Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. Universal Residue Labels of Kv7.1 and Its Paralogs

2.2. Composing a Broad Dataset of Missense Variants for Channel hKv7.1 and Its Paralogues

2.3. Distribution of Missense Variants in Topological Regions of hKv7.1

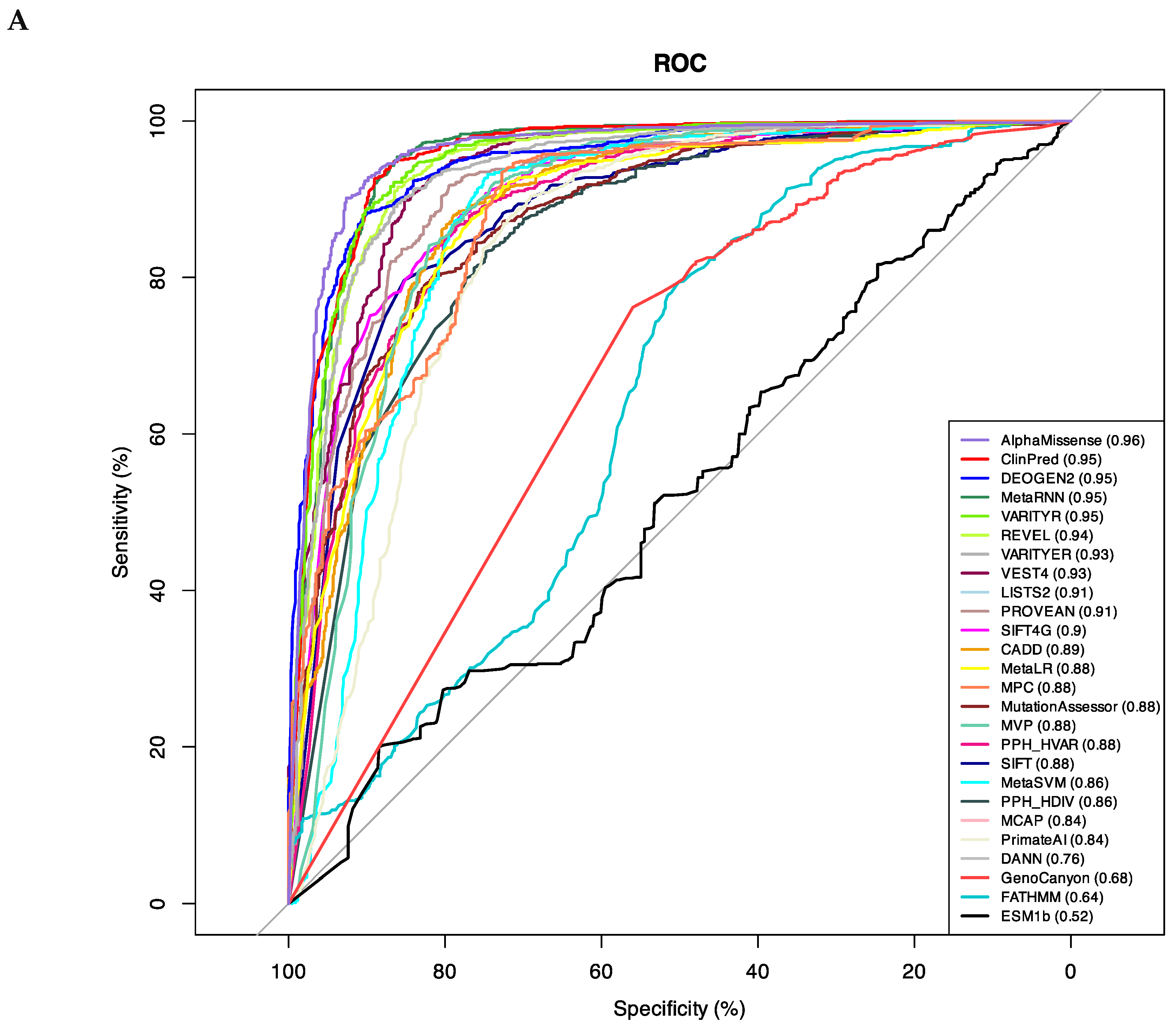

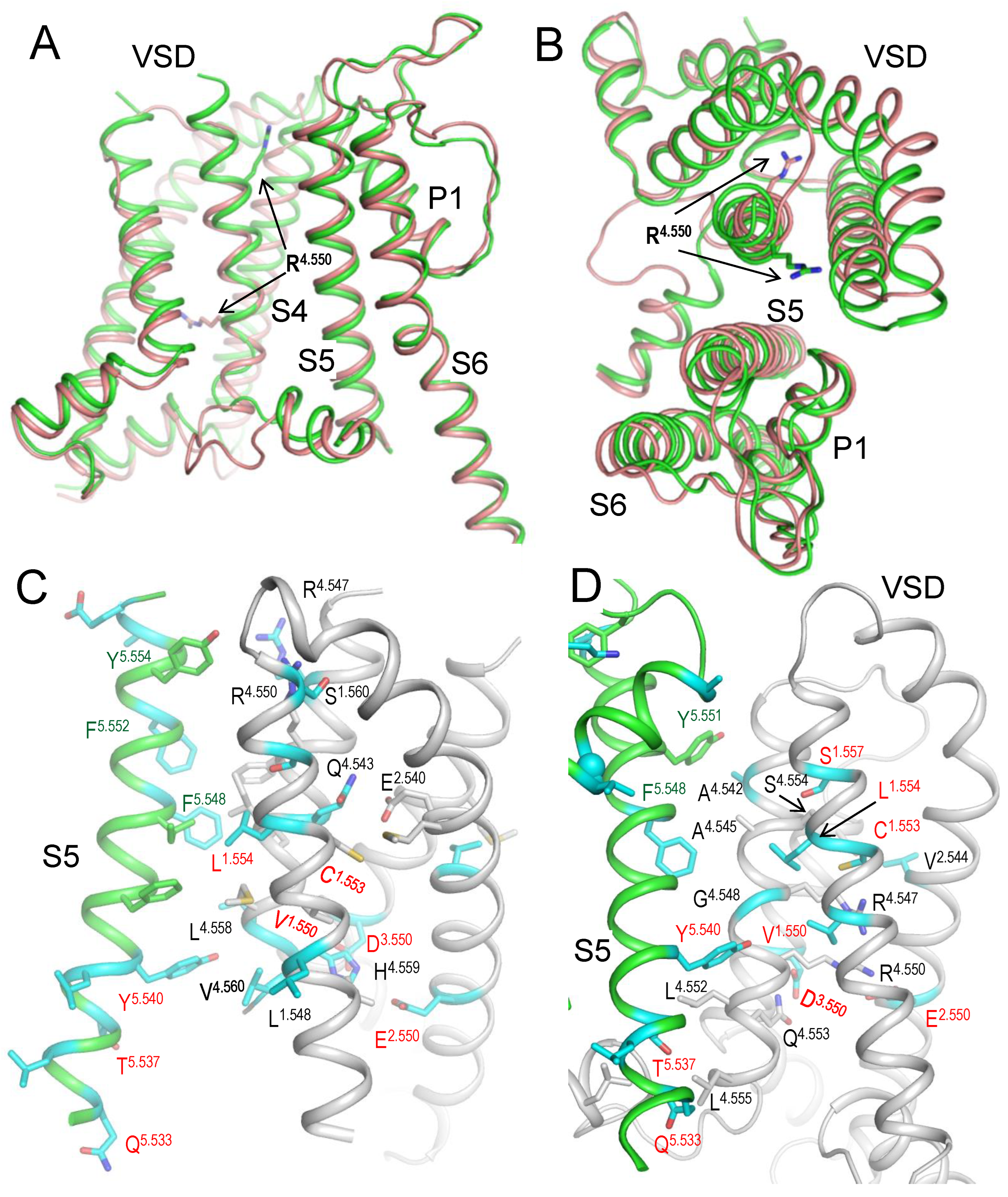

2.4. Comparing Performance of Bioinformatics Tools

2.5. Paralogue Annotation of Kv7.1 Variants

2.6. AlphaMissense and Paralogues Annotations Consensually Predicted Pathogenicity of 79 VUS

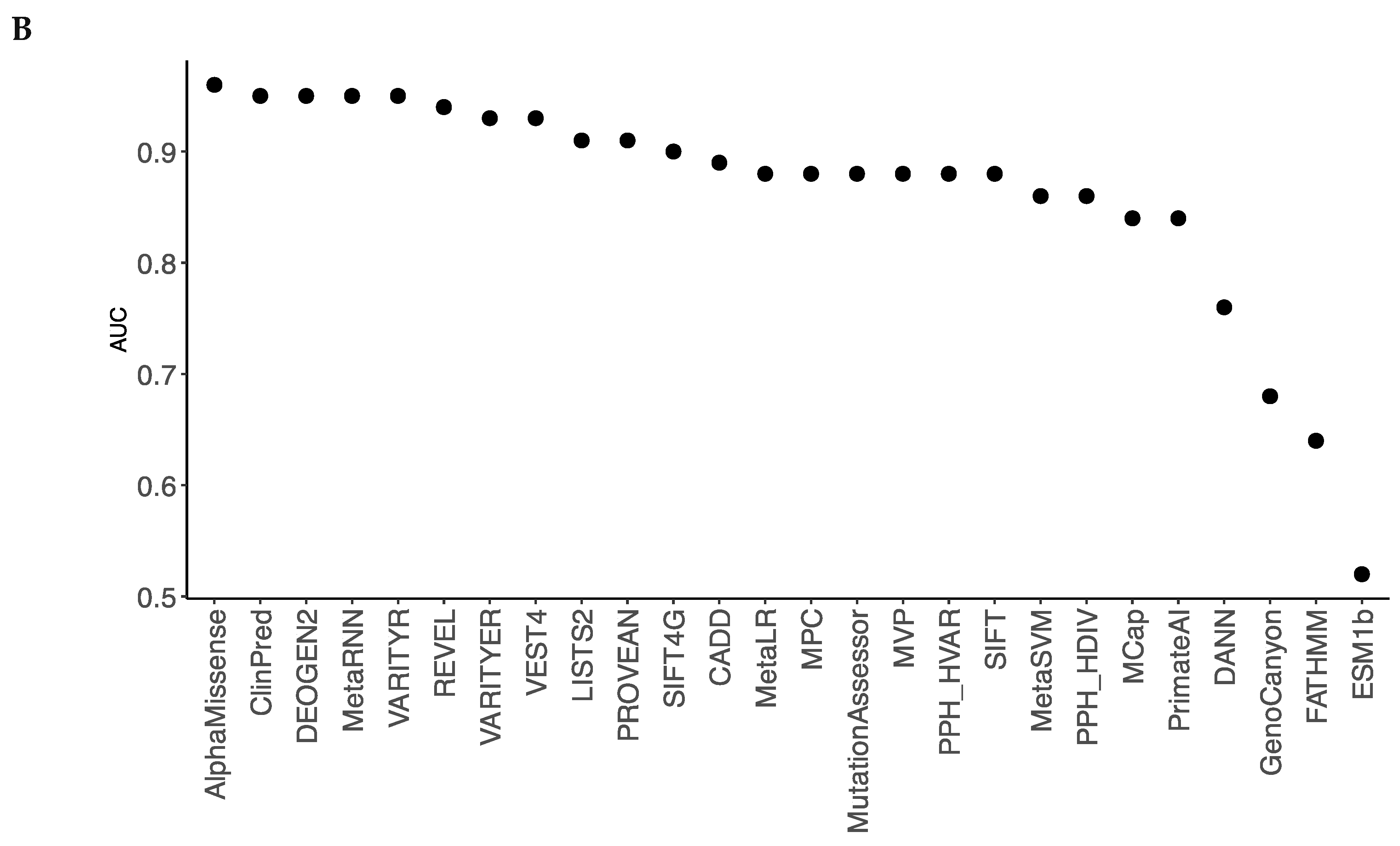

2.7. Intersegment Contacts Involving WTRs with LP-Reclassified VUSs

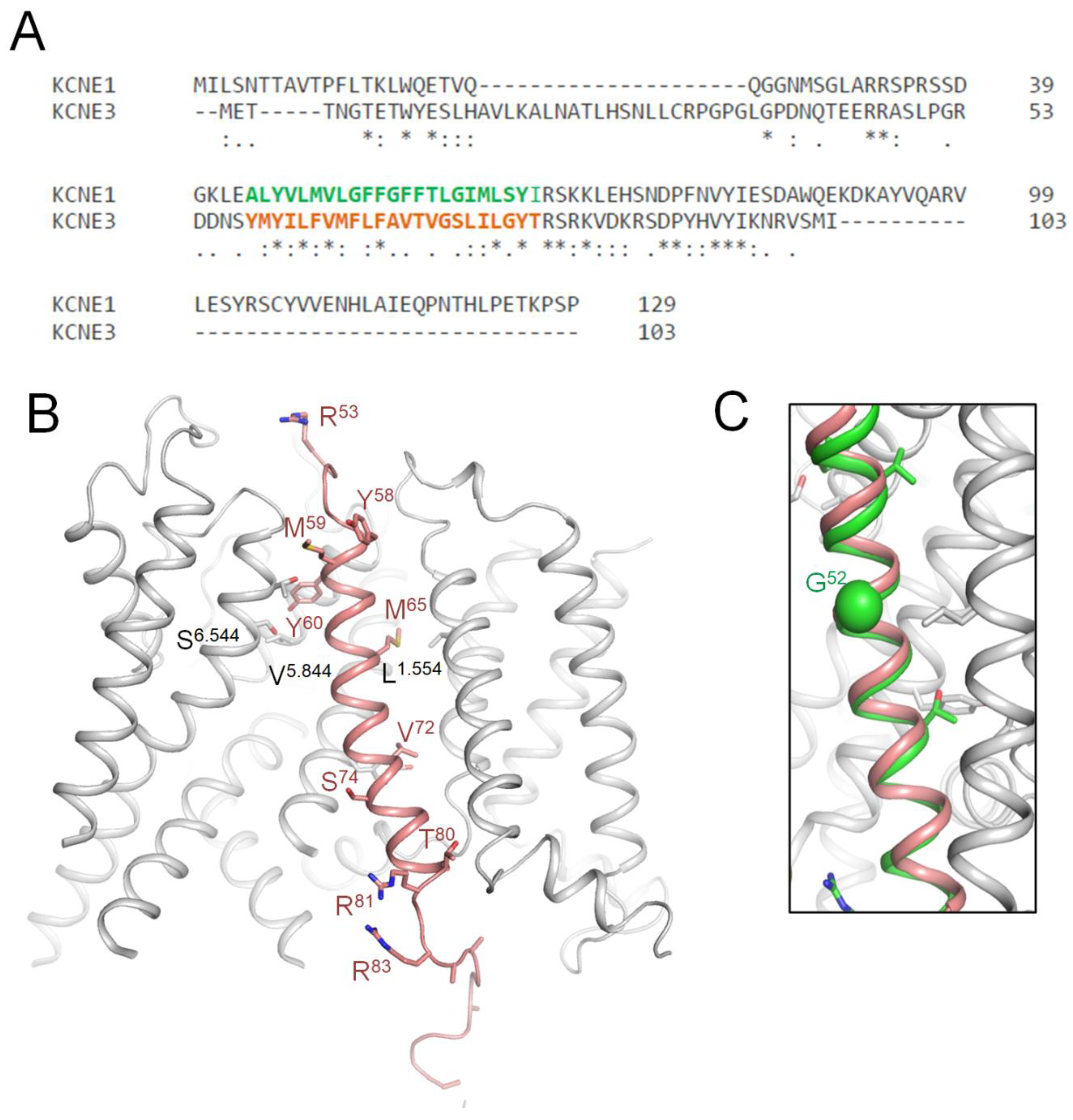

2.8. Re-Classifying KCNE1 VUSs with High ClinPred Score and ClinVar-Reported Variants in Sequentially Matching Positions of Paralogues

2.9. AF3 Model of Kv7.1 with KCNE1

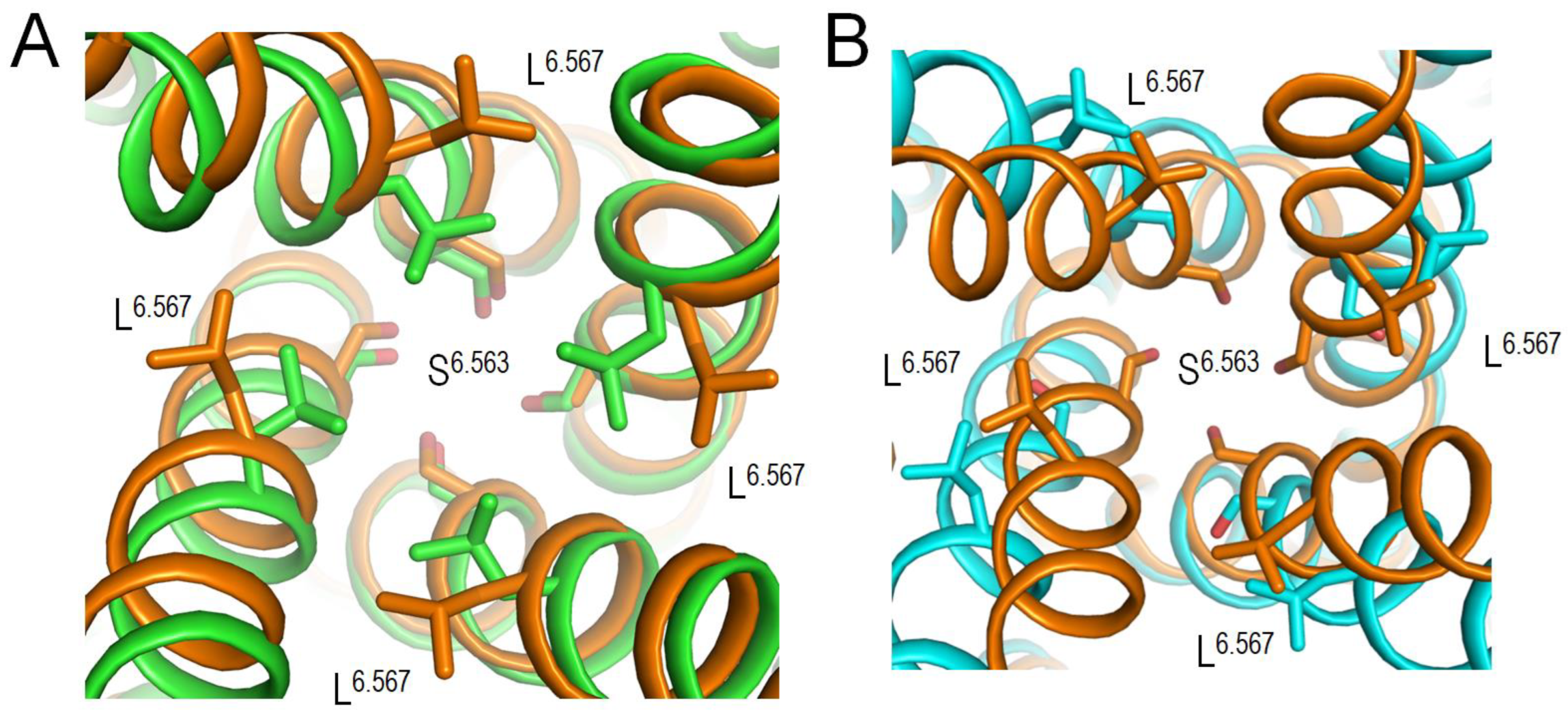

2.10. CryoEM Structure of KCNE3-Bound Kv7.1

3. Methods

3.1. Sequence Data of Human Channels and Collection of Variants

3.2. Topology of the Kv7.1 Channel

3.3. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Paralogue Annotation

3.4. Sequence-Based Prediction of Pathogenicity

3.5. Molecular Modeling

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve |

| CIP | Conflicting interpretation of pathogenicity |

| LQTS | Long QT syndrome |

| MC | Monte Carlo |

| NP | germline classification of pathogenicity is not provided |

| P/LP | Pathogenic/Likely pathogenic variant |

| PLIC | P-loop ion channels |

| TM | Transmembrane |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| VSD | Voltage-sensing domain |

| VUS | Variant of Unknown clinical significance |

| WTR | Wild-Type Residue |

References

- Abbott GW (2016) KCNE1 and KCNE3: The yin and yang of voltage-gated K(+) channel regulation. Gene 576(1 Pt 1): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Abbott JW (2014) Biology of the KCNQ1 Potassium Channel. New Journal of Science 2014(237431): 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Albert CM, et al. (2010) Common variants in cardiac ion channel genes are associated with sudden cardiac death. Circulation Arrhythmia and electrophysiology 3(3): 222-229. [CrossRef]

- Bains S, et al. (2024) KCNQ1 suppression-replacement gene therapy in transgenic rabbits with type 1 long QT syndrome. European heart journal 45(36): 3751-3763. [CrossRef]

- Barro-Soria R, Perez ME and Larsson HP (2015) KCNE3 acts by promoting voltage sensor activation in KCNQ1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(52): E7286-7292. [CrossRef]

- Bellocq C, et al. (2004) Mutation in the KCNQ1 gene leading to the short QT-interval syndrome. Circulation 109(20): 2394-2397. [CrossRef]

- Boutet E, et al. (2016) UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, the Manually Annotated Section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase: How to Use the Entry View. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 1374: 23-54. [CrossRef]

- Brewer KR, et al. (2025) Integrative analysis of KCNQ1 variants reveals molecular mechanisms of type 1 long QT syndrome pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 122(8): e2412971122. [CrossRef]

- Campuzano O, et al. (2015) Genetics of channelopathies associated with sudden cardiac death. Global cardiology science & practice 2015(3): 39. [CrossRef]

- Chen YH, et al. (2003) KCNQ1 gain-of-function mutation in familial atrial fibrillation. Science 299(5604): 251-254. [CrossRef]

- Dyer SC, et al. (2025) Ensembl 2025. Nucleic Acids Res 53(D1): D948-D957. [CrossRef]

- Garden DP and Zhorov BS (2010) Docking flexible ligands in proteins with a solvent exposure- and distance-dependent dielectric function. Journal of computer-aided molecular design 24(2): 91-105. [CrossRef]

- Gigolaev AM, et al. (2025) Golden Gate cloning enables efficient concatemer construction for biophysical analysis of heterozygous potassium channel variants from patients with epilepsy. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules In Press. [CrossRef]

- Golicz A, et al. (2018) AACon: A Fast Amino Acid Conservation Calculation Service. Submitted paper.

- Haitin Y, et al. (2009) Intracellular domains interactions and gated motions of I(KS) potassium channel subunits. The EMBO journal 28(14): 1994-2005. [CrossRef]

- Hateley S, et al. (2021) The history and geographic distribution of a KCNQ1 atrial fibrillation risk allele. Nature communications 12(1): 6442. [CrossRef]

- Huang H, et al. (2018) Mechanisms of KCNQ1 channel dysfunction in long QT syndrome involving voltage sensor domain mutations. Science advances 4(3): eaar2631. [CrossRef]

- Jespersen T, Grunnet M and Olesen SP (2005) The KCNQ1 potassium channel: from gene to physiological function. Physiology 20: 408-416. [CrossRef]

- Kaltman JR, Evans F and Fu Y-P (2018) Re-evaluating pathogenicity of variants associated with the long QT syndrome. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 29(1): 98-104. [CrossRef]

- Karczewski KJ, et al. (2020) The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581(7809): 434-443. [CrossRef]

- Kasuya G and Nakajo K (2022) Optimized tight binding between the S1 segment and KCNE3 is required for the constitutively open nature of the KCNQ1-KCNE3 channel complex. eLife 11. [CrossRef]

- Kekenes-Huskey PM, et al. (2022) Mutation-Specific Differences in Kv7.1 (KCNQ1) and Kv11.1 (KCNH2) Channel Dysfunction and Long QT Syndrome Phenotypes. International journal of molecular sciences 23(13). [CrossRef]

- Kiper AK, et al. (2024) KCNQ1 is an essential mediator of the sex-dependent perception of moderate cold temperatures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 121(25): e2322475121. [CrossRef]

- Korkosh VS, et al. (2021) Intersegment Contacts of Potentially Damaging Variants of Cardiac Sodium Channel. Frontiers in pharmacology 12: 756415. [CrossRef]

- Landrum MJ, et al. (2016) ClinVar: Public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Research 44(D1): D862-D868. [CrossRef]

- Li Z and Scheraga HA (1987) Monte Carlo-minimization approach to the multiple-minima problem in protein folding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84(19): 6611-6615. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, et al. (2020) dbNSFP v4: a comprehensive database of transcript-specific functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Genome Med 12(1): 103. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone CD and Barton GJ (1993) Protein sequence alignments: a strategy for the hierarchical analysis of residue conservation. Computer applications in the biosciences : CABIOS 9(6): 745-756. [CrossRef]

- Long SB, et al. (2007) Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature 450(7168): 376-382. [CrossRef]

- Lundquist AL, et al. (2005) Expression of multiple KCNE genes in human heart may enable variable modulation of I(Ks). Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 38(2): 277-287. [CrossRef]

- Mandala VS and MacKinnon R (2023) The membrane electric field regulates the PIP(2)-binding site to gate the KCNQ1 channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120(21): e2301985120. [CrossRef]

- Niroula A and Vihinen M (2016) Variation Interpretation Predictors: Principles, Types, Performance, and Choice. Human Mutation 37(6): 579-597. [CrossRef]

- Phul S, et al. (2022) Predicting the functional impact of KCNQ1 variants with artificial neural networks. PLoS computational biology 18(4): e1010038. [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg I, et al. (2016) Structural interplay of K(V)7.1 and KCNE1 is essential for normal repolarization and is compromised in short QT syndrome 2 (K(V)7.1-A287T). HeartRhythm case reports 2(6): 521-529. [CrossRef]

- Sachyani D, et al. (2014) Structural basis of a Kv7.1 potassium channel gating module: studies of the intracellular c-terminal domain in complex with calmodulin. Structure 22(11): 1582-1594. [CrossRef]

- Sanguinetti MC and Seebohm G (2021) Physiological Functions, Biophysical Properties, and Regulation of KCNQ1 (K(V)7.1) Potassium Channels. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 1349: 335-353. [CrossRef]

- Sievers F, et al. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7: 539. [CrossRef]

- Sun J and MacKinnon R (2017) Cryo-EM Structure of a KCNQ1/CaM Complex Reveals Insights into Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Cell 169(6): 1042-1050 e1049.

- Sun J and MacKinnon R (2020) Structural Basis of Human KCNQ1 Modulation and Gating. Cell 180(2): 340-347 e349.

- Tarnovskaya SI, et al. (2020) Predicting novel disease mutations in the cardiac sodium channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 521(3): 603-611. [CrossRef]

- Tarnovskaya SI, Kostareva AA and Zhorov BS (2021) L-Type Calcium Channel: Predicting Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic Status for Variants of Uncertain Clinical Significance. Membranes (Basel) 11(8). [CrossRef]

- Tarnovskaya SI, Kostareva AA and Zhorov BS (2023) In silico analysis of TRPM4 variants of unknown clinical significance. PLoS One 18(12): e0295974. [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov DB, Korkosh VS and Zhorov BS (2025) 3D-aligned tetrameric ion channels with universal residue labels for comparative structural analysis. Biophysical journal 124(2): 458-470.

- UniProt C (2015) UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res 43(Database issue): D204-212. [CrossRef]

- Vanoye CG, et al. (2018) High-Throughput Functional Evaluation of KCNQ1 Decrypts Variants of Unknown Significance. Circulation Genomic and precision medicine 11(11): e002345. [CrossRef]

- Vanoye CG, et al. (2025) Functional profiling of KCNE1 variants informs population carrier frequency of Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome type 2. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Walsh R, et al. (2014) Paralogue annotation identifies novel pathogenic variants in patients with Brugada syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Journal of medical genetics 51(1): 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Walsh R, et al. (2017) Reassessment of Mendelian gene pathogenicity using 7,855 cardiomyopathy cases and 60,706 reference samples. Genet Med 19(2): 192-203. [CrossRef]

- Weiner SJ, et al. (1986) An all atom force field for simulations of proteins and nucleic acids. Journal of computational chemistry 7(2): 230-252. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel E, Tapken D and Seebohm G (2012) The KCNE Tango - How KCNE1 Interacts with Kv7.1. Frontiers in pharmacology 3: 142. [CrossRef]

- Wu X and Larsson HP (2020) Insights into Cardiac IKs (KCNQ1/KCNE1) Channels Regulation. International journal of molecular sciences 21(24). [CrossRef]

- Zhorov BS (1981) Vector method for calculating derivatives of energy of atom-atom interactions of complex molecules according to generalized coordiantes. J Struct Chem 22: 4-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhorov BS (2021) Possible Mechanism of Ion Selectivity in Eukaryotic Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. The journal of physical chemistry B 125(8): 2074-2088. [CrossRef]

- Zvelebil MJ, et al. (1987) Prediction of protein secondary structure and active sites using the alignment of homologous sequences. J Mol Biol 195(4): 957-961. [CrossRef]

| Gene a | UniProt IDb | P/LP c | VUS d |

Common neutral e |

| KCNA1 | Q09470 | 38 | 245 | 14 |

| KCNA2 | P16389 | 44 | 207 | 10 |

| KCNA5 | P22460 | 4 | 276 | 56 |

| KCNB1 | Q14721 | 87 | 212 | 62 |

| KCNC1 | P48547 | 11 | 149 | 11 |

| KCNC2 | Q96PR1 | 12 | 44 | 37 |

| KCNC3 | Q14003 | 10 | 173 | 82 |

| KCND2 | Q9NZV8 | 7 | 176 | 22 |

| KCND3 | Q9UK17 | 21 | 207 | 17 |

| KCNQ1 | P51787 | 299 | 519 | 43 |

| KCNQ2 | O43526 | 394 | 474 | 57 |

| KCNQ3 | O43525 | 39 | 458 | 49 |

| KCNQ4 | P56696 | 28 | 153 | 63 |

| KCNQ5 | Q9NR82 | 20 | 228 | 65 |

| KCNV2 | Q8TDN2 | 45 | 361 | 103 |

| Tool |

Deleterious Threshold a |

Sensitivity b | Specificity c | MCC d | ACC e | AUC f |

| AlphaMissense | >0.5 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.9 | 0.96 |

| ClinPred | >0.8 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.95 |

| DEOGEN2 | >0.5 | 0.96 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.95 |

| MetaRNN | >0.6 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| VARITYR | >0.5 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.95 |

| REVEL | >0.45 | 0.99 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.76 | 0.94 |

| VARITYER | >0.5 | 0.9 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

| VEST4 | >0.5 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.93 |

| LISTS2 | >0.85 | 0.97 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.91 |

| PROVEAN | <-1.5 | 0.96 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.78 | 0.91 |

| SIFT4G | <0.05 | 0.9 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.82 | 0.9 |

| CADD | >3 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.8 | 0.89 |

| MetaLR | >0.4 | 0.99 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.54 | 0.88 |

| MPC | >2 | 0.57 | 0.92 | 0.51 | 0.74 | 0.88 |

| MutationAssessor | >1.7 | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

| MVP | >0.75 | 0.99 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.68 | 0.88 |

| PPH_HVAR | >0.45 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.79 | 0.88 |

| SIFT | <0.0045 | 0.82 | 0.8 | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.88 |

| MetaSVM | >0 | 0.99 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.61 | 0.86 |

| PPH_HDIV | >0.45 | 0.93 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.73 | 0.86 |

| MCap | >0.05 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.57 | 0.84 |

| PrimateAI | >0.6 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.84 |

| DANN | >0.5 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.52 | 0.76 |

| GenoCanyon | >0.7 | 0.89 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.62 | 0.68 |

| FATHMM | <-1 | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.5 | 0.64 |

| ESM1b | <-3 | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.52 |

|

PLIC Label |

hKv7.1 variant |

Paralog | ClinPred | α missense |

Current Change b |

| 1.532 | E115D | KCNQ2-E86K | 0.878 | 0.997 | |

| 1.545 | A128P | KCNQ2-Y98X | 0.185 | 0.861 | |

| 1.548 | L131P | KCNQ2-L101H | 0.995 | 0.958 | ↓↓ |

| 1.550 | V133A | KC NA1-I177N,KCNB1-I199F, KCNQ2-V103D |

0.984 | 0.964 | ↓ |

| 1.553 | C136F | KCNQ2-C106G | 1 | 0.954 | ↓↓ |

| 1.554 | L137 P | KCNQ2-L107F | 0.986 | 0.999 | |

| 1.557 | S140R | KCNA1-F184C | 0.996 | 0.999 | ↓↓ |

| 1.560 | S143F | KCNB1-N209K | 0.997 | 0.953 | |

| 2.544 | V164A | KCNQ2-I134N | 0.998 | 0.797 | |

| 2.550 | E170G | KCNQ2-E140A | 1 | 0.987 | |

| 2.551 | Y171H | KCNV2-Y317X | 0.998 | 0.998 | |

| 2.556 | W176S | KCNQ2-W146X | 1 | 0.926 | |

| 2.609 | G189A | KCNQ2-G159E/R/V | 0.998 | 0.978 | ↓↓ |

| 3.549 | I201V | KCNA2-I258N | 0.944 | 0.507 | |

| 3.550 | D202V | KCNQ2-D172G | 1 | 0.998 | |

| 3.560 | V212A | KCNQ2-V182M | 0.994 | 0.958 | |

| 3.560 | V212F | KCNQ2-V182M | 0.997 | 0.917 | |

| 3.600 | G219E | KCNA1-E283K,KCNQ2-G189D | 0.989 | 0.817 | |

| 4.542 | A223T | KCNQ2-A193D/V | 0.994 | 0.772 | |

| 4.547 | R228W | KCNA2-R294H,KCNQ2-R198W | 1 | 0.966 | |

| 4.553 | Q234L | KCNA2-R300S, KCNB1-R303Q, KCNC3-R420H, KCNQ2-Q204H |

0.998 | 0.965 | |

| 4.553 | Q234R | KCNA2-R300S, KCNB1-R303Q, KCNC3-R420H, KCNQ2-Q204H |

0.97 | 0.992 | |

| 4.558 | L239V | KCNQ2-I209S/T | 0.829 | 0.86 | |

| 4.559 | H240R | KCNQ2-R210C/H/P | 0.331 | 0.949 | |

| 4.559 | H240Q | KCNQ2-R210C/H/P | 0.993 | 0.991 | |

| 5.518 | G245R | KCND3-S304F | 0.998 | 0.998 | ↓↓ |

| 5.523 | L250P | KCNA1-I314T,KCNB1-S319F/Y | 0.995 | 1 | |

| 5.525 | G252R | KCNB1-G321S | 1 | 0.996 | |

| 5.525 | G252S | KCNB1-G321S | 0.998 | 0.885 | |

| 5.526 | S253A | KCNQ2-S223F/P | 0.972 | 0.792 | |

| 5.530 | I257S | KCNQ2-A227V | 0.993 | 0.947 | |

| 5.533 | Q260H | KCNQ2-K230M | 0.991 | 0.99 | |

| 5.535 | L262V | KCNC3-F448L | 0.996 | 0.952 | |

| 5.536 | I263K | KCNB1-G332V | 0.997 | 0.997 | |

| 5.537 | T264S | KCNQ2-T234A/P | 0.992 | 0.895 | |

| 5.540 | Y267F | KCNQ2-Y237C | 0.996 | 0.644 | |

| 5.541 | I268V | KCNC2-F388S | 0.878 | 0.674 | |

| 5.548 | F275L | KCNQ2-L245P | 0.996 | 0.986 | |

| 5.552 | F279C | KCND3-V338E,KCNQ2-L249P | 0.999 | 0.788 | |

| 5.556 | A283T | KCNQ2-A253S/T | 0.996 | 0.504 | |

| 5.557 | E284G | KCNQ2-E254D | 1 | 0.972 | |

| 5.613 | S298R | KCNQ2-T263A/I | 0.997 | 0.977 | |

| 5.837 | A300G | KCNQ2-A265P/T/V | 0.986 | 0.747 | |

| 5.843 | G306E | KCNQ2-G271D/R/S/V, KCNQ3-G310D/V |

0.999 | 0.999 | |

| 5.844 | V307M | KCNB1-T372N/I | 0.991 | 0.79 | |

| 5.844 | V307L | KCNB1-T372N/I | 0.99 | 0.895 | |

| 5.844 | V307E | KCNB1-T372M/I | 0.993 | 0.989 | |

| 5.849 | T312S | KCNA2-T374A, KCNC2-T437A, KCNQ2-T277N/P/S |

0.995 | 0.966 | |

| 5.850 | I313F | KCNQ2-I278F/M/T, KCNQ3-I317M/T |

0.993 | 0.991 | |

| 5.855 | K318N | KCNQ2-K283E | 0.958 | 0.93 | |

| 5.856 | V319M | KCNQ2-Y284C/D | 0.995 | 0.616 | |

| 6.543 | A329V | KCND3-G384S, KCNQ2-A294G/S | 0.999 | 0.979 | |

| 6.543 | A329T | KCND3-G384S,KCNQ2-A294G/S | 0.987 | 0.935 | |

| 6.544 | S330Y | KCND3-S385P | 0.998 | 0.993 | |

| 6.545 | C331Y | KCNQ2-T296P | 0.998 | 0.976 | |

| 6.549 | F335C | KCNA1-A395S | 0.997 | 0.856 | |

| 6.551 | I337M | KCNA2-V399M | 0.962 | 0.775 | |

| 6.553 | F339V | KCNQ2-F304C,KCNQ2-F304S | 0.999 | 0.972 | |

| 6.555 | A341T | KCNA1-A401V, KCNB1-A406V, KCNQ2-A306P/T/V/E |

0.996 | 0.976 | |

| 6.563 | S349A | KCNB1-N414D | 0.995 | 0.92 | |

| 6.563 | S349L | KCNB1-N414D | 0.999 | 0.995 | |

| 6.566 | A352P | KCNB1-S417P,KCNQ2-A317T, KCNQ3-A356T |

0.999 | 0.997 | |

| 6.566 | A352D | KCNB1-S417P,KCNQ2-A317T, KCNQ3-A356T |

0.998 | 1 | |

| 6.569 | K354R | KCNQ2-K319E | 0.992 | 0.768 | |

| 6.571 | Q357R | KCNA1-R417X,KCNB1-E422A | 0.996 | 0.984 | |

| 6.571 | Q357E | KCNA1-R417X,KCNB1-E422A | 0.939 | 0.566 | |

| 6.574 | R360T | KCNQ2-R325G,KCNQ3-R364C/H | 0.999 | 0.999 | |

| 6.574 | R360K | KCNQ2-R325G,KCNQ3-R364C/H | 0.992 | 0.976 | |

| 7.013 | L374V | KCNQ2-L339Q,KCNQ2-L339R | 0.995 | 0.85 | |

| 7.030 | T391P | KCNQ2-T359K | 0.998 | 0.898 | |

| 7.165 | K526E | KCNQ2-K552N | 0.932 | 0.967 | |

| 7.165 | K526Q | KCNQ2-K552N | 0.838 | 0.717 | |

| 7.165 | K526N | KCNQ2-K552N | 0.984 | 0.995 | |

| 7.180 | V541I | KCNQ2-V567D | 0.903 | 0.814 | |

| 7.187 | G548D | KCNQ2-G574D/S | 0.999 | 0.999 | |

| 7.194 | R555L | KCNQ2-R581G | 0.998 | 0.994 | |

| 7.196 | K557R | KCNQ2-K583N | 0.982 | 0.63 | |

| 7.222 | R583S | KCNQ2-K606X | 0.885 | 0.902 | |

| 7.222 | R583G | KCNQ2-K606X | 0.79 | 0.606 | |

| 7.230 | R591P | KCNQ2-R622P | 0.997 | 0.997 |

| VUS → LP | P/LP | State b | VUS → LP | P/LP | State | ||||

| V133/1.550A | R231/4.550L | ↓ | L262/5.535V | P343/6.557A | ↓ | ||||

| Q234/4.553P | ↑ | o | P343/6.557A/S | ↑ | |||||

| C136/1.553F | S225/4.544L/W | ↓ | T264/5.537S | L233/4.552M | ↓ | ||||

| L156/2.536P | ↑ | o | L251/5.524Q/P | ↑ | |||||

| Q234/4.553P | ↑ | G269/5.542R/S/V/D | ↑ | ||||||

| L137/1.554P | S225/4.544L/W | ↓ | Y267/5.540F | G229/4.548D | ↓ | ||||

| G229/4.548D | ↓ | L233/4.552M | ↓ | ||||||

| Q234/4.553P | ↑ | E284/5.557G | T322/5.859P/A/R | ↓ | |||||

| I235/4.554N | ↑ | P320/5.857S | ↓ | ||||||

| I274/5.547D | ↑ | G325/6.539W | |||||||

| R231/4.550S/C/L/H | o | G306/5.843E | L273/5.546I/V/P/R/F | ↓ | |||||

| Q234/4.553P | o | V307/5.844M/L/E | S330/\6.544Y | ↓ | |||||

| I235/4.554L/N | o | T312/5.849S | T312/5.849I/S | ↓ | |||||

| S140/1.557R | S225/4.544L/W | ↓ | I313/5.850F | G314/5.851R/D/S | ↓ | ||||

| L156/2.536P | ↑ | T312/5.849S/I | ↓ | ||||||

| R231/4.550S/C/L/H | ↑ | o | T309/5.846I | ↓ | |||||

| Q234/4.553P | ↑ | o | V319/5.856M | Y315/5.852S | ↓ | ||||

| L156/2.536P | o | W304/5.841R/L/S | ↓ | ||||||

| S143/1.560F | R231/4.550S/C/L/H | o | W304/5.841 G | ↓ | |||||

| V164/2.544A | S 209/3.557 P | o | Y315/5.852D | ↓ | |||||

| E170/2.550G | R231/4.550S/H/C/L | ↓ | I337/6.551M | F340/6.554L | ↓ | ||||

| D202/3.550V | Q234/4.553P | ↓ | F339/6.553V | L251/5.524Q | ↓ | ||||

| R231/4.550S/C/L/H | ↓ | L251/5.524P | ↓ | ||||||

| R234/4.562S/C/L/H/P | ↑ | A341/6.555T | A344/6.558E/V | ↓ | |||||

| R243/4.562S/C/L/H/P | o | S349/6.563A/L | G345/6.559R/V/E | ↓ | |||||

| Q260/A5.533H | L251/D5.524Q/P | ↓ | R360/6.574K/T | R539/7.178W/Q | ↓ | ||||

| L262/5.535V | P343/6.557A/S | o | K557/7.196R | R555/7.194S/C | ↓ | ||||

| VUS → LP | Contact | VUS → LP | Contact | ||

| V133/A1.550I/A | R228/A4.547W | VUS→ LP | K318/A5.855N | D301/A5.838Y | VUS |

| G229/A4.548S/V | VUS | S349/A6.563A/L | S349/B,D6.563A/L | VUS→ LP | |

| Y267/B5.540F | VUS→ LP | A352/B,D6.566P/D | VUS→ LP | ||

| C136/A1.553F | R228/A4.547W | VUS→ LP | A352/A6.566P/D | L353/B6.567P | VUS |

| L137/A1.554P | G229/A4.548S/V | VUS | S349/B6.563A/L | VUS→ LP | |

| R228/A4.547W | VUS→ LP | G350/B6.564R | VUS | ||

| D202/A3.550V | Q234/A4.553L/R | VUS→ LP | R360/A6.574K/T | P535/A7.174T | VUS |

| S253/A5.526A | K354/A6.568R | VUS→ LP | T391/A7.030P | R518/A7.157Q/P | VUS |

| Y267/A5.540F | G229/D4.548S/V | VUS | V541/A7.180I | V541/B,D7.180I | VUS→ LP |

| E284/A5.557G | V324/6.538L/I/F | VUS | Y545/B7.184F | VUS | |

| A300/A5.837S/G | K326/B6.540E | VUS | G548/A7.187D | Y545/B7.184F | VUS |

| T312/A5.849S | I313/5.850F | VUS→ LP | |||

| I337/A6.551M | VUS→ LP | ||||

| VUS → LP | Contact c | VUS → LP | Contact | ||

| V164/A2.544A | S209/A3.557P | NP | I313/A5.850F | G314/B5.851C/A | NP |

| A223/A4.542T | Y278/B5.551H | NP | T309/B5.846S/R | NP | |

| Q260/A5.533H | L236/D4.555R/P | CIP | V308/B5.845D | NP | |

| T264/A5.537S | L236/D4.555R/P | CIP | K318/A5.855N | D301/A5.838V | CIP |

| L233/D4.552P | CIP | I337/A6.551M | T311/D5.848A | NP | |

| Y267/A5.540F | L233/4.552P | CIP | T311/D5.848I | CIP | |

| F275/A5.548L | A226/D4.545V | CIP | A341/A6.555T | A344/D6.558T/G | CIP |

| E284/A5.557G | T322/5.859K | CIP | S349/A6.563A/L | S349/B,D6.563P | CIP |

| F296/5.611S | CIP | A352/A6.566P/D | S349/B6.563P | CIP | |

| T312/A5.849S | I337/A6.551F | CIP | G350/B6.564V | CIP | |

| T391/A7.030P | R518/A7.157G | CIP | |||

| VUS → LP | Contact c | |

| C136/A1.553F | M159/2539L | VUS |

| S140/A1.557R | Q260/A5.533H | VUS → LP |

| V164/A2.544A | M210/3558T/I | VUS |

| E170/A2.550G | H240/4.559Q | VUS → LP |

| V129/1546I/G/A | VUS | |

| D202/A3.550V | H240/4.559Q | VUS → LP |

| L239/4.558V | Y267/A5.540F | VUS → LP |

| F275/A5.548S/L | VUS → LP | |

| H240/4.559Q/R | E170/A2.550G | VUS → LP |

| D202/A3.550H | VUS → LP | |

| V241/4.560I | Y267/5.540F | VUS |

| Y267/A5.540F | V241/4.560I | VUS → LP |

| L239/4.558V | VUS → LP | |

| F275/A5.548L | L239/4.558V | VUS → LP |

| VUS | Cs | Functional Study a | ClinPred | Paralog |

| S28L | 0.6 | Smaller current | 0.818 | KCNE5-VUS:D44H |

| R32C | 0.8 | faster activation | 0.622 | KCNE3-VUS:R47G,KCNE3-VUS:R47Q,KCNE3-VUS:R47W |

| P35S | 0.4 | faster activation | 0.957 | KCNE2-VUS:V41A |

| L48I | 0.9 | ~ current | 0.963 | KCNE2-Disease:M54T,KCNE2-VUS:M54V |

| L48F | 0.9 | faster activation | 0.808 | KCNE2-Disease:M54T,KCNE2-VUS:M54V |

| L48P | 0.9 | 0.999 | KCNE2-Disease:M54T,KCNE2-VUS:M54V | |

| M49T | 0.7 | 0.958 | KCNE5-VUS:L65F | |

| F53L | 0.8 | ~ current | 0.756 | KCNE2-VUS:M59I,KCNE5-VUS:F69V |

| F53C | 0.8 | Small current | 0.996 | KCNE2-VUS:M59I,KCNE5-VUS:F69V |

| G55R | 0.8 | 0.994 | KCNE2-VUS:S61P | |

| T58P | 0.6 | Slower activation | 0.982 | NA-Disease:T58PP,KCNE3-VUS:V72G |

| T58A | 0.6 | 0.987 | NA-Disease:T58PP,KCNE3-VUS:V72G | |

| L59P | 0.7 | LoF | 0.978 | KCNE2-VUS:V65L,KCNE2-VUS:V65M,KCNE5-VUS:G75R |

| G60D | 0.8 | Small current | 0.994 | KCNE2-VUS:A66V,KCNE3-VUS:S74R,KCNE5-VUS:G76D |

| G60V | 0.8 | 0.995 | KCNE2-VUS:A66V,KCNE3-VUS:S74R,KCNE5-VUS:G76D | |

| I61F | 1 | 0.983 | KCNE2-VUS:I67M | |

| I66L | 0.7 | 0.905 | KCNE3-VUS:T80I | |

| R67G | 0.9 | Small current | 0.996 | KCNE3-VUS:R81C |

| R67S | 0.9 | Small current | 0.987 | KCNE3-VUS:R81C |

| R67L | 0.9 | Small current | 0.99 | KCNE3-VUS:R81C |

| R67H | 0.9 | Small current | 0.873 | KCNE3-VUS:R81C |

| K69E | 0.9 | 0.953 | KCNE3-VUS:R83C,KCNE3-VUS:R83P,KCNE5-VUS:R85H | |

| K70Q | 0.9 | 0.977 | KCNE3-VUS:K84E,KCNE5-VUS:K86E | |

| K70M | 0.9 | Small current | 0.994 | KCNE3-VUS:K84E,KCNE5-VUS:K86E |

| K70E | 0.9 | 0.983 | KCNE3-VUS:K84E,KCNE5-VUS:K86E | |

| L71V | 0.4 | 0.956 | KCNE2-Disease:R77W,KCNE3-VUS:V85A | |

| E72K | 0.4 | 0.984 | KCNE5-VUS:V88D,KCNE5-VUS:V88I | |

| H73R | 0.6 | 0.931 | KCNE2-VUS:H79R,KCNE5-VUS:E89K | |

| S74W | 0.4 | Small current | 0.998 | KCNE2-VUS:S80P,KCNE3-VUS:R88C,KCNE3-VUS:R88H |

| S74P | 0.4 | Smaller current | 0.629 | KCNE2-VUS:S80P,KCNE3-VUS:R88C,KCNE3-VUS:R88H |

| Y81C | 0.7 | Smaller current | 0.998 | KCNE2-VUS:Y87C |

| I82M | 0.4 | Smaller current | 0.885 | KCNE3-VUS:I96S |

| I82V | 0.4 | Smaller current | 0.978 | KCNE3-VUS:I96S |

| I82F | 0.4 | 0.993 | KCNE3-VUS:I96S |

|

KCNE1 Variant |

Classifi- cation |

Current | Contact with | |||

| Change a | KCNE1 | Kv7.1 | ||||

| M1L/I/R/T/K/V | P/VUS | R67G/S/L/H | VUS | F256/5.529 | ||

| L48I/F/P | VUS→ LP | ~ | I138/1.555 L142/1.559 |

|||

| M49T/I | VUS→ LP | L13R/P/V/M | NP | C331/6.545Y T327/6.541D |

VUS → LP VUS |

|

| G52R/ V/E/A | P/NP | R ↓ | L134/1.551P | CIP | ||

| F53L/C | VUS→ LP | C ↓ L ~ |

L13R/P/V/M V95I |

NP VUS |

F335/6.549C F270/5.543 |

VUS → LP |

| G55R | VUS→ LP | L134/1.551P F130/1.547 |

CIP | |||

| T58P/A | VUS→ LP | P ↓ | F130/1.547 Y267/5.540F V241/4.560I |

VUS → LP VUS → LP |

||

| L59P | VUS→ LP | F127/1.544L F123/1.540 |

NP | |||

| G60D/V | VUS→ LP | D ↓ | I263/5.536V | VUS | ||

| I61F | VUS→ LP | Y267/5.540F D242/4.561Y/N/E Q260/5.533H I263/5.536V T247/5.520 |

VUS → LP P/LP VUS → LP VUS |

|||

| I66L | VUS→ LP | F123/1.540 P117/1.534T/S/L |

LP |

|||

| R67G/S/L/H | VUS→ LP | All ↓ | M1L/I/R/T/K/V | P/NP | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).