Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: From Discounted Flows to Timed Returns

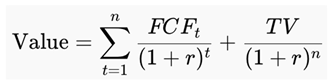

2. Origins and Limitations of the Discounted Cash Flow Model (DCFM)

2.1. Historical Foundations

2.2. Structural Weaknesses

- Speculative Forecasting: Long-range FCF projections are inherently fragile and assumption-laden.

- Terminal Value Distortion: Terminal values often comprise 60–80% of the model’s output, based on arbitrary perpetual growth assumptions.

- Opacity and Subjectivity: Numerous assumptions reduce transparency and make results difficult to audit or reproduce.

- No Rate-of-Return Output: Unlike bonds that yield an annualized return (YTM), DCFM provides a price, not a rate—limiting cross-asset comparison.

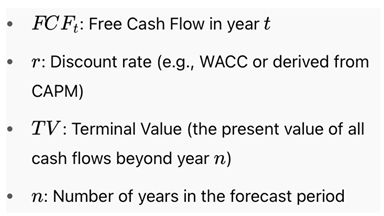

3. Introducing the Potential Payback Period (PPP)

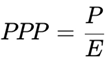

3.1. Core Formula

- P/E: Price-to-Earnings ratio

- g: Expected annual earnings growth rate

- r: Discount rate (e.g., from CAPM)

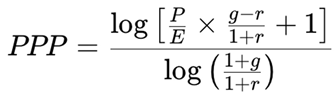

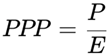

- When g = r, it simplifies to:

- When g = 0 and r = 0, it again reduces to:

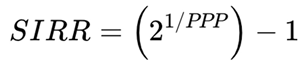

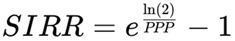

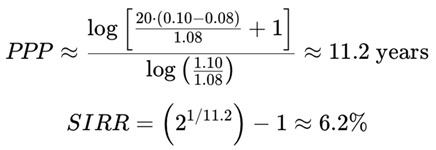

3.2. Doubling Formula for SIRR

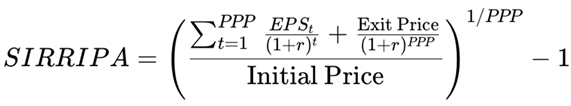

4. Adding Price Appreciation: From SIRR to SIRRIPA

4.1. Why Exit P/E = PPP

5. Comparative Analysis: DCFM vs. PPP in Practice

5.1. Example Scenario

- Price = $100

- EPS = $5 → P/E = 20

- g = 10% expected earnings growth

- r = 8% discount rate

- Ten-year forecast horizon: While future earnings or cash flows could theoretically extend indefinitely, projecting more than 10 years becomes increasingly speculative. A 10-year horizon is widely accepted as the outer boundary for “plausible” forecasts in most industries, balancing model complexity with diminishing confidence in long-term estimates.

- Terminal growth rate of 3%: This figure is typically used to approximate the long-run growth of the overall economy (e.g., GDP growth or inflation-adjusted output). The assumption is that after 10 years, the company matures and grows at a modest, sustainable pace indefinitely.

- Most of the stock’s estimated intrinsic value (often 60–80%) comes from the terminal value—which is itself based on highly uncertain assumptions about steady-state growth and cash flow behavior a decade into the future.

- Small changes to the 3% terminal growth or the 10th-year FCF can drastically alter the valuation, reducing reliability and transparency.

6. When DCF Fails and PPP Persists

- Negative or erratic FCFs: PPP operates on normalized EPS.

- g ≈ r: No instability—the formula remains defined.

- No dividends or unclear terminal value: PPP requires neither.

- Loss-making firms: With expected normalized earnings, PPP can still yield a meaningful time horizon.

7. Conclusion: From Cash Flow Speculation to Time-Based Precision

References

- Williams, J. B. The Theory of Investment Value; Harvard University Press, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, W. F. Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of Market Equilibrium under Conditions of Risk. The Journal of Finance 1964, 19(3), 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, A. Investment Valuation: Tools and Techniques for Determining the Value of Any Asset, 3rd ed.; Wiley Finance, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penman, S. H. Financial Statement Analysis and Security Valuation, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, P. Company Valuation Methods; IESE Business School, 2015; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2749731.

- Luehrman, T. A. Using APV: A Better Tool for Valuing Operations. Harvard Business Review May-June 1997. https://hbr.org/1997/05/using-apv-a-better-tool-for-valuing-operations. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, R. Extending the P/E and PEG Ratios: The Role of the Potential Payback Period (PPP) in Modern Equity Valuation. SSRN 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5240458.

- Sam, R. Revisiting the Gordon-Shapiro Model: How the Potential Payback Period (PPP) Refines and Operationalizes a Foundational Framework in Stock Valuation. SSRN 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5248835.

- Sam, R. Breaking the Valuation Deadlock: Replacing the P/E Ratio with the Potential Payback Period (PPP) for Loss-Making Companies – A Case Study on Intel (2025). SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, R. Generalizing the P/E Ratio through the Potential Payback Period (PPP): A Dynamic Approach to Stock Valuation. SSRN 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5261816.

- Sam, R. Proving that the P/E Ratio is Just a Limiting Case of the Potential Payback Period (PPP) When Earnings Growth and Interest Rate are Ignored. SSRN 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5254723.

- Sam, R. How the Potential Payback Period (PPP) Extends and Surpasses the Gordon Growth Model (GGM) at the Limits of Financial Theory. In SSRN; /: https, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, R. A Quantitative Revelation in Equity Valuation: The P/E Ratio is a Degenerate Case of the Potential Payback Period (PPP). In SSRN; 2025; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5268285.

- Brealey, R.A.; Myers, S.C.; Allen, F. Principles of Corporate Finance, 13th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).