1. Introduction

China’s rapid urbanization has been a cornerstone of its economic development over the past few decades. In recent years, China has entered a “high-quality development” stage, emphasizing sustainable and inclusive growth. Urbanization remains a critical pathway to address rural challenges, expand domestic demand, and promote coordinated regional development. The national urbanization rate reached about 66% by 2024, but development is uneven across regions. Coastal and metropolitan areas boast high urbanization levels, whereas many interior and resource-dependent regions lag behind. In south-central Hebei Province – notably the Handan-Xingtai area – most county-level cities are resource-based (reliant on coal, minerals, or heavy industry) and have experienced slower urbanization. The average urbanization rate in this region is around 41%, significantly below the national average. Understanding how to accelerate urbanization in these resource-based county-level cities is of great significance for regional balance and sustainable development.

National policies have recognized this urgency. The State Council’s

“People-Centered New Urbanization” Five-Year Action Plan (2021–2025) identified Hebei’s south-central region as a key area with high urbanization potential, calling for accelerated new-type urbanization and industrial transformation in tandem [

1]. New-type urbanization in China refers to an urbanization process that is human-centered, inclusive, and coordinated, emphasizing integration of rural migrants, sustainable resource use, and harmonious urban–rural development [

1]. In resource-rich but economically lagging areas, this means finding new drivers of growth beyond resource extraction and ensuring rural populations can urbanize with improved livelihoods.

This study examines the urbanization process of Wuan City, a typical resource-based county-level city in south-central Hebei, as a case example. Wuan (also spelled Wu’an) has long been dependent on coal and steel industries, and its urbanization has trailed behind its industrial growth. We investigate the factors constraining Wuan’s urbanization and explore development paths under the new-type urbanization paradigm. Specifically, we analyze: (1) the urban–rural income disparity and its trends, (2) the industrial structure and emerging economic drivers, (3) the internal economic mechanisms affecting sustainable urban development, and (4) Wuan’s overall urbanization level using a composite index. We then discuss practical pathways for industrial transformation-driven urbanization in Wuan, which may serve as reference models for similar resource-based cities.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews relevant literature on urbanization theories and the context of resource-based cities.

Section 3 describes the research area, data, and methodology, including the indicators and models applied.

Section 4 presents the results of the empirical analysis, covering Wuan’s urban–rural income gap, industrial shift-share analysis, factor contribution model, and composite urbanization index.

Section 5 discusses the new urbanization development paths identified for Wuan (incremental urbanization at the urban fringe, in-situ urbanization of the existing population, and development of characteristic small towns).

Section 6 concludes with key findings, policy implications, and the broader applicability of the case, as well as cautioning that strategies must be tailored to local conditions.

2. Literature Review

Urbanization theories provide a foundation for understanding urban growth patterns. From a regional perspective, Growth Pole Theory [

2] argues that development radiates from dynamic “poles” – fostering key industries in specific locations can stimulate growth in surrounding areas. This concept highlights the role of industrial agglomeration in urbanization: successful growth poles spur urban growth through polarization effects (drawing labor and capital inward) and, eventually, spread effects that benefit peripheral areas. Migration models (e.g., Todaro’s model [

3]) explain rural-to-urban migration by expected income gains: even if urban unemployment is high, the prospect of higher future income drives persistent migration from rural areas. This helps clarify why people continue moving to cities despite urban poverty or joblessness in many developing countries. Dual-sector theory [

4] highlights that surplus rural labor can fuel industrial growth until the labor surplus is absorbed; industrial expansion (via cheap labor) drives economic growth and urbanization until rising wages shift the dynamic. In essence, these classical theories emphasize industrialization and employment opportunities as engines of urban growth, and the reallocation of labor from agriculture to industry as a core mechanism of urbanization.

In the Chinese context, scholars have proposed models tailored to China’s unique conditions. In the early 1980s, Fei Xiaotong’s Small Towns Theory [

5] argued that China should “take the road of small towns” – developing small cities and market towns as the main venues for absorbing rural migrants, with large cities stay relatively stable. Fei observed that township and village enterprises could provide local non-farm jobs, enabling farmers to urbanize in place without massive migration to big cities [

5]. As incomes rose and local infrastructure improved, these small towns could gradually expand, accelerating grassroots urbanization [

5]. This perspective aligned with policies of that era encouraging rural urbanization and the growth of thousands of small market towns. Around the same time, urban planner Zhou Yixing stressed coordinated development across China’s urban hierarchy [

6]. Zhou’s theory of coordinated urbanization contends that the vast multi-tiered urban system should leverage the distinct roles of large, medium, and small cities (and towns) in a complementary manner. Rather than unchecked growth of megacities, he advocated a balanced approach: integrate urban and rural development, facilitate industry–agriculture linkages, and pursue urbanization at a moderate pace appropriate to local conditions. Importantly, Zhou argued that market forces should guide urbanization, but government planning and intervention are necessary to correct imbalances [

6]. This reflects the “Chinese characteristic” of urbanization – a blend of market-driven growth and strategic state oversight to ensure equitable, orderly development.

Resource-based cities – urban centers whose growth historically depended on natural resource extraction (coal, minerals, oil, timber, etc.) – face special challenges in sustaining development once resources become depleted [

7]. Decades of resource-led growth often produce a singular industrial structure and over-reliance on heavy industry, resulting in imbalanced economies that struggle to diversify [

8]. Environmental degradation is another common issue: mining and heavy industry cause ecological damage, and resource exhaustion leaves scarred landscapes [

9]. Economically, many resource-dependent cities suffer from the “resource curse” [

10], where reliance on natural resources inhibits broader development. Empirical studies have found symptoms of this in China: slowing growth, declining investment appeal, and even urban shrinkage (population loss via out-migration) in some mining cities [

1,

11,

12,

13].

Recognizing these issues, China’s government has promoted strategies for transforming resource-based cities. The National Sustainable Development Plan for Resource-Based Cities (2013–2020) classified 262 such cities (126 at prefecture level) into growing, mature, declining, and regenerating categories and called for tailored measures in each. The emphasis is on industrial transformation and upgrading – developing alternative industries (manufacturing, modern services, high-tech), improving resource efficiency, and fostering innovation to replace the old engines of growth. Urbanization policies are seen as a key vehicle for this transformation [

14,

15]. The National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014–2020), for example, highlighted integrating urbanization with industrial restructuring [

1], especially in old industrial bases and mining regions. Recent evidence supports the impact of such policies: Yang

, et al. [

16] found that China’s new urbanization pilot initiatives significantly boosted economic growth in resource-based cities by improving resource allocation efficiency and promoting industrial structure upgrading. Notably, their study found the gains were greater in resource-rich cities than in resource-depleted ones, and stronger in energy-based (coal, oil) cities than in ore-based cities. In other words, cities like coal towns saw clearer benefits from new urbanization policies than did ore mining cities, and central inland regions lagged somewhat behind eastern and western regions. This finding is pertinent for Wuan (an ore-mining city in northern China) – it suggests that simply rolling out urbanization policies may not yield the best possible results unless accompanied by substantive economic transformation tailored to the city’s resource profile [

1,

17].

Overall, the literature indicates that for resource-dependent cities like Wuan, urbanization and economic transformation must go hand in hand. Traditional theories stress industrialization and migration as drivers of urban growth, but in a resource-based context the quality of industrialization (shifting to more sustainable, diversified industries) is crucial [

17]. Urbanization strategies need to account for the inherited challenges of resource dependence: bridging urban–rural disparities, reorienting the industrial structure, and mitigating environmental constraints. We envision the case of Wuan City will shed light on how these dynamics play out and what innovative approaches can achieve “high-quality” urbanization in a resource-based economy, contributing to the literature of sustainable development for locations that are often struggling in the new era.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Data

Wuan is a county-level city in the southern part of Hebei, on the eastern foothills of the Taihang Mountains (under Handan Municipality). Geographically, it sits near the tri-province border of Hebei, Shanxi, and Henan, historically serving as a regional crossroads. This position gives Wuan strategic connectivity: multiple railway lines (unusually dense for a county city) pass through, linking it directly to major ports like Tianjin and Qingdao, and national highways and expressways connect it north–south and east–west. In short, Wuan is well-located for regional transport and trade.

Economically, Wuan is one of the stronger county economies in China, yet its development is heavily resource-oriented. In 2024, Wuan’s GDP was ¥83.0 billion, and it ranked 88th among China’s “Top 100 Counties” by comprehensive strength. The economic structure is dominated by the secondary (industrial) sector (approximately 58% of GDP, vs. 4% primary and 38% tertiary). Traditional steel production is the backbone of Wuan’s industry – the city is a major steel and coal producer, part of Hebei’s larger steel industry cluster. Several large iron & steel enterprises and related mining companies anchor the economy. However, higher value-added manufacturing (e.g. advanced equipment) is still in an early stage, and modern services remain underdeveloped relative to industry. Wuan’s dependency on external resources is notable: local iron ore reserves are limited, so about 90% of the ore for its steel mills is imported from outside the city, and coking coal is entirely brought in from other regions. Water resources are also scarce. These resource and environmental constraints – heavy reliance on energy- and resource-intensive industries, coupled with input shortages – pose significant challenges for Wuan’s sustainable growth model.

In terms of urbanization, by the end of 2024 Wuan’s urban population was about 0.88 million, yielding an official urbanization rate of roughly 56%. This is well below the national average (~65% in 2024), indicating that over 44% of Wuan’s residents still live in rural areas. The city’s urbanization has lagged behind its industrialization: Wuan industrialized rapidly thanks to mining and steel, but a large portion of its workforce remained in rural villages or in agriculture and village enterprises. The relatively slow urban population growth can be attributed to factors such as the lack of a large central city (Wuan is the only county-level city in Handan prefecture, so it doesn’t have a big metropolis to draw migrants), limited high-end service sector jobs to attract or retain migrants, and possibly institutional factors like hukou (household registration) barriers that discourage rural residents from settling permanently in town. In essence, industrial growth alone did not automatically translate into high urbanization – targeted policies and investments are needed to facilitate rural-to-urban transitions and improve urban living conditions.

For this study, we collected a range of data from official sources. Socio-economic time series data (2000–2022) for Wuan came from local statistical yearbooks, government reports, and the Hebei Provincial Statistical Yearbook. Key indicators include total population and urban population, rural and urban per capita incomes, sectoral value added (for primary, secondary, tertiary sectors), fixed asset investment, and infrastructure and public service metrics (e.g. road area per capita, utility coverage rates, etc.). Additionally, Wuan’s local government provided some specialized data, such as output and employment figures for major industries, which inform our analysis of the industrial structure. Where needed, we supplemented city-level data with provincial or national statistics for context or benchmarking (for example, using Hebei’s average sector growth rates as a reference in the shift-share analysis). All monetary figures (e.g. GDP) are in current RMB; we deflated series to constant prices for analytical modeling when appropriate. Key population and income figures were cross-checked with national census data (2010, 2020) for consistency.

3.2. Methodology

To systematically evaluate Wuan’s urbanization challenges and prospects, we employ a multi-method approach, combining quantitative indices and models with qualitative analysis.

3.2.1 Urban–Rural Income Disparity Analysis – Theil Index

We assess the inequality between urban and rural incomes using the Theil index, a measure from information theory commonly used to quantify income disparity [

18]. The Theil index (

) has the advantage of being decomposable into “within-group” and “between-group” inequality. We treat urban and rural residents as two groups and compute the Theil index of per capita income distribution between these groups annually. If

is the total income of group

(urban or rural),

the total combined income,

the population of group

and

total population, then the between-group Theil index is:

Here, a higher

indicates greater inequality (urban–rural income gap. We calculate

for each year from 2010 to 2022 using data on urban per capita disposable income, rural per capita net income, and the respective population sizes of Wuan’s urban and rural residents. A declining Theil index over time would signal a narrowing income gap, which is often a goal of inclusive urbanization [

1]. We also decompose the index to understand how much of the inequality is due to differences

between urban and rural areas versus inequality

within each area, though our focus is on the between-group component since our interest is the urban–rural divide. By analyzing trends and fluctuations in the Theil index, we can infer how urban–rural integration in Wuan has progressed and identify years where the gap widened or narrowed, linking those to possible causes (e.g. policy changes, economic shocks).

3.2.2. Industrial Structure and New Economic Drivers – Shift-Share Analysis

To evaluate Wuan’s industrial transformation so we can fathom how it supports urbanization, we use the shift-share analysis method [

19,

20]. Shift-share analysis breaks down the growth of a region’s industries into different components to identify whether growth is due to overall economic trends, the industry mix, or the region’s specific competitive advantages [

19]. For Wuan’s economy, we examine the period 2014–2022, a time of active industrial restructuring locally. We compare Wuan’s industrial growth to a broader reference (we use Hebei Province as the benchmark region). For each sector (primary, secondary, tertiary), we compute:

Reference Share Component (N): how much the sector would have grown if it grew at the average rate of the reference region’s economy. This reflects the effect of general economic growth.

Industry Mix (Structural) Component (P): the growth attributable to the sector’s specific growth rate at the reference level minus the general growth rate. A positive structural component means the industry is a fast-growing sector in the broader economy (so having more of it is an advantage for the region).

Regional Competitive Component (D): the residual growth due to the region’s own competitiveness in that sector, computed as the actual growth minus what would be expected from the reference growth for that sector. A positive competitive component indicates Wuan outperformed the provincial average in that industry, suggesting local advantages (e.g. productivity, policy support, innovation).

Mathematically, let and be sector ’s value at the base (2014) and end (2022) in Wuan, and , the total economy values for Wuan at base and end. Let , be the total GDP of Hebei at base and end, and , the sector totals for Hebei. Then using Hebei as the reference, we can get the , , and as follows:

– growth of sector if it grew at Hebei’s overall rate.

– additional growth due to sector ’s provincial trend deviating from the average (structure effect).

– growth due to Wuan’s competitive performance in sector .

We applied this to Wuan’s primary (agriculture), secondary (industry), and tertiary (services) sectors. The analysis provides insight into which sectors are driving Wuan’s economic changes: for instance, is Wuan’s industrial sector (secondary) lagging because of structural disadvantages (e.g. overrepresentation of declining industries) or competitive issues (e.g. lower productivity than elsewhere)? Likewise, we see whether services are emerging as a strength, and how agriculture is faring. This helps diagnose the economic restructuring underlying urbanization: a competitive, growing tertiary sector and a modernized secondary sector are typically needed to support sustained urban population growth in a resource-based city transitioning to a more diversified economy.

3.2.3. Economic Growth Mechanism – Cobb-Douglas Production Function

To further investigate Wuan’s internal growth dynamics and the contribution of production factors, we employ a Cobb-Douglas production function model as is commonly done [

21]. This model relates output to inputs of capital and labor (and technology) in the form

, where

is total output (we use GDP as a proxy),

is capital input,

is labor input,

represents total factor productivity (technology level), and

,

are output elasticities of capital and labor respectively. Assuming constant returns to scale (

), this model can be used to estimate how much of Wuan’s economic output growth comes from capital versus labor contributions, with

capturing the effect of technological progress or efficiency improvements [

22,

23].

We compiled a dataset of Wuan’s economy over time (using annual data from 2000 to 2020) including proxies for and . Capital input is represented by cumulative fixed asset investment. Labor input is measured by the number of employed people. We then estimated the production function parameters and . The resulting output elasticities indicate the factor intensity of Wuan’s growth model. In Wuan’s case, we found and (approximately), suggesting that labor has a roughly threefold greater elasticity than capital in producing output. hey reflect the extent to which Wuan’s growth has been labor-driven versus capital-driven.

3.2.4. Comprehensive Urbanization Level – Indicator System and Composite Index

Recognizing that urbanization is a multi-dimensional process, we developed an indicator system to evaluate Wuan’s overall level of “new-type” urbanization [

1]. Rather than using a single metric, we feel a composite index can capture various facets: economic, social, and environmental. Based on China’s new urbanization connotations [

1,

24], we identified four broad dimensions (first-level indicators) that are essential to high-quality urbanization: Economic Dynamism, Population and Migration, Infrastructure Development, and Living Environment. Under each dimension, we selected specific measurable indicators (second-level indicators) relevant to Wuan’s context, totaling 15 indicators.

Table 1 summarizes the indicator system and weights. The selection and weighting were guided by policy priorities and literature consultations [

1,

17,

25,

26].

Economic Dynamism (A): reflects the economic foundation for urbanization. Indicators include per capita GDP (A₁), the share of industrial output in GDP (A₂), the share of the tertiary sector in GDP (A₃), and the urban fixed asset investment growth rate (A₄). These gauge economic output, structure, and investment – higher values indicate stronger economic support for urban growth. This dimension was given a total weight of 28% in the index (with slightly higher weights for per capita GDP, etc.).

Population & Migration (B): captures demographic urbanization. Indicators include overall population growth rate (B₁), urban population growth rate (B₂), proportion of urban population in total population (i.e. urbanization rate) (B₃), and urban unemployment rate (B₄). These reflect population dynamics and employment. Notably, a higher urbanization rate and healthy population growth contribute positively, while a lower unemployment rate is also favorable (we treat unemployment with inverse scoring). This dimension had about 32% weight (with the urban population share being quite important at 9%).

Infrastructure (C): measures the development of urban infrastructure and services. We used indicators such as per capita urban road area (C₁), coverage of urban water supply (C₂), coverage of urban gas supply (C₃), and number of public transit vehicles per 10,000 people (C₄). These indicate the physical infrastructure and transit that support urban life. Adequate roads, utilities, and public transport are necessary for a city’s functioning and expansion. This dimension was weighed about 23% of the total (with road area and utility coverage each around 6%, transit 5%).

Living Environment (D): gauges environmental sustainability and livability. Indicators include garbage treatment rate (D₁), per capita public green space (D₂), and green coverage ratio of the built-up area (D₃). These reflect sanitation, parks, and greenery – aspects that improve quality of life and ecological conditions in urban areas. Weights here sum to ~18% (with waste treatment at 7%, green space and green coverage at 5-6%).

Each indicator was normalized (we applied standard range normalization for each year, or z-scores if a baseline was established) and weighted to compute a yearly composite urbanization index for Wuan for the period 2000–2022. The index provides a single summary measure of Wuan’s urbanization progress across economic, demographic, infrastructural, and environmental dimensions. An upward trend in the index signifies comprehensive improvement in urbanization quality, whereas stagnation or decline might point to emerging issues.

By examining the composite index over time, we can identify distinct stages in Wuan’s urbanization process and correlate them with historical events or policy phases. For example, a rapid rise in the index might coincide with periods of intensive investment and development, while a plateau or dip could indicate structural adjustments or external shocks.

Finally, using all the above analyses, we interpret the findings in a holistic manner to propose urbanization development pathways for Wuan. The qualitative aspect of our method involves case analysis of specific urbanization initiatives in Wuan (e.g. development zone projects, rural housing reforms, small town pilots) to illustrate how the city is trying to implement new-type urbanization on the ground. This is detailed in the Discussion section, where we categorize Wuan’s approach into distinct models or strategies.

In summary, our methodology combines inequality analysis, structural economic analysis, growth factor analysis, and multi-dimensional urbanization assessment. This comprehensive approach is appropriate for a resource-based city like Wuan, where the urbanization process is tightly interwoven with economic transformation and social changes. Next, we present the results of these analyses for Wuan City.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical findings from the analysis of Wuan City’s urbanization dynamics. It focuses on urban-rural income disparities, industrial structure transformation, the contributions of labor and capital to economic growth, and comprehensive urbanization trends. Interpretations and broader discussions of these results are elaborated in

Section 5.

4.1. Urban-Rural Income Disparity Trends (2010–2022)

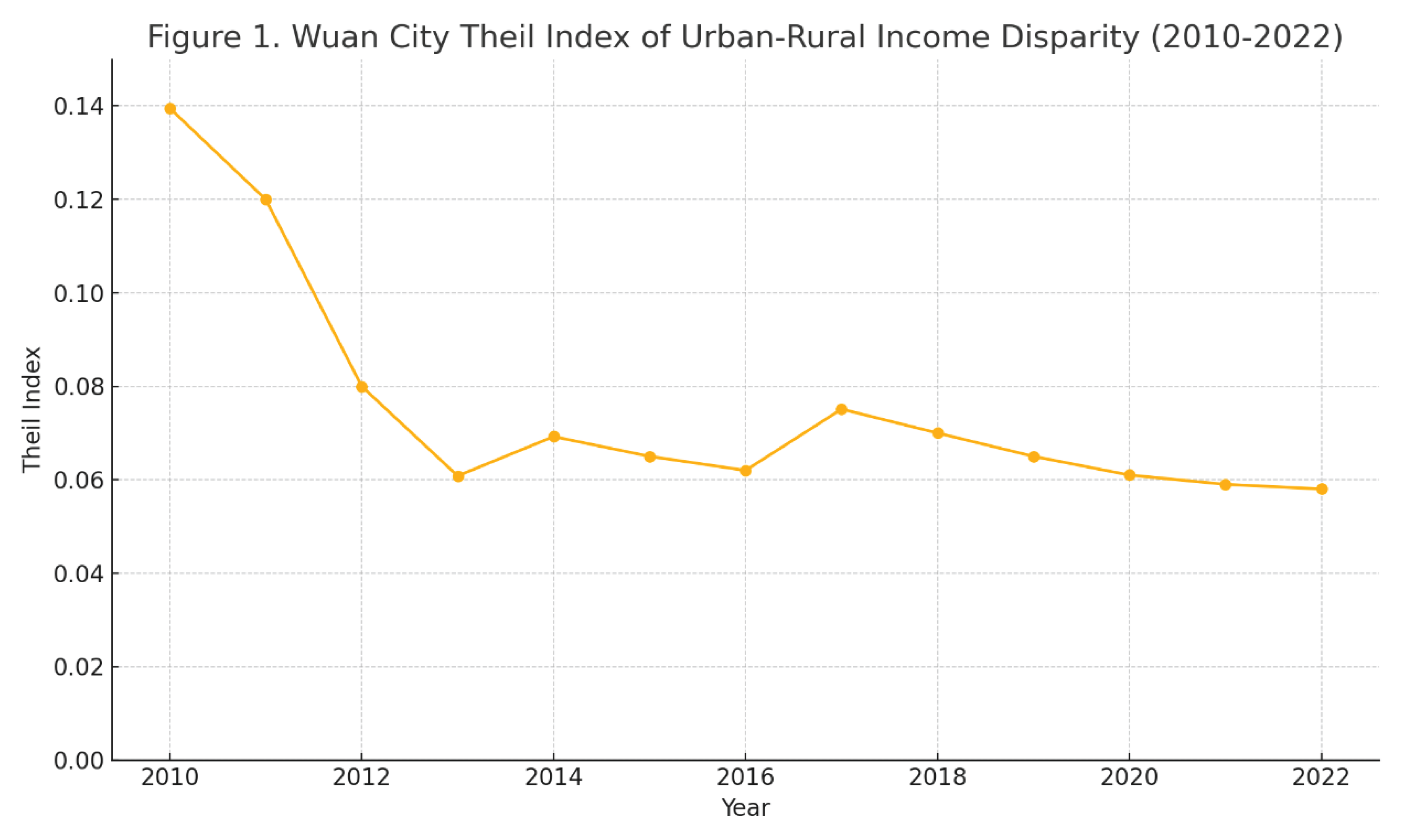

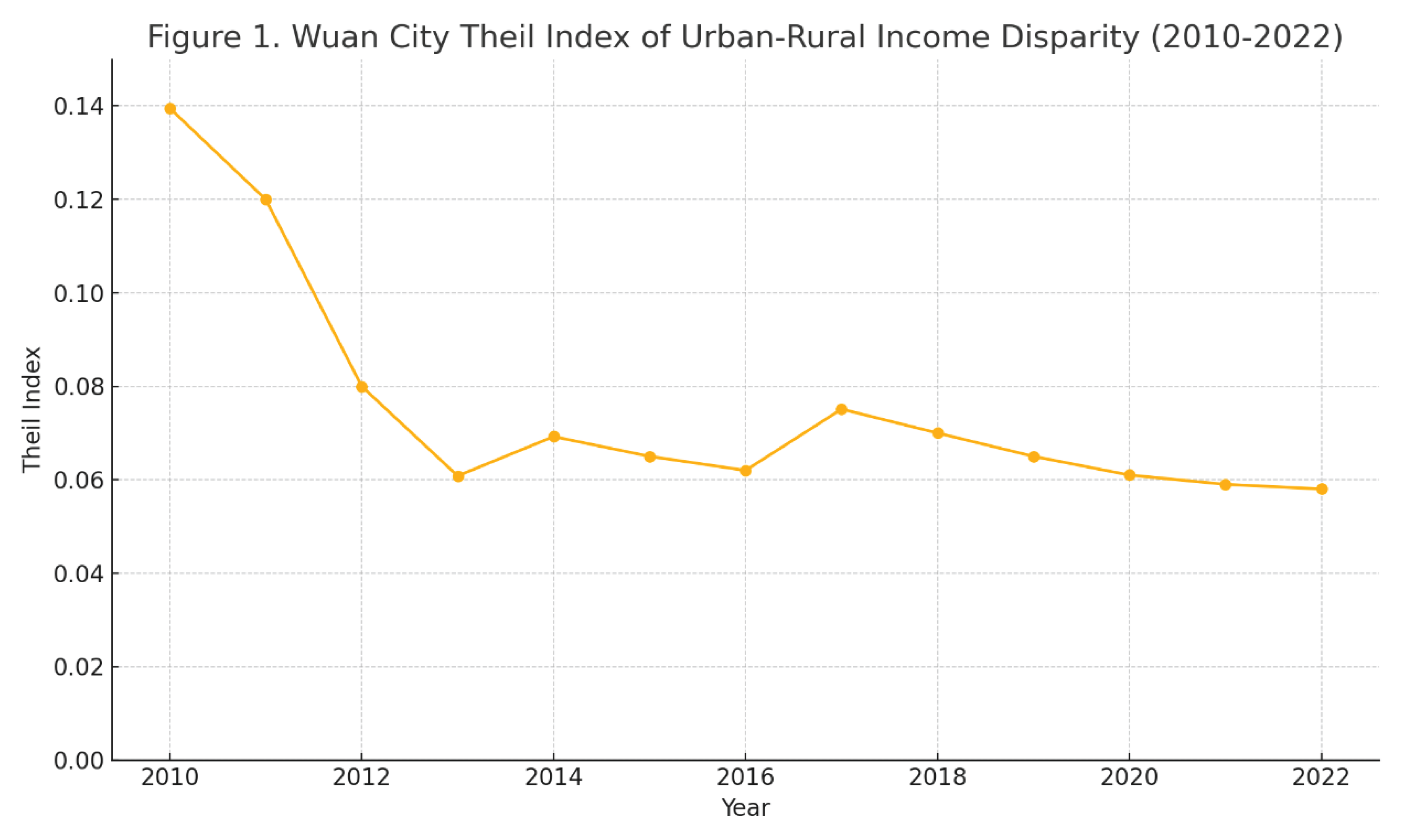

The evolution of urban-rural income disparity in Wuan City between 2010 and 2022 was assessed using the Theil index as discussed in the method section. A higher index value signifies a larger income gap. The analysis reveals a notable narrowing of this disparity over the period. In 2010, Wuan’s Theil index stood at approximately 0.14, reflecting a substantial income gap where urban per capita disposable income was considerably higher than rural per capita income. By 2022, this index had declined significantly to 0.058, roughly half of its 2010 level (as depicted in Figure 1). This overall downward trend suggests a relative improvement, with rural income growing closer to urban income.

The trajectory of this decline was not monotonic. Temporary increases in the Theil index, indicating a widening of the income gap, were observed (Figure 1). For instance, in 2014, the index rose to approximately 0.069 from about 0.061 in 2013. Another uptick occurred in 2017, with the Theil index increasing to around 0.075. Despite these fluctuations, the general downward trend in income disparity resumed after each interruption, with the index reaching its lowest recorded point in 2022. It is important to note, however, that a Theil index of 0.058 in 2022 still indicates the persistence of income inequality. Rural residents in Wuan continue to experience lower average incomes and less stable employment conditions compared to their urban counterparts.

4.2. Industrial Sector Performance and Structural Change (2014–2022)

A shift-share analysis of Wuan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 2014 to 2022, benchmarked against provincial trends in Hebei, provides insights into the performance and structural evolution of its primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors (

Table 1).

Primary Sector (Agriculture): Wuan’s agricultural sector exhibited an overall expansion in output during the 2014–2022 period, albeit from a relatively small base (accounting for 4–5% of GDP). The share component for the primary sector was positive and demonstrated a steady increase, suggesting that agriculture in Wuan benefited from the general growth of the broader economy. The structural component was also positive and experienced slight growth, indicating that agriculture in Hebei province grew at a faster rate than the overall provincial economy. This trend rendered Wuan’s agricultural sector, though small, slightly advantageous. The competitive component for agriculture remained close to zero throughout the period, implying that Wuan’s agricultural sector performed largely on par with the provincial average for its category, without significant outperformance or underperformance relative to this benchmark.

Secondary Sector (Industry): The secondary sector, which is dominant in Wuan, presented a mixed performance. During the initial part of the study period (2014 to approximately 2017), the share component for Wuan’s secondary industry was negative. This suggests that if Wuan’s industry had grown only at the average rate of Hebei’s GDP, its output would have declined, reflecting a potential overscaling of Wuan’s industrial base relative to general provincial growth or slower overall provincial economic growth. However, this trend reversed in the latter part of the period; the share component turned positive and grew substantially by 2018–2022, becoming significantly positive by 2019-2020. This indicates that Wuan’s industry began to grow at a faster rate than the reference economy.

The structural component for Wuan’s secondary industry was predominantly negative throughout the 2014–2022 period. This signifies that Wuan’s industrial structure was heavily weighted towards traditional steel and mining, that were experiencing slower growth or decline at the provincial level. Conversely, the competitive component for the secondary industry became positive and significant in the later years (post-2018). This suggests that Wuan’s industrial sector, within its specific industrial categories, outperformed the provincial average during this sub-period.

Tertiary Sector (Services): The service sector in Wuan demonstrated consistent expansion. The share component for the tertiary industry was positive and increased annually, aligning with the general economic trend of a rising service sector importance during urbanization and income growth. The structural component for the tertiary industry was also positive, indicating that services constituted a relatively fast-growing segment within the Hebei provincial economy, and Wuan’s possession of a service sector provided a structural advantage. Furthermore, the competitive component for the tertiary industry turned positive and grew in the later years of the analysis period. This suggests that the performance of Wuan’s service sector began to surpass provincial benchmarks for service industries.

4.3. Contribution of Labor and Capital to Economic Growth

An analysis based on the Cobb-Douglas production function provided estimates for the output elasticities of labor and capital in Wuan’s economy. The estimated output elasticity for labor (β) was approximately 0.75, while the estimated output elasticity for capital (α) was approximately 0.25. The sum of these elasticities (α+β) is approximately 1, suggesting constant returns to scale. These estimates indicate that labor input has been the dominant contributor to Wuan’s GDP growth during the period analyzed, with capital input playing a comparatively smaller role.

Table 2.

Estimated Output Elasticities for Labor and Capital in Wuan.

Table 2.

Estimated Output Elasticities for Labor and Capital in Wuan.

| Factor Input |

Estimated Output Elasticity |

Implied Contribution to GDP Growth |

| Labor |

β≈0.75 |

Dominant |

| Capital |

α≈0.25 |

Smaller |

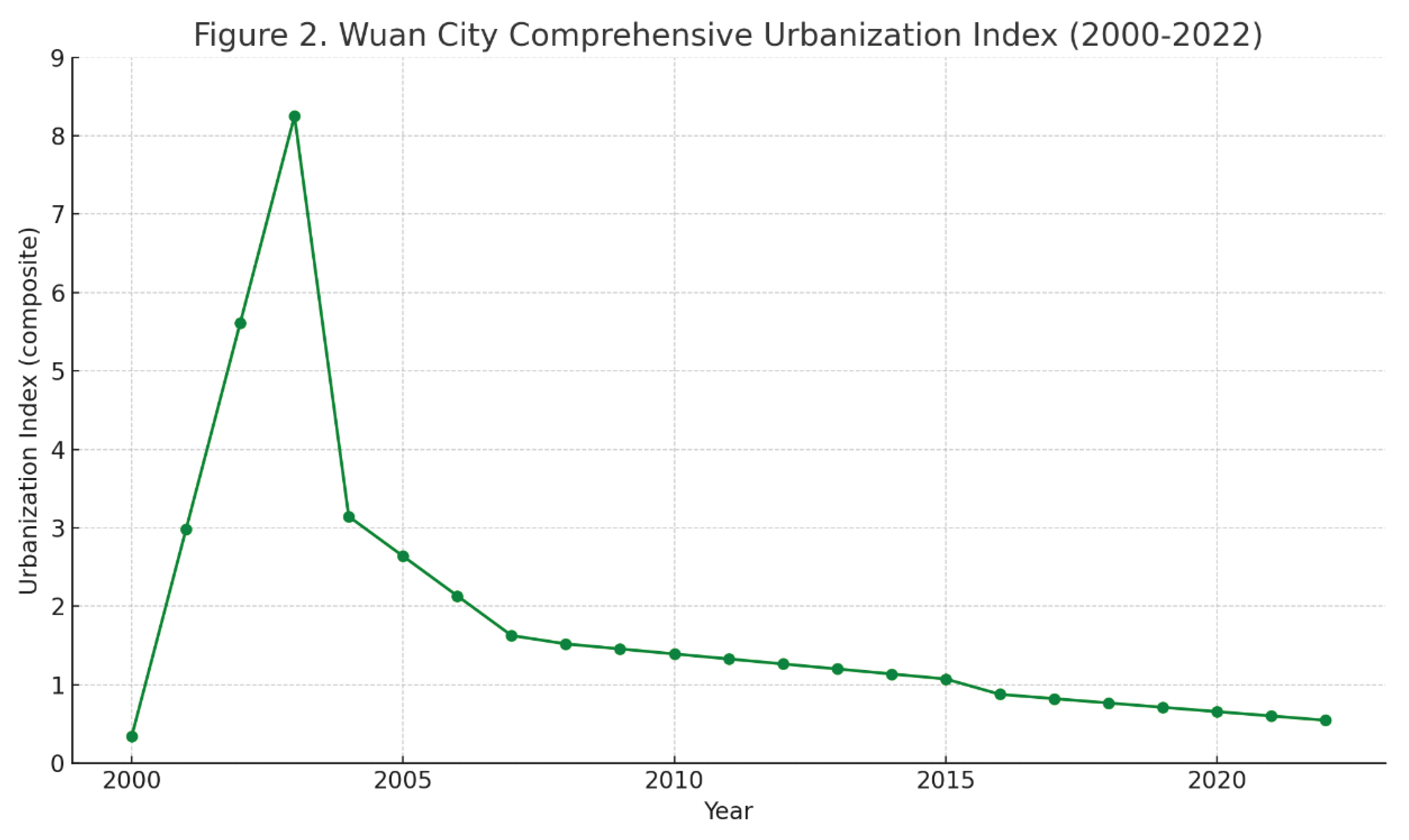

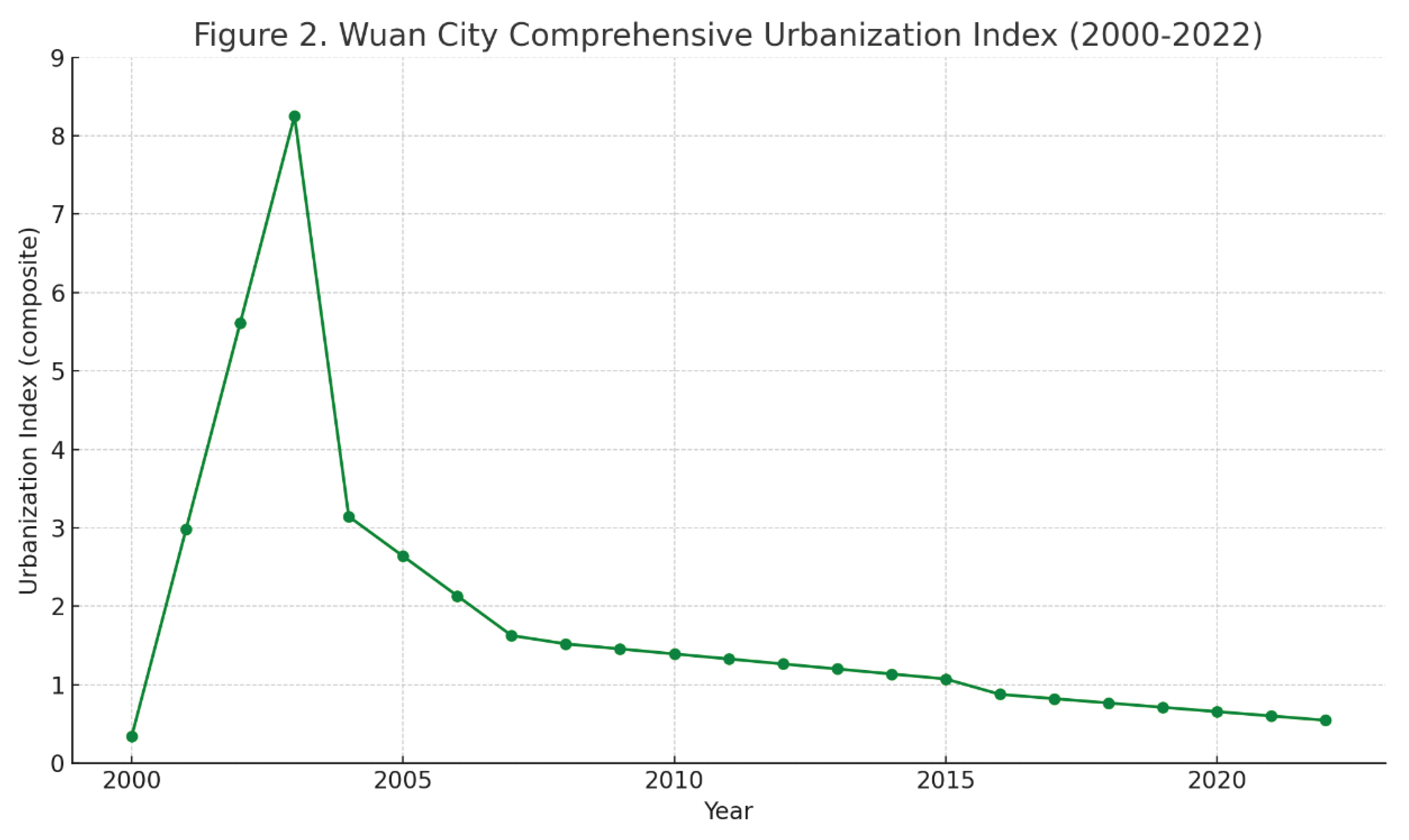

4.4. Comprehensive Urbanization Index Trajectory (2000–2022)

A comprehensive urbanization index based on the input data was calculated for Wuan City from 2000 to 2022 to gauge overall urbanization progress beyond simple population metrics. This index synthesizes 15 indicators across economic, demographic, infrastructure, and environmental dimensions. Higher values of this normalized index indicate a more advanced level of urbanization [

27,

28]. The trajectory of this composite index (Figure 2) reveals a non-linear pattern characterized by four distinct phases:

Phase 1 (2000–2003) is the Rapid Surge phase. The index exhibited a dramatic increase, rising from a low base of approximately 0.34 in 2000 to a peak of around 8.25 in 2003 on the normalized scale.

Phase 2 (2004–2007) is the Adjustment and Decline phase. Following the peak, the index fluctuated and trended downwards, falling to approximately 1.63 by 2007.

Phase 3 (2008–2015) is the Stabilization and Gradual Drift phase. During this period, the index fluctuated within a narrower range, from approximately 1.07 to 1.52, and showed a general, mild downward drift.

Phase 4 (2016–2022) is the phase of Noticeable Decline. In the most recent period, the index demonstrated a clear downward trend, declining from about 0.877 in 2016 to 0.546 by 2022.

5. Discussion

The empirical results presented in

Section 4 depict a multifaceted and evolving urbanization process in Wuan City. While significant strides have been made in areas such as narrowing urban-rural income gaps and achieving periods of robust industrial growth, these achievements are counterbalanced by underlying structural economic vulnerabilities, the limitations of a predominantly labor-intensive growth model, and a recent deceleration in overall urbanization progress, as commonly seen in resource-based cities [

11,

12]. This section synthesizes these findings to elucidate the underlying dynamics, persistent challenges, and strategic pathways being pursued for Wuan’s future urban development.

5.1. Interpreting Wuan’s Urbanization Trajectory: Achievements and Persistent Challenges

5.1.1. Urban-Rural Income Convergence and Rural Vulnerability

The substantial decline in the Theil index from approximately 0.14 in 2010 to 0.058 in 2022 clearly indicates progress in achieving relative income convergence between urban and rural populations in Wuan. This improvement can be attributed to various rural development initiatives, including the promotion of rural tourism and specialty agriculture, alongside investments in rural infrastructure. These efforts have evidently helped raise rural incomes at a faster relative rate.

However, the temporary reversals in the Theil index, notably in 2014 and 2017, expose the fragility of this convergence. These upticks, linked to difficulties within the agricultural sector, downturns in traditional rural industries due to restructuring or environmental regulations, and broader macroeconomic factors, suggest that rural incomes in Wuan possess a lower resilience compared to urban incomes. The economic base of rural areas, often less diversified and more reliant on primary sector activities or small-scale traditional industries, appears more susceptible to economic shifts and policy changes. This vulnerability implies that while relative income gaps have narrowed, the sustainability and robustness of rural income growth remain significant concerns. Achieving “people-centered urbanization” necessitates not only convergence in income levels but also the development of resilient and diversified rural economic structures.

Furthermore, the persistence of inequality, even with a Theil index of 0.058, alongside noted disparities in employment stability, the integration of rural products into shorter value chains, and differential access to high-quality public services such as advanced education and healthcare, highlights that income metrics alone do not capture the full extent of urban-rural disparities. These qualitative differences can perpetuate longer-term inequalities in human capital development, economic opportunities, and overall quality of life. This suggests that the “weak link” of rural advancement extends beyond income figures to encompass broader socio-economic and structural factors, necessitating policies that address these deeper, qualitative aspects for truly inclusive development.

5.1.2. Industrial Transformation: A Tale of Rebound and Structural Inertia

The shift-share analysis of Wuan’s industrial structure from 2014 to 2022 paints a dynamic picture. The primary sector (agriculture) maintained modest, stable growth, benefiting from overall economic expansion and favorable provincial agricultural trends. The tertiary (service) sector emerged as a consistent growth driver, with positive share, structural, and, in later years, competitive components, reflecting the broader economic shift towards services.

The secondary (industrial) sector’s trajectory is particularly revealing of Wuan’s challenges and adaptations. An initial period of struggle, marked by a negative share component, was followed by a significant rebound, with both share and competitive components turning strongly positive in the later years (post-2018). This turnaround suggests successful adaptation and upgrading within Wuan’s existing industries, particularly steel. Policy measures such as closing inefficient plants, attracting new industrial projects, and technological upgrades likely contributed to making Wuan’s industries more competitive and enabling them to grow faster than the reference provincial economy in recent years. This represents a notable achievement for a city historically reliant on traditional heavy industry.

However, this rejuvenation is shadowed by a persistently negative structural component for the secondary sector throughout the period. This indicates that Wuan’s industrial mix remains heavily skewed towards traditional sectors like steel and mining, which are characterized by slower growth or even decline at the provincial level compared to emerging industries. Thus, while Wuan has enhanced the efficiency and competitiveness of its traditional strengths, it has not yet achieved sufficient diversification into newer, faster-growing industrial areas. This “structural drag” poses a significant vulnerability; future downturns in these legacy industries could undermine the progress made and limit long-term economic dynamism.

The growth of the service sector is crucial in this context. Its positive performance across all components suggests active development and increasing competitiveness. This growth is partly autonomous, driven by general economic development, but is also intrinsically linked to the health of the industrial sector (e.g., logistics supporting steel, services for industrial employees). A continued reliance on a structurally disadvantaged secondary sector could, therefore, indirectly constrain the future potential of the tertiary sector. Sustainable urbanization and economic resilience for Wuan will depend on fostering a more balanced industrial structure, where new, high-value industries complement or gradually supplant less dynamic ones, and where the service sector’s growth is propelled by a wider array of economic activities.

5.1.3. The Labor-Intensive Growth Model at a Crossroads

The Cobb-Douglas production function analysis, yielding output elasticities of approximately 0.75 for labor (β) and 0.25 for capital (α), unequivocally points to a labor-intensive growth model in Wuan. Historically, this model capitalized on China’s demographic dividend, utilizing abundant labor in industries like mining and steel production.

However, this model faces diminishing returns and inherent limitations in the current economic landscape. With a shrinking national rural labor surplus, rising labor costs, and a general slowdown in population growth, reliance on continuous labor input for economic expansion is becoming unsustainable. Furthermore, the relatively low output elasticity of capital (0.25), despite substantial historical investments in heavy industry, hints at potential capital inefficiency. Capital may concentrate in traditional industries with low value-added or deployed sub-optimally—for instance, in maintaining outdated equipment rather than investing in transformative technologies or higher-productivity sectors. The observed concentration of Wuan’s industrial output in low- to mid-value-added products with thin profit margins supports this notion of diminishing returns to capital in its current applications.

This situation underscores a critical need for Wuan to transition from an “extensive” growth model, reliant on factor accumulation, to an “intensive” model driven by productivity improvements in both labor and capital. A key bottleneck, and simultaneously a significant opportunity, lies in human capital. The reported low average education and skill levels within Wuan’s traditional workforce impede the adoption of advanced technologies and hinder the city’s capacity to move up the industrial value chain. A labor-intensive model predicated on low-skill labor often correlates with lower wages, which can affect overall urban prosperity and attractiveness.

Therefore, substantial investment in human capital—through education, vocational training, and reskilling initiatives—is paramount. Enhancing workforce skills can directly improve labor productivity and enable the effective adoption and utilization of more advanced, capital-intensive production methods, potentially increasing the contribution of capital to output. This strategic shift is essential for generating higher-quality employment opportunities and supporting a more sustainable and prosperous urbanization path. Additionally, addressing the apparent misallocation of capital, which has historically favored urban traditional industries over rural development or emerging sectors, is crucial for fostering balanced growth and narrowing urban-rural disparities.

5.1.4. Comprehensive Urbanization: A Trajectory of Stagnation Requiring Renewal

The trajectory of Wuan’s comprehensive urbanization index from 2000 to 2022—characterized by a rapid surge (2000-2003), followed by adjustment and decline (2004-2007), a period of stabilization with a slight downward drift (2008-2015), and a more pronounced decline in recent years (2016-2022, from ~8.25 at its peak to ~0.546)—provides a stark overview of the city’s evolving urbanization challenges.

The dramatic early surge likely reflected foundational development: rapid industrial expansion, significant build-out infrastructure, and initial rural-to-urban population shifts, capitalizing on readily available resources and a high-growth national environment, especially the development of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration [

24,

29]. However, the subsequent phases, particularly the recent decline, suggest that this initial growth model was not sustainable and eventually encountered a ceiling. Once the “low-hanging fruit” of primary industrialization and basic infrastructure development was exhausted, underlying structural issues—such as the limitations of the labor-intensive model, industrial overcapacity, and emerging environmental constraints—became more prominent. Policy shifts at national and provincial levels, including industrial restructuring and stricter environmental regulations, also likely contributed to the moderated and eventually declining trajectory of the index.

The decline in the comprehensive urbanization index post-2016 is a significant concern, signaling that Wuan’s urbanization process may be stagnating or even regressing under its current economic structure and development paradigm. This suggests a potential failure to transition effectively to a higher-quality, more resilient phase of urbanization. This stagnation is likely a result of the interconnected challenges identified earlier: economic slowdown linked to industrial structural issues and lagging productivity impacts the economic and demographic components of the index; population stagnation or even net outflow, possibly due to limited high-quality employment opportunities, affects demographic indicators; and the costs associated with environmental remediation and compliance can strain resources, while a slowdown in qualitative infrastructure improvements can impact overall urban attractiveness.

Revitalizing Wuan’s urbanization, therefore, necessitates a holistic and integrated strategy that simultaneously addresses industrial upgrading and diversification, human capital development, improvements in capital allocation and efficiency, and enhancement of the urban environment and public services. The new urbanization pathways being explored by Wuan represent an attempt to tackle this multifaceted challenge and shift towards a more sustainable and inclusive development model.

5.2. Strategic Pathways for High-Quality Urbanization in Wuan

Recognizing the inherent limitations of its traditional resource-driven urbanization model, Wuan is actively implementing strategies aligned with “industrial transformation-driven new-type urbanization.” This multifaceted approach seeks to forge a sustainable and inclusive urban future by closely integrating industrial development with urban planning and population settlement strategies across various spatial scales. The following models are central to this endeavor.

5.2.1. Expanding Urban Frontiers: Incremental Population Urbanization

This strategic thrust focuses on accommodating new population growth and facilitating migration by systematically developing areas at the urban periphery and within specialized economic zones. We propose two particular models to promote this urbanization process:

First, the City-Periphery Development (Urban Fringe) Model that involves the targeted development of towns situated on the outskirts of Wuan’s main urban core, such as Anle, Tushan, and Kangcheng. By capitalizing on their geographical proximity to existing urban infrastructure and markets, these fringe towns are being transformed into functional urban neighborhoods or satellite towns. Key mechanisms include assigning specialized economic functions—Anle is developing an agricultural industrial park and cultural tourism, Tushan focuses on building materials and trade, and Kangcheng is emerging as a logistics hub. These initiatives aim to create local employment and foster industry-town integration.

Simultaneously, Wuan is investing in extending city-level utilities, transport networks, and public services to these areas, aspiring to a “four networks unified” system and “same-city” management to ensure urban living standards. Social integration is promoted through the equalization of public services for new migrants, the conversion of traditional village committees into urban neighborhood committees, and innovative land reform practices like “homestead exchange for housing”. This latter policy allows rural residents to exchange their village homesteads for apartments in the newly developed town areas, facilitating orderly resettlement. A crucial element is the experimental policy that seeks to preserve certain rural land rights for migrants while granting them access to urban social security and benefits, thereby addressing security concerns and encouraging smoother integration [

1]. This model helps manage urban expansion pressures and aims to improve economic opportunities and living conditions for populations transitioning from rural settings.

Second is the Industry–City Integration (Development Zone) Model. This model is a complementary approach that involves transforming dedicated industrial parks, such as Wuan’s provincial-level Economic & Technological Development Zone, into comprehensive new urban areas. This strategy focuses on using industry to spur urban development, and blending industrial parks with urban functions, which aims to create self-contained communities where workers and their families can live and work.

Practical measures include the relocation of major industrial enterprises, such as the Wen’an, Mingfang, and Xinjin Steel plants, from the old city center to the development zone. This move, involving approximately 40,000 workers, has created a significant population base for the new urban district. To support this population, there is a concerted effort to provide urban amenities, including housing projects, schools, healthcare facilities, and commercial services within or near the new district. Furthermore, comprehensive social support systems, encompassing employment services, social security coverage, and housing assistance, are being established for the industrial workers, many of whom are migrants, to facilitate their full transition into urban residents. This model not only aids in the modernization and consolidation of the secondary sector but also creates new, planned urban spaces, potentially alleviating pressure on the main city and improving living conditions for a substantial portion of the workforce.

5.2.2. Enhancing Existing Communities: In-Situ Urbanization of Stock Population

This pathway emphasizes the urbanization of the existing rural population within their current localities, particularly in and around Wuan’s county seat and other established townships. The concept of “urbanizing in place” aims to upgrade local communities to urban standards in terms of infrastructure, services, and governance, thereby reducing the need for long-distance migration.

Mechanisms include the progressive upgrading of villages on the urban fringe into formal urban communities, often involving the reclassification of village committees to urban residential committees. This administrative change is typically accompanied by substantial infrastructure improvements (e.g., paved roads, modern sewage systems) and housing redevelopment projects, such as the transformation of former “villages within the city”. Wuan’s central town (the county seat), which already accommodates a significant urban population (approximately 210,000 urban residents versus 170,000 agricultural population) and has been a net population inflow area, is designated as an “optimized development zone.” The strategy is to consolidate and strengthen this county seat, enabling it to evolve into a medium-sized city by concentrating resources, fostering non-farm job opportunities, and enhancing urban amenities.

To finance these transformations, Wuan has established an urban construction investment company. This entity utilizes innovative financing methods, such as collateralizing future revenues from land leases and town development projects, to fund current construction and redevelopment. This process is guided by scientific planning and a people-centered approach. Comprehensive support systems, including employment services, expanded social security (pensions, healthcare), social assistance programs, and housing support, are extended to newly urbanized residents to ensure a smooth and sustainable transition. This in-situ model helps to improve living standards locally, narrows the urban-rural gap by enhancing access to urban amenities and job markets for the existing rural populace, and contributes positively to the comprehensive urbanization index by improving local conditions.

5.2.3. Cultivating Specialized Nodes: Development of Characteristic Small Towns

The third pathway focuses on fostering selected outlying towns, those possessing unique resources or specific industrial advantages, into the so-called “characteristic small towns” [

1,

17]. These towns, often situated beyond the immediate periphery of Wuan’s main city, are envisioned as specialized local urbanization hubs, contributing to a more diversified spatial pattern of development.

The development of these towns is underpinned by integrated and specialized planning. Wuan adheres to a “five-in-one” planning framework, which integrates industrial, town, land use, ecological, and public service plans into a unified blueprint for each designated town. Development is guided by the principle of “if suited for industry, develop industry; if for agriculture, agriculture; for tourism, tourism; for commerce, commerce,” tailoring growth strategies to each town’s specific comparative advantages. A core strategy is “one town, one product/specialty,” encouraging each town to cultivate a distinct industry or theme that drives its economy and differentiates it.

Illustrative examples include Yangyi Town and Tuancheng Town. Yangyi, located in a hilly area and home to the Puyang Steel Group, is being developed as a “steel specialty town.” This involves strengthening the steel industry chain while concurrently developing an agricultural industry park for economic diversification, alongside housing programs and collective economic reforms for local villagers. Tuancheng, with a strong existing base in steel (Jinan Steel Group) and mining (North Ming River Iron Mine), is being positioned as a “Hebei Provincial Steel and Mining Industry Town,” with an emphasis on eco-friendly industrial integration and community upgrading.

In both cases, and for other characteristic towns, there is a strong emphasis on “development benefiting the people,” creating a “pleasant, livable environment,” and pursuing “reform and innovation” in local governance and land use policies. This model aims to create new urban growth poles within the county, potentially reducing regional disparities by allowing residents in more remote areas to urbanize locally. These specialized towns can become new centers of economic activity and population absorption, contributing to a more balanced and resilient regional urbanization pattern.

5.3. Implications and Future Directions for Wuan’s Urban Development

The strategic pathways adopted by Wuan City represent a comprehensive effort to navigate the complexities of transitioning from a resource-dependent, traditionally industrialized economy towards a model of high-quality, sustainable urbanization. These pathways—encompassing urban fringe expansion, industry-city integration, in-situ urbanization, and the development of characteristic small towns—collectively aim to address the vulnerabilities and stagnation highlighted by the empirical analysis. The emphasis on industrial diversification within these models is particularly crucial for mitigating the “structural drag” of the dominant secondary sector and reducing the risks associated with a heavily labor-intensive economy. Concurrently, investments in local infrastructure and public services across these varied urbanizing landscapes directly target the qualitative aspects of urban-rural gaps and have the potential to enhance Wuan’s comprehensive urbanization index.

However, the success of these ambitious strategies hinges on several critical factors. Firstly, sustained industrial upgrading and diversification are paramount. This requires moving beyond merely enhancing the efficiency of existing industries to actively foster new, higher-value, and more resilient economic sectors. Attracting targeted investment, promoting innovation, and, crucially, developing a workforce equipped with the necessary skills for these new industries will be essential. Without a fundamental shift in the industrial structure, Wuan risks perpetuating its vulnerabilities.

Secondly, continuous policy innovation is necessary. This includes further reforms in the hukou (household registration) system to ensure the genuine social and economic integration of migrants, rather than just their physical presence in urban areas. Land-use policies must support rational urban expansion while also facilitating rural development and protecting agricultural land. Furthermore, innovative financial mechanisms are needed to channel capital effectively towards productive new ventures, rural revitalization projects, and essential public infrastructure, moving away from potentially inefficient allocations to traditional sectors.

Thirdly, human capital development stands out as a cornerstone for future progress. As Wuan endeavors to transform its industrial base and embrace more technologically advanced and service-oriented economic activities, the skills and adaptability of its workforce will be a key determinant of success. Significant and sustained investments in education at all levels, vocational training tailored to emerging industries, and opportunities for lifelong learning are critical to improve labor productivity, facilitate occupational mobility, and ensure that the benefits of economic transformation are broadly shared.

Fourthly, environmental sustainability must be deeply embedded within all urbanization pathways. Given Wuan’s history as a center for heavy industry, integrating green development principles—such as resource efficiency, pollution control, development of green infrastructure, and promotion of circular economy models—is vital for ensuring long-term livability and avoiding the environmental costs that have plagued similar industrial regions. A commitment to environmental quality will also positively influence the environmental dimension of the comprehensive urbanization index and enhance Wuan’s attractiveness.

If Wuan can successfully navigate these challenges and effectively implement its multi-pronged urbanization strategy, it has the potential to offer valuable lessons for other resource-based cities, both within China and internationally, that are facing similar transitions. The approach of balancing large city development with the invigoration of smaller towns and rural areas, integrating industrial requirements with community building, and urbanizing both new migrant populations and existing local residents in a coordinated manner, represents a sophisticated attempt at achieving balanced regional development.

Wuan City is at a critical juncture in its development trajectory. The empirical evidence reveals a period of significant past achievements followed by a slowdown, underscoring deep-seated structural challenges related to its industrial composition, labor-intensive growth model, and the complexities of ensuring equitable urban-rural development. The new urbanization pathways being pursued represent a comprehensive and ambitious response to these challenges. Their ultimate success will depend on a steadfast commitment to profound industrial transformation, robust investment in human capital, ongoing policy and institutional innovation, and an unwavering focus on improving the quality of life and well-being for all its residents. The journey from its current, relatively low comprehensive urbanization index value towards a higher, more stable, and qualitatively superior level of urban development will be the key indicator of Wuan’s successful transition to a more balanced, resilient, and people-centered urban future.

6. Conclusions

The case of Wuan City provides a compelling and instructive example of a resource-based, county-level city navigating the complex transition toward high-quality urbanization. The empirical analysis reveals that Wuan’s development was historically constrained by a development model characterized by a persistent urban-rural income gap, an economic structure reliant on traditional heavy industry (resource-mining), and an inefficient deployment of production factors. These underlying issues collectively contributed to a recent stagnation in the city’s overall urbanization progress, underscoring the limitations of its established growth paradigm.

In response, Wuan has embarked on a comprehensive transformation guided by the principle of “industrial transformation-driven new-type urbanization.” This strategic reorientation is multifaceted. Firstly, targeted rural development initiatives and the equalization of public services have significantly narrowed urban-rural income disparities, though the fragility of rural income sources remains a challenge. Secondly, industrial restructuring has begun to revitalize the economy. While the dominant secondary sector has demonstrated renewed competitiveness, it continues to exhibit a structural vulnerability due to its ongoing reliance on slower-growing traditional industries. The steady expansion of the service sector, however, provides a crucial engine for diversification and employment. Thirdly, the city’s economic mechanism is shifting away from an extensive, labor-intensive growth model toward an intensive one focused on enhancing capital efficiency and labor productivity through investments in technology and human capital.

These economic and social adjustments are operationalized through a set of holistic and spatially balanced urbanization strategies. The implementation of models for urban fringe development, in-situ urbanization of the existing rural populace, and the cultivation of specialized characteristic towns demonstrates a sophisticated approach to managing urban growth inclusively and sustainably. Collectively, these pathways illustrate an effective framework wherein industrial upgrading and urban development are mutually reinforcing.

However, while Wuan’s experience offers a valuable reference, it is not a universally applicable blueprint. The success of such a transition is contingent upon tailoring strategies to the unique resource endowments, economic conditions, and socio-cultural contexts of each locality. The fundamental lesson is the importance of identifying and leveraging local comparative advantages to select the most appropriate urbanization mode. A strategy effective for Wuan’s steel-based economy may require significant adaptation for a city reliant on coal, forestry, or other resources.

Furthermore, Wuan’s journey underscores that successful urbanization is critically dependent on institutional innovation and robust support systems. The implementation of policies related to land reform, innovative financing mechanisms, hukou system adjustments to integrate migrants, and the expansion of comprehensive social security networks are not merely ancillary but are essential enabling conditions. These institutional frameworks are crucial for unlocking the full benefits of urban growth and ensuring that the momentum remains equitable and people centered.

In conclusion, Wuan City’s experience offers a significant case study in resilient urbanization for policymakers and scholars in urban studies, regional planning, and economic geography. It demonstrates how a resource-dependent economy can proactively pivot towards a more sustainable and inclusive development path by intricately linking economic transformation with innovative urbanization policies. The strategies adopted in Wuan, with necessary local adaptations, hold considerable promise for other resource-based cities worldwide that are striving to achieve balanced, high-quality urban growth in an era of profound economic and environmental change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and D.Y.; methodology, J.H. and H.S.; software, J.H., H.S., and D.Y.; validation, D.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, J.H. and D.Y.; investigation, J.H.; resources, J.H. and D.Y.; data curation, J.H. and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H. and D.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.Y.; visualization, J.H. and D.Y.; supervision, D.Y.; project administration, J.H.; funding acquisition, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT 4o for the purposes of grammatic correction and wording. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fang, C.; Yu, D. China’s New Urbanization: Developmental Paths, Blueprints and Patterns; Science Press Jointly with Springer: Beijing, 2016.

- Perroux, F. Economic space: theory and applications. The quarterly journal of economics 1950, 64, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.P. A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. The American economic review 1969, 59, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, W.A. Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. 1954.

- Xiaotong, F. Small Towns: A Reexploration. Chinese Sociology & Anthropology 1989, 22, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yixing, Z. Urbanization Problems in China. Chinese Sociology & Anthropology 1987, 19, 14–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, F.; Yan, L.; Wang, D. The complexity for the resource-based cities in China on creating sustainable development. Cities 2020, 97, 102571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Zhou, T.; Wu, D. Shrinking cities and resource-based economy: The economic restructuring in China’s mining cities. Cities 2017, 60, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Zhang, X. Transformation effect of resource-based cities based on PSM-DID model: An empirical analysis from China. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2021, 91, 106648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cai, H. The impacts on regional “resource curse” by digital economy: Based on panel data analysis of 262 resource-based cities in China. Resources Policy 2024, 95, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Brouwer, R. Is China Affected by the Resource Curse? A Critical Review of the Chinese Literature. Journal of Policy Modeling 2020, 42, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Wang, D.; Meng, P.; Yang, J.; Pang, M.; Wang, L. Research on Resource Curse Effect of Resource-Dependent Cities: Case Study of Qingyang, Jinchang and Baiyin in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WU, K.; ZHANG, W.-z.; ZHANG, P.-y.; XUE, B.; AN, S.-w.; SHAO, S.; LONG, Y.; LIU, Y.-j.; TAO, A.-j.; HONG, H. High-quality development of resource-based cities in China: Dilemmas and breakthroughs. Journal of Natural Resources 2023, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.D.; Fang, C.L.; Wang, S.J.; Sun, S. The Effect of Economic Growth, Urbanization, and Industrialization on Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Concentrations in China. Environmental Science & Technology 2016, 50, 11452–11459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. The coupling curve between urbanization and the eco-environment: China’s urban agglomeration as a case study. Ecological Indicators 2021, 130, 108107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Du, J. The Impact of New Urbanization Construction on Sustainable Economic Growth of Resource-Based Cities. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 96860–96874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Yu, D.L.; Mao, H.Y.; Bao, C.; Huang, J.C. China’s Urban Pattern; Springer Jointly with Science Press: Beijing, 2018; p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.L.; Wei, Y.H.D. Analyzing regional inequality in post-Mao China in a GIS environment. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2003, 44, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, D.C. Shift-share analysis: further examination of models for the description of economic change. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2000, 34, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog Jr., H. W.; Olsen, R.J. SHIFT-SHARE ANALYSIS REVISITED: THE ALLOCATION EFFECT AND THE STABILITY OF REGIONAL STRUCTURE. J. Reg. Sci. 1977, 17, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, H.; Tian, Z.; Bei, J.; Zhang, H.; Ye, B.; Ni, J. A Method for Estimating Output Elasticity of Input Factors in Cobb-Douglas Production Function and Measuring Agricultural Technological Progress. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 26234–26250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Yu, D. Improvement of China’s regional economic efficiency under the gradient development strategy: A spatial econometric perspective. Social Science in China 2009, 20, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Lv, B. Challenging the Current Measurement of China’s Provincial Total Factor Productivity: A Spatial Econometric Perspective. China Soft Science 2009, 11, 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.L.; Yu, D.L. Urban agglomeration: An evolving concept of an emerging phenomenon. Landscape and Urban Planning 2017, 162, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.L.; Wang, Y.; Fang, J.W. A comprehensive assessment of urban vulnerability and its spatial differentiation in China. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2016, 26, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.L.; Wang, J. A Theoretical Analysis of Interactive Coercing Effects Between Urbanization and Eco-environment. Chinese Geographical Science 2013, 23, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, W.; Wang, J.; Wen, B.; Yang, D.; Jiang, S.; Wu, Y. Analysis on Decoupling between Urbanization Level and Urbanization Quality in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Wang, D. Comprehensive measures and improvement of Chinese urbanization development quality. Geographical research 2011, 30, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.; Yu, D. China’s Urban Agglomerations; Springer Nature Singapore: 2020.

Table 1.

Summary of Shift-Share Analysis Components for Wuan’s GDP by Sector (2014–2022).

Table 1.

Summary of Shift-Share Analysis Components for Wuan’s GDP by Sector (2014–2022).

| |

Component |

Key Trend/Observation |

| Primary |

Share |

Positive, steadily increasing |

| |

Structural |

Positive, grew slightly |

| |

Competitive |

Remained around zero or very small |

| Secondary |

Share |

Negative (2014-~2017), then positive and large (2018-2022) |

| |

Structural |

Mostly negative throughout the period |

| |

Competitive |

Became positive and significant in later years (post-2018) |

| Tertiary |

Share |

Positive, growing each year |

| |

Structural |

Positive |

| |

Competitive |

Became positive and grew in later years |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).