Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

What Are “Quantum Dots”?

Why Is Synthesis Important?

Size and Shape Control:

Optical Properties:

Surface Chemistry:

Stability and Scalability:

Toxicity and Environmental Concerns:

Objective of the Review

- Explaining the main ideas behind every synthetic approach.

- Observation of several synthetic methods by taking factors such as size control, mono-dispersity, yield, cost and environmental aspects into account.

- An explanation of modern direction in QD preparation along with the new methods inspired by green chemistry.

- Highlighting the problems in QD research and what future work could involve. Pointing out the challenges in the field and potential future directions for QD synthesis research.

Classification of “Quantum Dots”

Based upon Composition

Based upon Structure

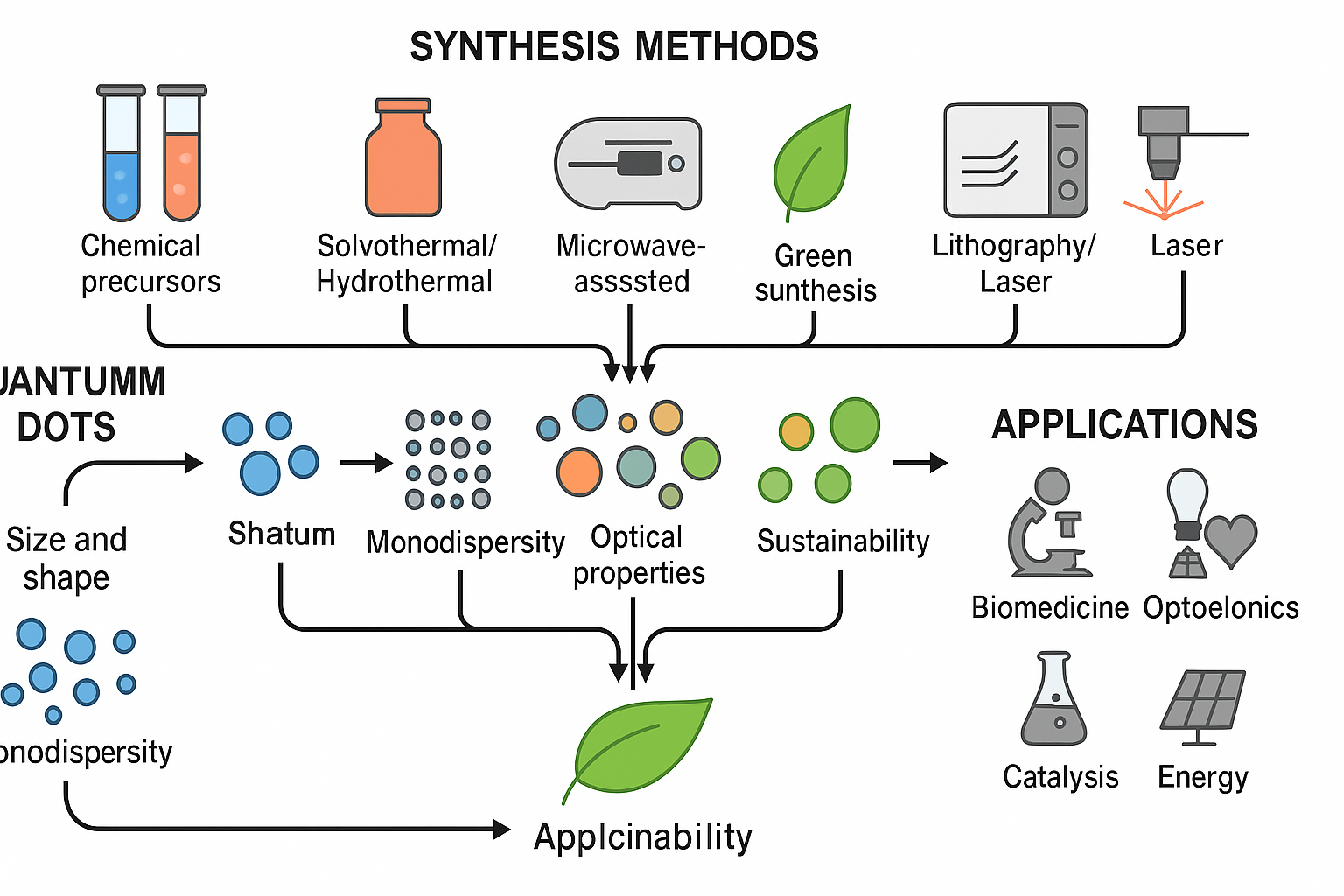

Synthetic Methods of “Quantum Dots”

Bottom-Up Approaches (Chemical Synthesis)

Colloidal Synthesis

- Principle and Mechanism: This method relies on adding QD precursors over a nucleation liquid to trigger the growth of QDs. You can achieve an accurate size of QDs by carefully managing temperature, the amount of precursors and the amount of time allocated to the reaction. The procedure results in size-related behavior of light particles. [46].

- Key Precursors and Solvents Used: Commonly, precursors are metal salts (such as CdCl2 and Pb(NO3)2), various chalcogens (Se, S and Te) and organic surfactants like trioctylphosphine oxide and oleic acid [47]. Common solvents for keeping colloidal dispersions stable are octadecene and toluene which are not polar [48].

- Control of QD Size & Monodispersity: Common solvents for keeping colloidal dispersions stable are octadecene and toluene which are not polar [49]. Rapid nucleation followed by slow growth results in forming uniform particle sizes, with improved monodispersity and optical performance of QDs.

-

Applications: Colloidal QDs are widely used in;

- ○

- biomedical imaging (as fluorescent markers),

- ○

- light-emitting diodes (LEDs) (for display technologies),

- ○

- solar cells (to enhance photovoltaic efficiency).

- Advantages and Disadvantages: Making QDs using the Colloidal method is simple, lets you adjust the size, produces high efficiency and is easily reproduced. Most of the time, these processes use harmful starting materials and very specific conditions must be used [50].

Solvothermal /Hydrothermal Synthesis

- Temperature and Reaction Time Dependency: How large and well-structured QDs become depends both on the reaction temperature and the duration chosen for the process. When the temperature is higher, the crystalline quality improves and continuing the reaction over time ensures all QDs grow uniformly [53].

- Applications: This approach is followed when high purity and surface control are needed, often found in perovskite solar cell applications and drug delivery [54].

- Pros and Cons: The solvothermal method provides high crystallinity and controlled morphology of QDs; although it is energy intensive and need high pressure equipment [46].

Microwave Assisted Synthesis

- Rapid Heating and Controlled Nucleation: The unique heating mechanism of microwaves allows for rapid, homogeneous heating. It decreases temperature gradients while ensuring uniform QD growth [56].

- Comparison with Traditional Methods: The process becomes more efficient and reproducible for QDs when microwave-assisted synthesis is used rather than older heating methods.

- Applications: Such materials are effective in biosensing fields (for example, for disease detection) and in catalysis (including for caring for the environment).

Green Synthesis (Eco Friendly Methods)

- Because of more attention on green products, people have created various biological and non-toxic methods to produce QDs.

- Exploiting Plant Extracts, Bacteria and Natural Biological Agents: Lots of natural materials are used to greenly produce and maintain QDs.

- Sustainable Alternatives to Toxic Solvents: True Solutions offer water-based processes and biodegradable stabilizers as healthy alternatives to normal organic solvents.

- Limitations and Scalability Issues: Synthesizing QDs using green methods often produces a low yield. It is not easy to reproduce because of its narrow scalability which restricts its use.

Top-Down Approaches (Physical Methods)

Lithography and Etching Methods

- Electron-beam lithography and ion-beam etching: To make the QDs ideal for optoelectronic applications, high resolution techniques that allow the precise patterning of QDs on substrate are Electron beam lithography and ion beam etching method.

- High Precision but High Cost: While methods offer excellent control over the QD size and arrangement, they are expensive and require sophisticated instrumentation.

Laser Ablation and Electrochemical Synthesis

- Production of “Quantum dots” from bulk materials: A high-energy laser beam is directly used to fragment bulk materials into nanoscale particles, such method is termed as Laser Ablation. Similarly, high voltage is applied to induce controlled “Quantum dots” to form solution medium. Such medium is termed as Electrochemical Synthesis of QDs.

- Advantages of Purity and Crystallinity: These methods give high-purity QDs with well-defined crystallinity and minimal contamination, making synthesized QDs for high performance optical and electronic applications.

Other Techniques (Mechanical Grinding, Ball Milling)

- Ball Milling: Using high-speed ball mills to crush a large amount of substance into nanoscale nanoparticles leads to an ongoing decrease in particle size.

- Limitations: Although it can be done at a low cost and in large quantities, these approaches lead to QDs with mixed sizes and numerous defects. Problems with QD shape can influence both their optical and electronic functions.

Comparative Analysis of Different Methods

- Size Control: It concerns the skill of perfectly controlling the shape of QDs.

- Monodispersity: Uniform distribution of particle size.

- Yield: It is the quantitative efficiency of production of QDs.

- Cost: To assess if each type of synthetic method is financially viable.

- Environmental Impact: So that QDs produced synthetically are environmentally friendly.

- Scalability: The possibility to make materials in large quantities.

|

Synthesis Method |

Size Control | Mono-dispersity | Yield | Cost | Environmental Impact | Scalability |

| Colloidal Synthesis | Excellent | High | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High |

|

Solvothermal/ Hydrothermal |

Good | Moderate | High | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Microwave-Assisted | Good | High | High | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Green Synthesis | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Very Low | Low |

| Lithography & Etching | High | Very High | Low | High | High | Very Low |

| Laser Ablation | High | High | Moderate | High | Moderate | Low |

| Ball Milling & Mechanical | Low | Low | High | Low | Moderate | High |

Discussion on Optimal Methods for Different Applications

Biomedical Applications

Optoelectronics

Catalysis

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Challenges in Synthesis

Toxicity Concerns

Scalability Issues in Industrial Production

Cost Effectiveness and Reproducibility

Future Research Directions

Emerging Green Synthesis Methods

Hybrid Synthetic Strategies Combining Both Bottom-Up and Top-Down Approaches

Potential for Biodegradable and Non-Toxic “Quantum Dots”

Conclusion

References

- L. Wang, D. Xu, J. Gao, X. Chen, Y. Duo, and H. Zhang, “Semiconducting quantum dots: Modification and applications in biomedical science,” Sci. China Mater., vol. 63, no. 9, pp. 1631–1650, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Reiss, M. Carrière, C. Lincheneau, L. Vaure, and S. Tamang, “Synthesis of Semiconductor Nanocrystals, Focusing on Nontoxic and Earth-Abundant Materials,” Chem. Rev., vol. 116, no. 18, pp. 10731–10819, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Chaparro Barriera and S. J. Bailón-Ruiz, “Fabrication, Characterization, and Nanotoxicity of Water stable Quantum Dots,” MRS Adv., vol. 5, no. 43, pp. 2231–2239, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pu, F. Cai, D. Wang, J.-X. Wang, and J.-F. Chen, “Colloidal Synthesis of Semiconductor Quantum Dots toward Large-Scale Production: A Review,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1790–1802, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Iravani and R. S. Varma, “Green synthesis, biomedical and biotechnological applications of carbon and graphene quantum dots. A review,” Environ. Chem. Lett., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 703–727, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. X. Soares et al., “Rationally designed synthesis of bright AgInS2/ZnS quantum dots with emission control,” Nano Res., vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 2438–2450, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Kargozar, S. J. Hoseini, P. B. Milan, S. Hooshmand, H. Kim, and M. Mozafari, “Quantum Dots: A Review from Concept to Clinic,” Biotechnol. J., vol. 15, no. 12, p. 2000117, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M.-X. Zhao and E.-Z. Zeng, “Application of functional quantum dot nanoparticles as fluorescence probes in cell labeling and tumor diagnostic imaging,” Nanoscale Res. Lett., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 171, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Bajwa, N. K. Mehra, K. Jain, and N. K. Jain, “Pharmaceutical and biomedical applications of quantum dots,” Artif. Cells Nanomedicine Biotechnol., pp. 1–11, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shu, X. Lin, H. Qin, Z. Hu, Y. Jin, and X. Peng, “Quantum Dots for Display Applications,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., vol. 59, no. 50, pp. 22312–22323, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wan et al., “Ultrathin Light-Emitting Diodes with External Efficiency over 26% Based on Resurfaced Perovskite Nanocrystals,” ACS Energy Lett., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 927–934, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Koutsogiannis, E. Thomou, H. Stamatis, D. Gournis, and P. Rudolf, “Advances in fluorescent carbon dots for biomedical applications,” Adv. Phys. X, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 1758592, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kausar, “Polymer dots and derived hybrid nanomaterials: A review,” J. Plast. Film Sheeting, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 510–528, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Alizadeh-Ghodsi, M. Pourhassan-Moghaddam, A. Zavari-Nematabad, B. Walker, N. Annabi, and A. Akbarzadeh, “State-of-the-Art and Trends in Synthesis, Properties, and Application of Quantum Dots-Based Nanomaterials,” Part. Part. Syst. Charact., vol. 36, no. 2, p. 1800302, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Slejko and V. Lughi, “Size Control at Maximum Yield and Growth Kinetics of Colloidal II–VI Semiconductor Nanocrystals,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 123, no. 2, pp. 1421–1428, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Dey and S. S. Nath, “SIZE-DEPENDENT PHOTOLUMINESCENCE AND ELECTROLUMINESCENCE OF COLLOIDAL CdSe QUANTUM DOTS,” Int. J. Nanosci., vol. 12, no. 02, p. 1350013, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Tsekov, P. Georgiev, S. Simeonova, and K. Balashev, “Quantifying the Blue Shift in the Light Absorption of Small Gold Nanoparticles,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. X. Xu, Y. Yuan, M. Liu, S. Zou, O. Chen, and D. Zhang, “Quantification of the Photon Absorption, Scattering, and On-Resonance Emission Properties of CdSe/CdS Core/Shell Quantum Dots: Effect of Shell Geometry and Volumes,” Anal. Chem., vol. 92, no. 7, pp. 5346–5353, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Perikala and A. Bhardwaj, “Engineering Photo-Luminescent Centers of Carbon Dots to Achieve Higher Quantum Yields,” ACS Appl. Electron. Mater., vol. 2, no. 8, pp. 2470–2478, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Huang, Z. Ye, L. Yang, J. Li, H. Qin, and X. Peng, “Synthesis of Colloidal Quantum Dots with an Ultranarrow Photoluminescence Peak,” Chem. Mater., vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 1799–1810, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu, H. Xu, B. Shen, and X. Zhong, “High-Quality Water-Soluble Core/Shell/Shell CdSe/CdS/ZnS Quantum Dots Balanced by Ionic and Nonionic Hydrophilic Capping Ligands,” Nano, vol. 11, no. 07, p. 1650073, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yan, Y. Cai, X. Liu, G. Ma, W. Lv, and M. Wang, “Hydrophobic Modification on the Surface of SiO2 Nanoparticle: Wettability Control,” Langmuir, vol. 36, no. 49, pp. 14924–14932, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Jo, H. S. Heo, and K. Lee, “Assessing Stability of Nanocomposites Containing Quantum Dot/Silica Hybrid Particles with Different Morphologies at High Temperature and Humidity,” Chem. Mater., vol. 32, no. 24, pp. 10538–10544, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Jin, C. Wu, S. Zhou, Y. Xin, T. Sun, and C. Guo, “Practical and Scalable Manufacturing Process for a Novel Dual-Acting Serotonergic Antidepressant Vilazodone,” Org. Process Res. Dev., vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 1184–1189, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Nikazar, V. S. Sivasankarapillai, A. Rahdar, S. Gasmi, P. S. Anumol, and M. S. Shanavas, “Revisiting the cytotoxicity of quantum dots: an in-depth overview,” Biophys. Rev., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 703–718, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhu, D. Shen, C. Wu, and S. Gu, “State-of-the-Art on the Preparation, Modification, and Application of Biomass-Derived Carbon Quantum Dots,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 59, no. 51, pp. 22017–22039, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh et al., “Quantum dots: synthesis, bioapplications, and toxicity,” Nanoscale Res. Lett., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 480, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. Li, and F. Wang, “InP Quantum Dots: Synthesis and Lighting Applications,” Small, vol. 16, no. 32, p. 2002454, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhou et al., “Bandgap Tuning of Silicon Quantum Dots by Surface Functionalization with Conjugated Organic Groups,” Nano Lett., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 3657–3663, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhou et al., “Bandgap Tuning of Silicon Quantum Dots by Surface Functionalization with Conjugated Organic Groups,” Nano Lett., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 3657–3663, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Niezgoda, M. A. Harrison, J. R. McBride, and S. J. Rosenthal, “Novel Synthesis of Chalcopyrite CuxInyS2 Quantum Dots with Tunable Localized Surface Plasmon Resonances,” Chem. Mater., vol. 24, no. 16, pp. 3294–3298, Aug. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, R. Li, and B. Yang, “Carbon Dots: A New Type of Carbon-Based Nanomaterial with Wide Applications,” ACS Cent. Sci., vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 2179–2195, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Liang, W. Liu, X. Liu, Y. Li, W. Wu, and J. Fan, “In Situ Phase-Transition Crystallization of All-Inorganic Water-Resistant Exciton-Radiative Heteroepitaxial CsPbBr3-CsPb2Br5 Core-Shell Perovskite Nanocrystals,” Chem. Mater., vol. 33, no. 13, pp. 4948–4959, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Ji, S. Koley, I. Slobodkin, S. Remennik, and U. Banin, “ZnSe/ZnS Core/Shell Quantum Dots with Superior Optical Properties through Thermodynamic Shell Growth,” Nano Lett., vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 2387–2395, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang et al., “An Aqueous Route Synthesis of Transition-Metal-Ions-Doped Quantum Dots by Bimetallic Cluster Building Blocks,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 142, no. 38, pp. 16177–16181, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Dey, S. Chen, S. Thota, M. R. Shakil, S. L. Suib, and J. Zhao, “Effect of Gradient Alloying on Photoluminescence Blinking of Single CdSxSe 1– x Nanocrystals,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 120, no. 37, pp. 20547–20554, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cheng et al., “Continuously Graded Quantum Dots: Synthesis, Applications in Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes, and Perspectives,” J. Phys. Chem. Lett., vol. 12, no. 25, pp. 5967–5978, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Kaiming, L. Baoyou, H. Ju, R. Hongwei, W. Limin, and Y. Gang, “Green preparation and application of carbon quantum dots,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 826, no. 1, p. 012036, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Tour, “Top-Down versus Bottom-Up Fabrication of Graphene-Based Electronics,” Chem. Mater., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 163–171, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Lanyon and D. W. M. Arrigan, “Top-Down Approaches to the Fabrication of Nanopatterned Electrodes,” in Nanostructured Materials in Electrochemistry, 1st ed., A. Eftekhari, Ed., Wiley, 2008, pp. 187–210. [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Hu and T. Zhu, “Semiconductor Nanocrystal Quantum Dot Synthesis Approaches Towards Large-Scale Industrial Production for Energy Applications,” Nanoscale Res. Lett., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 469, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Van Embden, A. S. R. Chesman, and J. J. Jasieniak, “The Heat-Up Synthesis of Colloidal Nanocrystals,” Chem. Mater., vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 2246–2285, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Yang, L. Tang, Q. Li, A. Bai, Y. Wang, and Y. Yu, “Preparation of Monodisperse Colloidal ZnO Nanoparticles and their Optical Properties,” Nano, vol. 10, no. 05, p. 1550074, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Li et al., “Fragmentation of Magic-Size Cluster Precursor Compounds into Ultrasmall CdS Quantum Dots with Enhanced Particle Yield at Low Temperatures,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., vol. 59, no. 29, pp. 12013–12021, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, R. W. Crisp, J. Gao, D. M. Kroupa, M. C. Beard, and J. M. Luther, “Synthetic Conditions for High-Accuracy Size Control of PbS Quantum Dots,” J. Phys. Chem. Lett., vol. 6, no. 10, pp. 1830–1833, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- C.-D. Kim, H. T. Kim, B.-K. Min, and C. Park, “Effects of Growth Temperature on the Properties of CdSe Nano-Crystals Synthesized Eco-Friendly Using Colloidal Route,” Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst., vol. 602, no. 1, pp. 151–158, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Van Embden, A. S. R. Chesman, and J. J. Jasieniak, “The Heat-Up Synthesis of Colloidal Nanocrystals,” Chem. Mater., vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 2246–2285, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Bera, D. Mandal, P. N. Goswami, A. K. Rath, and B. L. V. Prasad, “Generic and Scalable Method for the Preparation of Monodispersed Metal Sulfide Nanocrystals with Tunable Optical Properties,” Langmuir, vol. 34, no. 20, pp. 5788–5797, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Lv, J. Li, Y. Wang, Y. Shu, and X. Peng, “Monodisperse CdSe Quantum Dots Encased in Six (100) Facets via Ligand-Controlled Nucleation and Growth,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 142, no. 47, pp. 19926–19935, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Alizadeh-Ghodsi, M. Pourhassan-Moghaddam, A. Zavari-Nematabad, B. Walker, N. Annabi, and A. Akbarzadeh, “State-of-the-Art and Trends in Synthesis, Properties, and Application of Quantum Dots-Based Nanomaterials,” Part. Part. Syst. Charact., vol. 36, no. 2, p. 1800302, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Van Embden, A. S. R. Chesman, and J. J. Jasieniak, “The Heat-Up Synthesis of Colloidal Nanocrystals,” Chem. Mater., vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 2246–2285, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, R. W. Crisp, J. Gao, D. M. Kroupa, M. C. Beard, and J. M. Luther, “Synthetic Conditions for High-Accuracy Size Control of PbS Quantum Dots,” J. Phys. Chem. Lett., vol. 6, no. 10, pp. 1830–1833, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Chen, X. Zhang, Y. Zhao, and Q. Zhang, “Effects of reaction temperature on size and optical properties of CdSe nanocrystals,” Bull. Mater. Sci., vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 547–552, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. Maghsoudi, M. Mahboub, and S. Asgari, “Processing and characterization of monodisperse phosphine-free CdSe colloidal quantum dots,” presented at the SPIE NanoScience + Engineering, E. M. Campo, E. A. Dobisz, and L. A. Eldada, Eds., San Diego, California, United States, Aug. 2014, p. 91701J. [CrossRef]

- W. Schumacher, A. Nagy, W. J. Waldman, and P. K. Dutta, “Direct Synthesis of Aqueous CdSe/ZnS-Based Quantum Dots Using Microwave Irradiation,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 113, no. 28, pp. 12132–12139, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- H.-Q. Wang and T. Nann, “Monodisperse Upconverting Nanocrystals by Microwave-Assisted Synthesis,” ACS Nano, vol. 3, no. 11, pp. 3804–3808, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Nikazar, V. S. Sivasankarapillai, A. Rahdar, S. Gasmi, P. S. Anumol, and M. S. Shanavas, “Revisiting the cytotoxicity of quantum dots: an in-depth overview,” Biophys. Rev., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 703–718, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Ali, E. Khan, and I. Ilahi, “Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology of Hazardous Heavy Metals: Environmental Persistence, Toxicity, and Bioaccumulation,” J. Chem., vol. 2019, pp. 1–14, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu, S. J. Cobbina, G. Mao, H. Xu, Z. Zhang, and L. Yang, “A review of toxicity and mechanisms of individual and mixtures of heavy metals in the environment,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 8244–8259, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, M. Zhang, B. Bhandari, and C. Yang, “Recent Development of Carbon Quantum Dots: Biological Toxicity, Antibacterial Properties and Application in Foods,” Food Rev. Int., vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 1513–1532, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Shakeri and R. W. Meulenberg, “A Closer Look into the Traditional Purification Process of CdSe Semiconductor Quantum Dots,” Langmuir, vol. 31, no. 49, pp. 13433–13440, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Kapoor, A. Jha, H. Ahmad, and S. S. Islam, “Avenue to Large-Scale Production of Graphene Quantum Dots from High-Purity Graphene Sheets Using Laboratory-Grade Graphite Electrodes,” ACS Omega, vol. 5, no. 30, pp. 18831–18841, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Shaik, S. Sengupta, R. S. Varma, M. B. Gawande, and A. Goswami, “Syntheses of N-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots (NCQDs) from Bioderived Precursors: A Timely Update,” ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 3–49, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Arshad, M. P. Sk, S. K. Maurya, and H. R. Siddique, “Mechanochemical Synthesis of Sulfur Quantum Dots for Cellular Imaging,” ACS Appl. Nano Mater., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 3339–3344, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, R. W. Crisp, J. Gao, D. M. Kroupa, M. C. Beard, and J. M. Luther, “Synthetic Conditions for High-Accuracy Size Control of PbS Quantum Dots,” J. Phys. Chem. Lett., vol. 6, no. 10, pp. 1830–1833, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Xie, E. Chen, Y. Ye, S. Xu, and T. Guo, “Highly Stabilized Gradient Alloy Quantum Dots and Silica Hybrid Nanospheres by Core Double Shells for Photoluminescence Devices,” J. Phys. Chem. Lett., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1428–1434, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, M. Zhang, B. Bhandari, and C. Yang, “Recent Development of Carbon Quantum Dots: Biological Toxicity, Antibacterial Properties and Application in Foods,” Food Rev. Int., vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 1513–1532, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhu, D. Shen, C. Wu, and S. Gu, “State-of-the-Art on the Preparation, Modification, and Application of Biomass-Derived Carbon Quantum Dots,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 59, no. 51, pp. 22017–22039, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Wu, Y. Li, W. Ding, L. Xu, Y. Ma, and L. Zhang, “Recent Advances of Persistent Luminescence Nanoparticles in Bioapplications,” Nano-Micro Lett., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 70, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Cárdenas-Triviño and S. Triviño-Matus, “Synthesis and characterization of Fe, Co, and Ni colloids in 2-mercaptoethanol,” Nanomater. Nanotechnol., vol. 10, p. 184798042096688, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Devaraju and I. Honma, “Hydrothermal and Solvothermal Process Towards Development of LiMPO4 (M = Fe, Mn) Nanomaterials for Lithium-Ion Batteries,” Adv. Energy Mater., vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 284–297, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- T.-T. Xuan, J.-Q. Liu, R.-J. Xie, H.-L. Li, and Z. Sun, “Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of CdS/ZnS:Cu Quantum Dots for White Light-Emitting Diodes with High Color Rendition,” Chem. Mater., vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 1187–1193, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Yadav et al., “Green Synthesis of Fluorescent Carbon Quantum Dots from Azadirachta indica Leaves and Their Peroxidase-Mimetic Activity for the Detection of H2 O2 and Ascorbic Acid in Common Fresh Fruits,” ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 623–632, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Venkatesan, J. Sundarababu, and S. S. Anandan, “The recent developments of green and sustainable chemistry in multidimensional way: current trends and challenges,” Green Chem. Lett. Rev., vol. 17, no. 1, p. 2312848, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Najeeb, S. Naeem, M. F. Nazar, K. Naseem, and U. Shehzad, “Green Chemistry: Evolution in Architecting Schemes for Perfecting the Synthesis Methodology of the Functionalized Nanomaterials,” ChemistrySelect, vol. 6, no. 13, pp. 3101–3116, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Kim, D. Kim, Y. Choi, A. Ghorai, G. Park, and U. Jeong, “New Approaches to Produce Large-Area Single Crystal Thin Films,” Adv. Mater., vol. 35, no. 4, p. 2203373, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Tungare, M. Bhori, K. S. Racherla, and S. Sawant, “Synthesis, characterization and biocompatibility studies of carbon quantum dots from Phoenix dactylifera,” 3 Biotech, vol. 10, no. 12, p. 540, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Prodanov, S. K. Gupta, C. Kang, M. Y. Diakov, V. V. Vashchenko, and A. K. Srivastava, “Thermally Stable Quantum Rods, Covering Full Visible Range for Display and Lighting Application,” Small, vol. 17, no. 3, p. 2004487, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Meng, H. Fan, J. M. D. Lane, and Y. Qin, “Bottom-Up Approaches for Precisely Nanostructuring Hybrid Organic/Inorganic Multi-Component Composites for Organic Photovoltaics,” MRS Adv., vol. 5, no. 40–41, pp. 2055–2065, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Kaiming, L. Baoyou, H. Ju, R. Hongwei, W. Limin, and Y. Gang, “Green preparation and application of carbon quantum dots,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 826, no. 1, p. 012036, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Kagan, L. C. Bassett, C. B. Murray, and S. M. Thompson, “Colloidal Quantum Dots as Platforms for Quantum Information Science,” Chem. Rev., vol. 121, no. 5, pp. 3186–3233, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).