Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

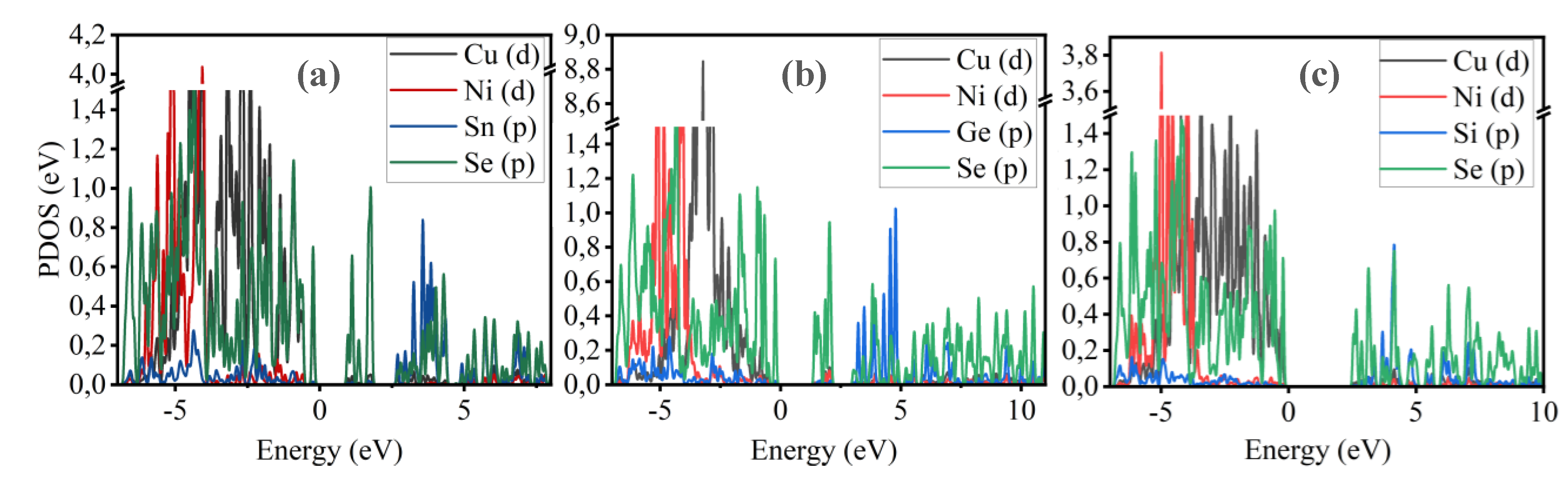

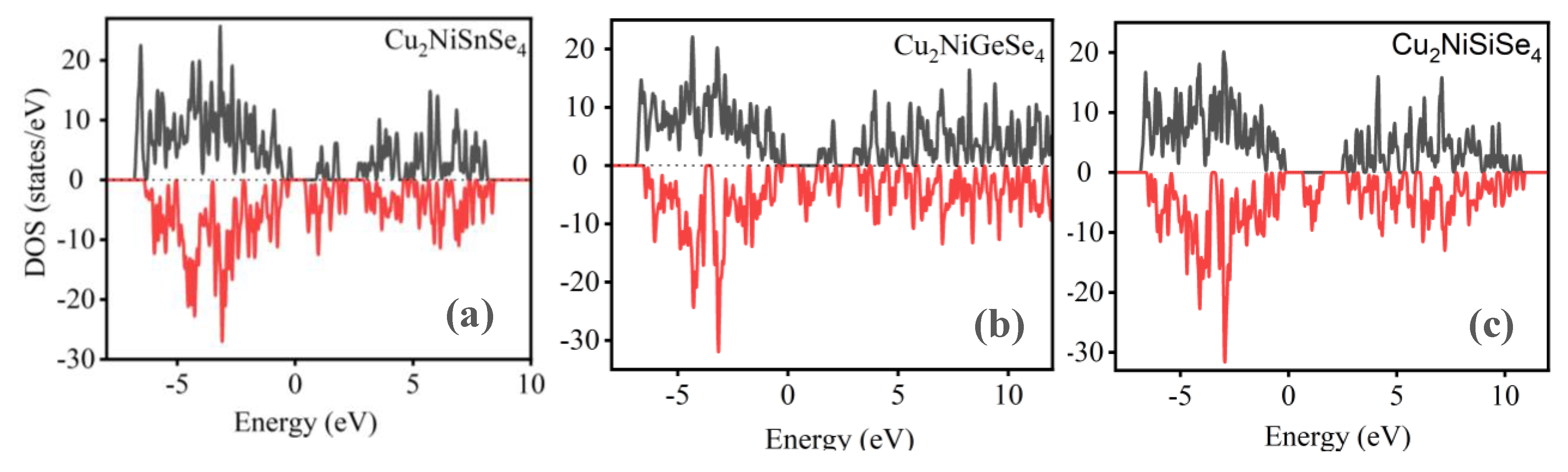

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitzi, D.B.; et al. The path to high-efficiency kesterite solar cells. Nature Photonics 2011, 5, 645–653. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Hohl-Ebinger, J.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Hao, X. Solar cell efficiency tables (version 57). Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 2021, 29, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scragg, J.J.; Choubrac, L.; Lafond, A.; Ericson, T.; Platzer-Björkman, C. A low-temperature order-disorder transition in Cu₂ZnSnS₄ thin films. Applied Physics Letters 2014, 104, 041901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Oonuki, M.; Moritake, N.; Uchiki, H. Cu₂ZnSnS₄ thin film solar cells prepared by non-vacuum processing. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2009, 93, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; et al. Structural and optical properties of Cu₂NiSnS₄ thin films synthesized by spray pyrolysis. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 180, 239-245.

- Heyd, J.; Scuseria, G.E.; Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2003, 118, 8207–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Chen, S.; Su, Z.; Wang, Z.; Luo, P.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, G. Heat treatment in an oxygen-rich environment to suppress deep-level traps in Cu₂ZnSnS₄ solar cell with 11.51% certified efficiency. Nature Energy 2025, 1-11.

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Zheng, Z.; Su, Z.; Ma, H.; Liang, G. Energy band alignment and defect synergistic regulation enable air-solution-processed kesterite solar cells with the lowest VOC deficit. Advanced Materials 2025, 37, 2409327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.; Jian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, G. An effective precursor-solutioned strategy for developing Cu₂ZnSn(S,Se)₄ thin film toward high efficiency solar cell. Advanced Energy Materials 2025, 15, 2403950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Liang, G.; Fan, P.; Luo, J.; Zheng, Z.; Xie, Z.; Liu, F. Device postannealing enabling over 12% efficient solution-processed Cu₂ZnSnS₄ solar cells with Cd²⁺ substitution. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 2000121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Zheng, Z.; Fan, P.; Li, Y.; Liang, G. Unveiling the selenization reaction mechanisms in ambient air-processed highly efficient kesterite solar cells. Advanced Energy Materials 2023, 13, 2300521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; He, C.; Wu, T.; Chen, S.; Su, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liang, G. Sputtering deposited and energy band matched ZnSnN₂ buffer layers for highly efficient Cd-free Cu₂ZnSnS₄ solar cells. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34, 2402762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.X.; Li, C.H.; Zhao, J.; Fu, Y.; Yu, Z.X.; Zheng, Z.H.; Chen, S. Self-powered broadband kesterite photodetector with ultrahigh specific detectivity for weak light applications. SusMat 2023, 3, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Li, Z.; Ishaq, M.; Zheng, Z.; Su, Z.; Ma, H.; Chen, S. Charge separation enhancement enables record photocurrent density in Cu₂ZnSn(S,Se)₄ photocathodes for efficient solar hydrogen production. Advanced Energy Materials 2023, 13, 2300215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Liang, G. Potassium doping for grain boundary passivation and defect suppression enables highly-efficient kesterite solar cells. Chinese Chemical Letters 2024, 35, 109468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, L.; Huang, T.; Tu, B.; Li, H.; He, Q.; Guo, F. Dual interfacial design enables efficient and stable semitransparent wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells with scalable-coated silver nanowire contact for tandem applications. SusMat 2025, 5, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Su, Z.; Abbas, M.; Chen, C.; Liang, G. Tailoring a back-contact barrier for a self-powered broadband kesterite photodetector with ultralow dark current enabling ultra-weak-light detection. Carbon Energy 2025, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, C.; Xin, H.; Ding, L. Solution-processed CuIn(S,Se)₂ solar cells on transparent electrode offering 9.4% efficiency. Journal of Semiconductors 2023, 44, 80501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendahah, A.; Bensaid, D.; Yhaia, A.; Khadidja, M.; Noureddine, M.; Bendouma, D.; Al-Douri, Y. First-principles calculations to investigate structural, electronic, piezoelectric and optical properties of Sc-doped GaN. *Emergent Materials 2024, 1-9.

- Marzougui, B.; Smida, Y.B.; Ferhi, M.; Ferjani, H.; Onwudiwe, D.; Hamzaoui, A.H.; Al Douri, Y. Photoluminescence properties of Pr-doped LaAsO₄: An experimental and theoretical study employing density functional theory. Ceramics International 2024, 50, 26435–26445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Essa, S.; Essaoud, S.S.; Bouhemadou, A.; Ketfi, M.E.; Maabed, S.; Djilani, F.; Al-Douri, Y. An ab initio analysis of the electronic, optical, and thermoelectric characteristics of the Zintl phase CsGaSb₂. Physica Scripta 2024, 99, 095996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smida, Y.B.; Marzougui, B.; Driss, M.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Al-Douri, Y. Exploring the optoelectronic potential of M₂SnX₃F₂ (M= Sr, Ba; X= S, Se) compounds through first-principles analysis of structural, electronic, and optical properties. Chemistry Africa 2024, 7, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelakader, A.; Ahmed, B.; Noureddine, M.; Mokhtar, B.; Abdelhalim, Z.; Omar, M.; Al-Douri, Y. Theoretical investigations of electronic, thermodynamic and thermoelectric properties of filled skutterudites ThFe₄P₁₂ and CeFe₄P₁₂ using DFT calculations. Solid State Communications 2024, 380, 115435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, D.; Abdelmadjid, B.; Saber, S.E.; Bahri, D.; Zerarga, F.; Amari, R.; Al-Douri, Y. A first-principles investigation on the structural, electronic and optical characteristics of tetragonal compounds XAgO (X= Li, Na, K, Rb). Computational Condensed Matter 2024, 38, e00876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaf, H.; Radjai, M.; Allali, D.; Bouhemadou, A.; Essaoud, S.S.; Bin-Omran, S.; Al-Douri, Y. Ab initio predictions of pressure-dependent structural, elastic, and thermodynamic properties of CaLiX₃ (X= Cl, Br, and I) halide perovskites. Computational Condensed Matter 2023, 37, e00850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferjani, H.; Smida, Y.B.; Al-Douri, Y. First-principles calculations to investigate the effect of van der Waals interactions on the crystal and electronic structures of tin-based 0D hybrid perovskites. Inorganics 2022, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samia, R.; Yahia, A.; Ahmed, B.; Mokhtar, B.; Noureddine, M.; Mohamed, L.; Al-Douri, Y. Electronic, elastic and piezoelectric properties calculations of perovskites materials type BiXO₃ (X= Al, Sc): DFT and DFPT investigations. Chemical Physics 2023, 573, 111998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaid, F.O.; Boufadi, F.Z.; Tayebi, N.; Ameri, M.; Mentefa, A.; Bellagoun, L.; Al-Douri, Y. Theoretical investigation of structural, electronic, elastic, magnetic, thermodynamic, and thermoelectric properties of Ru₂MnNb Heusler alloy: FP-LMTO method. Emergent Materials 2022, 5, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drici, L. First-principles calculations of structural, elastic, electronic, and optical properties of CaYP (Y= Cu, Ag) Heusler alloys. Emergent Materials 2021, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saim, A.; Belkharroubi, F.; Boufadi, F.Z.; Ameri, I.; Blaha, L.F.; Tebboune, A.; Abd El-Rehim, A.F. Investigation of the structural, elastic, electronic, and optical properties of half-heusler CaMgZ (Z= C, Si, Ge, Sn, Pb) compounds. Journal of Electronic Materials 2022, 51, 4014–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samia, L.; Belkharroubi, F.; Ibrahim, A.; Lamia, B.F.; Saim, A.; Maizia, A.; Al-Douri, Y. Investigation of structural, elastic, electronic, and magnetic proprieties for X₂LuSb (X= Mn and Ir) full-Heusler alloys. Emergent Materials 2022, 5, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerarga, F.; Allali, D.; Bouhemadou, A.; Khenata, R.; Deghfel, B.; Essaoud, S.S.; Naqib, S.H. Ab initio study of the pressure dependence of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of GeB₂O₄ (B= Mg, Zn and Cd) spinel crystals. Computational Condensed Matter 2022, 32, e00705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamara, A.; Moulay, N.; Azzaz, Y.; Ameri, M.; Rabah, M.; Al-Douri, Y.; Moumen, C. Elastic, electronic, thermal and magnetic investigations of PrX₂ (X= Fe, Ru) superconductors materials. Materials Today Communications 2023, 35, 105545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawarin, J.I.; Abu-Yamin, A.A.; Abu-Saleh, A.A.A.A.; Saraireh, I.A.; Almatarneh, M.H.; Hasan, M.; Al-Douri, Y. Synthesis, characterization, and DFT calculations of a new sulfamethoxazole schiff base and its metal complexes. Materials 2023, 16, 5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, D.; Amari, R.; Bouhemadou, A.; Boukhari, A.; Deghfel, B.; Essaoud, S.S.; Al-Douri, Y. Ab initio investigation of structural, elastic, and thermodynamic characteristics of tetragonal XAgO compounds (X= Li, Na, K, Rb). Physica Scripta 2023, 98, 115905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; et al. Cu₂NiGeSe₄: A new kesterite material for photovoltaic applications. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2021, 230, 111234. [Google Scholar]

- Berri, S. Search for New Half-Metallic Ferromagnets in Quaternary Diamond-Like Compounds I–II 2–III–VI 4 and I 2–II–IV–VI 4 (I= Cu; II= Mn, Fe, Co; III= In; IV= Ge, Sn; VI= S, Se, Te). Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism, 31 2018, 1941-1947.

- Berri, S.; Bouarissa, N.; Oumertem, M.; Chami, S. First-principles investigation of structural, electronic, optical and thermodynamic properties of KAg2SbS4. Computational Condensed Matter 2019, 19, e00365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berri, S.; Amari, R.; Bouarissa, N.; Miloud, I. Study on quaternary diamond-like Li2CaGeO4 properties for optoelectronic applications. Computational Condensed Matter 2022, 30, e00646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Physical review B 1996, 54, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Physical review B 1994, 50, 17953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ruzsinszky, A.; Perdew, J.P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Physical review letters 2015, 115, 036402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyd, J.; Scuseria, G.E.; Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. The Journal of chemical physics 2003, 118, 8207–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Campo, J. M., Gázquez, J. L., Trickey, S. B., & Vela, A. (2012). Non-empirical improvement of PBE and its hybrid PBE0 for general description of molecular properties. The Journal of chemical physics, 136(10).

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. Applied Crystallography 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, N. (2017). Engineered transition metal chalcogenides for photovoltaic, thermoelectric, and magnetic applications. PhD diss.

- Tajima, S.; Ueno, T.; Matsubara, K.; Yoshida, T.; Shibata, H. Structural and optoelectronic properties of Cu2NiSn(S,Se)4 kesterite films for photovoltaic applications. Sol, Energy Mater, Sol, Cells 2018, 186, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, C. Electronic and optical properties of Cu-based quaternary compounds for thin film solar cells. J, Appl, Phys 2010, 107, 053710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scragg, J.J.; Larsen, J.K.; Kumar, M.; Persson, C.; Sendler, J.; Siebentritt, S.; Platzer Björkman, C. Cu–Zn disorder and band gap fluctuations in Cu2ZnSn(S, Se)4: Theoretical and experimental investigations. physica status solidi (b) 2016, 253, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Shahi, C.; Bhetwal, P.; Perdew, J.P.; Paesani, F. How good is the density-corrected SCAN functional for neutral and ionic aqueous systems, and what is so right about the Hartree–Fock density? . Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2022, 18, 4745–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsbury, R.; Gupta, A.S.; Bartel, C.J.; Munro, J.M.; Dwaraknath, S.; Horton, M.; Persson, K.A. Performance comparison of r2 SCAN and SCAN metaGGA density functionals for solid materials via an automated, high-throughput computational workflow. Physical Review Materials 2022, 6, 013801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinuma, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Kumagai, Y.; Tanaka, I.; Oba, F. Comparison of approximations in density functional theory calculations: Energetics and structure of binary oxides. Physical Review B 2017, 96, 094102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, C.; Sun, J.; Perdew, J.P. Accurate critical pressures for structural phase transitions of group IV, III-V, and II-VI compounds from the SCAN density functional. Physical Review B 2018, 97, 094111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekholm, M.; Gambino, D.; Jönsson, H.J. M.; Tasnádi, F.; Alling, B.; Abrikosov, I.A. Assessing the SCAN functional for itinerant electron ferromagnets. Physical Review B 2018, 98, 094413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Tran, F.; Blaha, P. Merits and limits of the modified Becke-Johnson exchange potential. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2011, 83, 195134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.S.; Lima, A.F. Combining mBJ exchange potential and bootstrap kernel of TDDFT to compute optical spectra of solids. Computational Condensed Matter 2024, 39, e00909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, R.K. G.; Aliabad, H.R.; Baghani, H.R.; Özdemir, E.G.; Arzefooni, A.A.; Sadati, S.Z. Optoelectronic, thermoelectric, and EFG of atomic nuclei of trityl-functionalized fullerene C60 using GGA and mBJ approximations. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2025, 704, 417053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 이재호. (2016). Characteristics of the higher-k Hf-Zr-O dielectric materials on Si Ge substrates and their application in 3-dimensional Tri-Gate FET devices (Doctoral dissertation, 서울대학교 대학원).

- Ahmed, I.; Prakash, K.; Mobin, S.M. (2025). Lead-free perovskites for solar cells applications: recent progress, ongoing challenges, and strategic approaches. Chemical Communications.

- Aouiche, Abdelaziz. "Semiconductor Physics." (2024).

- Chibani, M.; Benamara, S.; Zitoune, H.; Lasmi, M.; Benchalal, L.; Lamiri, L.; Samah, M. Electronic and Magnetic Properties of Small Nickel Clusters Ni n (n≤ 15): First Priciple Study. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 2025, 125, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Biswas, A.; Thangavel, R.; Udayabhanu, G. Photo-electrochemical properties and electronic band structure of kesterite copper chalcogenide Cu 2–II–Sn–S 4 (II= Fe, Co, Ni) thin films. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 96025–96034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østrøm, I.; Favaro, M.; Seyfouri, M.; Burr, P. Hoex, B. Electrostatic and Electronic Effects on Doped Nickel Oxide Nanofilms for Water Oxidation. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2025, 147, 4, 3593–3606. [Google Scholar]

- Sofi, M.Y.; Khan, M.S.; Ali, J.; Khan, M.A. Unlocking the role of 3d electrons on ferromagnetism and spin-dependent transport properties in K2GeNiX6 (X= Br, I) for spintronics and thermoelectric applications. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2024, 192, 112022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrai, H.; Zaim, A.; Kerouad, M. Half-metallic ferromagnetic and optical properties of YScO3 (Y= Ni, Pd, and Pt) perovskite: A first principles study. Vacuum 2024, 226, 113341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinel Pérez, N.M.; Vera López, E.; Gómez Cuaspud, J.A.; Carda Castelló, J.B. A review of recent advances of kesterite thin films based on magnesium, iron and nickel for photovoltaic application: insights into synthesis, characterization and optoelectronic properties. Clean Energy 2024, 8, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, J.; Yin, K.; Wang, J.; Lou, L.; Li, D.; Meng, Q. 12. 84% efficiency flexible kesterite solar cells by heterojunction interface regulation. Advanced Energy Materials 2023, 13, 2301701. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, G.; Abdalla, H.; Kemerink, M. Impact of doping on the density of states and the mobility in organic semiconductors. Physical Review B 2016, 93, 235203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshak, A.H.; Van Vliet, C.M. Electrical current and carrier density in degenerate materials with nonuniform band structure. Proceedings of the IEEE 1984, 72, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayanan, S.; Pandiaraj, S.; Abeykoon, C.; Alzahrani, K.E.; Alodhayb, A.N.; Grace, A.N. Investigating the potential of perovskite-based redox electrolytes for dye sensitised solar cells: An in-depth analysis using mathematical and DFT techniques. Solar Energy 2025, 288, 113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.; Shahzaib, M.; Jan, S.T.; Khan, Z.; Ismail, M.; Khan, A.D. Optimizing band gap, electron affinity, carrier mobility for improved performance of formamidinium lead tri-iodide perovskite solar cells. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2024, 300, 117114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, M.; Yu, Z.G.; Wang, K.; Hu, B. Magnetic field effects on excited states, charge transport, and electrical polarization in organic semiconductors in spin and orbital regimes. Advances in Physics 2019, 68, 49–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volnianska, O.; Boguslawski, P. Magnetism of solids resulting from spin polarization of p orbitals. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2010, 22, 073202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansmann, J.; Baker, S.H.; Binns, C.; Blackman, J.A.; Bucher, J.P.; Dorantes-Dávila, J.; Xie, Y. Magnetic and structural properties of isolated and assembled clusters. Surface Science Reports 2005, 56(6-7), 189-275.

- ELAGGOUNE.; W (2024). Ab-initio study of the properties of the 3D SrS-based mono-doped and co-doped compounds. A comparative study of the 2D and 3D mono-doped compounds (Doctoral dissertation).

- Haas, C. Magnetic semiconductors. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Material Sciences 1970, 1;1(1), 47-98.

- Nematov, D. Bandgap tuning and analysis of the electronic structure of the Cu2NiXS4 (X= Sn, Ge, Si) system: mBJ accuracy with DFT expense. Chemistry of Inorganic Materials 2023, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematov, D.; Burhonzoda, A.; Khusenov, M.; Kholmurodov, K.; Doroshkevych, A.; Doroshkevych, N.; Ibrahim, M. Molecular dynamics simulations of the DNA radiation damage and conformation behavior on a zirconium dioxide surface. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 2019, 62, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematov, D. ; HojamberdievM. (2025). Machine Learning-Driven Materials Discovery: Unlocking Next-Generation Functional Materials-A minireview. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503. 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, M.; Abdullah, M.; Dai, S.; Iqbal, M.A.; Tang, W.; Sohail, M. T.; Zeng, Y.J. (2025). Magnetoresistance in 2D Magnetic Materials: From Fundamentals to Applications. Advanced Functional Materials, 2417282.

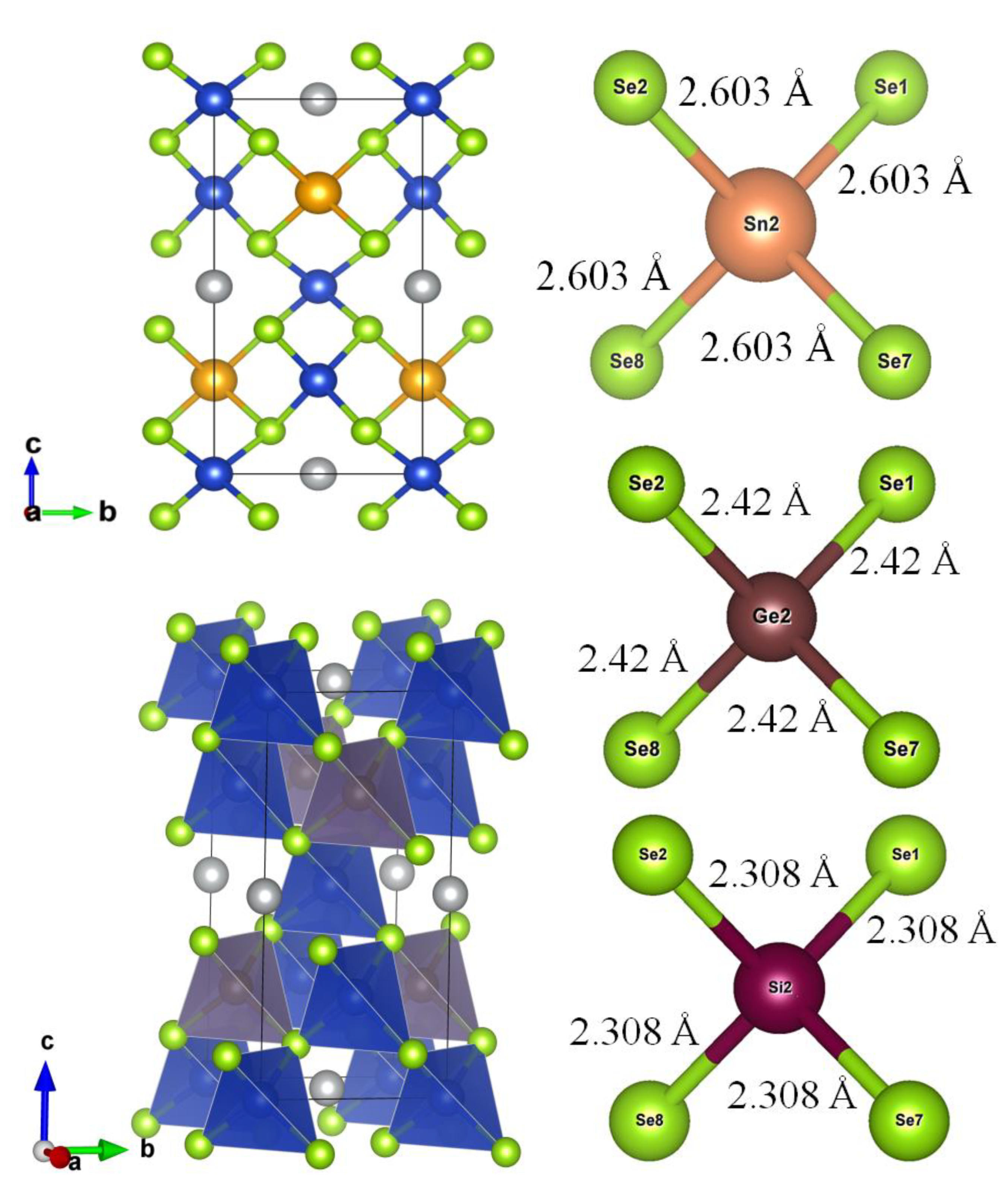

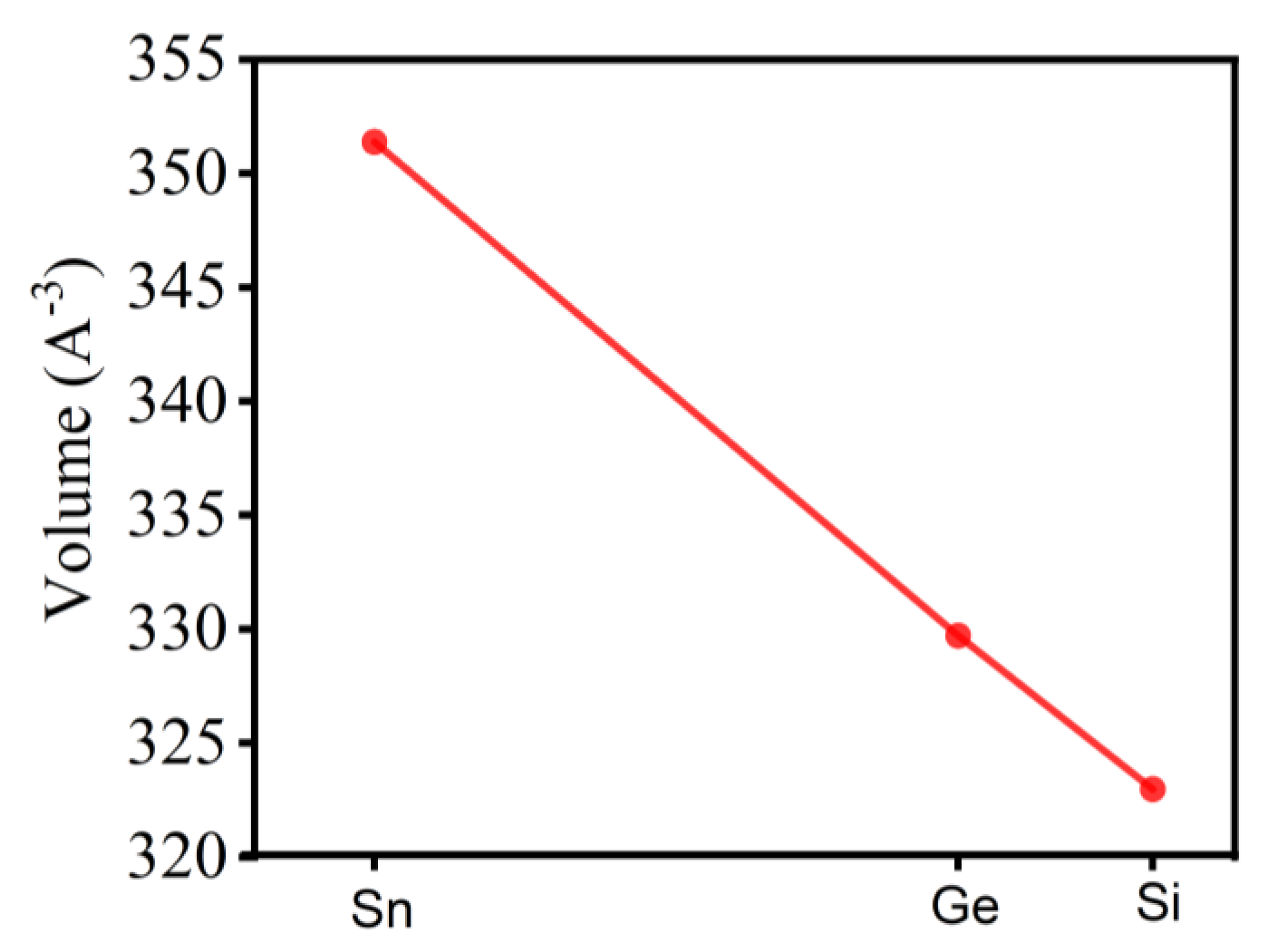

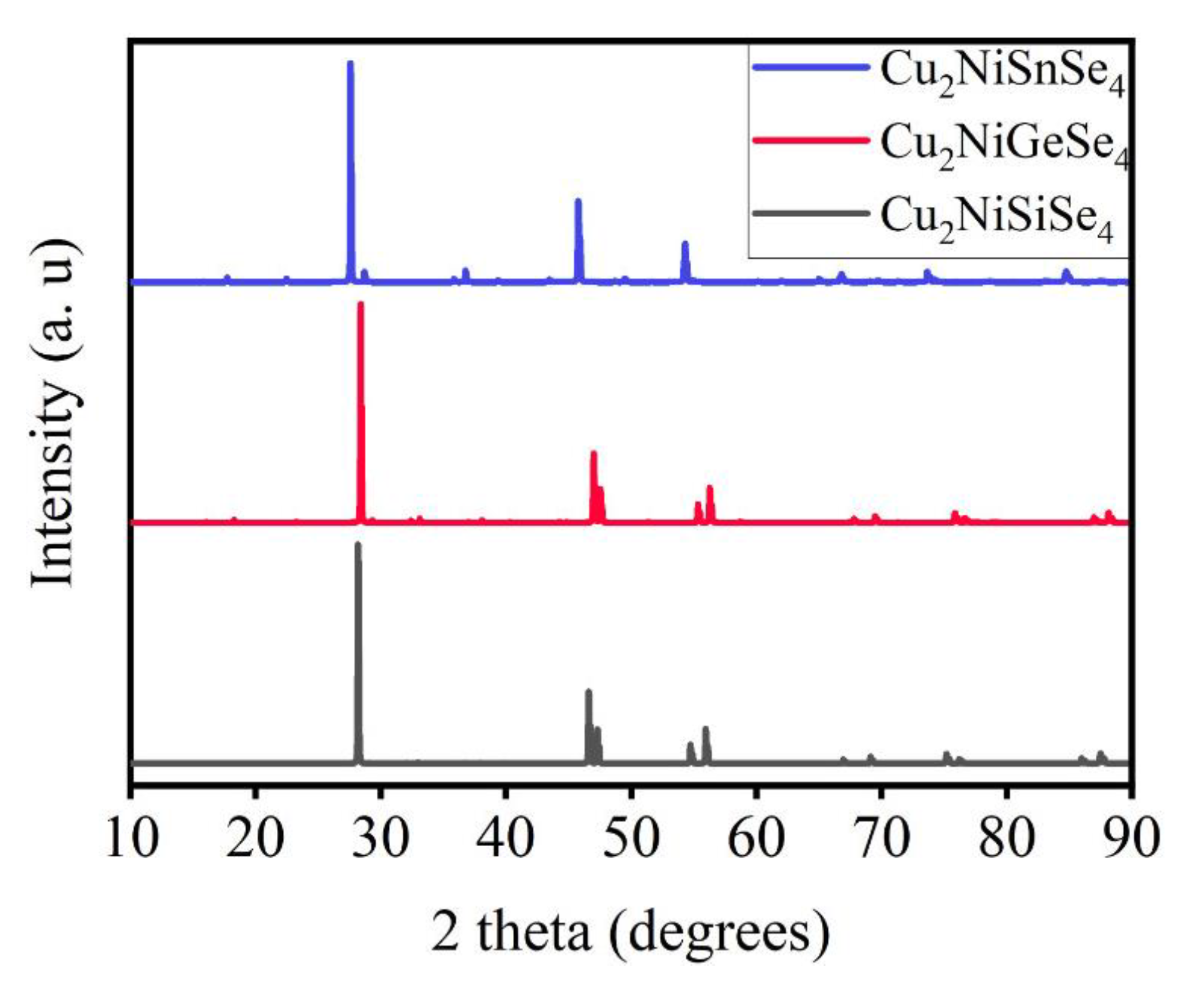

| SYSTEM | Lattice constants | PBE (GGA) | PBEsol | SCAN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2NiSiSe4 | a, b (Å) | 5.491 | 5.373 | 5.406 |

| c (Å) | 11.044 | 10.911 | 11.048 | |

| α=β=γ, o | 90 | 90 | 90 | |

| V (Å3) | 333.060 | 315.034 | 322.983 | |

| Cu2NiGeSe4 | a, b (Å) | 5.54646 | 5.423 | 5.432 |

| c (Å) | 11.171 | 11.035 | 11.174 | |

| α=β=γ, o | 90 | 90 | 90 | |

| V (Å3) | 343.684 | 324.570 | 329.716 | |

| Cu2NiSnSe4 | a, b (Å) | 5.669 | 5.567 | 5.597 |

| c (Å) | 11.319 | 11.088 | 11.216 | |

| α=β=γ, o | 90 | 90 | 90 | |

| V (Å3) | 363.868 | 343.676 | 351.372 |

| System | Total Energy (eV) | Formation Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| Cu2NiSnSe4 | -65.639 | -50.809 |

| Cu2NiGeSe4 | -66.628 | -51.638 |

| Cu2NiSiSe4 | -68.851 | -54.081 |

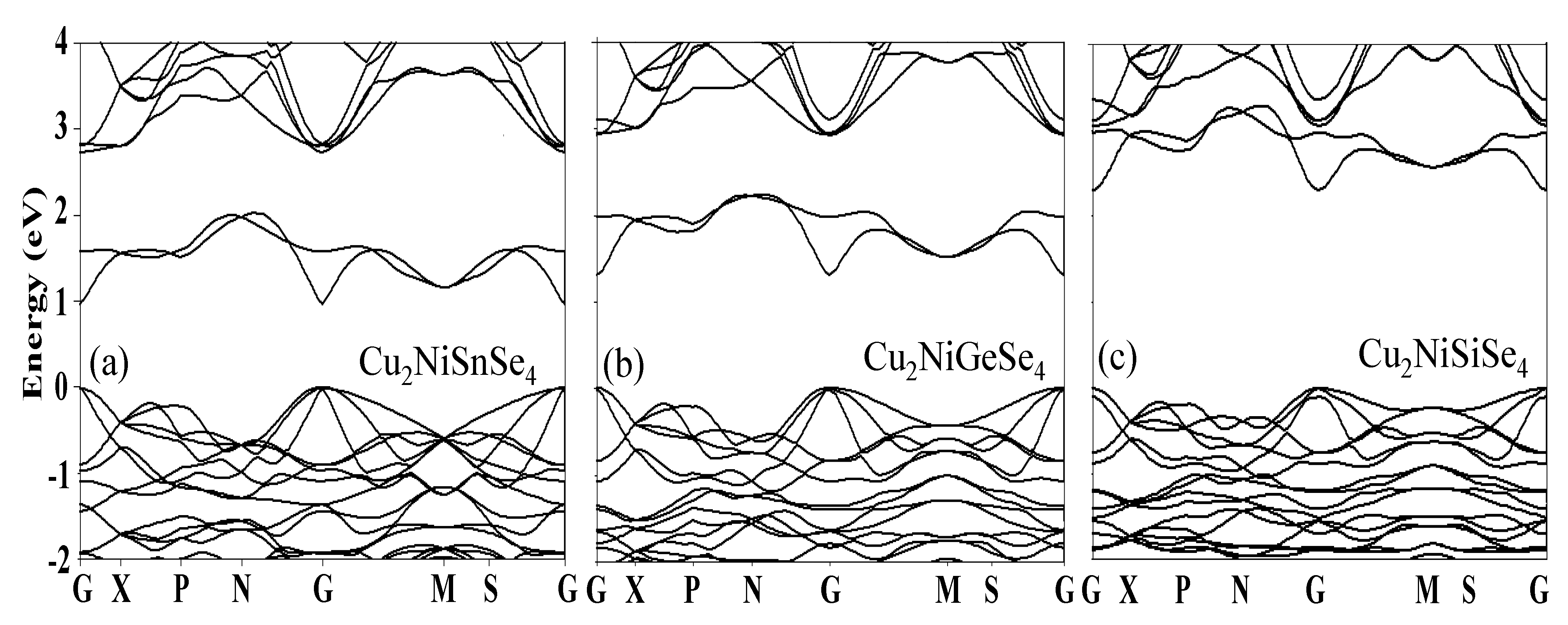

| SYSTEM | HSE06/GGA | HSE06/SCAN | HSE06/PBEsol | mBJ/GGA | mBJ/SCAN | mBJ/PBEsol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2NiSnSe4 | 0,638 | 0,792 | 0,66 | 0,22 | 0,341 | 0,231 |

| Cu2NiGeSe4 | 0,968 | 1,232 | 1,078 | 0,539 | 0,726 | 0,572 |

| Cu2NiSiSe4 | 2,101 | 2,354 | 2,167 | 1,617 | 1,826 | 1,628 |

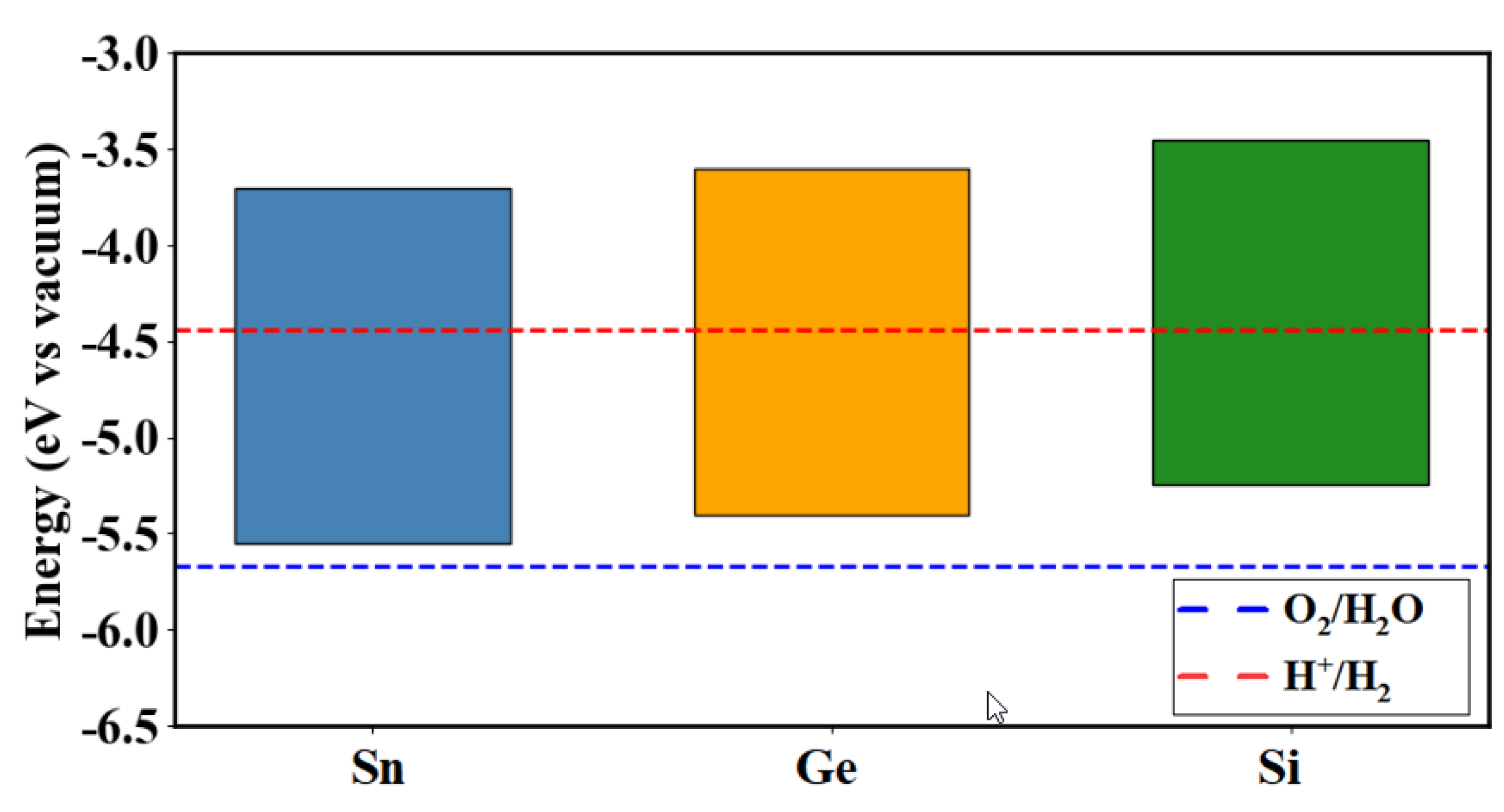

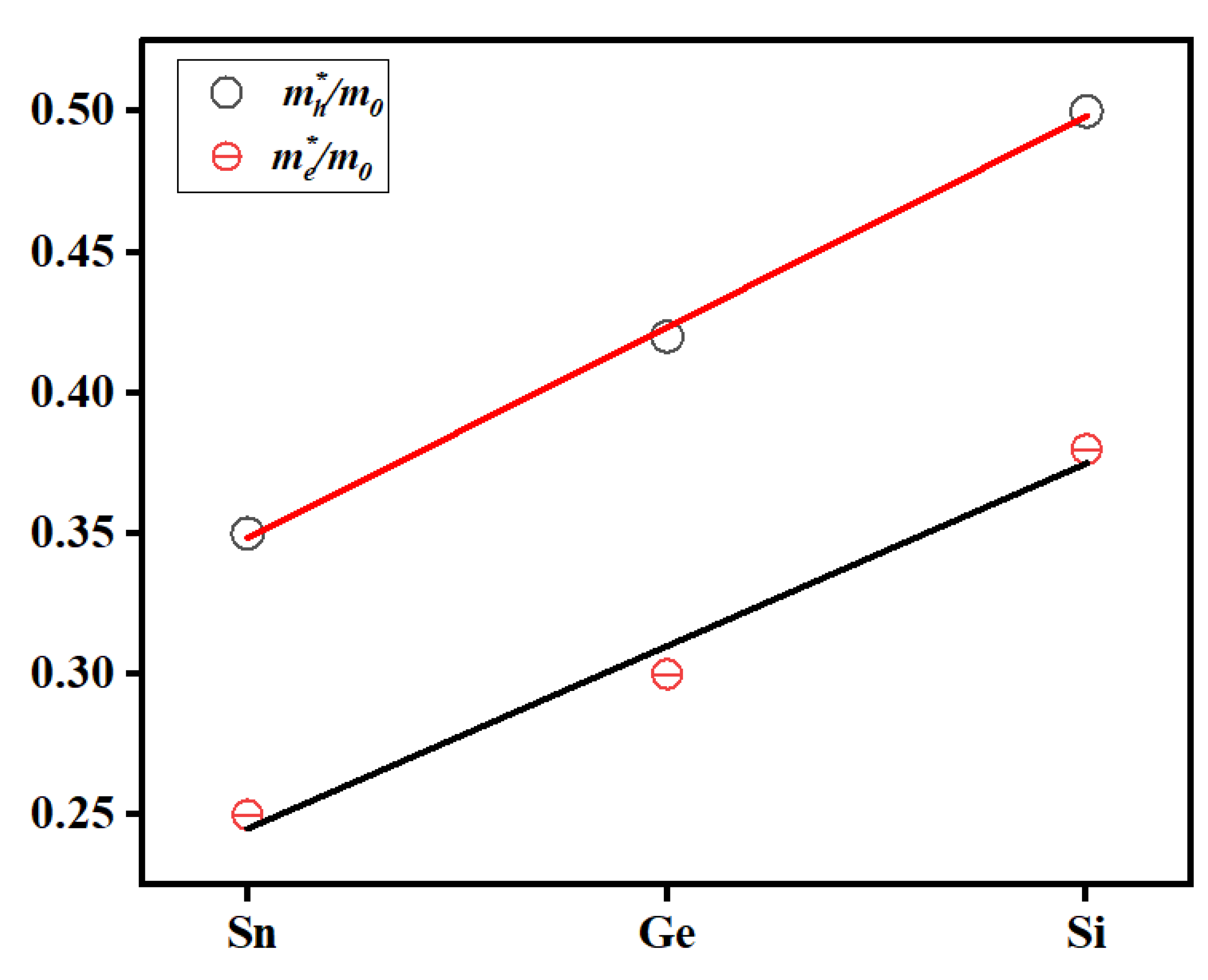

| SYSTEM | EF (eV) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2NiSnSe4 | 5.12 | 0.35 | 0.25 | |

| Cu2NiGeSe4 | 5.07 | 0.42 | 0.30 | |

| Cu2NiSiSe4 | 5.16 | 0.50 | 0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).