Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Our Approach

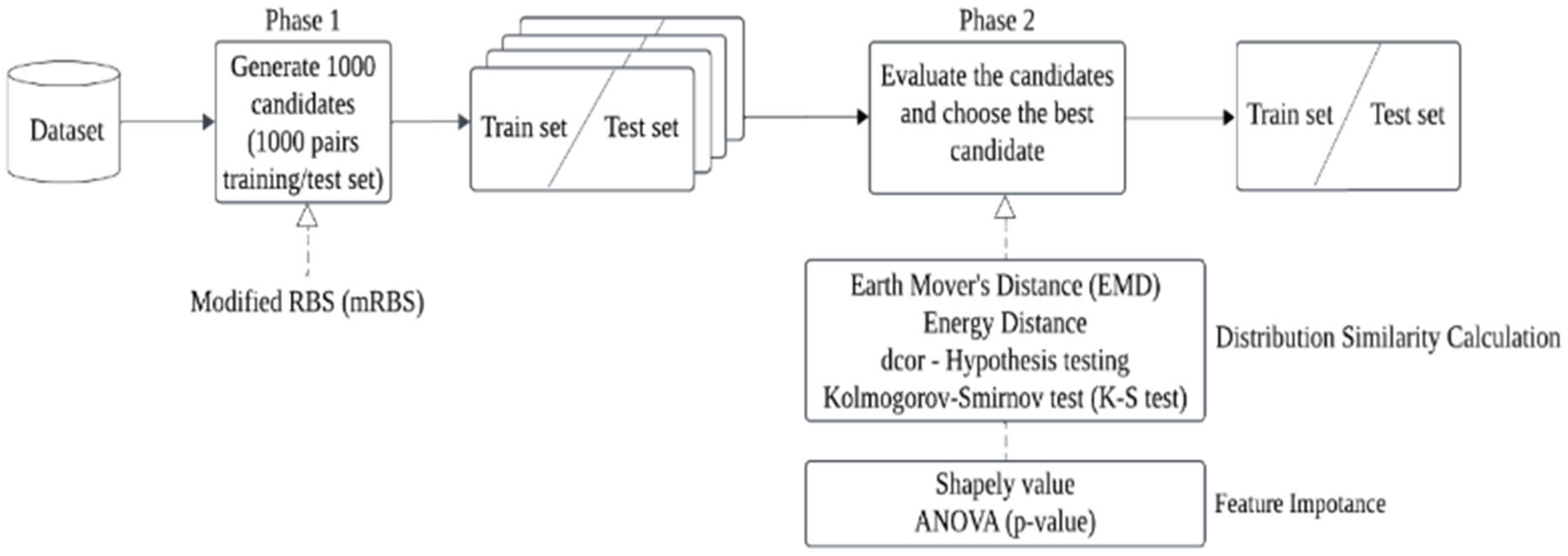

3.1. The Sampling Methods on the Dataset with Numerical Attributes

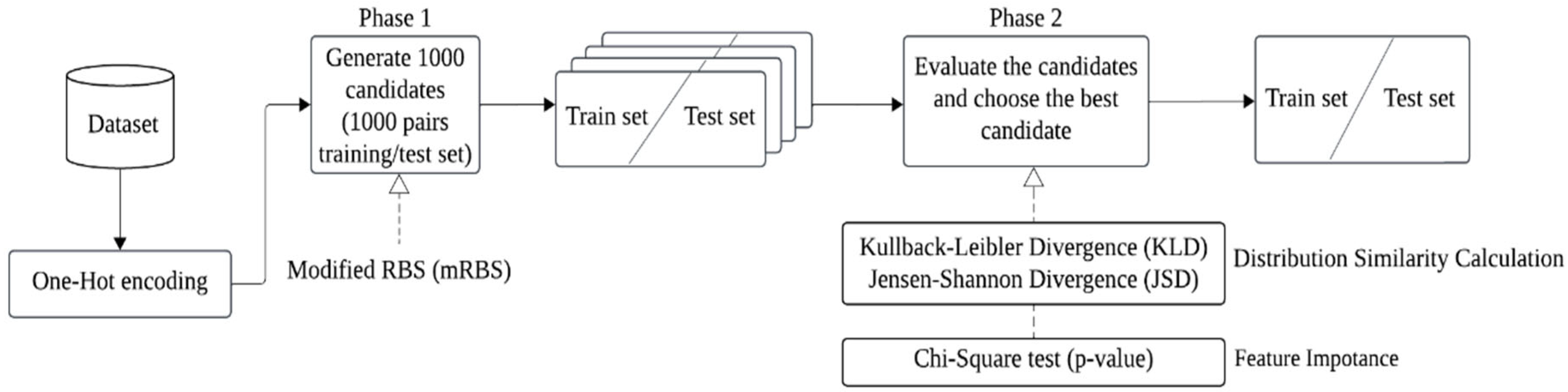

3.2. The Sampling Methods on the Dataset With Categorical Attributes

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Datasets and Classifiers

4.1. Evaluation Metric MAI

4.3. Experimental Results On Numerical Datasets

4.3. Experimental Results On Categorical Datasets

4.3. Experimental Results On Mix-Type Datasets

5. Conclusions

References

- P. C. Sen, M. Hajra, and M. Ghosh, "Supervised Classification Algorithms in Machine Learning: A Survey and Review," in Proceedings of IEM Graph, pp. 99-111, 2018.

- S. Rauschert, K. Raubenheimer, P. Melton, and R. Huang, "Machine Learning and Clinical Epigenetics: A Review of Challenges for Diagnosis and Classification," Clinical Epigenetics, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 1-11, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Henrique, V. A. Sobreiro, and H. Kimura, "Literature review: Machine Learning Techniques Applied to Financial Market Prediction," Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 124, pp. 226-251, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Kang and S. Oh, "Balanced training/test set Sampling for Proper Evaluation of Classification Models," Intelligent Data Analysis, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 5-18, 2020.

- A. E. Berndt, "Sampling methods," Journal of Human Lactation, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 224-226, 2020.

- H. Shin and S. Oh, "Feature-Weighted Sampling for Proper Evaluation of Classification Models," Applied Sciences, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp. 20-39, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Sharma, "Pros and Cons of Different Sampling Techniques," International Journal of Applied Research, Vol. 3, No. 7, pp. 749-752, 2017.

- S. J. Stratton, "Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies," Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 373-374, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Taherdoost, "Sampling Methods in Research Methodology; How to Choose a Sampling Technique for Research," International Journal of Academic Research in Management, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 18-27 2016.

- D. Bellhouse, "Systematic Sampling Methods," Encyclopedia of Biostatistics, pp. 4478-4482, 2005.

- V. L. Parsons, "Stratified Sampling," Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, pp. 1-11, 2014.

- E. J. Martin and R. E. Critchlow, "Beyond Mere Diversity: Tailoring Combinatorial Libraries for Drug Discovery," Journal of Combinatorial Chemistry, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 32-45, 1999. [CrossRef]

- B. D. Hudson, R. M. Hyde, E. Rahr, J. Wood, and J. Osman, "Parameter Based Methods for Compound Selection from Chemical Databases," Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 285-289, 1996. [CrossRef]

- S. Oh, "A New Dataset Evaluation Method Based on Category Overlap," Computers in Biology and Medicine, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 115-122, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Rubner, C. Tomasi, and L. J. Guibas, "The Earth Mover's Distance as a Metric for Image Retrieval," International Journal of Computer Vision, Vol. 40, pp. 99-121, 2000. [CrossRef]

- I. Covert, S. M. Lundberg, and S. I. Lee, "Understanding Global Feature Contributions with Additive Importance Measures," Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 33, pp. 17212-17223, 2020.

- D. Fryer, I. Strümke, and H. Nguyen, "Shapley Values for Feature Selection: The Good, the Bad, and the Axioms," IEEE Access, Vol. 9, pp. 144352-144360, 2021.

- M. L. Rizzo and G. J. Székely, "Energy Distance," Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 27-38, 2016.

- C. Ramos-Carreño and J. L. Torrecilla, "Dcor: Distance Correlation and Energy Statistics in Python," SoftwareX, Vol. 22, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Justel, D. Peña, and R. Zamar, "A Multivariate Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test of Goodness of Fit," Statistics & Probability Letters, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 251-259, 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. Kullback and R. A. Leibler, "On Information and Sufficiency," The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 79-86, 1951.

- M. Menéndez, J. Pardo, L. Pardo, and M. Pardo, "The Jensen-Shannon Divergence," Journal of the Franklin Institute, Vol. 334, No. 2, pp. 307-318, 1997.

- D. I. Belov and R. D. Armstrong, "Distributions of the Kullback–Leibler Divergence with Applications," British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp. 291-309, 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. Peker and C. Kubat, "Application of Chi-square Discretization Algorithms to Ensemble Classification Methods," Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 185, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y.S. Lee, S.J. Yen and Y.J. Tang, "Improved Sampling Methods for Evaluation of Classification Performance," Proceedings of 7th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication, pp.378-382, 2025.

| Dataset | # of instances | # of attributes | # of classes |

| breastcancer | 569 | N:30 | 2 |

| breastTissue | 106 | N:9 | 6 |

| ecoli | 336 | N:7 | 8 |

| pima_diabetes | 768 | N:8 | 2 |

| seed | 218 | N:8 | 3 |

| balance-scale | 625 | C:4 | 3 |

| congressional_voting_records | 435 | C:16 | 2 |

| Qualitative_Bankruptcy | 250 | C:6 | 2 |

| SPEC_Heart | 267 | C:22 | 2 |

| Vector_Borne_ Disease |

263 | C:64 | 11 |

| credit_approval | 690 | N:6, C:9 | 2 |

| Differentiated_Thyroid_Cancer _ Recurrence |

383 | N:1, C:15 | 2 |

| Fertility | 100 | N:3, C:6 | 2 |

| Heart_Disease | 303 | N:5, C:8 | 2 |

| Wholesale_customers _data |

440 | N:6, C:1 | 3 |

| Classifier | Parameter |

| Decision Tree (DT) | criterion='entropy', min_samples_leaf=2 |

| Random Forest (RF) | n_estimators=500, max_features='sqrt' |

| K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) | n_neighbors=5 |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | kernel='rbf' |

| Dataset | Classifier | AEV | SD |

| breastcaner | DT | 0.929 | 0.020 |

| KNN | 0.969 | 0.013 | |

| RF | 0.959 | 0.016 | |

| SVM | 0.976 | 0.012 | |

| breastTissue | DT | 0.655 | 0.086 |

| KNN | 0.639 | 0.085 | |

| RF | 0.684 | 0.082 | |

| SVM | 0.549 | 0.075 | |

| ecoli | DT | 0.797 | 0.043 |

| KNN | 0.855 | 0.034 | |

| RF | 0.862 | 0.033 | |

| SVM | 0.864 | 0.035 | |

| pima_diabetes | DT | 0.701 | 0.033 |

| KNN | 0.735 | 0.028 | |

| RF | 0.762 | 0.026 | |

| SVM | 0.767 | 0.027 | |

| seed | DT | 0.907 | 0.039 |

| KNN | 0.929 | 0.033 | |

| RF | 0.924 | 0.036 | |

| SVM | 0.931 | 0.031 |

| Dataset | Classifier | (FWS)EMD | Energy Distance | dcor-Hypothesis testing | K-S test |

| breastcancer | DT | 0.935 | 0.945 | 0.930 | 0.935 |

| KNN | 0.979 | 0.969 | 0.969 | 0.969 | |

| RF | 0.972 | 0.979 | 0.981 | 0.974 | |

| SVM | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.979 | |

| breastTissue | DT | 0.739 | 0.703 | 0.703 | 0.714 |

| KNN | 0.679 | 0.679 | 0.643 | 0.714 | |

| RF | 0.760 | 0.725 | 0.689 | 0.714 | |

| SVM | 0.669 | 0.561 | 0.633 | 0.597 | |

| ecoli | DT | 0.812 | 0.765 | 0.800 | 0.812 |

| KNN | 0.824 | 0.847 | 0.835 | 0.824 | |

| RF | 0.847 | 0.882 | 0.835 | 0.847 | |

| SVM | 0.835 | 0.882 | 0.871 | 0.835 | |

| pima_ | DT | 0.705 | 0.731 | 0.694 | 0.705 |

| diabetes | KNN | 0.741 | 0.705 | 0.679 | 0.736 |

| RF | 0.762 | 0.756 | 0.798 | 0.777 | |

| SVM | 0.772 | 0.782 | 0.808 | 0.803 | |

| seed | DT | 0.907 | 0.926 | 0.907 | 0.926 |

| KNN | 0.963 | 0.907 | 0.963 | 0.907 | |

| RF | 0.926 | 0.926 | 0.907 | 0.926 | |

| SVM | 0.963 | 0.907 | 0.926 | 0.944 |

| Dataset | Classifier | EMD | Energy Distance | dcor-Hypothesis testing | K-S test |

| breastcancer | DT | 0.951 | 0.902 | 0.937 | 0.923 |

| KNN | 0.972 | 0.965 | 0.951 | 0.965 | |

| RF | 0.951 | 0.958 | 0.965 | 0.958 | |

| SVM | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.972 | |

| breastTissue | DT | 0.500 | 0.714 | 0.643 | 0.750 |

| KNN | 0.607 | 0.643 | 0.607 | 0.714 | |

| RF | 0.643 | 0.750 | 0.679 | 0.679 | |

| SVM | 0.536 | 0.536 | 0.500 | 0.571 | |

| ecoli | DT | 0.812 | 0.824 | 0.765 | 0.835 |

| KNN | 0.823 | 0.894 | 0.882 | 0.847 | |

| RF | 0.859 | 0.894 | 0.847 | 0.871 | |

| SVM | 0.835 | 0.894 | 0.859 | 0.824 | |

| pima_ | DT | 0.731 | 0.710 | 0.710 | 0.710 |

| diabetes | KNN | 0.756 | 0.782 | 0.725 | 0.720 |

| RF | 0.808 | 0.751 | 0.798 | 0.756 | |

| SVM | 0.803 | 0.767 | 0.782 | 0.762 | |

| seed | DT | 0.889 | 0.926 | 0.907 | 0.944 |

| KNN | 0.944 | 0.889 | 0.944 | 0.907 | |

| RF | 0.963 | 0..907 | 0.963 | 0.907 | |

| SVM | 0.926 | 0.907 | 0.926 | 0.907 |

| Dataset | Classifier | (FWS)EMD | Energy Distance | dcor-Hypothesis testing | K-S test |

| breastcancer | DT | 0.286 | 0.748 | 0.059 | 0.286 |

| KNN | 0.918 | 0.139 | 0.139 | 0.139 | |

| RF | 0.818 | 1.253 | 1.356 | 0.921 | |

| SVM | 0.289 | 0.289 | 0.282 | 0.282 | |

| breastTissue | DT | 0.977 | 0.560 | 0.560 | 0.691 |

| KNN | 0.462 | 0.462 | 0.044 | 0.880 | |

| RF | 0.935 | 0.499 | 0.064 | 0.372 | |

| SVM | 1.592 | 0.171 | 1.118 | 0.302 | |

| ecoli | DT | 0.347 | 0.756 | 0.071 | 0.347 |

| KNN | 0.946 | 0.250 | 0.598 | 0.946 | |

| RF | 0.460 | 0.606 | 0.598 | 0.460 | |

| SVM | 0.825 | 0.519 | 0.183 | 0.825 | |

| pima_ | DT | 0.732 | 1.205 | 0.102 | 0.260 |

| diabetes | KNN | 0.228 | 0.978 | 0.710 | 0.603 |

| RF | 0.369 | 0.369 | 1.170 | 1.033 | |

| SVM | 0.962 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.182 | |

| seed | DT | 0.020 | 0.490 | 0.020 | 0.490 |

| KNN | 1.039 | 0.655 | 1.039 | 0.655 | |

| RF | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.463 | 0.047 | |

| SVM | 1.038 | 0.740 | 0.147 | 0.445 | |

| Average | MAI | 0.665 | 0.537 | 0.437 | 0.508 |

| Dataset | Classifier | EMD | Energy Distance | dcor-Hypothesis testing | K-S test |

| breastcancer | DT | 0.286 | 0.631 | 0.403 | 0.286 |

| KNN | 0.668 | 0.668 | 1.196 | 0.918 | |

| RF | 0.487 | 0.052 | 0.383 | 0.487 | |

| SVM | 0.289 | 0.289 | 0.289 | 0.282 | |

| breastTissue | DT | 0.977 | 1.525 | 0.143 | 0.977 |

| KNN | 0.374 | 0.044 | 0.374 | 0.462 | |

| RF | 0.935 | 0.808 | 0.372 | 0.499 | |

| SVM | 0.171 | 0.171 | 0.645 | 0.645 | |

| ecoli | DT | 0.071 | 0.347 | 0.071 | 0.899 |

| KNN | 0.946 | 1.144 | 0.796 | 0.250 | |

| RF | 0.460 | 0.961 | 0.460 | 0.251 | |

| SVM | 0.825 | 0.855 | 0.153 | 1.161 | |

| pima_ | DT | 1.473 | 0.260 | 0.056 | 1.205 |

| diabetes | KNN | 0.148 | 1.728 | 0.603 | 0.148 |

| RF | 1.233 | 0.032 | 0.169 | 0.833 | |

| SVM | 0.989 | 0.013 | 0.767 | 0.989 | |

| seed | DT | 0.450 | 0.490 | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| KNN | 0.474 | 1.220 | 0.474 | 1.039 | |

| RF | 1.067 | 0.463 | 1.067 | 0.557 | |

| SVM | 0.147 | 0.740 | 0.147 | 1.038 | |

| Average | MAI | 0.626 | 0.622 | 0.429 | 0.647 |

| Dataset | Classifier | AEV | SD |

| balance-scale | DT | 0.745 | 0.034 |

| KNN | 0.744 | 0.030 | |

| RF | 0.845 | 0.026 | |

| SVM | 0.862 | 0.025 | |

| congressional_voting | DT | 0.951 | 0.025 |

| _records | KNN | 0.922 | 0.032 |

| RF | 0.963 | 0.021 | |

| SVM | 0.963 | 0.022 | |

| Qualitative_ | DT | 0.995 | 0.012 |

| Bankruptcy | KNN | 0.996 | 0.008 |

| RF | 0.9995 | 0.005 | |

| SVM | 0.996 | 0.009 | |

| SPEC_Heart | DT | 0.747 | 0.049 |

| KNN | 0.796 | 0.046 | |

| RF | 0.824 | 0.040 | |

| SVM | 0.828 | 0.041 | |

| Vector_Borne | DT | 0.709 | 0.064 |

| _Disease | KNN | 0.673 | 0.057 |

| RF | 0.934 | 0.030 | |

| SVM | 0.914 | 0.037 |

| Dataset | Classifier | KLD |

KLD |

JSD | FWS (EMD Shapely) |

| balance-scale | DT | 0.741 | 0.722 | 0.734 | 0.747 |

| KNN | 0.747 | 0.747 | 0.747 | 0.747 | |

| RF | 0.823 | 0.848 | 0.829 | 0.816 | |

| SVM | 0.816 | 0.816 | 0.816 | 0.816 | |

| congressional_ | DT | 0.949 | 0.949 | 0.949 | 0.898 |

| voting _records | KNN | 0.915 | 0.915 | 0.915 | 0.949 |

| RF | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.966 | |

| SVM | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.966 | |

| Qualitative_ | DT | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| _Bankruptcy | KNN | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.984 |

| RF | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| SVM | 0.984 | 0.984 | 0.984 | 1.000 | |

| SPEC_Heart | DT | 0.716 | 0.716 | 0.761 | 0.761 |

| KNN | 0.776 | 0.776 | 0.776 | 0.821 | |

| RF | 0.776 | 0.791 | 0.791 | 0.791 | |

| SVM | 0.821 | 0.821 | 0.821 | 0.791 | |

| Vector_Borne | DT | 0.761 | 0.761 | 0.776 | 0.761 |

| _Disease | KNN | 0.687 | 0.687 | 0.687 | 0.687 |

| RF | 0.940 | 0.955 | 0.940 | 0.955 | |

| SVM | 0.955 | 0.955 | 0.955 | 0.955 |

| Dataset | Classifier | KLD |

KLD |

JSD | FWS (EMD Shapely) |

| balance-scale | DT | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.478 | 0.064 |

| KNN | 0.795 | 0.795 | 0.795 | 0.098 | |

| RF | 0.272 | 0.818 | 0.272 | 1.078 | |

| SVM | 0.673 | 0.673 | 0.673 | 1.825 | |

| congressional_ | DT | 0.088 | 0.088 | 0.088 | 2.141 |

| voting _records | KNN | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.853 |

| RF | 0.974 | 0.974 | 0.974 | 0.165 | |

| SVM | 0.921 | 0.921 | 0.921 | 0.154 | |

| Qualitative_ | DT | 0.474 | 0.474 | 0.474 | 0.474 |

| _Bankruptcy | KNN | 0.548 | 0.548 | 0.548 | 1.503 |

| RF | 0.087 | 0.087 | 0.087 | 0.087 | |

| SVM | 1.335 | 1.335 | 1.335 | 0.467 | |

| SPEC_Heart | DT | 0.626 | 0.626 | 0.286 | 0.286 |

| KNN | 0.429 | 0.429 | 0.429 | 0.536 | |

| RF | 1.193 | 0.817 | 0.817 | 0.817 | |

| SVM | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.902 | |

| Vector_Borne | DT | 0.806 | 0.806 | 1.039 | 0.806 |

| _Disease | KNN | 0.234 | 0.234 | 0.234 | 0.234 |

| RF | 0.205 | 0.704 | 0.205 | 0.704 | |

| SVM | 1.121 | 1.121 | 1.121 | 1.121 | |

| Average | MAI | 0.601 | 0.635 | 0.557 | 0.716 |

| Dataset | Classifier | ACC | SD |

| credit_approval | DT | 0.817 | 0.029 |

| KNN | 0.862 | 0.024 | |

| RF | 0.873 | 0.023 | |

| SVM | 0.862 | 0.023 | |

| Differentiated_ | DT | 0.942 | 0.022 |

| Thyroid_Cancer_ | KNN | 0.922 | 0.027 |

| Recurrence | RF | 0.960 | 0.017 |

| SVM | 0.955 | 0.019 | |

| Fertility | DT | 0.846 | 0.064 |

| KNN | 0.853 | 0.055 | |

| RF | 0.869 | 0.057 | |

| SVM | 0.881 | 0.057 | |

| Heart_Disease | DT | 0.749 | 0.048 |

| KNN | 0.829 | 0.038 | |

| RF | 0.822 | 0.038 | |

| SVM | 0.839 | 0.037 | |

| Wholesale_customers | DT | 0.524 | 0.045 |

| _data | KNN | 0.635 | 0.037 |

| RF | 0.709 | 0.036 | |

| SVM | 0.718 | 0.037 |

| Dataset | Classifier | Our hybrid method (Accuracy) |

dcor-Hypothesis testing ANOVA (Accuracy) |

Our hybrid method (MAI) | dcor-Hypothesis testing ANOVA (MAI) |

| credit_approval | DT | 0.793 | 0.768 | 0.828 | 1.669 |

| KNN | 0.896 | 0.896 | 1.414 | 1.414 | |

| RF | 0.854 | 0.866 | 0.867 | 0.329 | |

| SVM | 0.854 | 0.854 | 0.376 | 0.376 | |

| Differentiated_ | DT | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.189 | 0.189 |

| Thyroid_Cancer_ | KNN | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.596 | 0.596 |

| Recurrence | RF | 0.948 | 0.948 | 0.699 | 0.699 |

| SVM | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.910 | 0.910 | |

| Fertility | DT | 0.885 | 0.885 | 0.610 | 0.610 |

| KNN | 0.808 | 0.808 | 0.820 | 0.820 | |

| RF | 0.846 | 0.846 | 0.398 | 0.398 | |

| SVM | 0.885 | 0.885 | 0.059 | 0.059 | |

| Heart_Disease | DT | 0.792 | 0.805 | 0.903 | 1.172 |

| KNN | 0.870 | 0.870 | 1.085 | 1.085 | |

| RF | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.918 | 0.918 | |

| SVM | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.486 | 0.486 | |

| Wholesale_ | DT | 0.495 | 0.514 | 0.633 | 0.228 |

| customers _data | KNN | 0.676 | 0.676 | 1.105 | 1.105 |

| RF | 0.712 | 0.703 | 0.096 | 0.152 | |

| SVM | 0.739 | 0.739 | 0.558 | 0.558 | |

| Average | MAI | 0.678 | 0.689 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).