5.1. Overall Performance Analysis

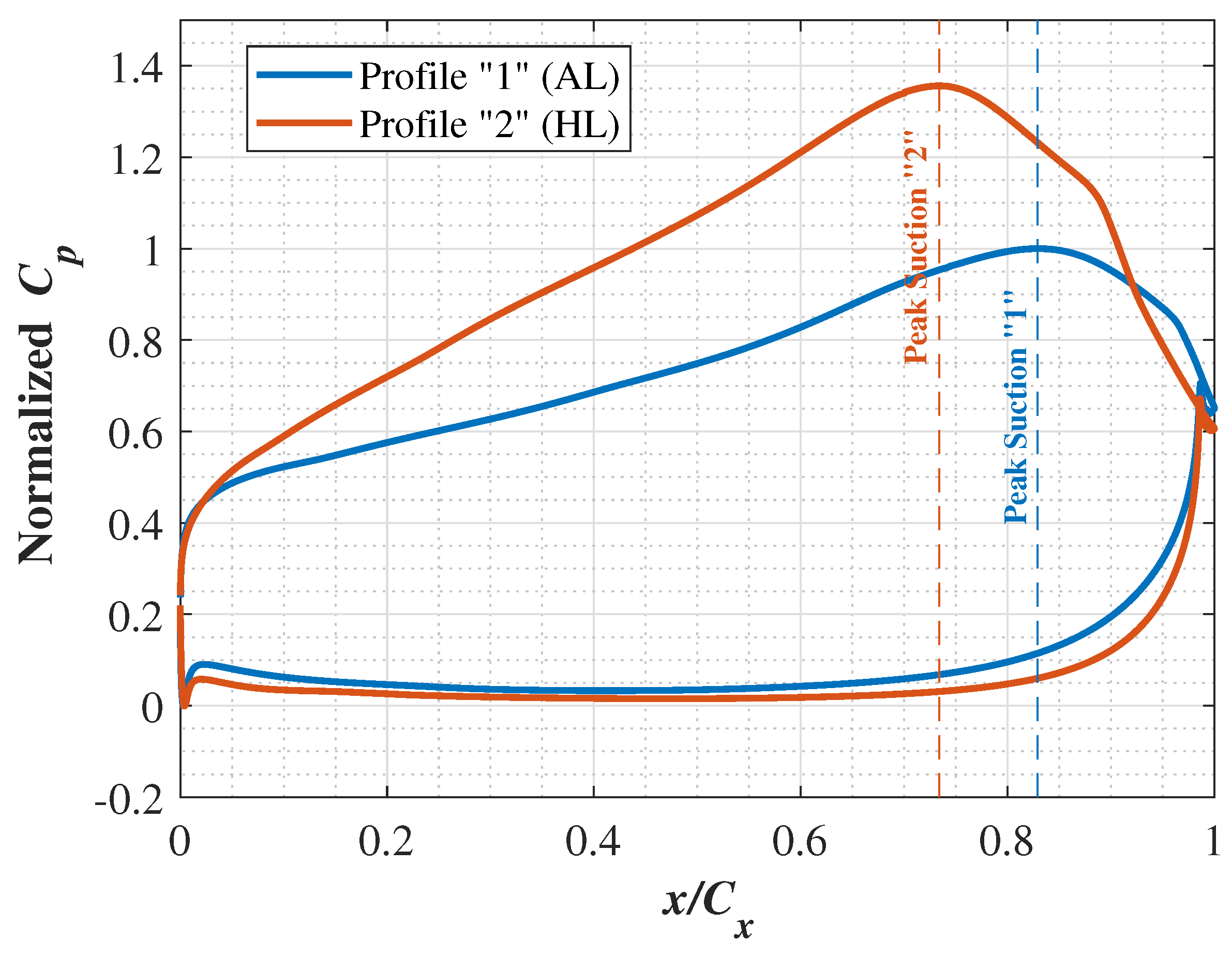

Figure 6 illustrates the time-averaged pressure coefficient (

) normalized with the peak suction value of profile "1", as a function of the dimensionless axial coordinate, for the two analyzed cascades. The pressure coefficient is defined as follows:

where the subscript "

t" denotes that the variable is calculated at the stagnation point, while the subscripts "1" and "2" indicate the upstream and downstream sections of the computational domain, respectively.

As can be observed in

Figure 6, profile "1" is a strongly aft-loaded profile, with the peak suction position located at 83% of the axial chord. On the other hand, profile "2", albeit still aft-loaded, exhibits a peak suction location that is shifted closer to the leading edge, occurring at 74% of the axial chord. Moreover, profile "2" has a higher loading. Based on these considerations, profiles "1" and "2" will be referred to as Aft-Loaded (AL) and High-Loaded (HL) profile, respectively. The upstream shift of the point of maximum flow velocity for the HL profile allows for a more gradual deceleration in the rear portion of the suction side: despite a higher overall diffusion, a 10% reduction in local diffusion rate with respect to the AL profile is observed, with the blue curve having a greater maximum negative slope than the red curve near the trailing edge. Furthermore, the higher loading of the HL profile allows for a greater flow acceleration in the front part of the suction side.

The global loss coefficient, defined as the normalized inlet-outlet difference in area-averaged total pressure, was computed from LES data to validate the results obtained from the approach introduced in

Section 3. The isoentropic downstream velocity-based dynamic pressure was selected as the normalization factor. Despite having a higher blade loading, the HL profile is more efficient than the AL profile, the latter exhibiting a loss coefficient approximately 15% higher.

A POD-based post-processing procedure, analogous to the one presented in [

21], has been adopted to identify the main viscous and turbulent phenomena that differentiate the performance of the two profiles.

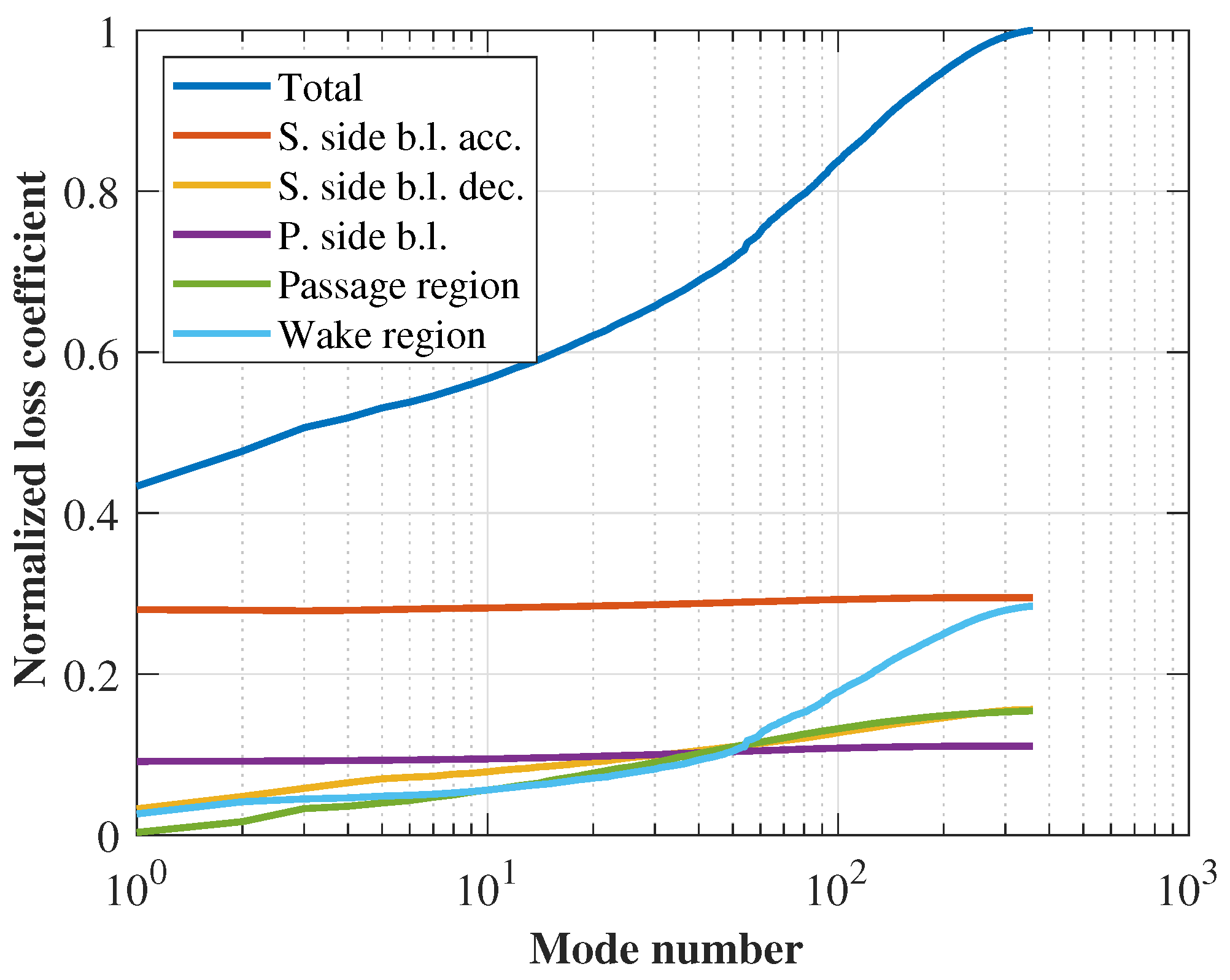

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the cumulative distributions of the loss coefficients, in both cases normalized with the global loss coefficient of the AL profile. These curves were obtained by integrating the right-hand side terms of Equation (

6). These terms have been decomposed in the POD framework, as outlined in

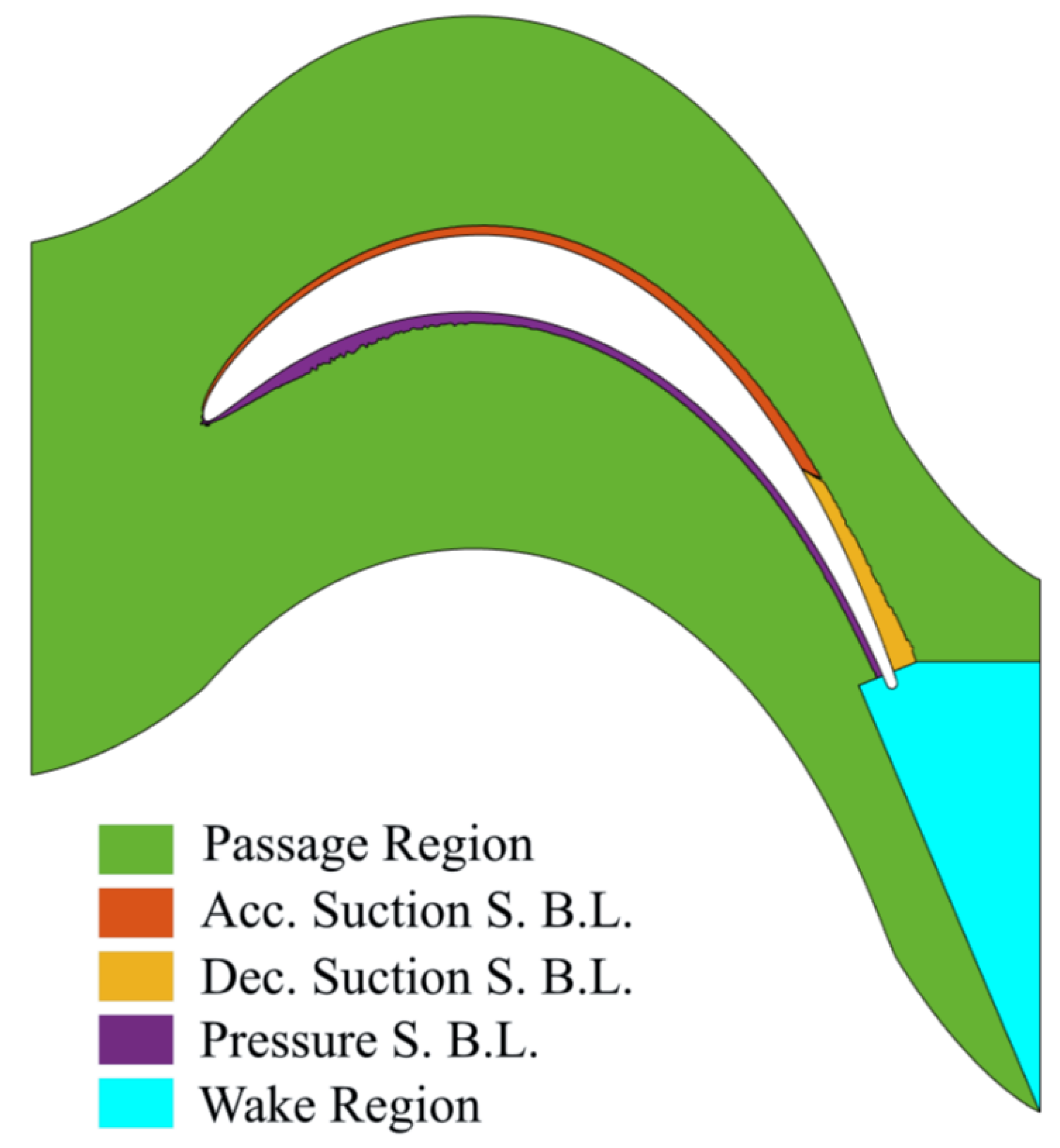

Section 4, and then integrated over the different flow regions of the computational domain depicted in

Figure 5. In these plots the mean flow viscous dissipation is reported as the baseline loss level cutting the ordinate axis, since it cannot be POD decomposed (i.e. it is related only to mean flow properties), while the contribution of each mode to the remaining

term has been cumulatively summed. As expected, both the profiles feature viscous losses mainly concentrated in the blade boundary layer.

Specifically, for the AL profile (

Figure 7), the extended accelerated front section of the profile results in significant viscous losses in the accelerating suction side boundary layer (red curve). In this region, as well as in the pressure side boundary layer (violet curve), turbulent structures identified by POD modes do not produce additional losses, as the boundary layers in these portions of the blade remain in a laminar state. This is reflected in the curves showing minimal dependence on mode order (curves are horizontal). In contrast, turbulence-induced losses are more pronounced in the rear part of the suction side where flow diffusion and BL transition occur. In fact, in this area, the contribution to losses increases with mode number (yellow curve). Additionally, considerable losses are observed in the wake region (cyan curve) downstream of the trailing edge. This is due to the intense vortex shedding and related break-up process in the wake, which stems from the strong deceleration of the flow in the rear suction side, where the local diffusion rate reaches very high values. Finally, turbulent production in the core flow region significantly contributes to the total losses (green curve). Both the incoming wake-related modes (i.e. the first modes) and finer scale structures (i.e. higher order modes) induce losses within the passage. This effect is likely due to the moderate acceleration imposed by the blade loading in the early part of the vane passage. As shown in Simoni et al. [

31], the insufficient flow acceleration in the initial portion of the blade does not inhibit turbulent production caused by wake bowing and tilting processes. This ultimately leads to an increase in total pressure losses.

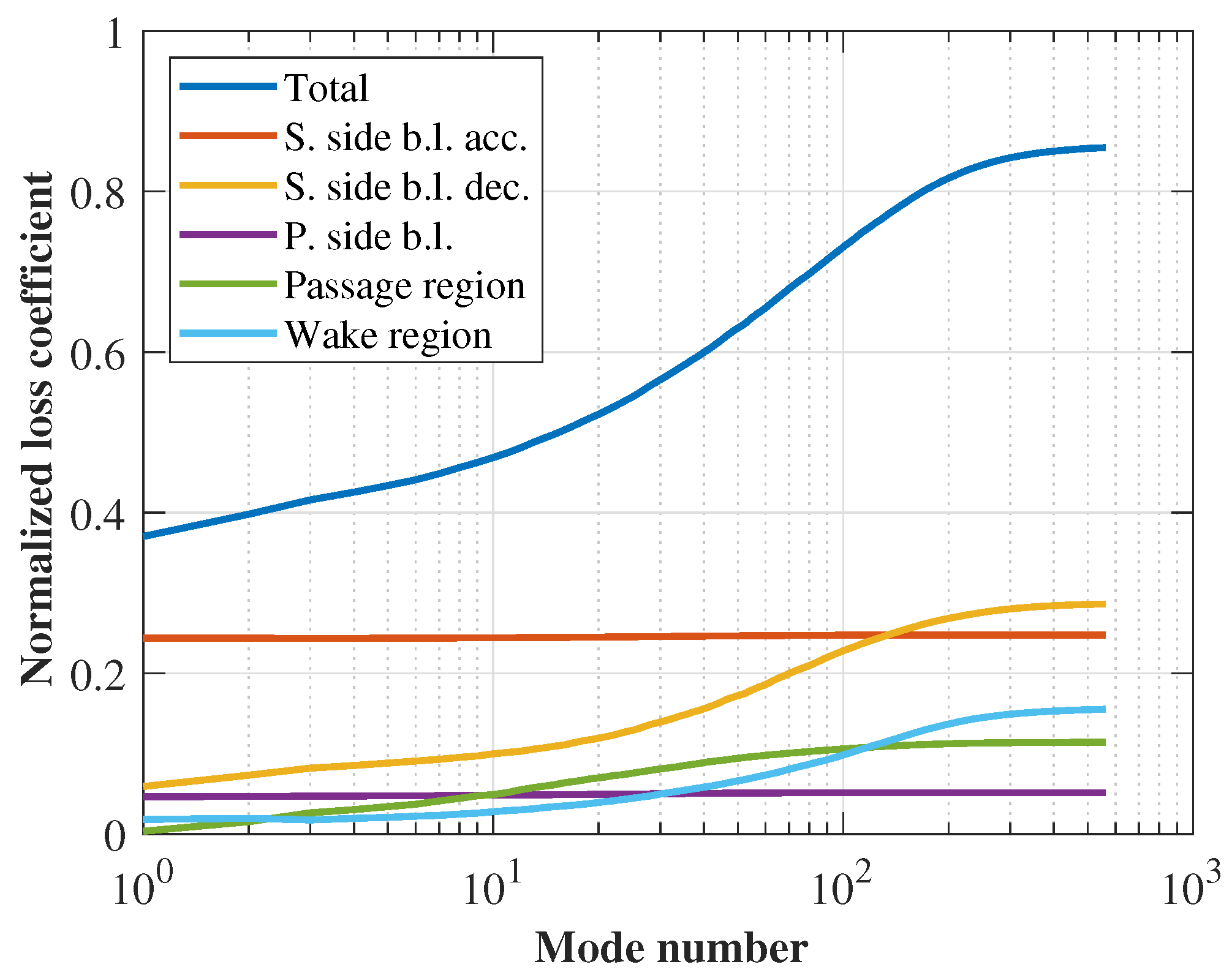

Referring now to the HL profile (

Figure 8), the cumulative curves of total dissipation show a significant improvement in overall performance with respect to the AL profile. The overall loss (blue curve for the entire set of modes) is approximately 85% of the AL profile value. The most significant contribution to loss production comes from the decelerating suction side region (yellow curve). Losses due to wake migration into the passage region (green curve) are also reduced, thanks to the increased acceleration imposed on the flow by the blade loading. Similarly, viscous dissipation in the accelerating part of the suction side boundary layer (red curve) is lower with respect to the AL profile.

All of this information enhances our understanding of the mechanisms leading to loss generation. A deeper insight can be obtained by examining the phase of the wake passing cycle during which losses are produced.

5.2. Loss Distribution Within Wake Passing Cycle

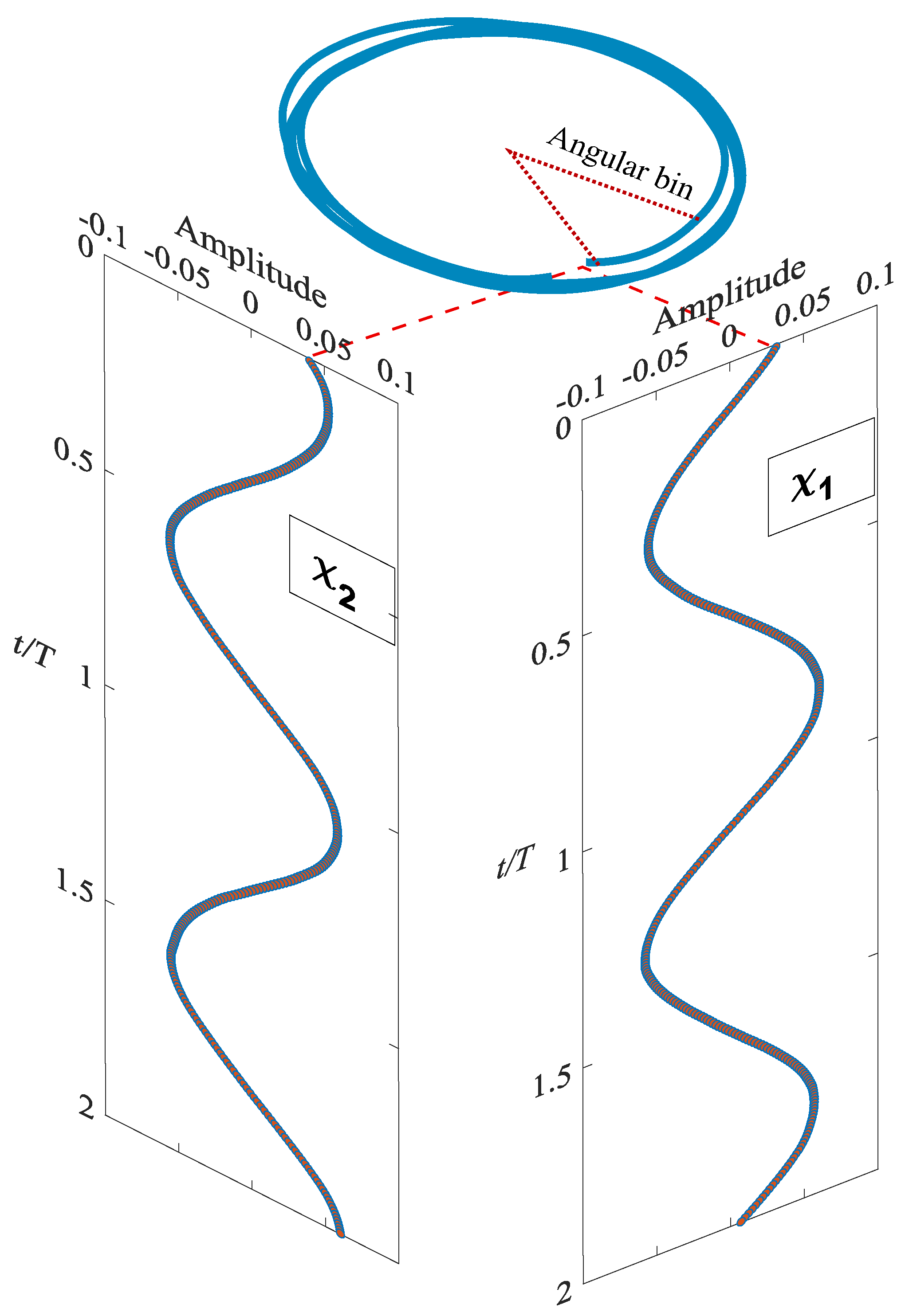

As described in

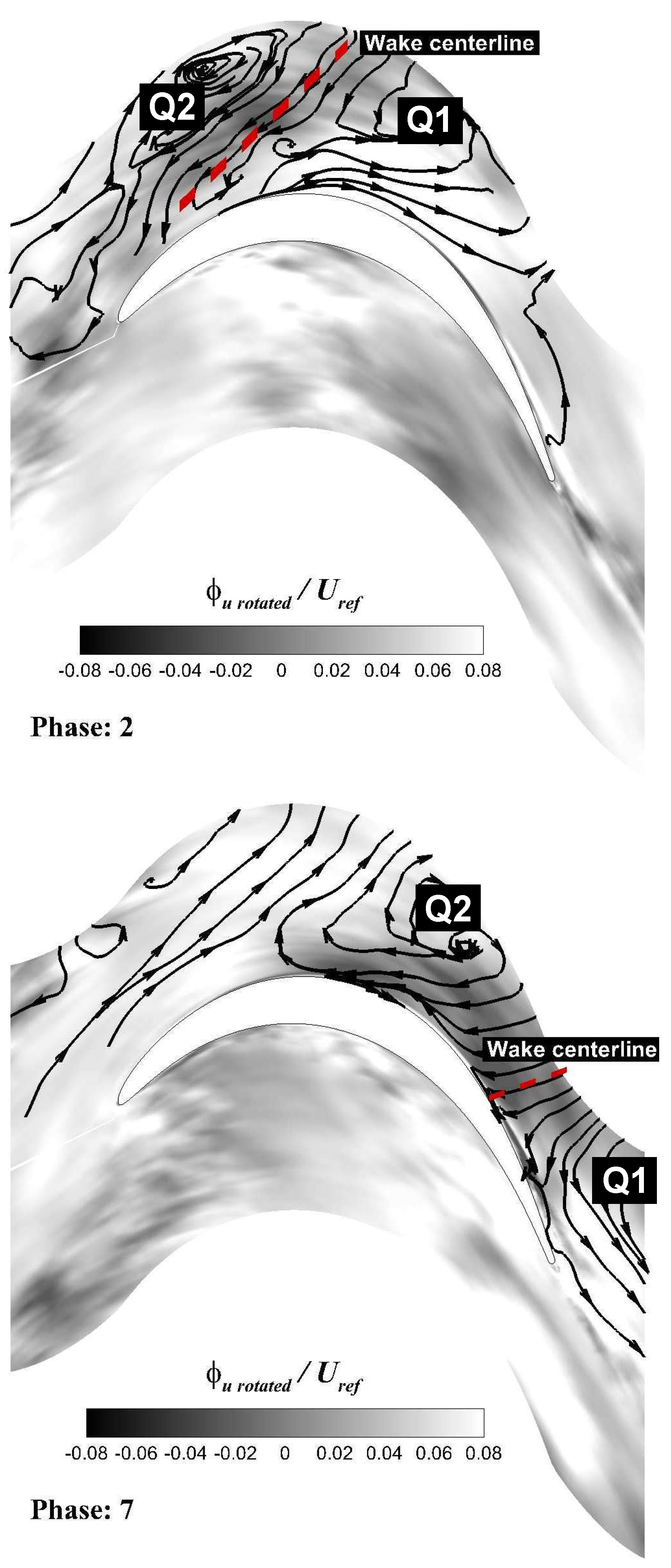

Section 4, the application of the PPOD procedure results in a modal decomposition of the flow dynamics for a given position of the wake within the inter-blade channel. For instance,

Figure 9 shows the contour plots of the HL profile’s first PPOD mode for the stream-parallel velocity component

, normalized with

, for two different phases capturing the migration of the upstream wake along the blade suction side. Mode streamlines are overlaid on the plots for the portion of the channel above the suction side. As can be observed, the first mode of each phase provides a filtered (or phase-averaged) view of the flow field for each relative position of the wake (wake centerline is schematically represented by a red dashed line).

The figure illustrates the temporal evolution of the main large scale coherent structures generated by the relative motion of the wake within the inter-blade passage from phase 2 to phase 7. Streamlines highlight the formation of the so-called "negative-jet" structure, emphasized by the strongly negative streamwise velocity zone (dark gray flood in the contour plots). The momentum transfer associated with the wake velocity defect generates a jet which, around the wake centerline, directs toward the blade suction side. This jet splits into two branches, forming two distinct large-scale counter-rotating vortices at the leading and trailing edges of the wake, as known from previous literature results. In the figure, these structures are referred to as "Q1" and "Q2" vortices. The negative jet is known to play a key role in the mechanism of wake-induced boundary layer transition. As the wake convects over the boundary layer separation point, the wall-normal component of the negative jet distorts the shear layer, which is inherently unstable. This interaction triggers an inviscid Kelvin-Helmholtz roll-up, where the resulting vortex moves at half the freestream velocity. The wake, traveling at the freestream speed, advances ahead of the roll-up and further disturbs the separated shear layer downstream, leading to the formation of additional roll-up vortices that quickly break down into turbulence.

To identify the phases of the wake passage cycle during which these wake-related events induce the largest losses, we analyze the contribution to losses limited to the production of TKE (

) by defining a loss coefficient

. This coefficient was calculated by integrating, at a fixed phase, the term

from equation

6 across the five different sub-regions of the computational domain.

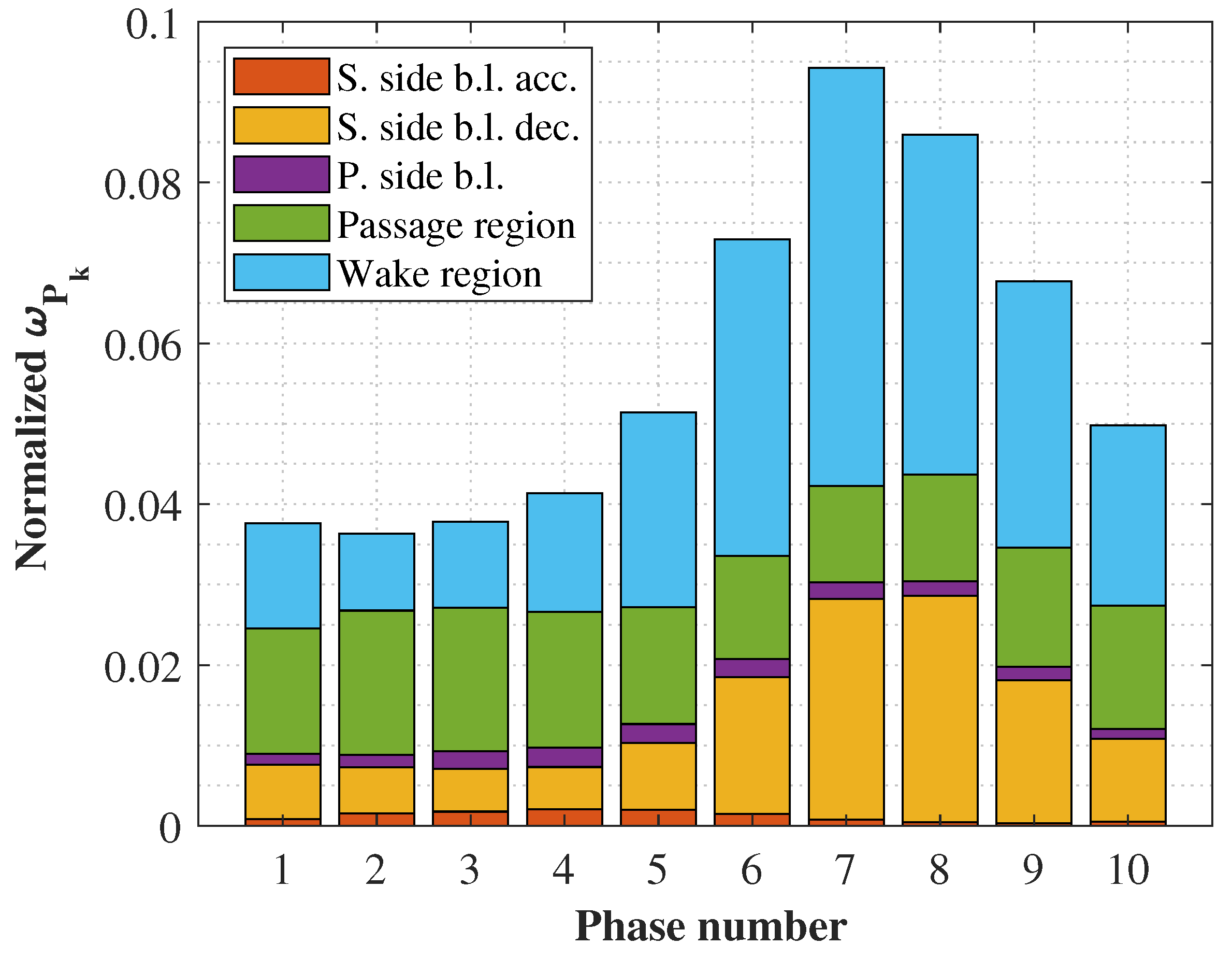

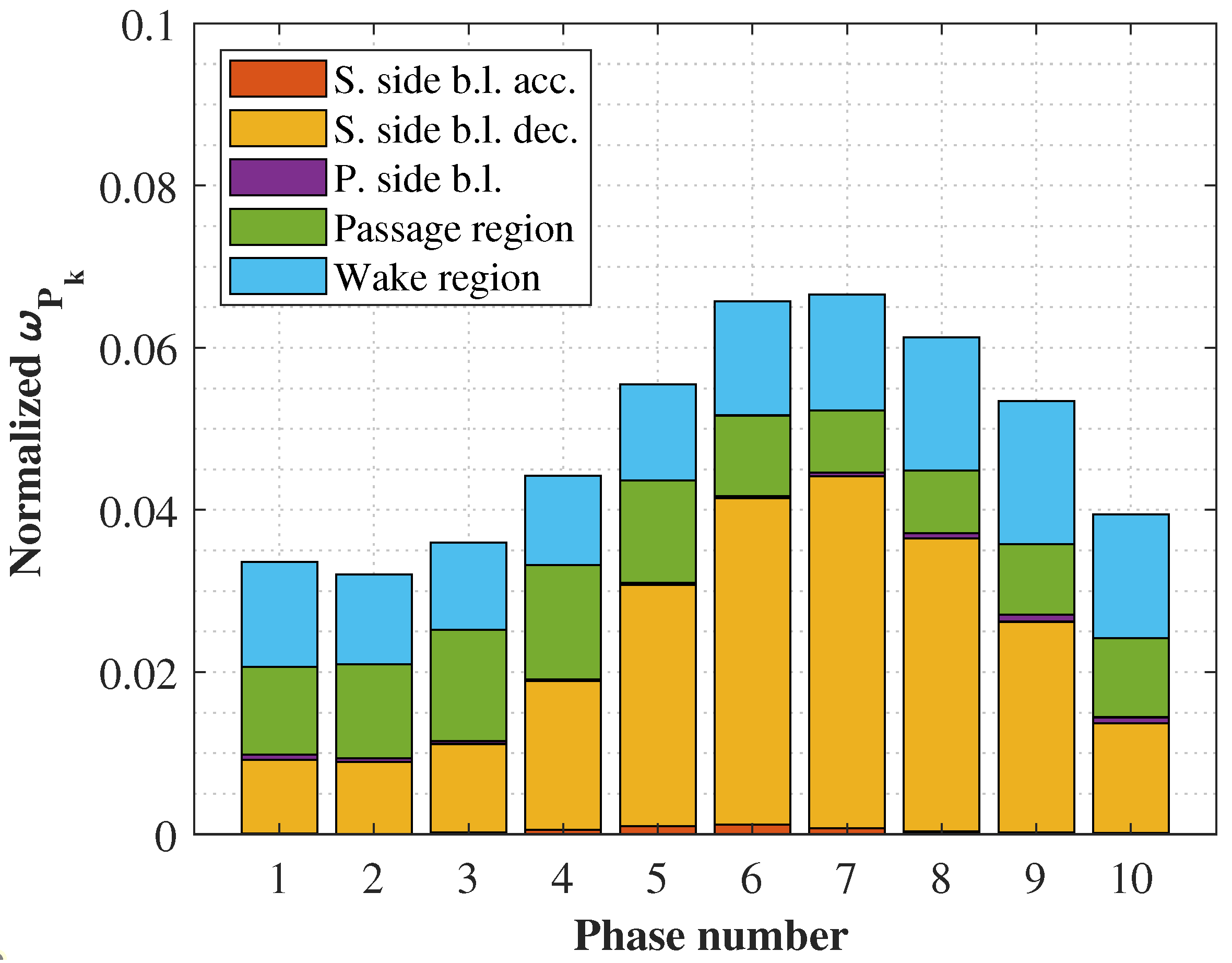

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show the bar plots of

normalized by the overall loss coefficient obtained for the AL profile, such that the cumulative sum of the bar plots across all phases represents the percentage loss, excluding the viscous term contribution.

For both blades, the phase characterized by the minimum turbulence-related loss is phase 2, which corresponds to the wake located close to the leading edge of the blade (see fig.

Figure 9). Here, turbulent production is primarily concentrated in the passage region (green area in

Figure 10 for phase 2). As the wake centerline moves towards the trailing edge of the profile, losses increase and become dominated by events in the decelerating region of the blade suction side and within the profile’s wake, with the passage region no longer being the area characterized by the maximum turbulent production. Maximum loss for both profiles is observed at phase 7, even though the spatial flow regions where these occur differ significantly between the two profiles. For the AL profile, the largest contribution to the total loss is attributed to the wake region (cyan sector), while for the HL profile, higher losses are observed in the decelerated boundary layer (yellow sector).

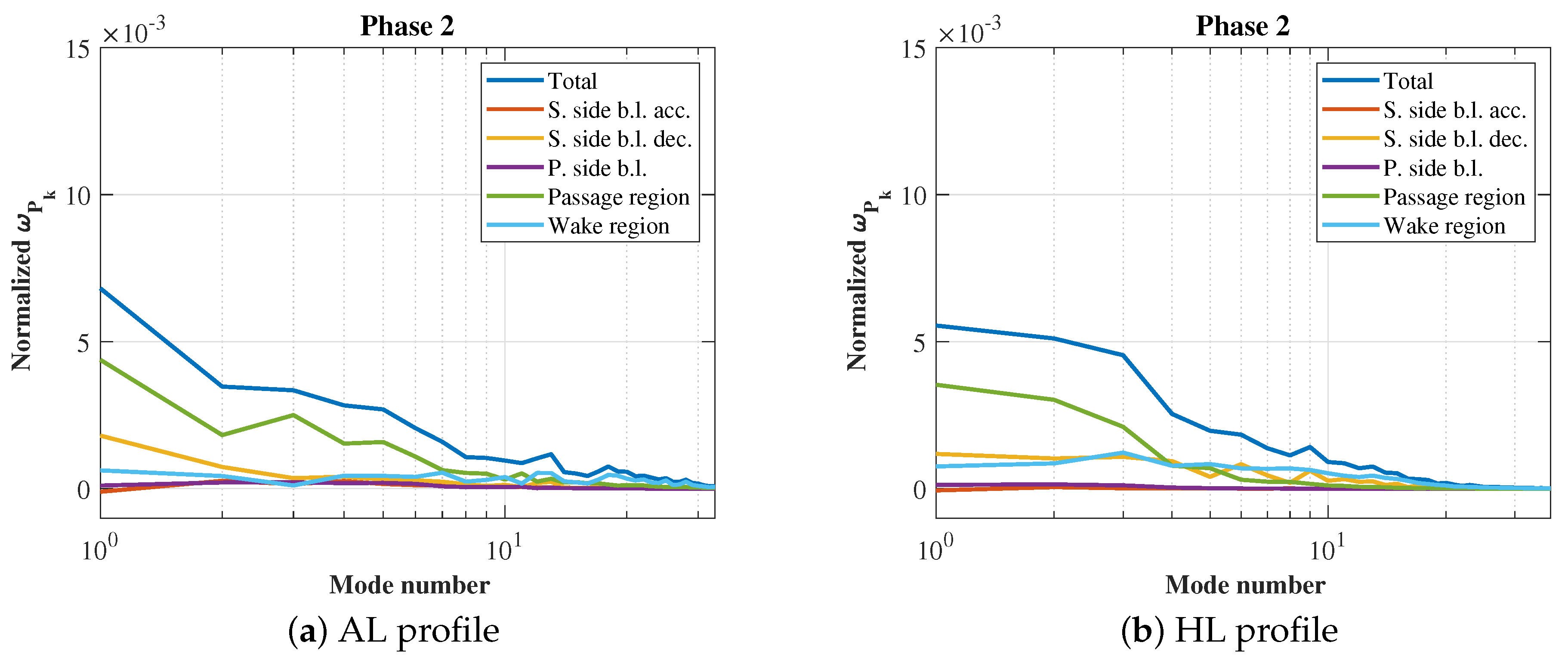

These observations are reflected in the plots of normalized

as a function of the PPOD mode index at a fixed phase. Figures and show this trend for the phase characterized by the lowest turbulent production (phase 2) for the AL and HL profiles, respectively. As can be observed, in both cases, the most significant contribution to turbulent kinetic energy production is primarily associated with the low-order modes (i.e., for mode indices smaller than 10), which predominantly act in the passage region (green curve), with a minor additional contribution in the decelerating part of the boundary layer (yellow curve). As previously observed in

Figure 9, at this phase the upstream wake is located near the leading edge of the cascade, thus the momentum impingement effects on the rear suction side are limited. The boundary layer is stabilized by the acceleration of the flow imposed by the blade loading, which keeps its laminar characteristics as the wake passes. This results in the boundary layer losses being predominantly of a viscous nature, as shown in

Section 5.1, while turbulence-related events are observed essentially outside of the boundary layer, within the bulk flow region.

Figure 12.

Plots of normalized as a function of phase 2 mode index for (a) the Aft-Loaded and (b) the High-Loaded cascades. Blue curve represent the total mode contribution from the five sub-regions

Figure 12.

Plots of normalized as a function of phase 2 mode index for (a) the Aft-Loaded and (b) the High-Loaded cascades. Blue curve represent the total mode contribution from the five sub-regions

| |

|

| (a) AL profile |

(b) HL profile |

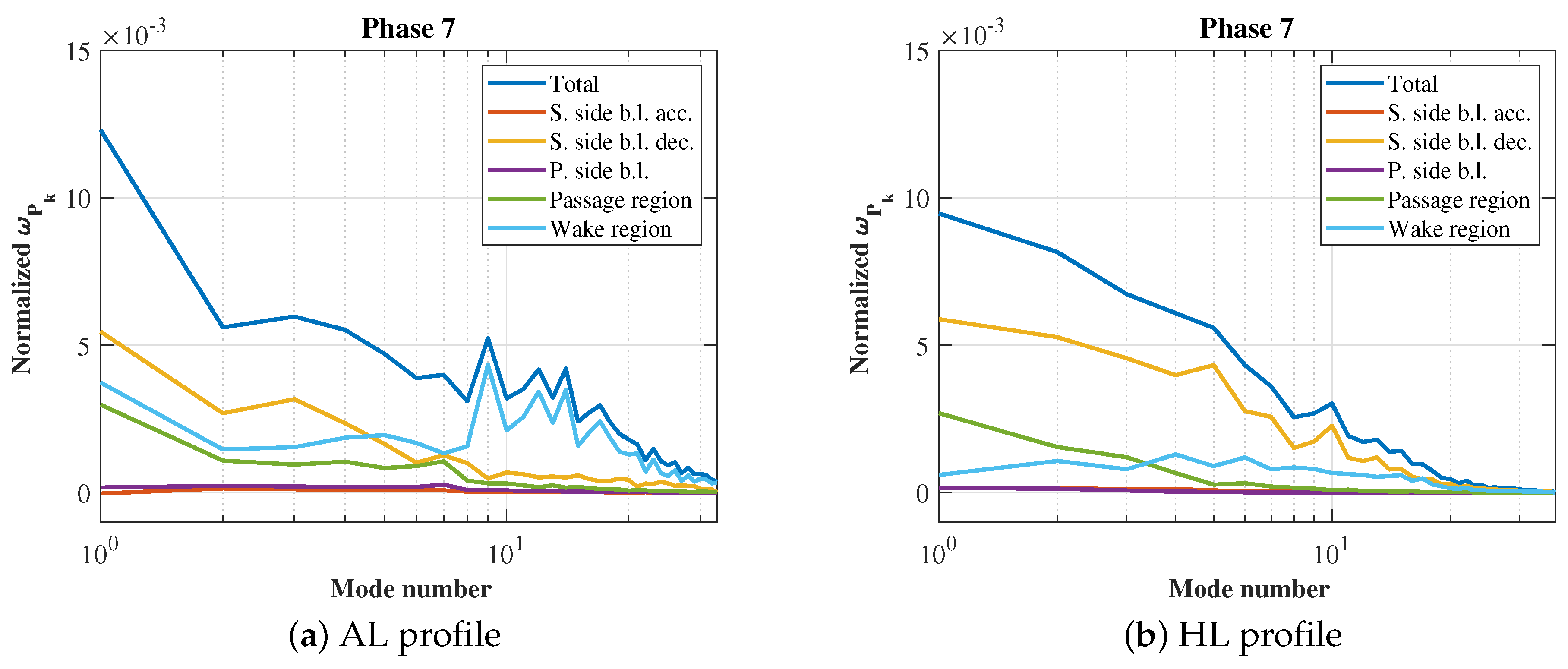

As noted earlier in this section, a new scenario emerges when the wake shifts towards the trailing edge, and the differences are clearly observed in the normalized

plots reported in

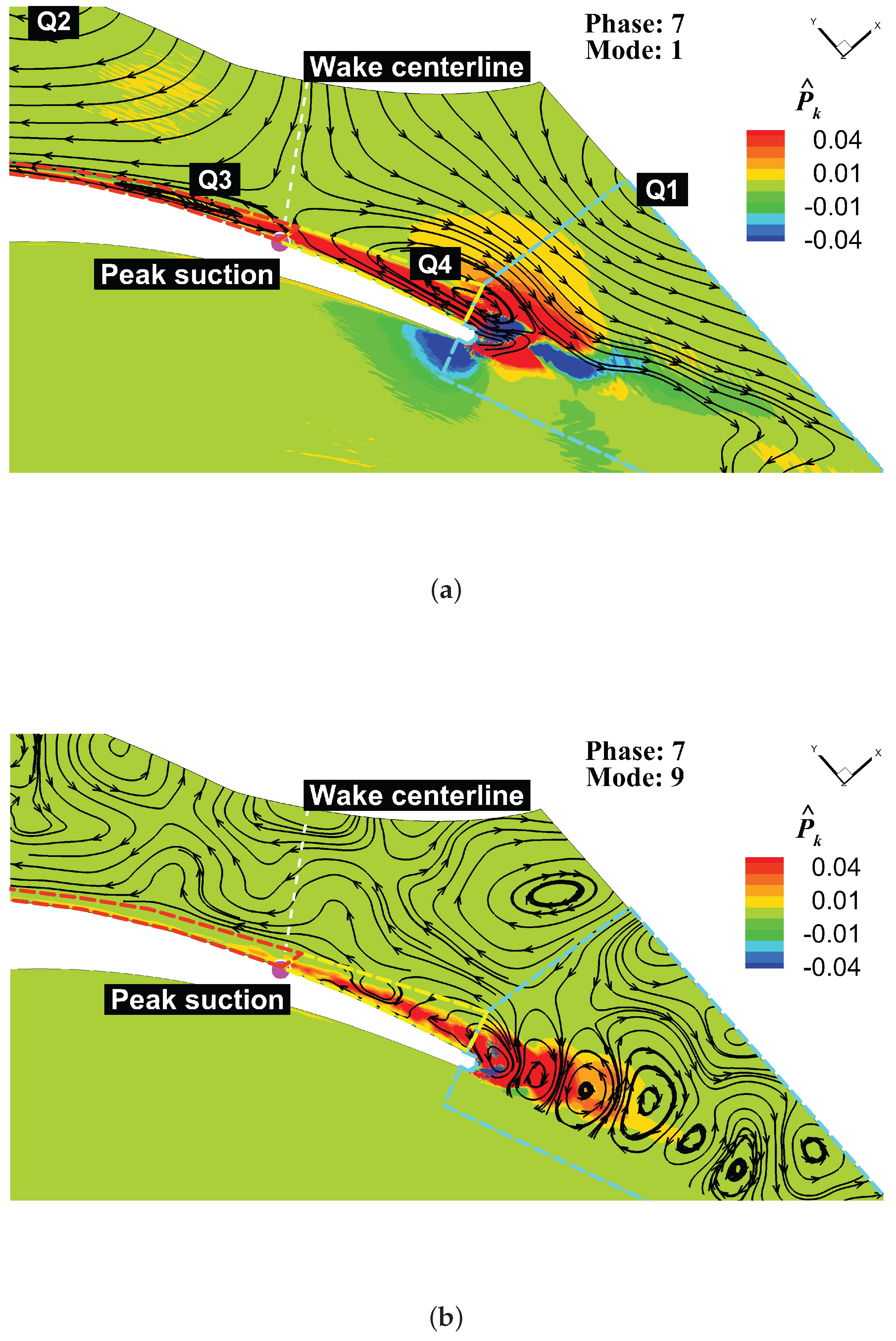

Figure 13. The analysis of PPOD mode 1 for the phase with the highest turbulent production (phase 7) allows us to pinpoint the position of the wake centerline, which, for both profiles, is located at the peak suction position. In this case, maximum turbulence production occurs on the rear suction side for both cascades, where the low-order modes associated with the upstream wake continue to dominate the loss generation mechanisms. During this phase, for the AL profile, significant losses are also generated within the wake region, and interestingly, higher-order modes contribute substantially to the generation process (see the cyan curve for mode indices greater than 9). The specific distribution of the blade loading characterizing the AL profile causes the point of maximum flow velocity around the blade to be located very close to the trailing edge, in contrast to what occurs with the HL profile.

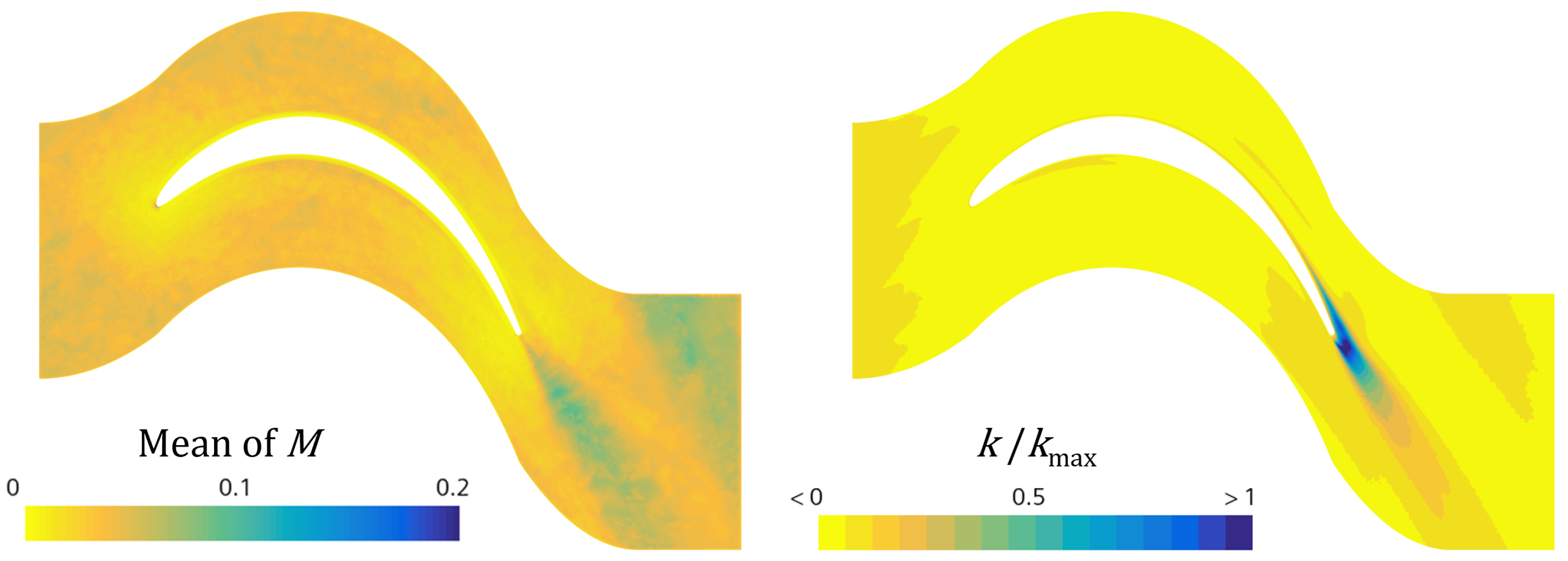

To better understand the different mechanisms involved in loss generation for both cascades, the contour plots in

Figure 14 show the

levels for PPOD mode 1 observed at phase 7, in a meridional section (located at midspan) of the rear part of the computational domain. This quantity represents a normalization of the production of TKE defined as:

The contour is overlaid with streamlines computed from the low-order reconstruction associated with each mode and centered around the peak suction position.

In addition to the previously identified Q1 and Q2 vortices, the figures highlight two other counter-rotating vortical structures, generated upstream and downstream of the wake centerline within the boundary layer. These are labeled as "Q3" and "Q4" vortices, and their formation is linked to the negative jet of the incoming wake. The modal representation of the flow obtained from the PPOD procedure enables the direct identification of the phase of maximum loss as the one characterized by the greatest amplification of these large-scale vortical structures.

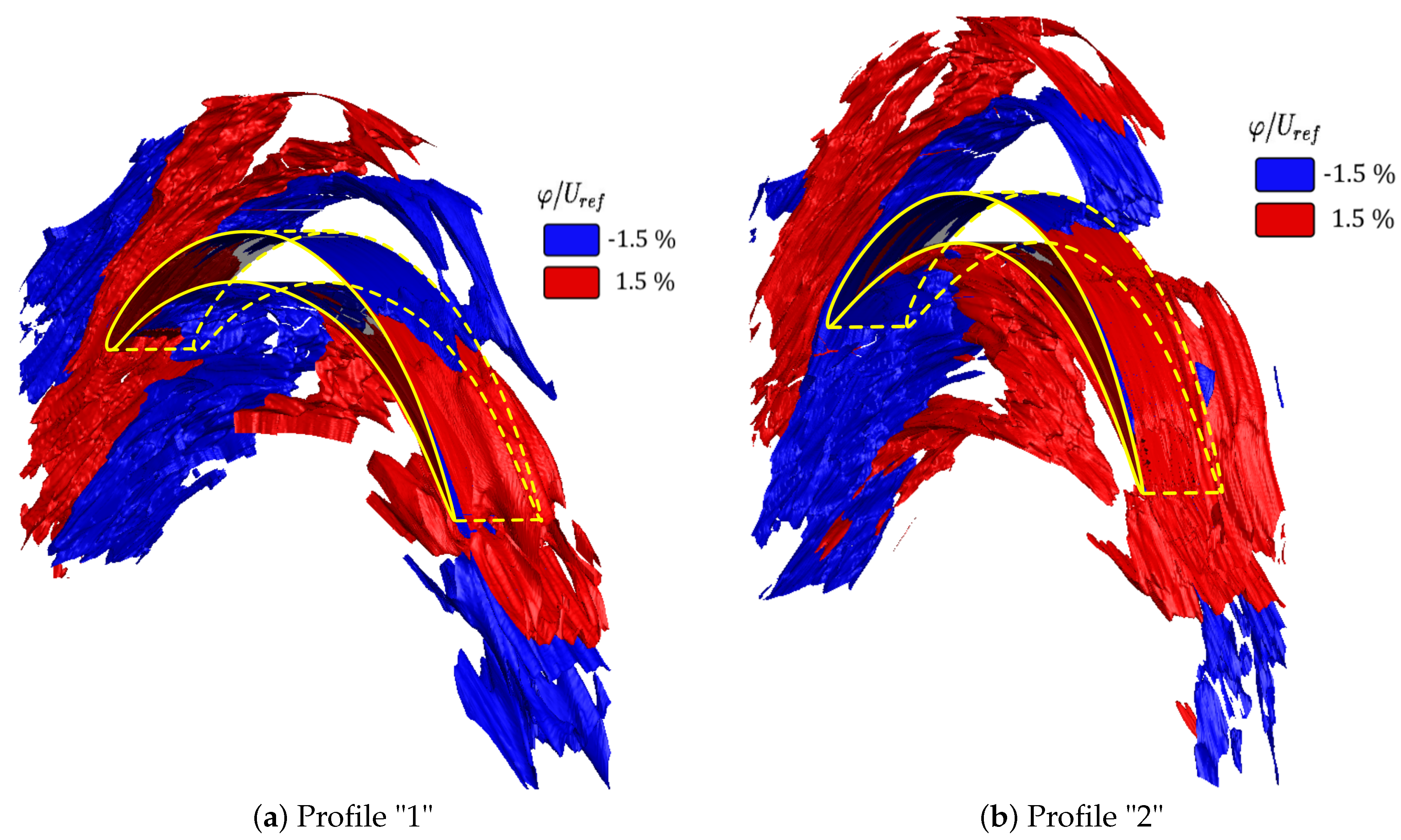

For what concerns the AL profile (Figure ), the proximity of the strongly amplified Q4 vortex to the trailing edge of the blade allows for the development of this structure further downstream in the wake region, as it is not spatially constrained by the presence of a solid wall. Observing the curve trends in

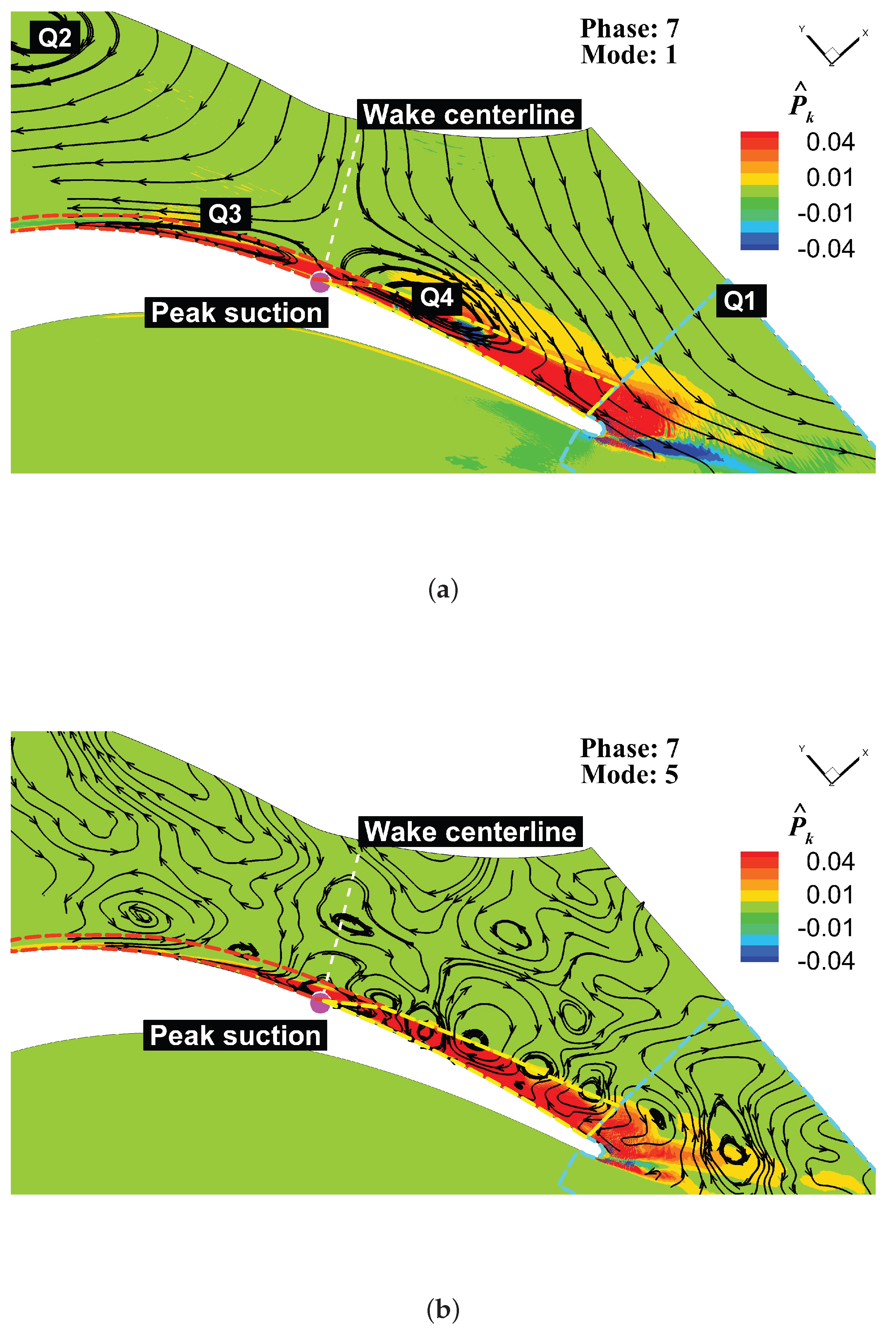

Figure 13, a significant loss peak is noted in correspondence with mode 9 in the wake region (cyan curve). This mode captures the dynamics highlighted in

Figure 15 by means of streamlines superimposed on the mode contour. It shows a clearly defined Von-Kármán vortex street, likely originating from the interaction between the Q4 vortex and the region of low momentum behind the trailing edge of the profile, which emerges as the main source of loss not directly related to the large-scale structures characterizing the upstream wake.

In the case of the HL profile, however, the upstream shift of the peak suction position causes the maximum spatial extent of the Q4 vortex to be limited, above by the Q1 vortex and below by the blade wall.

Figure 15 shows that, under these conditions, the evolution of this vortex is largely confined within the boundary layer region. The highest loss peaks are indeed associated with the decelerating portion of the boundary layer (yellow curve in

Figure 13). The most significant contribution to losses among the PPOD modes not related to the upstream wake is recorded in mode 5, whose two-dimensional representation is depicted in

Figure 15. Mode 5 at phase 7 for the HL profile capture characteristic structures originating into the rear suction side. They are medium-scale roll-up vortices with axes aligned with the spanwise direction, which can be typically observed in the case of bypass-like transition mechanisms. The large-scale vortex structures observed for the AL profile within the wake region are not tracked by any of the HL profile’s modes at maximum loss phase.

Thus, the detailed analysis enabled by PPOD clearly allows the identification of maximum losses in the suction side BL region or within the wake downstream of the trailing edge when the upstream rotor wake is located at exactly the peak suction position. Depending on the blade loading, the structures captured by the higher-order PPOD modes interact with the boundary layer or the incoming wake, representing distinct contributions to the overall losses.