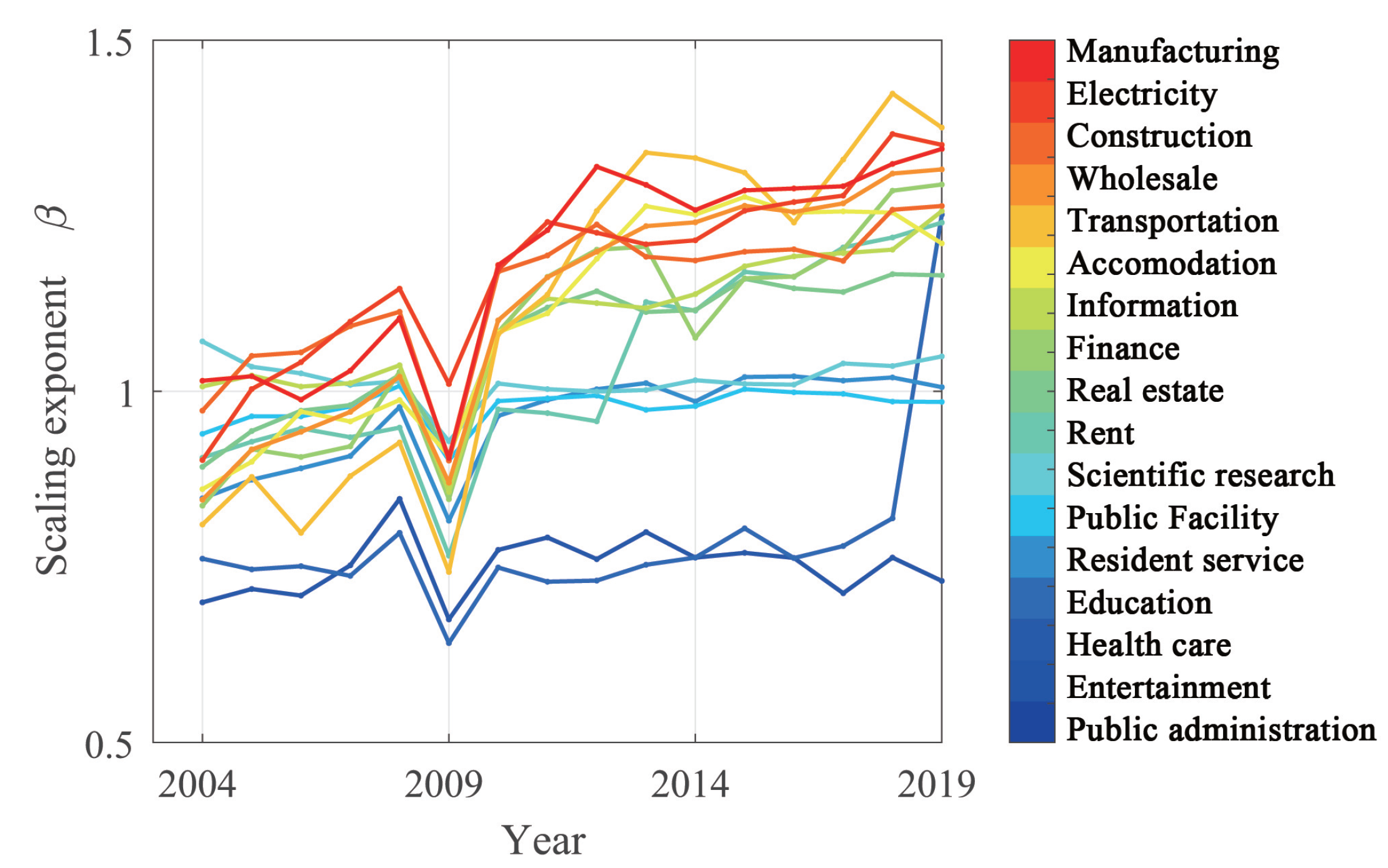

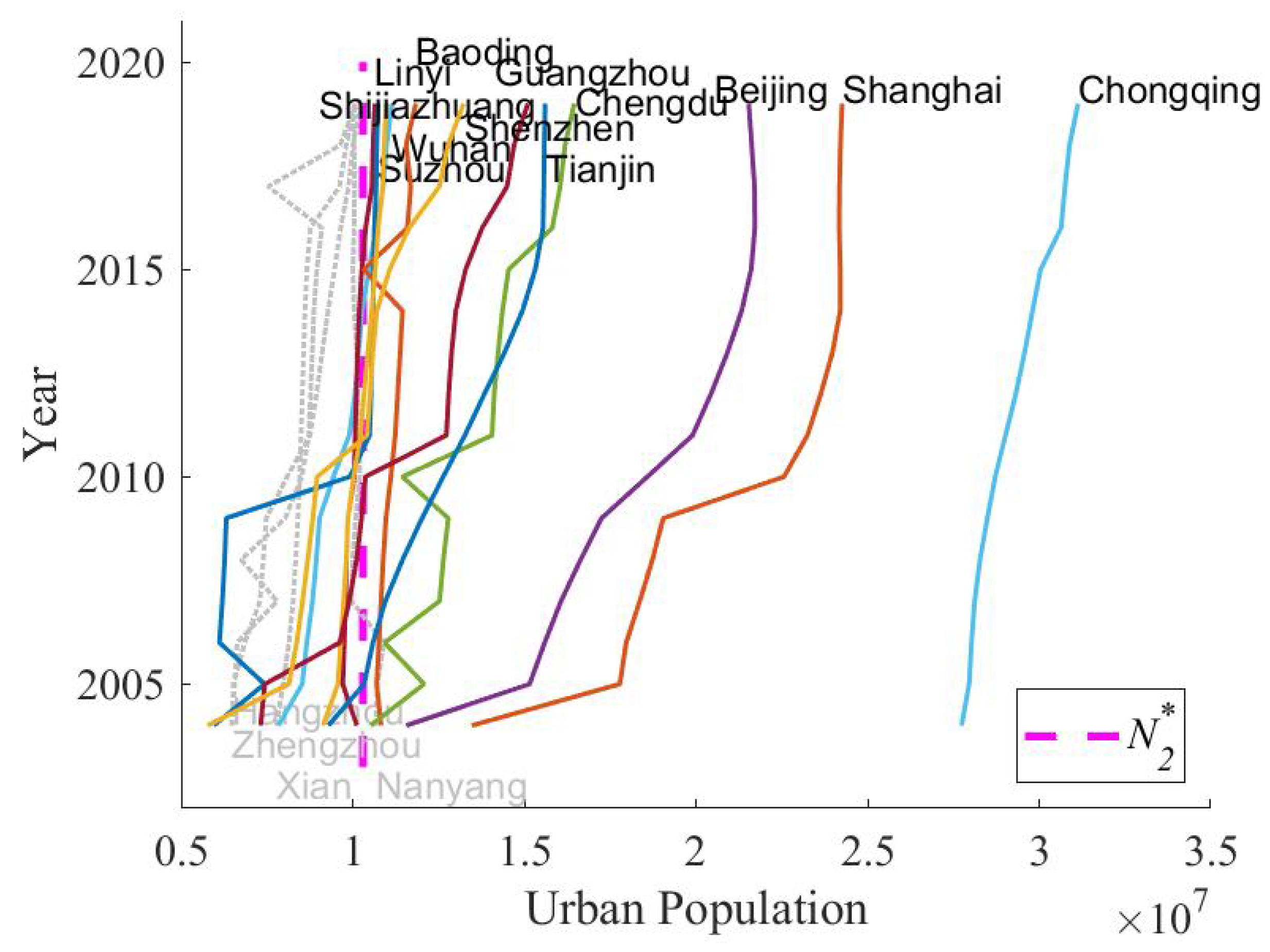

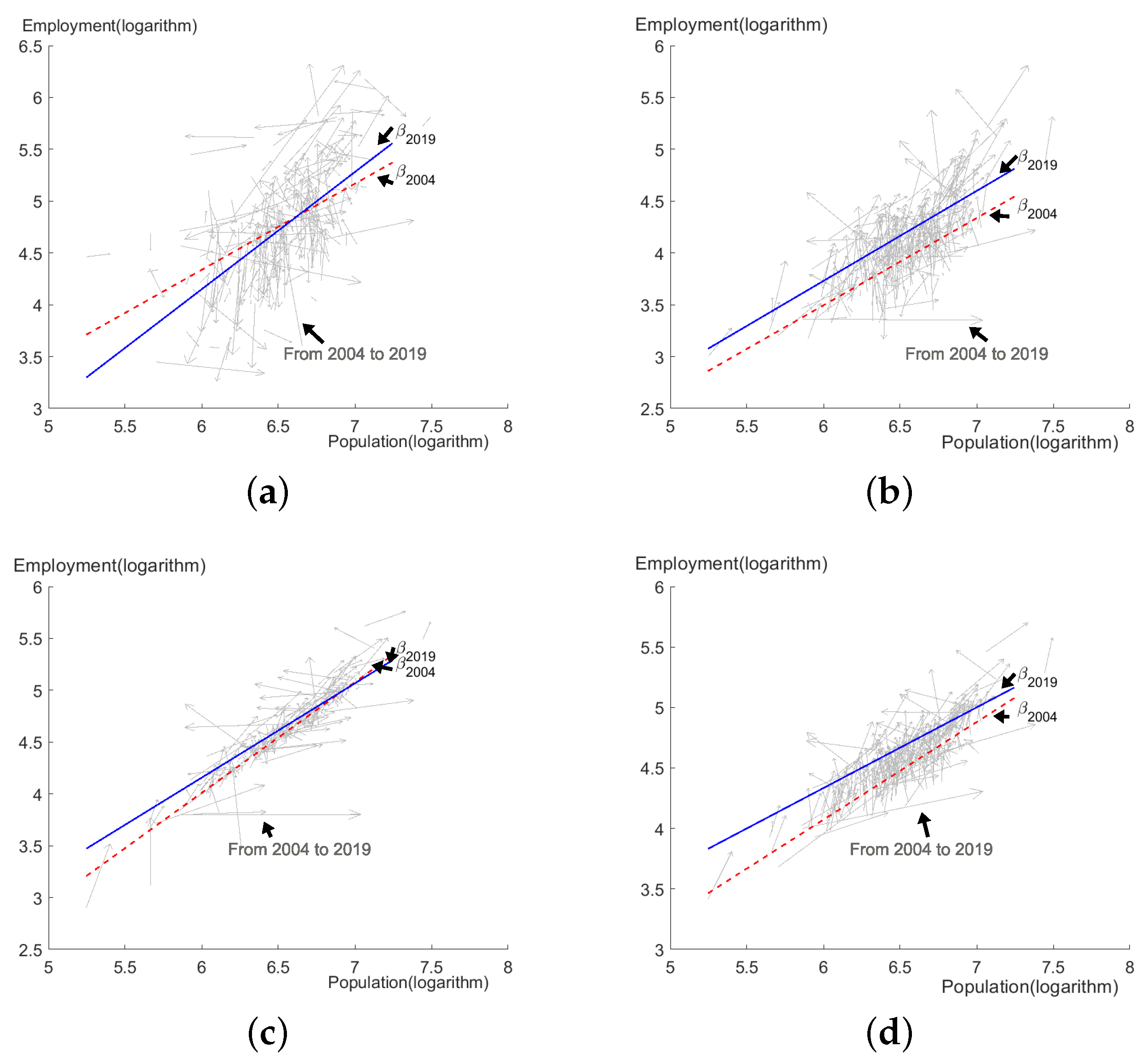

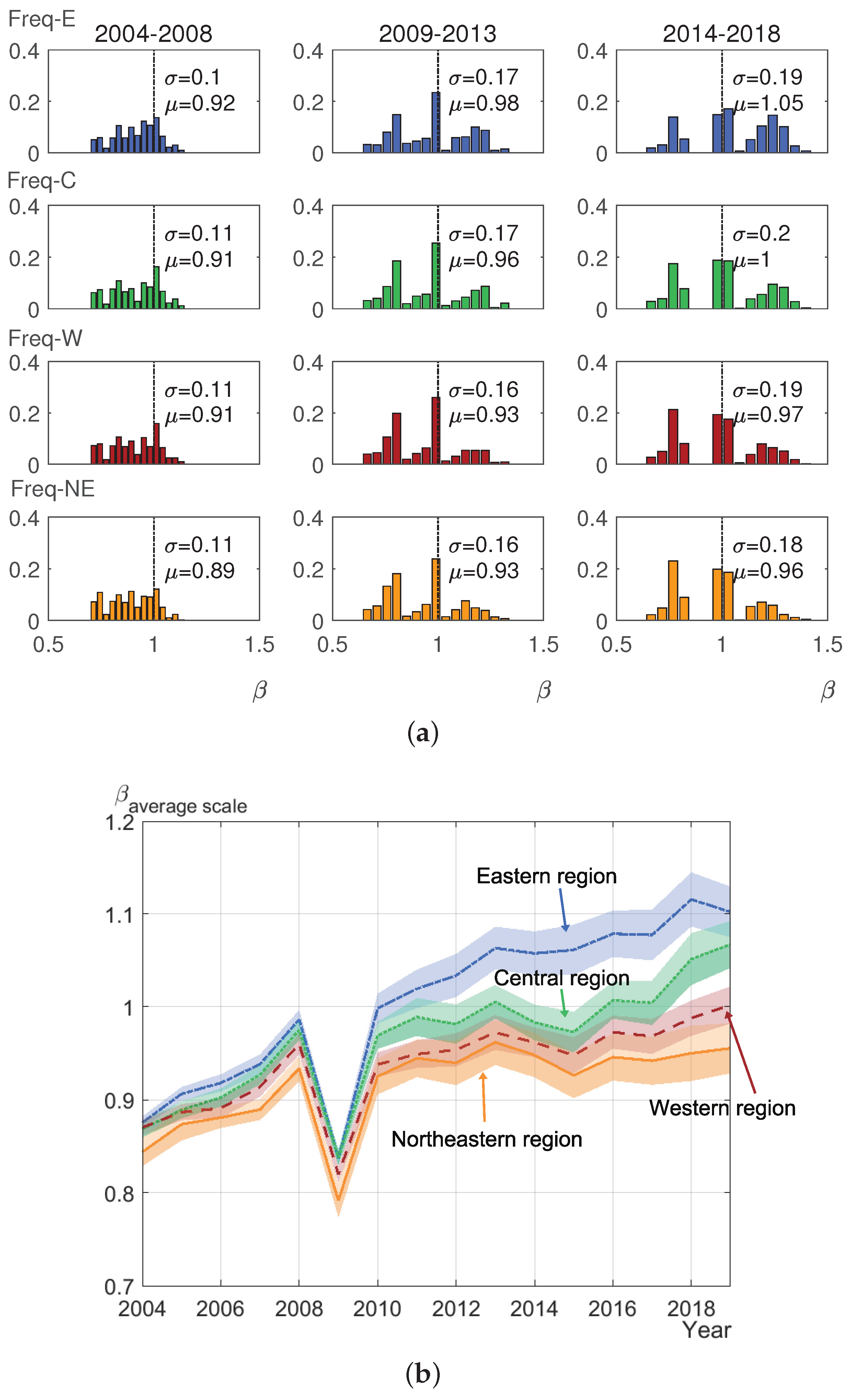

4.1.1. Evolution of Scale Characteristics

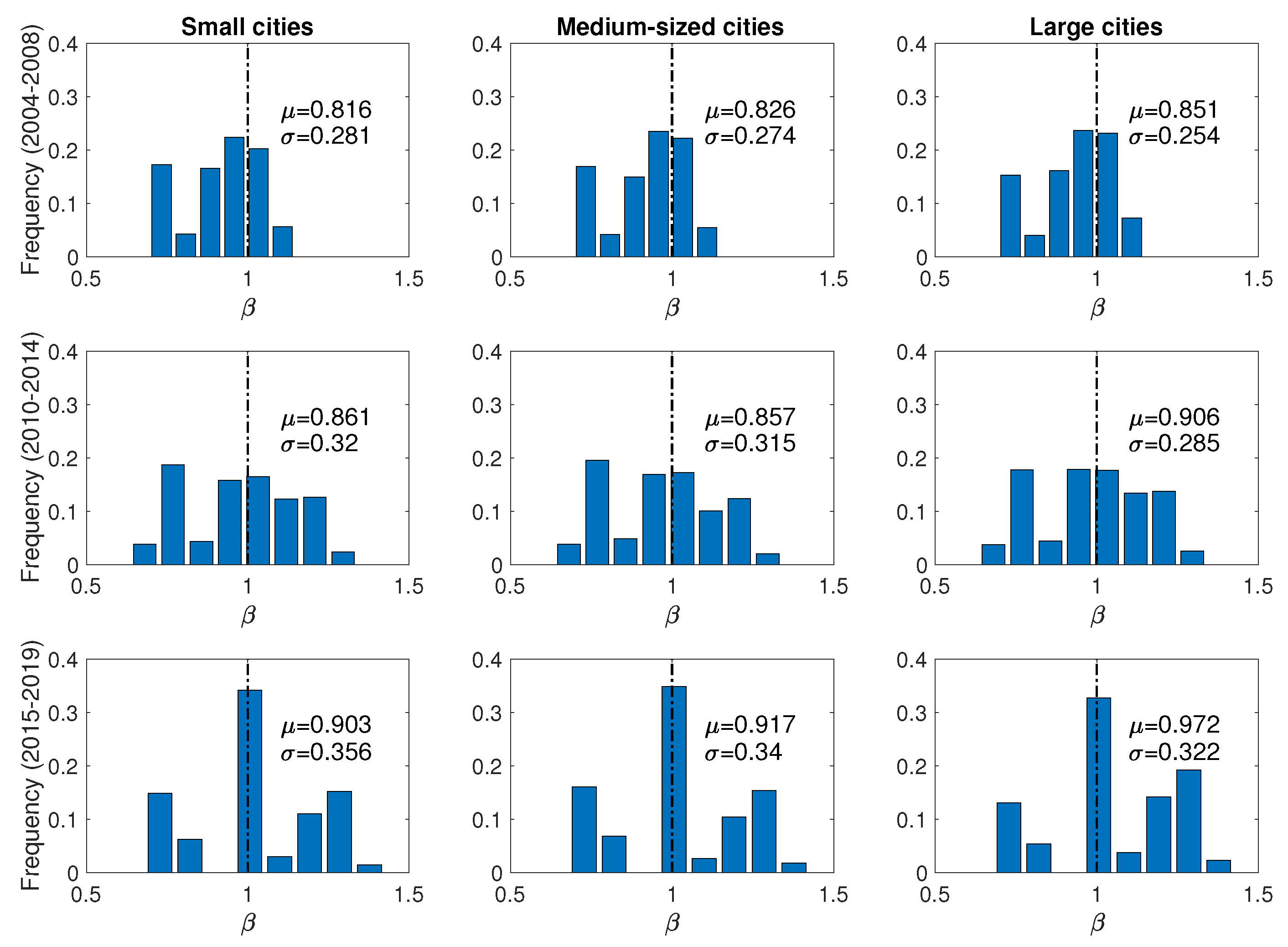

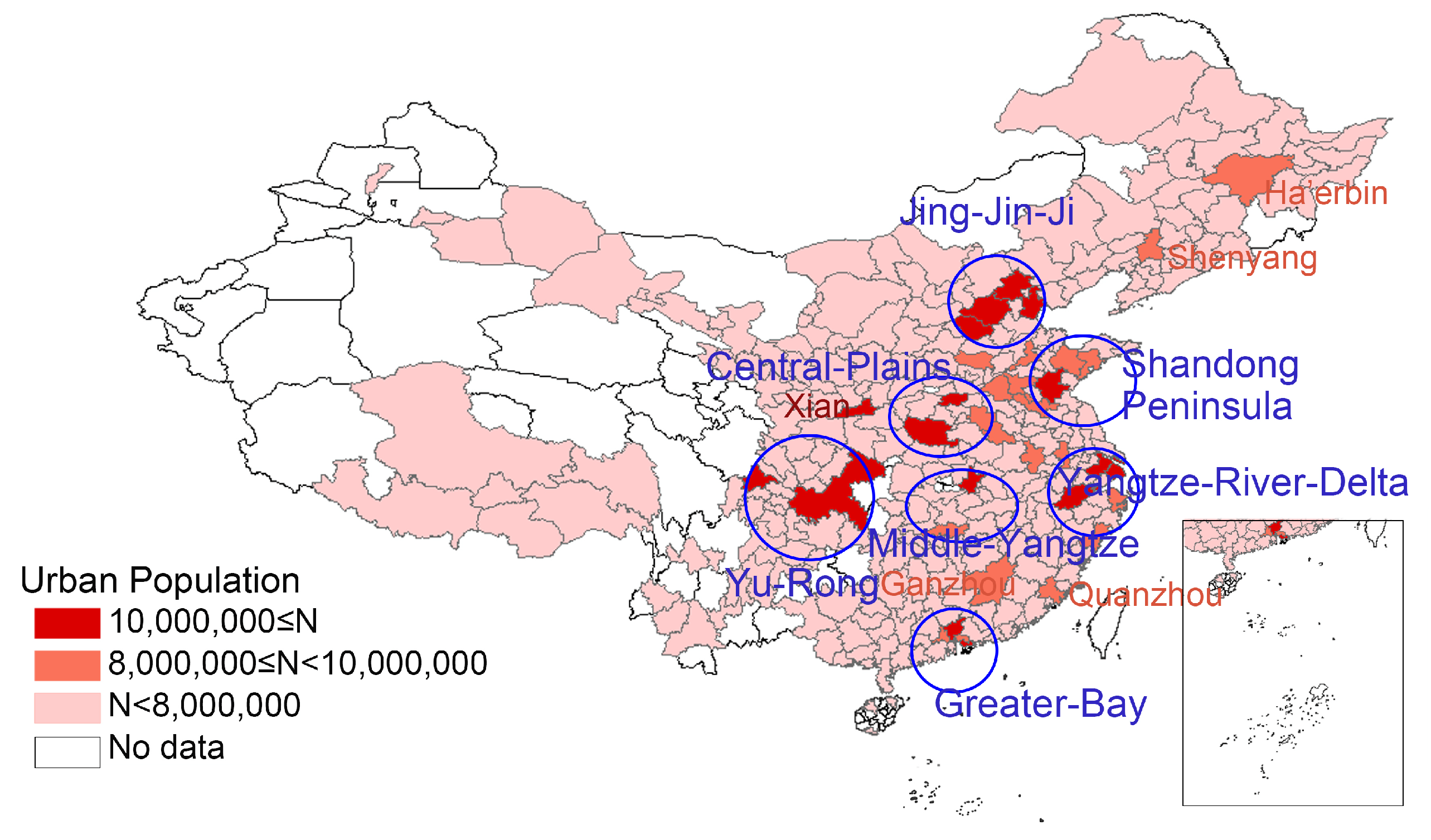

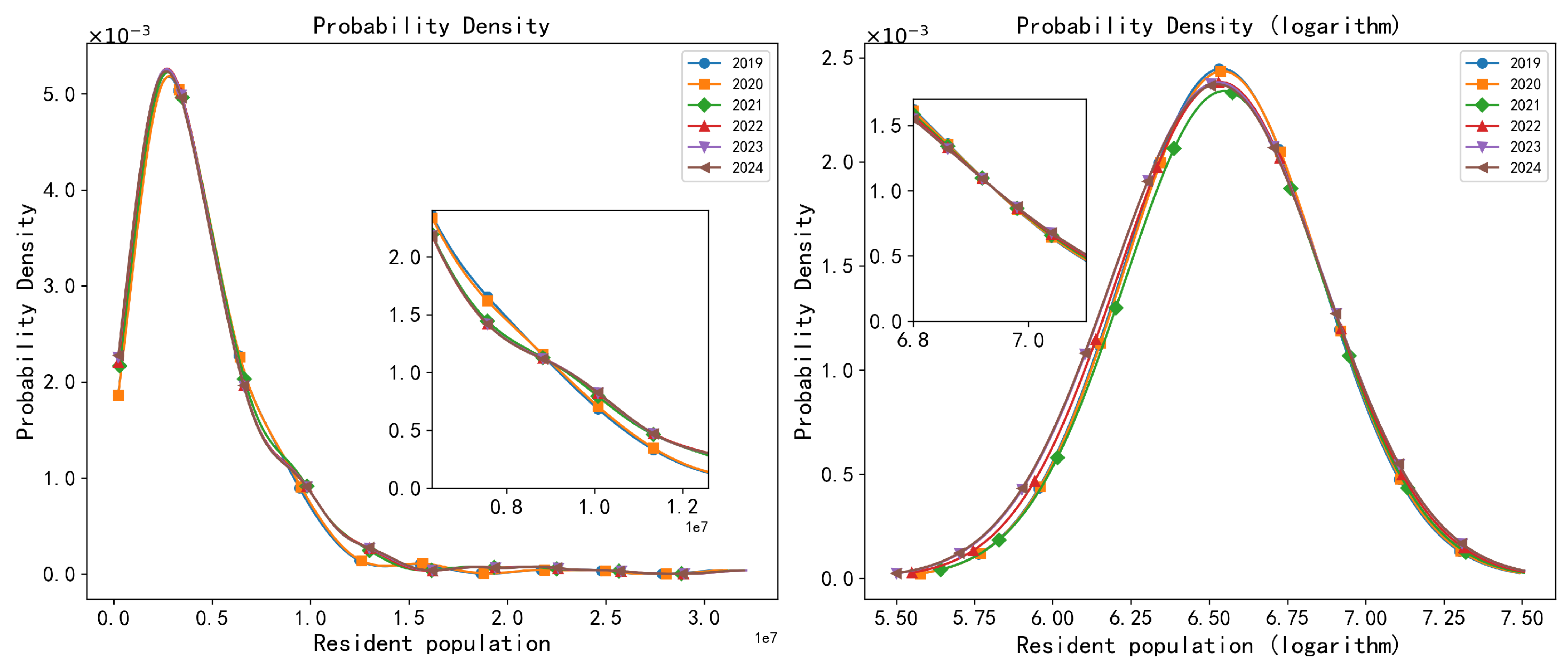

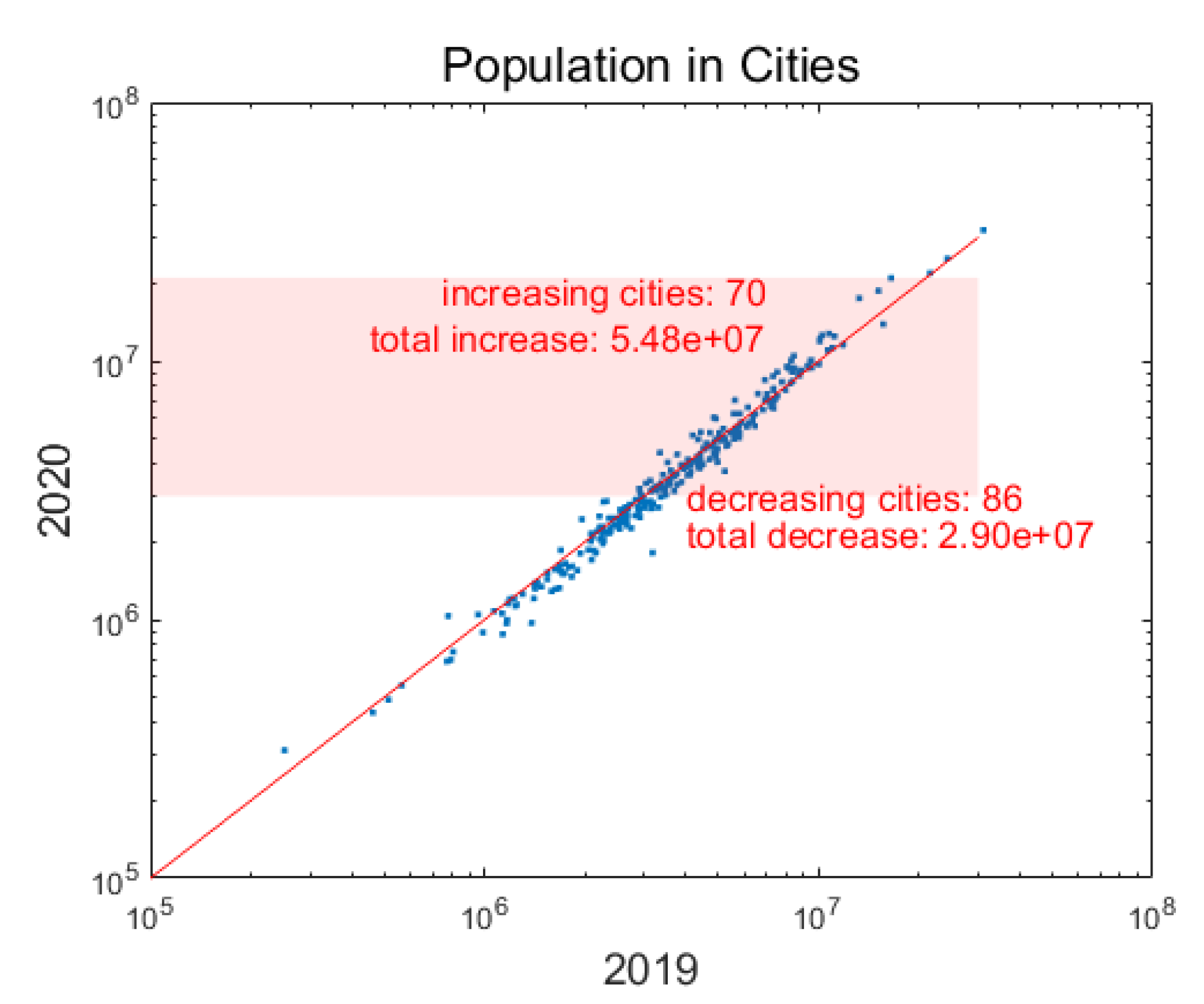

4.1.2. Distribution of Scale Characteristics in Different Cities

4.2. Labor Demand of “Knowledge-Spillover” Development

4.2.1. Evolution of Knowledge Spillover Industries

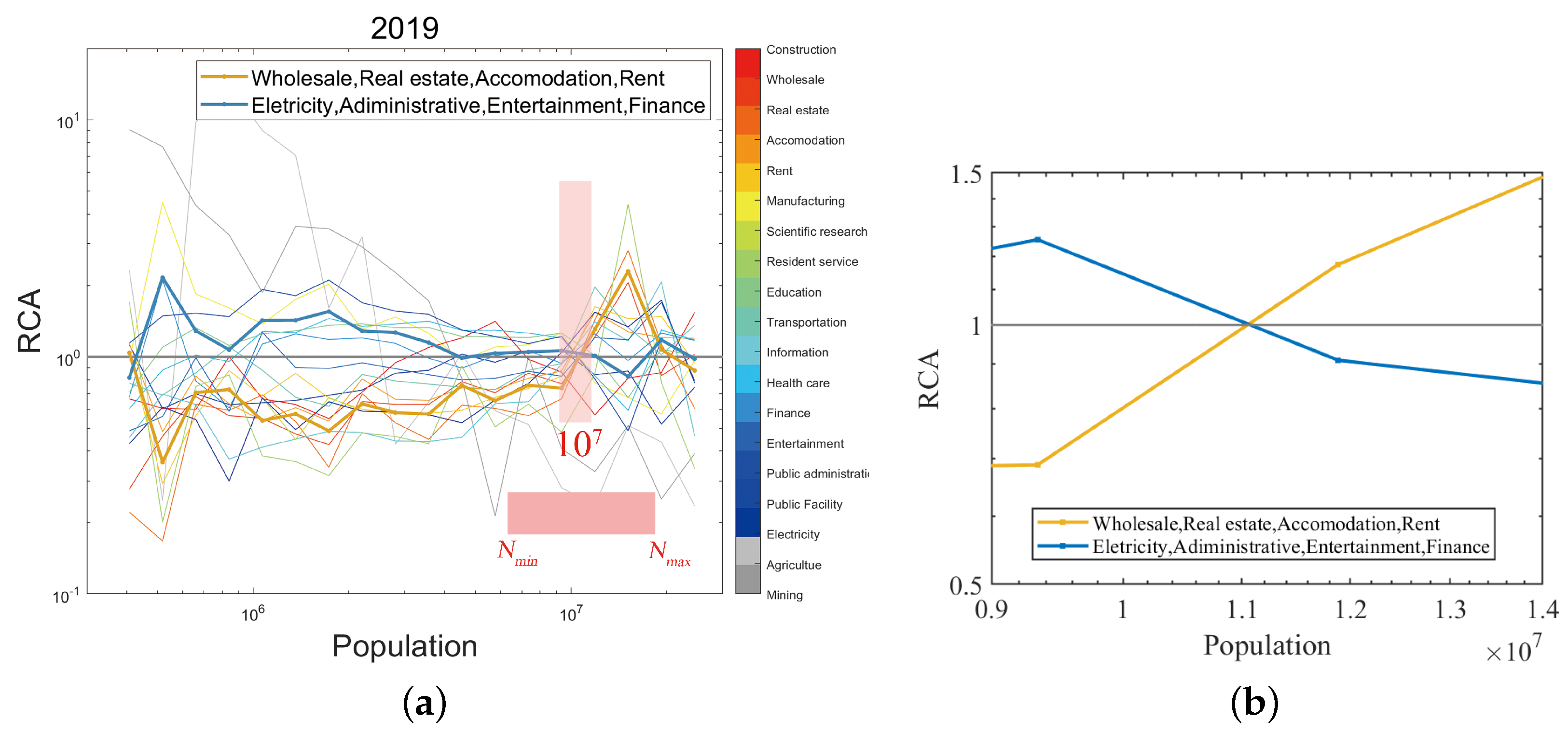

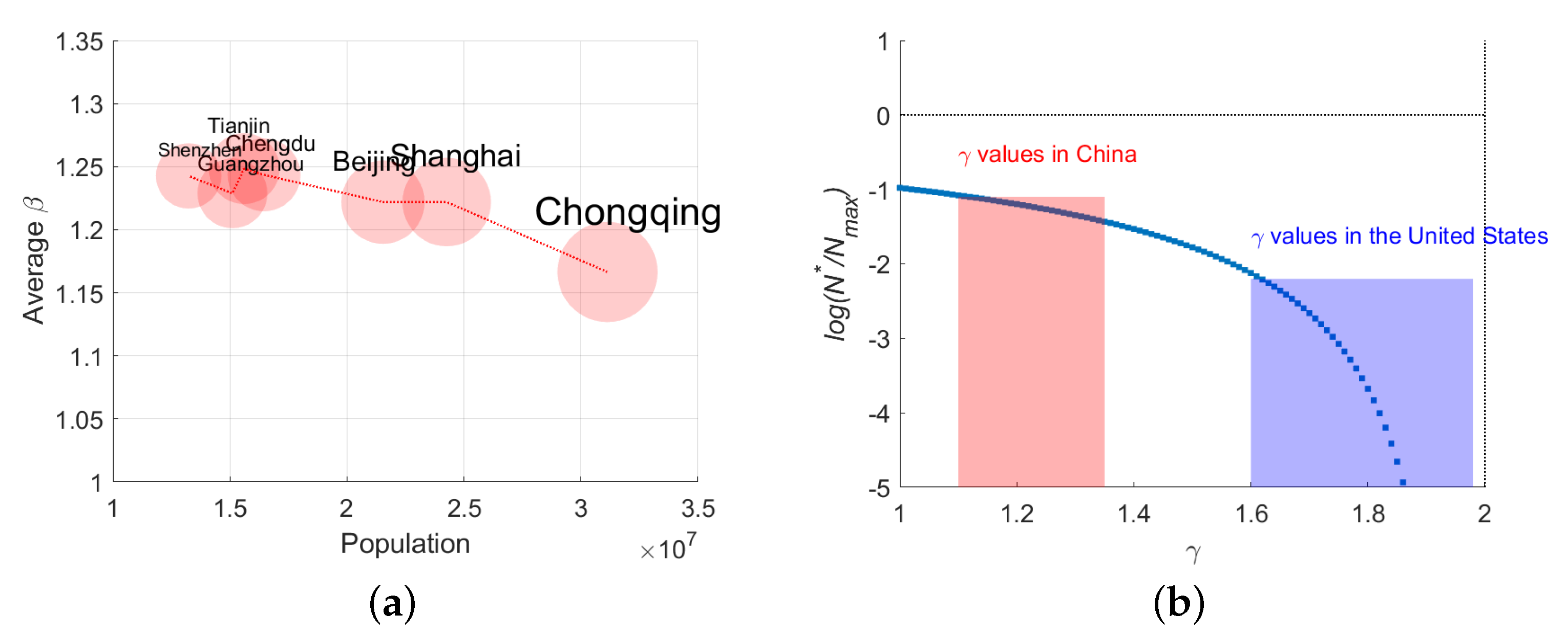

4.2.2. Comparison with the Optimal City Size Model

4.2.3. The Limitations of Urban Innovation in China

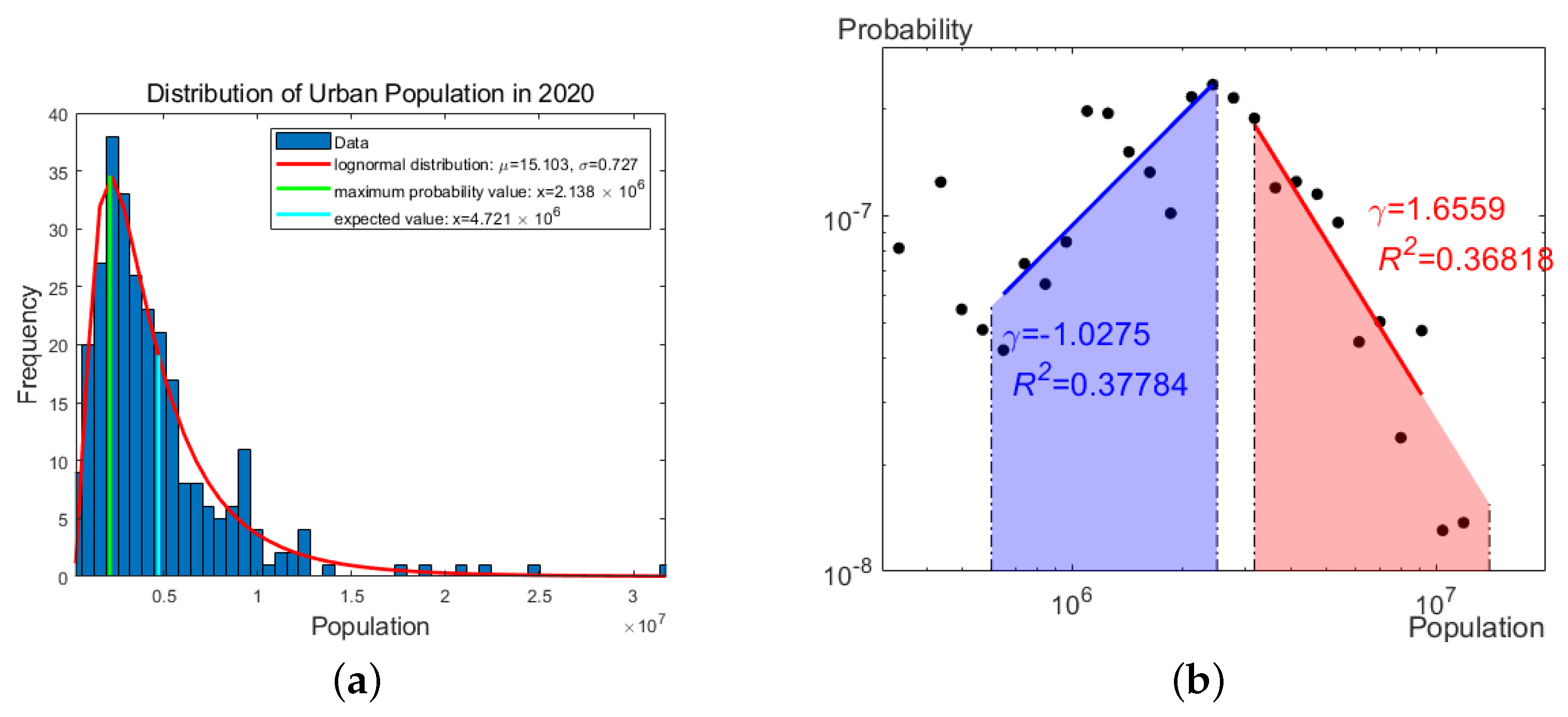

4.2.4. Influence of Population Distribution Characteristics

5. Conclusion & Suggestions

1. The Comparative Advantage of “Knowledge-Spillover” Industries Requires a Critical Urban Population Size

2. The Critical Population Size of 10 Million for China

3. Future Prospects for China

Appendices

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Source and Statistical Analysis

Appendix A.1. Cities & Industries

Appendix A.1.1. The Cities in China

Appendix A.1.2. Municipalities and Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix A.1.3. 19 Industries

Appendix A.2. Data Source

Appendix A.2.1. Explanation on the Time Interval of Data

Appendix A.2.2. Data Interpolation Method

Appendix A.2.3. Logarithmic Linear Correlation of Population and Employment in Specific Industries.

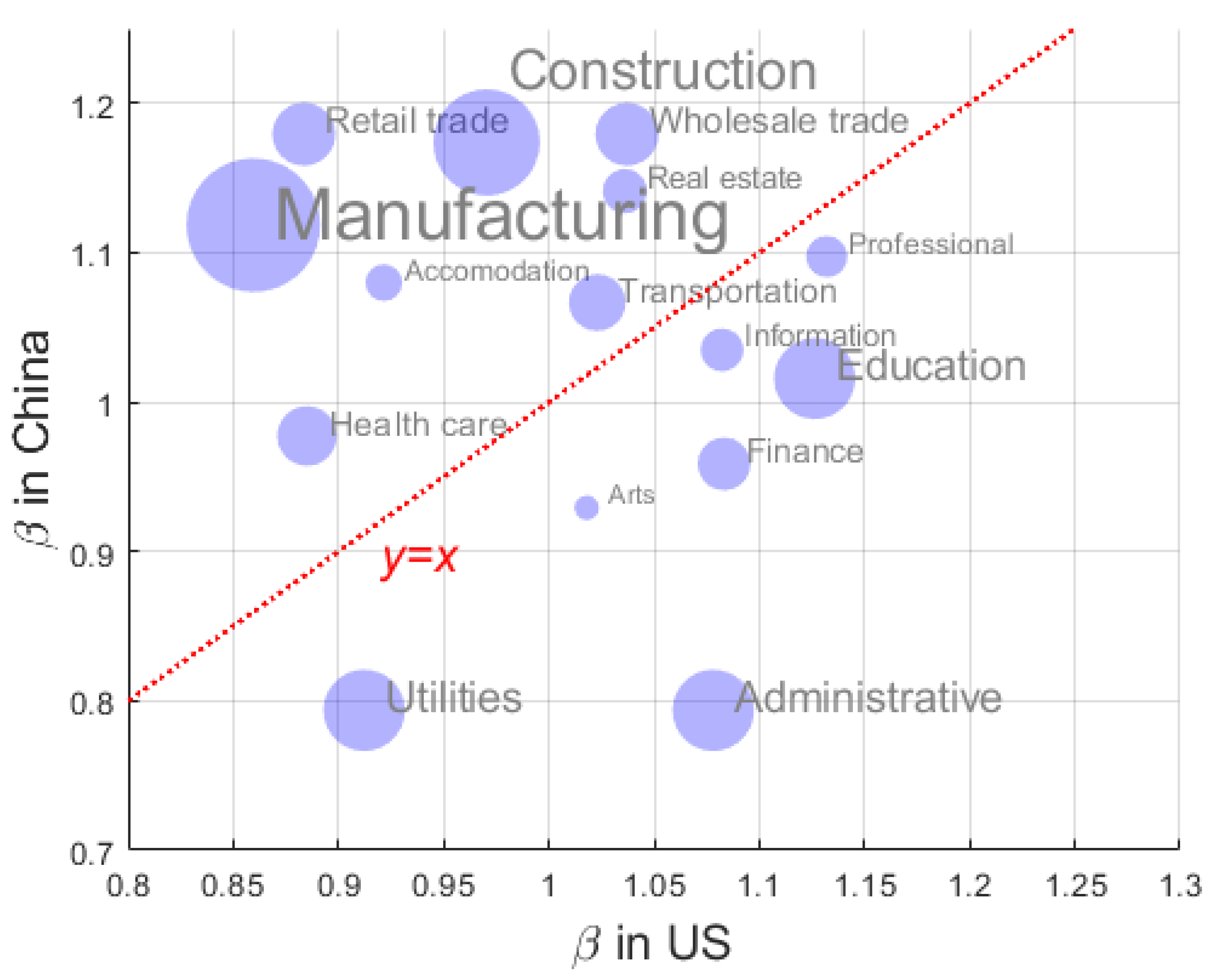

Appendix A.2.4. The Different β i for China and the United States

Appendix B. The Theoretical Model and Derivation Process

Appendix B.1. The Scaling Laws for Cities

| Industry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Mining | 0.09 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.85 |

| Manufacturing | 1.32 ** | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.00 |

| Production and supply of electricity,heating, gas,and water | 0.73 ** | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.00 |

| Construction industry | 1.35 ** | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.00 |

| Wholesale and retail | 1.35 ** | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.00 |

| Transportation, warehousing, and postal services | 1.16 ** | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.00 |

| Accommodation and catering industry | 1.29 ** | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.00 |

| Information transmission, computing and services, and software | 1.24 ** | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.00 |

| Finance | 1.01 ** | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.00 |

| Real estate industry | 1.26 ** | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.00 |

| Rent | 1.21 ** | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.00 |

| Scientific research, technical services and geological survey | 1.26 ** | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| Public facilities management industry | 1.25 ** | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| Residential services, repair and other services | 1.38 ** | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.00 |

| Educational Services | 1.05 ** | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.00 |

| Health care and social work | 0.98 ** | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.00 |

| Culture, sports and entertainment | 1.03 ** | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.00 |

| Public administration, social security and social organization | 0.76 ** | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 |

| ** indicates the significant industries every year at the 95% confidence level. | ||||

| : p-value for the regression coefficient. | ||||

| : p-value from the F-test, indicating the overall significance of the regression model. | ||||

| Source: Data from the “China City Statistical Yearbook” (2004-2019). | ||||

Appendix B.2. The Comparative Advantage Function

Appendix B.3. Changes in Comparative Advantage

- Changes with N.when , ; , ; and , .

-

Changes with ..In 2019,, , , when , . When , ; , ; , ., , , when , . When , ; , ; , .

Appendix C. Other Results

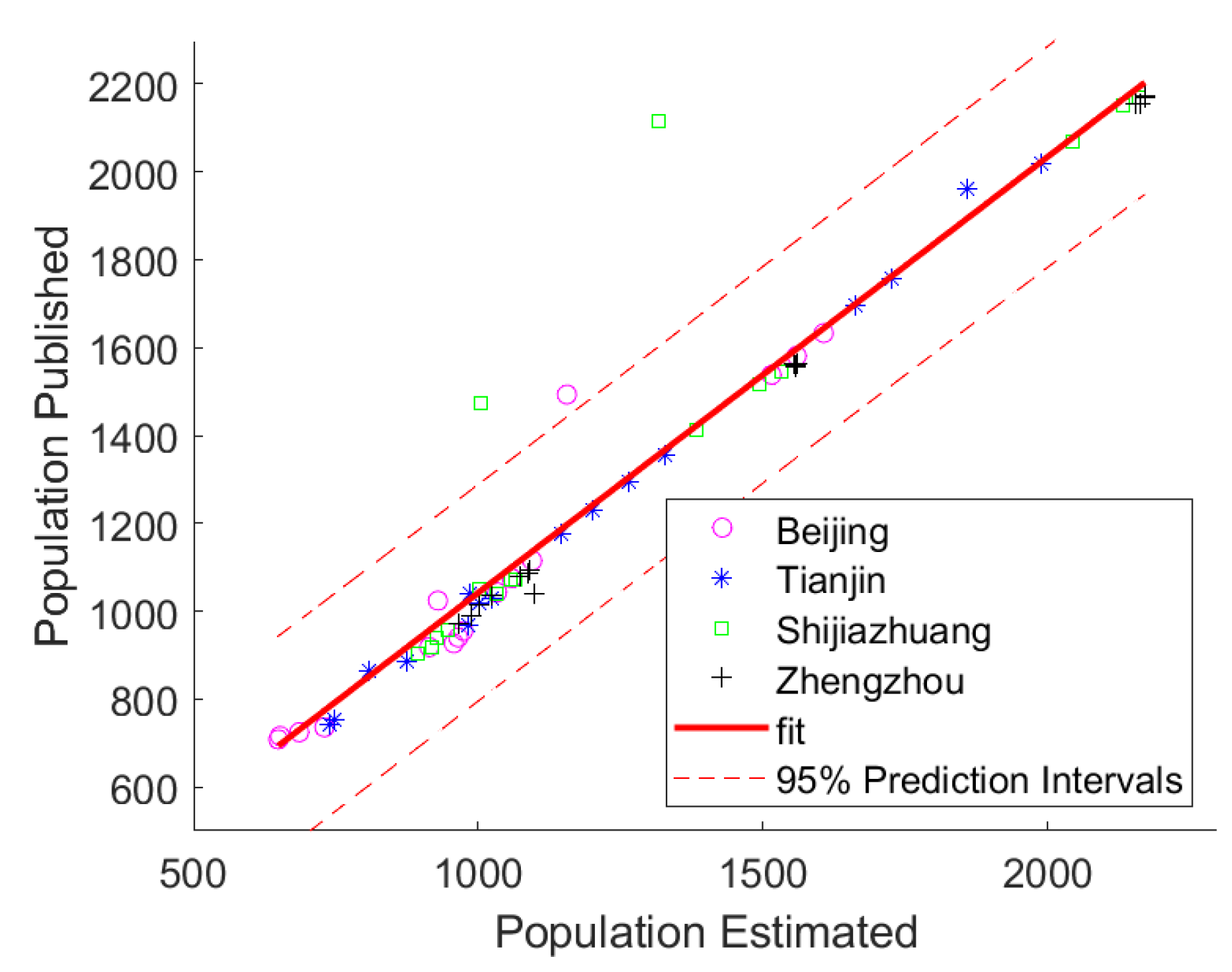

Appendix C.1. The Derivation Process on 2020 Data

Appendix C.2. Labor Demand of “Knowledge-Spillover” Cities in China

| Year | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | ||

| 2005 | ||

| 2006 | ||

| 2007 | ||

| 2008 | ||

| 2009 | ||

| 2010 | ||

| 2011 | ||

| 2012 | ||

| 2013 | ||

| 2014 | ||

| 2015 | ||

| 2016 | ||

| 2017 | ||

| 2018 | ||

| 2019 | ||

| 2020 |

Appendix C.3. Comparison with the Optimal City Size

| a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 245.471 | 0.1064 | 0.3528 | 1.13E+07 |

| United States | 131.978 | 0.0994 | 0.3393 | 1.22E+06 |

Appendix C.4. Differences in Cities’ Economic Regions

| Region | Provinces |

|---|---|

| Eastern Region | Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, Hainan, Taiwan, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR |

| Central Region | Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan |

| Western Region | Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Chongqing Municipality, Sichuan , Guizhou , Yunnan, Tibet Autonomous Region, Shaanxi, Gansu , Qinghai , Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region |

| Northeast Region | Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang |

| Classification based on the standards of the National Bureau of Statistics of China. | |

Appendix C.5. The Recapitulation of Industries

| Industry | Score |

|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 0.75 * |

| Production and supply of electricity, heating, gas, and water | 0.93 * |

| Construction industry | 0.42 |

| Wholesale and retail | 0.68 * |

| Transportation, warehousing, and postal services | 0.83 * |

| Accommodation and catering industry | 0.85 * |

| Information transmission, computing services, and software | 0.67 * |

| Finance | 0.61 * |

| Real estate industry | 0.91 * |

| Rent | 0.83 * |

| Scientific research, technical services, and geological survey | 0.77 * |

| Public facilities management industry | -0.91 |

| Residential services, repair, and other services | 0.73 * |

| Educational services | 0.83 * |

| Health care and social work | 0.42 |

| Culture, sports, and entertainment | 0.82 * |

| Public administration, social security, and social organization | 0.60 * |

| * indicates the industries with . |

References

- Bettencourt, L.M.; West, G. A unified theory of urban living. Nature 2010, 467, 912–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W. The global pattern of urbanization and economic growth: evidence from the last three decades. PloS One 2014, 9, e103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN, D. World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision. United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA 2015, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Balland, P.A.; Jara-Figueroa, C.; Petralia, S.G.; Steijn, M.P.; Rigby, D.L.; Hidalgo, C.A. Complex economic activities concentrate in large cities. Nature Human Behaviour 2020, 4, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jiao, M. City size, industrial structure and urbanization quality—A case study of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Du, R. How does urban agglomeration integration promote entrepreneurship in China? Evidence from regional human capital spillovers and market integration. Cities 2020, 97, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.; Frank, M.R.; Rahwan, I.; Jung, W.S.; Youn, H. The universal pathway to innovative urban economies. Science Advances 2020, 6, eaba4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.M.; Lobo, J.; Helbing, D.; Kühnert, C.; West, G.B. Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 7301–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.M. The Origins of Scaling in Cities. Science 2013, 340, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.M.; Lobo, J.; West, G.B. Why are large cities faster? Universal scaling and self-similarity in urban organization and dynamics. The European Physical Journal B 2008, 63, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumain, D.; Paulus, F.; Vacchiani-Marcuzzo, C.; Lobo, J. An evolutionary theory for interpreting urban scaling laws. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography 2006, 2006, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Bettencourt, L.; Lobo, J.; Strumsky, D.; Samaniego, H.; West, G. Scaling and universality in urban economic diversification. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2016, 13, 20150937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, S.B. Revisiting Rural Non-farm Sector Employment in India: Trends from 1993-94 to 2023-24. Indian Journal of Human Development 2025, 0, 09737030251322830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.; Sun, W.; Zhao, Z. Employment structure in China from 1990 to 2015. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 2021, 185, 168–190. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, I. Productive knowledge, economic sophistication, and labor share. World Development 2021, 139, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, S.; Chen, Q. Analyzing the driving and dragging force in China’s inter-provincial migration flows. International Journal of Modern Physics C 2019, 30, 1940015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. The evolution of Zipf’s law indicative of city development. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2016, 443, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.R. The China dream is an urban dream: Assessing the CPC’s national new-type urbanization plan. Journal of Chinese Political Science 2015, 20, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Xie, Y. Re-examination of Zipf’s law and urban dynamic in China: a regional approach. The Annals of Regional Science 2012, 49, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wei, H.; Lu, S.; Dai, Q.; Su, H. Assessment on the urbanization strategy in China: Achievements, challenges and reflections. Habitat International 2018, 71, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Du, W. Too big or too small? The threshold effects of city size on regional pollution in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Luo, Q.; Chen, S. Promoting coordinated spatial governance of mega-cities in China via spatial organization of metropolitan areas. Frontiers of Urban and Rural Planning 2024, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Dong, S.; Lin, C. The Necessity and Control Strategy of “Medium Density” in Metropolis. Int. Urban Plan 2021, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zipf, G.K. Human behavior and the principle of least effort: An introduction to human ecology; Ravenio Books, 2016.

- Hu, Y.; Connor, D.S.; Stuhlmacher, M.; Peng, J.; Turner Ii, B. More urbanization, more polarization: evidence from two decades of urban expansion in China. npj Urban Sustainability 2024, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bee, M.; Riccaboni, M.; Schiavo, S. The size distribution of US cities: Not Pareto, even in the tail. Economics Letters 2013, 120, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.J.; Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. The city size distribution debate: Resolution for US urban regions and megalopolitan areas. Cities 2012, 29, S17–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.D.; Ning, Y. Spatial and temporal evolution of urban systems in China during rapid urbanization. Sustainability 2016, 8, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Smith, T.E.; Hsu, W.T. Common power laws for cities and spatial fractal structures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 6469–6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, H.V.; Oehlers, M.; Moreno-Monroy, A.I.; Kropp, J.P.; Rybski, D. Association between population distribution and urban GDP scaling. Plos One 2021, 16, e0245771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.X.; Guo, N.S.; Li, C.L.K.; Smith, C. Megacities, the world’s largest cities unleashed: major trends and dynamics in contemporary global urban development. World Development 2017, 98, 257–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Four theses in the study of China’s urbanization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2006, 30, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.R.; Sun, L.; Cebrian, M.; Youn, H.; Rahwan, I. Small cities face greater impact from automation. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2018, 15, 20170946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Shi, P.; Liu, Y. Society: Realizing China’s urban dream. Nature News 2014, 509, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.R.; Hui, E.C.M.; Choguill, C.; Jia, S.H. The new urbanization policy in China: Which way forward? Habitat International 2015, 47, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhu, N. City size distribution in China: are large cities dominant? Urban Studies 2009, 46, 2159–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Huang, Q.; He, C.; Dou, Y. Similarities and differences of city-size distributions in three main urban agglomerations of China from 1992 to 2015: A comparative study based on nighttime light data. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2017, 27, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, P.; Song, S. China’s development policies and city size distribution: An analysis based on Zipf’s law. Urban Studies 2017, 54, 2818–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, E.; Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Li, L. Spatio–temporal dynamics and human–land synergistic relationship of urban expansion in Chinese megacities. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECNS. 17 Chinese cities have a population of over 10 million in 2021. https://www.ecns.cn/news/cns-wire/2022-05-26/detail-ihaytawr8118445.shtml, 2022. Accessed: 2025-05-21.

- Liesner, H. The European Common Market and British Industry. The Economic Journal 1958, 68, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M. Gibrat’s Law for (All) Cities: Comment. American Economic Review 2009, 99, 1672–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, H. Study on the law of urban population size distribution in China. Chinese Journal of Population Science 2016, 000, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Yan, Z.; Wang, W. Urban population size, industrial agglomeration model and urban innovation: empirical evidence from 271 cities at prefecture level and above. Chinese Journal of Population Science 2020, 34, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, K. Research on Urban Power Law Distribution and Urban Allometric Scaling. PhD thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2019.

- Blank, A.; Solomon, S. Power laws in cities population, financial markets and internet sites (scaling in systems with a variable number of components). Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2000, 287, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaix, X. Power laws in economics: An introduction. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2016, 30, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Val, R.; Lanaspa, L.; Sanz-Gracia, F. New evidence on Gibrat’s law for cities. Urban Studies 2014, 51, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalanne, A. Zipf’s law and Canadian urban growth. Urban Studies 2014, 51, 1725–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Sun, N.; Jiang, Y. Applicability of Zipf’s law and Gibrat’s law in urban size distribution in China. The Journal of World Economy 2018, 000, 96–120. [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhout, J. Gibrat’s Law for (All) Cities. American Economic Review 2004, 94, 1429–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malevergne, Y.; Pisarenko, V.; Sornette, D. Testing the Pareto against the lognormal distributions with the uniformly most powerful unbiased test applied to the distribution of cities. Physical Review E 2011, 83, 036111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, P.H.; et al. Minimax methods in critical point theory with applications to differential equations; Number 65, American Mathematical Soc., 1986.

- Frank, M.R.; Sun, L.; Cebrian, M.; Youn, H.; Rahwan, I. Small cities face greater impact from automation. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2018, 15, 20170946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, G.; Rauch, J.; Redding, S.J. Task Specialization in U.S. Cities from 1880 to 2000. Journal of the European Economic Association 2019, 17, 754–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balland, P.A.; Jara-Figueroa, C.; Petralia, S.G.; Steijn, M.P.; Hidalgo, C.A. Complex economic activities concentrate in large cities. Nature Human Behaviour 2020, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albouy, D.; Behrens, K.; Robert-Nicoud, F.; Seegert, N. The optimal distribution of population across cities. Journal of Urban Economics 2019, 110, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.V. Optimum city size: The external diseconomy question. Journal of Political Economy 1974, 82, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R.; Camagni, R. Beyond optimal city size: an evaluation of alternative urban growth patterns. Urban Studies 2000, 37, 1479–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, F.; Tanaka, T.; Nakayama, N. Estimation of optimal metropolitan size in Japan with consideration of social costs. Empirical Economics 2015, 48, 1713–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, K.; Südekum, J. Zipf’s law for cities in the regions and the country. Journal of Economic Geography 2011, 11, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Yin, J.; Liu, Q. Zipf’s law for all the natural cities around the world. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2015, 29, 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbavatz, V.; Barthelemy, M. The growth equation of cities. Nature 2020, 587, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Urbanization Path and City Scale in China: An Economic Analysis. Economic Research Journal 2010, 10, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Carlino, G. Manufacturing agglomeration economies as returns to scale: A production function approach 1982. 50, 95–108.

- Jin, X. Theories on the Optimum Scales of Cities and Empirical Study: Taking the Example of the Three Municipalities. Shanghai Economic Review 2004, 2004, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The Empirical Study of Optimal City Size in China: The Perspective of Economic Growth. Shanghai Economic Review 2009, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, Z.; Yang, X. Optimal city size in China: An extended empirical study from the perspective of energy consumption. China City Planning Review 2017, 26, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010-2019. Technical report, Population Division, United States Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2020.

- Sun, W.; Jones, J.; Gamber, M. A Turning Point for China’s Population: No Child and Long Illness. Aging and Disease 2023, 14, 1950–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P. Population Decline Narrows, Population Quality Continues to Improve. https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/sjjd/202501/t20250117_1958337.html, 2025. National Bureau of Statistics of China.

- United Nations. World Population Aging. Technical report, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, New York, NY, 2017.

- Liang, J. Prospects for Chinas drive for innovation: from the perspective of demographics. In China and the West; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2021; pp. 135–147.

- Yu, X.; Yi, T. Analysis on the Influencing Mechanism of Population Agglomeration, Industry Agglomeration and Innovation Agglomeration in Chinese Megacities. Commercial Research 2020, 62, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Zipf, G.K. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort: An Introduction to Human Ecology; Ravenio Books: London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Jia, T. Zipf’s law for all the natural cities in the United States: a geospatial perspective. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2011, 25, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, C.A.; Hausmann, R. The building blocks of economic complexity. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2009, 106, 10570–10575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, R.; Hidalgo, C.A. The network structure of economic output. Journal of Economic Growth 2011, 16, 309–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Wang, Y. Analysis on the causes of frequent economic recession in Northeast China – the change from "industry absence" to "system solidification". Social Science Front 2017, 000, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Urban areas are ranked by population size in descending order. The population of the urban area ranked r is proportional to . For example, the largest urban area has twice the population of the second-largest urban area, three times that of the third-largest urban area, and so on. Although Zipf’s law is not expressed as a probability density function, it also indicates that the population of top-ranked urban areas is much larger than that of lower-ranked urban areas. |

| 2 | The resident population can fully reflect the mobility characteristics of the current Chinese population and accurately depict the urbanization level based on the resident population standard. |

| 3 | According to the spirit of the 28th executive meeting of the State Council, the National Bureau of Statistics issued the Notice on Improving and Standardizing Regional GDP Accounting on January 6, 2004, requiring provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities to uniformly calculate per capita GDP using the resident population (i.e., the registered population minus the outflow population of more than half a year plus the inflow population). |

| 4 | Specifically, 16 cities lack GRP data for several years, which poses problems for obtaining permanent resident population data (Sansha, Zhangzhou, Bijie, Zunyi, Tongren, Lasa, Rikaze, Changdu, Linzhi, Shannan, Naqu, Longnan, Haidong, Zhongwei, Tulufan, Hami); 2 cities lack all employment population data of certain industries (Ziyang and Hengshui), and these 18 cities were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, Laiwu was merged into Jinan in January 2019, and it was retained in the analysis to maintain consistency |

| 5 | As there are many empirical models of the optimal city size, which cannot be tested one by one, we only take a representative model as an example to compare such methods with the empirical results of our study. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).