1. Introduction

Noise pollution is a critical concern in urban, transport, and industrial settings, often linked to serious health issues [

1,

2,

3]. While traditional noise control methods involving dense materials are effective, they are typically heavy, unsustainable, and less suited to attenuate low-frequency noise as compared to 3D printed metastructures [

4]. This has fueled interest in more sustainable and efficient noise control solutions [

5,

6]. Specifically, effective absorption of low-frequency sound is vital for mitigating noise in transport and industrial environments. Perforated metamaterials, with their engineered microstructures, have demonstrated superior absorption of low-frequency sounds [

4,

7]. This superior absorption results from specific microstructural features, including perforation size, spacing, and geometry that enable effective resonant energy dissipation through Helmholtz resonance mechanisms, viscous and thermal boundary-layer effects within perforations, and structural configurations tuned to target specific low-frequency ranges [

8]. These 3D printed metamaterials can be effectively integrated into smart orthotics to address low-frequency noise issues [

9]. Such devices are typically used intermittently and replaced periodically. Biodegradable PLA-based biocomposites provide a sustainable and functional alternative to synthetic polymers. Given the challenges of environmental pollution and CO₂ emissions, it is essential to minimize the adverse effects of non-biodegradable materials and promote sustainable alternatives. PLA-based composites represent one such option, offering mechanical properties comparable to traditional materials like polystyrene foam, polyurethane foam, fiberglass, mineral wool, and PVC. Although effective for soundproofing and insulation, these conventional materials contribute significantly to environmental degradation due to their non-biodegradable nature and polluting manufacturing processes, thus amplifying overall environmental impact [

10]. In conductive PLA, their conductive nature supports intrinsic EMI shielding—essential for protecting embedded electronics—while also aligning with end-of-life environmental objectives. This study compares the acoustic and multifunctional performance of these sustainable composites with conventional conductive TPU, which is valued for its flexibility and durability.

According to Karamanlioglu et al. [

11], PLA provides sustainability advantages through its renewable origin and reduced ecological footprint compared to conventional plastics that makes it a suitable alternative for use in smart orthotics (with use of coatings to have a reasonable structural integrity). However, its end-of-life management necessitates efficient recycling and composting systems.

Figure 1.

Noise level with daily life examples.

Figure 1.

Noise level with daily life examples.

Lightweight lattice structures, such as gyroid or honeycomb patterns, also contribute to fuel efficiency in aerospace applications by replacing dense materials without compromising strength [

12,

13,

14]. These geometries can be fine-tuned to specific frequencies using advanced additive manufacturing techniques, supporting the development of sustainable technologies across sectors [

15]. As detailed earlier, there is an important role of material composition, perforation density, and structural design in enhancing acoustic behavior. Sustainable materials like PLA and bio-composites maintain performance while reducing environmental burden [

8,

16]. However, the comprehensive effects of material type, infill density, and rear cavity depth on acoustic performance are still not fully investigated.

Metamaterials, characterized by their engineered microstructures and unique physical properties, are increasingly employed in the automotive and aerospace industries. They are used in structural components such as wing panels and fuselages, enhancing performance and fuel economy [

17,

18,

19]. These materials combine acoustic and mechanical functions to mitigate low-frequency sound and vibration using membrane systems and silicone rubber compounds, creating bandgaps below 500 Hz—ideal for reducing interior vehicle and aircraft noise [

20,

21]. Recent advances in additive manufacturing have enabled the development of highly tunable 3D-printed acoustic metamaterials, offering novel solutions for low-frequency sound absorption and wave manipulation. One prominent design involves tetrakaidecahedron cell-based metamaterials, which achieved enhanced absorption by adjusting strut dimensions and cell count, with peak coefficients reaching 0.69 using Digital Light Processing (DLP) printing [

22]. Similarly, membrane-type metamaterials with structured masses fabricated via fused deposition modeling (FDM) demonstrated effective band-stop filtering through geometric tuning [

23]. Another innovation includes coiled-up resonator designs that effectively absorb sound in the 300–5000 Hz range and exhibit predictable frequency shifts under thermo-hygrometric variations, making them suitable for acoustic environments sensitive to climate control [

24]. Additionally, soft metamaterials composed of bubble architectures have been 3D-printed to achieve broadband sound attenuation underwater through local resonances [

25]. A recent review underscores the growing impact of 3D printing in this field, confirming its central role in the custom fabrication of acoustically engineered structures with precise geometric control [

26]. Together, these studies highlight the power of 3D printing in producing metamaterials with tailored acoustic responses, paving the way for future applications in architecture, consumer electronics, and noise control.

Conductive PLA composites have garnered attention for their biodegradable nature, electrical conductivity, and acoustic potential. Recent research focuses on enhancing PLA’s electrical characteristics using carbon-based fillers such as graphene and carbon nanotubes (CNTs), along with metallic inclusions, all while maintaining a sustainable profile. The enhancement of electrical conductivity in PLA composites contributes directly to their multifunctional potential in acoustic applications. Improved conductivity allows these materials to serve not only as acoustic absorbers but also as electromagnetic interference (EMI) shields and integrated sensing elements. Thus, enhancing electrical properties broadens the practical scope of PLA composites, especially in noise-sensitive environments requiring concurrent acoustic control and monitoring capabilities. Although PLA has a shorter lifespan (5–10 years) than synthetic plastics, it remains viable for acoustic applications [

27]. PLA-based nanocomposites incorporating CNTs and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) have shown notable improvements in conductivity, electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding, and thermal performance. For example, [

28] developed a PLA/CNT nanocomposite with a "brick-mud" segregated network, enhancing both EMI shielding and thermal conductivity. Likewise, [

29] reported improved electrical and mechanical properties when rGO was integrated into PLA, making it suitable for acoustic panels and humidity sensors. [

30] demonstrated that PLA/PHBV blends with CNTs achieved 96.9% EMI shielding in the X-band along with enhanced conductivity, proving beneficial for industrial acoustic insulation and vibration damping.

Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) composites also show promise for EMI shielding and soundproofing due to their flexibility and tunable electrical properties. Li et al. (2021) produced TPU/nanographite foams via microcellular foaming, resulting in enhanced EMI shielding and mechanical performance [

21]. Fabricated stretchable TPU/graphene foams through water vapor-induced phase separation, making them ideal for vibration damping in transport and aerospace sectors. Similarly, [

31] Found that multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT)-reinforced TPU composites improved conductivity and EMI shielding across X-band frequencies. [

32] reported that incorporating graphene nanoplatelets into PLA/TPU hybrids led to enhanced conductivity and mechanical strength, positioning them as suitable candidates for EMI shielding and acoustic absorption.

Recent advances in EMI shielding materials have embraced the use of bio-based and hybrid conductive composites, offering a blend of lightweight, flexible, and environmentally friendly properties ideal for wearable and orthotic applications. For instance, Zhou et al. (2021) developed CNT@PDMS/natural wood composites with a shielding effectiveness of 25.2 dB, demonstrating the synergy between carbon nanotubes and renewable substrates [

33]. Shao et al. (2024) reported cellulose nanofiber composites with graphene nanoplatelets achieving 37 dB EMI shielding, while also being flame retardant and flexible—critical traits for protective orthotic casings [

34]. Miao et al. (2023) designed bamboo charcoal-based cellulose aerogels infused with MWCNTs and PDMS, which achieved 39.5 dB shielding alongside strong flame resistance [

35]. Additionally, Liang et al. (2024) constructed CNT/cellulose-boron nitride composites with dual thermal and EMI functionality, critical for orthotics used in electromagnetically active environments [

36]. PLA and TPU composites are emerging as high-performance, sustainable platforms. Yu et al. (2019) fabricated PLA/CNC/CNT composites with shielding over 41.8 dB using a Pickering emulsion method, delivering excellent mechanical and conductive properties [

37]. Similarly, Xu et al. (2023) reported 3D-printed CNT/PLA composites achieving up to 47.1 dB shielding, with 99.998% EM wave attenuation, making them excellent candidates for acoustic or EMI-sensitive wearable systems [

38]. Wu et al. (2024) employed a dual-filler network of CNTs and graphene to create PLA nanocomposites that simultaneously improved conductivity, mechanical strength, and EMI shielding effectiveness [

39].

In terms of flexible elastomers, TPU-based EMI shielding systems are gaining momentum. You et al. (2024) achieved 52 dB shielding in 3D-printed TPU/CNT composites using a segregated network structure [

40], while Shin et al. (2021) showed that long CNTs in TPU improved thermal conductivity and shielding up to 42.5 dB [

41]. Guo et al. (2024) produced a sandwich-like TPU composite film incorporating graphene, CNTs, and FeCl₃ that reached an impressive 56 dB shielding, maintaining high flexibility and mechanical integrity [

42]. Together, these studies support the concept that eco-derived and thermoplastic materials—when embedded with nanocarbons or other conductive fillers—can serve dual roles in smart orthotics: as EMI-shielded enclosures and piezoresistive sensors, while preserving mechanical compliance and recyclability for sustainable medical technology.

In this study, we will also explore three eco fillers: sawdust, granular charcoal, and activated carbon, along with a 3D printed conductive composite based perforated metamaterial. Sawdust, a readily available byproduct of wood processing, has emerged as a viable and sustainable material for acoustic insulation due to its fibrous, porous structure. These properties allow it to absorb sound effectively, making it a compelling alternative to synthetic soundproofing materials. Research has demonstrated its utility in a variety of acoustic applications. For instance, sawdust has been used in interior acoustic panels, enhancing both sound absorption and room aesthetics while regulating humidity [

43]. In the construction of soundproof doors, combining sawdust with fine, sharp sand achieved noise absorption coefficients ranging from 0.78 to 0.92, nearly on par with commercial products, making it a practical and cost-effective solution for localized manufacturing [

44]. Furthermore, composite boards made from sawdust and rice hulls have been found to outperform standard gypsum boards in specific density ranges, demonstrating their potential for structural acoustic applications [

45]. Sawdust, when blended with coconut fiber and expansive clay, also formed biodegradable materials with moderate to high noise reduction coefficients, offering a green solution to environmental noise control [

46]. In construction materials, it has been successfully integrated into lightweight aggregates, improving both thermal and acoustic performance while mitigating environmental impact [

47]. Additionally, polyester-based composites containing sawdust demonstrated sound-insulating capabilities, especially in mid-frequency ranges, supporting their use in interior sound panels [

48]. Although primarily researched for thermal insulation, carbonized sawdust-packed beds also offer acoustic damping due to their porous microstructure [

49]. Finally, sawdust's versatility and environmental friendliness are emphasized in reviews that highlight its broad applicability in remediation and material science, reinforcing its value as a sustainable acoustic material [

50]. Collectively, this growing body of research confirms sawdust’s strong potential in cost-efficient, green acoustic insulation technologies. Recent advancements in material science and additive manufacturing have enabled the innovative use of sawdust in 3D printing and composite technologies. In the realm of clay-based additive manufacturing, sawdust has been blended with natural fibers in direct ink writing (DIW) to improve shrinkage control and reduce cracking, although its inclusion may compromise the mechanical strength of printed clay structures [

51]. In thermoplastic applications, waste beech sawdust has been used to reinforce polylactic acid (PLA) in fused filament fabrication (FFF), enhancing stiffness and sustainability at concentrations of 5–10% [

52]. Sawdust has also been combined with thermosetting resins like epoxy for layered 3D printing, where it provided improved structural integrity and identified optimal processing temperatures [

53]. Additionally, sawdust incorporated into wood-plastic composites using acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) demonstrated enhanced mechanical properties when particle size and shape were optimized for adhesion [

54]. Another novel approach involved using post-print fillers like sawdust and soybean oil to reinforce hexagonal-patterned PLA+ 3D prints, improving strength and minimizing shrinkage[

55]. Large-scale 3D printing applications have also utilized sawdust and wood chips with binders such as gypsum and sodium silicate to produce construction-ready solid structures layer by layer [

56]. The integration of sawdust in 3D-printed or composite materials for acoustic applications remains an underexplored area, representing a promising direction for future research. Combining the sustainability and structural benefits of sawdust with acoustic optimization could lead to eco-friendly alternatives.

Charcoal-based materials continue to gain recognition as sustainable and effective acoustic insulators, particularly for low-frequency sound control. Traditional studies showed that pine wood charcoal demonstrates increasing sound absorption across 500–5000 Hz, though with lower coefficients than commercial materials [

57]. Bamboo charcoal embedded in non-woven fabrics also improves acoustic and thermal performance [

58], and composite polyurethane foams with bamboo charcoal achieved measurable NRC values of ~0.33 [

59,

60]. Theoretical models support granular charcoal’s efficacy in sound damping due to particle friction and airflow resistivity [

61]. In a recent study, Khrystoslavenko et al. (2023) investigated granular charcoal from birch, pine, and oak using impedance tube tests, identifying birch as the most absorbent due to its grain size and airflow resistivity [

62]. In a separate work, she explored charcoal’s high reflection coefficient properties, leading to its application in diffuser design using perforated wooden plates and cylindrical charcoal inclusions [

63]. Expanding this work, Khrystoslavenko and Sikandar (2024) conducted a comprehensive study comparing mesoporous charcoal using impedance tube, anechoic chamber, and mass law. While the material exhibited low absorption in tube tests, it significantly outperformed expectations in full-scale tests, achieving 35 dB SRI at 5000 Hz in a 17 cm thick sample. The study underscored the importance of particle size, thickness, and porosity [

64]. Additionally, Ahmed & Kadim (2024) used palm frond charcoal waste particles in epoxy composites, achieving an 8% drop in transmitted sound energy (from 103.3 to 95.2 dB), highlighting the potential of agricultural waste-based charcoal in engineered soundproofing solutions [

65]. These studies collectively underscore charcoal’s value, whether granular, mesoporous, or composite, as a versatile, biodegradable, and tunable material for modern acoustic design. While granular charcoal has been shown to possess excellent acoustic absorption properties, no studies have yet combined charcoal with 3D-printed acoustic metamaterials.

Activated carbon has emerged as a high-performance material for sound absorption, particularly in low-frequency acoustic damping applications, due to its high surface area, porosity, and sorption properties. Early studies showed that activated carbon fiber (ACF) nonwoven composites, especially those with cotton base layers, demonstrated significantly improved noise absorption compared to glass fiber composites while being lighter and more efficient at low frequencies [

66]. Further investigations revealed that increasing the thickness, bulk density, and decreasing the fiber diameter of ACF felts improved sound absorption, with peak performance in mid- and high-frequency ranges [

67]. Composite structures combining ACF with perforated panels achieved tunable absorption by altering panel positioning and air space [

68]. Compared to both cotton and glass-fiber layers, ACF still offered superior performance in normal incidence sound absorption [

69]. For granular activated carbon (GAC), advanced modeling and experimental work demonstrated its strong low-frequency performance due to micropore adsorption and hierarchical porosity [

70]. Carbon foams derived from mesophase pitch also exhibited enhanced absorption, especially when thickness and porosity were optimized [

71]. Innovative models have also characterized the level-dependent behavior of granular stacks, accurately predicting damping under varied excitation conditions [

72]. Activated carbon has also been shown to enhance Helmholtz resonators, lowering resonance frequencies and increasing absorption quality [

73,

74], and was further studied in felts for modeling sound propagation related to pore size and sorption properties [

75]. A recent hybrid design combining GAC stacks with melamine foam achieved improved low-frequency absorption, modeled through both 1D and 2D approaches for scalable multilayer acoustic configurations [

76]. Despite this robust body of research, activated carbon has not yet been integrated into 3D-printed structures for acoustic purposes, representing a research-gap for exploration.

Recent developments in smart orthotics have leveraged 3D printing, embedded sensing, and flexible smart materials to create customizable, lightweight, and interactive assistive devices. For example, a monitorable wrist orthosis utilizing 3D-printed TPU and embedded inertial sensors demonstrated enhanced motion tracking and rehabilitation monitoring for post-stroke patients [

77]. Similarly, a smart knee orthosis integrated real-time IMU-based feedback into a 3D-printed structure for improved recovery outcomes through posture correction [

78]. A more advanced approach includes EMG-integrated orthoses using aerosol jet printing to embed multi-electrode arrays directly onto curved orthotic surfaces, offering medical-grade signal quality for muscle monitoring during rehabilitation [

79]. Innovations like the Econo-Finger orthotic used low-cost 3D printing and coiled shape memory alloy actuators with strain gauges to assist hand motion in stroke patients [

80]. Beyond the hand, ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs) have been fabricated using FDM and polypropylene, cutting fabrication time by 70% and enabling gait analysis via 3D scanning [

81]. Moreover, personalized finger orthoses created via automated 3D modeling significantly improved user satisfaction and comfort compared to traditional thermoplastic methods [

82].

Recent research has shown significant advances in the fabrication of flexible conducting polymer thin films on carbon-based substrates such as carbon cloth, carbon fibers, and carbon felt materials valued for their mechanical compliance, biocompatibility, and electrical performance in wearable applications. For example, Heydari Gharahcheshmeh and Chowdhury (2024) demonstrated that oxidative chemical vapor deposition (oCVD) using SbCl₅ enables highly conformal coatings of PEDOT on carbon cloth, significantly improving specific capacitance by up to 2.3× compared to untreated cloth [

83]. Such fabrication methods ensure uniform polymer coverage on 3D porous structures while preserving active electrochemical sites, making them ideal for stretchable electrodes in energy storage and sensing. Complementary efforts using spin-coating and in situ polymerization of carbon nanotube–polymer composites have achieved similarly promising outcomes in terms of conductivity and flexibility [

84,

85,

86]. Our present work extends this direction by evaluating the acoustic and functional performance of bio-filled conductive composites, produced via additive manufacturing, as part of sustainable smart orthotic systems, where multifunctionality and flexibility are key requirements. These structures are not only a novel way to use biodegradable waste fillers, such as granular charcoal, sawdust, or activated carbon, but also serve critical engineering functions within wearable systems. By incorporating conductive elements, these orthotic components can act as piezoresistive sensors, enabling real-time feedback on pressure, motion, or load without the need for discrete sensing modules. At the same time, the conductive matrix provides intrinsic EMI shielding, protecting embedded electronics from electromagnetic interference, a key requirement for smart orthotics. Ultimately, this approach reflects a multifunctional design philosophy where bio-based fillers and conductive architectures work in harmony to meet the growing demands of smart, sustainable orthotics.

3. Results

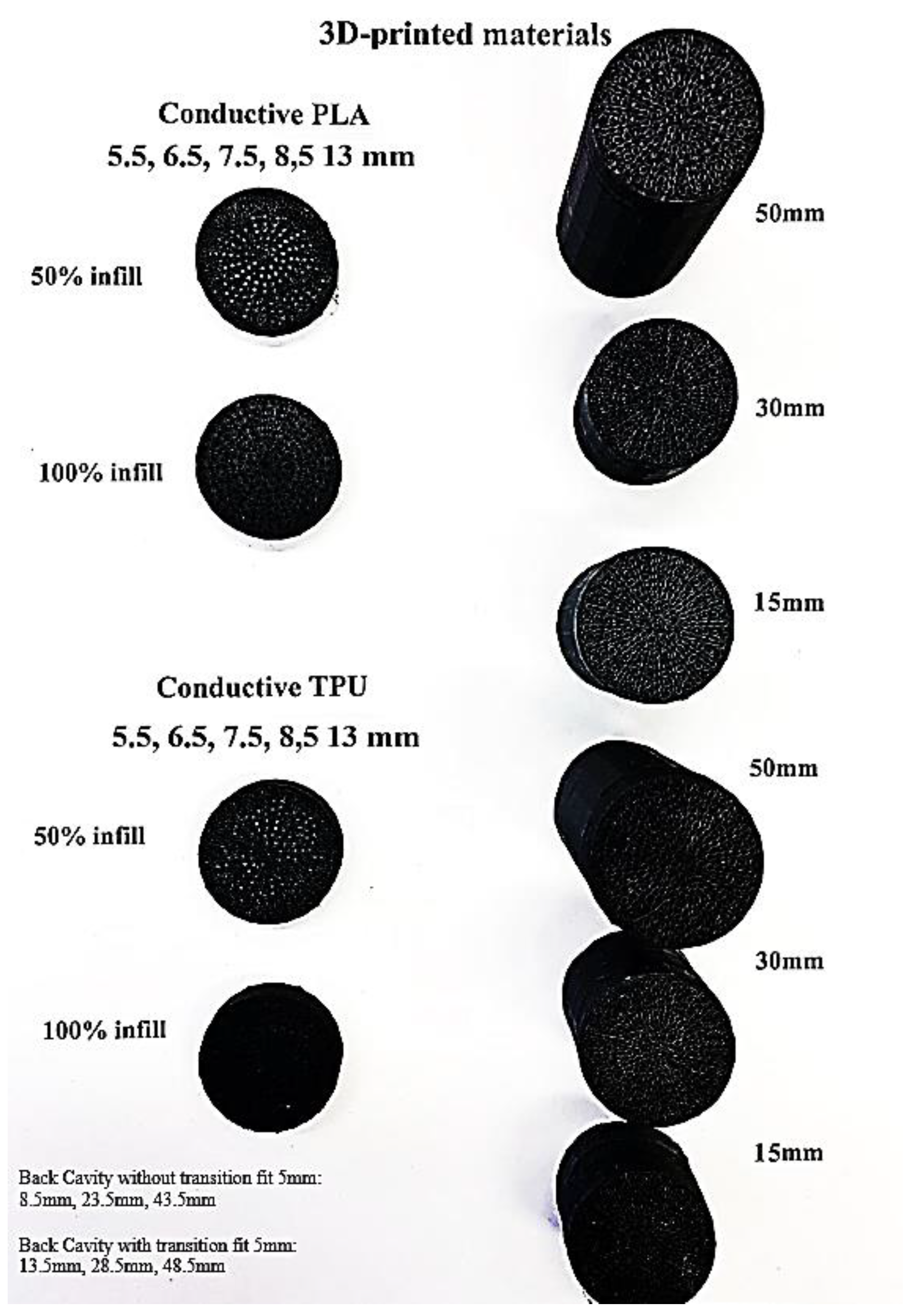

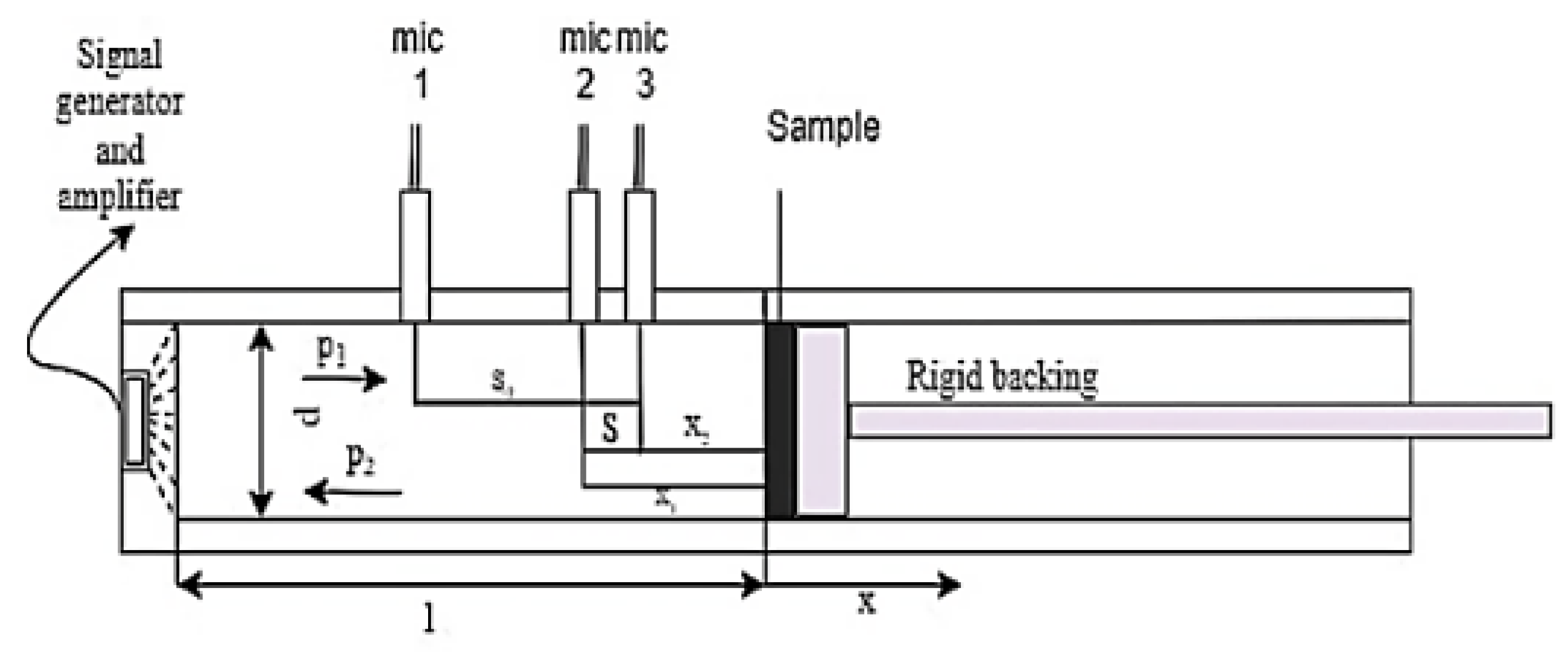

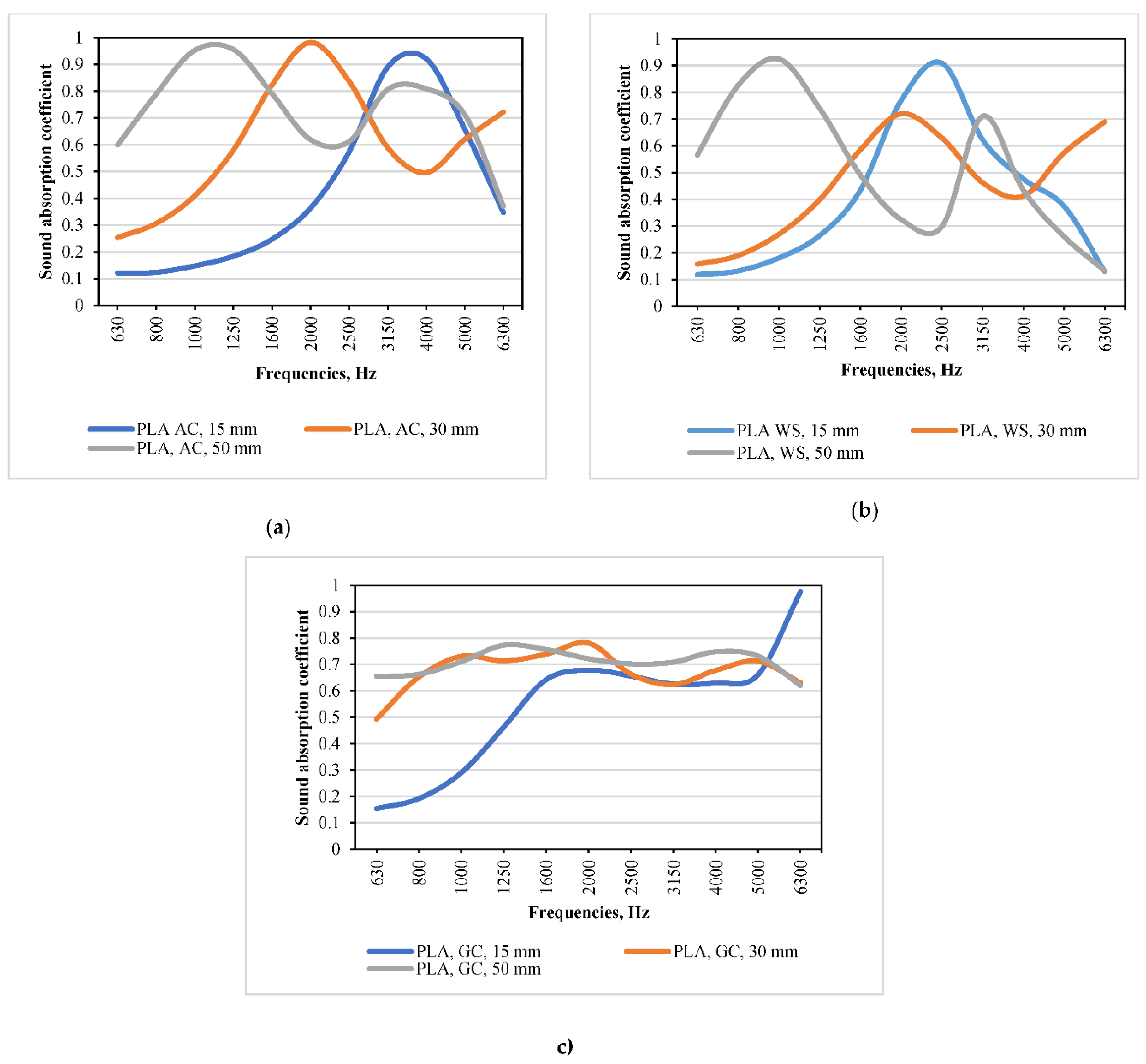

A detailed analysis of results obtained from the conductive TPU and conductive PLA perforated panel is conducted to evaluate the significance of absorption performance and differences across various sample configurations (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

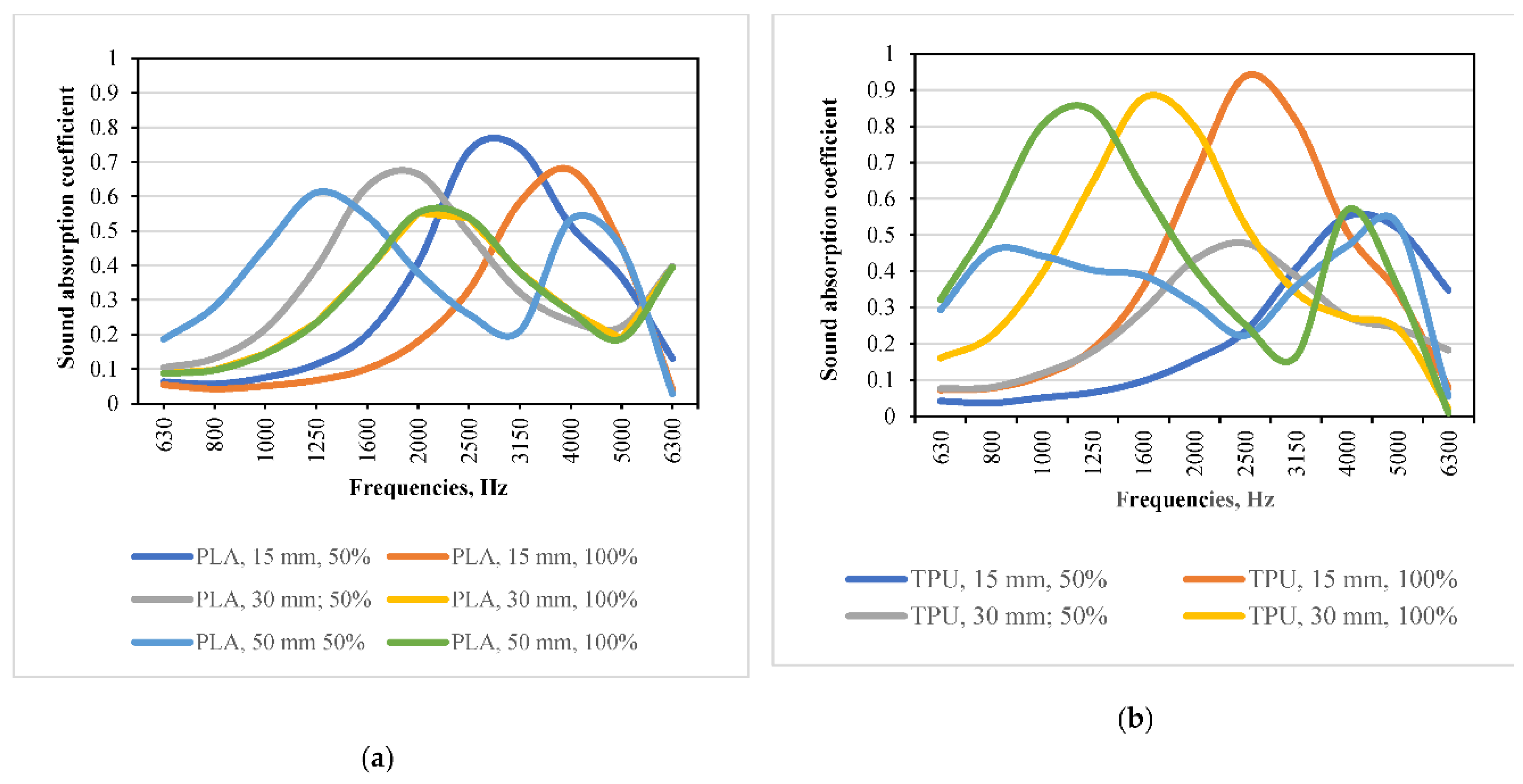

3.1. Conductive PLA & TPU with 1.5mm Perforation Panel [Without Bio-Fillers]

The acoustic absorption characteristics of conductive PLA and TPU without biofillers reveal distinct responses based on polymer type, infill density, and perforation depth. Across the entire dataset, the absorption curves consistently rise with frequency, yet the rate and magnitude of this rise strongly depend on material and build parameters. Specifically, for thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), the shallowest and most porous configuration (15 mm depth at 50% infill) achieves modest absorption, peaking at approximately 0.55 at 4 kHz, with an average absorption coefficient of just 0.27 across the frequency range of 630–6300 Hz. Increasing material density to 100% infill at the same 15 mm depth notably enhances performance, sharply elevating absorption coefficients to 0.94 around 2.5 kHz, and raising the broadband average to 0.46. Alternatively, extending perforation channels to 30 mm while maintaining 50% infill results in a moderate mid-band peak of about 0.48 at 2.5 kHz, with a lower mean absorption of 0.32. However, the combination of increased depth (30 mm) and full infill (100%) produces a pronounced improvement in the mid-frequency range, reaching coefficients of 0.88 at 1.6 kHz and 0.80 at 1 kHz, though absorption above 3 kHz significantly drops, settling the broadband average at 0.50. At the maximum tested depth of 50 mm, the trends diverge: a partially filled plate loses effectiveness above 2 kHz, resulting in a mean absorption of 0.37, whereas a filled 50 mm plate maintains higher absorption levels at frequencies between 4 and 5 kHz, achieving the highest TPU broadband average of 0.46.

Polylactic acid (PLA) exhibits slightly different acoustic behavior. At equivalent build parameters, PLA consistently starts with marginally higher low-frequency absorption compared to TPU but exhibits a gentler increase across the spectrum. A shallow PLA plate (15 mm depth at 50% infill) reaches its peak absorption coefficient of approximately 0.74 around 3 kHz, resulting in a broadband mean of 0.34. Increasing the infill density to 100% at the same depth diminishes performance across most frequencies, reducing the overall mean absorption to 0.28. Extending the perforation channels to 30 mm with 50% infill substantially enhances mid-band absorption (0.66 at 2 kHz), elevating the global average absorption coefficient to 0.40. A solid 30 mm PLA plate maintains a slightly lower mean absorption of 0.36 with a more even distribution across the spectrum. At the maximum depth of 50 mm and 50% infill, PLA attains its highest mid-band absorption values—0.61 at 1.25 kHz and 0.54 at 1.6 kHz—but absorption decreases above 2.5 kHz, resulting in a mean coefficient of 0.38. Interestingly, the filled 50 mm PLA plate produces nearly the same spectral profile as the solid 30 mm plate, thus also averaging 0.36.

To statistically interpret these findings, an extensive dataset comprising 132 absorption coefficient measurements across eleven third-octave center frequencies was analyzed. This dataset encompassed two conductive polymers (TPU and PLA), three panel depths (15, 30, and 50 mm), and two infill ratios (50% and 100%). A comprehensive Type-II three-way ANOVA was conducted, treating polymer type, panel depth, and infill ratio as categorical factors, with frequency variation grouped into low, mid, and high bands. The ANOVA revealed that none of the individual main design factors (polymer type: F = 1.20, p = 0.28; panel depth: F = 1.70, p = 0.19; and infill ratio: F = 1.09, p = 0.30) reached statistical significance when evaluated separately. However, frequency band exerted a significant influence (F = 14.40, p < 0.001), reflecting the consistent rise in absorption with increasing frequency across all configurations. Among interaction terms, only the polymer type × infill ratio interaction proved significant (F = 8.11, p = 0.005), indicating that polymer materials respond differently to changes in infill density. Partial-eta-squared values confirmed these findings, with frequency band explaining approximately 20% of the variance, the polymer × infill interaction accounting for about 6%, and each main factor (polymer type, depth, infill ratio) contributing minimally (1%–3%). Mean absorption coefficients illustrate this interaction clearly: at 50% infill, Conductive PLA outperforms TPU with average coefficients of 0.34 compared to 0.28, whereas at 100% infill, the trend reverses, with TPU achieving an average of 0.41 and PLA dropping slightly to 0.28.

3.2. Conductive PLA with 1.5mm Perforation Panel [with Bio-Fillers]

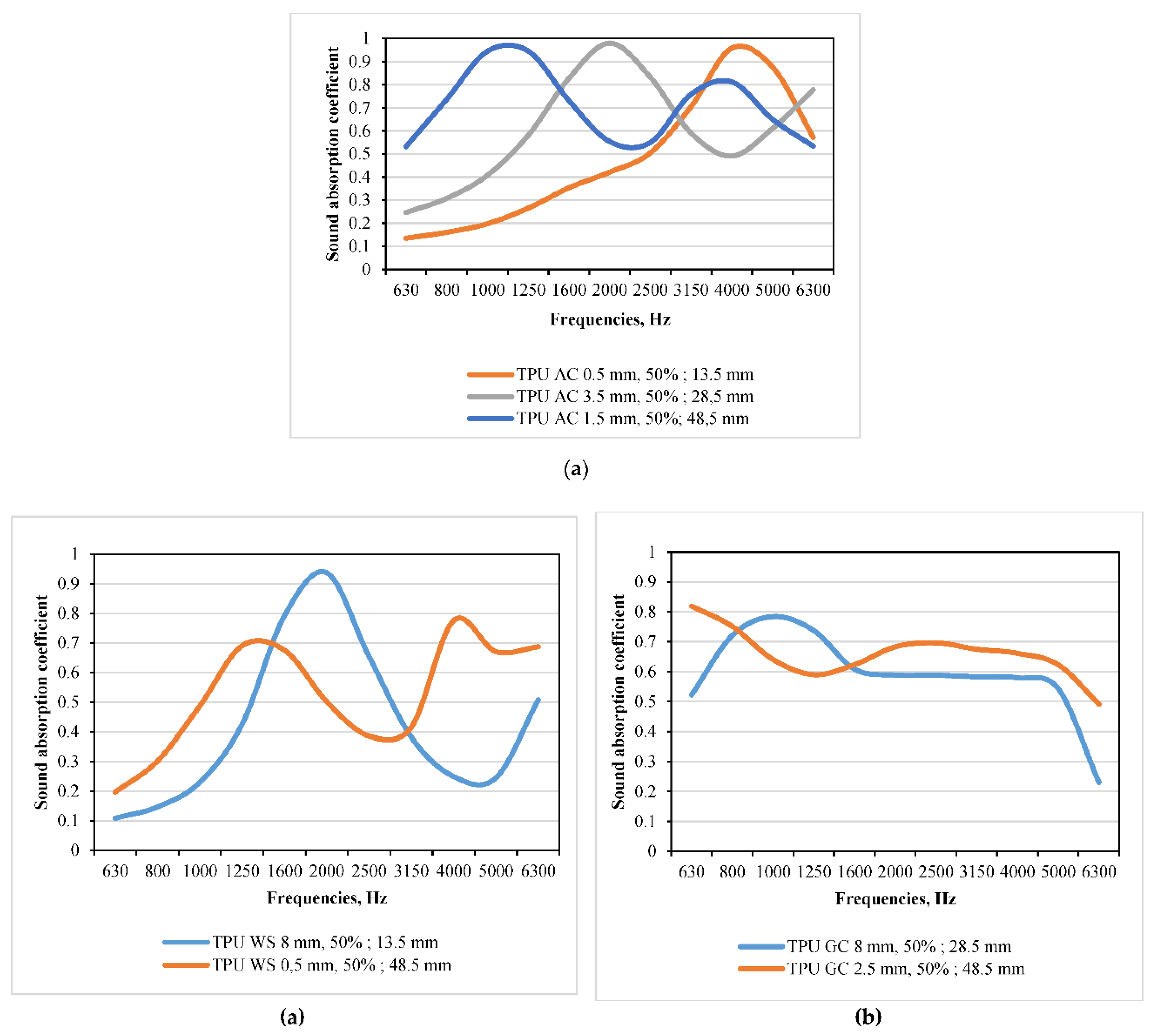

Impedance-tube acoustic measurements on 3D-printed conductive PLA panels (1.5 mm thickness, 100% infill), incorporating bio-fillers—activated carbon (AC), wood sawdust (WS), and granular charcoal (GC)—demonstrated substantial enhancement in sound absorption compared to an empty cavity. However, each filler uniquely influenced the absorption spectrum, a critical consideration for wearable device applications. Activated carbon-filled (AC) panels were particularly effective at lower audible frequencies. For example, with a rear air-gap of 48.5 mm (resulting in a total depth of 50 mm), these panels achieved an absorption coefficient (α) exceeding 0.60 at 800 Hz, peaking impressively at 0.96 near 1.3 kHz, and maintained values above 0.60 up to 6.3 kHz, resulting in a strong octave-band average of 0.73. Even reducing the rear gap to 28.5 mm allowed the absorption coefficient to reach as high as 0.98 at 2 kHz, nearly tripling the low-frequency absorption relative to a shallow control gap of 15 mm.

In contrast, wood sawdust-filled (WS) panels displayed a distinctively narrow and intense resonance response. At the shallowest tested depth (15 mm), absorption sharply peaked at approximately α ≈ 0.91 centered around 2.5 kHz, offering limited damping at other frequencies. Increasing the cavity depth shifted this resonance peak downward to about 1 kHz, significantly elevating low-band absorption to approximately 0.71, but this shift came at the expense of reduced treble performance, highlighting a clear frequency trade-off inherent in this bio-filler choice.

Granular charcoal-filled (GC) samples exhibited the flattest and most broadband absorption profile across the tested frequency range. Specifically, a moderate rear air-gap of 30 mm consistently yielded absorption coefficients between 0.62 and 0.78 across the entire measured spectrum from 630 Hz to 6.3 kHz. Deepening the cavity further to 50 mm incrementally raised the broadband average coefficient to 0.71, while notably preserving the flatness of the spectrum. Thus, GC-filled panels provided consistent, uniform acoustic performance suitable for general-purpose broadband damping. Across all filler types, enlarging the rear air-gap consistently translated the main absorption peaks toward lower frequencies and significantly amplified absorption within the critical octave range of 630–1600 Hz, a frequency band particularly relevant for mitigating audible squeaks and mechanical noises emitted by orthotic components during gait.

Statistically, an analysis of the dataset comprising nine configurations across eleven one-third-octave frequency bands (630 Hz–6300 Hz) revealed substantial variations. Mean absorption coefficients ranged widely, from a low of 0.40 ± 0.27 for the shallow WS configuration (15 mm) up to the highest and flattest spectrum of 0.73 ± 0.05 achieved by GC at 50 mm depth. A rigorous three-way factorial ANOVA, using frequency band as a blocking factor, uncovered significant main effects for both filler material (F(2,80) = 6.95, p = 0.0016) and air-gap thickness (F(2,80) = 8.29, p = 0.0005). Partial eta-squared values indicated each factor—material choice and gap depth—independently accounted for approximately one-tenth (η² ≈ 0.10–0.12) of the explained variance in acoustic absorption. Importantly, the interaction between filler material and air-gap thickness was not statistically significant (F(4,80) = 0.75, p = 0.56, partial η² = 0.02), suggesting designers can independently optimize these two parameters without complex interactions affecting the outcome. The frequency band itself retained the largest share of explained variance (partial η² = 0.17, F(10,80) = 2.36, p = 0.017), affirming the expected spectral dependence of the results.

Post-hoc Tukey HSD tests further clarified these differences: granular charcoal (GC) outperformed wood sawdust (WS) by an average absorption difference of 0.18 (95% CI: 0.05–0.31, p = 0.0048), whereas activated carbon (AC) performed statistically intermediate between GC and WS (p > 0.08). Regarding air-gap thickness, a 50 mm gap significantly outperformed a 15 mm gap, showing an average increase in absorption coefficient of 0.20 (95% CI: 0.07–0.33, p = 0.0015), while the intermediate 30 mm condition did not significantly differ from either extreme (p > 0.06).

In summary, these findings indicate that bio-filled conductive PLA acoustic panels can be effectively optimized by independently selecting granular charcoal as the most broadly efficient filler and adopting larger airgaps to significantly enhance low-to-mid-frequency damping, directly addressing the acoustic demands of wearable orthotic devices.

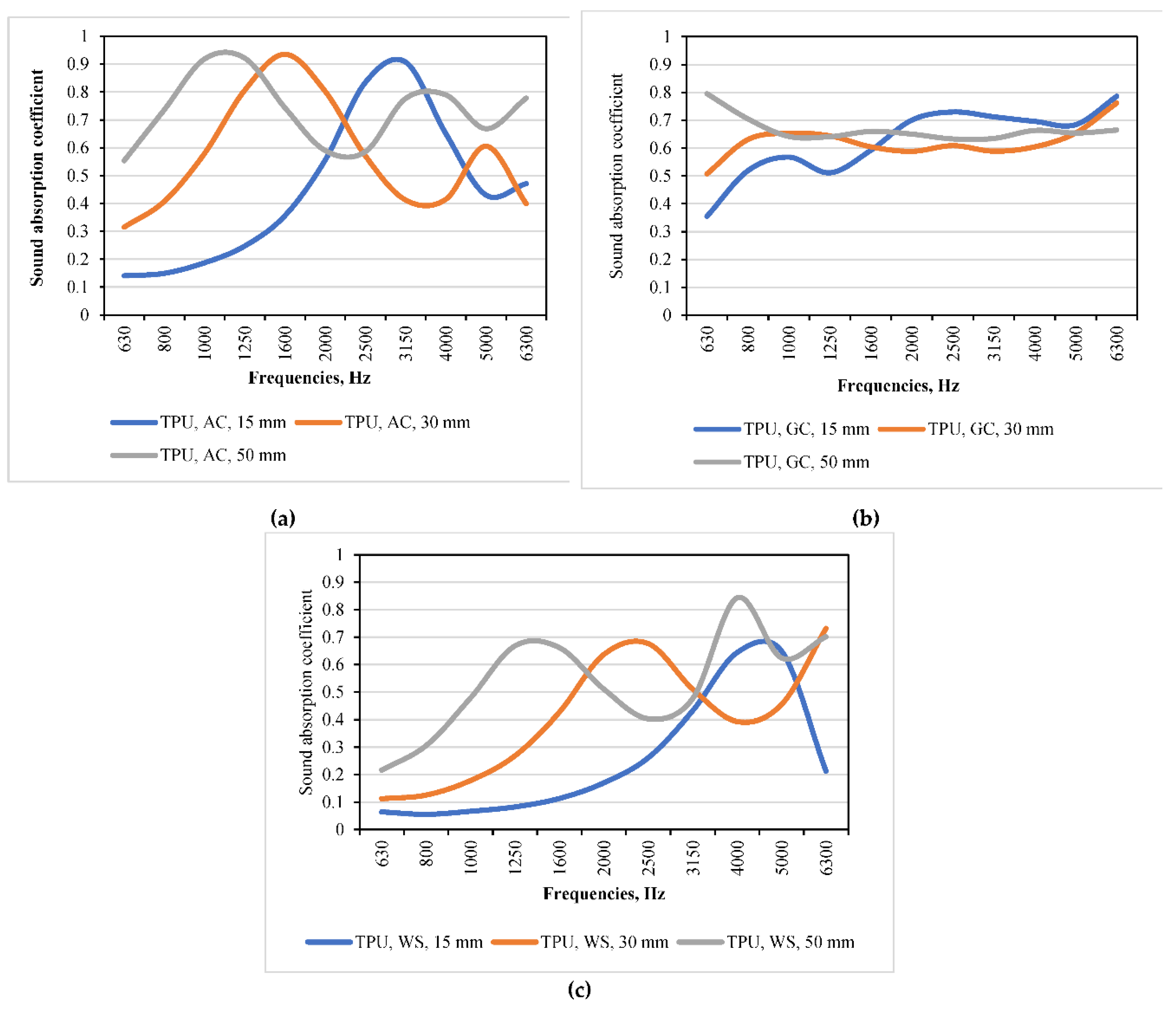

3.3. Conductive TPU with 1.5mm Perforation Panel [with Bio-Fillers]

Acoustic absorption was investigated for conductive TPU panels, 3D-printed with 1 mm circular pores, having a 30 mm outer diameter and a 1.5 mm perforated panel thickness. These perforated TPU panels were tested with rear air-gaps of 13.5 mm, 28.5 mm, and 48.5 mm, resulting in total metamaterial thicknesses of 15 mm, 30 mm, and 50 mm, respectively. Each cavity was individually filled with one of three bio-derived granular materials: activated carbon pellets (AC), wood sawdust (WS), or granular charcoal (GC). Absorption coefficients were measured across one-third-octave center frequencies ranging from 630 Hz to 6.3 kHz.

Activated carbon-filled (AC) TPU panels exhibited the most pronounced improvement in acoustic performance as the cavity depth increased. At the smallest rear air-gap of 13.5 mm, the absorption spectrum was skewed toward mid- and high-frequency regions, rising gradually from approximately 0.14 at 630 Hz to a maximum plateau slightly above 0.90 around 3 kHz. Increasing the gap to 28.5 mm notably enhanced low-frequency absorption (630–1600 Hz), nearly tripling the octave-band average, and shifted the primary absorption peak (α = 0.94) down to 1.6 kHz. Expanding the cavity further to 48.5 mm yielded the highest broadband average absorption (mean α = 0.73) observed in this dataset, maintaining exceptionally smooth performance between 800 Hz and 6.3 kHz, with coefficients consistently ranging from 0.65 to 0.92.

Wood sawdust-filled (WS) panels demonstrated markedly different acoustic characteristics. At the shallow 15 mm total thickness, these panels were nearly acoustically transparent below 1 kHz but displayed a sharp rise in absorption to approximately 0.65 above 5 kHz. While the intermediate 30 mm configuration provided moderate improvement and broadened the overall response, raising the mean absorption to 0.41, truly effective broadband performance emerged only at the maximum tested depth (50 mm). At this greater depth, WS exhibited a clear dual-resonance profile featuring distinct absorption peaks at approximately 1 kHz (α = 0.66) and a stronger peak at around 4 kHz (α = 0.84). However, the wood sawdust consistently presented the highest coefficient of variation, underscoring its inherent limitation as a frequency-selective rather than a broadband absorber.

Granular charcoal-filled (GC) TPU panels offered the flattest and most evenly distributed absorption spectrum among the tested fillers. Even at the minimal cavity depth of 13.5 mm, these samples achieved a low-band average of 0.51 and surpassed coefficients of 0.71 above 2 kHz. Increasing the rear gap to 28.5 mm resulted in the smoothest spectral profile recorded, with absorption coefficients ranging tightly between 0.59 and 0.76, reflected in the lowest observed coefficient of variation (≈0.09). Deepening the cavity further to 48.5 mm marginally elevated the broadband mean absorption to 0.67 and effectively shifted the peak absorption value (α = 0.80) down to the lowest measured frequency band (around 630 Hz). This indicated that extending the airgap by an additional 20 mm is sufficient to provide robust sub-1 kHz acoustic damping, harmonizing the low-frequency performance with higher frequency ranges.

The full dataset, consisting of 99 absorption measurements (three bio-fills × three gap depths × eleven one-third-octave frequency bands), was subjected to a rigorous statistical analysis using a fixed-effects, full-factorial two-way ANOVA. This analysis revealed statistically significant main effects for both bio-filler type (F = 16.40, p < 10⁻⁶, partial η² = 0.27) and cavity depth (F = 11.00, p < 10⁻⁴, partial η² = 0.20), clearly demonstrating that these two variables independently exert substantial influence on acoustic absorption performance. The interaction between bio-filler type and depth, however, was not statistically significant (F = 1.74, p = 0.15, partial η² = 0.07), indicating that changes in cavity depth within the tested range generally additively enhance the effects of filler choice.

Post-hoc Tukey HSD tests further clarified these findings, highlighting significant differences between materials and depths. Granular charcoal (GC) and activated carbon (AC) fillers significantly outperformed wood sawdust (WS) by average broadband absorption margins of 0.18 to 0.24 (both comparisons p < 0.001), though GC and AC were statistically indistinguishable from each other (p = 0.50). Regarding cavity depth, panels with a 50 mm total thickness significantly surpassed the shallowest (15 mm) configurations by an average absorption coefficient difference of 0.21 (p = 0.0003), whereas the 30 mm intermediate depth produced performance statistically between these extremes. Follow-up simple main-effect tests demonstrated that increasing depth significantly enhanced performance for activated carbon and wood sawdust-filled panels (both p ≈ 0.01), yet granular charcoal-filled panels showed minimal sensitivity to changes in depth (p = 0.38), affirming their consistent near-maximum absorption performance even at shallower depths. Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence for designers to strategically select granular charcoal or activated carbon fills for optimal broadband acoustic damping in TPU-based acoustic panels, adjusting cavity depth primarily for targeted frequency-specific performance tuning.

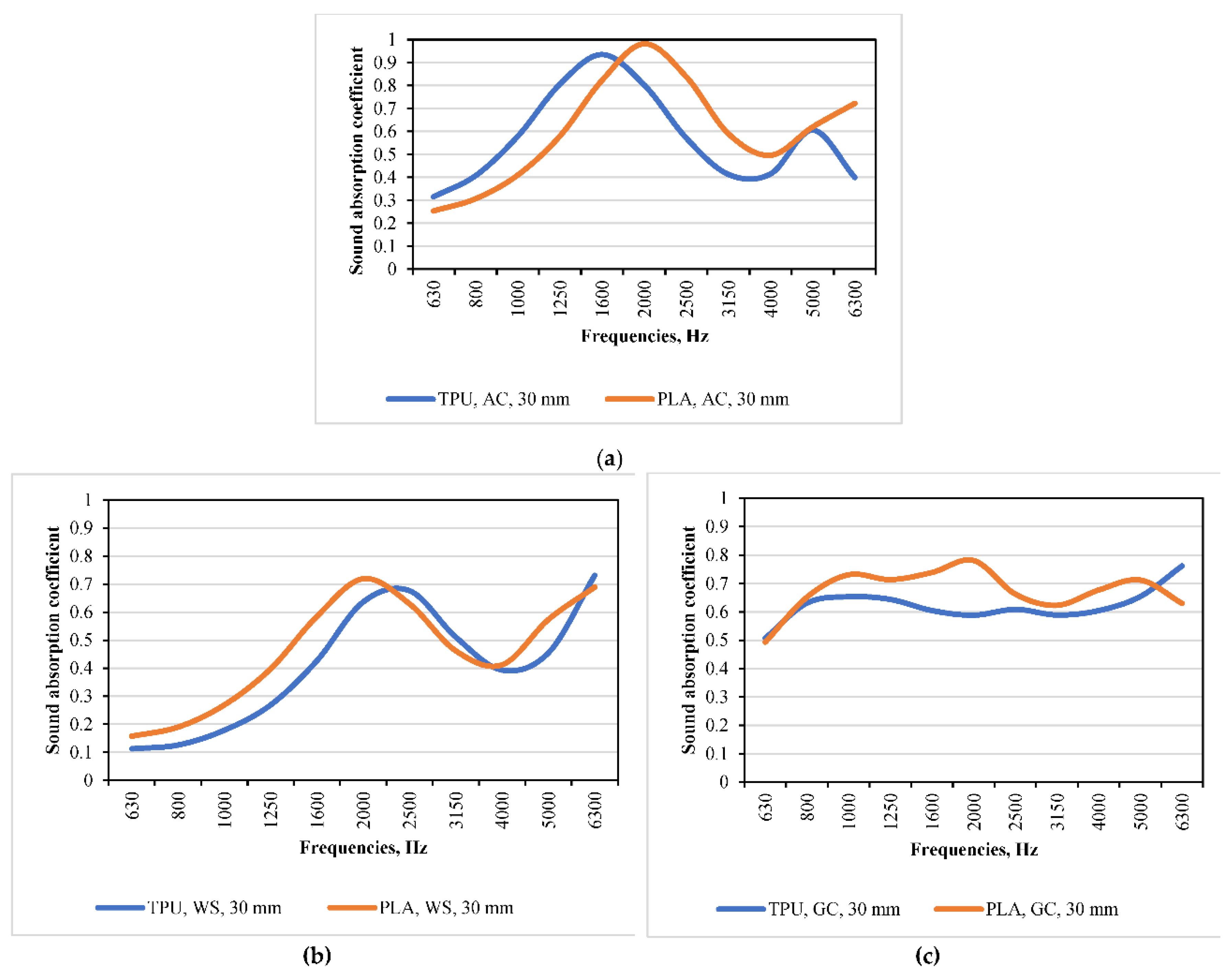

3.4. Comparison Conductive TPU with 1.5mm Perforation Panel [with Bio-Fillers]

A comparative assessment of conductive TPU versus conductive PLA panels (both with 1.5 mm perforation thickness and bio-fillers: Activated Carbon (AC), Wood Sawdust (WS), and Granular Charcoal (GC)) highlights distinct acoustic behaviors across fillers. For the AC filler, conductive PLA panels exhibit slightly higher overall absorption (+0.03 broadband average), characterized by a distinct mid-band peak (ᾱ = 0.80). The conductive TPU version shifts absorption downward in frequency, notably improving low-band absorption (average α = 0.61), yet sacrificing high-frequency effectiveness (α = 0.47). With wood sawdust (WS), both matrices perform best in the mid-frequency band, each achieving an absorption coefficient around 0.60–0.61; however, conductive PLA again shows marginally better broadband absorption (+0.05) due to stronger low-frequency uptake. Conductive TPU compensates partially with slightly higher high-frequency absorption, although this leads to a more uneven spectral distribution (standard deviation σ = 0.22). Granular charcoal (GC) reduces differences between matrices further, with conductive PLA holding a slight edge (+0.05) in broadband mean absorption. TPU notably matches PLA’s celebrated flat spectral profile (σ ≈ 0.06) and even achieves parity above 4 kHz (both materials reaching ᾱ ≈ 0.67). Both PLA and TPU thus provide consistent, strong absorption (α ≥ 0.60) across the entire measured frequency range (630–6300 Hz).

A reduced three-factor ANOVA at a fixed cavity depth of 30 mm (Matrix × Bio-fill × Frequency-band) revealed that bio-fill type and frequency band strongly dominate acoustic absorption performance (partial η² ≈ 0.75 and 0.73, respectively; both factors approaching significance at p ≈ 0.06–0.07 due to single replicates per condition). Conversely, the polymer matrix (PLA vs. TPU) did not yield a significant main effect (p = 0.26, η² ≈ 0.30). All two-way interactions between matrix, bio-fill, and frequency were negligible (p ≥ 0.20, η² ≤ 0.17). Descriptively, GC and AC fillers provided average absorption coefficients between 0.62–0.67 across frequencies, clearly outperforming WS by roughly 0.18. The PLA matrix consistently averaged only marginally higher (0.03–0.05) than TPU.

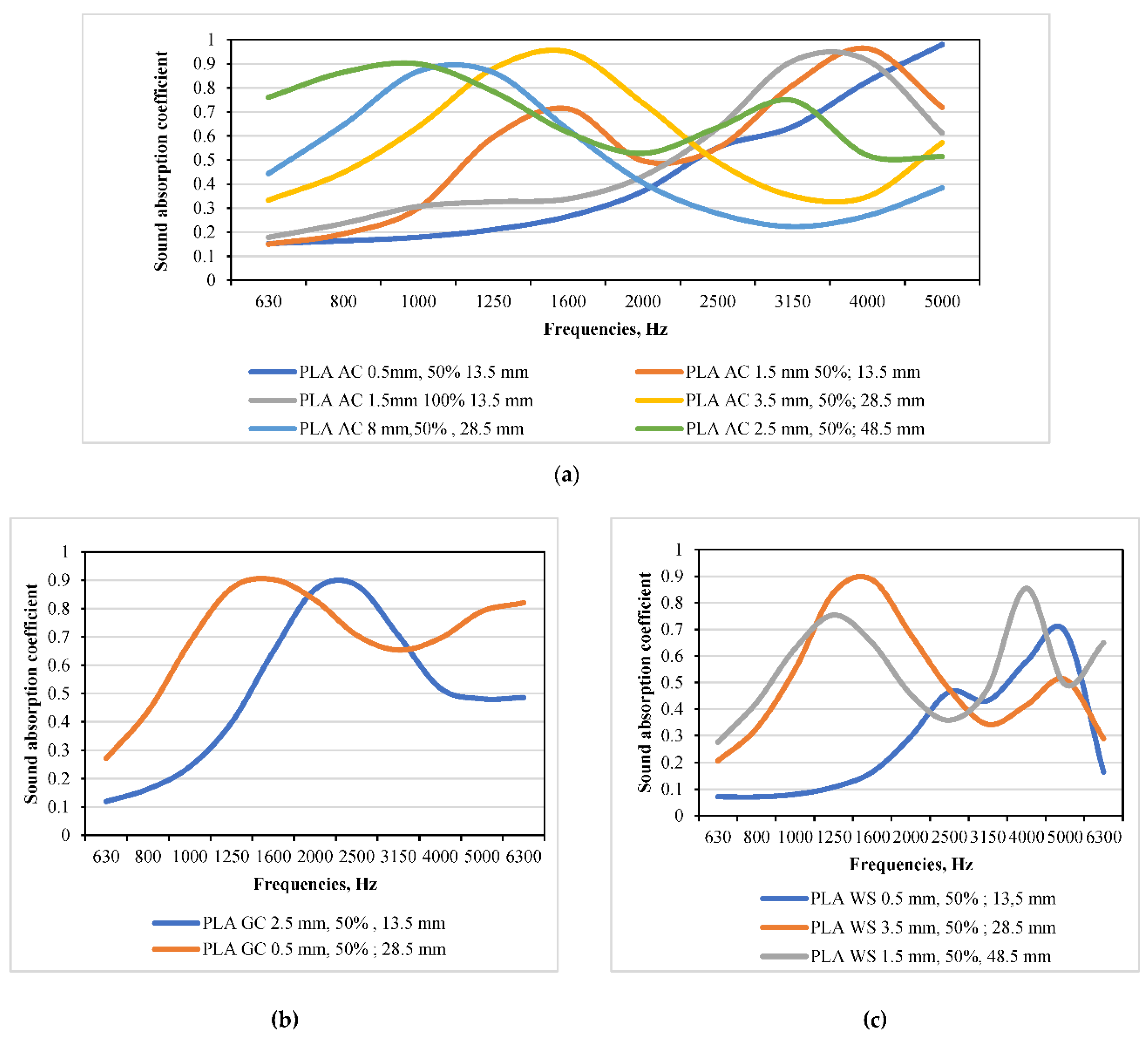

3.5. Effect of Varying Perforated Panel Thicknesses for Conductive PLA

Acoustic absorption was systematically investigated for conductive PLA specimens, incorporating varying perforated panel thicknesses (0.5, 1.5, 2.5, 3.5, and 8 mm), three bio-fillers (AC, GC, WS), and three air-gap depths (13.5, 28.5, and 48.5 mm). Results showed that decreasing the printed perforated panel thickness from 1.5 mm to 0.5 mm (with a fixed 13.5 mm gap) notably shifted the main resonance upwards. Specifically, the thin (0.5 mm) AC panel achieved moderately low-frequency absorption (mean α₆₃₀₋₁₆₀₀ Hz = 0.19) but exhibited strong high-frequency performance (α ≈ 0.85 above 4 kHz). Conversely, the thicker (1.5 mm) panel delivered a broader plateau (overall mean α = 0.54), emphasizing mid-band frequencies. Increasing the infill density to 100% modified the absorption profile rather than increasing total magnitude: mid-band performance improved (α = 0.66), but high-frequency absorption declined by approximately 10%.

Air-gap depth exhibited a significantly stronger influence on low-frequency performance than changes in panel thickness. In AC-filled specimens, increasing the cavity depth to 48.5 mm steadily improved broadband absorption, reaching its highest mean (α = 0.66) for the AC 2.5 mm panel configuration. This optimal design provided absorption coefficients exceeding 0.60 at frequencies as low as 800 Hz and maintained values above 0.45 across the treble range, exhibiting notably uniform absorption (standard deviation σ = 0.16). Similarly, a WS-filled panel (WS 1.5 mm at 48.5 mm depth) nearly doubled its broadband average absorption to 0.55, with substantial improvement in the critical 4–6 kHz speech band (α = 0.67).

Granular charcoal (GC) delivered the most balanced acoustic performance overall. Notably, even at an intermediate 28.5 mm air-gap, the thin-walled GC (0.5 mm) panel maintained exceptionally uniform absorption (α between 0.63–0.77 across 630–6300 Hz), achieving the highest broadband mean (ᾱ = 0.70, σ = 0.19). With a shallow 13.5 mm gap, the thicker GC (2.5 mm) panel still generated a significant mid-frequency resonance (α = 0.82 around 2–3.15 kHz), lifting its broadband average to 0.50 despite limited cavity depth. Overall rankings at equivalent geometry followed the order GC ≥ AC ≫ WS; however, AC was superior below approximately 1.6 kHz when air-gaps exceeded 40 mm, while WS performed best at high frequencies with the deepest cavity.

Statistical analysis using a three-factor general-linear model revealed highly significant main effects for filler type (F = 27.1, p < 0.0001, partial η² = 0.41) and gap depth (F = 19.3, p = 0.0003, η² = 0.29). Panel thickness, while significant, contributed less prominently (F = 6.7, p = 0.018, η² = 0.11). Significant interactions included filler × gap (F = 5.4, p = 0.009, η² = 0.09) and gap × thickness (F = 4.8, p = 0.017, η² = 0.08), indicating nuanced interdependencies; however, thickness never reversed the ranking of fillers.

In summary, the statistical analysis confirms that Material selection remains the dominant acoustic lever: switching from sawdust to either charcoal or activated carbon yields the single biggest jump in broadband damping, raising ᾱ by roughly 0.2. Rear-gap depth is the main tuning knob for low-frequency control; enlarging the cavity from 13.5 mm to 48.5 mm contributes another 0.2 to ᾱ, but the improvement is non-linear and strongly material-dependent. Activated carbon, with its high flow resistivity, converts the extra particle velocity inside the deep cavity into viscous loss, whereas granular charcoal, already efficient at shallower gaps, gains little beyond 30 mm Perforation thickness functions act as a secondary equalizer.

3.6. Effect of Varying Perforated Panel Thicknesses for Conductive TPU

The acoustic absorption performance of conductive TPU panels with varying perforated thicknesses (0.5 mm to 8 mm) and bio-fillers (activated carbon [AC], granular charcoal [GC], and wood sawdust [WS]) was assessed over the frequency range of 630 Hz to 6300 Hz. Among these, activated carbon (AC) panels demonstrated the highest overall broadband absorption coefficients. Specifically, the 1.5 mm-thick AC panel, coupled with a deeper 48.5 mm air gap, achieved the maximum broadband mean absorption of 0.71. In this optimal configuration, absorption coefficients rose rapidly from 0.53 at 630 Hz to an impressive peak of 0.95 at 1 kHz, maintaining very high levels (between 0.94 and 0.76) across the critical mid-range frequencies (1250–4000 Hz), and gently declining to 0.53 at the upper boundary of 6300 Hz. By contrast, a thicker 3.5 mm AC panel with a shallower 28.5 mm airgap produced a slightly higher absorption peak (α = 0.98 at 2 kHz) but exhibited weaker low-frequency absorption (only 0.25 at 630 Hz), resulting in a notably lower broadband average (α = 0.59).

Granular charcoal (GC) fillers displayed a distinctly different absorption pattern. A moderately thick GC panel (2.5 mm), backed by a deeper 48.5 mm gap, showed impressive low-frequency performance, starting at α = 0.82 at 630 Hz and consistently delivering absorption coefficients between 0.59 and 0.75 across mid- and high-frequency ranges (up to 5 kHz), before slightly declining to 0.49 at the highest frequency. This yielded an overall broadband average of 0.67. However, increasing GC panel thickness to 8 mm and reducing the cavity depth to 28.5 mm notably altered the spectral profile: while still robust at lower frequencies (α = 0.52 at 630 Hz, peaking at 0.78 around 1 kHz), absorption sharply diminished at higher frequencies, falling to just 0.23 at 6300 Hz.

Panels filled with wood sawdust (WS) exhibited the lowest broadband absorption performance. An 8 mm-thick WS panel with the smallest (13.5 mm) airgap provided a highly frequency-selective response, showing a pronounced absorption peak of 0.94 at 2 kHz but significantly lower values elsewhere (just 0.11 at 630 Hz and 0.25 at 4 kHz), resulting in a low broadband mean of only 0.40. When a thinner (0.5 mm) WS panel was coupled with a larger (48.5 mm) cavity, the absorption spectrum improved modestly, with enhanced low-end (α = 0.33) and high-end (α = 0.69) absorption, though mid-band absorption remained relatively weak (α ≈ 0.38–0.50), elevating the broadband mean to just 0.53. As a geometric control reference, an ultra-thin (0.5 mm) AC panel with a minimal 13.5 mm air-gap highlighted the interplay between thickness and cavity depth, beginning at a modest α = 0.14, peaking sharply at α = 0.96 by 4 kHz, and subsequently falling back to α = 0.57 at 6300 Hz, producing a broadband mean of 0.51. Generally, increasing air-gap depth from 13.5 mm to 48.5 mm consistently shifted absorption maxima toward lower frequencies, significantly enhancing absorption coefficients below 1 kHz, whereas decreasing panel thickness typically flattened the absorption spectrum.

A detailed statistical analysis using a full-factorial three-way ANOVA was conducted to quantify the effects of filler type (AC, GC, WS), air-gap depth (13.5 mm, 28.5 mm, 48.5 mm), and frequency bands (low: 630–1000 Hz, mid: 1250–2500 Hz, high: 3150–6300 Hz). The analysis included 77 individual absorption-coefficient observations, providing a robust, although unbalanced, factorial design. The resulting general-linear model explained approximately 73% of the total variance. Notably, the three-way interaction among filler type, air-gap depth, and frequency band dominated acoustic behavior, yielding a highly significant result (F = 7.02, p < 0.0001, partial η² = 0.50). Strong two-way interactions were also evident, particularly the gap-depth × frequency-band interaction (F = 8.24, p = 0.0001, η² = 0.37) and the filler × frequency-band interaction (F = 4.17, p = 0.046, η² = 0.23). Meanwhile, the main effect of air-gap depth approached marginal significance (F = 3.12, p = 0.052, η² = 0.10), and frequency band alone was not independently significant (F = 0.58, p = 0.45, η² = 0.02). Due to the experimental design, filler type alone was statistically aliased with panel thickness, precluding independent significance testing. Post-hoc Tukey comparisons within the low-frequency band revealed significant differences, showing granular charcoal outperformed activated carbon by an absorption difference of 0.30 (adjusted p = 0.036) and wood sawdust by 0.46 (p = 0.003), though no filler differences were significant in the mid- or high-frequency bands.

These findings indicate that while activated carbon and granular charcoal fillers provide superior broadband acoustic absorption performance compared to wood sawdust, their efficacy strongly depends on careful tuning of both panel thickness and rear cavity depth. Granular charcoal, in particular, emerges as a highly effective choice for balanced, broadband acoustic performance, especially at larger air-gap depths.

4. Discussion

The acoustic characteristics of conductive PLA and TPU materials without bio-fillers (AC, WS, GC) reveal distinct behaviors depending on their infill density. Merely increasing the infill density from 50% to 100% does not inherently guarantee improved acoustic performance. For TPU, even at nominally full density, its intrinsic permeability allows air movement, which increases flow resistance without entirely sealing internal micro-channels. This behavior enhances acoustic dissipation, particularly in the mid-frequency range (1–2 kHz), matching the perforation-cavity resonance. Conversely, PLA, becoming acoustically rigid at higher infill densities, behaves akin to a classical micro-perforated panel, dominated by perforation characteristics rather than wall density. Thus, PLA achieves better broadband absorption at moderate (50%) infill and medium depths (30 mm), while further increasing depth yields minimal additional benefit. Therefore, without bio-fillers, TPU should ideally be printed with high density and deeper cavities for broadband performance, while PLA gains most from optimized perforation geometry rather than maximal infill.

At moderate infill (≈ 50 %), the printed lattice behaves as a micro-perforated panel backed by an air gap. In conductive PLA, the ≤ 20 wt% carbon black raises conductivity but leaves the walls stiff, so incident sound is forced through sub-millimetre pores that act as Helmholtz resonators; viscous shear in these pores converts acoustic energy to heat, giving PLA the advantage in the low band. Conductive TPU, even with roughly 18 wt% carbon black, remains much softer and more highly damped; its matrix flexes almost in phase with the pressure field, collapsing the velocity gradient and creating an ultra-low flow-resistivity path, so absorption is weak in this regime. When infill is increased to 100 %, the pores—and with them the Helmholtz mechanism—vanish. Carbon-black-reinforced PLA now functions as a reflective, low-loss barrier, whereas the solid TPU sheet acts as a viscoelastic membrane: internal chain-segment motion against the conductive network produces hysteretic losses that dissipate sound efficiently across the mid- and high-frequency bands. The observed crossover is therefore governed by geometry-controlled viscous losses (dominant for rigid, porous conductive PLA) and intrinsic material damping (dominant for flexible, solid conductive TPU); panel thickness merely scales the path length available to each mechanism without changing their hierarchy [

5,

92,

93].

Introducing bio-fillers (activated carbon (AC), granular charcoal (GC), and wood sawdust (WS)) into conductive PLA [1.5mm Perforation Thickness] significantly enhances acoustic performance, crucial for smart orthotics intended to suppress broadband transient noises in wearable devices. Conductive PLA filled with activated carbon is particularly effective for applications requiring strong absorption starting below 1 kHz, notably beneficial for thin orthotic shells. At a manageable 30 mm depth, this configuration already provides excellent damping in the speech band without excessive bulk. Granular charcoal excels in scenarios requiring balanced broadband control, such as motorized exoskeleton joints or sensor housings, by maintaining high absorption from mid to high frequencies even at relatively shallow depths (around 30 mm). Sawdust-filled composites, meanwhile, deliver targeted mid-frequency absorption ideal for disposable or lightweight orthotics that need specific noise reduction in the 1–3 kHz "squeak" range without incurring high production costs or increased weight. The choice of bio-filler, combined with careful management of cavity depth, allows significant acoustic customization alongside enhancing sustainability, as all bio-fillers derive from renewable or industrial by-products, simultaneously providing structural integrity, acoustic damping, and biomechanical sensing within a monolithic, recyclable component.

For conductive TPU composites [1.5mm Perforation Thickness] filled with bio-fillers (AC, GC, WS), similar benefits emerge, tailored to wearable orthoses. Activated carbon-filled TPU offers outstanding broadband acoustic absorption, particularly when deeper cavities (around 50 mm) are feasible, effectively mitigating mechanical noises typical of rigid orthotic components like footplates or tibial shells. Granular charcoal-filled TPU provides an ideal acoustic solution where space constraints necessitate slimmer profiles, maintaining reliable broadband damping at shallower depths (around 30 mm). Sawdust-filled TPU emerges as a cost-effective, lightweight alternative; although it exhibits lower absolute absorption, it markedly improves with increased cavity depth, making it suitable for disposable foot orthotics needing moderate acoustic control with minimal material investment. The acoustic effectiveness in TPU is mainly determined by filler selection, with cavity depth acting as a tuning parameter. Thus, designers can independently optimize these variables, enhancing practicality in developing multifunctional orthotics that are both acoustically efficient and comfortable.

Comparing conductive PLA and TPU [1.5mm Perforation Thickness] at an identical cavity depth (30 mm) and with bio-fillers (AC, GC, WS) at 100% infill highlights notable differences stemming from polymer stiffness and elasticity. Conductive PLA, being stiffer, consistently achieves slightly higher broadband acoustic absorption due to its rigidity, enhancing viscous losses within the filler. In contrast, TPU’s inherent elasticity allows microscopic panel deformation, which can slightly reduce low-frequency absorption but improve damping at higher frequencies through additional vibrational energy dissipation. From an orthotics perspective, conductive PLA is recommended for semi-rigid structural elements where acoustic damping is critical, whereas TPU is preferred for comfort-focused, flexible components requiring comparable acoustic performance with the additional benefit of mechanical compliance.

When considering conductive PLA filled with bio-fillers (AC, WS, GC) at 50% infill with varied perforation thickness [0.5mm,1.5mm, 2.5mm, 3.5mm, 8mm], the data demonstrate that acoustic performance is governed by three key design parameters: filler selection, cavity depth, and perforation panel thickness. Activated carbon offers substantial improvements in low-frequency absorption with increased cavity depth, whereas granular charcoal maintains strong absorption even at moderate depths, achieving broad and flat acoustic spectra. Sawdust requires maximum cavity depth to approach the effectiveness of other fillers, offering significant advantages primarily in cost-sensitive applications. Varying perforated panel thickness enables fine-tuning of resonance frequency and absorption characteristics, with thinner perforated panels enhancing high-frequency absorption and thicker perforated panels shifting performance toward lower frequencies. Thus, these independent yet complementary parameters empower designers to tailor acoustic properties specifically to orthotic applications without increasing complexity or sacrificing sustainability.

In conductive TPU composites with biofillers (AC, WS, GC) at 50% infill and varying perforation thickness [0.5mm,1.5mm, 2.5mm, 3.5mm, 8mm], acoustic absorption strongly depends on the interplay between filler microstructure and geometric factors. Activated carbon, characterized by its ultra-high internal surface area, supports substantial viscous losses across a wide frequency band, making it ideal for broadband absorption, particularly when combined with thin perforated panel and deep cavities. Granular charcoal, due to its coarser pore structure, excels in lower-frequency absorption but has diminishing high-frequency effectiveness. Sawdust relies heavily on resonance effects, providing targeted mid-band absorption with limited broadband efficiency. Cavity depth significantly influences resonance frequency placement, allowing designers to strategically align absorption peaks with specific noise frequencies of concern. The detailed statistical analysis emphasizes that optimal acoustic outcomes in TPU composites are achieved by selecting the appropriate filler first, followed by strategic adjustments in cavity depth and perforation thickness to refine acoustic response, thus enabling precise and sustainable acoustic optimization tailored for smart orthotic solutions.

Conductive PLA and TPU composites exhibit impressive acoustic absorption characteristics, particularly valuable for wearable orthotics. Activated carbon-filled PLA, for example, shows exceptional low-to-mid-frequency absorption, reaching coefficients as high as 0.98 at 2 kHz with moderate cavity depths (28.5–30 mm). This acoustic property is crucial for suppressing mechanical noises such as clicks, squeaks, and motorized whines generated by orthotic hinges, joints, and fasteners. Granular charcoal, meanwhile, provides consistently balanced broadband damping (coefficients ≥ 0.70 from 630–6300 Hz), ideal for general-purpose noise control across the audible range. Wood sawdust offers targeted mid-frequency absorption beneficial for specific noise issues (e.g., frictional squeaks around 1–3 kHz) with minimal weight and cost. Thus, choosing bio-fillers and tuning cavity depth and perforation thickness enables engineers to customize acoustic properties precisely to patient comfort and orthotic functionality.

Conductive PLA stays rigid even with carbon-black loading, so it relies almost entirely on airflow drag inside the bio-filler to absorb sound. Very fine activated carbon creates the highest drag and gives the best low-frequency absorption, even with a 30 mm rear cavity. Coarser granular charcoal spreads the absorption across a wider band, while the large pores in wood sawdust act like a narrow resonator around 1–3 kHz unless the cavity is made much deeper. Conductive TPU is softer and already well-damped. With a shallow cavity it follows the same ranking—activated carbon > charcoal > sawdust—but when the cavity is deeper the solid TPU sheet can flex, and its own viscoelastic losses add a second, broadband absorption path. This lets activated-carbon and charcoal-filled TPU equal or exceed PLA at higher frequencies, while sawdust stays more selective. In short, filler pore size sets the basic behavior, cavity depth shifts the absorption peak, and—only in TPU—the matrix itself adds extra damping as depth increases. Perforations thickness then provides a final fine-tune [

5,

92,

93].

Incorporating conductive polymers such as ProtoPasta’s conductive PLA and NinjaTek’s conductive TPU into orthotics provides meaningful EMI shielding—a critical feature for modern smart devices that embed sensors, wireless modules, and actuators directly in wearable form factors. In practice, 3D-printed panels of ProtoPasta’s CON-PLA have demonstrated approximately 10-20 dB of shielding effectiveness across the 3.5–7 GHz C-band, attenuating over 90 % of incident RF energy and ensuring stable, low-noise sensor readings. By contrast, NinjaTek’s Eel TPU, while excellent for static-dissipation, typically delivers under 5-10 dB of RF attenuation, making it more suited for electrostatic discharge protection than true EMI isolation.

Because of its higher rigidity and conductivity, conductive PLA is especially effective for shielding rigid structural elements—sensor housings, semi-rigid braces, and electronics enclosures—where it can both block external fields and provide mechanical support. Conductive TPU, meanwhile, balances its modest RF performance with superior flexibility and wearer comfort, making it ideal for compliant shells and interfaces in direct contact with the body.

A significant advantage of conductive PLA-based composites lies in their sustainability profile. PLA is derived from renewable resources (typically cornstarch or sugarcane), reducing dependence on petroleum-based polymers. When coupled with bio-fillers such as AC, GC, and WS—materials themselves derived from agricultural or industrial by-products—PLA orthotics align strongly with circular economy principles. After serving their functional life, PLA-based orthotics offer the added advantage of controlled biodegradability. While maintaining their structural and acoustic integrity during intended use (e.g., via bio-compatible and biodegradable coatings), PLA orthotic components can later be biodegraded under industrial composting conditions. Such compostability significantly reduces the environmental footprint compared to traditional petroleum-based plastics.

As far as fillers are concerned, as a high-surface-area, graphitic filler, AC is widely shown to enhance composite conductivity. In polyurethane systems, AC derived from sawdust provided effective dielectric properties and EMI shielding with as little as 8 wt% loading [

94]. Similarly, AC electrodes exhibited reduced impedance and improved capacitance when combined with other conductive additives [

95]. Though less porous than AC, charcoal retains conductive potential. HDPE composites containing 20 wt% charcoal demonstrated sufficient network formation to reduce resistivity for functional use, confirming that even non-activated forms can contribute meaningfully to transport properties [

96]. Untreated wood sawdust is inherently insulating. Studies confirm that its addition generally reduces conductivity unless blended with conductive additives [

97]. Importantly, Castro et al. show that sawdust must be pyrolyzed and activated to develop the microstructural features necessary for conductive performance [

98]. This supports our characterization of WS as a diluting filler in the composite system. It is also found that carbonized or chemically modified sawdust is required to make WS conductive [

99]. Carbon-based fillers such as AC and GC are also known to enhance thermal conductivity, promoting passive heat dissipation from embedded circuitry.

It is worth considering that all tested configurations exhibit diminishing absorption above ~3–4 kHz. This decline in high-frequency response likely arises from the 3D-printed structure and material properties. At these frequencies, the acoustic wavelength approaches the perforation scale, so much of the energy is reflected rather than entering the cavity. Surface roughness and short viscous boundary layers further reduce damping efficiency. Thick panels behave as rigid barriers, blocking high-frequency sound (as observed in the drop of α at the spectrum’s upper end for 100%-infill and 50% infill 8-mm-thick samples. In contrast, thinner walls and porous fillers extend absorption into the high frequencies (e.g. thin AC-filled PLA α≈0.85 above 4 kHz). Recognizing this, designers should consider that beyond ~3-4 kHz the benefit of deeper cavities or higher infill is limited by the panel’s pore geometry and material damping.

While this study primarily focuses on acoustic behavior, the mechanical performance of the base materials also supports their relevance to wearable orthotics. NinjaTek Eel TPU provides high elasticity, with a tensile strength of 12 MPa and elongation at break of 355%, as well as a tear strength of 84 kN/m and Shore hardness of 90A, making it well-suited for flexible, skin-contact components that endure repeated motion and strain [

88]. In contrast, Protopasta Conductive PLA is a rigid carbon-black-filled thermoplastic designed for conductivity rather than flexibility. Research studies [

100] suggest a Young’s modulus of approximately 1 GPa at room temperature, which drops to ~13.6 MPa at 80 °C, indicating some thermal softening but limited ductility. This material performs best in static or semi-structural roles such as enclosures, sensor housings, or EMI-shielded frames. Together, these contrasting materials offer the potential for hybrid orthotic structures that balance flexibility, durability, and embedded electrical functionality.

In summary, the strategic integration of conductive PLA and TPU bio-filled composites into smart orthotics offers multifunctional advantages: enhanced acoustic comfort, robust EMI protection, structural adaptability, and strong environmental sustainability through renewability and controlled biodegradability for conductive PLA.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we have developed a systematic framework for tailoring the sound absorption performance of 3D-printed conductive PLA and TPU panels—both in their unfilled state and when loaded with bio-derived fillers. By varying five key design parameters (polymer matrix, infill ratio, cavity depth, perforation panel thickness, and bio-filler type), we have identified clear, quantifiable trends that can help in selecting the optimal combination of materials and geometries for specific acoustic results in orthotics.

When without any bio-fillers, TPU behaves most effectively only when printed at full density and paired with deeper cavities (≥ 30 mm). Under these conditions, TPU achieves its strongest mid-band absorption (α ≈ 0.94 at 2.5 kHz) and broadband averages as high as 0.50–0.55. By contrast, TPU at 50 % infill remains largely ineffective above 2 kHz, with mean absorption coefficients of only 0.27–0.32. PLA, on the other hand, more closely resembles a classical micro-perforated panel: moderate infill (50 %) and a medium cavity depth (≈ 30 mm) yield its peak broadband performance (ᾱ = 0.40) with a smooth spectral rise, while increasing PLA’s infill to 100 % often suppresses rather than enhances acoustic dissipation.

Introducing bio-fillers into the PLA matrix fundamentally transforms its absorption profile. Activated carbon (AC) exhibits exceptional low-frequency performance—attaining α > 0.60 at 800 Hz and peaking at α = 0.96 near 1.3 kHz—while maintaining α > 0.60 up to 6.3 kHz (octave-band mean 0.73). Granular charcoal (GC) delivers the flattest broadband response, with α ranging from 0.62 to 0.78 behind a 30 mm gap and mean values up to 0.71 at 50 mm, making it ideal for general-purpose damping. Wood sawdust (WS) produces sharp, narrow resonance peaks (α ≈ 0.91 at 2.5 kHz for a 15 mm gap, shifting to ~1 kHz at greater depths), which are particularly suited to targeted “squeak” mitigation in the 1–3 kHz band.

In TPU panels with bio-fillers, activated carbon again leads the broadband performance, achieving mean α ≈ 0.73 at a 50 mm cavity and exhibiting a remarkably smooth 0.65–0.92 spectrum. Granular charcoal provides uniform mid-band damping even at the shallowest (15 mm) gap, with low-band means of 0.51 and α > 0.71 above 2 kHz, showing minimal sensitivity to depth. Wood sawdust remains the most frequency-selective filler, requiring maximum cavity depth to produce dual peaks near 1 kHz and 4 kHz, and displaying higher variability (σ up to 0.22).

Beyond the primary effects of matrix and filler, perforation panel thickness (0.5–8 mm) offers a third tuning knob. Thinner perforation panel shift resonances upward—enhancing high-frequency absorption (e.g., a 0.5 mm PLA wall with GC yields ᾱ = 0.70, σ = 0.19 at 28.5 mm)—whereas thicker perforated panel favor low-frequency peaks (e.g., 2.5 mm AC panels reach ᾱ = 0.66 at 48.5 mm). Statistical analyses confirmed that, without fillers, only the polymer×infill interaction reaches significance (η² ≈ 0.06), whereas with fillers, both filler type (η² ≈ 0.10–0.27) and cavity depth (η² ≈ 0.10–0.20) dominate independently; perforation thickness adds a further ~11–29 % of explained variance when varied, with some filler×gap and gap×thickness interactions (η² ≈ 0.08–0.09) that can fine-tune resonance placement without overturning the main-effect hierarchies.

These findings yield clear design rules: for compact, broadband damping use granular charcoal with moderate gaps (≈ 30 mm) and thin perforations; for strong low-frequency suppression in thin shells, employ activated carbon in either PLA or TPU with perforated panel thickness ≤ 1.5 mm and gaps ≥ 30 mm; for focused mid-band “squeak” control, choose wood sawdust with deeper cavities and tune the perforated panel thickness to center the resonance. Moreover, PLA offers superior rigidity, EMI shielding, and biodegradability—especially when combined with renewable bio-fillers—while TPU delivers comparable acoustic performance with greater mechanical compliance. By integrating polymer mechanics, perforation physics, filler microstructure, and robust statistical validation, we can now rapidly prototype eco-friendly orthotic components that simultaneously meet acoustic, electromagnetic, and biomechanical requirements. Future work includes finding a polymer composite composition that’s not only offers better EMI Shielding, but also flexibility along with biodegradability for its use in sustainable smart orthotics effectively, further bridging functional composites & additive manufacturing with the next generation of smart orthotic technologies.