1. Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is a leading cause of disability among adults worldwide[

1]. Patients with ABI present with physical, cognitive and psychosocial challenges that may affect all aspects of life[

2], and as an acute event, ABI may disrupt the life course of patients unexpectedly[

3]. The most robust estimate of disability after ABI was found in a review of 22 studies, where some degree of disability was established for 24%-49% of patients[

4]. ABI leads to extensive individual consequences such as reduced health-related quality of life and reduced satisfaction with life in general for up to 61%[

5]. This pose a potential risk that patients may strive to sustain a meaningful life. In a study on self-management, Kılınç et al. found that patients conceptualised energy as a form of treasured currency that could be stored to enable engagement in everyday activities or other specific events. This balance was fundamental to living their lives and engaging in activities that enabled them to achieve or maintain a sense of meaning and purpose[

6].

1.1. Disability in the Discharge Transition Phase

Disability is a collective term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions denoting the negative aspects of the interaction between an individuals' health condition and contextual factors (environmental and personal factors)[

7]. In a Danish health-care perspective, the rehabilitation process is specifically aimed towards a meaningful life for the patient with the best possible activity and participation, coping and quality of life[

8]. For patients with moderate and severe ABI, the rehabilitation process begins at specialised in-hospital clinics [

9] from which they are eventually discharged to familiar social and physical surroundings while adjusting to disability[

10]. During this transition, they establish a new balance in their everyday life activities, and discover to which degree they may recover, work and live independently or with assistance. However, the extent of disability and dependency at discharge might not be evident for either the patient [

11] or supportive relatives[

12], and some challenges may not present themselves until months after discharge[

13]. Thus, the discharge transition phase implies potentially stressful adjustment to disability during the change of environment[

14]. Specifically during the discharge transition phase, patients have reported difficulties reengaging in meaningful activities[

15].

1.2. Factors Affecting Disability in the Transition Phase

In previous research, factors have been identified as significantly associated with disability or related rehabilitation outcomes after ABI; Age, Sex, Diagnosis and Duration between injury and referral to rehabilitation are acknowledged as potential confounders of rehabilitation outcomes after ABI[

16,

17,

18,

19]. Fatigue has been associated with decrease in short-term functional outcome[

20], return to work [

21] and health related quality of life[

22]. High self-efficacy has been identified in a systematic review to be associated with higher level of functioning in daily activities in patients with stroke[

23]. This is understood through facilitation of personal effort and motivation and upholding of persistence as coping strategies in face of barriers and setbacks[

24]. Fatigue and functional independence were found to be significant predictors of disability in 15-30 year-olds with ABI[

25]. Physical activity is associated with positive rehabilitation outcomes[

26]. Also, cognitive dysfunction was found to be associated with low health-related quality of life after TBI[

27].

The aim of the present study was to investigate disability level and other indicators of a meaningful life for patients with ABI in the discharge transition from in-hospital rehabilitation. Disability and factors associated with disability three months after discharge were investigated. As secondary outcomes we reported; Health-related quality of life; Recovery; Assistance requirements; Hospital readmissions; Work status; and Occupational balance.

2. Materials and Methods

We setup a prospective follow-up study during the discharge transition phase. Baseline assessment was an interviewer-based survey one week prior to discharge, and follow-up was a self-reported survey three months after discharge.

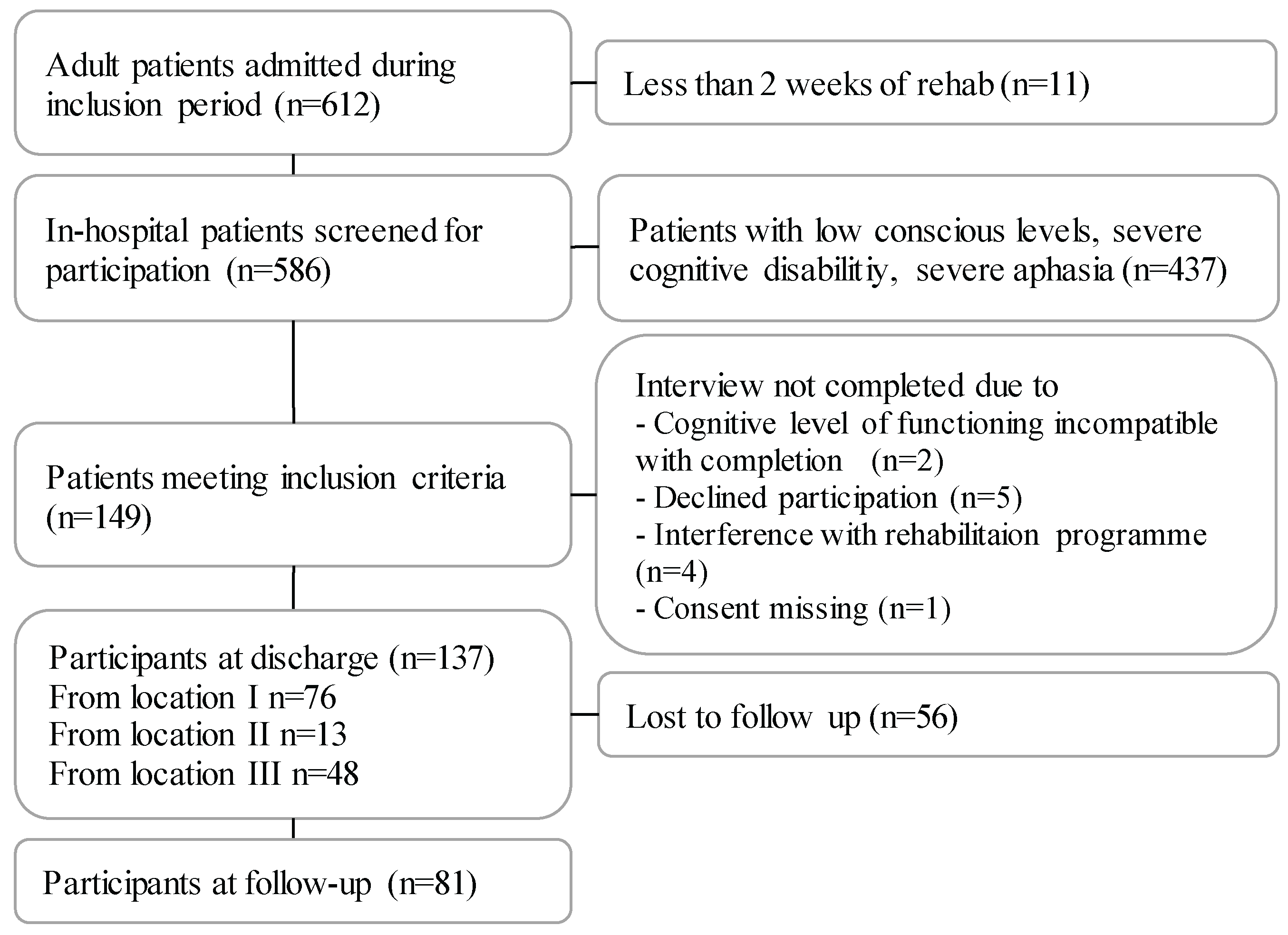

Patients were consecutively recruited from Hammel Neurorehabilitation Centre and University Research Clinic, Denmark (HNCURC) from September 2020 to September 2021, with a two months' non-inclusion from January 2021 to comply with national Covid-19 guidelines. The HNCURC is located in three cities; location I-III (

Figure 1)

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

All patients admitted for more than two weeks were systematically screened according to the following inclusion criteria one week prior to discharge: Age ≥18 years; able to speak and understand Danish language; able to give informed consent; and able to participate in a one-hour interview understanding and responding to survey questions. This meant for the exclusion of patients with low consciousness levels, severe aphasia or other severe cognitive dysfunction. For ethical reasons, patients were also excluded if they presented with symptoms like emotional lability, agitation, or confusion, as these conditions may be triggered by the interview situation. Comorbidities like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, or other diseases were not exclusion criteria; nor were minor cognitive deficits like attention deficits or mild aphasia. The inclusion of patients with mild cognitive deficits was decided, because such symptoms are common after ABI, and would likely influence all outcomes. Participation was planned with minimal interference to daily rehabilitation. A representative from local staff at each of eight clinics (either a nurse, nurse’s assistant, therapist, or secretary) assessed patient eligibility from inclusion criteria. The first author (HH) then introduced the patients to the study and invited them to volunteer their participation. If agreed, the baseline survey interview was conducted. To participate in the follow-up survey after discharge, patients received the link to a questionnaire by email, followed by two reminders one week apart. In consideration of the patients' potential fragility after ABI, participation was not further encouraged. Patients were provided with contact information for HH for technical support if needed.

2.2. Baseline Characteristics

Information on diagnosis, severity, comorbidity and functional independence was retrieved from medical records at discharge (see Appendix 1) by the first two authors. Global disability level was assessed by HH at baseline with the Modified Rankin Scale (mRs) in 7 levels from no symptoms (0) to death (6)[

28]. Anxiety and depression levels were reported by patients with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in the baseline survey with seven items scored from one to three on two subscales for anxiety and depression, with three denoting highest level. A subscale score of >8 points out of a possible 21 denotes a moderate to high level of anxiety or depression[

29].

2.3. Outcome Measures

The main outcome was disability. Secondary outcomes were health-related quality of life, recovery, assistance requirements, hospital readmissions, work status, and occupational balance. A list of the patient reported outcomes used in the study is provided in appendix 2.

2.3.1. Disability

Patients rated their disability levels using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0, WHODAS 2.0[

30]. WHODAS 2.0 covers the components of both activity (in the dimensions cognition, mobility, self-care, and life activities) and participation (in the dimensions getting along and social participation) as a worldwide disability assessment tool[

30]. WHODAS 2.0 was chosen due to its excellent test-retest properties across functional levels, diagnoses and settings[

30]. The difficulty of each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; 4, extreme or cannot do). For the baseline assessment, the 36-item interviewer-administered form was used with an assessment time of 20 minutes. For the follow-up assessment, the 12 item self-administered form was used to avoid patient retention from questionnaire burden. The 12-item version explains 81% of the variance in the 36-item version[

31]. Disability scores from both assessments were converted to index values from 0 to 100, where 0 = no disability; 100 = full disability[

31], allowing for comparison of disability levels at baseline and follow-up. WHODAS 2.0 categories of disability have been suggested for easy interpretation (0–4, no difficulty; 5–24, mild; 25–49, moderate; 50–95, severe; 96–100, extreme)[

31].

2.3.2. Covariates

The following covariates for disability were chosen: age, sex, ABI type, duration from ABI debut to rehabilitation admission, self-efficacy, premorbid physical activity level, presence of pathological fatigue, and the cognitive dimension of functional independence. Self-efficacy was assessed with the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES); a 10-item psychometric scale designed to assess optimistic self-beliefs to cope with a variety of difficult demands in life[

32]. Total scores ranged between 10 and 40, with a higher score indicating more self-efficacy. Physical activity level classified with the Saltin-Grimsby Physical Activity Level Scale[

33]. Fatigue was self-reported with the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) in five dimensions with sub score sums ranging from 4 (fatigue absent) to 20 (severe fatigue) [

34]and with a cut off of 12 on the sub score general fatigue indicating pathological fatigue[

35]. The functional independence measure (FIM) sub score for cognitive level was rated on a 7-point scale from 1 = total assistance to 7 = complete independence and a sum score ranging from 5-35[

36].

2.3.3. Secondary Outcome Measures

Health-related quality of life was assessed with the EuroQol index value calculated from the interviewer-administrated EQ5D-5L using a validated Danish Value set with outcomes ranging from -0.757 (worse than death), 0 (death) to 1 (full health)[

37]. The EQ5D-5L describes health-related quality of life in the dimension's anxiety/depression, pain/discomfort, mobility, self-care, and usual activities into 5 levels (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and unable/extreme problems).

Work status was reported in the categories self-employed, employed, unemployed, retired, studying and on sick-leave and dichotomized by combining the responses "not employed", "retired", "studying" and "on sick leave" into a "not in remunerative work" category.

Occupational balance was assessed with the Danish Occupational Balance Questionnaire, OBQ-DK[

38,

39,

40]. We used the 11-item version with four meaningfully ordered responses ranging from disagree = 0 and partially disagree = 1 to partially agree = 2 and agree = 3. Sum scores would range from 0-33 with higher ratings implying better occupational balance. The OBQ-DK summary score was presented and dichotomised into low and high level of occupational balance with a split at <22, indicating that the patient could have possibly "agreed" (score 0) on at least one item.

Recovery and personal assistance requirements was covered by the "Two simple questions"[

41,

42]. The extent of community-based rehabilitation and hospital re-admissions was assessed with customized questions.

2.4. Data Analysis and Statistics

Patient characteristics were presented with frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Scores of functioning were presented within the relevant summary range of individual scores. Demographics and health parameters of included patients were compared to excluded patients at the HNCURC.

Disability at baseline was reported with the WHODAS 2.0 median scores of each domain, and the total median score was reported as a weighted complex scoring according to the manual for the 36-item version[

43]. Disability at follow-up was reported as an index score from 0-100 obtained by dividing the summary score with 48 according to the manual for the 12-item version[

43]. For less than two missing WHODAS 2.0 items, imputation from the median score was performed[

43]. A multiple linear regression analyses were conducted with disability (WHODAS 2.0) at follow-up as outcome. Assumptions were evaluated on plots of observed versus predicted values, scatter plots, residual plots, histogram, and QQ plot. Statistical analyses were performed in Stata 16,0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Secondary outcomes were presented as a descriptive summary and plots of median scores. Statistical significance of change in status from working to not working from baseline to follow-up was tested with McNemar's test. Wilcoxon ranksum test was used to compare disability levels for patients in remunerative work and others, and for patients reporting potential occupational balance and imbalance.

3. Results

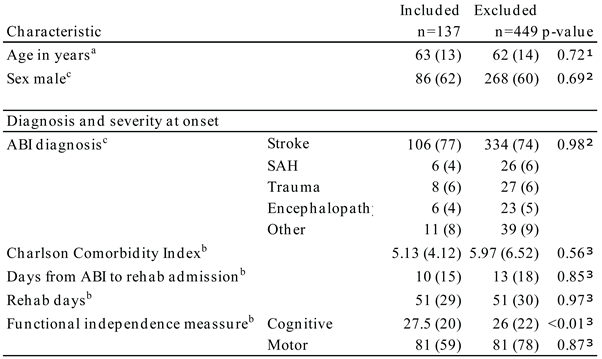

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Of 586 screened patients, 137 were included, 62% males, and the mean age was 63 years. The cohort is presented in

Table 1. They were admitted for rehabilitation at a median of 10 days after ABI. The largest group represented was patients with stroke (77%). Compared to patients who were not included, the significant difference was cognitive level measured on the FIM subscale (p<0.01).

3.2. Disability in the Discharge Transition Phase

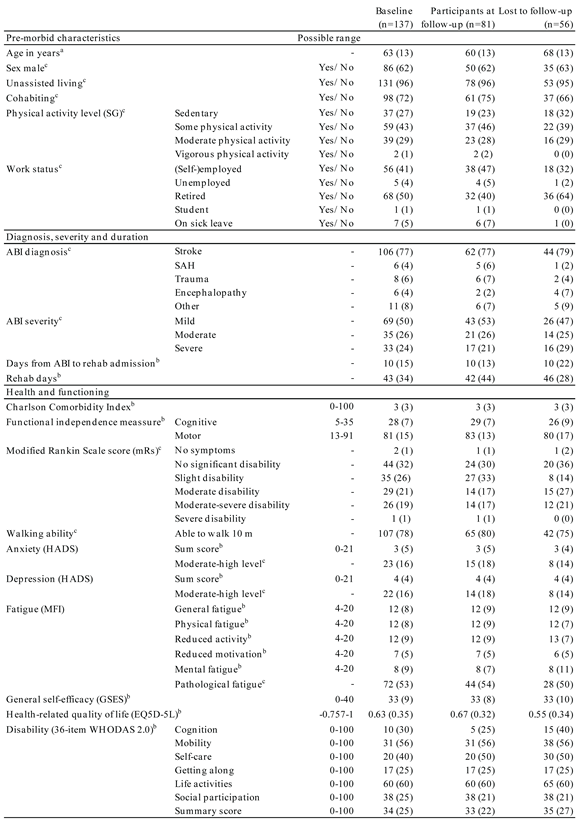

The survey answers at baseline are presented in

Table 2. The median disability level at discharge was 34%, and the domain "life activities" was the most affected with a median of 60%.

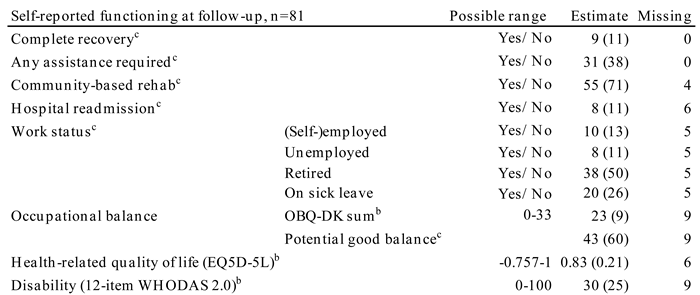

Raw estimates of the patients' survey answers at follow-up are presented in

Table 4. The median disability level (WHODAS 2.0) was 30%, and no systematic change was found between disability level at discharge and follow-up (p=0.4860). The proportion of patients with a disability score equivalent to moderate or severe disability was 59% at follow-up (data not shown).

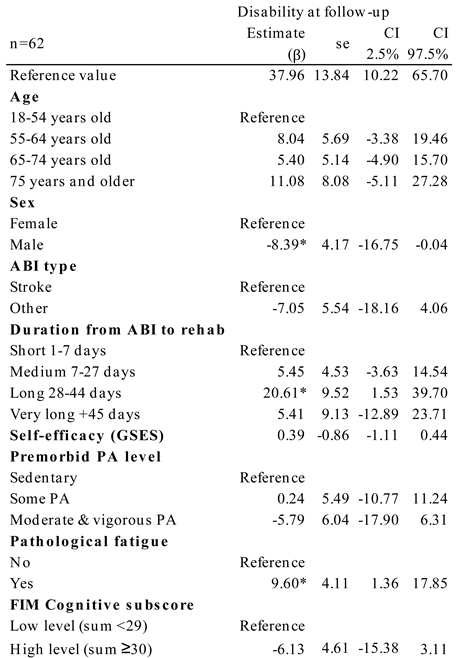

Table 3.

Covariates for disability in the discharge transition phase.

Table 3.

Covariates for disability in the discharge transition phase.

Covariates significant for disability at follow-up were sex, duration from ABI to rehabilitation admission, and presence of pathological fatigue (

Table 3). When adjusted for the other covariates, the regression showed a 20.61 higher disability level for patients who had 28-44 days from ABI to rehabilitation relative to patients with 1-7 days prior to rehabilitation (p=0.035). It also showed a 9.60 higher disability level for patients with pathological fatigue (p=0.023) vs. patients without fatigue. For men, a significantly lower disability level of -8.39 was found relative to the disability level for women (p=0.049).

3.3. Other Aspects of Functioning in the Discharge Transition Phase

Eleven percent experienced a complete recovery. More than half (62%) lived unassisted; and 71% participated in a community-based rehabilitation programme with physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, or group-based training. A health-related quality of life level of 0.83 (0.21) was found at follow-up after a systematic improvement from discharge of 0.17 (95% CI 0.12-0.23), p<0.001.

Table 4.

Descriptive data on self-reported functioning at follow-up.

Table 4.

Descriptive data on self-reported functioning at follow-up.

3.3.1. Work Status

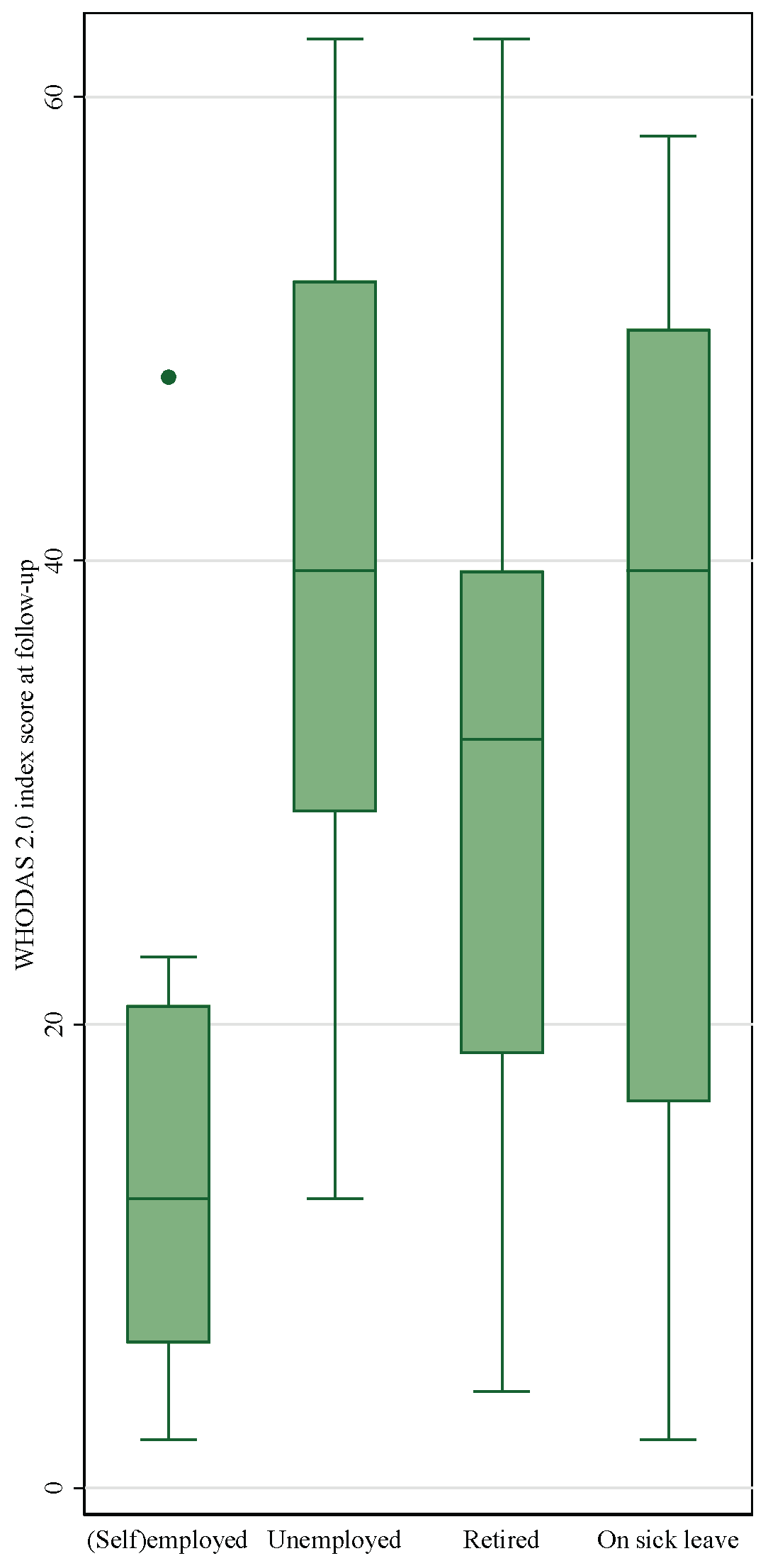

Figure 2. Work status and disability level at follow-up

The proportion of patients in remunerative work dropped significantly (p<0.001) from 41% before the ABI to 13% at follow-up (

Table 3). Of the 45 respondents below retirement age (65 years) in the cohort, 18% were working and reported mild disability levels at follow-up (

Figure 2), whereas 10% reported to be retired, 16% were unemployed and 44% on sick-leave. The disability level of patients who were not in remunerative work was significantly higher than the disability level for working patients (p=0.0030).

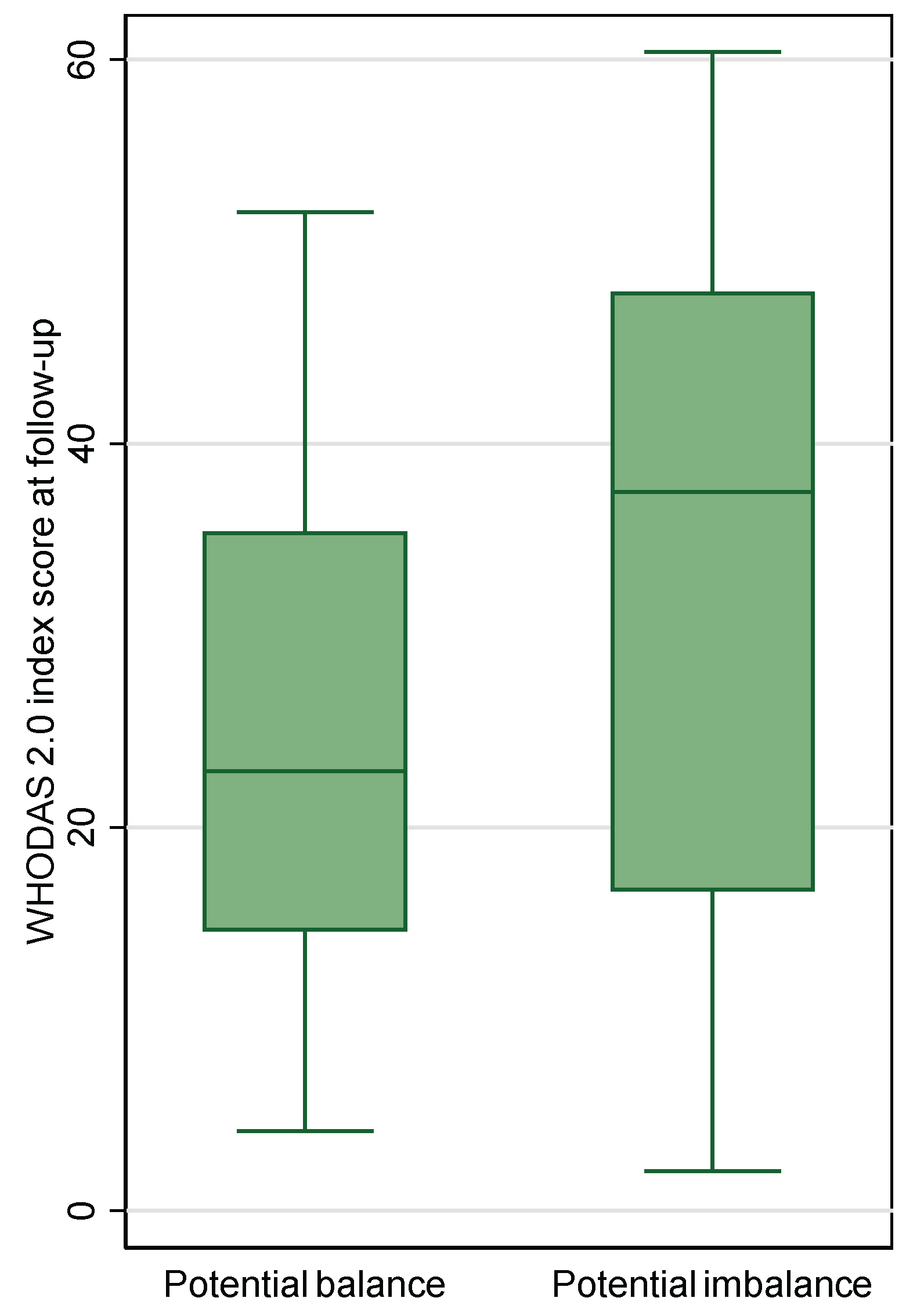

3.3.2. Occupational Balance

Occupational balance was reported by 72 (52%) of patients at follow-up with a median sum score (IQR) of 23 (9). Twenty-nine patients (40%) reported potential imbalance on at least one item. For patients with responses classified as potential imbalance, the disability level ranged wider, but it did not differ statistically from patients with responses classified as potential balance (p=0.013) (see box plot in

Figure 3).

Figure 3. Occupational balance and disability level at follow-up

3.4. Patients at Follow-up

At follow-up the response rate ranged from 41-47% (

Table 4). An overview of the patients' demographics, diagnoses and functioning at baseline was provided for patients who remained in the cohort at follow-up (right column) and who dropped out (middle column) for easy comparison (

Table 2). Follow-up respondents were younger than non-respondents with a mean age 60 years vs. 68 years, and they reported more frequently cohabiting with another adult at discharge than non-respondents. Respondents had higher functional levels measured with FIM scores and WHODAS 2.0 disability index than those lost to follow-up. The summary score was higher for the non-respondents with a median of 35 vs. 33 for participants. All domain scores for disability were higher for non-respondents except for the domains "getting along" and "social participation". The largest difference in disability was in the cognition domain with a median of 5 for respondents and 15 for non-respondents. FIM scores on cognition were also lower for respondents than for non-respondents. Corresponding estimates were found for respondents and non-respondents regarding baseline level for sex, depression, fatigue, and general self-efficacy scores. Also, the distribution of ABI diagnoses was similar between the two groups, with a prevalence of apoplexy of 77-79%.

4. Discussion

We assessed disability and other aspects of functioning after ABI for 137 patients in the discharge transition phase. At follow-up, 59% participated. Complete recovery was reported by 11% after three months. A moderate disability level persisted with no systematic change between discharge and follow-up, and a median disability level of 38% was found when adjusted for confounding variables. Health-related quality of life was 0.63 (0.35) at discharge and 0.83 (0.21) at follow-up with a mean improvement of 0.17 (95% CI 0.12-0.23), p<0.001. Ten patients (13%) returned to work during the transition phase, and they had lower disability levels than non-working patients (p=0.0030). Twenty-nine patients (40%) reported potential imbalance.

4.1. Comparison with Other Studies

The disability level in our cohort was in line with findings of disability levels equivalent to 28-44% found in patients with stroke at the time of discharge[

44,

45]. Studies with follow-up after 9 month or more have consistently found a long-term decrease in disability[

4], indicating that functioning improve over time after sub-acute rehabilitation. The stationary disability level in our findings could be an expression of the short follow-up period. Also, disability levels are defined by the patients' functioning within their surroundings, and as the patients might take on more complex and challenging tasks at home than in hospital settings, the transition phase could lead to unchanged disability levels for patients even with increased functional levels. With 71% still participating in community-dwelling rehabilitation, a potential for reduction of disability could be aspired.

Confirmed confounders of disability in our study were sex, fatigue, and duration from ABI to rehabilitation admission. Men reported lower disability levels than women. This match how women have been found consistently more disabled than men, along with higher prevalence of depression and dependency in everyday life across several populations[

46]. The largest confounding effect was found in duration from ABI to rehabilitation. The length of stay in acute care may be a proxy for severity or complexity of ABI, which would match the higher level of disability.

We were surprised to find no confounding effect of self-efficacy. The level of self-efficacy reported in our study (median = 33; IQR=9) was higher than the self-efficacy level reported in a group of community dwelling people with stroke after a neuropsychological rehabilitation intervention (mean = 30, sd = 7)[

47]. This indicated a high level of experienced personal competence to handle novel tasks and to cope with adversity within the study sample. The level of perceived self-efficacy has been identified in a qualitative study to be the foundation for a successful transition experience[

48], and high self-efficacy was found in a systematic review to be associated with higher level of functioning in daily activities in patients with stroke[

23]. However, this was not confirmed in our study. A potential explanation could be that the patients during in-hospital rehabilitation could be in a hopeful state of mind with continuous functional progress.

4.1.1. Health-Related Quality of Life

The health-related quality of life at follow-up was 0.83, which is equivalent to the estimate for the general Danish population of 0.82[

49]. The observed statistically significant change in health-related quality of life of 0.12 (p<0.001) was at a clinically important level[

50,

51]. This is an interesting finding considering how the disability level was not reduced during the same period. In contrast, disability level was identified as the main contributor to reduced quality of life among patients with stroke[

52]. However, the range of health related quality of life in stroke populations is very wide: from -0.02 to 0.92, and there is no linear relationship with illness severity[

53]. It has been suggested by Barclay-Goddard et al. that health-related quality of life might increase over time, because people re-normalize when living with long-term disability[

54,

55]. In a rehabilitation perspective, the high quality of life found in the cohort is very positive; It has been suggested that increased quality of life rather than reduced impairment is the most relevant endpoint of rehabilitation because it adds to the individual experience of meaning in everyday life[

56,

57].

4.1.2. Work

After the first three months of discharge transition, only 11% reported to be in remunerative employment. The most robust available estimation of return to work after ABI was calculated in a 2009 systematic review of 49 studies which found that 40% return to work, and they described lower proportions of return to work with shorter time to follow-up[

58], indicating that returning to work is difficult for people with ABI in general. In a mixed methods study identifying themes of stigma, adjusting, support and readiness as factors influencing return to work after ABI, disability awareness and a fatigue management plan for work places was suggested[

59]. With fatigue confirmed as a significant factor for disability level and lower disability levels represented in patients in remunerative work at follow-up, our findings support this perspective.

4.1.3. Occupational Balance

Twenty-nine patients (40%) reported potential imbalance with a summary median score (IQR) of 23 (9). Occupational balance was previously reported in a stroke population with patients 1-4 years after stroke[

60], where more than half reported poor balance. However, comparisons across studies are difficult, because no cut-off value has been established for good or bad occupational balance, and a 13-item version of the questionnaire was used in previous studies. Calculating an index score (OBQ sum score/max score*100), the summary score of 23 in present study was equal to index 70, which was a very high level of occupational balance compared to all other studies with findings equal to index values from 29-51[

60,

61,

62]. Our findings are surprising, because the moderate disability level could indicate challenges with prioritising meaningful activities. However, it matches the high level of quality of life in the cohort and could be related to strong coping skills regarding disability.

4.2. Clinical Implications - a Meaningful Life in the Discharge Transition Phase

In a rehabilitation aimed towards a meaningful life for the patient with the best possible activity and participation, coping and quality of life, it could have negative implications that the patients' disability level remained moderate throughout the discharge transition phase, and that the domain "life activities" was the most affected with a median of 60% disability. On the other hand, the high level of health-related quality of life could match an acceptance of activity limitations and participation restrictions. The insight that health-related quality of life may increase to a high level in spite of persisting disability is highly important for clinicians to preserve hope for the patients to have a meaningful life in spite of poor functional progress after ABI.

4.3. Limitations

The risk of selection bias should be addressed. Although the included cohort was highly comparable to the excluded patients at HNCURC, there was statistically significant difference in their cognitive function. This difference was expected due to inclusion criteria demanding ability to understand and respond to questions in accordance with subjective experience during a one-hour interview. For all outcome measures, cognitive function could have a substantial influence. Affected self-assessment of competence can lead to under-reporting of symptoms evident to observers, especially in early rehabilitation stages[

63]. The drop-out rate of 41% matched the rates of similar follow-up studies[

64,

65]. The respondents at follow-up reported lower disability levels and higher health-related quality of life at discharge than the patients who dropped out. This may have led to under-estimation of disability level and over-estimation of health-related quality of life.

All outcomes were self-reported. For people with ABI, anosognosia or affected self-assessment of competence may lead to under-reporting of symptoms, especially in early stages[

63]. In a study measuring disability levels with WHODAS 2.0 from both patients with stroke and proxies, a higher level was reported from proxies[

44]. However, the measures correlated well with each other, and the 12-item version of WHODAS 2.0 was recommended to assess disability at discharge, except for patients with very severe stroke, which were not included in present study.

Finally, only patients with moderate or severe ABI that were offered rehabilitation at HNCURC were included, which restricts the generalizability of findings to patients with ABI of the same severity and from comparable health care systems.

5. Conclusions

The meaningful life in the transition phase from in-hospital rehabilitation was potentially challenging for patients with ABI from a moderate disability level. However, health-related quality of life increased to a level equal to the general Danish population. With precaution for selection bias, fatigue, gender and duration of time between the ABI and rehabilitation were confirmed as significant for disability after three months.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H. and J.F.N.; methodology, H.H.; formal analysis, A.R.P.; investigation, H.H. and P.P.E.; resources, H.H.; data curation, H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H.; writing—review and editing, H.H., P.P.E., A.R.P. and J.F.N.; visualization, H.H.; supervision, J.F.N.; project administration, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was part of a PhD project registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (Ref. No. 662580, Case No. 1-16-02-320-19) and was exempt from ethical approval requirements by the Central Denmark Region Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (Request No. 141/2019, Ref. No. 1-10-72-148-19). The study was reported in accordance with the STROBE Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients gave informed, written consent for the use of their survey responses, demographic data, and medical record information.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to ethical and legal restrictions related to the protection of patient privacy and confidentiality. .

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants; clinical staff and patients at HNURC who helped facilitate the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest and no external funding. The study was conducted as part of a PhD-project.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABI |

Acquired Brain Injury |

| EQ-5D-5L |

EuroQol Five-Dimensional Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment Tool |

| FIM |

Functional Independence Measure |

| GSES |

General Self-Efficacy Scale |

| HADS |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| MFI |

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory |

| mRs |

Modified Rankin Scale |

| OBQ-DK |

Occupational Balance Questionnaire, Danish 11-item version |

| mRs |

Modified Rankin Scale |

| SG |

Saltin-Grimsby Physical Activity Level Scale |

| WHODAS 2.0 |

World Health Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1 Classification of Health

Table A1.

Supplementary diagnostic details on the 106 patients with stroke.

Table A1.

Supplementary diagnostic details on the 106 patients with stroke.

| Stroke |

n=106 |

|

| NIHSS, mean (sd) |

96 |

7.12 (5.32) |

| Stroke subtype |

106 |

|

| Ischaemic |

|

76 (72) |

| Haemorrhage |

|

29 (27) |

| Other |

|

1 (1) |

| Stroke subtype, n (%) |

106 |

|

| Lacunar |

|

0 (0) |

| Large artery |

|

32 (30) |

| Other |

|

65 (61) |

| N/A |

|

9 (8) |

| Stroke location, n (%) |

106 |

|

| Cortical |

|

20 (19) |

| Subcortical |

|

23 (22) |

| Midbrain |

|

10 (9) |

| Brainstem |

|

11 (10) |

| Other |

|

39 (37) |

| N/A |

|

3 (3) |

| Affected area, n (%) |

106 |

|

| Left |

|

46 (43) |

| Right |

|

47 (44) |

| Both |

|

10 (9) |

| N/A |

|

3 (3) |

| Thrombolysis/reperfusion therapy, yes n (%) |

106 |

26 (24) |

| Confirmed stroke on imaging, yes (%) |

|

106 (100) |

| CT obtained |

|

63 (59) |

| MRI obtained |

|

86 (81) |

Diagnosis of acquired brain injury (ABI) was categorised as stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic), traumatic brain injury (TBI), subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), encephalopathy and other injuries (i.e. injuries secondary to infection or tumour) according to the Danish Health Authorities’ registry based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10) [

1].

Stroke severity was reported according to consensus-based outcome measures in stroke trials [

2].

Classification as mild, moderate, and severe illness were classified after potential thrombectomy and thrombolysis from the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) as NIHSS 0–8, 8–16, and ≥ 16 [

3].

Where NIHSS was unavailable, the Scandinavian Stroke Scale was converted into NIHSS according to Gray et al. [

4].

For patients with TBI, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was applied for classification as mild (GCS 13-15), moderate (GCS 9-12) or severe (GCS ≤8) [

5].

If no other indicator for severity was available, severity was classified from length of stay in acute care split at 7 and 28 days.

Comorbidity was classified with the Charlson Comorbidity Index from 0 (no disease burden) to 100 (maximal disease burden) based on a raw score from 0 to 29 [

6].

FIM sub scores for motor and cognitive levels were rated on a 7-point scale from 1 = total assistance to 7 = complete independence for the two motor and cognitive subscale domains of 13 and 5 items, respectively, ranging from 13-91 for motor scores and from 5-35 for cognitive scores [

7].

Appendix B

Table 1.

An overview of patient reported outcome measures (PROM) assessed in the study.

Table 1.

An overview of patient reported outcome measures (PROM) assessed in the study.

| Construct |

Patient reported outcome measure (PROM) |

Acronym |

Baseline |

Follow-up |

| Disability |

World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule 36-items |

WHODAS 2.0 |

x |

|

| General self-efficacy |

General self-efficacy Scale |

GSES |

x |

|

| Fatigue |

Multi-dimensional Fatigue Inventory |

MFI |

x |

|

| Physical activity level |

Saltin-Grimsby Physical Activity Level Scale |

SG |

x |

|

| Anxiety and Depression |

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

HADS |

x |

|

| Health-related quality of life |

EuroQol index value 5 Likert scale |

EQ5D-5L |

x |

x |

| Work status |

Customized questions |

Work |

x |

x |

| Disability |

World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule 12-items |

WHODAS 2.0 |

|

x |

| Occupational balance |

Occupational Balance Questionnaire - Danish version |

OBQ-DK |

|

x |

| Recovery |

Two Simple Questions |

|

|

x |

| Personal assistance requirements |

Two Simple Questions |

|

|

x |

| Hospital readmittance |

Customized question (Yes/no) |

|

|

x |

| Attending community-based rehabilitation |

Customized question (Yes/no and type) |

|

|

x |

| |

|

|

|

|

References

- Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016 : a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. 2019.

- Turner-Stokes L, Pick A, Nair A, et al. Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for acquired brain injury in adults of working age. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015;2015(12):CD004170-CD004170. [CrossRef]

- Sveen U, Søberg HL, Østensjø S. Biographical disruption, adjustment and reconstruction of everyday occupations and work participation after mild traumatic brain injury. A focus group study. Disability and rehabilitation. 2016;38(23):2296-2304. [CrossRef]

- Carmo JFd, Morelato RL, Pinto HP, et al. Disability after stroke: a systematic review. Fisioterapia em movimento. 2015;28(2):407-418.

- Hartman-Maeir A, Soroker N, Ring H, et al. Activities, participation and satisfaction one-year post stroke. Disability and rehabilitation. 2007;29(7):559-566. [CrossRef]

- Kılınç S, Erdem H, Healey R, et al. Finding meaning and purpose: a framework for the self-management of neurological conditions. Disability and rehabilitation. 2022;44(2):219-230. [CrossRef]

- ICF: International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: WHO; 2001. eng.

- Maribo T. Hvidbog om rehabilitering. 1. udgave ed. Aarhus: Rehabiliteringsforum Danmark; 2022.

- Kjeldsen SS, Søndergaard S, Mikkelsen LR, et al. A retrospective study of 251 patients admitted to a multidisciplinary, neurorehabilitation unit with intensive care unit capabilities. Disability and rehabilitation. 2018:1. [CrossRef]

- Turner BJ, Fleming JM, Ownsworth TL, et al. The transition from hospital to home for individuals with acquired brain injury: A literature review and research recommendations. Disability and rehabilitation. 2008;30(16):1153-1176. [CrossRef]

- Maude R, Christopher F, Craig B, et al. The experience of time in the transition from hospital to home following stroke. Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 2004;41(3):XI.

- Fraser C. The experience of transition for a daughter caregiver of a stroke survivor. The Journal of neuroscience nursing. 1999;31(1):9-16. [CrossRef]

- Turner-Stokes L, Wade D. Rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: concise guidance. Clinical medicine (London, England). 2004;4(1):61-65.

- Piccenna L, Lannin NA, Gruen R, et al. The experience of discharge for patients with an acquired brain injury from the inpatient to the community setting: A qualitative review. Brain injury. 2016;30(3):241-51. [CrossRef]

- Turner B, Fleming J, Cornwell P, et al. A qualitative study of the transition from hospital to home for individuals with acquired brain injury and their family caregivers. Brain Injury. 2007;21(11):1119-1130. [CrossRef]

- Aas RW, Haveraaen LA, Brouwers EPM, et al. Who among patients with acquired brain injury returned to work after occupational rehabilitation? The rapid-return-to-work-cohort-study. Disability and rehabilitation. 2018;40(21):2561-2570. [CrossRef]

- Barker RN, Gill TJ, Brauer SG. Factors contributing to upper limb recovery after stroke: A survey of stroke survivors in Queensland Australia. Disability and rehabilitation. 2007;29(13):981-989. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen J, Kjeldsen SS, Honoré H, et al. Using Routinely Gathered Clinical Data to Develop a Prognostic Online Tool for Decannulation in Subjects With Acquired Brain Injury. Respiratory Care. 2020;65(11):1678-1686. [CrossRef]

- Verdugo MA, Fernández M, Gómez LE, et al. Predictive factors of quality of life in acquired brain injury. International journal of clinical and health psychology. 2019;19(3):189-197. [CrossRef]

- Maaijwee NAMM, Arntz RM, Rutten-Jacobs LCA, et al. Post-stroke fatigue and its association with poor functional outcome after stroke in young adults. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry. 2015;86(10):1120-1126. [CrossRef]

- Palm S, Rönnbäck L, Johansson B. Long-term mental fatigue after traumatic brain injury and impact on employment status. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2017;49(3):228-233. [CrossRef]

- van de Port IGL, Kwakkel G, Schepers VPM, et al. Is Fatigue an Independent Factor Associated with Activities of Daily Living, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronic Stroke? Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2007;23(1):40-45.

- Korpershoek C, van der Bijl J, Hafsteinsdottir TB. Self-efficacy and its influence on recovery of patients with stroke: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2011 Sep;67(9):1876-94. [CrossRef]

- Allahverdipour H, Asgharijafarabadi M, Heshmati R, et al. Functional status, anxiety, cardiac self-efficacy, and health beliefs of patients with coronary heart disease. Health Promot Perspect. 2013;3(2):217-29. [CrossRef]

- Worm MS, Valentin JB, Johnsen SP, et al. Predictors of disability in adolescents and young adults with acquired brain injury after the acute phase. Brain injury. 2021;35(8):893-901. [CrossRef]

- Ruegsegger GN, Booth FW. Health Benefits of Exercise. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2018;8(7):a029694.

- Gorgoraptis N, Zaw-Linn J, Feeney C, et al. Cognitive impairment and health-related quality of life following traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2019;44:321-331. [CrossRef]

- Saver JL, Filip B, Hamilton S, et al. Improving the reliability of stroke disability grading in clinical trials and clinical practice: the Rankin Focused Assessment (RFA). Stroke. 2010;41(5):992-995.

- Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed). 1986;292(6516):344-344.

- ÜStÜN TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88(11):815-823. [CrossRef]

- Ćwirlej-Sozańska A, Wilmowska-Pietruszyńska A, Sozański B, et al. Analysis of Chronic Illnesses and Disability in a Community-Based Sample of Elderly People in South-Eastern Poland. Medical science monitor. 2018;24:1387-1396. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Measures in Health Psychology: A User's Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs. In: J. Weinman SW, & M. Johnston, editor. Causal and Control Beliefs. Vol. 1. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON; 1995. p. 35-37.

- Rödjer L, Jonsdottir IH, Rosengren A, et al. Self-reported leisure time physical activity: a useful assessment tool in everyday health care. BMC public health. 2012;12(1):693-693. [CrossRef]

- Hedlund L, Gyllensten AL, Hansson L. A Psychometric Study of the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory to Assess Fatigue in Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Community mental health journal. 2014;51(3):377-382. [CrossRef]

- Christensen D, Johnsen SP, Watt T, et al. Dimensions of Post-Stroke Fatigue: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study. Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2008;26(2):134-141. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs PW, Pallesen H, Pedersen AR, et al. Using EFA and FIM rating scales could provide a more complete assessment of patients with acquired brain injury. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2014;36(26):2278-2281. [CrossRef]

- Cathrine Elgaard J, Sabrina Storgaard S, Claire G, et al. The Danish EQ-5D-5L Value Set : A Hybrid Model Using cTTO and DCE Data. 2021.

- Wagman P, Håkansson C. Introducing the Occupational Balance Questionnaire (OBQ). Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 2014;21(3):227-231. [CrossRef]

- Håkansson C, Wagman P, Hagell P. Construct validity of a revised version of the Occupational Balance Questionnaire. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 2019:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Morville A HC, Wagman P, , T. H. Validity of the Danish version of Occupational Balance Questionnaire. COTEC - ENOTHE2016.

- Lindley RI, Waddell F, Livingstone M, et al. Can Simple Questions Assess Outcome after Stroke? Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 1994;4(4):314-324.

- McKevitt C, Dundas R, Wolfe C. Two simple questions to assess outcome after stroke: a European study. Stroke. 2001 Mar;32(3):681-6.

- Organization WH, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, et al. Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Albany: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Tarvonen-Schröder S, Hurme S, Laimi K. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) and the WHO Minimal Generic Set of Domains of Functioning and Health versus Conventional Instruments in subacute stroke. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2019;51(9):675-682. [CrossRef]

- Kilkki M, Stolt M, Rannikko S, et al. Patient- and proxy-perceptions on functioning after stroke rehabilitation using the 12-item WHODAS 2.0: a longitudinal cohort study. Disability and rehabilitation. 2023;ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Appelros P, Stegmayr B, Terent A. A review on sex differences in stroke treatment and outcome. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 2010;121(6):359-369. [CrossRef]

- Svendsen HA, Teasdale TW. The influence of neuropsychological rehabilitation on symptomatology and quality of life following brain injury: A controlled long-term follow-up. Brain injury. 2006;20(12):1295-1306. [CrossRef]

- Gage M, Cook JV, Fryday-Field K. Understanding the transition to community living after discharge from an acute care hospital: an exploratory study. Am J Occup Ther. 1997 Feb;51(2):96-103. [CrossRef]

- Wittrup-Jensen KU, Lauridsen J, Gudex C, et al. Generation of a Danish TTO value set for EQ-5D health states. Scandinavian journal of public health. 2009;37(5):459-466. [CrossRef]

- Coretti S, Ruggeri M, McNamee P. The minimum clinically important difference for EQ-5D index: a critical review. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research. 2014;14(2):221-233. [CrossRef]

- Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the Minimally Important Difference for Two Health State Utility Measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Quality of life research. 2005;14(6):1523-1532. [CrossRef]

- Oyewole OO, Ogunlana MO, Gbiri CAO, et al. Impact of post-stroke disability and disability-perception on health-related quality of life of stroke survivors: the moderating effect of disability-severity. Neurological research (New York). 2020;42(10):835-843. [CrossRef]

- Tengs TO, Yu M, Luistro E. Health-related quality of life after stroke a comprehensive review. Stroke. 2001;32(4):964-972. [CrossRef]

- Barclay-Goddard RP, King JP, Dubouloz C-JP, et al. Building on Transformative Learning and Response Shift Theory to Investigate Health-Related Quality of Life Changes Over Time in Individuals With Chronic Health Conditions and Disability. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2012;93(2):214-220. [CrossRef]

- Barclay R, Tate RB. Response shift recalibration and reprioritization in health-related quality of life was identified prospectively in older men with and without stroke. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2014;67(5):500-507. [CrossRef]

- Wade DT. What is rehabilitation? An empirical investigation leading to an evidence-based description. Clinical rehabilitation. 2020;34(5):571-583. [CrossRef]

- Organization WH. World Report on Disability 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

- van Velzen JM, van Bennekom CAM, Edelaar MJA, et al. How many people return to work after acquired brain injury?: A systematic review. Brain injury. 2009;23(6):473-488.

- Burke V, O’Rourke L, Duffy E. Returning to work after acquired brain injury: A mixed method case study. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2021;55:297-312. [CrossRef]

- Kassberg A-C, Nyman A, Larsson Lund M. Perceived occupational balance in people with stroke. Disability and rehabilitation. 2021;43(4):553-558. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Rubio A, Cabrera-Martos I, Haro-Piedra E, et al. Exploring perceived occupational balance in women with fibromyalgia. A descriptive study. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 2022;29(5):395-402. [CrossRef]

- Wagman P, Hjärthag F, Håkansson C, et al. Factors associated with higher occupational balance in people with anxiety and/or depression who require occupational therapy treatment. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 2021;28(6):426-432. [CrossRef]

- Gasquoine PG. Blissfully unaware: Anosognosia and anosodiaphoria after acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological rehabilitation. 2016;26(2):261-285. [CrossRef]

- Synne Garder P, Oddgeir F, Guri Anita H, et al. Stroke-Specific Quality of life one-year post-stroke in two Scandinavian country-regions with different organisation of rehabilitation services : a prospective study. 2021.

- Cerniauskaite M, Quintas R, Koutsogeorgou E, et al. Quality-of-life and disability in patients with stroke. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2012;91(13 Suppl 1):S39-S47. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).